f3d62e27d83c587856a415fa9332460b.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 32

Olive oil-based intravenous lipid emulsion in pediatric patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation: A short-term prospective controlled trial Received 11 August 2008; accepted 28 April 2009. Available online 3 June 2009. Clinical Nutrition 營養師鄭秀英 9901

Introduction • Nutritional support has become an integral part of the supportive care of bone marrow transplanted (BMT) patients. In recent years, use of parenteral nutrition (PN) has markedly decreased in favor of enteral nutrition. • PN is indispensable when the gastrointestinal toxicity induced by high-dose chemotherapy and radiotherapy precludes optimal nutrient intake and utilization.

• Intravenous lipid emulsions (ILE) are important components of PN solutions that allow delivery of increased energy supply, provision of essential fatty acids (linoleic and α-linolenic acids) and fat-soluble vitamins. • The concern that excess of ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), present in the classic soybean or safflower-based ILE, might be immunosuppressive and proinflammatory, has led to the development of alternative lipid emulsions.

• Lipid emulsions based on mixtures of long-chain triglycerides (LCT) and medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) were formulated in order to reduce the ω-6 PUFA content. The ω-6 to ω-3 PUFA ratio is similar in both soybean and MCT/LCT lipid emulsions but the linoleic and αlinolenic content of MCT/LCT mixtures is half of that of soybean based ILE. • The MCT/LCT lipid emulsions have theoretical advantage of faster clearance from the blood stream, are less susceptible to peroxidation, have less impact on the reticuloendothelial system and cause less systemic inflammatory response due to lower ω6 PUFA content.

• There are no studies comparing the use of olive oil-based lipid emulsions to LCT/MCT emulsions in pediatric BMT patients. The objectives of this prospective, randomized study were to assess short-term safety and metabolic effects of olive oil-based (OO) lipid emulsions compared with MCT/LCT (M/L) lipid emulsions in the clinical setting of pediatric bone BMT patients.

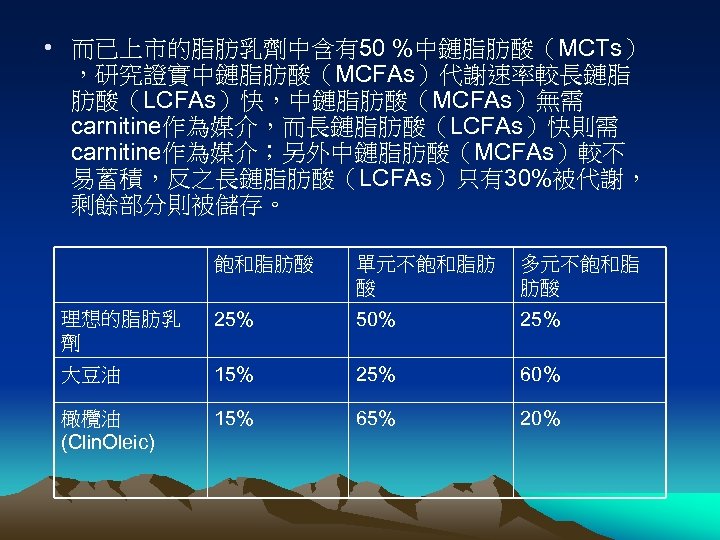

• 而已上市的脂肪乳劑中含有50 %中鏈脂肪酸(MCTs) ,研究證實中鏈脂肪酸(MCFAs)代謝速率較長鏈脂 肪酸(LCFAs)快,中鏈脂肪酸(MCFAs)無需 carnitine作為媒介,而長鏈脂肪酸(LCFAs)快則需 carnitine作為媒介;另外中鏈脂肪酸(MCFAs)較不 易蓄積,反之長鏈脂肪酸(LCFAs)只有30%被代謝, 剩餘部分則被儲存。 飽和脂肪酸 單元不飽和脂肪 酸 多元不飽和脂 肪酸 理想的脂肪乳 劑 25% 50% 25% 大豆油 15% 25% 60% 橄欖油 (Clin. Oleic) 15% 65% 20%

• 以大豆油為原料所製成的長鏈三酸甘油脂(LCT)已超過30年, 長鏈三酸甘油脂(LCT)可提供熱量且少有急性的副作用發生。 然而,與脂肪酸建議攝取量比較,它含有過多的不飽和脂肪酸 (PUFA),也就是過多的ω-6系列的脂肪酸,因此細胞膜中的 磷脂質所含linoleate, ω-6及ω-3的數量與輸注長鏈脂肪酸(LCT) 有關, • 另外,大豆油製成的乳劑富含γ-tocopherol,但僅含少量αtocophererol,然而α-tocophererol是維生素E中最具抗氧化功 能的同分異構物,同時也是唯一可藉肝內特殊的蛋白質再合成 的物質,持續輸注大豆油製成的乳劑會使得血漿蛋白中的αtocophererol減少,也就是將減少體內抗氧化的能力。 • 使用不飽和脂肪酸(PUFA)較低的脂肪乳劑,例如以 50: 50 比例的中鏈脂肪酸(MCT)和大豆油(LCT),或 80: 20比例 的橄欖油和大豆油,不會明顯地改變脂肪酸在細胞膜上的形式, 因此可避免因過氧化對細胞造成的傷害,尤其是含豐富的αtocophererol的脂肪乳劑,而且中鏈脂肪酸(MCT)有助於血 漿的廓清。

• 長期補充魚油對ω-3的保護以對抗發炎、血栓反應、癌症 及惡病質,同時報告也指出ω-3可維持器官移植後的組織 灌流。 • 近年來更發現ω-3可避免心律不整及血管纖維化;其中 EPA具上述功能,而DHA則與神經系統的成熟度及因早產 而引起的視網膜病變有關。 • 在前列腺素等的生成上,必需脂肪酸(EFA)直接與 arachidonic acid(AA)對抗,因為arachidonic acid (AA) 直接與eicosanoids的生成相關,花生四稀酸中的 eicosanoids為引起發炎、血栓的化學誘質前驅物,而相 對的從EPA調停的作用產生影響非常的微弱。 • 使用混合中鏈脂肪酸(MCT)的靜脈注射脂肪乳劑、大豆 油長鏈脂肪酸(LCT)及魚油三酸甘油脂之混合比例為 5: 4: 1

Patients and methods • 2. 1. Patient selection • We prospectively enrolled 28 children, aged 1– 18 years who underwent BMT at the BMT Unit of Pediatric Oncology-Hematology Department, Meyer Children's Hospital, Rambam Health Care Campus, during 2003– 2004 and needed PN support for at least 2 weeks. We expected that children with more severe mucositis and feeding difficulties that started earlier during conditioning will need longer periods of PN. • Children who received PN less than 8 days, had abnormal liver function tests before initiation of PN (total bilirubin >2. 5 mg/d. L, SGOT/SGPT >2. 5× upper limit of normal) and enteral daily intake of more than 50% of total calories were not included in the study. • The protocol of the study was approved by the human ethical committee of Rambam Health Care Campus. Written informed consent was obtained for each patient.

2. 2. Bone marrow transplantation • BMT was carried out according to standard protocols for autologous and allogeneic procedures. Total body irradiation and graft versus host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis were administered to allogeneic BMT recipients. Furthermore, patients were treated with highdose chemotherapy (busulfan and/or cyclophosphamide), followed by infusion of bone marrow from a histocompatible donor (allogeneic) or by reinfusion of previously cryopreserved autologous bone marrow (autologous). In addition to nutritional support, standard supportive care during the recovery phase included reverse isolation, antimicrobial therapy, GVHD and veno-occlusive disease prophylaxis and blood products support.

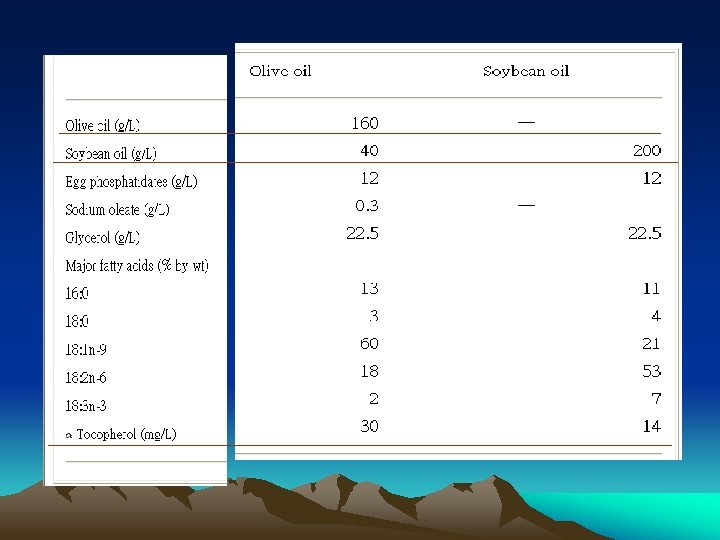

2. 3. Study protocol • The children included in the study were randomly assigned to PN containing one of two lipid emulsions, 1. M/L lipid emulsion (Lipofundin 20%, B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) which was composed of 50% MCTs and 50% LCTs 2. OO lipid emulsion (Cinoleic 20%, Baxter SAS, Maurepas, France). • PN solutions were supplied by TEVA Pharmaceuticals Inc. , Israel, to the pharmacy of Rambam Health Care Campus. Allocation of individuals to groups was done by following a table of computer-generated random numbers. • The investigators, attending and primary physicians, patients, the nursing staff and the study pharmacist who received coded PN solutions were blinded to randomization and treatment scheme.

• 商品名: 10% 500 MCT/LCT Lipofundin • 成分名:Soybean Oil/Triglycerides Medium Chain/Egg Phosphatides/Glycerin infusion 100 mg/100 mg/12 mg/25 mg/ml 20% 250 ml

• The other PN constituents were similar in both groups. All patients received individualized ‘all-in-one’ PN solution containing appropriate amounts of fluid, dextrose, l-amino acids (Primene 10%; Baxter Clintec, Maurepas, France), electrolytes, vitamins (MVI Pediatric; Mayne Pharma, USA) and trace elements (Peditrace; Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany). • The basal energy needs were calculated on the basis of WHO standards. Because of the controversies regarding the REE and energy requirements in patients with cancer or those undergoing BMT, we chose to supply 100% to 120% of REE according to nutritional and clinical status of each individual. 23

• Non-protein energy was provided as 70% dextrose and 30% lipid emulsion. The protein needs were calculated according to recommended protein intakes with PN (including energy from amino acids) and adjusted for each patient depending on clinical and nutritional status. 24 • Water and electrolytes content of PN solutions were adjusted daily on the basis of age requirements, intestinal losses and of serum chemistry test results. • PN support was initiated when patients’ oral/enteral intake decreased to less than 50% of estimated energy requirements. PN was discontinued when oral intake was >50% of the calculated maintenance energy needs for 3 consecutive days.

2. 4. Assessment of nutritional status • Weight, height and weight for age z-scores were calculated for each patient at the start of PN. • Afterwards, only weight was measured daily. • Energy and macro-nutrients intake from patient food records and PN were calculated daily by the ward dietitian.

2. 5. Laboratory investigations • Daily complete blood count, urea, electrolytes, serum bilirubin, liver transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, serum proteins, creatinine, inorganic phosphate, albumin, total cholesterol, triglycerides and coagulation status were routinely performed. • Serum Vitamin E, 25(OH)D 3 and plasma fatty acids profile were evaluated at the start of PN and on day 14 on PN. Plasma concentrations of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), an index of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, were assayed at the start and on the 14 th day of the study.

2. 6. Statistical analysis • Continuous variable are expressed as means ± SEM. Data were recorded at study entry (baseline) and at day 14. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (15. 0). • Comparisons between the two groups were performed using Student's t-test. • Change differences between groups were analyzed using analysis of covariance on change scores with baseline levels serving as covariates. • Because of the groups’ heterogeneity it was felt that the use of this statistical method would better measure the changes in the assessed variables. • Significance level for all comparisons was set at α = 0. 05.

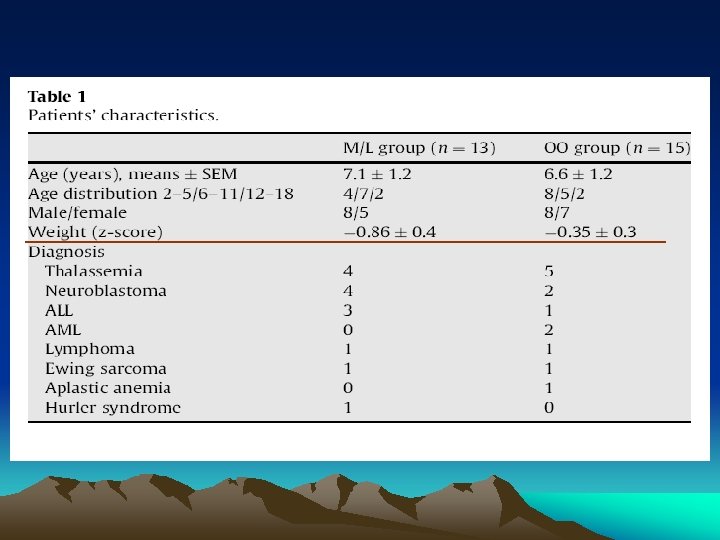

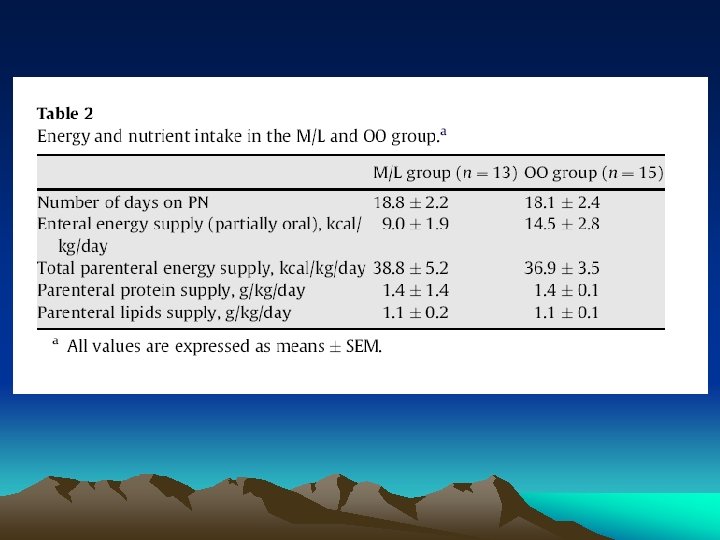

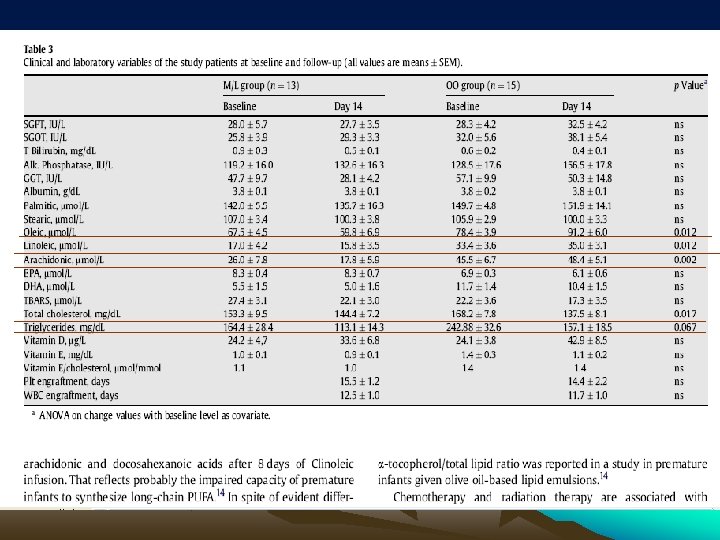

3. Results • Patients’ age, sex, body weight and primary diagnosis were not significantly different between the two PN protocols (Table 1). • Five of the 13 (38%) children in the M/L and 3/15 (20%) in the OO group underwent autologous BMT (NS). • The number of days on PN and the daily energy and macro-nutrients supply from enteral and PN were not different in the two groups (Table 2). • Means and SEMs of outcome variables at baseline and at day 14 on PN are presented in Table 3. Skewness and kurtosis analyses indicated no significant deviation from normality for all study variables.

3. 1. Safety results • There were no differences between the groups with regard to the success of engraftment, that occurred in 11/13 (85%) and 14/15 (93%) children from the M/L and OO group respectively, or post-transplantation time to engraftment. • There were no differences in the routine laboratory parameters including complete blood count, urea, electrolytes, serum bilirubin, transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, serum proteins, creatinine, inorganic phosphate and albumin and coagulation studies between the two groups at baseline or follow-up. • At the end of follow-up (day 14) the M/L group weight z-score was − 0. 43 ± 0. 4 compared to − 0. 86 ± 0. 4 at the start of PN (50% change in weight z-score) and the OO group weight zscore was − 0. 26 ± 0. 3 compared to − 0. 35 ± 0. 3 at the start of PN (26% change in weight z-score), p = 0. 03, meaning that compared to children in the OO group, the children in the M/L group gained more weight during the study period

3. 2. Lipid and fat-soluble vitamins profile and peroxidation status • The baseline serum triglycerides were higher in the OO group but not statistically significantly different from the M/L group. • Total serum cholesterol levels decreased significantly in the OO group at the end of the study period and there was a trend towards lower blood levels for triglycerides in the OO group when compared to the baseline levels. • Fatty acids profiles showed significant differences between the two groups. The results revealed that, with baseline levels controlled for, oleic, linoleic and arachidonic acids serum levels increased significantly at 14 days in the OO group. Eicosapentanoic (EPA) and docosahexanoic acids (DHA) levels were not different in the two groups at baseline or follow-up. • Serum vitamin E, vitamin E/cholesterol ratio, 25(OH)D 3 and plasma concentration of TBARS were not different within and between the groups at baseline or follow-up.

4. Discussion • This is the first study that assessed short-term safety and metabolic effects of OO lipid emulsion (Clinoleic) compared with M/L emulsion (Lipofundin) in the clinical setting of pediatric BMT patients. • We found no significant differences for hematological parameters, liver enzymes, vitamins concentration, plasma TBARS or success of engraftment. • The OO group had significantly higher plasma oleic acid and showed a favorable lipids profile as reflected by the decreased cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Therefore, our study suggests that OO lipid emulsions might be a safe and well tolerated alternative ILE for short-term use in children undergoing BMT.

• Plasma oleic acid concentration was, predictably, significantly higher in the OO group at follow-up. • In addition, linoleic acid and its long-chain homologue arachidonic acid levels also increased significantly after 14 days. • It is possible that the differences in the patients’ primary diagnoses, pre-transplantation treatments and conditioning regimens can be accounted for by the higher linoleic and arachidonic acid levels in the OO group. • the data suggest that essential fatty acids deficiency is not a limitation in the short term and even during longer treatment periods in spite of lower PUFA content of OO lipid emulsions

• Excessive ω-6 PUFA may alter the metabolism of ω-3 PUFA due to enzymatic competition for the desaturation and elongation; however, there was no appreciable effect on the plasma EPA and DHA levels that were similar in the two groups. • It was previously shown that premature infants had increased linoleic and linolenic acids but decreased plasma arachidonic and docosahexanoic acids after 8 days of Clinoleic infusion. That reflects probably the impaired capacity of premature infants to synthesize longchain PUFA

• In spite of evident differences in the fatty acid lipid profiles, due to different fatty acids composition of the two ILE, we found no disturbances in the metabolic profiles, plasma peroxidation status or clinical endpoints such as number of children who achieved engraftment or the time to engraftment. • Serum triglycerides levels were marginally lower in the OO group, suggesting that plasma clearance of olive oil-based ILE is at least as good, if not better than that of M/L emulsions. • The children in the OO group showed a significant reduction in cholesterol levels after the period of PN supplementation. A similar result has been reported previously by Goulet et al. in children treated with olive oil-based PN for 2 months. 15

• In the limited studies available in BMT patients, the administration of standard PN did not prevent decreases in plasma micronutrient antioxidants, such as vitamin E and β-carotene. 30 • As Clinoleic has a lower content of PUFA than MCT/LCT emulsions and supplies the α-tocopherol naturally found in olive oil, it has been suggested that it may have a positive impact by lowering the risk of lipid peroxidation. 32 • In our study no significant differences were recorded in vitamin E and vitamin E/cholesterol ratio that were within the normal range in both groups at baseline and day 14, although a higher plasma α-tocopherol/total lipid ratio was reported in a study in premature infants given olive oil-based lipid emulsions. 14

• The limitations to our study are mostly related to the small size and the heterogeneity of the study groups, the time-limited duration of the PN and short-term follow-up that could have decreased our ability to show the full impact of the intervention. • Our group included children with different primary diagnoses who receive either autologous or allogeneic BMT, have been through different treatments before BMT and followed different BMT protocols according to their primary diagnosis and stem cells source. • Although there was a relatively comparable distribution for types of primary disorders and BMT procedures, this was a heterogeneous group, which may account for the differences, even if not significant, observed in some of the clinical and laboratory parameters of the two groups. Because the study evaluated the outcomes at day 14, just at the time of engraftment, no child developed GVHD during the study.

• Therefore for the purpose of our study we considered the two groups as similar enough for comparison of the two lipid emulsion solutions. • Finally, the children in both groups received relatively low parenteral lipids supply. • It is possible that higher doses of OO lipid emulsions given for longer periods are associated with adverse effects, although Goulet et al. did not record such effects with 2 g/kg/day of OO lipid emulsion provided during a 2 -month period. 15

• With all these limitations, we can conclude that in children who underwent BMT and were in need of PN support, short-term provision of OO lipid emulsion was well tolerated as was the M/L lipid emulsion. • No adverse events were observed during the study period, suggesting that short-term use of olive oil-based intravenous lipid emulsions might be safe. • Larger studies and safety data during longer treatment periods are needed to confirm our data.

f3d62e27d83c587856a415fa9332460b.ppt