15b40dc6093df4a06a18a9ee952c051c.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 71

MT 311 (Oct 2007) Java Application Development Tutorial 7 Control Structures, Subprograms and Its Implementation

MT 311 (Oct 2007) Java Application Development Tutorial 7 Control Structures, Subprograms and Its Implementation

Tutor Information 2 Edmund Chiu (Group 2) Email: t 439934@ouhk. edu. hk Please begin your email subject with [MT 311] Webpage: http: //www. geocities. com/gianted

Tutor Information 2 Edmund Chiu (Group 2) Email: t 439934@ouhk. edu. hk Please begin your email subject with [MT 311] Webpage: http: //www. geocities. com/gianted

Part I Control Structures

Part I Control Structures

Compound Statements A compound statement is a collection of statements that can be used in a place where a single statement is allowed – – – In Pascal, a compound statement is marked at the two ends by the keyword begin and end In Java, C/C++, a compound statement is marked at the two ends by { and } Variables can be declared in a compound statement in some languages – this kind of compound statement is called block 4 Compound statements in C are blocks but not in Pascal

Compound Statements A compound statement is a collection of statements that can be used in a place where a single statement is allowed – – – In Pascal, a compound statement is marked at the two ends by the keyword begin and end In Java, C/C++, a compound statement is marked at the two ends by { and } Variables can be declared in a compound statement in some languages – this kind of compound statement is called block 4 Compound statements in C are blocks but not in Pascal

Advantages and Disadvantages of Variable Declaration in a Block 5 A variable can be declared close to where it is used The variable is not visible outside the block where it should not be used However, if a number of variables are declared with same name on different levels in nested blocks will greatly decrease the readability of the program as it is difficult to find the true identity of these variables

Advantages and Disadvantages of Variable Declaration in a Block 5 A variable can be declared close to where it is used The variable is not visible outside the block where it should not be used However, if a number of variables are declared with same name on different levels in nested blocks will greatly decrease the readability of the program as it is difficult to find the true identity of these variables

Two-Way Selection Statements Two-way selection statements provides two execution paths in a program It will be ambiguous in the case of nested if statement – – – 6 In Pascal and C, an else clause is always paired with the most recent unpaired then clause In Algol 60, a compound statement must be used to enclose an if statement nested inside a then clause In Algol 68, Fortran 77 and Ada, special marker such as endif will mark the end of an if statement In terms of readability, if-then-else-endif statements are much more readable than if-else statements used in C

Two-Way Selection Statements Two-way selection statements provides two execution paths in a program It will be ambiguous in the case of nested if statement – – – 6 In Pascal and C, an else clause is always paired with the most recent unpaired then clause In Algol 60, a compound statement must be used to enclose an if statement nested inside a then clause In Algol 68, Fortran 77 and Ada, special marker such as endif will mark the end of an if statement In terms of readability, if-then-else-endif statements are much more readable than if-else statements used in C

Multiple Selection Statements If-then-elseif-endif statements are useful because it would enable the statement to be limited to one level Switch-case is another construct for multiple selectors The writability of switch-case increases if – – Reliability is increased by: – – 7 Sub-ranges can be specified in the case clause OR is allowed in the case clause Enforce checking on the case lists are exhaustive Prohibit the control to go from a case to another

Multiple Selection Statements If-then-elseif-endif statements are useful because it would enable the statement to be limited to one level Switch-case is another construct for multiple selectors The writability of switch-case increases if – – Reliability is increased by: – – 7 Sub-ranges can be specified in the case clause OR is allowed in the case clause Enforce checking on the case lists are exhaustive Prohibit the control to go from a case to another

Iterative Statements – Counter Control Loops For loops in C and Pascal are examples of countercontrolled loops Design issues: – Explicitly change the value of a loop variable – Use of a usual variable as the loop variable 8 Ada does not allow the loop variable to be assigned explicitly increase reliability because no mistaken change to loop variable can be made If change to the variable is needed, we should use a while loop instead In Ada, the declaration is integrated into the loop statement and the variable is only available in the loop In C and Java, the loop variable is declared as other variables – there is no guarantee the loop variable will not be used by other subprogram

Iterative Statements – Counter Control Loops For loops in C and Pascal are examples of countercontrolled loops Design issues: – Explicitly change the value of a loop variable – Use of a usual variable as the loop variable 8 Ada does not allow the loop variable to be assigned explicitly increase reliability because no mistaken change to loop variable can be made If change to the variable is needed, we should use a while loop instead In Ada, the declaration is integrated into the loop statement and the variable is only available in the loop In C and Java, the loop variable is declared as other variables – there is no guarantee the loop variable will not be used by other subprogram

Counter Control Loops (cont’d) – Value change flexibility of a loop variable – The possibility of exiting from the middle of a loop 9 In Ada and Pascal, we can only increment/decrement the value of the loop variables by a constant amount In C/C++, the value can be changed using any statements It is very efficient if only increment and decrement of fixed amount is allowed – loop variable and increment amount are stored in registers It also decrease the occurrence of an infinite loop Pascal and Fortran do not allow such exit except using goto Ada and C allows exit using exit and break respectively – which directs the flow to the statement after the loop – it is more readable C also provides the continue construct to skip the rest of statements in one iteration

Counter Control Loops (cont’d) – Value change flexibility of a loop variable – The possibility of exiting from the middle of a loop 9 In Ada and Pascal, we can only increment/decrement the value of the loop variables by a constant amount In C/C++, the value can be changed using any statements It is very efficient if only increment and decrement of fixed amount is allowed – loop variable and increment amount are stored in registers It also decrease the occurrence of an infinite loop Pascal and Fortran do not allow such exit except using goto Ada and C allows exit using exit and break respectively – which directs the flow to the statement after the loop – it is more readable C also provides the continue construct to skip the rest of statements in one iteration

Counter Control Loops (cont’d) – Are the values of loop variable evaluated once for every iteration In C, the condition specifying whether the loop should terminate is evaluated before every iteration – value of loop variable may not be evaluated in the final iteration However, it is not advisable to specify the condition so that the value of the loop variable changes after each iteration This would make the loop very difficult to read and check – It is more likely that the loop will not terminate – 10

Counter Control Loops (cont’d) – Are the values of loop variable evaluated once for every iteration In C, the condition specifying whether the loop should terminate is evaluated before every iteration – value of loop variable may not be evaluated in the final iteration However, it is not advisable to specify the condition so that the value of the loop variable changes after each iteration This would make the loop very difficult to read and check – It is more likely that the loop will not terminate – 10

Logically Controlled Loops Logically controlled loops use a Boolean expression to control the continuity of an iteration – – The condition will be tested every time either before or after an iteration depending on whether it is a pre-test or a post-test loop Exit or break construct increases the writability of the language Generally, a while loop is a more flexible way of iteration – – – 11 Pascal: while-do and repeat-until loops C: while and do-while loops However, a greater flexibility may mean it is more likely to become infinite looping Also, for loop usually generates a more efficient code In case of Ada, using a while loop will lose the reliability provided by the for loop (loop variable checking)

Logically Controlled Loops Logically controlled loops use a Boolean expression to control the continuity of an iteration – – The condition will be tested every time either before or after an iteration depending on whether it is a pre-test or a post-test loop Exit or break construct increases the writability of the language Generally, a while loop is a more flexible way of iteration – – – 11 Pascal: while-do and repeat-until loops C: while and do-while loops However, a greater flexibility may mean it is more likely to become infinite looping Also, for loop usually generates a more efficient code In case of Ada, using a while loop will lose the reliability provided by the for loop (loop variable checking)

Unconditional Branching Goto statement (unconditional branching) is a dangerous construct – Goto makes programs virtually unreadable and unreliable So, why does the languages still include goto? – – It provides a way to exit from a number of deeply nested loops or procedure calls When there is an exception inside a deep call, we can also use goto to force the program to restart 12 It can be done more appropriately by using exception handling provided in Java, C++ and Ada.

Unconditional Branching Goto statement (unconditional branching) is a dangerous construct – Goto makes programs virtually unreadable and unreliable So, why does the languages still include goto? – – It provides a way to exit from a number of deeply nested loops or procedure calls When there is an exception inside a deep call, we can also use goto to force the program to restart 12 It can be done more appropriately by using exception handling provided in Java, C++ and Ada.

Part II Subprograms

Part II Subprograms

Subprograms General characteristics – – – Parts in a subprogram – – – 14 single entry point calling unit is suspended during the execution of the called subprogram control always returns to the caller after the subprogram terminates Definition – the interface to the subprogram Header – specifies the name, return type and the parameter list for a subprogram Prototype – function declarations that comes before the definition, just like the case in variables (used in C and C++)

Subprograms General characteristics – – – Parts in a subprogram – – – 14 single entry point calling unit is suspended during the execution of the called subprogram control always returns to the caller after the subprogram terminates Definition – the interface to the subprogram Header – specifies the name, return type and the parameter list for a subprogram Prototype – function declarations that comes before the definition, just like the case in variables (used in C and C++)

Non-local Variables vs. Parameters in Subprograms Subprogram gains access to data through – – Accessing non-local variables is unreliable – – 15 direct access to non-local variables parameter passing If recursion is allowed, there may be a number of active instances in the same subprogram at any time However, the same non-local variables are used each time That means such information may be tampered with by other instances of the subprogram and therefore may have been changed unintentionally Even not in a case of recursion, we may not want the non-local variable to be tampered with by the subprogram

Non-local Variables vs. Parameters in Subprograms Subprogram gains access to data through – – Accessing non-local variables is unreliable – – 15 direct access to non-local variables parameter passing If recursion is allowed, there may be a number of active instances in the same subprogram at any time However, the same non-local variables are used each time That means such information may be tampered with by other instances of the subprogram and therefore may have been changed unintentionally Even not in a case of recursion, we may not want the non-local variable to be tampered with by the subprogram

Parameters in Subprograms The parameters in the subprogram header are called formal parameters – 16 They are bound to other variables when the subprogram is called A subprogram call will include a list of parameters to the formal parameters. These parameters are called actual parameters

Parameters in Subprograms The parameters in the subprogram header are called formal parameters – 16 They are bound to other variables when the subprogram is called A subprogram call will include a list of parameters to the formal parameters. These parameters are called actual parameters

Parameters Binding Nearly all languages bound the parameters by simple position When the list becomes too long, some languages provides keyword parameters – – Some languages can also have default values for the formal parameters – – – 17 Example: Sumer(Length => L, List => A, Sum => S); Sumer has the formal parameters Length, List and Sum order of the parameters is not important – In C++, you can even skip omit the last parameters with default values in subprogram calls Example: Given the following function header: float pay(float income, float tax_rate, int exemptions=1) You can make this call: pay(20000. 0, 0. 15); However, this design is prone to error though convenient Other example for variable number of parameter: printf

Parameters Binding Nearly all languages bound the parameters by simple position When the list becomes too long, some languages provides keyword parameters – – Some languages can also have default values for the formal parameters – – – 17 Example: Sumer(Length => L, List => A, Sum => S); Sumer has the formal parameters Length, List and Sum order of the parameters is not important – In C++, you can even skip omit the last parameters with default values in subprogram calls Example: Given the following function header: float pay(float income, float tax_rate, int exemptions=1) You can make this call: pay(20000. 0, 0. 15); However, this design is prone to error though convenient Other example for variable number of parameter: printf

Design issues for Subprograms 18 Parameter-passing methods Type checking for the parameters Local variables - statically/dynamically allocated? Subprogram definition in other subprogram Referencing environment in nested subprograms Overloading Generic Subprograms

Design issues for Subprograms 18 Parameter-passing methods Type checking for the parameters Local variables - statically/dynamically allocated? Subprogram definition in other subprogram Referencing environment in nested subprograms Overloading Generic Subprograms

Local Referencing Environments Local variables in a subprogram are actually implemented as static or stack dynamic variables Advantages of using stack dynamic variables – – Disadvantages of using stack dynamic locals – – 19 Flexibility – recursive subprogram must have stack-dynamic local variables Storage for local variables in active subprogram can be shared with those in all inactive subprograms Cost of time to allocate, initialize and de-allocate the variables in each activation Access to local variables is indirect (only known at execution) and slower Subprograms cannot retain data variables between calls. This cause a problem if static variables is not allowed within the subprogram – global variables are needed to store these values and that decrease the reliability because they may be mistakenly assigned a value in other parts of the program

Local Referencing Environments Local variables in a subprogram are actually implemented as static or stack dynamic variables Advantages of using stack dynamic variables – – Disadvantages of using stack dynamic locals – – 19 Flexibility – recursive subprogram must have stack-dynamic local variables Storage for local variables in active subprogram can be shared with those in all inactive subprograms Cost of time to allocate, initialize and de-allocate the variables in each activation Access to local variables is indirect (only known at execution) and slower Subprograms cannot retain data variables between calls. This cause a problem if static variables is not allowed within the subprogram – global variables are needed to store these values and that decrease the reliability because they may be mistakenly assigned a value in other parts of the program

Parameter Passing Methods A formal parameter can: – – – Two conceptual models of how data transfers – – Either an actual value is copied Or an access path (a simple pointer or reference) is transmitted Four implementation models of parameter passing – – – 20 receive data from the actual parameter (in mode) transmit data to the actual parameter (out mode) do both (inout mode) – Pass-by-value Pass-by-result Pass-by-value-result Pass-by-reference

Parameter Passing Methods A formal parameter can: – – – Two conceptual models of how data transfers – – Either an actual value is copied Or an access path (a simple pointer or reference) is transmitted Four implementation models of parameter passing – – – 20 receive data from the actual parameter (in mode) transmit data to the actual parameter (out mode) do both (inout mode) – Pass-by-value Pass-by-result Pass-by-value-result Pass-by-reference

Pass-by-Value Implementing in-mode semantics Additional storage is allocated for the formal parameters from the stack The values in the actual parameters are copied to the storage allocated Advantages – – – 21 The original value would not be changed after returning from the function (Beware of parameter with pointers! Contents can actually be changed!!) Referencing a value parameter is as efficient as referencing a local variable Actual parameters can be variables, constants or expressions Disadvantages – Storage and copy operations can be costly if the parameter is large (e. g. arrays with many elements)

Pass-by-Value Implementing in-mode semantics Additional storage is allocated for the formal parameters from the stack The values in the actual parameters are copied to the storage allocated Advantages – – – 21 The original value would not be changed after returning from the function (Beware of parameter with pointers! Contents can actually be changed!!) Referencing a value parameter is as efficient as referencing a local variable Actual parameters can be variables, constants or expressions Disadvantages – Storage and copy operations can be costly if the parameter is large (e. g. arrays with many elements)

Pass-by-Result Implementing out-mode semantics – no values is transmitted to the subprogram Similar to pass-by-value, extra storage is allocated for the formal parameters Values are copied from the formal parameters to the actual parameters when the subprogram returns – – – 22 Actual parameters must be variables Problem occurs if the same variable is present twice or more in the actual parameter list in a single subprogram call – as we do not know which value will be assigned first Similar to pass-by-value, the method can be very inefficient if the parameter is very large

Pass-by-Result Implementing out-mode semantics – no values is transmitted to the subprogram Similar to pass-by-value, extra storage is allocated for the formal parameters Values are copied from the formal parameters to the actual parameters when the subprogram returns – – – 22 Actual parameters must be variables Problem occurs if the same variable is present twice or more in the actual parameter list in a single subprogram call – as we do not know which value will be assigned first Similar to pass-by-value, the method can be very inefficient if the parameter is very large

Pass-by-Value-Result 23 Combines pass-by-value and pass-by-result together for inout mode parameters Values of actual parameters are copied to the locally allocated storage of the formal parameters when the subprogram is called Values of formal parameters are transmitted back to the actual parameters at subprogram termination

Pass-by-Value-Result 23 Combines pass-by-value and pass-by-result together for inout mode parameters Values of actual parameters are copied to the locally allocated storage of the formal parameters when the subprogram is called Values of formal parameters are transmitted back to the actual parameters at subprogram termination

Pass-by-Reference Access path is transmitted to the subprogram for inout mode parameters. Actual parameters must be variables Advantages – – No extra storage and data copying is needed If actual size of a parameter is unknown at compile time, we need to use pass-by-reference Disadvantages – 24 Example: Consider an object of B (subclass of A) is passed as parameter that supposed to be an object of A. The size of the instances are different, the parameter value cannot be copied because of the different size – Actual value needed to be accessed indirectly – less efficient Alias problem may occur

Pass-by-Reference Access path is transmitted to the subprogram for inout mode parameters. Actual parameters must be variables Advantages – – No extra storage and data copying is needed If actual size of a parameter is unknown at compile time, we need to use pass-by-reference Disadvantages – 24 Example: Consider an object of B (subclass of A) is passed as parameter that supposed to be an object of A. The size of the instances are different, the parameter value cannot be copied because of the different size – Actual value needed to be accessed indirectly – less efficient Alias problem may occur

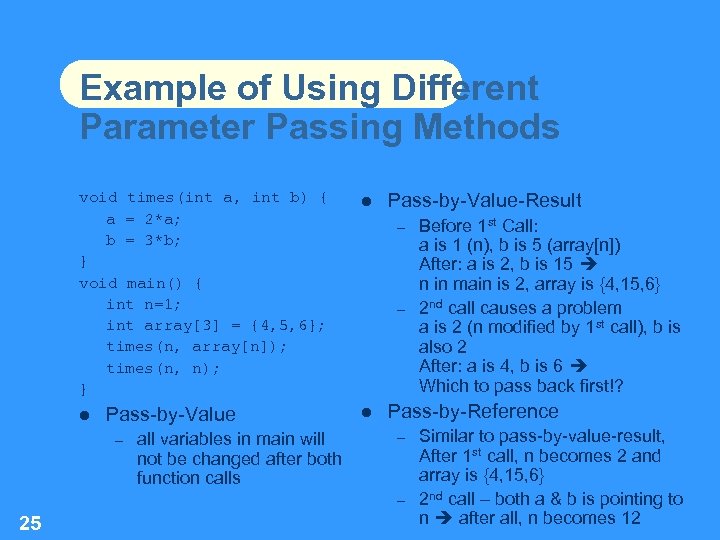

Example of Using Different Parameter Passing Methods void times(int a, int b) { a = 2*a; b = 3*b; } void main() { int n=1; int array[3] = {4, 5, 6}; times(n, array[n]); times(n, n); } Pass-by-Value – all variables in main will not be changed after both function calls Pass-by-Value-Result – – Pass-by-Reference – – 25 Before 1 st Call: a is 1 (n), b is 5 (array[n]) After: a is 2, b is 15 n in main is 2, array is {4, 15, 6} 2 nd call causes a problem a is 2 (n modified by 1 st call), b is also 2 After: a is 4, b is 6 Which to pass back first!? Similar to pass-by-value-result, After 1 st call, n becomes 2 and array is {4, 15, 6} 2 nd call – both a & b is pointing to n after all, n becomes 12

Example of Using Different Parameter Passing Methods void times(int a, int b) { a = 2*a; b = 3*b; } void main() { int n=1; int array[3] = {4, 5, 6}; times(n, array[n]); times(n, n); } Pass-by-Value – all variables in main will not be changed after both function calls Pass-by-Value-Result – – Pass-by-Reference – – 25 Before 1 st Call: a is 1 (n), b is 5 (array[n]) After: a is 2, b is 15 n in main is 2, array is {4, 15, 6} 2 nd call causes a problem a is 2 (n modified by 1 st call), b is also 2 After: a is 4, b is 6 Which to pass back first!? Similar to pass-by-value-result, After 1 st call, n becomes 2 and array is {4, 15, 6} 2 nd call – both a & b is pointing to n after all, n becomes 12

Passing Constant Reference as Parameter Sometime, a large size parameter may need to be passed into a method – – One way to do the task in C++ is to pass a constant reference: – – 26 Passing through copying wastes storage and time Passing through access path may change the content of the parameter – Example: void func(const rec 1 &r 1) r 1 is passed by reference (efficient) and cannot be changed Compiler will check no assignment statements will be appeared in the subprogram and if r 1 is used to call other methods, it should be passed by value or constant reference Also, only r 1's const method can be called

Passing Constant Reference as Parameter Sometime, a large size parameter may need to be passed into a method – – One way to do the task in C++ is to pass a constant reference: – – 26 Passing through copying wastes storage and time Passing through access path may change the content of the parameter – Example: void func(const rec 1 &r 1) r 1 is passed by reference (efficient) and cannot be changed Compiler will check no assignment statements will be appeared in the subprogram and if r 1 is used to call other methods, it should be passed by value or constant reference Also, only r 1's const method can be called

Implementing Parameter Passing Methods In most languages, parameter communications takes place through the runtime stack – – 27 Pass-by-value have their values copied into stack locations (storage for the formal parameter) Pass-by-result does the opposite – the values are placed in the stack and are retrieved by the calling program when the subprogram terminates Pass-by-value-result combines pass-by-value and pass-byresult. The stack location for the parameters is initialized by the call and is then used like a local variable in the called subprogram Pass-by-reference place the actual parameter address in the stack regardless of its data type. Reference to constants may leads to big problem if compiler does not prevent the careless change of contents.

Implementing Parameter Passing Methods In most languages, parameter communications takes place through the runtime stack – – 27 Pass-by-value have their values copied into stack locations (storage for the formal parameter) Pass-by-result does the opposite – the values are placed in the stack and are retrieved by the calling program when the subprogram terminates Pass-by-value-result combines pass-by-value and pass-byresult. The stack location for the parameters is initialized by the call and is then used like a local variable in the called subprogram Pass-by-reference place the actual parameter address in the stack regardless of its data type. Reference to constants may leads to big problem if compiler does not prevent the careless change of contents.

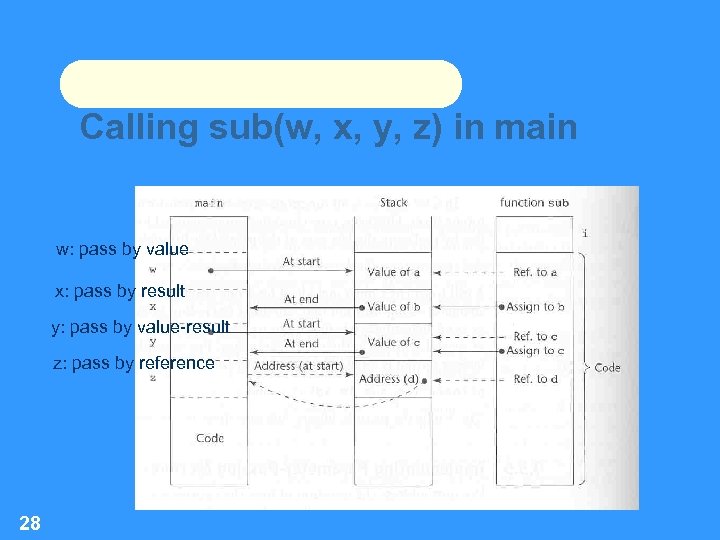

Calling sub(w, x, y, z) in main w: pass by value x: pass by result y: pass by value-result z: pass by reference 28

Calling sub(w, x, y, z) in main w: pass by value x: pass by result y: pass by value-result z: pass by reference 28

Overloaded Subprograms 29 Just like overloading operators, subprograms can also have a same name but operating on different data types. Any function call will be analyzed by the compiler and the compiler will invoke the correct function in accordance to the parameter list used in the call. To maintain readability, we should only overload subprograms when the subprograms having the same name are to perform similar tasks on data of different types

Overloaded Subprograms 29 Just like overloading operators, subprograms can also have a same name but operating on different data types. Any function call will be analyzed by the compiler and the compiler will invoke the correct function in accordance to the parameter list used in the call. To maintain readability, we should only overload subprograms when the subprograms having the same name are to perform similar tasks on data of different types

User-Defined Overloaded Operators In Ada and C++, programmers can overload the operators in the same way they overload the subprograms – – – 30 Example in C++ – dot product using * operator: int operator * (const vector &a, const vector &b, int len); Providing operator overloading makes some expressions much more readable However, if the operator is overloaded too much, the readability will decrease as there are too many meanings attached to the operator

User-Defined Overloaded Operators In Ada and C++, programmers can overload the operators in the same way they overload the subprograms – – – 30 Example in C++ – dot product using * operator: int operator * (const vector &a, const vector &b, int len); Providing operator overloading makes some expressions much more readable However, if the operator is overloaded too much, the readability will decrease as there are too many meanings attached to the operator

Generic Subprograms Assume we are writing a subprogram that sorts an array of unspecified element type – – 31 Writing overloaded subprograms may require us to write many different functions that do the totally same job Generic subprogram (in C++ & Ada) saves us from the trouble. Different versions of the array sorting function will be generated by the compiler once the generic function is ready. In C++, generic functions have the descriptive name of template functions

Generic Subprograms Assume we are writing a subprogram that sorts an array of unspecified element type – – 31 Writing overloaded subprograms may require us to write many different functions that do the totally same job Generic subprogram (in C++ & Ada) saves us from the trouble. Different versions of the array sorting function will be generated by the compiler once the generic function is ready. In C++, generic functions have the descriptive name of template functions

![Generic Sorting Subprogram in C++ 32 template <class Type> void sort(Type list[], int len) Generic Sorting Subprogram in C++ 32 template <class Type> void sort(Type list[], int len)](https://present5.com/presentation/15b40dc6093df4a06a18a9ee952c051c/image-32.jpg) Generic Sorting Subprogram in C++ 32 template

Generic Sorting Subprogram in C++ 32 template

Part III Implementing Subprograms

Part III Implementing Subprograms

Semantics of Calls and Returns Four issues for subprogram calls in addition to the transfer of control – – Four issues for subprogram returns in addition to the transfer of control – – 34 parameter passing allocation of storage to local variables provide the access to nonlocal variables (e. g. global) that are visible in the subprogram according to the scopes of the variables save the execution status of the calling unit parameter passing deallocation of storage used for local variables remove the access to nonlocal variables visible in the subprogram restore the execution status of the calling unit

Semantics of Calls and Returns Four issues for subprogram calls in addition to the transfer of control – – Four issues for subprogram returns in addition to the transfer of control – – 34 parameter passing allocation of storage to local variables provide the access to nonlocal variables (e. g. global) that are visible in the subprogram according to the scopes of the variables save the execution status of the calling unit parameter passing deallocation of storage used for local variables remove the access to nonlocal variables visible in the subprogram restore the execution status of the calling unit

Simple Non-Recursive Language In the following pages, we will model a language with the following characteristics – – – No recursion is allowed All non-local variables are global variables All local variables are statically allocated This simple subprogram consists of two separate parts: – – actual code, which is constant Local variables and data that can be changed throughout the program activation. It consists of 35 Caller status information Parameters Return address Functional value for function subprograms

Simple Non-Recursive Language In the following pages, we will model a language with the following characteristics – – – No recursion is allowed All non-local variables are global variables All local variables are statically allocated This simple subprogram consists of two separate parts: – – actual code, which is constant Local variables and data that can be changed throughout the program activation. It consists of 35 Caller status information Parameters Return address Functional value for function subprograms

Activation Record Instance (ARI) 36 The layout of the non-code part of a subprogram is called an activation record A concrete example of an activation record is called activation record instance (ARI), which is a collection of data in the form of an activation record In this example, as the program does not support recursion, there can be only one active version of a given subprogram at a time The following shows a possible layout for an activation record for a simple subprogram (caller status is omitted for simplicity):

Activation Record Instance (ARI) 36 The layout of the non-code part of a subprogram is called an activation record A concrete example of an activation record is called activation record instance (ARI), which is a collection of data in the form of an activation record In this example, as the program does not support recursion, there can be only one active version of a given subprogram at a time The following shows a possible layout for an activation record for a simple subprogram (caller status is omitted for simplicity):

Stack Content of a Program with Simple Subprograms The stack content shows a main program with three subprograms: A, B and C – – – 37 These program units may be compiled in different time The executable program is put together by a linker – which patch in the relative target addresses for all calls to main, A, B and C Whenever a subprogram is called, the return address (address of next statement) is stored to the return address of ARI Address of parameter will also be stored (assuming pass by reference). Whenever we need to access the parameter, we access through the stored address At the end of the subprogram, control will be passed to the address stored in the Return Address field

Stack Content of a Program with Simple Subprograms The stack content shows a main program with three subprograms: A, B and C – – – 37 These program units may be compiled in different time The executable program is put together by a linker – which patch in the relative target addresses for all calls to main, A, B and C Whenever a subprogram is called, the return address (address of next statement) is stored to the return address of ARI Address of parameter will also be stored (assuming pass by reference). Whenever we need to access the parameter, we access through the stored address At the end of the subprogram, control will be passed to the address stored in the Return Address field

Activation Record of Subprogram with Stack-Dynamic Local Variables With stack-dynamic local variables, the AR will be more complex because: – – Thus the activation record will need to have two more fields – – 38 The compiler must handle the allocation and deallocation of local variables Recursion adds the possibility of multiple instance of ARI exists at the same time Dynamic link stores the pointers to the top of ARI of the caller – used in destruction of current ARI when the procedure is completed. The pointer can only be known during runtime Static link shows stores the pointer to the bottom of its static parent. It will be known during the compile time

Activation Record of Subprogram with Stack-Dynamic Local Variables With stack-dynamic local variables, the AR will be more complex because: – – Thus the activation record will need to have two more fields – – 38 The compiler must handle the allocation and deallocation of local variables Recursion adds the possibility of multiple instance of ARI exists at the same time Dynamic link stores the pointers to the top of ARI of the caller – used in destruction of current ARI when the procedure is completed. The pointer can only be known during runtime Static link shows stores the pointer to the bottom of its static parent. It will be known during the compile time

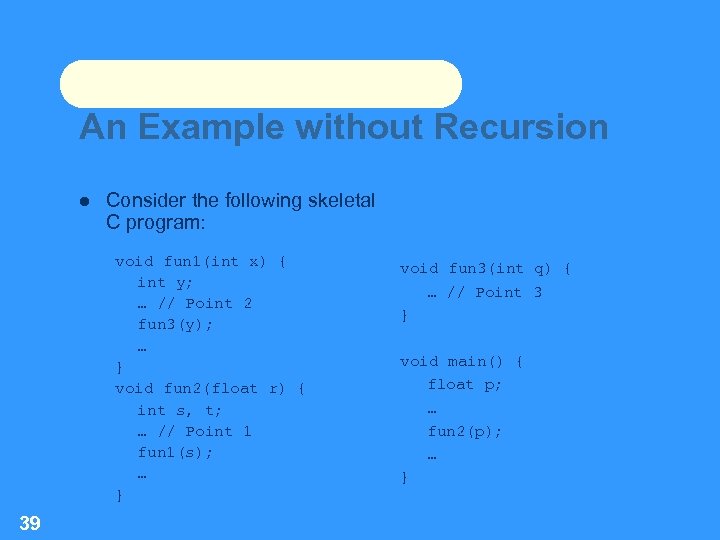

An Example without Recursion Consider the following skeletal C program: void fun 1(int x) { int y; … // Point 2 fun 3(y); … } void fun 2(float r) { int s, t; … // Point 1 fun 1(s); … } 39 void fun 3(int q) { … // Point 3 } void main() { float p; … fun 2(p); … }

An Example without Recursion Consider the following skeletal C program: void fun 1(int x) { int y; … // Point 2 fun 3(y); … } void fun 2(float r) { int s, t; … // Point 1 fun 1(s); … } 39 void fun 3(int q) { … // Point 3 } void main() { float p; … fun 2(p); … }

Stack Contents for the Sample Program 40 At point 1 At point 2

Stack Contents for the Sample Program 40 At point 1 At point 2

41 At Point 3

41 At Point 3

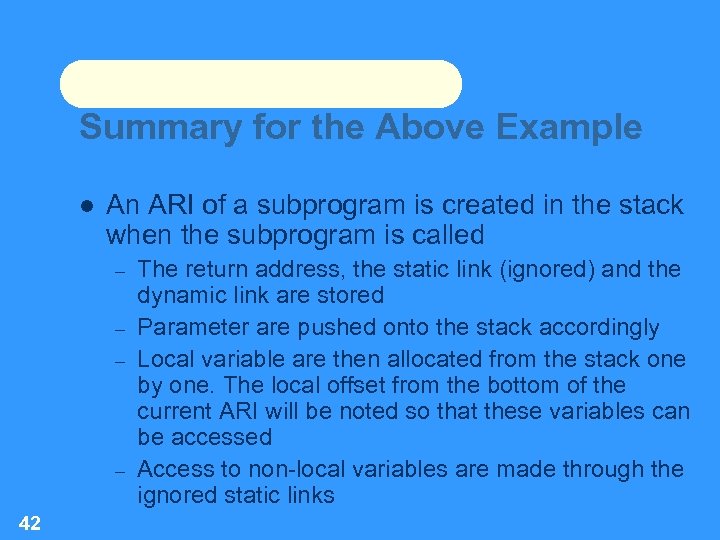

Summary for the Above Example An ARI of a subprogram is created in the stack when the subprogram is called – – 42 The return address, the static link (ignored) and the dynamic link are stored Parameter are pushed onto the stack accordingly Local variable are then allocated from the stack one by one. The local offset from the bottom of the current ARI will be noted so that these variables can be accessed Access to non-local variables are made through the ignored static links

Summary for the Above Example An ARI of a subprogram is created in the stack when the subprogram is called – – 42 The return address, the static link (ignored) and the dynamic link are stored Parameter are pushed onto the stack accordingly Local variable are then allocated from the stack one by one. The local offset from the bottom of the current ARI will be noted so that these variables can be accessed Access to non-local variables are made through the ignored static links

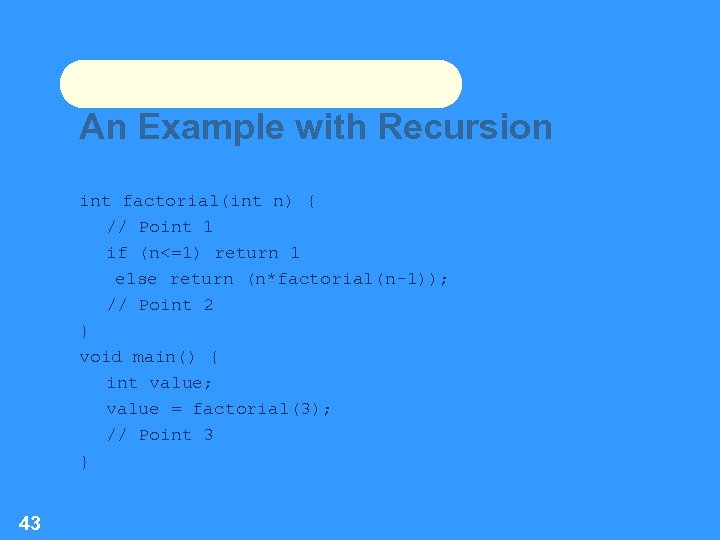

An Example with Recursion int factorial(int n) { // Point 1 if (n<=1) return 1 else return (n*factorial(n-1)); // Point 2 } void main() { int value; value = factorial(3); // Point 3 } 43

An Example with Recursion int factorial(int n) { // Point 1 if (n<=1) return 1 else return (n*factorial(n-1)); // Point 2 } void main() { int value; value = factorial(3); // Point 3 } 43

Stack Contents for the Recursive Program 44 Point 1, 1 st call Point 1, 2 nd call

Stack Contents for the Recursive Program 44 Point 1, 1 st call Point 1, 2 nd call

45 Point 1, 3 rd Call

45 Point 1, 3 rd Call

46 Point 2, after 3 rd Call completed

46 Point 2, after 3 rd Call completed

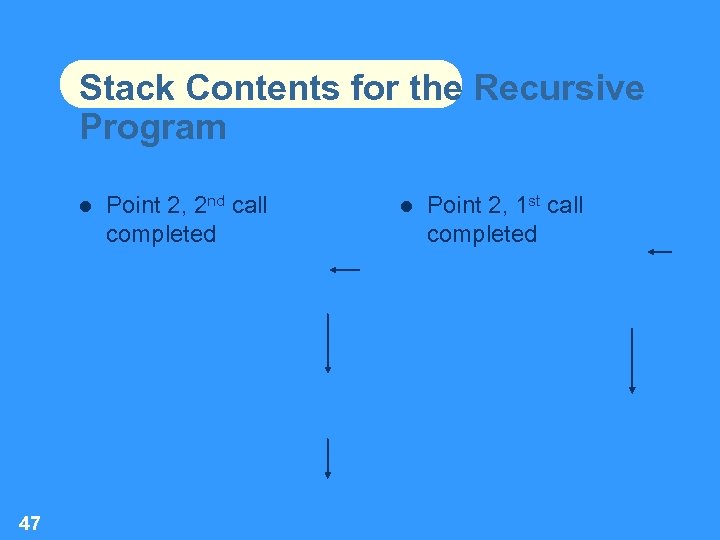

Stack Contents for the Recursive Program 47 Point 2, 2 nd call completed Point 2, 1 st call completed

Stack Contents for the Recursive Program 47 Point 2, 2 nd call completed Point 2, 1 st call completed

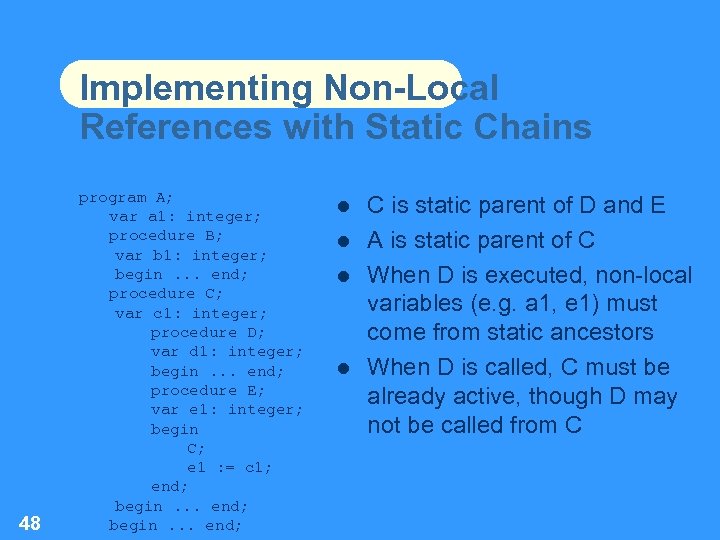

Implementing Non-Local References with Static Chains 48 program A; var a 1: integer; procedure B; var b 1: integer; begin. . . end; procedure C; var c 1: integer; procedure D; var d 1: integer; begin. . . end; procedure E; var e 1: integer; begin C; e 1 : = c 1; end; begin. . . end; C is static parent of D and E A is static parent of C When D is executed, non-local variables (e. g. a 1, e 1) must come from static ancestors When D is called, C must be already active, though D may not be called from C

Implementing Non-Local References with Static Chains 48 program A; var a 1: integer; procedure B; var b 1: integer; begin. . . end; procedure C; var c 1: integer; procedure D; var d 1: integer; begin. . . end; procedure E; var e 1: integer; begin C; e 1 : = c 1; end; begin. . . end; C is static parent of D and E A is static parent of C When D is executed, non-local variables (e. g. a 1, e 1) must come from static ancestors When D is called, C must be already active, though D may not be called from C

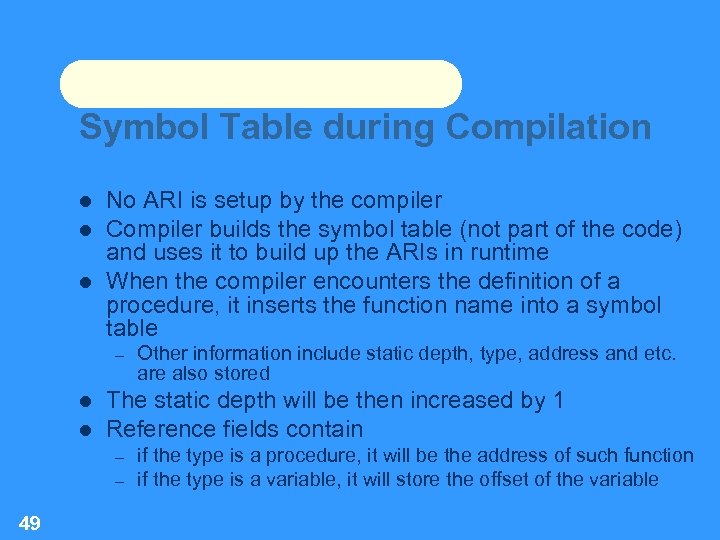

Symbol Table during Compilation No ARI is setup by the compiler Compiler builds the symbol table (not part of the code) and uses it to build up the ARIs in runtime When the compiler encounters the definition of a procedure, it inserts the function name into a symbol table – The static depth will be then increased by 1 Reference fields contain – – 49 Other information include static depth, type, address and etc. are also stored if the type is a procedure, it will be the address of such function if the type is a variable, it will store the offset of the variable

Symbol Table during Compilation No ARI is setup by the compiler Compiler builds the symbol table (not part of the code) and uses it to build up the ARIs in runtime When the compiler encounters the definition of a procedure, it inserts the function name into a symbol table – The static depth will be then increased by 1 Reference fields contain – – 49 Other information include static depth, type, address and etc. are also stored if the type is a procedure, it will be the address of such function if the type is a variable, it will store the offset of the variable

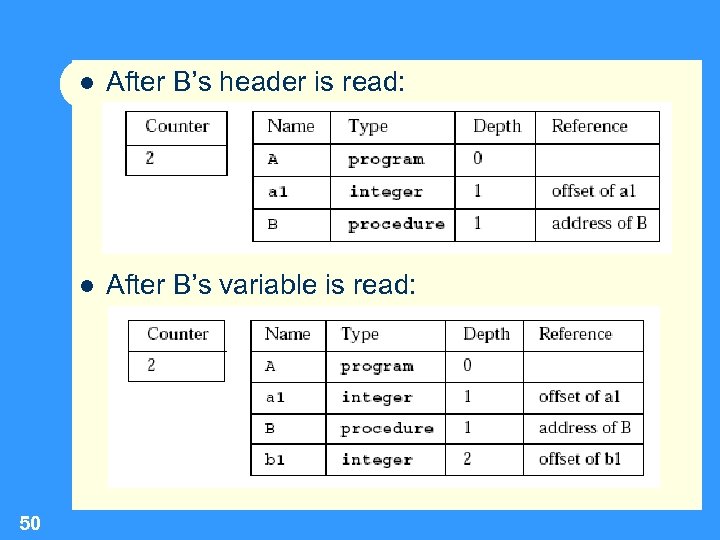

50 After B’s header is read: After B’s variable is read:

50 After B’s header is read: After B’s variable is read:

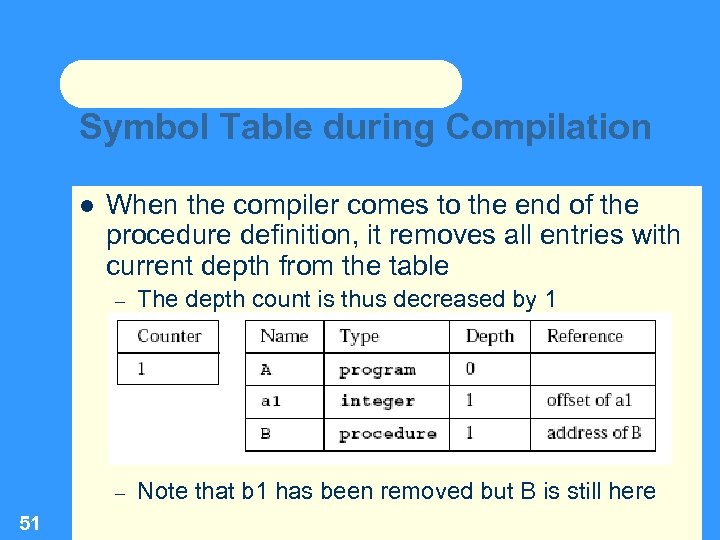

Symbol Table during Compilation When the compiler comes to the end of the procedure definition, it removes all entries with current depth from the table – – 51 The depth count is thus decreased by 1 Note that b 1 has been removed but B is still here

Symbol Table during Compilation When the compiler comes to the end of the procedure definition, it removes all entries with current depth from the table – – 51 The depth count is thus decreased by 1 Note that b 1 has been removed but B is still here

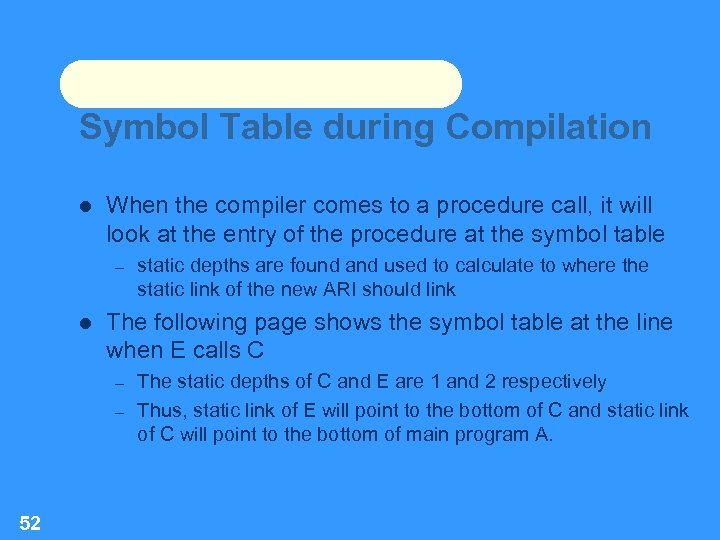

Symbol Table during Compilation When the compiler comes to a procedure call, it will look at the entry of the procedure at the symbol table – The following page shows the symbol table at the line when E calls C – – 52 static depths are found and used to calculate to where the static link of the new ARI should link The static depths of C and E are 1 and 2 respectively Thus, static link of E will point to the bottom of C and static link of C will point to the bottom of main program A.

Symbol Table during Compilation When the compiler comes to a procedure call, it will look at the entry of the procedure at the symbol table – The following page shows the symbol table at the line when E calls C – – 52 static depths are found and used to calculate to where the static link of the new ARI should link The static depths of C and E are 1 and 2 respectively Thus, static link of E will point to the bottom of C and static link of C will point to the bottom of main program A.

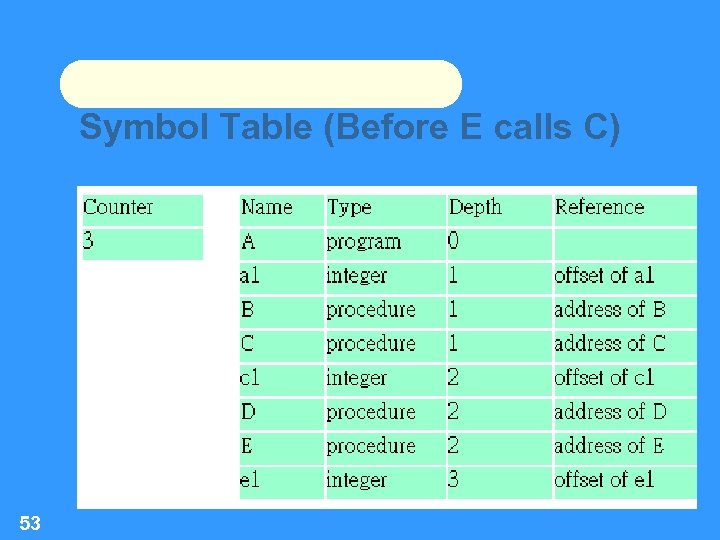

Symbol Table (Before E calls C) 53

Symbol Table (Before E calls C) 53

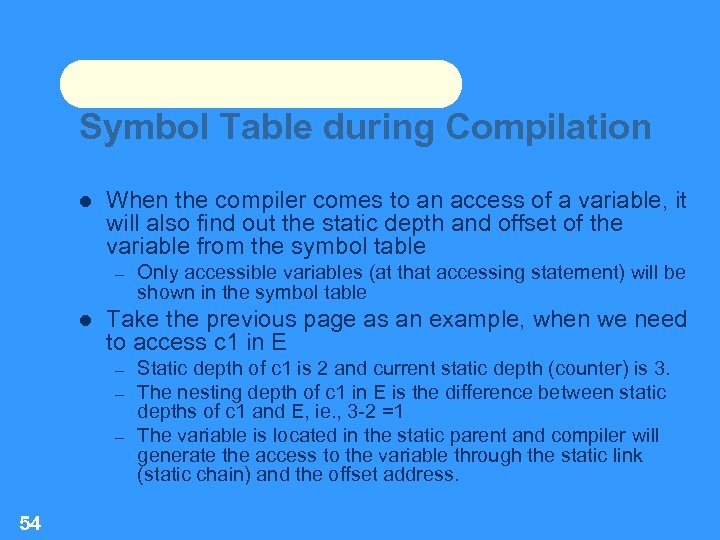

Symbol Table during Compilation When the compiler comes to an access of a variable, it will also find out the static depth and offset of the variable from the symbol table – Take the previous page as an example, when we need to access c 1 in E – – – 54 Only accessible variables (at that accessing statement) will be shown in the symbol table Static depth of c 1 is 2 and current static depth (counter) is 3. The nesting depth of c 1 in E is the difference between static depths of c 1 and E, ie. , 3 -2 =1 The variable is located in the static parent and compiler will generate the access to the variable through the static link (static chain) and the offset address.

Symbol Table during Compilation When the compiler comes to an access of a variable, it will also find out the static depth and offset of the variable from the symbol table – Take the previous page as an example, when we need to access c 1 in E – – – 54 Only accessible variables (at that accessing statement) will be shown in the symbol table Static depth of c 1 is 2 and current static depth (counter) is 3. The nesting depth of c 1 in E is the difference between static depths of c 1 and E, ie. , 3 -2 =1 The variable is located in the static parent and compiler will generate the access to the variable through the static link (static chain) and the offset address.

At the Execution Stage – Formation of ARI When the control reaches a subprogram call, the return address will be pushed onto the stack Then, the ARI of the static parent of the called subprogram is found by following the static chain – 55 Static depths of the caller and called subprogram is stored in the program in compile time The static link of the new ARI is then set to point to the found location and pushed onto the stack Then, the dynamic link pointing to the top of the previous ARI is pushed onto the stack

At the Execution Stage – Formation of ARI When the control reaches a subprogram call, the return address will be pushed onto the stack Then, the ARI of the static parent of the called subprogram is found by following the static chain – 55 Static depths of the caller and called subprogram is stored in the program in compile time The static link of the new ARI is then set to point to the found location and pushed onto the stack Then, the dynamic link pointing to the top of the previous ARI is pushed onto the stack

At the Execution Stage – Formation of ARI (cont’d) 56 Parameters are then pushed to the stack Then, the storage for local variables And lastly the control is passed to the subprogram Non-local varaibles is accessed by following the static chain a number of times depends on the static depths When a subprogram terminates, the top ARI will be removed and the top of stack will point to the position pointed by the dynamic link

At the Execution Stage – Formation of ARI (cont’d) 56 Parameters are then pushed to the stack Then, the storage for local variables And lastly the control is passed to the subprogram Non-local varaibles is accessed by following the static chain a number of times depends on the static depths When a subprogram terminates, the top ARI will be removed and the top of stack will point to the position pointed by the dynamic link

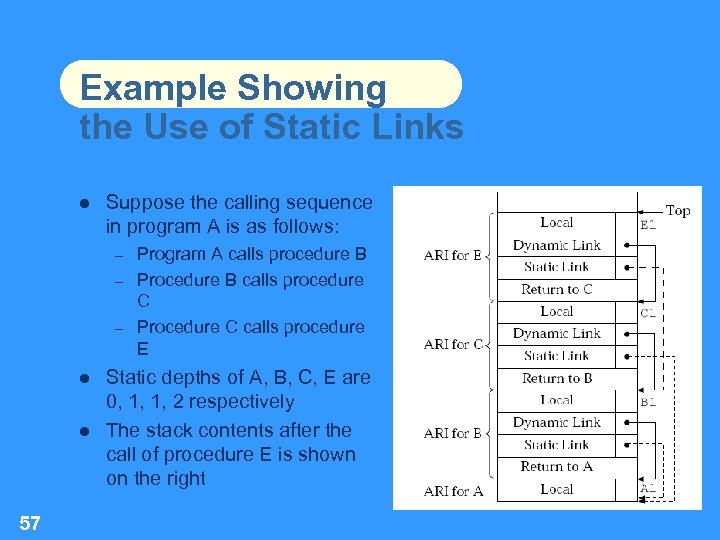

Example Showing the Use of Static Links Suppose the calling sequence in program A is as follows: – – – 57 Program A calls procedure B Procedure B calls procedure C Procedure C calls procedure E Static depths of A, B, C, E are 0, 1, 1, 2 respectively The stack contents after the call of procedure E is shown on the right

Example Showing the Use of Static Links Suppose the calling sequence in program A is as follows: – – – 57 Program A calls procedure B Procedure B calls procedure C Procedure C calls procedure E Static depths of A, B, C, E are 0, 1, 1, 2 respectively The stack contents after the call of procedure E is shown on the right

Implementing Non-Local References with Displays A non-local access of avariables is always to the static ancestors of the current subprogram When a subprogram is called, its static ancestors must be already active We can have an array that always points to the ARIs of all different static ancestors of the current program – 58 So, when we need the static ancestor of depth i, we can find it by looking up the i-th element in the array Such array is called a display

Implementing Non-Local References with Displays A non-local access of avariables is always to the static ancestors of the current subprogram When a subprogram is called, its static ancestors must be already active We can have an array that always points to the ARIs of all different static ancestors of the current program – 58 So, when we need the static ancestor of depth i, we can find it by looking up the i-th element in the array Such array is called a display

Working with Display When a subprogram is called – – When a subprogram returns – – 59 If the static depth of the subprogram is k, then the ARI of the subprogram will store the entry in the display that corresponds to the static depth k. The pointer in the display for the static depth k will now point to this new ARI copy the pointer which has been saved earlier back to the corresponding entry in the display. remove the ARI from the stack

Working with Display When a subprogram is called – – When a subprogram returns – – 59 If the static depth of the subprogram is k, then the ARI of the subprogram will store the entry in the display that corresponds to the static depth k. The pointer in the display for the static depth k will now point to this new ARI copy the pointer which has been saved earlier back to the corresponding entry in the display. remove the ARI from the stack

Example of Using Display program A; var aa: integer; procedure B; var bb: integer; procedure C; var cc: integer; procedure D; var dd: integer; begin { D starts } aa: =1; if aa=0 then B; end; { D ends } 60 begin { C starts } D; end; { C ends } begin { B starts } if aa=0 then C; end; { B ends } begin { A begin } aa: =0; B; end; { A ends }

Example of Using Display program A; var aa: integer; procedure B; var bb: integer; procedure C; var cc: integer; procedure D; var dd: integer; begin { D starts } aa: =1; if aa=0 then B; end; { D ends } 60 begin { C starts } D; end; { C ends } begin { B starts } if aa=0 then C; end; { B ends } begin { A begin } aa: =0; B; end; { A ends }

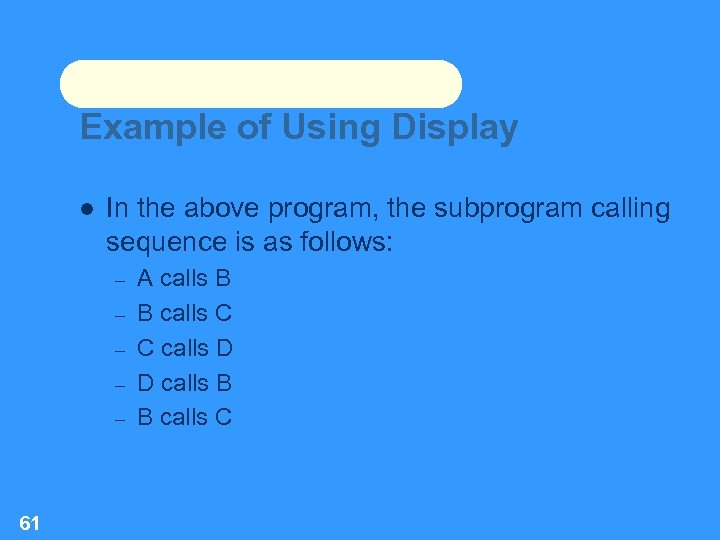

Example of Using Display In the above program, the subprogram calling sequence is as follows: – – – 61 A calls B B calls C C calls D D calls B B calls C

Example of Using Display In the above program, the subprogram calling sequence is as follows: – – – 61 A calls B B calls C C calls D D calls B B calls C

Example of Using Display When ARI of A is pushed onto the stack: When A calls B – – 62 static depth of B = 1 no display entry 1 yet

Example of Using Display When ARI of A is pushed onto the stack: When A calls B – – 62 static depth of B = 1 no display entry 1 yet

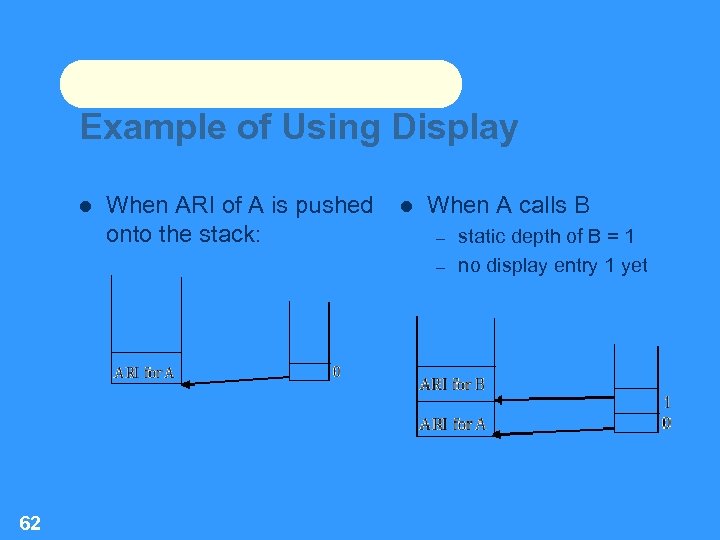

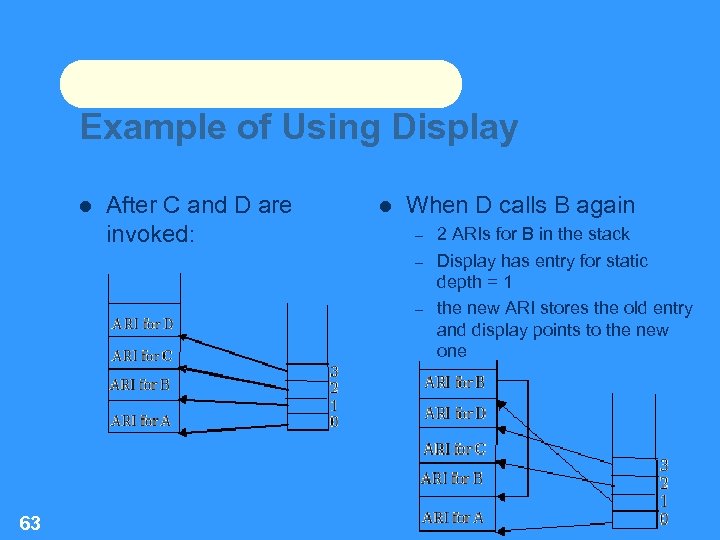

Example of Using Display After C and D are invoked: When D calls B again – – – 63 2 ARIs for B in the stack Display has entry for static depth = 1 the new ARI stores the old entry and display points to the new one

Example of Using Display After C and D are invoked: When D calls B again – – – 63 2 ARIs for B in the stack Display has entry for static depth = 1 the new ARI stores the old entry and display points to the new one

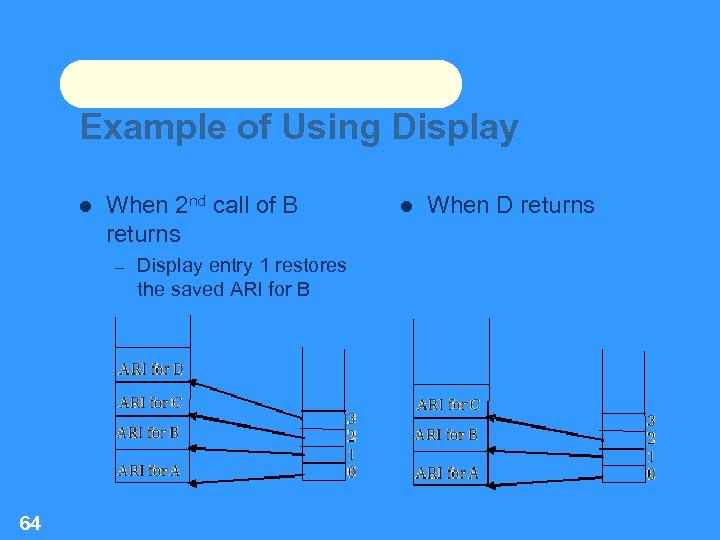

Example of Using Display When 2 nd call of B returns – 64 Display entry 1 restores the saved ARI for B When D returns

Example of Using Display When 2 nd call of B returns – 64 Display entry 1 restores the saved ARI for B When D returns

Accessing Non-Local Variables Using Display To access a non-local variable, we need to know: – – In procedure D in our example – – 65 the display offset – the static depth of the variable the local offset - the location of the variable from the corresponding ARI variable aa is referenced display offset of aa is 0 (found in the symbol table) local offset of aa is also stored in the symbol table We can then find aa through the display

Accessing Non-Local Variables Using Display To access a non-local variable, we need to know: – – In procedure D in our example – – 65 the display offset – the static depth of the variable the local offset - the location of the variable from the corresponding ARI variable aa is referenced display offset of aa is 0 (found in the symbol table) local offset of aa is also stored in the symbol table We can then find aa through the display

Implementing Dynamic Scoping In a dynamic scoping languages, the actual identity of a non-local variable is not know until runtime Two different methods are used to implement dynamic scoping – – 66 Deep access Shallow access In both methods, static link is no longer present in ARIs

Implementing Dynamic Scoping In a dynamic scoping languages, the actual identity of a non-local variable is not know until runtime Two different methods are used to implement dynamic scoping – – 66 Deep access Shallow access In both methods, static link is no longer present in ARIs

Deep Access 67 Deep access apply a concept similar in static scoped language with nested subprograms References to non-local variables can be resolved by searching through the ARI that are currently activated through the dynamic links The dynamic chain links all subprograms ARI in the reverse order in which they were activated – that is exactly the way we find the non-local variables in a dynamic scoped language

Deep Access 67 Deep access apply a concept similar in static scoped language with nested subprograms References to non-local variables can be resolved by searching through the ARI that are currently activated through the dynamic links The dynamic chain links all subprograms ARI in the reverse order in which they were activated – that is exactly the way we find the non-local variables in a dynamic scoped language

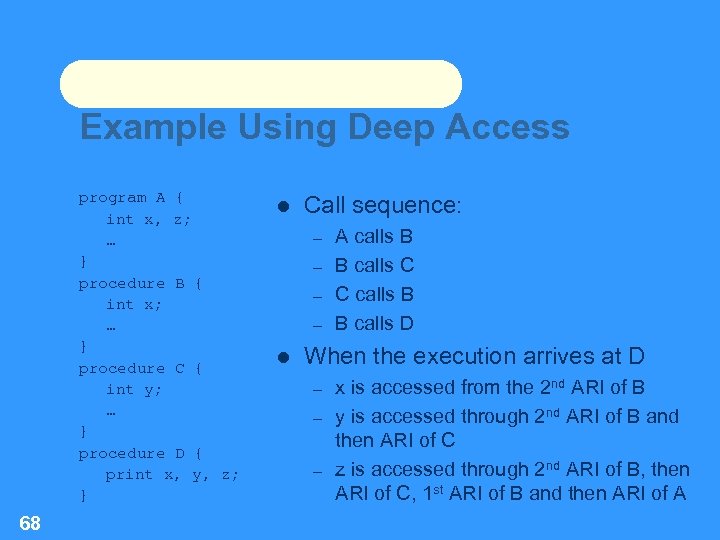

Example Using Deep Access program A { int x, z; … } procedure B { int x; … } procedure C { int y; … } procedure D { print x, y, z; } 68 Call sequence: – – A calls B B calls C C calls B B calls D When the execution arrives at D – – – x is accessed from the 2 nd ARI of B y is accessed through 2 nd ARI of B and then ARI of C z is accessed through 2 nd ARI of B, then ARI of C, 1 st ARI of B and then ARI of A

Example Using Deep Access program A { int x, z; … } procedure B { int x; … } procedure C { int y; … } procedure D { print x, y, z; } 68 Call sequence: – – A calls B B calls C C calls B B calls D When the execution arrives at D – – – x is accessed from the 2 nd ARI of B y is accessed through 2 nd ARI of B and then ARI of C z is accessed through 2 nd ARI of B, then ARI of C, 1 st ARI of B and then ARI of A

Shallow Access To avoid the time-consuming search in the deep access method, we maintain a central table for variables when using shallow access Suppose the sample program on the right has the following calling sequence – – 69 main calls sub 1 (recursive) sub 1 calls sub 2 calls sub 3 void sub 3() { int x, z; x = u + v; … } void sub 2() { int w, x; … } void sub 1() { int v, w; … } void main() { int v, u; … }

Shallow Access To avoid the time-consuming search in the deep access method, we maintain a central table for variables when using shallow access Suppose the sample program on the right has the following calling sequence – – 69 main calls sub 1 (recursive) sub 1 calls sub 2 calls sub 3 void sub 3() { int x, z; x = u + v; … } void sub 2() { int w, x; … } void sub 1() { int v, w; … } void main() { int v, u; … }

70

70

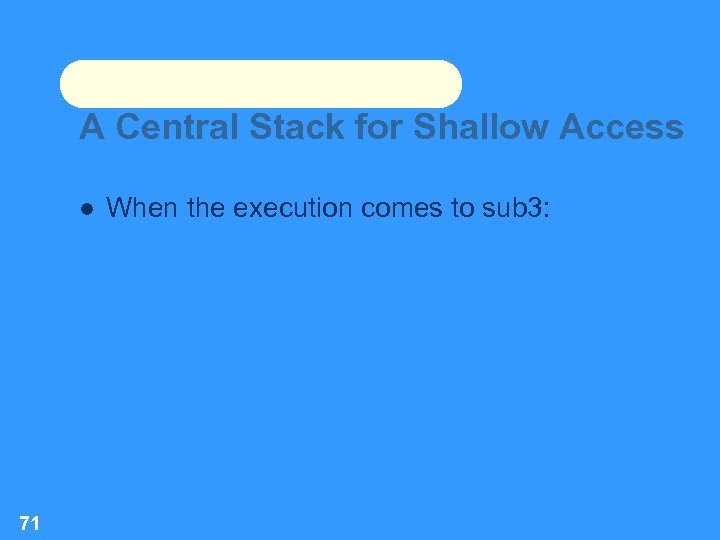

A Central Stack for Shallow Access 71 When the execution comes to sub 3:

A Central Stack for Shallow Access 71 When the execution comes to sub 3: