96596b1a8acb6e7108f0493bb91d6afa.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 156

NURS 2410 UNIT 2 Nancy Pares, RN, MSN Metro Community College

NURS 2410 UNIT 2 Nancy Pares, RN, MSN Metro Community College

External Electronic Uterine Monitoring: Advantages • Noninvasive • Easy to place • May be used before and following rupture of membranes • Can be used intermittently • Provides a permanent, continuous recording

External Electronic Uterine Monitoring: Advantages • Noninvasive • Easy to place • May be used before and following rupture of membranes • Can be used intermittently • Provides a permanent, continuous recording

External Electronic Uterine Monitoring: Disadvantages • The nurse must compare subjective findings with monitor • The belt may become uncomfortable • The belt may require frequent readjustment • The mother may feel inhibited to move

External Electronic Uterine Monitoring: Disadvantages • The nurse must compare subjective findings with monitor • The belt may become uncomfortable • The belt may require frequent readjustment • The mother may feel inhibited to move

Internal Electronic Uterine Monitoring: Advantages • Provides pressure measurements for contraction intensity and uterine resting tone • Allows for very accurate timing of UCs • Provides a permanent record of the uterine activity

Internal Electronic Uterine Monitoring: Advantages • Provides pressure measurements for contraction intensity and uterine resting tone • Allows for very accurate timing of UCs • Provides a permanent record of the uterine activity

Internal Electronic Uterine Monitoring: Disadvantages • Membranes must be ruptured and adequate cervical dilation must be achieved • Invasive • Increases the risk of uterine infection or perforation • Contraindicated in cases with active infections • Use with a low-lying placenta can result in placenta puncture

Internal Electronic Uterine Monitoring: Disadvantages • Membranes must be ruptured and adequate cervical dilation must be achieved • Invasive • Increases the risk of uterine infection or perforation • Contraindicated in cases with active infections • Use with a low-lying placenta can result in placenta puncture

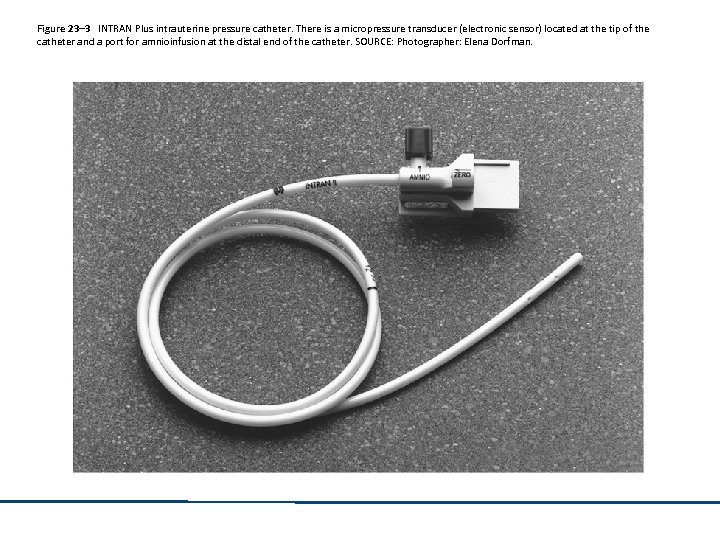

Figure 23– 3 INTRAN Plus intrauterine pressure catheter. There is a micropressure transducer (electronic sensor) located at the tip of the catheter and a port for amnioinfusion at the distal end of the catheter. SOURCE: Photographer: Elena Dorfman.

Figure 23– 3 INTRAN Plus intrauterine pressure catheter. There is a micropressure transducer (electronic sensor) located at the tip of the catheter and a port for amnioinfusion at the distal end of the catheter. SOURCE: Photographer: Elena Dorfman.

Auscultation: Advantages • • Uses minimum instrumentation Is portable Allows for maximum maternal movement Convenient and economical

Auscultation: Advantages • • Uses minimum instrumentation Is portable Allows for maximum maternal movement Convenient and economical

Auscultation: Disadvantages • Can only provide the baseline fetal heart rate, rhythms, and obvious increases and decreases • Does not provide a permanent record

Auscultation: Disadvantages • Can only provide the baseline fetal heart rate, rhythms, and obvious increases and decreases • Does not provide a permanent record

External Electronic Fetal Heart Monitoring: Advantages • Produces a continuous graphic recording • Can show the baseline, baseline variability, and changes in the FHR • Noninvasive • Does not require rupture of membranes

External Electronic Fetal Heart Monitoring: Advantages • Produces a continuous graphic recording • Can show the baseline, baseline variability, and changes in the FHR • Noninvasive • Does not require rupture of membranes

External Electronic Fetal Heart Monitoring: Disadvantages • Is susceptible to interference from maternal and fetal movement • May produce a weak signal • Tracing may become sketchy and difficult to interpret

External Electronic Fetal Heart Monitoring: Disadvantages • Is susceptible to interference from maternal and fetal movement • May produce a weak signal • Tracing may become sketchy and difficult to interpret

Internal Electronic Fetal Heart Monitoring: Advantages • Clearer tracings • Provides information about short term variability

Internal Electronic Fetal Heart Monitoring: Advantages • Clearer tracings • Provides information about short term variability

Internal Electronic Fetal Heart Monitoring: Disadvantages • Infection • Injury • Requires ruptured membranes and sufficient cervical dilatation

Internal Electronic Fetal Heart Monitoring: Disadvantages • Infection • Injury • Requires ruptured membranes and sufficient cervical dilatation

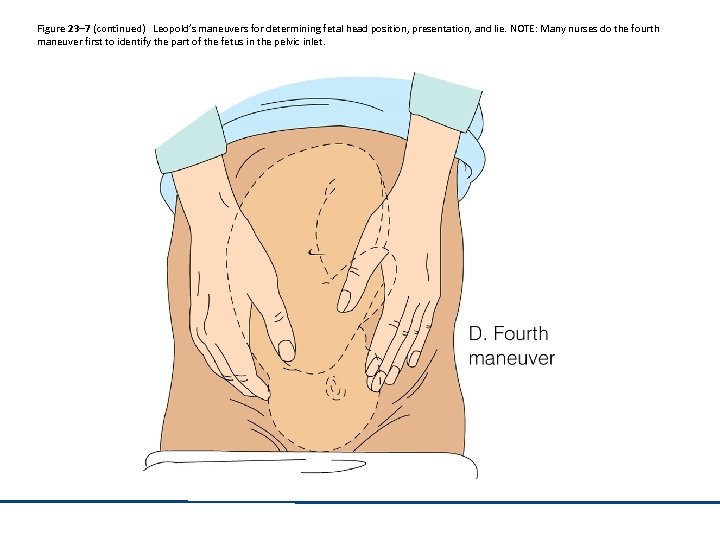

Leopold’s Maneuvers • Is the fetal lie longitudinal or transverse? • What is in the fundus? Am I feeling buttocks or head? • Where is the fetal back? • Where are the small parts or extremities? • What is in the inlet? Does it confirm what I found in the fundus? • Is the presenting part engaged, floating, or dipping into the inlet?

Leopold’s Maneuvers • Is the fetal lie longitudinal or transverse? • What is in the fundus? Am I feeling buttocks or head? • Where is the fetal back? • Where are the small parts or extremities? • What is in the inlet? Does it confirm what I found in the fundus? • Is the presenting part engaged, floating, or dipping into the inlet?

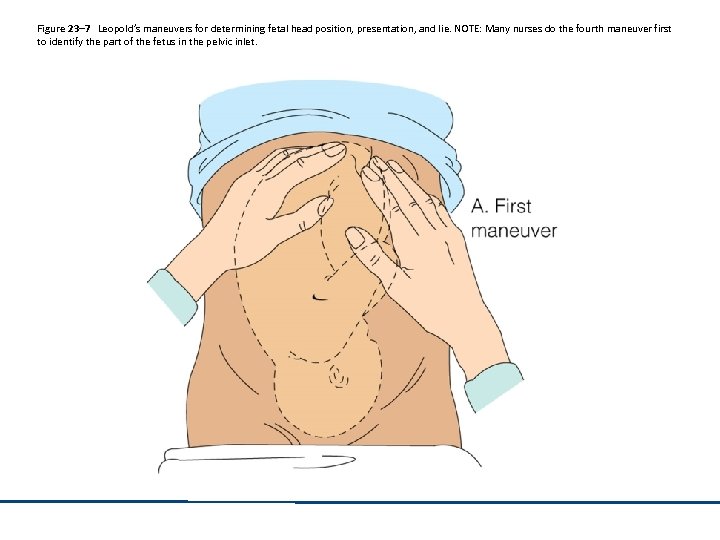

Figure 23– 7 Leopold’s maneuvers for determining fetal head position, presentation, and lie. NOTE: Many nurses do the fourth maneuver first to identify the part of the fetus in the pelvic inlet.

Figure 23– 7 Leopold’s maneuvers for determining fetal head position, presentation, and lie. NOTE: Many nurses do the fourth maneuver first to identify the part of the fetus in the pelvic inlet.

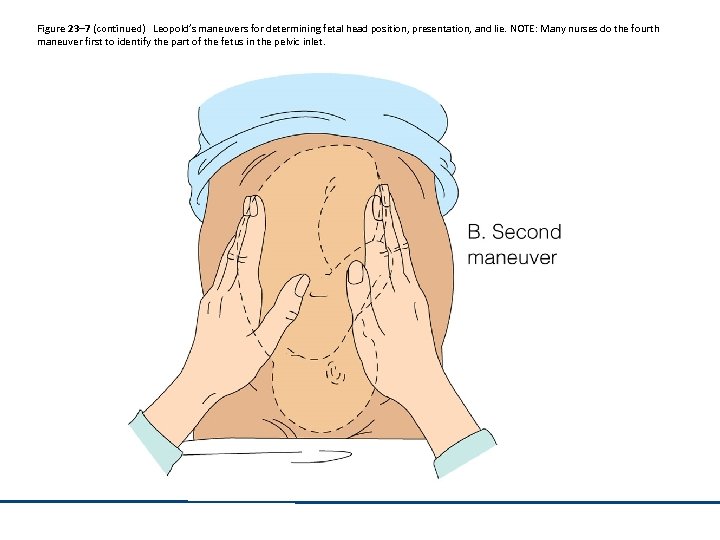

Figure 23– 7 (continued) Leopold’s maneuvers for determining fetal head position, presentation, and lie. NOTE: Many nurses do the fourth maneuver first to identify the part of the fetus in the pelvic inlet.

Figure 23– 7 (continued) Leopold’s maneuvers for determining fetal head position, presentation, and lie. NOTE: Many nurses do the fourth maneuver first to identify the part of the fetus in the pelvic inlet.

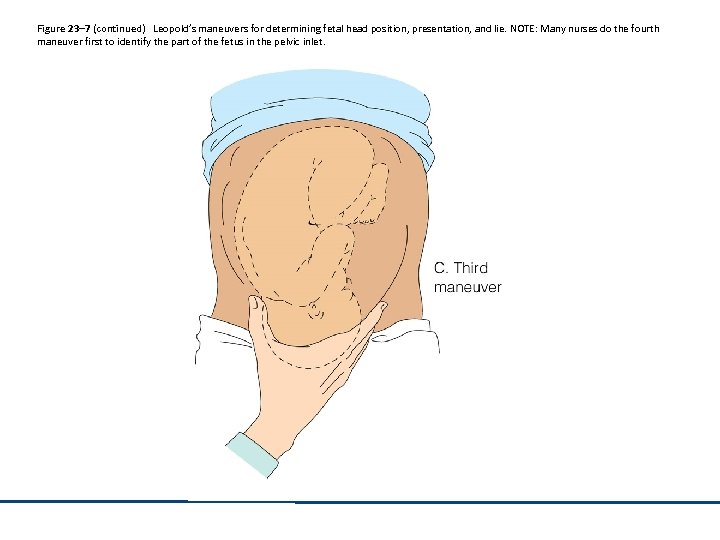

Figure 23– 7 (continued) Leopold’s maneuvers for determining fetal head position, presentation, and lie. NOTE: Many nurses do the fourth maneuver first to identify the part of the fetus in the pelvic inlet.

Figure 23– 7 (continued) Leopold’s maneuvers for determining fetal head position, presentation, and lie. NOTE: Many nurses do the fourth maneuver first to identify the part of the fetus in the pelvic inlet.

Figure 23– 7 (continued) Leopold’s maneuvers for determining fetal head position, presentation, and lie. NOTE: Many nurses do the fourth maneuver first to identify the part of the fetus in the pelvic inlet.

Figure 23– 7 (continued) Leopold’s maneuvers for determining fetal head position, presentation, and lie. NOTE: Many nurses do the fourth maneuver first to identify the part of the fetus in the pelvic inlet.

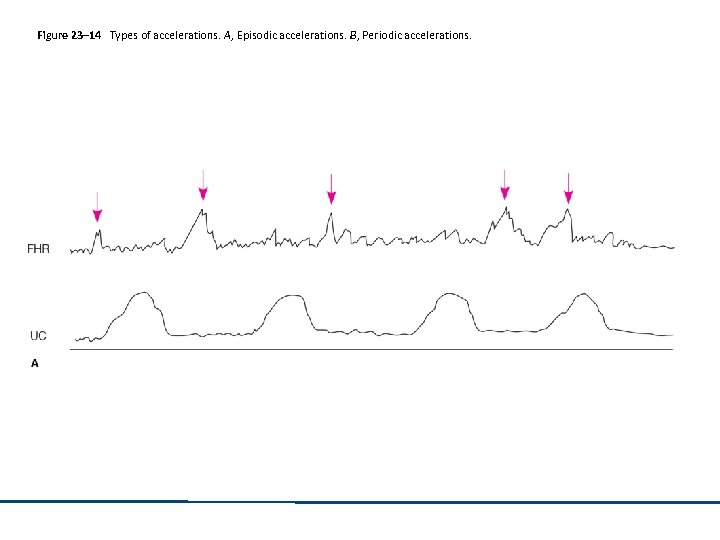

Fetal Heart Rate (FHR) • Baseline FHR – Mean FHR during 10 minute period – Must be observed for 2 minutes • Changes in FHR – Episodic – not associated with uterine contractions – Periodic – associated with uterine contractions

Fetal Heart Rate (FHR) • Baseline FHR – Mean FHR during 10 minute period – Must be observed for 2 minutes • Changes in FHR – Episodic – not associated with uterine contractions – Periodic – associated with uterine contractions

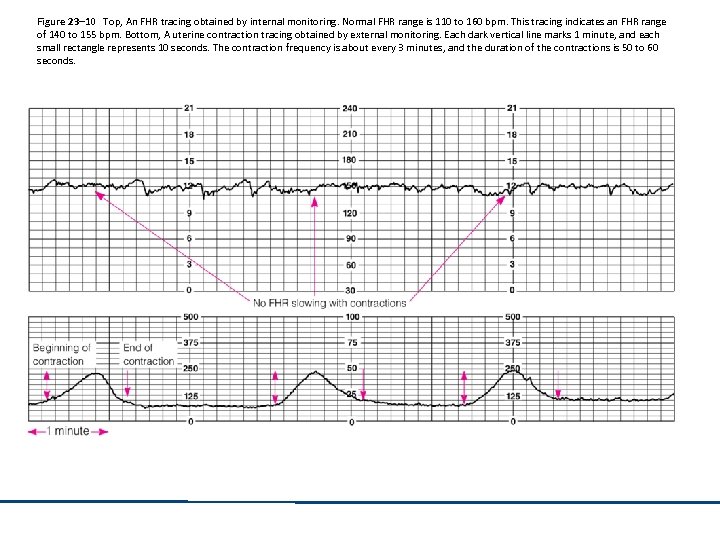

Figure 23– 10 Top, An FHR tracing obtained by internal monitoring. Normal FHR range is 110 to 160 bpm. This tracing indicates an FHR range of 140 to 155 bpm. Bottom, A uterine contraction tracing obtained by external monitoring. Each dark vertical line marks 1 minute, and each small rectangle represents 10 seconds. The contraction frequency is about every 3 minutes, and the duration of the contractions is 50 to 60 seconds.

Figure 23– 10 Top, An FHR tracing obtained by internal monitoring. Normal FHR range is 110 to 160 bpm. This tracing indicates an FHR range of 140 to 155 bpm. Bottom, A uterine contraction tracing obtained by external monitoring. Each dark vertical line marks 1 minute, and each small rectangle represents 10 seconds. The contraction frequency is about every 3 minutes, and the duration of the contractions is 50 to 60 seconds.

Changes in FHR Baseline • Fetal tachycardia – Baseline greater than 160 bpm for at least a 10 minute period • Fetal bradycardia – Baseline less than 110 bpm for at least a 10 minute period

Changes in FHR Baseline • Fetal tachycardia – Baseline greater than 160 bpm for at least a 10 minute period • Fetal bradycardia – Baseline less than 110 bpm for at least a 10 minute period

NICHD Classification: Baseline FHR • • Tachycardia Bradycardia Accelerations Sinusoidal

NICHD Classification: Baseline FHR • • Tachycardia Bradycardia Accelerations Sinusoidal

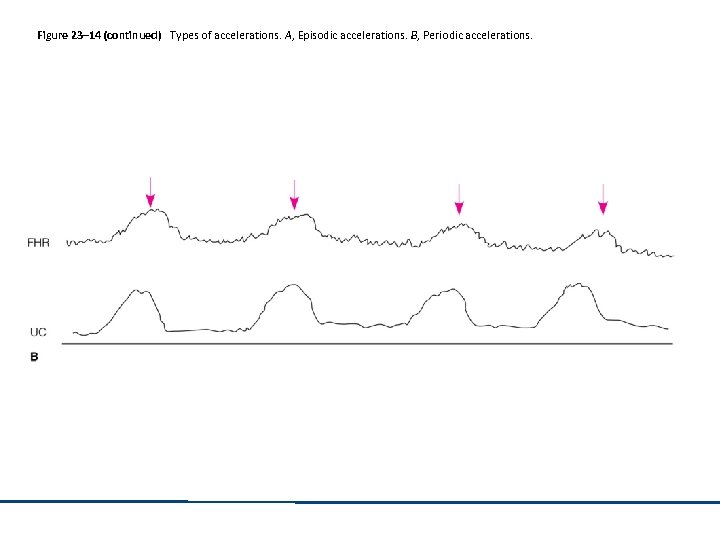

Figure 23– 14 Types of accelerations. A, Episodic accelerations. B, Periodic accelerations.

Figure 23– 14 Types of accelerations. A, Episodic accelerations. B, Periodic accelerations.

Figure 23– 14 (continued) Types of accelerations. A, Episodic accelerations. B, Periodic accelerations.

Figure 23– 14 (continued) Types of accelerations. A, Episodic accelerations. B, Periodic accelerations.

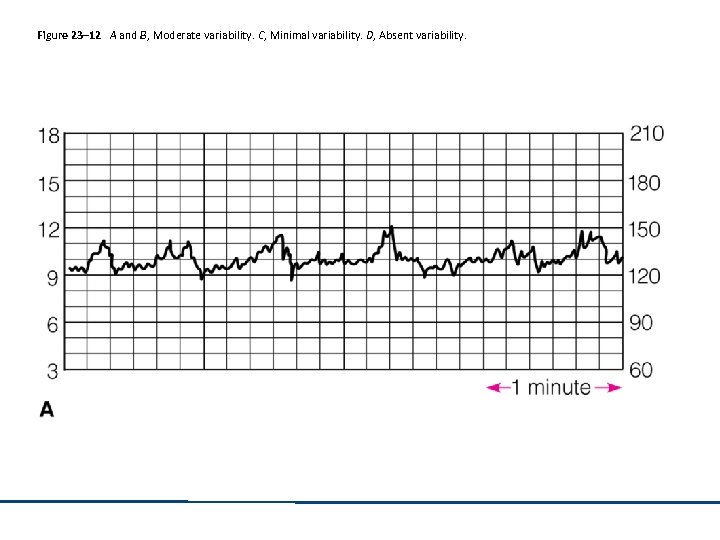

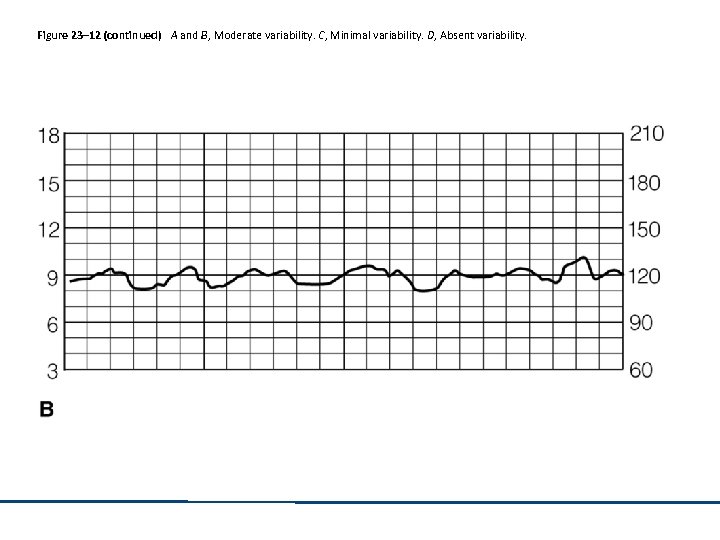

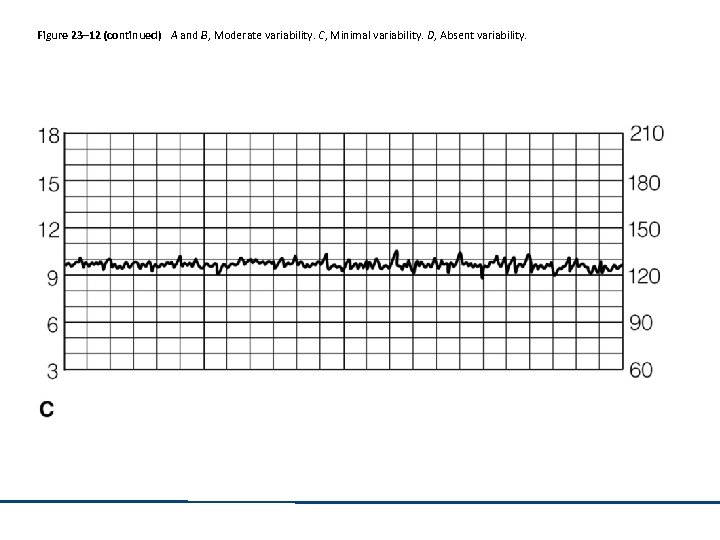

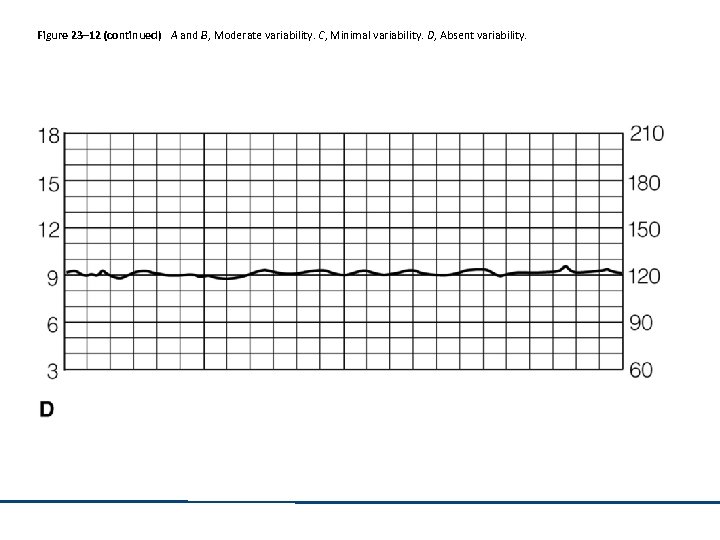

NICHD Classification: Baseline Variability (BV) • Absent – amplitude undetected • Minimal – amplitude range detectable but ≤ 5 bpm • Moderate – amplitude range of 6 -25 bpm • Marked – amplitude greater than 25 bpm

NICHD Classification: Baseline Variability (BV) • Absent – amplitude undetected • Minimal – amplitude range detectable but ≤ 5 bpm • Moderate – amplitude range of 6 -25 bpm • Marked – amplitude greater than 25 bpm

Figure 23– 12 A and B, Moderate variability. C, Minimal variability. D, Absent variability.

Figure 23– 12 A and B, Moderate variability. C, Minimal variability. D, Absent variability.

Figure 23– 12 (continued) A and B, Moderate variability. C, Minimal variability. D, Absent variability.

Figure 23– 12 (continued) A and B, Moderate variability. C, Minimal variability. D, Absent variability.

Figure 23– 12 (continued) A and B, Moderate variability. C, Minimal variability. D, Absent variability.

Figure 23– 12 (continued) A and B, Moderate variability. C, Minimal variability. D, Absent variability.

Figure 23– 12 (continued) A and B, Moderate variability. C, Minimal variability. D, Absent variability.

Figure 23– 12 (continued) A and B, Moderate variability. C, Minimal variability. D, Absent variability.

NICHD Classifications: Decelerations • Rate of descent • Episodic • Periodic – Early – Late – Variable

NICHD Classifications: Decelerations • Rate of descent • Episodic • Periodic – Early – Late – Variable

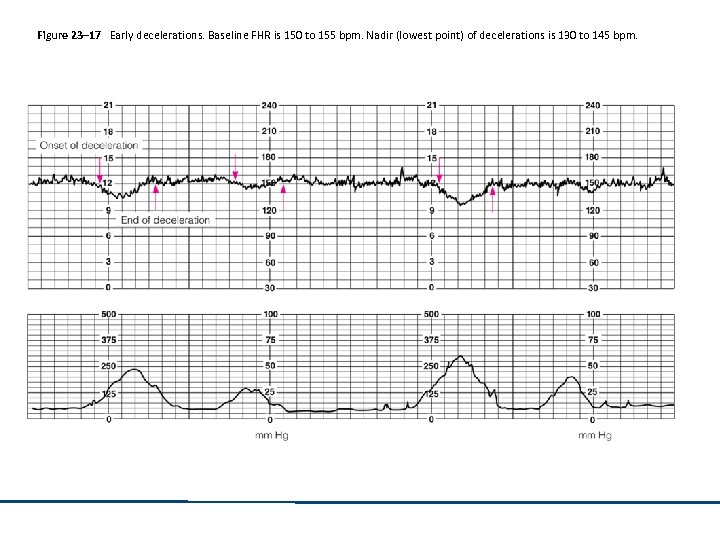

Figure 23– 17 Early decelerations. Baseline FHR is 150 to 155 bpm. Nadir (lowest point) of decelerations is 130 to 145 bpm.

Figure 23– 17 Early decelerations. Baseline FHR is 150 to 155 bpm. Nadir (lowest point) of decelerations is 130 to 145 bpm.

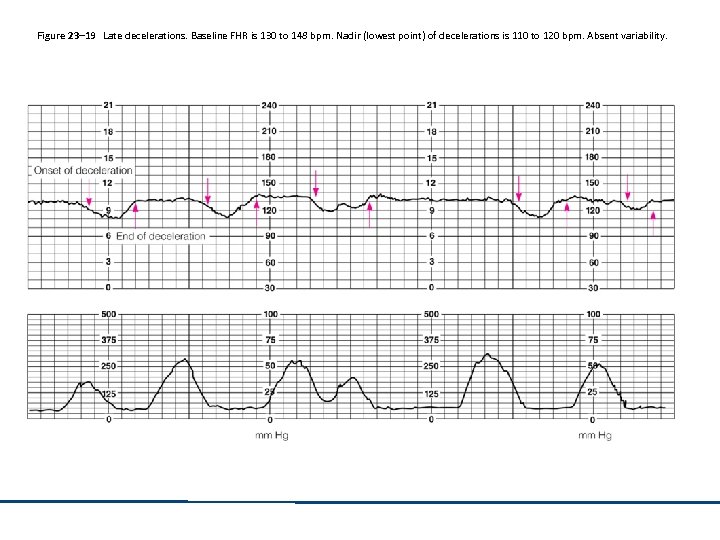

Figure 23– 19 Late decelerations. Baseline FHR is 130 to 148 bpm. Nadir (lowest point) of decelerations is 110 to 120 bpm. Absent variability.

Figure 23– 19 Late decelerations. Baseline FHR is 130 to 148 bpm. Nadir (lowest point) of decelerations is 110 to 120 bpm. Absent variability.

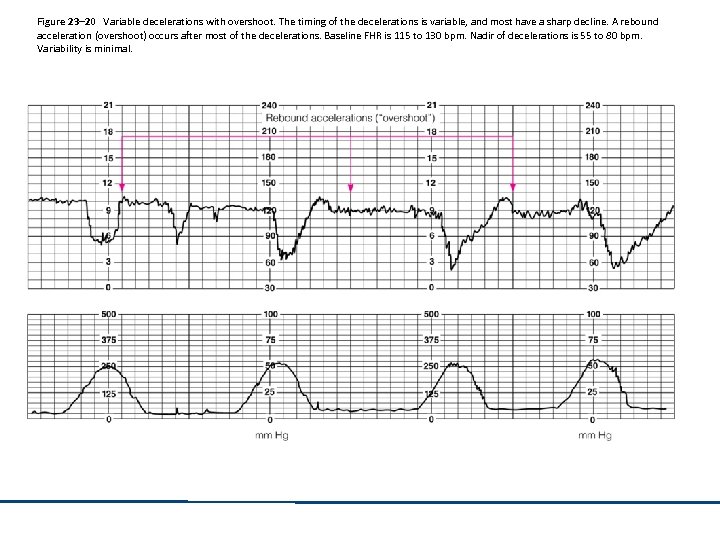

Figure 23– 20 Variable decelerations with overshoot. The timing of the decelerations is variable, and most have a sharp decline. A rebound acceleration (overshoot) occurs after most of the decelerations. Baseline FHR is 115 to 130 bpm. Nadir of decelerations is 55 to 80 bpm. Variability is minimal.

Figure 23– 20 Variable decelerations with overshoot. The timing of the decelerations is variable, and most have a sharp decline. A rebound acceleration (overshoot) occurs after most of the decelerations. Baseline FHR is 115 to 130 bpm. Nadir of decelerations is 55 to 80 bpm. Variability is minimal.

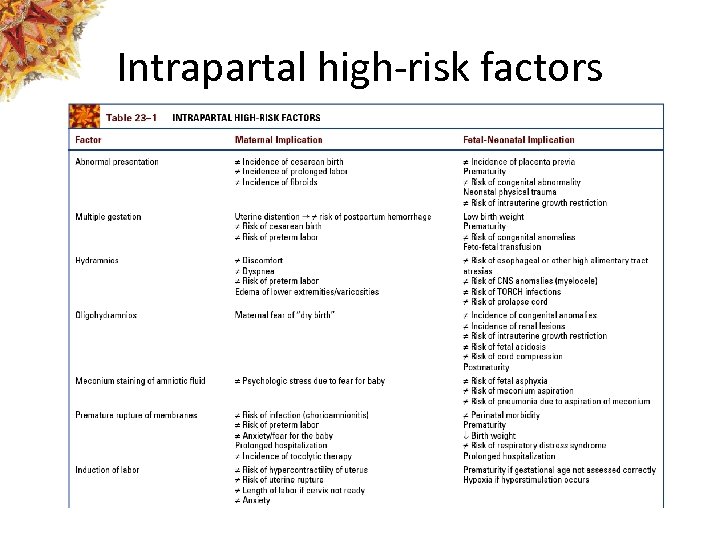

Intrapartal high-risk factors

Intrapartal high-risk factors

Intrapartal high-risk factors

Intrapartal high-risk factors

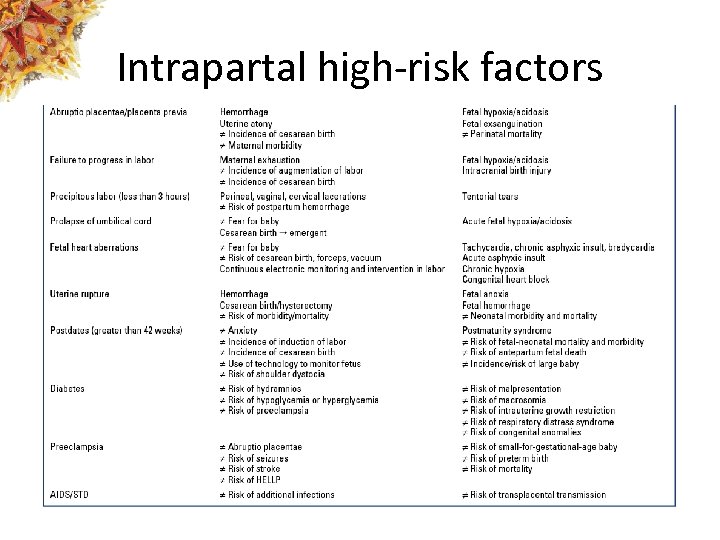

Frequency of maternal-fetal assessment

Frequency of maternal-fetal assessment

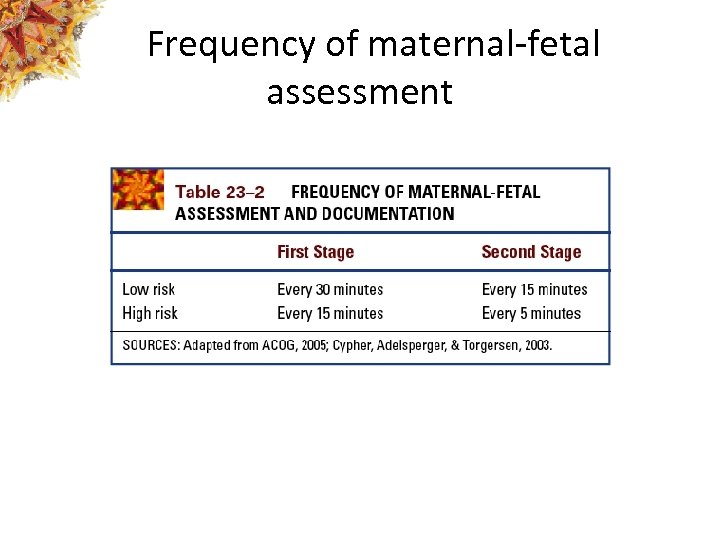

Contraction and labor progress

Contraction and labor progress

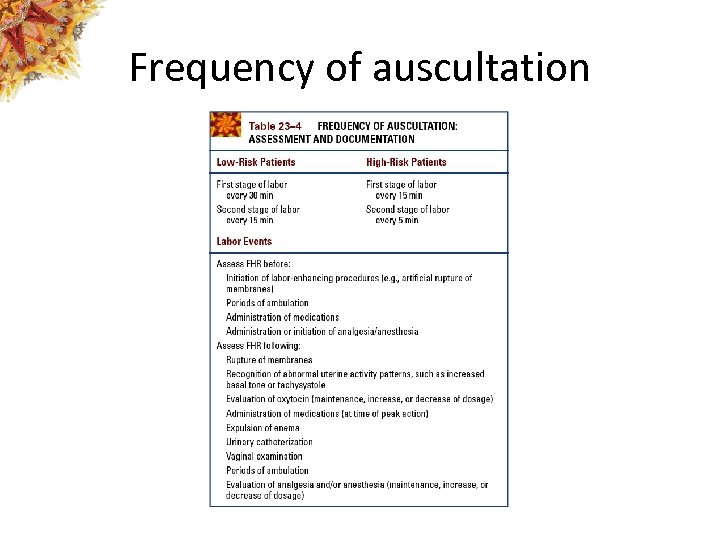

Frequency of auscultation

Frequency of auscultation

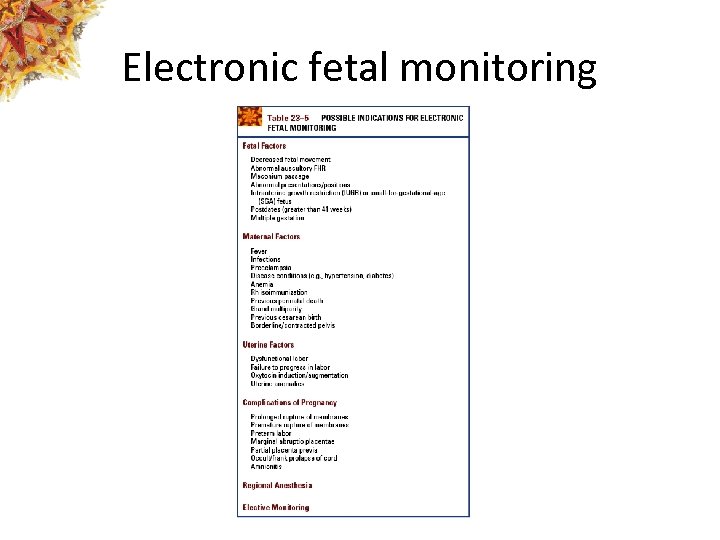

Electronic fetal monitoring

Electronic fetal monitoring

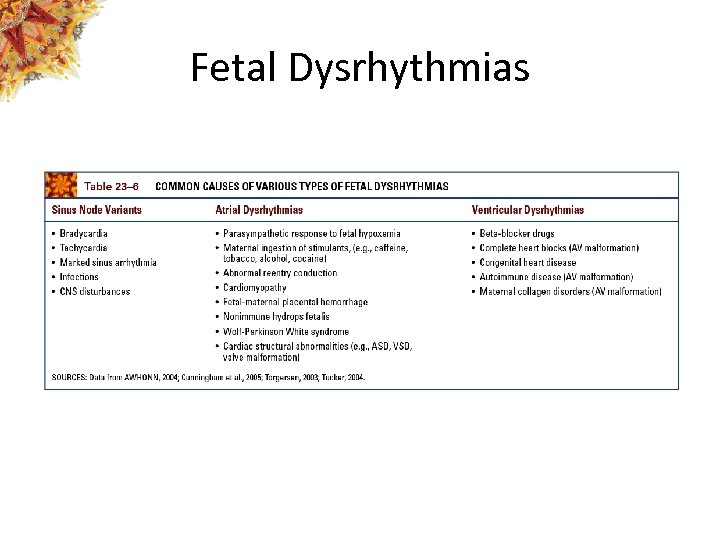

Fetal Dysrhythmias

Fetal Dysrhythmias

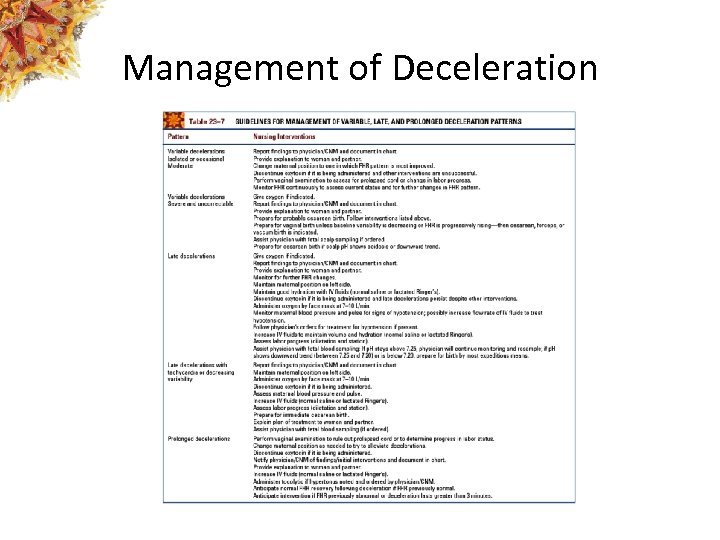

Management of Deceleration

Management of Deceleration

Evaluation of Fetal Monitoring: Uterine Contractions • Determine the uterine resting tone • Assess the contractions – What is the frequency? – What is the duration? – What is the intensity (if internal monitoring)?

Evaluation of Fetal Monitoring: Uterine Contractions • Determine the uterine resting tone • Assess the contractions – What is the frequency? – What is the duration? – What is the intensity (if internal monitoring)?

Evaluation of Fetal Monitoring: FHR • Determine the baseline • Determine FHR variability • Determine whether a sinusoidal pattern is present • Determine whethere are periodic changes

Evaluation of Fetal Monitoring: FHR • Determine the baseline • Determine FHR variability • Determine whether a sinusoidal pattern is present • Determine whethere are periodic changes

Nonreassuring Patterns • • • Variable decelerations Late decelerations of any magnitude Absence of variability Prolonged deceleration Severe (marked) bradycardia

Nonreassuring Patterns • • • Variable decelerations Late decelerations of any magnitude Absence of variability Prolonged deceleration Severe (marked) bradycardia

Nursing Interventions for Nonreassuring Patterns • • • Notify MD/Midwife and document Change position Increase IV fluids Provide oxygen Tocolytics Prepare for cesarean or vacuum birth

Nursing Interventions for Nonreassuring Patterns • • • Notify MD/Midwife and document Change position Increase IV fluids Provide oxygen Tocolytics Prepare for cesarean or vacuum birth

Scalp Stimulation • Direct stimulation to fetal scalp to elicit an acceleration • Uncompromised fetuses will elicit acceleration of at least 15 bpm for 15 • seconds

Scalp Stimulation • Direct stimulation to fetal scalp to elicit an acceleration • Uncompromised fetuses will elicit acceleration of at least 15 bpm for 15 • seconds

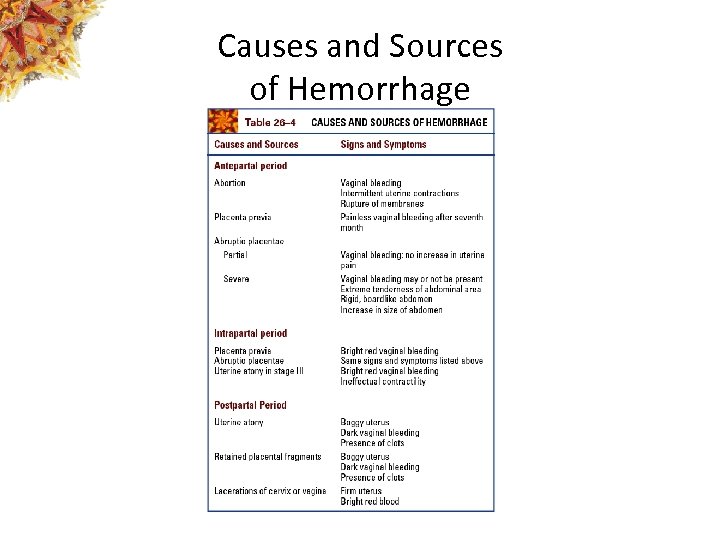

Causes and Sources of Hemorrhage

Causes and Sources of Hemorrhage

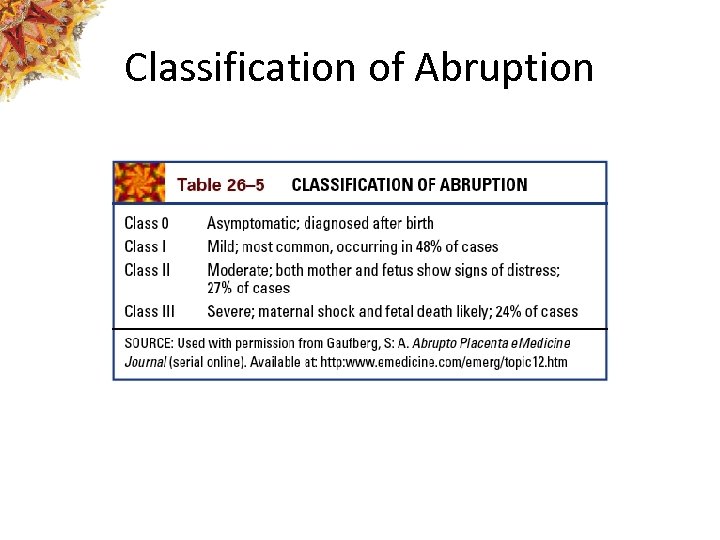

Classification of Abruption

Classification of Abruption

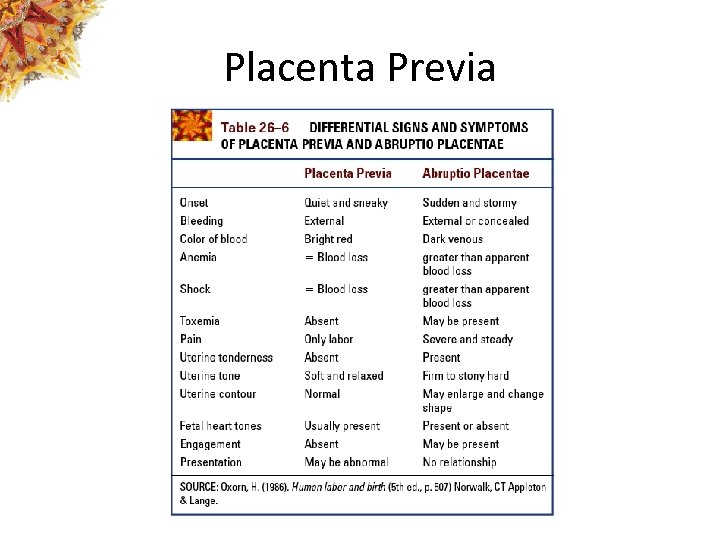

Placenta Previa

Placenta Previa

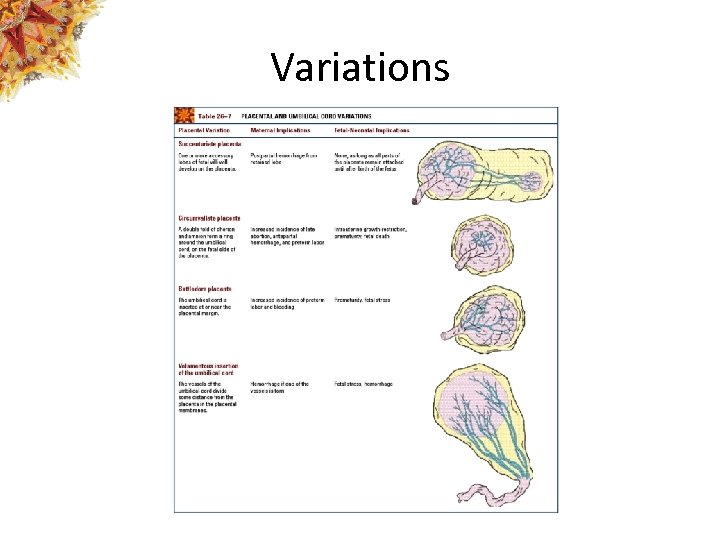

Variations

Variations

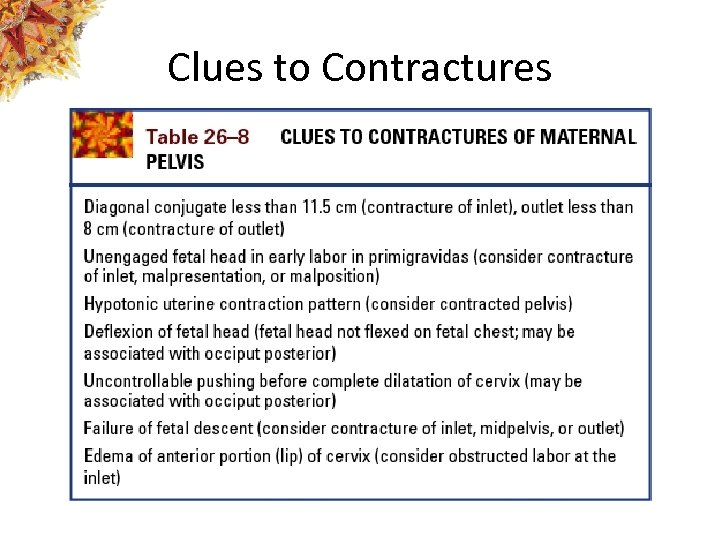

Clues to Contractures

Clues to Contractures

Dysfunctional Labor Patterns • Dystocia • Hypertonic contractions • Hypotonic contractions

Dysfunctional Labor Patterns • Dystocia • Hypertonic contractions • Hypotonic contractions

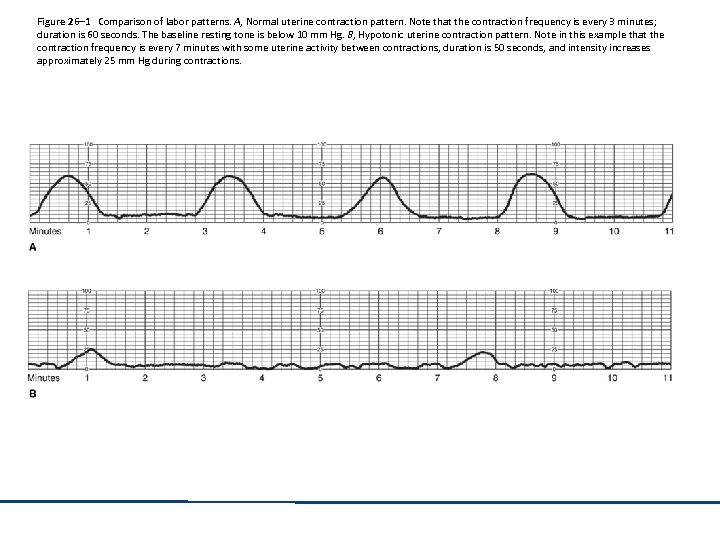

Figure 26– 1 Comparison of labor patterns. A, Normal uterine contraction pattern. Note that the contraction frequency is every 3 minutes; duration is 60 seconds. The baseline resting tone is below 10 mm Hg. B, Hypotonic uterine contraction pattern. Note in this example that the contraction frequency is every 7 minutes with some uterine activity between contractions, duration is 50 seconds, and intensity increases approximately 25 mm Hg during contractions.

Figure 26– 1 Comparison of labor patterns. A, Normal uterine contraction pattern. Note that the contraction frequency is every 3 minutes; duration is 60 seconds. The baseline resting tone is below 10 mm Hg. B, Hypotonic uterine contraction pattern. Note in this example that the contraction frequency is every 7 minutes with some uterine activity between contractions, duration is 50 seconds, and intensity increases approximately 25 mm Hg during contractions.

Precipitous Birth: Maternal Risks • Abruptio placentae • Cervical, vaginal, or perineal lacerations • Postpartum hemorrhage

Precipitous Birth: Maternal Risks • Abruptio placentae • Cervical, vaginal, or perineal lacerations • Postpartum hemorrhage

Impact of Post-term Pregnancy: Maternal • • • Perineal damage Hemorrhage Increased risk of cesarean birth Anxiety Emotional fatigue Persistence of normal discomforts

Impact of Post-term Pregnancy: Maternal • • • Perineal damage Hemorrhage Increased risk of cesarean birth Anxiety Emotional fatigue Persistence of normal discomforts

Impact of Post-term Pregnancy: Fetal • • • Decreased perfusion Oligohydramnios Small-for-gestational-age (SGA) Macrosomia Increased risk for meconium staining

Impact of Post-term Pregnancy: Fetal • • • Decreased perfusion Oligohydramnios Small-for-gestational-age (SGA) Macrosomia Increased risk for meconium staining

Malposition/Malpresentation • Persistent occiput-posterior (OP) position • Brow presentation • Face presentation

Malposition/Malpresentation • Persistent occiput-posterior (OP) position • Brow presentation • Face presentation

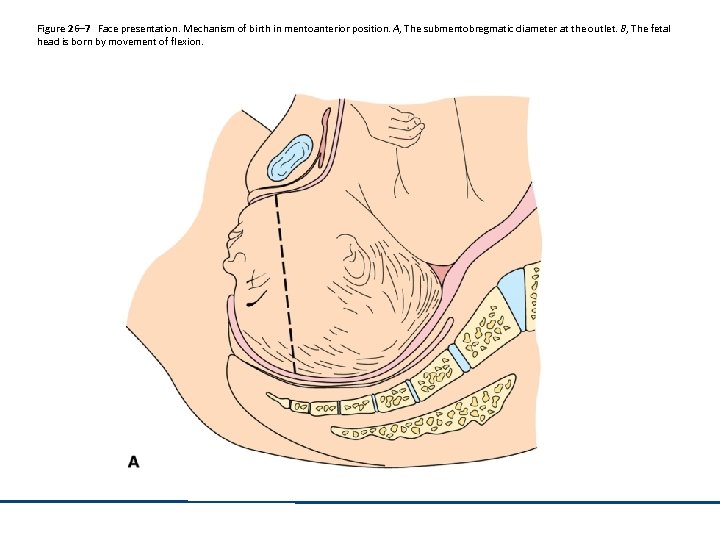

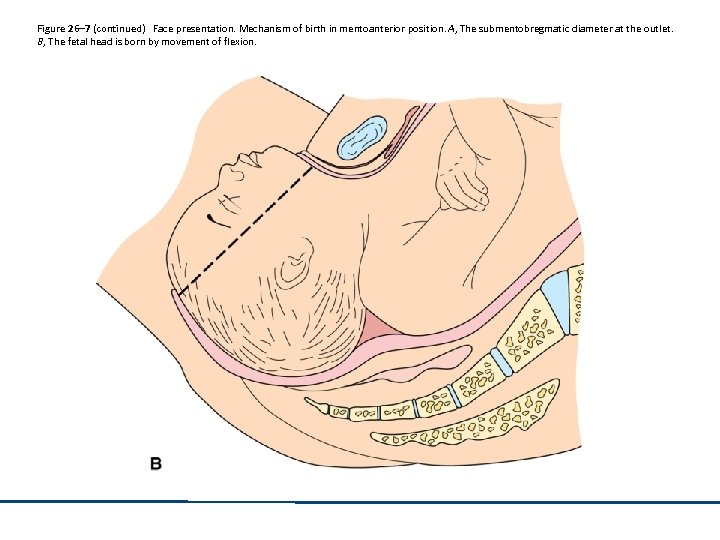

Figure 26– 7 Face presentation. Mechanism of birth in mentoanterior position. A, The submentobregmatic diameter at the outlet. B, The fetal head is born by movement of flexion.

Figure 26– 7 Face presentation. Mechanism of birth in mentoanterior position. A, The submentobregmatic diameter at the outlet. B, The fetal head is born by movement of flexion.

Figure 26– 7 (continued) Face presentation. Mechanism of birth in mentoanterior position. A, The submentobregmatic diameter at the outlet. B, The fetal head is born by movement of flexion.

Figure 26– 7 (continued) Face presentation. Mechanism of birth in mentoanterior position. A, The submentobregmatic diameter at the outlet. B, The fetal head is born by movement of flexion.

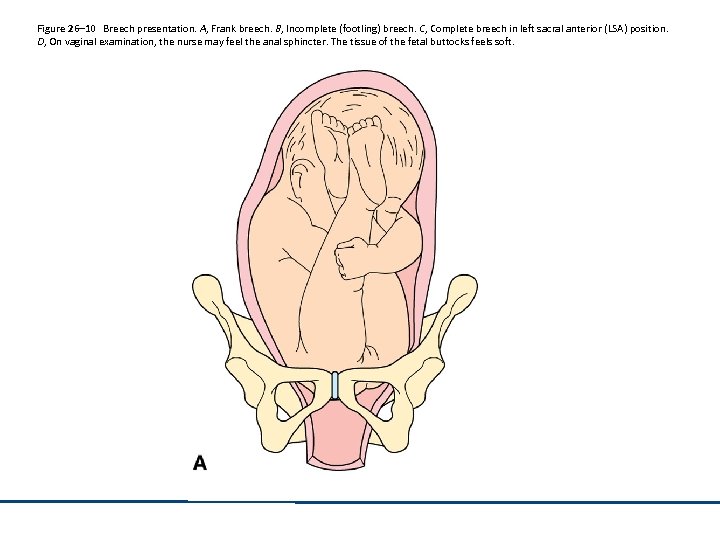

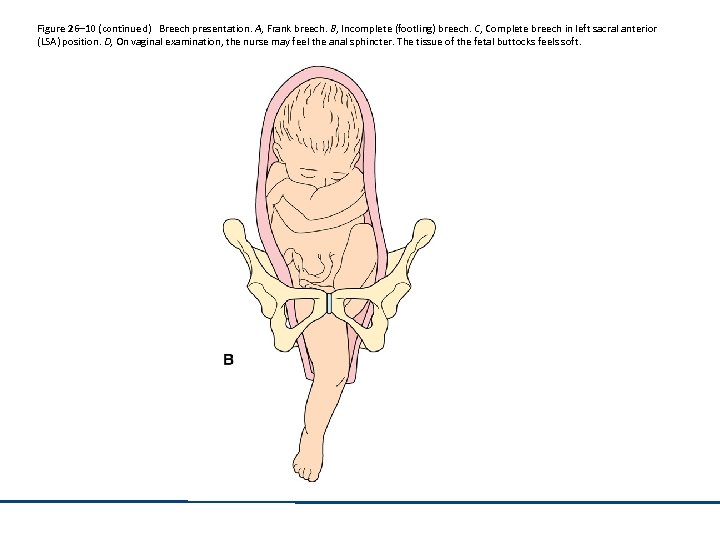

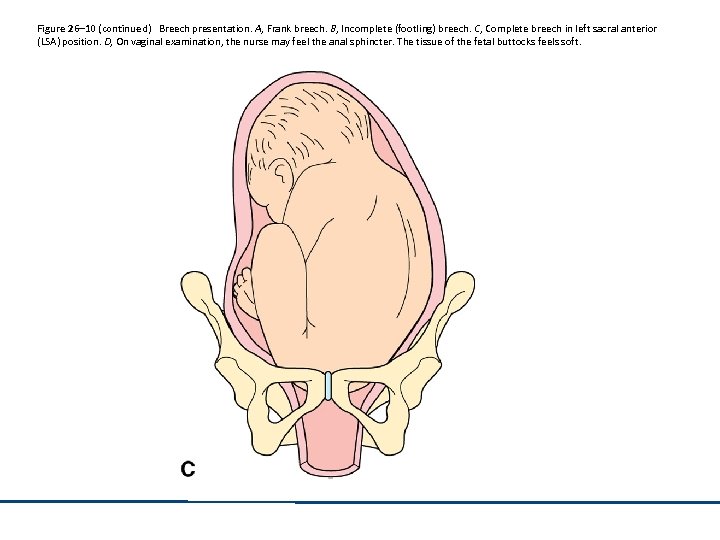

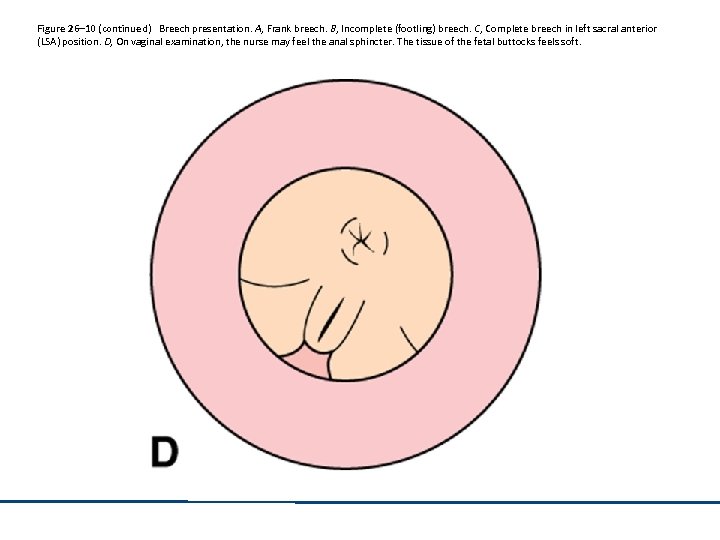

Breech Presentation: Types • Frank • Single or double footling (incomplete) • Complete

Breech Presentation: Types • Frank • Single or double footling (incomplete) • Complete

Figure 26– 10 Breech presentation. A, Frank breech. B, Incomplete (footling) breech. C, Complete breech in left sacral anterior (LSA) position. D, On vaginal examination, the nurse may feel the anal sphincter. The tissue of the fetal buttocks feels soft.

Figure 26– 10 Breech presentation. A, Frank breech. B, Incomplete (footling) breech. C, Complete breech in left sacral anterior (LSA) position. D, On vaginal examination, the nurse may feel the anal sphincter. The tissue of the fetal buttocks feels soft.

Figure 26– 10 (continued) Breech presentation. A, Frank breech. B, Incomplete (footling) breech. C, Complete breech in left sacral anterior (LSA) position. D, On vaginal examination, the nurse may feel the anal sphincter. The tissue of the fetal buttocks feels soft.

Figure 26– 10 (continued) Breech presentation. A, Frank breech. B, Incomplete (footling) breech. C, Complete breech in left sacral anterior (LSA) position. D, On vaginal examination, the nurse may feel the anal sphincter. The tissue of the fetal buttocks feels soft.

Figure 26– 10 (continued) Breech presentation. A, Frank breech. B, Incomplete (footling) breech. C, Complete breech in left sacral anterior (LSA) position. D, On vaginal examination, the nurse may feel the anal sphincter. The tissue of the fetal buttocks feels soft.

Figure 26– 10 (continued) Breech presentation. A, Frank breech. B, Incomplete (footling) breech. C, Complete breech in left sacral anterior (LSA) position. D, On vaginal examination, the nurse may feel the anal sphincter. The tissue of the fetal buttocks feels soft.

Figure 26– 10 (continued) Breech presentation. A, Frank breech. B, Incomplete (footling) breech. C, Complete breech in left sacral anterior (LSA) position. D, On vaginal examination, the nurse may feel the anal sphincter. The tissue of the fetal buttocks feels soft.

Figure 26– 10 (continued) Breech presentation. A, Frank breech. B, Incomplete (footling) breech. C, Complete breech in left sacral anterior (LSA) position. D, On vaginal examination, the nurse may feel the anal sphincter. The tissue of the fetal buttocks feels soft.

Breech Presentation: Risks • • Head trauma Increased risk for infant mortality Neonatal complications Cord prolapse

Breech Presentation: Risks • • Head trauma Increased risk for infant mortality Neonatal complications Cord prolapse

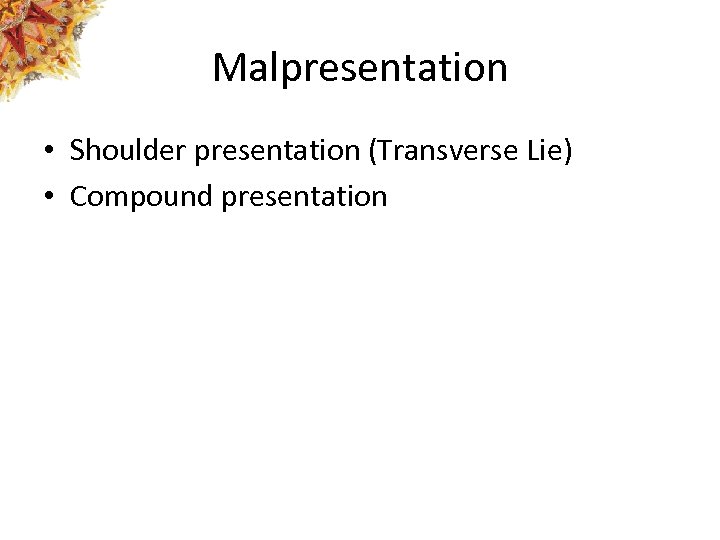

Malpresentation • Shoulder presentation (Transverse Lie) • Compound presentation

Malpresentation • Shoulder presentation (Transverse Lie) • Compound presentation

Figure 26– 11 Transverse lie. A, Shoulder presentation. B, On vaginal examination, the nurse may feel the acromion process as the fetal presenting part.

Figure 26– 11 Transverse lie. A, Shoulder presentation. B, On vaginal examination, the nurse may feel the acromion process as the fetal presenting part.

Macrosomia Risks • • • Dysfunctional labor Uterine rupture Perineal lacerations Postpartum hemorrhage Puerperal infection Shoulder dystocia

Macrosomia Risks • • • Dysfunctional labor Uterine rupture Perineal lacerations Postpartum hemorrhage Puerperal infection Shoulder dystocia

Multiple Gestation: Pregnancy Risks • • • Spontaneous abortions Gestational diabetes Hypertension Acute fatty liver disease Pulmonary embolism Maternal anemia

Multiple Gestation: Pregnancy Risks • • • Spontaneous abortions Gestational diabetes Hypertension Acute fatty liver disease Pulmonary embolism Maternal anemia

Multiple Gestation: Pregnancy Risks (continued) • • Hydramnios PROM Incompetent cervix IUGR

Multiple Gestation: Pregnancy Risks (continued) • • Hydramnios PROM Incompetent cervix IUGR

Multiple Gestation: Labor Risks • • • Preterm labor Uterine dysfunction Abnormal fetal presentations Instrumental or cesarean birth Postpartum hemorrhage

Multiple Gestation: Labor Risks • • • Preterm labor Uterine dysfunction Abnormal fetal presentations Instrumental or cesarean birth Postpartum hemorrhage

Multiple Gestation: Physical Discomfort • Shortness of breath and/or dyspnea on exertion • Backaches • Round ligament pain • Heartburn • Pelvic or suprapubic pressure • Pedal edema

Multiple Gestation: Physical Discomfort • Shortness of breath and/or dyspnea on exertion • Backaches • Round ligament pain • Heartburn • Pelvic or suprapubic pressure • Pedal edema

Abruptio Placentae: Causes • • • Maternal hypertension Domestic violence Abdominal trauma Presence of fibroids Uterine overdistension Fetal growth restriction

Abruptio Placentae: Causes • • • Maternal hypertension Domestic violence Abdominal trauma Presence of fibroids Uterine overdistension Fetal growth restriction

Abruptio Placentae: Causes (continued) • • • Advanced maternal age Alcohol consumption Cocaine use Short umbilical cord High parity

Abruptio Placentae: Causes (continued) • • • Advanced maternal age Alcohol consumption Cocaine use Short umbilical cord High parity

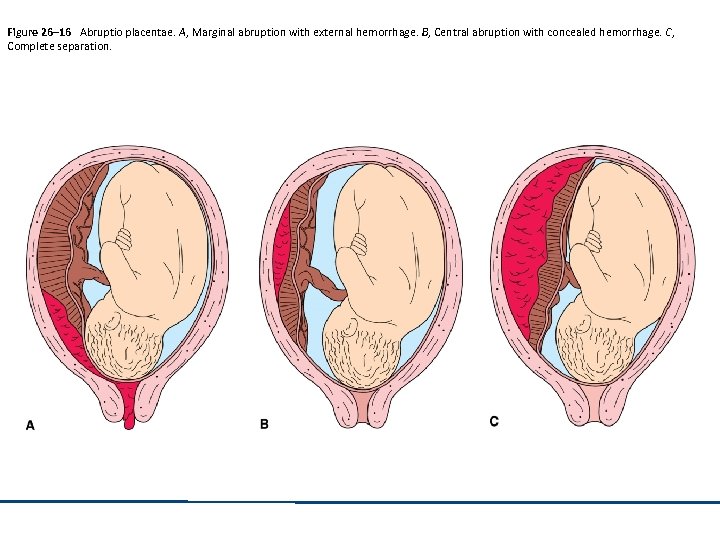

Abruptio Placentae: Types • Marginal • Central • Complete

Abruptio Placentae: Types • Marginal • Central • Complete

Figure 26– 16 Abruptio placentae. A, Marginal abruption with external hemorrhage. B, Central abruption with concealed hemorrhage. C, Complete separation.

Figure 26– 16 Abruptio placentae. A, Marginal abruption with external hemorrhage. B, Central abruption with concealed hemorrhage. C, Complete separation.

Placenta Previa: Causes Multiparity Increasing age Placenta accreta Defective development of blood vessels in the decidua • Prior cesarean birth • Smoking • •

Placenta Previa: Causes Multiparity Increasing age Placenta accreta Defective development of blood vessels in the decidua • Prior cesarean birth • Smoking • •

Placenta Previa: Causes (continued) • Recent spontaneous or induced abortion • Large placenta

Placenta Previa: Causes (continued) • Recent spontaneous or induced abortion • Large placenta

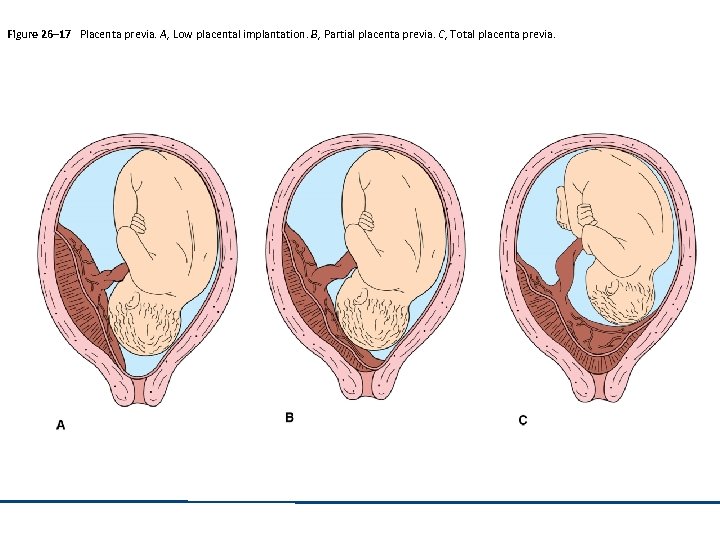

Placenta Previa: Types • • Total Partial Marginal Low-lying

Placenta Previa: Types • • Total Partial Marginal Low-lying

Figure 26– 17 Placenta previa. A, Low placental implantation. B, Partial placenta previa. C, Total placenta previa.

Figure 26– 17 Placenta previa. A, Low placental implantation. B, Partial placenta previa. C, Total placenta previa.

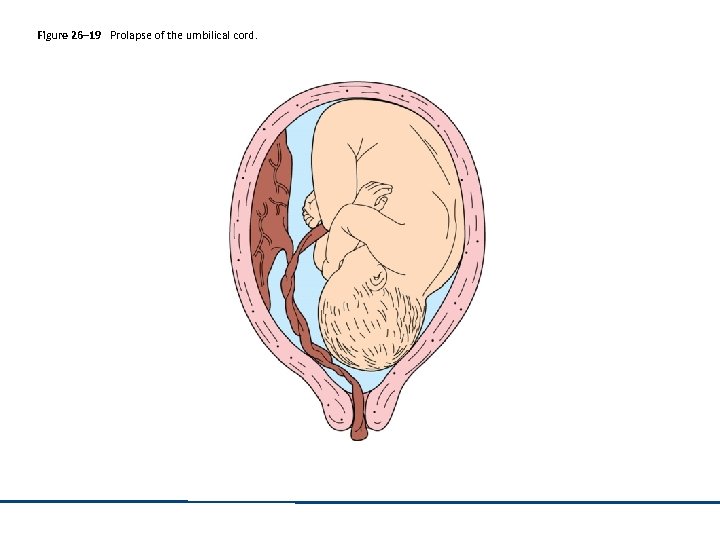

Umbilical Cord Complications • • • Succenturiate placenta Circumvallate placenta Battledore placenta Prolapsed umbilical cord Velamentous insertion

Umbilical Cord Complications • • • Succenturiate placenta Circumvallate placenta Battledore placenta Prolapsed umbilical cord Velamentous insertion

Figure 26– 19 Prolapse of the umbilical cord.

Figure 26– 19 Prolapse of the umbilical cord.

Umbilical Cord Complications (continued) • Vasa previa • Cord length problems

Umbilical Cord Complications (continued) • Vasa previa • Cord length problems

Amniotic Fluid Complications • Amniotic fluid embolism • Hydramnios (polyhydramnios) • Oligohydramnios

Amniotic Fluid Complications • Amniotic fluid embolism • Hydramnios (polyhydramnios) • Oligohydramnios

Pelvic Complications • Cephalopelvic disproportion – Uterine rupture – Maternal soft tissue damage – Cord prolapse – Extreme molding – Trauma to fetal skull and CNS

Pelvic Complications • Cephalopelvic disproportion – Uterine rupture – Maternal soft tissue damage – Cord prolapse – Extreme molding – Trauma to fetal skull and CNS

Third and Fourth Stage Complications • Retained placenta • Lacerations • Placental adherence – Accreta – Increta – Percreta

Third and Fourth Stage Complications • Retained placenta • Lacerations • Placental adherence – Accreta – Increta – Percreta

Impact of Procedures on Childbearing Woman • Disappointment • Guilt • Conflict between expectation and need for intervention

Impact of Procedures on Childbearing Woman • Disappointment • Guilt • Conflict between expectation and need for intervention

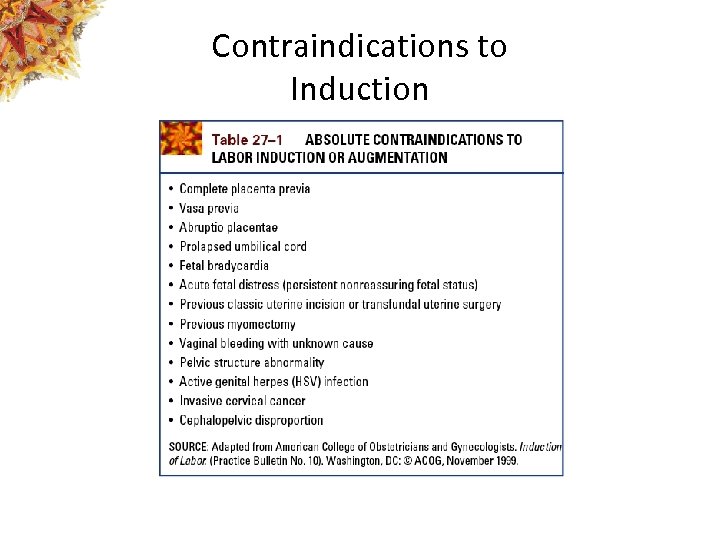

Contraindications to Induction

Contraindications to Induction

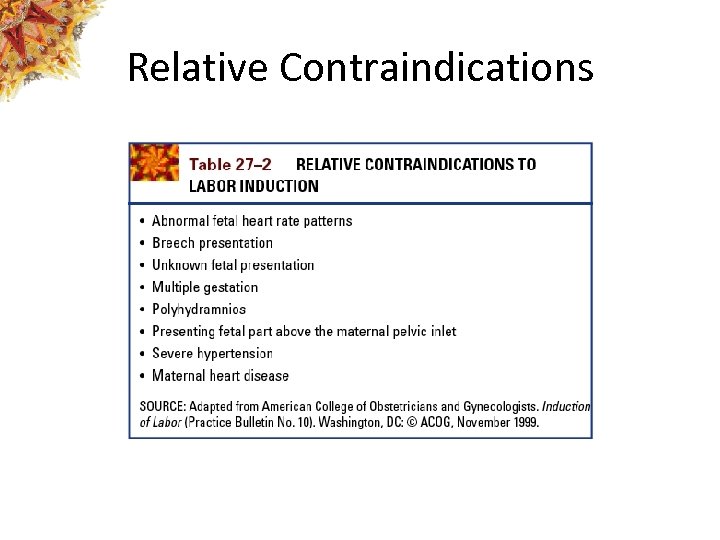

Relative Contraindications

Relative Contraindications

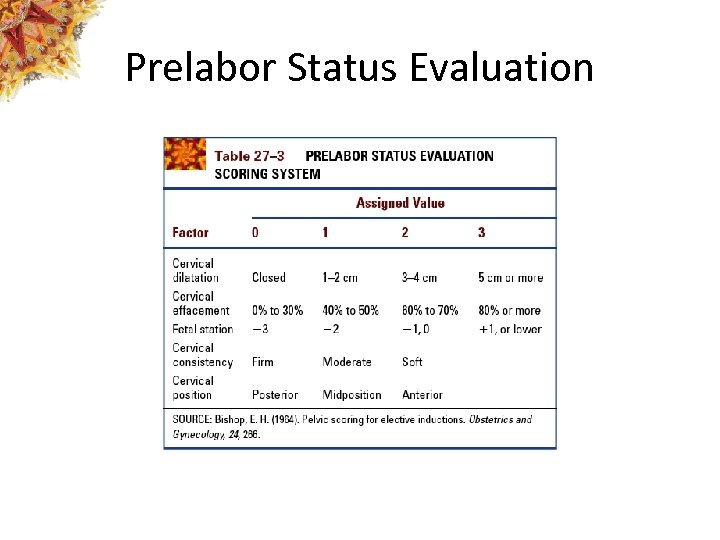

Prelabor Status Evaluation

Prelabor Status Evaluation

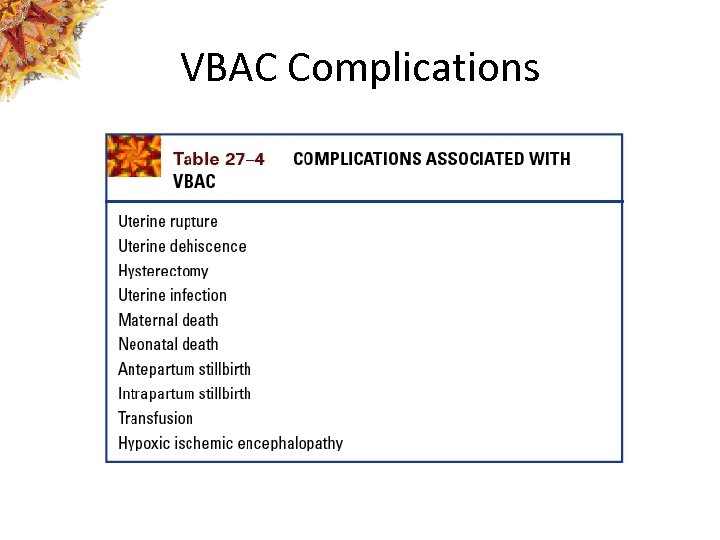

VBAC Complications

VBAC Complications

Version • External Cephalic Version (ECV) • Podalic Version (Internal)

Version • External Cephalic Version (ECV) • Podalic Version (Internal)

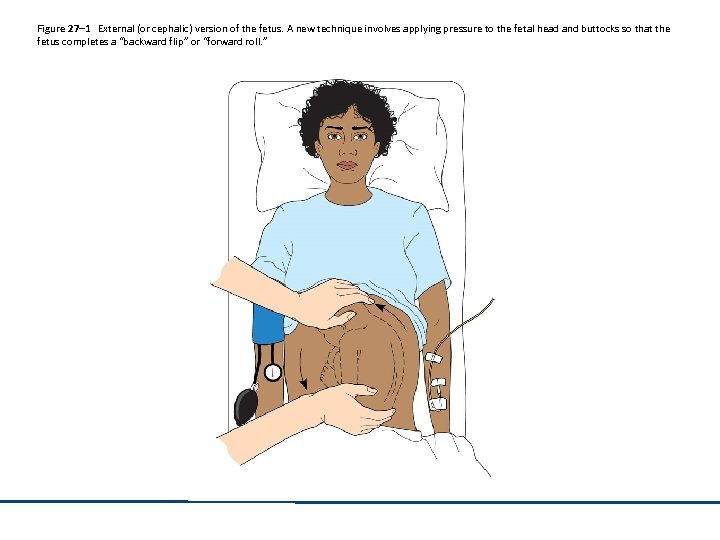

Figure 27– 1 External (or cephalic) version of the fetus. A new technique involves applying pressure to the fetal head and buttocks so that the fetus completes a “backward flip” or “forward roll. ”

Figure 27– 1 External (or cephalic) version of the fetus. A new technique involves applying pressure to the fetal head and buttocks so that the fetus completes a “backward flip” or “forward roll. ”

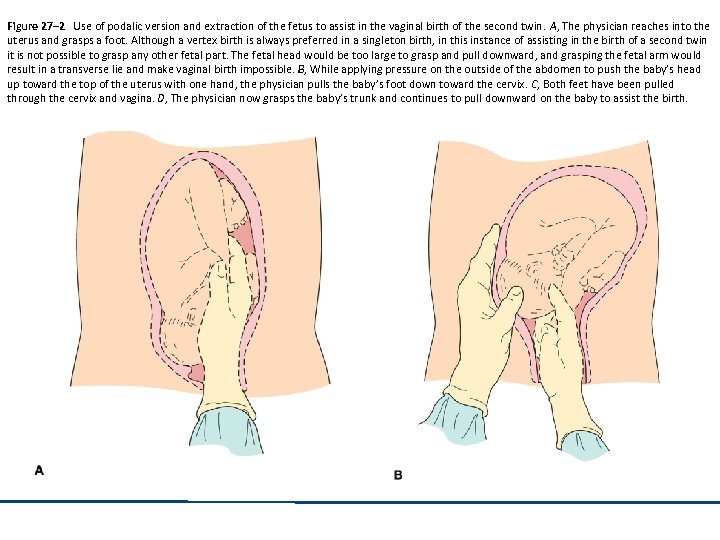

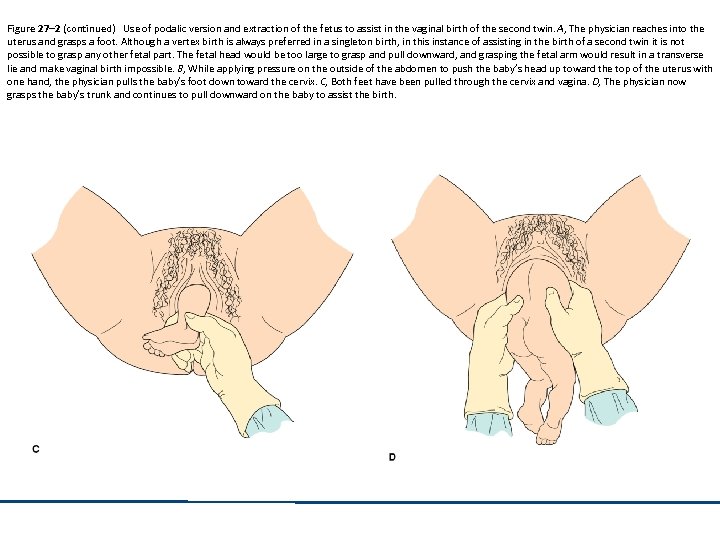

Figure 27– 2 Use of podalic version and extraction of the fetus to assist in the vaginal birth of the second twin. A, The physician reaches into the uterus and grasps a foot. Although a vertex birth is always preferred in a singleton birth, in this instance of assisting in the birth of a second twin it is not possible to grasp any other fetal part. The fetal head would be too large to grasp and pull downward, and grasping the fetal arm would result in a transverse lie and make vaginal birth impossible. B, While applying pressure on the outside of the abdomen to push the baby’s head up toward the top of the uterus with one hand, the physician pulls the baby’s foot down toward the cervix. C, Both feet have been pulled through the cervix and vagina. D, The physician now grasps the baby’s trunk and continues to pull downward on the baby to assist the birth.

Figure 27– 2 Use of podalic version and extraction of the fetus to assist in the vaginal birth of the second twin. A, The physician reaches into the uterus and grasps a foot. Although a vertex birth is always preferred in a singleton birth, in this instance of assisting in the birth of a second twin it is not possible to grasp any other fetal part. The fetal head would be too large to grasp and pull downward, and grasping the fetal arm would result in a transverse lie and make vaginal birth impossible. B, While applying pressure on the outside of the abdomen to push the baby’s head up toward the top of the uterus with one hand, the physician pulls the baby’s foot down toward the cervix. C, Both feet have been pulled through the cervix and vagina. D, The physician now grasps the baby’s trunk and continues to pull downward on the baby to assist the birth.

Figure 27– 2 (continued) Use of podalic version and extraction of the fetus to assist in the vaginal birth of the second twin. A, The physician reaches into the uterus and grasps a foot. Although a vertex birth is always preferred in a singleton birth, in this instance of assisting in the birth of a second twin it is not possible to grasp any other fetal part. The fetal head would be too large to grasp and pull downward, and grasping the fetal arm would result in a transverse lie and make vaginal birth impossible. B, While applying pressure on the outside of the abdomen to push the baby’s head up toward the top of the uterus with one hand, the physician pulls the baby’s foot down toward the cervix. C, Both feet have been pulled through the cervix and vagina. D, The physician now grasps the baby’s trunk and continues to pull downward on the baby to assist the birth.

Figure 27– 2 (continued) Use of podalic version and extraction of the fetus to assist in the vaginal birth of the second twin. A, The physician reaches into the uterus and grasps a foot. Although a vertex birth is always preferred in a singleton birth, in this instance of assisting in the birth of a second twin it is not possible to grasp any other fetal part. The fetal head would be too large to grasp and pull downward, and grasping the fetal arm would result in a transverse lie and make vaginal birth impossible. B, While applying pressure on the outside of the abdomen to push the baby’s head up toward the top of the uterus with one hand, the physician pulls the baby’s foot down toward the cervix. C, Both feet have been pulled through the cervix and vagina. D, The physician now grasps the baby’s trunk and continues to pull downward on the baby to assist the birth.

Nursing Management • • • Maternal/fetal assessments NST Lab studies Psychological support Education Monitor VS

Nursing Management • • • Maternal/fetal assessments NST Lab studies Psychological support Education Monitor VS

Nursing Management (continued) • EFM • Mediation administration – Beta-mimetics, Rho. GAM

Nursing Management (continued) • EFM • Mediation administration – Beta-mimetics, Rho. GAM

Uses of Amniotomy • Labor induction • Labor augmentation • Allow access to fetus and uterus to – Apply an internal fetal heart monitoring scalp electrode – Insert an intrauterine pressure catheter – Obtain a fetal scalp blood sample

Uses of Amniotomy • Labor induction • Labor augmentation • Allow access to fetus and uterus to – Apply an internal fetal heart monitoring scalp electrode – Insert an intrauterine pressure catheter – Obtain a fetal scalp blood sample

Cervical Ripening: Prostaglandin E 2 • Advantages – Cervical ripening – Shorter labor – Lower requirements for oxytocin during labor induction – Vaginal birth is achieved within 24 hours for most women – Incidence of cesarean birth is reduced

Cervical Ripening: Prostaglandin E 2 • Advantages – Cervical ripening – Shorter labor – Lower requirements for oxytocin during labor induction – Vaginal birth is achieved within 24 hours for most women – Incidence of cesarean birth is reduced

Cervical Ripening: Prostaglandin E 2 (continued) • Risks – Uterine hyperstimulation – Nonreassuring fetal status – Higher incidence of postpartum hemorrhage – Uterine rupture

Cervical Ripening: Prostaglandin E 2 (continued) • Risks – Uterine hyperstimulation – Nonreassuring fetal status – Higher incidence of postpartum hemorrhage – Uterine rupture

Labor Induction: Stripping Membranes • Advantages – Labor usually occurs in 24 -48 hours • Disadvantages – Can be painful – Uterine contractions – Bloody discharge

Labor Induction: Stripping Membranes • Advantages – Labor usually occurs in 24 -48 hours • Disadvantages – Can be painful – Uterine contractions – Bloody discharge

Labor Induction: Oxytocin • Risks – Hyperstimulation of the uterus – Uterine rupture – Water intoxication – Nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns

Labor Induction: Oxytocin • Risks – Hyperstimulation of the uterus – Uterine rupture – Water intoxication – Nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns

Labor Induction: Natural Methods • Sexual intercourse/lovemaking • Self or partner stimulation of the woman’s nipples and breasts • Use of herbs – Blue/black cohosh – Evening primrose oil – Red raspberry leaves

Labor Induction: Natural Methods • Sexual intercourse/lovemaking • Self or partner stimulation of the woman’s nipples and breasts • Use of herbs – Blue/black cohosh – Evening primrose oil – Red raspberry leaves

Labor Induction: Natural Methods (continued) • Use of homeopathic solutions – Caulophyllum or pulsatilla – Castor oil, enemas – Acupressure/acupuncture • Mechanical dilatation with balloon catheter

Labor Induction: Natural Methods (continued) • Use of homeopathic solutions – Caulophyllum or pulsatilla – Castor oil, enemas – Acupressure/acupuncture • Mechanical dilatation with balloon catheter

Amnioinfusion • Prevent the possibility of variable decelerations • Treat nonperiodic decelerations • Meconium dilution

Amnioinfusion • Prevent the possibility of variable decelerations • Treat nonperiodic decelerations • Meconium dilution

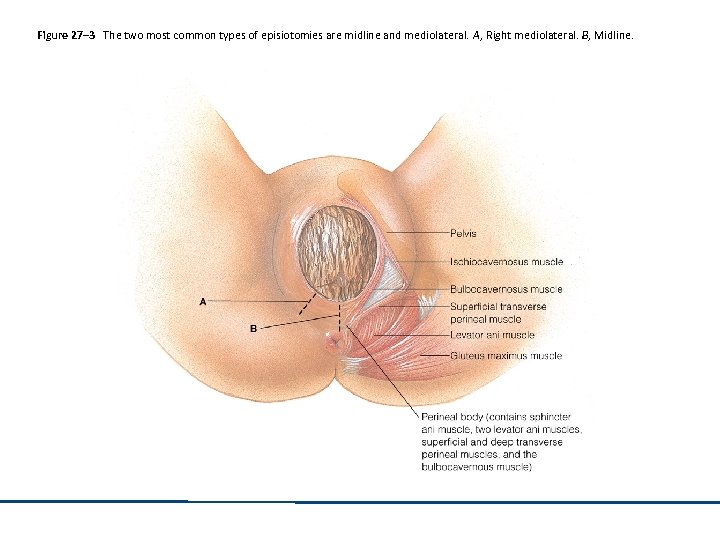

Episiotomy • Types – Midline – Mediolateral

Episiotomy • Types – Midline – Mediolateral

Figure 27– 3 The two most common types of episiotomies are midline and mediolateral. A, Right mediolateral. B, Midline.

Figure 27– 3 The two most common types of episiotomies are midline and mediolateral. A, Right mediolateral. B, Midline.

Nursing Management • • • Support Assist with communication of woman’s needs Pain relief measures Assessment Education

Nursing Management • • • Support Assist with communication of woman’s needs Pain relief measures Assessment Education

Forceps-Assisted Birth: Maternal Indications • Heart disease • Acute pulmonary edema or pulmonary compromise • Certain neurological conditions • Intrapartal infection • Prolonged second stage • Exhaustion

Forceps-Assisted Birth: Maternal Indications • Heart disease • Acute pulmonary edema or pulmonary compromise • Certain neurological conditions • Intrapartal infection • Prolonged second stage • Exhaustion

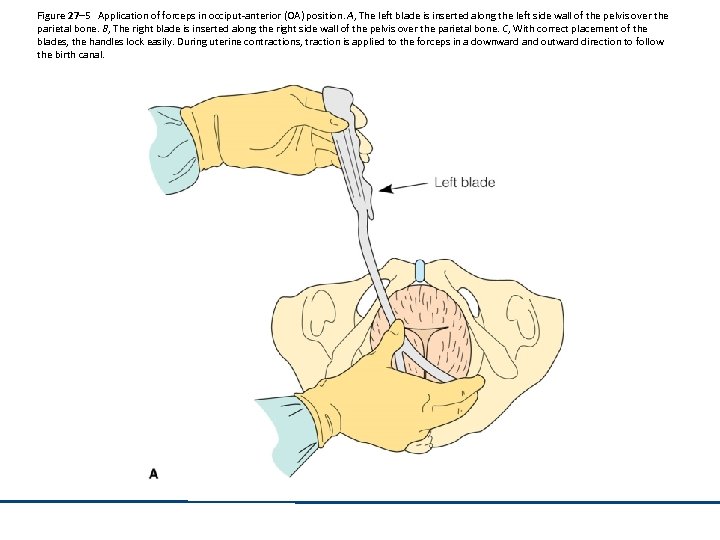

Figure 27– 5 Application of forceps in occiput-anterior (OA) position. A, The left blade is inserted along the left side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. B, The right blade is inserted along the right side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. C, With correct placement of the blades, the handles lock easily. During uterine contractions, traction is applied to the forceps in a downward and outward direction to follow the birth canal.

Figure 27– 5 Application of forceps in occiput-anterior (OA) position. A, The left blade is inserted along the left side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. B, The right blade is inserted along the right side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. C, With correct placement of the blades, the handles lock easily. During uterine contractions, traction is applied to the forceps in a downward and outward direction to follow the birth canal.

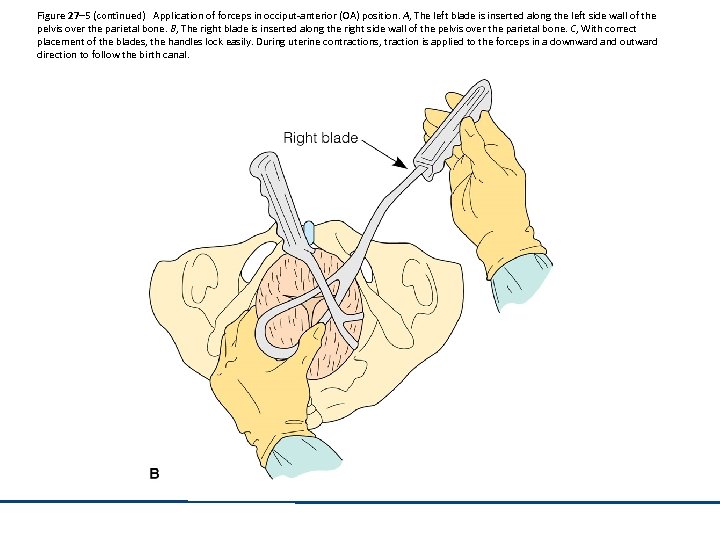

Figure 27– 5 (continued) Application of forceps in occiput-anterior (OA) position. A, The left blade is inserted along the left side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. B, The right blade is inserted along the right side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. C, With correct placement of the blades, the handles lock easily. During uterine contractions, traction is applied to the forceps in a downward and outward direction to follow the birth canal.

Figure 27– 5 (continued) Application of forceps in occiput-anterior (OA) position. A, The left blade is inserted along the left side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. B, The right blade is inserted along the right side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. C, With correct placement of the blades, the handles lock easily. During uterine contractions, traction is applied to the forceps in a downward and outward direction to follow the birth canal.

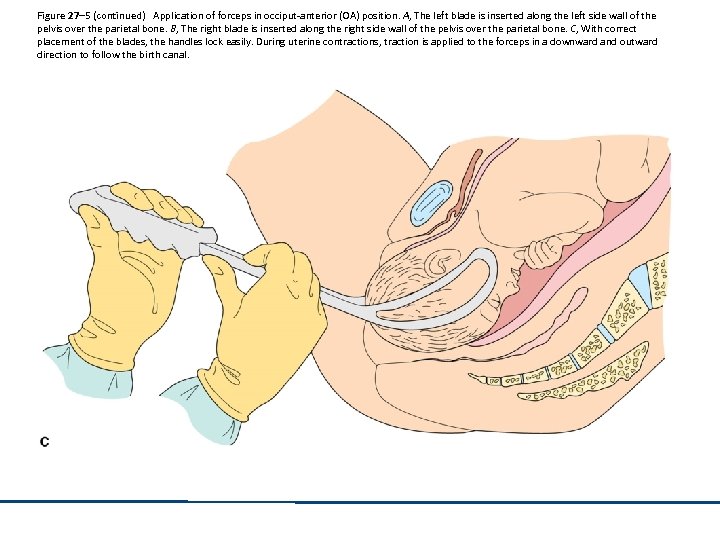

Figure 27– 5 (continued) Application of forceps in occiput-anterior (OA) position. A, The left blade is inserted along the left side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. B, The right blade is inserted along the right side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. C, With correct placement of the blades, the handles lock easily. During uterine contractions, traction is applied to the forceps in a downward and outward direction to follow the birth canal.

Figure 27– 5 (continued) Application of forceps in occiput-anterior (OA) position. A, The left blade is inserted along the left side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. B, The right blade is inserted along the right side wall of the pelvis over the parietal bone. C, With correct placement of the blades, the handles lock easily. During uterine contractions, traction is applied to the forceps in a downward and outward direction to follow the birth canal.

Forceps-Assisted Birth: Fetal Indications • Premature placental separation • Prolapsed umbilical cord • Nonreassuring fetal status

Forceps-Assisted Birth: Fetal Indications • Premature placental separation • Prolapsed umbilical cord • Nonreassuring fetal status

Types of Forceps • Outlet forceps • Midforceps • Breech forceps

Types of Forceps • Outlet forceps • Midforceps • Breech forceps

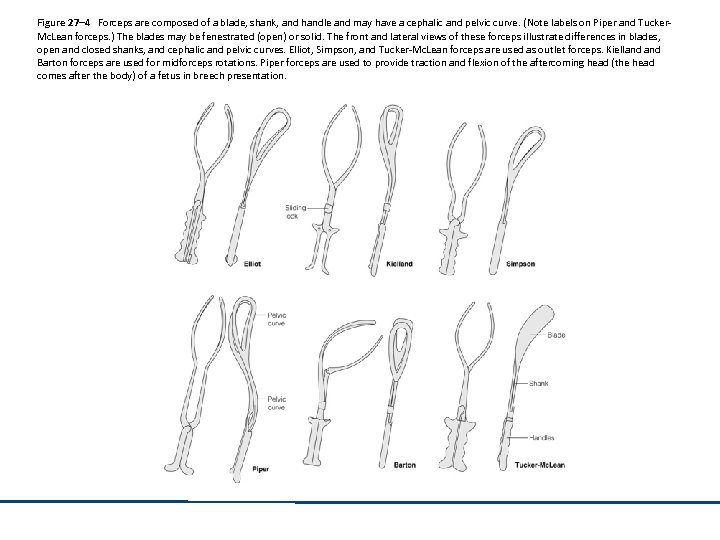

Figure 27– 4 Forceps are composed of a blade, shank, and handle and may have a cephalic and pelvic curve. (Note labels on Piper and Tucker. Mc. Lean forceps. ) The blades may be fenestrated (open) or solid. The front and lateral views of these forceps illustrate differences in blades, open and closed shanks, and cephalic and pelvic curves. Elliot, Simpson, and Tucker-Mc. Lean forceps are used as outlet forceps. Kielland Barton forceps are used for midforceps rotations. Piper forceps are used to provide traction and flexion of the aftercoming head (the head comes after the body) of a fetus in breech presentation.

Figure 27– 4 Forceps are composed of a blade, shank, and handle and may have a cephalic and pelvic curve. (Note labels on Piper and Tucker. Mc. Lean forceps. ) The blades may be fenestrated (open) or solid. The front and lateral views of these forceps illustrate differences in blades, open and closed shanks, and cephalic and pelvic curves. Elliot, Simpson, and Tucker-Mc. Lean forceps are used as outlet forceps. Kielland Barton forceps are used for midforceps rotations. Piper forceps are used to provide traction and flexion of the aftercoming head (the head comes after the body) of a fetus in breech presentation.

Fetal Risks • Ecchymosis, edema, or both along the sides of the face • Caput succedaneum or cephalhematoma • Transient facial paralysis • Low Apgar scores • Retinal hemorrhage • Corneal abrasions

Fetal Risks • Ecchymosis, edema, or both along the sides of the face • Caput succedaneum or cephalhematoma • Transient facial paralysis • Low Apgar scores • Retinal hemorrhage • Corneal abrasions

Fetal Risks (continued) • • Ocular trauma Other trauma (Erb’s palsy, fractured clavicle) Elevated neonatal bilirubin levels Prolonged infant hospital stay

Fetal Risks (continued) • • Ocular trauma Other trauma (Erb’s palsy, fractured clavicle) Elevated neonatal bilirubin levels Prolonged infant hospital stay

Maternal Risks Lacerations of the birth canal Periurethral lacerations Extension of a median episiotomy into the anus More likely to have a third- or fourth-degree laceration • Report more perineal pain and sexual problems in the postpartum period • Postpartum infections • •

Maternal Risks Lacerations of the birth canal Periurethral lacerations Extension of a median episiotomy into the anus More likely to have a third- or fourth-degree laceration • Report more perineal pain and sexual problems in the postpartum period • Postpartum infections • •

Maternal Risks (continued) • • • Cervical lacerations Prolonged hospital stay Urinary and rectal incontinence Anal sphincter injury Postpartum metritis

Maternal Risks (continued) • • • Cervical lacerations Prolonged hospital stay Urinary and rectal incontinence Anal sphincter injury Postpartum metritis

Nursing Management Explains procedure to woman Monitors contractions Informs physician/CNM of contraction Encourages woman to avoid pushing during contraction • Assessment of mother and her newborn • Reassurance • •

Nursing Management Explains procedure to woman Monitors contractions Informs physician/CNM of contraction Encourages woman to avoid pushing during contraction • Assessment of mother and her newborn • Reassurance • •

Indications for Vacuum Extraction Prolonged second stage of labor Nonreassuring heart rate pattern Used to relieve the woman of pushing effort When analgesia or fatigue interfere with ability to push effectively • Borderline CPD • •

Indications for Vacuum Extraction Prolonged second stage of labor Nonreassuring heart rate pattern Used to relieve the woman of pushing effort When analgesia or fatigue interfere with ability to push effectively • Borderline CPD • •

Vacuum Extraction Procedure • Procedure – Suction cup placed on fetal occiput – Pump is used to create suction – Traction is applied – Fetal head should descend with each contraction

Vacuum Extraction Procedure • Procedure – Suction cup placed on fetal occiput – Pump is used to create suction – Traction is applied – Fetal head should descend with each contraction

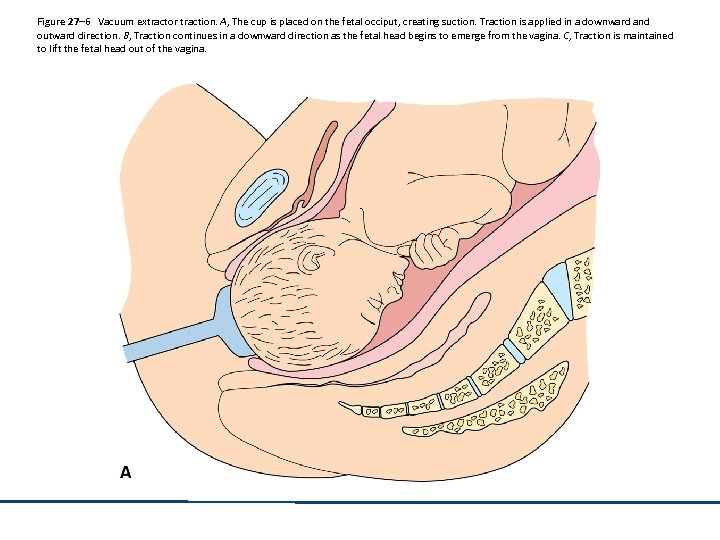

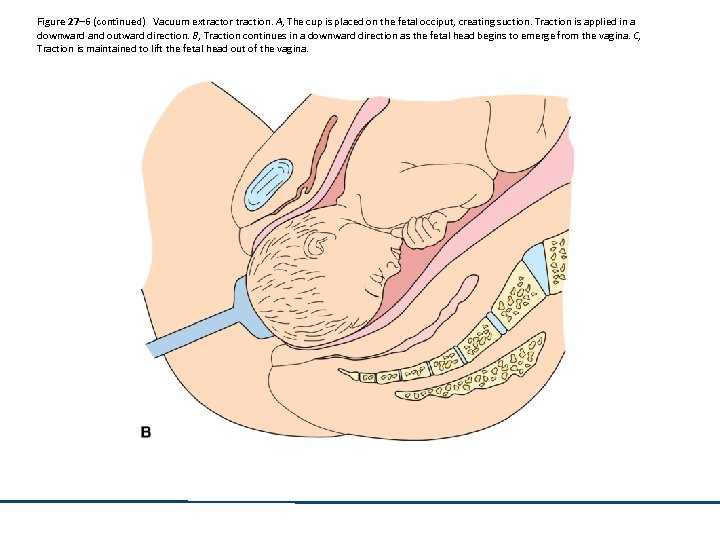

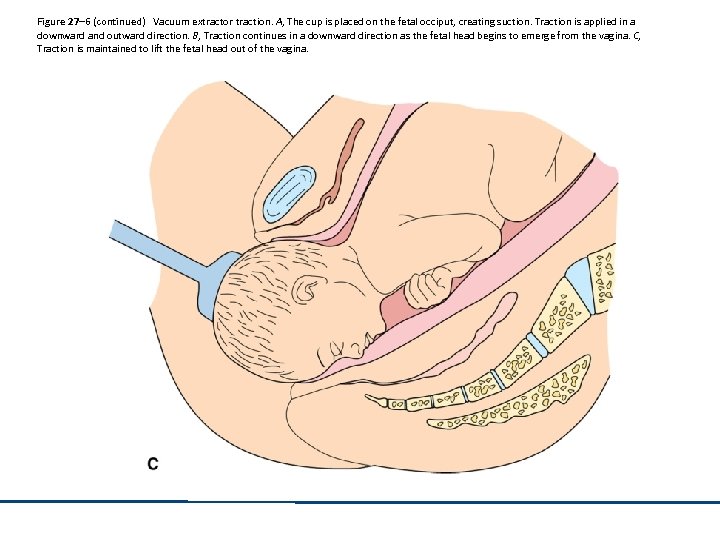

Figure 27– 6 Vacuum extractor traction. A, The cup is placed on the fetal occiput, creating suction. Traction is applied in a downward and outward direction. B, Traction continues in a downward direction as the fetal head begins to emerge from the vagina. C, Traction is maintained to lift the fetal head out of the vagina.

Figure 27– 6 Vacuum extractor traction. A, The cup is placed on the fetal occiput, creating suction. Traction is applied in a downward and outward direction. B, Traction continues in a downward direction as the fetal head begins to emerge from the vagina. C, Traction is maintained to lift the fetal head out of the vagina.

Figure 27– 6 (continued) Vacuum extractor traction. A, The cup is placed on the fetal occiput, creating suction. Traction is applied in a downward and outward direction. B, Traction continues in a downward direction as the fetal head begins to emerge from the vagina. C, Traction is maintained to lift the fetal head out of the vagina.

Figure 27– 6 (continued) Vacuum extractor traction. A, The cup is placed on the fetal occiput, creating suction. Traction is applied in a downward and outward direction. B, Traction continues in a downward direction as the fetal head begins to emerge from the vagina. C, Traction is maintained to lift the fetal head out of the vagina.

Figure 27– 6 (continued) Vacuum extractor traction. A, The cup is placed on the fetal occiput, creating suction. Traction is applied in a downward and outward direction. B, Traction continues in a downward direction as the fetal head begins to emerge from the vagina. C, Traction is maintained to lift the fetal head out of the vagina.

Figure 27– 6 (continued) Vacuum extractor traction. A, The cup is placed on the fetal occiput, creating suction. Traction is applied in a downward and outward direction. B, Traction continues in a downward direction as the fetal head begins to emerge from the vagina. C, Traction is maintained to lift the fetal head out of the vagina.

Nursing Management • • Inform woman about procedure Pumps the vacuum Supports the woman Assesses the mother and neonate for complications

Nursing Management • • Inform woman about procedure Pumps the vacuum Supports the woman Assesses the mother and neonate for complications

Neonatal Risks with Vacuum Extraction • • • Scalp lacerations and bruising Shoulder dystocia Subgaleal hematomas Cephalhematomas Intracranial hemorrhages Subconjunctival hemorrhages

Neonatal Risks with Vacuum Extraction • • • Scalp lacerations and bruising Shoulder dystocia Subgaleal hematomas Cephalhematomas Intracranial hemorrhages Subconjunctival hemorrhages

Neonatal Risks with Vacuum Extraction (continued) Neonatal jaundice Fractured clavicle Erb’s palsy Damage to the sixth and seventh cranial nerves • Retinal hemorrhage • Fetal death • •

Neonatal Risks with Vacuum Extraction (continued) Neonatal jaundice Fractured clavicle Erb’s palsy Damage to the sixth and seventh cranial nerves • Retinal hemorrhage • Fetal death • •

Maternal Risks with Vacuum Extraction • • • Perineal trauma Edema Third- and fourth-degree lacerations Postpartum pain Infection More sexual difficulties in the postpartum period

Maternal Risks with Vacuum Extraction • • • Perineal trauma Edema Third- and fourth-degree lacerations Postpartum pain Infection More sexual difficulties in the postpartum period

Indications for Cesarean Birth • • • Complete placenta previa CPD Placental abruption Active genital herpes Umbilical cord prolapse Failure to progress in labor

Indications for Cesarean Birth • • • Complete placenta previa CPD Placental abruption Active genital herpes Umbilical cord prolapse Failure to progress in labor

Indications for Cesarean Birth (continued) • Proven nonreassuring fetal status • Benign and malignant tumors that obstruct the birth canal • Breech presentation • Previous cesarean birth • Major congenital anomalies • Cervical cerclage

Indications for Cesarean Birth (continued) • Proven nonreassuring fetal status • Benign and malignant tumors that obstruct the birth canal • Breech presentation • Previous cesarean birth • Major congenital anomalies • Cervical cerclage

Indications for Cesarean Birth (continued) • Severe Rh isoimmunization • Maternal preference for cesarean birth

Indications for Cesarean Birth (continued) • Severe Rh isoimmunization • Maternal preference for cesarean birth

Impact on the Family • • Stress and anxiety Sense of loss of vaginal birth experience Fear Relief

Impact on the Family • • Stress and anxiety Sense of loss of vaginal birth experience Fear Relief

Preparation for Cesarean Birth • Preoperative teaching – Coughing and deep breathing – Splinting – What to expect

Preparation for Cesarean Birth • Preoperative teaching – Coughing and deep breathing – Splinting – What to expect

Nursing Management Before Cesarean Birth • Assisting with the epidural • Monitoring maternal vital signs and fetal heart rate • Inserting an indwelling urinary catheter • Preparing the abdomen and perineum • Making sure that all necessary personnel and equipment are present • Positioning the woman on the operating table

Nursing Management Before Cesarean Birth • Assisting with the epidural • Monitoring maternal vital signs and fetal heart rate • Inserting an indwelling urinary catheter • Preparing the abdomen and perineum • Making sure that all necessary personnel and equipment are present • Positioning the woman on the operating table

Nursing Management Before Cesarean Birth (continued) • Supporting the couple • Instrument count

Nursing Management Before Cesarean Birth (continued) • Supporting the couple • Instrument count

Nursing Management After Cesarean Birth • • • Normal newborn post-delivery care Monitoring vital signs Checking the surgical dressing Palpating the fundus and checking lochia Monitoring intake and output Administration of oxytocin and pain management

Nursing Management After Cesarean Birth • • • Normal newborn post-delivery care Monitoring vital signs Checking the surgical dressing Palpating the fundus and checking lochia Monitoring intake and output Administration of oxytocin and pain management

Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC): Criteria • One previous cesarean birth and a low transverse uterine incision • An adequate pelvis • No other uterine scars or previous uterine rupture • An available physician who is able to do a cesarean • In-house anesthesia personnel

Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC): Criteria • One previous cesarean birth and a low transverse uterine incision • An adequate pelvis • No other uterine scars or previous uterine rupture • An available physician who is able to do a cesarean • In-house anesthesia personnel

Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC): Risks • Uterine rupture • Stillbirths • Hypoxia

Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC): Risks • Uterine rupture • Stillbirths • Hypoxia

Dysfunctional Labor Patterns: Hypertonic Labor • Characterized by uterine irritability, poor resting tone, frequent contractions • Risks – Maternal exhaustion, pain – Infection – Maternal/fetal injury • Management – Rest, hydration, sedation – Labor augmentation (oxytocin, AROM) • Contributing factors

Dysfunctional Labor Patterns: Hypertonic Labor • Characterized by uterine irritability, poor resting tone, frequent contractions • Risks – Maternal exhaustion, pain – Infection – Maternal/fetal injury • Management – Rest, hydration, sedation – Labor augmentation (oxytocin, AROM) • Contributing factors

Nursing Process • Assessment – Uterine activity, cx change, membranes, fetus, and mom – Fetal tolerance of labor • EFM pg 579 – – FHR Variability Periodic changes See additional handout for EFM

Nursing Process • Assessment – Uterine activity, cx change, membranes, fetus, and mom – Fetal tolerance of labor • EFM pg 579 – – FHR Variability Periodic changes See additional handout for EFM

Nursing Dx- hypertonic • Risk for infection • Acute pain • Deficient knowledge • Fatigue • Anxiety

Nursing Dx- hypertonic • Risk for infection • Acute pain • Deficient knowledge • Fatigue • Anxiety

Outcome evaluation • Hypertonic can evolve into normal pattern • If ineffective continues: c/delivery • RN responsible for reporting and documenting data in time current

Outcome evaluation • Hypertonic can evolve into normal pattern • If ineffective continues: c/delivery • RN responsible for reporting and documenting data in time current

Dysfunctional Labor Patterns: Hypotonic Labor • Characterized by contractions that are inadequate in frequency, duration, intensity • Risks – Maternal exhaustion from long labor – Infection – Maternal/fetal injury • Management – Rest, hydration, sedation – Labor augmentation (oxytocin, AROM) • Contributing factors

Dysfunctional Labor Patterns: Hypotonic Labor • Characterized by contractions that are inadequate in frequency, duration, intensity • Risks – Maternal exhaustion from long labor – Infection – Maternal/fetal injury • Management – Rest, hydration, sedation – Labor augmentation (oxytocin, AROM) • Contributing factors

Nursing Process • The same in all aspects of process to hypertonic

Nursing Process • The same in all aspects of process to hypertonic

Precipitate delivery • Labor that progresses rapidly (< 3 hrs after onset of uterine activity) • Contributing factors – Grand multip, small fetus, relaxed pelvic muscles, hx of same • Risks – Uncontrolled delivery – ACOG allows for induction with contributing factors

Precipitate delivery • Labor that progresses rapidly (< 3 hrs after onset of uterine activity) • Contributing factors – Grand multip, small fetus, relaxed pelvic muscles, hx of same • Risks – Uncontrolled delivery – ACOG allows for induction with contributing factors

Nursing process- precip del • Assessment – Thorough hx, EFM, fetal position changes, (U/S), client responses, fetal tolerance – Be alert for amniotic fluid emboli, uterine atony • Nursing dx – Risk for soft tissue injury – Risk for infection – Anxiety

Nursing process- precip del • Assessment – Thorough hx, EFM, fetal position changes, (U/S), client responses, fetal tolerance – Be alert for amniotic fluid emboli, uterine atony • Nursing dx – Risk for soft tissue injury – Risk for infection – Anxiety

Factors Resulting in High-Risk Deliveries • Malpositions • Cephalopelvic disproportion • Macrosomia • Multiple gestation • Fetal distress • Uterine rupture • • Placenta previa Abruptio placentae Umbilical cord prolapse Polyhydramnios/ oligohydramnios

Factors Resulting in High-Risk Deliveries • Malpositions • Cephalopelvic disproportion • Macrosomia • Multiple gestation • Fetal distress • Uterine rupture • • Placenta previa Abruptio placentae Umbilical cord prolapse Polyhydramnios/ oligohydramnios

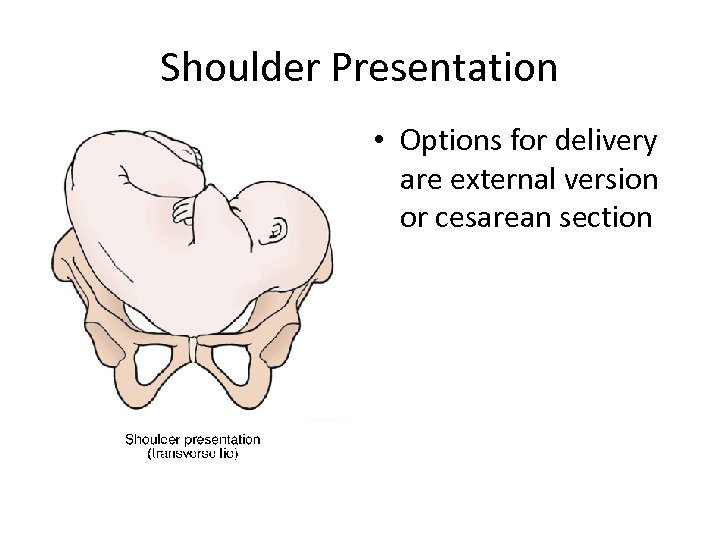

Shoulder Presentation • Options for delivery are external version or cesarean section

Shoulder Presentation • Options for delivery are external version or cesarean section

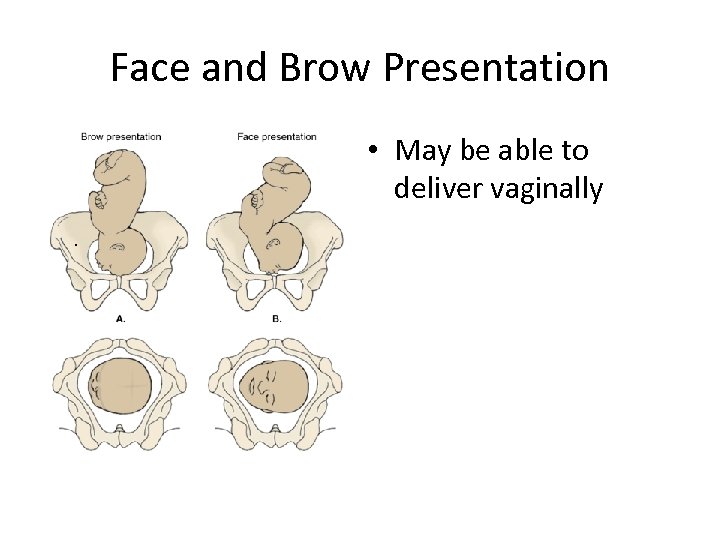

Face and Brow Presentation • May be able to deliver vaginally.

Face and Brow Presentation • May be able to deliver vaginally.

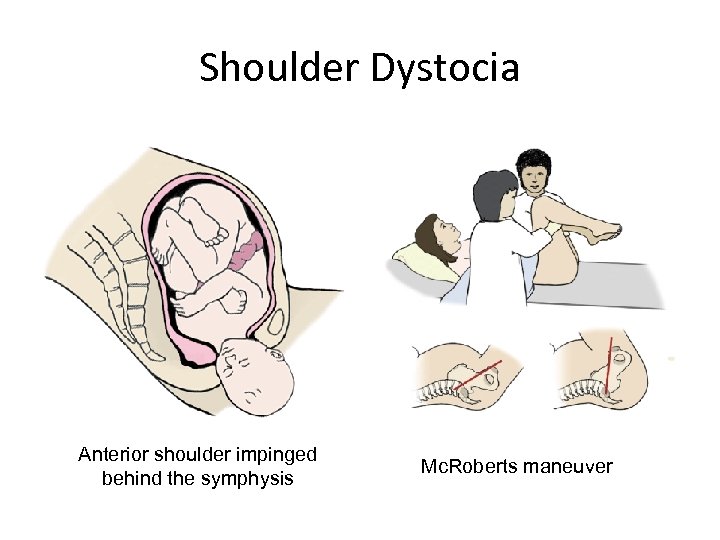

Shoulder Dystocia Anterior shoulder impinged behind the symphysis Mc. Roberts maneuver

Shoulder Dystocia Anterior shoulder impinged behind the symphysis Mc. Roberts maneuver

• CPD – Contributing factors • Irregular shaped pelvis • Fetal macrosomia • Hx of crushed or fx pelvix • Macrosomia – Passenger too big – Can lead to shoulder dystocia – Maternal diabetes – Excessive mat wt gain – Adv. Mat age – Erb’s palsy

• CPD – Contributing factors • Irregular shaped pelvis • Fetal macrosomia • Hx of crushed or fx pelvix • Macrosomia – Passenger too big – Can lead to shoulder dystocia – Maternal diabetes – Excessive mat wt gain – Adv. Mat age – Erb’s palsy

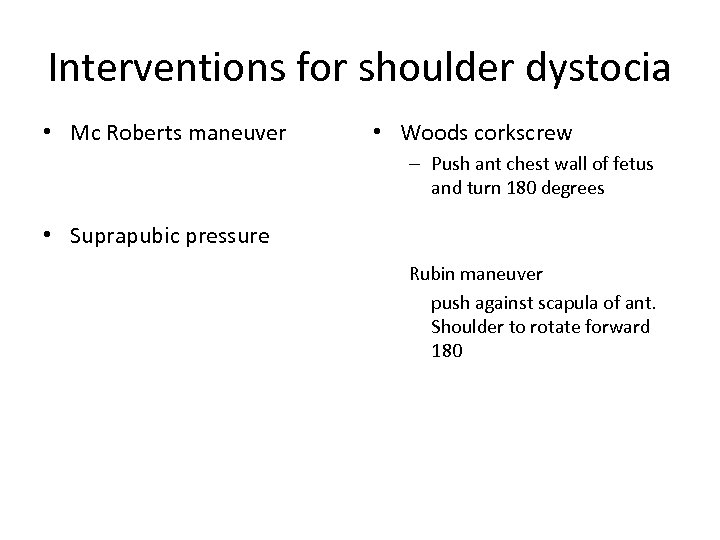

Interventions for shoulder dystocia • Mc Roberts maneuver • Woods corkscrew – Push ant chest wall of fetus and turn 180 degrees • Suprapubic pressure Rubin maneuver push against scapula of ant. Shoulder to rotate forward 180

Interventions for shoulder dystocia • Mc Roberts maneuver • Woods corkscrew – Push ant chest wall of fetus and turn 180 degrees • Suprapubic pressure Rubin maneuver push against scapula of ant. Shoulder to rotate forward 180

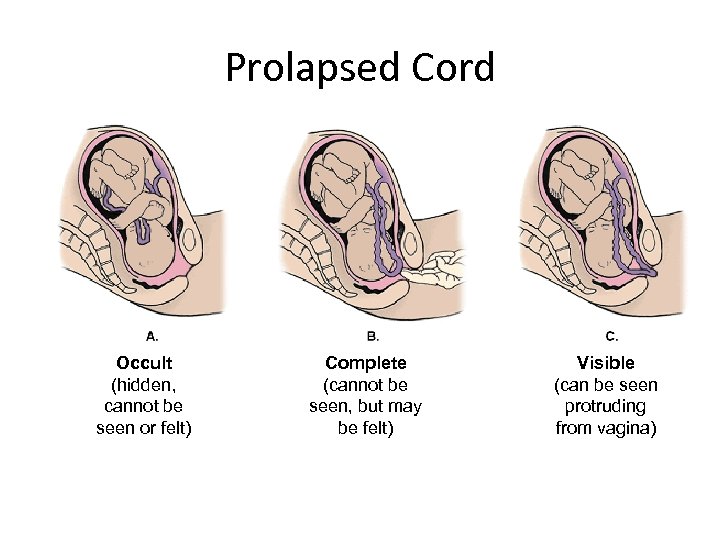

Prolapsed Cord Occult (hidden, cannot be seen or felt) Complete (cannot be seen, but may be felt) Visible (can be seen protruding from vagina)

Prolapsed Cord Occult (hidden, cannot be seen or felt) Complete (cannot be seen, but may be felt) Visible (can be seen protruding from vagina)

Cord abnormalities • Velamentous insertion – Developmental abnormality which may cause decreased fetal perfusion • Vasa previa – Cord vessels over os • Cord compression – During descent – Cord wrapping • Cord prolapse – Cord precedes fetus – Check EFM

Cord abnormalities • Velamentous insertion – Developmental abnormality which may cause decreased fetal perfusion • Vasa previa – Cord vessels over os • Cord compression – During descent – Cord wrapping • Cord prolapse – Cord precedes fetus – Check EFM

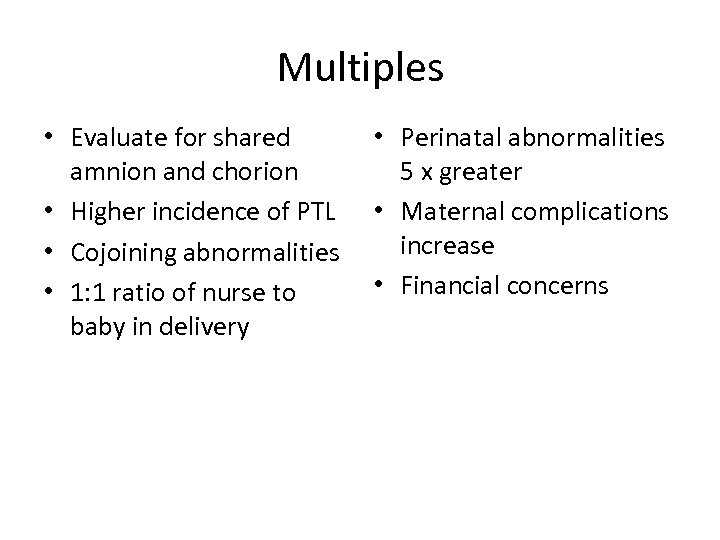

Multiples • Evaluate for shared amnion and chorion • Higher incidence of PTL • Cojoining abnormalities • 1: 1 ratio of nurse to baby in delivery • Perinatal abnormalities 5 x greater • Maternal complications increase • Financial concerns

Multiples • Evaluate for shared amnion and chorion • Higher incidence of PTL • Cojoining abnormalities • 1: 1 ratio of nurse to baby in delivery • Perinatal abnormalities 5 x greater • Maternal complications increase • Financial concerns

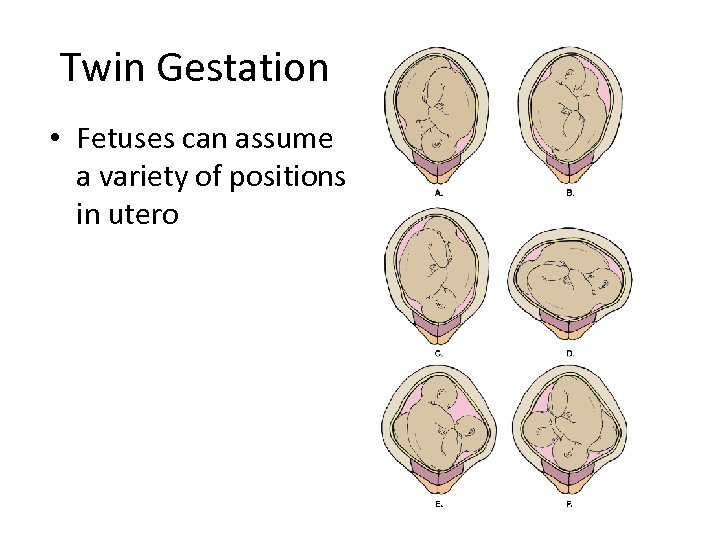

Twin Gestation • Fetuses can assume a variety of positions in utero

Twin Gestation • Fetuses can assume a variety of positions in utero