71d11c71c435694cc79198a7a9c6af5c.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 30

Ojibwa History/Myth (Background for Tracks)

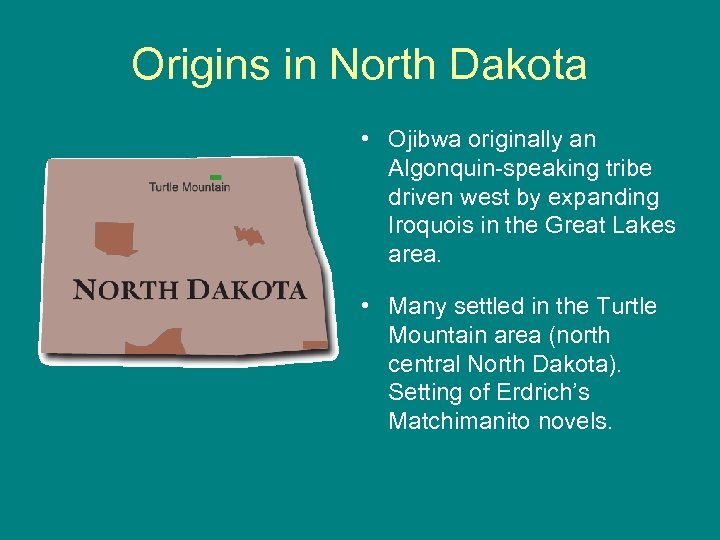

Origins in North Dakota • Ojibwa originally an Algonquin-speaking tribe driven west by expanding Iroquois in the Great Lakes area. • Many settled in the Turtle Mountain area (north central North Dakota). Setting of Erdrich’s Matchimanito novels.

French/Jesuits • 1641: Jesuits, following on the heels of French fur traders, make contact with the Chippewa. • Much intermarriage between Frenchmen and Ojibwa women, thus French names in the novel (Pillager, Lazarre, Lamartine, etc. ) • Mixed blood children (Metis) appeared as early as mid 17 th Century. • By mid-18 th Century, French fur-traders swarmed the area.

Disease • 1869 -1870: Outbreaks of smallpox throughout North Dakota • 1891 -1901: Devastating tuberculosis outbreaks; recurred during early 20 th Century • In 1908, tuberculosis is termed the “greatest single menace to the Indian race” by the U. S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs

Turtle Mountain Reservation • December 21, 1882: Turtle Mountain Reservation established by executive order • 1885: Roman Catholic school established on the reservation by Father Belacourt. Others followed, bringing nuns and teachers and building convents for them to live in.

Dawes (General Allotment) Act • 1887: Dawes Act authorizes the President to parcel tribal land to individual members. • Secretary of Interior to buy all surplus land after tribal members had received their shares. • Proceeds to be devoted to the education and “civilization” of the tribes-members had no choice in how money was to be spent.

Dawes Act, cont. • Each allotment to be held in trust by U. S. government for 25 years or longer. • After trust period, Indians would receive land become citizens, subject to laws of state or territory where they resided.

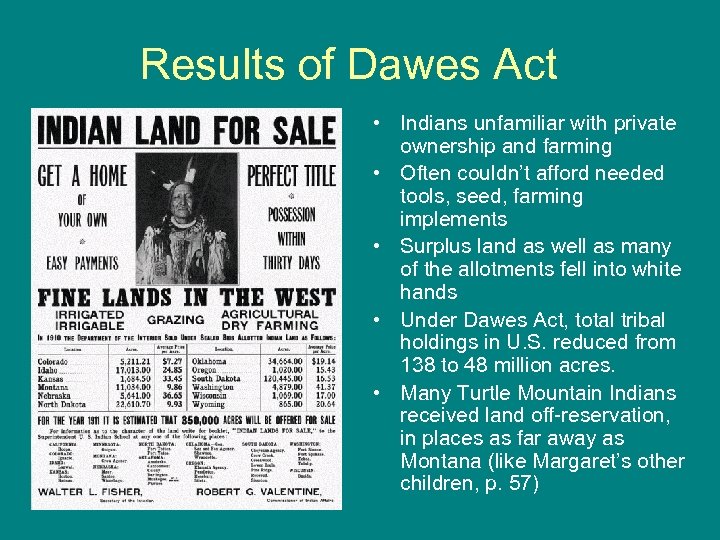

Results of Dawes Act • Indians unfamiliar with private ownership and farming • Often couldn’t afford needed tools, seed, farming implements • Surplus land as well as many of the allotments fell into white hands • Under Dawes Act, total tribal holdings in U. S. reduced from 138 to 48 million acres. • Many Turtle Mountain Indians received land off-reservation, in places as far away as Montana (like Margaret’s other children, p. 57)

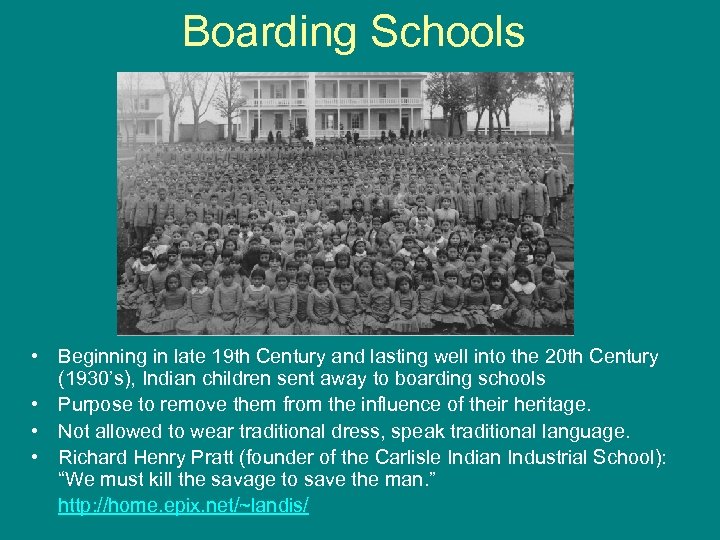

Boarding Schools • Beginning in late 19 th Century and lasting well into the 20 th Century (1930’s), Indian children sent away to boarding schools • Purpose to remove them from the influence of their heritage. • Not allowed to wear traditional dress, speak traditional language. • Richard Henry Pratt (founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School): “We must kill the savage to save the man. ” • http: //home. epix. net/~landis/

Assimilation • By early 20 th Century, religious practices tend toward a mixture of Christian and native elements. • Intermarriage had been occurring for well over two centuries; by 1910 census, only 1/3 of Ojibwa nationwide are “full-bloods. ”

Burke Act • 1906: Allowed Commissioner of Indian Affairs to shorten the 25 year trust period provided by the Dawes Act for Indians deemed “competent. ” • Land no longer held in trust could be taxed. Those deemed “competent” could sell or lease or lose allotments (as happens in Tracks).

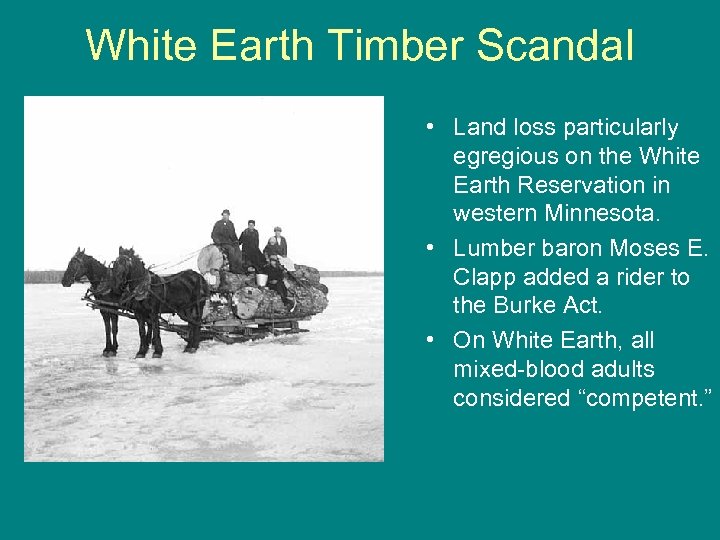

White Earth Timber Scandal • Land loss particularly egregious on the White Earth Reservation in western Minnesota. • Lumber baron Moses E. Clapp added a rider to the Burke Act. • On White Earth, all mixed-blood adults considered “competent. ”

White Earth, cont. • Erdrich and Michael Dorris write about this land-grab in a 1988 article in The New York Times Magazine. • “What followed [Clapp’s rider to the Burke Act] was a land-grab orgy so outrageous that to this day local people, regardless of ethnic heritage, speak of it with a sense of bewildered shame. ”

“Threatened, duped or plied with drink, many Chippewa signed away their deeds with an X or a thumb print and received as payment tin money, ancient horses, harnesses and sleighs, used pianos, gramophones and other worthless junk. Chippewa who disputed the sales were declared “mixedbloods, ” which meant their land was not protected, via such scientific quackeries as the test developed by Dr. Ales Hrdlicka, an influential physical anthropologist long associated with the Smithsonian Institution. It ‘consisted of drawing with some force the nail of the forefinger over the chest. ’

“Real Indians were supposed to have skin so tough that a scratch would leave no mark. It is not surprising that by such criteria fewer than 200 out of 5, 000 enrolled tribal members were judged to be ‘full-bloods, ’ and more than half the original acreage assignments soon passed from Indian control” (Erdrich, The New York Times Magazine, 35).

Turtle Mountain Effects • On Turtle Mountain Reservation, 90% of Ojibwa landowners sold or mortgaged their allotments by 1915. • Many left, only to return to the reservation destitute to live off of already-burdened relatives.

Survivors • Erdrich emphasizes that contemporary Indians are unlikely survivors: – “I think all Native Americans living today probably look back and think, ‘How, out of all the millions and millions of people who were here in the beginning, the very few who survived into the 1920’s, and the people who are alive today with some sense of their own tradition, how did it get to be me, and why? ’”

Terms • Chippewa: Comparatively modern, English name for the tribe • Ojibwa: Older English translation of tribal name • Anishinabe: Name for Ojibwa in language itself (Name Nanapush uses on p. 1 of Tracks)

Terms, cont. • Manito: Spirit. Both malevolent and benevolent. Can help or hurt humans. Neither good nor evil in themselves • Matchimanito Lake: Fictional lake in many of Erdrich’s novels • Misshepeshu: Water monster (underwater manito) – associated with both lion and serpent – inspired awe and terror, but also reverence – Responsible for both malicious and good deeds – Caused rapids, stormy waters, sank canoes, and drowned Indians – Also could feel and shelter those who fell through the ice

Windigo • Ojibwa spirit shared by other Algonquin tribes. Represented as an enormous cannibal made of ice, with a voracious appetite for human flesh, the embodiment of winter starvation. Hunters who never return from the woods are said to have been devoured by the windigo. But the windigo can also possess a human being, vampirically turning the person into a cannibal like itself.

Some Definitions of the Native American Trickster • Alan Velie (from "The Trickster Novel, " in Narrative Chance: Postmodern Discourse on Native American Indian Literatures) • The tribal trickster is not a single figure; tricksters differ greatly from tribe to tribe and even from tale to tale in the repertoire of the same tribe. Sometimes trickster is human, such as the Winnebago Wakdjunkaga and Blackfeet Napi; among other tribes trickster takes the form of Coyote, Raven or Hare. Whatever his form, trickster has a familiar set of characteristics: he plays tricks and is the victim of tricks; he is amoral and has strong appetites, particularly for food and sex; he is footloose, irresponsible and callous, but somehow almost always sympathetic if not lovable.

• Paul Radin (from The Trickster: A Study in American Indian Mythology) • [The trickster is] at the same time creator and destroyer, giver and negator, he who dupes others and who is always duped himself. He wills nothing consciously. At all times he is constrained to behave as he does from impulses over which he has no control. He knows neither good nor evil yet he is responsible for both. He possesses no values, moral or social, is at the mercy of his passions and appetites [and yet, ] through his actions all values come into being. . Laughter, humour and irony permeate everything Trickster does. The reaction of the audience in aboriginal societies to both him and his exploits is prevailingly one of laughter tempered by awe. . . Yet it is difficult to say whether the audience is laughing at him, at the tricks he plays on others, or at the implications his behavior and activities have for them.

• Gerald Vizenor (from "Trickster Discourse: Comic Holotropes and Language Games, " in Narrative Chance: Postmodern Discourse on Native American Indian Literatures) • Naanabozho, the woodland tribal trickster, is. . . androgynous, a comic healer and liberator in literature. . . The trickster is a comic discourse, a collection of "utterances" in oral traditions; the opposite of a comic discourse is a monologue, an utterance in isolation, which comes closer to the tragic mode in literature and not a comic tribal world view. • Andrew Wiget (from "His Life in His Tail: The Native American Trickster and the Literature of Possibility, " in Redefining American Literary History) • The trickster is a wanderer on the fringes of the community, both marginal and central to the culture at once. As an "animate principle of disruption, " the trickster questions rigid defininitions and boundaries, and challenges cultural assumptions.

• Paula Gunn Allen (from The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions) • [The Southwest trickster coyote] is a tricky personage--half creator, half fool; he (or she in some versions) is renowned for greediness and salaciousness. Coyote tales abound all over native America. . He [Coyote] is also a metaphor for continuance, for Coyote survives and a large part of his bag of survival tricks is his irreverence. Because of this irreverence for everything--sex, family, bonding, sacred things, even life itself--Coyote survives. He survives partly out of luck, partly out of cunning, and partly because he has, beneath a scabby coat, such great creative prowess. . . Certainly the time frame we presently inhabit has much that is shabby and tricky to offer; and much that needs to be treated with laughter and ironic humor; it is this spirit of the trickstercreator that keeps Indians alive and vital in the face of horror.

• Theresa Smith. (from The Island of the Anishnaabeg) • Culture hero and trickster. . . Nanabush is also referred to as the Great Rabbit or the Great White Hare. . [He was called this] because he was so fast and tricky. Nanabush not only moved quickly but could disappear in an instant, like a rabbit going down a hole. . people who act like clowns or tricksters are said to be Nanbush or Nanabushlike. . Nanabush is a completely ambiguous character. . both a sly manipulator and a buffoon, who, even as he creates, destroys; as he gives, steals; and as he fools others, is himself fooled.

Medicine Practices from Kate Mc. Cafferty, “Generative Adversity: Shapeshifting Pauline/Leopolda in Tracks and Love Medicine” Three Types of Medicine Practices in Traditional Ojibwa Cultures 1. 2. 3. Midewiwin or Medicine Lodge Society. Largest and most common of practices. Intent of society members to come together to ensure the long life and good health of its members. All medicines and power benevolent and protective. Je’sako. Medicine men and women also known as tent shakers. Diviners and doctors of great power who could call on spirits to cure and who could return souls to bodies. Wa’bano. Information on this group more sketchy. A small, elite order of prophets or witches who could furnish hunting medicine, herbal remedies, sell love powders and charms. Sometimes said to perform cannibalistic rites (thus associated with the figure of the windigo). Often viewed as having obtained the patronage of some “evil” power. Connected to Kokoko, the owl.

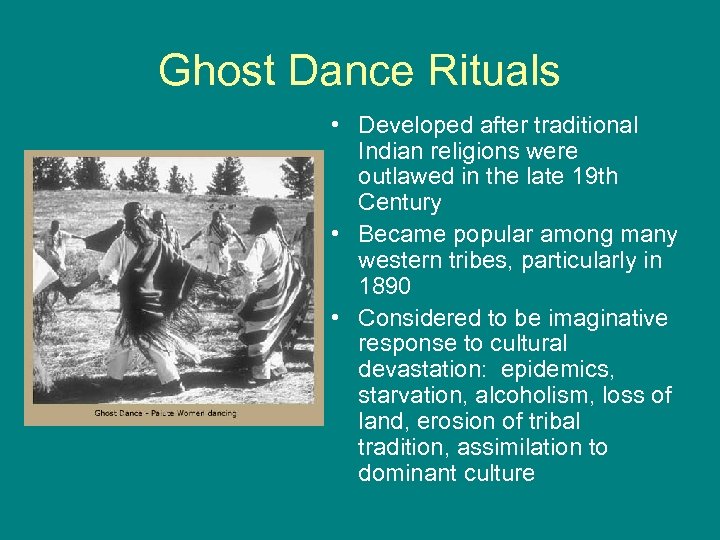

Ghost Dance Rituals • Developed after traditional Indian religions were outlawed in the late 19 th Century • Became popular among many western tribes, particularly in 1890 • Considered to be imaginative response to cultural devastation: epidemics, starvation, alcoholism, loss of land, erosion of tribal tradition, assimilation to dominant culture

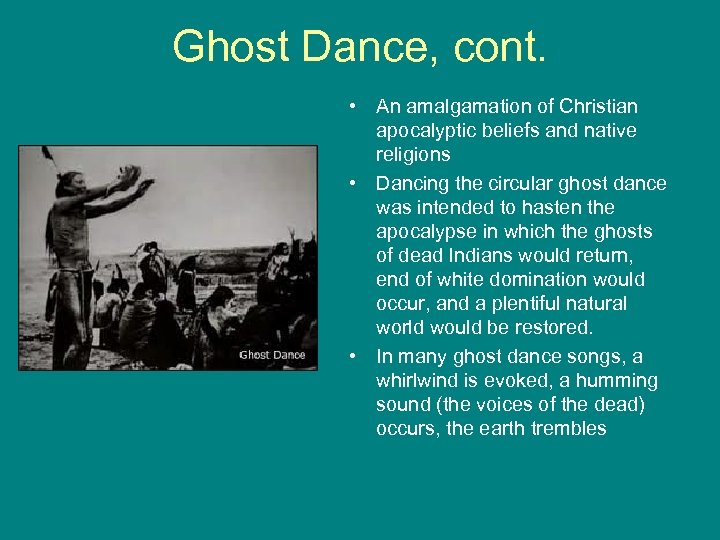

Ghost Dance, cont. • An amalgamation of Christian apocalyptic beliefs and native religions • Dancing the circular ghost dance was intended to hasten the apocalypse in which the ghosts of dead Indians would return, end of white domination would occur, and a plentiful natural world would be restored. • In many ghost dance songs, a whirlwind is evoked, a humming sound (the voices of the dead) occurs, the earth trembles

Some Sample Ghost Dance Songs The earth has come, It is rising -- Eye'ye'! It is humming -- Ahe'e'ye! When you meet your friends again -Ahe'e'ye'! The earth will tremble -- E'ahe'e'ye! The summer cloud It will give it to us, It will give it to us. I am coming in sight -- Ehe'ee'ye! I bring the whirlwind with me -- E'yahe'ye'! That you may see each other -That you may see each other.

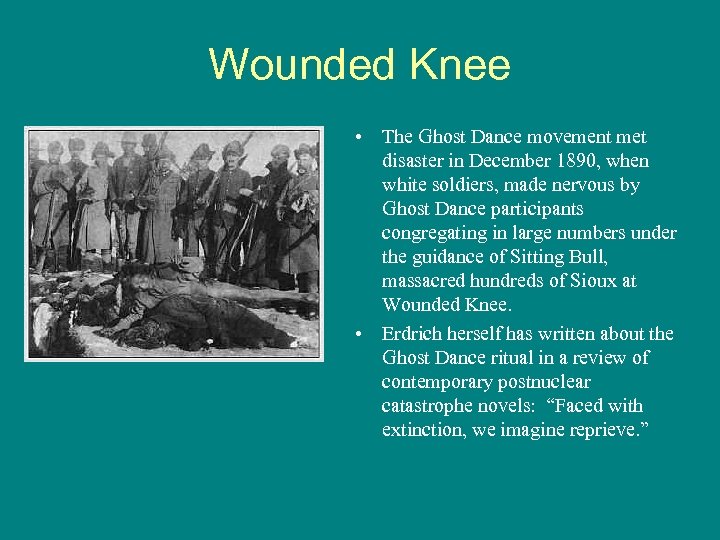

Wounded Knee • The Ghost Dance movement met disaster in December 1890, when white soldiers, made nervous by Ghost Dance participants congregating in large numbers under the guidance of Sitting Bull, massacred hundreds of Sioux at Wounded Knee. • Erdrich herself has written about the Ghost Dance ritual in a review of contemporary postnuclear catastrophe novels: “Faced with extinction, we imagine reprieve. ”

71d11c71c435694cc79198a7a9c6af5c.ppt