Old English.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 118

OLD ENGLISH

OUTLINE 1. Old English alphabet and pronunciation 2. Old English phonetics 2. 1. Word stress 2. 2. Origin of Old English vowels 2. 3. Origin of Old English consonants 3. Old English grammar 3. 1. The nominal system 3. 2. The verbal system 4. Old English vocabulary

![Old English Alphabet a æ b c [k] or [k’] (soft) d e f Old English Alphabet a æ b c [k] or [k’] (soft) d e f](https://present5.com/presentation/13222853_9666166/image-3.jpg)

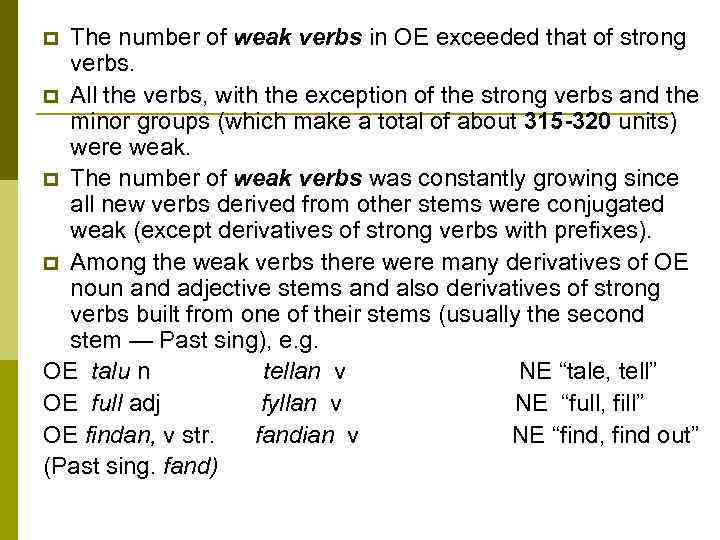

Old English Alphabet a æ b c [k] or [k’] (soft) d e f [f] or [v] [g], [g’], [γ] or [j] h [x], [x’] or [h] i l m n [n], [ ] o p r s [s] or [z] t þ, ð [ð] or [θ] u w x y [y]

![1) the fricative hard velar [γ]: OE da as [dáγas] - NE days; 1) the fricative hard velar [γ]: OE da as [dáγas] - NE days;](https://present5.com/presentation/13222853_9666166/image-6.jpg)

1) the fricative hard velar [γ]: OE da as [dáγas] - NE days; OE ā en [a: γen] - NE own; 2) the fricative soft palatal [j] or the semivowel [i]: OE dæ [dæj] - NE day; iest [jiest] - guest; eard [jæard] - yard; ēar [jǽar] - year; ē [je: ] - you; 3) occlusive hard velar [g]: OE l n (i. e. lan or lon ) [l g] - long, sin an [si gan] - sing; 4) occlusive soft palatal [g’] ([ ]): OE sen an [se g’an] - singe.

![h 1) the glottal fricative [h] – at the beginning of the syllable: OE h 1) the glottal fricative [h] – at the beginning of the syllable: OE](https://present5.com/presentation/13222853_9666166/image-7.jpg)

h 1) the glottal fricative [h] – at the beginning of the syllable: OE hūs [hu: s] – NE house, ehīeran [jehīeran] - hear; 2) the velar fricative [χ]: OE eahta [ aχta] - eight; seolh [seolχ] - seal; 3) the soft palatal fricative [ç]: OE siehþ [sięçþ] - sees; miehti [míęçtij] - mighty.

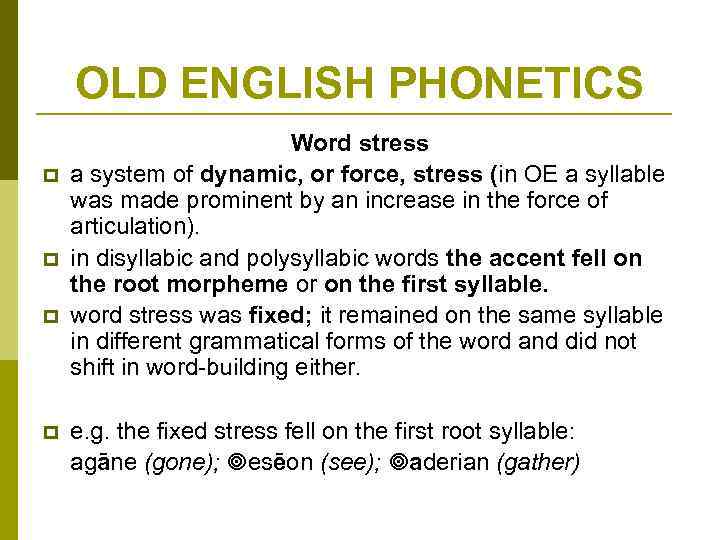

OLD ENGLISH PHONETICS p p Word stress a system of dynamic, or force, stress (in OE a syllable was made prominent by an increase in the force of articulation). in disyllabic and polysyllabic words the accent fell on the root morpheme or on the first syllable. word stress was fixed; it remained on the same syllable in different grammatical forms of the word and did not shift in word-building either. e. g. the fixed stress fell on the first root syllable: agāne (gone); esēon (see); aderian (gather)

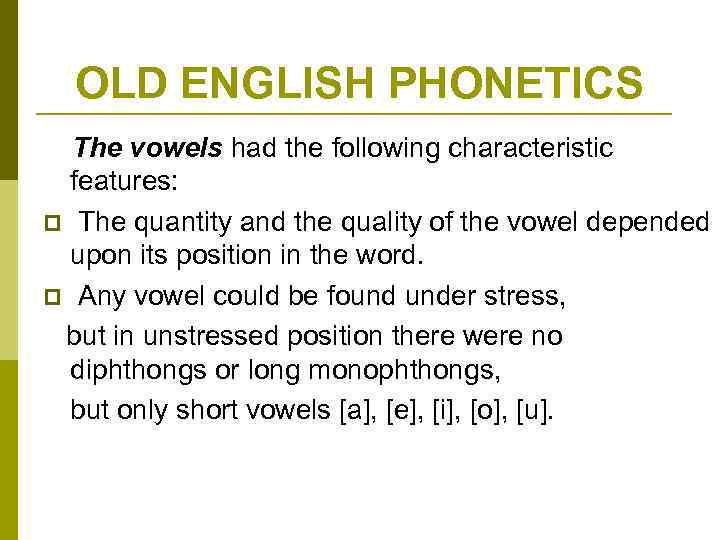

OLD ENGLISH PHONETICS The vowels had the following characteristic features: p The quantity and the quality of the vowel depended upon its position in the word. p Any vowel could be found under stress, but in unstressed position there were no diphthongs or long monophthongs, but only short vowels [a], [e], [i], [o], [u].

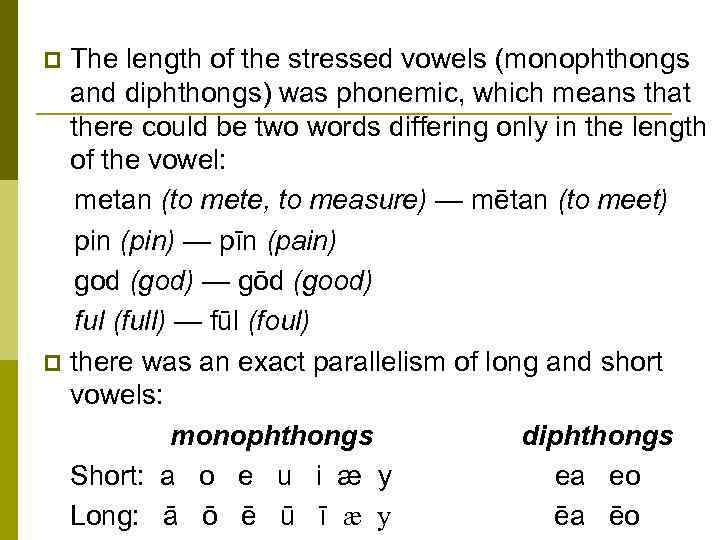

The length of the stressed vowels (monophthongs and diphthongs) was phonemic, which means that there could be two words differing only in the length of the vowel: metan (to mete, to measure) — mētan (to meet) pin (pin) — pīn (pain) god (god) — gōd (good) ful (full) — fūl (foul) p there was an exact parallelism of long and short vowels: monophthongs diphthongs Short: a o e u i æ y ea eo Long: ā ō ē ū ī æ y ēa ēo p

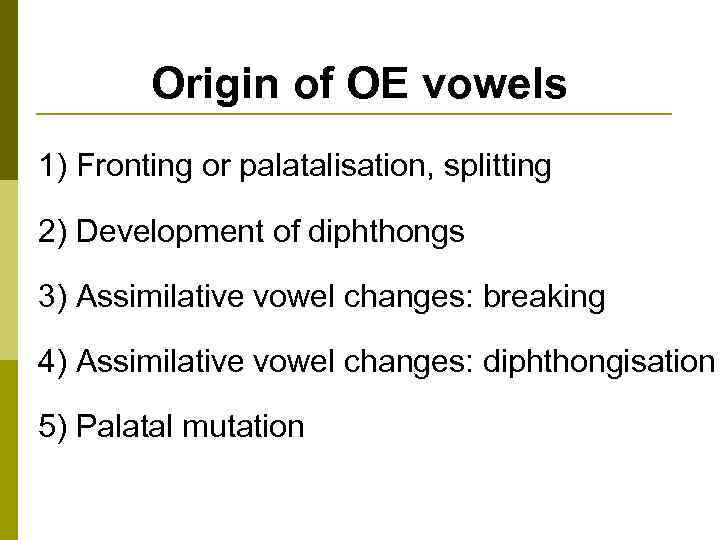

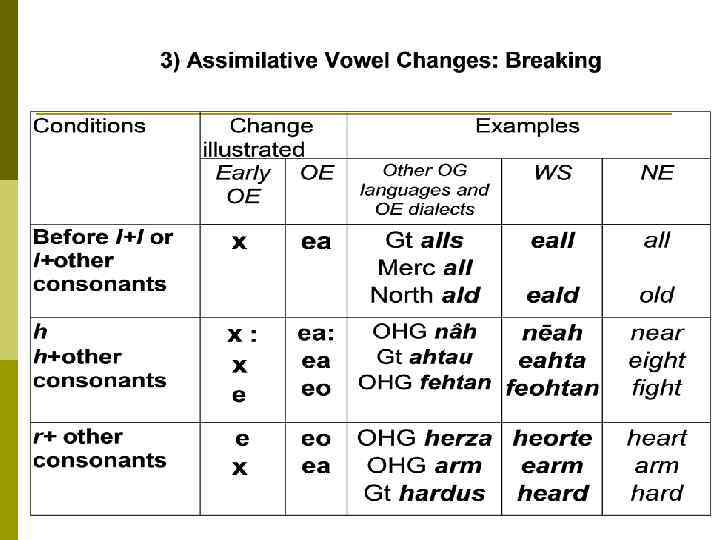

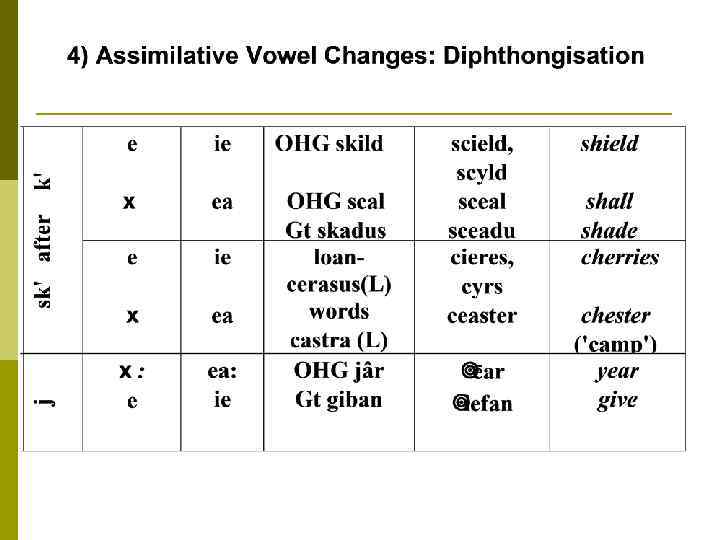

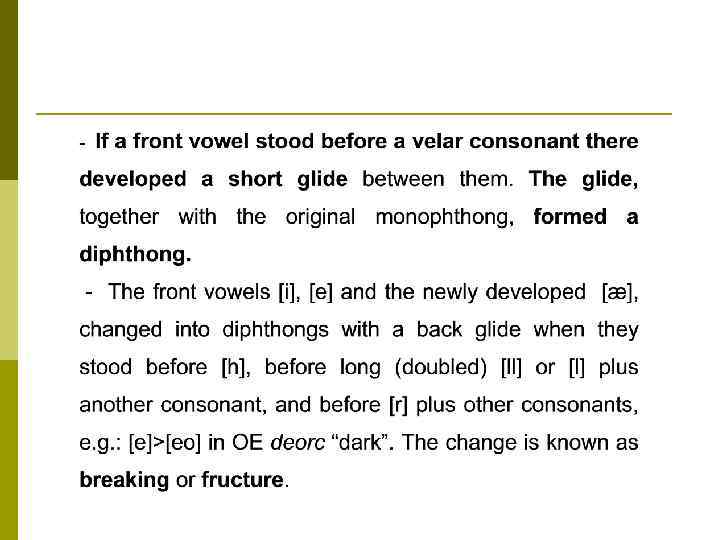

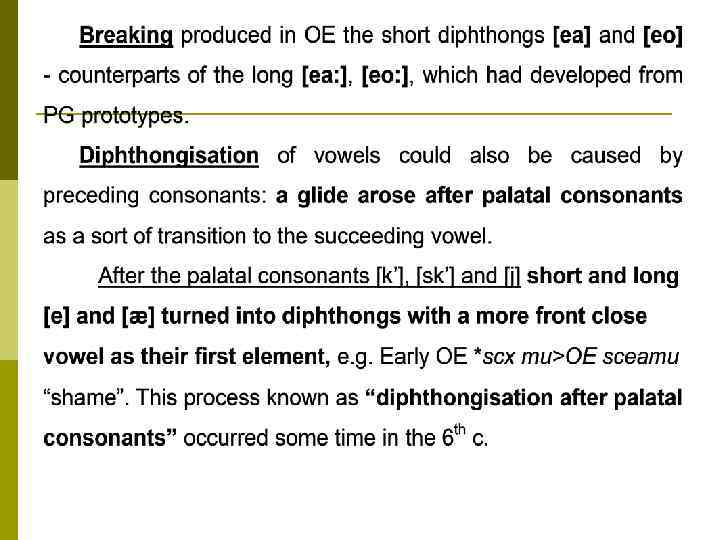

Origin of OE vowels 1) Fronting or palatalisation, splitting 2) Development of diphthongs 3) Assimilative vowel changes: breaking 4) Assimilative vowel changes: diphthongisation 5) Palatal mutation

![1) In Early OE the West and North Germanic [Q, R] were fronted and 1) In Early OE the West and North Germanic [Q, R] were fronted and](https://present5.com/presentation/13222853_9666166/image-13.jpg)

1) In Early OE the West and North Germanic [Q, R] were fronted and split: p fronting or palatalisation of [Q, R] [Q] > [x]; [R] > [x: ] p splitting of [Q, R]

![Splitting of [a] and [a: ] in Early Old English Splitting of [a] and [a: ] in Early Old English](https://present5.com/presentation/13222853_9666166/image-14.jpg)

Splitting of [a] and [a: ] in Early Old English

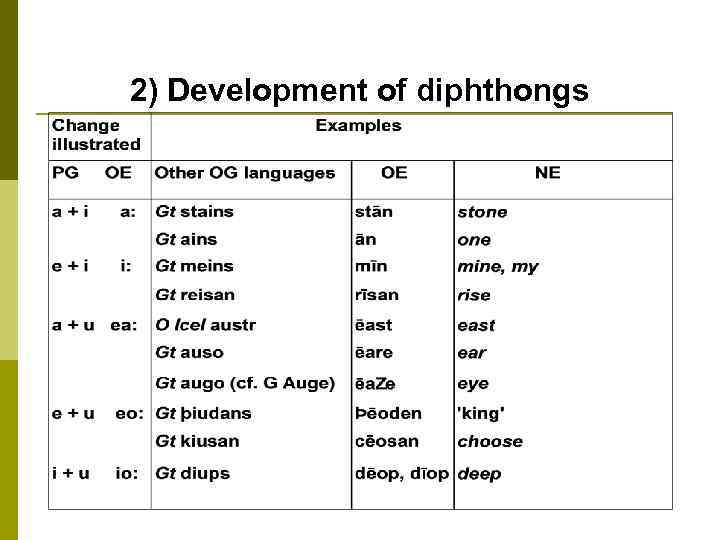

2) Development of diphthongs

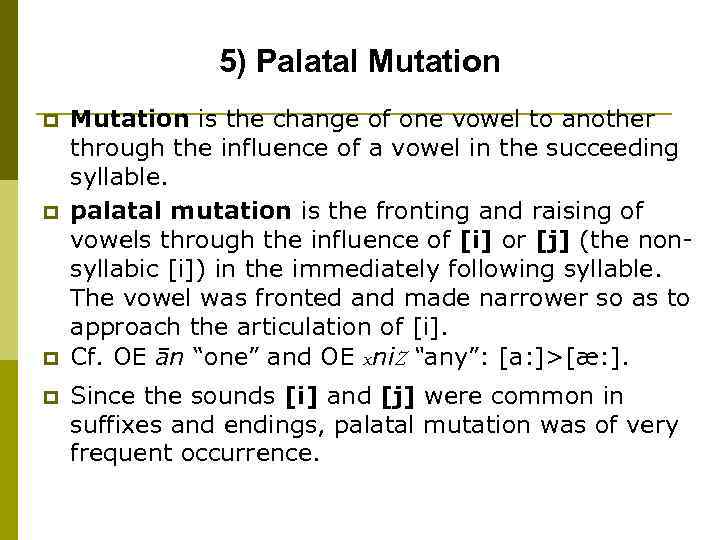

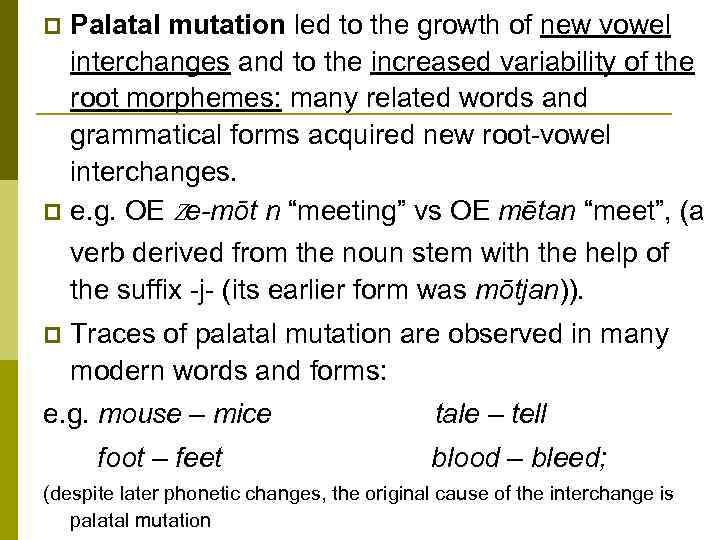

5) Palatal Mutation p p Mutation is the change of one vowel to another through the influence of a vowel in the succeeding syllable. palatal mutation is the fronting and raising of vowels through the influence of [i] or [j] (the nonsyllabic [i]) in the immediately following syllable. The vowel was fronted and made narrower so as to approach the articulation of [i]. Cf. OE ān “one” and OE xni. Z “any”: [a: ]>[æ: ]. Since the sounds [i] and [j] were common in suffixes and endings, palatal mutation was of very frequent occurrence.

Palatal mutation led to the growth of new vowel interchanges and to the increased variability of the root morphemes: many related words and grammatical forms acquired new root-vowel interchanges. p e. g. OE Ze mōt n “meeting” vs OE mētan “meet”, (a verb derived from the noun stem with the help of the suffix -j- (its earlier form was mōtjan)). p p Traces of palatal mutation are observed in many modern words and forms: e. g. mouse – mice foot – feet tale – tell blood – bleed; (despite later phonetic changes, the original cause of the interchange is palatal mutation

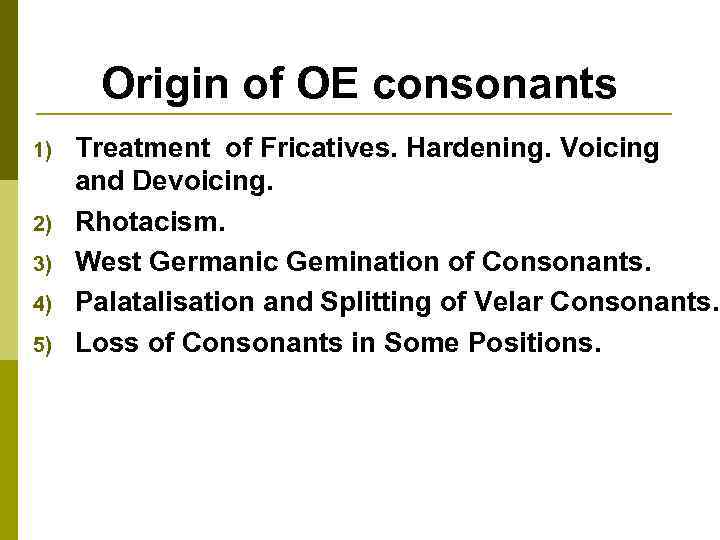

Origin of OE consonants 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Treatment of Fricatives. Hardening. Voicing and Devoicing. Rhotacism. West Germanic Gemination of Consonants. Palatalisation and Splitting of Velar Consonants. Loss of Consonants in Some Positions.

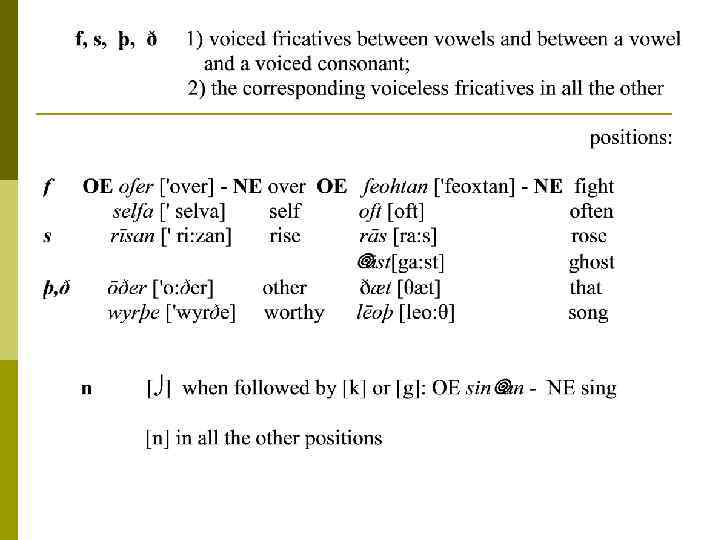

Origin of OE consonants p Treatment of Fricatives. Hardening. Voicing and Devoicing After the changes under Grimm’s Law and Verner’s Law, PG had the following two sets of fricative consonants: voiceless [f, θ, x, s] and voiced [v, ð, γ, z] were hardened voiceless [f, θ, x, s] developed new voiced allophones.

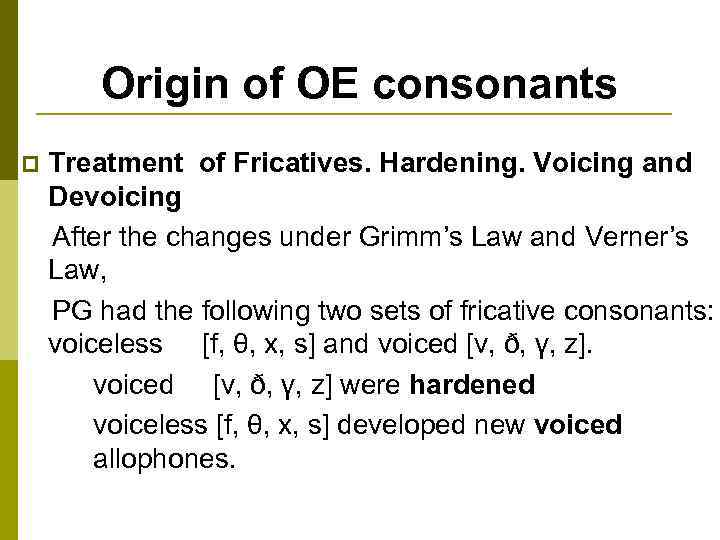

Hardening

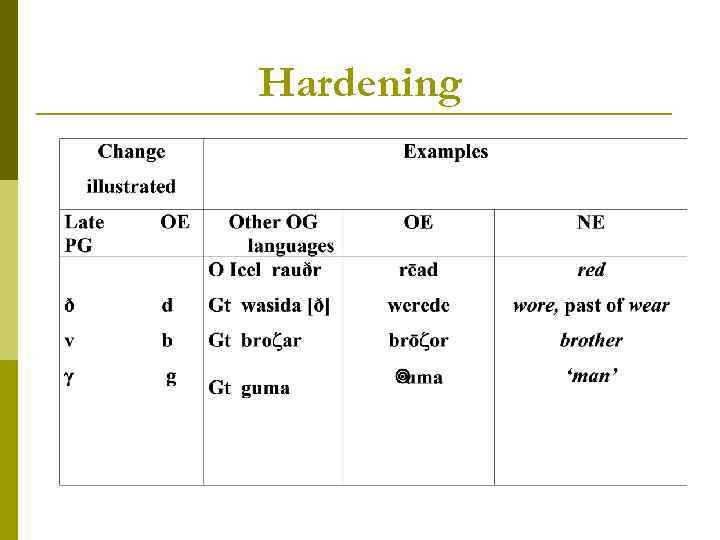

Voicing or devoicing

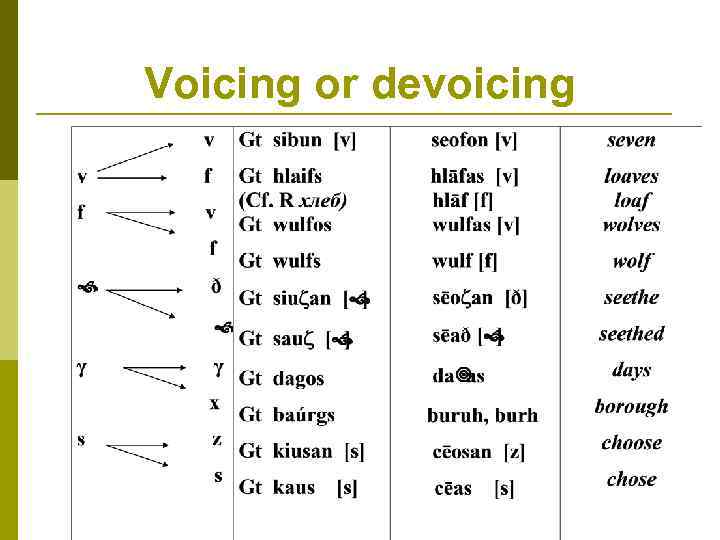

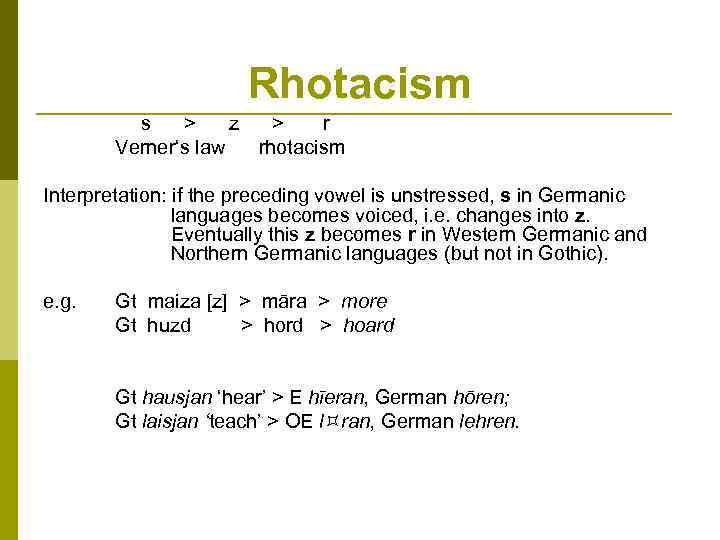

Rhotacism s > z > r Verner‘s law rhotacism Interpretation: if the preceding vowel is unstressed, s in Germanic languages becomes voiced, i. e. changes into z. Eventually this z becomes r in Western Germanic and Northern Germanic languages (but not in Gothic). e. g. Gt maiza [z] > māra > more Gt huzd > hord > hoard Gt hausjan ‘hear’ > E hīeran, German hōren; Gt laisjan ‘teach’ > OE l ran, German lehren.

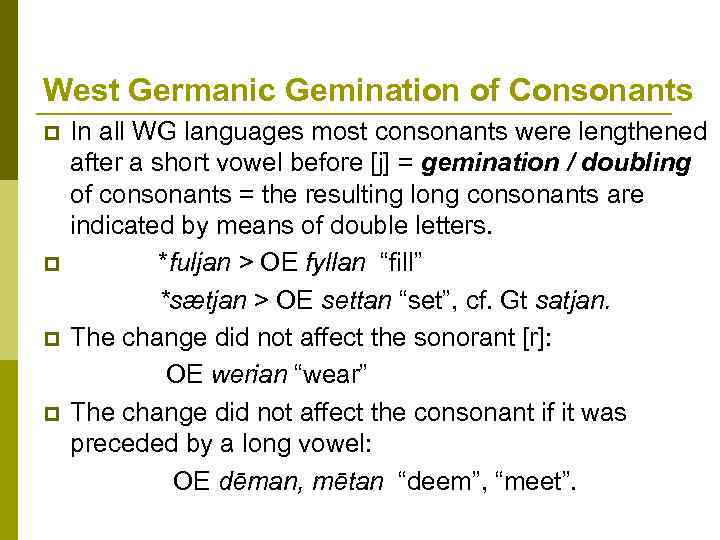

West Germanic Gemination of Consonants p p In all WG languages most consonants were lengthened after a short vowel before [j] = gemination / doubling of consonants = the resulting long consonants are indicated by means of double letters. *fuljan > OE fyllan “fill” *sætjan > OE settan “set”, cf. Gt satjan. The change did not affect the sonorant [r]: OE werian “wear” The change did not affect the consonant if it was preceded by a long vowel: OE dēman, mētan “deem”, “meet”.

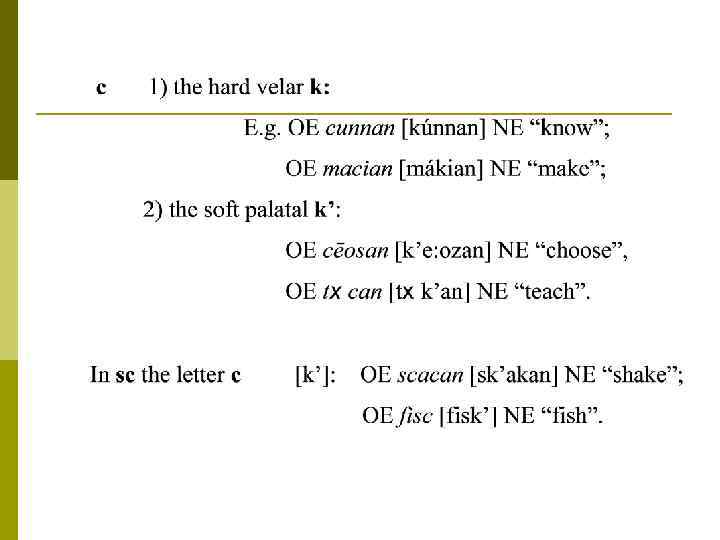

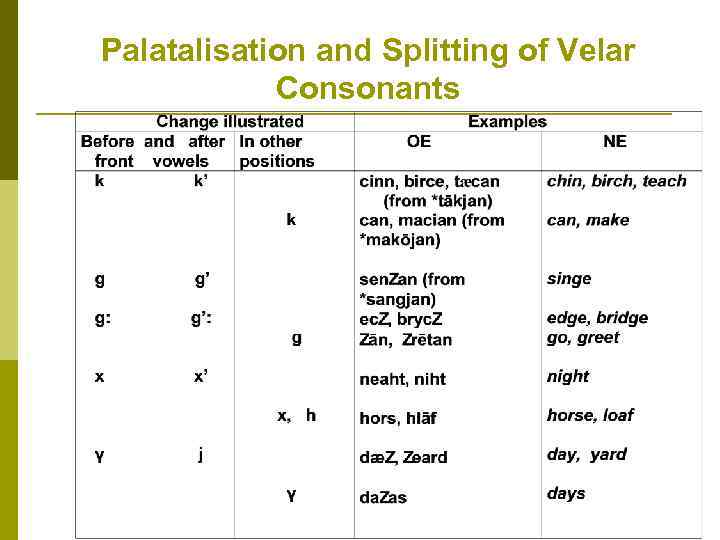

Palatalisation and Splitting of Velar Consonants

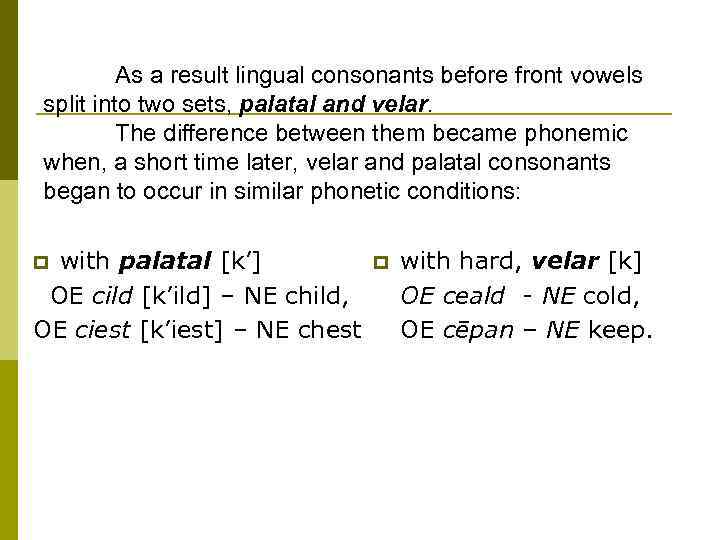

As a result lingual consonants before front vowels split into two sets, palatal and velar. The difference between them became phonemic when, a short time later, velar and palatal consonants began to occur in similar phonetic conditions: with palatal [k’] OE cild [k’ild] – NE child, OE ciest [k’iest] – NE chest p p with hard, velar [k] OE ceald - NE cold, OE cēpan – NE keep.

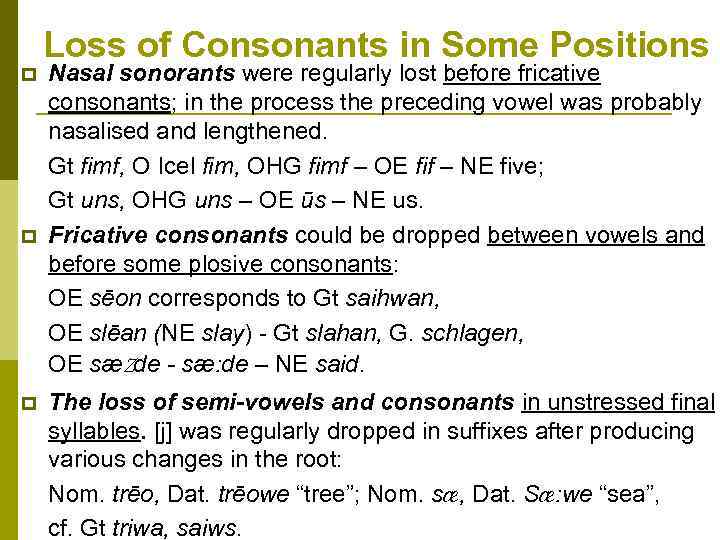

Loss of Consonants in Some Positions p p p Nasal sonorants were regularly lost before fricative consonants; in the process the preceding vowel was probably nasalised and lengthened. Gt fimf, O Icel fim, OHG fimf – OE fif – NE five; Gt uns, OHG uns – OE ūs – NE us. Fricative consonants could be dropped between vowels and before some plosive consonants: OE sēon corresponds to Gt saihwan, OE slēan (NE slay) - Gt slahan, G. schlagen, OE sæZde sæ: de – NE said. The loss of semi-vowels and consonants in unstressed final syllables. [j] was regularly dropped in suffixes after producing various changes in the root: Nom. trēo, Dat. trēowe “tree”; Nom. sæ, Dat. Sæ: we “sea”, cf. Gt triwa, saiws.

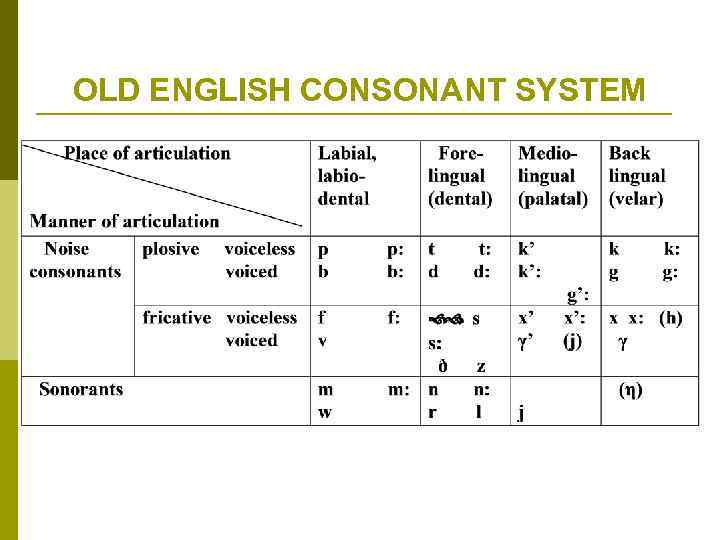

OLD ENGLISH CONSONANT SYSTEM

![the consonants were few; p some of the modern sounds were non-existent ([ ], the consonants were few; p some of the modern sounds were non-existent ([ ],](https://present5.com/presentation/13222853_9666166/image-33.jpg)

the consonants were few; p some of the modern sounds were non-existent ([ ], [t ], [d ]); p Several correlated sets; p The quality of the consonant very much depended on its position in the word, especially: the resonance (voiced and voiceless sounds: hlāf [f] (loaf) — hlāford [v] (lord, "bread keeper); articulation (palatal and velar sounds: climban [k] (to climb) — cild [k’] (child); p Difference in length. p

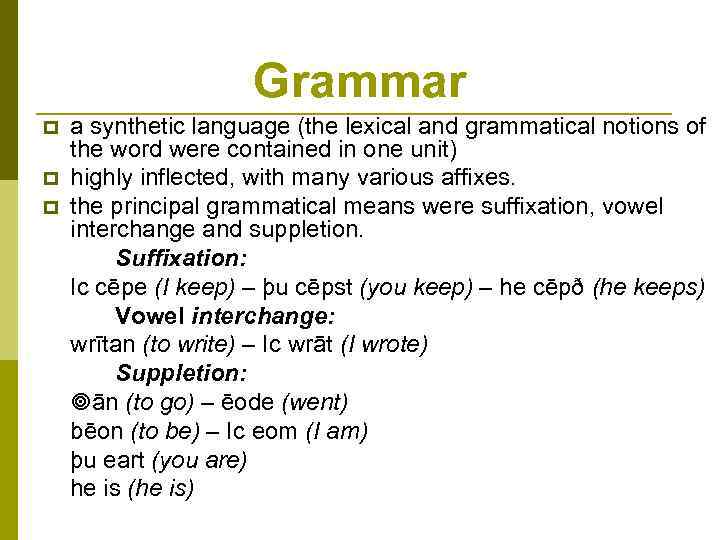

Grammar p p p a synthetic language (the lexical and grammatical notions of the word were contained in one unit) highly inflected, with many various affixes. the principal grammatical means were suffixation, vowel interchange and suppletion. Suffixation: Ic cēpe (I keep) – þu cēpst (you keep) – he cēpð (he keeps) Vowel interchange: wrītan (to write) – Ic wrāt (I wrote) Suppletion: ān (to go) – ēode (went) bēon (to be) – Ic eom (I am) þu eart (you are) he is (he is)

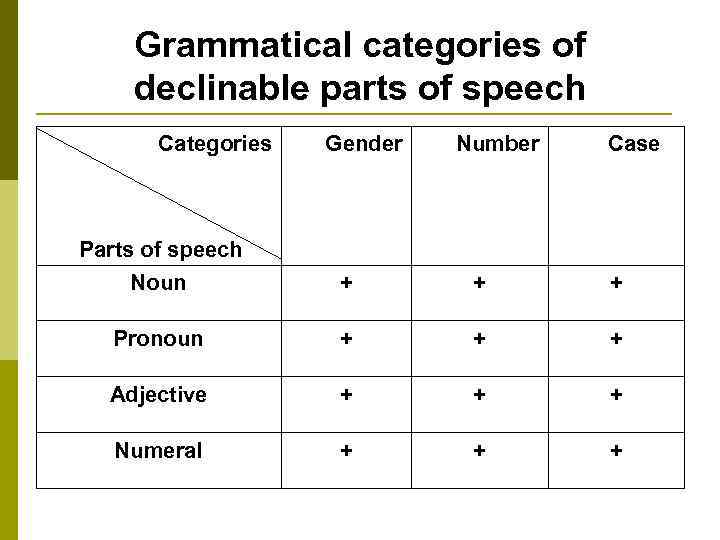

Grammatical categories of declinable parts of speech Categories Gender Number Case Parts of speech Noun + + + Pronoun + + + Adjective + + + Numeral + + +

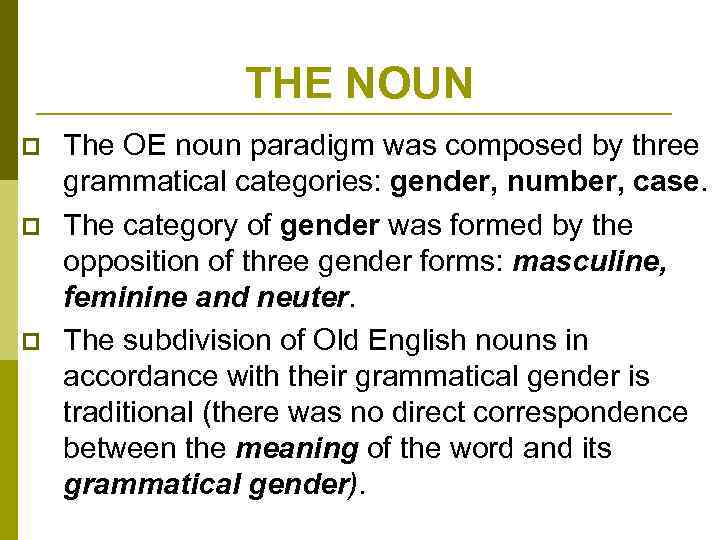

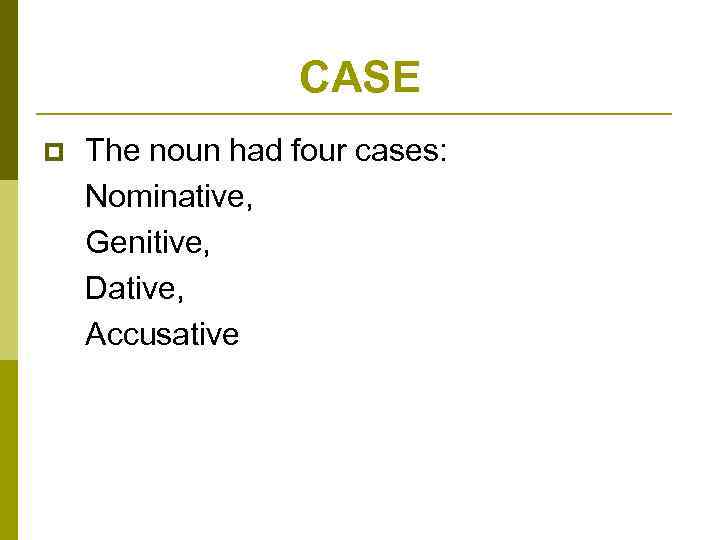

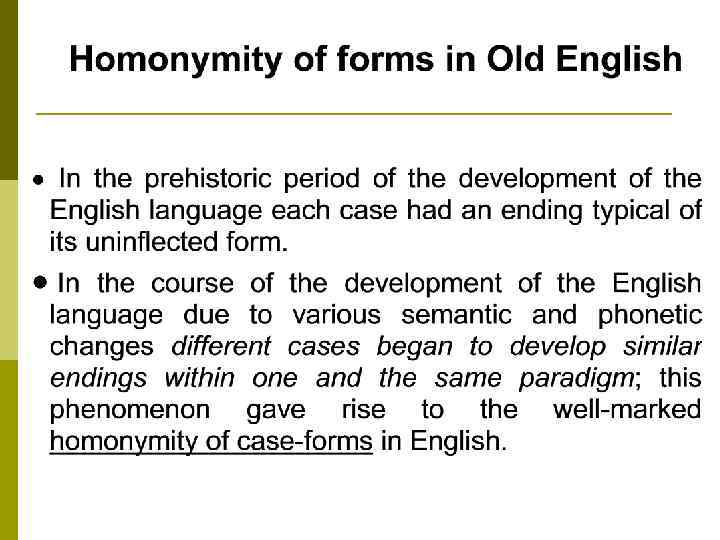

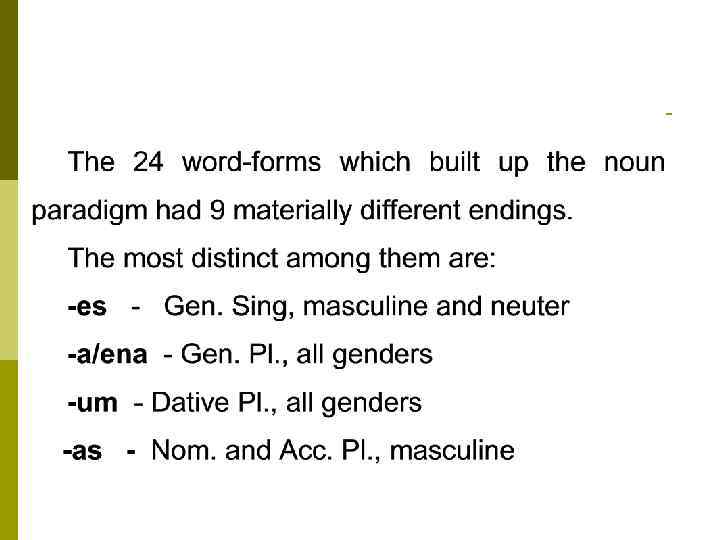

THE NOUN p p p The OE noun paradigm was composed by three grammatical categories: gender, number, case. The category of gender was formed by the opposition of three gender forms: masculine, feminine and neuter. The subdivision of Old English nouns in accordance with their grammatical gender is traditional (there was no direct correspondence between the meaning of the word and its grammatical gender).

Male beings fxder “father” sunu “son” Masculine Lifeless things Abstract notions hlāf “bread” stenc “stench” stān “stone” fxr “fear” cyning “king” hrōf “roof” nama “name” dōm “doom” Feminine Female beings Lifeless things mōdor “mother” tun. Ze “tongue” dohter “daughter” meolc “milk” Abstract notions tryw. Du “truth” huntin. Z “hunting” cwēn “queen” lufu “love” Living beings cicen “chicken” mx. Zden “maiden” Neuter Lifeless things ēa. Ze “eye” scip “ship” Abstract notions mōd “mood” riht “right”

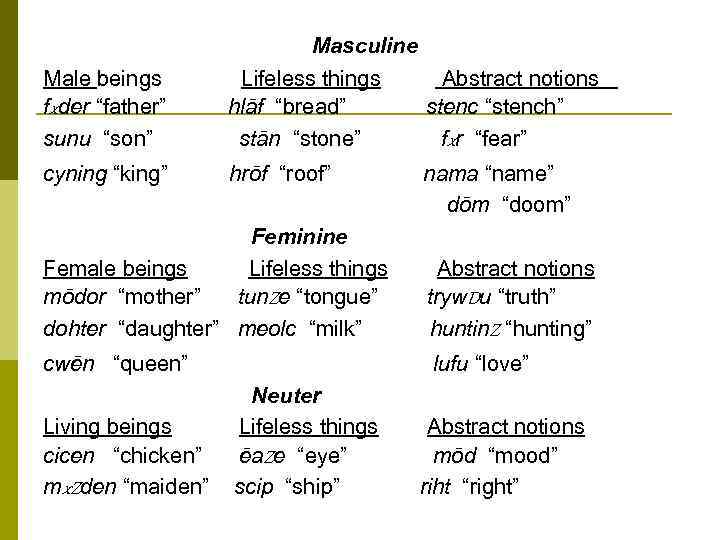

Number The grammatical category of number was formed by the opposition of two categorial forms: the singular and the plural. Nominative Singular Nominative Plural fisc “fish” fiscas a e “eye” a an t “tooth” t scip “ship” scipu The singular and plural forms were well distinguished formally in all the declensions, there were very few homonymous forms.

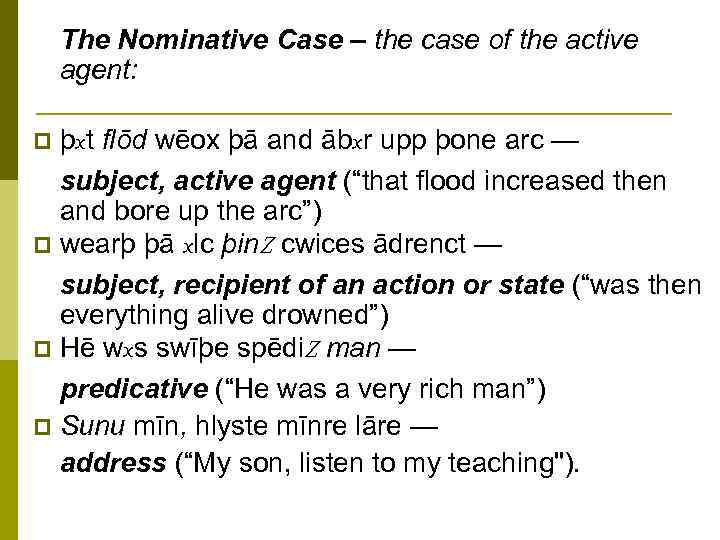

CASE p The noun had four cases: Nominative, Genitive, Dative, Accusative

The Nominative Case – the case of the active agent: þxt flōd wēox þā and ābxr upp þone arc — subject, active agent (“that flood increased then and bore up the arc”) p wearþ þā xlc þin. Z cwices ādrenct — subject, recipient of an action or state (“was then everything alive drowned”) p Hē wxs swīþe spēdi. Z man — predicative (“He was a very rich man”) p Sunu mīn, hlyste mīnre lāre — address (“My son, listen to my teaching"). p

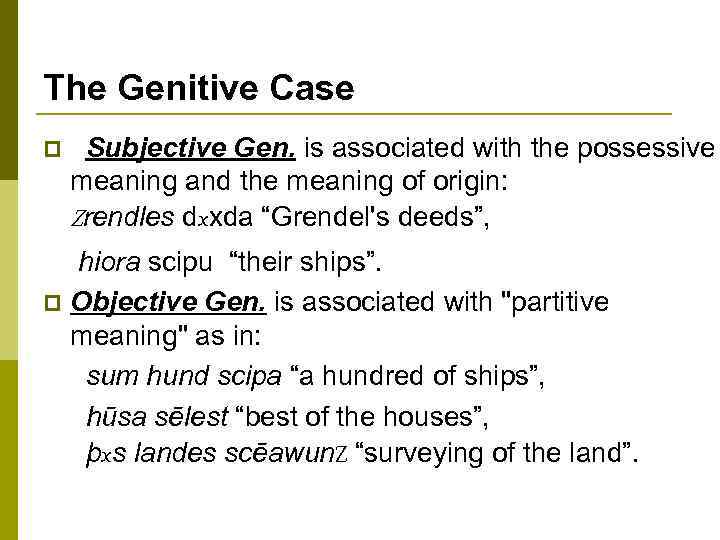

The Genitive Case p Subjective Gen. is associated with the possessive meaning and the meaning of origin: Zrendles dxxda “Grendel's deeds”, hiora scipu “their ships”. p Objective Gen. is associated with "partitive meaning" as in: sum hund scipa “a hundred of ships”, hūsa sēlest “best of the houses”, þxs landes scēawun. Z “surveying of the land”.

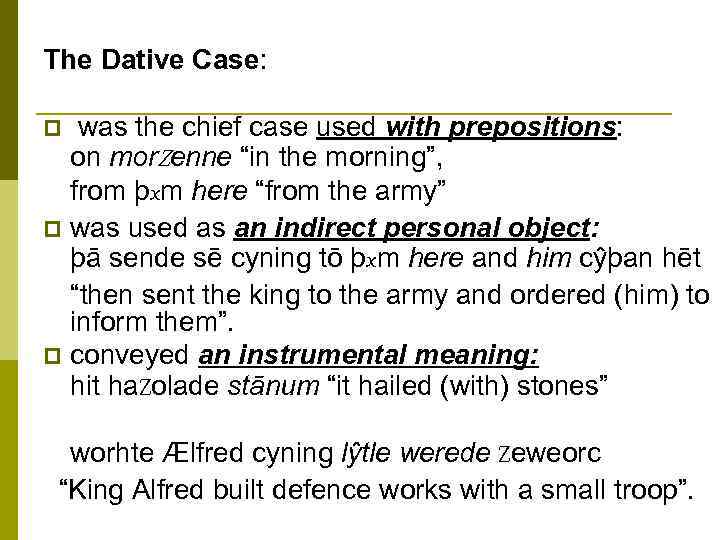

The Dative Case: was the chief case used with prepositions: on mor. Zenne “in the morning”, from þxm here “from the army” p was used as an indirect personal object: þā sende sē cyning tō þxm here and him cŷþan hēt “then sent the king to the army and ordered (him) to inform them”. p conveyed an instrumental meaning: hit ha. Zolade stānum “it hailed (with) stones” p worhte Ælfred cyning lŷtle werede Zeweorc “King Alfred built defence works with a small troop”.

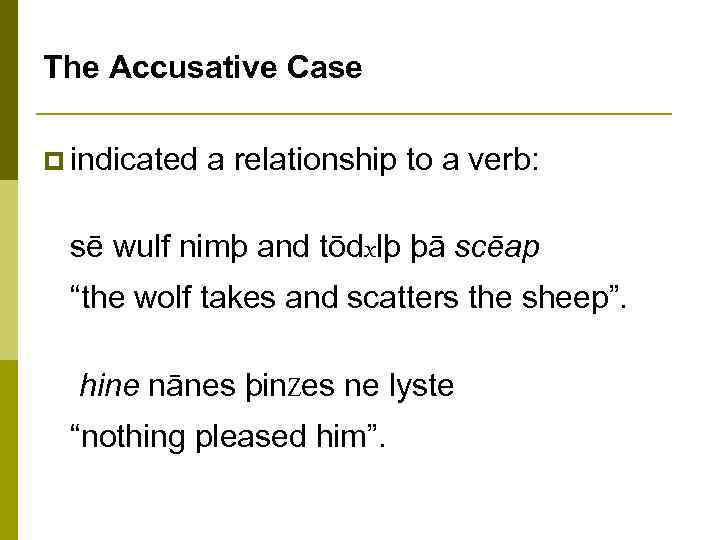

The Accusative Case p indicated a relationship to a verb: sē wulf nimþ and tōdxlþ þā scēap “the wolf takes and scatters the sheep”. hine nānes þin. Zes ne lyste “nothing pleased him”.

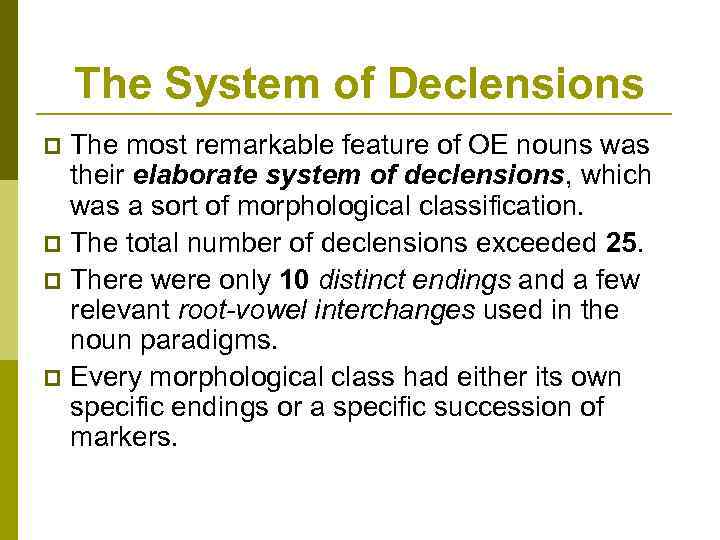

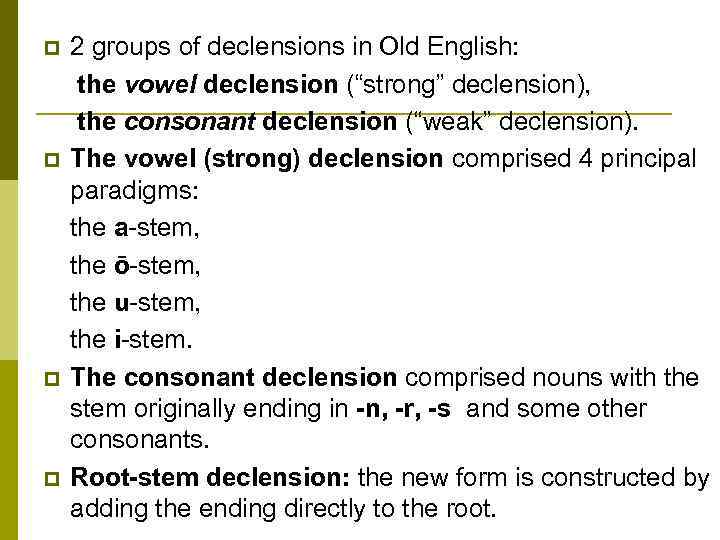

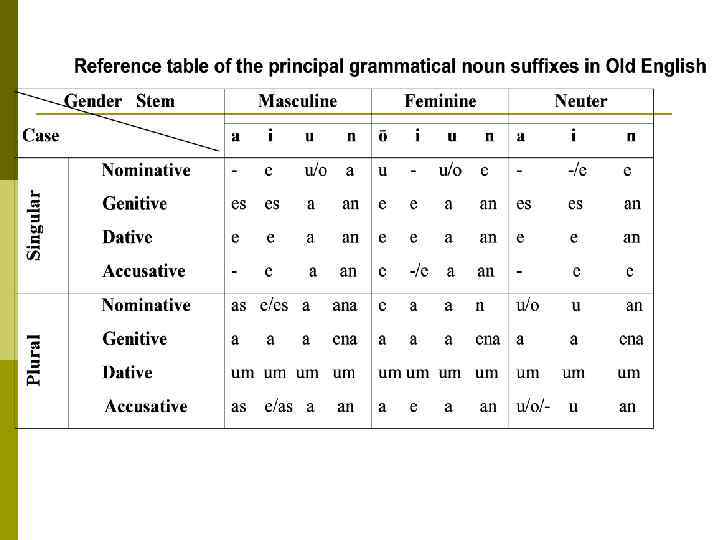

The System of Declensions The most remarkable feature of OE nouns was their elaborate system of declensions, which was a sort of morphological classification. p The total number of declensions exceeded 25. p There were only 10 distinct endings and a few relevant root vowel interchanges used in the noun paradigms. p Every morphological class had either its own specific endings or a specific succession of markers. p

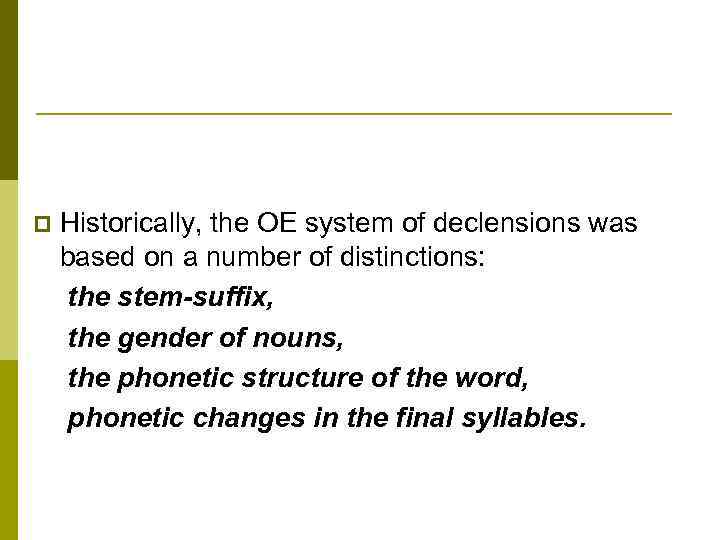

p Historically, the OE system of declensions was based on a number of distinctions: the stem-suffix, the gender of nouns, the phonetic structure of the word, phonetic changes in the final syllables.

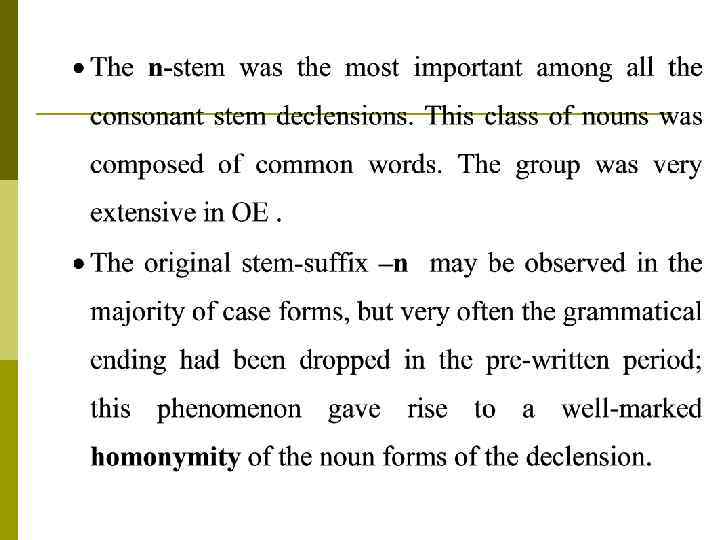

p p 2 groups of declensions in Old English: the vowel declension (“strong” declension), the consonant declension (“weak” declension). The vowel (strong) declension comprised 4 principal paradigms: the a-stem, the ō-stem, the u-stem, the i-stem. The consonant declension comprised nouns with the stem originally ending in -n, -r, -s and some other consonants. Root-stem declension: the new form is constructed by adding the ending directly to the root.

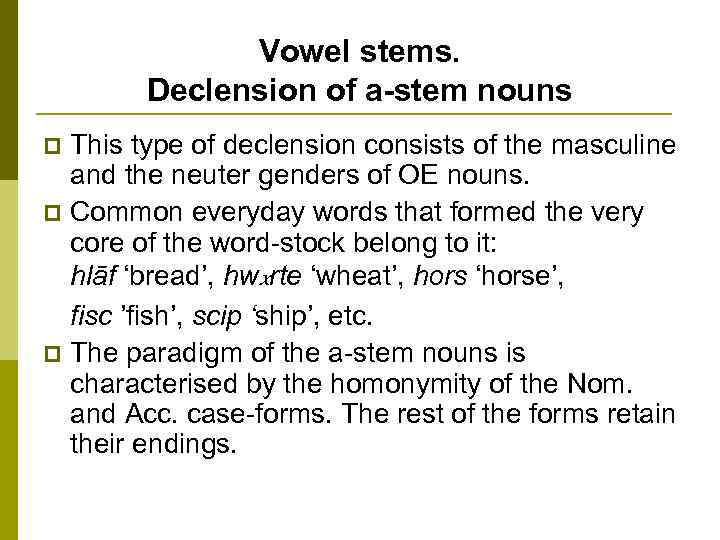

Vowel stems. Declension of a-stem nouns This type of declension consists of the masculine and the neuter genders of OE nouns. p Common everyday words that formed the very core of the word-stock belong to it: hlāf ‘bread’, hwxrte ‘wheat’, hors ‘horse’, fisc ’fish’, scip ‘ship’, etc. p The paradigm of the a-stem nouns is characterised by the homonymity of the Nom. and Acc. case-forms. The rest of the forms retain their endings. p

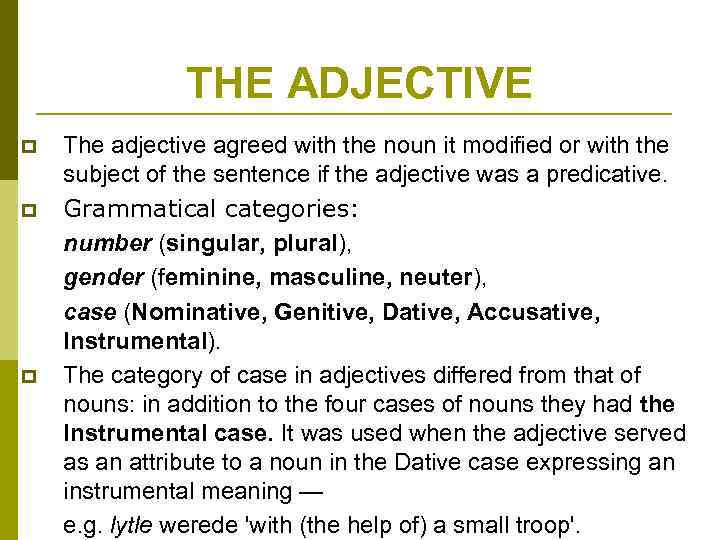

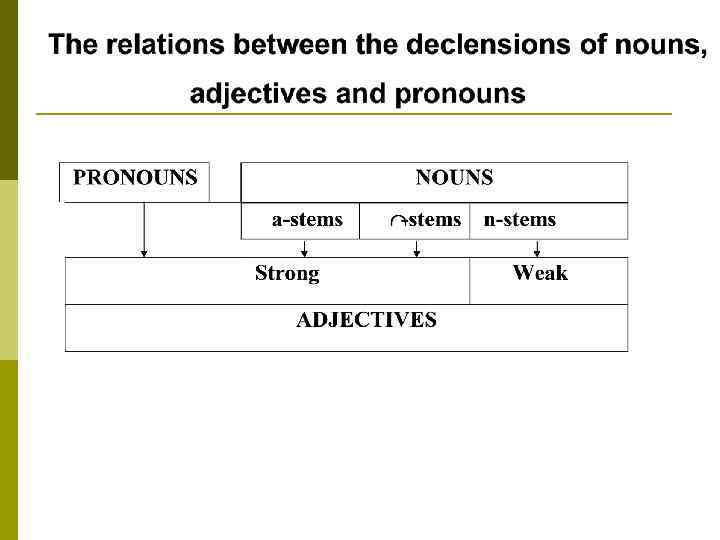

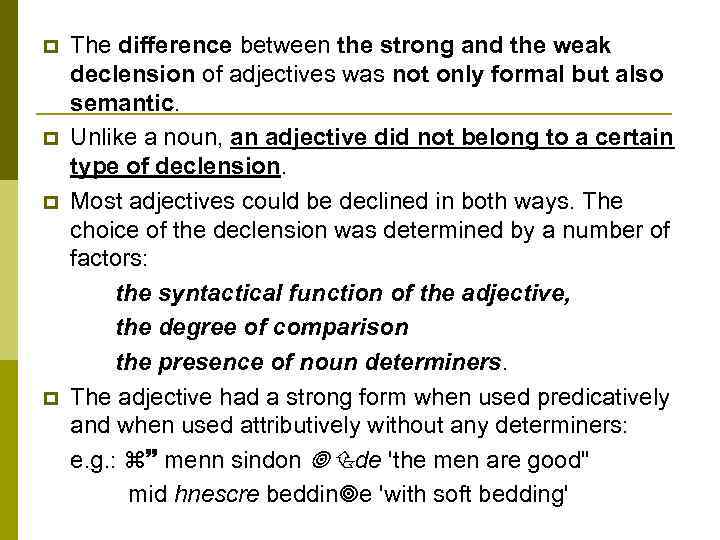

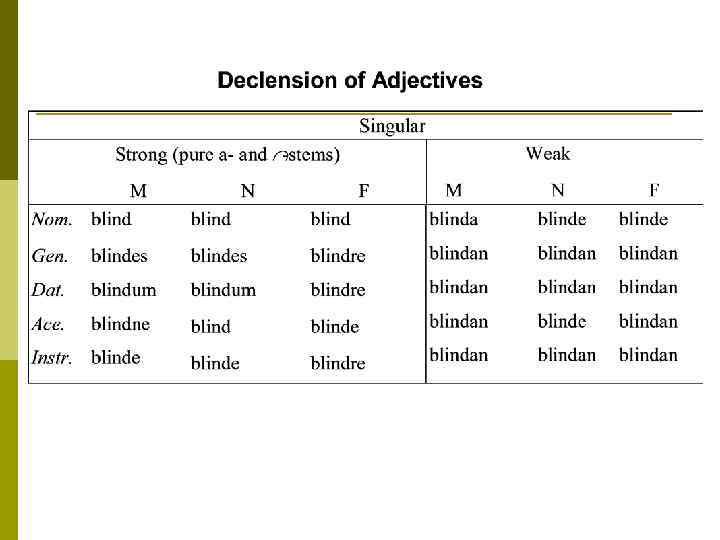

THE ADJECTIVE p p p The adjective agreed with the noun it modified or with the subject of the sentence if the adjective was a predicative. Grammatical categories: number (singular, plural), gender (feminine, masculine, neuter), case (Nominative, Genitive, Dative, Accusative, Instrumental). The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had the Instrumental case. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dative case expressing an instrumental meaning — e. g. lytle werede 'with (the help of) a small troop'.

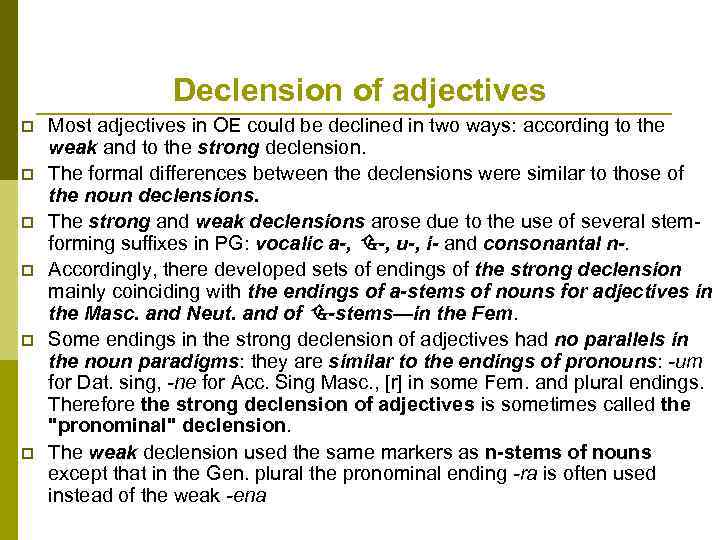

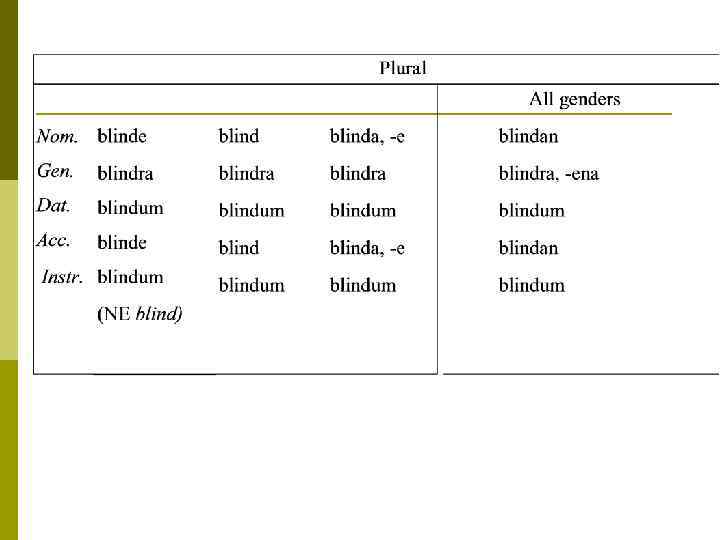

Declension of adjectives p p p Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between the declensions were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stemforming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, -, u-, i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a-stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of -stems—in the Fem. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives had no parallels in the noun paradigms: they are similar to the endings of pronouns: um for Dat. sing, ne for Acc. Sing Masc. , [r] in some Fem. and plural endings. Therefore the strong declension of adjectives is sometimes called the "pronominal" declension. The weak declension used the same markers as n-stems of nouns except that in the Gen. plural the pronominal ending ra is often used instead of the weak ena

p p The difference between the strong and the weak declension of adjectives was not only formal but also semantic. Unlike a noun, an adjective did not belong to a certain type of declension. Most adjectives could be declined in both ways. The choice of the declension was determined by a number of factors: the syntactical function of the adjective, the degree of comparison the presence of noun determiners. The adjective had a strong form when used predicatively and when used attributively without any determiners: e. g. : menn sindon de 'the men are good" mid hnescre beddin e 'with soft bedding'

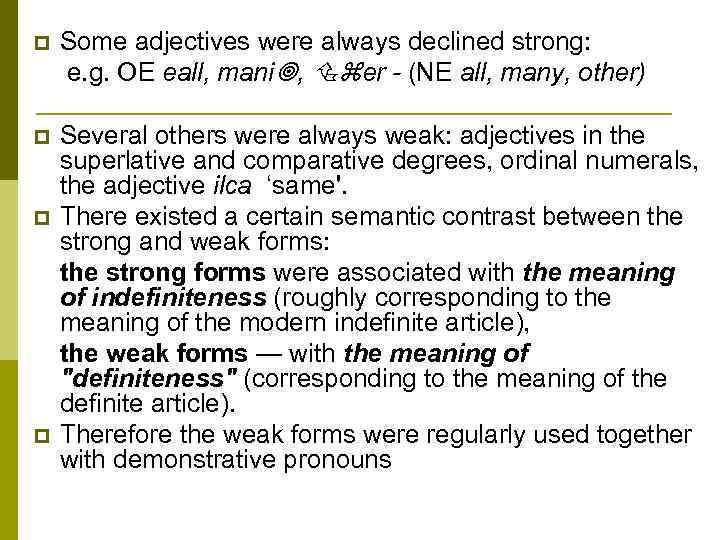

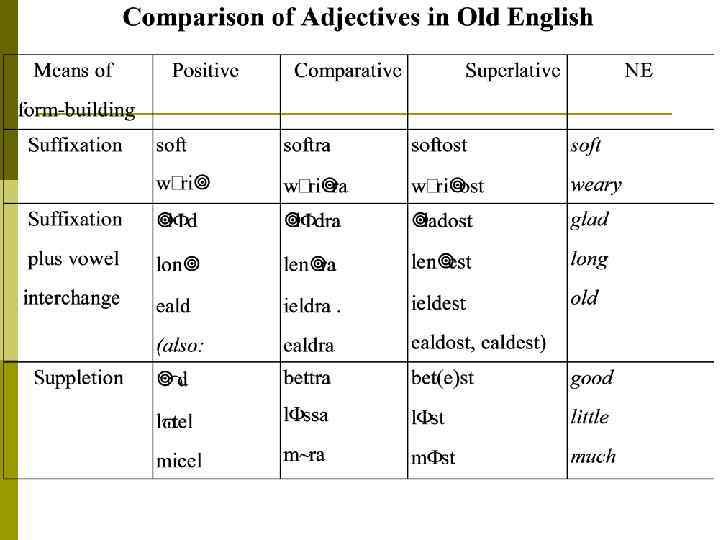

p Some adjectives were always declined strong: e. g. OE eall, mani , er (NE all, many, other) p Several others were always weak: adjectives in the superlative and comparative degrees, ordinal numerals, the adjective ilca ‘same'. There existed a certain semantic contrast between the strong and weak forms: the strong forms were associated with the meaning of indefiniteness (roughly corresponding to the meaning of the modern indefinite article), the weak forms — with the meaning of "definiteness" (corresponding to the meaning of the definite article). Therefore the weak forms were regularly used together with demonstrative pronouns p p

THE VERBAL SYSTEM p Grammatical categories of the finite verb p Grammatical categories of the verbals p Morphological classification of verbs

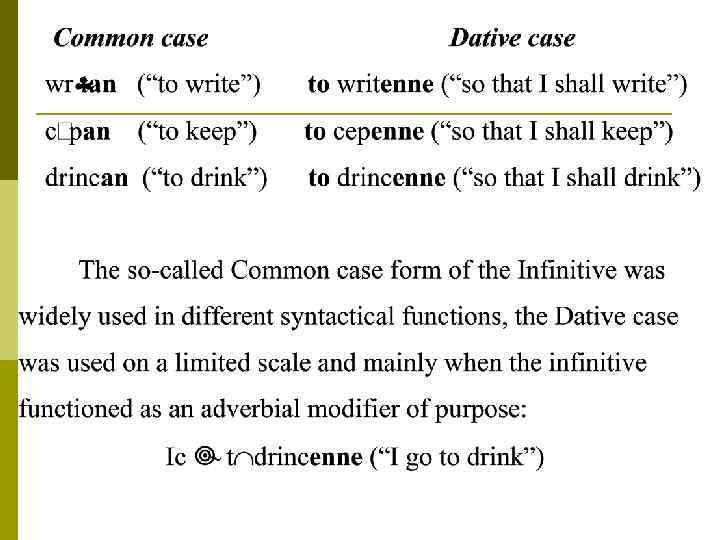

General characteristics of the verbal system p The two types of forms – the finite and the non-finite – differed more than they do today p The OE verbals were not conjugated like the verb proper, but were declined like nouns or adjectives. p The infinitive had two case-forms which may conventionally be called the “Common” case and the “Dative” case.

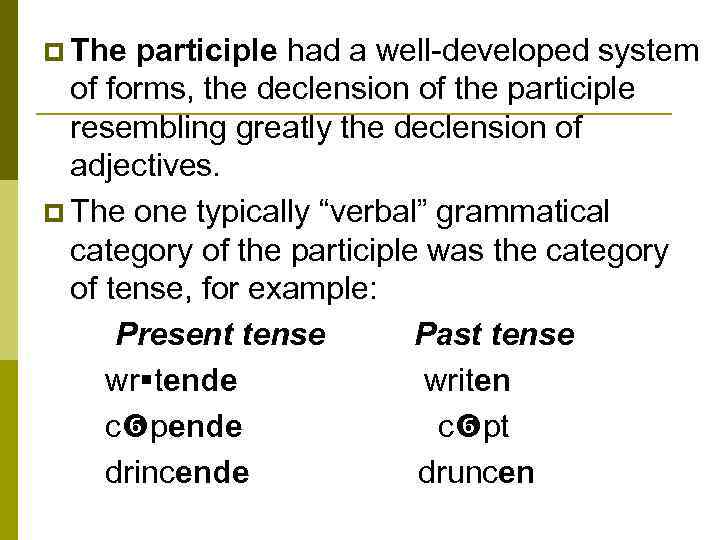

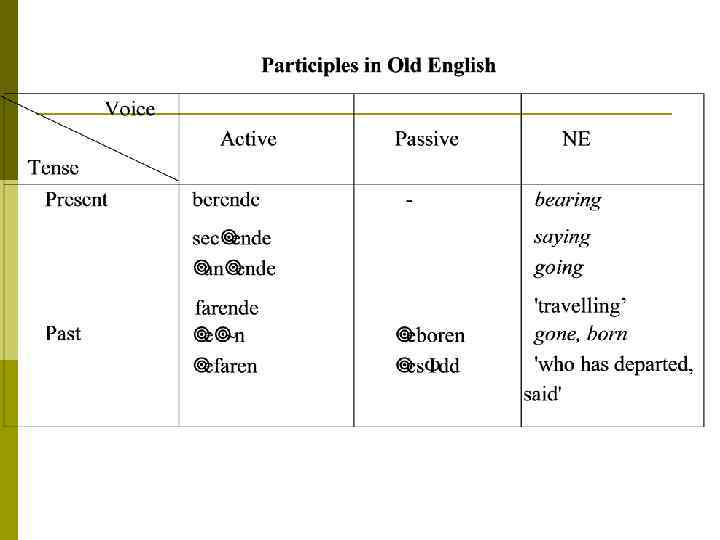

p The participle had a well-developed system of forms, the declension of the participle resembling greatly the declension of adjectives. p The one typically “verbal” grammatical category of the participle was the category of tense, for example: Present tense Past tense wr tende writen c pende c pt drincende druncen

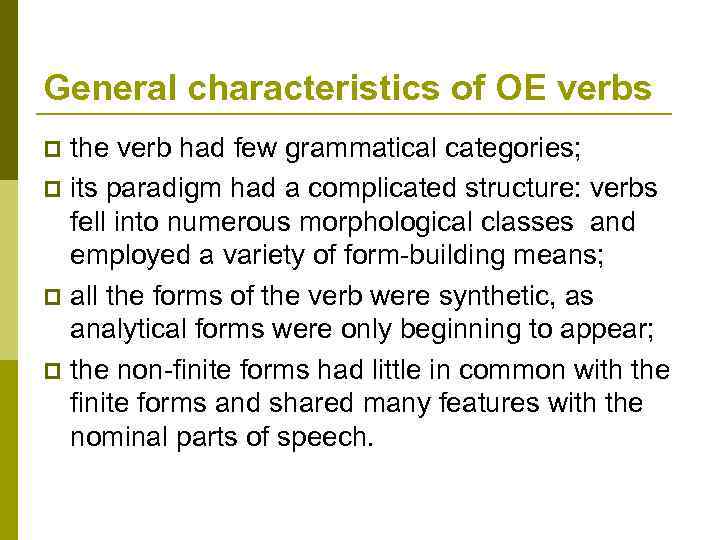

General characteristics of OE verbs the verb had few grammatical categories; p its paradigm had a complicated structure: verbs fell into numerous morphological classes and employed a variety of form-building means; p all the forms of the verb were synthetic, as analytical forms were only beginning to appear; p the non-finite forms had little in common with the finite forms and shared many features with the nominal parts of speech. p

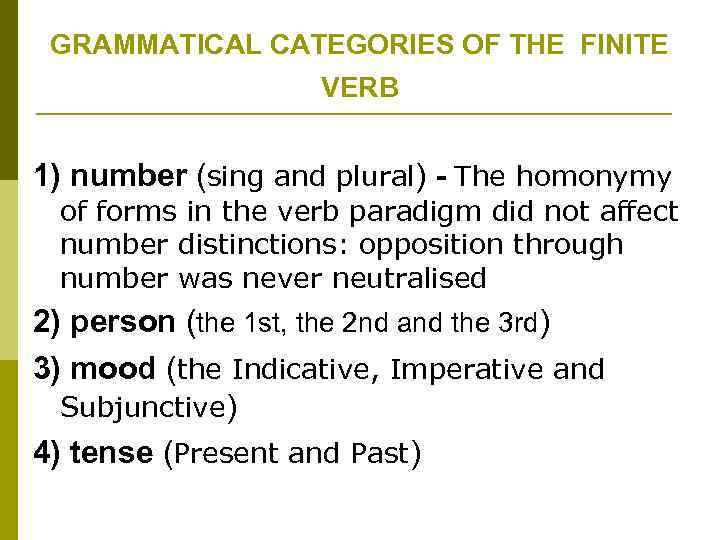

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORIES OF THE FINITE VERB 1) number (sing and plural) - The homonymy of forms in the verb paradigm did not affect number distinctions: opposition through number was never neutralised 2) person (the 1 st, the 2 nd and the 3 rd) 3) mood (the Indicative, Imperative and Subjunctive) 4) tense (Present and Past)

The category of person distinctions were neutralised in many positions. p person was consistently shown only in the Pres. Tense of the Ind. Mood sing. p in the Past Tense sing of the Ind. Mood the forms of the 1 st and 3 rd p. coincided and only the 2 nd p. had a distinct form. p person was not distinguished in the plural; nor was it shown in the Subj. Mood. p

The category of mood p p there were a few homonymous forms which eliminated the distinction between the moods: e. g. : Subj. did not differ from the Ind. in the 1 st p. sg Pres. Tense — bere, d me in the 1 st and 3 rd p. in the Past. The Imper. did not differ from the Ind. in the plural — l cia , d ma. The use of the Subj. Mood in OE was different from its use in later ages. Subj. forms conveyed a very general meaning of unreality or supposition. They were used in conditional sentences and other volitional, conjectural and hypothetical contexts. Subj. was common in clauses of time, clauses of result, clauses presenting reported speech.

The category of tense p p p The tenses were formally distinguished by all the verbs in the Ind. and Subj. Moods; there were no instances of neutralisation of the tense opposition; The meanings of the tense forms were very general, as compared with later ages and with present-day English; The forms of the Present were used to indicate: present and future actions, the meaning of futurity (with verbs of perfective meaning or with adverbs of future time); The Past tense was used to indicate: various events in the past (including those which are nowadays expressed by the forms of the Past Continuous, Past Perfect, Present Perfect and other analytical forms).

The category of aspect p p p Until recently it was believed that in OE — as well as in other OG languages — the category of aspect was expressed by the regular contrast of verbs with and without the prefix e. Verbs with the prefix had a perfective meaning while the same verbs without the prefix indicated a non-completed action: e. g. OE feohtan — efeohtan 'fight'— 'gain by fighting', l cian, — el cian 'like' — 'come to like' In some recent explorations it has been shown that the prefix e in OE can hardly be regarded as a marker of aspect. it could change the aspective meaning of the verb by making it perfective, but it could also change its lexical meaning: e. g. OE sittan— esittan 'sit'—'occupy', beran— eberan 'carry'-— 'bear a child'. It has also been noticed that verbs without a prefix could sometimes have a perfective meaning: si an Wi er yld l 'since Withergild fell', while verbs with e would indicate a non-completed repeated action: mani oft ecw 'many (people) often said'.

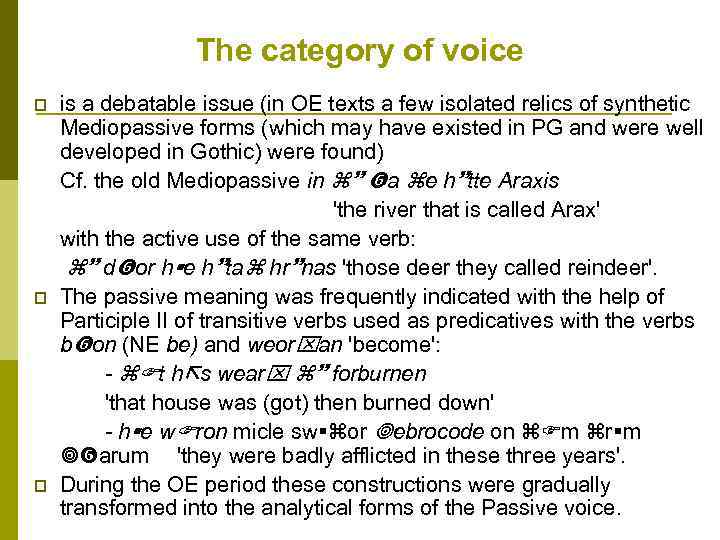

The category of voice p p p is a debatable issue (in OE texts a few isolated relics of synthetic Mediopassive forms (which may have existed in PG and were well developed in Gothic) were found) Cf. the old Mediopassive in a e h tte Araxis 'the river that is called Arax' with the active use of the same verb: d or h e h ta hr nas 'those deer they called reindeer'. The passive meaning was frequently indicated with the help of Participle II of transitive verbs used as predicatives with the verbs b on (NE be) and weor an 'become': t h s wear forburnen 'that house was (got) then burned down' h e w ron micle sw or ebrocode on m r m arum 'they were badly afflicted in these three years'. During the OE period these constructions were gradually transformed into the analytical forms of the Passive voice.

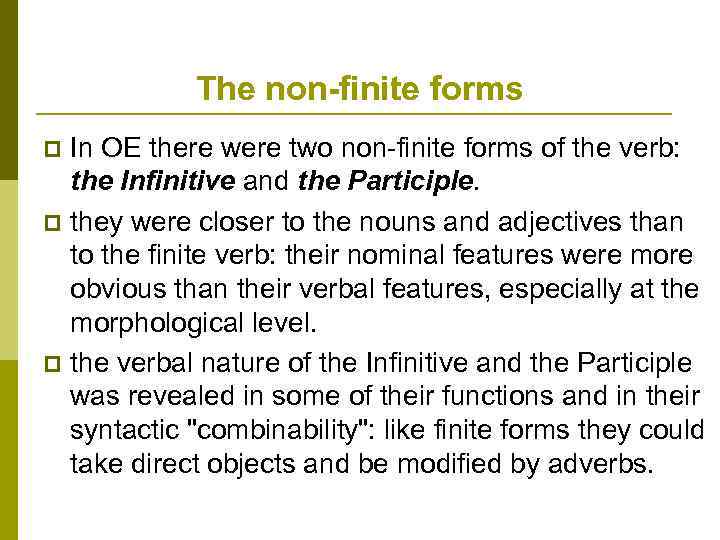

The non-finite forms In OE there were two non-finite forms of the verb: the Infinitive and the Participle. p they were closer to the nouns and adjectives than to the finite verb: their nominal features were more obvious than their verbal features, especially at the morphological level. p the verbal nature of the Infinitive and the Participle was revealed in some of their functions and in their syntactic "combinability": like finite forms they could take direct objects and be modified by adverbs. p

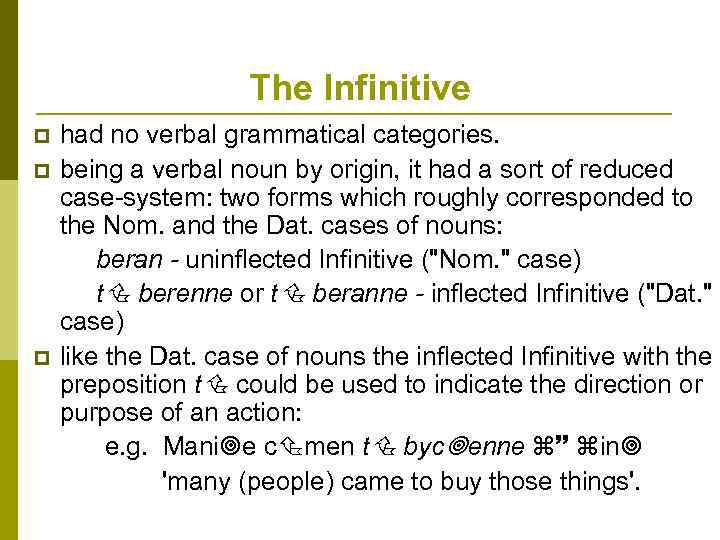

The Infinitive p p p had no verbal grammatical categories. being a verbal noun by origin, it had a sort of reduced case-system: two forms which roughly corresponded to the Nom. and the Dat. cases of nouns: beran uninflected Infinitive ("Nom. " case) t berenne or t beranne inflected Infinitive ("Dat. " case) like the Dat. case of nouns the inflected Infinitive with the preposition t could be used to indicate the direction or purpose of an action: e. g. Mani e c men t byc enne in 'many (people) came to buy those things'.

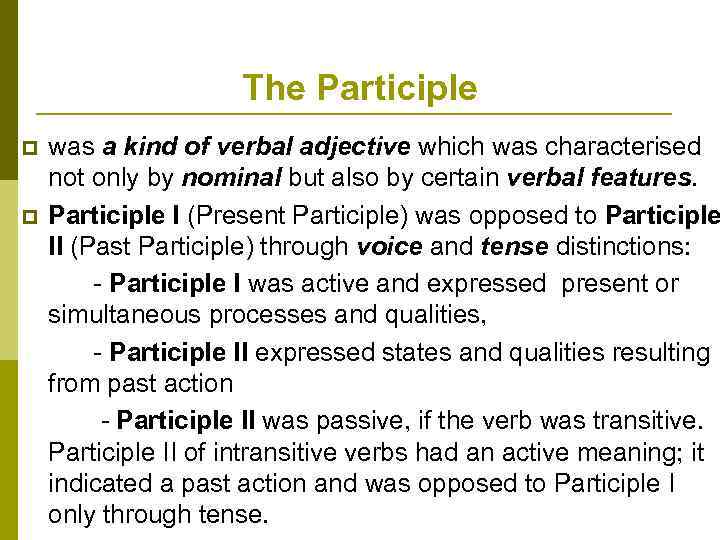

The Participle p p was a kind of verbal adjective which was characterised not only by nominal but also by certain verbal features. Participle I (Present Participle) was opposed to Participle II (Past Participle) through voice and tense distinctions: - Participle I was active and expressed present or simultaneous processes and qualities, - Participle II expressed states and qualities resulting from past action - Participle II was passive, if the verb was transitive. Participle II of intransitive verbs had an active meaning; it indicated a past action and was opposed to Participle I only through tense.

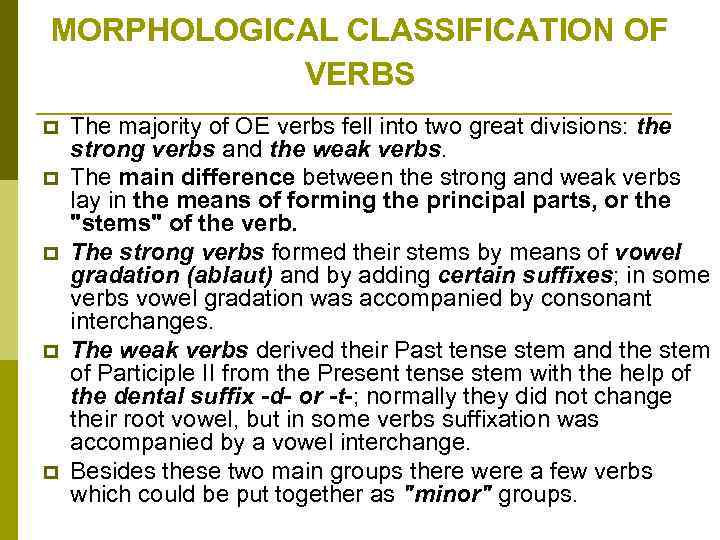

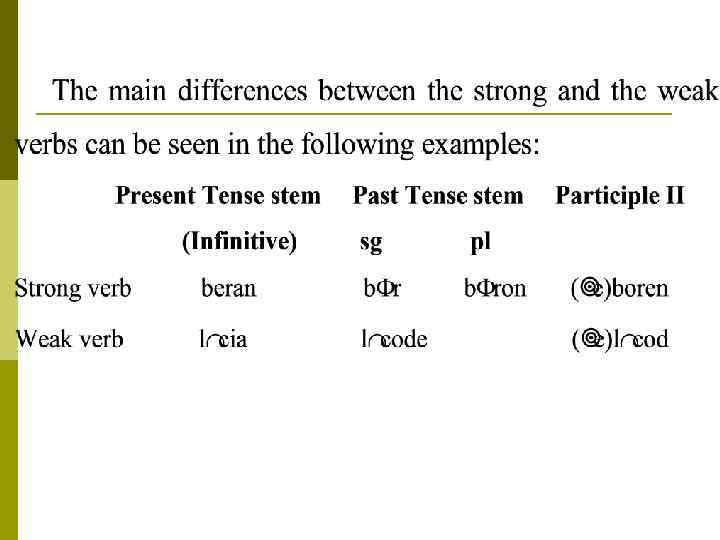

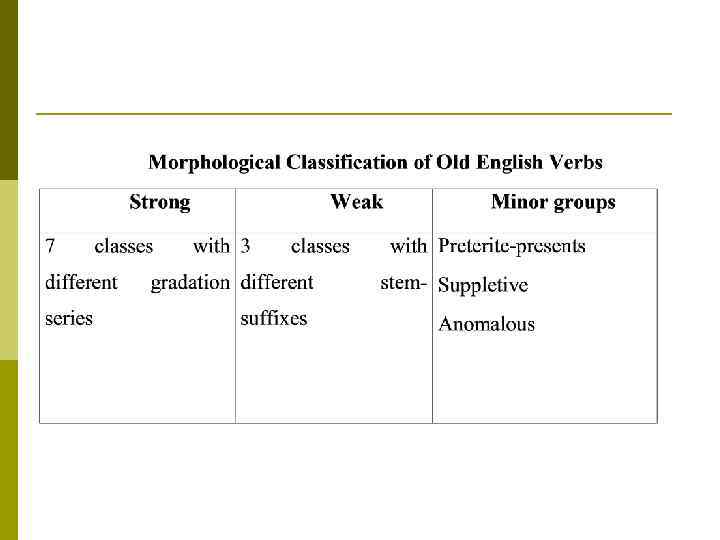

MORPHOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION OF VERBS p p p The majority of OE verbs fell into two great divisions: the strong verbs and the weak verbs. The main difference between the strong and weak verbs lay in the means of forming the principal parts, or the "stems" of the verb. The strong verbs formed their stems by means of vowel gradation (ablaut) and by adding certain suffixes; in some verbs vowel gradation was accompanied by consonant interchanges. The weak verbs derived their Past tense stem and the stem of Participle II from the Present tense stem with the help of the dental suffix -d- or -t-; normally they did not change their root vowel, but in some verbs suffixation was accompanied by a vowel interchange. Besides these two main groups there were a few verbs which could be put together as "minor" groups.

The number of weak verbs in OE exceeded that of strong verbs. p All the verbs, with the exception of the strong verbs and the minor groups (which make a total of about 315 -320 units) were weak. p The number of weak verbs was constantly growing since all new verbs derived from other stems were conjugated weak (except derivatives of strong verbs with prefixes). p Among the weak verbs there were many derivatives of OE noun and adjective stems and also derivatives of strong verbs built from one of their stems (usually the second stem — Past sing), e. g. OE talu n tellan v NE “tale, tell” OE full adj fyllan v NE “full, fill” OE findan, v str. fandian v NE “find, find out” (Past sing. fand) p

Minor groups of verbs p p can be referred neither to strong nor to weak verbs. “Preterite-presents" or "past-present" verbs. Originally the Present tense forms of these verbs were Past tense forms (or IE perfect forms, denoting past actions relevant for the present). Later these forms acquired a present meaning but preserved many formal features of the Past tense. Most of these verbs had new Past Tense forms built with the help of the dental suffix. Some of them also acquired the forms of the verbals: Participles and Infinitives. Most verbs did not have a full paradigm and were in this sense "defective".

p p Some verbs combined the features of weak and strong verbs: 1) OE d n formed a weak Past tense with a vowel interchange and a Participle in n: d n — dyde — e-d n (NE do). 2) OE b an 'live' had a weak Past b de and Participle II, ending in n, e-b n like a strong verb. Two OE verbs were suppletive: 1) OE n, whose Past tense was built from a different root: n - e de - e- n (NE “go”); 2) OE b on (NE “be”) is an ancient (IE) suppletive verb Though the Infinitive and Participle II do not occur in the texts, the set of forms can be reconstructed as: *wesan - w s - w : ron – weren.

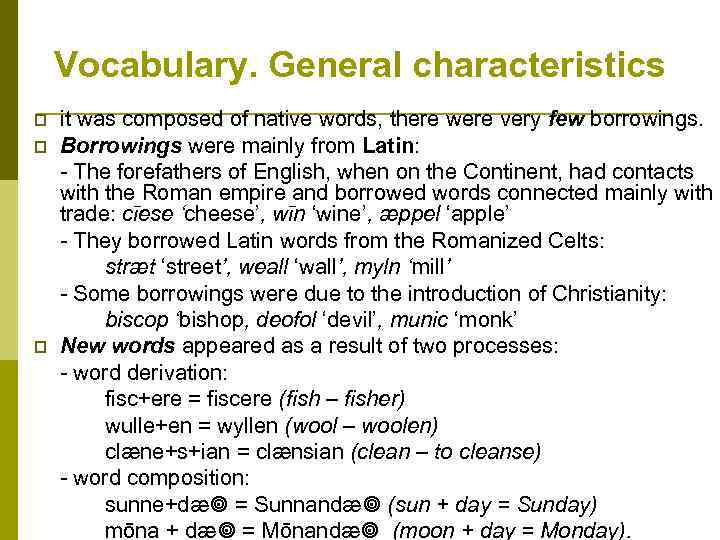

Vocabulary. General characteristics p p p it was composed of native words, there were very few borrowings. Borrowings were mainly from Latin: - The forefathers of English, when on the Continent, had contacts with the Roman empire and borrowed words connected mainly with trade: cīese ‘cheese’, wīn ‘wine’, æppel ‘apple’ - They borrowed Latin words from the Romanized Celts: stræt ‘street’, weall ‘wall’, myln ‘mill’ - Some borrowings were due to the introduction of Christianity: biscop ‘bishop, deofol ‘devil’, munic ‘monk’ New words appeared as a result of two processes: - word derivation: fisc+ere = fiscere (fish – fisher) wulle+en = wyllen (wool – woolen) clæne+s+ian = clænsian (clean – to cleanse) - word composition: sunne+dæ = Sunnandæ (sun + day = Sunday) mōna + dæ = Mōnandæ (moon + day = Monday).

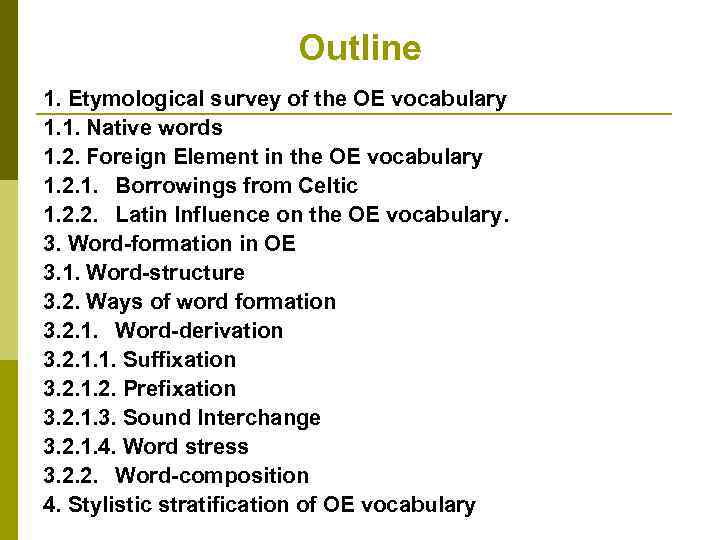

Outline 1. Etymological survey of the OE vocabulary 1. 1. Native words 1. 2. Foreign Element in the OE vocabulary 1. 2. 1. Borrowings from Celtic 1. 2. 2. Latin Influence on the OE vocabulary. 3. Word-formation in OE 3. 1. Word-structure 3. 2. Ways of word formation 3. 2. 1. Word-derivation 3. 2. 1. 1. Suffixation 3. 2. 1. 2. Prefixation 3. 2. 1. 3. Sound Interchange 3. 2. 1. 4. Word stress 3. 2. 2. Word-composition 4. Stylistic stratification of OE vocabulary

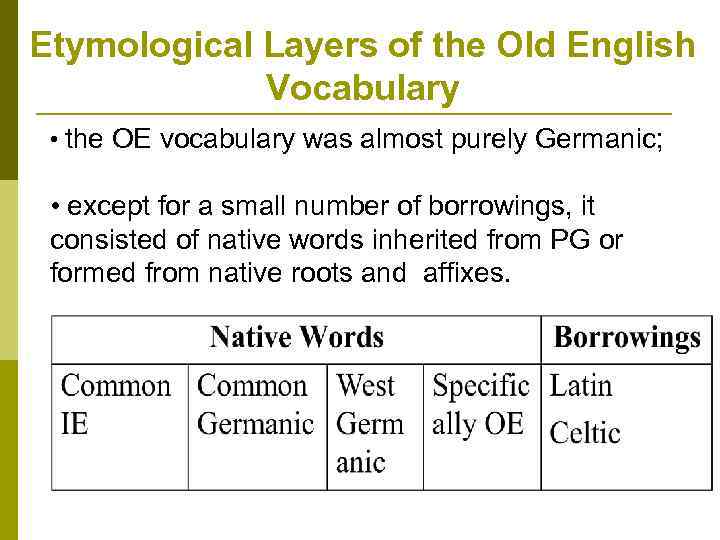

Etymological Layers of the Old English Vocabulary • the OE vocabulary was almost purely Germanic; • except for a small number of borrowings, it consisted of native words inherited from PG or formed from native roots and affixes.

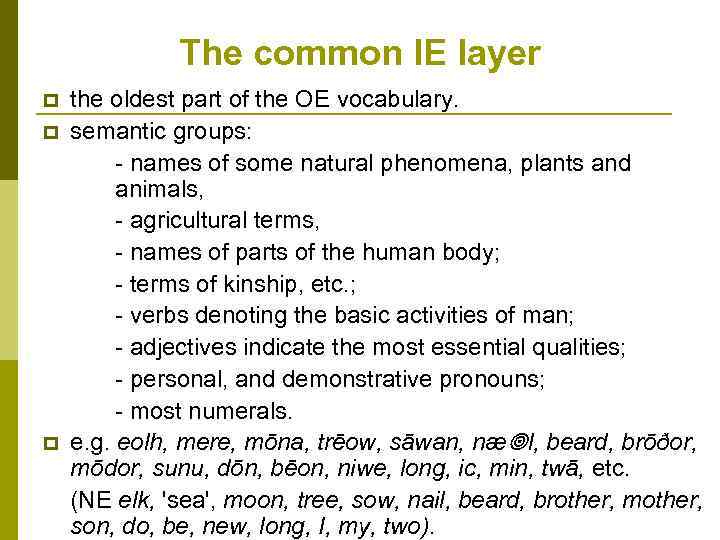

The common IE layer p p p the oldest part of the OE vocabulary. semantic groups: - names of some natural phenomena, plants and animals, - agricultural terms, - names of parts of the human body; - terms of kinship, etc. ; - verbs denoting the basic activities of man; - adjectives indicate the most essential qualities; - personal, and demonstrative pronouns; - most numerals. e. g. eolh, mere, mōna, trēow, sāwan, næ l, beard, brōðor, mōdor, sunu, dōn, bēon, niwe, long, ic, min, twā, etc. (NE elk, 'sea', moon, tree, sow, nail, beard, brother, mother, son, do, be, new, long, I, my, two).

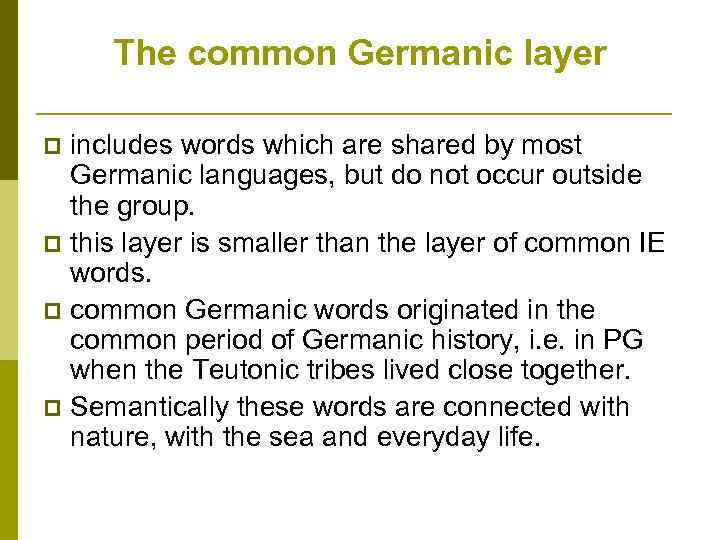

The common Germanic layer includes words which are shared by most Germanic languages, but do not occur outside the group. p this layer is smaller than the layer of common IE words. p common Germanic words originated in the common period of Germanic history, i. e. in PG when the Teutonic tribes lived close together. p Semantically these words are connected with nature, with the sea and everyday life. p

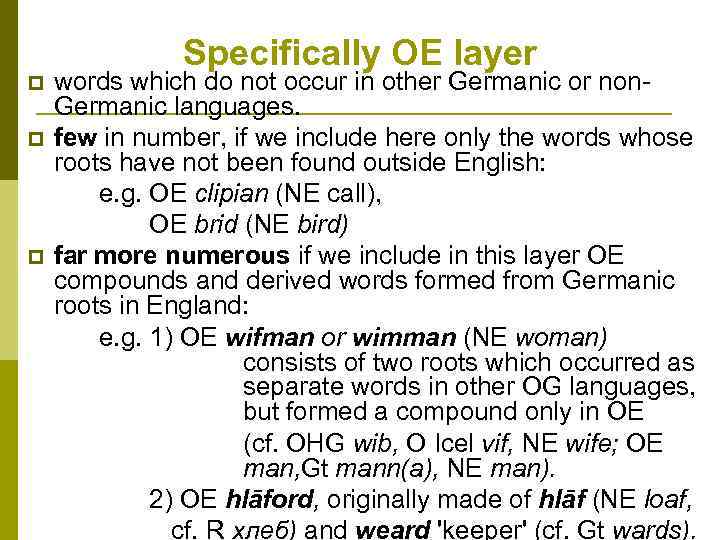

p p p Specifically OE layer words which do not occur in other Germanic or non. Germanic languages. few in number, if we include here only the words whose roots have not been found outside English: e. g. OE clipian (NE call), OE brid (NE bird) far more numerous if we include in this layer OE compounds and derived words formed from Germanic roots in England: e. g. 1) OE wifman or wimman (NE woman) consists of two roots which occurred as separate words in other OG languages, but formed a compound only in OE (cf. OHG wib, O Icel vif, NE wife; OE man, Gt mann(a), NE man). 2) OE hlāford, originally made of hlāf (NE loaf, cf. R xлeб) and weard 'keeper' (cf. Gt wards).

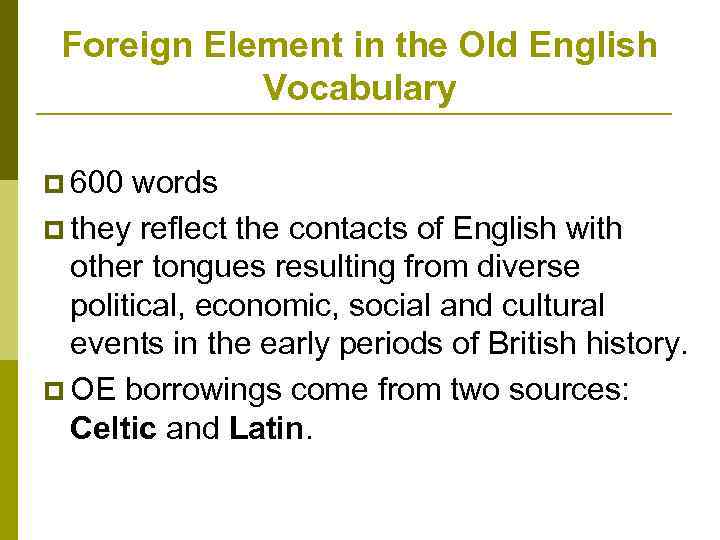

Foreign Element in the Old English Vocabulary p 600 words p they reflect the contacts of English with other tongues resulting from diverse political, economic, social and cultural events in the early periods of British history. p OE borrowings come from two sources: Celtic and Latin.

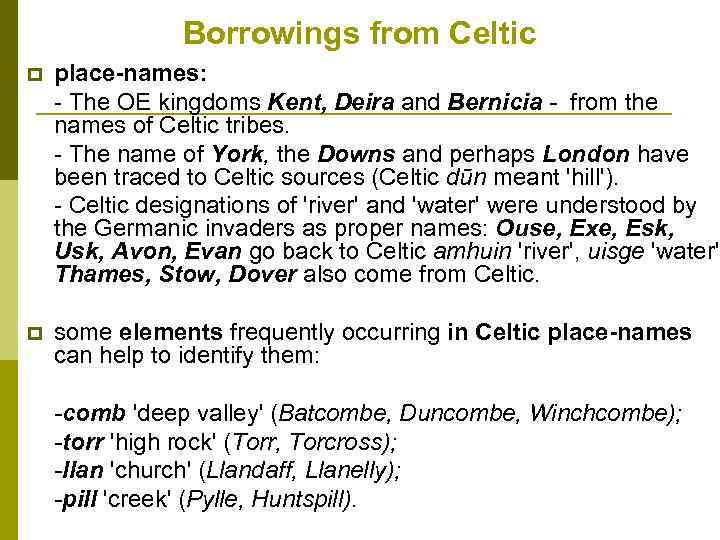

Borrowings from Celtic p place-names: - The OE kingdoms Kent, Deira and Bernicia from the names of Celtic tribes. - The name of York, the Downs and perhaps London have been traced to Celtic sources (Celtic dūn meant 'hill'). - Celtic designations of 'river' and 'water' were understood by the Germanic invaders as proper names: Ouse, Exe, Esk, Usk, Avon, Evan go back to Celtic amhuin 'river', uisge 'water'; Thames, Stow, Dover also come from Celtic. p some elements frequently occurring in Celtic place-names can help to identify them: comb 'deep valley' (Batcombe, Duncombe, Winchcombe); torr 'high rock' (Torr, Torcross); llan 'church' (Llandaff, Llanelly); pill 'creek' (Pylle, Huntspill).

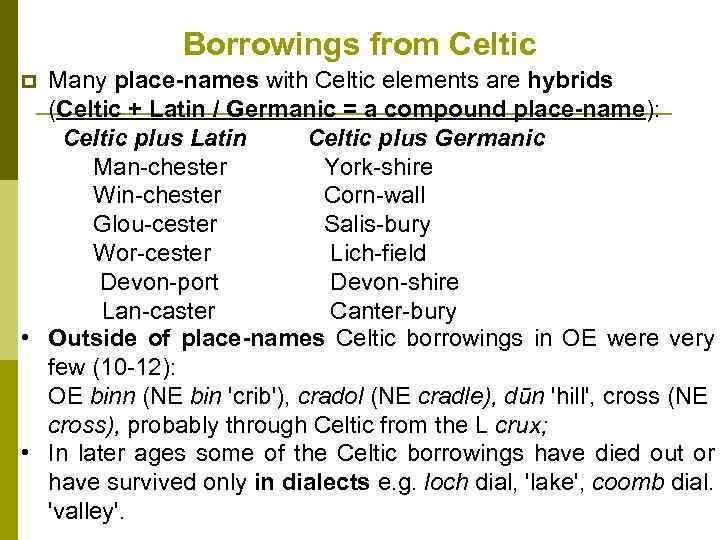

Borrowings from Celtic Many place-names with Celtic elements are hybrids (Celtic + Latin / Germanic = a compound place-name): Celtic plus Latin Celtic plus Germanic Man-chester York-shire Win-chester Corn-wall Glou-cester Salis-bury Wor-cester Lich-field Devon-port Devon-shire Lan-caster Canter-bury • Outside of place-names Celtic borrowings in OE were very few (10 -12): OE binn (NE bin 'crib'), cradol (NE cradle), dūn 'hill', cross (NE cross), probably through Celtic from the L crux; • In later ages some of the Celtic borrowings have died out or have survived only in dialects e. g. loch dial, 'lake', coomb dial. 'valley'. p

Latin Influence on the Old English Vocabulary p the Latin influence: the OE alphabet, the growth of writing and literature. p chronologically several layers

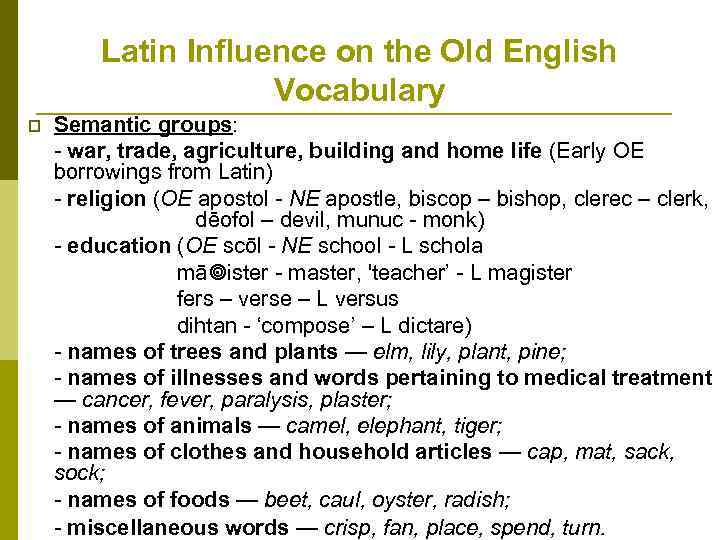

Latin Influence on the Old English Vocabulary p Semantic groups: - war, trade, agriculture, building and home life (Early OE borrowings from Latin) religion (OE apostol - NE apostle, biscop – bishop, clerec – clerk, dēofol – devil, munuc - monk) - education (OE scōl - NE school - L schola mā ister - master, 'teacher’ - L magister fers – verse – L versus dihtan - ‘compose’ – L dictare) - names of trees and plants — elm, lily, plant, pine; names of illnesses and words pertaining to medical treatment — cancer, fever, paralysis, plaster; names of animals — camel, elephant, tiger; names of clothes and household articles — cap, mat, sack, sock; names of foods — beet, caul, oyster, radish; miscellaneous words — crisp, fan, place, spend, turn.

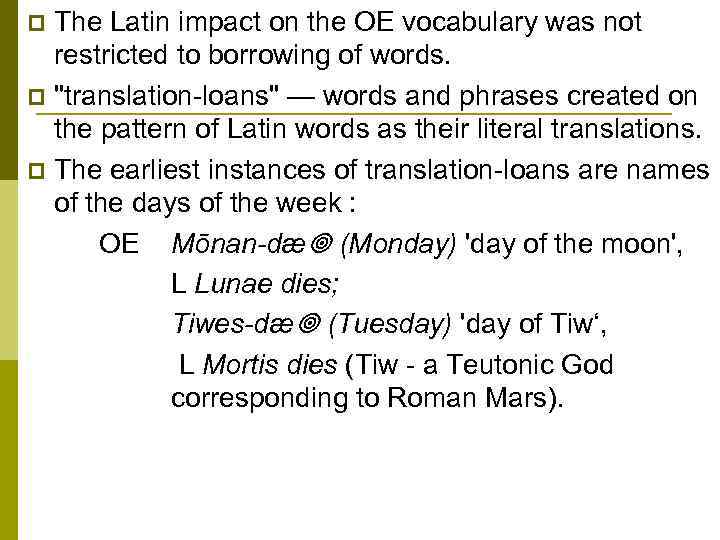

The Latin impact on the OE vocabulary was not restricted to borrowing of words. p "translation-loans" — words and phrases created on the pattern of Latin words as their literal translations. p The earliest instances of translation-loans are names of the days of the week : OE Mōnan dæ (Monday) 'day of the moon', L Lunae dies; Tiwes dæ (Tuesday) 'day of Tiw‘, L Mortis dies (Tiw - a Teutonic God corresponding to Roman Mars). p

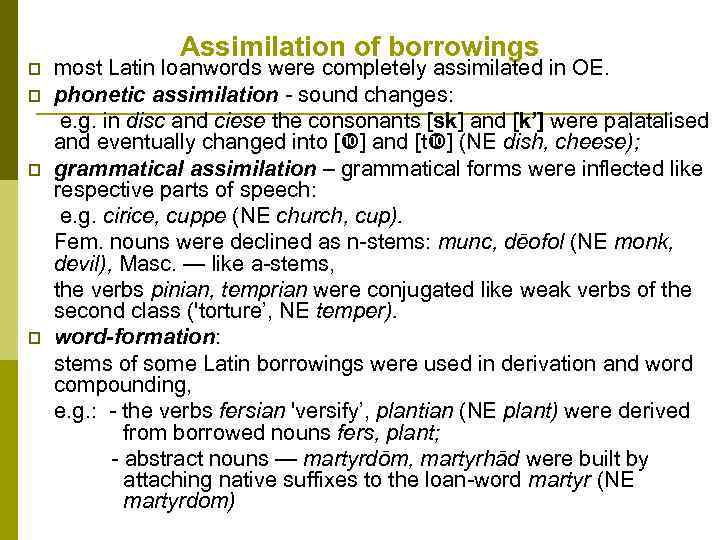

p p Assimilation of borrowings most Latin loanwords were completely assimilated in OE. phonetic assimilation - sound changes: e. g. in disc and ciese the consonants [sk] and [k’] were palatalised and eventually changed into [ ] and [t ] (NE dish, cheese); grammatical assimilation – grammatical forms were inflected like respective parts of speech: e. g. cirice, cuppe (NE church, cup). Fem. nouns were declined as n-stems: тиnc, dēofol (NE monk, devil), Masc. — like a-stems, the verbs pinian, temprian were conjugated like weak verbs of the second class ('torture’, NE temper). word-formation: stems of some Latin borrowings were used in derivation and word compounding, e. g. : - the verbs fersian 'versify’, plantian (NE plant) were derived from borrowed nouns fers, plant; abstract nouns — martyrdōm, martyrhād were built by attaching native suffixes to the loan-word martyr (NE martyrdom)

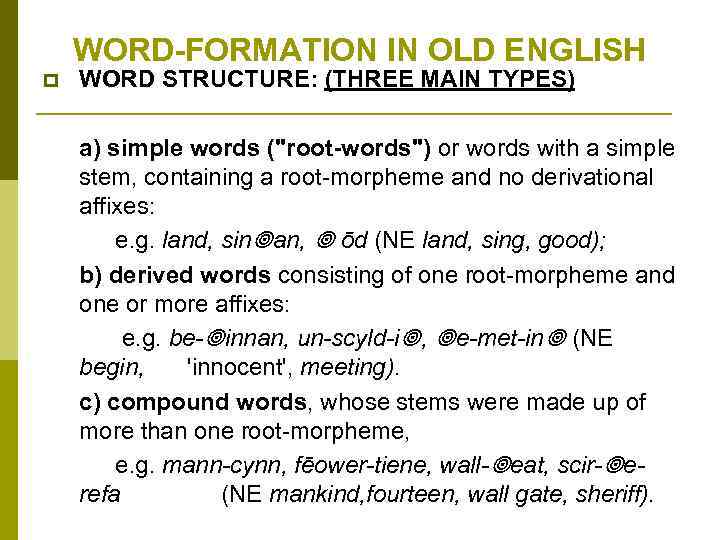

WORD-FORMATION IN OLD ENGLISH p WORD STRUCTURE: (THREE MAIN TYPES) a) simple words ("root-words") or words with a simple stem, containing a root-morpheme and no derivational affixes: e. g. land, sin an, ōd (NE land, sing, good); b) derived words consisting of one root-morpheme and one or more affixes: e. g. be innan, un scyld i , e met in (NE begin, 'innocent', meeting). c) compound words, whose stems were made up of more than one root-morpheme, e. g. mann cynn, fēower tiene, wall eat, scir e refa (NE mankind, fourteen, wall gate, sheriff).

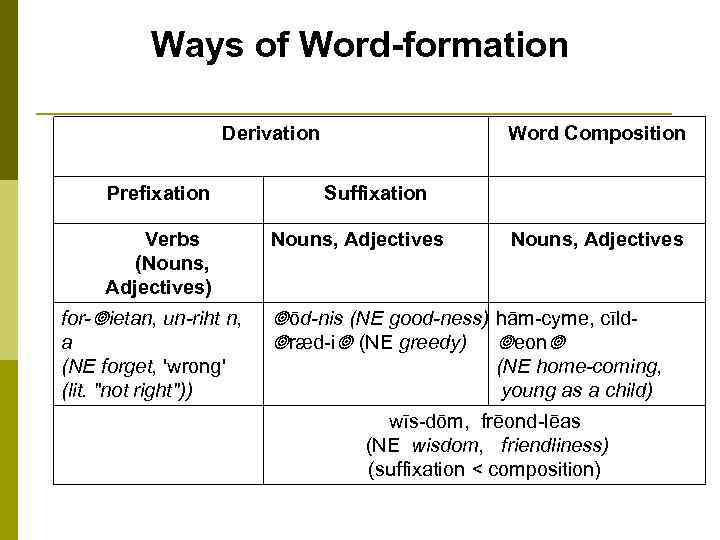

Ways of Word-formation Derivation Prefixation Verbs (Nouns, Adjectives) for ietan, un riht n, a (NE forget, 'wrong' (lit. "not right")) Word Composition Suffixation Nouns, Adjectives ōd nis (NE good ness) hām-cyme, cīld ræd-i (NE greedy) eon (NE home coming, young as a child) wīs-dōm, frēond-lēas (NE wisdom, friendliness) (suffixation < composition)

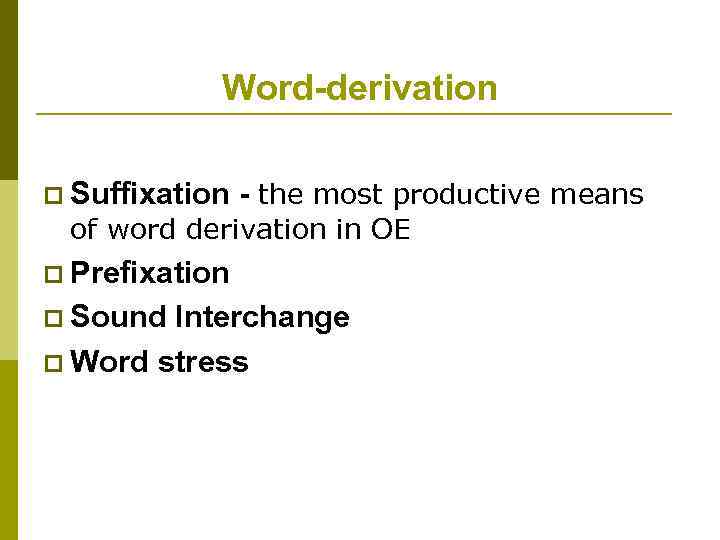

Word-derivation p Suffixation - the most productive means of word derivation in OE p Prefixation p Sound Interchange p Word stress

Suffixation p the most productive means of word derivation in OE; p old stem-suffixes - derivational suffixes proper inherited from PIE and PG - new suffixes; p substantive suffixes (-ere, -estre, -ende, -in , en, -nis, -nes, - , -u , -ō , -un , -in , -dom, -scipe); p adjective suffixes (-ede, -ihte, -i , -en, -isc, -sum, feald, -full, -leas, -līc, -weard); p verb suffixes (-s-, -l c-, -ett-)

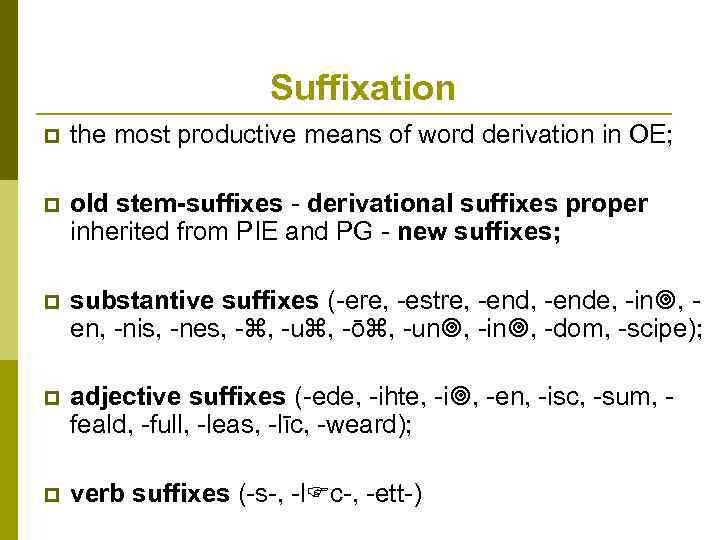

p p p PREFIXATION a productive way of building new words in OE. genetically, some OE prefixes go back to IE prototypes, e. g. OE -n-, a negative prefix (the element n is found in negative prefixes in many IE languages). many more prefixes sprang in PG and OE from prepositions and adverbs, e. g. mis , be , ofer. Prefixes were widely used with verbs but were far less productive with other parts of speech. ān—‘go’ faran —'travel' ā- ān—'go away' ā-faran — ‘travel’ be- ān —'go round' tō-faran —'disperse' fore- ān — 'precede' for-faran—'intercept' ofer- ān —'traverse' for -faran — 'die' e- ān —'go', 'go away' e-faran —'attack Prefixes: ā-, be-, mis-, of-, on-, to-, un-, wan-

![SOUND INTERCHANGES rīdan v — rād n [i: ~a: ] (like Class 1 of SOUND INTERCHANGES rīdan v — rād n [i: ~a: ] (like Class 1 of](https://present5.com/presentation/13222853_9666166/image-110.jpg)

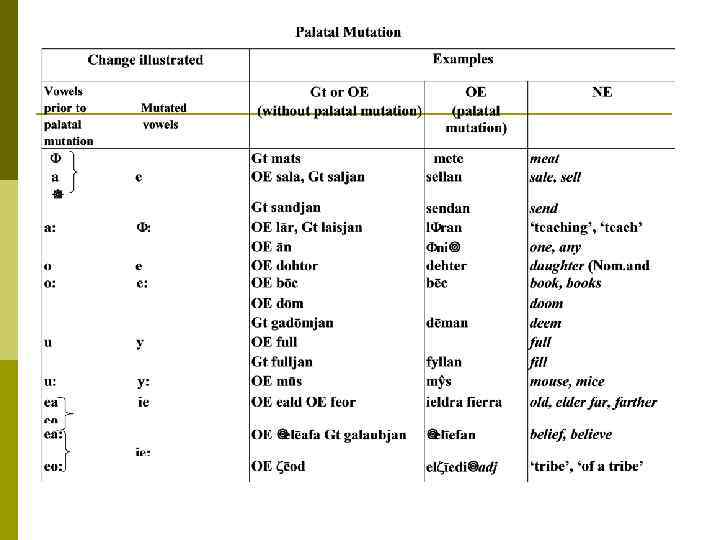

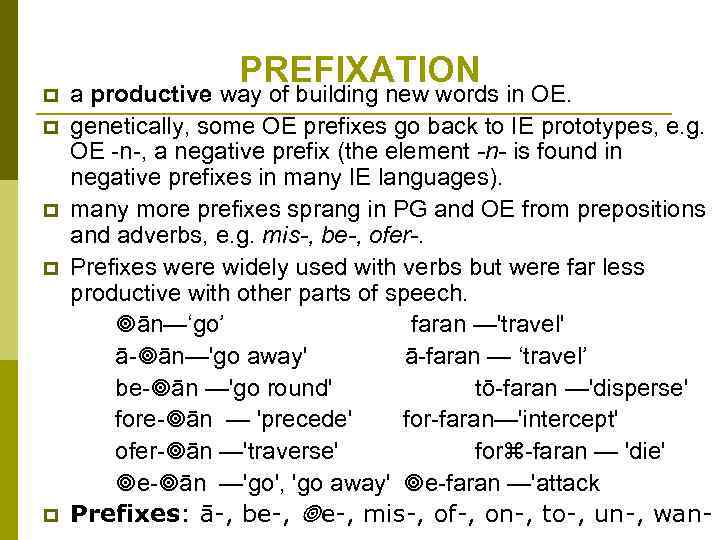

SOUND INTERCHANGES rīdan v — rād n [i: ~a: ] (like Class 1 of strong verbs), NE ride, raid sin an v — son n [i~a] (like Class 3 of strong verbs), NE sing, song sprecan v — spr ce n [e~ : ] (see Class 5 of strong verbs) beran v — b re n — the same; NE speak, speech, bearer. 2) findan — Past sg fand — fandian, NE find, 'find out' sittan — Past sg s t — settan, NE sit, set drincan — Past sg dranc — drencan, NE drink, drench. 1)

![SOUND INTERCHANGES 3) Many vowel interchanges arose due to palatal mutation; the element [i/j] SOUND INTERCHANGES 3) Many vowel interchanges arose due to palatal mutation; the element [i/j]](https://present5.com/presentation/13222853_9666166/image-111.jpg)

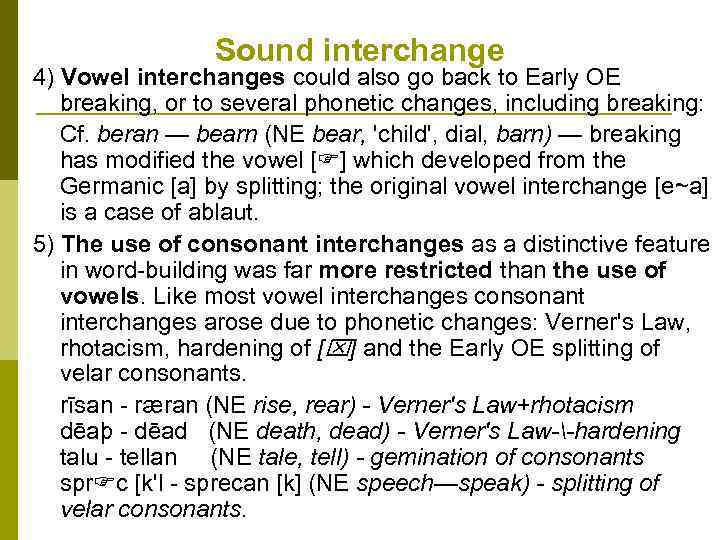

SOUND INTERCHANGES 3) Many vowel interchanges arose due to palatal mutation; the element [i/j] in the derivational suffix caused the mutation of the root-vowel; the same root without the suffix retained the original non-mutated vowel, e. g. : a) nouns and verbs: dōm — dēmon from the earlier *dōmjan (NE doom deem); fōd — fēdan (NE food — feed); bōt — bētan and also bettre ('remedy', 'improve', NE better); b) adjectives and verbs: full — fyllan (NE full — fill); hāl — hœlan ('healthy' — heal). c) nouns and adjectives: long — len u (NE long, length), stron — stren u (NE strong — strength); brād — brœd u (NE broad — breadth).

Sound interchange 4) Vowel interchanges could also go back to Early OE breaking, or to several phonetic changes, including breaking: Cf. beran — bearn (NE bear, 'child', dial, barn) — breaking has modified the vowel [ ] which developed from the Germanic [a] by splitting; the original vowel interchange [e~a] is a case of ablaut. 5) The use of consonant interchanges as a distinctive feature in word-building was far more restricted than the use of vowels. Like most vowel interchanges consonant interchanges arose due to phonetic changes: Verner's Law, rhotacism, hardening of [ ] and the Early OE splitting of velar consonants. rīsan - ræran (NE rise, rear) Verner's Law+rhotacism dēaþ - dēad (NE death, dead) Verner's Law hardening talu - tellan (NE tale, tell) gemination of consonants spr c [k'l - sprecan [k] (NE speech—speak) splitting of velar consonants.

Word Stress p the role of word accentuation in OE wordbuilding was not great; p the shifting of word stress helped to differentiate between some parts of speech; p the verb had unaccented prefixes while the corresponding nouns had stressed prefixes: e. g. ond 'swarian v — 'ond swaru n.

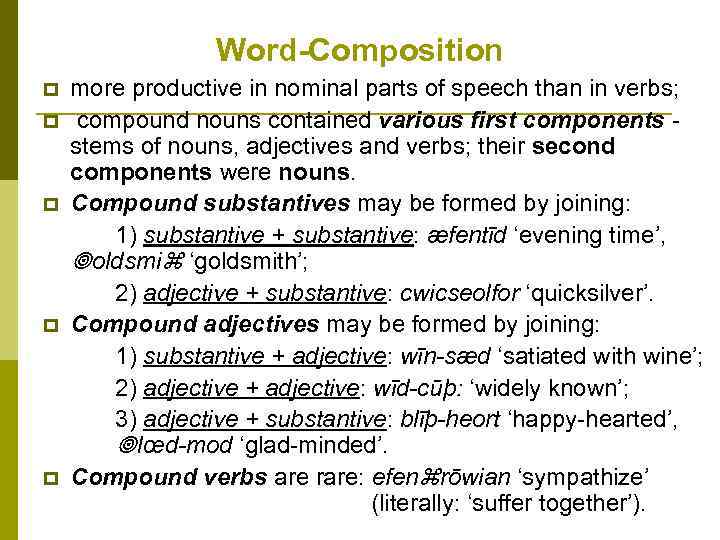

Word-Composition p p p more productive in nominal parts of speech than in verbs; compound nouns contained various first components stems of nouns, adjectives and verbs; their second components were nouns. Compound substantives may be formed by joining: 1) substantive + substantive: æfentīd ‘evening time’, oldsmi ‘goldsmith’; 2) adjective + substantive: cwicseolfor ‘quicksilver’. Compound adjectives may be formed by joining: 1) substantive + adjective: wīn sæd ‘satiated with wine’; 2) adjective + adjective: wīd cūþ: ‘widely known’; 3) adjective + substantive: blīþ heort ‘happy-hearted’, lœd mod ‘glad-minded’. Compound verbs are rare: efen rōwian ‘sympathize’ (literally: ‘suffer together’).

Stylistic Stratification of the Old English Vocabulary OE words are subdivided into three stylistically distinct groups: p p p neutral words, learned words, poetic words.

Neutral words are characterised by: - the highest frequency of occurrence, - wide use in word-formation - historical stability; p the majority of these words — often in altered shape— have been preserved to the present day. Most words of this group are of native origin: e. g. OE mann, stān, blind, drincan, bēon, etc. p

Learned words are found in texts of religious, legal, philosophical or scientific character. p there were many borrowings from Latin among learned words. p numerous compound nouns were built on Latin models as translation loans to render the exact meaning of foreign terms: e. g. : wrē endlic (L Accusativus), feor bold 'body' (L animœ domus 'dwelling of the soul'). p In later periods of history many OE learned words went out of use being replaced by new borrowings and native formations. p

Poetic words p p p OE poetry employs a very specific vocabulary. A cardinal characteristic of OE poetry is its wealth of synonyms. In BEOWULF there are 37 words for the concept "warrior", 12 - for "battle”, 17 - for “sea”. Among the poetic names for “hero” are beorn, rinc, sec , þe n and many metaphoric circumlocutions ("kennings") — compounds used instead of simple words: ār berend lit. "spear-carrier", ar wi a ‘spear-warrior', sweord freca 'sword-hero’, hyrn wi a 'corslet-warrior', ūþ ewinn ‘war contest', lind hxbbende 'having a shield', ūþ rinc 'man of war, warrior', pēod uma ‘man of the troop’, ūþ wine 'war-friend'.

Old English.ppt