Old English2.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 63

OLD ENGLISH GRAMMAR Lecture V

OLD ENGLISH GRAMMAR Lecture V

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION: 1. The Adjective 1. 1) Declension of adjectives 1. 2) Degrees of comparison 2. The Adverb 3. General survey of finite and non-finite forms of the verb 4. Grammatical categories of the finite forms of the verb

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION: 1. The Adjective 1. 1) Declension of adjectives 1. 2) Degrees of comparison 2. The Adverb 3. General survey of finite and non-finite forms of the verb 4. Grammatical categories of the finite forms of the verb

KEY WORDS v Modifier v Determiner v Adjectival adverbs v Decline v Indeclinable v Finite / non- finite forms of the verb v Conjugate v Indicative / Imperative / Oblique mood forms

KEY WORDS v Modifier v Determiner v Adjectival adverbs v Decline v Indeclinable v Finite / non- finite forms of the verb v Conjugate v Indicative / Imperative / Oblique mood forms

FURTHER READING Расторгуева, Т. А. История английского языка: учебник / Т. А. Расторгуева. – 2 -е изд. , стер. – М. : Астрель : АСТ, 2003. – 348 с. ; P. 105– 108 (the adjective); 108– 124 (the verb)

FURTHER READING Расторгуева, Т. А. История английского языка: учебник / Т. А. Расторгуева. – 2 -е изд. , стер. – М. : Астрель : АСТ, 2003. – 348 с. ; P. 105– 108 (the adjective); 108– 124 (the verb)

THE ADJECTIVE The category ‘adjective’ was in Proto-Indo-European closely linked with that of the noun: adjectives were distinguished from nouns through their functions as qualitative modifiers. OE adjectives share many features of their morphology with nouns. The paradigm of the OE adjective distinguishes case, number and gender

THE ADJECTIVE The category ‘adjective’ was in Proto-Indo-European closely linked with that of the noun: adjectives were distinguished from nouns through their functions as qualitative modifiers. OE adjectives share many features of their morphology with nouns. The paradigm of the OE adjective distinguishes case, number and gender

1. 2 DECLENSION OF ADJECTIVES v The adjective is selected to agree with the case, number and gender of the noun this adjective modifies. In common with other Germanic languages, adjectives in OE have two distinct paradigms, strong and weak. Weak adjectives appear after determiners; strong adjectives appear elsewhere. v The grammatical category of case was built up by five forms: the Nominative, the Accusative, the Dative, the Genitive and the Instrumental.

1. 2 DECLENSION OF ADJECTIVES v The adjective is selected to agree with the case, number and gender of the noun this adjective modifies. In common with other Germanic languages, adjectives in OE have two distinct paradigms, strong and weak. Weak adjectives appear after determiners; strong adjectives appear elsewhere. v The grammatical category of case was built up by five forms: the Nominative, the Accusative, the Dative, the Genitive and the Instrumental.

Two paradigms for the adjective gōd ‘good’

Two paradigms for the adjective gōd ‘good’

WEAK SINGULAR Masculine Feminine Neuter Nominative gōda ‘good’ gōde Genitive gōdan Accusative gōdan gōde Dative gōdan

WEAK SINGULAR Masculine Feminine Neuter Nominative gōda ‘good’ gōde Genitive gōdan Accusative gōdan gōde Dative gōdan

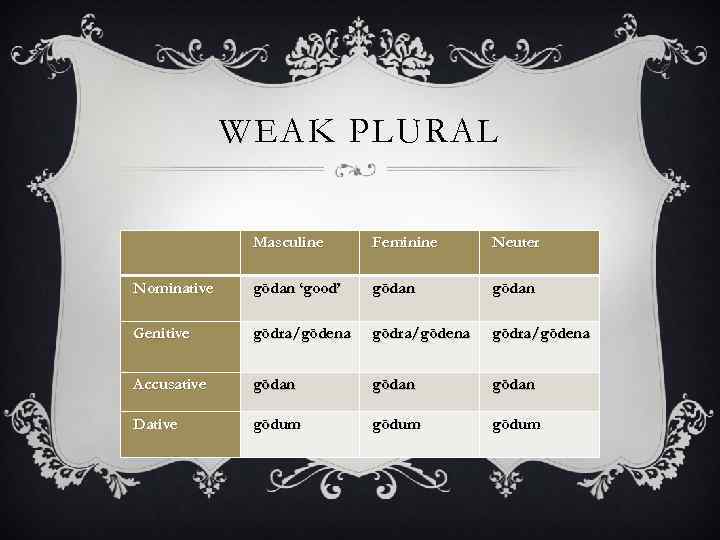

WEAK PLURAL Masculine Feminine Neuter Nominative gōdan ‘good’ gōdan Genitive gōdra/gōdena Accusative gōdan Dative gōdum

WEAK PLURAL Masculine Feminine Neuter Nominative gōdan ‘good’ gōdan Genitive gōdra/gōdena Accusative gōdan Dative gōdum

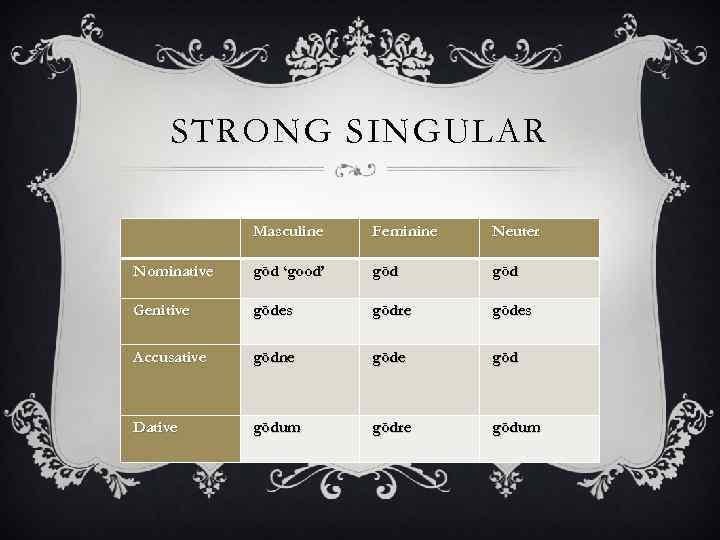

STRONG SINGULAR Masculine Feminine Neuter Nominative gōd ‘good’ gōd Genitive gōdes gōdre gōdes Accusative gōdne gōd Dative gōdum gōdre gōdum

STRONG SINGULAR Masculine Feminine Neuter Nominative gōd ‘good’ gōd Genitive gōdes gōdre gōdes Accusative gōdne gōd Dative gōdum gōdre gōdum

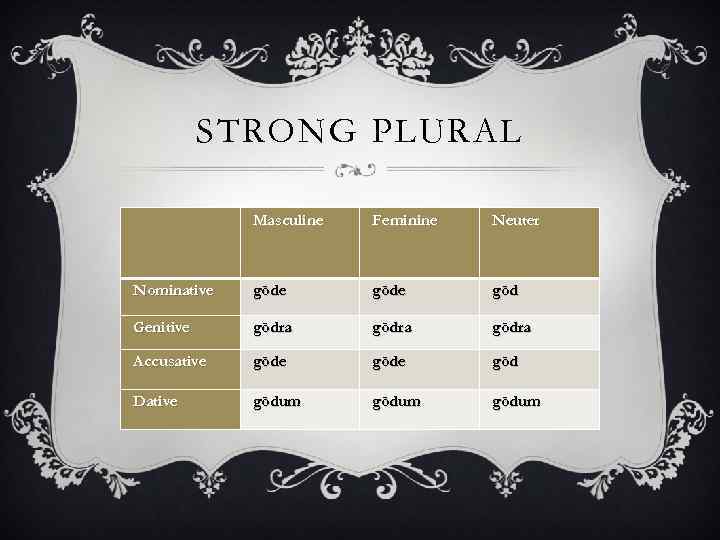

STRONG PLURAL Masculine Feminine Neuter Nominative gōde gōd Genitive gōdra Accusative gōde gōd Dative gōdum

STRONG PLURAL Masculine Feminine Neuter Nominative gōde gōd Genitive gōdra Accusative gōde gōd Dative gōdum

A few adjectives in OE are indeclinable, e. g. fela‘many’, which simply causes the noun it modifies to appear in the genitive case

A few adjectives in OE are indeclinable, e. g. fela‘many’, which simply causes the noun it modifies to appear in the genitive case

DEGREES OF COMPARISON The adjective in OE could express degrees of comparison. The degrees of comparison were built the same as all other grammatical notions – synthetically:

DEGREES OF COMPARISON The adjective in OE could express degrees of comparison. The degrees of comparison were built the same as all other grammatical notions – synthetically:

a) by means of suffixation. The ending was added to the stem of the lexeme: -ra for comparative, -ostfor superlative: v heardra— heardost — ‘hard’ v lēof‘dear’, lēofra ‘dearer’, lēofost ‘dearest’

a) by means of suffixation. The ending was added to the stem of the lexeme: -ra for comparative, -ostfor superlative: v heardra— heardost — ‘hard’ v lēof‘dear’, lēofra ‘dearer’, lēofost ‘dearest’

b) by means of vowel gradation plus suffixation: veald— ieldra— ieldest ‘old’

b) by means of vowel gradation plus suffixation: veald— ieldra— ieldest ‘old’

c) by means of suppletive forms vgōd bettra— betst — ‘good’

c) by means of suppletive forms vgōd bettra— betst — ‘good’

Both suffixation and the use of suppletive forms in the formation of the degrees of comparison are original means that can be traced back to Common Germanic. But the use of vowel interchange is a feature which is typical of English only and was acquired by the language in the prehistoric period of its development. The origin of vowel gradation in the forms is a result of the process of palatal mutation

Both suffixation and the use of suppletive forms in the formation of the degrees of comparison are original means that can be traced back to Common Germanic. But the use of vowel interchange is a feature which is typical of English only and was acquired by the language in the prehistoric period of its development. The origin of vowel gradation in the forms is a result of the process of palatal mutation

ADVERB Many OE adverbs are related to adjectives and were formed from them by the addition of suffixes. The most typical ending is -e, ex. : hearde ‘harshly’ ← the adjective heard ‘harsh, hard’

ADVERB Many OE adverbs are related to adjectives and were formed from them by the addition of suffixes. The most typical ending is -e, ex. : hearde ‘harshly’ ← the adjective heard ‘harsh, hard’

Many adjectives were themselves derived from nouns through the addition of the ending -lic And adverbs were. formed from these adjectives through the addition of -e, e. g. craeftlice ‘skilfully’. This process became so common that the ending -licewas extended to other words by analogy, heardlice ‘harshly’ alongside hearde

Many adjectives were themselves derived from nouns through the addition of the ending -lic And adverbs were. formed from these adjectives through the addition of -e, e. g. craeftlice ‘skilfully’. This process became so common that the ending -licewas extended to other words by analogy, heardlice ‘harshly’ alongside hearde

Adjectival adverbs in OE are indeclinable but have the degree of comparison. Comparative and superlative adverbs in OE were formed by the addition of the endings -or, -ost: v hearde – heardor ‘more harshly’ – heardost ‘most harshly’ Alongside: v heardlice heardlicor heardlicost – –

Adjectival adverbs in OE are indeclinable but have the degree of comparison. Comparative and superlative adverbs in OE were formed by the addition of the endings -or, -ost: v hearde – heardor ‘more harshly’ – heardost ‘most harshly’ Alongside: v heardlice heardlicor heardlicost – –

GENERAL SURVEY OF FINITE AND NON-FINITE FORMS OF THE VERB The verb-system in OE was represented by two sets of forms: the finite forms of the verb and the non-finite forms of the verb, or verbals (Infinitive, Participle). Those two types of forms — the finite and the non-finite — differed more than they do today from the point of view of their respective grammatical categories

GENERAL SURVEY OF FINITE AND NON-FINITE FORMS OF THE VERB The verb-system in OE was represented by two sets of forms: the finite forms of the verb and the non-finite forms of the verb, or verbals (Infinitive, Participle). Those two types of forms — the finite and the non-finite — differed more than they do today from the point of view of their respective grammatical categories

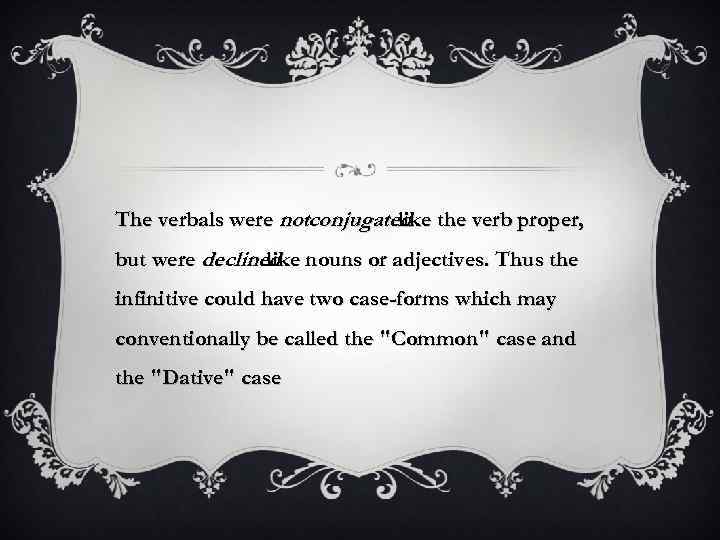

The verbals were notconjugated the verb proper, like but were declined nouns or adjectives. Thus the like infinitive could have two case-forms which may conventionally be called the "Common" case and the "Dative" case

The verbals were notconjugated the verb proper, like but were declined nouns or adjectives. Thus the like infinitive could have two case-forms which may conventionally be called the "Common" case and the "Dative" case

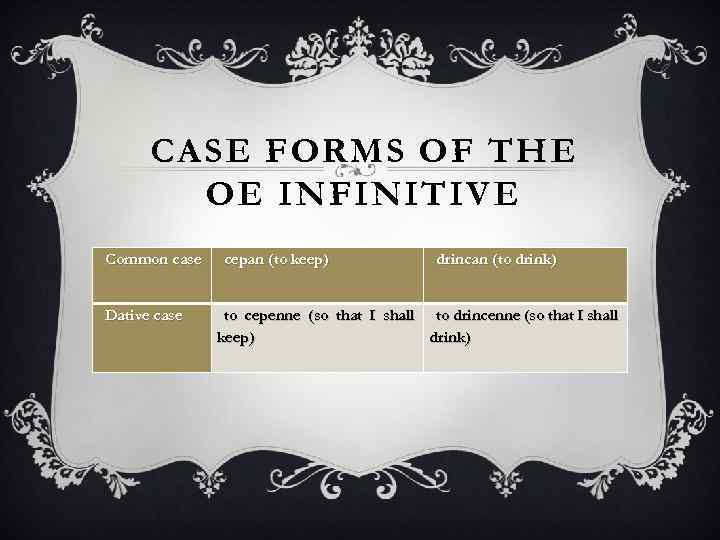

CASE FORMS OF THE OE INFINITIVE Common case Dative case cepan (to keep) drincan (to drink) to cepenne (so that I shall to drincenne (so that I shall keep) drink)

CASE FORMS OF THE OE INFINITIVE Common case Dative case cepan (to keep) drincan (to drink) to cepenne (so that I shall to drincenne (so that I shall keep) drink)

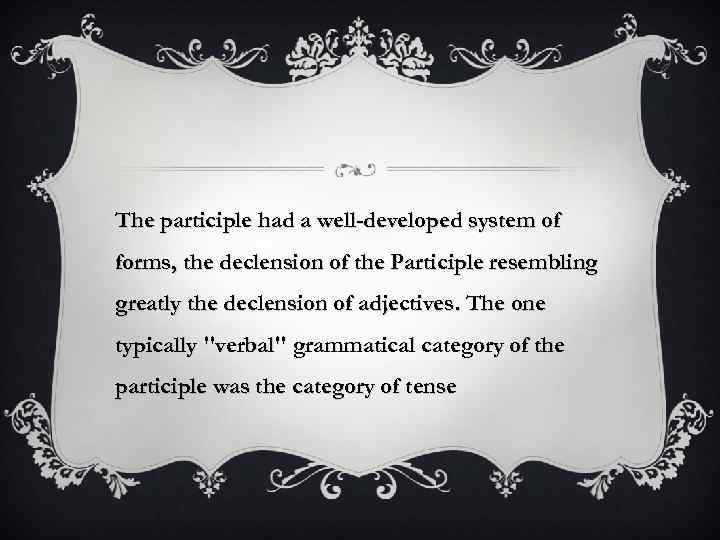

The participle had a well-developed system of forms, the declension of the Participle resembling greatly the declension of adjectives. The one typically "verbal" grammatical category of the participle was the category of tense

The participle had a well-developed system of forms, the declension of the Participle resembling greatly the declension of adjectives. The one typically "verbal" grammatical category of the participle was the category of tense

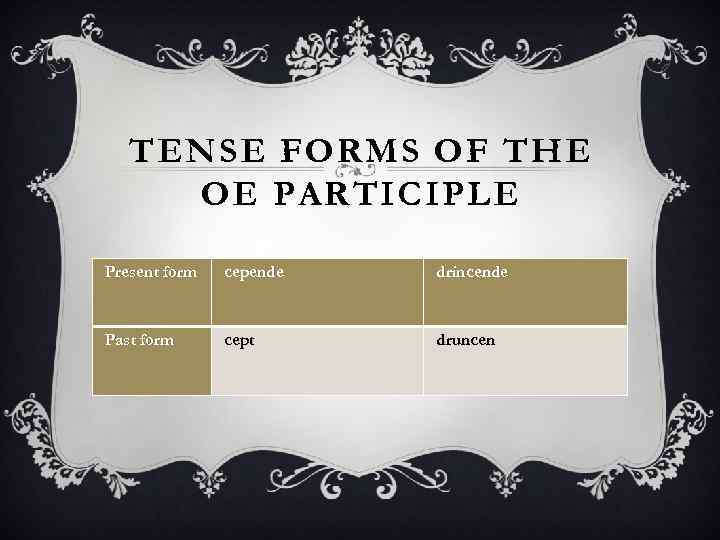

TENSE FORMS OF THE OE PARTICIPLE Present form cepende drincende Past form cept druncen

TENSE FORMS OF THE OE PARTICIPLE Present form cepende drincende Past form cept druncen

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORIES OF THE FINITE FORMS OF THE VERB The system of conjugation of the OE verb was built up by four grammatical categories: v person v number v tense v mood

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORIES OF THE FINITE FORMS OF THE VERB The system of conjugation of the OE verb was built up by four grammatical categories: v person v number v tense v mood

PERSON There were three person forms in OE: first, second and third. But distinct person forms existed only in the Indicative mood. The Imperative and the Oblique mood forms reflected no person differences and even the Indicative mood forms changed for person only in the Singular, the plural forms were the same irrespective of person

PERSON There were three person forms in OE: first, second and third. But distinct person forms existed only in the Indicative mood. The Imperative and the Oblique mood forms reflected no person differences and even the Indicative mood forms changed for person only in the Singular, the plural forms were the same irrespective of person

NUMBER The grammatical category of number was built up by the opposition of two number forms — Singular and Plural

NUMBER The grammatical category of number was built up by the opposition of two number forms — Singular and Plural

TENSE The grammatical category of tense was represented by two forms: Present tense and Past tense. There was no Future tense in OE. Future events were expressed: v with the help of a present tense verb + an advert denoting futurity; v by a combination of a modal verb (generally sculan ‘shall’ or willan‘will’ + an infinitive)

TENSE The grammatical category of tense was represented by two forms: Present tense and Past tense. There was no Future tense in OE. Future events were expressed: v with the help of a present tense verb + an advert denoting futurity; v by a combination of a modal verb (generally sculan ‘shall’ or willan‘will’ + an infinitive)

MOOD There were three mood forms in OE: Indicative, Imperative and Oblique Indicative þu cepst Imperative þu сер Oblique þu сере

MOOD There were three mood forms in OE: Indicative, Imperative and Oblique Indicative þu cepst Imperative þu сер Oblique þu сере

The Indicative Mood and the Imperative Mood were used in cases similar to those in which they are used now. But the Oblique mood in OE differed greatly from the corresponding mood in Modern English: v There was only one mood form in Old English that was used both to express events that are thought of as unreal or as problematic — today there are two mood forms to denote those two different kinds of events, conventionally called the Subjunctive and the Conjunctive. v The forms of the Oblique Mood were also sometimes used in contexts for which now the Indicative mood would be more suitable — to present events in the so-called “Indirect speech”

The Indicative Mood and the Imperative Mood were used in cases similar to those in which they are used now. But the Oblique mood in OE differed greatly from the corresponding mood in Modern English: v There was only one mood form in Old English that was used both to express events that are thought of as unreal or as problematic — today there are two mood forms to denote those two different kinds of events, conventionally called the Subjunctive and the Conjunctive. v The forms of the Oblique Mood were also sometimes used in contexts for which now the Indicative mood would be more suitable — to present events in the so-called “Indirect speech”

In Old English, as in other Germanic languages, we also see the beginnings a new tense system using auxiliaries, and especially the of development of forms for the perfect and for the passive, like Modern English I have helped I am helped perfect tenses existed in Old and. The English, but were not used as frequently or as consistently as they were later. The perfect tenses of transitive verbs (that is, those that take a direct object) were formed by the use of the verb habban have’ and the ‘to past participle of the verb. Originally, sentences like ‘He had broken a leg’ meant something like ‘He possessed a broken leg’

In Old English, as in other Germanic languages, we also see the beginnings a new tense system using auxiliaries, and especially the of development of forms for the perfect and for the passive, like Modern English I have helped I am helped perfect tenses existed in Old and. The English, but were not used as frequently or as consistently as they were later. The perfect tenses of transitive verbs (that is, those that take a direct object) were formed by the use of the verb habban have’ and the ‘to past participle of the verb. Originally, sentences like ‘He had broken a leg’ meant something like ‘He possessed a broken leg’

The passive was formed with the verbs ‘to be’ or ‘to become’ and the past participle. In Old English, the passive could only be formed with verbs that took an object in the accusative case

The passive was formed with the verbs ‘to be’ or ‘to become’ and the past participle. In Old English, the passive could only be formed with verbs that took an object in the accusative case

MORPHOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION OF VERBS All OE verbs may be subdivided into a number of groups in accordance with the grammatical means with the help of which they built their principal stems. There were two principal means forming verb-stems in OE: (1) by means of vowel interchange of the root vowel; (2) by means of suffixation

MORPHOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION OF VERBS All OE verbs may be subdivided into a number of groups in accordance with the grammatical means with the help of which they built their principal stems. There were two principal means forming verb-stems in OE: (1) by means of vowel interchange of the root vowel; (2) by means of suffixation

In accordance with these two methods of the formation of the verb-stems all the verbs in OE formed two main groups — the strong verbs and the weak verbs. The strong verbs have four principal forms, the weak ones — three principal forms

In accordance with these two methods of the formation of the verb-stems all the verbs in OE formed two main groups — the strong verbs and the weak verbs. The strong verbs have four principal forms, the weak ones — three principal forms

STRONG VERBS The strong verbs are verbs which use vowelinterchange as the principal means of expressing different grammatical categories. This vowel interchange, or ‘ablaut’, which was the principal grammatical means in the conjugation of the Old English strong verbs was of two kinds: qualitative and quantitative

STRONG VERBS The strong verbs are verbs which use vowelinterchange as the principal means of expressing different grammatical categories. This vowel interchange, or ‘ablaut’, which was the principal grammatical means in the conjugation of the Old English strong verbs was of two kinds: qualitative and quantitative

WEAK VERBS The Old English weak verbs are relatively younger than the strong verbs and reflect a later stage in the development of Germanic languages. They were an open class in Old English, as new verbs that entered the language generally formed their forms as weak verbs. As a means of differentiation among principal verb stems, the weak verbs used suffixation, namely, suffixes -t or -d, ex. : cepan — cepte — cept ’ ‘keep

WEAK VERBS The Old English weak verbs are relatively younger than the strong verbs and reflect a later stage in the development of Germanic languages. They were an open class in Old English, as new verbs that entered the language generally formed their forms as weak verbs. As a means of differentiation among principal verb stems, the weak verbs used suffixation, namely, suffixes -t or -d, ex. : cepan — cepte — cept ’ ‘keep

REGULAR AND IRREGULAR VERBS Regularity means conformity with some unique principle or pattern. It does not require any exact material marker. That is why it is said that most verbs in Old English were regular. However, there were also a few irregular verbs, conjugated in some specific way. The sign of irregularity of the weak verbs in Old English was vowel interchange, a feature not typical of this group of verbs

REGULAR AND IRREGULAR VERBS Regularity means conformity with some unique principle or pattern. It does not require any exact material marker. That is why it is said that most verbs in Old English were regular. However, there were also a few irregular verbs, conjugated in some specific way. The sign of irregularity of the weak verbs in Old English was vowel interchange, a feature not typical of this group of verbs

SUMMARY v. The principal grammatical means used in the paradigm of declension was suffixation, in the paradigm of conjugation — vowel gradation

SUMMARY v. The principal grammatical means used in the paradigm of declension was suffixation, in the paradigm of conjugation — vowel gradation

v With reference to the structure of the noun three elements of word-structure are observed: root + stem-suffix + grammatical ending. In the verb only two elements are observed: the root and the grammatical ending

v With reference to the structure of the noun three elements of word-structure are observed: root + stem-suffix + grammatical ending. In the verb only two elements are observed: the root and the grammatical ending

v The system of declension manifested a tendency to simplification from the point of view of the number of declensions and the number of grammatical categories

v The system of declension manifested a tendency to simplification from the point of view of the number of declensions and the number of grammatical categories

v. The system of conjugation preserved its principal groups and classes of verbs and also retained and developed its original grammatical categories

v. The system of conjugation preserved its principal groups and classes of verbs and also retained and developed its original grammatical categories

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION: 1. General survey of the Middle English period (ME) 2. Changes in the phonetic system in Middle English 2. 1 Vowels in the unstressed position 2. 2 Vowels under stress 2. 2. 1. Qualitative changes a) Changes of monophthongs b) Changes of diphthongs 2. 2. 2 Quantitative changes a) Lengthening of vowels b) Shortening of vowels c) Consonants

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION: 1. General survey of the Middle English period (ME) 2. Changes in the phonetic system in Middle English 2. 1 Vowels in the unstressed position 2. 2 Vowels under stress 2. 2. 1. Qualitative changes a) Changes of monophthongs b) Changes of diphthongs 2. 2. 2 Quantitative changes a) Lengthening of vowels b) Shortening of vowels c) Consonants

GENERAL SURVEY OF THE MIDDLE ENGLISH PERIOD The Norman Conquest (in 1066) changed the whole course of the English language. It started a new period in the history of the language. The ME period corresponds with the centuries which lie between the Norman Conquest of 1066 and William Caxton’s introduction of printing in 1475/1476. ME is sometimes subdivided into Early ME (EME) and Late ME (LME). The boundary between them lies in the approximate birth date of Chaucer (c. 1340). v Middle English (ME) c. 1100–c. 1500 v Early Middle English (EME) c. 1100–c. 1340 v Late Middle English (LME) c. 1340–c. 1500

GENERAL SURVEY OF THE MIDDLE ENGLISH PERIOD The Norman Conquest (in 1066) changed the whole course of the English language. It started a new period in the history of the language. The ME period corresponds with the centuries which lie between the Norman Conquest of 1066 and William Caxton’s introduction of printing in 1475/1476. ME is sometimes subdivided into Early ME (EME) and Late ME (LME). The boundary between them lies in the approximate birth date of Chaucer (c. 1340). v Middle English (ME) c. 1100–c. 1500 v Early Middle English (EME) c. 1100–c. 1340 v Late Middle English (LME) c. 1340–c. 1500

The end of the eleventh century and the latter part of the twelfth is a period when very few texts composed in English appeared. There was an unbroken transmission of the spoken language; but the habit of writing English was for a while largely superseded. English after the Conquest began to exhibit greater dialectal diversity in the written mode as Latin and French took literary functions. English had a local function. When people wished to use written language for communication beyond their own localities they used the international languages: Latin and French. As a result, the ME period is the time when linguistic variation is fully reflected in the written mode. Thus the Linguistic Atlas of Late Mediaeval English records no fewer than five hundred ways of spelling the word THROUGH in use during the period of 1350– 1450

The end of the eleventh century and the latter part of the twelfth is a period when very few texts composed in English appeared. There was an unbroken transmission of the spoken language; but the habit of writing English was for a while largely superseded. English after the Conquest began to exhibit greater dialectal diversity in the written mode as Latin and French took literary functions. English had a local function. When people wished to use written language for communication beyond their own localities they used the international languages: Latin and French. As a result, the ME period is the time when linguistic variation is fully reflected in the written mode. Thus the Linguistic Atlas of Late Mediaeval English records no fewer than five hundred ways of spelling the word THROUGH in use during the period of 1350– 1450

For 200 years after the Norman Conquest, French remained the language of ordinary intercourse among the upper classes in England. At first those who spoke French were of Norman origin, but soon through intermarriage and association with the ruling class numerous people of English learned the new language, and before long the distinction between those who spoke French and those who spoke English was not ethnic but largely social. Only in the fourteenth century this situation began to change. The reasons for that were:

For 200 years after the Norman Conquest, French remained the language of ordinary intercourse among the upper classes in England. At first those who spoke French were of Norman origin, but soon through intermarriage and association with the ruling class numerous people of English learned the new language, and before long the distinction between those who spoke French and those who spoke English was not ethnic but largely social. Only in the fourteenth century this situation began to change. The reasons for that were:

v the slump in population (from six to four million) following the Black Death in the fourteenth century meant social turbulence, a labour shortage and a consequent increase in prosperity for the remaining lower-class population, who could demand higher wages; v The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381; v the growth of towns; v the rise in the size and importance of London. Similar growth has also been noted in the population of other towns, such as York, Norwich, Oxford. v Printing, brought to England by William Caxton at the end of the fifteenth century, succeeded because it met the rising demand for texts to which the old scribal system could not respond; and the Reformation made vernacular literacy a religious requirement

v the slump in population (from six to four million) following the Black Death in the fourteenth century meant social turbulence, a labour shortage and a consequent increase in prosperity for the remaining lower-class population, who could demand higher wages; v The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381; v the growth of towns; v the rise in the size and importance of London. Similar growth has also been noted in the population of other towns, such as York, Norwich, Oxford. v Printing, brought to England by William Caxton at the end of the fifteenth century, succeeded because it met the rising demand for texts to which the old scribal system could not respond; and the Reformation made vernacular literacy a religious requirement

CHANGES IN THE PHONETIC SYSTEM All vowels in the unstressed position underwent a qualitative change and became the vowel of the type of [ə] or [e] unstressed. This phonetic change had a farreaching effect upon the system of the grammatical endings of the English words which now due to the process of reduction became homonymous:

CHANGES IN THE PHONETIC SYSTEM All vowels in the unstressed position underwent a qualitative change and became the vowel of the type of [ə] or [e] unstressed. This phonetic change had a farreaching effect upon the system of the grammatical endings of the English words which now due to the process of reduction became homonymous:

forms strong OE: writan— wrāt — writon of verbs — written with the suffixes -an, -on, -en different only in the vowel component became homonymous in Middle English: writen — wrōt — writen — written

forms strong OE: writan— wrāt — writon of verbs — written with the suffixes -an, -on, -en different only in the vowel component became homonymous in Middle English: writen — wrōt — writen — written

CHANGES OF MONOPHTHONGS Out of the seven principal Old English short monophthongs o, i, u, æ, у only æ, у changed a, e, their quality in Middle English, thus [æ] became [a] and [y] became [i], the rest of the monophthongs remaining unchanged, for example:

CHANGES OF MONOPHTHONGS Out of the seven principal Old English short monophthongs o, i, u, æ, у only æ, у changed a, e, their quality in Middle English, thus [æ] became [a] and [y] became [i], the rest of the monophthongs remaining unchanged, for example:

Old. English Middle English pæt that wæs was fyrst first

Old. English Middle English pæt that wæs was fyrst first

CHANGES OF DIPHTHONGS All Old English diphthongs were contracted (became monophthongs) at the end of the Old English period. But instead of the former diphthongs that had undergone contraction at the end of the OE period there appeared in ME new diphthongs. The new diphthongs sprang into being due to the vocalization of the consonant [j] after the front vowels [e] or [æ] or due to the vocalization of the consonant [γ] or the semi-vowel [w] after the back vowels [o] and [a].

CHANGES OF DIPHTHONGS All Old English diphthongs were contracted (became monophthongs) at the end of the Old English period. But instead of the former diphthongs that had undergone contraction at the end of the OE period there appeared in ME new diphthongs. The new diphthongs sprang into being due to the vocalization of the consonant [j] after the front vowels [e] or [æ] or due to the vocalization of the consonant [γ] or the semi-vowel [w] after the back vowels [o] and [a].

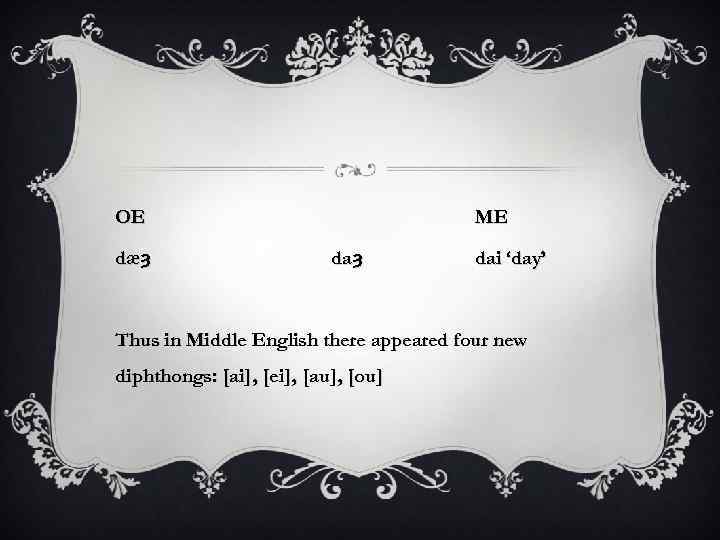

OE dæȝ ME daȝ dai ‘day’ Thus in Middle English there appeared four new diphthongs: [ai], [ei], [au], [ou]

OE dæȝ ME daȝ dai ‘day’ Thus in Middle English there appeared four new diphthongs: [ai], [ei], [au], [ou]

QUANTITATIVE CHANGES Besides qualitative changes, vowels under stress underwent certain changes in quantity

QUANTITATIVE CHANGES Besides qualitative changes, vowels under stress underwent certain changes in quantity

The first lengthening of vowels took place as early as late Old English (IX c. ). All vowels which occurred before the combinations of consonants such as mb, nd, ld became long

The first lengthening of vowels took place as early as late Old English (IX c. ). All vowels which occurred before the combinations of consonants such as mb, nd, ld became long

![LENGTHENING OF VOWELS Old English [i] > [i: ] climban findan [u] > [u: LENGTHENING OF VOWELS Old English [i] > [i: ] climban findan [u] > [u:](https://present5.com/presentation/97065352_219543927/image-56.jpg) LENGTHENING OF VOWELS Old English [i] > [i: ] climban findan [u] > [u: ] hund Middle English New English climben climb finden find hound

LENGTHENING OF VOWELS Old English [i] > [i: ] climban findan [u] > [u: ] hund Middle English New English climben climb finden find hound

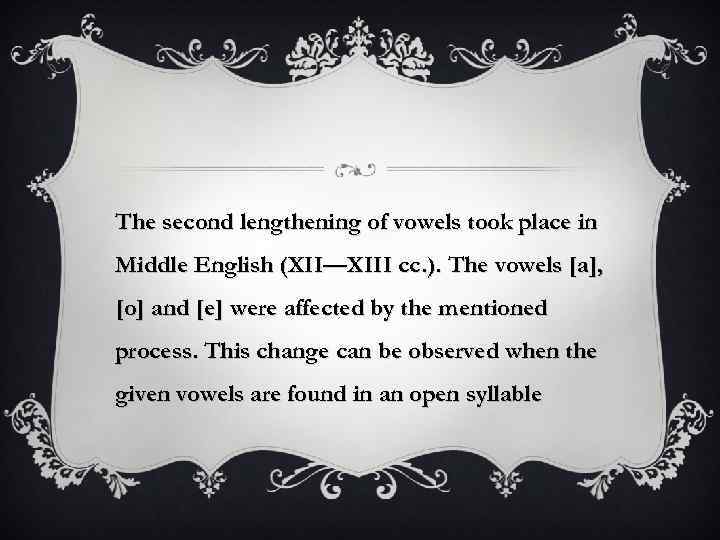

The second lengthening of vowels took place in Middle English (XII—XIII cc. ). The vowels [a], [o] and [e] were affected by the mentioned process. This change can be observed when the given vowels are found in an open syllable

The second lengthening of vowels took place in Middle English (XII—XIII cc. ). The vowels [a], [o] and [e] were affected by the mentioned process. This change can be observed when the given vowels are found in an open syllable

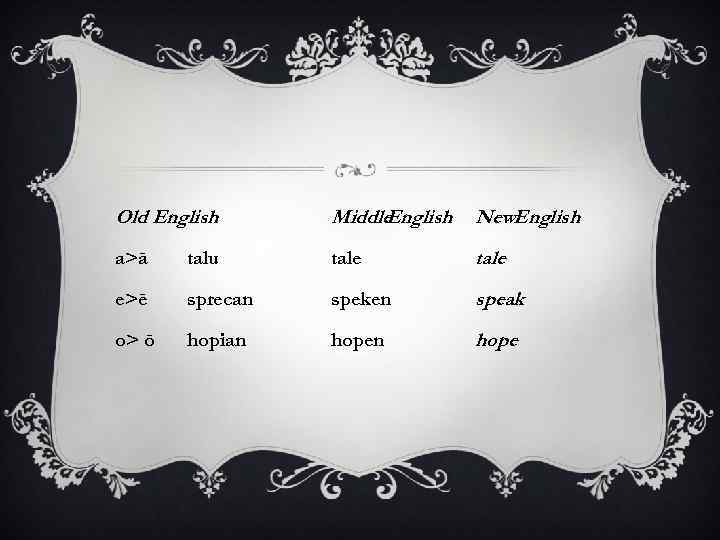

Old English Middle English New. English a>ā talu tale e>ē sprecan speken speak o> ō hopian hope

Old English Middle English New. English a>ā talu tale e>ē sprecan speken speak o> ō hopian hope

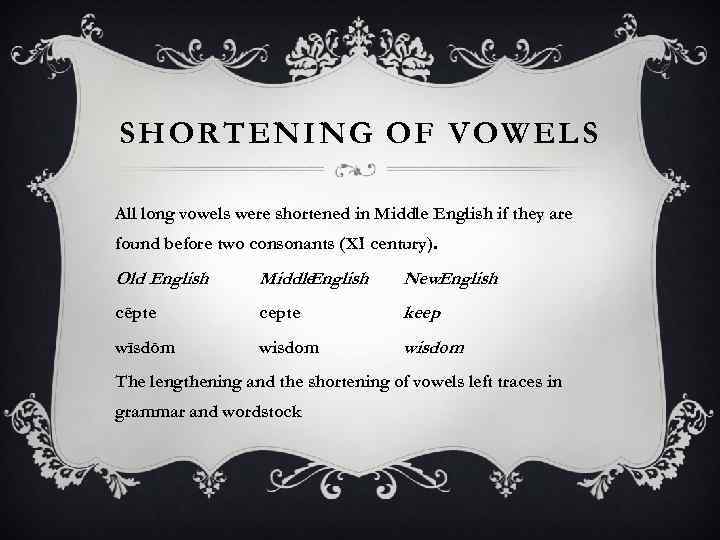

SHORTENING OF VOWELS All long vowels were shortened in Middle English if they are found before two consonants (XI century). Old English Middle English New. English cēpte cepte keep wīsdōm wisdom The lengthening and the shortening of vowels left traces in grammar and wordstock

SHORTENING OF VOWELS All long vowels were shortened in Middle English if they are found before two consonants (XI century). Old English Middle English New. English cēpte cepte keep wīsdōm wisdom The lengthening and the shortening of vowels left traces in grammar and wordstock

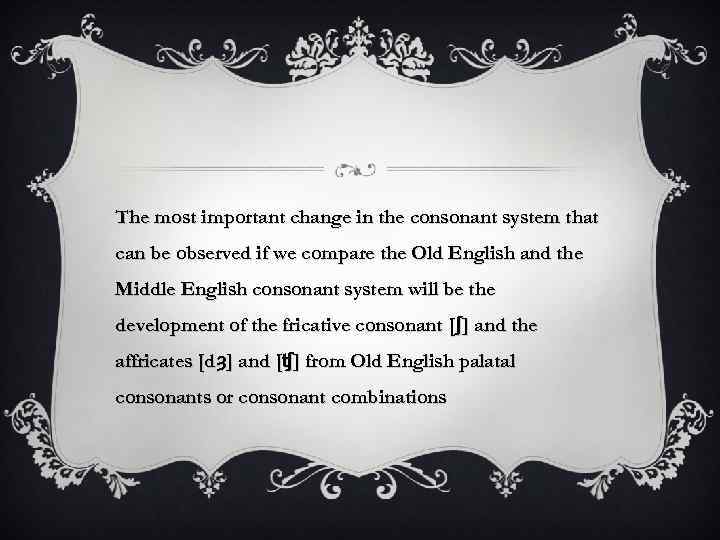

The most important change in the consonant system that can be observed if we compare the Old English and the Middle English consonant system will be the development of the fricative consonant [ʃ] and the affricates [dȝ] and [ʧ] from Old English palatal consonants or consonant combinations

The most important change in the consonant system that can be observed if we compare the Old English and the Middle English consonant system will be the development of the fricative consonant [ʃ] and the affricates [dȝ] and [ʧ] from Old English palatal consonants or consonant combinations

![The phoneme denoted in Old English by the letter с had two variants: [k] The phoneme denoted in Old English by the letter с had two variants: [k]](https://present5.com/presentation/97065352_219543927/image-61.jpg) The phoneme denoted in Old English by the letter с had two variants: [k] — hard and [k’] — palatal, the former remaining unchanged, the latter giving a new phoneme [ʧ].

The phoneme denoted in Old English by the letter с had two variants: [k] — hard and [k’] — palatal, the former remaining unchanged, the latter giving a new phoneme [ʧ].

Special notice should be taken of the development of such consonant phonemes that had voiced and voiceless variants in Old English, such as: v [f] — [v] in spelling f v [s] — [z] in spelling s v [θ] — [ð] in spelling þ. ð, They became different phonemes in Middle English

Special notice should be taken of the development of such consonant phonemes that had voiced and voiceless variants in Old English, such as: v [f] — [v] in spelling f v [s] — [z] in spelling s v [θ] — [ð] in spelling þ. ð, They became different phonemes in Middle English

SUMMARY 1. Levelling of vowels in the unstressed position. 2. No principally new monophthongs in the system of the language appeared, but the monophthongs of the [o] and [e] type may differ: they are either ‘open’ — generally those developed from the OE ā (stān > stōn) or ‘close’ — developing from the OE ō (bōc > bók ‘book’). 2. The sound [y] disappeared from the system of the language. 3. There are no long diphthongs

SUMMARY 1. Levelling of vowels in the unstressed position. 2. No principally new monophthongs in the system of the language appeared, but the monophthongs of the [o] and [e] type may differ: they are either ‘open’ — generally those developed from the OE ā (stān > stōn) or ‘close’ — developing from the OE ō (bōc > bók ‘book’). 2. The sound [y] disappeared from the system of the language. 3. There are no long diphthongs