cac6a975b523ed37ec8f18c8b75d8881.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 25

Optimal Taxation Theory and the Taxation of Housing Alan W. Evans Centre for Spatial and Real Estate Economics University of Reading

Optimal Taxation Theory and the Taxation of Housing Alan W. Evans Centre for Spatial and Real Estate Economics University of Reading

Optimal Taxation Theory • Premise: a government wishes to raise a given sum through taxation but recognises that taxes distort choice. • Question: How should it raise this money if it wishes to minimise the distortion which does occur?

Optimal Taxation Theory • Premise: a government wishes to raise a given sum through taxation but recognises that taxes distort choice. • Question: How should it raise this money if it wishes to minimise the distortion which does occur?

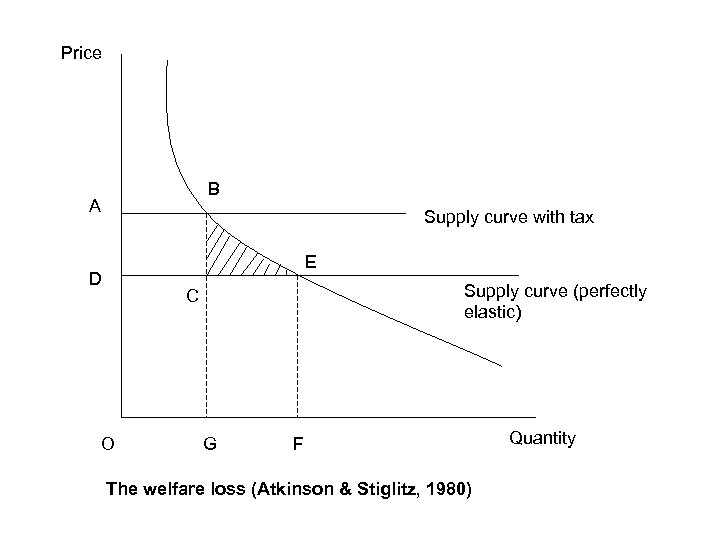

Price B A Supply curve with tax E D Supply curve (perfectly elastic) C O G F The welfare loss (Atkinson & Stiglitz, 1980) Quantity

Price B A Supply curve with tax E D Supply curve (perfectly elastic) C O G F The welfare loss (Atkinson & Stiglitz, 1980) Quantity

For Efficiency or Equity • For Efficiency: Impose taxes on goods with low price elasticity, like housing • For Equity: Impose taxes on goods with a high income elasticity, unlike housing.

For Efficiency or Equity • For Efficiency: Impose taxes on goods with low price elasticity, like housing • For Equity: Impose taxes on goods with a high income elasticity, unlike housing.

A Survey of Recent Research

A Survey of Recent Research

Cremer and Gahravi (1998) • They set out to explain housing subsidies for the poor. • Subsidies are OK if poorer households can be distinguished, and • If poorer households have a stronger preference for lower quality housing than do wealthier households

Cremer and Gahravi (1998) • They set out to explain housing subsidies for the poor. • Subsidies are OK if poorer households can be distinguished, and • If poorer households have a stronger preference for lower quality housing than do wealthier households

So subsidies are a side issue, since the Cremer and Gahravi result is not very policy relevant. All other research relates to the question of the separate tax treatment of owner occupation and renting. Past research, going back to Laidler (1969), suggests a welfare loss of a half a percent or so, but this research uses static models

So subsidies are a side issue, since the Cremer and Gahravi result is not very policy relevant. All other research relates to the question of the separate tax treatment of owner occupation and renting. Past research, going back to Laidler (1969), suggests a welfare loss of a half a percent or so, but this research uses static models

Skinner (1996) • Argues dynamic effects are substantial. • Uses an overlapping generations with bequests model – welfare loss of 2% • Low tax on o. o. causes price rise • This results in a windfall gain to existing owner occupiers. • The saving of younger generations is distorted and goes into low taxed housing.

Skinner (1996) • Argues dynamic effects are substantial. • Uses an overlapping generations with bequests model – welfare loss of 2% • Low tax on o. o. causes price rise • This results in a windfall gain to existing owner occupiers. • The saving of younger generations is distorted and goes into low taxed housing.

Gervais (2002) • Models a dynamic general equilibrium life cycle economy. • Finds that low taxes encourage owner occupation, and • Encourage owner occupiers to over-invest in housing

Gervais (2002) • Models a dynamic general equilibrium life cycle economy. • Finds that low taxes encourage owner occupation, and • Encourage owner occupiers to over-invest in housing

• Simulation (for U. S. ) suggests: • Stock of business capital is 6% too low • Stock of housing capital is 8% too high

• Simulation (for U. S. ) suggests: • Stock of business capital is 6% too low • Stock of housing capital is 8% too high

Englund (2003) • Tax incentives encourage the young to buy early • This results in a pattern of saving where savings are high until they can buy, then low (Englehardt, 2003) • The incentives also encourage taking on a high risk which they should not.

Englund (2003) • Tax incentives encourage the young to buy early • This results in a pattern of saving where savings are high until they can buy, then low (Englehardt, 2003) • The incentives also encourage taking on a high risk which they should not.

Eerola and Maattinen (2005) • Taxes on owner occupied housing should be higher than on business income, not lower • Firstly, the tax on imputed income from property, and then • Secondly, an extra tax on housing as a good or service (like VAT)

Eerola and Maattinen (2005) • Taxes on owner occupied housing should be higher than on business income, not lower • Firstly, the tax on imputed income from property, and then • Secondly, an extra tax on housing as a good or service (like VAT)

The Problem of Land • Land is not included in these models, it is something ‘where further research is needed’.

The Problem of Land • Land is not included in these models, it is something ‘where further research is needed’.

Property Taxes in the USA • These are ignored by researchers • The justification is that they pay for benefits • Therefore the two cancel out • Research shows that taxes reduce property values and benefits increase them • But at the margin? • And with other tax systems?

Property Taxes in the USA • These are ignored by researchers • The justification is that they pay for benefits • Therefore the two cancel out • Research shows that taxes reduce property values and benefits increase them • But at the margin? • And with other tax systems?

A Conclusion • Property taxes are much higher in the US than in most other countries. • Equal to about 1% of value. Differences like Proposition 13 in California make it difficult to generalise. • But US tax policy is more neutral than previous researchers suggest.

A Conclusion • Property taxes are much higher in the US than in most other countries. • Equal to about 1% of value. Differences like Proposition 13 in California make it difficult to generalise. • But US tax policy is more neutral than previous researchers suggest.

The UK & Tax Neutrality • Used to have a tax on the imputed income from owner occupied housing, up to 1961. • Used to allow mortgage interest as a tax deduction, but this was phased out between 1976 and 2000. • Gervais regards interest tax deductibility as the main problem in the US

The UK & Tax Neutrality • Used to have a tax on the imputed income from owner occupied housing, up to 1961. • Used to allow mortgage interest as a tax deduction, but this was phased out between 1976 and 2000. • Gervais regards interest tax deductibility as the main problem in the US

Other Taxes & Other Investment • Capital Gains Tax – Neutral, because of roll over relief. • Stamp Duty (Transfer Tax) – Neutral because small and charged on both. • VAT – Not charged on any residential property, except extensions.

Other Taxes & Other Investment • Capital Gains Tax – Neutral, because of roll over relief. • Stamp Duty (Transfer Tax) – Neutral because small and charged on both. • VAT – Not charged on any residential property, except extensions.

Income Taxes • Contributions to pension schemes have always been tax deductible and for most this is their main form of saving and investment. • Since the early nineties investment through PEPs and then ISAs has been possible which is not subject to income or capital gains tax. For all but the wealthiest the amounts are substantial. • Does this help to ensure neutrality?

Income Taxes • Contributions to pension schemes have always been tax deductible and for most this is their main form of saving and investment. • Since the early nineties investment through PEPs and then ISAs has been possible which is not subject to income or capital gains tax. For all but the wealthiest the amounts are substantial. • Does this help to ensure neutrality?

Property Taxes in Britain • The UK property tax (Council Tax) is not proportional to capital value. • It is regressive, a high percentage on low value dwellings, then lower. • It is effectively a fixed amount for dwellings worth over about £ 1 m

Property Taxes in Britain • The UK property tax (Council Tax) is not proportional to capital value. • It is regressive, a high percentage on low value dwellings, then lower. • It is effectively a fixed amount for dwellings worth over about £ 1 m

The UK System • The older and wealthier are favoured over the poorer and younger • Although the younger may be paying mortgage interest they are encouraged to buy and wait until, after ten or twenty years mortgage interest can be ignored • This is exacerbated by the implicit tax on land.

The UK System • The older and wealthier are favoured over the poorer and younger • Although the younger may be paying mortgage interest they are encouraged to buy and wait until, after ten or twenty years mortgage interest can be ignored • This is exacerbated by the implicit tax on land.

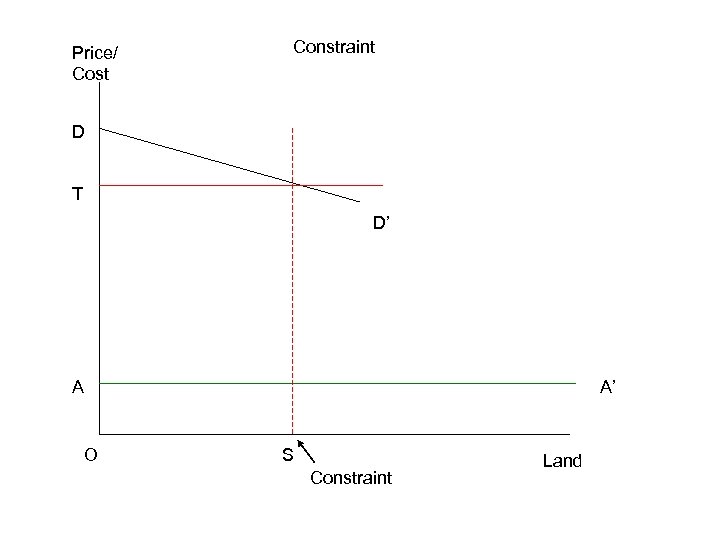

Price/ Cost Constraint D T D’ A O A’ S Constraint Land

Price/ Cost Constraint D T D’ A O A’ S Constraint Land

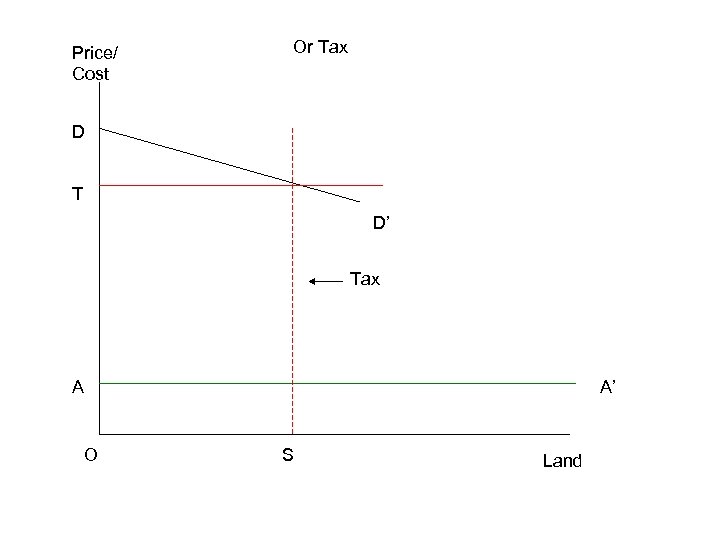

Price/ Cost Or Tax D T D’ Tax A O A’ S Land

Price/ Cost Or Tax D T D’ Tax A O A’ S Land

The UK and Land • House prices rise by 3. 3% p. a. in real terms (W. European average 1. 8%) • An implicit tax, paid by the younger generation to the older • House construction is constrained • New dwellings are smaller than in the rest of western Europe – England 76 sq. m. , France 112. 8 sq. m. , Germany 109. 2 sq. m. (Eurostat, 2002)

The UK and Land • House prices rise by 3. 3% p. a. in real terms (W. European average 1. 8%) • An implicit tax, paid by the younger generation to the older • House construction is constrained • New dwellings are smaller than in the rest of western Europe – England 76 sq. m. , France 112. 8 sq. m. , Germany 109. 2 sq. m. (Eurostat, 2002)

Commercial Land • Taxed at a higher rate than residential land • Extensive Uses (i. e. Manufacturing) Discouraged • Intensive Uses (i. e. Offices) Encouraged • Property Rented by Firms (possibly by Sale and Lease Back), not owned

Commercial Land • Taxed at a higher rate than residential land • Extensive Uses (i. e. Manufacturing) Discouraged • Intensive Uses (i. e. Offices) Encouraged • Property Rented by Firms (possibly by Sale and Lease Back), not owned

Conclusions • More research is needed on the role of land. • In the UK land controls mean that there does not seem to be overinvestment in housing. • Favourable tax treatment of savings helps in this • But the market is distorted both by controls and the Council Tax, and the latter is definitely not an optimal tax. • There seems no reason why VAT should not be imposed on new housing.

Conclusions • More research is needed on the role of land. • In the UK land controls mean that there does not seem to be overinvestment in housing. • Favourable tax treatment of savings helps in this • But the market is distorted both by controls and the Council Tax, and the latter is definitely not an optimal tax. • There seems no reason why VAT should not be imposed on new housing.