28195b9215f81279ba7a6110c0b2bbf7.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 31

obligations 1

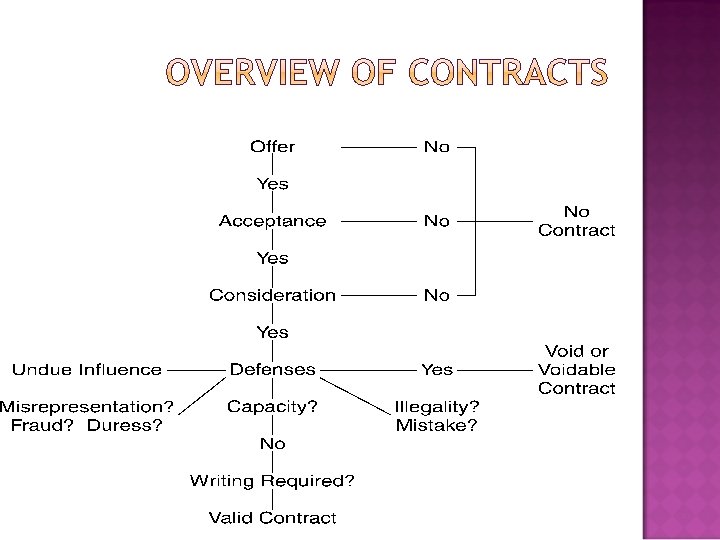

OFFER ACCEPTANCE CONSIDERATION GENUINE ASSENT Intention to be legally bound

OFFER Parties Offeror = person who makes offer Offeree = person who receives offer Must have language that indicates intent to contract Not just inquiry More than negotiation Courts use an objective, not a subjective, standard

An expression of willingness to contract on certain terms, made with intention (actual or apparent) that it shall be binding as soon as it is accepted by the person to whom it is addressed.

Elements of the Offer: Three requirements must be met: Objective intent definite offer must be communicated to offeree intended by offeror.

Objective intent issue: whether a reasonable person viewing the circumstances would conclude that the persons intended to be legally bound by the offer.

“In contracts you do not look into the actual intent in a mans mind. You look at what he said and did. A contract is formed when there is to all outward appearances a agreement” Lord Denning Storer v Manchester City Council [1974] 3 All ER 824 at page 828 A man can not get out of a contract by saying “I did not intend to make a contract”

A simple contract (that is, a contract made not under seal) requires an offer made by one party and accepted by the other, valuable consideration given by either side, or a common intention that the agreement should be legally binding

An offer is made when one party makes it clear, by words or actions, that he is prepared to be bound as soon as the offer is accepted by the person to whom it is made. An offer is thus quite different from an invitation to treat, though it is not always easy to distinguish the two.

An offer once accepted creates an agreement An offer can be contrasted with an invitation to treat An invitation to treat is an invitation to enter negotiations The “acceptance” of an invitation to treat does NOT create an agreement

![• • Grainger v Gough [1896] AC 325, HL AA were London agents • • Grainger v Gough [1896] AC 325, HL AA were London agents](https://present5.com/presentation/28195b9215f81279ba7a6110c0b2bbf7/image-13.jpg)

• • Grainger v Gough [1896] AC 325, HL AA were London agents for a French wine merchant X; they distributed catalogues and accepted orders which they passed on to X, X reserving the right to refuse any order. The case turned on whether X was liable for tax on contracts made by his agents in England. The House of Lords held that the distribution of catalogues was an invitation to treat and that the offer was made by the intending purchaser. This offer was transmitted by AA to X, and the contract was not made until X accepted the offer in France.

![• • Gibson v Manchester CC [1979] 1 All ER 972, HL A • • Gibson v Manchester CC [1979] 1 All ER 972, HL A](https://present5.com/presentation/28195b9215f81279ba7a6110c0b2bbf7/image-14.jpg)

• • Gibson v Manchester CC [1979] 1 All ER 972, HL A local council write to tenants inviting them to apply to purchase their homes. One such tenant P did apply, and a price was agreed. Following a change of party control, the new council DD refused to go ahead with the sale. The House of Lords said there was no binding contract: P had made an offer which DD had not yet accepted. Phrases in the correspondence such as "may be prepared to sell" and "please complete the enclosed application form" were indicative of an invitation to treat.

A display of goods in a shop window, or on the shelves of a self-service shop, is generally regarded as an invitation to treat rather than as an offer to sell.

![Pharmaceutical Society v Boots [1953] 1 All ER 482, CA Fisher v Bell Pharmaceutical Society v Boots [1953] 1 All ER 482, CA Fisher v Bell](https://present5.com/presentation/28195b9215f81279ba7a6110c0b2bbf7/image-16.jpg)

Pharmaceutical Society v Boots [1953] 1 All ER 482, CA Fisher v Bell [1960] 3 All ER 731, DC

This analysis of the transaction leaves both parties free to change their minds. The shopkeeper can refuse to sell to a customer whom he does not like (for example, one who is under age or drunk), and the customer having taken goods from a supermarket shelf can return them if he changes his mind before going to the till.

Why should displays be regarded as invitations to treat ?

An advertisement is usually an invitation to treat but can be an offer, depending on its wording and on the circumstances.

![Partridge v Crittenden [1968] 2 All ER 421, HC QBD Carlill v Carbolic Partridge v Crittenden [1968] 2 All ER 421, HC QBD Carlill v Carbolic](https://present5.com/presentation/28195b9215f81279ba7a6110c0b2bbf7/image-20.jpg)

Partridge v Crittenden [1968] 2 All ER 421, HC QBD Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co [1893] 1 QB 256, CA Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking [1971] 1 All ER 686, CA Wilkie v London Passenger Transport Board [1947] 1 All ER 258, CA

• At an auction sale, s. 57(2) of the Sale of Goods Act 1979 confirms the common law rule that a prospective buyer makes an offer by bidding, which the auctioneer accepts when he drops his hammer. Thus a buyer may withdraw his bid until the hammer falls, or an item may be withdrawn from the sale even after bidding has begun. The special rules for auctions, however, mean that the lot cannot legally be sold at the auction to anyone other than the highest bidder.

• • Barry v Davies (2000) Times 31/8/00, CA A sale of machinery by auction was advertised as being "without reserve". Two machines were put up, whose list price would have been £ 14000 each, but the only bid (of £ 200 each) was made by C. The auctioneer D refused to accept the bid and withdrew the machines from sale. C sued, and the judge's award of £ 27600 damages was affirmed on appeal. Although there had been no contract between vendor and purchaser, there was a collateral contract between auctioneer and bidder.

• • The growth of internet shopping has led to further developments in this area of law. Where a company advertises goods or services on its web site this is normally (depending on the wording used) an invitation to treat, and the customer makes an offer by sending in an order. So far, so good. If the company sets up an automatic e-mail reply system, this (again depending on its wording) may amount to an acceptance of the offer, and this may have unfortunate consequences for the company if there is any error (e. g. £ 100 as a misprint for £ 1000) in the published details.

Public authorities are required by law to invite tenders for many services, and some other bodies do so even when not so required. The offer in such cases is clearly made by the tender or and accepted by the authority, but the situation is more complex than it might seem.

![Harvela Investments v Royal Trust [1985] 2 All ER 966, HL Blackpool & Harvela Investments v Royal Trust [1985] 2 All ER 966, HL Blackpool &](https://present5.com/presentation/28195b9215f81279ba7a6110c0b2bbf7/image-25.jpg)

Harvela Investments v Royal Trust [1985] 2 All ER 966, HL Blackpool & Fylde Aero Club v Blackpool BC [1990] 3 All ER 25, CA

WITHDRAWL As a general rule, an offer can be withdrawn at any time before it has been accepted; any purported acceptance after withdrawal it is ineffective

![Routledge v Grant (1828) 130 ER 920, Best CJ Mountford v Scott [1975] Routledge v Grant (1828) 130 ER 920, Best CJ Mountford v Scott [1975]](https://present5.com/presentation/28195b9215f81279ba7a6110c0b2bbf7/image-27.jpg)

Routledge v Grant (1828) 130 ER 920, Best CJ Mountford v Scott [1975] 1 All ER 198, CA

Withdrawal must normally be communicated to the offeree, and does not take effect until such communication is received: the special rule for postal acceptances (below) does not apply to withdrawals.

Byrne v Van Tienhoven (1880) LR 5 CPD 344, Lindley J Dickinson v Dodds (1876) LR 2 Ch. D 463, CA Shuey v United States (1875) 92 US 73, Supreme Court (USA)

Where an offer is to be accepted by conduct, then it is not clear what rules govern its withdrawal. This is particularly important to rewards and "challenges" (e. g. £ 10 000 to the first person to swim the Atlantic): although such offers can certainly be withdrawn - that is only reasonable - it is unfair if the offeror can withdraw his offer moments before the other party "accepts" by completing the task.

Under common law, methods of termination of offer: 1. Lapse of time 2. Death of either party 3. Destruction of the subject matter 4. Rejection by the offeree 5. Revocation by the offeror

28195b9215f81279ba7a6110c0b2bbf7.ppt