117588de803da72deabed80d43c1df76.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 49

Multidimensional Poverty Measurement Methods (MPMM) and the Two Official MPMM being applied in Mexico. Professor Julio Boltvinik jbolt@colmex. mx Second Peter Townsend Memorial Conference Bristol, January 2011

Multidimensional Poverty Measurement Methods (MPMM) and the Two Official MPMM being applied in Mexico. Professor Julio Boltvinik jbolt@colmex. mx Second Peter Townsend Memorial Conference Bristol, January 2011

Contents of this presentation 1. Origins of the need for MPMM and problems posed by it. 2. Some principles which I have developed in my search for a better solution to the problems posed by poverty measurement especially when it is multidimensional. 3. A typology of poverty measurement methods with emphasis on MPMM, the truly poor and the two official methods prevailing in Mexico.

Contents of this presentation 1. Origins of the need for MPMM and problems posed by it. 2. Some principles which I have developed in my search for a better solution to the problems posed by poverty measurement especially when it is multidimensional. 3. A typology of poverty measurement methods with emphasis on MPMM, the truly poor and the two official methods prevailing in Mexico.

1. Origins and problems of multidimensionality

1. Origins and problems of multidimensionality

Origins and problems of multidimensionality /I Poverty Measurement must be multidimensional because: 1. Human needs are Multiple (e. g. Maslow’s 7 needs or Max-Neef 10 needs), which are met through diverse satisfiers (goods & services, relations, activities, theories, capacities, institutions) made possible by a plurality of resources/well-being sources (WBS) (see slide on WBS). 2. Markets have limits → exchange value is not universal (some satisfiers -use values- are not exchange values, are not bought and sold, like theories and relations) → money cannot measure everything (e. g. some satisfiers & some WBS are not expressible in money terms) and so have to be expressed in their own terms (e. g. education in terms of number of educational grades; housing in terms of space person & quality of materials, etc. )

Origins and problems of multidimensionality /I Poverty Measurement must be multidimensional because: 1. Human needs are Multiple (e. g. Maslow’s 7 needs or Max-Neef 10 needs), which are met through diverse satisfiers (goods & services, relations, activities, theories, capacities, institutions) made possible by a plurality of resources/well-being sources (WBS) (see slide on WBS). 2. Markets have limits → exchange value is not universal (some satisfiers -use values- are not exchange values, are not bought and sold, like theories and relations) → money cannot measure everything (e. g. some satisfiers & some WBS are not expressible in money terms) and so have to be expressed in their own terms (e. g. education in terms of number of educational grades; housing in terms of space person & quality of materials, etc. )

Origins and problems of multidimensionality /II As a consequence, variables for Poverty Measurement (PM) might be: -Direct or indirect, (income is indirect as it refers not to the satisfaction of needs but to the level of the (in)capacity to satisfy them given its income, whereas years of schooling and quality of housing materials, are direct); -nominal, ordinal or cardinal (e. g. alternative solutions for water provision are nominal (once ordered become ordinal), whereas income is cardinal); This heterogeneity poses many challenges which I have solved through IPMM and the Principles I have formulated.

Origins and problems of multidimensionality /II As a consequence, variables for Poverty Measurement (PM) might be: -Direct or indirect, (income is indirect as it refers not to the satisfaction of needs but to the level of the (in)capacity to satisfy them given its income, whereas years of schooling and quality of housing materials, are direct); -nominal, ordinal or cardinal (e. g. alternative solutions for water provision are nominal (once ordered become ordinal), whereas income is cardinal); This heterogeneity poses many challenges which I have solved through IPMM and the Principles I have formulated.

The well-being sources Well-being of a Household (HH) or a person, depends on the following well-being sources: 1. Current income 2. Non-basic assets 3. Basic assets or family patrimony 4. Access to free goods & services (public consumption) 5. Knowledge and abilities 6. Available free time (there’s an additional slide on WBS)

The well-being sources Well-being of a Household (HH) or a person, depends on the following well-being sources: 1. Current income 2. Non-basic assets 3. Basic assets or family patrimony 4. Access to free goods & services (public consumption) 5. Knowledge and abilities 6. Available free time (there’s an additional slide on WBS)

2. Principles in the search for a better solution to problems posed by PM especially when it is multidimensional

2. Principles in the search for a better solution to problems posed by PM especially when it is multidimensional

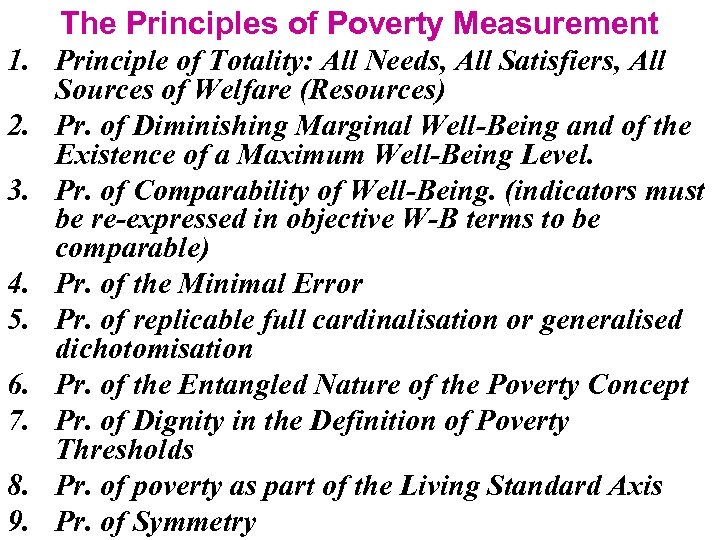

The Principles of Poverty Measurement 1. Principle of Totality: All Needs, All Satisfiers, All Sources of Welfare (Resources) 2. Pr. of Diminishing Marginal Well-Being and of the Existence of a Maximum Well-Being Level. 3. Pr. of Comparability of Well-Being. (indicators must be re-expressed in objective W-B terms to be comparable) 4. Pr. of the Minimal Error 5. Pr. of replicable full cardinalisation or generalised dichotomisation 6. Pr. of the Entangled Nature of the Poverty Concept 7. Pr. of Dignity in the Definition of Poverty Thresholds 8. Pr. of poverty as part of the Living Standard Axis 9. Pr. of Symmetry

The Principles of Poverty Measurement 1. Principle of Totality: All Needs, All Satisfiers, All Sources of Welfare (Resources) 2. Pr. of Diminishing Marginal Well-Being and of the Existence of a Maximum Well-Being Level. 3. Pr. of Comparability of Well-Being. (indicators must be re-expressed in objective W-B terms to be comparable) 4. Pr. of the Minimal Error 5. Pr. of replicable full cardinalisation or generalised dichotomisation 6. Pr. of the Entangled Nature of the Poverty Concept 7. Pr. of Dignity in the Definition of Poverty Thresholds 8. Pr. of poverty as part of the Living Standard Axis 9. Pr. of Symmetry

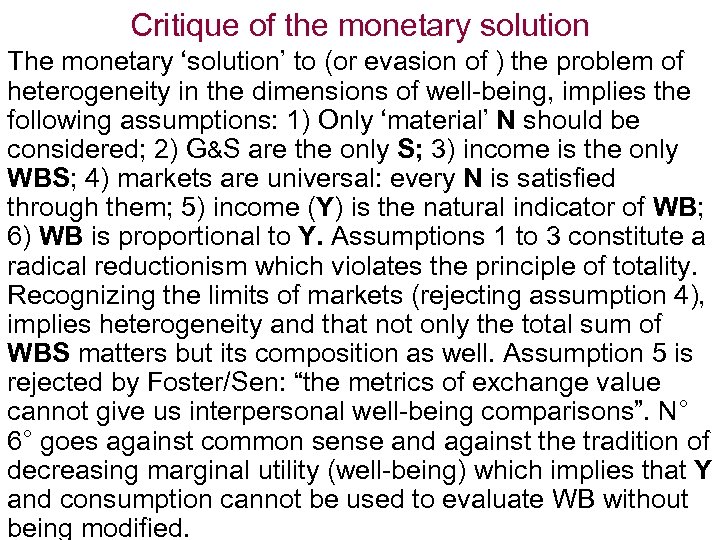

Critique of the monetary solution The monetary ‘solution’ to (or evasion of ) the problem of heterogeneity in the dimensions of well-being, implies the following assumptions: 1) Only ‘material’ N should be considered; 2) G&S are the only S; 3) income is the only WBS; 4) markets are universal: every N is satisfied through them; 5) income (Y) is the natural indicator of WB; 6) WB is proportional to Y. Assumptions 1 to 3 constitute a radical reductionism which violates the principle of totality. Recognizing the limits of markets (rejecting assumption 4), implies heterogeneity and that not only the total sum of WBS matters but its composition as well. Assumption 5 is rejected by Foster/Sen: “the metrics of exchange value cannot give us interpersonal well-being comparisons”. N° 6° goes against common sense and against the tradition of decreasing marginal utility (well-being) which implies that Y and consumption cannot be used to evaluate WB without being modified.

Critique of the monetary solution The monetary ‘solution’ to (or evasion of ) the problem of heterogeneity in the dimensions of well-being, implies the following assumptions: 1) Only ‘material’ N should be considered; 2) G&S are the only S; 3) income is the only WBS; 4) markets are universal: every N is satisfied through them; 5) income (Y) is the natural indicator of WB; 6) WB is proportional to Y. Assumptions 1 to 3 constitute a radical reductionism which violates the principle of totality. Recognizing the limits of markets (rejecting assumption 4), implies heterogeneity and that not only the total sum of WBS matters but its composition as well. Assumption 5 is rejected by Foster/Sen: “the metrics of exchange value cannot give us interpersonal well-being comparisons”. N° 6° goes against common sense and against the tradition of decreasing marginal utility (well-being) which implies that Y and consumption cannot be used to evaluate WB without being modified.

Note • For the verbal presentation at the Second Peter Townsend Memorial Conference, given time restrictions, the explication of Principles of Poverty Measurement is skipped, but it is included in the electronic version of this Power Point file. • Additionally, you have received in your pack a printed copy of my paper on these principles. • We will continue with slide 21

Note • For the verbal presentation at the Second Peter Townsend Memorial Conference, given time restrictions, the explication of Principles of Poverty Measurement is skipped, but it is included in the electronic version of this Power Point file. • Additionally, you have received in your pack a printed copy of my paper on these principles. • We will continue with slide 21

1. The Principle of Totality All Needs (N): depart from the complete human being with all his/her N, without cutting off her/his brain, heart, genitals; without reducing him/her to cattle. All Satisfiers (S), including relations, activities, capacities, institutions and knowledge/theories & not only G&S. All well-being sources or resources. Corollary: poverty is the incapacity of the household/person (given the totality of its WB sources) to satisfy all N.

1. The Principle of Totality All Needs (N): depart from the complete human being with all his/her N, without cutting off her/his brain, heart, genitals; without reducing him/her to cattle. All Satisfiers (S), including relations, activities, capacities, institutions and knowledge/theories & not only G&S. All well-being sources or resources. Corollary: poverty is the incapacity of the household/person (given the totality of its WB sources) to satisfy all N.

2. Principles of diminishing marginal WB and of the existence of a maximum WB To build objective WB measuring scales and advance in its measurement we should: 1) define the normative threshold (that divides WB from deprivation) as well as the absolute minimum and maximum (this last applying the principle enunciated below); 2) normalise the scales to homogenise through all dimensions the ranges of variation and fix the threshold at the same point. 3) Apply the principles of diminishing marginal WB (DMWB) above threshold and the principle of the existence of a maximum WB, based on the fact that C is the result of both T and G&S (Linder, 1970), but personal total T cannot be augmented nor accumulated. When G&S grow, effective C is limited by the existence of the fixed time factor, which generates DMWB and the absolute maximum, both of which should be expressed with an appropriate WB function.

2. Principles of diminishing marginal WB and of the existence of a maximum WB To build objective WB measuring scales and advance in its measurement we should: 1) define the normative threshold (that divides WB from deprivation) as well as the absolute minimum and maximum (this last applying the principle enunciated below); 2) normalise the scales to homogenise through all dimensions the ranges of variation and fix the threshold at the same point. 3) Apply the principles of diminishing marginal WB (DMWB) above threshold and the principle of the existence of a maximum WB, based on the fact that C is the result of both T and G&S (Linder, 1970), but personal total T cannot be augmented nor accumulated. When G&S grow, effective C is limited by the existence of the fixed time factor, which generates DMWB and the absolute maximum, both of which should be expressed with an appropriate WB function.

3. Principle of comparability For well-being (WB) indicators to be comparable, all (including income), have to be re-expressed in objective WB terms using a measurement scale that has to be built. A way to start building this common measurement scale is normalising the range of indicators by defining: 1. the threshold: achievement indicator AI =1; 2. the worse, AI=0; & 3. the conceptual maximum, above which WB can not be increased, AI=2.

3. Principle of comparability For well-being (WB) indicators to be comparable, all (including income), have to be re-expressed in objective WB terms using a measurement scale that has to be built. A way to start building this common measurement scale is normalising the range of indicators by defining: 1. the threshold: achievement indicator AI =1; 2. the worse, AI=0; & 3. the conceptual maximum, above which WB can not be increased, AI=2.

4. Principle of the minimal error Some poverty ‘measurer's’ argue that they do not include other dimensions distinct from Y or that they do not cardinalise ordinal indicators, because weights (and scores) are difficult or impossible to find. Thus, while they recognize the importance of the other WB dimensions, they carry out income poverty measurements, apparently ignoring the fact (or not giving importance to it) that they are thus assigning a zero weight to other sources of WB, which is (most likely) the largest possible error. The application of the principle of the minimal error implies overcoming these difficulties always in order to avoid the maximum error. Applying it implies not very elegant work as well as daring to formulate value judgements whenever necessary. Including the nonmonetary dimensions in multidimensional poverty measurement, and fully cardinalising them, are perhaps the two main tasks where the principle of the minimum error is applied.

4. Principle of the minimal error Some poverty ‘measurer's’ argue that they do not include other dimensions distinct from Y or that they do not cardinalise ordinal indicators, because weights (and scores) are difficult or impossible to find. Thus, while they recognize the importance of the other WB dimensions, they carry out income poverty measurements, apparently ignoring the fact (or not giving importance to it) that they are thus assigning a zero weight to other sources of WB, which is (most likely) the largest possible error. The application of the principle of the minimal error implies overcoming these difficulties always in order to avoid the maximum error. Applying it implies not very elegant work as well as daring to formulate value judgements whenever necessary. Including the nonmonetary dimensions in multidimensional poverty measurement, and fully cardinalising them, are perhaps the two main tasks where the principle of the minimum error is applied.

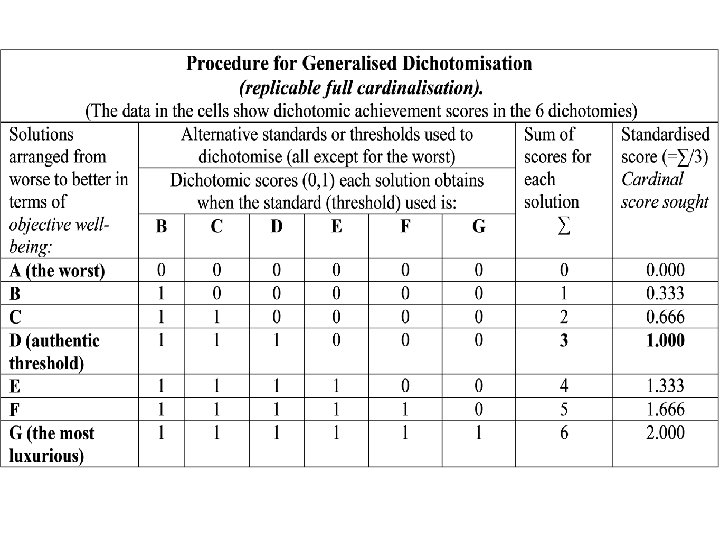

5. Principle of full replicable cardinalization or generalised dichotomisation In almost all multidimensional poverty measurements ordinal variables are converted into cardinality through dichotomisation, in which the worse solution is given a score of 1 and a score of 0 to the solution at the normative threshold, but intermediate solutions are also given a score of 1 even though they would deserve intermediate scores –like 0. 3, 0. 7. Equally, the solutions which are better than the norm are given a score of 0 although they would deserve negative deprivation values. All this implies an enormous loss of information which denies the principle of the minimal error (PME). In IPMM I have been applying a full cardinalization which rescues intermediate values and applies the PME. When James Foster (2007) cast doubt on the replicability of my procedure, I developed a replicable procedure: generalised dichotomisation, which I explain now.

5. Principle of full replicable cardinalization or generalised dichotomisation In almost all multidimensional poverty measurements ordinal variables are converted into cardinality through dichotomisation, in which the worse solution is given a score of 1 and a score of 0 to the solution at the normative threshold, but intermediate solutions are also given a score of 1 even though they would deserve intermediate scores –like 0. 3, 0. 7. Equally, the solutions which are better than the norm are given a score of 0 although they would deserve negative deprivation values. All this implies an enormous loss of information which denies the principle of the minimal error (PME). In IPMM I have been applying a full cardinalization which rescues intermediate values and applies the PME. When James Foster (2007) cast doubt on the replicability of my procedure, I developed a replicable procedure: generalised dichotomisation, which I explain now.

Steps/rules for generalised dichotomisation 1) Order alternative solutions in n groups from worse to best in terms of objective well-being. 2) Define n-1 dichotomies each one taking as standard or threshold (TH) a different group of solutions (except the worse) 3) Define the ‘true’ threshold (m group). 4) Obtain the achievement matrix (n by n-1) of 0, 1 scores (0: below TH; 1: on or above TH) for all n groups (rows) and n-1 dichotomies (columns). 5) ‘Average’ the scores of each group by dividing its sum by m-1 = groups from group 2 to group m (inclusive of both extremes). This ‘average’ is the cardinalised value of the achievement indicator (A) for each group. 6) Generalised dichotomisation generates equidistant cardinalisation; i. e. all values of A will be equidistant before rescaling

Steps/rules for generalised dichotomisation 1) Order alternative solutions in n groups from worse to best in terms of objective well-being. 2) Define n-1 dichotomies each one taking as standard or threshold (TH) a different group of solutions (except the worse) 3) Define the ‘true’ threshold (m group). 4) Obtain the achievement matrix (n by n-1) of 0, 1 scores (0: below TH; 1: on or above TH) for all n groups (rows) and n-1 dichotomies (columns). 5) ‘Average’ the scores of each group by dividing its sum by m-1 = groups from group 2 to group m (inclusive of both extremes). This ‘average’ is the cardinalised value of the achievement indicator (A) for each group. 6) Generalised dichotomisation generates equidistant cardinalisation; i. e. all values of A will be equidistant before rescaling

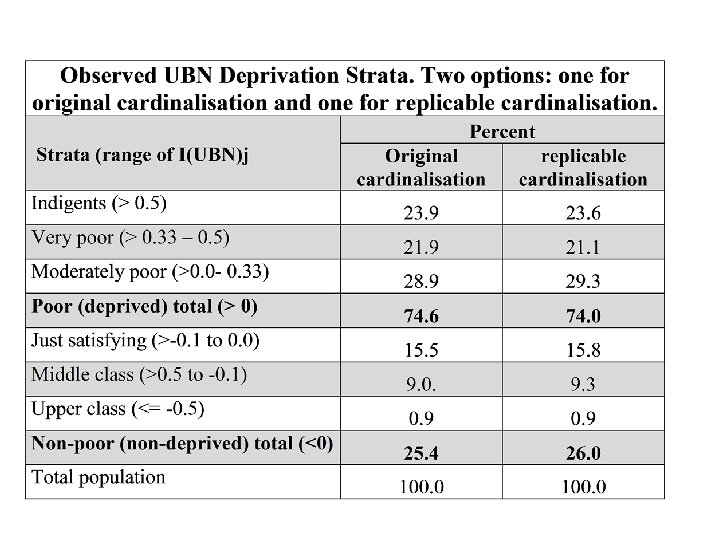

Appraising generalised Dichotomisation The experience of calculating IPMM poverty using Generalised Dichotomisation (GD) allows me to derive the following conclusions: 1. GD is equivalent to full cardinalization. 2. It generates an equidistant cardinalization with a long tradition in the social sciences (Sen, 1981). 3. Empirical results are almost identical to the usual procedure. 4. GD will be preferred by those who attach more value to replicability than to flexibility of judgement. 5. GD is the optimal procedure to minimise errors in the presence of ignorance but not when there is some knowledge on the consequences of each solution. 6. GD does not entail eliminating value judgements, which will be present in the ordering of solutions and in the definition of the true threshold 7. Full cardinalization is easily replicable through GD and its benefits are huge: going from very precarious methods to a method that allows for the calculation of all aggregate measures. 8. With respect to dichotomisation, GD always reduces measuring errors.

Appraising generalised Dichotomisation The experience of calculating IPMM poverty using Generalised Dichotomisation (GD) allows me to derive the following conclusions: 1. GD is equivalent to full cardinalization. 2. It generates an equidistant cardinalization with a long tradition in the social sciences (Sen, 1981). 3. Empirical results are almost identical to the usual procedure. 4. GD will be preferred by those who attach more value to replicability than to flexibility of judgement. 5. GD is the optimal procedure to minimise errors in the presence of ignorance but not when there is some knowledge on the consequences of each solution. 6. GD does not entail eliminating value judgements, which will be present in the ordering of solutions and in the definition of the true threshold 7. Full cardinalization is easily replicable through GD and its benefits are huge: going from very precarious methods to a method that allows for the calculation of all aggregate measures. 8. With respect to dichotomisation, GD always reduces measuring errors.

Principles, III 6. Entanglement Principle. The entangled nature of the poverty concept means that one cannot separate its description from its judgment/ evaluation. Judgment is an intrinsic part of poverty studies. 9. The symmetry principle, which applies the rules of elementary algebra, implies that truncated poverty lines have to be compared with the corresponding disposable income concept. e. g. food poverty has to be compared with disposable income for food and not with total current income as done by World Bank, ECLAC and the Mexican Government.

Principles, III 6. Entanglement Principle. The entangled nature of the poverty concept means that one cannot separate its description from its judgment/ evaluation. Judgment is an intrinsic part of poverty studies. 9. The symmetry principle, which applies the rules of elementary algebra, implies that truncated poverty lines have to be compared with the corresponding disposable income concept. e. g. food poverty has to be compared with disposable income for food and not with total current income as done by World Bank, ECLAC and the Mexican Government.

A typology of poverty measurement methods (with emphasis on MPMM, the truly poor and the two official methods prevailing in Mexico).

A typology of poverty measurement methods (with emphasis on MPMM, the truly poor and the two official methods prevailing in Mexico).

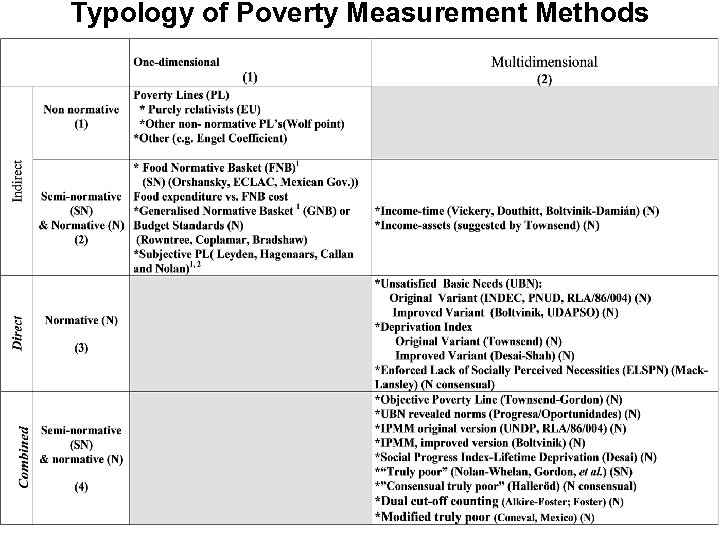

Typology of Poverty Measurement Methods

Typology of Poverty Measurement Methods

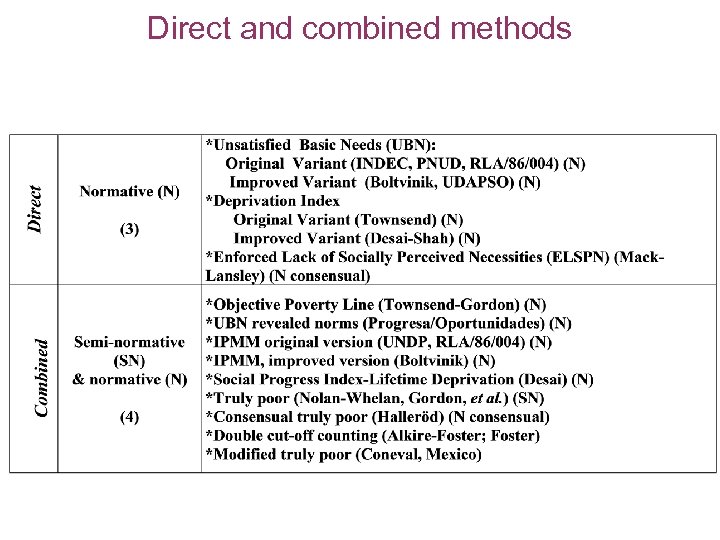

Direct and combined methods

Direct and combined methods

Note • For the verbal presentation, at the Second Peter Townsend Memorial Conference, given time restrictions, I will skip discussion of the noncombined methods with two exceptions, both direct multidimensional methods: UBN which is incorporated in both official MPMM being applied in Mexico, and Enforced Lack of Socially Perceived Necessities (Mack and Lansley) as it has been the origin of the truly poor approach. On the other hand, I will skip the first two combined methods listed in the previous slide. • So we will continue with slide 31

Note • For the verbal presentation, at the Second Peter Townsend Memorial Conference, given time restrictions, I will skip discussion of the noncombined methods with two exceptions, both direct multidimensional methods: UBN which is incorporated in both official MPMM being applied in Mexico, and Enforced Lack of Socially Perceived Necessities (Mack and Lansley) as it has been the origin of the truly poor approach. On the other hand, I will skip the first two combined methods listed in the previous slide. • So we will continue with slide 31

PL, Normative Food Basket (NFB) This is a semi-normative method as it combines a normative stand on food with a non-normative (empirical) position on all other needs. In all variants a normative food basket is defined and its cost is divided by the Engel coefficient, E, or proportion of household income allocated to food by households, to obtain the PL. In some applications (e. g. ECLAC and Government of Mexico 2000 -2006) the cost of the FNB is considered the extreme or food PL. What distinguishes variants is yhe group in which they observe E. Some select the poor for this observation, others, the whole population (M. Orshansky, who is the original designer of the procedure). A 3 th option is a reference stratum identified as satisfying its nutritional requirements (ECLAC). I have shown that the orthodox application of the third option implies measuring food poverty (i. e. households which, given their income, cannot buy the FNB) but that ECLAC has not been orthodox.

PL, Normative Food Basket (NFB) This is a semi-normative method as it combines a normative stand on food with a non-normative (empirical) position on all other needs. In all variants a normative food basket is defined and its cost is divided by the Engel coefficient, E, or proportion of household income allocated to food by households, to obtain the PL. In some applications (e. g. ECLAC and Government of Mexico 2000 -2006) the cost of the FNB is considered the extreme or food PL. What distinguishes variants is yhe group in which they observe E. Some select the poor for this observation, others, the whole population (M. Orshansky, who is the original designer of the procedure). A 3 th option is a reference stratum identified as satisfying its nutritional requirements (ECLAC). I have shown that the orthodox application of the third option implies measuring food poverty (i. e. households which, given their income, cannot buy the FNB) but that ECLAC has not been orthodox.

Food expenditure vs NFB cost. This is the obvious alternative to the NFB approach. It compares the amount spent by a household on food with the appropriate cost of the NFB. Boltvinik & Damián have applied it to Mexico, with the surprising result that it identifies the largest proportion of poverty as compared to all poverty measurement methods applied in Mexico. Its classification as direct or indirect method is not obvious. What the method identifies are households which, given the amount spent on food are potentially capable (or not) of meeting food needs, but there is no direct observation that, for instance, the composition of the amount consumed is such that nutritional needs are also met. For these reasons I have classified it as indirect onedimensional method for the purposes of the typology. In Section B I show that this procedure can be derived as a food poverty line from the FNB method.

Food expenditure vs NFB cost. This is the obvious alternative to the NFB approach. It compares the amount spent by a household on food with the appropriate cost of the NFB. Boltvinik & Damián have applied it to Mexico, with the surprising result that it identifies the largest proportion of poverty as compared to all poverty measurement methods applied in Mexico. Its classification as direct or indirect method is not obvious. What the method identifies are households which, given the amount spent on food are potentially capable (or not) of meeting food needs, but there is no direct observation that, for instance, the composition of the amount consumed is such that nutritional needs are also met. For these reasons I have classified it as indirect onedimensional method for the purposes of the typology. In Section B I show that this procedure can be derived as a food poverty line from the FNB method.

Generalised Norm Basket (GNB)/Budget Standards An entirely normative PMM. A complete normative basket of goods and services is defined. Its cost is the PL. It is the oldest (Rowntree) PMM but is seldom used (an exception is Mexico). In the UK, Bradshaw et al. have defined budget standards but did not use them to measure poverty. The arguments against it are very weak. Let’s take shoes. Every body agrees that it is shameful (and potentially harmful) to walk barefooted. Thus expenditure on shoes should be included in the GNB. With the argument that it is very difficult, or arbitrary as Atkinson says, to define the quality and quantity of shoes, these analysts end up including a total amount of expenditure (income) for all non-food items (a black box) in which they cannot be sure if any expenditure for shoes is included or not, thus leading to higher errors than those committed when not avoiding the ‘difficult’ or ‘arbitrary’ decisions.

Generalised Norm Basket (GNB)/Budget Standards An entirely normative PMM. A complete normative basket of goods and services is defined. Its cost is the PL. It is the oldest (Rowntree) PMM but is seldom used (an exception is Mexico). In the UK, Bradshaw et al. have defined budget standards but did not use them to measure poverty. The arguments against it are very weak. Let’s take shoes. Every body agrees that it is shameful (and potentially harmful) to walk barefooted. Thus expenditure on shoes should be included in the GNB. With the argument that it is very difficult, or arbitrary as Atkinson says, to define the quality and quantity of shoes, these analysts end up including a total amount of expenditure (income) for all non-food items (a black box) in which they cannot be sure if any expenditure for shoes is included or not, thus leading to higher errors than those committed when not avoiding the ‘difficult’ or ‘arbitrary’ decisions.

PL. Subjective Poverty Lines The variants included under this heading define threshold on the base of the opinions (perceptions) of interviewed population. There are basically two procedures: 1) The MIQ (minimum income) question addressed in terms of the income necessary for any household of a given size and structure. Average response to this question renders the PL. The other procedure requires the interviewed population to specify the income level which, for their own specific conditions they would qualify as “very bad”, “insufficient”, “good” & “very good”. Their current income is also registered. From that point, 2 procedures can be used, but the most transparent one is to estimate the media of all those who consider their own current income as sufficient. Although I have classified both procedures as normative, only the MIQ is really such.

PL. Subjective Poverty Lines The variants included under this heading define threshold on the base of the opinions (perceptions) of interviewed population. There are basically two procedures: 1) The MIQ (minimum income) question addressed in terms of the income necessary for any household of a given size and structure. Average response to this question renders the PL. The other procedure requires the interviewed population to specify the income level which, for their own specific conditions they would qualify as “very bad”, “insufficient”, “good” & “very good”. Their current income is also registered. From that point, 2 procedures can be used, but the most transparent one is to estimate the media of all those who consider their own current income as sufficient. Although I have classified both procedures as normative, only the MIQ is really such.

Income–time poverty (Vickery; Boltvinik) Vickery defines 2 poverty thresholds: income (M 0) and available adult hours for household management (T 0). HHs in M 0 require more time (T 1), and those in T 0 require more income (M 1). The line uniting M 0 T 1 & M 1 T 0 is the income-time poverty threshold. In the first point all domestic work is carried out by HH members; in the second all domestic work is performed by hired persons. In IPMM Boltvinik identified time poverty with an index of excess extra domestic work (EW). Norms are set on how many hours a week can an available person work extra domestically, or the sum of both. Time required for domestic work is calculated as dependent on size of HH, presence of small children, and an index of domestic work intensity based on a set of indicators. Total weekly available time minus domestic net work requirements (net of domestic work performed by paid personnel) renders available time for extra domestic work, which is compared with observed hours of weekly extra domestic work to obtain EW. Current income is divided into EW to obtain “income without EW and performing required domestic work”. Introduction of the time dimension changes radically the nature of PMM.

Income–time poverty (Vickery; Boltvinik) Vickery defines 2 poverty thresholds: income (M 0) and available adult hours for household management (T 0). HHs in M 0 require more time (T 1), and those in T 0 require more income (M 1). The line uniting M 0 T 1 & M 1 T 0 is the income-time poverty threshold. In the first point all domestic work is carried out by HH members; in the second all domestic work is performed by hired persons. In IPMM Boltvinik identified time poverty with an index of excess extra domestic work (EW). Norms are set on how many hours a week can an available person work extra domestically, or the sum of both. Time required for domestic work is calculated as dependent on size of HH, presence of small children, and an index of domestic work intensity based on a set of indicators. Total weekly available time minus domestic net work requirements (net of domestic work performed by paid personnel) renders available time for extra domestic work, which is compared with observed hours of weekly extra domestic work to obtain EW. Current income is divided into EW to obtain “income without EW and performing required domestic work”. Introduction of the time dimension changes radically the nature of PMM.

Townsend’s Deprivation Index & Desai-Shah Improved Variant. Townsend calculated a deprivation index which can be seen as a direct method. This he did in chapter 6 of his great book with 2 indicators which he chose for heuristic purposes from the 60 he had built. Although Townsend did not go to identify poverty with this index, this can be done if a poverty criterion is defined (e. g. a score of 2 or more). Desai and Shah proposed to use a continuous measure which can be used for each HH and which is adequate to calculate aggregate poverty measures, thus overcoming some of the limitations of Townsend’s Index. In other words they propose full cardinalization, beyond dichotomies, but they do it by expressing all consumption experience as events, whose frequency can be obtained by a questionnaire and then the modal frequencies become the normative values. Having frequencies below the norms, due to lack of resources is a sign of deprivation. Lack of resources is separated from tastes through econometric analysis. It has not been applied.

Townsend’s Deprivation Index & Desai-Shah Improved Variant. Townsend calculated a deprivation index which can be seen as a direct method. This he did in chapter 6 of his great book with 2 indicators which he chose for heuristic purposes from the 60 he had built. Although Townsend did not go to identify poverty with this index, this can be done if a poverty criterion is defined (e. g. a score of 2 or more). Desai and Shah proposed to use a continuous measure which can be used for each HH and which is adequate to calculate aggregate poverty measures, thus overcoming some of the limitations of Townsend’s Index. In other words they propose full cardinalization, beyond dichotomies, but they do it by expressing all consumption experience as events, whose frequency can be obtained by a questionnaire and then the modal frequencies become the normative values. Having frequencies below the norms, due to lack of resources is a sign of deprivation. Lack of resources is separated from tastes through econometric analysis. It has not been applied.

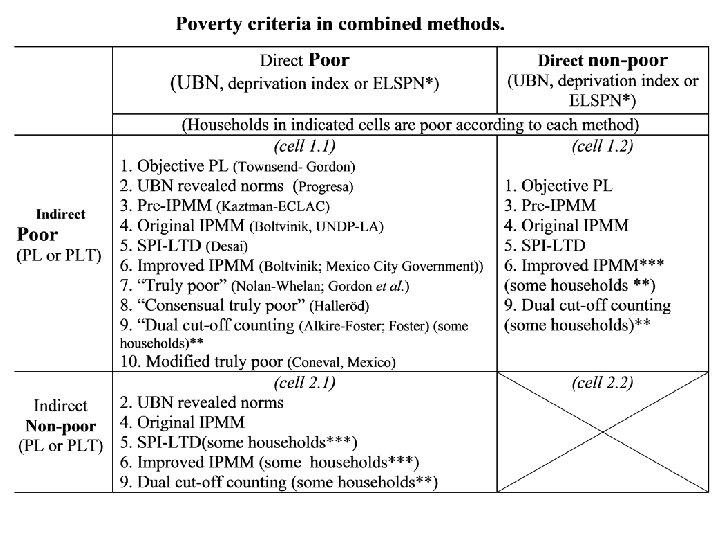

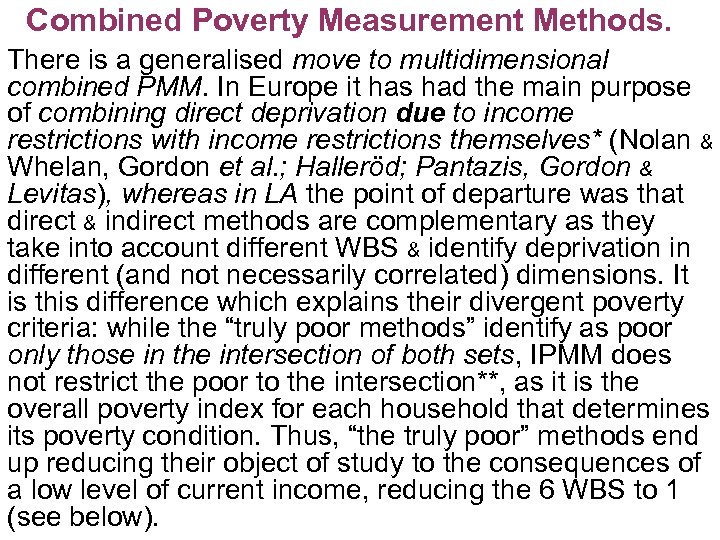

Combined Poverty Measurement Methods. There is a generalised move to multidimensional combined PMM. In Europe it has had the main purpose of combining direct deprivation due to income restrictions with income restrictions themselves* (Nolan & Whelan, Gordon et al. ; Halleröd; Pantazis, Gordon & Levitas), whereas in LA the point of departure was that direct & indirect methods are complementary as they take into account different WBS & identify deprivation in different (and not necessarily correlated) dimensions. It is this difference which explains their divergent poverty criteria: while the “truly poor methods” identify as poor only those in the intersection of both sets, IPMM does not restrict the poor to the intersection**, as it is the overall poverty index for each household that determines its poverty condition. Thus, “the truly poor” methods end up reducing their object of study to the consequences of a low level of current income, reducing the 6 WBS to 1 (see below).

Combined Poverty Measurement Methods. There is a generalised move to multidimensional combined PMM. In Europe it has had the main purpose of combining direct deprivation due to income restrictions with income restrictions themselves* (Nolan & Whelan, Gordon et al. ; Halleröd; Pantazis, Gordon & Levitas), whereas in LA the point of departure was that direct & indirect methods are complementary as they take into account different WBS & identify deprivation in different (and not necessarily correlated) dimensions. It is this difference which explains their divergent poverty criteria: while the “truly poor methods” identify as poor only those in the intersection of both sets, IPMM does not restrict the poor to the intersection**, as it is the overall poverty index for each household that determines its poverty condition. Thus, “the truly poor” methods end up reducing their object of study to the consequences of a low level of current income, reducing the 6 WBS to 1 (see below).

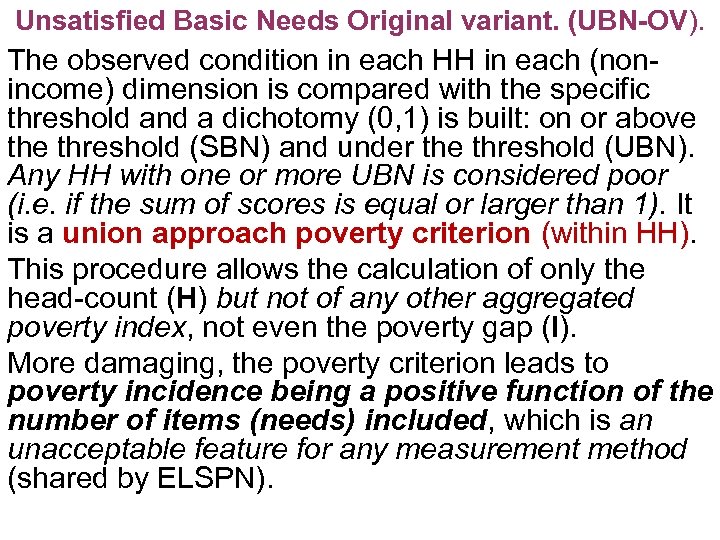

Unsatisfied Basic Needs Original variant. (UBN-OV). The observed condition in each HH in each (nonincome) dimension is compared with the specific threshold and a dichotomy (0, 1) is built: on or above threshold (SBN) and under the threshold (UBN). Any HH with one or more UBN is considered poor (i. e. if the sum of scores is equal or larger than 1). It is a union approach poverty criterion (within HH). This procedure allows the calculation of only the head-count (H) but not of any other aggregated poverty index, not even the poverty gap (I). More damaging, the poverty criterion leads to poverty incidence being a positive function of the number of items (needs) included, which is an unacceptable feature for any measurement method (shared by ELSPN).

Unsatisfied Basic Needs Original variant. (UBN-OV). The observed condition in each HH in each (nonincome) dimension is compared with the specific threshold and a dichotomy (0, 1) is built: on or above threshold (SBN) and under the threshold (UBN). Any HH with one or more UBN is considered poor (i. e. if the sum of scores is equal or larger than 1). It is a union approach poverty criterion (within HH). This procedure allows the calculation of only the head-count (H) but not of any other aggregated poverty index, not even the poverty gap (I). More damaging, the poverty criterion leads to poverty incidence being a positive function of the number of items (needs) included, which is an unacceptable feature for any measurement method (shared by ELSPN).

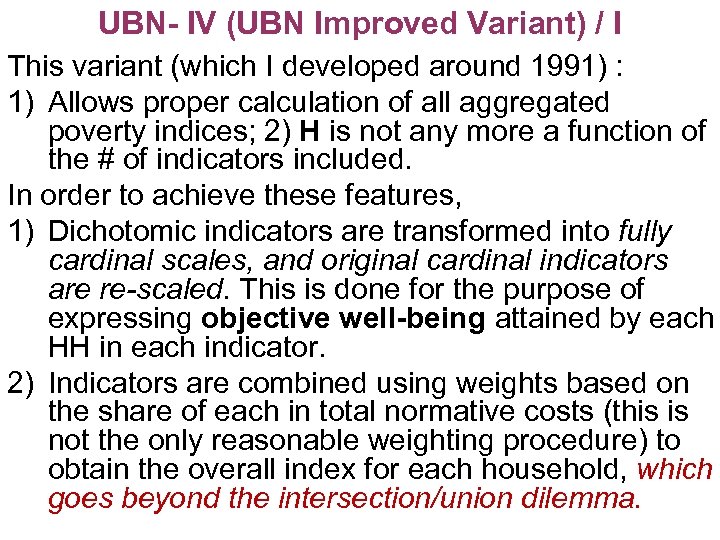

UBN- IV (UBN Improved Variant) / I This variant (which I developed around 1991) : 1) Allows proper calculation of all aggregated poverty indices; 2) H is not any more a function of the # of indicators included. In order to achieve these features, 1) Dichotomic indicators are transformed into fully cardinal scales, and original cardinal indicators are re-scaled. This is done for the purpose of expressing objective well-being attained by each HH in each indicator. 2) Indicators are combined using weights based on the share of each in total normative costs (this is not the only reasonable weighting procedure) to obtain the overall index for each household, which goes beyond the intersection/union dilemma.

UBN- IV (UBN Improved Variant) / I This variant (which I developed around 1991) : 1) Allows proper calculation of all aggregated poverty indices; 2) H is not any more a function of the # of indicators included. In order to achieve these features, 1) Dichotomic indicators are transformed into fully cardinal scales, and original cardinal indicators are re-scaled. This is done for the purpose of expressing objective well-being attained by each HH in each indicator. 2) Indicators are combined using weights based on the share of each in total normative costs (this is not the only reasonable weighting procedure) to obtain the overall index for each household, which goes beyond the intersection/union dilemma.

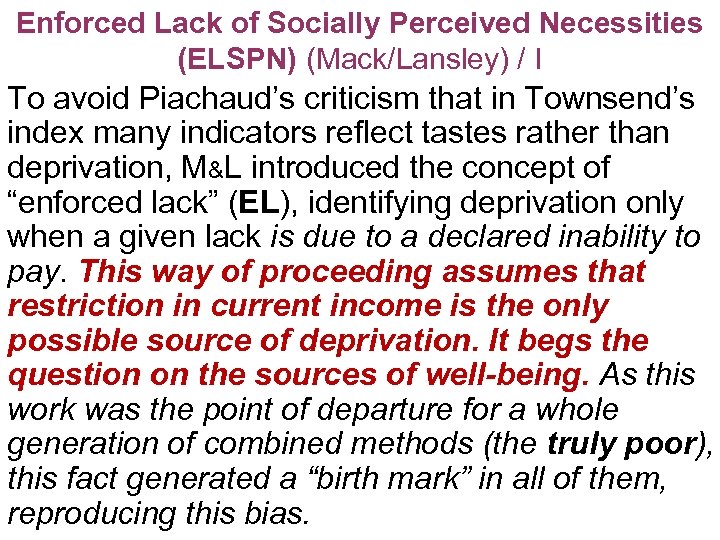

Enforced Lack of Socially Perceived Necessities (ELSPN) (Mack/Lansley) / I To avoid Piachaud’s criticism that in Townsend’s index many indicators reflect tastes rather than deprivation, M&L introduced the concept of “enforced lack” (EL), identifying deprivation only when a given lack is due to a declared inability to pay. This way of proceeding assumes that restriction in current income is the only possible source of deprivation. It begs the question on the sources of well-being. As this work was the point of departure for a whole generation of combined methods (the truly poor), this fact generated a “birth mark” in all of them, reproducing this bias.

Enforced Lack of Socially Perceived Necessities (ELSPN) (Mack/Lansley) / I To avoid Piachaud’s criticism that in Townsend’s index many indicators reflect tastes rather than deprivation, M&L introduced the concept of “enforced lack” (EL), identifying deprivation only when a given lack is due to a declared inability to pay. This way of proceeding assumes that restriction in current income is the only possible source of deprivation. It begs the question on the sources of well-being. As this work was the point of departure for a whole generation of combined methods (the truly poor), this fact generated a “birth mark” in all of them, reproducing this bias.

(ELSPN) (Mack/Lansley) / II Definition of necessities is based on majority perceptions. The poverty criterion (quite arbitrary and empirically selected on the basis of observed correlation with income) is that 3 or + EL (from a list of 26 SPN) constitutes poverty. By adopting dichotomic indicators and not calculating an overall index for every HH, the poverty gap I cannot be properly calculated, nor can the more elaborated poverty aggregated measures. It shares with UBNOV the very damaging feature that poverty incidence (H) becomes a positive function of the # of items considered. Every time one adds a new item poverty raises unless the poverty criterion is modified, but then on what basis and with what comparability?

(ELSPN) (Mack/Lansley) / II Definition of necessities is based on majority perceptions. The poverty criterion (quite arbitrary and empirically selected on the basis of observed correlation with income) is that 3 or + EL (from a list of 26 SPN) constitutes poverty. By adopting dichotomic indicators and not calculating an overall index for every HH, the poverty gap I cannot be properly calculated, nor can the more elaborated poverty aggregated measures. It shares with UBNOV the very damaging feature that poverty incidence (H) becomes a positive function of the # of items considered. Every time one adds a new item poverty raises unless the poverty criterion is modified, but then on what basis and with what comparability?

Note • As announced, I will skip slides 37 and 38

Note • As announced, I will skip slides 37 and 38

Objective Poverty Line (Townsend, Gordon) Townsend uses his deprivation index to reveal the “objective PL”. He adjusted two straight lines to a scatter diagram depicting deprivation indices and current income of his surveyed HH. The objective PL is revealed where deprivation starts growing faster per unit of decrease in income. It is a combined method in a very special sense. Poverty is measured only by income, but the PL is identified using observed association between income and deprivation. Townsend & Gordon did a similar exercise using discriminatory analysis to identify the PL. It is the search “for the Holly Grail” (Piachaud): an objective PL which avoids value judgments.

Objective Poverty Line (Townsend, Gordon) Townsend uses his deprivation index to reveal the “objective PL”. He adjusted two straight lines to a scatter diagram depicting deprivation indices and current income of his surveyed HH. The objective PL is revealed where deprivation starts growing faster per unit of decrease in income. It is a combined method in a very special sense. Poverty is measured only by income, but the PL is identified using observed association between income and deprivation. Townsend & Gordon did a similar exercise using discriminatory analysis to identify the PL. It is the search “for the Holly Grail” (Piachaud): an objective PL which avoids value judgments.

Revealed or Objective UBN Thresholds This method as applied by Progresa/ Oportunidades divides the population into 2 groups on the base of an extreme PL = to the cost of a food basket assuming HH can spend 100% of their income on raw food, and then correct the initial grouping on the bases of discriminatory analysis. For each of the preliminary groups of poor and non-poor a new one-dimensional variable Z is calculated, which is a weighted average of the selected variables, the weights being determined internally by the model to maximise the distance between the means of the poor ZP from that of the non-poor, ZNP. These means are multivariate centroids that typify the profile of the two groups of families. A family is classified in the group with regard to whose centroid it bears less distance. This procedure is the mirror image of the Townnsend-Gordon one. The way Progresa/Oportunidades applies discriminatory analysis (using only one PL instead of a set of them) minimizes extreme poverty.

Revealed or Objective UBN Thresholds This method as applied by Progresa/ Oportunidades divides the population into 2 groups on the base of an extreme PL = to the cost of a food basket assuming HH can spend 100% of their income on raw food, and then correct the initial grouping on the bases of discriminatory analysis. For each of the preliminary groups of poor and non-poor a new one-dimensional variable Z is calculated, which is a weighted average of the selected variables, the weights being determined internally by the model to maximise the distance between the means of the poor ZP from that of the non-poor, ZNP. These means are multivariate centroids that typify the profile of the two groups of families. A family is classified in the group with regard to whose centroid it bears less distance. This procedure is the mirror image of the Townnsend-Gordon one. The way Progresa/Oportunidades applies discriminatory analysis (using only one PL instead of a set of them) minimizes extreme poverty.

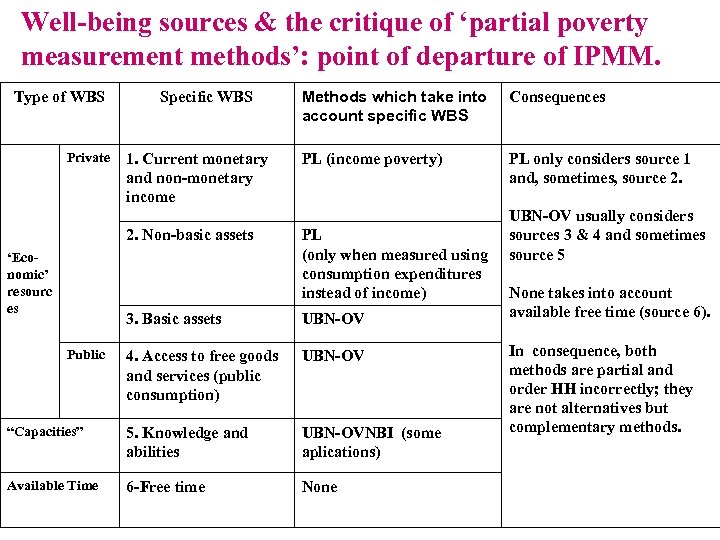

Well-being sources & the critique of ‘partial poverty measurement methods’: point of departure of IPMM. Type of WBS Private Specific WBS 1. Current monetary and non-monetary income 2. Non-basic assets ‘Economic’ resourc es Methods which take into account specific WBS Consequences PL (income poverty) PL only considers source 1 and, sometimes, source 2. PL (only when measured using consumption expenditures instead of income) 3. Basic assets UBN-OV 4. Access to free goods and services (public consumption) UBN-OV “Capacities” 5. Knowledge and abilities UBN-OVNBI (some aplications) Available Time 6 -Free time None Public UBN-OV usually considers sources 3 & 4 and sometimes source 5 None takes into account available free time (source 6). In consequence, both methods are partial and order HH incorrectly; they are not alternatives but complementary methods.

Well-being sources & the critique of ‘partial poverty measurement methods’: point of departure of IPMM. Type of WBS Private Specific WBS 1. Current monetary and non-monetary income 2. Non-basic assets ‘Economic’ resourc es Methods which take into account specific WBS Consequences PL (income poverty) PL only considers source 1 and, sometimes, source 2. PL (only when measured using consumption expenditures instead of income) 3. Basic assets UBN-OV 4. Access to free goods and services (public consumption) UBN-OV “Capacities” 5. Knowledge and abilities UBN-OVNBI (some aplications) Available Time 6 -Free time None Public UBN-OV usually considers sources 3 & 4 and sometimes source 5 None takes into account available free time (source 6). In consequence, both methods are partial and order HH incorrectly; they are not alternatives but complementary methods.

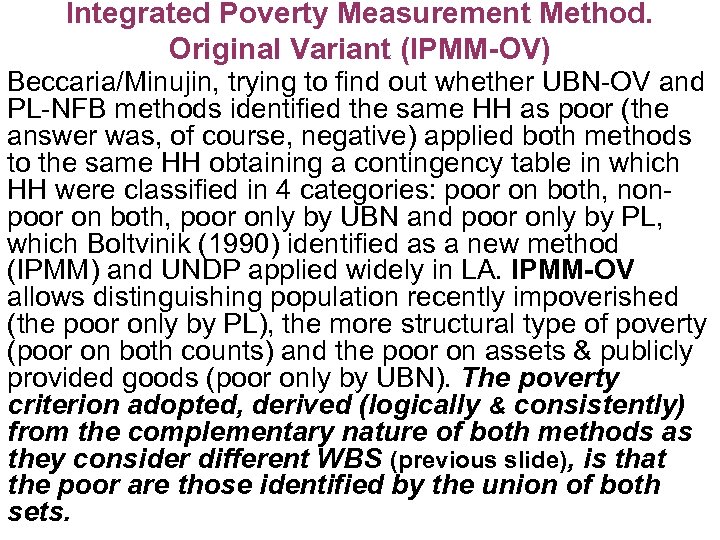

Integrated Poverty Measurement Method. Original Variant (IPMM-OV) Beccaria/Minujin, trying to find out whether UBN-OV and PL-NFB methods identified the same HH as poor (the answer was, of course, negative) applied both methods to the same HH obtaining a contingency table in which HH were classified in 4 categories: poor on both, nonpoor on both, poor only by UBN and poor only by PL, which Boltvinik (1990) identified as a new method (IPMM) and UNDP applied widely in LA. IPMM-OV allows distinguishing population recently impoverished (the poor only by PL), the more structural type of poverty (poor on both counts) and the poor on assets & publicly provided goods (poor only by UBN). The poverty criterion adopted, derived (logically & consistently) from the complementary nature of both methods as they consider different WBS (previous slide), is that the poor are those identified by the union of both sets.

Integrated Poverty Measurement Method. Original Variant (IPMM-OV) Beccaria/Minujin, trying to find out whether UBN-OV and PL-NFB methods identified the same HH as poor (the answer was, of course, negative) applied both methods to the same HH obtaining a contingency table in which HH were classified in 4 categories: poor on both, nonpoor on both, poor only by UBN and poor only by PL, which Boltvinik (1990) identified as a new method (IPMM) and UNDP applied widely in LA. IPMM-OV allows distinguishing population recently impoverished (the poor only by PL), the more structural type of poverty (poor on both counts) and the poor on assets & publicly provided goods (poor only by UBN). The poverty criterion adopted, derived (logically & consistently) from the complementary nature of both methods as they consider different WBS (previous slide), is that the poor are those identified by the union of both sets.

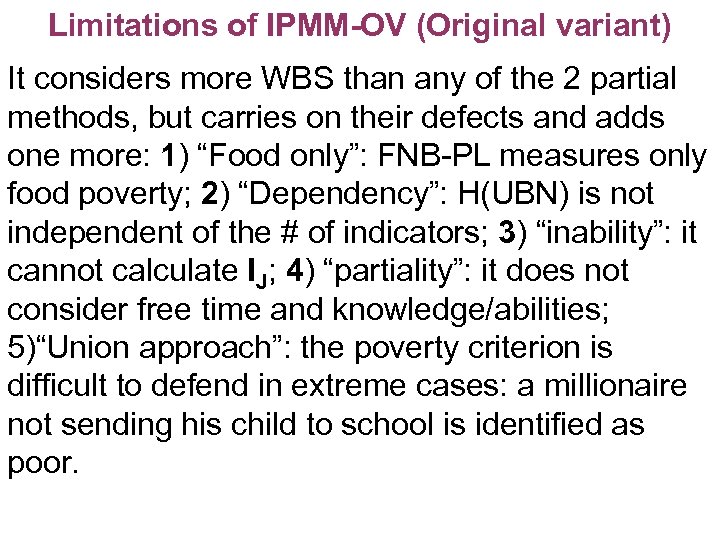

Limitations of IPMM-OV (Original variant) It considers more WBS than any of the 2 partial methods, but carries on their defects and adds one more: 1) “Food only”: FNB-PL measures only food poverty; 2) “Dependency”: H(UBN) is not independent of the # of indicators; 3) “inability”: it cannot calculate IJ; 4) “partiality”: it does not consider free time and knowledge/abilities; 5)“Union approach”: the poverty criterion is difficult to defend in extreme cases: a millionaire not sending his child to school is identified as poor.

Limitations of IPMM-OV (Original variant) It considers more WBS than any of the 2 partial methods, but carries on their defects and adds one more: 1) “Food only”: FNB-PL measures only food poverty; 2) “Dependency”: H(UBN) is not independent of the # of indicators; 3) “inability”: it cannot calculate IJ; 4) “partiality”: it does not consider free time and knowledge/abilities; 5)“Union approach”: the poverty criterion is difficult to defend in extreme cases: a millionaire not sending his child to school is identified as poor.

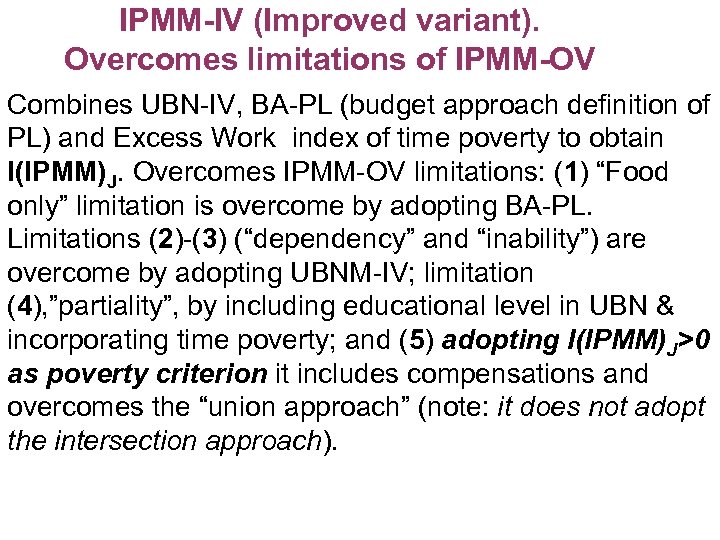

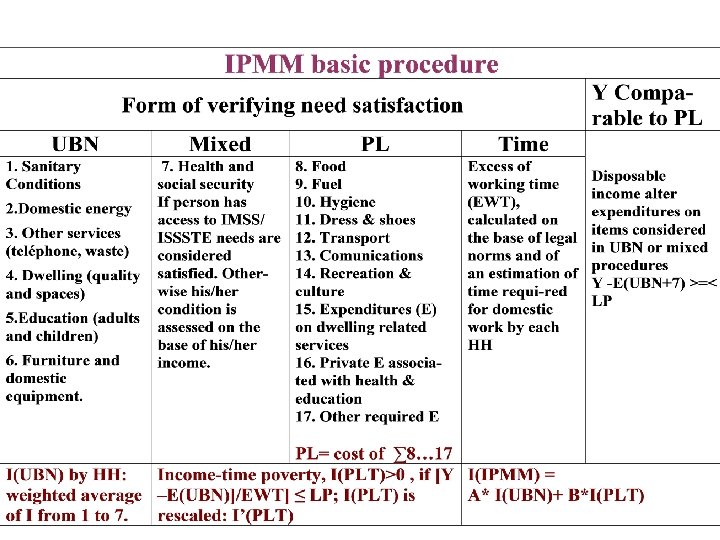

IPMM-IV (Improved variant). Overcomes limitations of IPMM-OV Combines UBN-IV, BA-PL (budget approach definition of PL) and Excess Work index of time poverty to obtain I(IPMM)J. Overcomes IPMM-OV limitations: (1) “Food only” limitation is overcome by adopting BA-PL. Limitations (2)-(3) (“dependency” and “inability”) are overcome by adopting UBNM-IV; limitation (4), ”partiality”, by including educational level in UBN & incorporating time poverty; and (5) adopting I(IPMM)J>0 as poverty criterion it includes compensations and overcomes the “union approach” (note: it does not adopt the intersection approach).

IPMM-IV (Improved variant). Overcomes limitations of IPMM-OV Combines UBN-IV, BA-PL (budget approach definition of PL) and Excess Work index of time poverty to obtain I(IPMM)J. Overcomes IPMM-OV limitations: (1) “Food only” limitation is overcome by adopting BA-PL. Limitations (2)-(3) (“dependency” and “inability”) are overcome by adopting UBNM-IV; limitation (4), ”partiality”, by including educational level in UBN & incorporating time poverty; and (5) adopting I(IPMM)J>0 as poverty criterion it includes compensations and overcomes the “union approach” (note: it does not adopt the intersection approach).

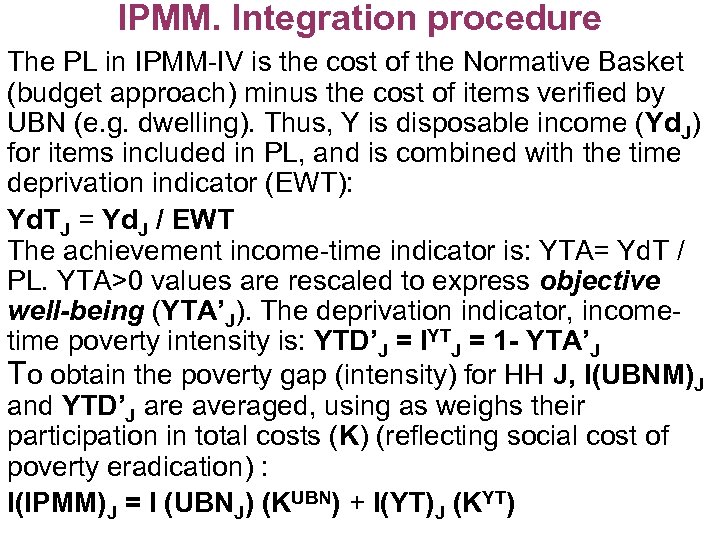

IPMM. Integration procedure The PL in IPMM-IV is the cost of the Normative Basket (budget approach) minus the cost of items verified by UBN (e. g. dwelling). Thus, Y is disposable income (Yd. J) for items included in PL, and is combined with the time deprivation indicator (EWT): Yd. TJ = Yd. J / EWT The achievement income-time indicator is: YTA= Yd. T / PL. YTA>0 values are rescaled to express objective well-being (YTA’J). The deprivation indicator, incometime poverty intensity is: YTD’J = IYTJ = 1 - YTA’J To obtain the poverty gap (intensity) for HH J, I(UBNM)J and YTD’J are averaged, using as weighs their participation in total costs (K) (reflecting social cost of poverty eradication) : I(IPMM)J = I (UBNJ) (KUBN) + I(YT)J (KYT)

IPMM. Integration procedure The PL in IPMM-IV is the cost of the Normative Basket (budget approach) minus the cost of items verified by UBN (e. g. dwelling). Thus, Y is disposable income (Yd. J) for items included in PL, and is combined with the time deprivation indicator (EWT): Yd. TJ = Yd. J / EWT The achievement income-time indicator is: YTA= Yd. T / PL. YTA>0 values are rescaled to express objective well-being (YTA’J). The deprivation indicator, incometime poverty intensity is: YTD’J = IYTJ = 1 - YTA’J To obtain the poverty gap (intensity) for HH J, I(UBNM)J and YTD’J are averaged, using as weighs their participation in total costs (K) (reflecting social cost of poverty eradication) : I(IPMM)J = I (UBNJ) (KUBN) + I(YT)J (KYT)

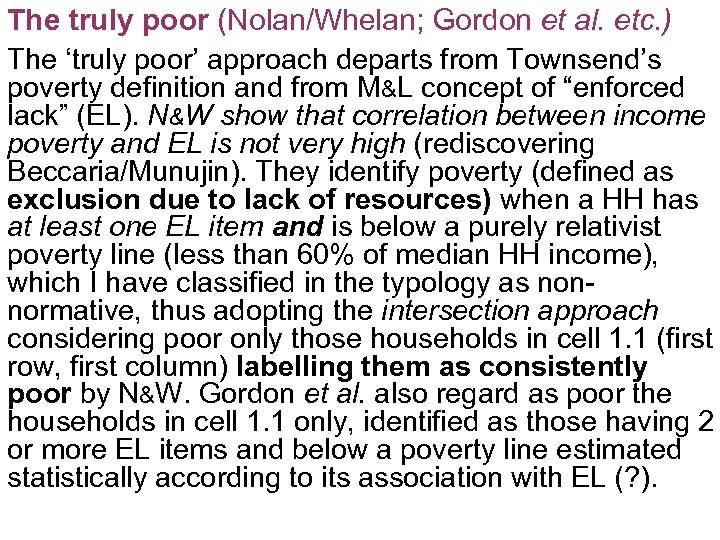

The truly poor (Nolan/Whelan; Gordon et al. etc. ) The ‘truly poor’ approach departs from Townsend’s poverty definition and from M&L concept of “enforced lack” (EL). N&W show that correlation between income poverty and EL is not very high (rediscovering Beccaria/Munujin). They identify poverty (defined as exclusion due to lack of resources) when a HH has at least one EL item and is below a purely relativist poverty line (less than 60% of median HH income), which I have classified in the typology as nonnormative, thus adopting the intersection approach considering poor only those households in cell 1. 1 (first row, first column) labelling them as consistently poor by N&W. Gordon et al. also regard as poor the households in cell 1. 1 only, identified as those having 2 or more EL items and below a poverty line estimated statistically according to its association with EL (? ).

The truly poor (Nolan/Whelan; Gordon et al. etc. ) The ‘truly poor’ approach departs from Townsend’s poverty definition and from M&L concept of “enforced lack” (EL). N&W show that correlation between income poverty and EL is not very high (rediscovering Beccaria/Munujin). They identify poverty (defined as exclusion due to lack of resources) when a HH has at least one EL item and is below a purely relativist poverty line (less than 60% of median HH income), which I have classified in the typology as nonnormative, thus adopting the intersection approach considering poor only those households in cell 1. 1 (first row, first column) labelling them as consistently poor by N&W. Gordon et al. also regard as poor the households in cell 1. 1 only, identified as those having 2 or more EL items and below a poverty line estimated statistically according to its association with EL (? ).

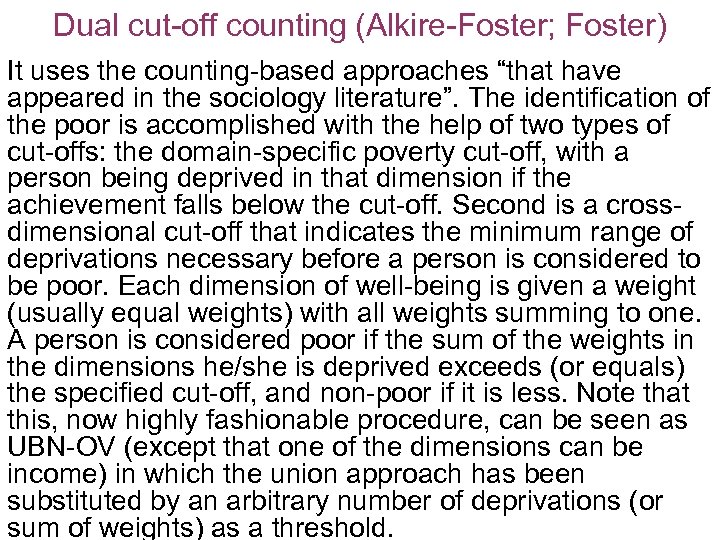

Dual cut-off counting (Alkire-Foster; Foster) It uses the counting-based approaches “that have appeared in the sociology literature”. The identification of the poor is accomplished with the help of two types of cut-offs: the domain-specific poverty cut-off, with a person being deprived in that dimension if the achievement falls below the cut-off. Second is a crossdimensional cut-off that indicates the minimum range of deprivations necessary before a person is considered to be poor. Each dimension of well-being is given a weight (usually equal weights) with all weights summing to one. A person is considered poor if the sum of the weights in the dimensions he/she is deprived exceeds (or equals) the specified cut-off, and non-poor if it is less. Note that this, now highly fashionable procedure, can be seen as UBN-OV (except that one of the dimensions can be income) in which the union approach has been substituted by an arbitrary number of deprivations (or sum of weights) as a threshold.

Dual cut-off counting (Alkire-Foster; Foster) It uses the counting-based approaches “that have appeared in the sociology literature”. The identification of the poor is accomplished with the help of two types of cut-offs: the domain-specific poverty cut-off, with a person being deprived in that dimension if the achievement falls below the cut-off. Second is a crossdimensional cut-off that indicates the minimum range of deprivations necessary before a person is considered to be poor. Each dimension of well-being is given a weight (usually equal weights) with all weights summing to one. A person is considered poor if the sum of the weights in the dimensions he/she is deprived exceeds (or equals) the specified cut-off, and non-poor if it is less. Note that this, now highly fashionable procedure, can be seen as UBN-OV (except that one of the dimensions can be income) in which the union approach has been substituted by an arbitrary number of deprivations (or sum of weights) as a threshold.

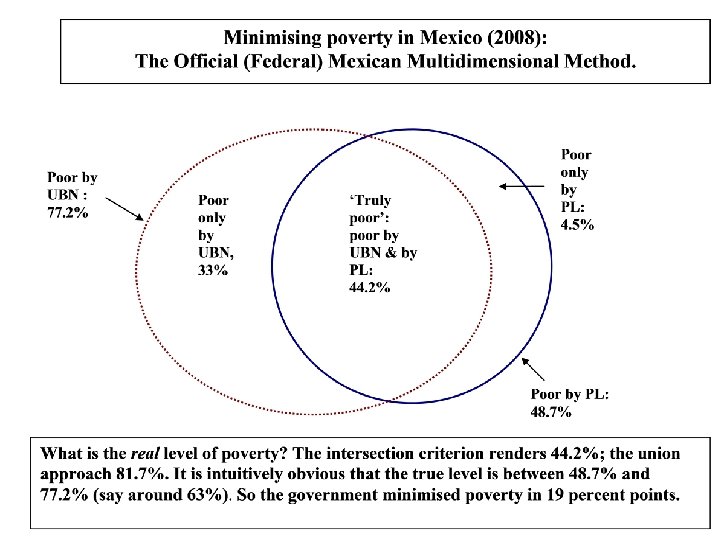

Modified truly poor (Coneval, Mexico) By law, poverty measurement in Mexico has to be multidimensional (the law specifies 7 dimensions) and has to be carried out by a semi-independent agency, Coneval. The official method announced by Coneval is a variant of the intersection approach or truly poor, thus underestimating poverty: in order to be considered poor a HH has to be both below the PL (defined by a quasi budget approach) & deprived in 1 or more (of a total of six) UBN dimensions. But within UBN the method adopts a union approach, in which only 1 deprivation is enough to be considered ‘vulnerable’, overestimating ‘vulnerability’. To compensate for this, UBN thresholds are set at a very low level indeed. Population in cells 1. 2 & 2. 1 are considered vulnerable (but not poor) thus creating a dual calculation of disadvantage: poverty and poverty + vulnerability (next slide)

Modified truly poor (Coneval, Mexico) By law, poverty measurement in Mexico has to be multidimensional (the law specifies 7 dimensions) and has to be carried out by a semi-independent agency, Coneval. The official method announced by Coneval is a variant of the intersection approach or truly poor, thus underestimating poverty: in order to be considered poor a HH has to be both below the PL (defined by a quasi budget approach) & deprived in 1 or more (of a total of six) UBN dimensions. But within UBN the method adopts a union approach, in which only 1 deprivation is enough to be considered ‘vulnerable’, overestimating ‘vulnerability’. To compensate for this, UBN thresholds are set at a very low level indeed. Population in cells 1. 2 & 2. 1 are considered vulnerable (but not poor) thus creating a dual calculation of disadvantage: poverty and poverty + vulnerability (next slide)