43bf2ed4bb10e80e8675116bb3aa7805.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 35

Nutritional Genomics Presented by Mr. Daniel Roytas Naturopath & Nutritionist

The Birth of Nutrigenomics • Nutrigenetics was first discussed 30 years ago by Dr R. O Brennan in his book “Nutrigenetics: New Concepts for Relieving Hypoglycaemia. • “Omic” technologies have only taken off in the last 10 years thanks to the mapping of the human genome, GWAS & advances in analytical methods. • Two main branches of Nutritional “Omics”. • Nutrigenetics – The effect of genetic variation on dietary response (Eg. , Different levels of serum cholesterol and BP in individuals consuming the same diet). • Nutrigenomics - The role of nutrients and bioactive food compounds in gene expression (Eg. , PUFA suppress gene expression of fatty acid synthase in m. RNA – potential oncogene). Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

The Importance of Nutrigenomics • Nutrition research has traditionally focused on the assumption that all individuals have the same nutritional requirements (Eg. , pregnant mother, the elderly, infants etc). • Nutrition research has investigated the importance of how diet affects health and the incidence of many chronic diseases through: • • • Human intervention studies The use of biomarkers (HDL, LDL, WBC, RBC) The effects of nutrient deficiencies (B 3 & Pellagra; Vit C & Scurvy) The imbalance of macronutrients and micronutrients (Iron, Copper, Zinc) Toxic concentrations of certain food compounds (Iron, B 6, Cu, Vit A) Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

The Importance of Nutrigenomics These methods (Eg. , EAR, RDA, UL) are unable to effectively account for the multiple biological effects of foods, due to the diverse range of bioactive constituents, molecular functions and biological interactions. They are also unable to account for an individuals biological “dosage requirements”. This is due to the fact that an individual’s genetic variability directly affects: • Nutrient absorption and uptake • Binding and biotransformation • Metabolism and storage • Nutrient distribution and elimination As traditional and epidemiological nutritional studies are unable to account for such factors, technologies have been developed to better understand the mechanisms and relationships between diet and the human genome. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

The Importance of Nutrigenomics • There are several central factors that underpin nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics as an important science 1. The health effects of single nutrients and nutriomes depend on inherited genetic variants, which alter the uptake/metabolism, molecular interaction of enzymes and the activity of biochemical reactions. 2. Malnutrition (deficiency or excess) can affect gene expression and genome stability. Nutritional excess may lead to mutations at the gene sequence or chromosomal level, causing abnormal gene expression. 3. Better health outcomes can be achieved if nutritional requirements are customised for each individual taking into consideration both his/her inherited and acquired genetic characteristics. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Clinical Use Companies include (Some require in house training) • Fit. Genes • Gene. Care (Not currently available) • My. Gene (Not currently available) • Easy. DNA (Can be ordered online) • • Swab taken (usually cheek cells) and sent to laboratory. Approximately 1000 -10 000 SNPs are profiled. Results are sent to practitioners, including a report with recommendations. Practice software available from some companies to assist with treatment formulation. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

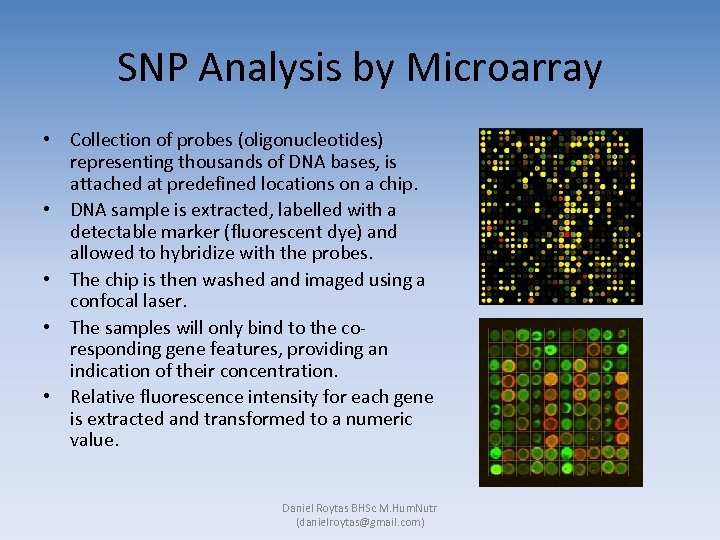

SNP Analysis by Microarray • Collection of probes (oligonucleotides) representing thousands of DNA bases, is attached at predefined locations on a chip. • DNA sample is extracted, labelled with a detectable marker (fluorescent dye) and allowed to hybridize with the probes. • The chip is then washed and imaged using a confocal laser. • The samples will only bind to the coresponding gene features, providing an indication of their concentration. • Relative fluorescence intensity for each gene is extracted and transformed to a numeric value. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Disease Prevention Early detection, or more ideally the identification of pre-disease states is an important factor in disease prevention and/or progression. The maintenance of biological homeostasis is integral for disease prevention. The loss of homeostasis results in the altered biochemical composition of tissue or cells and can be a primary cause for disease. DNA Damage can be classified as; • Damage to single bases (oxidative stress causes OH radical adhesion to a nucleotide base, Eg. , guanine) • Abasic sites in a DNA sequence (absence of a pyrimidine or purine base) • DNA strand breaks (UV, Radiation, ROS, deamination, viruses, aromatics) • Telomere shortening & chromosome breakage (Cellular replication, ageing) • Mitochondrial DNA damage Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Disease Prevention Changes to individual biomarkers only reflect modifiable homeostatic responses to altered nutritional exposure, and on their own, may not be sufficient to indicate definite irreversible pathology at the genome level. Complete profiles of genome, transcriptome, proteome and metabolome biomarkers provide a more comprehensive overview of potential interventions. This can be done through identification of changes in biomarkers; • Genome (DNA damage) • Epigenome (DNA methylation) • Transcriptome (RNA expression) • Proteome (Protein expression) • Metabolome (Metabolite changes) Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

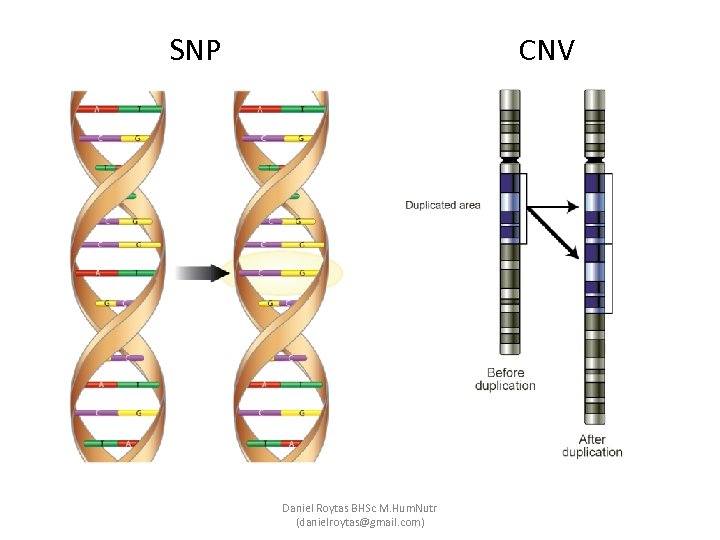

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) are the most common form of sequence variation. • Approximately 40 000 genes & >100 000 proteins currently identified. • More than 53 million SNPs have been identified, however only around 1000 have been assessed by nutritional genomics. • SNPs occur every 100 -300 bases throughout the genome. • Polymorphisms occur in 1 -50% of the population. • SNPs are often stable and do not necessarily give rise to a disease state, however may determine the likelihood for disease development. • Copy number variants (CNV) are another form of genetic variation, which account for about 12% of the human genomic DNA. • DNA and RNA purine nucleobases, adenine (A) and guanine (G) pair up with pyrimidines thymine (T) and cystosine (C) respectively. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms • One cause of deamination is the autoxidation of nitric oxide (NO) which forms the nitrosating agent N 2 O 3, which reacts with nucleotides. • Cytosine spontaenously deaminates to uracil C → U (recognised as a non-DNA base and is removed by uracil-DNA glycosylase. • Pyrimidine bases (C/T) in DNA are more susceptible to spontaneous deamination than are the purine bases (G/A). • Cytosine methylation is mediated by DNMT 1. • Methylated cytosine (prone to hyper-mutability) is known as 5 -methylcytosine. Spontaneous deamination of cytosine causes a C → T. • This mismatch is removed by MBD 4 and TDG however this process is error prone (G: T mismatch not easily recognized as T is a DNA base). This results in a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

SNP CNV Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

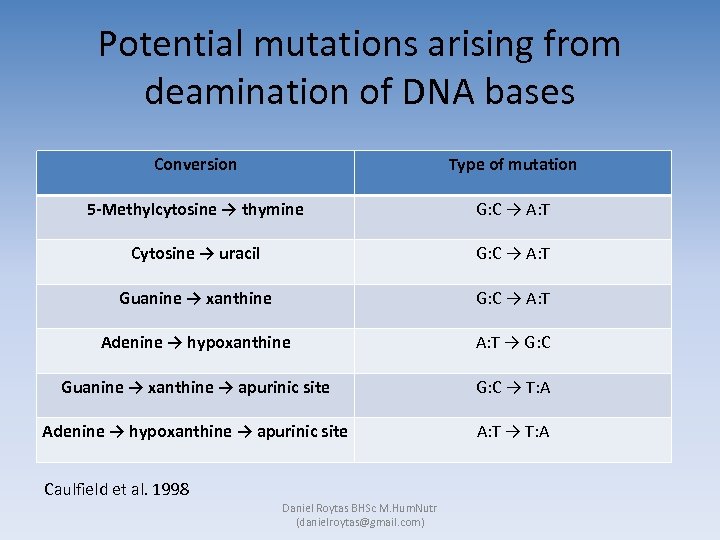

Potential mutations arising from deamination of DNA bases Conversion Type of mutation 5 -Methylcytosine → thymine G: C → A: T Cytosine → uracil G: C → A: T Guanine → xanthine G: C → A: T Adenine → hypoxanthine A: T → G: C Guanine → xanthine → apurinic site G: C → T: A Adenine → hypoxanthine → apurinic site A: T → T: A Caulfield et al. 1998 Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

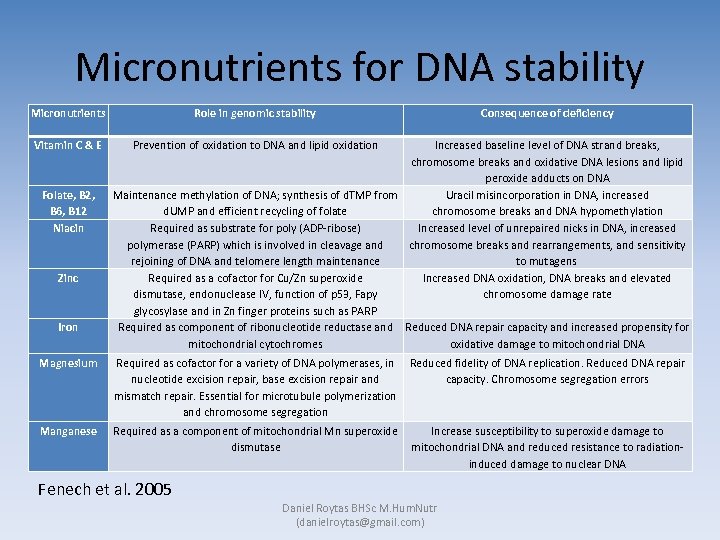

Micronutrients for DNA stability Micronutrients Role in genomic stability Vitamin C & E Prevention of oxidation to DNA and lipid oxidation Folate, B 2, B 6, B 12 Niacin Zinc Iron Consequence of deficiency Increased baseline level of DNA strand breaks, chromosome breaks and oxidative DNA lesions and lipid peroxide adducts on DNA Maintenance methylation of DNA; synthesis of d. TMP from Uracil misincorporation in DNA, increased d. UMP and efficient recycling of folate chromosome breaks and DNA hypomethylation Required as substrate for poly (ADP-ribose) Increased level of unrepaired nicks in DNA, increased polymerase (PARP) which is involved in cleavage and chromosome breaks and rearrangements, and sensitivity rejoining of DNA and telomere length maintenance to mutagens Required as a cofactor for Cu/Zn superoxide Increased DNA oxidation, DNA breaks and elevated dismutase, endonuclease IV, function of p 53, Fapy chromosome damage rate glycosylase and in Zn finger proteins such as PARP Required as component of ribonucleotide reductase and Reduced DNA repair capacity and increased propensity for mitochondrial cytochromes oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA Magnesium Required as cofactor for a variety of DNA polymerases, in Reduced fidelity of DNA replication. Reduced DNA repair nucleotide excision repair, base excision repair and capacity. Chromosome segregation errors mismatch repair. Essential for microtubule polymerization and chromosome segregation Manganese Required as a component of mitochondrial Mn superoxide dismutase Increase susceptibility to superoxide damage to mitochondrial DNA and reduced resistance to radiationinduced damage to nuclear DNA Fenech et al. 2005 Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

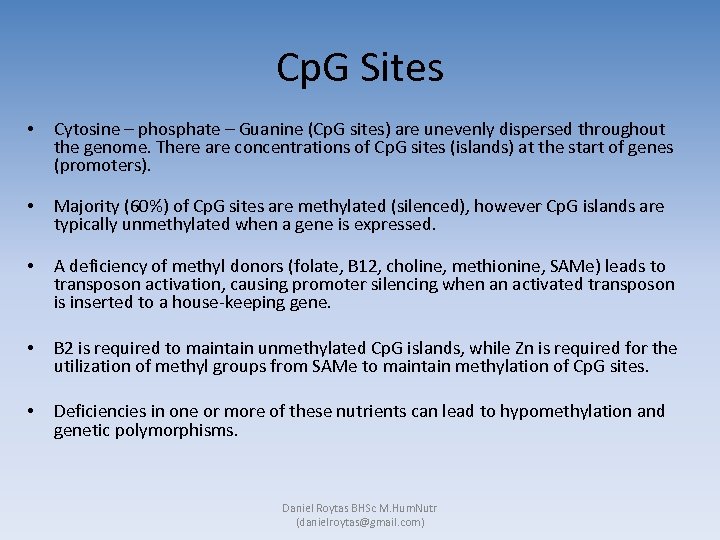

Cp. G Sites • Cytosine – phosphate – Guanine (Cp. G sites) are unevenly dispersed throughout the genome. There are concentrations of Cp. G sites (islands) at the start of genes (promoters). • Majority (60%) of Cp. G sites are methylated (silenced), however Cp. G islands are typically unmethylated when a gene is expressed. • A deficiency of methyl donors (folate, B 12, choline, methionine, SAMe) leads to transposon activation, causing promoter silencing when an activated transposon is inserted to a house-keeping gene. • B 2 is required to maintain unmethylated Cp. G islands, while Zn is required for the utilization of methyl groups from SAMe to maintain methylation of Cp. G sites. • Deficiencies in one or more of these nutrients can lead to hypomethylation and genetic polymorphisms. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

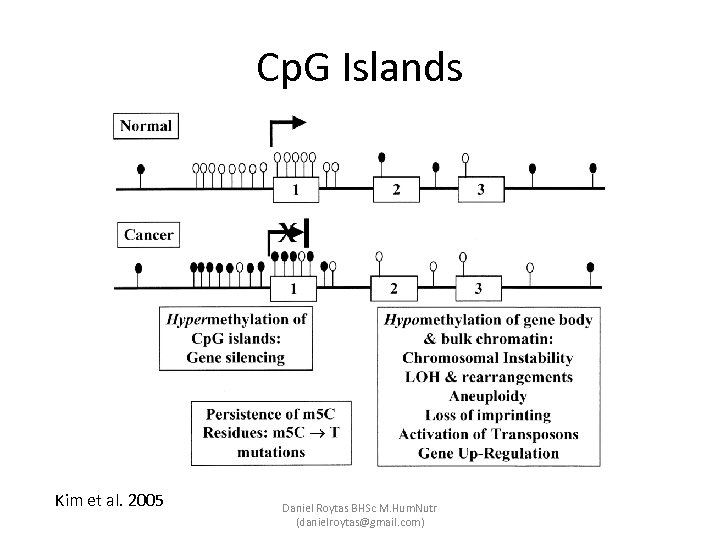

Cp. G Islands Kim et al. 2005 Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Cancer • DNA is constantly under threat of major mutations from a variety of mechanisms including point mutations, base modifications, chromosome breakage etc. • Cancer cells have a loss of methylation at Cp. G depleted regions, activating intragenomic parasitic sequences, which are transcribed to other sites. • These parasitic sequences are transcribed to promoter regions that can silence hundreds of genes (Eg. , tumour supressor genes). • A loss of methylation also leads to the activation of oncogenes. • Modest increase in DNMT 1 (hot spot) activity in cancer cells, resulting in increased nucleotide mutations of C → T. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Cancer • Folate deficiency results in uracil incorporation in to DNA instead of thymine. This leads to chromosome breakage and micronucleus formation (TDG excises uracil causing abasic sites and DNA damage). • Reduction in serum folate concentration from 120 nmol/l to 12 nmol/l is equivalent to a radiation dose (X-rays) of 0. 2 Grays (Gy) (approx 10 x higher than the safe exposure limit for radiation workers). • Folate supplementation of at least 400 -1000 μg/day is recommended. Serum folate levels peak 2 -3 hours after supplementation, however red cell levels should be measured 120 days after supplementation to gauge accurate readings. • Folinic acid is the preferable form as it does not require the dihydrofolate reductase enzyme, which is inhibited by some medications. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Cancer • Individuals with the highest intake of Vitamin E, retinol, folate, nicotinic acid and calcium have the lowest micronucleus frequency in lymphocytes. • Individuals with the highest intake of riboflavin, pantothenic acid, beta carotene and biotin have the highest levels of micronucleus frequencies. DNA damage is minimized when plasma concentrations of: • B 12 >300 μmol (Supplement with >2 μg vitamin B 12/ day) • Plasma folate concentration >34 nmol/l (Supp with >400 μg folic acid / day) • Red cell folate concentration is >700 nmol/l • Plasma homocysteine is <7. 5 μmol/l • • • Other micronutrients specific for DNA BER and/or NER: Zinc, copper, magnesium, vitamin A, C & E, B 2, Co. Q 10. Antioxidant rich foods (Kiwifruit, nectarine, raspberry, apple carrot). Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Methylene-tetrahydrofolate • MTHFR is the gene responsible for the coding of the MTHFR reductase enzyme, which converts 5, 10 MTHF to 5, MTHF. • This reaction causes the transferal of a methyl group to cobalamin (B 12), which then transfers the methyl group to homocysteine, which is then converted to methionine. • The SNP MTHFR 677 C → T, reduces homocysteine conversion to methionine, resulting in an increased risk for CVD, CRC and NTD’s. • Folinic acid supplementation is recommended in individuals with this SNP. • Individuals carrying the 677 TT genotype are more responsive than 677 CC or 677 CT carriers, and may have a lower risk of CRC. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Breast Cancer • About 5 -10% of breast cancers are believed to be hereditary. • Carriers of the lymphocyte-specific protein LSP 1 gene SNP (rs 3817198) T allele have an increased risk of +10% (effect reversed in the C allele). • Carriers of the SNP DNMT 1 A 201 G (rs 2228612) GG genotype are at lower risk of developing breast cancer compared to those carrying a C allele. • Women below the median consumption of fruits and vegetables (<764 g/day), ascorbic acid (<155 mg/day) and α-tocopherol (<7. 5 mg/day) at the greatest risk of breast cancer. This causes an SNP Mn. SOD gene C → T, disabling Mn. SODs ability to enter cells and reduce oxidative stress (ie. convert O 2 - into 02 and H 202). Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

BRCA 1 • Having this gene does not cause cancer. It is a protective gene that supresses tumour development. SNPs in this gene result in defective tumour suppression. • More than 1219 SNPs identified as having an increased risk of breast cancer. • Up to 55% increase of ovarian cancer and up to 80% increase of developing breast cancer. • Carriers of the rs 28897672 G allele have an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer compared to the T allele. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

BRCA 2 • Having this gene does not cause cancer. It is a protective gene that supresses tumour development. SNPs in this gene result in defective tumour suppression. • More than 1282 SNPs identified as having an increased risk for breast and ovarian cancer. • 25% increase of ovarian cancer and up to 80% increase of developing breast cancer. • Rs 766173 – increased breast cancer risk with G carriers of the allele compared to T. • Rs 1799944 – Homozygous carriers of the G allele have an increased risk of breast cancer compared to those carrying the A allele. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Cardiovascular Disease • Coffee contains many different bioactive compounds including diterpenoid alcohols, cafestol, kahweol and caffeine. Many studies have conflicting evidence regarding coffees role in CVD. • Carriers of the Apo. A 1 83 CC genotype have increased LDL cholesterol in response to cafestol than the CT genotype. • Carriers of the MTHFR TT genotype have homocysteine levels greater than C allele carriers, and are most responsive to folate supplementation • The SNP CYP 1 A 2 163 C → T results in reduced enzyme inducibilty and therefore slow caffeine metabolism. This SNP is associated with an increased risk of MI. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Obesity • From the ages of 25 – 55, individuals will gain an average of 15 kg, equating to about 0. 5 kg per year. • 34. 5% of QLD adults are overweight and 22. 9% are obese. • Nutrigenomics can be used to optimise nutrient intake whilst facilitating weight loss. • Arkadianos et al studied 93 participants. Control (n=43) consumed a Mediterranean diet. Treatment (n=50) consumed the same diet but with 19 nutrigenomic based recommendations. • During the first 180 days, the overall average weight loss of both groups was comparable to each other. • After 1 year, the control group begun to gain weight, whilst the nutrigenetic group continued to lose weight and had significantly improved blood glucose levels. This suggests a better compliance to nutrigenetic based interventions. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

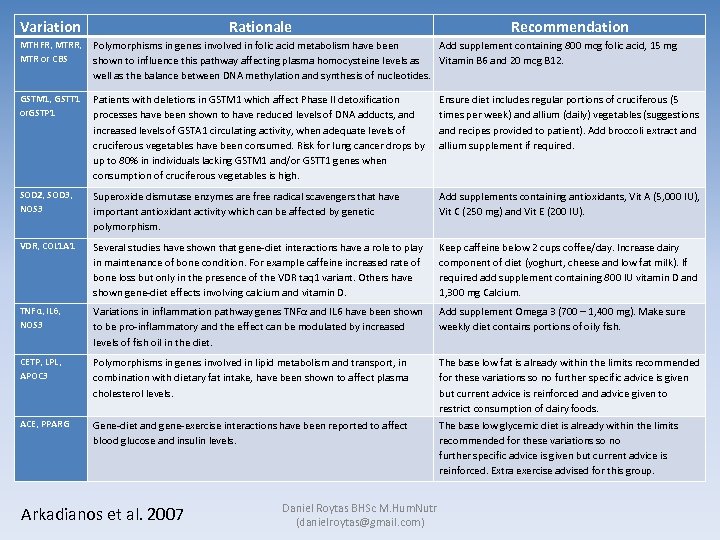

Variation Rationale MTHFR, MTRR, Polymorphisms in genes involved in folic acid metabolism have been MTR or CBS shown to influence this pathway affecting plasma homocysteine levels as Recommendation Add supplement containing 800 mcg folic acid, 15 mg Vitamin B 6 and 20 mcg B 12. well as the balance between DNA methylation and synthesis of nucleotides. GSTM 1, GSTT 1 or. GSTP 1 Patients with deletions in GSTM 1 which affect Phase II detoxification processes have been shown to have reduced levels of DNA adducts, and increased levels of GSTA 1 circulating activity, when adequate levels of cruciferous vegetables have been consumed. Risk for lung cancer drops by up to 80% in individuals lacking GSTM 1 and/or GSTT 1 genes when consumption of cruciferous vegetables is high. Ensure diet includes regular portions of cruciferous (5 times per week) and allium (daily) vegetables (suggestions and recipes provided to patient). Add broccoli extract and allium supplement if required. SOD 2, SOD 3, NOS 3 Superoxide dismutase enzymes are free radical scavengers that have important antioxidant activity which can be affected by genetic polymorphism. Add supplements containing antioxidants, Vit A (5, 000 IU), Vit C (250 mg) and Vit E (200 IU). VDR, COL 1 A 1 Several studies have shown that gene-diet interactions have a role to play in maintenance of bone condition. For example caffeine increased rate of bone loss but only in the presence of the VDR taq 1 variant. Others have shown gene-diet effects involving calcium and vitamin D. Keep caffeine below 2 cups coffee/day. Increase dairy component of diet (yoghurt, cheese and low fat milk). If required add supplement containing 800 IU vitamin D and 1, 300 mg Calcium. TNFα, IL 6, NOS 3 Variations in inflammation pathway genes TNFα and IL 6 have been shown to be pro-inflammatory and the effect can be modulated by increased levels of fish oil in the diet. Add supplement Omega 3 (700 – 1, 400 mg). Make sure weekly diet contains portions of oily fish. CETP, LPL, APOC 3 Polymorphisms in genes involved in lipid metabolism and transport, in combination with dietary fat intake, have been shown to affect plasma cholesterol levels. The base low fat is already within the limits recommended for these variations so no further specific advice is given but current advice is reinforced and advice given to restrict consumption of dairy foods. ACE, PPARG Gene-diet and gene-exercise interactions have been reported to affect blood glucose and insulin levels. The base low glycemic diet is already within the limits recommended for these variations so no further specific advice is given but current advice is reinforced. Extra exercise advised for this group. Arkadianos et al. 2007 Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

FTO Gene • FTO Gene – Function unknown however it is highly expressed in human HPA tissue, suggesting a potential role in HPA weight regulation (expression increased after food deprivation). • When presented with unlimited food supply, carriers of the SNP FTO rs 9939609 A>T consume more calories. Carriers of the A allele are more susceptible to developing obesity and T 2 D. • Carriers of the FTO rs 1421085 C allele, compared to the T allele are more at risk of developing obesity and type 2 diabetes. However this SNP is protective against type 2 diabetes in African-Americans. • The FTO rs 17817449 G allele, compared to the T allele, is also associated with an increase in developing obesity and type 2 diabetes, through reduced lipid metabolism. This leads to deposition of triglycerides in adipose tissue and reduced insulin sensitivity. • Consider arginine – which up regulates HGH release from the pituitary. Note that lysine enhances arginine’s effect. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

Perilipin • • PLIN (Perilipin lipid droplet-associated protein) gene, is the major triacylglycerolassociated protein in adipocytes responsible for the storage of lipids in adipose tissue. PLIN surrounds lipid droplets in adipocytes and regulates adipocytes metabolism by modulating interaction between lipases and triacyglycerol stores. • Carriers of these two SNPs have a resistance to weight loss and have greater insulin resistance, when their saturated fat to carbohydrate intake ratio is increased. • Carriers of the 114995 A>T allele are at greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes when consuming a diet high in saturated fat and low in carbohydrates. • Carriers of the 11482 G>A (rs 894160) allele have an increased perilipin expression and decreased lipolysis. • Isoleucine, leucine & valine for glucose regulation and improving insulin sensitivity. • N-acetyl-cysteine and carnitine stimulate lipolysis. Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

SNP Reference Tables

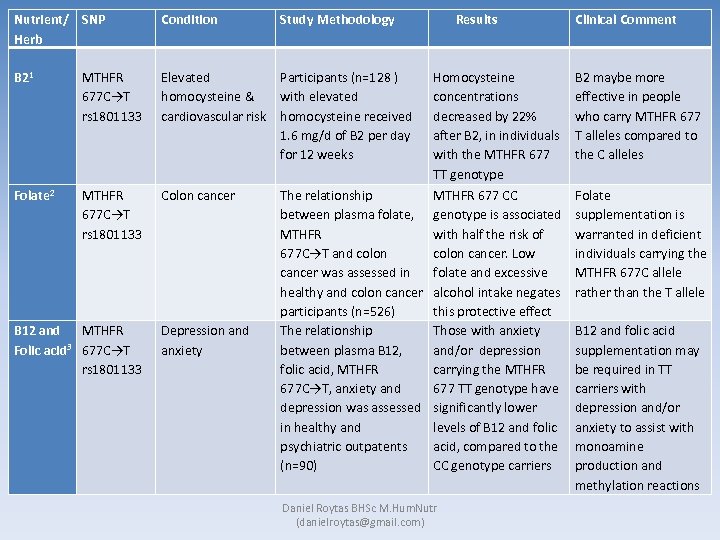

Nutrient/ SNP Herb B 21 MTHFR 677 C→T rs 1801133 Condition Study Methodology Results Clinical Comment Elevated homocysteine & cardiovascular risk Participants (n=128 ) with elevated homocysteine received 1. 6 mg/d of B 2 per day for 12 weeks Homocysteine concentrations decreased by 22% after B 2, in individuals with the MTHFR 677 TT genotype B 2 maybe more effective in people who carry MTHFR 677 T alleles compared to the C alleles Folate 2 Colon cancer The relationship between plasma folate, MTHFR 677 C→T and colon cancer was assessed in healthy and colon cancer participants (n=526) The relationship between plasma B 12, folic acid, MTHFR 677 C→T, anxiety and depression was assessed in healthy and psychiatric outpatents (n=90) MTHFR 677 CC genotype is associated with half the risk of colon cancer. Low folate and excessive alcohol intake negates this protective effect Those with anxiety and/or depression carrying the MTHFR 677 TT genotype have significantly lower levels of B 12 and folic acid, compared to the CC genotype carriers Folate supplementation is warranted in deficient individuals carrying the MTHFR 677 C allele rather than the T allele MTHFR 677 C→T rs 1801133 B 12 and MTHFR Folic acid 3 677 C→T rs 1801133 Depression and anxiety Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com) B 12 and folic acid supplementation may be required in TT carriers with depression and/or anxiety to assist with monoamine production and methylation reactions

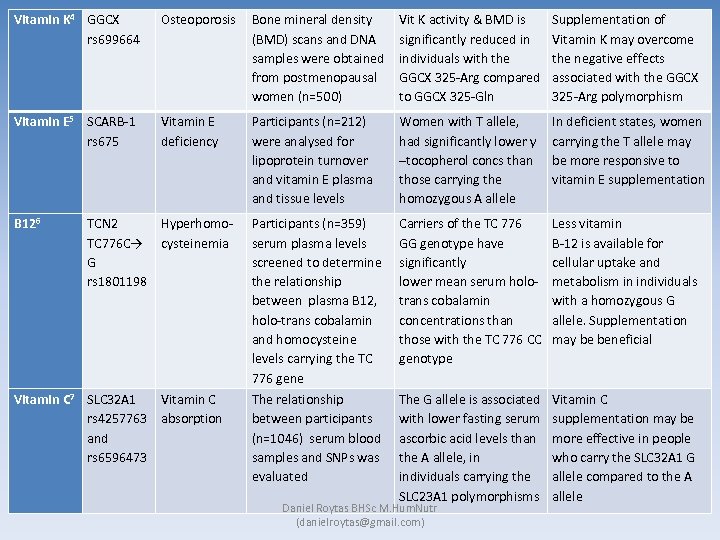

Vitamin K 4 GGCX rs 699664 Osteoporosis Bone mineral density (BMD) scans and DNA samples were obtained from postmenopausal women (n=500) Vit K activity & BMD is significantly reduced in individuals with the GGCX 325 -Arg compared to GGCX 325 -Gln Supplementation of Vitamin K may overcome the negative effects associated with the GGCX 325 -Arg polymorphism Vitamin E 5 SCARB-1 rs 675 Vitamin E deficiency Participants (n=212) were analysed for lipoprotein turnover and vitamin E plasma and tissue levels Women with T allele, had significantly lower γ –tocopherol concs than those carrying the homozygous A allele In deficient states, women carrying the T allele may be more responsive to vitamin E supplementation Participants (n=359) serum plasma levels screened to determine the relationship between plasma B 12, holo-trans cobalamin and homocysteine levels carrying the TC 776 gene Carriers of the TC 776 GG genotype have significantly lower mean serum holotrans cobalamin concentrations than those with the TC 776 CC genotype Less vitamin B-12 is available for cellular uptake and metabolism in individuals with a homozygous G allele. Supplementation may be beneficial The relationship between participants (n=1046) serum blood samples and SNPs was evaluated The G allele is associated with lower fasting serum ascorbic acid levels than the A allele, in individuals carrying the SLC 23 A 1 polymorphisms Vitamin C supplementation may be more effective in people who carry the SLC 32 A 1 G allele compared to the A allele B 126 TCN 2 Hyperhomo. TC 776 C→ cysteinemia G rs 1801198 Vitamin C 7 SLC 32 A 1 Vitamin C rs 4257763 absorption and rs 6596473 Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

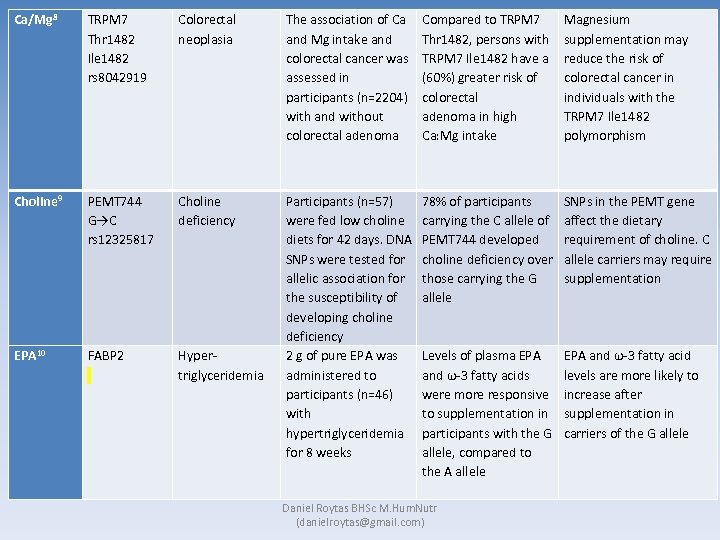

Ca/Mg 8 TRPM 7 Thr 1482 Ile 1482 rs 8042919 Colorectal neoplasia The association of Ca and Mg intake and colorectal cancer was assessed in participants (n=2204) with and without colorectal adenoma Compared to TRPM 7 Thr 1482, persons with TRPM 7 Ile 1482 have a (60%) greater risk of colorectal adenoma in high Ca: Mg intake Magnesium supplementation may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer in individuals with the TRPM 7 Ile 1482 polymorphism Choline 9 PEMT 744 G→C rs 12325817 Choline deficiency 78% of participants carrying the C allele of PEMT 744 developed choline deficiency over those carrying the G allele SNPs in the PEMT gene affect the dietary requirement of choline. C allele carriers may require supplementation EPA 10 FABP 2 Hypertriglyceridemia Participants (n=57) were fed low choline diets for 42 days. DNA SNPs were tested for allelic association for the susceptibility of developing choline deficiency 2 g of pure EPA was administered to participants (n=46) with hypertriglyceridemia for 8 weeks Levels of plasma EPA and ω-3 fatty acids were more responsive to supplementation in participants with the G allele, compared to the A allele EPA and ω-3 fatty acid levels are more likely to increase after supplementation in carriers of the G allele Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

References • Anderson CA, Beresford SA, Mc. Lerran D, Lampe JW, et al. 2013, ‘Response of serum and red blood cell folate concentrations to folic acid supplementation depends on methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C 677 T genotype: Results from a crossover trial’, Mol Nutr Food Res, vol. 57, pp. 637 -644 • Arkadianos I, Valdes AM, Marinos E, 2007, ‘Improved weight management using genetic information to personalize a calorie controlled diet’, Nutrition Journal, vol. 6, no. 29, pp. 1 -8 • Bull C, Fenech M, 2007, ‘Genome-health nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics: nutritional requirements or ‘nutriomes’ for chromosomal stability and telomere maintenance at the individual level’, Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, vol. 67, pp. 146 -156 • Caulfield JL, Wishnok JS, Tannenmaum SR, 1998, ‘Nitric oxide induced deamination of cytosine and guanine in deoxynucleosides and oligonucleosides’, Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 273, no. 21, pp. 12689 -12695 colorectal cancer risk in Korea’, Am J Clin Nutr, vol. 95, pp. 405 -412 Cornelis MC, El-Sohemy A, 2007, ‘Coffee, caffeine, and coronary heart disease’, Current Opinion in Lipidology, vol. 18, pp. 13 -19 • • • Davis CD, Milner J, 2004, ‘Frontiers in nutrigenomics, proteomics, metabolomics and cancer prevention’, Mutation Research, vol. 551, pp. 51 -64 • Dina C, Meyre D, Galliana S, et al. 2007, ‘Variation in FTO contributes to childhood obesity and severe adult obesity’, vol. 39. No. 6, pp. 724 -728 Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

References • Fenech M, 2005, ‘The Genome Health Clinic and Genome Health Nutrigenomics concepts: diagnosis and nutritional treatment of genome and epigenome damage on an individual basis’, Mutagenesis, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 255 -269 • Fenech M, et al, 2011, ‘Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomics: Viewpoints on the current status and applications in nutritional research and practice’, J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics, vol 4, pp. 69 -89 Friso S, Choi SW, 2002, ‘Gene-Nutrient Interactions and DNA Methylation’, Journal of Nutrition, s 2384 • • Garcia-Canas V, 2010, ‘Advances in Nutrigenomics research: Novel and future analytical approaches to investigate the biological activity of natural compounds and food functions’, Institute of Industrial Fermentations • Goode EL, Potter JD, Bigler J, et al. 2004, ‘Metabolism, and Colorectal Adenoma Risk Methionine Synthase D 919 G Polymorphism, Folate Metabolism and Colorectal Adenoma Risk, vol. 13, pp. 157162 • Issa JP, 2004, ‘Cp. G island methylator phenotype in cancer’, Nature Reviews, vol. 4, pp. 988 -993 • Kim J, Cho YA, Kim DH, et al. 2012, ‘Dietary intake of folate and alcohol, MTHFR C 677 T polymorphism, and Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

References • • • Kim Y, 2005, ‘Nutritional Epigenetics: Impact of Folate Deficiency on DNA Methylation and Colon Cancer Susceptibility’, Journal of Nutrition, vol. 135, no. 11, pp. 2703 -2709 Kullmann K, Deryal M, Ong MF, Schmidt W, Mahlknecht U, 2013, ‘DNMT 1 genetic polymorphisms affect breast cancer risk in the central European Caucasian population’, Clinical Epigenetics, vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 1 -8 Muller. M, Kersten S, 2003, ‘Nutrigenomics: goals and strategies’, Nature, vol. 4, pp. 315 -323 Simopoulos AP, 2010, ‘Nutrigenetics/Nutrigenomics’, Annu Rev Public Health, vol. 31, pp. 3153 Daniel Roytas BHSc M. Hum. Nutr (danielroytas@gmail. com)

43bf2ed4bb10e80e8675116bb3aa7805.ppt