ff1c7be991804d6ba4a86867b8e14b72.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 79

NOVEL BIOMARKERS and CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE Nathan D Wong, Ph. D, FACC Professor and Director Heart Disease Prevention Program University of California, Irvine

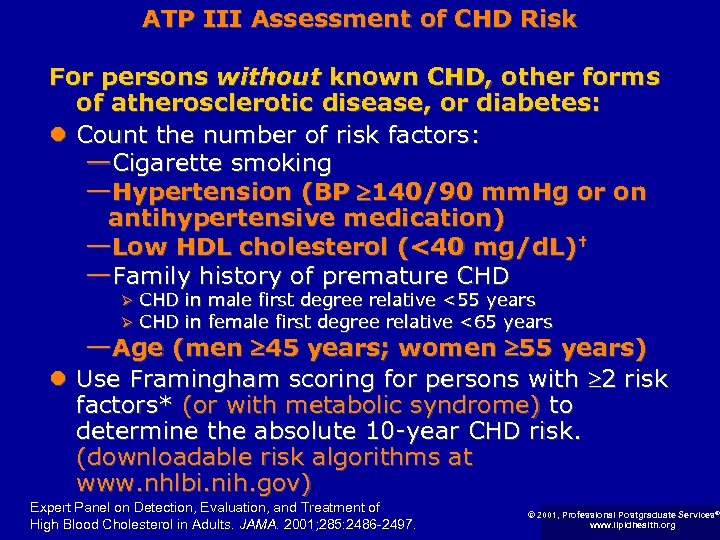

ATP III Assessment of CHD Risk For persons without known CHD, other forms of atherosclerotic disease, or diabetes: l Count the number of risk factors: —Cigarette smoking —Hypertension (BP 140/90 mm. Hg or on antihypertensive medication) —Low HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/d. L)† —Family history of premature CHD Ø Ø CHD in male first degree relative <55 years CHD in female first degree relative <65 years —Age (men 45 years; women 55 years) l Use Framingham scoring for persons with 2 risk factors* (or with metabolic syndrome) to determine the absolute 10 -year CHD risk. (downloadable risk algorithms at www. nhlbi. nih. gov) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. JAMA. 2001; 285: 2486 -2497. © 2001, Professional Postgraduate Services® www. lipidhealth. org

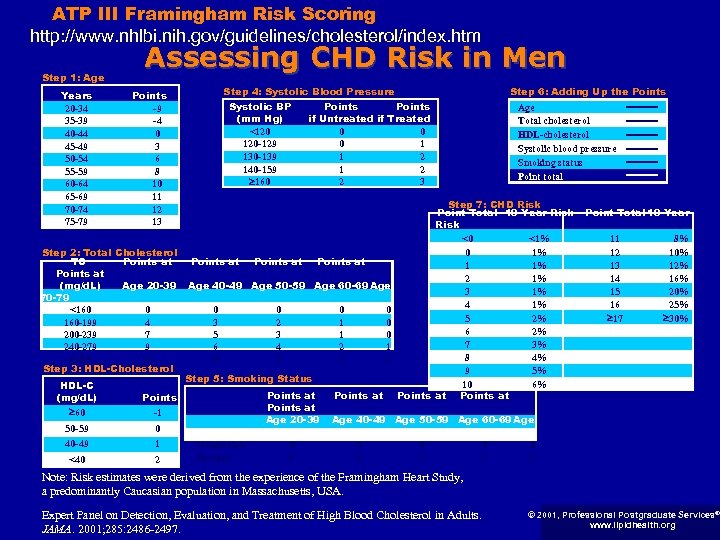

ATP III Framingham Risk Scoring http: //www. nhlbi. nih. gov/guidelines/cholesterol/index. htm Step 1: Age Years 20 -34 35 -39 40 -44 45 -49 50 -54 55 -59 60 -64 65 -69 70 -74 75 -79 Assessing CHD Risk in Men Step 4: Systolic Blood Pressure Points -9 -4 0 3 6 8 10 11 12 13 Step 2: Total Cholesterol TC Points at (mg/d. L) Age 20 -39 70 -79 <160 0 160 -199 4 200 -239 7 240 -279 9 280 11 Step 3: HDL-Cholesterol HDL-C (mg/d. L) 60 0 40 -49 1 <40 2 Points at Points if Untreated if Treated 0 0 0 1 1 2 2 3 Points at Age 40 -49 Age 50 -59 Age 60 -69 Age 0 3 5 6 8 0 2 3 4 5 0 1 1 2 3 0 0 0 1 1 Step 5: Smoking Status Points -1 50 -59 Systolic BP (mm Hg) <120 120 -129 130 -139 140 -159 160 70 -79 Nonsmoker Smoker Points at Age 20 -39 0 8 Step 6: Adding Up the Points at Age Total cholesterol HDL-cholesterol Systolic blood pressure Smoking status Point total Step 7: CHD Risk Point Total 10 -Year Risk <0 <1% 0 1% 1 1% 2 1% 3 1% 4 1% 5 2% 6 2% 7 3% 8 4% 9 5% 10 6% Points at Point Total 10 -Year 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 8% 10% 12% 16% 20% 25% 30% Age 40 -49 Age 50 -59 Age 60 -69 Age 0 5 0 3 0 1 Note: Risk estimates were derived from the experience of the Framingham Heart Study, a predominantly Caucasian population in Massachusetts, USA. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. JAMA. 2001; 285: 2486 -2497. © 2001, Professional Postgraduate Services® www. lipidhealth. org

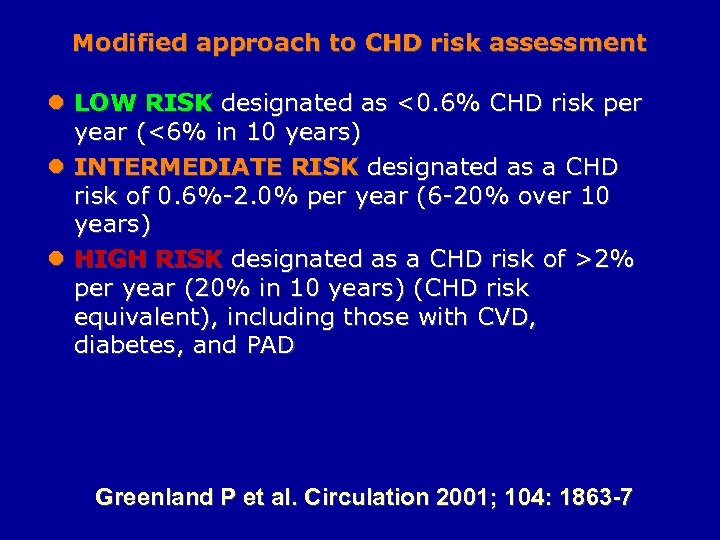

Modified approach to CHD risk assessment l LOW RISK designated as <0. 6% CHD risk per year (<6% in 10 years) l INTERMEDIATE RISK designated as a CHD risk of 0. 6%-2. 0% per year (6 -20% over 10 years) l HIGH RISK designated as a CHD risk of >2% per year (20% in 10 years) (CHD risk equivalent), including those with CVD, diabetes, and PAD Greenland P et al. Circulation 2001; 104: 1863 -7

Presentation l Examination: — Height: 6 ft 2 in — Weight: 220 lb (BMI 28 kg/m 2) — Waist circumference: 41 in — BP: 150/88 mm Hg — P: 64 bpm — RR: 12 breaths/min l Cardiopulmonary exam: normal l Laboratory results: — TC: 220 mg/d. L — HDL-C: 36 mg/d. L — LDL-C: 140 mg/d. L — TG: 220 mg/d. L — FBS: 120 mg/d. L

What is WJC’s 10 -year absolute risk of fatal/nonfatal MI? l A 12% absolute risk is derived from points assigned in Framingham Risk Scoring to: — Age: 6 — TC: 3 — HDL-C: 2 — SBP: 2 — Total: 13 points In 1992 he exercised 14 minutes in a Bruce protocol exercise stress test to 91% of his maximum predicted heart rate without any abnormal ECG changes. He started on a statin in 2001. But in Sept 2004, he needed urgent coronary bypass surgery.

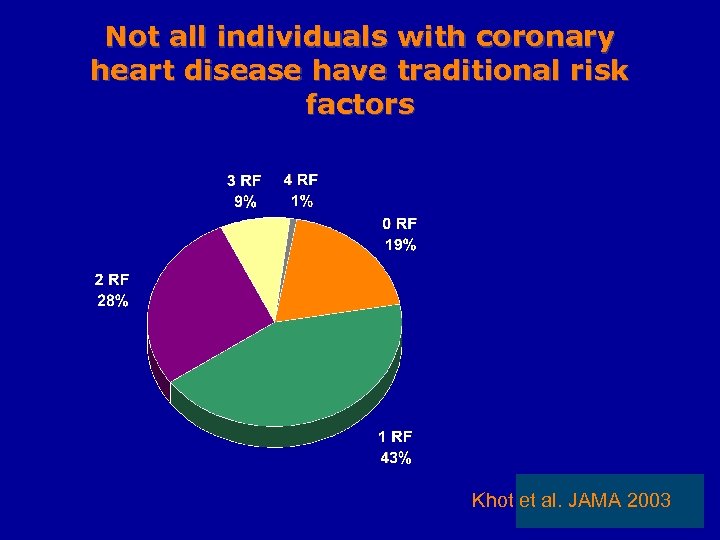

Not all individuals with coronary heart disease have traditional risk factors Khot et al. JAMA 2003

The Detection Gap in CHD “Despite many available risk assessment approaches, a substantial gap remains in the detection of asymptomatic individuals who ultimately develop CHD” “The Framingham and European risk scores… emphasize the classic CHD risk factors…. is only moderately accurate for the prediction of short- and long-term risk of manifesting a major coronary artery event…” Pasternak and Abrams et al. 34 th Bethesda conf. JACC 2003; 41: 1855 -1917

Is there clinical evidence that novel risk markers predict future coronary events and provide additional predictive information beyond traditional risk factors?

Fibrinogen and Atherosclerosis l l l l Promotes atherosclerosis Essential component of platelet aggregation Relates to fibrin deposited and the size of the clot Increases plasma viscosity May also have a proinflammatory role Measurement of fibrinogen, incl. Test variability, remains difficult. No known therapies to selectively lower fibrinogen levels in order to test efficacy in CHD risk reduction via clinical trials.

Fibrinogen and CHD Risk: Epidemiologic Studies l Recent meta-analysis of 18 studies involving 4018 CHD cases showed a relative risk of CHD of 1. 8 (95% CI 1. 6 -2. 0) comparing the highest vs lowest tertile of fibrinogen levels (mean. 35 vs. . 25 g/d. L) l ARIC study in 14, 477 adults aged 45 -64 showed relative risks of 1. 8 in men and 1. 5 in women, attenuated to 1. 5 and 1. 2 after risk factor adjustment. l Scottish Heart Health Study of 5095 men and 4860 women showed fibrinogen to be an independent risk factor for new events--RRs 2. 2 -3. 4 for coronary death and all-cause mortality.

Fibrinogen and CHD Risk Factors l Fibrinogen levels increase with age and body mass index, and higher cholesterol levels l Smoking can reversibly elevated fibrinogen levels, and cessation of smoking can lower fibrinogen. l Those who exercise, eat vegetarian diets, and consume alcohol have lower levels. Exercise may also lower fibrinogen and plasma viscosity. l Studies also show statin-fibrate combinations (simvastatin-ciprofibrate) and estrogen therapy to lower fibrinogen.

P. Ridker

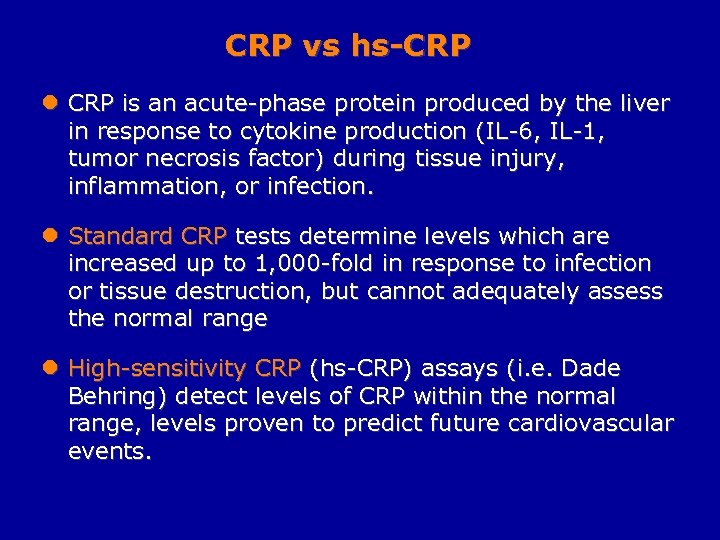

CRP vs hs-CRP l CRP is an acute-phase protein produced by the liver in response to cytokine production (IL-6, IL-1, tumor necrosis factor) during tissue injury, inflammation, or infection. l Standard CRP tests determine levels which are increased up to 1, 000 -fold in response to infection or tissue destruction, but cannot adequately assess the normal range l High-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) assays (i. e. Dade Behring) detect levels of CRP within the normal range, levels proven to predict future cardiovascular events.

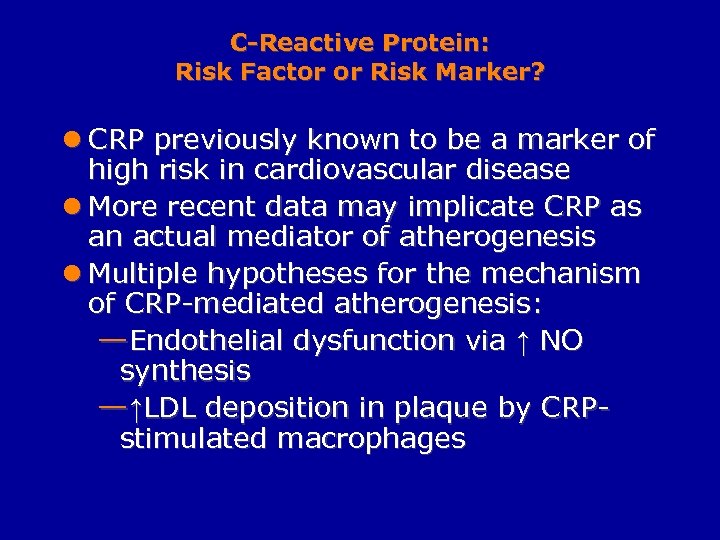

C-Reactive Protein: Risk Factor or Risk Marker? l CRP previously known to be a marker of high risk in cardiovascular disease l More recent data may implicate CRP as an actual mediator of atherogenesis l Multiple hypotheses for the mechanism of CRP-mediated atherogenesis: —Endothelial dysfunction via ↑ NO synthesis —↑LDL deposition in plaque by CRPstimulated macrophages

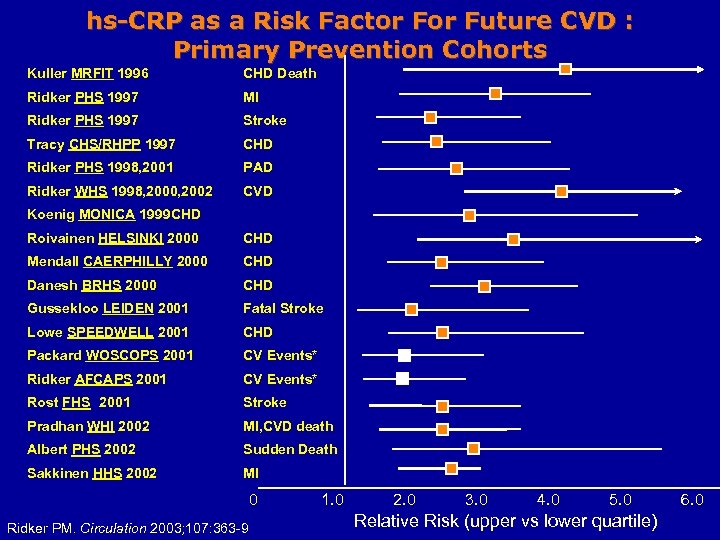

hs-CRP as a Risk Factor Future CVD : Primary Prevention Cohorts Kuller MRFIT 1996 CHD Death Ridker PHS 1997 MI Ridker PHS 1997 Stroke Tracy CHS/RHPP 1997 CHD Ridker PHS 1998, 2001 PAD Ridker WHS 1998, 2000, 2002 CVD Koenig MONICA 1999 CHD Roivainen HELSINKI 2000 CHD Mendall CAERPHILLY 2000 CHD Danesh BRHS 2000 CHD Gussekloo LEIDEN 2001 Fatal Stroke Lowe SPEEDWELL 2001 CHD Packard WOSCOPS 2001 CV Events* Ridker AFCAPS 2001 CV Events* Rost FHS 2001 Stroke Pradhan WHI 2002 MI, CVD death Albert PHS 2002 Sudden Death Sakkinen HHS 2002 MI 0 Ridker PM. Circulation 2003; 107: 363 -9 1. 0 2. 0 3. 0 4. 0 5. 0 Relative Risk (upper vs lower quartile) 6. 0

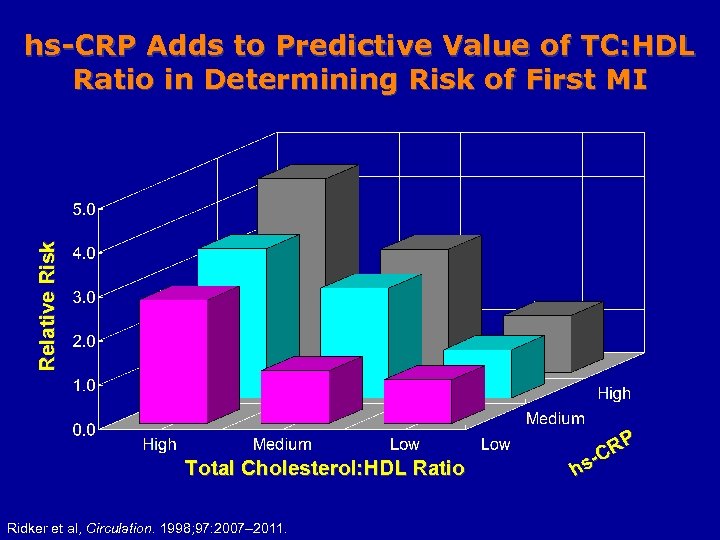

Relative Risk hs-CRP Adds to Predictive Value of TC: HDL Ratio in Determining Risk of First MI Total Cholesterol: HDL Ratio Ridker et al, Circulation. 1998; 97: 2007– 2011. RP s-C h

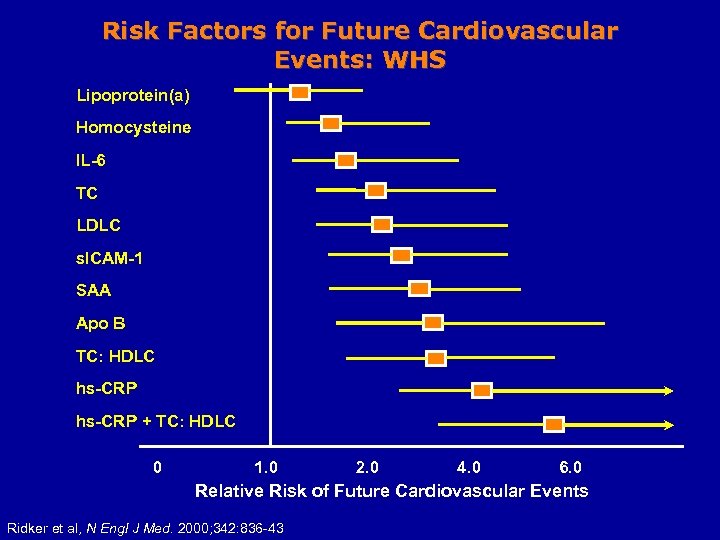

Risk Factors for Future Cardiovascular Events: WHS Lipoprotein(a) Homocysteine IL-6 TC LDLC s. ICAM-1 SAA Apo B TC: HDLC hs-CRP + TC: HDLC 0 1. 0 2. 0 4. 0 6. 0 Relative Risk of Future Cardiovascular Events Ridker et al, N Engl J Med. 2000; 342: 836 -43

Is there clinical evidence that inflammation can be modified by preventive therapies?

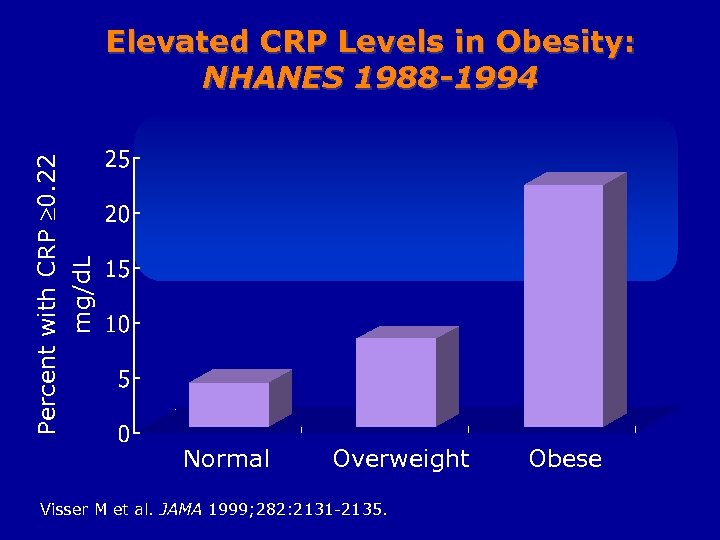

Percent with CRP 0. 22 mg/d. L Elevated CRP Levels in Obesity: NHANES 1988 -1994 Normal Overweight Visser M et al. JAMA 1999; 282: 2131 -2135. Obese

Effects of Weight Loss on CRP Concentrations in Obese Healthy Women n 83 women (mean BMI 33. 8, range 28. 2 -43. 8 kg/m 2) placed on very low fat, energy-restricted diet (6. 0 MJ, 15% fat) for 12 weeks n Baseline CRP positively associated with BMI (r=0. 281, p=0. 01) n CRP reduced by 26% (p<0. 001) n Average weight loss 7. 9 kg, associated with change in CRP n Change in CRP correlated with change in TC (r=0. 240, p=0. 03) but not changes in LDL-C, HDL-C, or glucose n At 12 weeks, CRP concentration highly correlated with TG (r=0. 287, p=0. 009), but not with other lipids or glucose Heilbronn LK et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21: 968 -970.

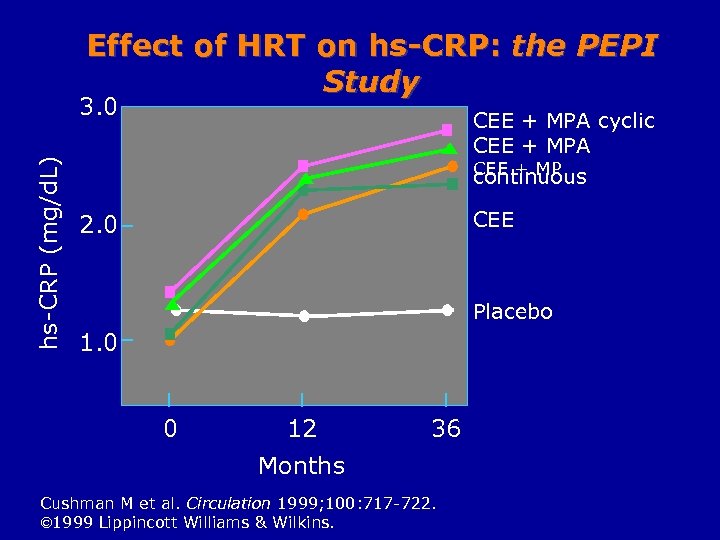

Effect of HRT on hs-CRP: the PEPI Study hs-CRP (mg/d. L) 3. 0 CEE + MPA cyclic CEE + MPA CEE + MP continuous CEE 2. 0 Placebo 1. 0 0 12 36 Months Cushman M et al. Circulation 1999; 100: 717 -722. 1999 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

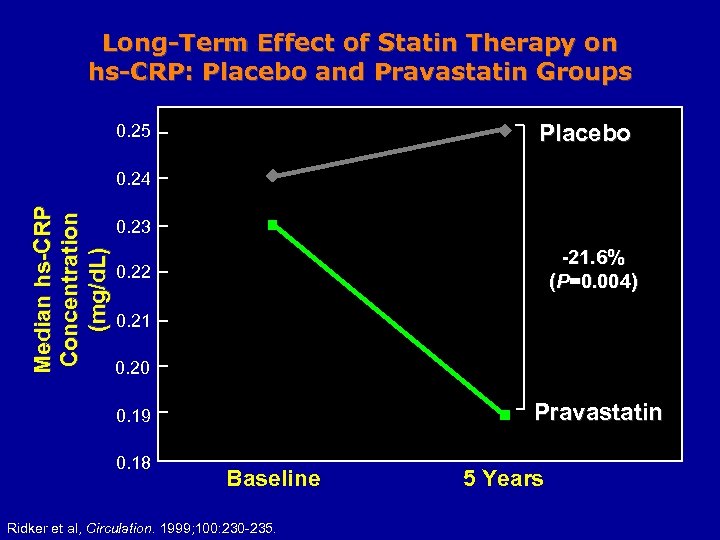

Long-Term Effect of Statin Therapy on hs-CRP: Placebo and Pravastatin Groups Placebo 0. 25 Median hs-CRP Concentration (mg/d. L) 0. 24 0. 23 -21. 6% (P=0. 004) 0. 22 0. 21 0. 20 Pravastatin 0. 19 0. 18 Baseline Ridker et al, Circulation. 1999; 100: 230 -235. 5 Years

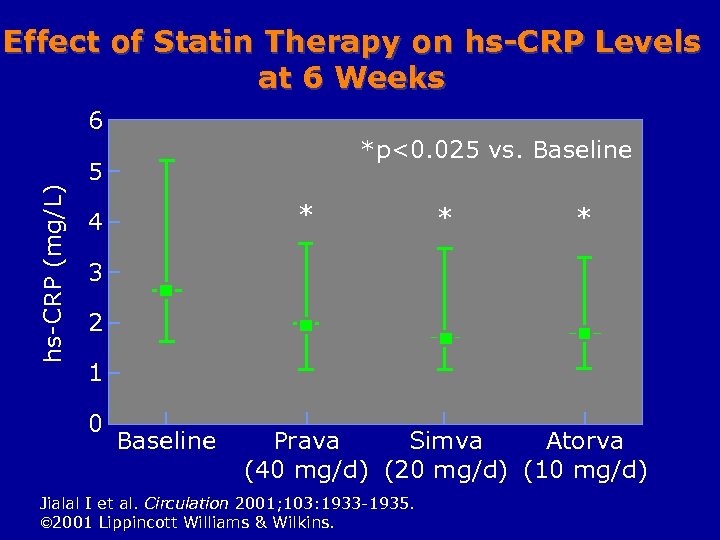

Effect of Statin Therapy on hs-CRP Levels at 6 Weeks hs-CRP (mg/L) 6 *p<0. 025 vs. Baseline 5 * 4 * * 3 2 1 0 Baseline Prava Simva Atorva (40 mg/d) (20 mg/d) (10 mg/d) Jialal I et al. Circulation 2001; 103: 1933 -1935. 2001 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

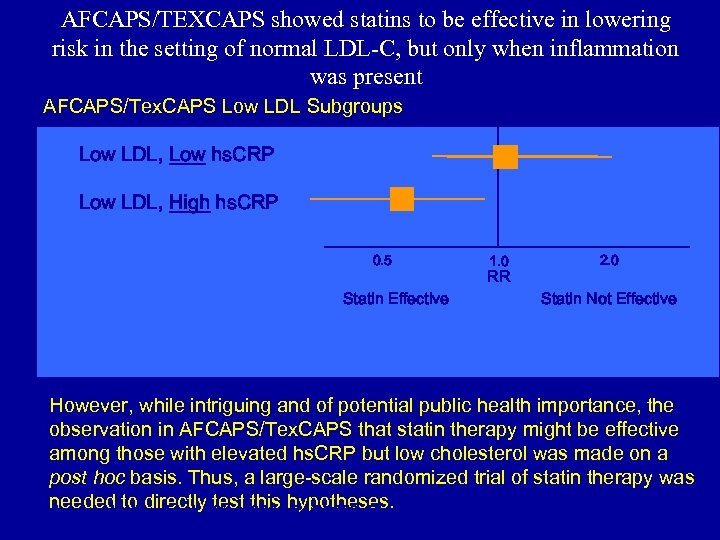

AFCAPS/TEXCAPS showed statins to be effective in lowering risk in the setting of normal LDL-C, but only when inflammation was present AFCAPS/Tex. CAPS Low LDL Subgroups Low LDL, Low hs. CRP [A] Low LDL, High hs. CRP [B] 0. 5 Statin Effective 1. 0 RR 2. 0 Statin Not Effective However, while intriguing and of potential public health importance, the observation in AFCAPS/Tex. CAPS that statin therapy might be effective among those with elevated hs. CRP but low cholesterol was made on a post hoc basis. Thus, a large-scale randomized trial of statin therapy was needed to directly test this hypotheses. Ridker et al, New Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1959 -65

A Randomized Trial of Rosuvastatin in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Events Among 17, 802 Apparently Healthy Men and Women With Elevated Levels of C-Reactive Protein (hs. CRP): The JUPITER Trial Paul Ridker*, Eleanor Danielson, Francisco Fonseca*, Jacques Genest*, Antonio Gotto*, John Kastelein*, Wolfgang Koenig*, Peter Libby*, Alberto Lorenzatti*, Jean Mac. Fadyen, Borge Nordestgaard*, James Shepherd*, James Willerson, and Robert Glynn* on behalf of the JUPITER Trial Study Group An Investigator Initiated Trial Funded by Astra. Zeneca, USA * These authors have received research grant support and/or consultation fees from one or more statin manufacturers, including Astra-Zeneca. Dr Ridker is a co-inventor on patents held by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital that relate to the use of inflammatory biomarkers in cardiovascular disease that have been licensed to Dade-Behring and Astra. Zeneca.

Ridker et al NEJM 2008 Justification for the Use of statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin To investigate whether rosuvastatin 20 mg compared to placebo would decrease the rate of first major cardiovascular events among apparently healthy men and women with LDL < 130 mg/d. L (3. 36 mmol/L) who are nonetheless at increased vascular risk on the basis of an enhanced inflammatory response, as determined by hs. CRP > 2 mg/L. To enroll large numbers of women and individuals of Black or Hispanic ethnicity, groups for whom little data on primary prevention with statin therapy exists.

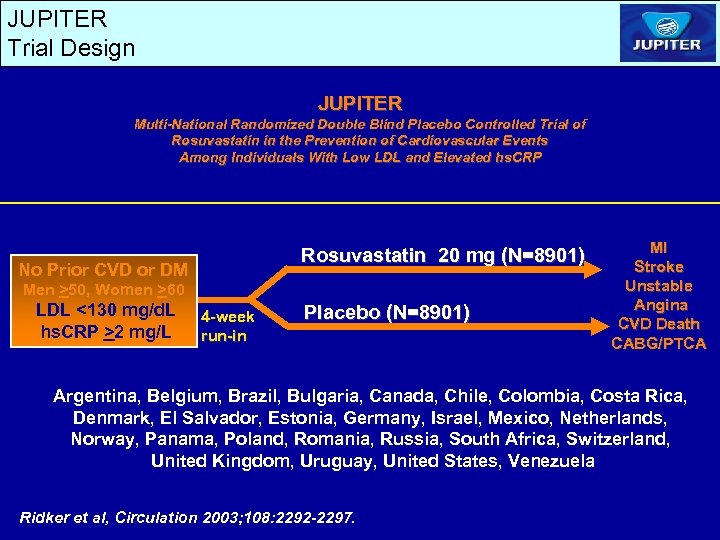

JUPITER Trial Design JUPITER Multi-National Randomized Double Blind Placebo Controlled Trial of Rosuvastatin in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Events Among Individuals With Low LDL and Elevated hs. CRP Rosuvastatin 20 mg (N=8901) No Prior CVD or DM Men >50, Women >60 LDL <130 mg/d. L hs. CRP >2 mg/L 4 -week run-in Placebo (N=8901) MI Stroke Unstable Angina CVD Death CABG/PTCA Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, El Salvador, Estonia, Germany, Israel, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Panama, Poland, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Uruguay, United States, Venezuela Ridker et al, Circulation 2003; 108: 2292 -2297.

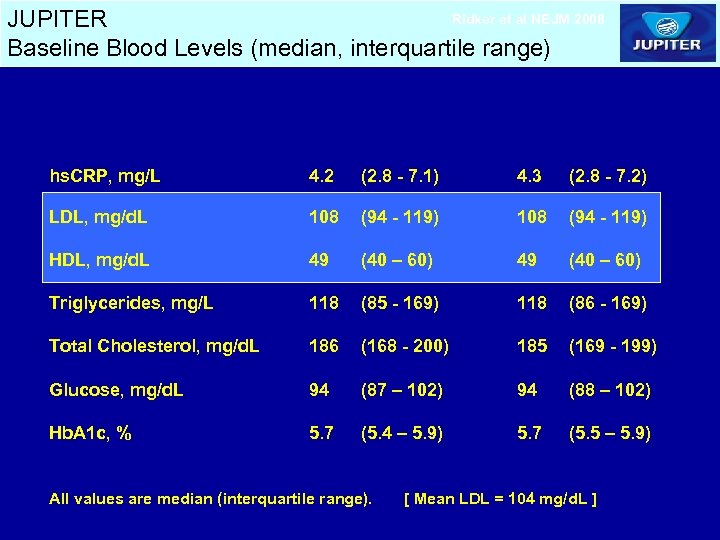

Ridker et al NEJM 2008 JUPITER Baseline Blood Levels (median, interquartile range) Rosuvastatin (N = 8901) Placebo (n = 8901) hs. CRP, mg/L 4. 2 (2. 8 - 7. 1) 4. 3 (2. 8 - 7. 2) LDL, mg/d. L 108 (94 - 119) HDL, mg/d. L 49 (40 – 60) Triglycerides, mg/L 118 (85 - 169) 118 (86 - 169) Total Cholesterol, mg/d. L 186 (168 - 200) 185 (169 - 199) Glucose, mg/d. L 94 (87 – 102) 94 (88 – 102) Hb. A 1 c, % 5. 7 (5. 4 – 5. 9) 5. 7 (5. 5 – 5. 9) All values are median (interquartile range). [ Mean LDL = 104 mg/d. L ]

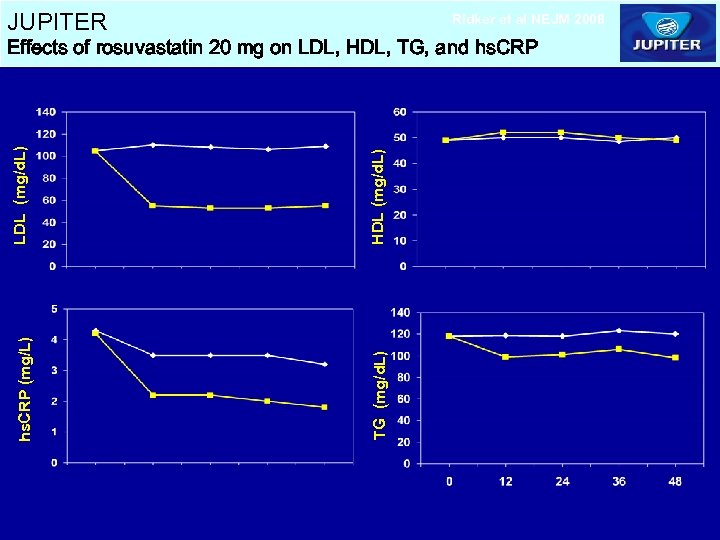

JUPITER Ridker et al NEJM 2008 hs. CRP decrease 37 percent at 12 months 0 12 24 Months 36 HDL (mg/d. L) LDL decrease 50 percent at 12 months HDL increase 4 percent at 12 months TG (mg/d. L) hs. CRP (mg/L) LDL (mg/d. L) Effects of rosuvastatin 20 mg on LDL, HDL, TG, and hs. CRP TG decrease 17 percent at 12 months 48 Months

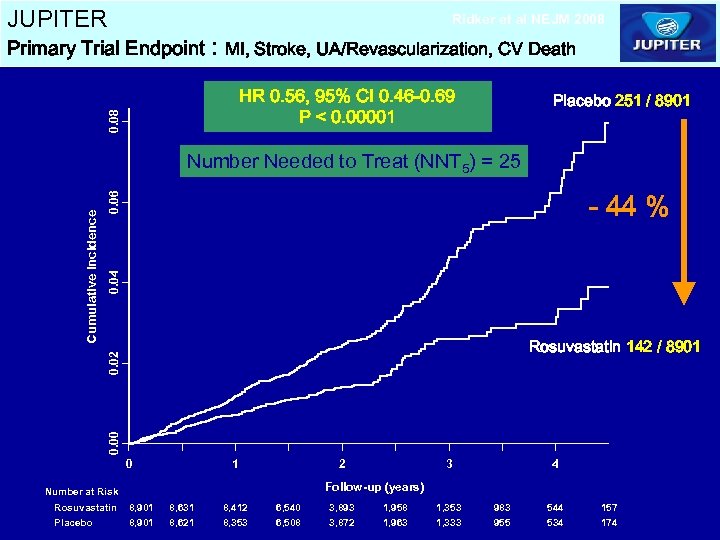

JUPITER Ridker et al NEJM 2008 Primary Trial Endpoint : MI, Stroke, UA/Revascularization, CV Death 0. 08 HR 0. 56, 95% CI 0. 46 -0. 69 P < 0. 00001 Placebo 251 / 8901 0. 04 0. 06 - 44 % Rosuvastatin 142 / 8901 0. 00 0. 02 Cumulative Incidence Number Needed to Treat (NNT 5) = 25 0 1 2 4 Follow-up (years) Number at Risk Rosuvastatin Placebo 3 8, 901 8, 631 8, 621 8, 412 8, 353 6, 540 6, 508 3, 893 3, 872 1, 958 1, 963 1, 353 1, 333 983 955 544 534 157 174

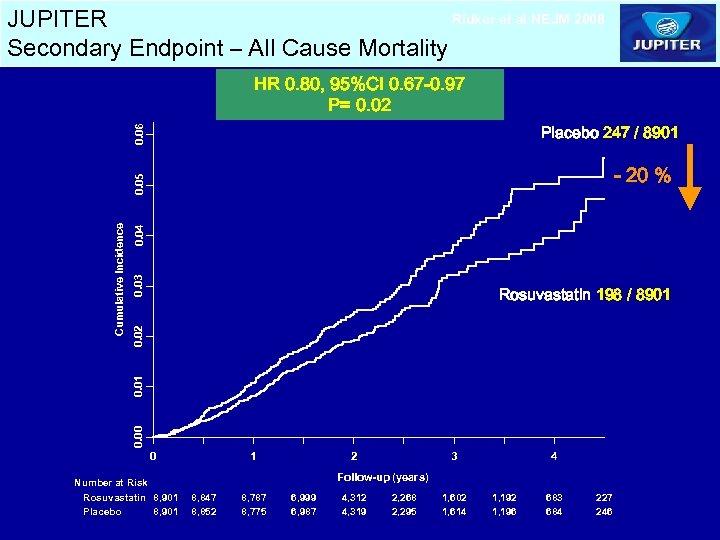

Ridker et al NEJM 2008 JUPITER Secondary Endpoint – All Cause Mortality HR 0. 80, 95%CI 0. 67 -0. 97 P= 0. 02 0. 06 Placebo 247 / 8901 0. 04 0. 03 0. 02 Rosuvastatin 198 / 8901 0. 00 0. 01 Cumulative Incidence 0. 05 - 20 % 0 Number at Risk Rosuvastatin 8, 901 Placebo 8, 901 1 2 3 4 Follow-up (years) 8, 847 8, 852 8, 787 8, 775 6, 999 6, 987 4, 312 4, 319 2, 268 2, 295 1, 602 1, 614 1, 192 1, 196 683 684 227 246

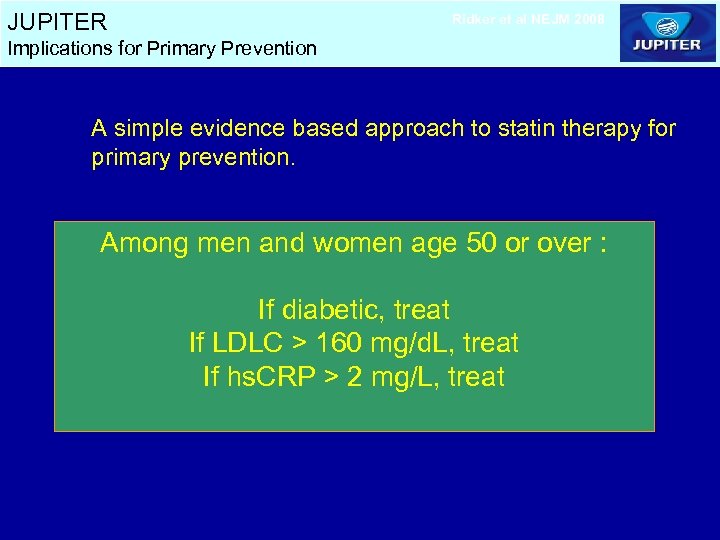

JUPITER Ridker et al NEJM 2008 Implications for Primary Prevention A simple evidence based approach to statin therapy for primary prevention. Among men and women age 50 or over : If diabetic, treat If LDLC > 160 mg/d. L, treat If hs. CRP > 2 mg/L, treat

AHA / CDC Scientific Statement Markers of Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease: Applications to Clinical and Public Health Practice Circulation January 28, 2003 “Measurement of hs-CRP is an independent marker of risk and may be used at the discretion of the physician as part of global coronary risk assessment in adults without known cardiovascular disease. Weight of evidence favors use particularly among those judged at intermediate risk by global risk assessment”.

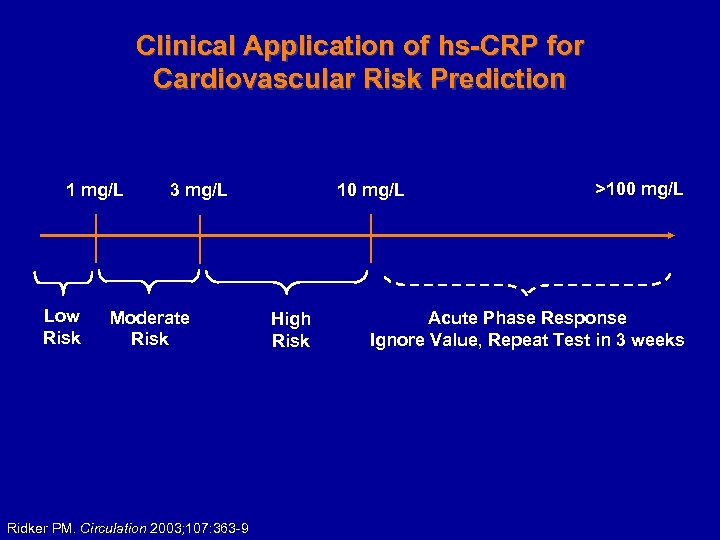

Clinical Application of hs-CRP for Cardiovascular Risk Prediction 1 mg/L Low Risk 3 mg/L Moderate Risk Ridker PM. Circulation 2003; 107: 363 -9 10 mg/L High Risk >100 mg/L Acute Phase Response Ignore Value, Repeat Test in 3 weeks

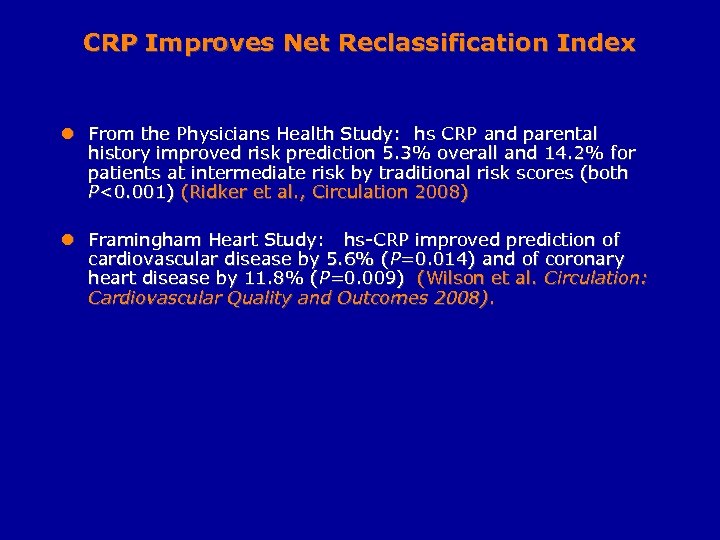

CRP Improves Net Reclassification Index l From the Physicians Health Study: hs CRP and parental history improved risk prediction 5. 3% overall and 14. 2% for patients at intermediate risk by traditional risk scores (both P<0. 001) (Ridker et al. , Circulation 2008) l Framingham Heart Study: hs-CRP improved prediction of cardiovascular disease by 5. 6% (P=0. 014) and of coronary heart disease by 11. 8% (P=0. 009) (Wilson et al. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 2008).

Homocysteine l Intermediary amino acid formed by the conversion of methionine to cysteine l Moderate hyperhomocysteinemia occurs in 57% of the population l Recognized as an independent risk factor for the development of atherosclerotic vascular disease and venous thrombosis l Can result from genetic defects, drugs, vitamin deficiencies, or smoking

Homocysteine l Homocysteine implicated directly in vascular injury including: —Intimal thickening —Disruption of elastic lamina —Smooth muscle hypertrophy —Platelet aggregation l Vascular injury induced by leukocyte recruitment, foam cell formation, and inhibition of NO synthesis

Homocysteine l Elevated levels appear to be an independent risk factor, though less important than the classic CV risk factors l Screening recommended in patients with premature CV disease (or unexplained DVT) and absence of other risk factors l Treatment includes supplementation with folate, B 6 and B 12

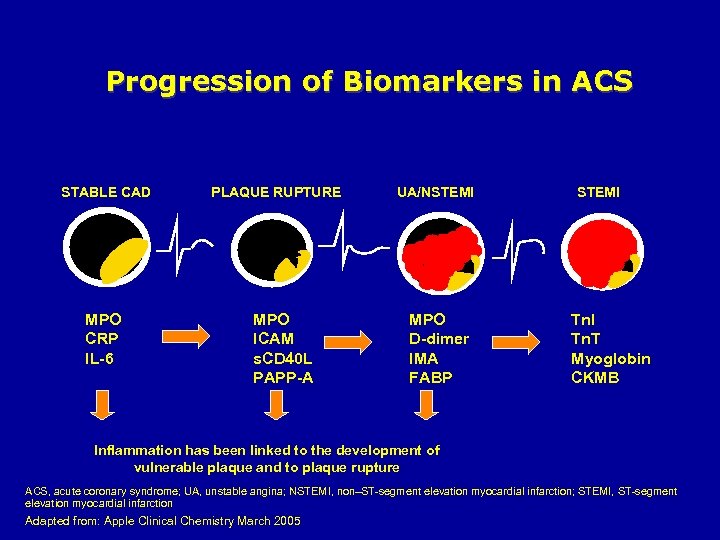

Current Biomarkers for ACS l Biomarker assessment of high risk patients may include: — Inflammatory cytokines — Cellular adhesion molecules — Acute-phase reactants — Plaque destabilization and rupture biomarkers — Biomarkers of ischemia — Biomarkers of myocardial stretch (BNP) — Biomarkers of myocardial necrosis (Troponin, CK-MB, Myoglobin) Apple Clinical Chemistry March 2005

Progression of Biomarkers in ACS STABLE CAD MPO CRP IL-6 PLAQUE RUPTURE MPO ICAM s. CD 40 L PAPP-A UA/NSTEMI MPO D-dimer IMA FABP STEMI Tn. T Myoglobin CKMB Inflammation has been linked to the development of vulnerable plaque and to plaque rupture ACS, acute coronary syndrome; UA, unstable angina; NSTEMI, non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction Adapted from: Apple Clinical Chemistry March 2005

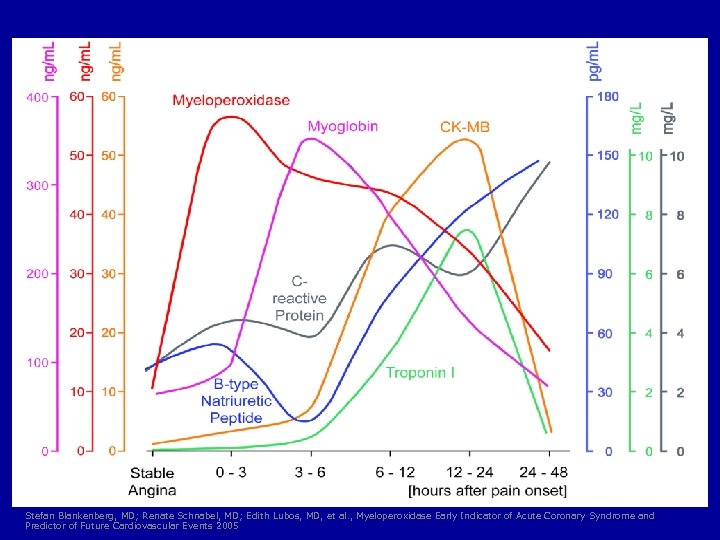

Stefan Blankenberg, MD; Renate Schnabel, MD; Edith Lubos, MD, et al. , Myeloperoxidase Early Indicator of Acute Coronary Syndrome and Predictor of Future Cardiovascular Events 2005

History: Troponin l Troponin I first described as a biomarker specific for AMI in 19871; Troponin T in 19892 l Now the biochemical “gold standard” for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction via consensus of ESC/ACC 1 2 Am Heart J 113: 1333 -44 J Mol Cell Cardiol 21: 1349 -53

Troponins l Elevated serum levels are an independent predictor of prognosis, morbidity and mortality l Meta-analysis of 21 studies involving ~20, 000 patients with ACS revealed that those with elevated serum troponin had 3 x risk of cardiac death or reinfarction at 30 days 1 1 Am J Heart (140): 917

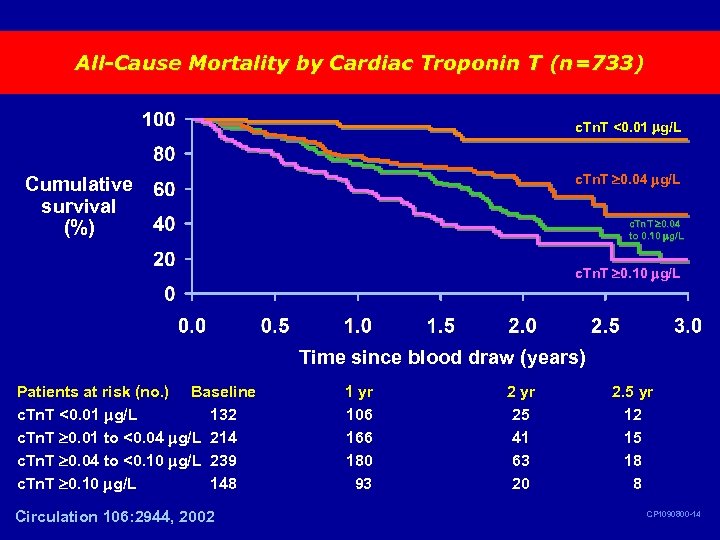

All-Cause Mortality by Cardiac Troponin T (n=733) c. Tn. T <0. 01 g/L c. Tn. T 0. 04 g/L Cumulative survival (%) c. Tn. T 0. 04 to 0. 10 g/L c. Tn. T 0. 10 g/L Time since blood draw (years) Patients at risk (no. ) Baseline c. Tn. T <0. 01 g/L 132 c. Tn. T 0. 01 to <0. 04 g/L 214 c. Tn. T 0. 04 to <0. 10 g/L 239 c. Tn. T 0. 10 g/L 148 Circulation 106: 2944, 2002 1 yr 106 166 180 93 2 yr 25 41 63 20 2. 5 yr 12 15 18 8 CP 1090800 -14

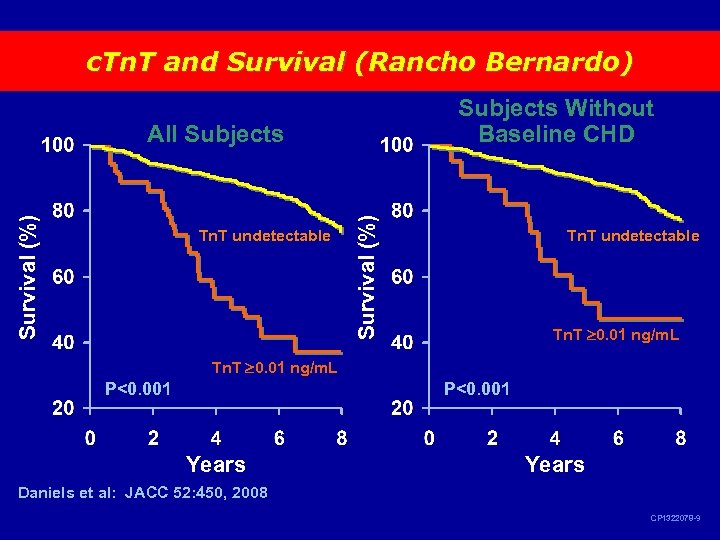

c. Tn. T and Survival (Rancho Bernardo) Subjects Without Baseline CHD Tn. T undetectable Survival (%) All Subjects Tn. T undetectable Tn. T 0. 01 ng/m. L P<0. 001 Years Daniels et al: JACC 52: 450, 2008 CP 1322078 -9

BNP l BNP has also shown utility as a prognostic marker in acute coronary syndrome l It is associated with increased risk of death at 10 months as concentration at 40 hours postinfarct increased l Also associated with increased risk for new or recurrent MI

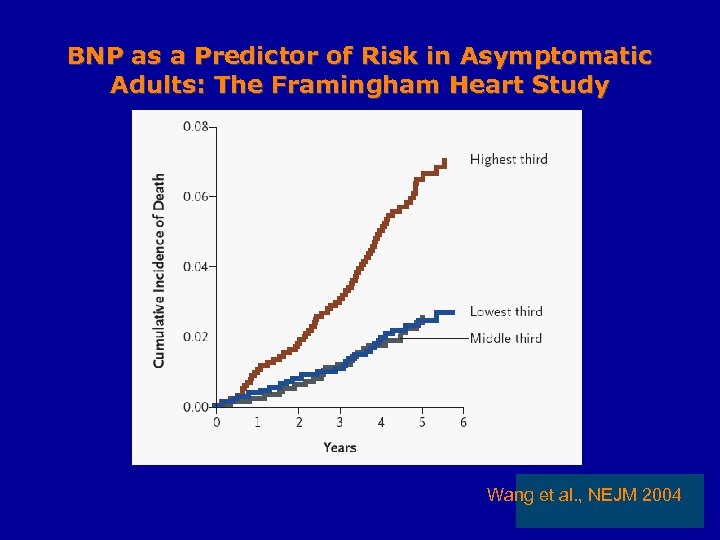

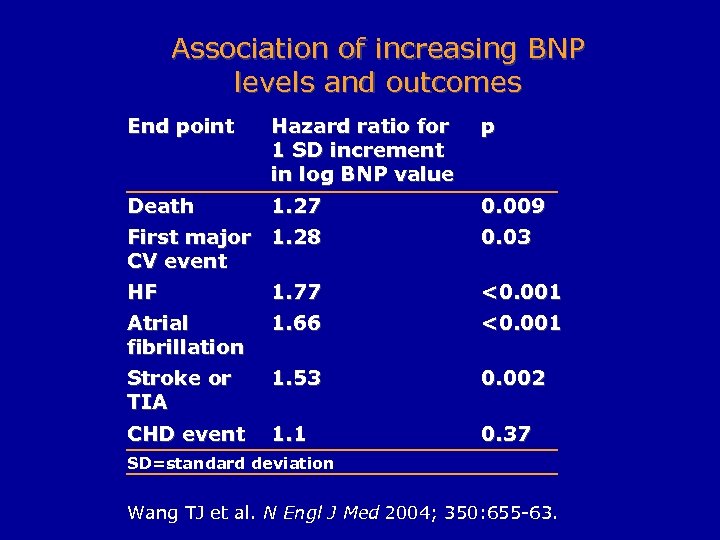

BNP as a Predictor of Risk in Asymptomatic Adults: The Framingham Heart Study Wang et al. , NEJM 2004

Association of increasing BNP levels and outcomes End point Hazard ratio for 1 SD increment in log BNP value p Death 1. 27 0. 009 First major 1. 28 CV event 0. 03 HF 1. 77 <0. 001 Atrial fibrillation 1. 66 <0. 001 Stroke or TIA 1. 53 0. 002 CHD event 1. 1 0. 37 SD=standard deviation Wang TJ et al. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 655 -63.

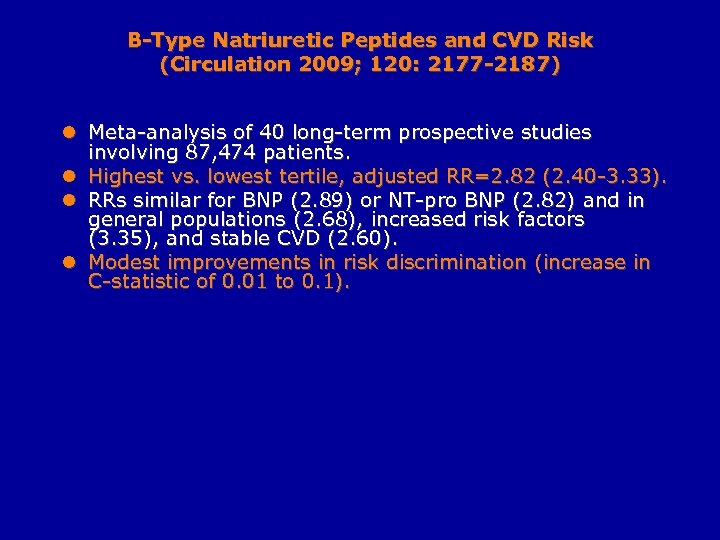

B-Type Natriuretic Peptides and CVD Risk (Circulation 2009; 120: 2177 -2187) l Meta-analysis of 40 long-term prospective studies involving 87, 474 patients. l Highest vs. lowest tertile, adjusted RR=2. 82 (2. 40 -3. 33). l RRs similar for BNP (2. 89) or NT-pro BNP (2. 82) and in general populations (2. 68), increased risk factors (3. 35), and stable CVD (2. 60). l Modest improvements in risk discrimination (increase in C-statistic of 0. 01 to 0. 1).

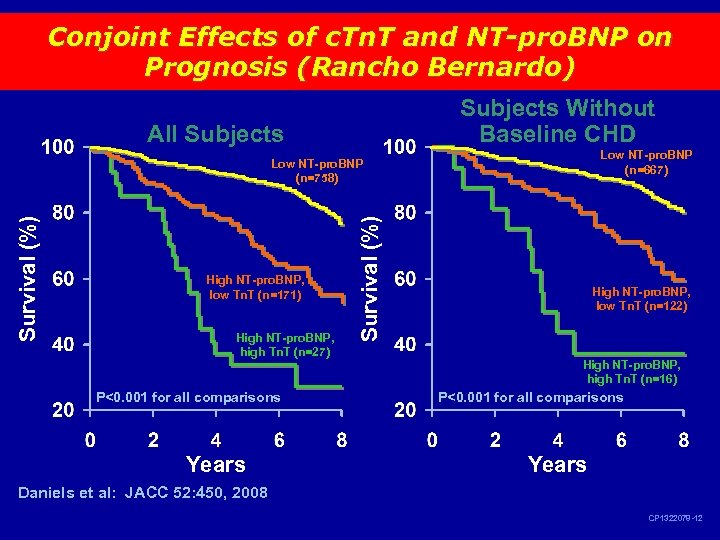

Conjoint Effects of c. Tn. T and NT-pro. BNP on Prognosis (Rancho Bernardo) Subjects Without Baseline CHD All Subjects Low NT-pro. BNP (n=667) High NT-pro. BNP, low Tn. T (n=171) High NT-pro. BNP, high Tn. T (n=27) P<0. 001 for all comparisons Years Survival (%) Low NT-pro. BNP (n=758) High NT-pro. BNP, low Tn. T (n=122) High NT-pro. BNP, high Tn. T (n=16) P<0. 001 for all comparisons Years Daniels et al: JACC 52: 450, 2008 CP 1322078 -12

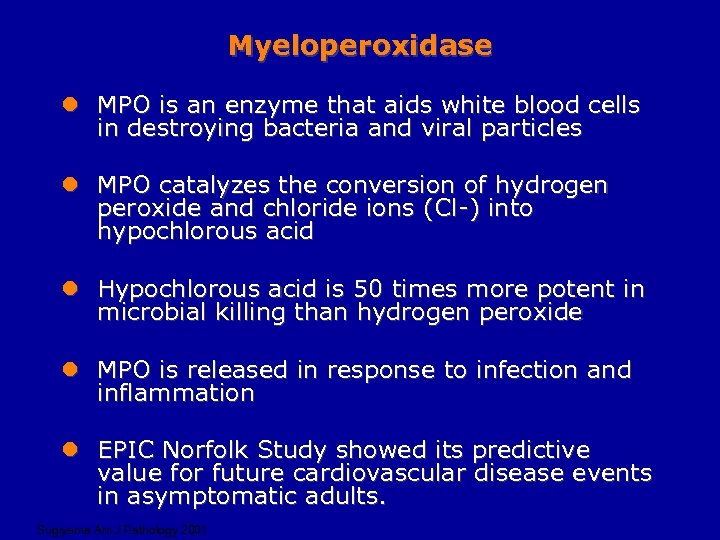

Myeloperoxidase l MPO is an enzyme that aids white blood cells in destroying bacteria and viral particles l MPO catalyzes the conversion of hydrogen peroxide and chloride ions (Cl-) into hypochlorous acid l Hypochlorous acid is 50 times more potent in microbial killing than hydrogen peroxide l MPO is released in response to infection and inflammation l EPIC Norfolk Study showed its predictive value for future cardiovascular disease events in asymptomatic adults. Sugiyama Am J Pathology 2001

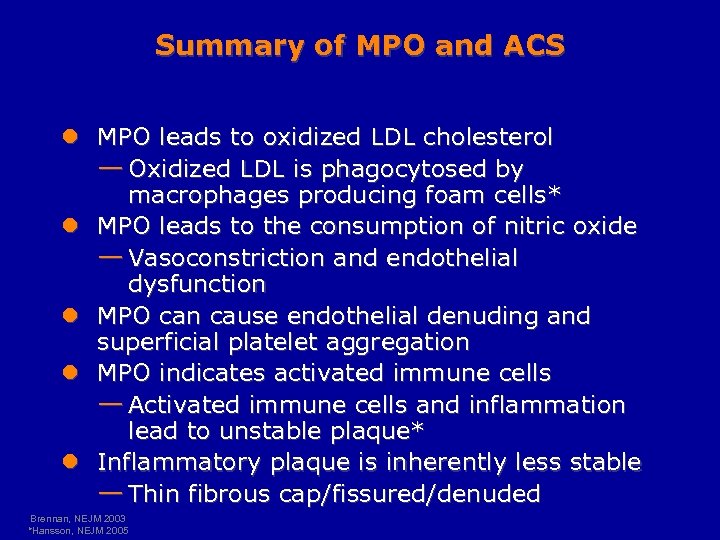

Summary of MPO and ACS l MPO leads to oxidized LDL cholesterol — Oxidized LDL is phagocytosed by macrophages producing foam cells* l MPO leads to the consumption of nitric oxide — Vasoconstriction and endothelial dysfunction l MPO can cause endothelial denuding and superficial platelet aggregation l MPO indicates activated immune cells — Activated immune cells and inflammation lead to unstable plaque* l Inflammatory plaque is inherently less stable — Thin fibrous cap/fissured/denuded Brennan, NEJM 2003 *Hansson, NEJM 2005

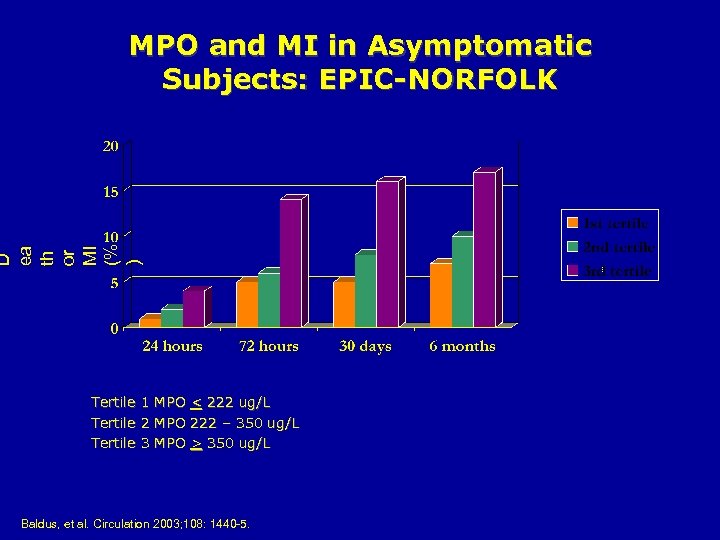

D ea th or MI (% ) MPO and MI in Asymptomatic Subjects: EPIC-NORFOLK Tertile 1 2 3 MPO MPO < 222 ug/L 222 – 350 ug/L > 350 ug/L Baldus, et al. Circulation 2003; 108: 1440 -5.

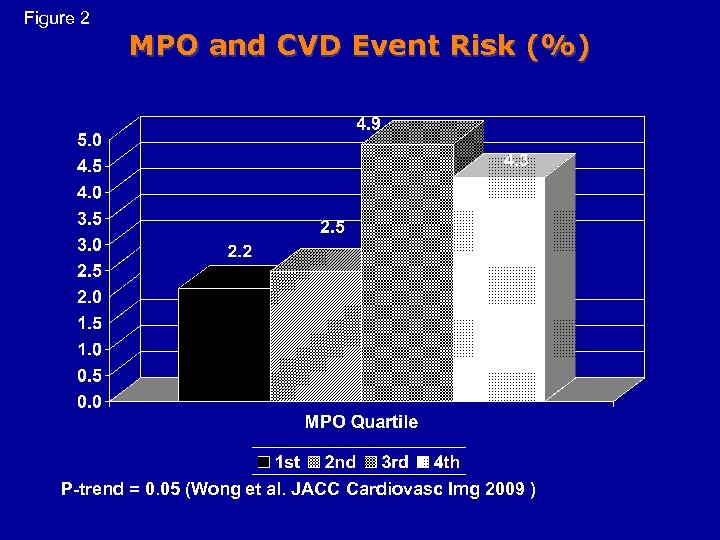

Figure 2 MPO and CVD Event Risk (%) P-trend = 0. 05 (Wong et al. JACC Cardiovasc Img 2009 )

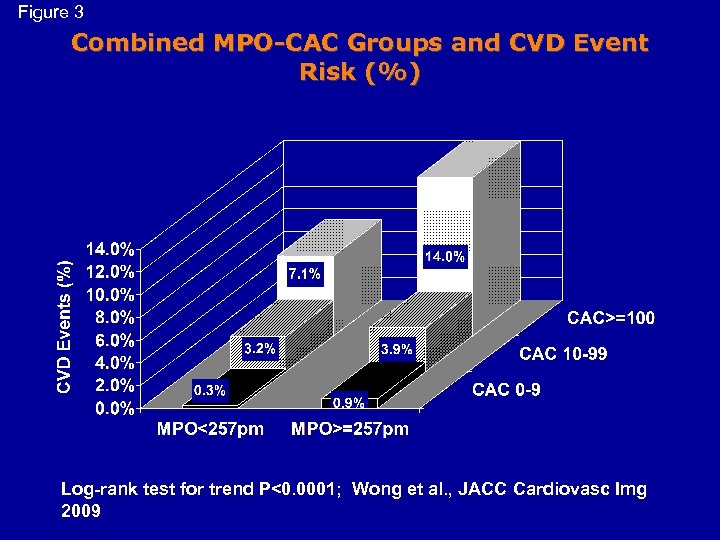

Figure 3 Combined MPO-CAC Groups and CVD Event Risk (%) Log-rank test for trend P<0. 0001; Wong et al. , JACC Cardiovasc Img 2009

The Future of Cardiac Biomarkers l Many experts are advocating the move towards a multimarker strategy for the purposes of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment design l As the pathophysiology of ACS is heterogeneous, so must be the diagnostic strategies

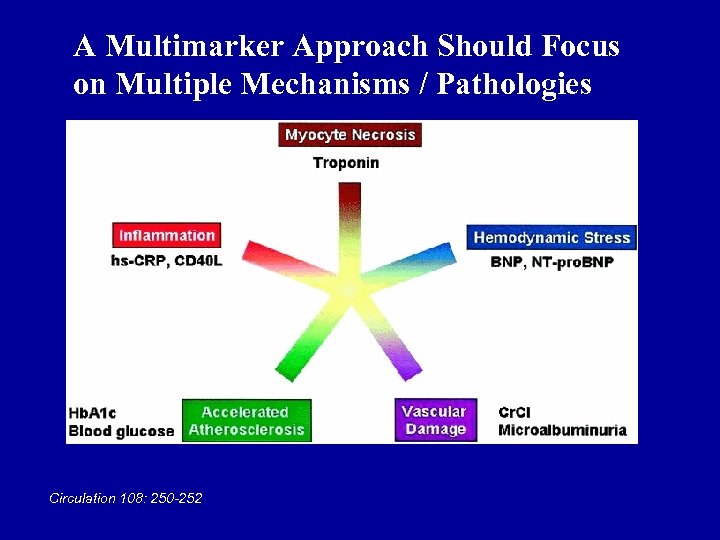

A Multimarker Approach Should Focus on Multiple Mechanisms / Pathologies Circulation 108: 250 -252

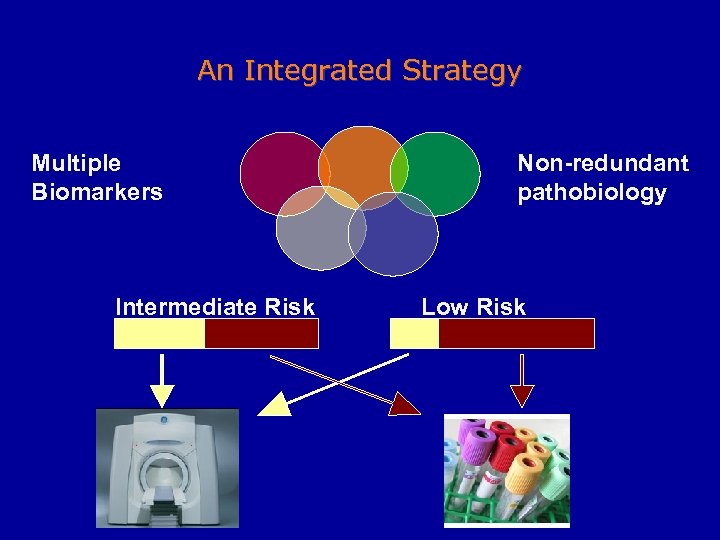

An Integrated Strategy Multiple Biomarkers Intermediate Risk Non-redundant pathobiology Low Risk

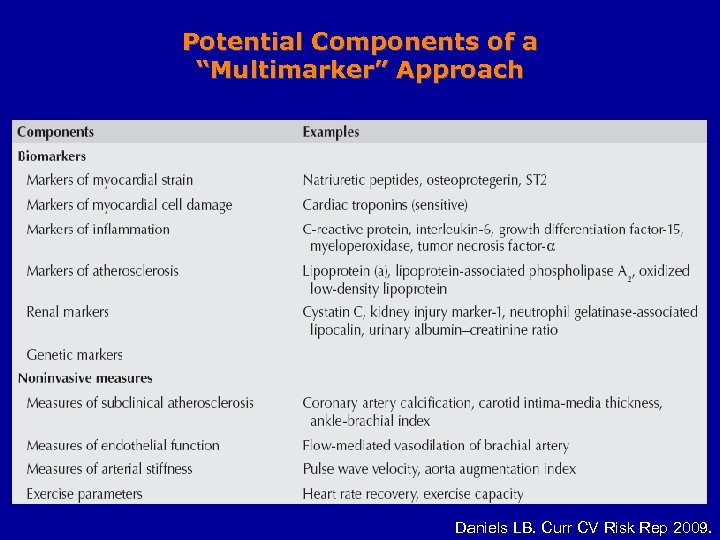

Potential Components of a “Multimarker” Approach Daniels LB. Curr CV Risk Rep 2009.

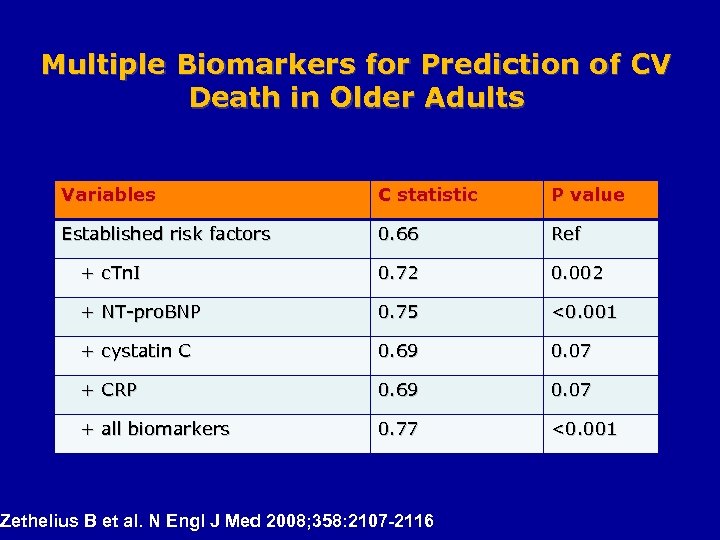

Multiple Biomarkers for Prediction of CV Death in Older Adults Variables C statistic P value Established risk factors 0. 66 Ref + c. Tn. I 0. 72 0. 002 + NT-pro. BNP 0. 75 <0. 001 + cystatin C 0. 69 0. 07 + CRP 0. 69 0. 07 + all biomarkers 0. 77 <0. 001 Zethelius B et al. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2107 -2116

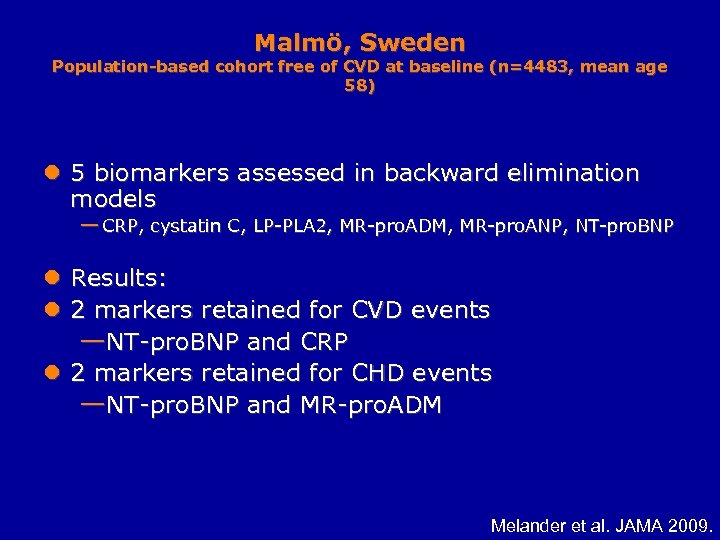

Malmö, Sweden Population-based cohort free of CVD at baseline (n=4483, mean age 58) l 5 biomarkers assessed in backward elimination models — CRP, cystatin C, LP-PLA 2, MR-pro. ADM, MR-pro. ANP, NT-pro. BNP l Results: l 2 markers retained for CVD events —NT-pro. BNP and CRP l 2 markers retained for CHD events —NT-pro. BNP and MR-pro. ADM Melander et al. JAMA 2009.

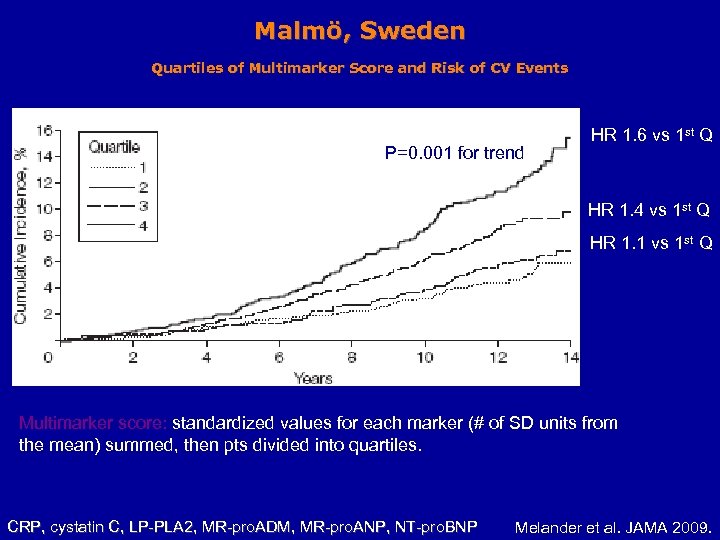

Malmö, Sweden Quartiles of Multimarker Score and Risk of CV Events P=0. 001 for trend HR 1. 6 vs 1 st Q HR 1. 4 vs 1 st Q HR 1. 1 vs 1 st Q Multimarker score: standardized values for each marker (# of SD units from the mean) summed, then pts divided into quartiles. CRP, cystatin C, LP-PLA 2, MR-pro. ADM, MR-pro. ANP, NT-pro. BNP Melander et al. JAMA 2009.

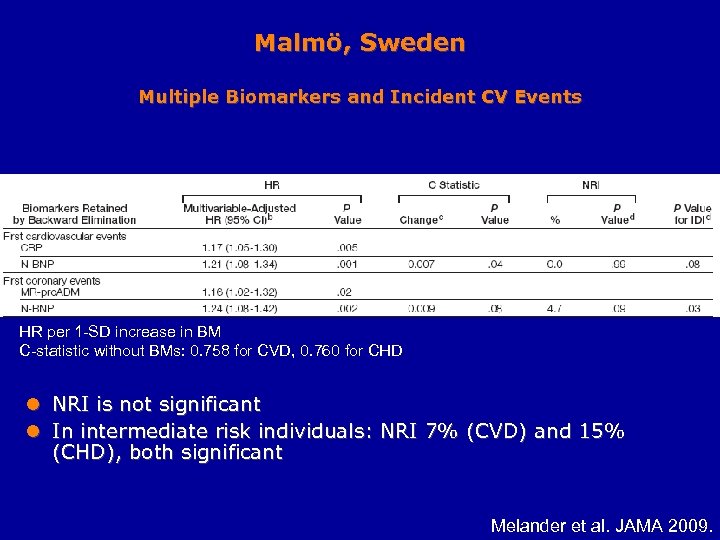

Malmö, Sweden Multiple Biomarkers and Incident CV Events HR per 1 -SD increase in BM C-statistic without BMs: 0. 758 for CVD, 0. 760 for CHD l NRI is not significant l In intermediate risk individuals: NRI 7% (CVD) and 15% (CHD), both significant Melander et al. JAMA 2009.

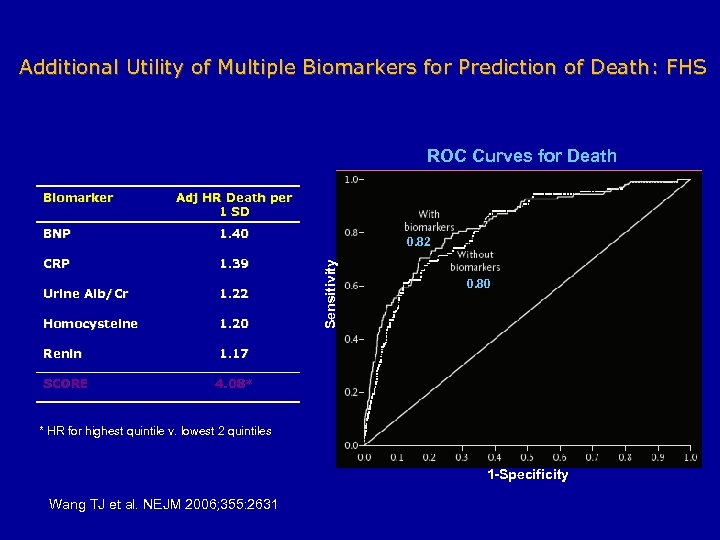

Additional Utility of Multiple Biomarkers for Prediction of Death: FHS ROC Curves for Death Biomarker Adj HR Death per 1 SD 1. 40 CRP 1. 39 Urine Alb/Cr 1. 22 Homocysteine 1. 20 Renin 1. 17 SCORE 4. 08* 0. 82 Sensitivity BNP 0. 80 * HR for highest quintile v. lowest 2 quintiles 1 -Specificity Wang TJ et al. NEJM 2006; 355: 2631

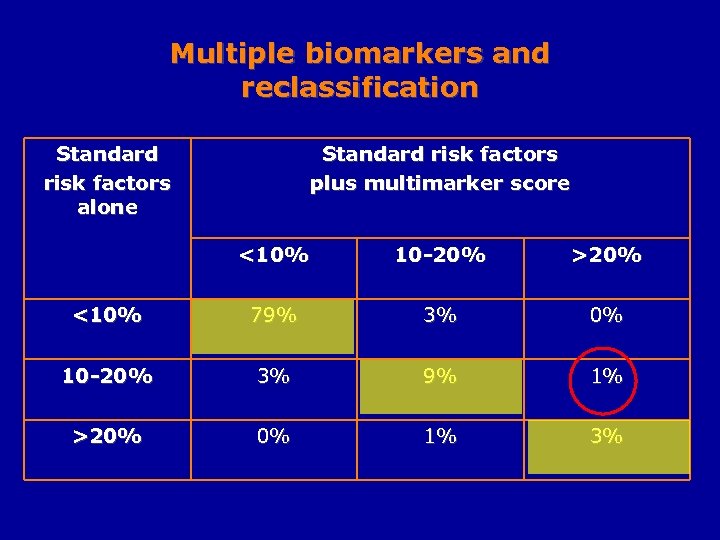

Multiple biomarkers and reclassification Standard risk factors alone Standard risk factors plus multimarker score <10% 10 -20% >20% <10% 79% 3% 0% 10 -20% 3% 9% 1% >20% 0% 1% 3%

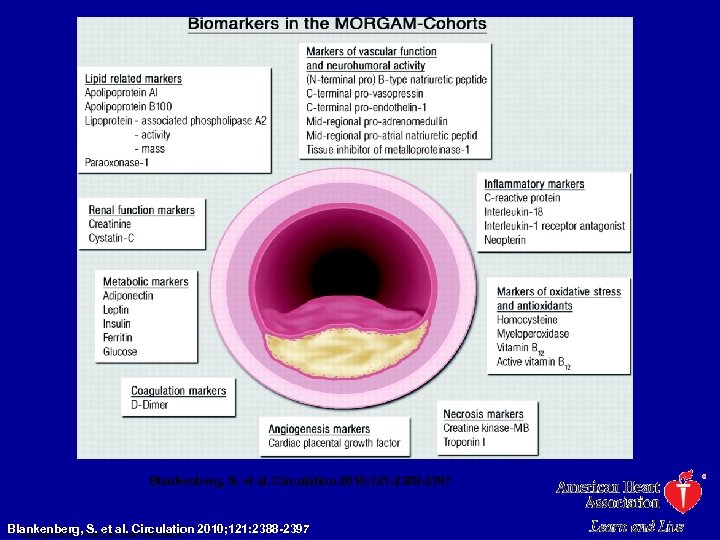

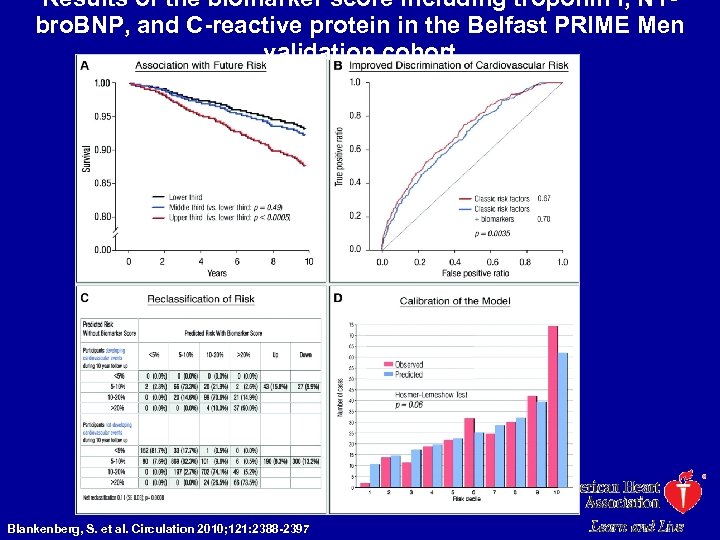

Blankenberg, S. et al. Circulation 2010; 121: 2388 -2397 Blankenberg, Americanal. Circulation 2010; 121: 2388 -2397 Copyright © 2010 S. et Heart Association

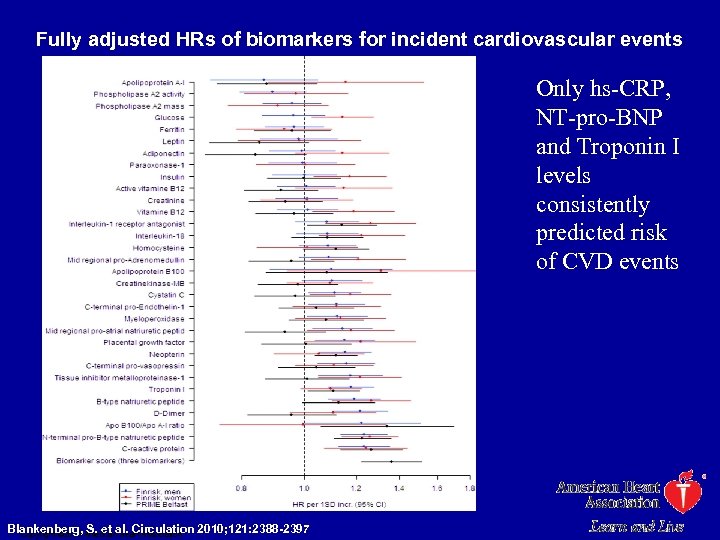

Fully adjusted HRs of biomarkers for incident cardiovascular events Only hs-CRP, NT-pro-BNP and Troponin I levels consistently predicted risk of CVD events Blankenberg, Americanal. Circulation 2010; 121: 2388 -2397 Copyright © 2010 S. et Heart Association

Results of the biomarker score including troponin I, NTbro. BNP, and C-reactive protein in the Belfast PRIME Men validation cohort Blankenberg, S. et al. Circulation 2010; 121: 2388 -2397

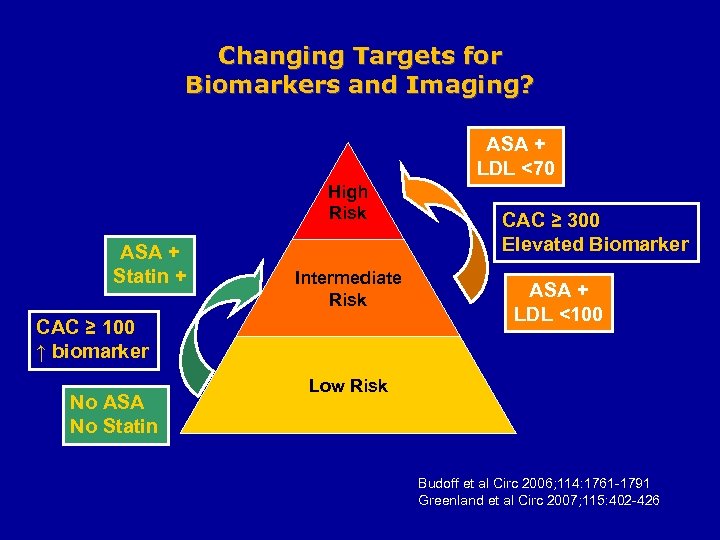

Changing Targets for Biomarkers and Imaging? ASA + LDL <70 High Risk ASA + Statin + Intermediate Risk CAC ≥ 100 ↑ biomarker No ASA No Statin CAC ≥ 300 Elevated Biomarker ASA + LDL <100 Low Risk Budoff et al Circ 2006; 114: 1761 -1791 Greenland et al Circ 2007; 115: 402 -426

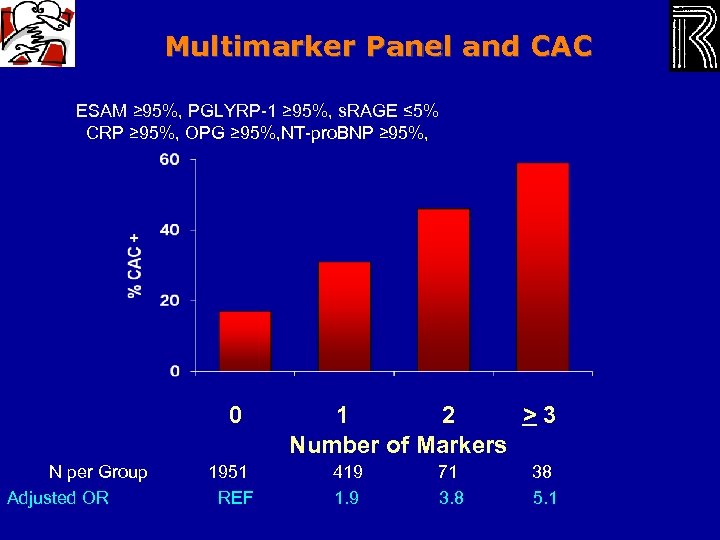

Multimarker Panel and CAC ESAM ≥ 95%, PGLYRP-1 ≥ 95%, s. RAGE ≤ 5% CRP ≥ 95%, OPG ≥ 95%, NT-pro. BNP ≥ 95%, 0 N per Group Adjusted OR 1 2 >3 Number of Markers 1951 419 71 38 REF 1. 9 3. 8 5. 1 De. Lemos, AHA Epi and Prevention Conf. , 2010

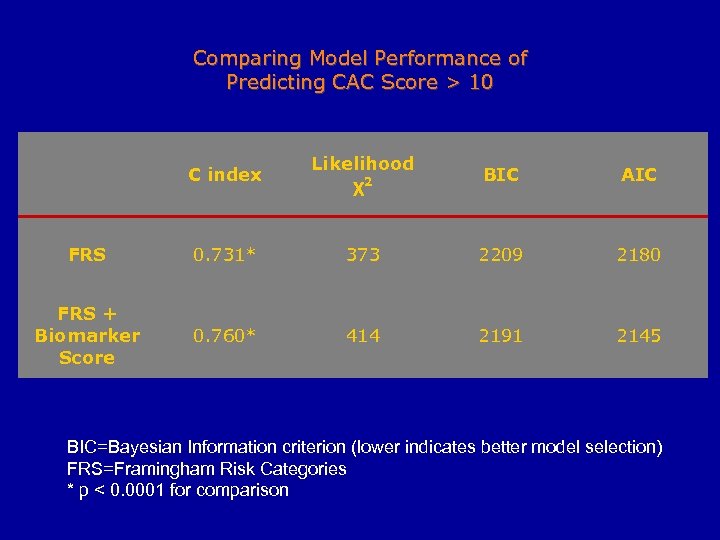

Comparing Model Performance of Predicting CAC Score > 10 C index Likelihood χ2 BIC AIC FRS 0. 731* 373 2209 2180 FRS + Biomarker Score 0. 760* 414 2191 2145 BIC=Bayesian Information criterion (lower indicates better model selection) FRS=Framingham Risk Categories * p < 0. 0001 for comparison De. Lemos, AHA Epi and Prevention Conf. , 2010

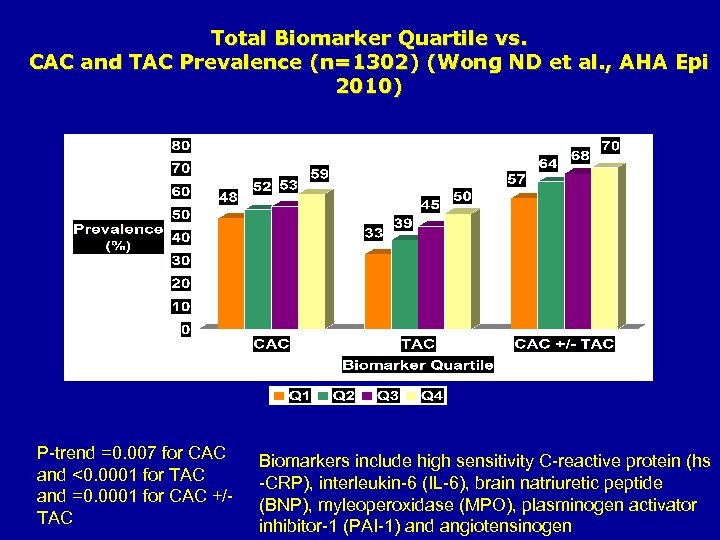

Total Biomarker Quartile vs. CAC and TAC Prevalence (n=1302) (Wong ND et al. , AHA Epi 2010) P-trend =0. 007 for CAC and <0. 0001 for TAC and =0. 0001 for CAC +/TAC Biomarkers include high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs -CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), myleoperoxidase (MPO), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and angiotensinogen

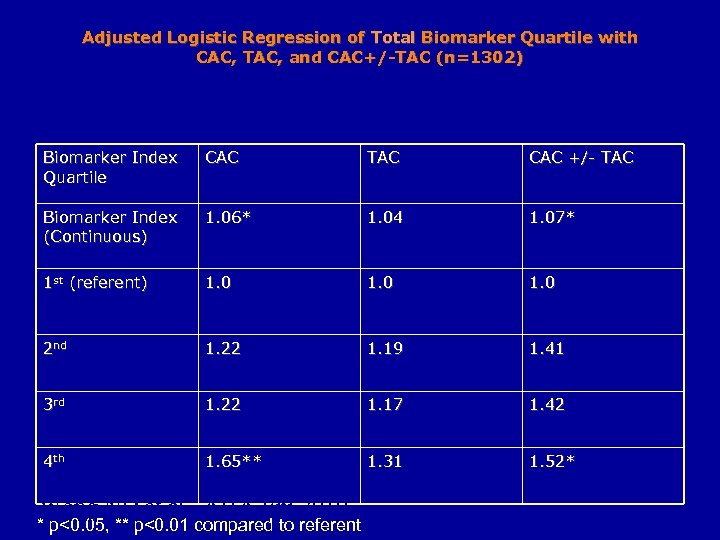

Adjusted Logistic Regression of Total Biomarker Quartile with CAC, TAC, and CAC+/-TAC (n=1302) Biomarker Index Quartile CAC TAC CAC +/- TAC Biomarker Index (Continuous) 1. 06* 1. 04 1. 07* 1 st (referent) 1. 0 2 nd 1. 22 1. 19 1. 41 3 rd 1. 22 1. 17 1. 42 4 th 1. 65** 1. 31 1. 52* Wong ND et al. , AHA Epi 2010 * p<0. 05, ** p<0. 01 compared to referent

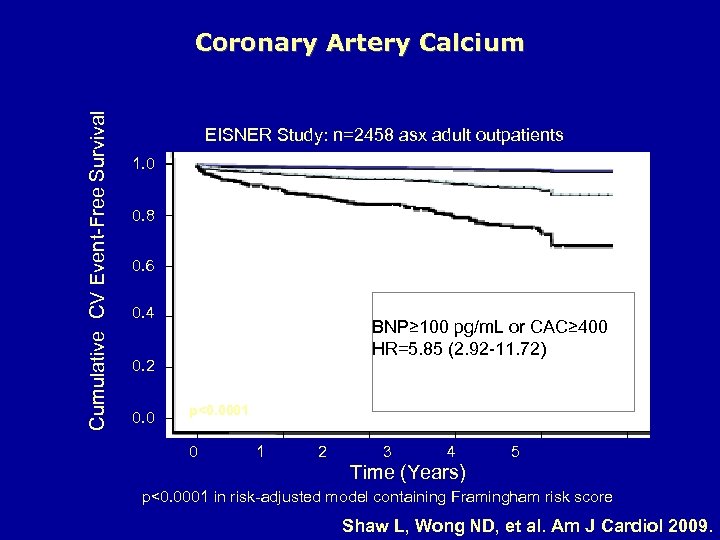

Cumulative CV Event-Free Survival Coronary Artery Calcium EISNER Study: n=2458 asx adult outpatients 1. 0 0. 8 0. 6 BNP<100 pg/m. L and CAC<400 BNP≥ 100 pg/m. L or CAC≥ 400 HR=5. 85 (2. 92 -11. 72) 0. 4 0. 2 0. 0 BNP≥ 100 pg/m. L and CAC≥ 400 HR=13. 11 (3. 97 -43. 34) p<0. 0001 0 1 2 3 4 5 Time (Years) p<0. 0001 in risk-adjusted model containing Framingham risk score Shaw L, Wong ND, et al. Am J Cardiol 2009.

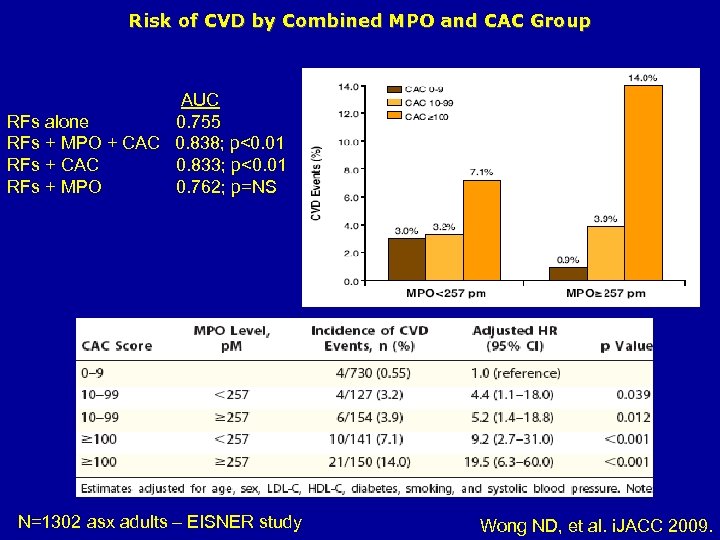

Risk of CVD by Combined MPO and CAC Group AUC RFs alone 0. 755 RFs + MPO + CAC 0. 838; p<0. 01 RFs + CAC 0. 833; p<0. 01 RFs + MPO 0. 762; p=NS N=1302 asx adults – EISNER study Wong ND, et al. i. JACC 2009.

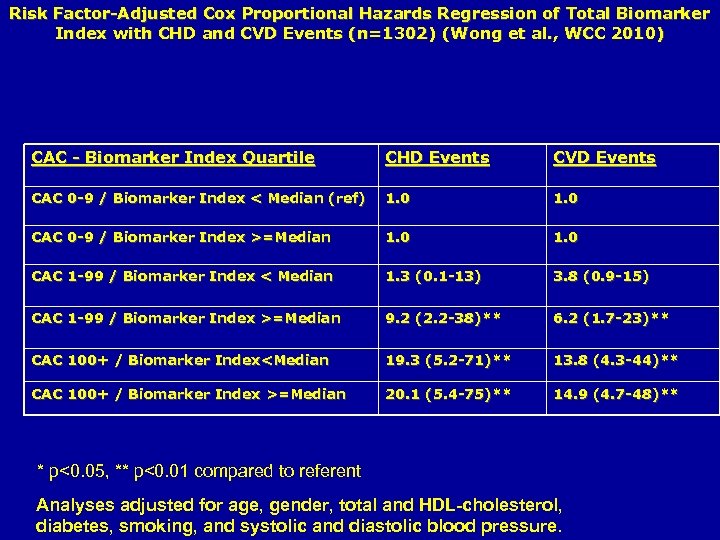

Risk Factor-Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Regression of Total Biomarker Index with CHD and CVD Events (n=1302) (Wong et al. , WCC 2010) CAC - Biomarker Index Quartile CHD Events CVD Events CAC 0 -9 / Biomarker Index < Median (ref) 1. 0 CAC 0 -9 / Biomarker Index >=Median 1. 0 CAC 1 -99 / Biomarker Index < Median 1. 3 (0. 1 -13) 3. 8 (0. 9 -15) CAC 1 -99 / Biomarker Index >=Median 9. 2 (2. 2 -38)** 6. 2 (1. 7 -23)** CAC 100+ / Biomarker Index<Median 19. 3 (5. 2 -71)** 13. 8 (4. 3 -44)** CAC 100+ / Biomarker Index >=Median 20. 1 (5. 4 -75)** 14. 9 (4. 7 -48)** * p<0. 05, ** p<0. 01 compared to referent Analyses adjusted for age, gender, total and HDL-cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Conclusions l Standard risk factors alone or in combination do not predict global risk well enough Ø Too many events in too many lower risk individuals Ø Modest screening performance l Measurement of certain biomarkers such as hs-CRP may be useful in conjunction with global risk assessment to improve risk classification. l Insufficient data at the present time to recommend novel biomarkers to screen the population at large, but selected intermediate risk populations may be appropriate.

Conclusions (cont. ) l Individual biomarkers do not markedly improve risk prediction —Markers of existing disease most promising (including imaging tools) l Combining individual markers that reflect distinct biological pathways is a promising strategy, with several caveats —Combining multiple mediocre markers will not work —Not close to ready for clinical application l Cost-effectiveness and outcome studies needed

ff1c7be991804d6ba4a86867b8e14b72.ppt