2f26413e2d4598251b1d3db64107f975.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 44

MODELLING INFLUENZAASSOCIATED MORTALITY USING TIME-SERIES REGRESSION APPROACH Stefan Ma, CStat, Ph. D stefan_ma@moh. gov. sg Epidemiology & Disease Control Division Ministry of Health, Singapore Taiwan Hsinchu Workshop on Mathematical Modeling of Infectious Disease (May 31 - June 1, 2006)

MODELLING INFLUENZAASSOCIATED MORTALITY USING TIME-SERIES REGRESSION APPROACH Stefan Ma, CStat, Ph. D stefan_ma@moh. gov. sg Epidemiology & Disease Control Division Ministry of Health, Singapore Taiwan Hsinchu Workshop on Mathematical Modeling of Infectious Disease (May 31 - June 1, 2006)

Background n n n Influenza virus infections cause excess morbidity and mortality in temperate countries. In the Northern and Southern Hemisphere, influenza epidemics occur nearly every winter, leading to an increase in hospitalization and mortality. However, little is known about the disease burden of influenza in tropical regions, e. g. Singapore, where the effect of influenza is thought to be less.

Background n n n Influenza virus infections cause excess morbidity and mortality in temperate countries. In the Northern and Southern Hemisphere, influenza epidemics occur nearly every winter, leading to an increase in hospitalization and mortality. However, little is known about the disease burden of influenza in tropical regions, e. g. Singapore, where the effect of influenza is thought to be less.

Epidemiology of Influenza n Highly infectious viral illness n Epidemics reported since at least 1510 n At least 4 pandemics in 19 th century n n Estimated 21 million deaths worldwide in pandemic of 1918 -1919 Virus first isolated in 1933

Epidemiology of Influenza n Highly infectious viral illness n Epidemics reported since at least 1510 n At least 4 pandemics in 19 th century n n Estimated 21 million deaths worldwide in pandemic of 1918 -1919 Virus first isolated in 1933

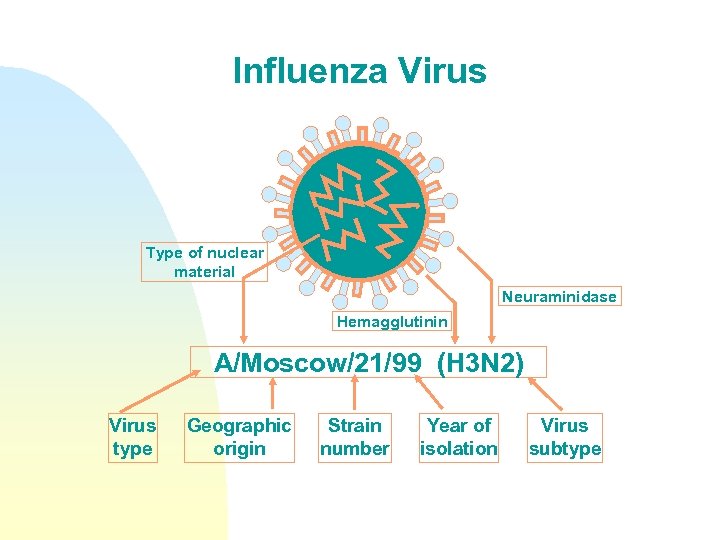

Influenza Virus Type of nuclear material Neuraminidase Hemagglutinin A/Moscow/21/99 (H 3 N 2) Virus type Geographic origin Strain number Year of isolation Virus subtype

Influenza Virus Type of nuclear material Neuraminidase Hemagglutinin A/Moscow/21/99 (H 3 N 2) Virus type Geographic origin Strain number Year of isolation Virus subtype

Influenza Virus n Single-stranded RNA virus n Family Orthomyxoviridae n 3 types: A, B, C n Subtypes of type A determined by hemagglutinin and neuraminidase

Influenza Virus n Single-stranded RNA virus n Family Orthomyxoviridae n 3 types: A, B, C n Subtypes of type A determined by hemagglutinin and neuraminidase

Influenza Virus Strains n n n Type A- moderate to severe illness - all age groups - humans and other animals Type B- milder epidemics - humans only - primarily affects children Type C- rarely reported in humans - no epidemics

Influenza Virus Strains n n n Type A- moderate to severe illness - all age groups - humans and other animals Type B- milder epidemics - humans only - primarily affects children Type C- rarely reported in humans - no epidemics

Influenza Antigenic Changes n Structure of hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) periodically change n Shift Major change, new subtype Exchange of gene segment May result in pandemic n Drift Minor change, same subtype Point mutations in gene May result in epidemic

Influenza Antigenic Changes n Structure of hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) periodically change n Shift Major change, new subtype Exchange of gene segment May result in pandemic n Drift Minor change, same subtype Point mutations in gene May result in epidemic

Examples of Influenza Antigenic Changes n n Antigenic shift: u H 2 N 2 circulated in 1957 -1967 u H 3 N 2 appeared in 1968 and completely replaced H 2 N 2 Antigenic drift u In 1997, A/Wuhan/359/95 (H 3 N 2) virus was dominant u A/Sydney/5/97 (H 3 N 2) appeared in late 1997 and became the dominant virus in 1998

Examples of Influenza Antigenic Changes n n Antigenic shift: u H 2 N 2 circulated in 1957 -1967 u H 3 N 2 appeared in 1968 and completely replaced H 2 N 2 Antigenic drift u In 1997, A/Wuhan/359/95 (H 3 N 2) virus was dominant u A/Sydney/5/97 (H 3 N 2) appeared in late 1997 and became the dominant virus in 1998

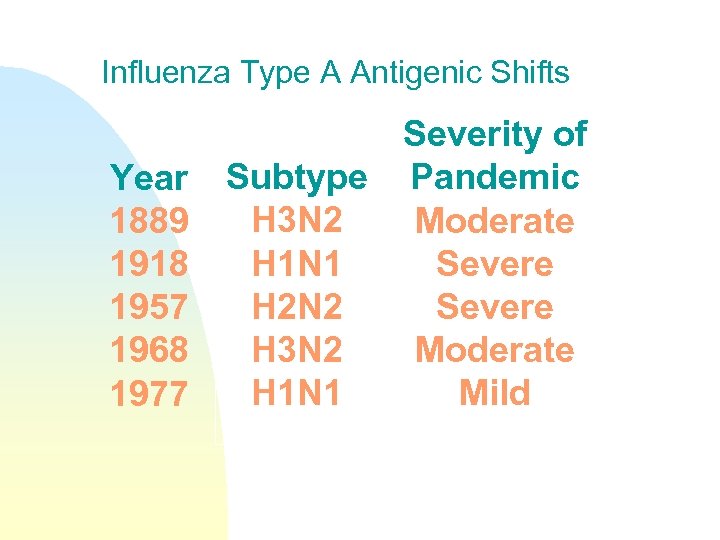

Influenza Type A Antigenic Shifts Year 1889 1918 1957 1968 1977 Severity of Subtype Pandemic H 3 N 2 Moderate H 1 N 1 Severe H 2 N 2 Severe H 3 N 2 Moderate H 1 N 1 Mild

Influenza Type A Antigenic Shifts Year 1889 1918 1957 1968 1977 Severity of Subtype Pandemic H 3 N 2 Moderate H 1 N 1 Severe H 2 N 2 Severe H 3 N 2 Moderate H 1 N 1 Mild

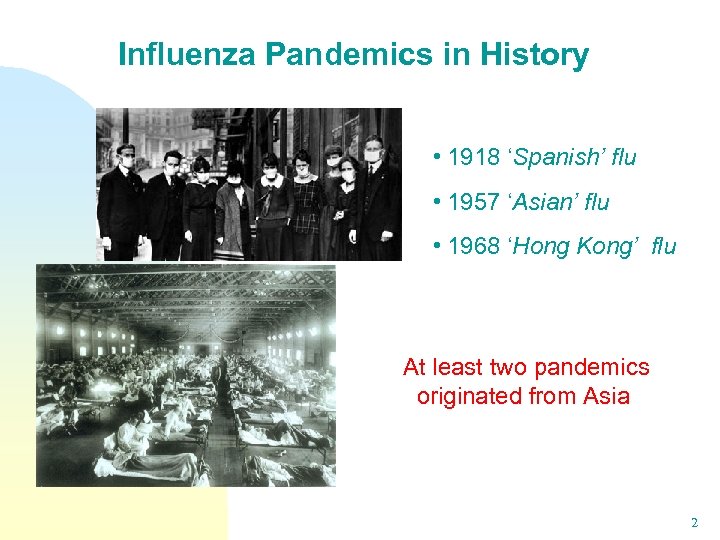

Influenza Pandemics in History • 1918 ‘Spanish’ flu • 1957 ‘Asian’ flu • 1968 ‘Hong Kong’ flu At least two pandemics originated from Asia 2

Influenza Pandemics in History • 1918 ‘Spanish’ flu • 1957 ‘Asian’ flu • 1968 ‘Hong Kong’ flu At least two pandemics originated from Asia 2

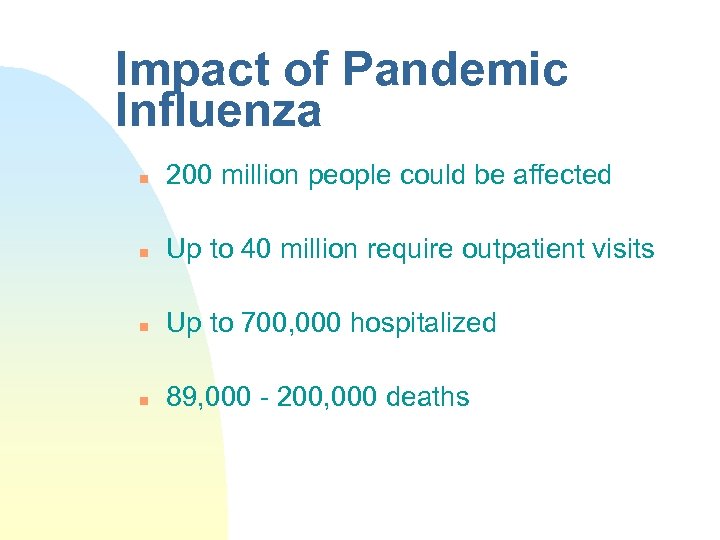

Impact of Pandemic Influenza n 200 million people could be affected n Up to 40 million require outpatient visits n Up to 700, 000 hospitalized n 89, 000 - 200, 000 deaths

Impact of Pandemic Influenza n 200 million people could be affected n Up to 40 million require outpatient visits n Up to 700, 000 hospitalized n 89, 000 - 200, 000 deaths

Influenza • Self-limiting and minor symptoms: sudden onset, fever, headache, muscle pain, dry cough, sore throat • Transmitted through droplets • Possible serious complications, such as pneumonia and cerebrovascular diseases

Influenza • Self-limiting and minor symptoms: sudden onset, fever, headache, muscle pain, dry cough, sore throat • Transmitted through droplets • Possible serious complications, such as pneumonia and cerebrovascular diseases

Objectives n To examine the influenza-associated mortality in tropical Singapore using time-series regression approach

Objectives n To examine the influenza-associated mortality in tropical Singapore using time-series regression approach

Population attributable fraction (risk) or burden For a dichotomous (harmful) exposure Proportion that would not have occurred with zero exposure (e. g. , smoking status). But Needs also to be generalized to continuous exposures (e. g. , blood pressure level); and To preventive exposures e. g. , physical activity.

Population attributable fraction (risk) or burden For a dichotomous (harmful) exposure Proportion that would not have occurred with zero exposure (e. g. , smoking status). But Needs also to be generalized to continuous exposures (e. g. , blood pressure level); and To preventive exposures e. g. , physical activity.

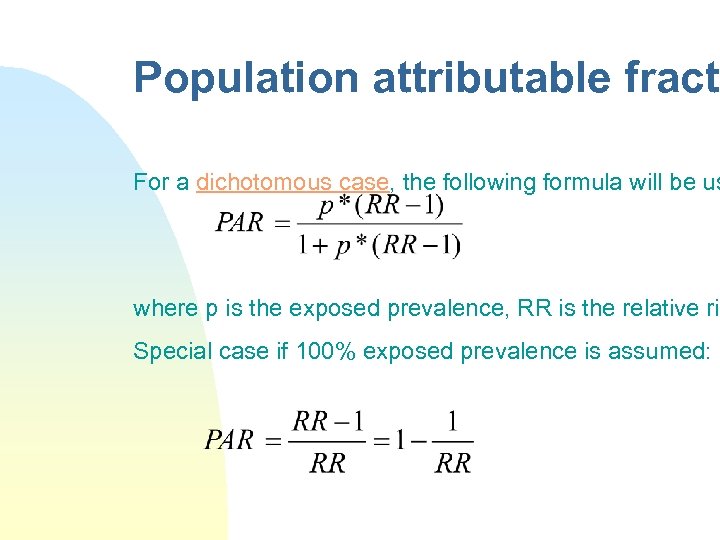

Population attributable fracti For a dichotomous case, the following formula will be us where p is the exposed prevalence, RR is the relative ris Special case if 100% exposed prevalence is assumed:

Population attributable fracti For a dichotomous case, the following formula will be us where p is the exposed prevalence, RR is the relative ris Special case if 100% exposed prevalence is assumed:

Generalising to preventive exposures For a dichotomous protective exposure Proportion of the cases that would have occurred in the absence of exposure that were prevented by the exposure Note: denominator is the hypothetical total applying in the ‘unprotected’ counterfactual EG for moderate alcohol drinking and IHD Prevented fraction = Prevented cases /Total expected in counterfactual non-drinking population

Generalising to preventive exposures For a dichotomous protective exposure Proportion of the cases that would have occurred in the absence of exposure that were prevented by the exposure Note: denominator is the hypothetical total applying in the ‘unprotected’ counterfactual EG for moderate alcohol drinking and IHD Prevented fraction = Prevented cases /Total expected in counterfactual non-drinking population

Population attributable fraction (risk) or burden Generalising to continuous exposures attributable burden = difference between burden currently observed and what would have been observed under a (past) counterfactual exposure distribution

Population attributable fraction (risk) or burden Generalising to continuous exposures attributable burden = difference between burden currently observed and what would have been observed under a (past) counterfactual exposure distribution

Problems encountered n n But, all these exposure data are measured at the individual levels that are collected using individual-based study design. There is problem in studying impacts of influenza in human setting! u Because of no individual exposure data available.

Problems encountered n n But, all these exposure data are measured at the individual levels that are collected using individual-based study design. There is problem in studying impacts of influenza in human setting! u Because of no individual exposure data available.

Possible solution n Epidemiological time-series data using regression approach could help? !

Possible solution n Epidemiological time-series data using regression approach could help? !

Two State-of-the-art methods: 1. Comparative method: u The average numbers of deaths or hospital admissions during the months assumed to have low or no influenza virus circulation are defined, followed by calculation of the excess mortality or hospitalization by subtracting this baseline from the observed numbers of deaths or hospital admissions during influenza epidemics.

Two State-of-the-art methods: 1. Comparative method: u The average numbers of deaths or hospital admissions during the months assumed to have low or no influenza virus circulation are defined, followed by calculation of the excess mortality or hospitalization by subtracting this baseline from the observed numbers of deaths or hospital admissions during influenza epidemics.

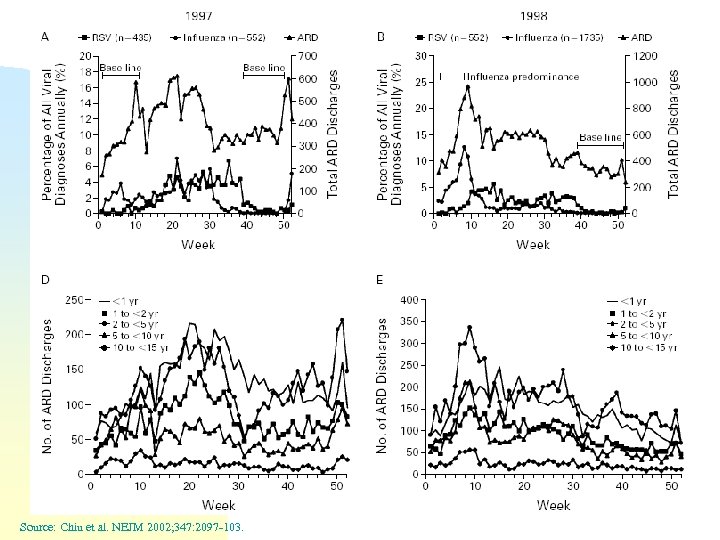

Source: Chiu et al. NEJM 2002; 347: 2097 -103.

Source: Chiu et al. NEJM 2002; 347: 2097 -103.

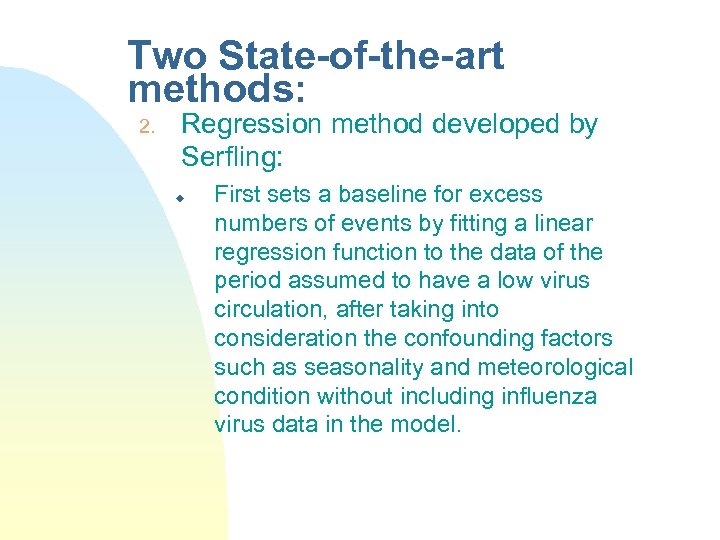

Two State-of-the-art methods: 2. Regression method developed by Serfling: u First sets a baseline for excess numbers of events by fitting a linear regression function to the data of the period assumed to have a low virus circulation, after taking into consideration the confounding factors such as seasonality and meteorological condition without including influenza virus data in the model.

Two State-of-the-art methods: 2. Regression method developed by Serfling: u First sets a baseline for excess numbers of events by fitting a linear regression function to the data of the period assumed to have a low virus circulation, after taking into consideration the confounding factors such as seasonality and meteorological condition without including influenza virus data in the model.

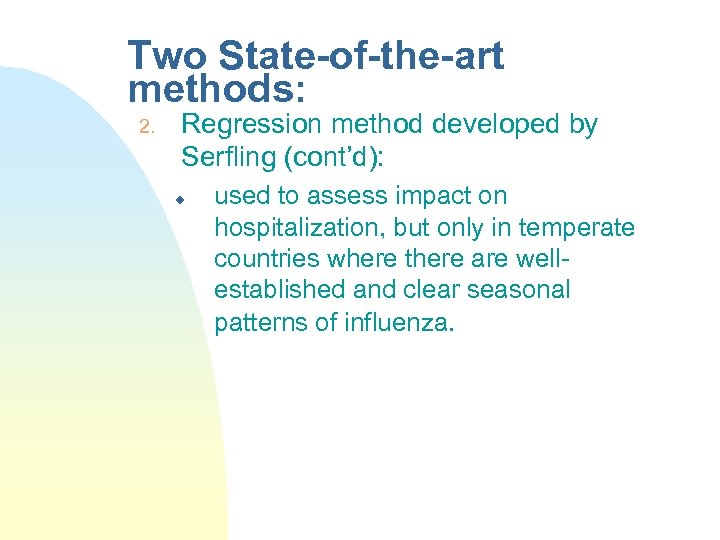

Two State-of-the-art methods: 2. Regression method developed by Serfling (cont’d): u used to assess impact on hospitalization, but only in temperate countries where there are wellestablished and clear seasonal patterns of influenza.

Two State-of-the-art methods: 2. Regression method developed by Serfling (cont’d): u used to assess impact on hospitalization, but only in temperate countries where there are wellestablished and clear seasonal patterns of influenza.

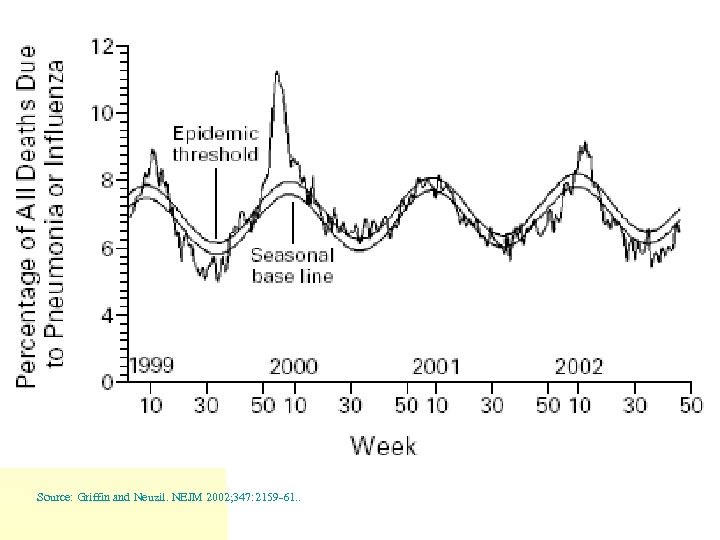

Source: Griffin and Neuzil. NEJM 2002; 347: 2159 -61. .

Source: Griffin and Neuzil. NEJM 2002; 347: 2159 -61. .

Short-coming of these 2 methods: n n Application of either comparative or Serfling methods requires a welldefined seasonal pattern of noninfluenza period. Required alternative approach!

Short-coming of these 2 methods: n n Application of either comparative or Serfling methods requires a welldefined seasonal pattern of noninfluenza period. Required alternative approach!

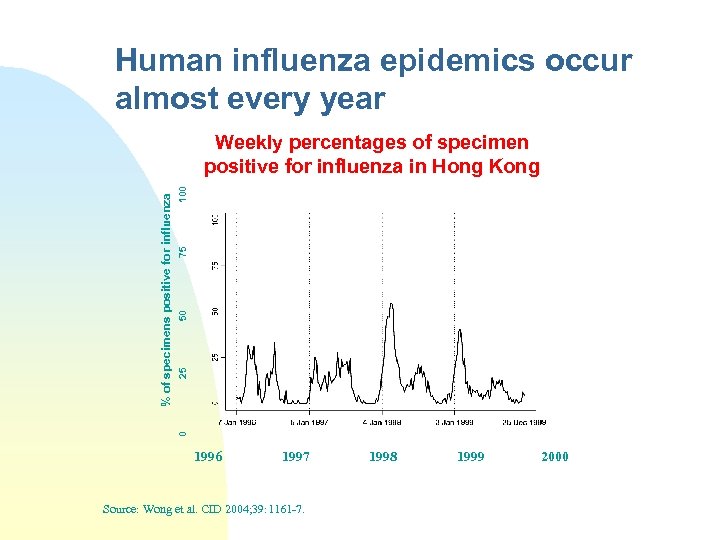

Human influenza epidemics occur almost every year 100 75 50 25 0 % of specimens positive for influenza Weekly percentages of specimen positive for influenza in Hong Kong 1996 1997 Source: Wong et al. CID 2004; 39: 1161 -7. 1998 1999 2000

Human influenza epidemics occur almost every year 100 75 50 25 0 % of specimens positive for influenza Weekly percentages of specimen positive for influenza in Hong Kong 1996 1997 Source: Wong et al. CID 2004; 39: 1161 -7. 1998 1999 2000

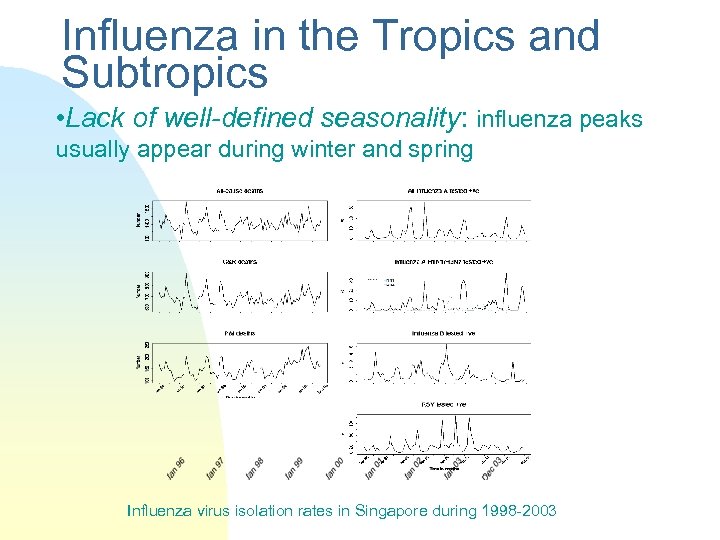

Influenza in the Tropics and Subtropics • Lack of well-defined seasonality: influenza peaks usually appear during winter and spring Influenza virus isolation rates in Singapore during 1998 -2003

Influenza in the Tropics and Subtropics • Lack of well-defined seasonality: influenza peaks usually appear during winter and spring Influenza virus isolation rates in Singapore during 1998 -2003

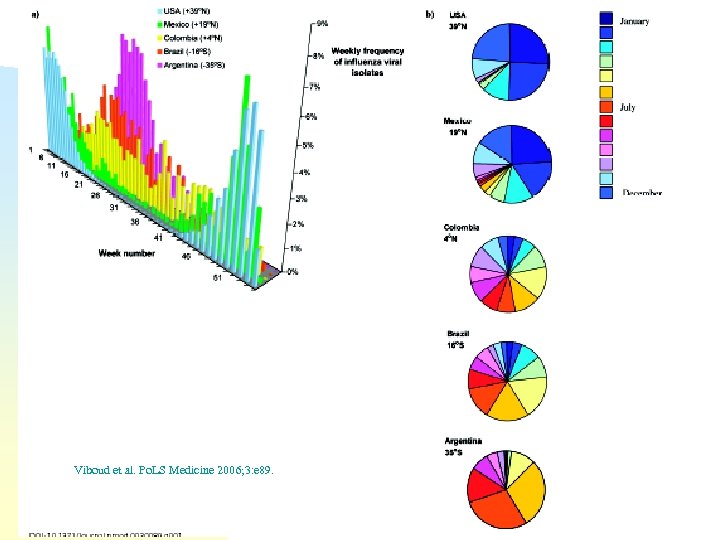

Viboud et al. Po. LS Medicine 2006; 3: e 89.

Viboud et al. Po. LS Medicine 2006; 3: e 89.

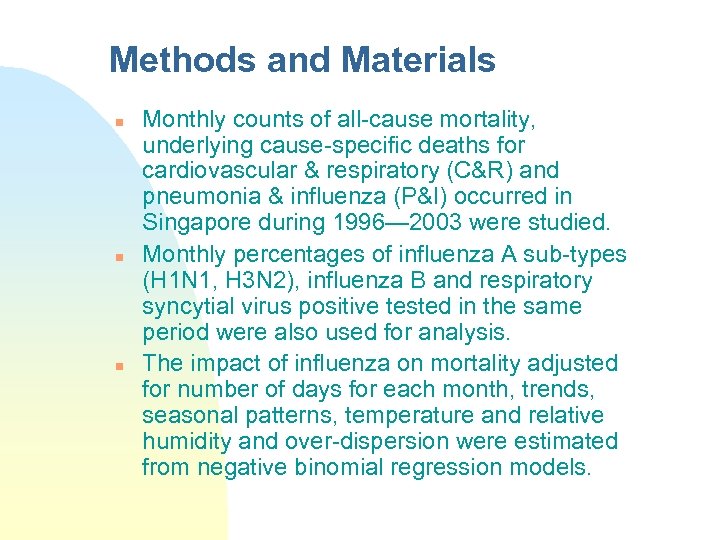

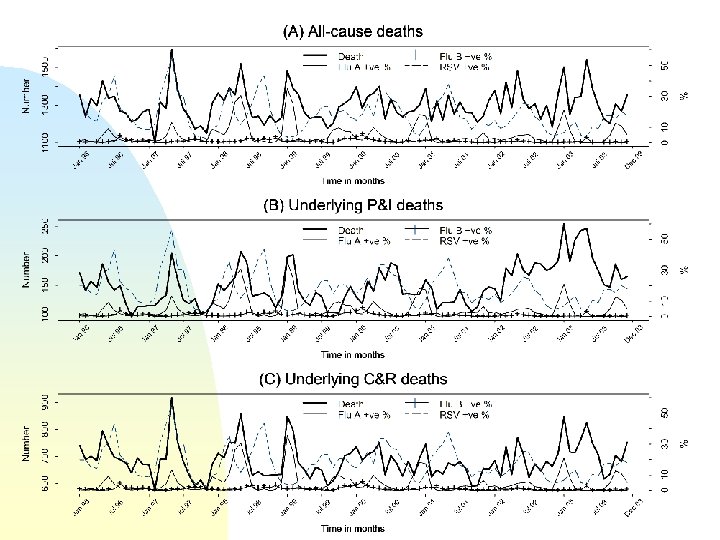

Methods and Materials n n n Monthly counts of all-cause mortality, underlying cause-specific deaths for cardiovascular & respiratory (C&R) and pneumonia & influenza (P&I) occurred in Singapore during 1996— 2003 were studied. Monthly percentages of influenza A sub-types (H 1 N 1, H 3 N 2), influenza B and respiratory syncytial virus positive tested in the same period were also used for analysis. The impact of influenza on mortality adjusted for number of days for each month, trends, seasonal patterns, temperature and relative humidity and over-dispersion were estimated from negative binomial regression models.

Methods and Materials n n n Monthly counts of all-cause mortality, underlying cause-specific deaths for cardiovascular & respiratory (C&R) and pneumonia & influenza (P&I) occurred in Singapore during 1996— 2003 were studied. Monthly percentages of influenza A sub-types (H 1 N 1, H 3 N 2), influenza B and respiratory syncytial virus positive tested in the same period were also used for analysis. The impact of influenza on mortality adjusted for number of days for each month, trends, seasonal patterns, temperature and relative humidity and over-dispersion were estimated from negative binomial regression models.

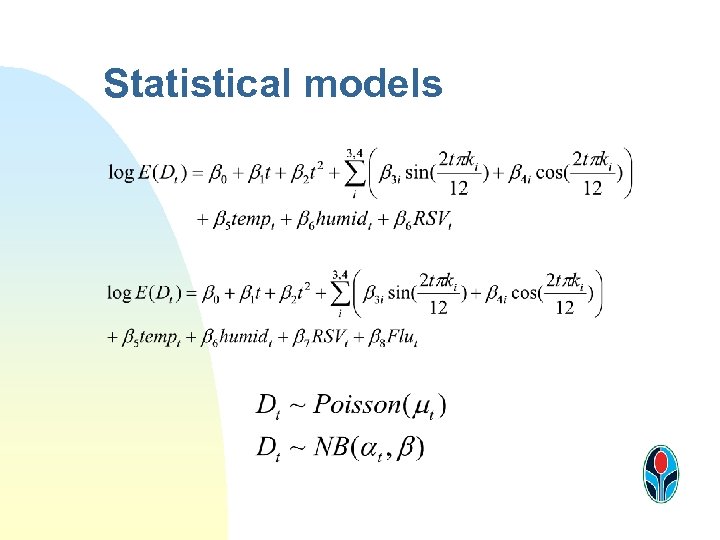

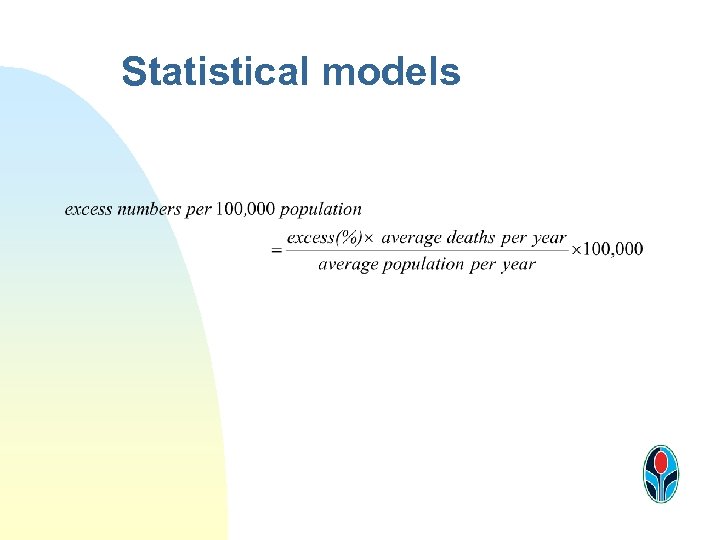

Statistical models

Statistical models

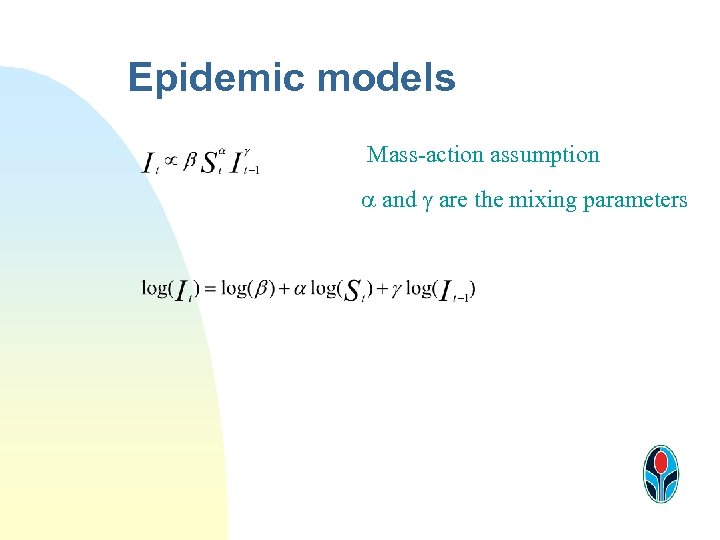

Epidemic models Mass-action assumption a and g are the mixing parameters

Epidemic models Mass-action assumption a and g are the mixing parameters

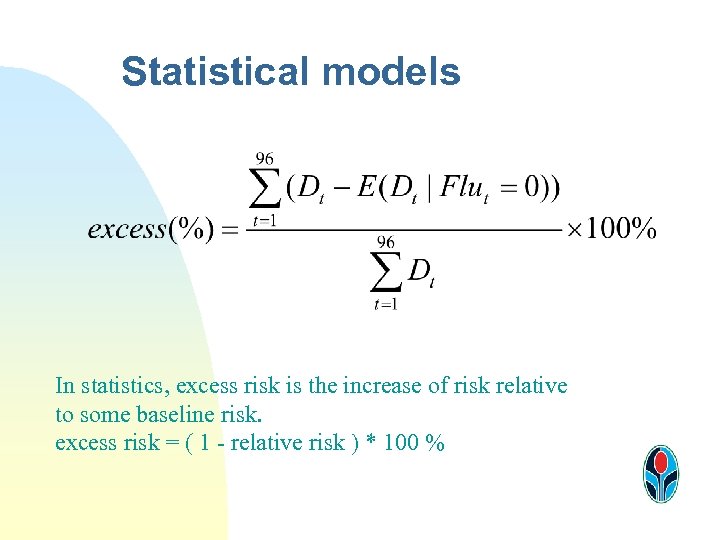

Statistical models In statistics, excess risk is the increase of risk relative to some baseline risk. excess risk = ( 1 - relative risk ) * 100 %

Statistical models In statistics, excess risk is the increase of risk relative to some baseline risk. excess risk = ( 1 - relative risk ) * 100 %

Statistical models

Statistical models

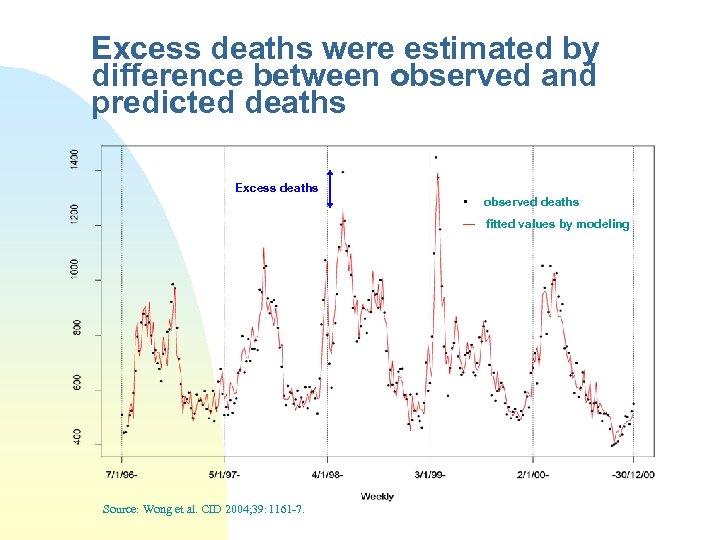

Excess deaths were estimated by difference between observed and predicted deaths Excess deaths • observed deaths — fitted values by modeling Source: Wong et al. CID 2004; 39: 1161 -7.

Excess deaths were estimated by difference between observed and predicted deaths Excess deaths • observed deaths — fitted values by modeling Source: Wong et al. CID 2004; 39: 1161 -7.

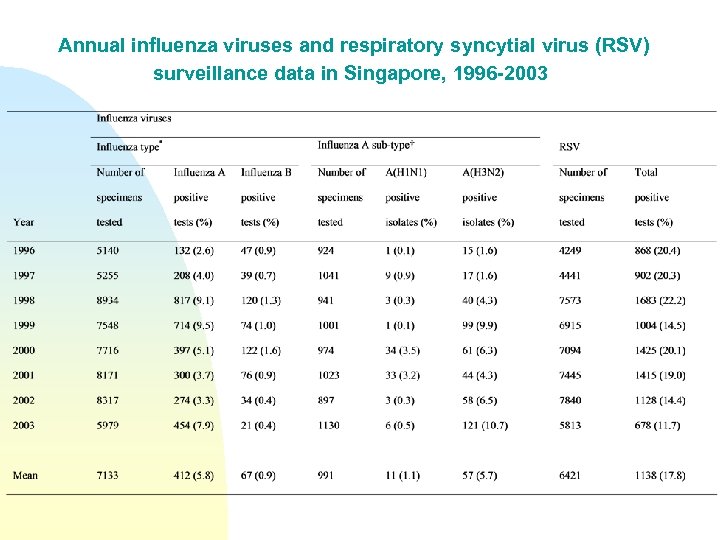

Annual influenza viruses and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) surveillance data in Singapore, 1996 -2003

Annual influenza viruses and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) surveillance data in Singapore, 1996 -2003

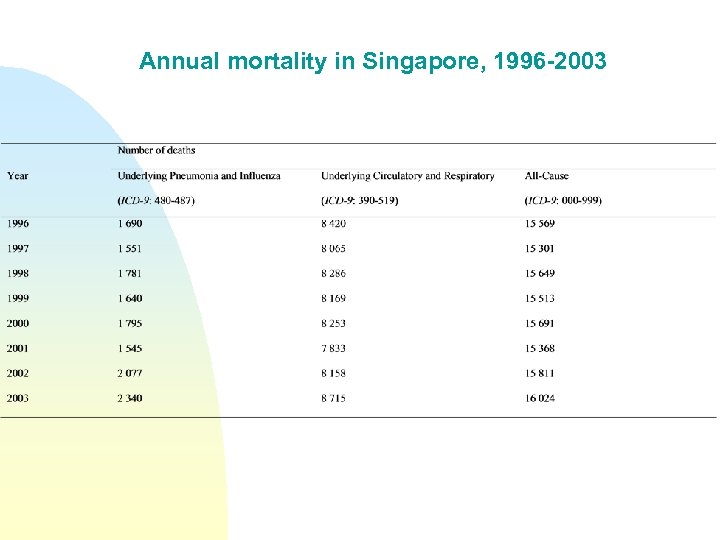

Annual mortality in Singapore, 1996 -2003

Annual mortality in Singapore, 1996 -2003

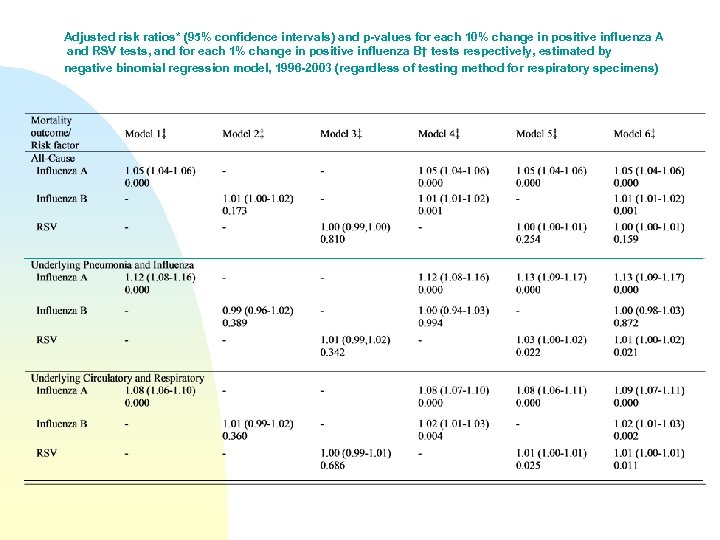

Adjusted risk ratios* (95% confidence intervals) and p-values for each 10% change in positive influenza A and RSV tests, and for each 1% change in positive influenza B† tests respectively, estimated by negative binomial regression model, 1996 -2003 (regardless of testing method for respiratory specimens)

Adjusted risk ratios* (95% confidence intervals) and p-values for each 10% change in positive influenza A and RSV tests, and for each 1% change in positive influenza B† tests respectively, estimated by negative binomial regression model, 1996 -2003 (regardless of testing method for respiratory specimens)

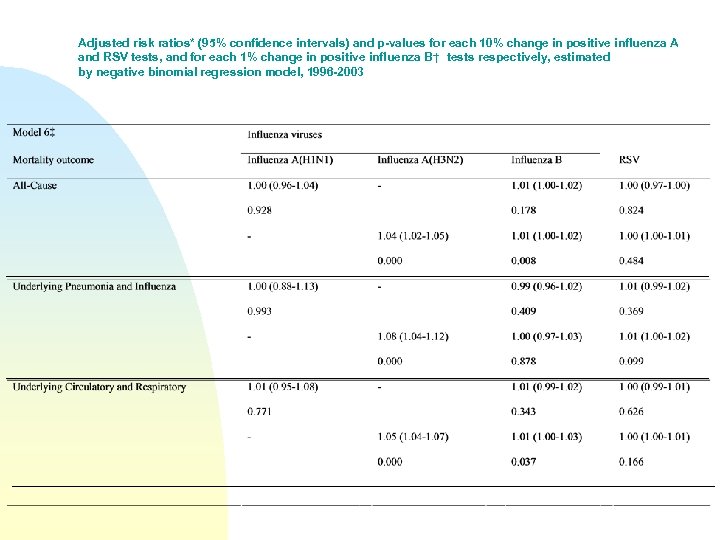

Adjusted risk ratios* (95% confidence intervals) and p-values for each 10% change in positive influenza A and RSV tests, and for each 1% change in positive influenza B† tests respectively, estimated by negative binomial regression model, 1996 -2003

Adjusted risk ratios* (95% confidence intervals) and p-values for each 10% change in positive influenza A and RSV tests, and for each 1% change in positive influenza B† tests respectively, estimated by negative binomial regression model, 1996 -2003

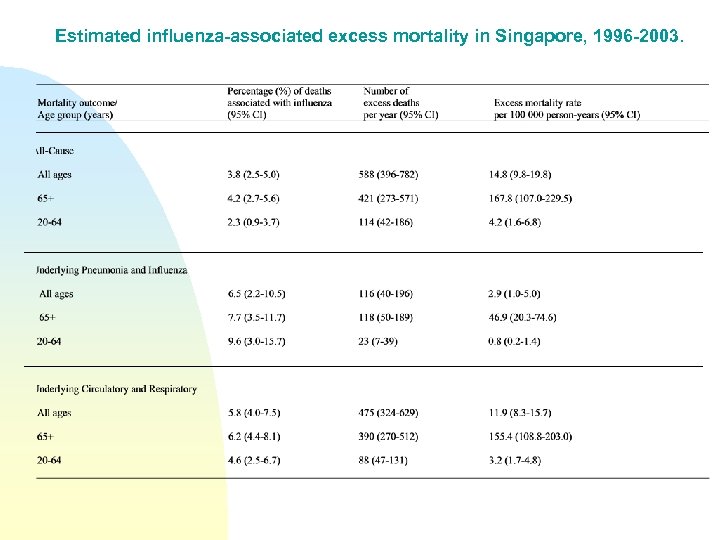

Estimated influenza-associated excess mortality in Singapore, 1996 -2003.

Estimated influenza-associated excess mortality in Singapore, 1996 -2003.

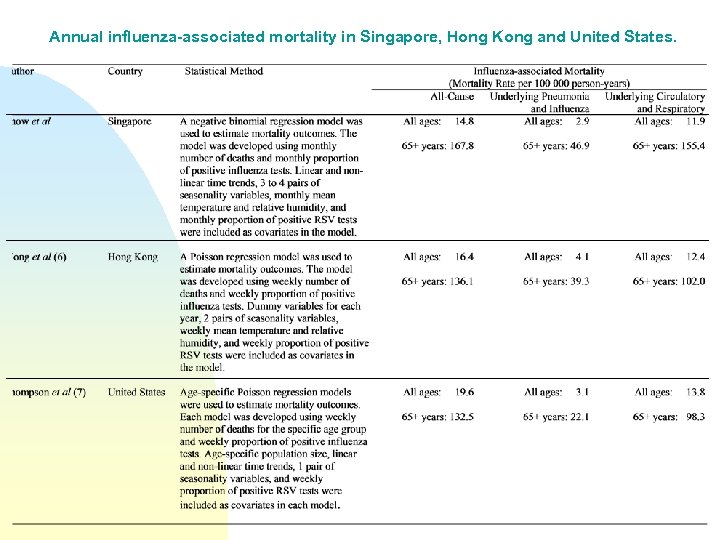

Annual influenza-associated mortality in Singapore, Hong Kong and United States.

Annual influenza-associated mortality in Singapore, Hong Kong and United States.

Summary of the findings n n Influenza A (H 3 N 2) was the predominant circulating influenza virus subtype, with consistently significant and robust effect on mortality. Influenza was associated with an annual mortality from all causes, from underlying P&I, and from underlying C&R conditions of 14. 8 (95% confidence interval 9. 8– 19. 8), 2. 9 (1. 0– 5. 0), and 11. 9 (8. 3– 15. 7) per 100, 000 person-years, respectively. These results are comparable with observations in the United States and subtropical Hong Kong. An estimated 6. 5% of underlying P&I deaths was attributable to influenza. The proportion of influenzaassociated mortality was 11. 3 times higher in persons age >65 years than in the general population

Summary of the findings n n Influenza A (H 3 N 2) was the predominant circulating influenza virus subtype, with consistently significant and robust effect on mortality. Influenza was associated with an annual mortality from all causes, from underlying P&I, and from underlying C&R conditions of 14. 8 (95% confidence interval 9. 8– 19. 8), 2. 9 (1. 0– 5. 0), and 11. 9 (8. 3– 15. 7) per 100, 000 person-years, respectively. These results are comparable with observations in the United States and subtropical Hong Kong. An estimated 6. 5% of underlying P&I deaths was attributable to influenza. The proportion of influenzaassociated mortality was 11. 3 times higher in persons age >65 years than in the general population

Conclusions n n n Time-series regression approach is a good alternative compared with two current methods. In our study, significant burden associated with influenza activities was showed using this alternative approach. Our findings support the need for influenza surveillance and annual influenza vaccination for at risk population in tropical countries

Conclusions n n n Time-series regression approach is a good alternative compared with two current methods. In our study, significant burden associated with influenza activities was showed using this alternative approach. Our findings support the need for influenza surveillance and annual influenza vaccination for at risk population in tropical countries

Thank You

Thank You