2ea16e00cccb0e50240db28c04167794.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 64

Optimal Management of HBV: A Partnership Between Primary Care and Specialty Physicians

Primary Care Specialist Screening Diagnostic testing Identification of treatment candidates Initiation of treatment On-treatment monitoring Long-term follow-up for disease activation HCC screening

Hepatitis B: An Important Disease for Primary Care and Specialty Physicians

Why Is HBV Relevant in Primary Care? l High global impact – High prevalence in specific risk groups – Risk of death/cancer l Effective prevention l Effective treatment – Improve liver disease outcomes – Decrease progression to cirrhosis or HCC and improve survival

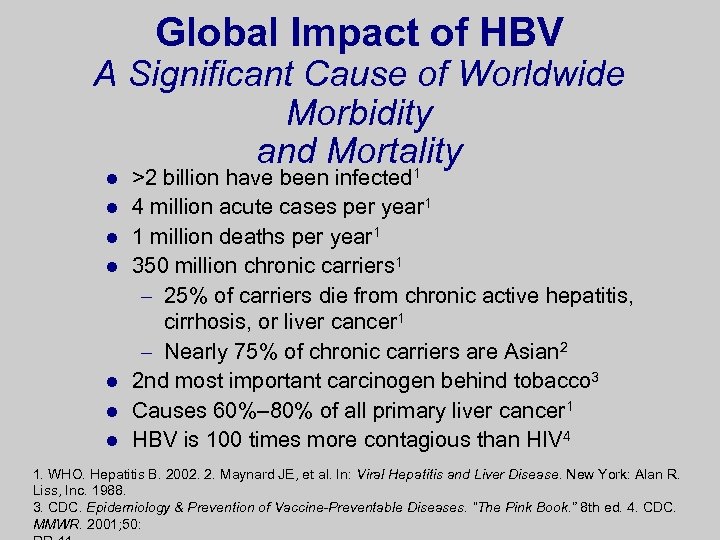

Global Impact of HBV A Significant Cause of Worldwide Morbidity and Mortality 1 l l l l >2 billion have been infected 4 million acute cases per year 1 1 million deaths per year 1 350 million chronic carriers 1 – 25% of carriers die from chronic active hepatitis, cirrhosis, or liver cancer 1 – Nearly 75% of chronic carriers are Asian 2 2 nd most important carcinogen behind tobacco 3 Causes 60%– 80% of all primary liver cancer 1 HBV is 100 times more contagious than HIV 4 1. WHO. Hepatitis B. 2002. 2. Maynard JE, et al. In: Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease. New York: Alan R. Liss, Inc. 1988. 3. CDC. Epidemiology & Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. “The Pink Book. ” 8 th ed. 4. CDC. MMWR. 2001; 50:

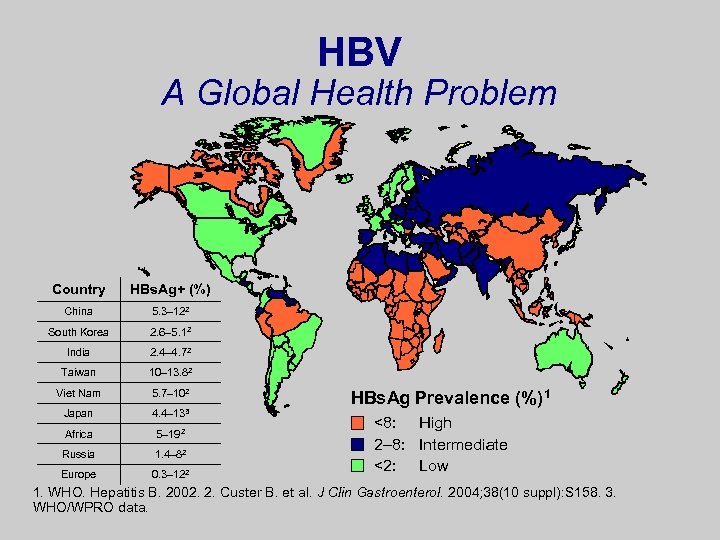

HBV A Global Health Problem Country HBs. Ag+ (%) China 5. 3– 122 South Korea 2. 6– 5. 12 India 2. 4– 4. 72 Taiwan 10– 13. 82 Viet Nam 5. 7– 102 Japan 4. 4– 133 Africa 5– 192 Russia 1. 4– 82 Europe 0. 3– 122 HBs. Ag Prevalence (%)1 <8: High 2– 8: Intermediate <2: Low 1. WHO. Hepatitis B. 2002. 2. Custer B. et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004; 38(10 suppl): S 158. 3. WHO/WPRO data.

HBV Disease Progression Liver Cancer (HCC) n Chronic Infectio Cirrhosi s Liver Transplantatio n Death Liver Failure Torresi J, et al. Gastroenterology. 2000; 118: S 83. Fattovich G, et al. Hepatology. 1995; 21: 77. Perrillo RP, et al. Hepatology. 2001; 33: 424.

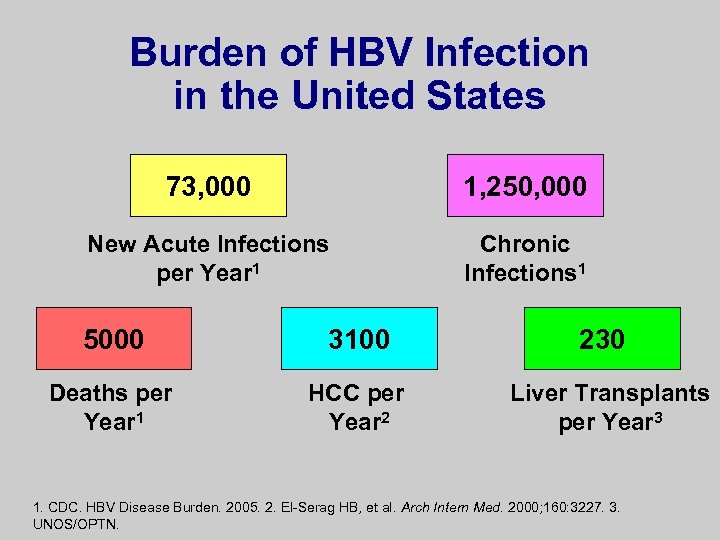

Burden of HBV Infection in the United States 73, 000 1, 250, 000 New Acute Infections per Year 1 Chronic Infections 1 5000 3100 Deaths per Year 1 HCC per Year 2 230 Liver Transplants per Year 3 1. CDC. HBV Disease Burden. 2005. 2. El-Serag HB, et al. Arch Intern Med. 2000; 160: 3227. 3. UNOS/OPTN.

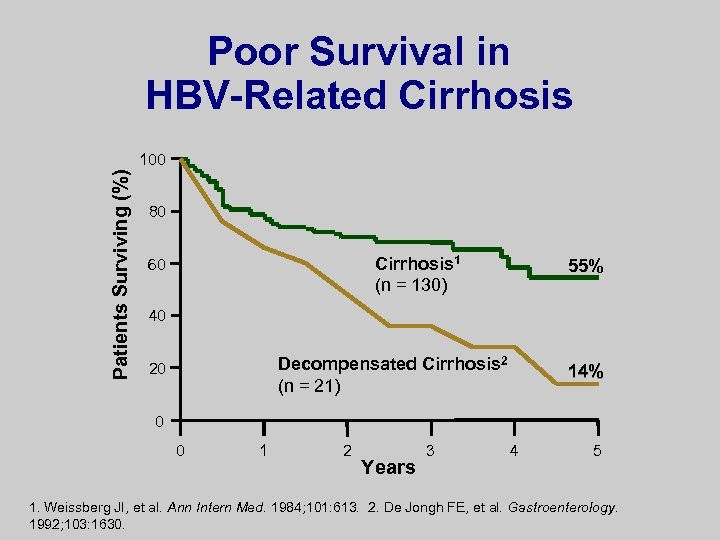

Poor Survival in HBV-Related Cirrhosis Patients Surviving (%) 100 80 Cirrhosis 1 (n = 130) 60 55% 40 Decompensated Cirrhosis 2 (n = 21) 20 14% 0 0 1 2 Years 3 4 5 1. Weissberg JI, et al. Ann Intern Med. 1984; 101: 613. 2. De Jongh FE, et al. Gastroenterology. 1992; 103: 1630.

HBV Is Preventable

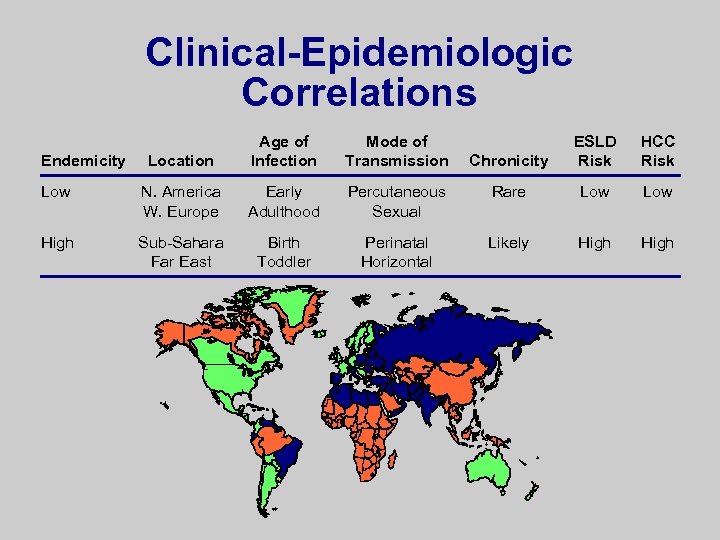

Clinical-Epidemiologic Correlations Location Age of Infection Mode of Transmission Low N. America W. Europe Early Adulthood High Sub-Sahara Far East Birth Toddler Endemicity Chronicity ESLD Risk HCC Risk Percutaneous Sexual Rare Low Perinatal Horizontal Likely High

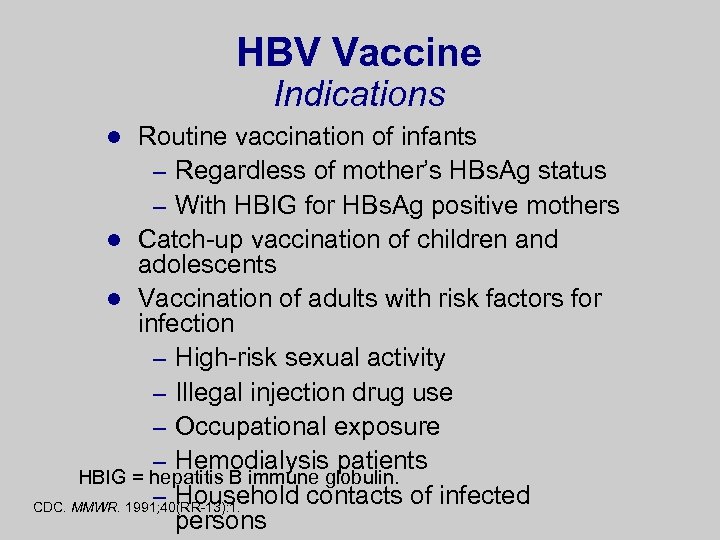

HBV Vaccine Indications Routine vaccination of infants – Regardless of mother’s HBs. Ag status – With HBIG for HBs. Ag positive mothers l Catch-up vaccination of children and adolescents l Vaccination of adults with risk factors for infection – High-risk sexual activity – Illegal injection drug use – Occupational exposure – Hemodialysis patients HBIG = hepatitis B immune globulin. – Household contacts of infected CDC. MMWR. 1991; 40(RR-13): 1. persons l

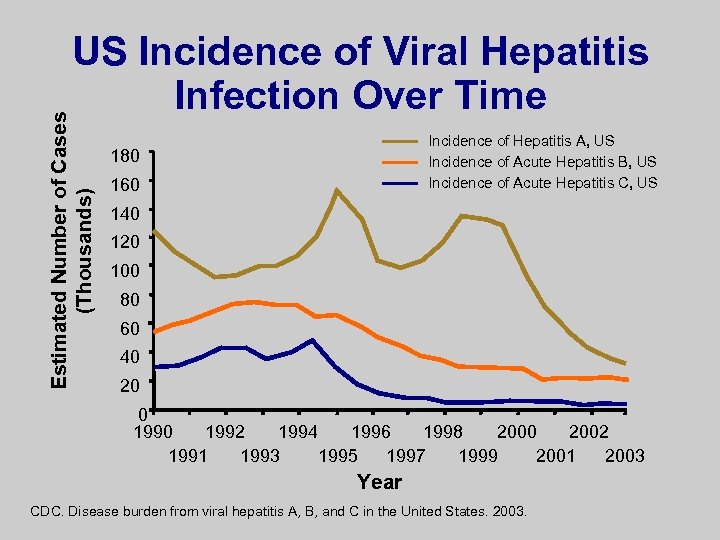

Estimated Number of Cases (Thousands) US Incidence of Viral Hepatitis Infection Over Time Incidence of Hepatitis A, US Incidence of Acute Hepatitis B, US Incidence of Acute Hepatitis C, US 180 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 Year CDC. Disease burden from viral hepatitis A, B, and C in the United States. 2003.

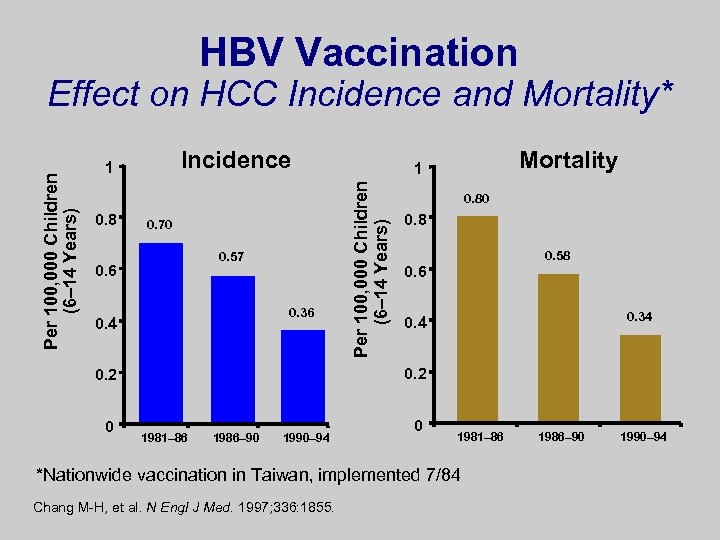

HBV Vaccination Incidence 1 0. 8 0. 70 0. 57 0. 6 0. 36 0. 4 0. 80 0. 8 0. 58 0. 6 0. 34 0. 2 0 Mortality 1 Per 100, 000 Children (6– 14 Years) Effect on HCC Incidence and Mortality* 1981– 86 1986– 90 1990– 94 0 1981– 86 *Nationwide vaccination in Taiwan, implemented 7/84 Chang M-H, et al. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336: 1855. 1986– 90 1990– 94

Screening for HBV and Evaluating Infected Patients

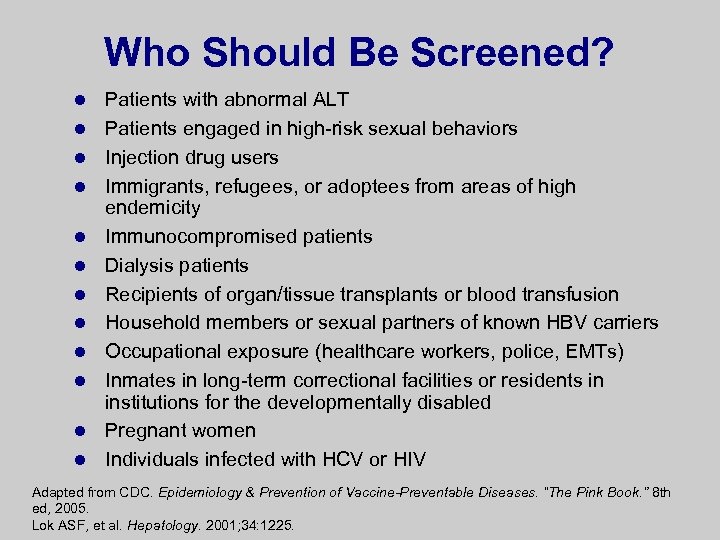

Who Should Be Screened? l l l Patients with abnormal ALT Patients engaged in high-risk sexual behaviors Injection drug users Immigrants, refugees, or adoptees from areas of high endemicity Immunocompromised patients Dialysis patients Recipients of organ/tissue transplants or blood transfusion Household members or sexual partners of known HBV carriers Occupational exposure (healthcare workers, police, EMTs) Inmates in long-term correctional facilities or residents in institutions for the developmentally disabled Pregnant women Individuals infected with HCV or HIV Adapted from CDC. Epidemiology & Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. “The Pink Book. ” 8 th ed, 2005. Lok ASF, et al. Hepatology. 2001; 34: 1225.

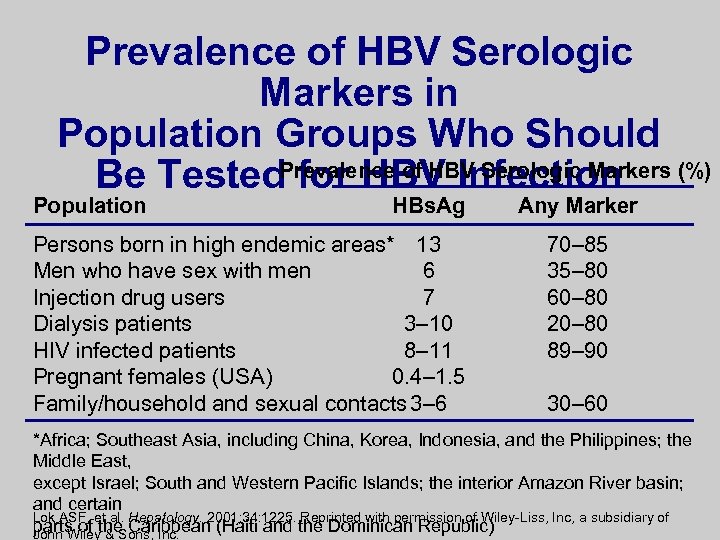

Prevalence of HBV Serologic Markers in Population Groups Who Should Be Tested. Prevalence of HBV Serologic Markers (%) for HBV Infection Population HBs. Ag Persons born in high endemic areas* 13 Men who have sex with men 6 Injection drug users 7 Dialysis patients 3– 10 HIV infected patients 8– 11 Pregnant females (USA) 0. 4– 1. 5 Family/household and sexual contacts 3– 6 Any Marker 70– 85 35– 80 60– 80 20– 80 89– 90 30– 60 *Africa; Southeast Asia, including China, Korea, Indonesia, and the Philippines; the Middle East, except Israel; South and Western Pacific Islands; the interior Amazon River basin; and certain Lok ASF, et al. Hepatology. 2001; 34: 1225. Reprinted with permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc, a subsidiary of parts of the Caribbean (Haiti and the Dominican Republic) John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Screening Tests HBs. Ag – If positive, indicates infection l Anti-HBc – If positive, indicates HBV exposure l Anti-HBs – If positive, indicates immunity l

History and Physical Evaluation l Risk factors for coinfection l Alcohol use l Family history of HBV infection and HCC l Physical findings of advanced disease – Jaundice – Abdominal swelling – Upper GI bleeding Lok ASF, et al. Hepatology. 2001; 34: 1225. Tsai NCS, et al. Semin Liver Dis. 2004; 24(suppl 1): 71.

Assessment of Liver Disease Severity Liver disease activity, biochemical – ALT – AST l Liver function/synthetic testing – Albumin – Bilirubin – Prothrombin time (INR) l Ultrasonography: morphologic assessment – Liver size, contour, and echogenicity – Splenomegaly l Lok ASF, et al. Hepatology 2001; 34: 1225. Tsai NCS, et al. Semin Liver Dis. 2004; 24(suppl 1): 71. Keeffe EB, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004; 2: 87.

2 nd-Phase Testing in HBs. Ag+ Patients Anti-HBc – Ig. G: if positive, indicates HBV exposure – Ig. M: if positive, indicates acute HBV l HBe. Ag – If positive, indicates active HBV replication – If negative n If HBV DNA negative, suggests HBV replication is suppressed n If HBV DNA positive, most likely has precore mutation l Anti-HBe l HBV DNA quantification – Quantitative level correlates with level of HBV replication l

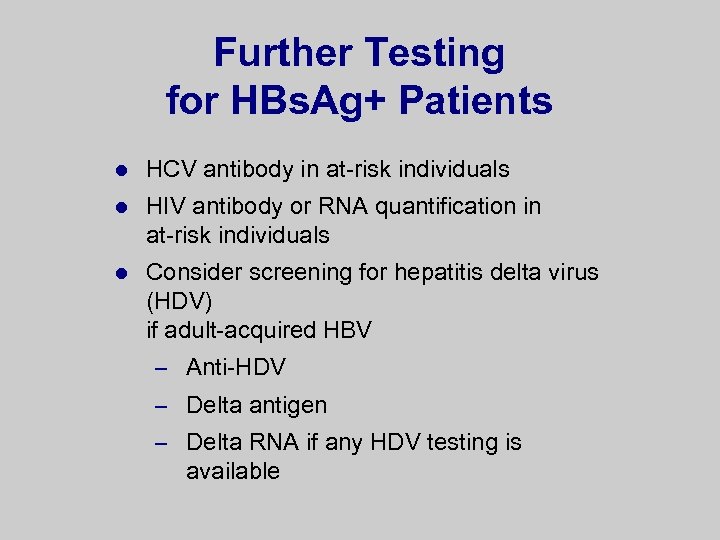

Further Testing for HBs. Ag+ Patients l HCV antibody in at-risk individuals l HIV antibody or RNA quantification in at-risk individuals l Consider screening for hepatitis delta virus (HDV) if adult-acquired HBV – Anti-HDV – Delta antigen – Delta RNA if any HDV testing is available

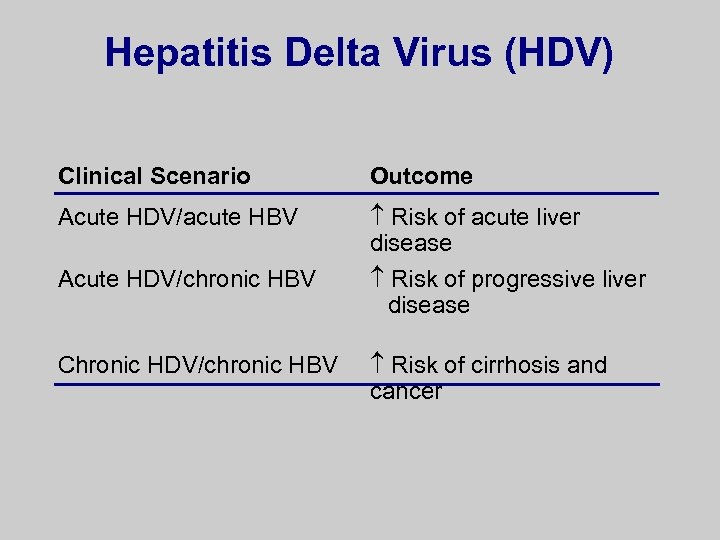

Hepatitis Delta Virus (HDV) Clinical Scenario Outcome Acute HDV/acute HBV Risk of acute liver disease Acute HDV/chronic HBV Risk of progressive liver disease Chronic HDV/chronic HBV Risk of cirrhosis and cancer

Who Are Treatment Candidates?

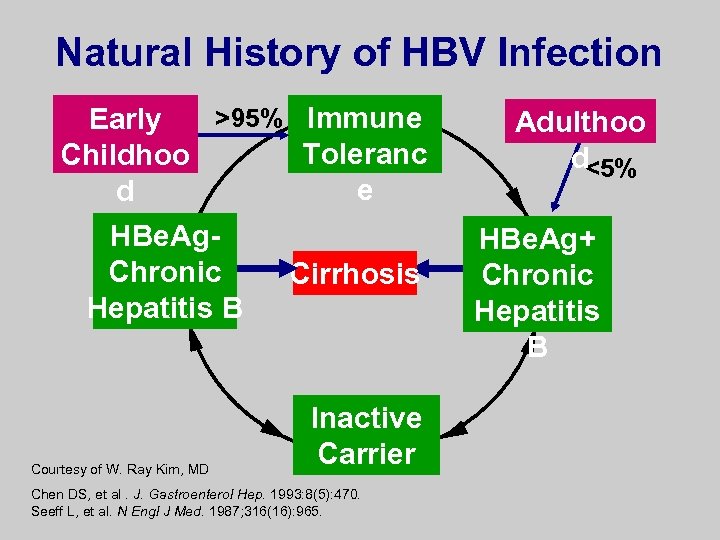

Natural History of HBV Infection >95% Immune Early Toleranc Childhoo e d HBe. Ag. Chronic Hepatitis B Courtesy of W. Ray Kim, MD Cirrhosis Inactive Carrier Chen DS, et al. J. Gastroenterol Hep. 1993: 8(5): 470. Seeff L, et al. N Engl J Med. 1987; 316(16): 965. Adulthoo d<5% HBe. Ag+ Chronic Hepatitis B

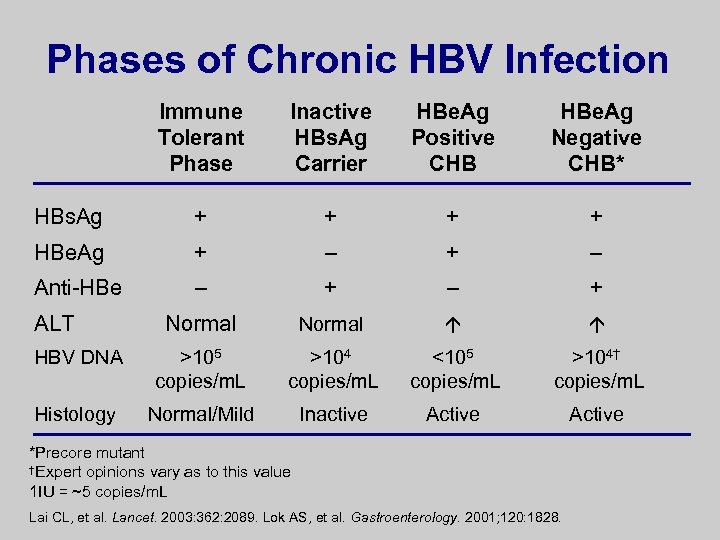

Phases of Chronic HBV Infection Immune Tolerant Phase Inactive HBs. Ag Carrier HBe. Ag Positive CHB HBe. Ag Negative CHB* HBs. Ag + + HBe. Ag + – Anti-HBe – + Normal HBV DNA >105 copies/m. L >104 copies/m. L <105 copies/m. L >104† copies/m. L Histology Normal/Mild Inactive Active ALT *Precore mutant †Expert opinions vary as to this value 1 IU = ~5 copies/m. L Lai CL, et al. Lancet. 2003: 362: 2089. Lok AS, et al. Gastroenterology. 2001; 120: 1828.

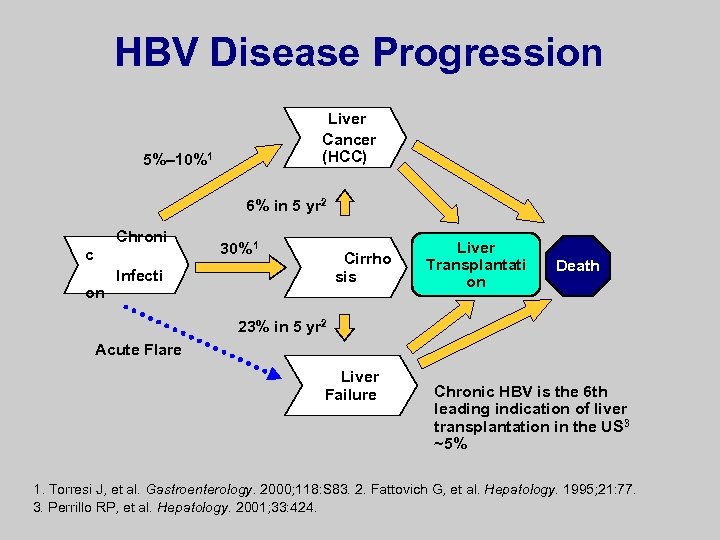

HBV Disease Progression Liver Cancer (HCC) 5%– 10%1 6% in 5 yr 2 Chroni c on 30%1 Cirrho sis Infecti Liver Transplantati on Death 23% in 5 yr 2 Acute Flare Liver Failure Chronic HBV is the 6 th leading indication of liver transplantation in the US 3 ~5% 1. Torresi J, et al. Gastroenterology. 2000; 118: S 83. 2. Fattovich G, et al. Hepatology. 1995; 21: 77. 3. Perrillo RP, et al. Hepatology. 2001; 33: 424.

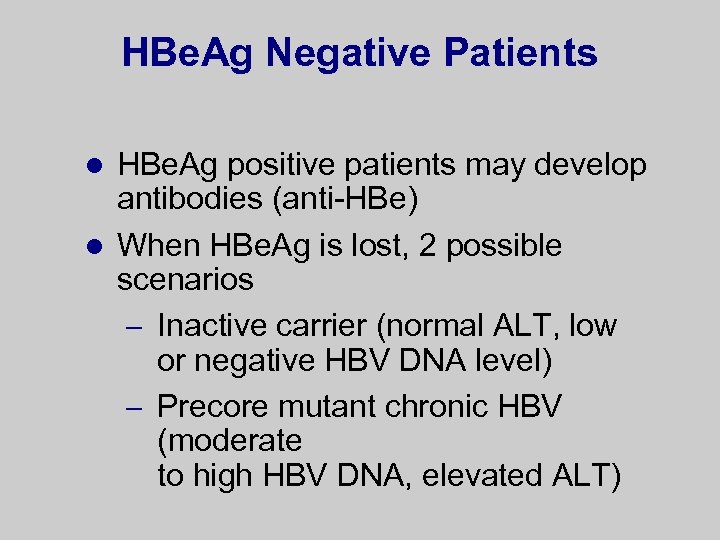

HBe. Ag Negative Patients HBe. Ag positive patients may develop antibodies (anti-HBe) l When HBe. Ag is lost, 2 possible scenarios – Inactive carrier (normal ALT, low or negative HBV DNA level) – Precore mutant chronic HBV (moderate to high HBV DNA, elevated ALT) l

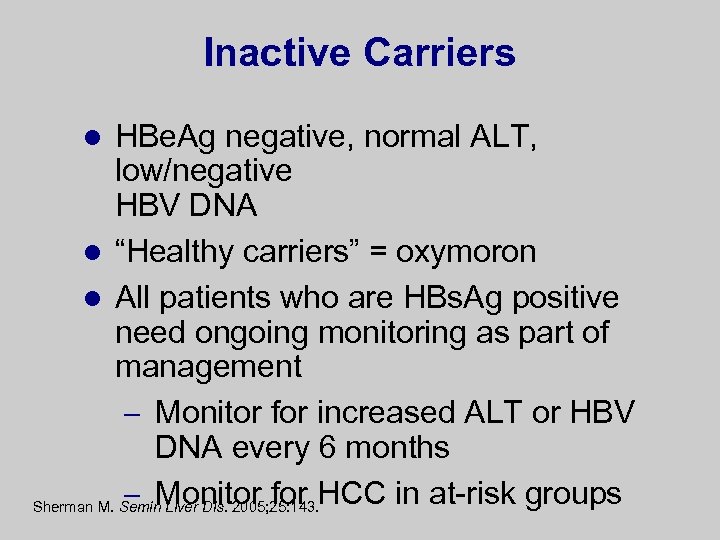

Inactive Carriers HBe. Ag negative, normal ALT, low/negative HBV DNA l “Healthy carriers” = oxymoron l All patients who are HBs. Ag positive need ongoing monitoring as part of management – Monitor for increased ALT or HBV DNA every 6 months – Monitor for HCC in at-risk groups Sherman M. Semin Liver Dis. 2005; 25: 143. l

Precore Mutant (HBe. Ag Negative) Chronic HBV l HBe. Ag negative, elevated ALT, moderate to high HBV DNA Usually result of mutation in precore or basal core promoter regions of HBV l Potentially more severe and progressive chronic disease l Longer, more aggressive (suppression of HBV DNA) treatment needed l 29% risk of adefovir resistance at 5 years of 1. Borroto-Esoda K, et al. J Hepatol. 2006; 44(Suppl 2): 179. therapy 1 l

HBV DNA and Prognosis High viral load predicts l Progression of liver disease 1 l Cirrhosis-related complications 2 l HCC 1, 3 – Independent of HBe. Ag, ALT, 1. Chen G, et al. Abstract 996. Presented at: AASLD 2004. 2. Yuan JH, et al. J Viral Hepat. and cirrhosis 3 2005; 12: 373. 3. Chen C-J, et al. JAMA. 2006; 295: 65.

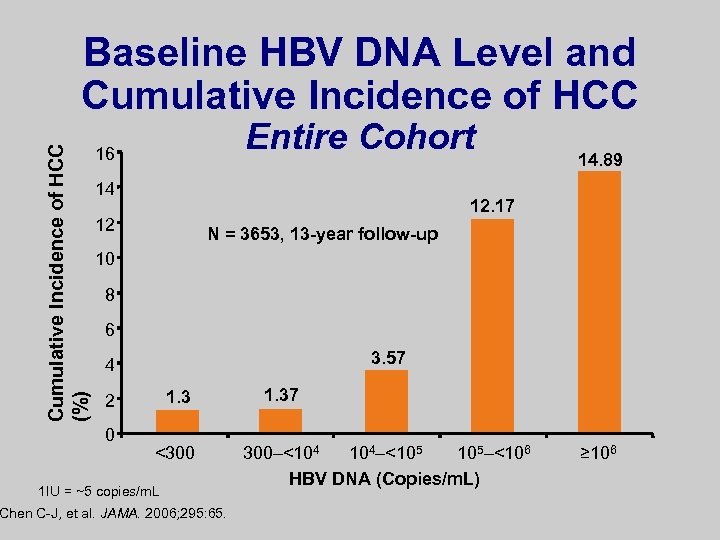

Cumulative Incidence of HCC (%) Baseline HBV DNA Level and Cumulative Incidence of HCC Entire Cohort 16 14 14. 89 12. 17 12 N = 3653, 13 -year follow-up 10 8 6 3. 57 4 1. 3 2 0 <300 1 IU = ~5 copies/m. L Chen C-J, et al. JAMA. 2006; 295: 65. 1. 37 300–<104 104–<105 105–<106 HBV DNA (Copies/m. L) ≥ 106

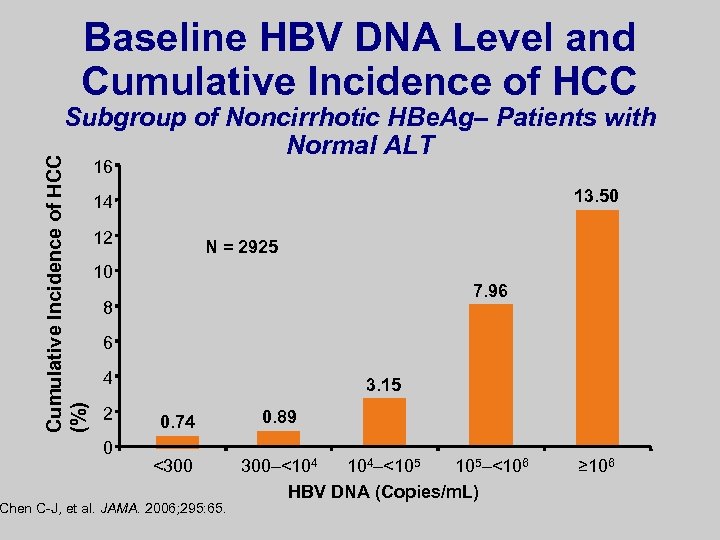

Baseline HBV DNA Level and Cumulative Incidence of HCC (%) Subgroup of Noncirrhotic HBe. Ag– Patients with Normal ALT 16 13. 50 14 12 N = 2925 10 7. 96 8 6 4 2 0 3. 15 0. 74 <300 Chen C-J, et al. JAMA. 2006; 295: 65. 0. 89 300–<104 104–<105 105–<106 HBV DNA (Copies/m. L) ≥ 106

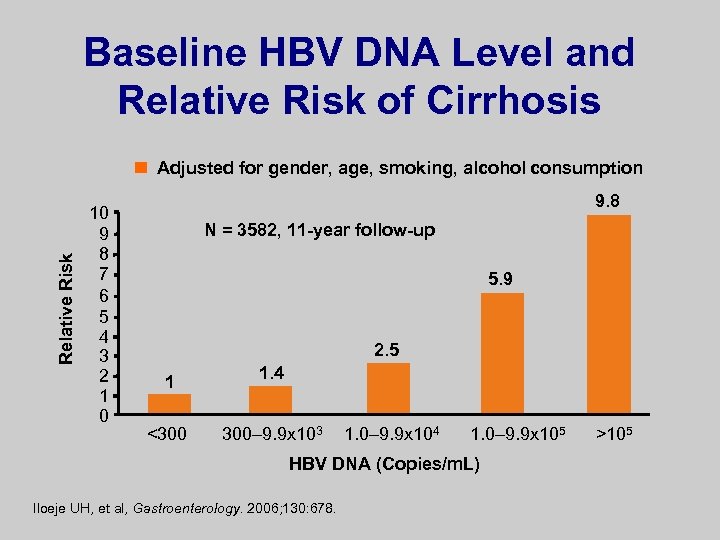

Baseline HBV DNA Level and Relative Risk of Cirrhosis Relative Risk Adjusted for gender, age, smoking, alcohol consumption 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 9. 8 N = 3582, 11 -year follow-up 5. 9 2. 5 1 <300 1. 4 300– 9. 9 x 103 1. 0– 9. 9 x 104 1. 0– 9. 9 x 105 HBV DNA (Copies/m. L) Iloeje UH, et al, Gastroenterology. 2006; 130: 678. >105

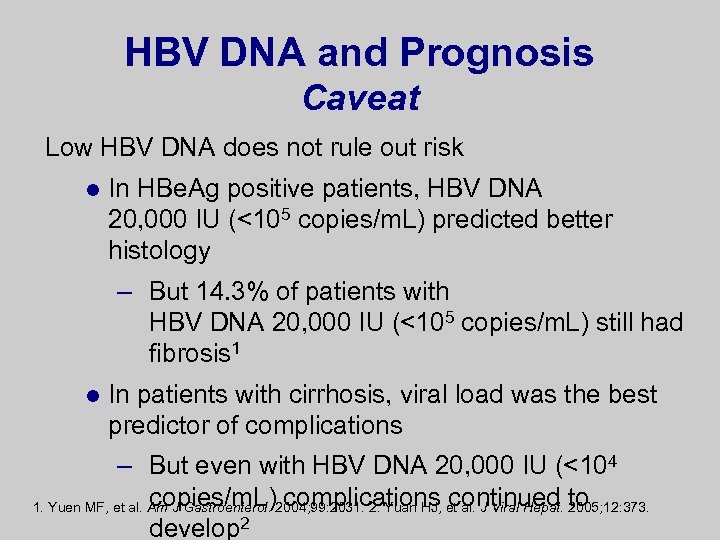

HBV DNA and Prognosis Caveat Low HBV DNA does not rule out risk l In HBe. Ag positive patients, HBV DNA 20, 000 IU (<105 copies/m. L) predicted better histology – But 14. 3% of patients with HBV DNA 20, 000 IU (<105 copies/m. L) still had fibrosis 1 l In patients with cirrhosis, viral load was the best predictor of complications – But even with HBV DNA 20, 000 IU (<104 copies/m. L) complications continued 2005; 12: 373. 1. Yuen MF, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004; 99: 2031. 2. Yuan HJ, et al. J Viral Hepat. to develop 2

Candidacy for anti-HBV Treatment Principle In general, a patient with chronic HBV is a treatment candidate if there is evidence of l Liver disease (abnormal ALT) and l HBV replication (HBV DNA+)

When Do You Initiate anti-HBV Therapy? l l Parameters – HBV DNA levels >104 -5 copies/m. L – ALT levels >1– 2 x ULN Factors – HBe. Ag positive vs HBe. Ag negative – Cirrhosis vs no cirrhosis – Compensated vs decompensated disease

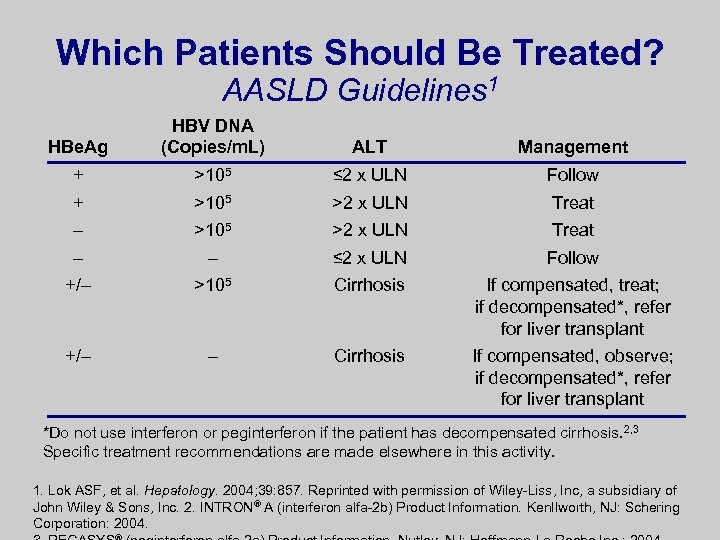

Which Patients Should Be Treated? AASLD Guidelines 1 HBe. Ag HBV DNA (Copies/m. L) ALT Management + >105 ≤ 2 x ULN Follow + >105 >2 x ULN Treat – – ≤ 2 x ULN Follow +/– >105 Cirrhosis If compensated, treat; if decompensated*, refer for liver transplant +/– – Cirrhosis If compensated, observe; if decompensated*, refer for liver transplant *Do not use interferon or peginterferon if the patient has decompensated cirrhosis. 2, 3 Specific treatment recommendations are made elsewhere in this activity. 1. Lok ASF, et al. Hepatology. 2004; 39: 857. Reprinted with permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc, a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2. INTRON® A (interferon alfa-2 b) Product Information. Kenllworth, NJ: Schering Corporation: 2004.

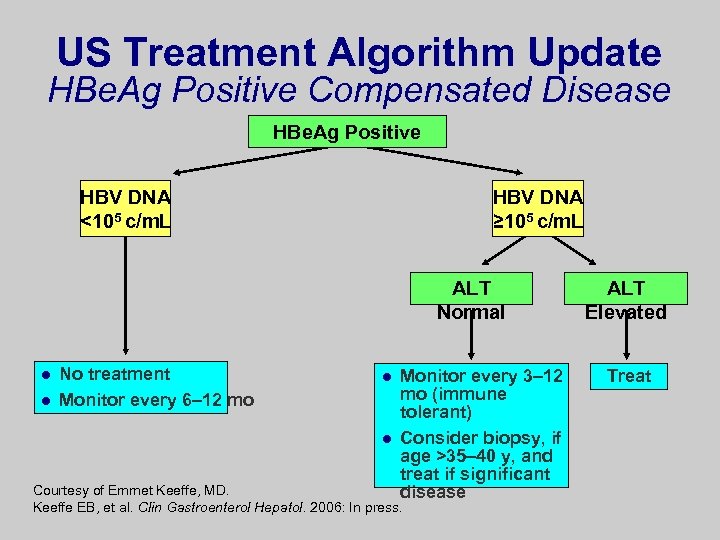

US Treatment Algorithm Update HBe. Ag Positive Compensated Disease HBe. Ag Positive HBV DNA <105 c/m. L HBV DNA ≥ 105 c/m. L ALT Normal l l No treatment Monitor every 6– 12 mo l l Monitor every 3– 12 mo (immune tolerant) Consider biopsy, if age >35– 40 y, and treat if significant disease Courtesy of Emmet Keeffe, MD. Keeffe EB, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006: In press. ALT Elevated Treat

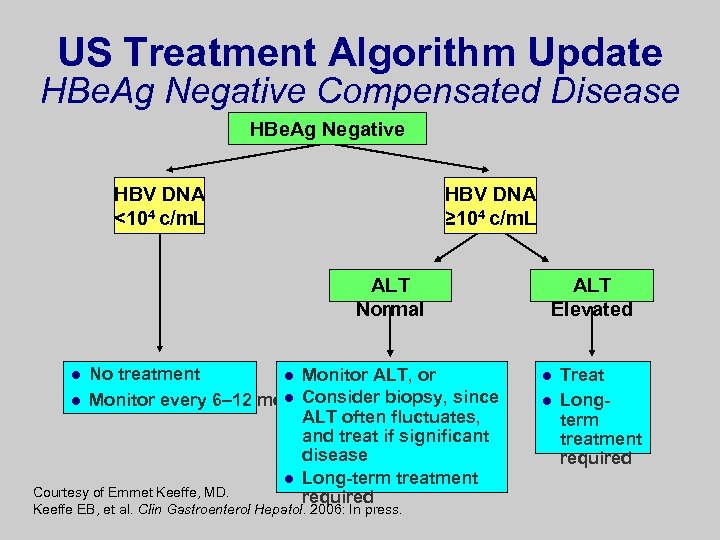

US Treatment Algorithm Update HBe. Ag Negative Compensated Disease HBe. Ag Negative HBV DNA <104 c/m. L HBV DNA ≥ 104 c/m. L ALT Normal No treatment l Monitor ALT, or l Monitor every 6– 12 mol Consider biopsy, since ALT often fluctuates, and treat if significant disease l Long-term treatment Courtesy of Emmet Keeffe, MD. required l Keeffe EB, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006: In press. ALT Elevated l l Treat Longterm treatment required

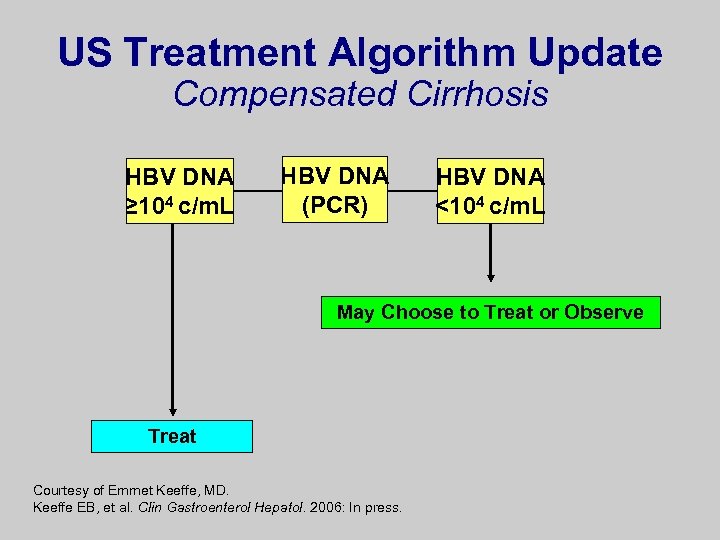

US Treatment Algorithm Update Compensated Cirrhosis HBV DNA ≥ 104 c/m. L HBV DNA (PCR) HBV DNA <104 c/m. L May Choose to Treat or Observe Treat Courtesy of Emmet Keeffe, MD. Keeffe EB, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006: In press.

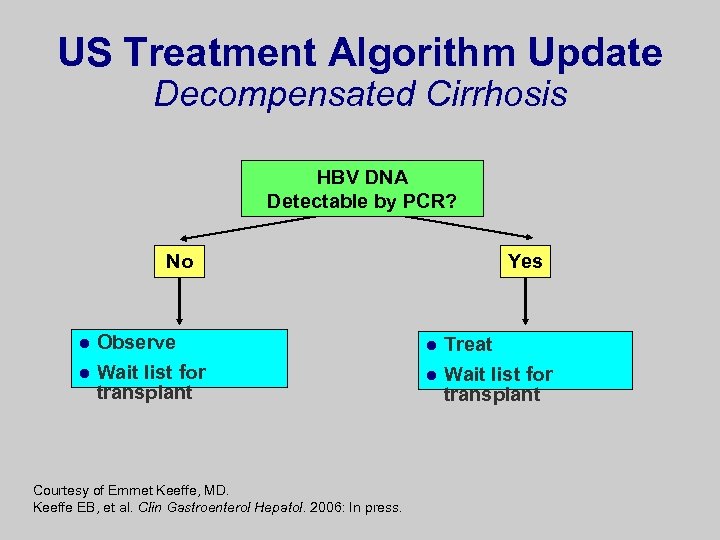

US Treatment Algorithm Update Decompensated Cirrhosis HBV DNA Detectable by PCR? No l l Observe Wait list for transplant Courtesy of Emmet Keeffe, MD. Keeffe EB, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006: In press. Yes l l Treat Wait list for transplant

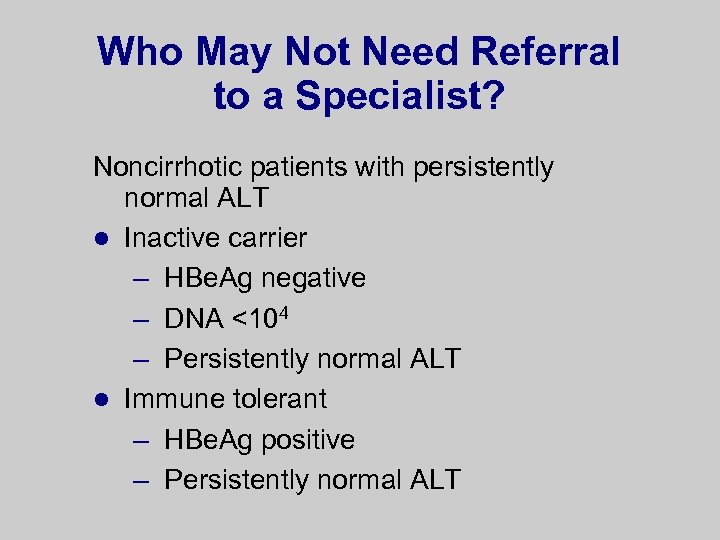

Who May Not Need Referral to a Specialist? Noncirrhotic patients with persistently normal ALT l Inactive carrier – HBe. Ag negative – DNA <104 – Persistently normal ALT l Immune tolerant – HBe. Ag positive – Persistently normal ALT

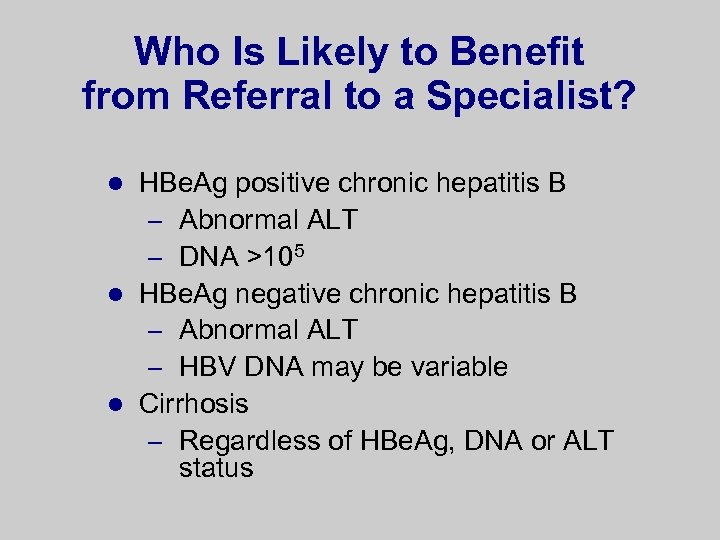

Who Is Likely to Benefit from Referral to a Specialist? HBe. Ag positive chronic hepatitis B – Abnormal ALT – DNA >105 l HBe. Ag negative chronic hepatitis B – Abnormal ALT – HBV DNA may be variable l Cirrhosis – Regardless of HBe. Ag, DNA or ALT status l

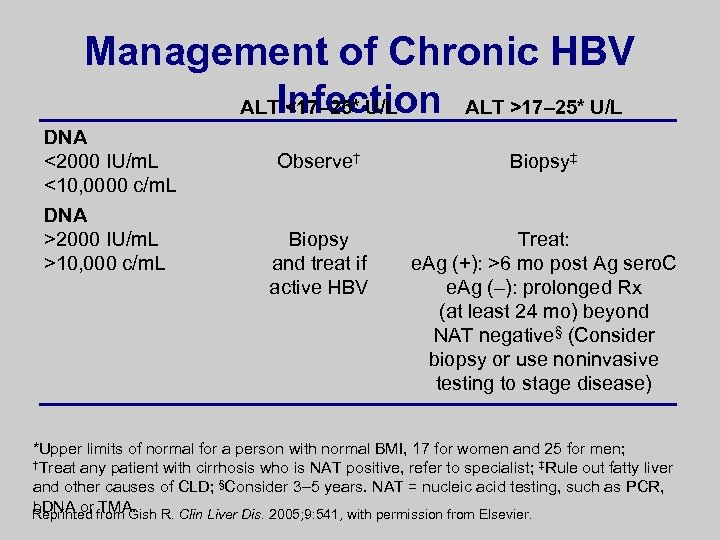

Management of Chronic HBV ALTInfection ALT >17– 25* U/L <17– 25* U/L DNA <2000 IU/m. L <10, 0000 c/m. L DNA >2000 IU/m. L >10, 000 c/m. L Observe† Biopsy‡ Biopsy and treat if active HBV Treat: e. Ag (+): >6 mo post Ag sero. C e. Ag (–): prolonged Rx (at least 24 mo) beyond NAT negative§ (Consider biopsy or use noninvasive testing to stage disease) *Upper limits of normal for a person with normal BMI, 17 for women and 25 for men; †Treat any patient with cirrhosis who is NAT positive, refer to specialist; ‡Rule out fatty liver and other causes of CLD; §Consider 3– 5 years. NAT = nucleic acid testing, such as PCR, b. DNA or TMA. Reprinted from Gish R. Clin Liver Dis. 2005; 9: 541, with permission from Elsevier.

Monitoring for Patients Not Considered for Treatment Check ALT every 3– 6 months – If ALT is persistently elevated, reevaluate for treatment l HCC surveillance in relevant population l Lok ASF, et al. Hepatology. 2001; 34: 1225. Lok ASF, et al. Hepatology. 2004; 39: 857.

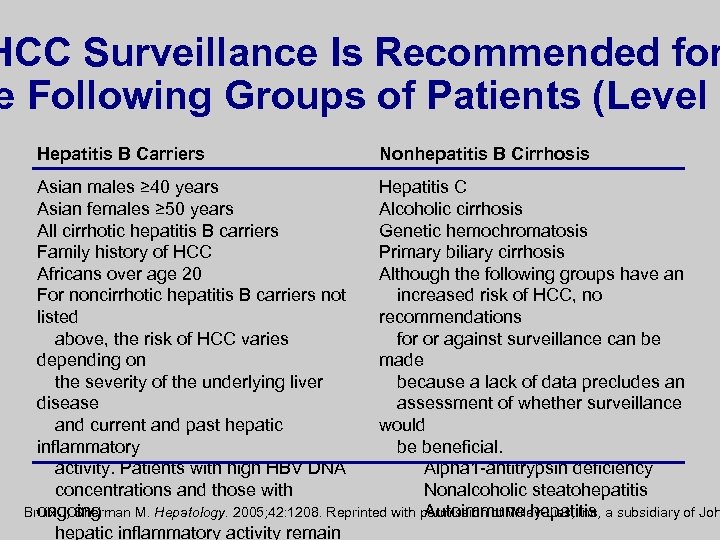

HCC Surveillance Is Recommended for e Following Groups of Patients (Level I Hepatitis B Carriers Nonhepatitis B Cirrhosis Asian males ≥ 40 years Hepatitis C Asian females ≥ 50 years Alcoholic cirrhosis All cirrhotic hepatitis B carriers Genetic hemochromatosis Family history of HCC Primary biliary cirrhosis Africans over age 20 Although the following groups have an For noncirrhotic hepatitis B carriers not increased risk of HCC, no listed recommendations above, the risk of HCC varies for or against surveillance can be depending on made the severity of the underlying liver because a lack of data precludes an disease assessment of whether surveillance and current and past hepatic would inflammatory be beneficial. activity. Patients with high HBV DNA Alpha 1 -antitrypsin deficiency concentrations and those with Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis Bruix J, Sherman M. Hepatology. 2005; 42: 1208. Reprinted with permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc, a subsidiary of Joh ongoing Autoimmune hepatitis hepatic inflammatory activity remain

Counseling of HBV-Infected Patients Limit use of alcohol 1 -3 l Prevent transmission 1, 4 l Screen and vaccinate sexual and household contacts 1, 4 l Vaccinate against hepatitis A 1 l 1. Lok ASF, et al. Hepatology. 2001; 34: 1225. 2. Chevillotte G, et al. Gastroenterology. 1983; 85: 141. 3. Villa E, et al. Lancet. 1982; 2: 1243. 4. CDC. “The Pink Book. ” 8 th ed, 2005.

Treatment of Hepatitis B

Primary Goal of anti-HBV Therapy Preventing Cirrhosis, HCC, and Death Durable Suppression of HBV Replication

Treatment Goal (Endpoints) l Remission of liver disease l Suppression of HBV l HBe. Ag positive HBV – Seroconversion l HBe. Ag negative HBV – Sustained suppression of HBV DNA

Initial Therapy: What Are the Therapeutic Options and Considerations? First-line therapy – Adefovir – Entecavir – Peginterferon alfa-2 a l Lamivudine no longer considered first -line therapy due to high rate of resistance, except in specific settings l Keeffe EB, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006: In press.

Peginterferon l Pegylated recombinant interferon alfa protein/immune modulator l Subcutaneous injection, but less frequent than standard interferon l Dual immunomodulatory and antiviral mode of action l Defined, finite treatment interval l High rate of HBe. Ag seroconversion in wild-type infection l High rate of HBV DNA suppression in precore mutant variant l High rate of HBs. Ag seroconversion l No reports of resistance mutations

Peginterferon Considerations for Use l HBe. Ag positive – Response in genotype A better than B = C, better than D 1, 2 – ALT >80 IU/m. L 2 – HBV DNA <108 copies/m. L 2 – Compensated liver disease guidelines 3 -6 – Monoinfected – No psychiatric or medical contraindications l HBe. Ag negative – No specific genotype populations that benefit over others 7 – Modest number of patients negative by PCR (20%) long term 7 l Consider PEG IFN before nucleos(t)ide therapy due to defined treatment intervals and high HBe. Ag seroconversion rates l Should not be used in decompensated cirrhosis 8 1. Janssen HL, et al. Lancet. 2005; 365: 123. 2. Lau G, et al. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352: 2682. 3. Liaw YF, et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003; 18: 239. 4. De Franchis R, et al. J Hepatol. 2003; 39: S 3. 5. Lok AS, et al. Gastroenterology. 2001; 120: 1828. 6. Lok ASF, et al. Hepatology. 2004; 39: 957. 7. Marcellin P, et al. Hepatology. 2005; 42: 580 A. 8. PEGASYS® (peginterferon alfa-2 a) Product Information. Nutley, NJ: Hoffmann-La Roche Inc. : 2004.

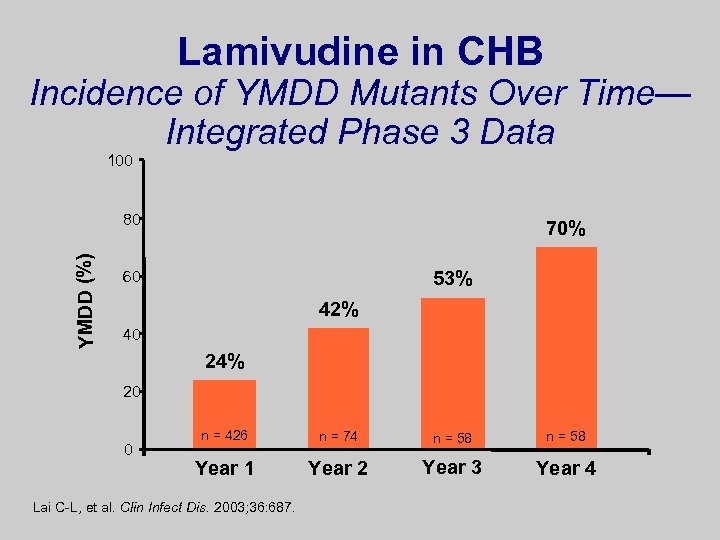

Lamivudine l First oral nucleoside approved for treatment of HBV l Cytidine nucleoside analog: inhibits 1 st-strand DNA synthesis l Extensive database and publications – Half of patients who are HBe. Ag positive undergo seroconversion by 5 years 1 l Safety profile excellent except for resistance l Risk of resistance is high (70%) at 4 years of therapy 2 – Associated with flares and decompensation No longer a first-choice therapy due to high rate of resistance – 1. Guan R, et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001; 16(suppl): A 60. 2. Lai CL, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 36: 687. 3. Keeffe EB, et al. Clin Gatroenterol Hepatol. 2006: In press. 3

Lamivudine in CHB Incidence of YMDD Mutants Over Time— Integrated Phase 3 Data 100 YMDD (%) 80 70% 53% 60 42% 40 24% 20 0 n = 426 n = 74 n = 58 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Lai C-L, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 36: 687.

Adefovir l Adenosine nucleotide analog l First oral medication and first nucleotide approved by regulatory authorities for the treatment of HBV l Inhibits HBV DNA polymerase l Oral bioavailability not affected by food l No significant drug-drug interactions l Rare events of nephrotoxicity (overall risk – low) l Effective against lamivudine-resistant Product Insert. mutants HEPSERA®

Safety of Adefovir Dipivoxil Over 4– 5 Years l Resistance is 29% at 5 years of use in HBe. Ag negative patients 1 l Resistance is more likely if patients are lamivudine resistant and switched to adefovir 2 l Renal safety – Infrequent (3%) increases in creatinine ≥ 0. 5 mg/d. L n Maximum value 1. 5 mg/d. L Maximum increase 0. 8 mg/d. L 1. Borroto-Esoda n et al. J Hepatol. 2006; 44(Suppl 2): 179. K, 2. Lee YS, et al. Hepatology. 2006; 43: 1385. 3. Hadziyannis S, et al. J Hepatol. 2006; 44(Suppl 2): 283.

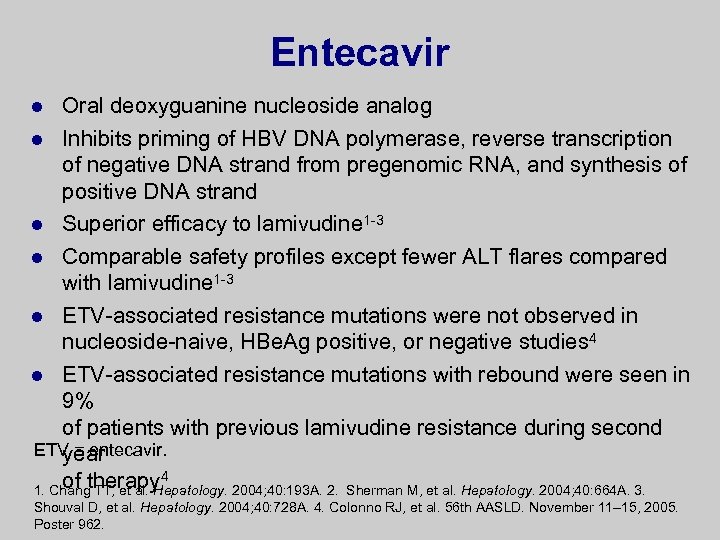

Entecavir Oral deoxyguanine nucleoside analog l Inhibits priming of HBV DNA polymerase, reverse transcription of negative DNA strand from pregenomic RNA, and synthesis of positive DNA strand l Superior efficacy to lamivudine 1 -3 l Comparable safety profiles except fewer ALT flares compared with lamivudine 1 -3 l ETV-associated resistance mutations were not observed in nucleoside-naive, HBe. Ag positive, or negative studies 4 l ETV-associated resistance mutations with rebound were seen in 9% of patients with previous lamivudine resistance during second ETV = entecavir. year of therapy 4 1. Chang TT, et al. Hepatology. 2004; 40: 193 A. 2. Sherman M, et al. Hepatology. 2004; 40: 664 A. 3. l Shouval D, et al. Hepatology. 2004; 40: 728 A. 4. Colonno RJ, et al. 56 th AASLD. November 11– 15, 2005. Poster 962.

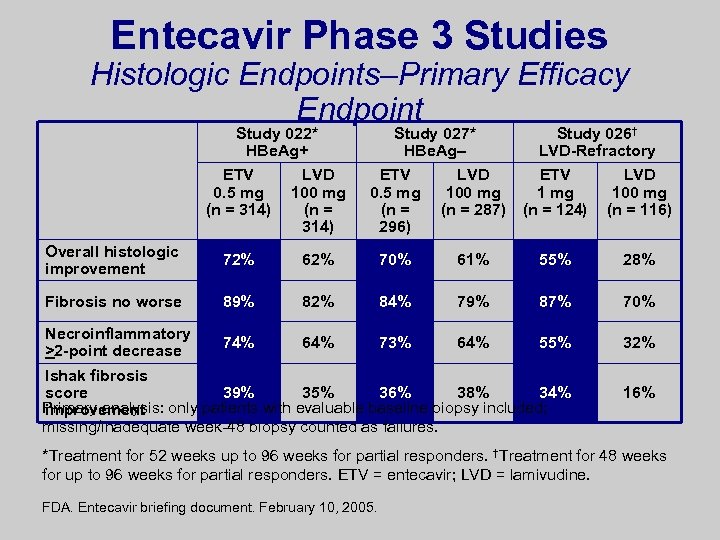

Entecavir Phase 3 Studies Histologic Endpoints–Primary Efficacy Endpoint Study 022* HBe. Ag+ Study 027* HBe. Ag– Study 026† LVD-Refractory ETV 0. 5 mg (n = 314) LVD 100 mg (n = 314) ETV 0. 5 mg (n = 296) LVD 100 mg (n = 287) ETV 1 mg (n = 124) LVD 100 mg (n = 116) Overall histologic improvement 72% 62% 70% 61% 55% 28% Fibrosis no worse 89% 82% 84% 79% 87% 70% Necroinflammatory >2 -point decrease 74% 64% 73% 64% 55% 32% Ishak fibrosis score 39% 35% 36% 38% 34% Primary analysis: only patients with evaluable baseline biopsy included; improvement missing/inadequate week-48 biopsy counted as failures. 16% *Treatment for 52 weeks up to 96 weeks for partial responders. †Treatment for 48 weeks for up to 96 weeks for partial responders. ETV = entecavir; LVD = lamivudine. FDA. Entecavir briefing document. February 10, 2005.

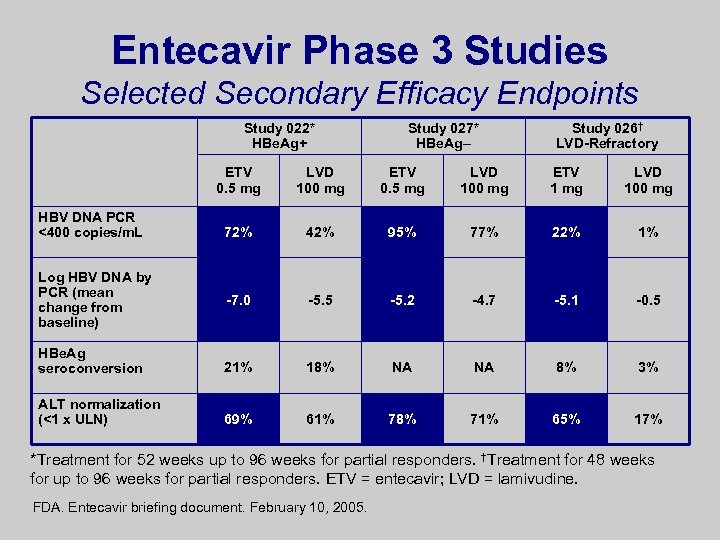

Entecavir Phase 3 Studies Selected Secondary Efficacy Endpoints Study 022* HBe. Ag+ Study 027* HBe. Ag– Study 026† LVD-Refractory ETV 0. 5 mg LVD 100 mg ETV 1 mg LVD 100 mg 72% 42% 95% 77% 22% 1% -7. 0 -5. 5 -5. 2 -4. 7 -5. 1 -0. 5 HBe. Ag seroconversion 21% 18% NA NA 8% 3% ALT normalization (<1 x ULN) 69% 61% 78% 71% 65% 17% HBV DNA PCR <400 copies/m. L Log HBV DNA by PCR (mean change from baseline) *Treatment for 52 weeks up to 96 weeks for partial responders. †Treatment for 48 weeks for up to 96 weeks for partial responders. ETV = entecavir; LVD = lamivudine. FDA. Entecavir briefing document. February 10, 2005.

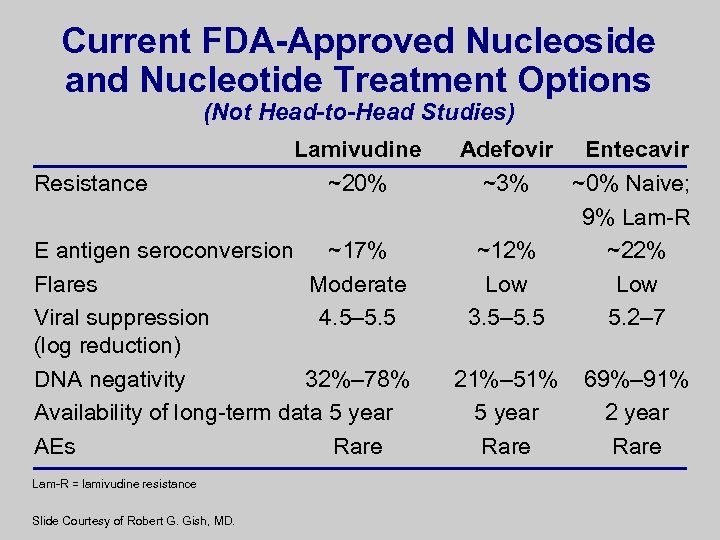

Current FDA-Approved Nucleoside and Nucleotide Treatment Options (Not Head-to-Head Studies) Resistance Lamivudine ~20% E antigen seroconversion ~17% Flares Moderate Viral suppression 4. 5– 5. 5 (log reduction) DNA negativity 32%– 78% Availability of long-term data 5 year AEs Rare Lam-R = lamivudine resistance Slide Courtesy of Robert G. Gish, MD. Adefovir Entecavir ~3% ~0% Naive; 9% Lam-R ~12% ~22% Low 3. 5– 5. 5 5. 2– 7 21%– 51% 5 year Rare 69%– 91% 2 year Rare

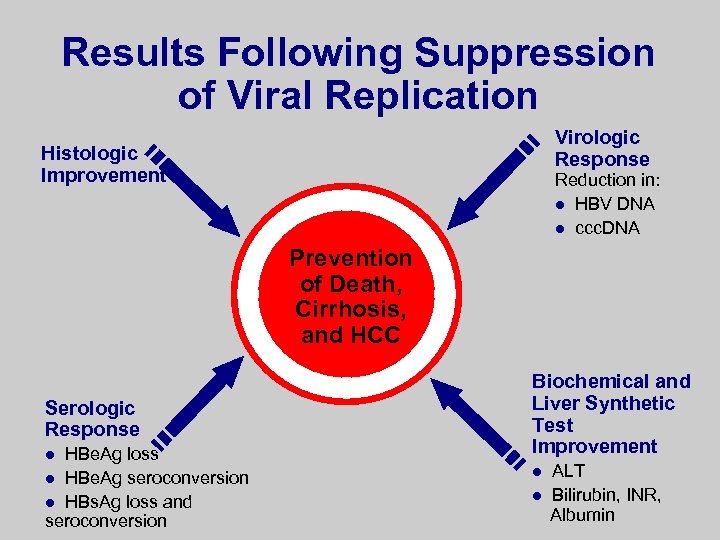

Results Following Suppression of Viral Replication Virologic Response Histologic Improvement Reduction in: l HBV DNA l ccc. DNA Prevention of Death, Cirrhosis, and HCC Serologic Response HBe. Ag loss l HBe. Ag seroconversion l HBs. Ag loss and seroconversion l Biochemical and Liver Synthetic Test Improvement l l ALT Bilirubin, INR, Albumin

Summary l HBV infection is a worldwide epidemiologic and clinical challenge l Screening at-risk individuals identifies those with HBV infection l Pretreatment evaluation includes history, physical exam, and additional diagnostic testing l Candidates for anti-HBV treatment include patients with active liver disease and high levels of HBV replication l Refer HBs. Ag positive patients for treatment with entecavir, adefovir, or peginterferon

2ea16e00cccb0e50240db28c04167794.ppt