2685f06018f35f4c03409b108b253d2e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 101

Nuclear Unit Nuclear Chemistry Unit for Honors Chemistry By E. Garman

Nuclear Unit Nuclear Chemistry Unit for Honors Chemistry By E. Garman

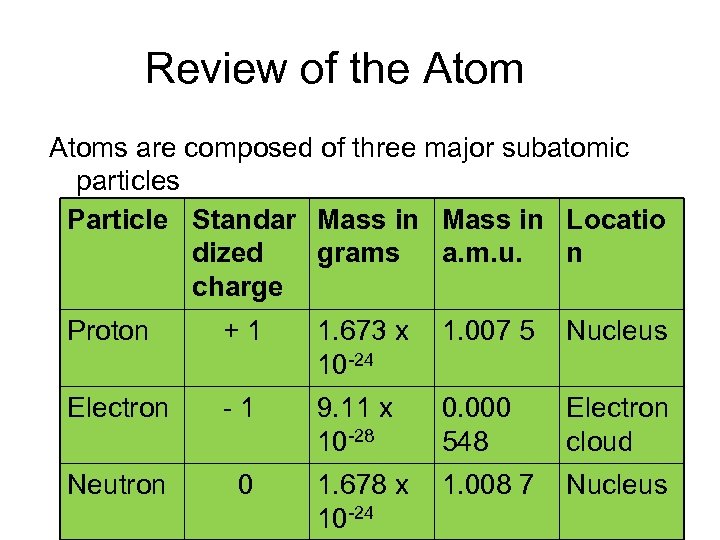

Review of the Atoms are composed of three major subatomic particles Particle Standar Mass in Locatio dized grams a. m. u. n charge Proton + 1 1. 673 x 1. 007 5 10 -24 Nucleus Electron - 1 9. 11 x 10 -28 Electron cloud Neutron 0 1. 678 x 1. 008 7 10 -24 0. 000 548 Nucleus

Review of the Atoms are composed of three major subatomic particles Particle Standar Mass in Locatio dized grams a. m. u. n charge Proton + 1 1. 673 x 1. 007 5 10 -24 Nucleus Electron - 1 9. 11 x 10 -28 Electron cloud Neutron 0 1. 678 x 1. 008 7 10 -24 0. 000 548 Nucleus

Review of the Atomic number; Z – represents the number of protons in an atom’s (element’s) nucleus - identifies the element Mass number; A – represents the sum of protons and neutrons in the nucleus - indicates the number of major nucleons Nucleons -

Review of the Atomic number; Z – represents the number of protons in an atom’s (element’s) nucleus - identifies the element Mass number; A – represents the sum of protons and neutrons in the nucleus - indicates the number of major nucleons Nucleons -

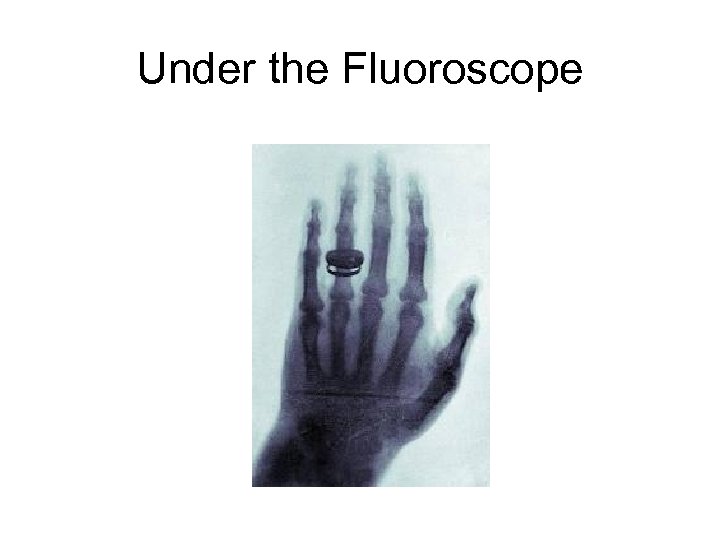

Discovery of x-rays Wilhelm Roentgen discovered x-rays in 1895 - observed the bone structure and wedding ring of his wife’s hand when working with rays emanating from vacuum tubes

Discovery of x-rays Wilhelm Roentgen discovered x-rays in 1895 - observed the bone structure and wedding ring of his wife’s hand when working with rays emanating from vacuum tubes

Under the Fluoroscope

Under the Fluoroscope

Radioactivity Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity in 1896 - an accidental discovery while working with fluorescence and phosphorescence of potassium uranyl sulfate Fluorescence – Phosphorescence - radioactivity – the spontaneous emission of particles and energy from unstable atomic nuclei

Radioactivity Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity in 1896 - an accidental discovery while working with fluorescence and phosphorescence of potassium uranyl sulfate Fluorescence – Phosphorescence - radioactivity – the spontaneous emission of particles and energy from unstable atomic nuclei

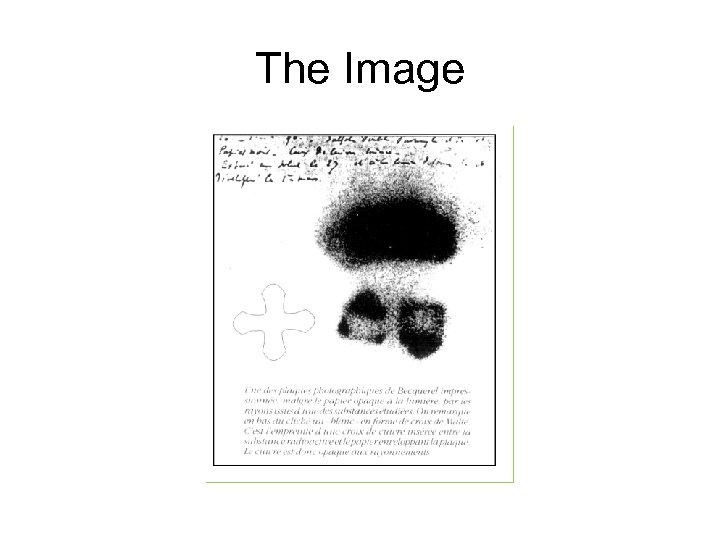

The Image

The Image

Radioactive elements Marie and Pierre Curie discover the elements polonium and radium as being radioactive - these elements were extracted from uranium ore Thus begins the study of nuclear chemistry or nuclear physics

Radioactive elements Marie and Pierre Curie discover the elements polonium and radium as being radioactive - these elements were extracted from uranium ore Thus begins the study of nuclear chemistry or nuclear physics

Nuclear vs. Chemical Nuclear chemistry pertains to the properties, energies, and behaviors of the nucleus Chemistry pertains to the study of matter, its properties and behaviors - these are established by the electron; its energies, locations, and behaviors within the electron cloud

Nuclear vs. Chemical Nuclear chemistry pertains to the properties, energies, and behaviors of the nucleus Chemistry pertains to the study of matter, its properties and behaviors - these are established by the electron; its energies, locations, and behaviors within the electron cloud

Isotopes are atoms of the same element that differ in mass - these mass differences are due to differing numbers of neutrons - radioactive isotopes are referred to as radioisotopes

Isotopes are atoms of the same element that differ in mass - these mass differences are due to differing numbers of neutrons - radioactive isotopes are referred to as radioisotopes

Radiations Radiation may be particulate (composed of particles) or all energy (electromagnetic radiation) Particulate radiations: Alpha - α – helium nuclei (helium atom w/o electrons) - has + 2 charge – 42 He (equation symbol) - poor penetrating radiation - strong ionizing radiation

Radiations Radiation may be particulate (composed of particles) or all energy (electromagnetic radiation) Particulate radiations: Alpha - α – helium nuclei (helium atom w/o electrons) - has + 2 charge – 42 He (equation symbol) - poor penetrating radiation - strong ionizing radiation

Radiations Beta - β- - high speed electron - charge of negative 0 ne (- 1) - 0 -1 e (equation symbol) - fair penetrating radiation - fair ionizing radiation

Radiations Beta - β- - high speed electron - charge of negative 0 ne (- 1) - 0 -1 e (equation symbol) - fair penetrating radiation - fair ionizing radiation

Radiations Non-particulate radiations X-ray – χ–ray - all energy radiation - part of electromagnetic spectrum - good penetrating radiation - fair ionizing radiation Gamma rays - γ – all energy radiation - similar to x-rays but carrying greater energy - strong penetrating radiation - variable ionizing ability (pending upon energy)

Radiations Non-particulate radiations X-ray – χ–ray - all energy radiation - part of electromagnetic spectrum - good penetrating radiation - fair ionizing radiation Gamma rays - γ – all energy radiation - similar to x-rays but carrying greater energy - strong penetrating radiation - variable ionizing ability (pending upon energy)

Radiation Energies e. V – electron volt – unit of energy - defined as energy required by an electron to move through a potential difference of one volt in a vacuum Volt – unit of potential difference in the “mks” system equal to the potential difference between two points for which one coulomb of electricity will do one joule of work - or, electromotive force (emf) or “push” needed to force one coulomb of charge to do one joule of work

Radiation Energies e. V – electron volt – unit of energy - defined as energy required by an electron to move through a potential difference of one volt in a vacuum Volt – unit of potential difference in the “mks” system equal to the potential difference between two points for which one coulomb of electricity will do one joule of work - or, electromotive force (emf) or “push” needed to force one coulomb of charge to do one joule of work

Coulomb – unit of electrical charge equivalent to 6. 241 5 x 1018 charges (p+’s or e-’s which are “elementary” charges) - equivalent to an ampere-second (A-s) 1 e. V = 1. 602 192 x 10 -19 J

Coulomb – unit of electrical charge equivalent to 6. 241 5 x 1018 charges (p+’s or e-’s which are “elementary” charges) - equivalent to an ampere-second (A-s) 1 e. V = 1. 602 192 x 10 -19 J

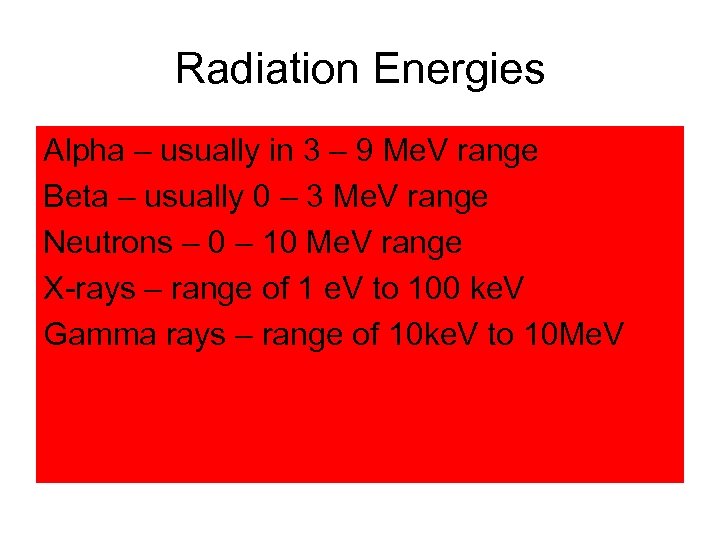

Radiation Energies Alpha – usually in 3 – 9 Me. V range Beta – usually 0 – 3 Me. V range Neutrons – 0 – 10 Me. V range X-rays – range of 1 e. V to 100 ke. V Gamma rays – range of 10 ke. V to 10 Me. V

Radiation Energies Alpha – usually in 3 – 9 Me. V range Beta – usually 0 – 3 Me. V range Neutrons – 0 – 10 Me. V range X-rays – range of 1 e. V to 100 ke. V Gamma rays – range of 10 ke. V to 10 Me. V

Additional Particles Neutron – 10 n - possess no charge - result from fission reactions - strong penetrating radiation - poor ionizing radiation

Additional Particles Neutron – 10 n - possess no charge - result from fission reactions - strong penetrating radiation - poor ionizing radiation

Additional Particles Positron – β+ - positive electron - antiparticle of the electron (same properties; opposite charge) - short-lived – combines with electron to form positronium which decomposes forming two gamma rays - called annhiliation - 0+1 e (equation symbol)

Additional Particles Positron – β+ - positive electron - antiparticle of the electron (same properties; opposite charge) - short-lived – combines with electron to form positronium which decomposes forming two gamma rays - called annhiliation - 0+1 e (equation symbol)

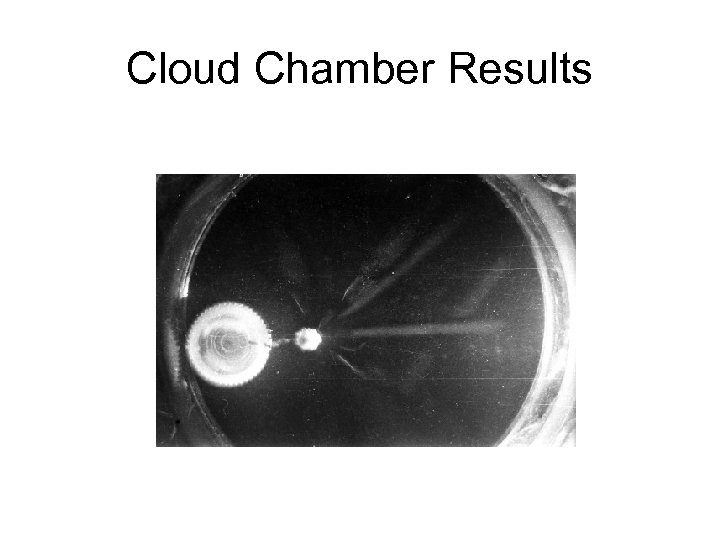

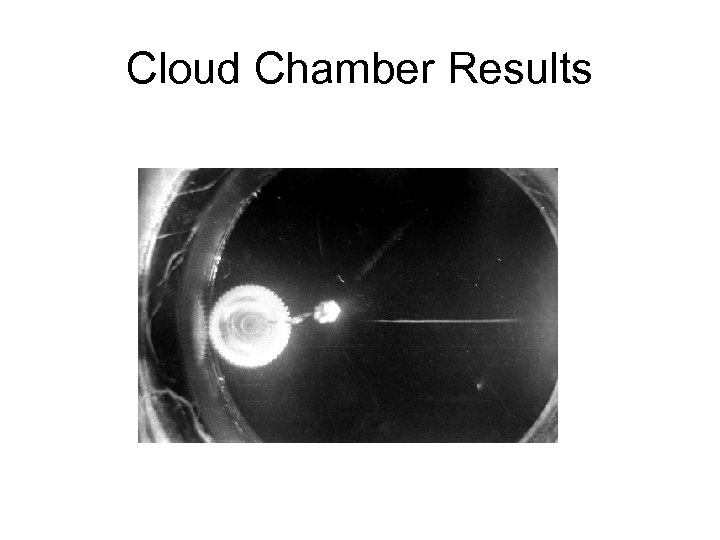

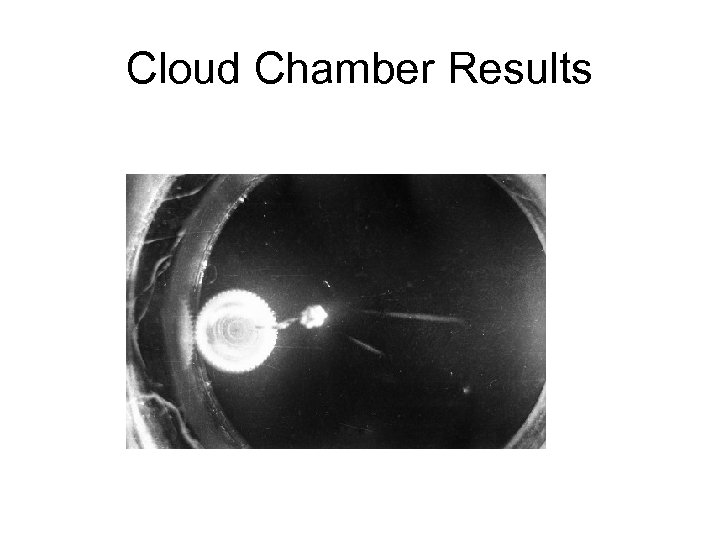

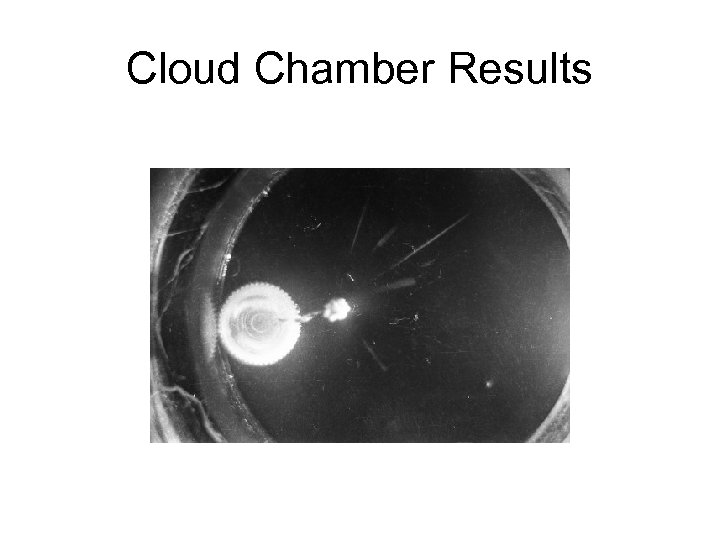

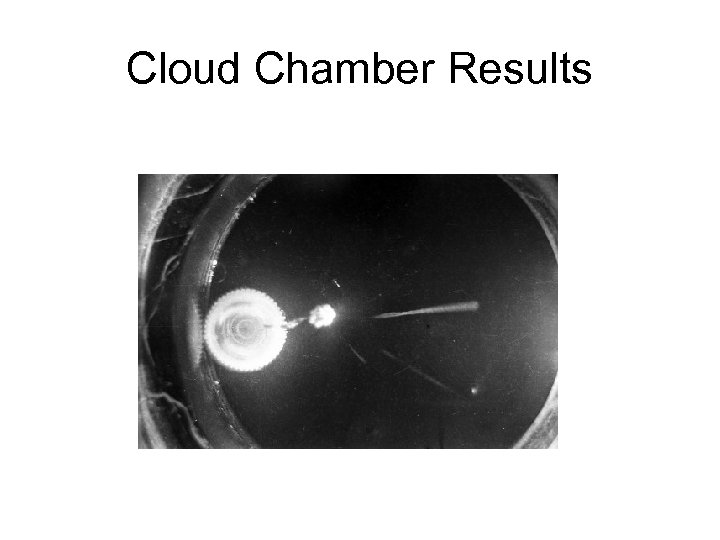

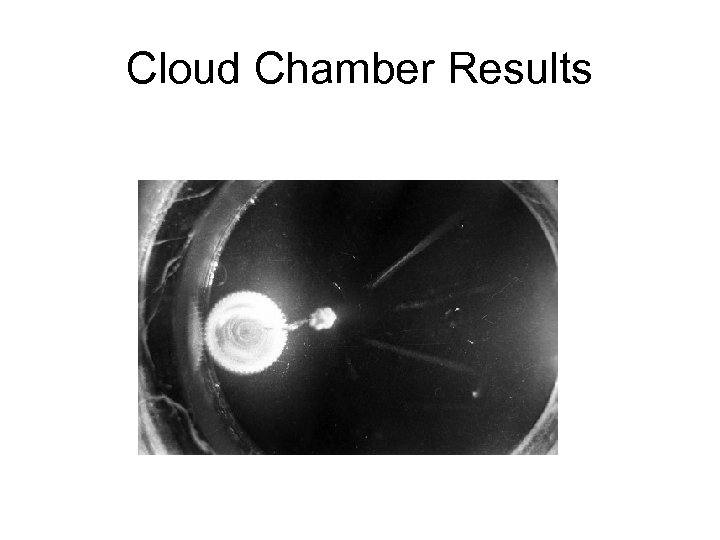

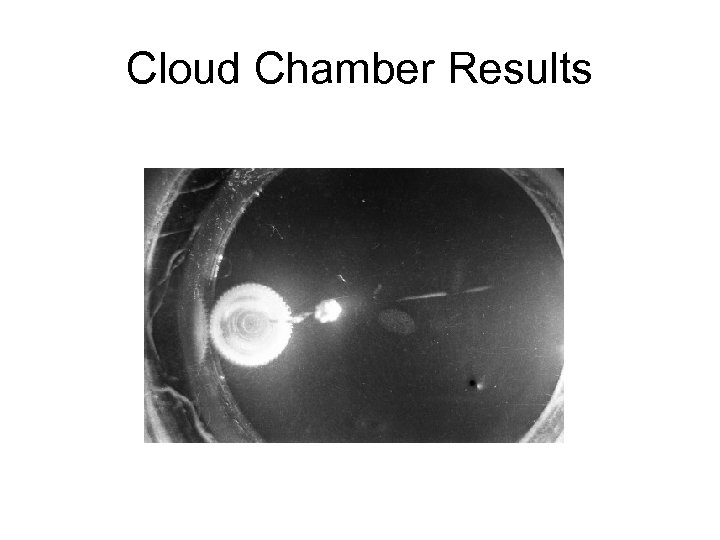

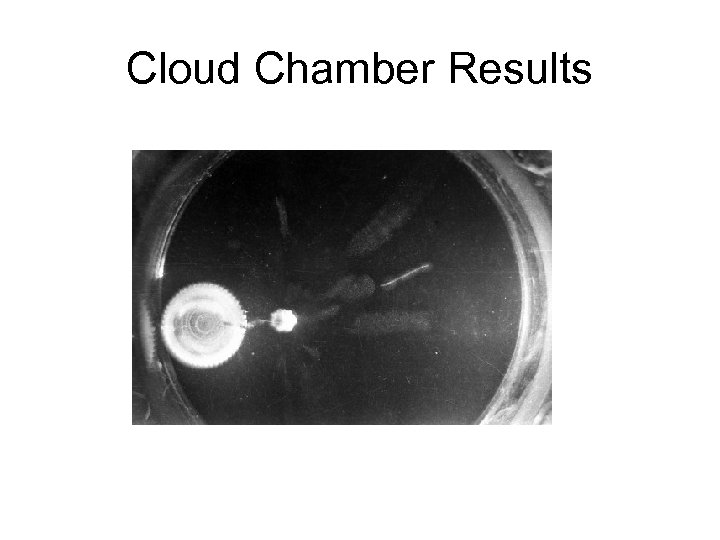

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Cloud Chamber Results

Nuclear Stability Elements are composed of isotopes Some isotopes are naturally occurring and some are man-made Atoms of specific isotopes are referred to as nuclides These nuclides have a specific mass number

Nuclear Stability Elements are composed of isotopes Some isotopes are naturally occurring and some are man-made Atoms of specific isotopes are referred to as nuclides These nuclides have a specific mass number

Nuclear Stability may be defined as the tendency of an object or system to return to its equilibrium position after it has been moved/shifted by an external force It is related to enthalpy and entropy Enthalpy basically refers to the energy content of a system Entropy refers to the state of disorder within a system

Nuclear Stability may be defined as the tendency of an object or system to return to its equilibrium position after it has been moved/shifted by an external force It is related to enthalpy and entropy Enthalpy basically refers to the energy content of a system Entropy refers to the state of disorder within a system

Nuclear Stability is inversely related to energy and directly related to disorder Meaning, both low energy and higher disorder favor stability The converse is true

Nuclear Stability is inversely related to energy and directly related to disorder Meaning, both low energy and higher disorder favor stability The converse is true

Nuclear Stability Systems and objects in the universe are driven to attain the maximum stability possible for them Unstable isotopes will be radioactive, thus they change in an attempt to become more stable

Nuclear Stability Systems and objects in the universe are driven to attain the maximum stability possible for them Unstable isotopes will be radioactive, thus they change in an attempt to become more stable

Predicting stability of radioisotopes All nuclei with 84 protons are unstable The quantity of positive charge in the nucleus is too great causing tremendous repulsive forces which result in high energies

Predicting stability of radioisotopes All nuclei with 84 protons are unstable The quantity of positive charge in the nucleus is too great causing tremendous repulsive forces which result in high energies

Predicting stability of radioisotopes Isotopes having a certain number of protons or of neutrons tend to be more stable These numbers are sometimes referred to as the “magic numbers” The magic numbers are – proton: 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, 114 – neutron: 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, 126, 184 We find a similar situation in regarding to chemical activity and number of electrons

Predicting stability of radioisotopes Isotopes having a certain number of protons or of neutrons tend to be more stable These numbers are sometimes referred to as the “magic numbers” The magic numbers are – proton: 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, 114 – neutron: 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, 126, 184 We find a similar situation in regarding to chemical activity and number of electrons

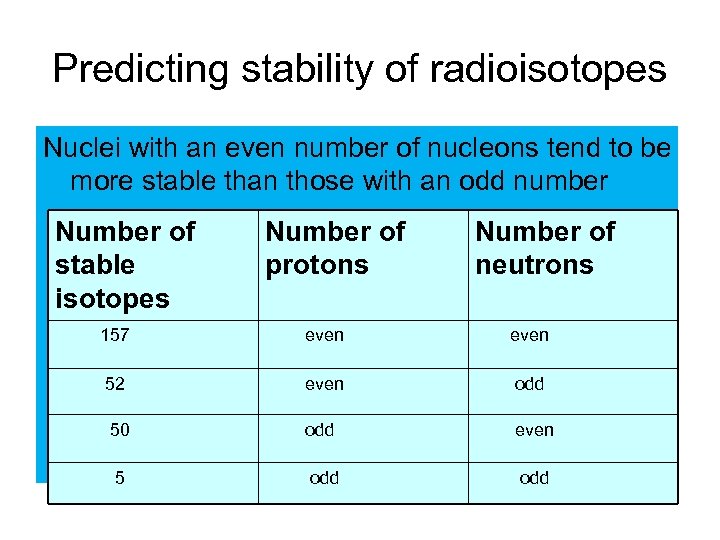

Predicting stability of radioisotopes Nuclei with an even number of nucleons tend to be more stable than those with an odd number Number of stable isotopes Number of protons Number of neutrons 157 even 52 even odd 50 odd even 5 odd

Predicting stability of radioisotopes Nuclei with an even number of nucleons tend to be more stable than those with an odd number Number of stable isotopes Number of protons Number of neutrons 157 even 52 even odd 50 odd even 5 odd

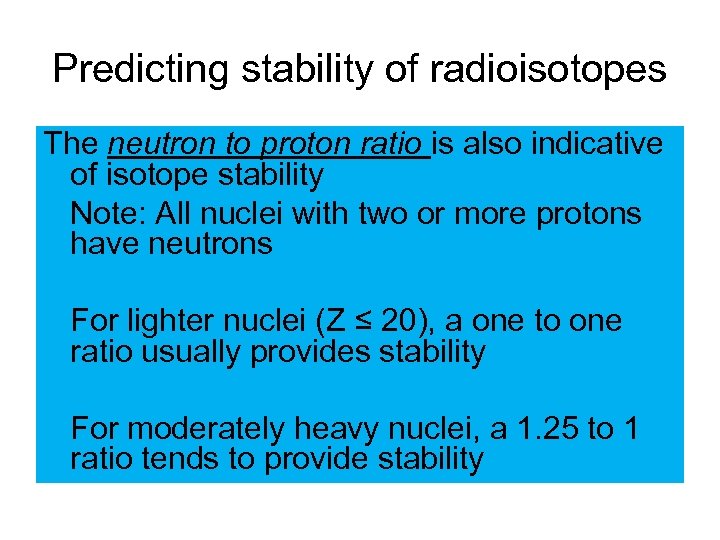

Predicting stability of radioisotopes The neutron to proton ratio is also indicative of isotope stability Note: All nuclei with two or more protons have neutrons For lighter nuclei (Z ≤ 20), a one to one ratio usually provides stability For moderately heavy nuclei, a 1. 25 to 1 ratio tends to provide stability

Predicting stability of radioisotopes The neutron to proton ratio is also indicative of isotope stability Note: All nuclei with two or more protons have neutrons For lighter nuclei (Z ≤ 20), a one to one ratio usually provides stability For moderately heavy nuclei, a 1. 25 to 1 ratio tends to provide stability

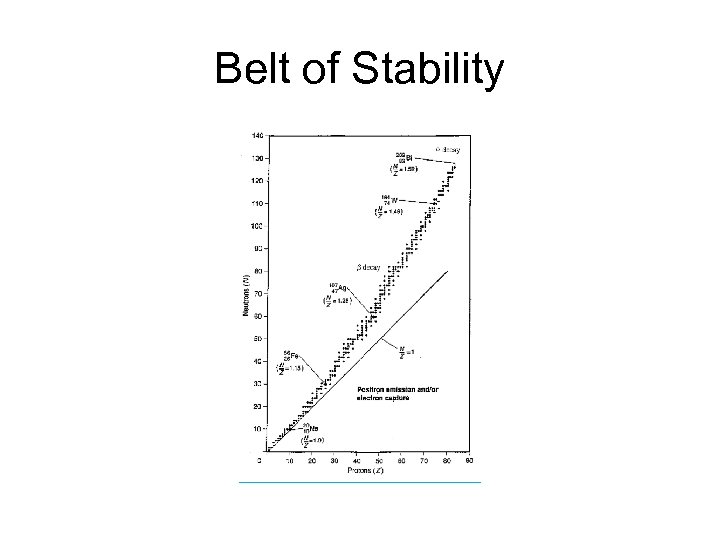

Predicting stability of radioisotopes For heavy nuclei, a ratio of 1. 5 to 1 tends to provide the needed stability These stable isotopes may be found in what is called the “belt of stability”

Predicting stability of radioisotopes For heavy nuclei, a ratio of 1. 5 to 1 tends to provide the needed stability These stable isotopes may be found in what is called the “belt of stability”

Belt of Stability

Belt of Stability

Nuclear Change Isotopes outside the belt of stability will change in an attempt to move towards the belt These changes often result in alteration of the element’s identity Referred to as nuclear transmutation Occurs because the number of protons in the nucleus is changed

Nuclear Change Isotopes outside the belt of stability will change in an attempt to move towards the belt These changes often result in alteration of the element’s identity Referred to as nuclear transmutation Occurs because the number of protons in the nucleus is changed

Neutron Rich Nuclides These nuclides, being above the belt, have too many neutrons and will often undergo beta emission This results in a neutron decomposing into a proton and an electron 0 n -----> p+ + e-

Neutron Rich Nuclides These nuclides, being above the belt, have too many neutrons and will often undergo beta emission This results in a neutron decomposing into a proton and an electron 0 n -----> p+ + e-

Proton rich (neutron deficient) nuclides These nuclides, being below the belt, have too few neutrons and will often undergo positron emission or K – electron capture Lighter nuclei prefer positron emission while heavier nuclei prefer K-electron capture p+ -----> 0 n + e+ p+ + e- -----> 0 n

Proton rich (neutron deficient) nuclides These nuclides, being below the belt, have too few neutrons and will often undergo positron emission or K – electron capture Lighter nuclei prefer positron emission while heavier nuclei prefer K-electron capture p+ -----> 0 n + e+ p+ + e- -----> 0 n

Nuclides with Z greater than 83 These nuclides will usually attempt to decrease their nuclear size in the most expedient manner These nuclides often emit alpha particle(s) in attempting to stabilize

Nuclides with Z greater than 83 These nuclides will usually attempt to decrease their nuclear size in the most expedient manner These nuclides often emit alpha particle(s) in attempting to stabilize

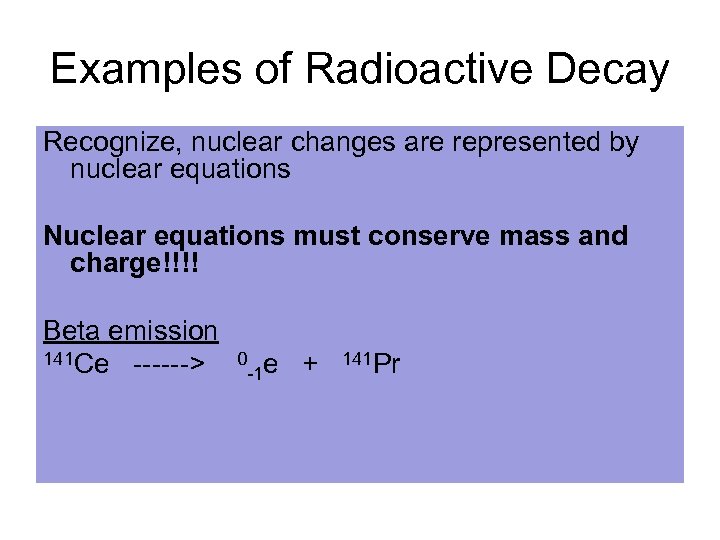

Examples of Radioactive Decay Recognize, nuclear changes are represented by nuclear equations Nuclear equations must conserve mass and charge!!!! Beta emission 141 Ce ------> 0 e + 141 Pr -1

Examples of Radioactive Decay Recognize, nuclear changes are represented by nuclear equations Nuclear equations must conserve mass and charge!!!! Beta emission 141 Ce ------> 0 e + 141 Pr -1

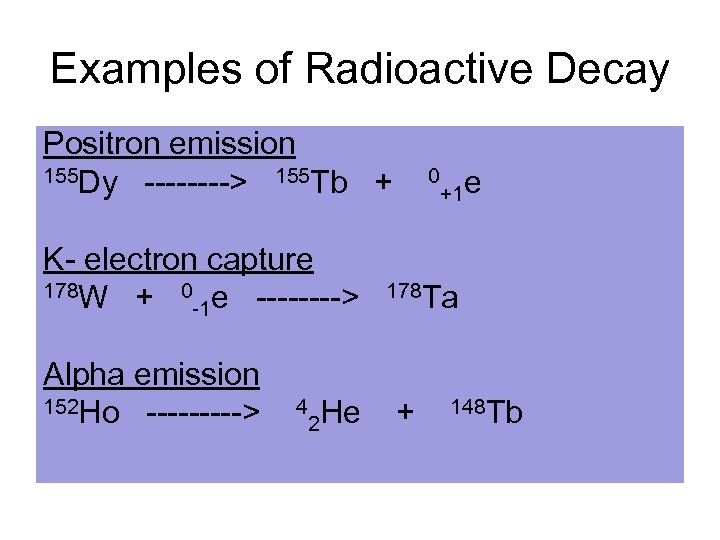

Examples of Radioactive Decay Positron emission 155 Dy ----> 155 Tb + 0 e +1 K- electron capture 178 W + 0 e ----> 178 Ta -1 Alpha emission 152 Ho -----> 4 He + 148 Tb 2

Examples of Radioactive Decay Positron emission 155 Dy ----> 155 Tb + 0 e +1 K- electron capture 178 W + 0 e ----> 178 Ta -1 Alpha emission 152 Ho -----> 4 He + 148 Tb 2

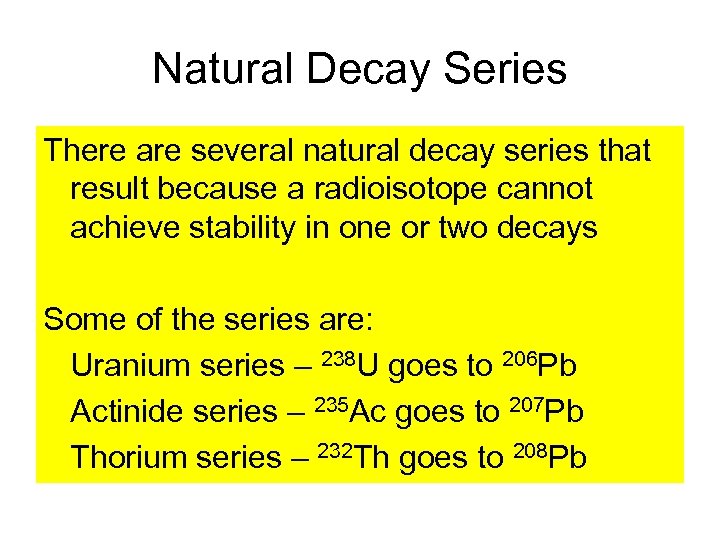

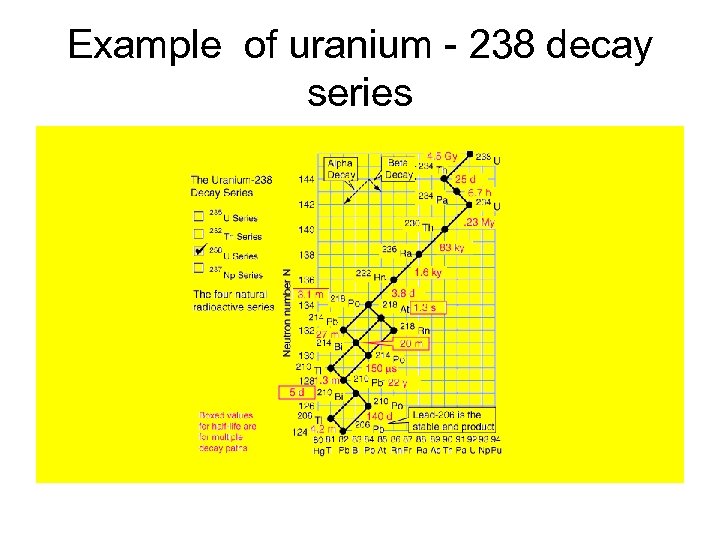

Natural Decay Series There are several natural decay series that result because a radioisotope cannot achieve stability in one or two decays Some of the series are: Uranium series – 238 U goes to 206 Pb Actinide series – 235 Ac goes to 207 Pb Thorium series – 232 Th goes to 208 Pb

Natural Decay Series There are several natural decay series that result because a radioisotope cannot achieve stability in one or two decays Some of the series are: Uranium series – 238 U goes to 206 Pb Actinide series – 235 Ac goes to 207 Pb Thorium series – 232 Th goes to 208 Pb

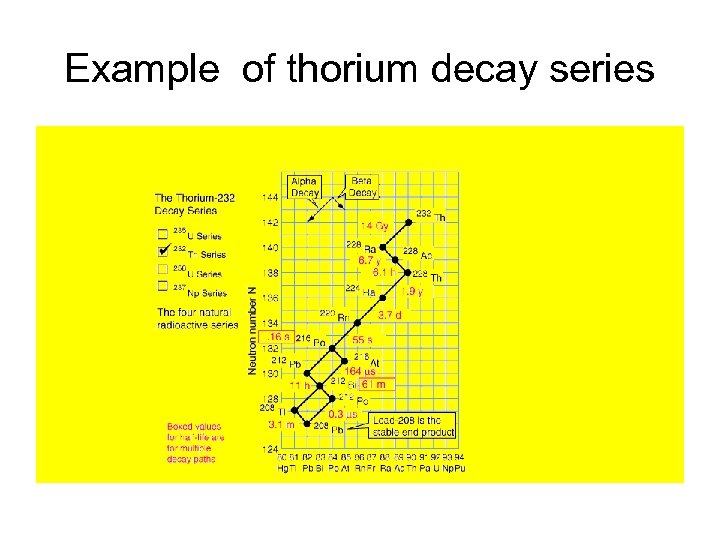

Example of thorium decay series

Example of thorium decay series

Example of uranium - 238 decay series

Example of uranium - 238 decay series

Formation of new Isotopes may be formed by driving “bullet particles into nuclei The nuclei impacted are referred to as “targets” Bullet particles having a charge require more energy in order to overcome Coulombic repulsion (e. g. 11 p (+1), 42 He (+2), etc. ) Energies are determined from bullet particle speed

Formation of new Isotopes may be formed by driving “bullet particles into nuclei The nuclei impacted are referred to as “targets” Bullet particles having a charge require more energy in order to overcome Coulombic repulsion (e. g. 11 p (+1), 42 He (+2), etc. ) Energies are determined from bullet particle speed

Cyclotrons/Synchocyclotrons Cyclotrons are composed of hollow “D” shaped electrodes called “dees” The projectile particle enters the vacuum chamber and is accelerated by alternating the polarity on the dees Magnets above and below the dees keep the particle moving in a spiral path

Cyclotrons/Synchocyclotrons Cyclotrons are composed of hollow “D” shaped electrodes called “dees” The projectile particle enters the vacuum chamber and is accelerated by alternating the polarity on the dees Magnets above and below the dees keep the particle moving in a spiral path

Formation of new Isotopes Accelerators are used in order to increase bullet projectile speeds Many accelerators utilize electrical or magnetic fields Some newer accelerators use lasers

Formation of new Isotopes Accelerators are used in order to increase bullet projectile speeds Many accelerators utilize electrical or magnetic fields Some newer accelerators use lasers

Cyclotrons/Synchocyclotrons Once the projectile obtains sufficient energy it is sent from the accelerator towards the target nucleus

Cyclotrons/Synchocyclotrons Once the projectile obtains sufficient energy it is sent from the accelerator towards the target nucleus

Neutrons, although requiring special means for acceleration (i. e. proton packaging), make good bullet particles Often neutrons are used without any acceleration by merely selecting different sources Alpha, beta, protons, etc. while good for accelerating, are often difficult to use

Neutrons, although requiring special means for acceleration (i. e. proton packaging), make good bullet particles Often neutrons are used without any acceleration by merely selecting different sources Alpha, beta, protons, etc. while good for accelerating, are often difficult to use

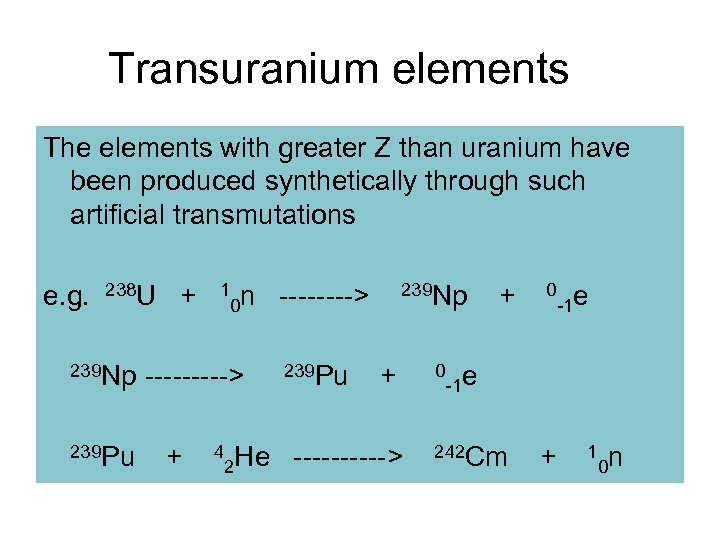

Transuranium elements The elements with greater Z than uranium have been produced synthetically through such artificial transmutations e. g. 238 U + 10 n ----> 239 Np + 0 -1 e 239 Np -----> 239 Pu + 0 239 Pu + 4 -1 e He -----> 242 Cm + 10 n 2

Transuranium elements The elements with greater Z than uranium have been produced synthetically through such artificial transmutations e. g. 238 U + 10 n ----> 239 Np + 0 -1 e 239 Np -----> 239 Pu + 0 239 Pu + 4 -1 e He -----> 242 Cm + 10 n 2

Half-life is used to describe the rate of radioactive decay This is a first order process – meaning the process depends upon only one reactant (in this case the radioisotope) As a result, changes in the concentration of this reactant will produce proportional changes in the rate of the reaction

Half-life is used to describe the rate of radioactive decay This is a first order process – meaning the process depends upon only one reactant (in this case the radioisotope) As a result, changes in the concentration of this reactant will produce proportional changes in the rate of the reaction

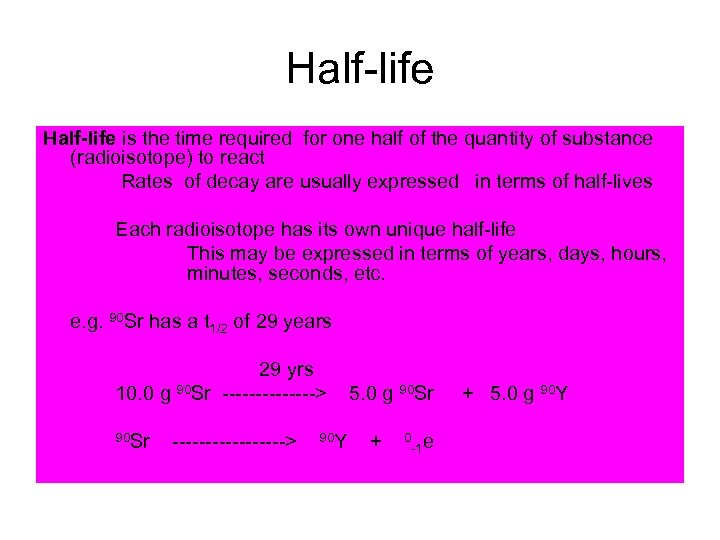

Half-life is the time required for one half of the quantity of substance (radioisotope) to react Rates of decay are usually expressed in terms of half-lives Each radioisotope has its own unique half-life This may be expressed in terms of years, days, hours, minutes, seconds, etc. e. g. 90 Sr has a t 1/2 of 29 years 29 yrs 10. 0 g 90 Sr -------> 5. 0 g 90 Sr + 5. 0 g 90 Y 90 Sr ---------> 90 Y + 0 -1 e

Half-life is the time required for one half of the quantity of substance (radioisotope) to react Rates of decay are usually expressed in terms of half-lives Each radioisotope has its own unique half-life This may be expressed in terms of years, days, hours, minutes, seconds, etc. e. g. 90 Sr has a t 1/2 of 29 years 29 yrs 10. 0 g 90 Sr -------> 5. 0 g 90 Sr + 5. 0 g 90 Y 90 Sr ---------> 90 Y + 0 -1 e

Half-life The challenges of radioactive decay is that it remains unaffected by external conditions e. g. temperature, pressure, presence in a compound, etc.

Half-life The challenges of radioactive decay is that it remains unaffected by external conditions e. g. temperature, pressure, presence in a compound, etc.

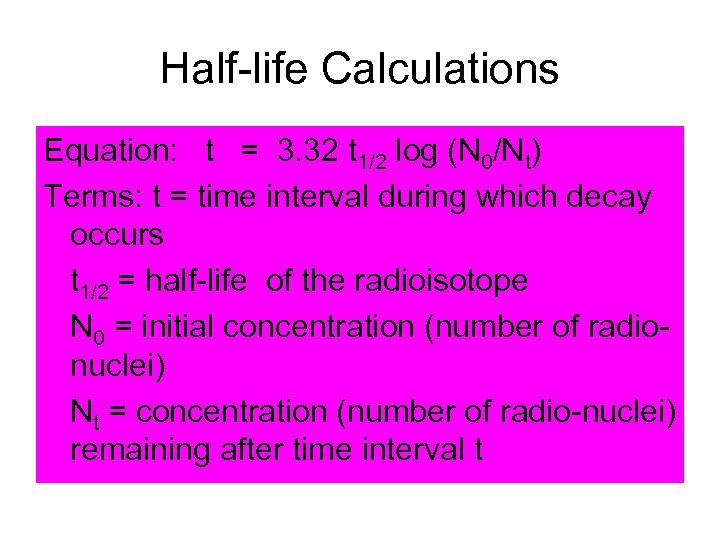

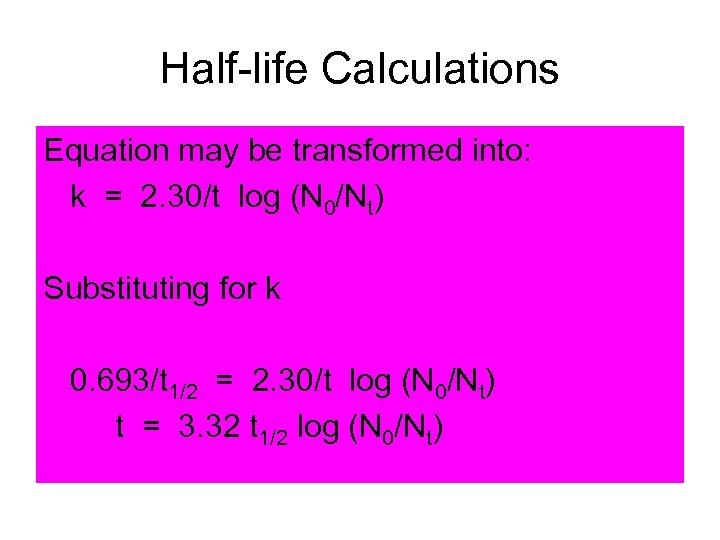

Half-life Calculations Equation: t = 3. 32 t 1/2 log (N 0/Nt) Terms: t = time interval during which decay occurs t 1/2 = half-life of the radioisotope N 0 = initial concentration (number of radionuclei) Nt = concentration (number of radio-nuclei) remaining after time interval t

Half-life Calculations Equation: t = 3. 32 t 1/2 log (N 0/Nt) Terms: t = time interval during which decay occurs t 1/2 = half-life of the radioisotope N 0 = initial concentration (number of radionuclei) Nt = concentration (number of radio-nuclei) remaining after time interval t

Half-life Calculations Rate of decay = k N 0 k is the first order rate constant k = 0. 693/t 1/2 N 0 = number of nuclei of the radioisotope

Half-life Calculations Rate of decay = k N 0 k is the first order rate constant k = 0. 693/t 1/2 N 0 = number of nuclei of the radioisotope

Half-life Calculations Equation may be transformed into: k = 2. 30/t log (N 0/Nt) Substituting for k 0. 693/t 1/2 = 2. 30/t log (N 0/Nt) t = 3. 32 t 1/2 log (N 0/Nt)

Half-life Calculations Equation may be transformed into: k = 2. 30/t log (N 0/Nt) Substituting for k 0. 693/t 1/2 = 2. 30/t log (N 0/Nt) t = 3. 32 t 1/2 log (N 0/Nt)

Dating Radioactive decay is useful in “aging” many pieces of matter It is constant and unaffected by conditions Organic (once living) materials are dated using carbon – 14 (14 C) Uranium bearing rocks use the ratio between 238 U and 206 Pb with uranium – 238 t 1/2 = 4. 5 x 109 yrs

Dating Radioactive decay is useful in “aging” many pieces of matter It is constant and unaffected by conditions Organic (once living) materials are dated using carbon – 14 (14 C) Uranium bearing rocks use the ratio between 238 U and 206 Pb with uranium – 238 t 1/2 = 4. 5 x 109 yrs

Carbon Dating Process In the upper atmosphere carbon – 14 is formed by neutron capture 14 N + 1 n -------> 14 C + 1 H 0 This provides a small constant source of 14 C in the atmosphere 14 C is a radioisotope with t of 5, 700 1/2 years The 14 C unites with oxygen forming 14 CO 2 which eventually is assimilated into green plants via photosynthesis

Carbon Dating Process In the upper atmosphere carbon – 14 is formed by neutron capture 14 N + 1 n -------> 14 C + 1 H 0 This provides a small constant source of 14 C in the atmosphere 14 C is a radioisotope with t of 5, 700 1/2 years The 14 C unites with oxygen forming 14 CO 2 which eventually is assimilated into green plants via photosynthesis

Carbon Dating Process The plants consumed by herbivores and omnivores are incorporated into living animals As long as these living organisms continue to consuming atmospheric carbon in some manner, they eventually build a constant ratio of 14 C to 12 C similar to that of the atmosphere

Carbon Dating Process The plants consumed by herbivores and omnivores are incorporated into living animals As long as these living organisms continue to consuming atmospheric carbon in some manner, they eventually build a constant ratio of 14 C to 12 C similar to that of the atmosphere

Carbon Dating Process Upon the organism’s death, it no longer replenishes its 14 C from the atmosphere The 14 C however is continually decaying whether the organism is dead or alive As a result, the 14 C/12 C ratio starts decreasing upon death 14 C -------> 14 N + 0 e (beta) -1

Carbon Dating Process Upon the organism’s death, it no longer replenishes its 14 C from the atmosphere The 14 C however is continually decaying whether the organism is dead or alive As a result, the 14 C/12 C ratio starts decreasing upon death 14 C -------> 14 N + 0 e (beta) -1

Carbon Dating Process If the ratio decreases to one half its value, then the organism’s remains are 5, 700 years old, etc. 14 C dating is limited to about 50, 000 years as the quantity of radiation emitted becomes too small to be measurable How has 14 C dating been validated? Trees – counting rings vs. the dating process

Carbon Dating Process If the ratio decreases to one half its value, then the organism’s remains are 5, 700 years old, etc. 14 C dating is limited to about 50, 000 years as the quantity of radiation emitted becomes too small to be measurable How has 14 C dating been validated? Trees – counting rings vs. the dating process

Radiation Detection Radiation detection is difficult because it cannot been seen, heard, smelled, etc. As a result, radiation provides man with one of his “fears” There are several methods of detection

Radiation Detection Radiation detection is difficult because it cannot been seen, heard, smelled, etc. As a result, radiation provides man with one of his “fears” There are several methods of detection

Radiation Detection Photographic plates and film have been used for radiation detection for a long time The film or film plate becomes exposed due to the radiation; it is developed and the exposures counted Greater numbers of exposures mean the higher the amount of radiation Film badges have been used by radiation handlers over the years

Radiation Detection Photographic plates and film have been used for radiation detection for a long time The film or film plate becomes exposed due to the radiation; it is developed and the exposures counted Greater numbers of exposures mean the higher the amount of radiation Film badges have been used by radiation handlers over the years

Radiation Detection The Geiger counter or Geiger-Müeller counter is used for radiation detection based upon ionizing ability Ionized matter, composed of cations and anions, permit conduction of electrical current Current is related to extent of ionization and eventually radiation exposure This detection method is used for alpha, beta, and gamma

Radiation Detection The Geiger counter or Geiger-Müeller counter is used for radiation detection based upon ionizing ability Ionized matter, composed of cations and anions, permit conduction of electrical current Current is related to extent of ionization and eventually radiation exposure This detection method is used for alpha, beta, and gamma

Radiation Detection Scintillation counters utilize fluorescent materials These materials emit visible radiation (light) when struck by radiation The light emission results when electrons drop to lower energy levels after being excited Frequently, specific fluors are selected for specific types of radiation This method provides information regarding the energy of the radiation It being related to the energy of the light emitted e. g. Zn. S – a fluor that is used

Radiation Detection Scintillation counters utilize fluorescent materials These materials emit visible radiation (light) when struck by radiation The light emission results when electrons drop to lower energy levels after being excited Frequently, specific fluors are selected for specific types of radiation This method provides information regarding the energy of the radiation It being related to the energy of the light emitted e. g. Zn. S – a fluor that is used

Radiotracer Use Radioisotopes may be followed through a series of chemical changes The radioactive decay is unaffected by external conditions These radiotracers are frequently used, especially in the medical field e. g protein metabolism, antibiotics, etc.

Radiotracer Use Radioisotopes may be followed through a series of chemical changes The radioactive decay is unaffected by external conditions These radiotracers are frequently used, especially in the medical field e. g protein metabolism, antibiotics, etc.

Nuclear Energy The energy-mass relationship of nuclear reactions was expressed by Einstein’s equation of E = mc 2 The theory indicates a proportionality exists between mass and energy Increases in mass imply increases in energy Converse is true Since the value of c is very large, small changes in mass are related to large changes in energy Note: For the macroscopic world (e. g. chemical changes) the mass changes are too small for detection, therefore, the law of Conservation of Mass holds true. The energy changes associated with nuclear changes is significantly larger than those of chemical changes e. g. The fissioning of 1 Lb. of 235 U equates to the combustion of 1, 500 tons of coal

Nuclear Energy The energy-mass relationship of nuclear reactions was expressed by Einstein’s equation of E = mc 2 The theory indicates a proportionality exists between mass and energy Increases in mass imply increases in energy Converse is true Since the value of c is very large, small changes in mass are related to large changes in energy Note: For the macroscopic world (e. g. chemical changes) the mass changes are too small for detection, therefore, the law of Conservation of Mass holds true. The energy changes associated with nuclear changes is significantly larger than those of chemical changes e. g. The fissioning of 1 Lb. of 235 U equates to the combustion of 1, 500 tons of coal

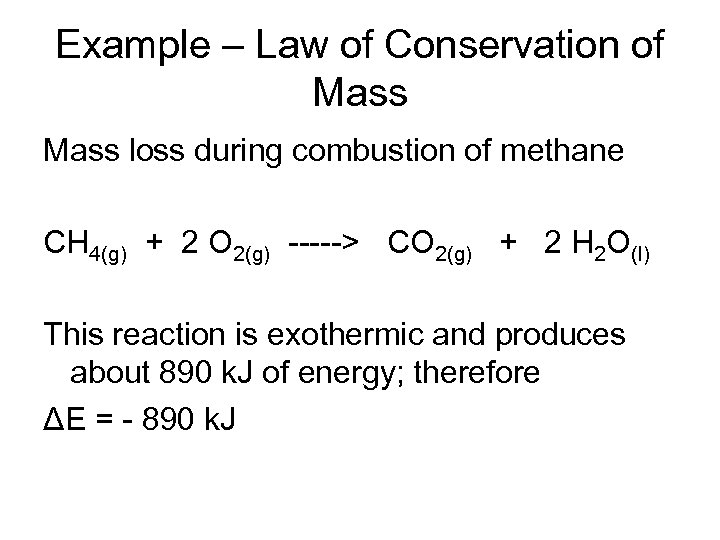

Example – Law of Conservation of Mass loss during combustion of methane CH 4(g) + 2 O 2(g) -----> CO 2(g) + 2 H 2 O(l) This reaction is exothermic and produces about 890 k. J of energy; therefore ΔE = - 890 k. J

Example – Law of Conservation of Mass loss during combustion of methane CH 4(g) + 2 O 2(g) -----> CO 2(g) + 2 H 2 O(l) This reaction is exothermic and produces about 890 k. J of energy; therefore ΔE = - 890 k. J

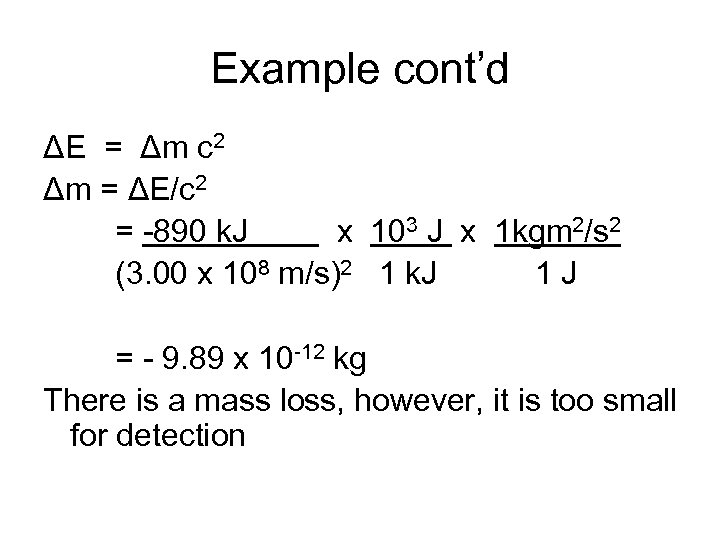

Example cont’d ΔE = Δm c 2 Δm = ΔE/c 2 = -890 k. J x 103 J x 1 kgm 2/s 2 (3. 00 x 108 m/s)2 1 k. J 1 J = - 9. 89 x 10 -12 kg There is a mass loss, however, it is too small for detection

Example cont’d ΔE = Δm c 2 Δm = ΔE/c 2 = -890 k. J x 103 J x 1 kgm 2/s 2 (3. 00 x 108 m/s)2 1 k. J 1 J = - 9. 89 x 10 -12 kg There is a mass loss, however, it is too small for detection

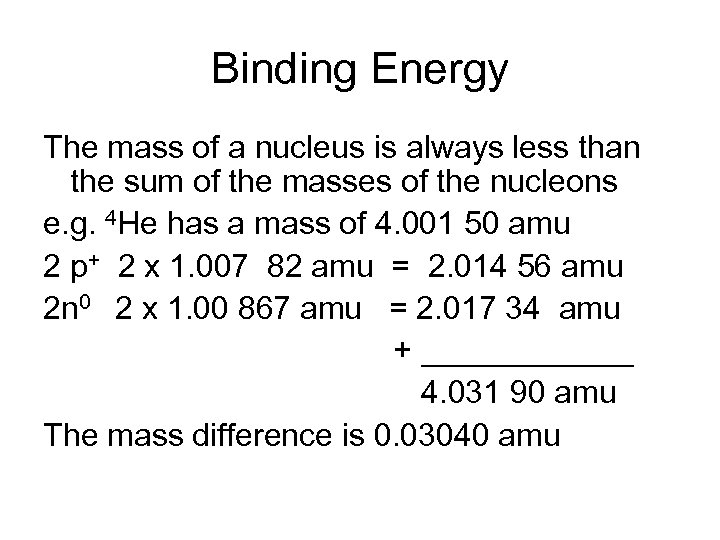

Binding Energy The mass of a nucleus is always less than the sum of the masses of the nucleons e. g. 4 He has a mass of 4. 001 50 amu 2 p+ 2 x 1. 007 82 amu = 2. 014 56 amu 2 n 0 2 x 1. 00 867 amu = 2. 017 34 amu + ______ 4. 031 90 amu The mass difference is 0. 03040 amu

Binding Energy The mass of a nucleus is always less than the sum of the masses of the nucleons e. g. 4 He has a mass of 4. 001 50 amu 2 p+ 2 x 1. 007 82 amu = 2. 014 56 amu 2 n 0 2 x 1. 00 867 amu = 2. 017 34 amu + ______ 4. 031 90 amu The mass difference is 0. 03040 amu

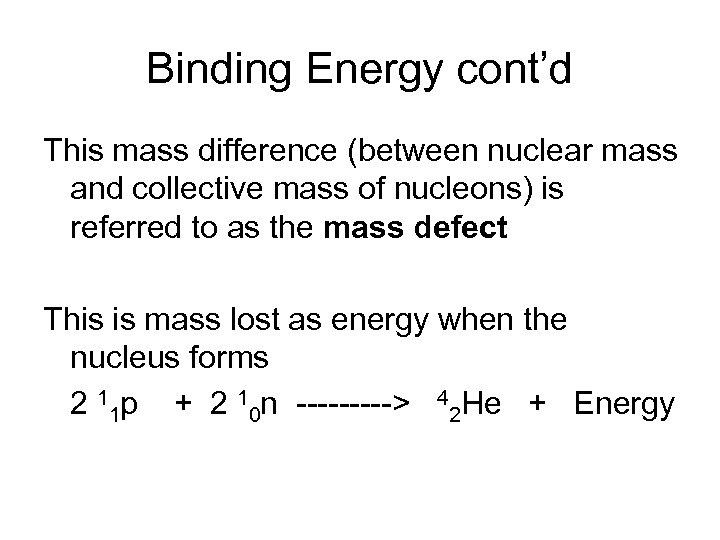

Binding Energy cont’d This mass difference (between nuclear mass and collective mass of nucleons) is referred to as the mass defect This is mass lost as energy when the nucleus forms 2 11 p + 2 10 n -----> 42 He + Energy

Binding Energy cont’d This mass difference (between nuclear mass and collective mass of nucleons) is referred to as the mass defect This is mass lost as energy when the nucleus forms 2 11 p + 2 10 n -----> 42 He + Energy

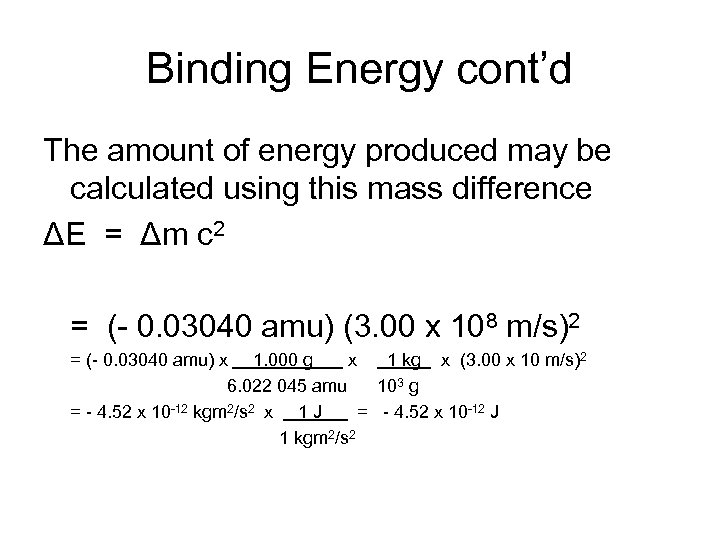

Binding Energy cont’d The amount of energy produced may be calculated using this mass difference ΔE = Δm c 2 = (- 0. 03040 amu) (3. 00 x 108 m/s)2 = (- 0. 03040 amu) x 1. 000 g x 1 kg x (3. 00 x 10 m/s)2 6. 022 045 amu 103 g = - 4. 52 x 10 -12 kgm 2/s 2 x 1 J = - 4. 52 x 10 -12 J 1 kgm 2/s 2

Binding Energy cont’d The amount of energy produced may be calculated using this mass difference ΔE = Δm c 2 = (- 0. 03040 amu) (3. 00 x 108 m/s)2 = (- 0. 03040 amu) x 1. 000 g x 1 kg x (3. 00 x 10 m/s)2 6. 022 045 amu 103 g = - 4. 52 x 10 -12 kgm 2/s 2 x 1 J = - 4. 52 x 10 -12 J 1 kgm 2/s 2

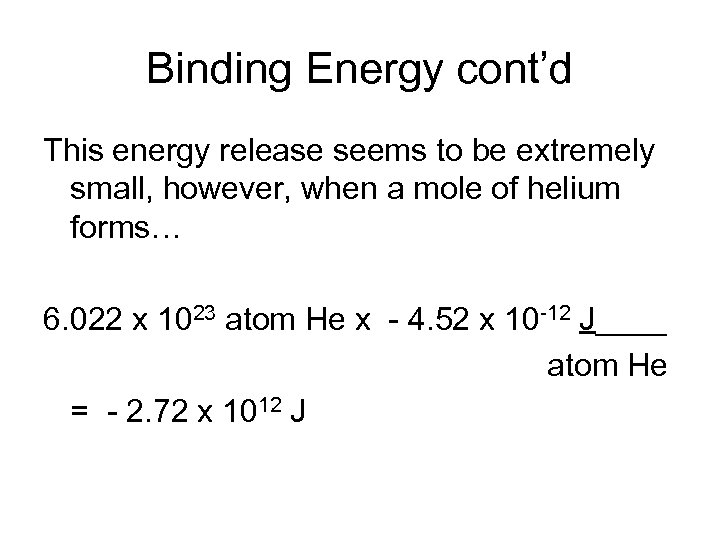

Binding Energy cont’d This energy release seems to be extremely small, however, when a mole of helium forms… 6. 022 x 1023 atom He x - 4. 52 x 10 -12 J____ atom He = - 2. 72 x 1012 J

Binding Energy cont’d This energy release seems to be extremely small, however, when a mole of helium forms… 6. 022 x 1023 atom He x - 4. 52 x 10 -12 J____ atom He = - 2. 72 x 1012 J

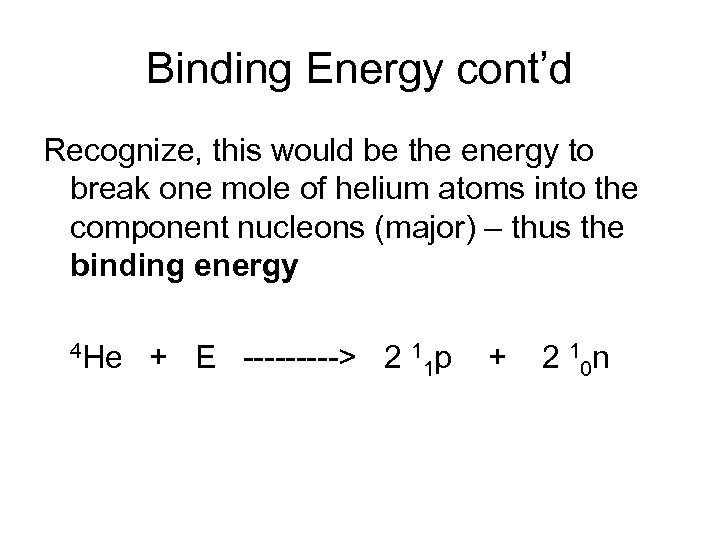

Binding Energy cont’d Recognize, this would be the energy to break one mole of helium atoms into the component nucleons (major) – thus the binding energy 4 He + E -----> 2 1 p + 2 10 n 1

Binding Energy cont’d Recognize, this would be the energy to break one mole of helium atoms into the component nucleons (major) – thus the binding energy 4 He + E -----> 2 1 p + 2 10 n 1

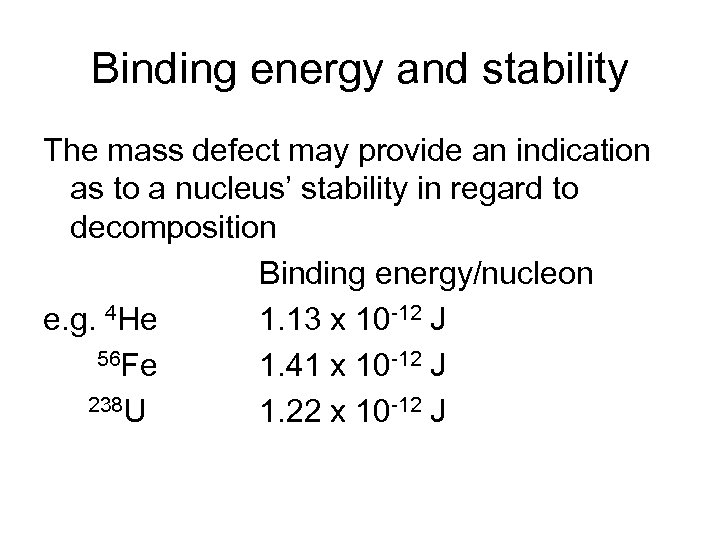

Binding energy and stability The mass defect may provide an indication as to a nucleus’ stability in regard to decomposition Binding energy/nucleon e. g. 4 He 1. 13 x 10 -12 J 56 Fe 1. 41 x 10 -12 J 238 U 1. 22 x 10 -12 J

Binding energy and stability The mass defect may provide an indication as to a nucleus’ stability in regard to decomposition Binding energy/nucleon e. g. 4 He 1. 13 x 10 -12 J 56 Fe 1. 41 x 10 -12 J 238 U 1. 22 x 10 -12 J

Binding energy and stability Binding energy tends to increase to about 1. 41 x 10 -12 J/nucleon, a maximum, for mass numbers around 56 It slowly decreases in value moving towards heavier nuclei, reaching a low of about 1. 2 x 10 -12 J/nucleon This indicates heavier nuclei are slowly increasing in stability If fragmented in a process like nuclear fission, these nuclei give off energy which may then be used as in nuclear power plants, etc. Fusion of lighter nuclei will produce even greater amounts of energy

Binding energy and stability Binding energy tends to increase to about 1. 41 x 10 -12 J/nucleon, a maximum, for mass numbers around 56 It slowly decreases in value moving towards heavier nuclei, reaching a low of about 1. 2 x 10 -12 J/nucleon This indicates heavier nuclei are slowly increasing in stability If fragmented in a process like nuclear fission, these nuclei give off energy which may then be used as in nuclear power plants, etc. Fusion of lighter nuclei will produce even greater amounts of energy

Effects of Radiations frequently carry greater energy than that resulting from chemical change Radiation travels through matter imparting energy as it does so This energy may cause ionization or fragmentation of molecules As a result, these ionized or molecular fragments are very reactive and as a result may proceed to disrupt cellular function

Effects of Radiations frequently carry greater energy than that resulting from chemical change Radiation travels through matter imparting energy as it does so This energy may cause ionization or fragmentation of molecules As a result, these ionized or molecular fragments are very reactive and as a result may proceed to disrupt cellular function

Penetration of Radiation damage often depends upon the extent to which the radiation penetrates the living tissue Both gamma and x-rays have very good penetrating capabilities As a result their damage exceeds skin level Alpha rays are stopped by the skin and beta rays may reach a depth of 1 cm These may cause disorders of the dermal region of the body However, if either of these radiations enter the body, they may be more dangerous than gamma Inside the body, these radiations may create tissue and cellular damage due to their ionizing capabilities, especially alpha

Penetration of Radiation damage often depends upon the extent to which the radiation penetrates the living tissue Both gamma and x-rays have very good penetrating capabilities As a result their damage exceeds skin level Alpha rays are stopped by the skin and beta rays may reach a depth of 1 cm These may cause disorders of the dermal region of the body However, if either of these radiations enter the body, they may be more dangerous than gamma Inside the body, these radiations may create tissue and cellular damage due to their ionizing capabilities, especially alpha

Retention Time Often, the chemical form of the radioisotope determines its ease for entering the body and the time it is retained e. g. 85 Kr – a product of nuclear fissioning of uranium -it is chemically inert therefore, it cannot be eliminated by chemical reaction - it is gaseous, therefore, it may enter the skin and lungs - lack of reactivity, however, keeps it moving through the body and being expelled

Retention Time Often, the chemical form of the radioisotope determines its ease for entering the body and the time it is retained e. g. 85 Kr – a product of nuclear fissioning of uranium -it is chemically inert therefore, it cannot be eliminated by chemical reaction - it is gaseous, therefore, it may enter the skin and lungs - lack of reactivity, however, keeps it moving through the body and being expelled

Retention Time cont’d e. g. 90 Sr – product of fissioning of uranium - it is chemically active (alkaline earth) - able to replace calcium with ease - therefore, may displace calcium in the bones and be retained there - as a result, it may cause bone cancer or leukemia

Retention Time cont’d e. g. 90 Sr – product of fissioning of uranium - it is chemically active (alkaline earth) - able to replace calcium with ease - therefore, may displace calcium in the bones and be retained there - as a result, it may cause bone cancer or leukemia

Biological Concentration Recognize, as certain substances are transferred through the food chain, concentration of the substances may increase e. g. 40 K found in soils may be taken up by grass – eventually consumed by cows and entering their milk – eventually consumed by humans, etc.

Biological Concentration Recognize, as certain substances are transferred through the food chain, concentration of the substances may increase e. g. 40 K found in soils may be taken up by grass – eventually consumed by cows and entering their milk – eventually consumed by humans, etc.

Radiation Damage Biologically, radiation damage is classified as somatic or genetic Somatic damage – this damage is limited to affecting the organism during its lifetime May result in burns, cellular disruptions, or cancer Cancer results from damage to the growth regulation mechanism of cells It appears as uncontrolled reproduction of certain cells The greatest damage is observed in those tissues that rapidly reproduce e. g. bone marrow, lymph nodes, blood forming tissue, etc.

Radiation Damage Biologically, radiation damage is classified as somatic or genetic Somatic damage – this damage is limited to affecting the organism during its lifetime May result in burns, cellular disruptions, or cancer Cancer results from damage to the growth regulation mechanism of cells It appears as uncontrolled reproduction of certain cells The greatest damage is observed in those tissues that rapidly reproduce e. g. bone marrow, lymph nodes, blood forming tissue, etc.

Radiation Damage Genetic damage – this damages some part of the genetic system As a result, the genes and chromosomes of the offspring will be affected This damage may be difficult to detect as generations may pass before it becomes apparent

Radiation Damage Genetic damage – this damages some part of the genetic system As a result, the genes and chromosomes of the offspring will be affected This damage may be difficult to detect as generations may pass before it becomes apparent

Exposure Length Short term (acute) exposure may result in the following clinical symptoms: Reduction in white blood cells Fatigue, nausea, diarrhea Sufficient exposure may result in death from blood disorders, gastrointestinal failure, or damage to the central nervous system

Exposure Length Short term (acute) exposure may result in the following clinical symptoms: Reduction in white blood cells Fatigue, nausea, diarrhea Sufficient exposure may result in death from blood disorders, gastrointestinal failure, or damage to the central nervous system

Exposure Length Two models have been proposed to evaluate exposure Linear model – demonstrates the effects of ionizing radiation being proportional to duration of exposure Threshold model – indicates no effects due to ionizing radiation below a certain “threshold” of exposure The linear model is generally more accepted The implication is there is always some finite risk of damage

Exposure Length Two models have been proposed to evaluate exposure Linear model – demonstrates the effects of ionizing radiation being proportional to duration of exposure Threshold model – indicates no effects due to ionizing radiation below a certain “threshold” of exposure The linear model is generally more accepted The implication is there is always some finite risk of damage

Units of Radiation Dosage Curie – a unit equivalent to a decay rate of 3. 7 x 1010 decays per second - it is a unit for measuring radioactivity - symbol of Ci - obtained from the standard of 1. 00 g Ra which decays at 3. 7 x 1010 decays/s

Units of Radiation Dosage Curie – a unit equivalent to a decay rate of 3. 7 x 1010 decays per second - it is a unit for measuring radioactivity - symbol of Ci - obtained from the standard of 1. 00 g Ra which decays at 3. 7 x 1010 decays/s

Units of Radiation Dosage Rad – “radiation absorbed dose” describes an amount of radiation capable of depositing 1 x 10 -2 J of energy per kilogram of tissue - used for measuring energy imparted by ionizing radiation to matter - imparts 100 ergs per gram of matter (1 erg = 1 x 10 -7 J)

Units of Radiation Dosage Rad – “radiation absorbed dose” describes an amount of radiation capable of depositing 1 x 10 -2 J of energy per kilogram of tissue - used for measuring energy imparted by ionizing radiation to matter - imparts 100 ergs per gram of matter (1 erg = 1 x 10 -7 J)

Units of Radiation Dosage Roentgen Equivalent Physical (REP) - amount of ionizing radiation able to produce 1. 615 x 1012 ion pairs per gram of tissue - amount of ionizing radiation able to impart 93 egrs of energy per gram of matter - used primarily for β-

Units of Radiation Dosage Roentgen Equivalent Physical (REP) - amount of ionizing radiation able to produce 1. 615 x 1012 ion pairs per gram of tissue - amount of ionizing radiation able to impart 93 egrs of energy per gram of matter - used primarily for β-

Units of Radiation Dosage Roentgen Equivalent Man (rem) - the rad is often multiplied by a factor RBE to determine the effect of each radiation with regard to its biological damage RBE – relative biological effectiveness factor RBE – varies with dose rate, total dose, type of tissue affected, & type of radiation RBE is about one for β- and γ RBE is about ten for x-rays

Units of Radiation Dosage Roentgen Equivalent Man (rem) - the rad is often multiplied by a factor RBE to determine the effect of each radiation with regard to its biological damage RBE – relative biological effectiveness factor RBE – varies with dose rate, total dose, type of tissue affected, & type of radiation RBE is about one for β- and γ RBE is about ten for x-rays

Units of Radiation Dosage REM cont’d - the product of RBE and rads produces an effective dosage in rems = # rads x RBE For short term exposure: 0 – 25 rems – no clinical effects 500 rem – death within half of an exposed population

Units of Radiation Dosage REM cont’d - the product of RBE and rads produces an effective dosage in rems = # rads x RBE For short term exposure: 0 – 25 rems – no clinical effects 500 rem – death within half of an exposed population

Units of Radiation Dosage Rem cont’d Background radiation provides us with an average of 0. 1 to 0. 2 rems per year of low level long term radiation - this may vary pending upon region of residence, house design, elevation (greater cosmic), human activity, etc.

Units of Radiation Dosage Rem cont’d Background radiation provides us with an average of 0. 1 to 0. 2 rems per year of low level long term radiation - this may vary pending upon region of residence, house design, elevation (greater cosmic), human activity, etc.

Units of Radiation Dosage Radiation exposure limits (EPA generated): General population – 500 mrem per annum Occupational population – 5 rem per annum excluding background exposures General industrial operating philosophy – ALARA - As Low As Reasonably Achievable Unrestricted areas – permit 0. 5 rem/yr Restricted areas – permit 5 rem/yr Lifetime dosage – (Your age – 18) x 5 rem

Units of Radiation Dosage Radiation exposure limits (EPA generated): General population – 500 mrem per annum Occupational population – 5 rem per annum excluding background exposures General industrial operating philosophy – ALARA - As Low As Reasonably Achievable Unrestricted areas – permit 0. 5 rem/yr Restricted areas – permit 5 rem/yr Lifetime dosage – (Your age – 18) x 5 rem

Personal Dosimeters TLD – thermal luminous dosimeter - compound like Li. F crystal when struck by radiation it excites electrons in crystal moving AND holding them in positions of elevated energy - crystal is heated which then permits electrons to drop to lower energy levels by releasing absorbed energy - the released energy is measured and recorded

Personal Dosimeters TLD – thermal luminous dosimeter - compound like Li. F crystal when struck by radiation it excites electrons in crystal moving AND holding them in positions of elevated energy - crystal is heated which then permits electrons to drop to lower energy levels by releasing absorbed energy - the released energy is measured and recorded

TLD

TLD

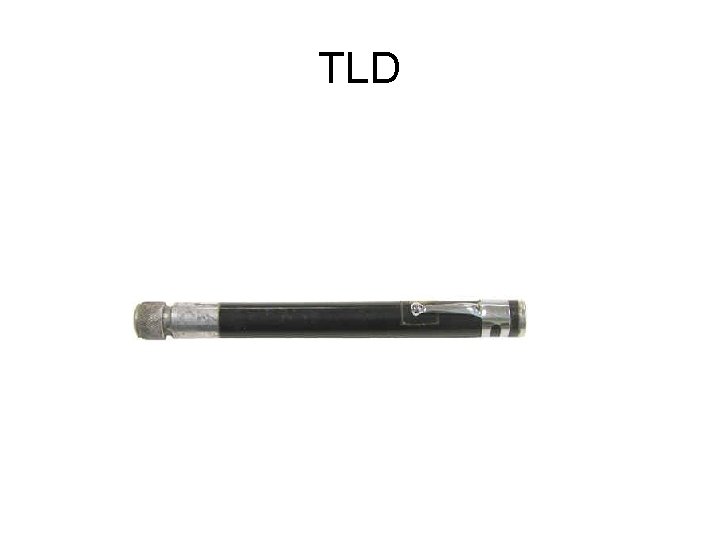

Personal Dosimeters Film badges - piece of film is placed in a badge and worn on site - radiation causes film exposures - film is developed and exposures counted

Personal Dosimeters Film badges - piece of film is placed in a badge and worn on site - radiation causes film exposures - film is developed and exposures counted

Film Badge

Film Badge

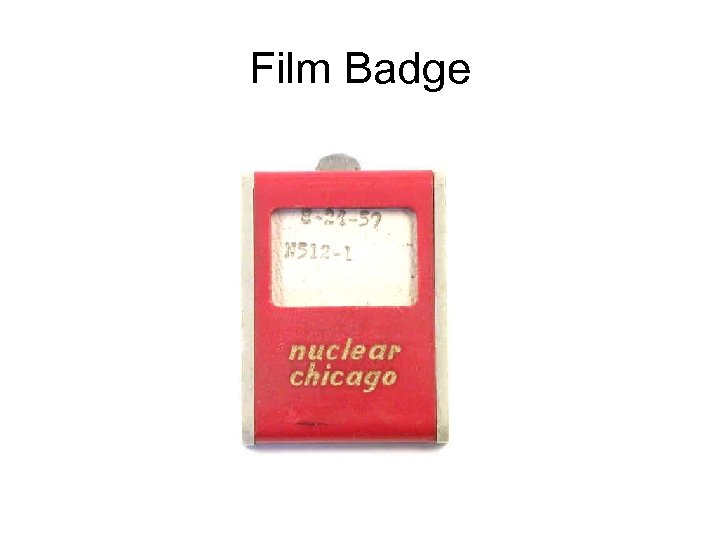

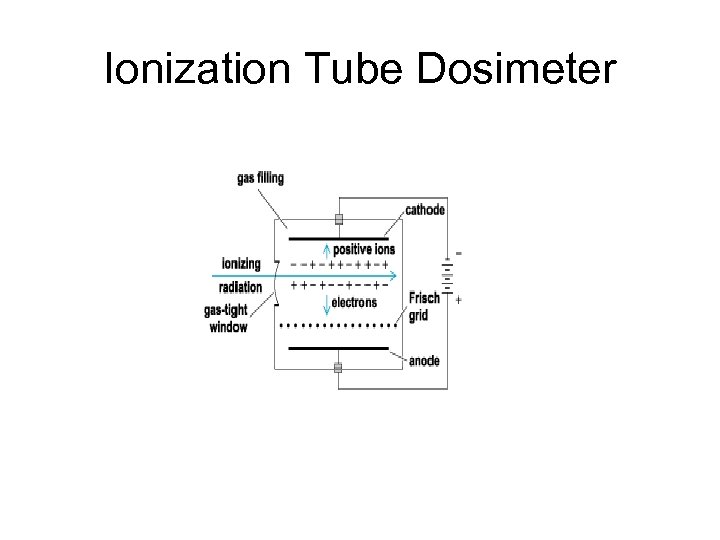

Ionization Tube Dosimeter Radiation enters the tube causing ionzation of gas within the tube which builds up electrical charge This electrical charge build-up is measured and monitored to determine radiation exposure S

Ionization Tube Dosimeter Radiation enters the tube causing ionzation of gas within the tube which builds up electrical charge This electrical charge build-up is measured and monitored to determine radiation exposure S

Exposure on the Skin Type 1 – erythema (reddening) -a few hundred to a thousand rads Type 2 – wet desquamation (blisters) -1, 000 to 2, 000 rads Type 3 – conditions similar to a scald or chemical burn - greater than 2, 000 rads Type 4 – ulceration usually accompanied by skin cancer - frequent exposures of greater than 1 rad per dose

Exposure on the Skin Type 1 – erythema (reddening) -a few hundred to a thousand rads Type 2 – wet desquamation (blisters) -1, 000 to 2, 000 rads Type 3 – conditions similar to a scald or chemical burn - greater than 2, 000 rads Type 4 – ulceration usually accompanied by skin cancer - frequent exposures of greater than 1 rad per dose

Whole Body Exposure 50 rads – blood alteration 100 rads – nausea with vomiting 200 rads – moderate radiation sickness 300 – 400 rads – severe radiation sickness resulting in the death of ~50 %of population 600 rads – death in 1 to 2 weeks

Whole Body Exposure 50 rads – blood alteration 100 rads – nausea with vomiting 200 rads – moderate radiation sickness 300 – 400 rads – severe radiation sickness resulting in the death of ~50 %of population 600 rads – death in 1 to 2 weeks

Ionization Tube Dosimeter

Ionization Tube Dosimeter