89ea8daf8c8a03863a49b9420450c62b.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 89

Operating Systems Certificate Program in Software Development CSE-TC and CSIM, AIT September -- November, 2003 5. Process Synchronization (Ch. 6, S&G) ch 7 in the 6 th ed. v Objectives – describe the synchronization problem and some common mechanisms for solving it OSes: 5. Synch 1

Operating Systems Certificate Program in Software Development CSE-TC and CSIM, AIT September -- November, 2003 5. Process Synchronization (Ch. 6, S&G) ch 7 in the 6 th ed. v Objectives – describe the synchronization problem and some common mechanisms for solving it OSes: 5. Synch 1

Contents 1. Motivation: Bounded Buffer 2. Critical Sections 3. Synchronization Hardware 4. Semaphores 5. Synchronization Examples OSes: 5. Synch continued 2

Contents 1. Motivation: Bounded Buffer 2. Critical Sections 3. Synchronization Hardware 4. Semaphores 5. Synchronization Examples OSes: 5. Synch continued 2

6. Problems with Semaphores 7. Critical Regions 8. Monitors 9. Synchronization in Solaris 2 10. Atomic Transactions OSes: 5. Synch 3

6. Problems with Semaphores 7. Critical Regions 8. Monitors 9. Synchronization in Solaris 2 10. Atomic Transactions OSes: 5. Synch 3

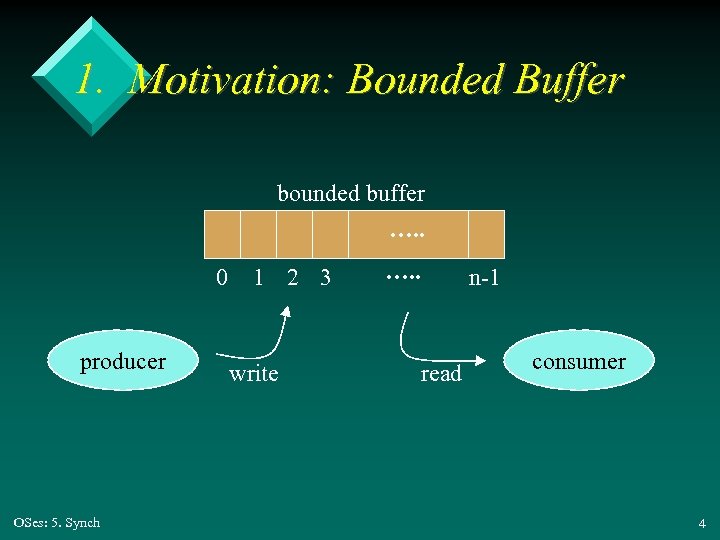

1. Motivation: Bounded Buffer bounded buffer …. . 0 producer OSes: 5. Synch 1 2 3 write …. . n-1 read consumer 4

1. Motivation: Bounded Buffer bounded buffer …. . 0 producer OSes: 5. Synch 1 2 3 write …. . n-1 read consumer 4

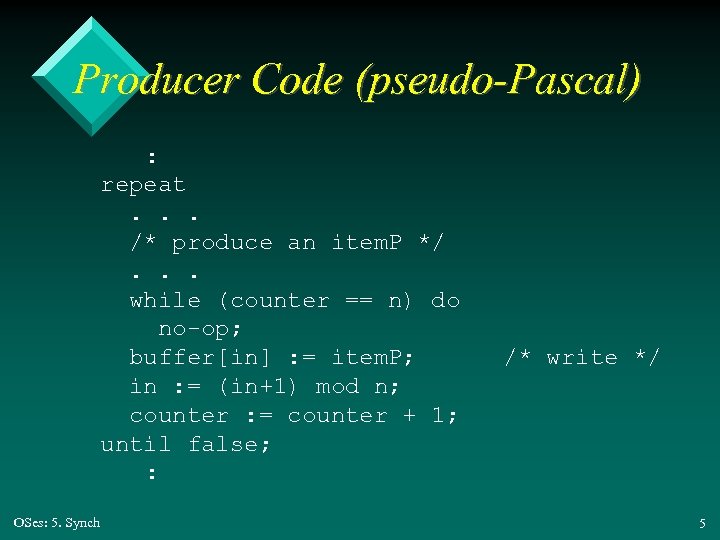

Producer Code (pseudo-Pascal) : repeat. . . /* produce an item. P */. . . while (counter == n) do no-op; buffer[in] : = item. P; in : = (in+1) mod n; counter : = counter + 1; until false; : OSes: 5. Synch /* write */ 5

Producer Code (pseudo-Pascal) : repeat. . . /* produce an item. P */. . . while (counter == n) do no-op; buffer[in] : = item. P; in : = (in+1) mod n; counter : = counter + 1; until false; : OSes: 5. Synch /* write */ 5

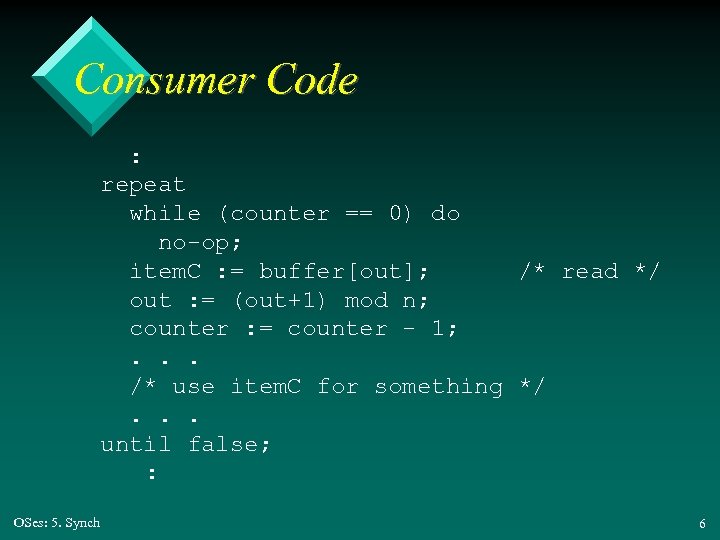

Consumer Code : repeat while (counter == 0) do no-op; item. C : = buffer[out]; /* read */ out : = (out+1) mod n; counter : = counter - 1; . . . /* use item. C for something */. . . until false; : OSes: 5. Synch 6

Consumer Code : repeat while (counter == 0) do no-op; item. C : = buffer[out]; /* read */ out : = (out+1) mod n; counter : = counter - 1; . . . /* use item. C for something */. . . until false; : OSes: 5. Synch 6

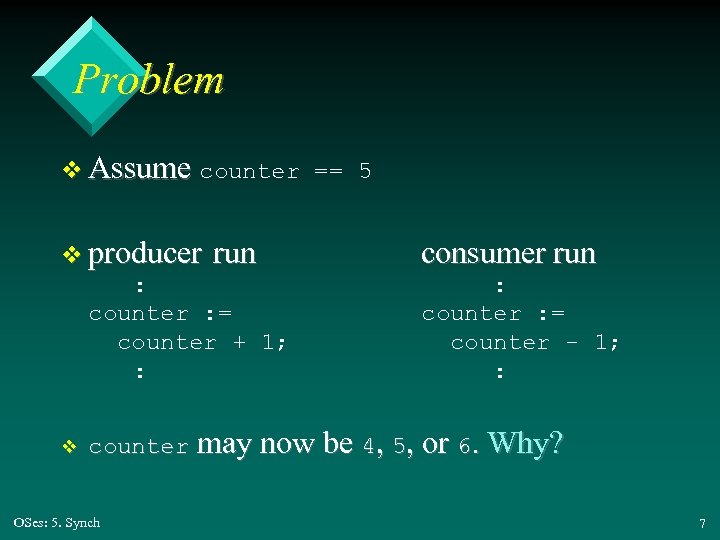

Problem v Assume counter == 5 v producer run : counter : = counter + 1; : v consumer run : counter : = counter - 1; : counter may now be 4, 5, or 6. Why? OSes: 5. Synch 7

Problem v Assume counter == 5 v producer run : counter : = counter + 1; : v consumer run : counter : = counter - 1; : counter may now be 4, 5, or 6. Why? OSes: 5. Synch 7

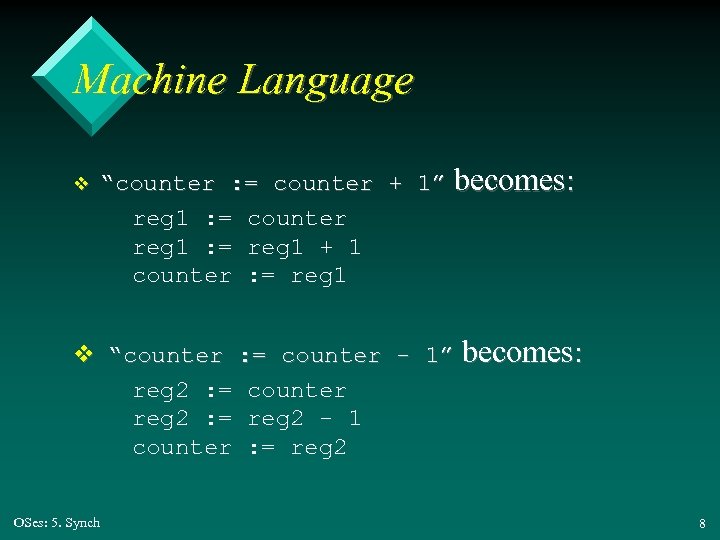

Machine Language v “counter : = counter + 1” becomes: reg 1 : = counter reg 1 : = reg 1 + 1 counter : = reg 1 v “counter : = counter - 1” becomes: reg 2 : = counter reg 2 : = reg 2 - 1 counter : = reg 2 OSes: 5. Synch 8

Machine Language v “counter : = counter + 1” becomes: reg 1 : = counter reg 1 : = reg 1 + 1 counter : = reg 1 v “counter : = counter - 1” becomes: reg 2 : = counter reg 2 : = reg 2 - 1 counter : = reg 2 OSes: 5. Synch 8

Execution Interleaving v The concurrent execution of the two processes is achieved by interleaving the execution of each v There are many possible interleavings, which can lead to different values for counter – a different interleaving may occur each time the processes are run OSes: 5. Synch 9

Execution Interleaving v The concurrent execution of the two processes is achieved by interleaving the execution of each v There are many possible interleavings, which can lead to different values for counter – a different interleaving may occur each time the processes are run OSes: 5. Synch 9

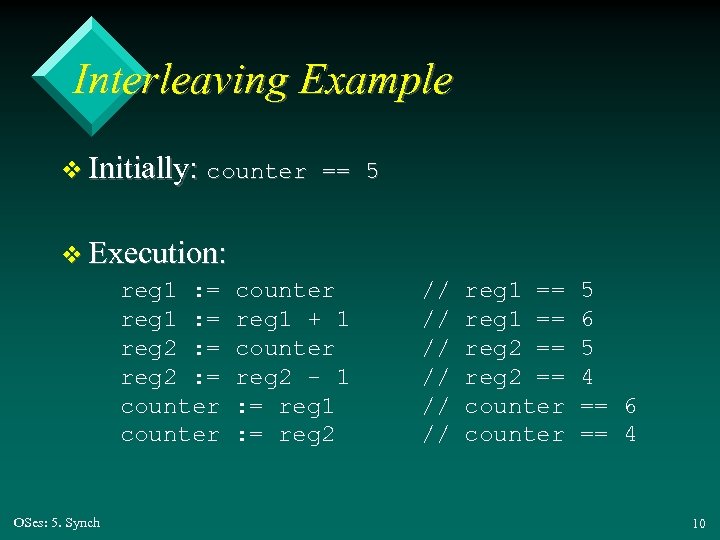

Interleaving Example v Initially: counter == 5 v Execution: reg 1 : = counter reg 1 : = reg 1 + 1 reg 2 : = counter reg 2 : = reg 2 - 1 counter : = reg 2 OSes: 5. Synch // // // reg 1 == reg 2 == counter 5 6 5 4 == 6 == 4 10

Interleaving Example v Initially: counter == 5 v Execution: reg 1 : = counter reg 1 : = reg 1 + 1 reg 2 : = counter reg 2 : = reg 2 - 1 counter : = reg 2 OSes: 5. Synch // // // reg 1 == reg 2 == counter 5 6 5 4 == 6 == 4 10

Summary of Problem v Incorrect results occur because of a race condition over the modification of the shared variable (counter) v The processes must be synchronized while they are sharing data so that the result is predictable and correct OSes: 5. Synch 11

Summary of Problem v Incorrect results occur because of a race condition over the modification of the shared variable (counter) v The processes must be synchronized while they are sharing data so that the result is predictable and correct OSes: 5. Synch 11

2. Critical Sections v A critical section is a segment of code which can only be executed by one process at a time – all other processes are excluded – called mutual exclusion OSes: 5. Synch 12

2. Critical Sections v A critical section is a segment of code which can only be executed by one process at a time – all other processes are excluded – called mutual exclusion OSes: 5. Synch 12

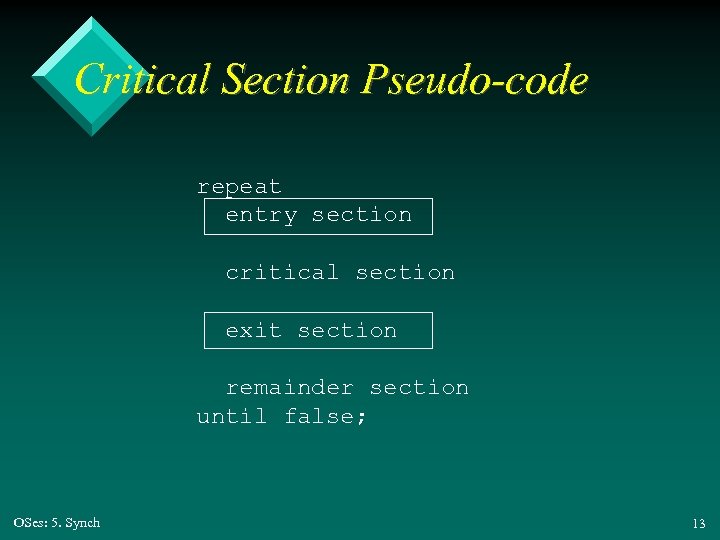

Critical Section Pseudo-code repeat entry section critical section exit section remainder section until false; OSes: 5. Synch 13

Critical Section Pseudo-code repeat entry section critical section exit section remainder section until false; OSes: 5. Synch 13

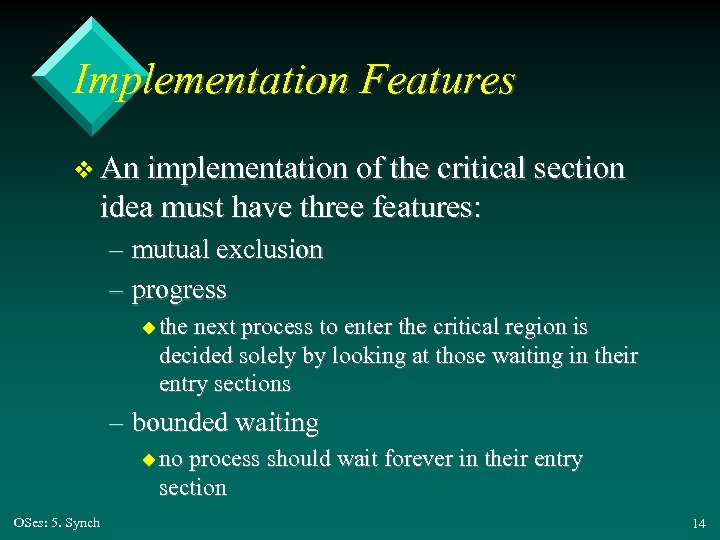

Implementation Features v An implementation of the critical section idea must have three features: – mutual exclusion – progress u the next process to enter the critical region is decided solely by looking at those waiting in their entry sections – bounded waiting u no process should wait forever in their entry section OSes: 5. Synch 14

Implementation Features v An implementation of the critical section idea must have three features: – mutual exclusion – progress u the next process to enter the critical region is decided solely by looking at those waiting in their entry sections – bounded waiting u no process should wait forever in their entry section OSes: 5. Synch 14

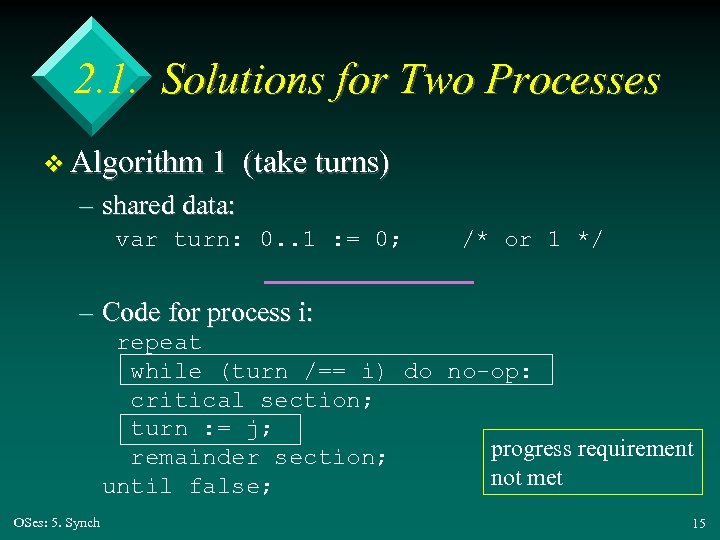

2. 1. Solutions for Two Processes v Algorithm 1 (take turns) – shared data: var turn: 0. . 1 : = 0; /* or 1 */ – Code for process i: repeat while (turn /== i) do no-op: critical section; turn : = j; progress requirement remainder section; not met until false; OSes: 5. Synch 15

2. 1. Solutions for Two Processes v Algorithm 1 (take turns) – shared data: var turn: 0. . 1 : = 0; /* or 1 */ – Code for process i: repeat while (turn /== i) do no-op: critical section; turn : = j; progress requirement remainder section; not met until false; OSes: 5. Synch 15

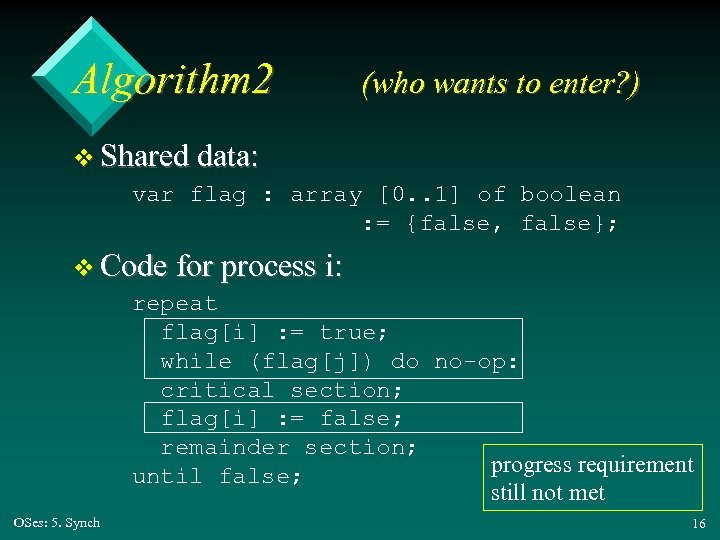

Algorithm 2 (who wants to enter? ) v Shared data: var flag : array [0. . 1] of boolean : = {false, false}; v Code for process i: repeat flag[i] : = true; while (flag[j]) do no-op: critical section; flag[i] : = false; remainder section; progress requirement until false; still not met OSes: 5. Synch 16

Algorithm 2 (who wants to enter? ) v Shared data: var flag : array [0. . 1] of boolean : = {false, false}; v Code for process i: repeat flag[i] : = true; while (flag[j]) do no-op: critical section; flag[i] : = false; remainder section; progress requirement until false; still not met OSes: 5. Synch 16

Algorithm 3 (Peterson, 1981) v Combines algorithms 1 and 2 – who wants to enter? – if both do then take turns v Shared data: var flag : array [0. . 1] of boolean : = {false, false}; var turn : 0. . 1 : = 0; OSes: 5. Synch /* or 1 */ continued 17

Algorithm 3 (Peterson, 1981) v Combines algorithms 1 and 2 – who wants to enter? – if both do then take turns v Shared data: var flag : array [0. . 1] of boolean : = {false, false}; var turn : 0. . 1 : = 0; OSes: 5. Synch /* or 1 */ continued 17

![v Code for process i: repeat flag[i] : = true; turn : = j; v Code for process i: repeat flag[i] : = true; turn : = j;](https://present5.com/presentation/89ea8daf8c8a03863a49b9420450c62b/image-18.jpg) v Code for process i: repeat flag[i] : = true; turn : = j; while (flag[j] and turn == j) do no-op: critical section; flag[i] : = false; remainder section; until false; OSes: 5. Synch 18

v Code for process i: repeat flag[i] : = true; turn : = j; while (flag[j] and turn == j) do no-op: critical section; flag[i] : = false; remainder section; until false; OSes: 5. Synch 18

2. 2. Multiple Processes v Uses the bakery algorithm (Lamport 1974). v Each customer (process) receives a number on entering the store (the entry section). v The customer with the lowest number is served first (enters the critical region). OSes: 5. Synch continued 19

2. 2. Multiple Processes v Uses the bakery algorithm (Lamport 1974). v Each customer (process) receives a number on entering the store (the entry section). v The customer with the lowest number is served first (enters the critical region). OSes: 5. Synch continued 19

v If two customers have the same number, then the one with the lowest name is served first – names are unique and ordered OSes: 5. Synch 20

v If two customers have the same number, then the one with the lowest name is served first – names are unique and ordered OSes: 5. Synch 20

![Pseudo-code v Shared data: var choosing : array [0. . n-1] of boolean : Pseudo-code v Shared data: var choosing : array [0. . n-1] of boolean :](https://present5.com/presentation/89ea8daf8c8a03863a49b9420450c62b/image-21.jpg) Pseudo-code v Shared data: var choosing : array [0. . n-1] of boolean : = {false. . false}; var number : array [0. . n-1] of integer : = {0. . 0}; OSes: 5. Synch continued 21

Pseudo-code v Shared data: var choosing : array [0. . n-1] of boolean : = {false. . false}; var number : array [0. . n-1] of integer : = {0. . 0}; OSes: 5. Synch continued 21

![v Code for process i: repeat choosing[i] : = true; number[i] : = max(number[0], v Code for process i: repeat choosing[i] : = true; number[i] : = max(number[0],](https://present5.com/presentation/89ea8daf8c8a03863a49b9420450c62b/image-22.jpg) v Code for process i: repeat choosing[i] : = true; number[i] : = max(number[0], number[1], . . . , number[n-1]) + 1; choosing[i] : = false; for j : = 0 to n-1 do begin while (choosing[j]) do no-op; while ((number[j] /== 0) and ((number[j], j) < (number[i], i))) do no-op; end; critical section number[i] : = 0; remainder section until false; OSes: 5. Synch 22

v Code for process i: repeat choosing[i] : = true; number[i] : = max(number[0], number[1], . . . , number[n-1]) + 1; choosing[i] : = false; for j : = 0 to n-1 do begin while (choosing[j]) do no-op; while ((number[j] /== 0) and ((number[j], j) < (number[i], i))) do no-op; end; critical section number[i] : = 0; remainder section until false; OSes: 5. Synch 22

3. Synchronization Hardware v Hardware solutions can make software synchronization much simpler v On a uniprocessor, the OS can disallow interrupts while a shared variable is being changed – not so easy on multiprocessors OSes: 5. Synch continued 23

3. Synchronization Hardware v Hardware solutions can make software synchronization much simpler v On a uniprocessor, the OS can disallow interrupts while a shared variable is being changed – not so easy on multiprocessors OSes: 5. Synch continued 23

v Typical hardware support: – atomic test-and-set of a boolean (byte) – atomic swap of booleans (bytes) v Atomic means an uninterruptable ‘unit’ of work. OSes: 5. Synch 24

v Typical hardware support: – atomic test-and-set of a boolean (byte) – atomic swap of booleans (bytes) v Atomic means an uninterruptable ‘unit’ of work. OSes: 5. Synch 24

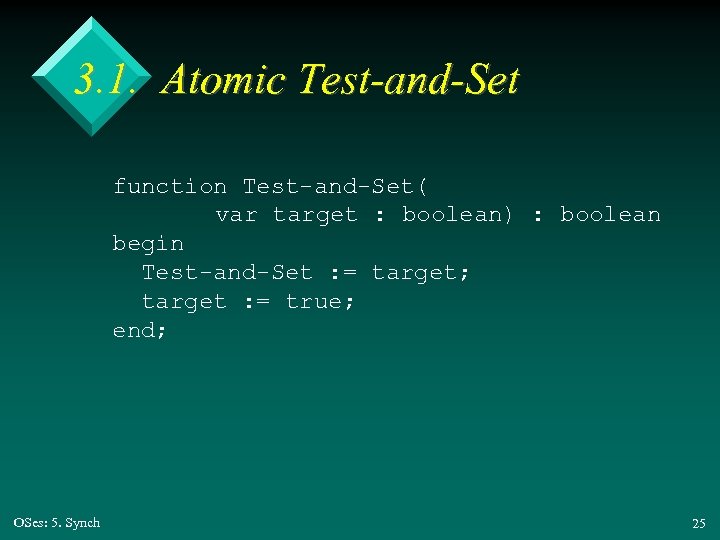

3. 1. Atomic Test-and-Set function Test-and-Set( var target : boolean) : boolean begin Test-and-Set : = target; target : = true; end; OSes: 5. Synch 25

3. 1. Atomic Test-and-Set function Test-and-Set( var target : boolean) : boolean begin Test-and-Set : = target; target : = true; end; OSes: 5. Synch 25

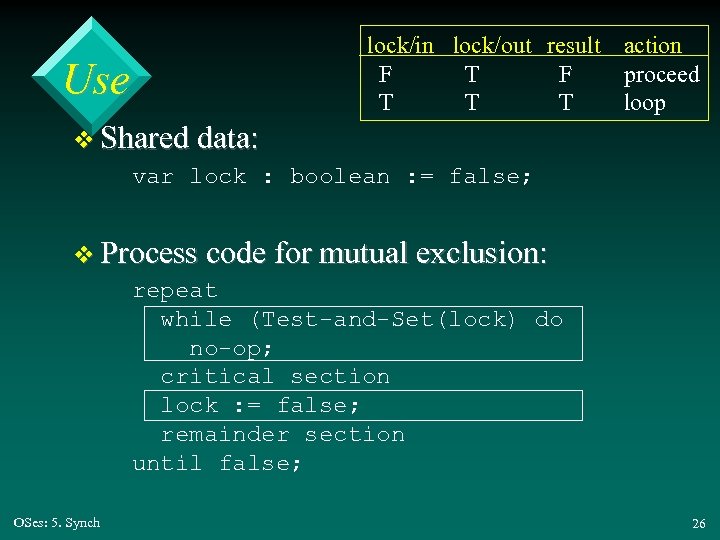

Use lock/in lock/out result action F T F proceed T T T loop v Shared data: var lock : boolean : = false; v Process code for mutual exclusion: repeat while (Test-and-Set(lock) do no-op; critical section lock : = false; remainder section until false; OSes: 5. Synch 26

Use lock/in lock/out result action F T F proceed T T T loop v Shared data: var lock : boolean : = false; v Process code for mutual exclusion: repeat while (Test-and-Set(lock) do no-op; critical section lock : = false; remainder section until false; OSes: 5. Synch 26

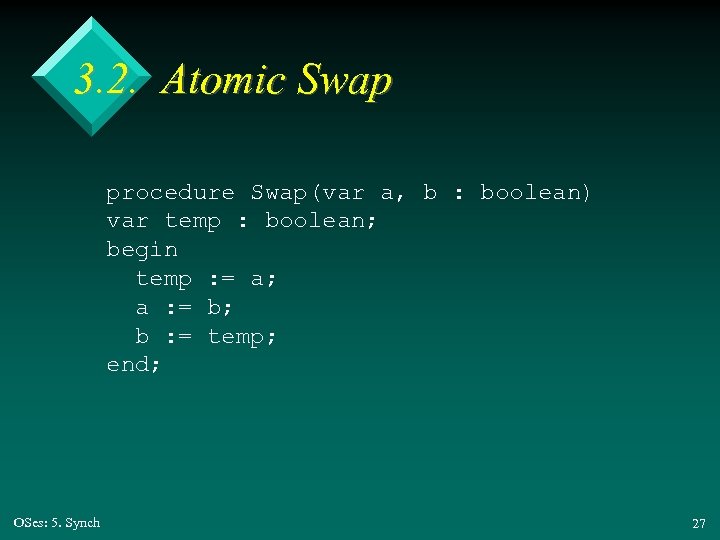

3. 2. Atomic Swap procedure Swap(var a, b : boolean) var temp : boolean; begin temp : = a; a : = b; b : = temp; end; OSes: 5. Synch 27

3. 2. Atomic Swap procedure Swap(var a, b : boolean) var temp : boolean; begin temp : = a; a : = b; b : = temp; end; OSes: 5. Synch 27

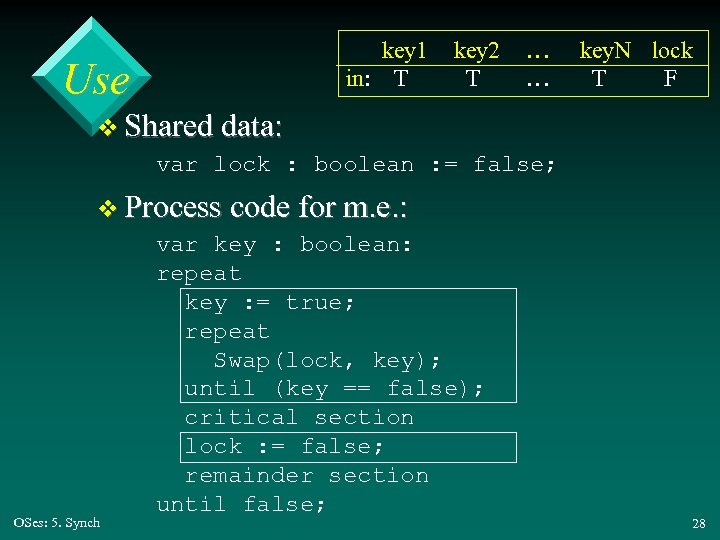

Use key 1 in: T key 2 T … … key. N lock T F v Shared data: var lock : boolean : = false; v Process code for m. e. : var key : boolean: repeat key : = true; repeat Swap(lock, key); until (key == false); critical section lock : = false; remainder section until false; OSes: 5. Synch 28

Use key 1 in: T key 2 T … … key. N lock T F v Shared data: var lock : boolean : = false; v Process code for m. e. : var key : boolean: repeat key : = true; repeat Swap(lock, key); until (key == false); critical section lock : = false; remainder section until false; OSes: 5. Synch 28

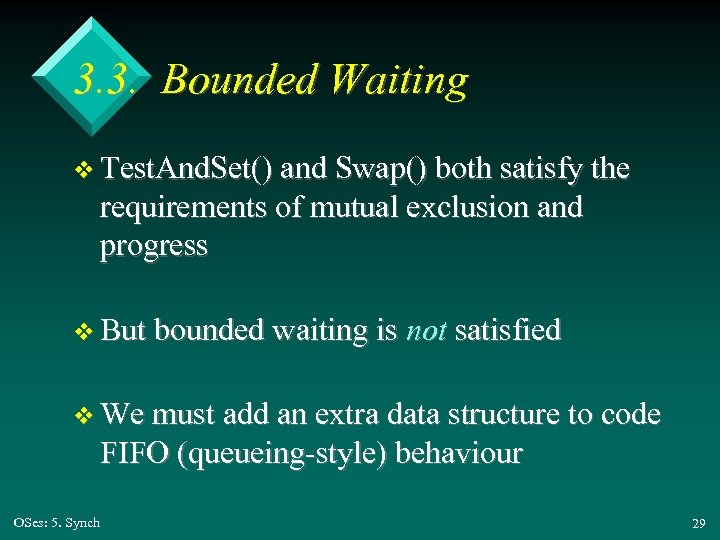

3. 3. Bounded Waiting v Test. And. Set() and Swap() both satisfy the requirements of mutual exclusion and progress v But bounded waiting is not satisfied v We must add an extra data structure to code FIFO (queueing-style) behaviour OSes: 5. Synch 29

3. 3. Bounded Waiting v Test. And. Set() and Swap() both satisfy the requirements of mutual exclusion and progress v But bounded waiting is not satisfied v We must add an extra data structure to code FIFO (queueing-style) behaviour OSes: 5. Synch 29

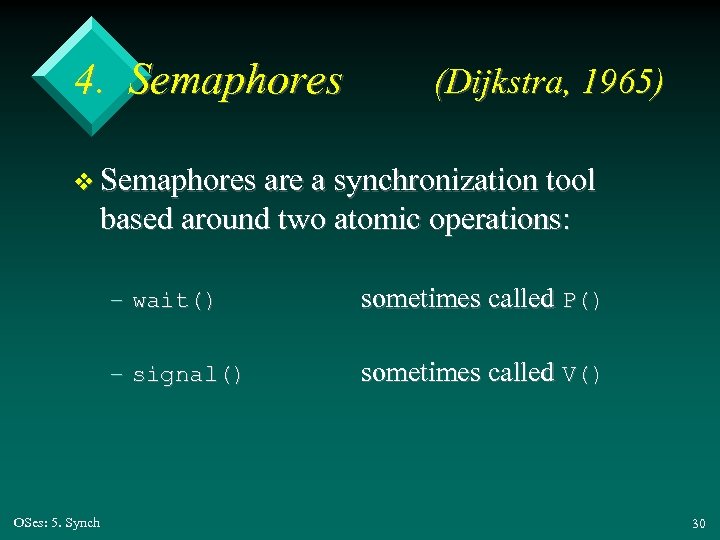

4. Semaphores (Dijkstra, 1965) v Semaphores are a synchronization tool based around two atomic operations: – wait() – signal() OSes: 5. Synch sometimes called P() sometimes called V() 30

4. Semaphores (Dijkstra, 1965) v Semaphores are a synchronization tool based around two atomic operations: – wait() – signal() OSes: 5. Synch sometimes called P() sometimes called V() 30

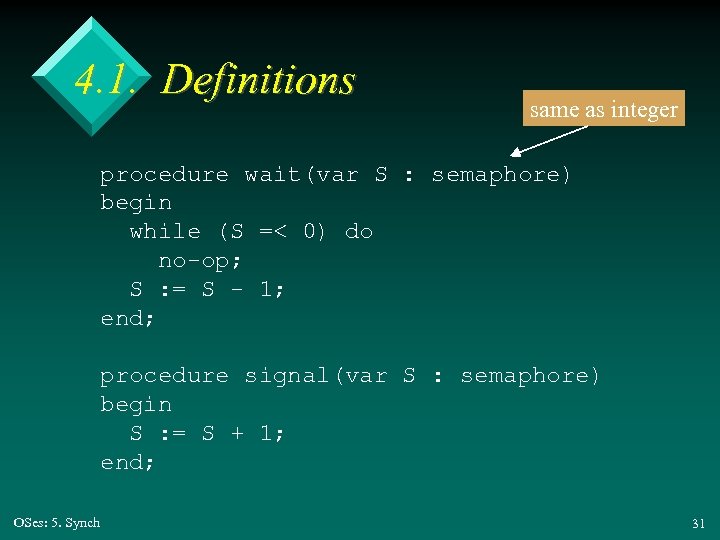

4. 1. Definitions same as integer procedure wait(var S : semaphore) begin while (S =< 0) do no-op; S : = S - 1; end; procedure signal(var S : semaphore) begin S : = S + 1; end; OSes: 5. Synch 31

4. 1. Definitions same as integer procedure wait(var S : semaphore) begin while (S =< 0) do no-op; S : = S - 1; end; procedure signal(var S : semaphore) begin S : = S + 1; end; OSes: 5. Synch 31

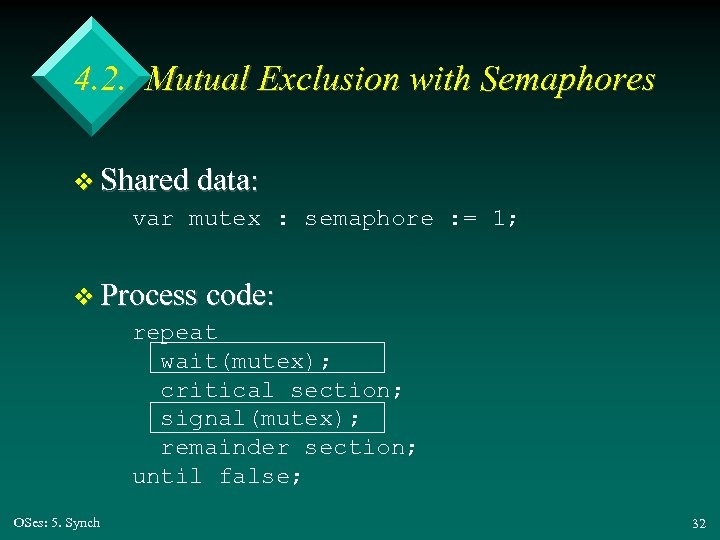

4. 2. Mutual Exclusion with Semaphores v Shared data: var mutex : semaphore : = 1; v Process code: repeat wait(mutex); critical section; signal(mutex); remainder section; until false; OSes: 5. Synch 32

4. 2. Mutual Exclusion with Semaphores v Shared data: var mutex : semaphore : = 1; v Process code: repeat wait(mutex); critical section; signal(mutex); remainder section; until false; OSes: 5. Synch 32

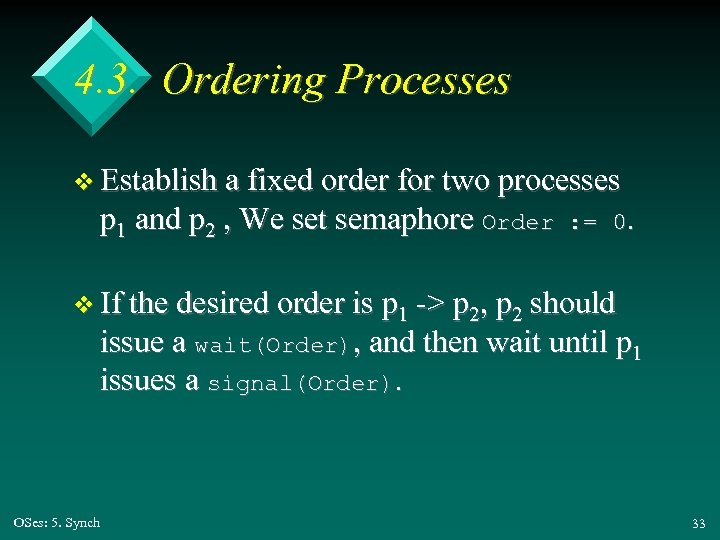

4. 3. Ordering Processes v Establish a fixed order for two processes p 1 and p 2 , We set semaphore Order : = 0. v If the desired order is p 1 -> p 2, p 2 should issue a wait(Order), and then wait until p 1 issues a signal(Order). OSes: 5. Synch 33

4. 3. Ordering Processes v Establish a fixed order for two processes p 1 and p 2 , We set semaphore Order : = 0. v If the desired order is p 1 -> p 2, p 2 should issue a wait(Order), and then wait until p 1 issues a signal(Order). OSes: 5. Synch 33

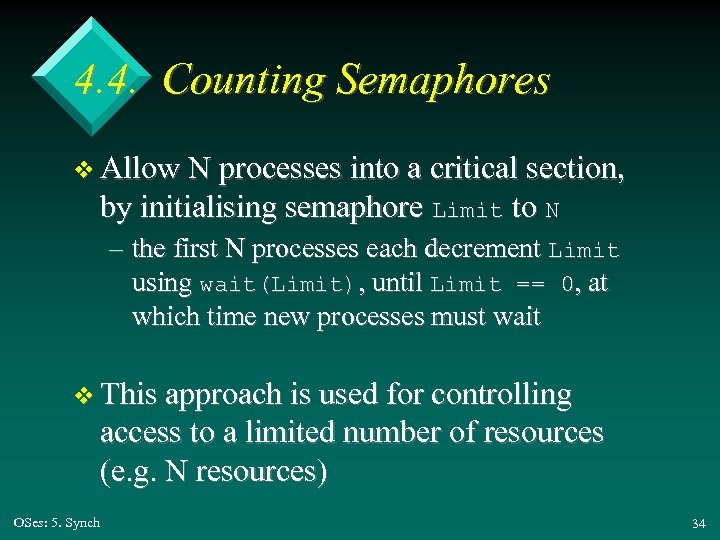

4. 4. Counting Semaphores v Allow N processes into a critical section, by initialising semaphore Limit to N – the first N processes each decrement Limit using wait(Limit), until Limit == 0, at which time new processes must wait v This approach is used for controlling access to a limited number of resources (e. g. N resources) OSes: 5. Synch 34

4. 4. Counting Semaphores v Allow N processes into a critical section, by initialising semaphore Limit to N – the first N processes each decrement Limit using wait(Limit), until Limit == 0, at which time new processes must wait v This approach is used for controlling access to a limited number of resources (e. g. N resources) OSes: 5. Synch 34

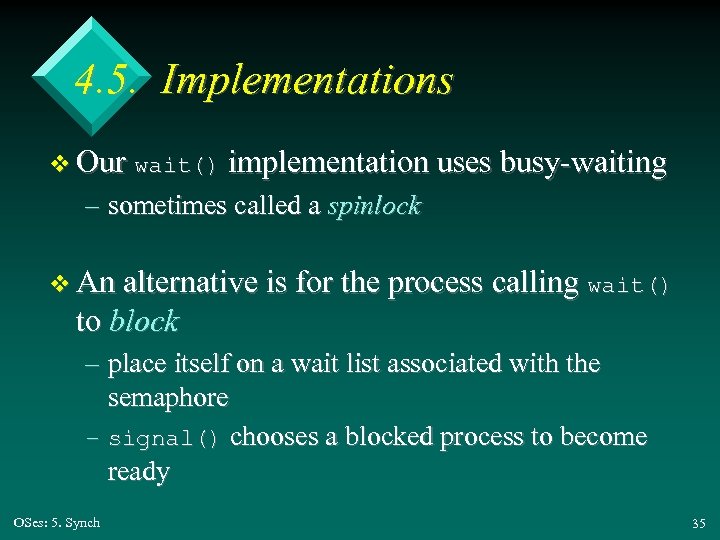

4. 5. Implementations v Our wait() implementation uses busy-waiting – sometimes called a spinlock v An alternative is for the process calling wait() to block – place itself on a wait list associated with the semaphore – signal() chooses a blocked process to become ready OSes: 5. Synch 35

4. 5. Implementations v Our wait() implementation uses busy-waiting – sometimes called a spinlock v An alternative is for the process calling wait() to block – place itself on a wait list associated with the semaphore – signal() chooses a blocked process to become ready OSes: 5. Synch 35

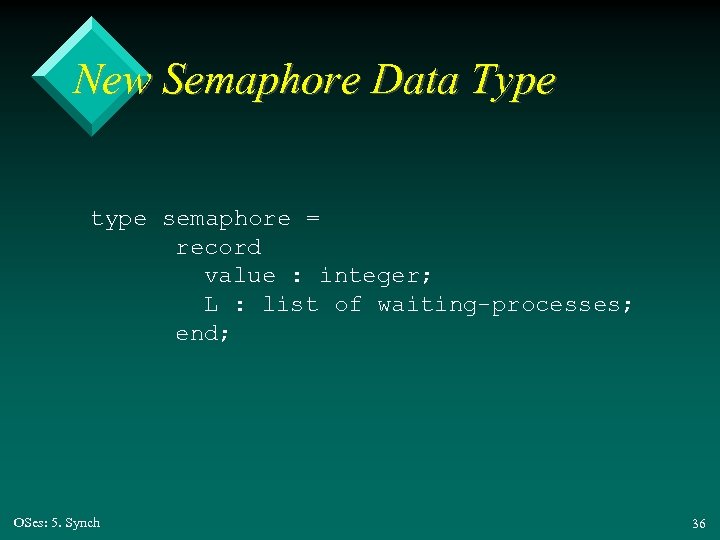

New Semaphore Data Type type semaphore = record value : integer; L : list of waiting-processes; end; OSes: 5. Synch 36

New Semaphore Data Type type semaphore = record value : integer; L : list of waiting-processes; end; OSes: 5. Synch 36

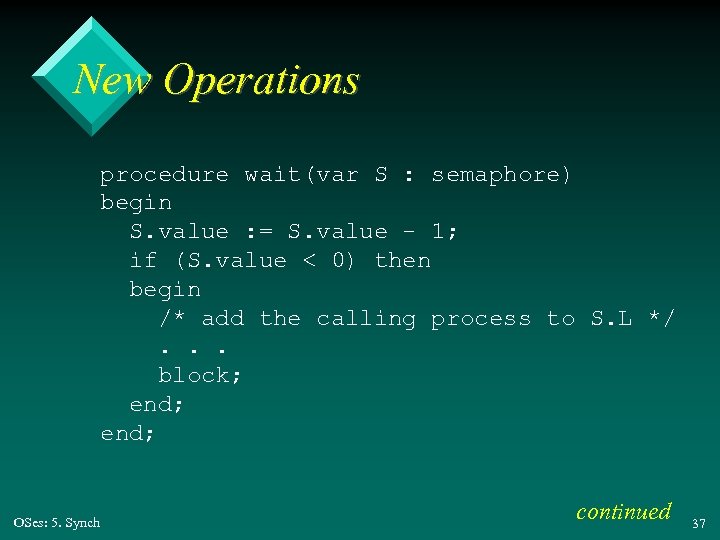

New Operations procedure wait(var S : semaphore) begin S. value : = S. value - 1; if (S. value < 0) then begin /* add the calling process to S. L */. . . block; end; OSes: 5. Synch continued 37

New Operations procedure wait(var S : semaphore) begin S. value : = S. value - 1; if (S. value < 0) then begin /* add the calling process to S. L */. . . block; end; OSes: 5. Synch continued 37

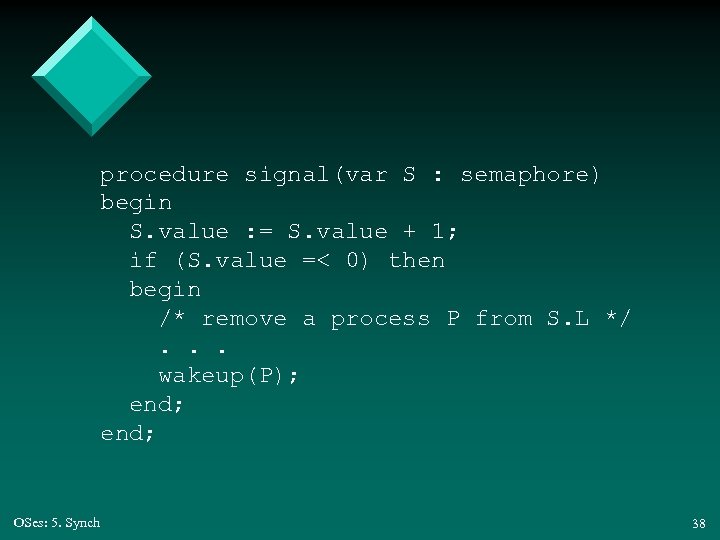

procedure signal(var S : semaphore) begin S. value : = S. value + 1; if (S. value =< 0) then begin /* remove a process P from S. L */. . . wakeup(P); end; OSes: 5. Synch 38

procedure signal(var S : semaphore) begin S. value : = S. value + 1; if (S. value =< 0) then begin /* remove a process P from S. L */. . . wakeup(P); end; OSes: 5. Synch 38

4. 6. Deadlocks & Starvation v Deadlock occurs when every process is waiting for a signal(S) call that can only be carried out by one of the waiting processes. v Starvation occurs when a waiting process never gets selected to move into the critical region. OSes: 5. Synch 39

4. 6. Deadlocks & Starvation v Deadlock occurs when every process is waiting for a signal(S) call that can only be carried out by one of the waiting processes. v Starvation occurs when a waiting process never gets selected to move into the critical region. OSes: 5. Synch 39

4. 7. Binary Semaphores v A binary semaphore is a specialisation of the counting semaphore with S only having a range of 0. . 1 – S starts at 0 – easy to implement – can be used to code up counting semaphores OSes: 5. Synch 40

4. 7. Binary Semaphores v A binary semaphore is a specialisation of the counting semaphore with S only having a range of 0. . 1 – S starts at 0 – easy to implement – can be used to code up counting semaphores OSes: 5. Synch 40

5. Synchronization Examples v 5. 1. v 5. 2. Readers and Writers v 5. 3. OSes: 5. Synch Bounded Buffer Dining Philosophers 41

5. Synchronization Examples v 5. 1. v 5. 2. Readers and Writers v 5. 3. OSes: 5. Synch Bounded Buffer Dining Philosophers 41

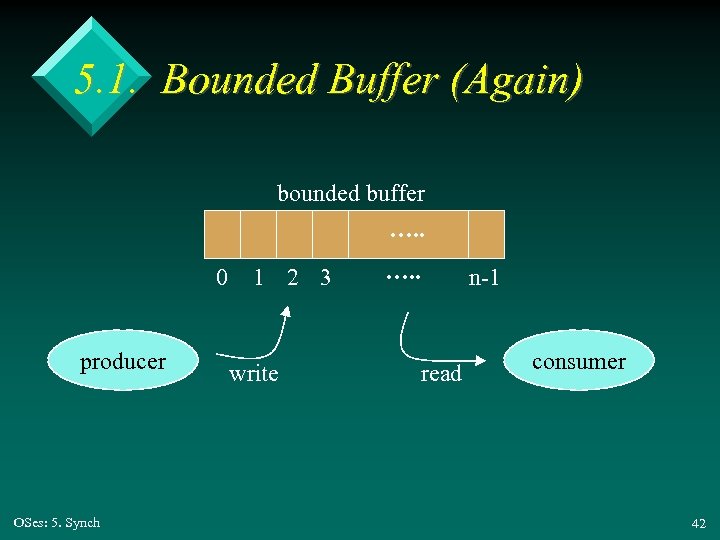

5. 1. Bounded Buffer (Again) bounded buffer …. . 0 producer OSes: 5. Synch 1 2 3 write …. . n-1 read consumer 42

5. 1. Bounded Buffer (Again) bounded buffer …. . 0 producer OSes: 5. Synch 1 2 3 write …. . n-1 read consumer 42

![Implementation v Shared data: var buffer : array[0. . n-1] of Item; var mutex Implementation v Shared data: var buffer : array[0. . n-1] of Item; var mutex](https://present5.com/presentation/89ea8daf8c8a03863a49b9420450c62b/image-43.jpg) Implementation v Shared data: var buffer : array[0. . n-1] of Item; var mutex : semaphore : = 1; /* for access to buffer */ var full : semaphore : = 0; /* num. of used array cells */ var empty : semaphore : = n; /* num. of empty array cells */ OSes: 5. Synch 43

Implementation v Shared data: var buffer : array[0. . n-1] of Item; var mutex : semaphore : = 1; /* for access to buffer */ var full : semaphore : = 0; /* num. of used array cells */ var empty : semaphore : = n; /* num. of empty array cells */ OSes: 5. Synch 43

Producer Code repeat. . . /* produce an item. P */. . . wait(empty); wait(mutex); buffer[in] : = item. P; in : = (in+1) mod n; signal(mutex); signal(full); until false; OSes: 5. Synch 44

Producer Code repeat. . . /* produce an item. P */. . . wait(empty); wait(mutex); buffer[in] : = item. P; in : = (in+1) mod n; signal(mutex); signal(full); until false; OSes: 5. Synch 44

![Consumer Code repeat wait(full); wait(mutex); item. C : = buffer[out]; out : = (out+1) Consumer Code repeat wait(full); wait(mutex); item. C : = buffer[out]; out : = (out+1)](https://present5.com/presentation/89ea8daf8c8a03863a49b9420450c62b/image-45.jpg) Consumer Code repeat wait(full); wait(mutex); item. C : = buffer[out]; out : = (out+1) mod n; signal(mutex); signal(empty); . . . /* use item. C for something */. . . until false; OSes: 5. Synch 45

Consumer Code repeat wait(full); wait(mutex); item. C : = buffer[out]; out : = (out+1) mod n; signal(mutex); signal(empty); . . . /* use item. C for something */. . . until false; OSes: 5. Synch 45

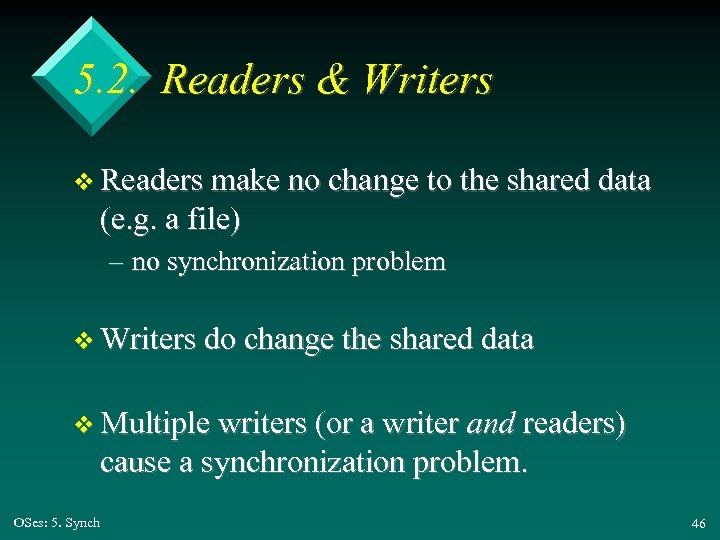

5. 2. Readers & Writers v Readers make no change to the shared data (e. g. a file) – no synchronization problem v Writers do change the shared data v Multiple writers (or a writer and readers) cause a synchronization problem. OSes: 5. Synch 46

5. 2. Readers & Writers v Readers make no change to the shared data (e. g. a file) – no synchronization problem v Writers do change the shared data v Multiple writers (or a writer and readers) cause a synchronization problem. OSes: 5. Synch 46

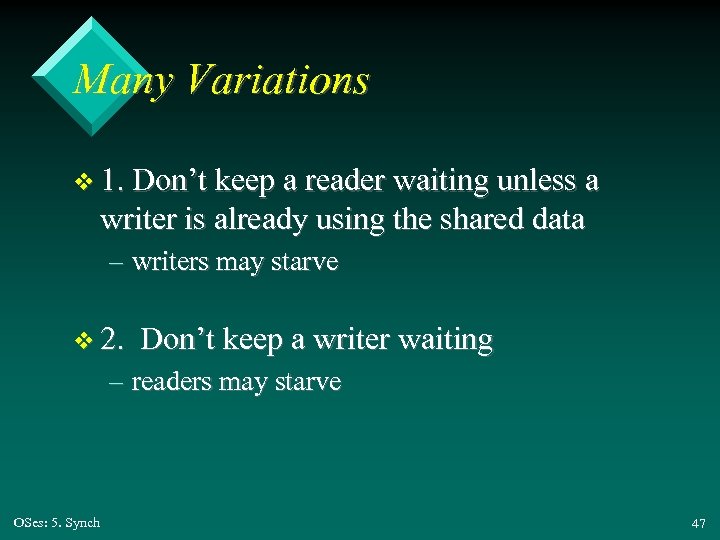

Many Variations v 1. Don’t keep a reader waiting unless a writer is already using the shared data – writers may starve v 2. Don’t keep a writer waiting – readers may starve OSes: 5. Synch 47

Many Variations v 1. Don’t keep a reader waiting unless a writer is already using the shared data – writers may starve v 2. Don’t keep a writer waiting – readers may starve OSes: 5. Synch 47

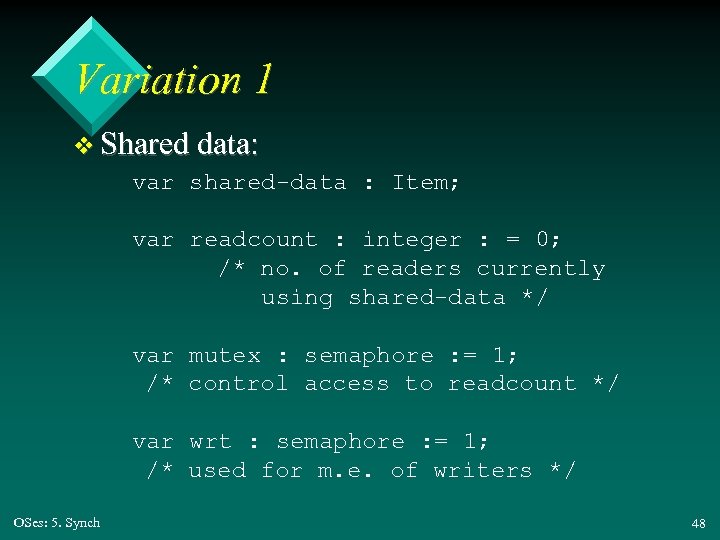

Variation 1 v Shared data: var shared-data : Item; var readcount : integer : = 0; /* no. of readers currently using shared-data */ var mutex : semaphore : = 1; /* control access to readcount */ var wrt : semaphore : = 1; /* used for m. e. of writers */ OSes: 5. Synch 48

Variation 1 v Shared data: var shared-data : Item; var readcount : integer : = 0; /* no. of readers currently using shared-data */ var mutex : semaphore : = 1; /* control access to readcount */ var wrt : semaphore : = 1; /* used for m. e. of writers */ OSes: 5. Synch 48

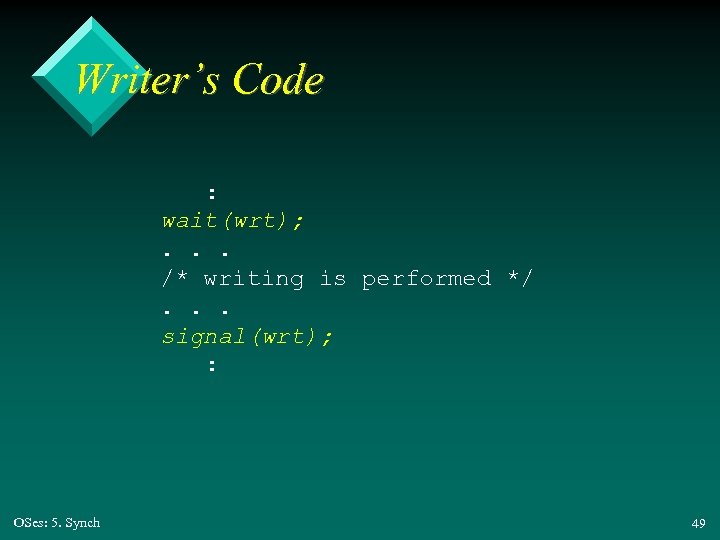

Writer’s Code : wait(wrt); . . . /* writing is performed */. . . signal(wrt); : OSes: 5. Synch 49

Writer’s Code : wait(wrt); . . . /* writing is performed */. . . signal(wrt); : OSes: 5. Synch 49

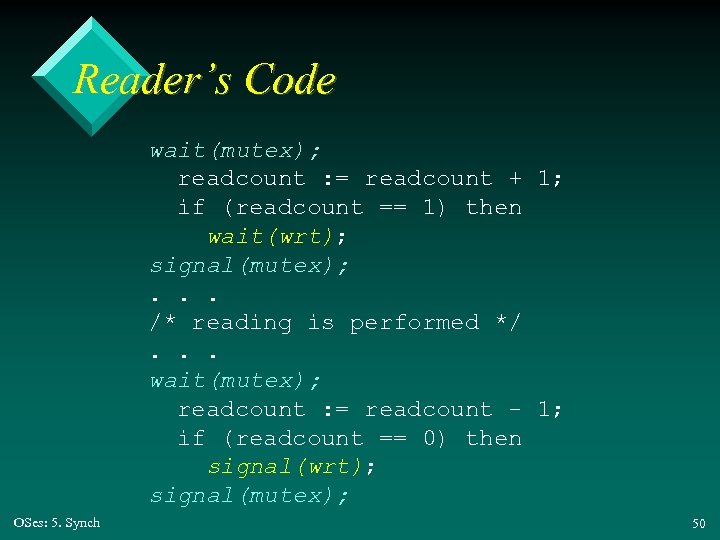

Reader’s Code wait(mutex); readcount : = readcount + 1; if (readcount == 1) then wait(wrt); signal(mutex); . . . /* reading is performed */. . . wait(mutex); readcount : = readcount - 1; if (readcount == 0) then signal(wrt); signal(mutex); OSes: 5. Synch 50

Reader’s Code wait(mutex); readcount : = readcount + 1; if (readcount == 1) then wait(wrt); signal(mutex); . . . /* reading is performed */. . . wait(mutex); readcount : = readcount - 1; if (readcount == 0) then signal(wrt); signal(mutex); OSes: 5. Synch 50

5. 3. Dining Philosophers Dijkstra, 1965 v OSes: 5. Synch An example of the need to allocate several resources (chopsticks) among processes (philosophers) in a deadlock and starvation free manner. 51

5. 3. Dining Philosophers Dijkstra, 1965 v OSes: 5. Synch An example of the need to allocate several resources (chopsticks) among processes (philosophers) in a deadlock and starvation free manner. 51

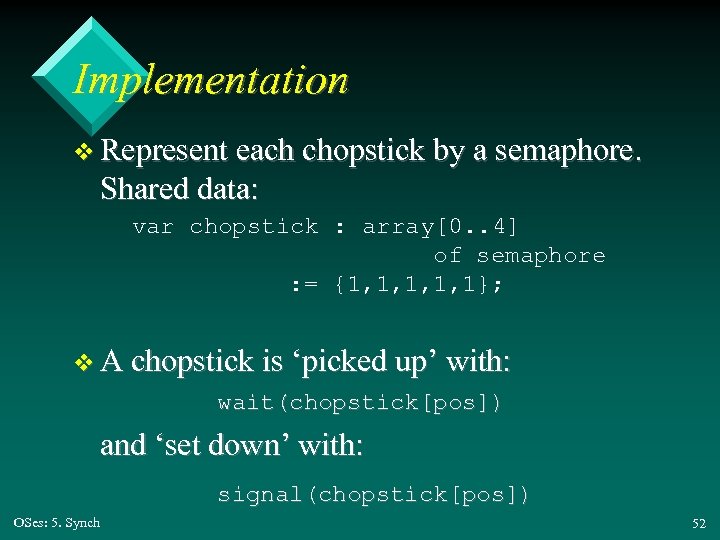

Implementation v Represent each chopstick by a semaphore. Shared data: var chopstick : array[0. . 4] of semaphore : = {1, 1, 1}; v A chopstick is ‘picked up’ with: wait(chopstick[pos]) and ‘set down’ with: signal(chopstick[pos]) OSes: 5. Synch 52

Implementation v Represent each chopstick by a semaphore. Shared data: var chopstick : array[0. . 4] of semaphore : = {1, 1, 1}; v A chopstick is ‘picked up’ with: wait(chopstick[pos]) and ‘set down’ with: signal(chopstick[pos]) OSes: 5. Synch 52

![Code for Philopospher i repeat wait( chopstick[i] ); wait( chopstick[(i+1) mod 5] ); /*. Code for Philopospher i repeat wait( chopstick[i] ); wait( chopstick[(i+1) mod 5] ); /*.](https://present5.com/presentation/89ea8daf8c8a03863a49b9420450c62b/image-53.jpg) Code for Philopospher i repeat wait( chopstick[i] ); wait( chopstick[(i+1) mod 5] ); /*. . . eat. . . */ signal( chopstick[i] ); signal( chopstick[(i+1) mod 5] ); /*. . . think. . . */ until false; OSes: 5. Synch 53

Code for Philopospher i repeat wait( chopstick[i] ); wait( chopstick[(i+1) mod 5] ); /*. . . eat. . . */ signal( chopstick[i] ); signal( chopstick[(i+1) mod 5] ); /*. . . think. . . */ until false; OSes: 5. Synch 53

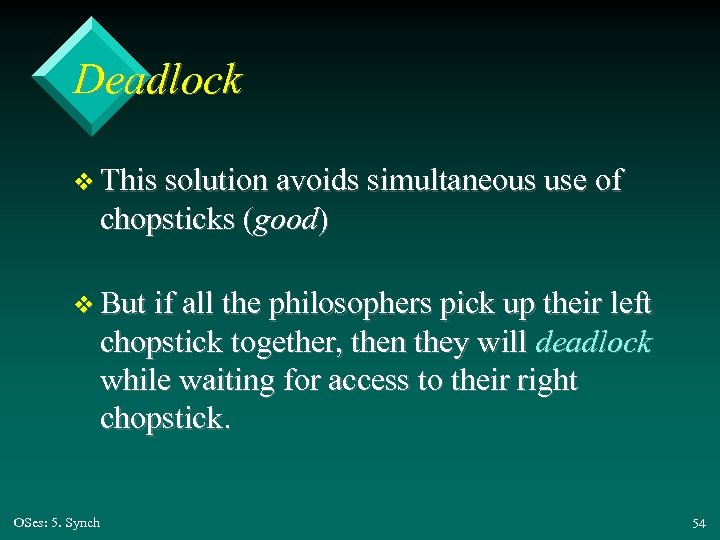

Deadlock v This solution avoids simultaneous use of chopsticks (good) v But if all the philosophers pick up their left chopstick together, then they will deadlock while waiting for access to their right chopstick. OSes: 5. Synch 54

Deadlock v This solution avoids simultaneous use of chopsticks (good) v But if all the philosophers pick up their left chopstick together, then they will deadlock while waiting for access to their right chopstick. OSes: 5. Synch 54

Possible Fixes v Allow at most 4 philosophers to be at the table at a time. v Have a philosopher pick up their chopsticks only if both are available (in a critical section) v Alternate the order that chopsticks are picked up depending on whether the philosopher is seated at an odd or even seat OSes: 5. Synch 55

Possible Fixes v Allow at most 4 philosophers to be at the table at a time. v Have a philosopher pick up their chopsticks only if both are available (in a critical section) v Alternate the order that chopsticks are picked up depending on whether the philosopher is seated at an odd or even seat OSes: 5. Synch 55

6. Problems with Semaphores v The reversal of a wait() and signal() pair will break mutual exclusion v The omission of either a wait() or signal() will potentially cause deadlock v These problems are difficult to debug and reproduce OSes: 5. Synch 56

6. Problems with Semaphores v The reversal of a wait() and signal() pair will break mutual exclusion v The omission of either a wait() or signal() will potentially cause deadlock v These problems are difficult to debug and reproduce OSes: 5. Synch 56

Higher level Synchronization v These problems have motivated the introduction of higher level constructs: – critical regions – monitors – condition variables v These constructs are safer, and easy to understand OSes: 5. Synch 57

Higher level Synchronization v These problems have motivated the introduction of higher level constructs: – critical regions – monitors – condition variables v These constructs are safer, and easy to understand OSes: 5. Synch 57

7. Critical Regions Hoare, 1972; Brinch Hansen, 1972 v Shared variables are explicitly declared: var v : shared Item. Type; v A shared variable can only be accessed within the code part (S) of a region statement: region v do S – while code S is being executed, no other process can access v OSes: 5. Synch 58

7. Critical Regions Hoare, 1972; Brinch Hansen, 1972 v Shared variables are explicitly declared: var v : shared Item. Type; v A shared variable can only be accessed within the code part (S) of a region statement: region v do S – while code S is being executed, no other process can access v OSes: 5. Synch 58

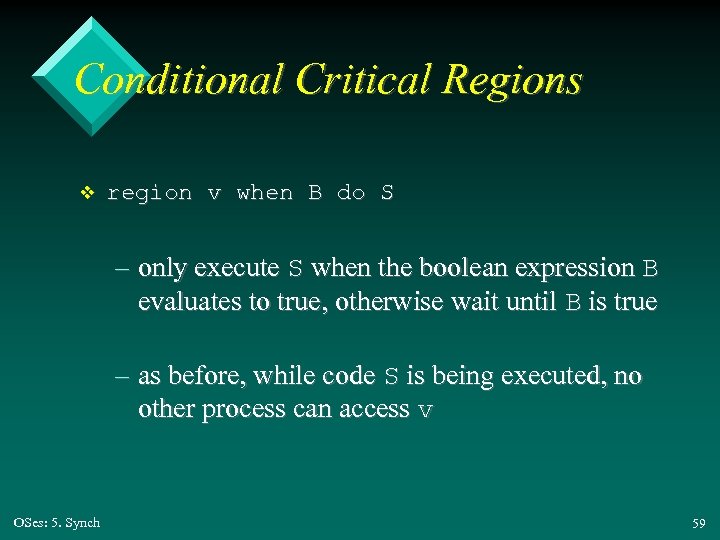

Conditional Critical Regions v region v when B do S – only execute S when the boolean expression B evaluates to true, otherwise wait until B is true – as before, while code S is being executed, no other process can access v OSes: 5. Synch 59

Conditional Critical Regions v region v when B do S – only execute S when the boolean expression B evaluates to true, otherwise wait until B is true – as before, while code S is being executed, no other process can access v OSes: 5. Synch 59

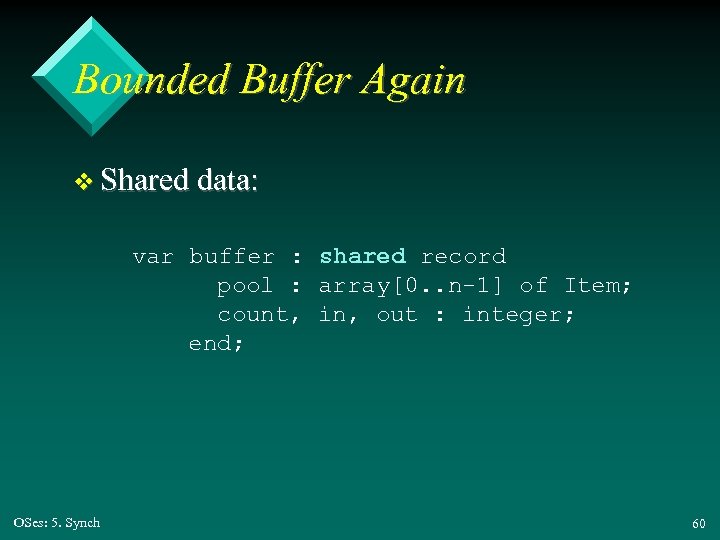

Bounded Buffer Again v Shared data: var buffer : shared record pool : array[0. . n-1] of Item; count, in, out : integer; end; OSes: 5. Synch 60

Bounded Buffer Again v Shared data: var buffer : shared record pool : array[0. . n-1] of Item; count, in, out : integer; end; OSes: 5. Synch 60

![Producer Code region buffer when (count < n) do begin pool[in] : = item. Producer Code region buffer when (count < n) do begin pool[in] : = item.](https://present5.com/presentation/89ea8daf8c8a03863a49b9420450c62b/image-61.jpg) Producer Code region buffer when (count < n) do begin pool[in] : = item. P; in : = (in+1) mod n; count : = count + 1; end; OSes: 5. Synch 61

Producer Code region buffer when (count < n) do begin pool[in] : = item. P; in : = (in+1) mod n; count : = count + 1; end; OSes: 5. Synch 61

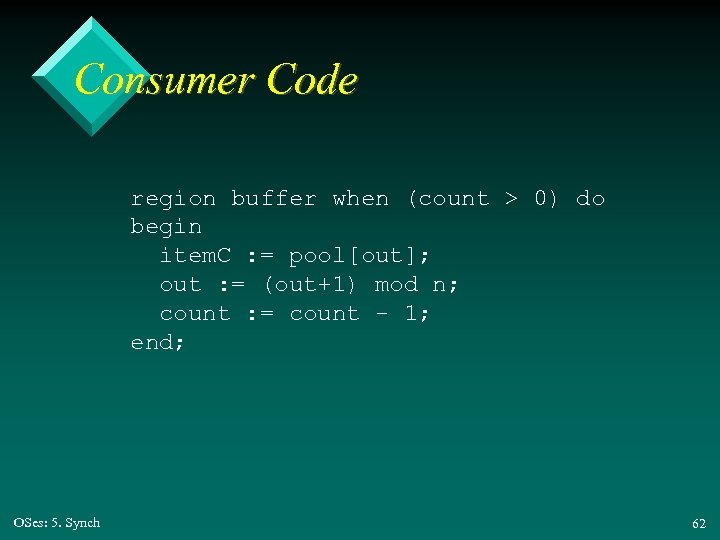

Consumer Code region buffer when (count > 0) do begin item. C : = pool[out]; out : = (out+1) mod n; count : = count - 1; end; OSes: 5. Synch 62

Consumer Code region buffer when (count > 0) do begin item. C : = pool[out]; out : = (out+1) mod n; count : = count - 1; end; OSes: 5. Synch 62

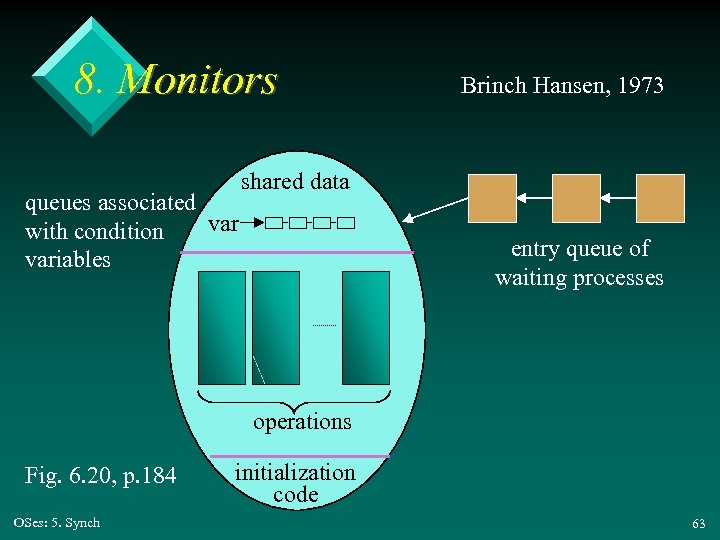

8. Monitors queues associated var with condition variables Brinch Hansen, 1973 shared data entry queue of waiting processes operations Fig. 6. 20, p. 184 OSes: 5. Synch initialization code 63

8. Monitors queues associated var with condition variables Brinch Hansen, 1973 shared data entry queue of waiting processes operations Fig. 6. 20, p. 184 OSes: 5. Synch initialization code 63

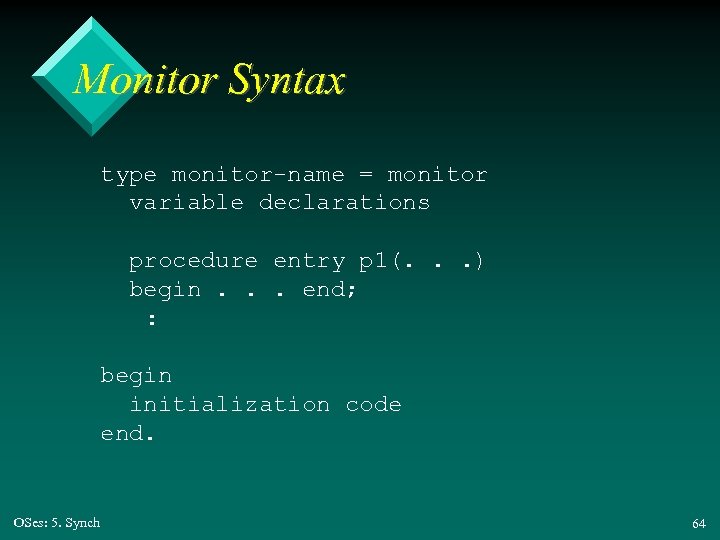

Monitor Syntax type monitor-name = monitor variable declarations procedure entry p 1(. . . ) begin. . . end; : begin initialization code end. OSes: 5. Synch 64

Monitor Syntax type monitor-name = monitor variable declarations procedure entry p 1(. . . ) begin. . . end; : begin initialization code end. OSes: 5. Synch 64

Features v When an instance of a monitor is created, its initialization code is executed v A procedure can access its own variables and those in the monitor’s variable declarations v A monitor only allows one process to use its operations at a time OSes: 5. Synch 65

Features v When an instance of a monitor is created, its initialization code is executed v A procedure can access its own variables and those in the monitor’s variable declarations v A monitor only allows one process to use its operations at a time OSes: 5. Synch 65

An OO View of Monitors v A monitor is similar to a class v An instance of a monitor is similar to an object, with all private data v Plus synchronization: invoking any operation (method) results in mutual exclusion over the entire object OSes: 5. Synch 66

An OO View of Monitors v A monitor is similar to a class v An instance of a monitor is similar to an object, with all private data v Plus synchronization: invoking any operation (method) results in mutual exclusion over the entire object OSes: 5. Synch 66

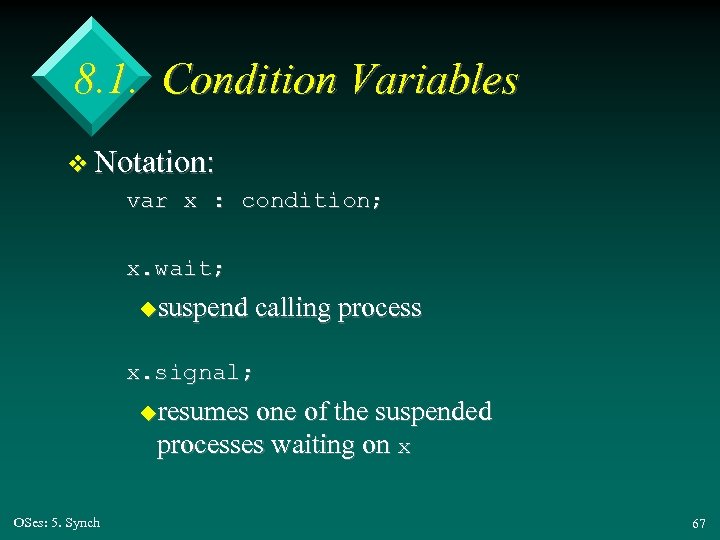

8. 1. Condition Variables v Notation: var x : condition; x. wait; ususpend calling process x. signal; uresumes one of the suspended processes waiting on x OSes: 5. Synch 67

8. 1. Condition Variables v Notation: var x : condition; x. wait; ususpend calling process x. signal; uresumes one of the suspended processes waiting on x OSes: 5. Synch 67

Condition Variables in Monitors v What happens when signal is issued? v The unblocked process will be placed on the ready queue and resume from the statement following the wait. v This would violate mutual exclusion if both the signaller and signalled process are executing in the monitor at once. OSes: 5. Synch 68

Condition Variables in Monitors v What happens when signal is issued? v The unblocked process will be placed on the ready queue and resume from the statement following the wait. v This would violate mutual exclusion if both the signaller and signalled process are executing in the monitor at once. OSes: 5. Synch 68

Three Possible Solutions v 1. Have the signaller leave the monitor immediately after calling signal v 2. Have the signalled process wait until the signaller has left the monitor v 3. Have the signaller wait until the signalled process has left the monitor OSes: 5. Synch 69

Three Possible Solutions v 1. Have the signaller leave the monitor immediately after calling signal v 2. Have the signalled process wait until the signaller has left the monitor v 3. Have the signaller wait until the signalled process has left the monitor OSes: 5. Synch 69

8. 2. Dining Philosophers (Again) v Useful data structures: var state : array[0. . 4] of (thinking, hungry, eating); var self : array[0. . 4] of condition; /* used to delay philosophers */ v The approach is to only set state[i] to eating if its two neigbours are not eating – i. e. and OSes: 5. Synch state[(i+4) mod 5] state[(i+1) mod 5] = = eating 70

8. 2. Dining Philosophers (Again) v Useful data structures: var state : array[0. . 4] of (thinking, hungry, eating); var self : array[0. . 4] of condition; /* used to delay philosophers */ v The approach is to only set state[i] to eating if its two neigbours are not eating – i. e. and OSes: 5. Synch state[(i+4) mod 5] state[(i+1) mod 5] = = eating 70

Using the dining-philosophers Monitor v Shared data: var dp : dining-philosopher; v Code in philosopher i: dp. pickup(i): /*. . . eat. . . */ dp. putdown(i); OSes: 5. Synch 71

Using the dining-philosophers Monitor v Shared data: var dp : dining-philosopher; v Code in philosopher i: dp. pickup(i): /*. . . eat. . . */ dp. putdown(i); OSes: 5. Synch 71

![Monitor implementation type dining-philosophers = monitor var state : array[0. . 4] of (thinking, Monitor implementation type dining-philosophers = monitor var state : array[0. . 4] of (thinking,](https://present5.com/presentation/89ea8daf8c8a03863a49b9420450c62b/image-72.jpg) Monitor implementation type dining-philosophers = monitor var state : array[0. . 4] of (thinking, hungry, eating); var self : array[0. . 4] of condition; procedure entry pickup(i : 0. . 4) begin state[i] : = hungry; test(i); if (state[i] /== eating) then self[i]. wait; end; OSes: 5. Synch continued 72

Monitor implementation type dining-philosophers = monitor var state : array[0. . 4] of (thinking, hungry, eating); var self : array[0. . 4] of condition; procedure entry pickup(i : 0. . 4) begin state[i] : = hungry; test(i); if (state[i] /== eating) then self[i]. wait; end; OSes: 5. Synch continued 72

![procedure entry putdown(i : 0. . 4) begin state[i] : = thinking; test((i+4) mod procedure entry putdown(i : 0. . 4) begin state[i] : = thinking; test((i+4) mod](https://present5.com/presentation/89ea8daf8c8a03863a49b9420450c62b/image-73.jpg) procedure entry putdown(i : 0. . 4) begin state[i] : = thinking; test((i+4) mod 5); test((i+1) mod 5); end; OSes: 5. Synch continued 73

procedure entry putdown(i : 0. . 4) begin state[i] : = thinking; test((i+4) mod 5); test((i+1) mod 5); end; OSes: 5. Synch continued 73

![procedure test(k : 0. . 4) begin if ((state[(k+4) mod 5] /== eating) and procedure test(k : 0. . 4) begin if ((state[(k+4) mod 5] /== eating) and](https://present5.com/presentation/89ea8daf8c8a03863a49b9420450c62b/image-74.jpg) procedure test(k : 0. . 4) begin if ((state[(k+4) mod 5] /== eating) and (state[k] == hungry) and (state[(k+1) mod 5] /== eating)) then begin state[k] : = eating; self[k]. signal; end; OSes: 5. Synch continued 74

procedure test(k : 0. . 4) begin if ((state[(k+4) mod 5] /== eating) and (state[k] == hungry) and (state[(k+1) mod 5] /== eating)) then begin state[k] : = eating; self[k]. signal; end; OSes: 5. Synch continued 74

begin /* initialization of monitor instance */ for i : = 0 to 4 do state[i] : = thinking; end. OSes: 5. Synch 75

begin /* initialization of monitor instance */ for i : = 0 to 4 do state[i] : = thinking; end. OSes: 5. Synch 75

8. 3. Problems with Monitors v Even high level operations can be misused. v For correctness, we must check: – that all user processes always call the monitor operations in the right order; – that no user process bypasses the monitor and uses a shared resource directly – called the access-control problem OSes: 5. Synch 76

8. 3. Problems with Monitors v Even high level operations can be misused. v For correctness, we must check: – that all user processes always call the monitor operations in the right order; – that no user process bypasses the monitor and uses a shared resource directly – called the access-control problem OSes: 5. Synch 76

9. Synchronization in Solaris 2 v Uses a mix of techniques: – semaphores using spinlocks – thread blocking – condition variables (without monitors) – specialised reader-writer locks on data OSes: 5. Synch 77

9. Synchronization in Solaris 2 v Uses a mix of techniques: – semaphores using spinlocks – thread blocking – condition variables (without monitors) – specialised reader-writer locks on data OSes: 5. Synch 77

10. Atomic Transactions v We want to do all the operations of a critical section as a single logical ‘unit’ of work – it is either done completely or not at all v A transaction can be viewed as a sequence of reads and writes on shared data, ending with a commit or abort operation v An abort causes a partial transaction to be OSes: 5. Synch rolled back 78

10. Atomic Transactions v We want to do all the operations of a critical section as a single logical ‘unit’ of work – it is either done completely or not at all v A transaction can be viewed as a sequence of reads and writes on shared data, ending with a commit or abort operation v An abort causes a partial transaction to be OSes: 5. Synch rolled back 78

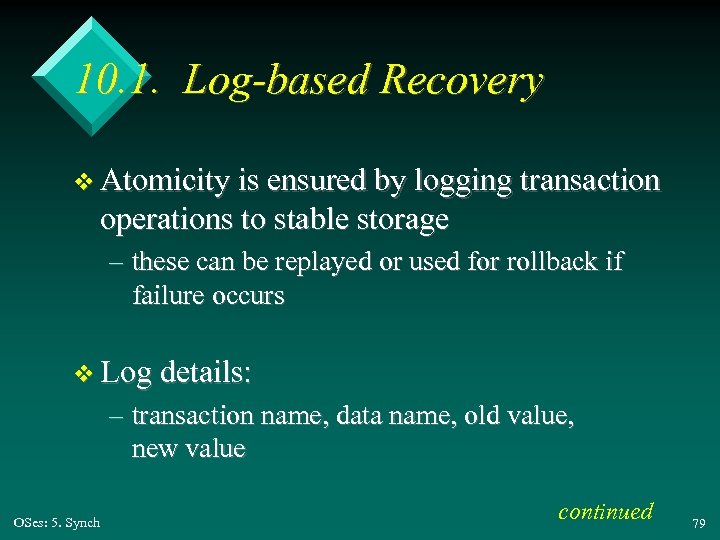

10. 1. Log-based Recovery v Atomicity is ensured by logging transaction operations to stable storage – these can be replayed or used for rollback if failure occurs v Log details: – transaction name, data name, old value, new value OSes: 5. Synch continued 79

10. 1. Log-based Recovery v Atomicity is ensured by logging transaction operations to stable storage – these can be replayed or used for rollback if failure occurs v Log details: – transaction name, data name, old value, new value OSes: 5. Synch continued 79

v Write-ahead logging: – log a write operation before doing it – log the transaction start and its commit OSes: 5. Synch 80

v Write-ahead logging: – log a write operation before doing it – log the transaction start and its commit OSes: 5. Synch 80

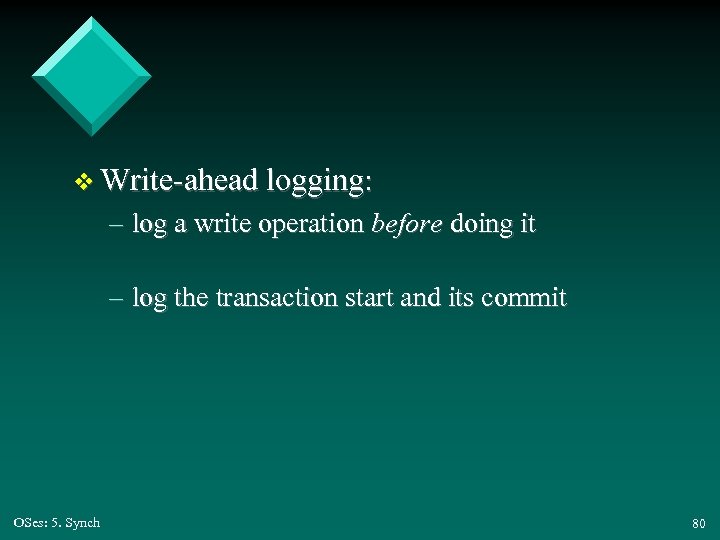

Example begin transaction read X if (X >= a) then { read Y X = X - a Y = Y + a write X write Y } end transaction OSes: 5. Synch (VUW CS 305)

Example begin transaction read X if (X >= a) then { read Y X = X - a Y = Y + a write X write Y } end transaction OSes: 5. Synch (VUW CS 305)

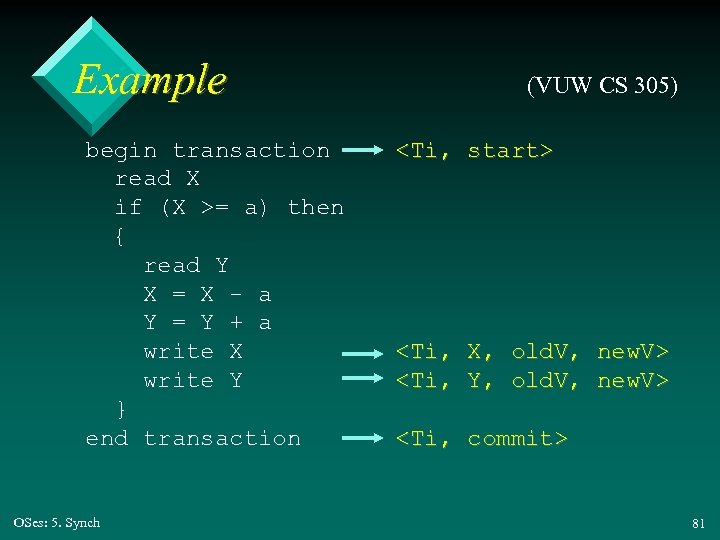

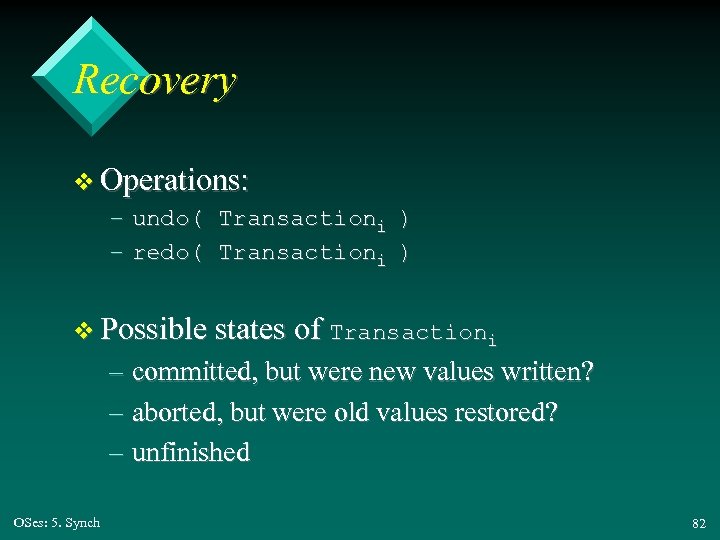

Recovery v Operations: – undo( Transactioni ) – redo( Transactioni ) v Possible states of Transactioni – committed, but were new values written? – aborted, but were old values restored? – unfinished OSes: 5. Synch 82

Recovery v Operations: – undo( Transactioni ) – redo( Transactioni ) v Possible states of Transactioni – committed, but were new values written? – aborted, but were old values restored? – unfinished OSes: 5. Synch 82

10. 2. Checkpoints v A checkpoint fixes state changes by writing them to stable storage so that the log file can be reset or shortened. OSes: 5. Synch 83

10. 2. Checkpoints v A checkpoint fixes state changes by writing them to stable storage so that the log file can be reset or shortened. OSes: 5. Synch 83

10. 3. Concurrent Atomic Transactions v We want to ensure that the outcome of concurrent transactions are the same as if they were executed in some serial order – serializability OSes: 5. Synch 84

10. 3. Concurrent Atomic Transactions v We want to ensure that the outcome of concurrent transactions are the same as if they were executed in some serial order – serializability OSes: 5. Synch 84

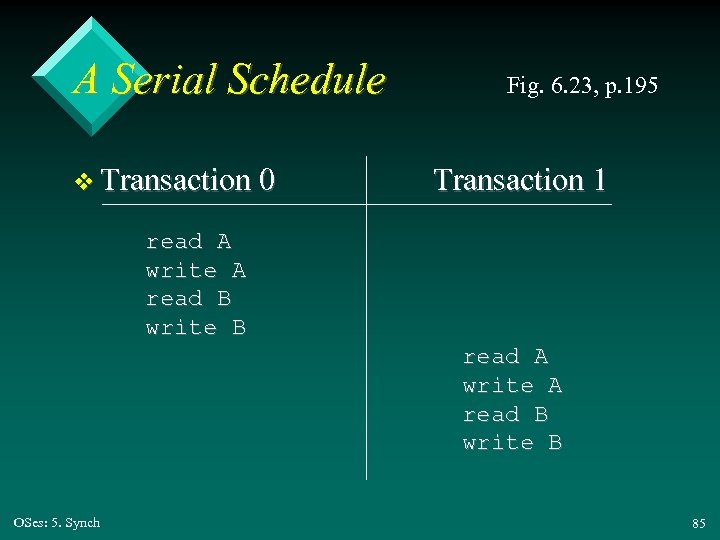

A Serial Schedule v Transaction 0 Fig. 6. 23, p. 195 Transaction 1 read A write A read B write B OSes: 5. Synch 85

A Serial Schedule v Transaction 0 Fig. 6. 23, p. 195 Transaction 1 read A write A read B write B OSes: 5. Synch 85

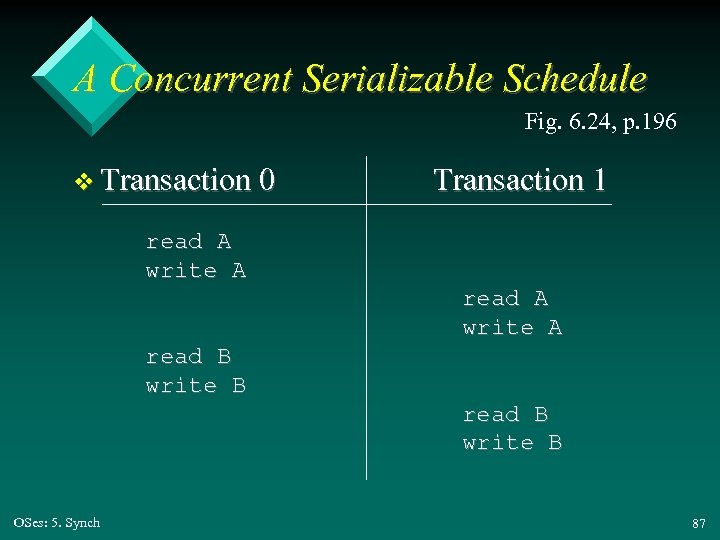

Conflicting Operations v Two operations in different transactions conflict if they access the same data and one of them is a write. v Serializability must avoid conflicting operations: – it can do that by delaying/speeding up when operations in a transaction are performed OSes: 5. Synch 86

Conflicting Operations v Two operations in different transactions conflict if they access the same data and one of them is a write. v Serializability must avoid conflicting operations: – it can do that by delaying/speeding up when operations in a transaction are performed OSes: 5. Synch 86

A Concurrent Serializable Schedule Fig. 6. 24, p. 196 v Transaction 0 Transaction 1 read A write A read B write B OSes: 5. Synch 87

A Concurrent Serializable Schedule Fig. 6. 24, p. 196 v Transaction 0 Transaction 1 read A write A read B write B OSes: 5. Synch 87

10. 4. Locks v Serializability can be achieved by locking data items v There a range of locking modes: – a shared lock allows multiple reads by different transactions – an exclusive lock allows only one transaction to do reads/writes OSes: 5. Synch 88

10. 4. Locks v Serializability can be achieved by locking data items v There a range of locking modes: – a shared lock allows multiple reads by different transactions – an exclusive lock allows only one transaction to do reads/writes OSes: 5. Synch 88

10. 5. Timestamping v One way of ordering transactions v Using the system clock is not sufficient when transactions may originate on different machines OSes: 5. Synch 89

10. 5. Timestamping v One way of ordering transactions v Using the system clock is not sufficient when transactions may originate on different machines OSes: 5. Synch 89