6154be0929e42286164283a1c160778a.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 43

New Jersey Department of Transportation, In. House Lecture Series, Trenton, September 24, 2008 Transportation and Oil Prices: From Modal Shift to Supply Chain Propagation Jean-Paul Rodrigue Associate Professor Dept. of Global Studies & Geography Hofstra University New York, USA

New Jersey Department of Transportation, In. House Lecture Series, Trenton, September 24, 2008 Transportation and Oil Prices: From Modal Shift to Supply Chain Propagation Jean-Paul Rodrigue Associate Professor Dept. of Global Studies & Geography Hofstra University New York, USA

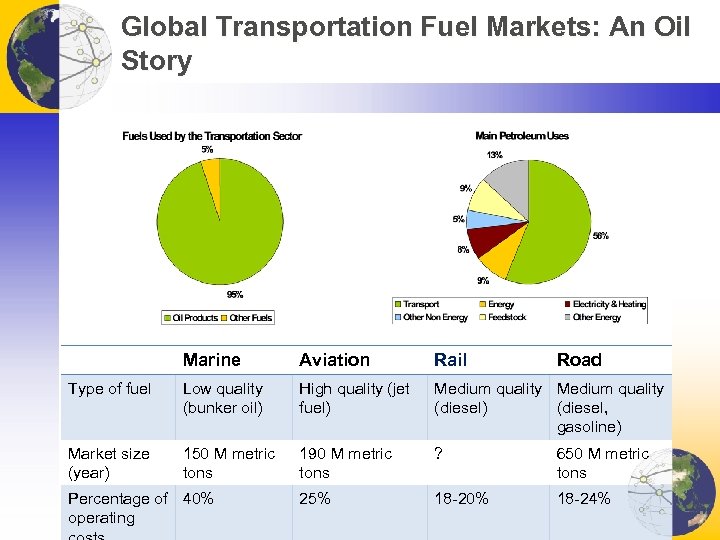

Global Transportation Fuel Markets: An Oil Story Marine Aviation Rail Type of fuel Low quality (bunker oil) High quality (jet fuel) Medium quality (diesel) (diesel, gasoline) Market size (year) 150 M metric tons 190 M metric tons ? 650 M metric tons 25% 18 -20% 18 -24% Percentage of 40% operating Road

Global Transportation Fuel Markets: An Oil Story Marine Aviation Rail Type of fuel Low quality (bunker oil) High quality (jet fuel) Medium quality (diesel) (diesel, gasoline) Market size (year) 150 M metric tons 190 M metric tons ? 650 M metric tons 25% 18 -20% 18 -24% Percentage of 40% operating Road

The Peak Oil Debate: Doomsayers and Nutjobs ■ Doomsayers • Often the firsts to anticipate a paradigm shift. • Understand the trend and its potential consequences. • Exaggerate the outcome, often through linear inference. • Fail (or refuse) to consider positive feedback effects (e. g. technology and conservation) and the complexity of economic systems. ■ Nutjobs • Blow things out of proportion, often taking advantage of an event to seek media attention. • Dogmatism (conspiracies) over analysis. • Almost always make the wrong assessment.

The Peak Oil Debate: Doomsayers and Nutjobs ■ Doomsayers • Often the firsts to anticipate a paradigm shift. • Understand the trend and its potential consequences. • Exaggerate the outcome, often through linear inference. • Fail (or refuse) to consider positive feedback effects (e. g. technology and conservation) and the complexity of economic systems. ■ Nutjobs • Blow things out of proportion, often taking advantage of an event to seek media attention. • Dogmatism (conspiracies) over analysis. • Almost always make the wrong assessment.

Demystifying Conspiracy Theories ■ We are running out of oil • We are running out of cheap oil options. ■ OPEC fixes oil prices • A dysfunctional cartel that can do little. • Each member does mostly want it wants. • Statements should be viewed as comic relief (e. g. Chavez). ■ Speculation drives oil prices • Somewhat (short term), but many can also lose their shirts. ■ High oil prices paralyze transportation • Not really. • Low oil prices promotes wasteful practices. • High oil prices force a reconsideration and a

Demystifying Conspiracy Theories ■ We are running out of oil • We are running out of cheap oil options. ■ OPEC fixes oil prices • A dysfunctional cartel that can do little. • Each member does mostly want it wants. • Statements should be viewed as comic relief (e. g. Chavez). ■ Speculation drives oil prices • Somewhat (short term), but many can also lose their shirts. ■ High oil prices paralyze transportation • Not really. • Low oil prices promotes wasteful practices. • High oil prices force a reconsideration and a

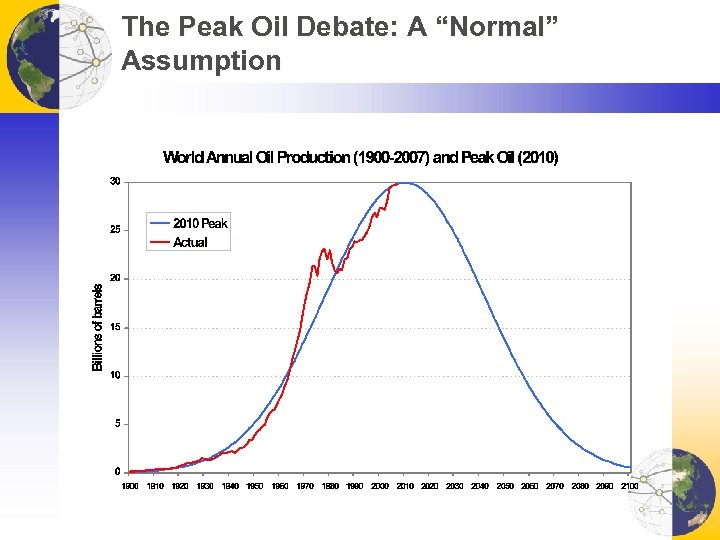

The Peak Oil Debate: A “Normal” Assumption

The Peak Oil Debate: A “Normal” Assumption

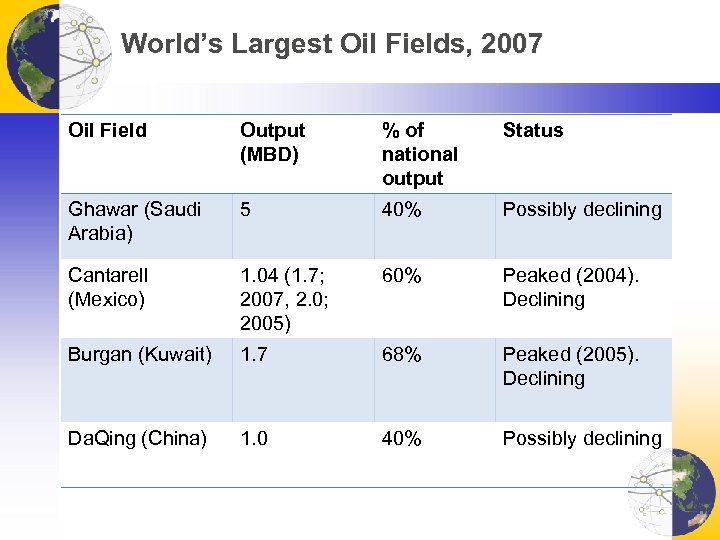

World’s Largest Oil Fields, 2007 Oil Field Output (MBD) % of national output Status Ghawar (Saudi Arabia) 5 40% Possibly declining Cantarell (Mexico) 1. 04 (1. 7; 2007, 2. 0; 2005) 60% Peaked (2004). Declining Burgan (Kuwait) 1. 7 68% Peaked (2005). Declining Da. Qing (China) 1. 0 40% Possibly declining

World’s Largest Oil Fields, 2007 Oil Field Output (MBD) % of national output Status Ghawar (Saudi Arabia) 5 40% Possibly declining Cantarell (Mexico) 1. 04 (1. 7; 2007, 2. 0; 2005) 60% Peaked (2004). Declining Burgan (Kuwait) 1. 7 68% Peaked (2005). Declining Da. Qing (China) 1. 0 40% Possibly declining

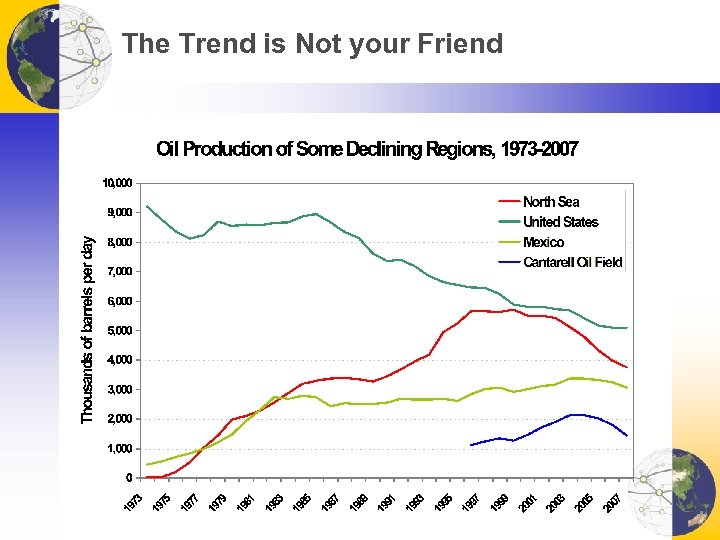

The Trend is Not your Friend

The Trend is Not your Friend

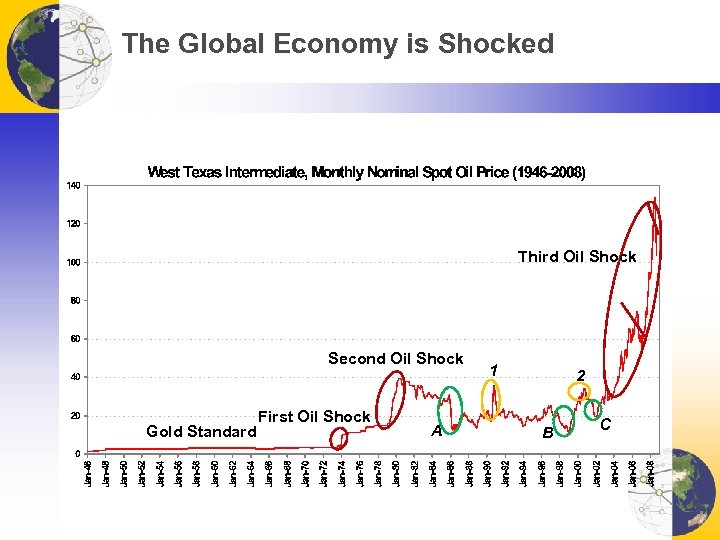

The Global Economy is Shocked Third Oil Shock Second Oil Shock Gold Standard First Oil Shock A 1 2 B C

The Global Economy is Shocked Third Oil Shock Second Oil Shock Gold Standard First Oil Shock A 1 2 B C

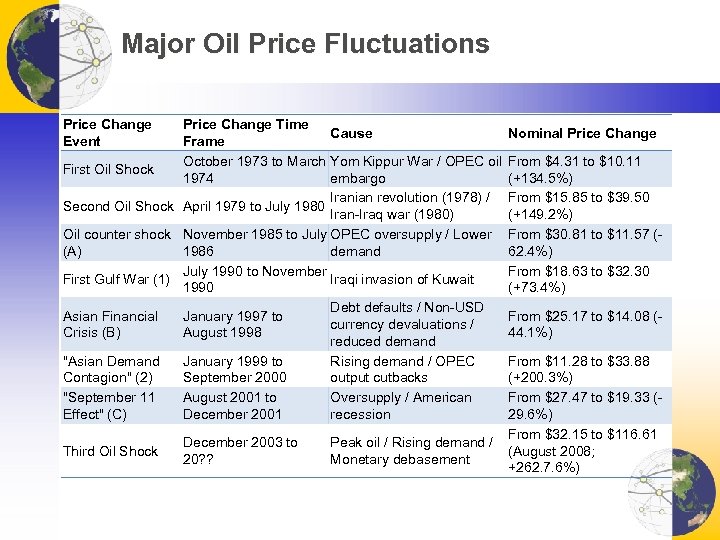

Major Oil Price Fluctuations Price Change Event Price Change Time Cause Frame October 1973 to March Yom Kippur War / OPEC oil First Oil Shock 1974 embargo Iranian revolution (1978) / Second Oil Shock April 1979 to July 1980 Iran-Iraq war (1980) Oil counter shock November 1985 to July OPEC oversupply / Lower (A) 1986 demand July 1990 to November First Gulf War (1) Iraqi invasion of Kuwait 1990 Debt defaults / Non-USD Asian Financial January 1997 to currency devaluations / Crisis (B) August 1998 reduced demand "Asian Demand January 1999 to Rising demand / OPEC Contagion" (2) September 2000 output cutbacks "September 11 August 2001 to Oversupply / American Effect" (C) December 2001 recession Third Oil Shock December 2003 to 20? ? Peak oil / Rising demand / Monetary debasement Nominal Price Change From $4. 31 to $10. 11 (+134. 5%) From $15. 85 to $39. 50 (+149. 2%) From $30. 81 to $11. 57 (62. 4%) From $18. 63 to $32. 30 (+73. 4%) From $25. 17 to $14. 08 (44. 1%) From $11. 28 to $33. 88 (+200. 3%) From $27. 47 to $19. 33 (29. 6%) From $32. 15 to $116. 61 (August 2008; +262. 7. 6%)

Major Oil Price Fluctuations Price Change Event Price Change Time Cause Frame October 1973 to March Yom Kippur War / OPEC oil First Oil Shock 1974 embargo Iranian revolution (1978) / Second Oil Shock April 1979 to July 1980 Iran-Iraq war (1980) Oil counter shock November 1985 to July OPEC oversupply / Lower (A) 1986 demand July 1990 to November First Gulf War (1) Iraqi invasion of Kuwait 1990 Debt defaults / Non-USD Asian Financial January 1997 to currency devaluations / Crisis (B) August 1998 reduced demand "Asian Demand January 1999 to Rising demand / OPEC Contagion" (2) September 2000 output cutbacks "September 11 August 2001 to Oversupply / American Effect" (C) December 2001 recession Third Oil Shock December 2003 to 20? ? Peak oil / Rising demand / Monetary debasement Nominal Price Change From $4. 31 to $10. 11 (+134. 5%) From $15. 85 to $39. 50 (+149. 2%) From $30. 81 to $11. 57 (62. 4%) From $18. 63 to $32. 30 (+73. 4%) From $25. 17 to $14. 08 (44. 1%) From $11. 28 to $33. 88 (+200. 3%) From $27. 47 to $19. 33 (29. 6%) From $32. 15 to $116. 61 (August 2008; +262. 7. 6%)

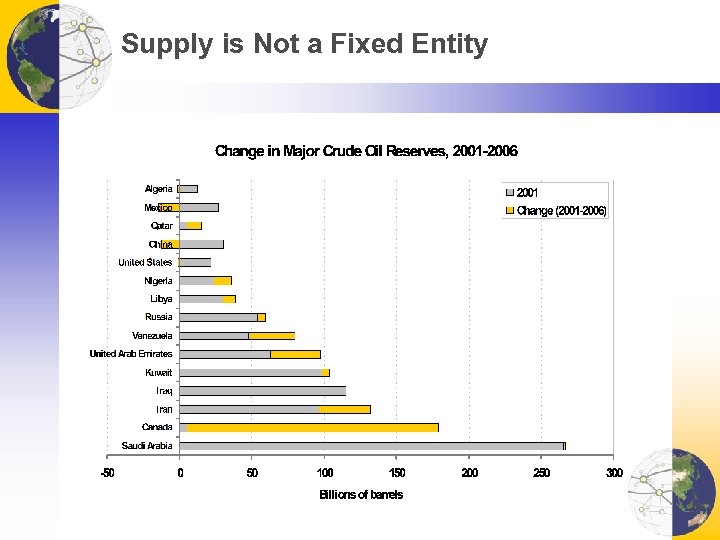

Supply is Not a Fixed Entity

Supply is Not a Fixed Entity

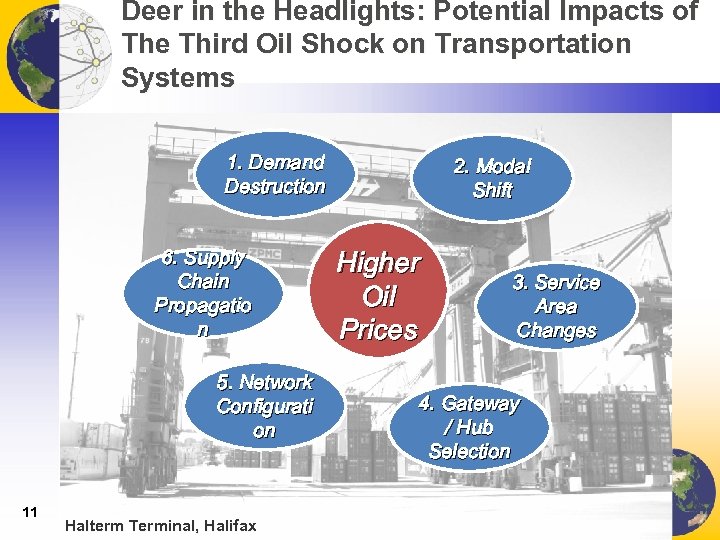

Deer in the Headlights: Potential Impacts of The Third Oil Shock on Transportation Systems 1. Demand Destruction 6. Supply Chain Propagatio n 5. Network Configurati on 11 Halterm Terminal, Halifax 2. Modal Shift Higher Oil Prices 3. Service Area Changes 4. Gateway / Hub Selection

Deer in the Headlights: Potential Impacts of The Third Oil Shock on Transportation Systems 1. Demand Destruction 6. Supply Chain Propagatio n 5. Network Configurati on 11 Halterm Terminal, Halifax 2. Modal Shift Higher Oil Prices 3. Service Area Changes 4. Gateway / Hub Selection

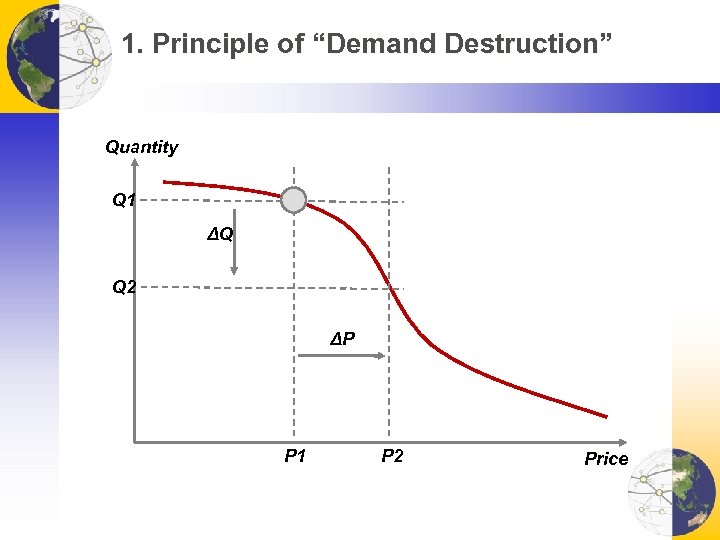

1. Principle of “Demand Destruction” Quantity Q 1 ΔQ Q 2 ΔP P 1 P 2 Price

1. Principle of “Demand Destruction” Quantity Q 1 ΔQ Q 2 ΔP P 1 P 2 Price

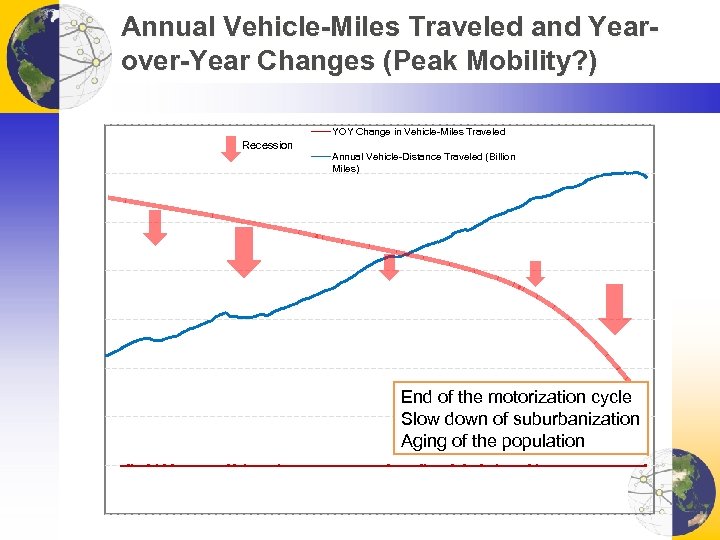

Annual Vehicle-Miles Traveled and Yearover-Year Changes (Peak Mobility? ) YOY Change in Vehicle-Miles Traveled Recession Annual Vehicle-Distance Traveled (Billion Miles) End of the motorization cycle Slow down of suburbanization Aging of the population

Annual Vehicle-Miles Traveled and Yearover-Year Changes (Peak Mobility? ) YOY Change in Vehicle-Miles Traveled Recession Annual Vehicle-Distance Traveled (Billion Miles) End of the motorization cycle Slow down of suburbanization Aging of the population

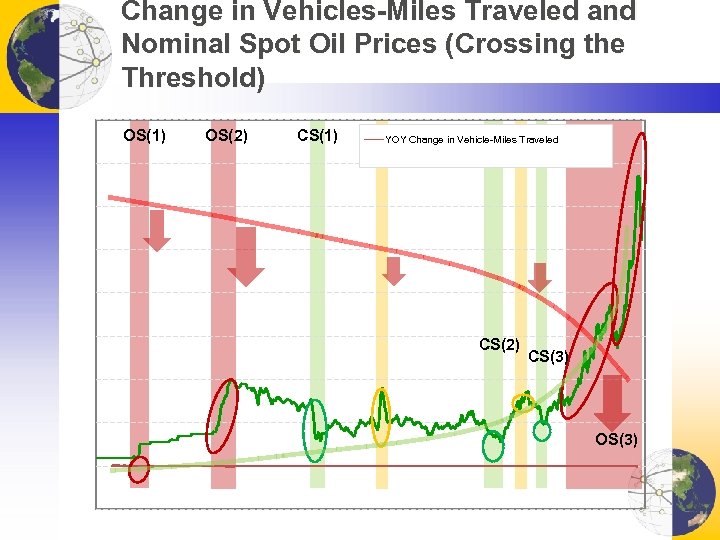

Change in Vehicles-Miles Traveled and Nominal Spot Oil Prices (Crossing the Threshold) OS(1) OS(2) CS(1) YOY Change in Vehicle-Miles Traveled CS(2) CS(3) OS(3)

Change in Vehicles-Miles Traveled and Nominal Spot Oil Prices (Crossing the Threshold) OS(1) OS(2) CS(1) YOY Change in Vehicle-Miles Traveled CS(2) CS(3) OS(3)

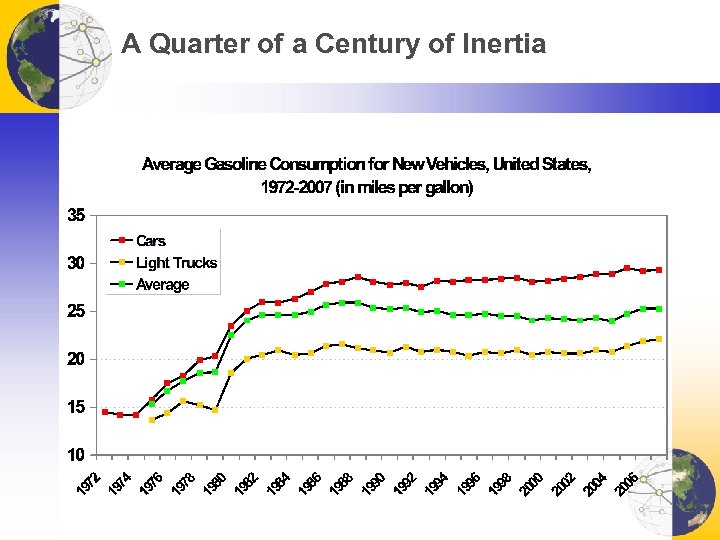

A Quarter of a Century of Inertia

A Quarter of a Century of Inertia

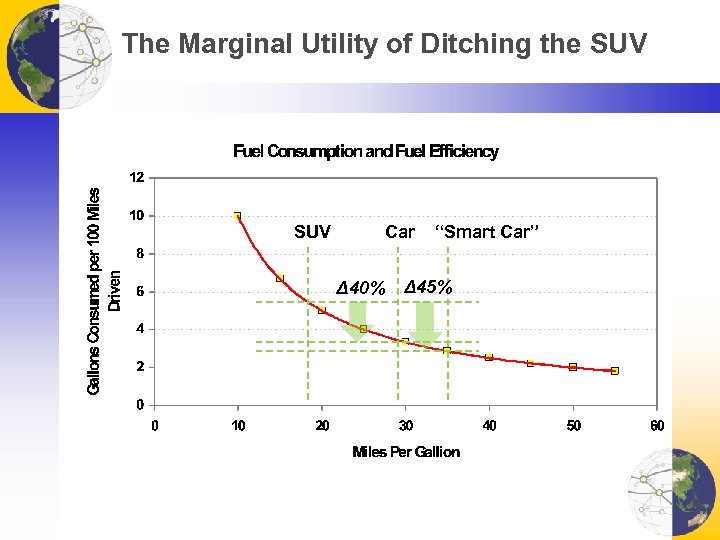

The Marginal Utility of Ditching the SUV Car Δ 40% “Smart Car” Δ 45%

The Marginal Utility of Ditching the SUV Car Δ 40% “Smart Car” Δ 45%

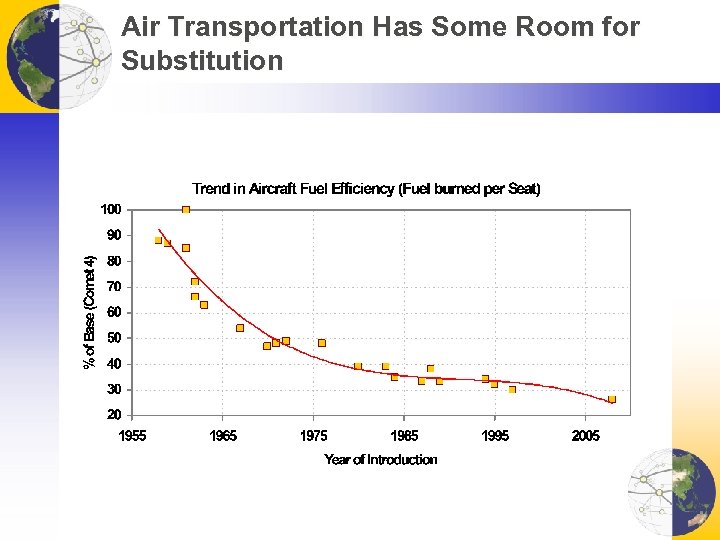

Air Transportation Has Some Room for Substitution

Air Transportation Has Some Room for Substitution

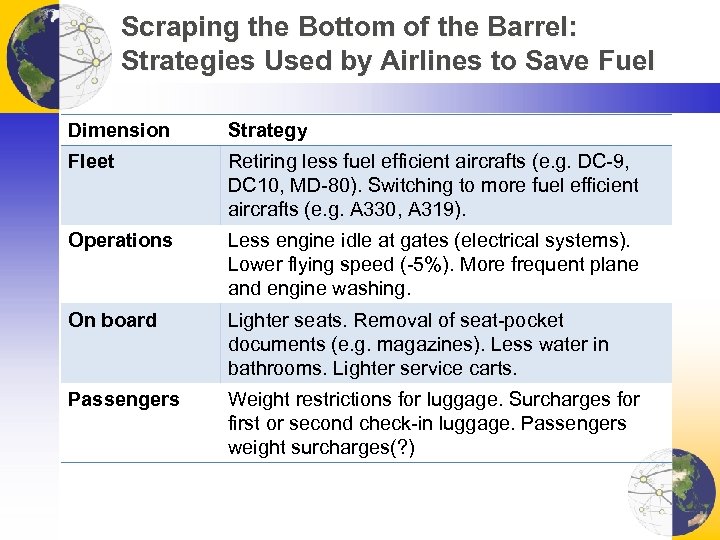

Scraping the Bottom of the Barrel: Strategies Used by Airlines to Save Fuel Dimension Strategy Fleet Retiring less fuel efficient aircrafts (e. g. DC-9, DC 10, MD-80). Switching to more fuel efficient aircrafts (e. g. A 330, A 319). Operations Less engine idle at gates (electrical systems). Lower flying speed (-5%). More frequent plane and engine washing. On board Lighter seats. Removal of seat-pocket documents (e. g. magazines). Less water in bathrooms. Lighter service carts. Passengers Weight restrictions for luggage. Surcharges for first or second check-in luggage. Passengers weight surcharges(? )

Scraping the Bottom of the Barrel: Strategies Used by Airlines to Save Fuel Dimension Strategy Fleet Retiring less fuel efficient aircrafts (e. g. DC-9, DC 10, MD-80). Switching to more fuel efficient aircrafts (e. g. A 330, A 319). Operations Less engine idle at gates (electrical systems). Lower flying speed (-5%). More frequent plane and engine washing. On board Lighter seats. Removal of seat-pocket documents (e. g. magazines). Less water in bathrooms. Lighter service carts. Passengers Weight restrictions for luggage. Surcharges for first or second check-in luggage. Passengers weight surcharges(? )

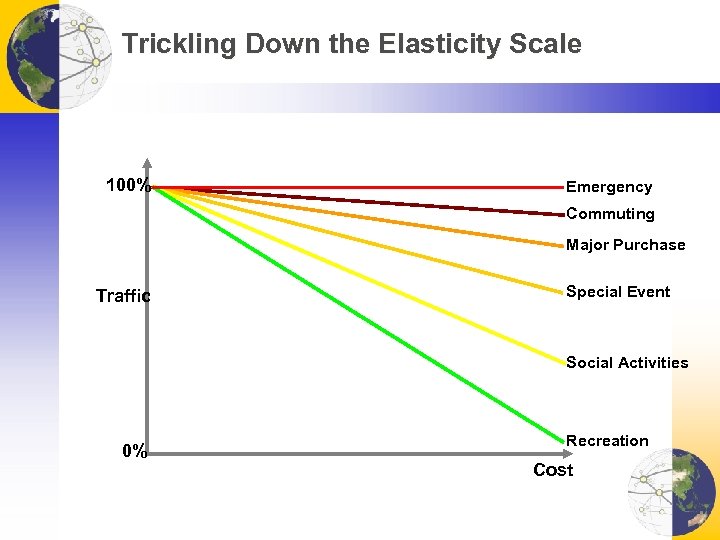

Trickling Down the Elasticity Scale 100% Emergency Commuting Major Purchase Traffic Special Event Social Activities 0% Recreation Cost

Trickling Down the Elasticity Scale 100% Emergency Commuting Major Purchase Traffic Special Event Social Activities 0% Recreation Cost

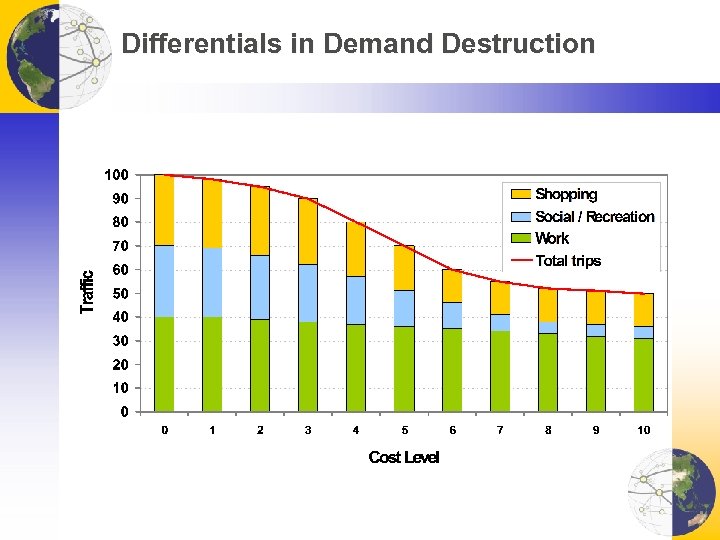

Differentials in Demand Destruction

Differentials in Demand Destruction

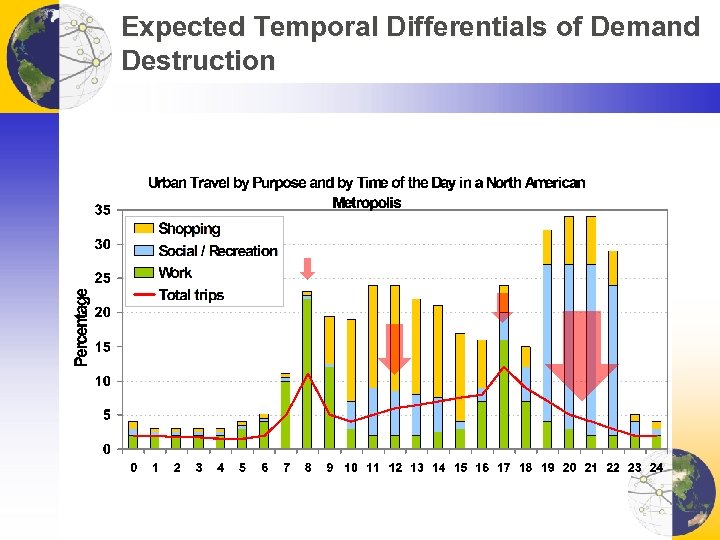

Expected Temporal Differentials of Demand Destruction

Expected Temporal Differentials of Demand Destruction

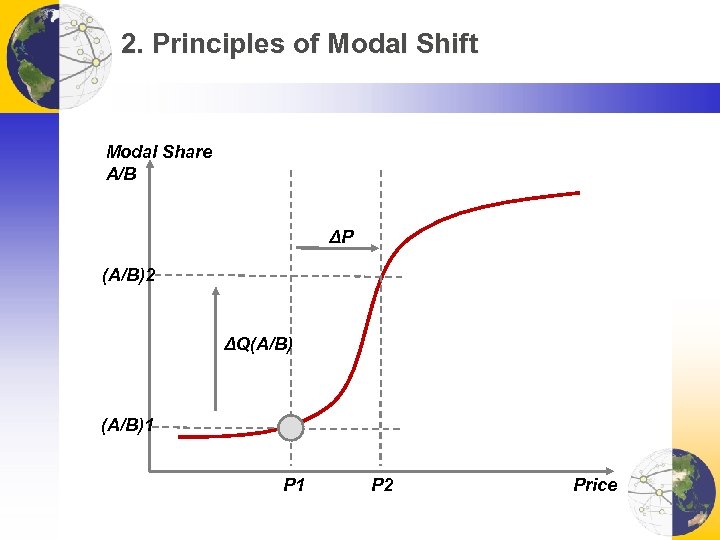

2. Principles of Modal Shift Modal Share A/B ΔP (A/B)2 ΔQ(A/B)1 P 2 Price

2. Principles of Modal Shift Modal Share A/B ΔP (A/B)2 ΔQ(A/B)1 P 2 Price

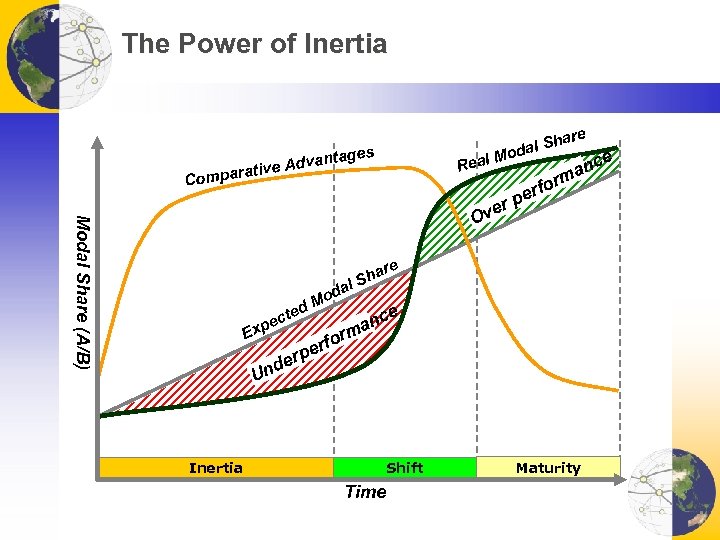

The Power of Inertia are ages Advant rative Real Compa Sh odal Modal Share (A/B) ver O ed d Mo al e anc m M r rfo pe e har S e anc rm rfo pe ct xpe E der n U Shift Inertia Time Maturity

The Power of Inertia are ages Advant rative Real Compa Sh odal Modal Share (A/B) ver O ed d Mo al e anc m M r rfo pe e har S e anc rm rfo pe ct xpe E der n U Shift Inertia Time Maturity

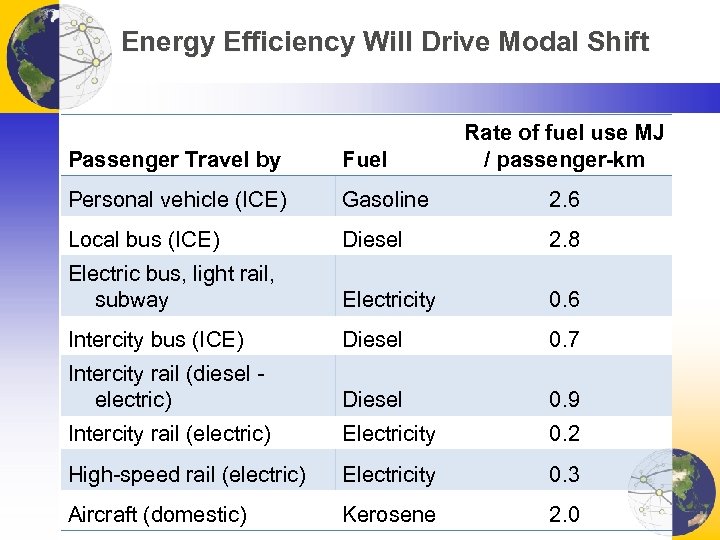

Energy Efficiency Will Drive Modal Shift Rate of fuel use MJ / passenger-km Passenger Travel by Fuel Personal vehicle (ICE) Gasoline 2. 6 Local bus (ICE) Diesel 2. 8 Electric bus, light rail, subway Electricity 0. 6 Intercity bus (ICE) Diesel 0. 7 Intercity rail (diesel electric) Diesel 0. 9 Intercity rail (electric) Electricity 0. 2 High-speed rail (electric) Electricity 0. 3 Aircraft (domestic) Kerosene 2. 0

Energy Efficiency Will Drive Modal Shift Rate of fuel use MJ / passenger-km Passenger Travel by Fuel Personal vehicle (ICE) Gasoline 2. 6 Local bus (ICE) Diesel 2. 8 Electric bus, light rail, subway Electricity 0. 6 Intercity bus (ICE) Diesel 0. 7 Intercity rail (diesel electric) Diesel 0. 9 Intercity rail (electric) Electricity 0. 2 High-speed rail (electric) Electricity 0. 3 Aircraft (domestic) Kerosene 2. 0

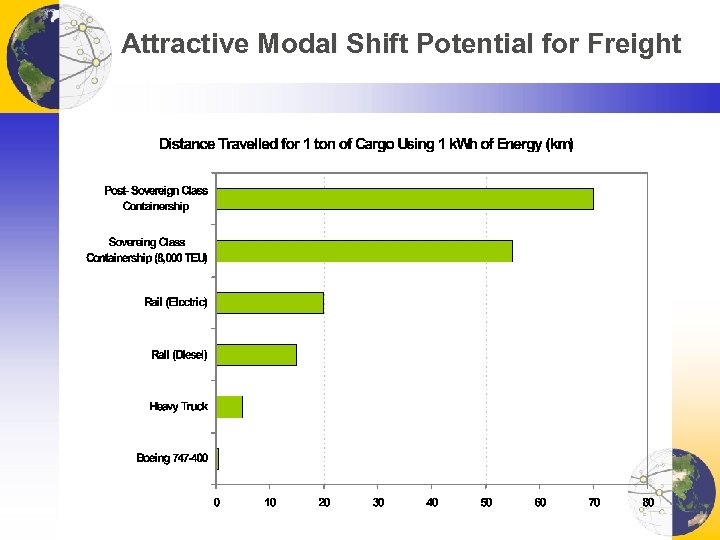

Attractive Modal Shift Potential for Freight

Attractive Modal Shift Potential for Freight

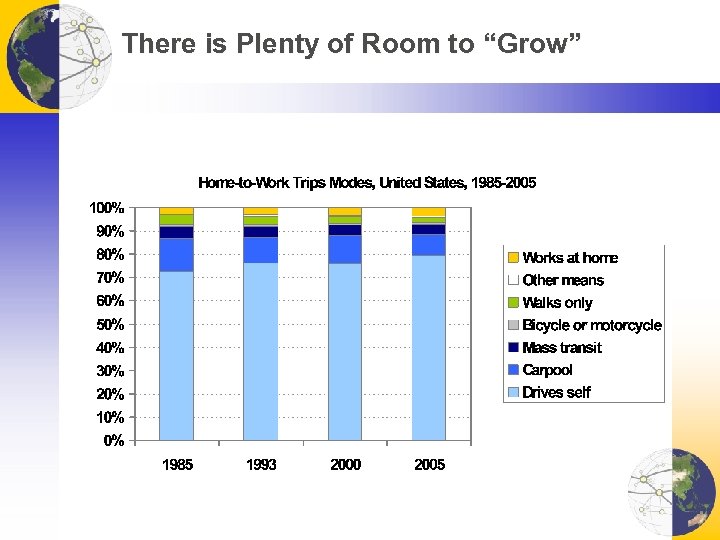

There is Plenty of Room to “Grow”

There is Plenty of Room to “Grow”

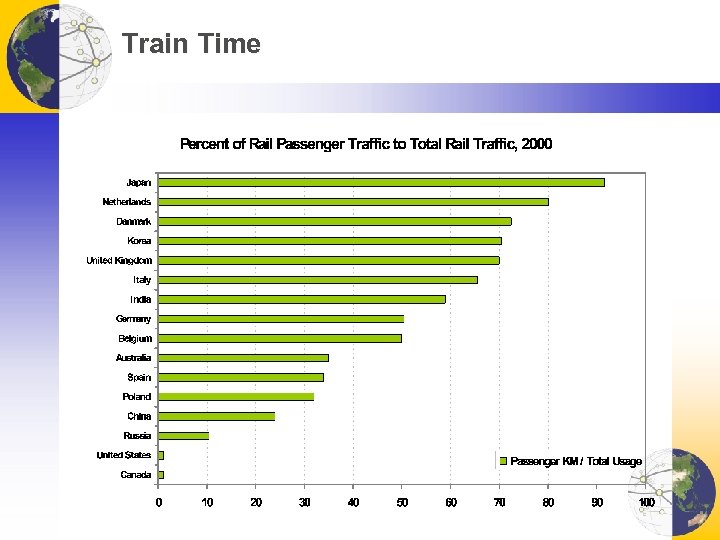

Train Time

Train Time

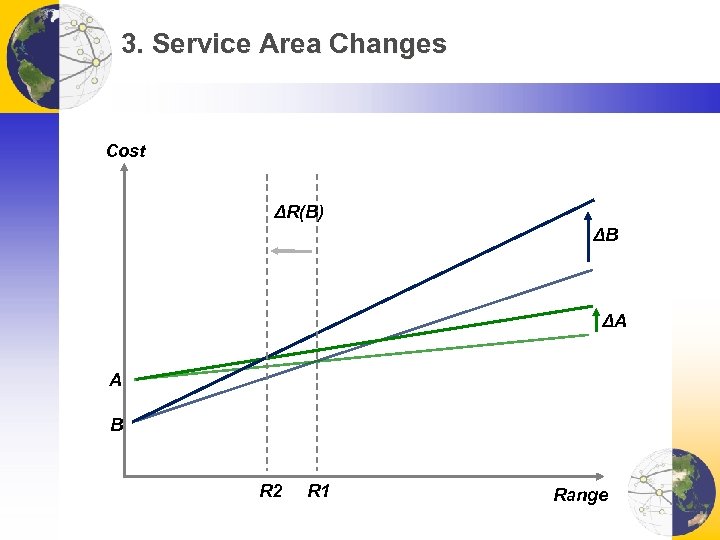

3. Service Area Changes Cost ΔR(B) ΔB ΔA A B R 2 R 1 Range

3. Service Area Changes Cost ΔR(B) ΔB ΔA A B R 2 R 1 Range

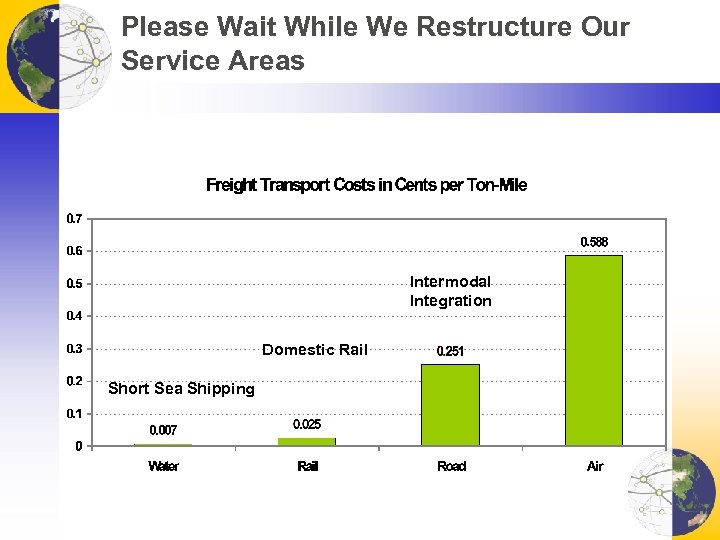

Please Wait While We Restructure Our Service Areas Intermodal Integration Domestic Rail Short Sea Shipping

Please Wait While We Restructure Our Service Areas Intermodal Integration Domestic Rail Short Sea Shipping

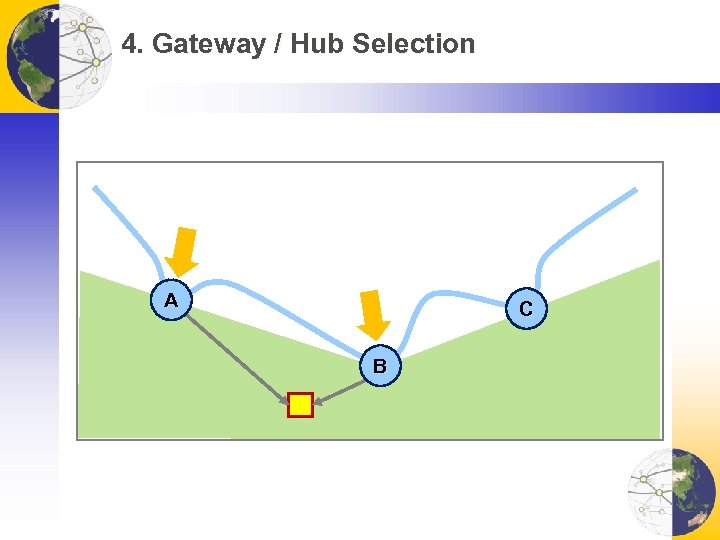

4. Gateway / Hub Selection A C B

4. Gateway / Hub Selection A C B

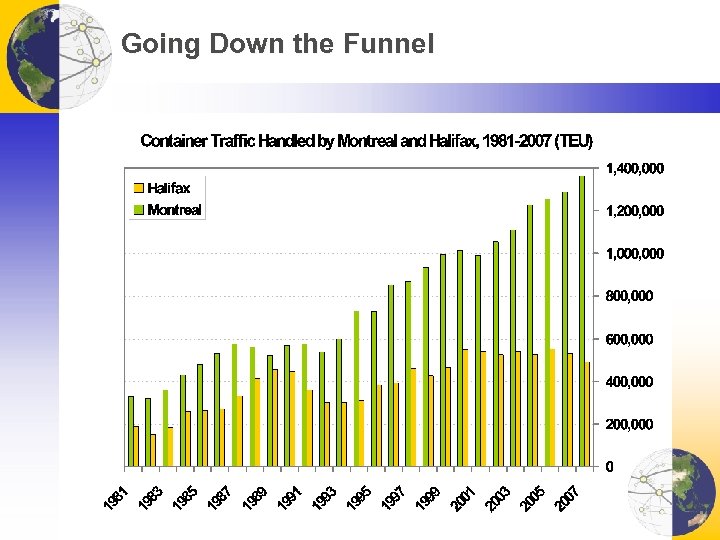

Going Down the Funnel

Going Down the Funnel

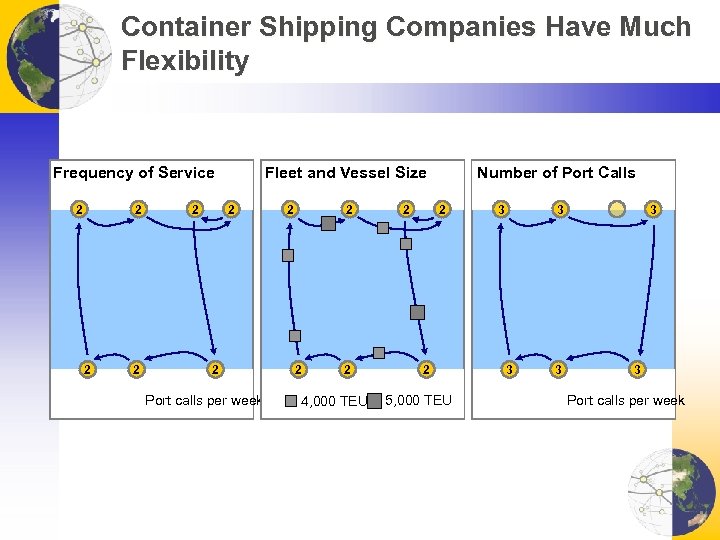

Container Shipping Companies Have Much Flexibility Fleet and Vessel Size Frequency of Service 2 2 2 2 Port calls per week 2 2 4, 000 TEU 2 Number of Port Calls 2 2 5, 000 TEU 3 3 3 Port calls per week

Container Shipping Companies Have Much Flexibility Fleet and Vessel Size Frequency of Service 2 2 2 2 Port calls per week 2 2 4, 000 TEU 2 Number of Port Calls 2 2 5, 000 TEU 3 3 3 Port calls per week

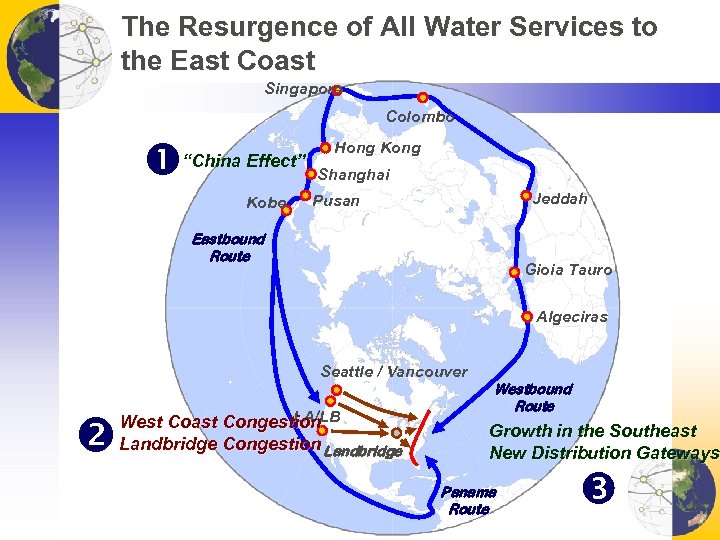

The Resurgence of All Water Services to the East Coast Singapore Colombo “China Effect” Kobe Hong Kong Shanghai Jeddah Pusan Eastbound Route Gioia Tauro Algeciras Seattle / Vancouver LA/LB West Coast Congestion Landbridge Westbound Route Growth in the Southeast New Distribution Gateways Panama Route

The Resurgence of All Water Services to the East Coast Singapore Colombo “China Effect” Kobe Hong Kong Shanghai Jeddah Pusan Eastbound Route Gioia Tauro Algeciras Seattle / Vancouver LA/LB West Coast Congestion Landbridge Westbound Route Growth in the Southeast New Distribution Gateways Panama Route

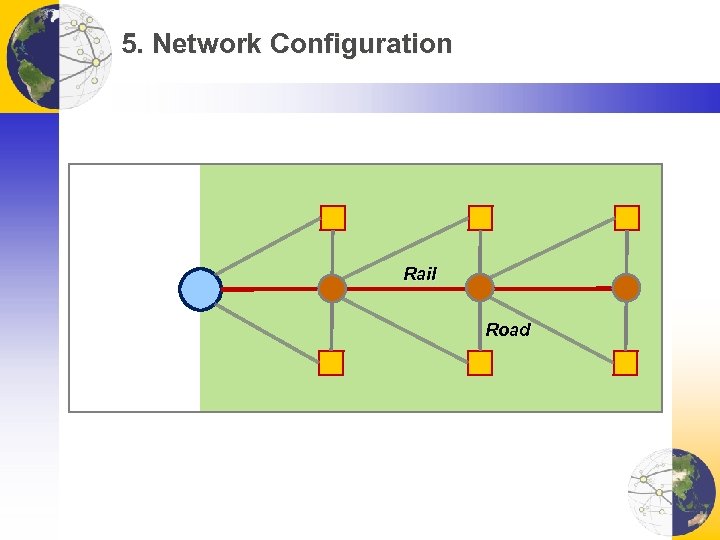

5. Network Configuration Rail Road

5. Network Configuration Rail Road

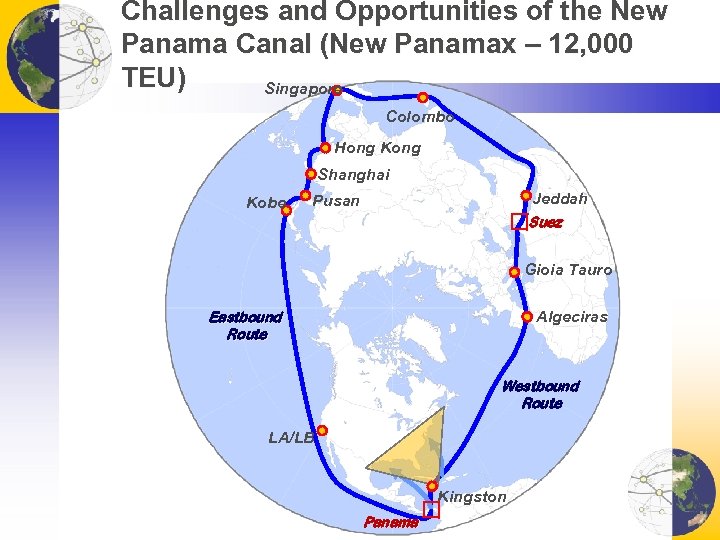

Challenges and Opportunities of the New Panama Canal (New Panamax – 12, 000 TEU) Singapore Colombo Hong Kong Shanghai Kobe Jeddah Pusan Suez Gioia Tauro Algeciras Eastbound Route Westbound Route LA/LB Kingston Panama

Challenges and Opportunities of the New Panama Canal (New Panamax – 12, 000 TEU) Singapore Colombo Hong Kong Shanghai Kobe Jeddah Pusan Suez Gioia Tauro Algeciras Eastbound Route Westbound Route LA/LB Kingston Panama

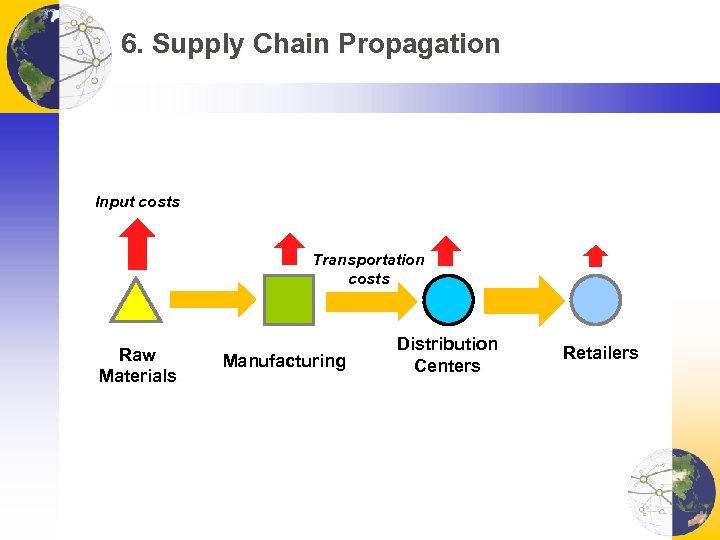

6. Supply Chain Propagation Input costs Transportation costs Raw Materials Manufacturing Distribution Centers Retailers

6. Supply Chain Propagation Input costs Transportation costs Raw Materials Manufacturing Distribution Centers Retailers

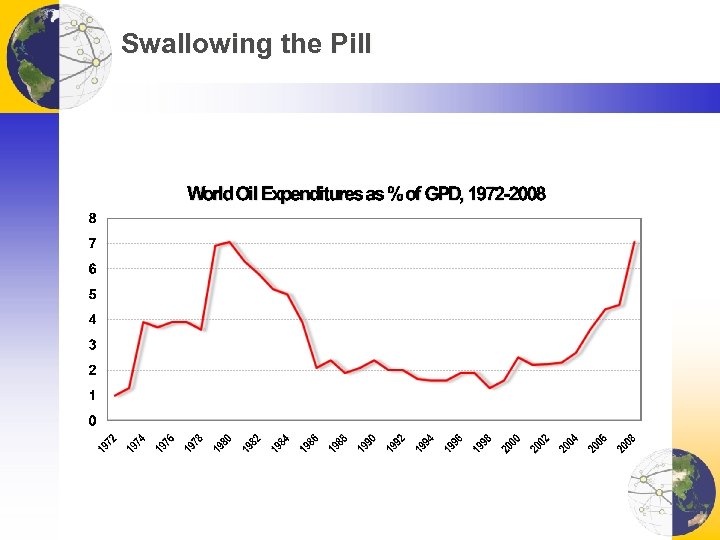

Swallowing the Pill

Swallowing the Pill

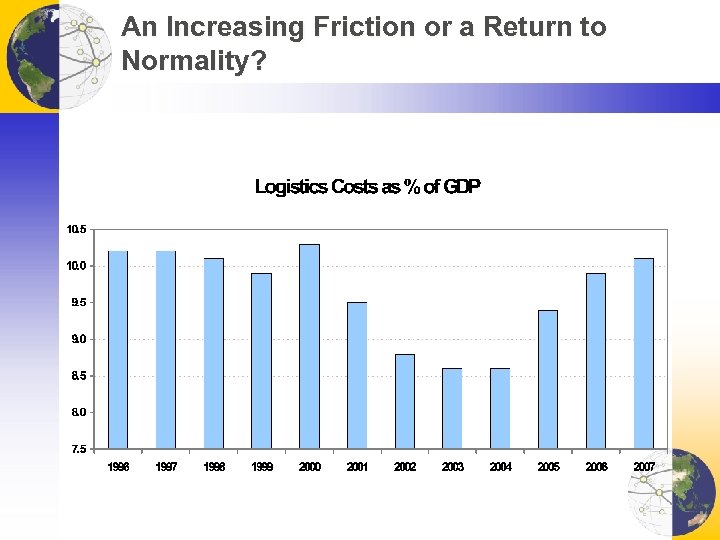

An Increasing Friction or a Return to Normality?

An Increasing Friction or a Return to Normality?

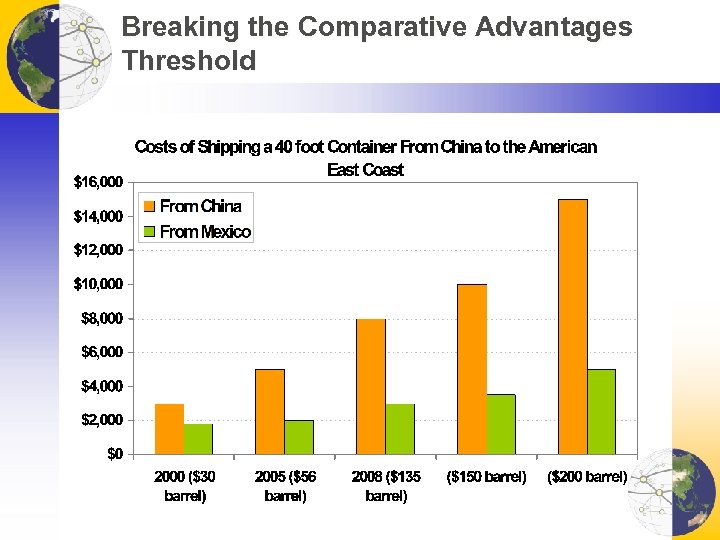

Breaking the Comparative Advantages Threshold

Breaking the Comparative Advantages Threshold

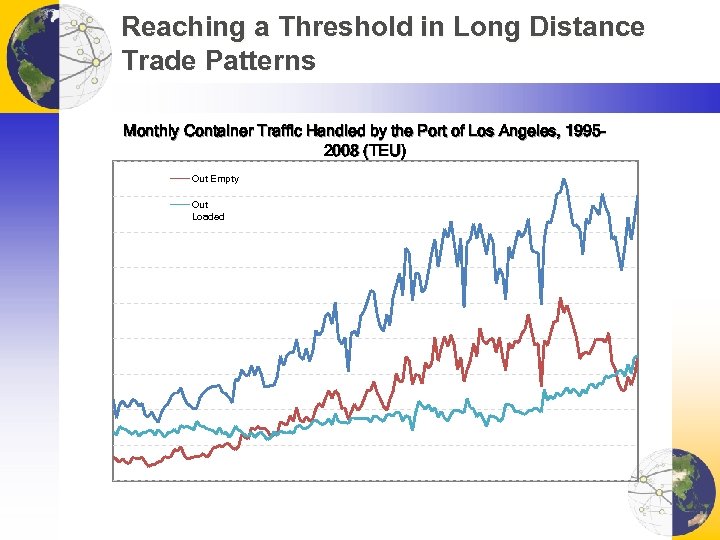

Reaching a Threshold in Long Distance Trade Patterns Monthly Container Traffic Handled by the Port of Los Angeles, 19952008 (TEU) Out Empty Out Loaded

Reaching a Threshold in Long Distance Trade Patterns Monthly Container Traffic Handled by the Port of Los Angeles, 19952008 (TEU) Out Empty Out Loaded

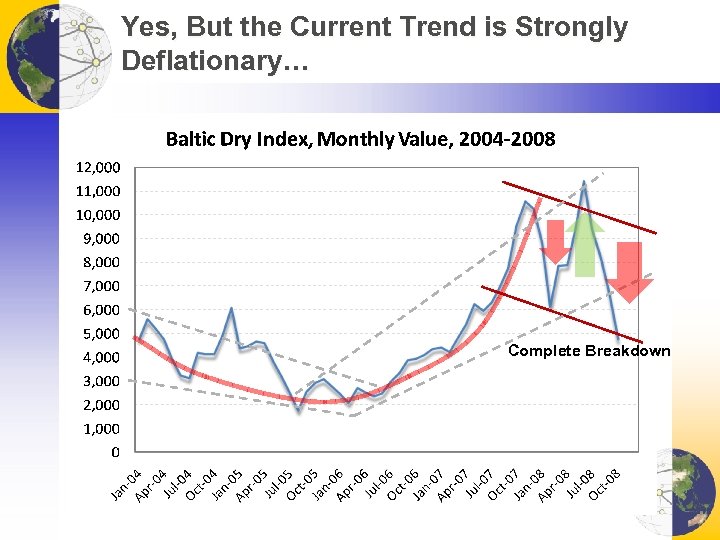

Yes, But the Current Trend is Strongly Deflationary… Complete Breakdown

Yes, But the Current Trend is Strongly Deflationary… Complete Breakdown

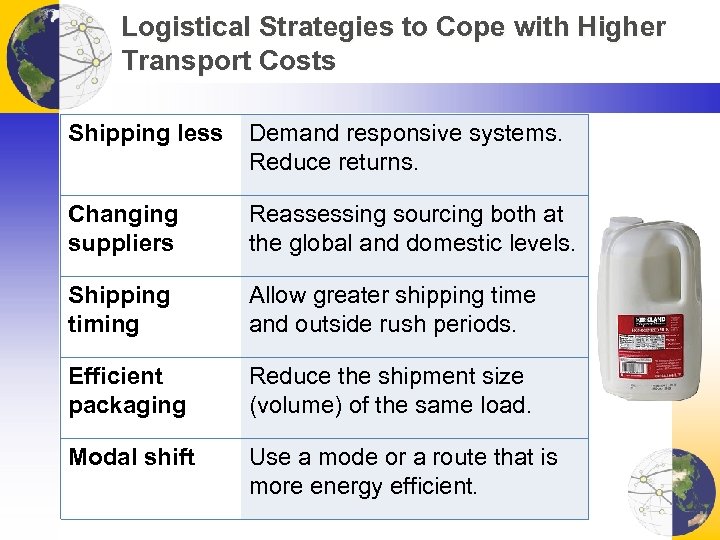

Logistical Strategies to Cope with Higher Transport Costs Shipping less Demand responsive systems. Reduce returns. Changing suppliers Reassessing sourcing both at the global and domestic levels. Shipping timing Allow greater shipping time and outside rush periods. Efficient packaging Reduce the shipment size (volume) of the same load. Modal shift Use a mode or a route that is more energy efficient.

Logistical Strategies to Cope with Higher Transport Costs Shipping less Demand responsive systems. Reduce returns. Changing suppliers Reassessing sourcing both at the global and domestic levels. Shipping timing Allow greater shipping time and outside rush periods. Efficient packaging Reduce the shipment size (volume) of the same load. Modal shift Use a mode or a route that is more energy efficient.

Conclusion: A Phase of Creative Destruction ■ Impacts complex to assess • Many factors, processes and consequences. • As usual, analyzing the transition is prone to understatements and exaggerations. • High energy prices have positive consequences … to a limit: • Force a reconsideration of practices and conservation. • Better allocation of resources. Reality

Conclusion: A Phase of Creative Destruction ■ Impacts complex to assess • Many factors, processes and consequences. • As usual, analyzing the transition is prone to understatements and exaggerations. • High energy prices have positive consequences … to a limit: • Force a reconsideration of practices and conservation. • Better allocation of resources. Reality