81dff0bdb33a63e2b109a4b002616250.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 54

Opening—and Sustaining—Dialogue: From Practice to Theory and Back Martin Nystrand The University of Wisconsin-Madison USA The International Association for the Improvement of Mother Tongue Education (IAIMTE) * Exeter, UK * March 27, 2007

Climate for Education Research in USA “The extent of our ignorance is masked by a “folk wisdom” of education based on the experience of human beings over the millennia in passing information and skills from one generation to the next. . It doesn't demand scientific knowledge of mechanisms of learning or organizational principles or social processes. It is … hit or miss. It lets us muddle through when the tasks to be learned are simple, or in a highly elitist system in which we only expect those with the most talent and most cultural support to learn advanced skills. But it fails when the tasks to be learned are complex or when we expect that no child will be left behind. ” Grover Whitehurst, 2002

Part 1 Classroom Discourse and Student Learning n n n n Opening Dialogue: Understanding the Dynamics of Language and Learning in the English Classroom. (Teachers College Press, 1997) 2 -year study with University of Wisconsin-Madison Sociologist Adam Gamoran 16 middle schools and 9 high schools in 8 Midwestern urban, suburban, and rural communities 58 8 th-grade and 54 9 th-grade English language arts classes 1, 100+ students each year 4 observations of each class Students assessed fall and spring on writing, reading, and literature Quantitative analysis of effects of classroom discourse controlled for initial writing and reading performance, plus demographic variables (gender, race, ethnicity, SES) and tracking (streaming) variables

Conceptual Framework n n Dialogic sources, especially the Bakhtin Circle, including Bakhtin & Volo inov Understandings worked out in the refraction of voices: A given utterance cannot be understood “outside the organized interrelationships of the [conversants]. . The crux of the matter is not in the subjective consciousness of the speakers. . . or what [the speakers] think, experience, or want, but in what the objective social logic of their interrelationships demands of them. . In the final account, this logic defines the very experiences of people (their ‘inner speech’). ” Medvedev & Bakhtin, The Formal Method, p. 153

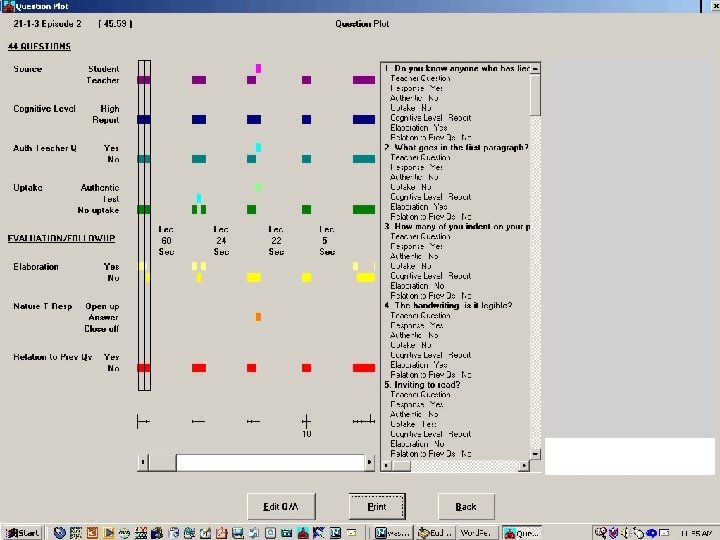

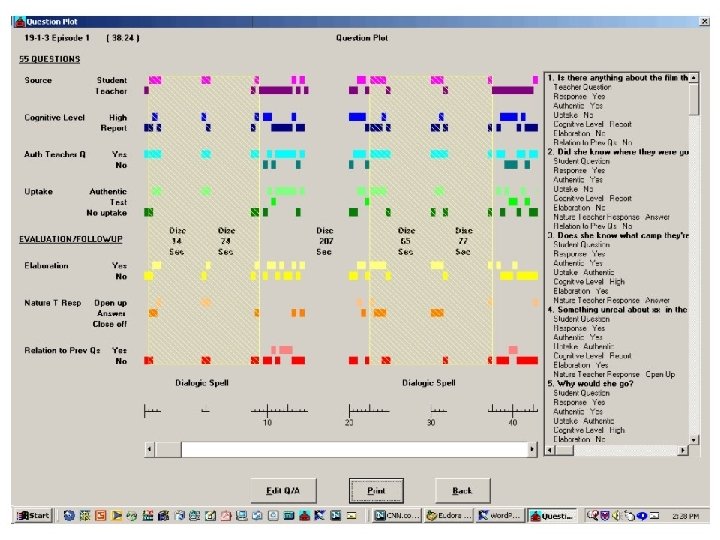

CLASS 4. 24 A Windows Laptop-Computer System for the In-Class Analysis of Classroom Discourse n n n Time and track activities Code question events Accommodate fieldnotes Program and User’s Manual: http: //www. wisc. edu/english/nystrand/class. html n

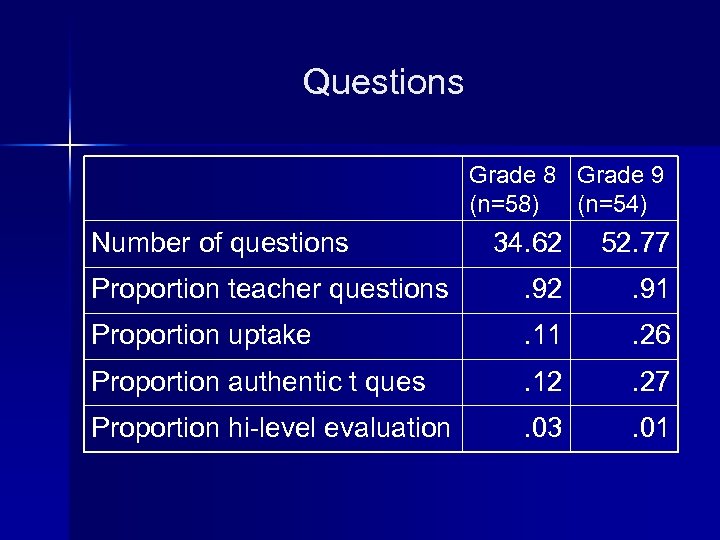

Question Events Questions coded according to what they elicit: n Authenticity: Known answer or open ended? n Uptake: Follow up on someone else’s response n Level of evaluation or followup: Level of seriousness teacher gives to student responses “Proximal index” of organization of classroom

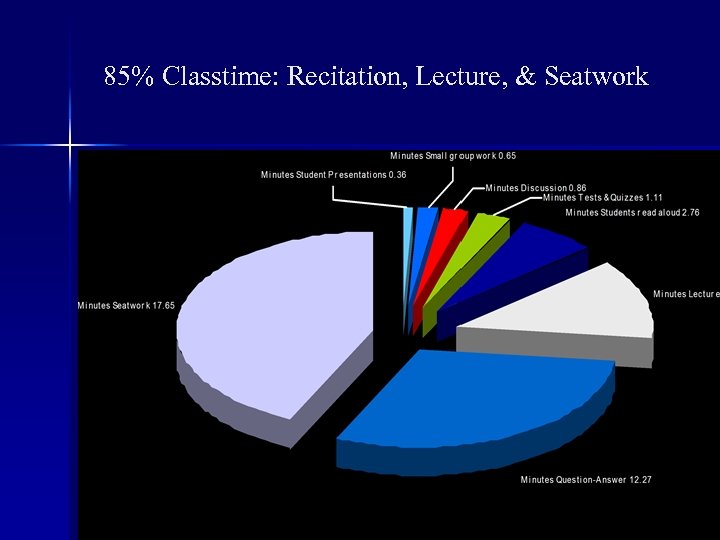

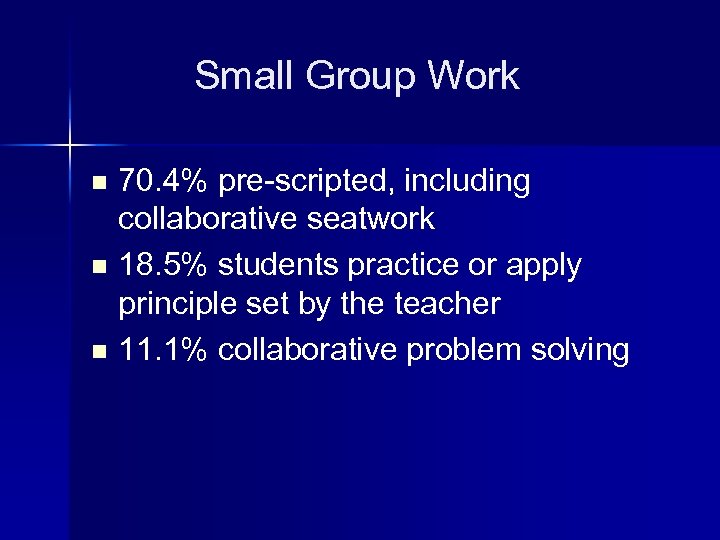

Classtime n n When teachers were not lecturing, students were mainly either answering questions or completing seatwork. The teacher asked nearly all the questions, few were authentic, and equally few followed up student responses. On average, discussion lasted less than 50 seconds per class in Grade 8 and less than 15 seconds in Grade 9. Small-group work in Grade 8 averaged only 39 seconds each day, only a little more than 2 minutes in Grade 9.

85% Classtime: Recitation, Lecture, & Seatwork

Small Group Work 70. 4% pre-scripted, including collaborative seatwork n 18. 5% students practice or apply principle set by the teacher n 11. 1% collaborative problem solving n

Questions Grade 8 Grade 9 (n=58) (n=54) Number of questions 34. 62 52. 77 Proportion teacher questions . 92 . 91 Proportion uptake . 11 . 26 Proportion authentic t ques . 12 . 27 Proportion hi-level evaluation . 03 . 01

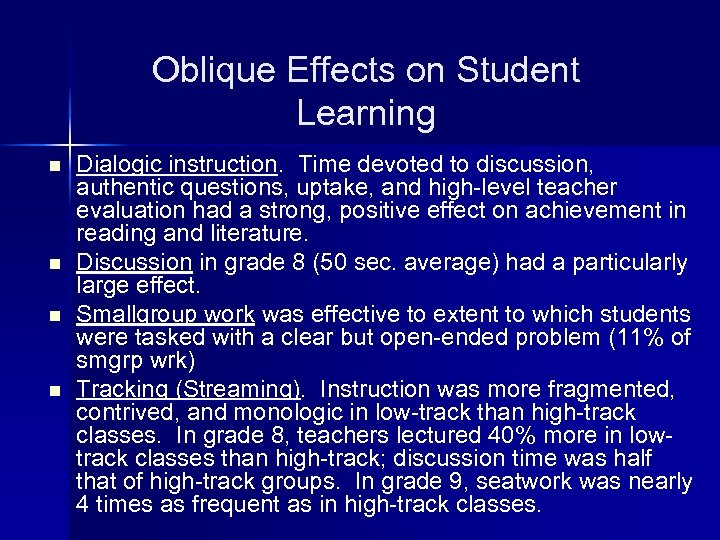

Oblique Effects on Student Learning n n Dialogic instruction. Time devoted to discussion, authentic questions, uptake, and high-level teacher evaluation had a strong, positive effect on achievement in reading and literature. Discussion in grade 8 (50 sec. average) had a particularly large effect. Smallgroup work was effective to extent to which students were tasked with a clear but open-ended problem (11% of smgrp wrk) Tracking (Streaming). Instruction was more fragmented, contrived, and monologic in low-track than high-track classes. In grade 8, teachers lectured 40% more in lowtrack classes than high-track; discussion time was half that of high-track groups. In grade 9, seatwork was nearly 4 times as frequent as in high-track classes.

Previous Studies n n n M. Nystrand. Dialogic Discourse Analysis of Revision in Response Groups. In G. Stygal & E. Barton, Discourse Studies in Composition (Hampton Press, 2002). Nystrand, M. , & Brandt, D. Response to writing as a context for learning to write. In C. Anson (Ed. ), Writing and Response: Models, methods, and curricular change. (NCTE, 1989). M. Nystrand. The Structure of Written Communication. Learning to Write by Talking about Writing (ch. 8) (Academic Press, 1986).

Effects of Response Groups on Writing Development 3 -year study: 250 college freshmen in 13 classes n 6 writing “studios”: Students share writing with peers n 7 non-studios: Students write for teacher only n

Writing Studios Students meet in groups of 4 -5 to share and critique writing, 90% of class meetings n Groups stable for semester n New draft or revision each meeting; photocopies for group mates n Cold readings: Read as reader (themselves), not the Reader n No checklists; copy editing prohibited n

Assessments Quality of exposition at start and end of semester n Development of students’ understanding of their writing processes during semester n

Writing Exposition: Sustained reflection. Scored for: n Level of abstraction (Britton et al. , 1975) n Coherence and elaboration of argumentation (Applebee, Langer, & Mullis, 1985) n Two independent readings n Interrater reliability: . 68.

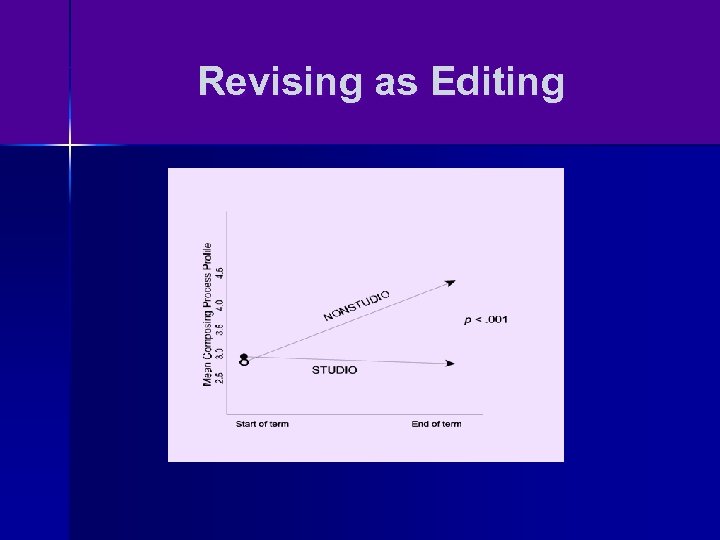

Composing Process Profile “How I generally write a paper” (20 -minutes): n. Process: Stylized vs. detailed n. Process: Linear vs. improvised n. Revising: Edit vs. reconceptualize n. Reader: Examiner vs. collaborator n. Metacognition: Level of insight n. Attitudes towards writing: Positive vs. negative n 2 independent readings: . 829 interrater reliability

Results Significant gains in writing quality for studio vs. non-studio students (p=. 0023) n Gains associated with conceptions of revision and role of readers n

Revising as Editing

Revision as Reconceptualization

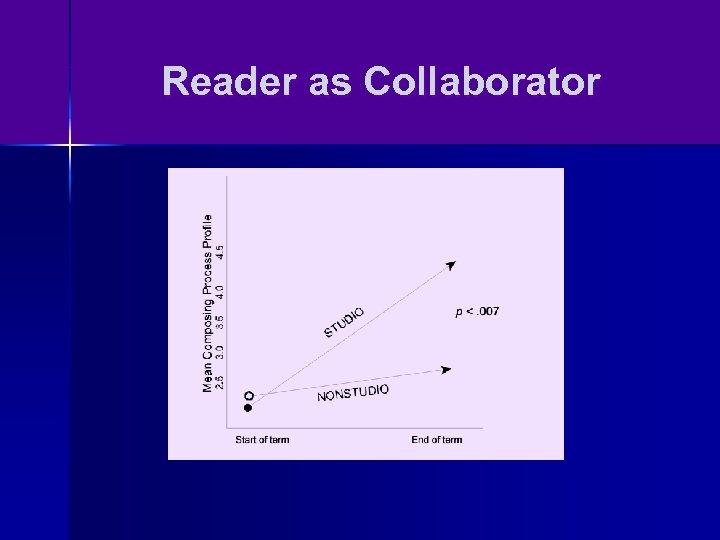

Reader as Collaborator

Positive Attitudes Towards Writing

Effects of Response Groups Writing development shaped by how the writers came to view their readers n Written communication = event n Text mediates writer-reader interaction n Oblique effects n

Follow Up Studies National Research Center on English Learning & Achievement http: //cela. albany. edu CELA National Study of English Achievement in Middle School Classrooms (1996 -2001) n CELA Literacy Partnership Study (2000 -2002) n Sean Kelly. Study of Race, Social Class, Student Engagement (2005) n

A. Applebee, J. Langer, M. Nystrand, & A. Gamoran Discussion-Based Approaches to Developing Understanding: Classroom Instruction and Student Performance in Middle and High School English (AERJ, 2003, pp. 685 -730) n n 974 students in 64 classes in 19 schools in New York, Florida, California, Wisconsin, & Texas Replication of Opening Dialogue study supporting discussion-based instruction in the context of high academic demands

J. Langer. Beating the Odds: Teaching Middle and High School Students to Read and Write Well. (AERJ, 2001, pp. 837 -880). n n n CELA National Study of English Achievement in Middle School Classrooms 960 students & 44 teachers in 25 schools, 88 classes in New York, Florida, Calif. , & Texas “Higher performing teachers treat students as members of dynamic learning communities that rely on social and cognitive interactions to support learning”

S. Kelly. Race, Social Class, Student Engagement, and the Development of Unequal Literacy Skills During the Middle School Years. Ph. D Sociology dissertation, Univ Wisconsin-Madison, 2005 n n High SES male students answer more questions than other groups Boys and girls participate equally in discussion Participation unrelated to gains in achievement Achievement gains a function of overall dialogic discourse environment vs. individual participation

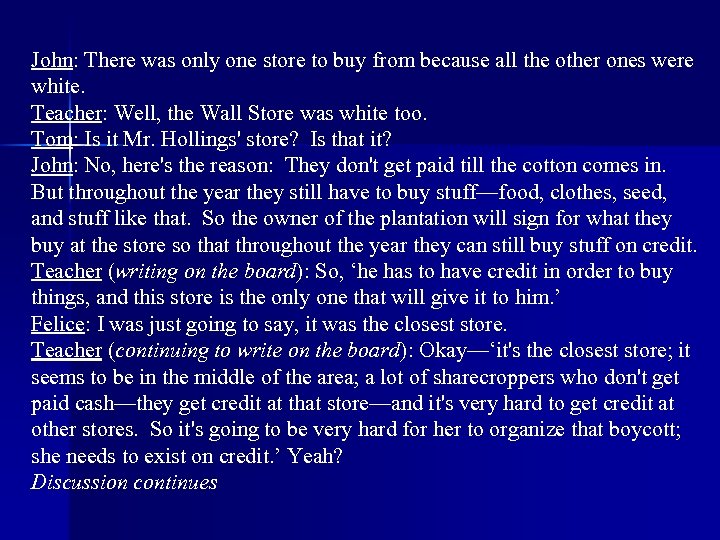

For Example: Teacher: I had a lot of trouble getting everything down [on the board], and I think I missed the part about trying to boycott. ” Reading from the board: ‘and tries to organize a boycott. ’ To class: Did I get everything down, John, that you said? John: What about the guy who didn't really think these kids were a pest? Teacher: Yeah, okay. What's his name? Do you remember? ” (John shakes his head, indicating he can’t remember) Alicia: Wasn't it Turner? Teacher: Was it Turner? Several students: Yes. Teacher (writing on the board): Okay, so ‘Mr. Turner resisted white help. ’ Why? Why would he want to keep shopping at that terrible store?

John: There was only one store to buy from because all the other ones were white. Teacher: Well, the Wall Store was white too. Tom: Is it Mr. Hollings' store? Is that it? John: No, here's the reason: They don't get paid till the cotton comes in. But throughout the year they still have to buy stuff—food, clothes, seed, and stuff like that. So the owner of the plantation will sign for what they buy at the store so that throughout the year they can still buy stuff on credit. Teacher (writing on the board): So, ‘he has to have credit in order to buy things, and this store is the only one that will give it to him. ’ Felice: I was just going to say, it was the closest store. Teacher (continuing to write on the board): Okay—‘it's the closest store; it seems to be in the middle of the area; a lot of sharecroppers who don't get paid cash—they get credit at that store—and it's very hard to get credit at other stores. So it's going to be very hard for her to organize that boycott; she needs to exist on credit. ’ Yeah? Discussion continues

Figuring Things Out: In Class, Face-to Face, Teacher & Students Together Co-construction ANALYSIS T: Okay, so Mr. Turner resisted white help. Why? S 1: Here's the reason. They don't get Why would he want to keep paid till the cotton comes in. But T: ‘ … and tries to shopping at that terrible throughout the year they still have to organize a store? buy stuff—food, clothes, seed, and boycott’ S 2: Wasn't stuff like that. So the owner of the S 1: There was only Did I get it Turner? plantation will sign for what they buy one store to buy T: Yeah, okay. everything down, at the store so that throughout the year from because all the What's his John, that you they can still buy stuff on credit. Ss: Yes other ones were name? Do you said? white. remember? Teacher. T: Well, the student roles Wall Store was white reversed too. REPORT S 1: What about the guy who didn't really think these kids were a pest?

Dialogic Instruction n n Classroom discourse environment plays an essential role in student learning (more important than overt student participation) Reciprocity of roles (teacher-student) Teacher role default Dialogic bids: Teacher “moves” (questions, responses) work as epistemological moves Effects oblique

Bakhtin’s Admonition In an environment of. . . monologism the genuine interaction of consciousness is impossible, and thus genuine dialogue is impossible as well. In essence idealism knows only a single mode of cognitive interaction among consciousnesses: Someone who knows and possesses the truth instructs someone who is ignorant of it and in error; that is, it is the interaction of a teacher and a pupil, which, it follows, can only be a pedagogical dialogue. - Bakhtin, Problems of Doestoevsky’s Poetics, p. 81

Part 2. The Structure of Classroom Discourse Nystrand, Wu, Gamoran, Zeiser, & Long. Questions in Time: Investigating the Structure and Dynamics of Unfolding Classroom Discourse Processes, 2003, pp. 135 -196 Research questions: n How does classroom discourse unfold differently in different types of classrooms? n What types of classrooms play host to discourse that promotes student learning? n How does classroom discourse unfold over time in directions of higher or lower quality? n

s

Dialogic Spell n n n Stretch of whole classroom discourse starting with a student question Followed subsequently, though not necessarily immediately, by at least two more student questions Terminated by a series of three or more strictly monologic test questions

Dialogic Spell Question Plot for Highly Interactive Lesson on The Odyssey Monologic Spell Dialogic Spell Monologic Spell (dialogic dens. =. 32)(density=7. 30) (density=. 62) D I A L O G I C V A L U E F F f E E E F FF f E E D E EE E E D c b a b b a aa a a a a 000000 0000000 0 0 00000 1. . +. . . 10. . +. . . 20. . +. . . 30. . +. . . 40. . +. . . 50. . +. . . 60. . +. . . 70. . +

Monologic Spell Question Plot for Recitation about Magna Carta D. I. A. L. O 10 G. I. C. . V 5 A. L. U. E. f E ◄ 1 student question (in upper case) e Dialogic density (mean dialogic value of questions) = 0. 83 0000000 0000 000000 ◄ teacher test questions 1. . . +. . 10. . +. . 20. . +. . 30. . +. Question Number

Research Methods n Survey studies n n n Power to uncover patterns in categories of activities No access to fine-grained, dynamic data Case studies n n Sensitivity to nuance and dynamics of activities No access to patterns across classes

Event-History Analysis Quantitative methodology used to investigate and predict shifts in events or the status of individuals: n Marriage and divorce n Job mobility n Childbirth & infant mortality n Arrests, convictions, jail sentences, and recidivism n Elections & changes in government n Economic crises n Revolutions and wars

Scope of Study Number of: Gr 8 English Language Arts classes 58 Social Studies classes 57 Times each class observed 4 Observations 460 Number of coded question events Gr 9 54 49 4 412 Totals 112 106 872 35, 887

Discussion and Dialogic Spells Descriptive statistics Subject Σ episodes with no dialogic spells Σ episodes with no discussion % episodes % lessons with no dialogic discussion spells Social Studies 569 520 514 91. 39% 90. 33% English 582 554 531 95. 19% 91. 24% 1, 151 1, 074 93. 31% 90. 75% Total

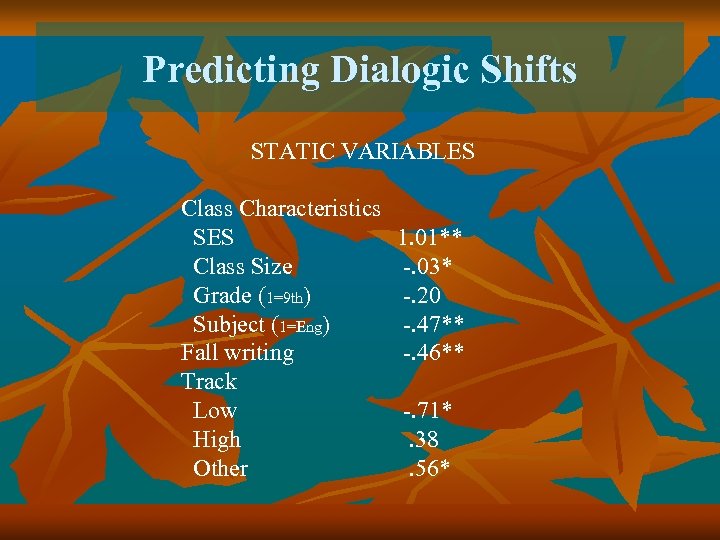

Predicting Dialogic Shifts STATIC VARIABLES Class Characteristics SES Class Size Grade (1=9 th) Subject (1=Eng) Fall writing Track Low High Other 1. 01** -. 03* -. 20 -. 47** -. 46** -. 71*. 38. 56*

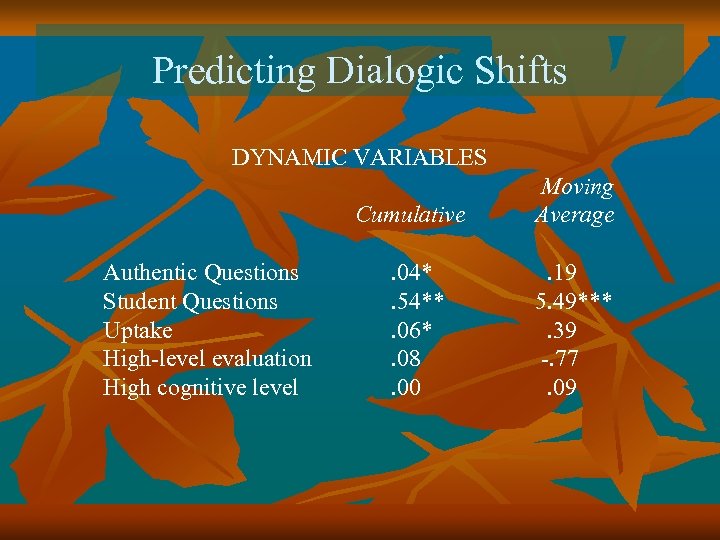

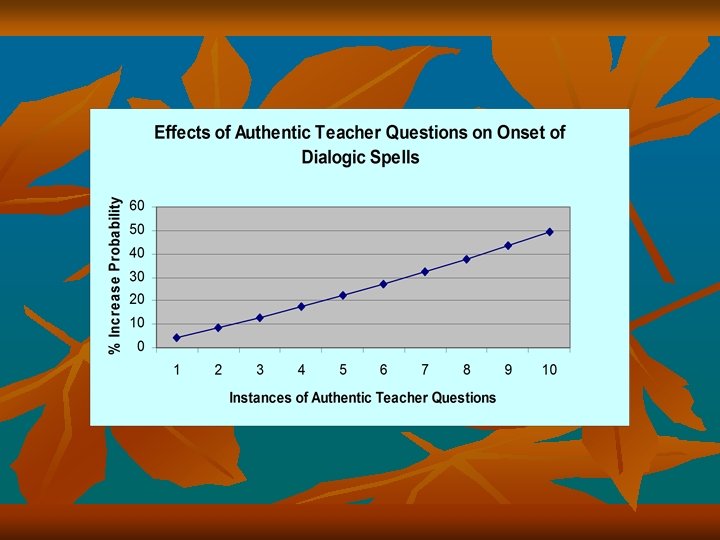

Predicting Dialogic Shifts DYNAMIC VARIABLES Cumulative Authentic Questions Student Questions Uptake High-level evaluation High cognitive level . 04*. 54**. 06*. 08. 00 Moving Average. 19 5. 49***. 39 -. 77. 09

Dialogic Bids n n Substantive student questions Teacher ‘moves’ n n n Uptake Authentic questions Encouraging students to respond to each other

Predicting Discussion STATIC VARIABLES Class Characteristics Class SES -. 18 Class Size -. 03 Grade (1=9 th). 51 Subject (1=Eng) -. 25 Fall writing. 39 Track Low -1. 97 High -. 14 Other. 02

Predicting Discussion DYNAMIC VARIABLES Cumulative Authentic Questions Student questions Uptake High-level evaluation High cognitive level . 01. 08. 04. 06. 04 Moving Average. 43 1. 38* 2. 02*** -. 37. 60*

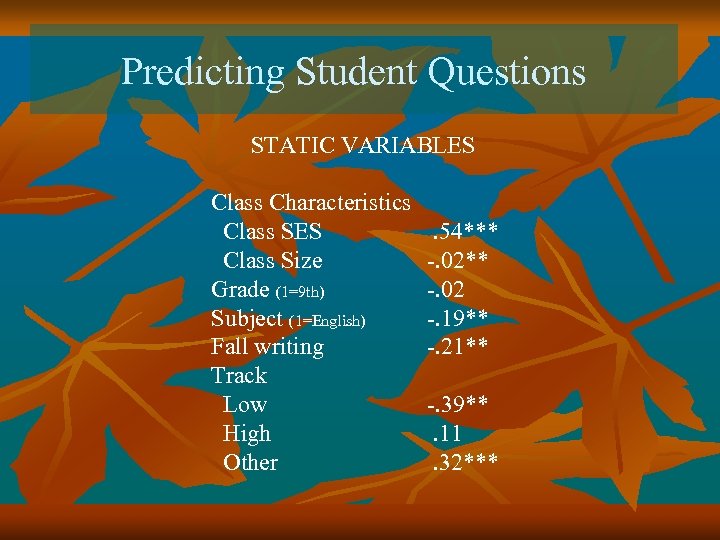

Predicting Student Questions STATIC VARIABLES Class Characteristics Class SES Class Size Grade (1=9 th) Subject (1=English) Fall writing Track Low High Other . 54*** -. 02 -. 19** -. 21** -. 39**. 11. 32***

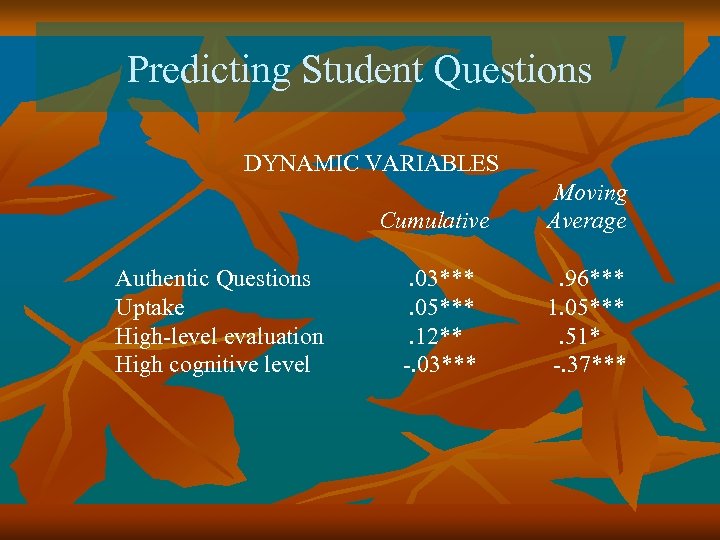

Predicting Student Questions DYNAMIC VARIABLES Cumulative Authentic Questions Uptake High-level evaluation High cognitive level Moving Average . 03***. 05***. 12** -. 03*** . 96*** 1. 05***. 51* -. 37***

Starting a discussion is a lot like starting a fire. With enough kindling of the right sort, accompanied by patience, ignition is possible, though perhaps not on the first or second try. Nystrand, Wu, & Gamoran, Questions in Time (2003)

Conclusion n. Whole classroom discourse manifests inertia and tends, as a STREAM, to continue direction and character until someone, usually the teacher, acts to change it n. The most common, default pattern of classroom discourse (recitation) is monologic. n. To transform monologic classroom discourse into dialogic, the teacher either does something or allows something; both moves work as dialogic bids. n. Dialogic bids effect the uptake & refraction of voices n. These voices are valorized n. Knowledge = valorized understandings n. Ideas EMERGE from the conversations and face-to-face interactions

Opening—and Sustaining—Dialogue: From Practice to Theory and Back Martin Nystrand The University of Wisconsin-Madison The International Association for the Improvement of Mother Tongue Education (IAIMTE) * Exeter, UK * March 27, 2007

81dff0bdb33a63e2b109a4b002616250.ppt