4f7906959ae10b1f9341c63b3fa23066.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 106

Mobility, Security, and Proof-Carrying Code Peter Lee Carnegie Mellon University Lecture 4 July 13, 2001 LF, Oracle Strings, and Proof Tools Lipari School on Foundations of Wide Area Network Programming

“Applets, Not Craplets” A Demo

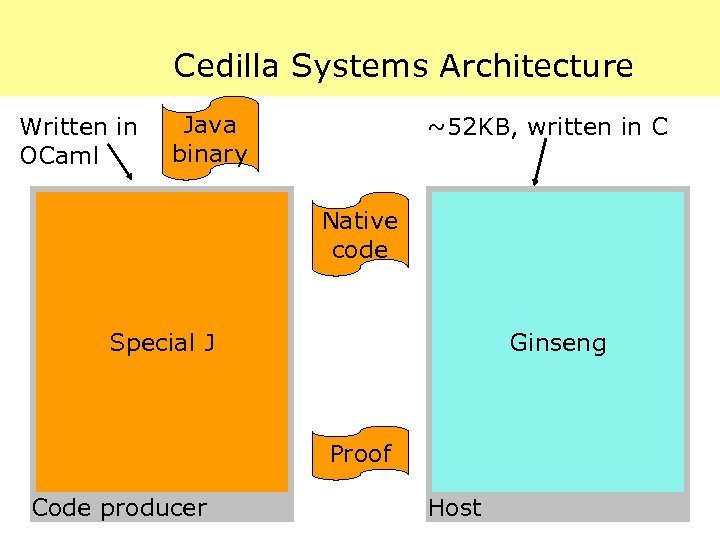

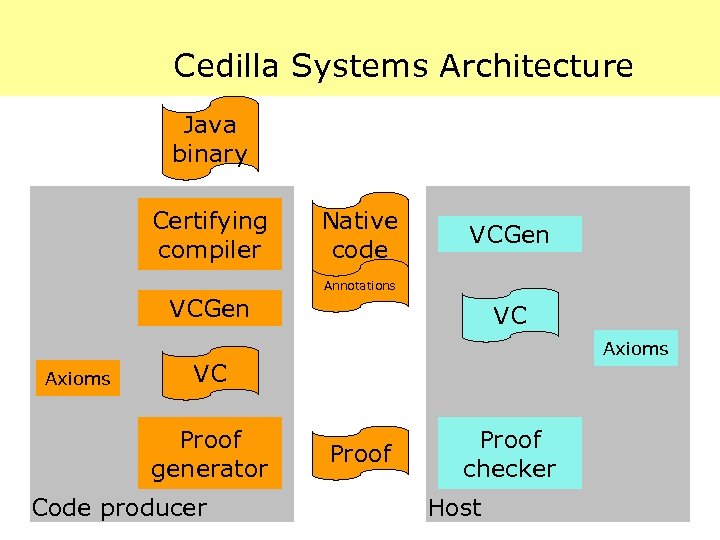

Cedilla Systems Architecture Written in OCaml Java binary ~52 KB, written in C Native code Special J Ginseng Proof Code producer Host

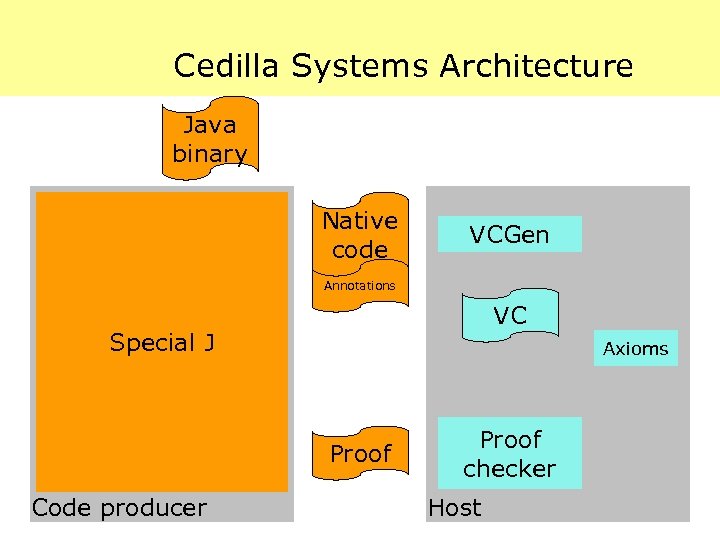

Cedilla Systems Architecture Java binary Native code VCGen Annotations VC Special J Axioms Proof Code producer Proof checker Host

Cedilla Systems Architecture Java binary Certifying compiler Native code VCGen Annotations VCGen Axioms VC Proof generator Code producer Proof checker Host

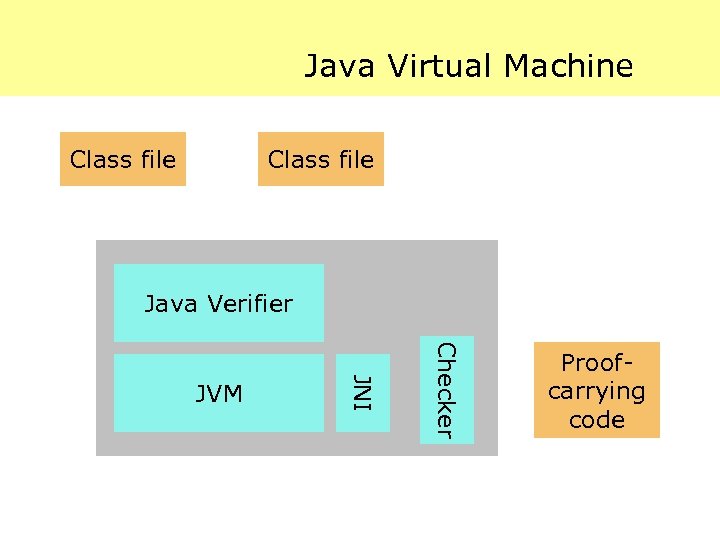

Java Virtual Machine Class file Java Verifier Checker JNI JVM Proof. Native carrying code

Show either the Mandelbrot or NBody 3 D demo.

![Crypto Test Suite Results [Cedilla Systems] sec On average, 158% faster than Java, 72. Crypto Test Suite Results [Cedilla Systems] sec On average, 158% faster than Java, 72.](https://present5.com/presentation/4f7906959ae10b1f9341c63b3fa23066/image-8.jpg)

Crypto Test Suite Results [Cedilla Systems] sec On average, 158% faster than Java, 72. 8% faster than Java with a JIT.

![Java Grande Suite v 2. 0 [Cedilla Systems] sec Java Grande Suite v 2. 0 [Cedilla Systems] sec](https://present5.com/presentation/4f7906959ae10b1f9341c63b3fa23066/image-9.jpg)

Java Grande Suite v 2. 0 [Cedilla Systems] sec

![Java Grande Bench Suite [Cedilla Systems] ops Java Grande Bench Suite [Cedilla Systems] ops](https://present5.com/presentation/4f7906959ae10b1f9341c63b3fa23066/image-10.jpg)

Java Grande Bench Suite [Cedilla Systems] ops

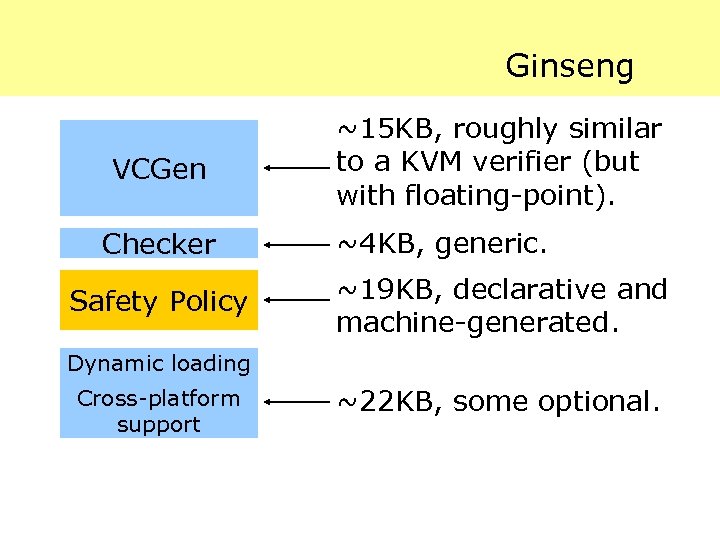

Ginseng VCGen Checker Safety Policy ~15 KB, roughly similar to a KVM verifier (but with floating-point). ~4 KB, generic. ~19 KB, declarative and machine-generated. Dynamic loading Cross-platform support ~22 KB, some optional.

Practical Considerations

Trusted Computing Base The trusted computing base is the software infrastructure that is responsible for ensuring that only safe execution is possible. Obviously, any bugs in the TCB can lead to unsafe execution. Thus, we want the TCB to be simple, as well as fast and small.

VCGen’s Complexity Fortunately, we shall see that proofchecking can be quite simple, small, and fast. VCGen, at core, is also simple and fast. But in practice it gets to be quite complicated.

VCGen’s Complexity Some complications: · If dealing with machine code, then VCGen must parse machine code. · Maintaining the assumptions and current context in a memoryefficient manner is not easy. Note that Sun’s k. VM does verification in a single pass and only 8 KB RAM!

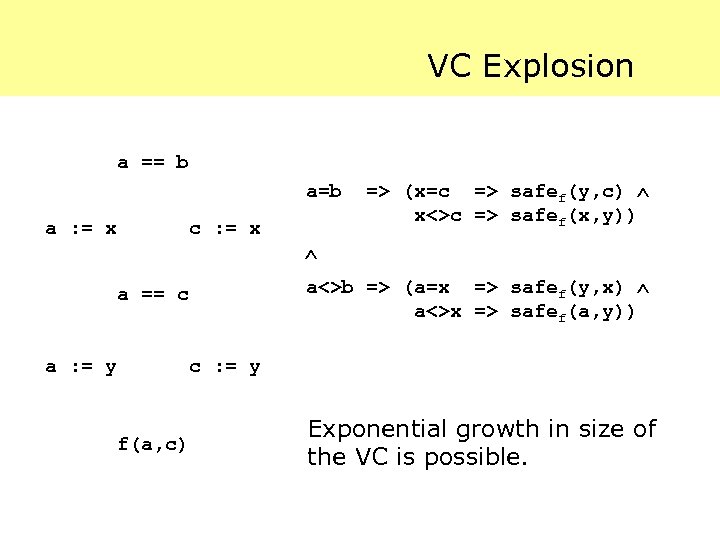

VC Explosion a == b a=b a : = x c : = x f(a, c) a<>b => (a=x => safef(y, x) a<>x => safef(a, y)) a == c a : = y => (x=c => safef(y, c) x<>c => safef(x, y)) c : = y Exponential growth in size of the VC is possible.

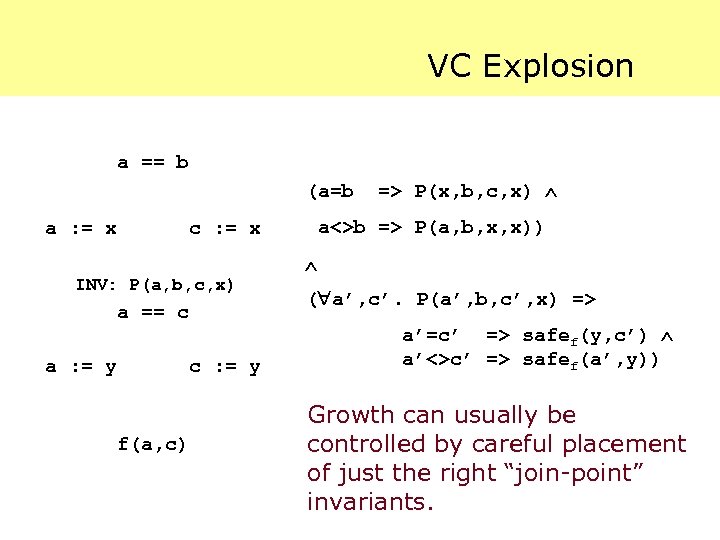

VC Explosion a == b (a=b a : = x c : = x INV: P(a, b, c, x) a == c a : = y f(a, c) c : = y => P(x, b, c, x) a<>b => P(a, b, x, x)) ( a’, c’. P(a’, b, c’, x) => a’=c’ => safef(y, c’) a’<>c’ => safef(a’, y)) Growth can usually be controlled by careful placement of just the right “join-point” invariants.

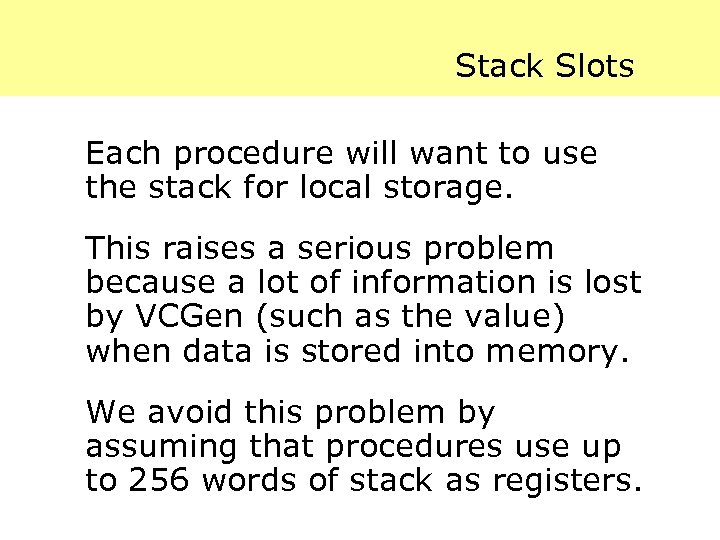

Stack Slots Each procedure will want to use the stack for local storage. This raises a serious problem because a lot of information is lost by VCGen (such as the value) when data is stored into memory. We avoid this problem by assuming that procedures use up to 256 words of stack as registers.

Exercise 8. Just as with loop invariants, our actual join-point invariants includes a specification of the registers that might be modified since the dominating block. Why might this be a useful thing to do? Why might it be a bad thing to do?

Callee-save Registers Standard calling conventions dictate that the contents of some registers be preserved. These callee-save registers are specified along with the pre/postconditions for each procedure. The preservation of their values must be verified at every return instruction.

Introduction to Efficient Representation and Validation of Proofs

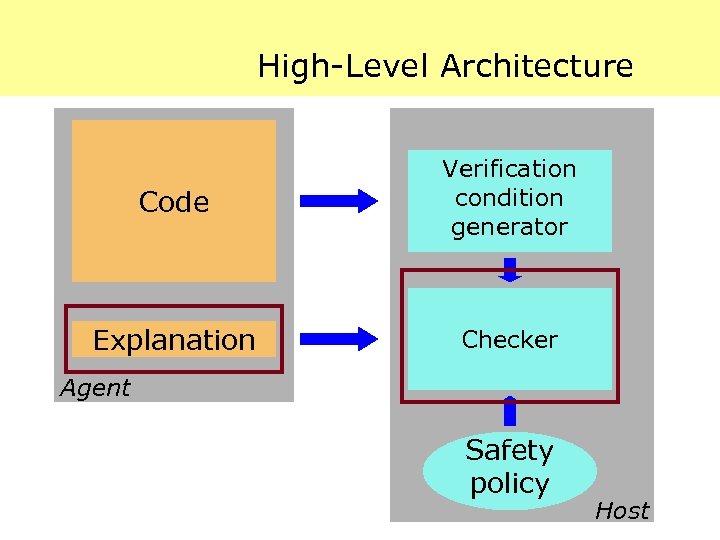

High-Level Architecture Code Verification condition generator Explanation Checker Agent Safety policy Host

Goals We would like a representation for proofs that is · compact, · fast to check, · requires very little memory to check, · and is “canonical” (in the sense of accommodating many different logics without requiring a total reimplementation of the checker).

Three Approaches 1. Direct representation of a logic. 2. Use of a Logical Framework. 3. Oracle strings. We will reject (1). Today we introduce (2) and (3).

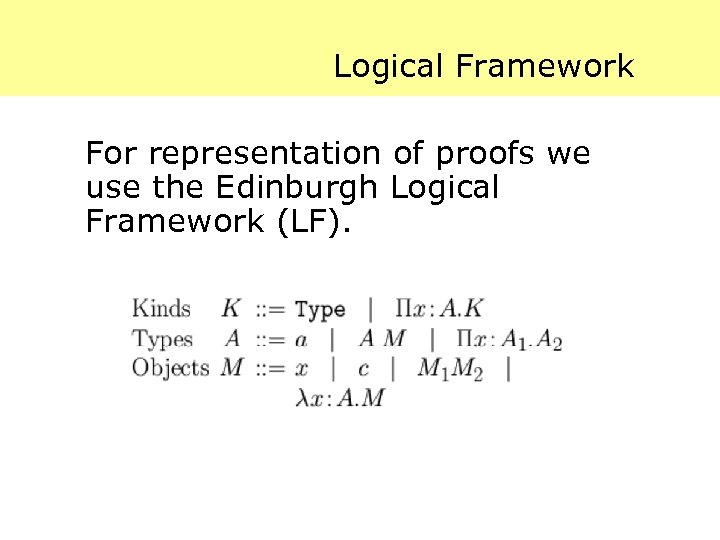

Logical Framework For representation of proofs we use the Edinburgh Logical Framework (LF).

Reynolds’ Example Skip?

Formal Proofs Write “x is a proof of P” as x: P. Examples of predicates P: · (for all A, B) A and B => B and A · (for all x, y, z) x < y and y < z => x<z What do the proofs look like?

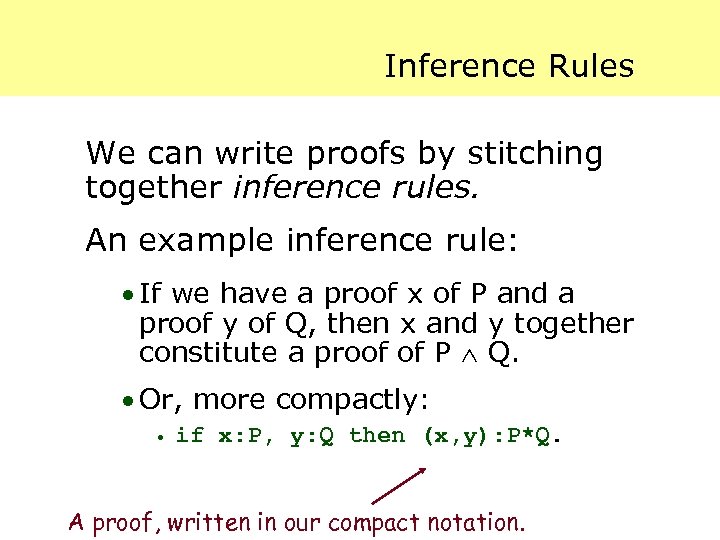

Inference Rules We can write proofs by stitching together inference rules. An example inference rule: · If we have a proof x of P and a proof y of Q, then x and y together constitute a proof of P Q. · Or, more compactly: · if x: P, y: Q then (x, y): P*Q. A proof, written in our compact notation.

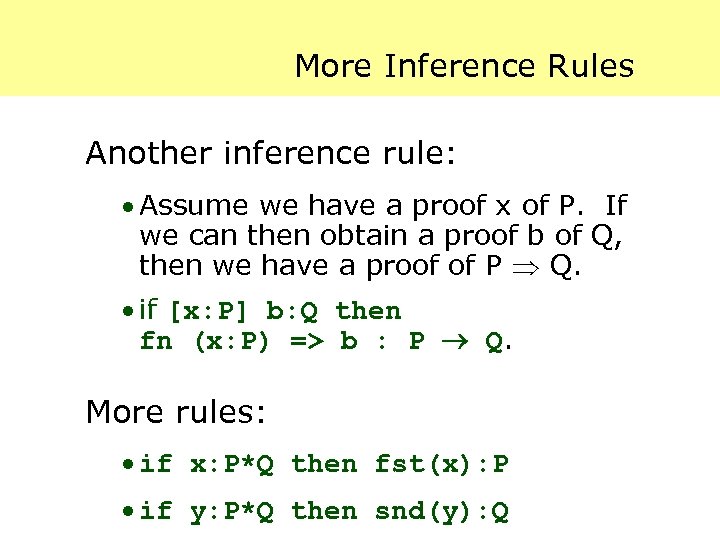

More Inference Rules Another inference rule: · Assume we have a proof x of P. If we can then obtain a proof b of Q, then we have a proof of P Q. · if [x: P] b: Q then fn (x: P) => b : P Q. More rules: · if x: P*Q then fst(x): P · if y: P*Q then snd(y): Q

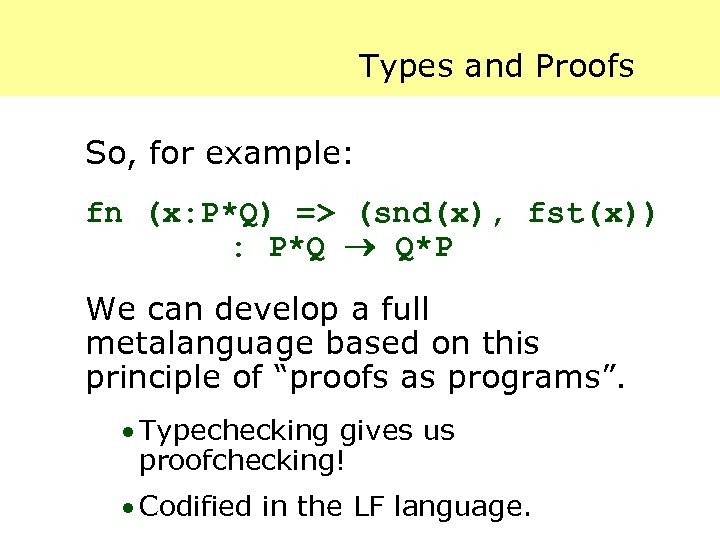

Types and Proofs So, for example: fn (x: P*Q) => (snd(x), fst(x)) : P*Q Q*P We can develop a full metalanguage based on this principle of “proofs as programs”. · Typechecking gives us proofchecking! · Codified in the LF language.

LFi Skip?

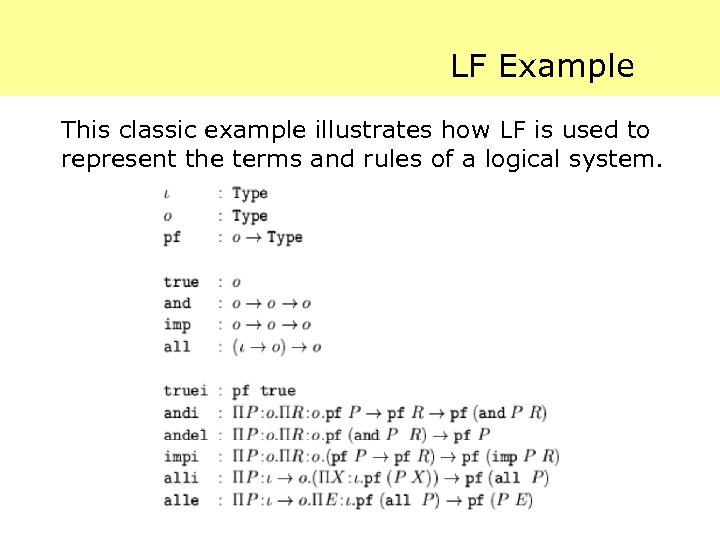

LF Example This classic example illustrates how LF is used to represent the terms and rules of a logical system.

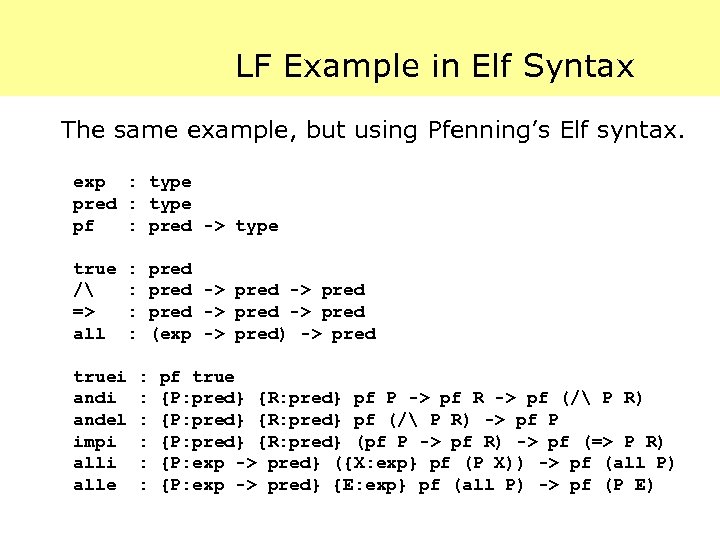

LF Example in Elf Syntax The same example, but using Pfenning’s Elf syntax. exp : type pred : type pf : pred -> type true / => all : : truei andel impi alle pred -> pred (exp -> pred) -> pred : : : pf true {P: pred} {R: pred} pf P -> pf R -> pf (/ P R) {P: pred} {R: pred} pf (/ P R) -> pf P {P: pred} {R: pred} (pf P -> pf R) -> pf (=> P R) {P: exp -> pred} ({X: exp} pf (P X)) -> pf (all P) {P: exp -> pred} {E: exp} pf (all P) -> pf (P E)

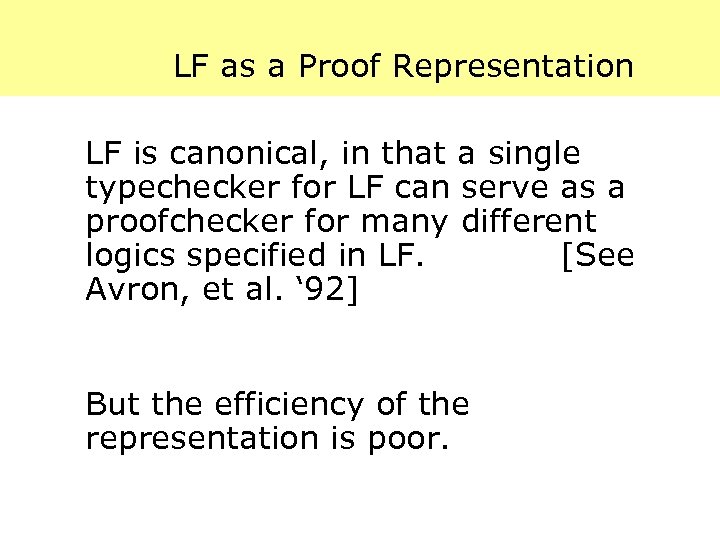

LF as a Proof Representation LF is canonical, in that a single typechecker for LF can serve as a proofchecker for many different logics specified in LF. [See Avron, et al. ‘ 92] But the efficiency of the representation is poor.

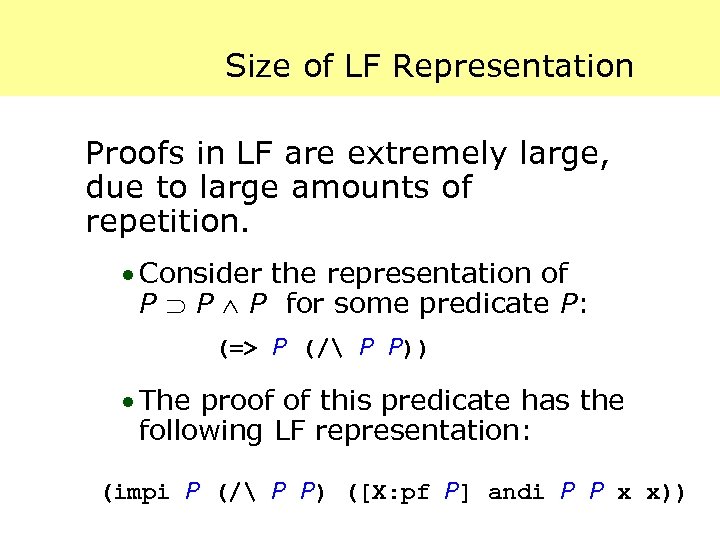

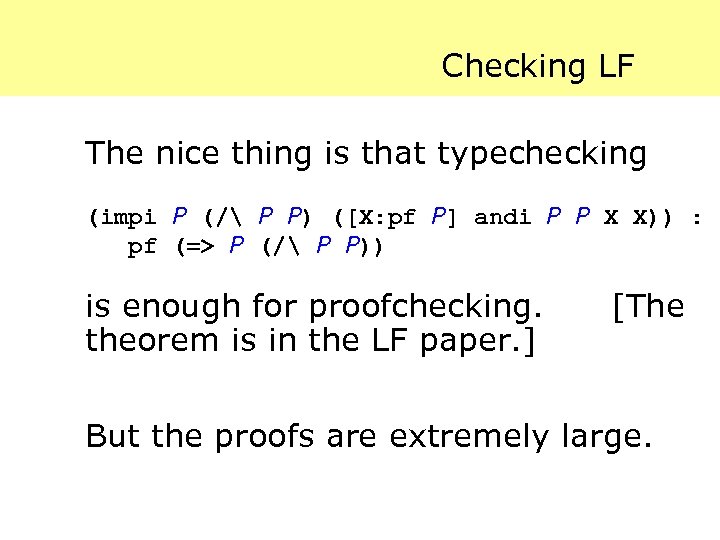

Size of LF Representation Proofs in LF are extremely large, due to large amounts of repetition. · Consider the representation of P P P for some predicate P: (=> P (/ P P)) · The proof of this predicate has the following LF representation: (impi P (/ P P) ([X: pf P] andi P P x x))

Checking LF The nice thing is that typechecking (impi P (/ P P) ([X: pf P] andi P P X X)) : pf (=> P (/ P P)) is enough for proofchecking. theorem is in the LF paper. ] [The But the proofs are extremely large.

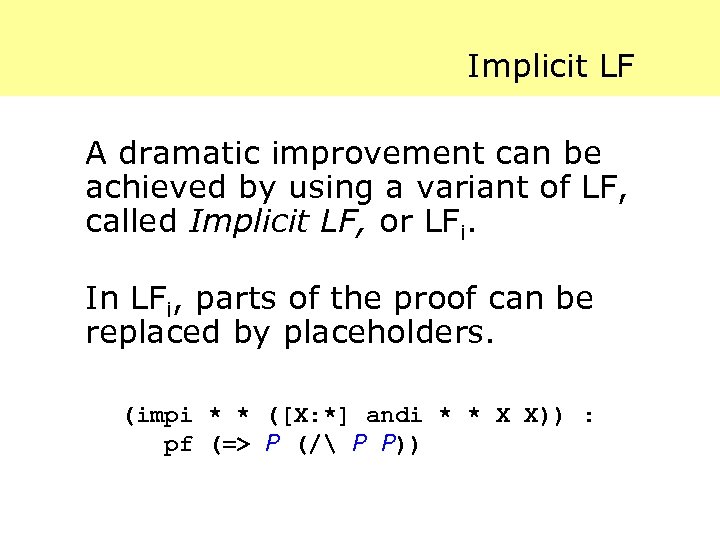

Implicit LF A dramatic improvement can be achieved by using a variant of LF, called Implicit LF, or LFi. In LFi, parts of the proof can be replaced by placeholders. (impi * * ([X: *] andi * * X X)) : pf (=> P (/ P P))

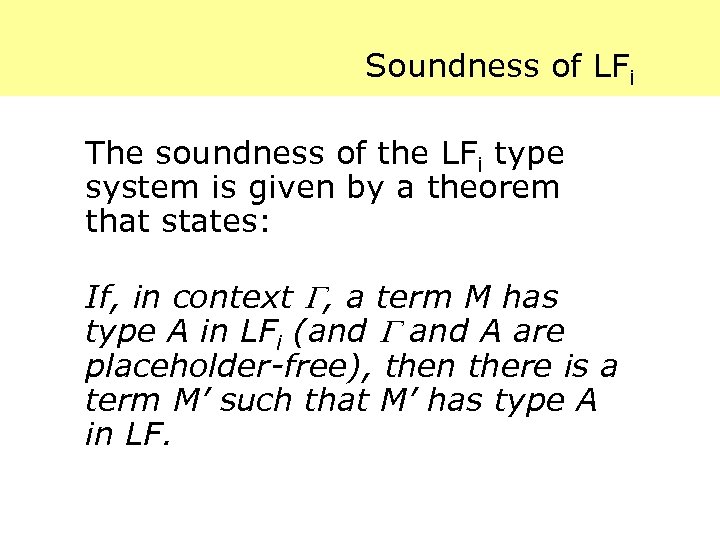

Soundness of LFi The soundness of the LFi type system is given by a theorem that states: If, in context , a term M has type A in LFi (and A are placeholder-free), then there is a term M’ such that M’ has type A in LF.

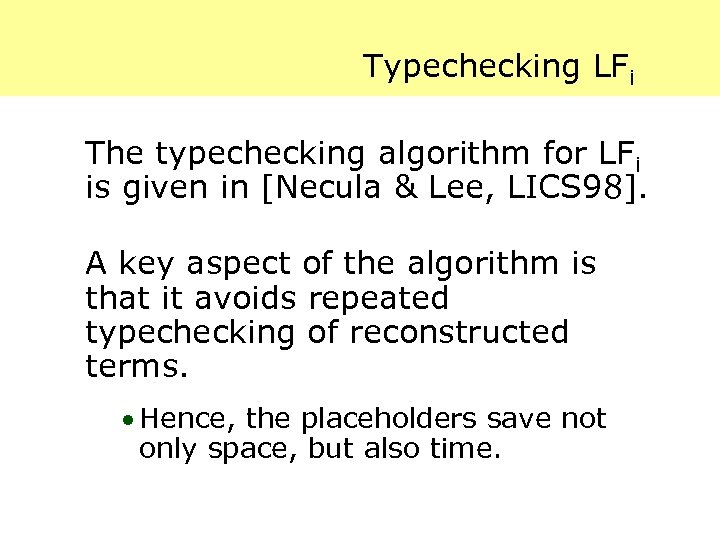

Typechecking LFi The typechecking algorithm for LFi is given in [Necula & Lee, LICS 98]. A key aspect of the algorithm is that it avoids repeated typechecking of reconstructed terms. · Hence, the placeholders save not only space, but also time.

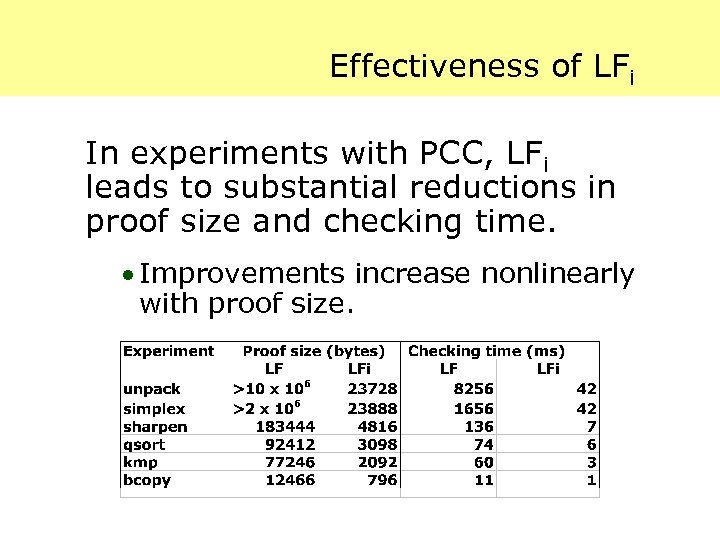

Effectiveness of LFi In experiments with PCC, LFi leads to substantial reductions in proof size and checking time. · Improvements increase nonlinearly with proof size.

The Need for Improvement Despite the great improvement of LFi, in our experiments we observe that LFi proofs are 10%200% the size of the code.

How Big is a Proof? A basic question is how much essential information is in a proof? In this proof, (impi * * ([X: *] andi * * x x)) : pf (=> P (/ P P)) there are only 2 uses of rules and in each case they were the only rule that could have been used.

Improving the Representation We will now improve on the compactness of proof representation by making use of the observation that large parts of proofs are deterministically generated from the inference rules.

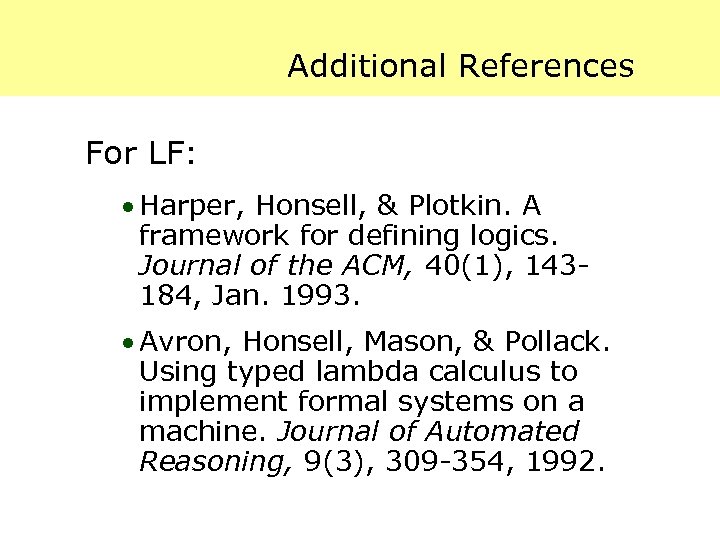

Additional References For LF: · Harper, Honsell, & Plotkin. A framework for defining logics. Journal of the ACM, 40(1), 143184, Jan. 1993. · Avron, Honsell, Mason, & Pollack. Using typed lambda calculus to implement formal systems on a machine. Journal of Automated Reasoning, 9(3), 309 -354, 1992.

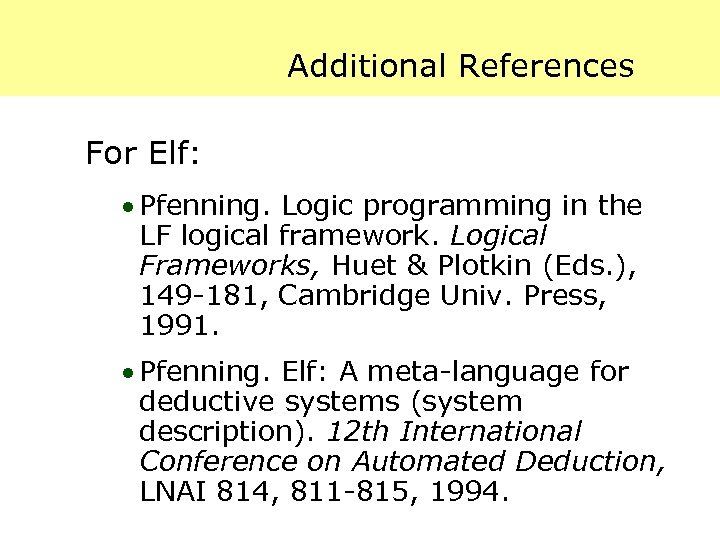

Additional References For Elf: · Pfenning. Logic programming in the LF logical framework. Logical Frameworks, Huet & Plotkin (Eds. ), 149 -181, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1991. · Pfenning. Elf: A meta-language for deductive systems (system description). 12 th International Conference on Automated Deduction, LNAI 814, 811 -815, 1994.

Oracle-Based Checking

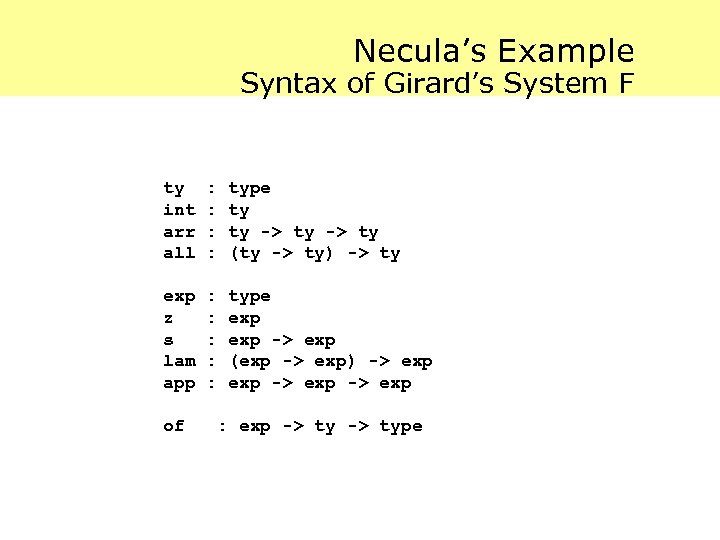

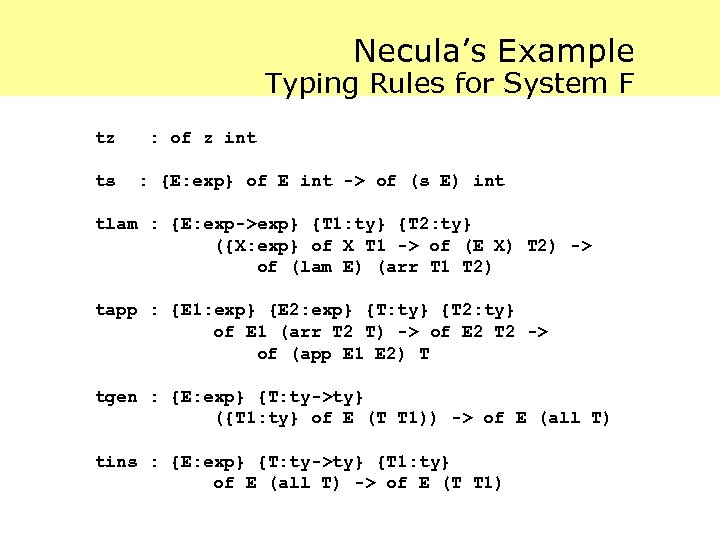

Necula’s Example Syntax of Girard’s System F ty int arr all : : type ty ty -> ty (ty -> ty) -> ty exp z s lam app : : : type exp -> exp (exp -> exp) -> exp of : exp -> type

Necula’s Example Typing Rules for System F tz ts : of z int : {E: exp} of E int -> of (s E) int tlam : {E: exp->exp} {T 1: ty} {T 2: ty} ({X: exp} of X T 1 -> of (E X) T 2) -> of (lam E) (arr T 1 T 2) tapp : {E 1: exp} {E 2: exp} {T: ty} {T 2: ty} of E 1 (arr T 2 T) -> of E 2 T 2 -> of (app E 1 E 2) T tgen : {E: exp} {T: ty->ty} ({T 1: ty} of E (T T 1)) -> of E (all T) tins : {E: exp} {T: ty->ty} {T 1: ty} of E (all T) -> of E (T T 1)

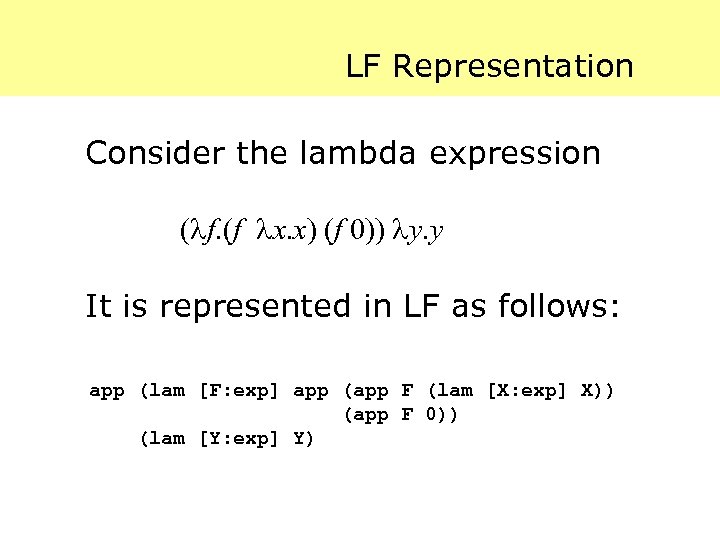

LF Representation Consider the lambda expression ( f. (f x. x) (f 0)) y. y It is represented in LF as follows: app (lam [F: exp] app (app F (lam [X: exp] X)) (app F 0)) (lam [Y: exp] Y)

Necula’s Example Now suppose that this term is an applet, with the safety policy that all applets must be well-typed in System F. One way to make a PCC is to attach a typing derivation to the term.

![Typing Derivation in LF (tapp (lam [F: exp] (app F (lam [X: exp] X)) Typing Derivation in LF (tapp (lam [F: exp] (app F (lam [X: exp] X))](https://present5.com/presentation/4f7906959ae10b1f9341c63b3fa23066/image-51.jpg)

Typing Derivation in LF (tapp (lam [F: exp] (app F (lam [X: exp] X)) (app F 0))) (lam ([X: exp] X)) (all ([T: ty] arr T T)) int (tlam (all ([T: ty] arr T T)) int ([F: exp] (app F (lam [X: exp] X)) (app F 0))) ([F: exp][FT: of F (all ([T: ty] arr T T))] (tapp (app F (lam [X: exp] X)) (app F 0) int (tapp F (lam [X: exp] X) (arr int int) (tins F ([T: ty] arr T T) (arr int) FT) (tlam int ([X: exp] X) ([X: exp][XT: of X int] XT))) (tapp F 0 int (tins F ([T: ty] arr T T) int FT) t 0)))) (tgen (lam [Y: exp] Y) ([T: ty] arr T T) ([T: ty] (tlam T T ([Y: exp] Y) ([Y: exp] [YT: of Y T] YT)))))

![Typing Derivation in LFi (tapp * * (all ([T: *] arr T T)) int Typing Derivation in LFi (tapp * * (all ([T: *] arr T T)) int](https://present5.com/presentation/4f7906959ae10b1f9341c63b3fa23066/image-52.jpg)

Typing Derivation in LFi (tapp * * (all ([T: *] arr T T)) int (tlam * * * ([F: *][FT: of F (all ([T: ty] arr T T))] (tapp * * int (tapp * * (arr int int) (tins * * * FT) (tlam * * * ([X: *][XT: *] XT))) (tapp * * int (tins * * * FT) t 0)))) (tgen * * ([T: *] (tlam * * * ([Y: *] [YT: *] YT))))) I think. I did this by hand!

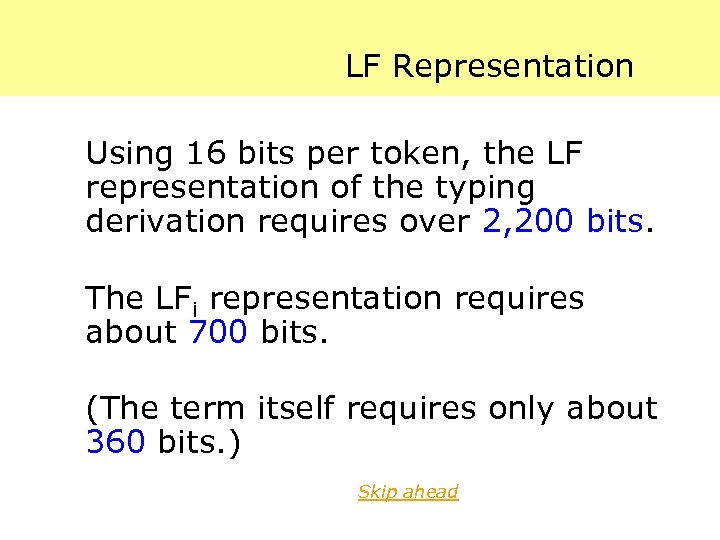

LF Representation Using 16 bits per token, the LF representation of the typing derivation requires over 2, 200 bits. The LFi representation requires about 700 bits. (The term itself requires only about 360 bits. ) Skip ahead

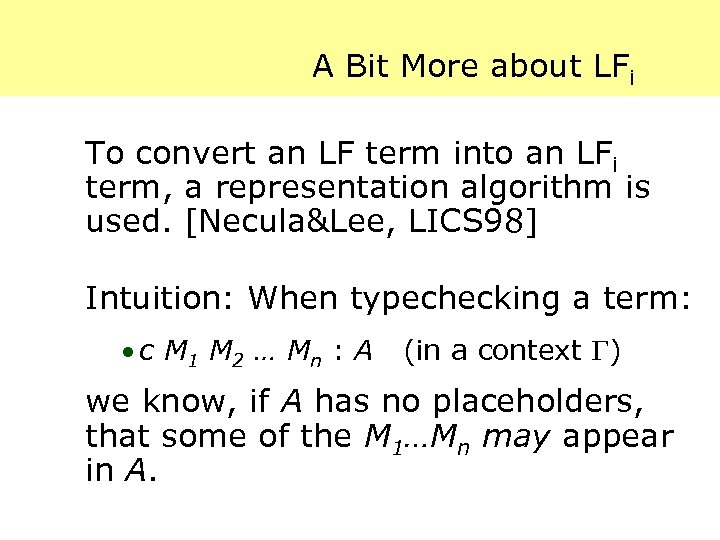

A Bit More about LFi To convert an LF term into an LFi term, a representation algorithm is used. [Necula&Lee, LICS 98] Intuition: When typechecking a term: · c M 1 M 2 … Mn : A (in a context ) we know, if A has no placeholders, that some of the M 1…Mn may appear in A.

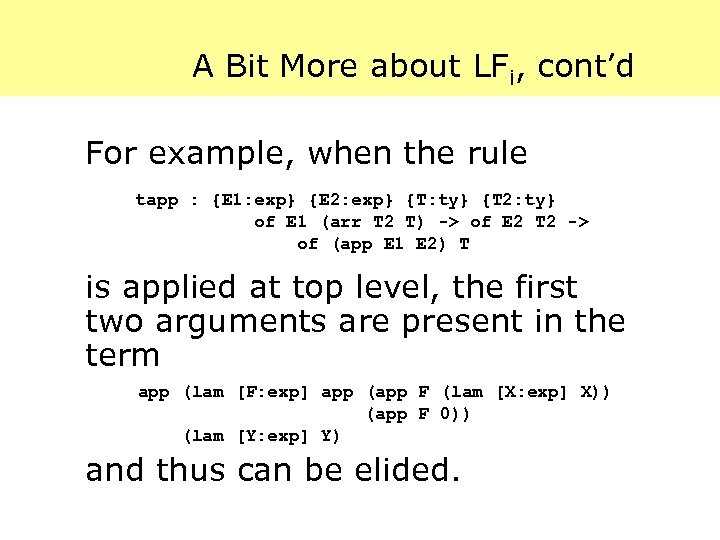

A Bit More about LFi, cont’d For example, when the rule tapp : {E 1: exp} {E 2: exp} {T: ty} {T 2: ty} of E 1 (arr T 2 T) -> of E 2 T 2 -> of (app E 1 E 2) T is applied at top level, the first two arguments are present in the term app (lam [F: exp] app (app F (lam [X: exp] X)) (app F 0)) (lam [Y: exp] Y) and thus can be elided.

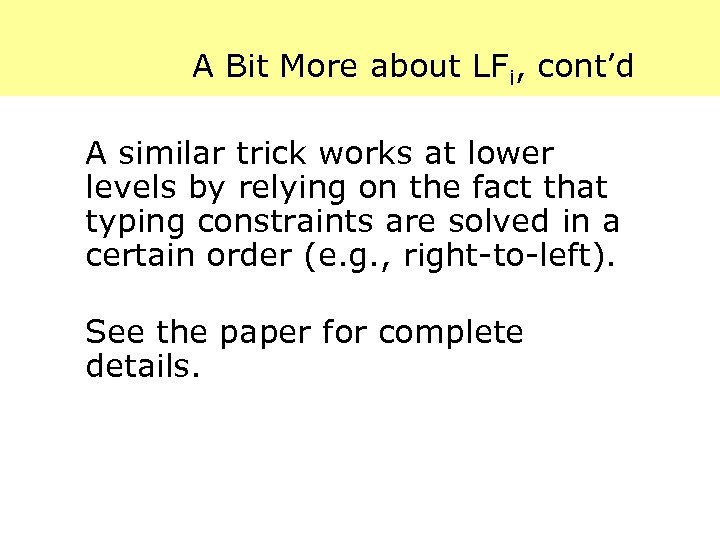

A Bit More about LFi, cont’d A similar trick works at lower levels by relying on the fact that typing constraints are solved in a certain order (e. g. , right-to-left). See the paper for complete details.

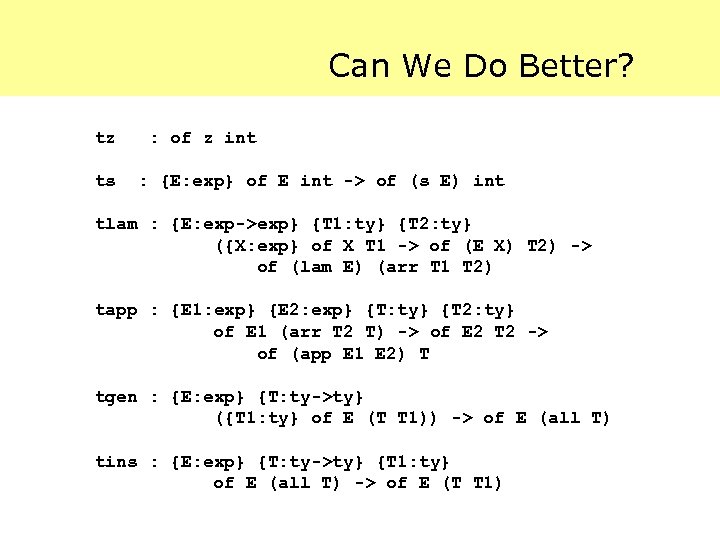

Can We Do Better? tz ts : of z int : {E: exp} of E int -> of (s E) int tlam : {E: exp->exp} {T 1: ty} {T 2: ty} ({X: exp} of X T 1 -> of (E X) T 2) -> of (lam E) (arr T 1 T 2) tapp : {E 1: exp} {E 2: exp} {T: ty} {T 2: ty} of E 1 (arr T 2 T) -> of E 2 T 2 -> of (app E 1 E 2) T tgen : {E: exp} {T: ty->ty} ({T 1: ty} of E (T T 1)) -> of E (all T) tins : {E: exp} {T: ty->ty} {T 1: ty} of E (all T) -> of E (T T 1)

Determinism Looking carefully at the typing rules, we observe: For any typing goal where the term is known but the type is not: · 3 possibilities: tgen, tins, other. If type structure is also known, only 2 choices, tapp or other.

![How Much Essential Information? (tapp (lam [F: exp] (app F (lam [X: exp] X)) How Much Essential Information? (tapp (lam [F: exp] (app F (lam [X: exp] X))](https://present5.com/presentation/4f7906959ae10b1f9341c63b3fa23066/image-59.jpg)

How Much Essential Information? (tapp (lam [F: exp] (app F (lam [X: exp] X)) (app F 0))) (lam ([X: exp] X)) (all ([T: ty] arr T T)) int (tlam (all ([T: ty] arr T T)) int ([F: exp] (app F (lam [X: exp] X)) (app F 0))) ([F: exp][FT: of F (all ([T: ty] arr T T))] (tapp (app F (lam [X: exp] X)) (app F 0) int (tapp F (lam [X: exp] X) (arr int int) (tins F ([T: ty] arr T T) (arr int) FT) (tlam int ([X: exp] X) ([X: exp][XT: of X int] XT))) (tapp F 0 int (tins F ([T: ty] arr T T) int FT) t 0)))) (tgen (lam [Y: exp] Y) ([T: ty] arr T T) ([T: ty] (tlam T T ([Y: exp] Y) ([Y: exp] [YT: of Y T] YT)))))

How Much Essential Information? There are 15 applications of rules in this derivation. So, conservatively: · log 2 3 15 = 30 bits In other words, 30 bits should be enough to encode the choices made by a type inference engine for this term.

Oracle-based Checking Idea: Implement the proofchecker as a nondeterministic logic interpreter whose · program consists of the derivation rules, and · initial goal is the judgment to be verified. We will avoid backtracking by relying on the oracle string. Skip ahead

Why Higher-Order? The syntax of VCs for the Java type-safety policy is as follows: E : : = x | c E 1 … En F : : = true | F 1 F 2 | x. F | E F The LF encodings are simple Horn clauses (and requiring only firstorder unification). Higherorder features only for implication and universal

Why Higher-Order? Perhaps first-order Horn logic (or perhaps first-order hereditary Harrop formulas) is enough. · Indeed, first-order expressions and formulas seem to be enough for the VCs in type-safety policies. However, higher-order and modal logics would require higher-order features.

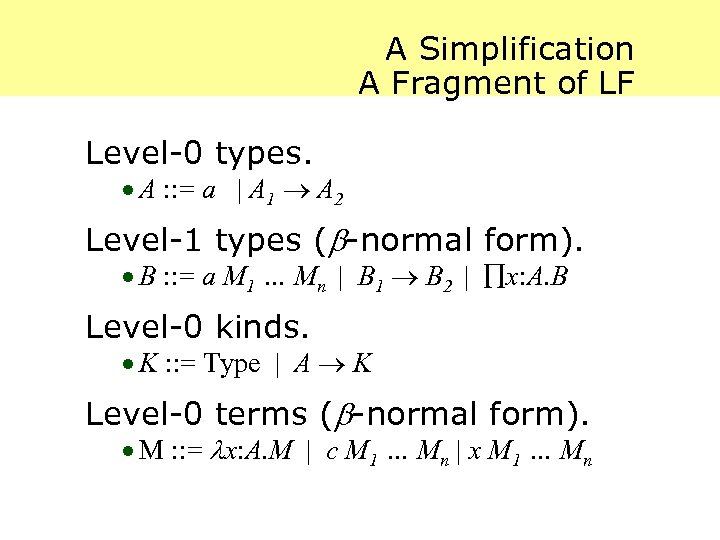

A Simplification A Fragment of LF Level-0 types. · A : : = a | A 1 A 2 Level-1 types ( -normal form). · B : : = a M 1 … Mn | B 1 B 2 | x: A. B Level-0 kinds. · K : : = Type | A K Level-0 terms ( -normal form). · M : : = x: A. M | c M 1 … Mn | x M 1 … Mn

LF Fragment This fragment simplifies matters considerably, without restricting the application to PCC. · Level-0 types to encode syntax. · Level-1 types to encode derivations. No level-1 terms since we never reconstruct a derivation, only verify that one exists!

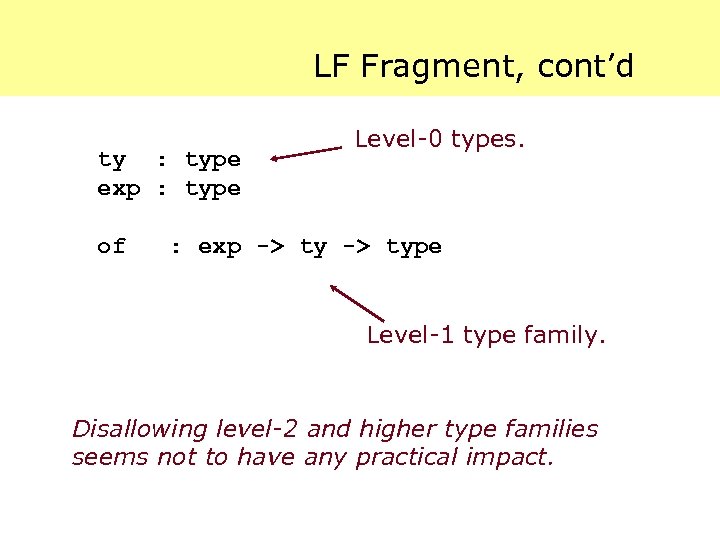

LF Fragment, cont’d ty : type exp : type of Level-0 types. : exp -> type Level-1 type family. Disallowing level-2 and higher type families seems not to have any practical impact.

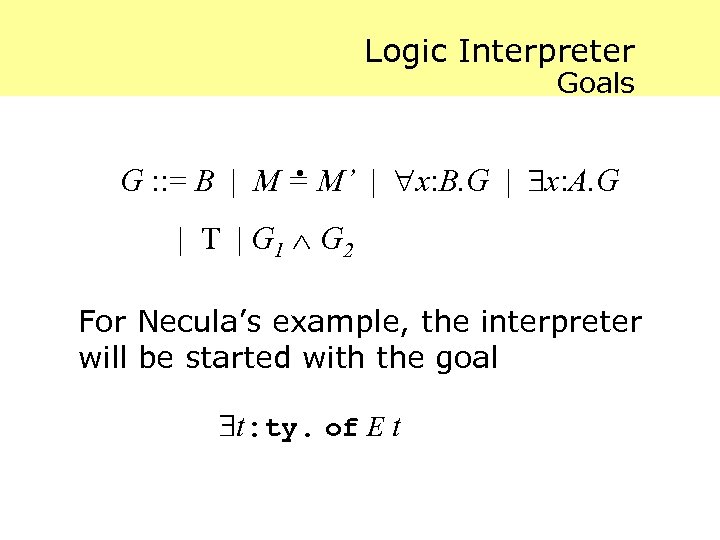

Logic Interpreter Goals . G : : = B | M = M’ | x: B. G | x: A. G | T | G 1 G 2 For Necula’s example, the interpreter will be started with the goal t: ty. of E t

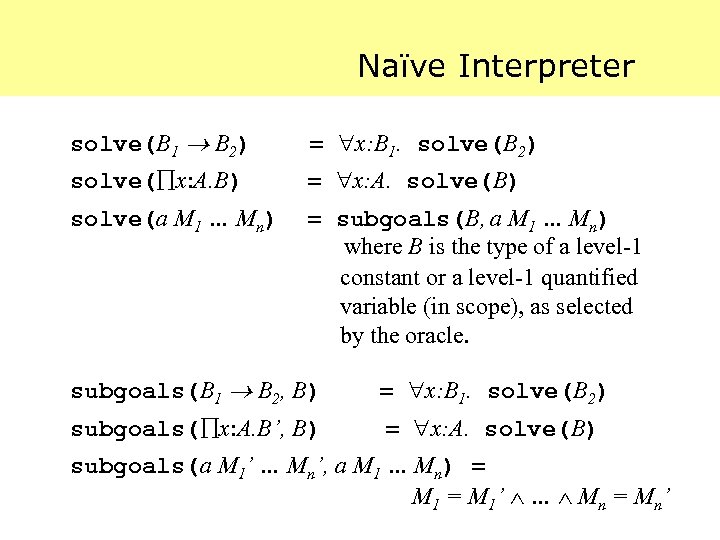

Naïve Interpreter solve(B 1 B 2) = x: B 1. solve(B 2) solve( x: A. B) = x: A. solve(B) solve(a M 1 … Mn) = subgoals(B, a M 1 … Mn) where B is the type of a level-1 constant or a level-1 quantified variable (in scope), as selected by the oracle. subgoals(B 1 B 2, B) = x: B 1. solve(B 2) subgoals( x: A. B’, B) = x: A. solve(B) subgoals(a M 1’ … Mn’, a M 1 … Mn) = M 1’ … Mn = Mn’

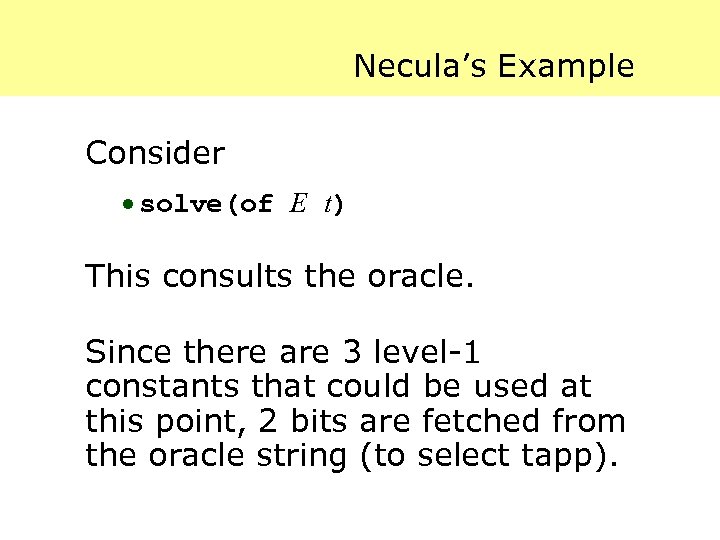

Necula’s Example Consider · solve(of E t) This consults the oracle. Since there are 3 level-1 constants that could be used at this point, 2 bits are fetched from the oracle string (to select tapp).

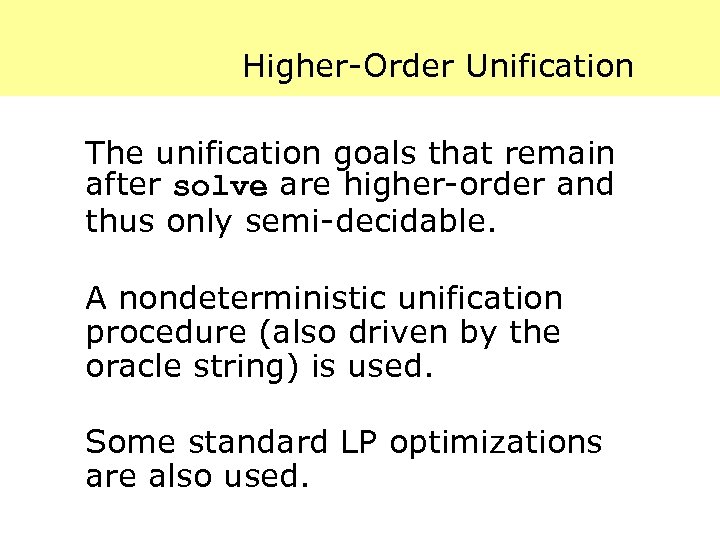

Higher-Order Unification The unification goals that remain after solve are higher-order and thus only semi-decidable. A nondeterministic unification procedure (also driven by the oracle string) is used. Some standard LP optimizations are also used.

Certifying Theorem Proving

Certifying Theorem Proving Time does not allow a description here. See: · Necula and Lee. Proof generation in the Touchstone theorem prover. CADE’ 00. Of particular interest: · Proof-generating congruenceclosure and simplex algorithms.

Certifying Compilation Skip ahead

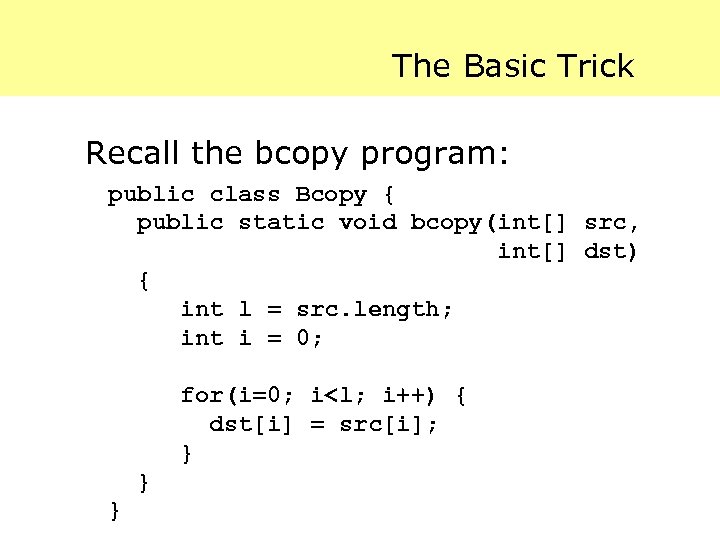

The Basic Trick Recall the bcopy program: public class Bcopy { public static void bcopy(int[] src, int[] dst) { int l = src. length; int i = 0; for(i=0; i<l; i++) { dst[i] = src[i]; } } }

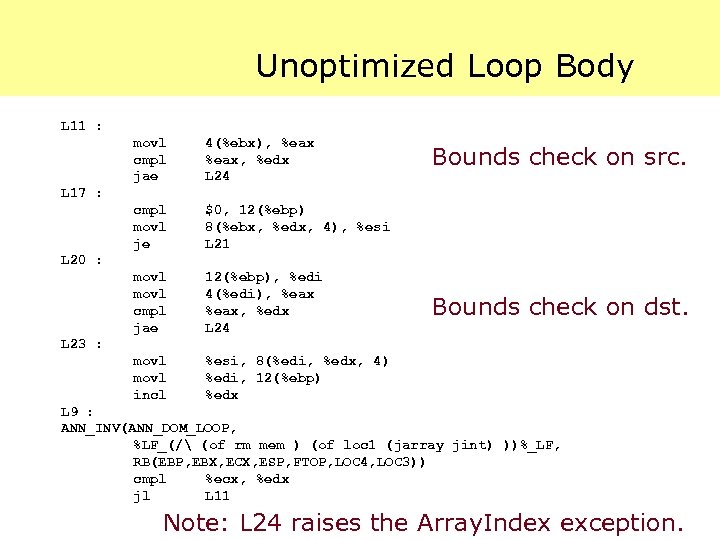

Unoptimized Loop Body L 11 : movl cmpl jae 4(%ebx), %eax, %edx L 24 cmpl movl je $0, 12(%ebp) 8(%ebx, %edx, 4), %esi L 21 movl cmpl jae 12(%ebp), %edi 4(%edi), %eax, %edx L 24 movl incl %esi, 8(%edi, %edx, 4) %edi, 12(%ebp) %edx Bounds check on src. L 17 : L 20 : Bounds check on dst. L 23 : L 9 : ANN_INV(ANN_DOM_LOOP, %LF_(/ (of rm mem ) (of loc 1 (jarray jint) ))%_LF, RB(EBP, EBX, ECX, ESP, FTOP, LOC 4, LOC 3)) cmpl %ecx, %edx jl L 11 Note: L 24 raises the Array. Index exception.

Unoptimized Code is Easy In the absence of optimizations, proving the safety of array accesses is relatively easy. Indeed, in this case it is reasonable for VCGen to verify the safety of the array accesses. As the optimizer becomes more successful, verification gets harder.

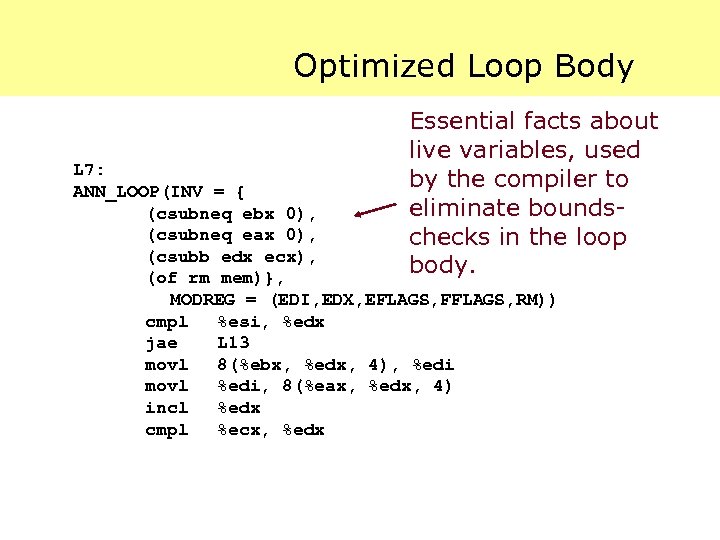

Role of Loop Invariants It is for this reason that the optimizer’s knowledge must be conveyed to theorem prover. Essentially, any facts about program values that were used to perform and code-motion optimizations must be declared in an invariant.

Optimized Loop Body Essential facts about live variables, used by the compiler to eliminate boundschecks in the loop body. L 7: ANN_LOOP(INV = { (csubneq ebx 0), (csubneq eax 0), (csubb edx ecx), (of rm mem)}, MODREG = (EDI, EDX, EFLAGS, FFLAGS, RM)) cmpl %esi, %edx jae L 13 movl 8(%ebx, %edx, 4), %edi movl %edi, 8(%eax, %edx, 4) incl %edx cmpl %ecx, %edx

Certifying Compiling and Proving Intuitively, we will arrange for the Prover to be at least as powerful as the Compiler’s optimizer. Hence, we will expect the Prover to be able to “reverse engineer” the reasoning process that led to the given machine code. An informal concept, needing a formal understanding!

What is Safety, Anyway? If the compiler fails to optimize away a bounds-check, it will insert code to perform the check. This means that programs may still abort at run-time, albeit with a well-defined exception. Is this safe behavior?

Resource Constraints Bounds on certain resources can be enforced via counting. · In a Reference Intepreter: · · Maintain a global counter. Increment the count for each instruction executed. Verify for each instruction that the limit is not exceeded. Use the compiler to optimize away the counting operations.

Compiler as a Theorem-Proving Front-End The compiler is essentially a userinterface to a theorem prover. The possibilities for interactive use of compilers have been described in the literature but not developed very far. PCC may extend the possibilities.

Developing PCC Tools

Compiler Development The PCC infrastructure catches many (probably most) compiler bugs early. Our standard regression test does not execute the object code! Principle: Most compiler bugs show up as safety violations.

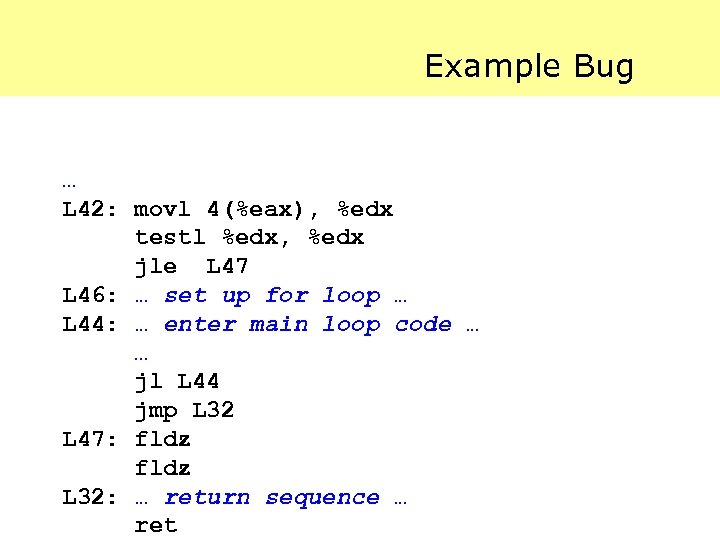

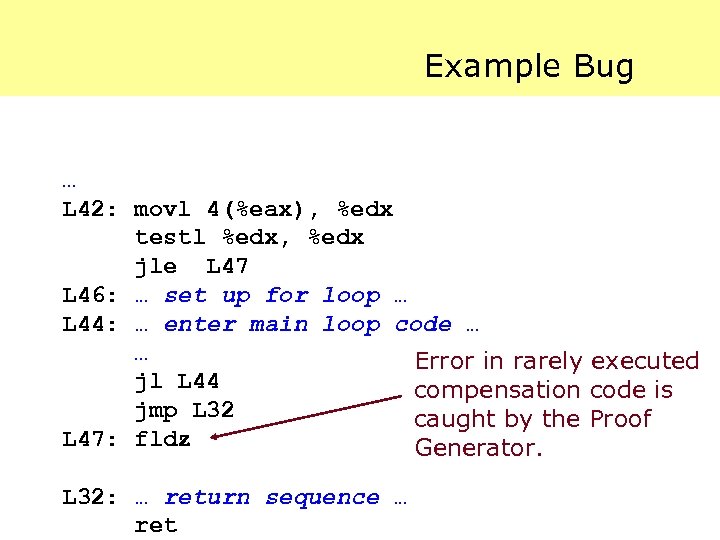

Example Bug … L 42: movl 4(%eax), %edx testl %edx, %edx jle L 47 L 46: … set up for loop … L 44: … enter main loop code … … jl L 44 jmp L 32 L 47: fldz L 32: … return sequence … ret

Example Bug … L 42: movl 4(%eax), %edx testl %edx, %edx jle L 47 L 46: … set up for loop … L 44: … enter main loop code … … Error in rarely executed jl L 44 compensation code is jmp L 32 caught by the Proof L 47: fldz Generator. L 32: … return sequence … ret

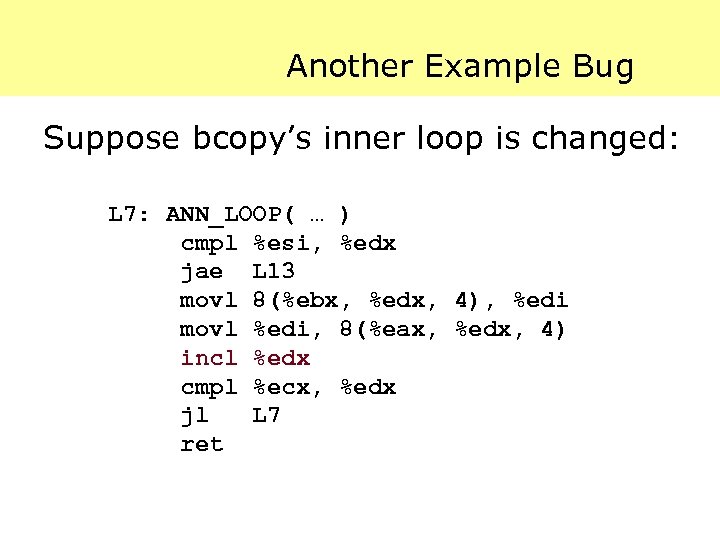

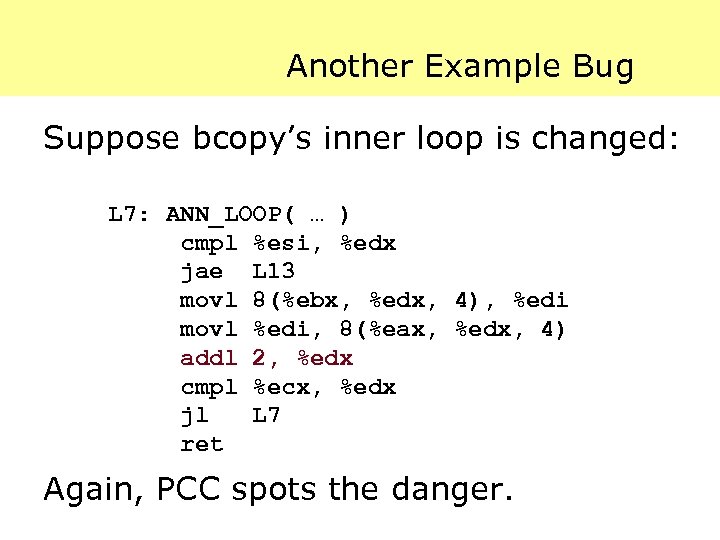

Another Example Bug Suppose bcopy’s inner loop is changed: L 7: ANN_LOOP( … ) cmpl %esi, %edx jae L 13 movl 8(%ebx, %edx, 4), %edi movl %edi, 8(%eax, %edx, 4) incl %edx cmpl %ecx, %edx jl L 7 ret

Another Example Bug Suppose bcopy’s inner loop is changed: L 7: ANN_LOOP( … ) cmpl %esi, %edx jae L 13 movl 8(%ebx, %edx, 4), %edi movl %edi, 8(%eax, %edx, 4) addl 2, %edx cmpl %ecx, %edx jl L 7 ret Again, PCC spots the danger.

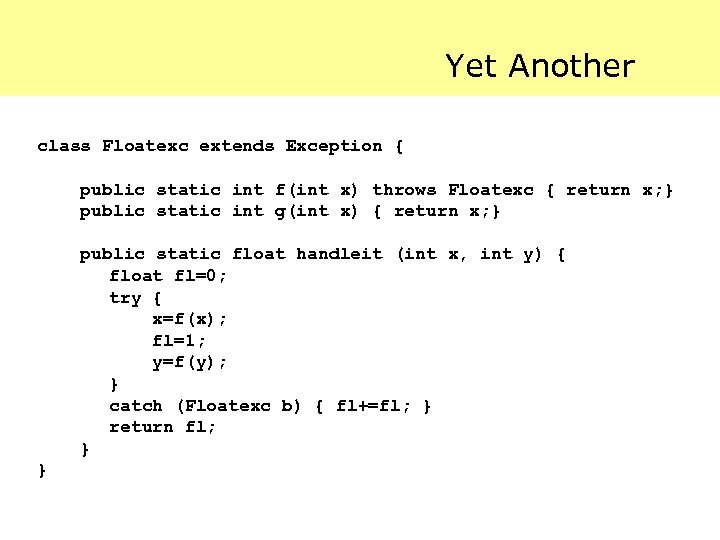

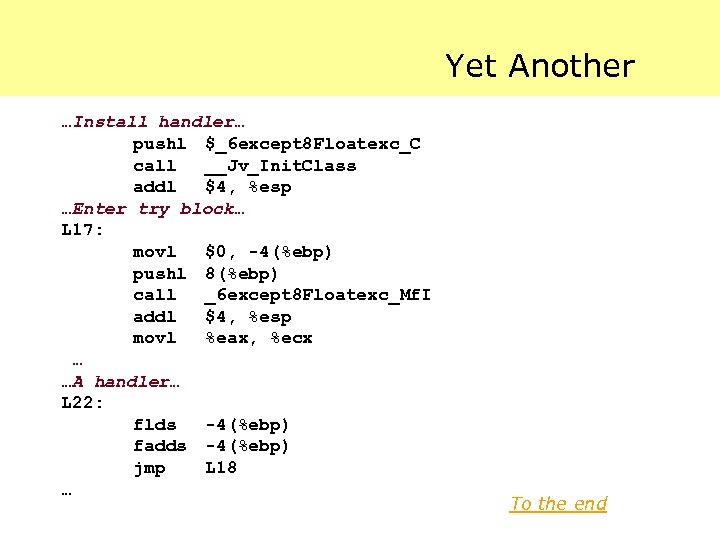

Yet Another class Floatexc extends Exception { public static int f(int x) throws Floatexc { return x; } public static int g(int x) { return x; } public static float handleit (int x, int y) { float fl=0; try { x=f(x); fl=1; y=f(y); } catch (Floatexc b) { fl+=fl; } return fl; } }

Yet Another …Install handler… pushl $_6 except 8 Floatexc_C call __Jv_Init. Class addl $4, %esp …Enter try block… L 17: movl $0, -4(%ebp) pushl 8(%ebp) call _6 except 8 Floatexc_Mf. I addl $4, %esp movl %eax, %ecx … …A handler… L 22: flds -4(%ebp) fadds -4(%ebp) jmp L 18 … To the end

Why PCC May be a Reasonable Idea

Ten Good Things About PCC 1. Someone else does all the really hard work. 2. The host system changes very little. .

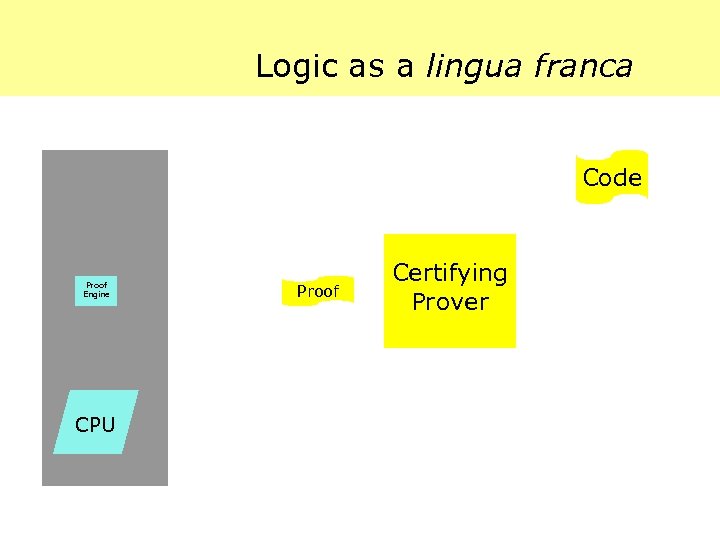

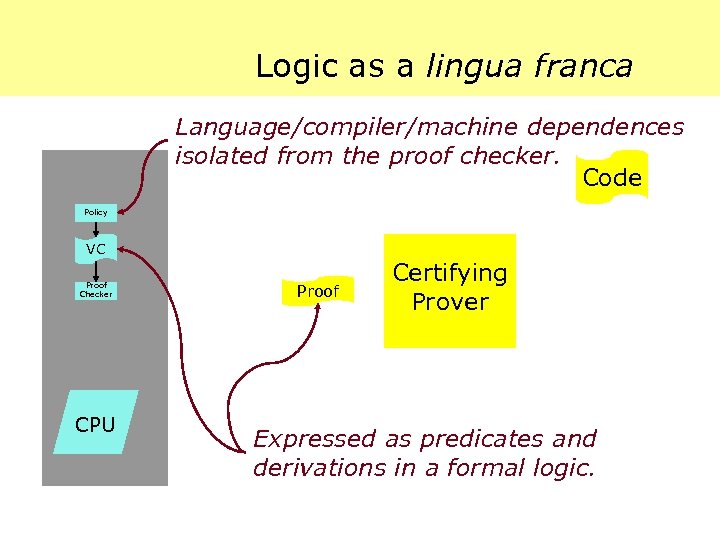

Logic as a lingua franca Code Proof Engine CPU Proof Certifying Prover

Logic as a lingua franca Language/compiler/machine dependences isolated from the proof checker. Code Policy VC Proof Checker CPU Proof Certifying Prover Expressed as predicates and derivations in a formal logic.

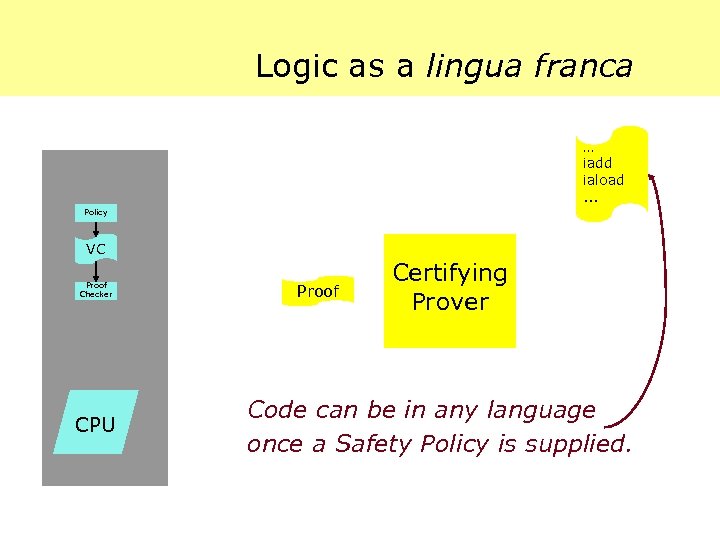

Logic as a lingua franca … iadd iaload. . . Policy VC Proof Checker CPU Proof Certifying Prover Code can be in any language once a Safety Policy is supplied.

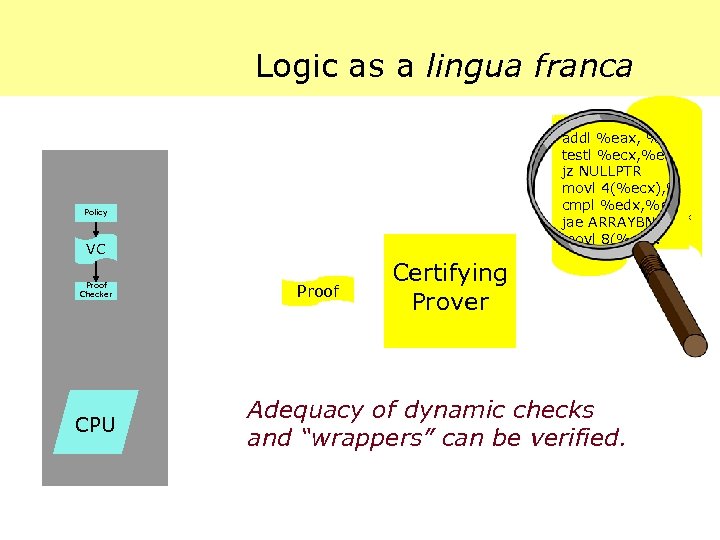

Logic as a lingua franca … addl %eax, %ebx testl %ecx, %ecx jz NULLPTR movl 4(%ecx), %edx movl 4(%ecx), % cmpl %edx, %ebx jae ARRAYBNDS cmpl %edx, %eb movl 8(%ecx. %ebx. 4). %edx jae ARRAYBND. . . movl 8(%ecx. Policy VC Proof Checker CPU Proof Certifying Prover Adequacy of dynamic checks and “wrappers” can be verified.

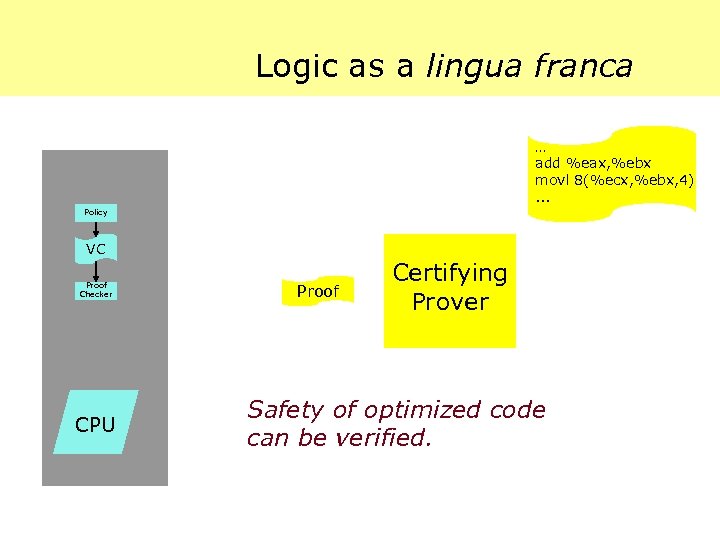

Logic as a lingua franca … add %eax, %ebx movl 8(%ecx, %ebx, 4). . . Policy VC Proof Checker CPU Proof Certifying Prover Safety of optimized code can be verified.

Ten Good Things About PCC 3. You choose the language. 4. Optimized (“unsafe”) code is OK. 5. Verifies that your optimizer and dynamic checks are OK. …

The Role of Programming Languages Civilized programming languages can provide “safety for free”. · Well-formed/well-typed safe. Idea: Arrange for the compiler to “explain” why the target code it generates preserves the safety properties of the source program.

![Certifying Compilers [Necula & Lee, PLDI’ 98] Intuition: · Compiler “knows” why each translation Certifying Compilers [Necula & Lee, PLDI’ 98] Intuition: · Compiler “knows” why each translation](https://present5.com/presentation/4f7906959ae10b1f9341c63b3fa23066/image-101.jpg)

Certifying Compilers [Necula & Lee, PLDI’ 98] Intuition: · Compiler “knows” why each translation step is semantics-preserving. · So, have it generate a proof that safety is preserved. · “Small theorems about big programs. ” Don’t try to verify the whole compiler, but only each output it generates.

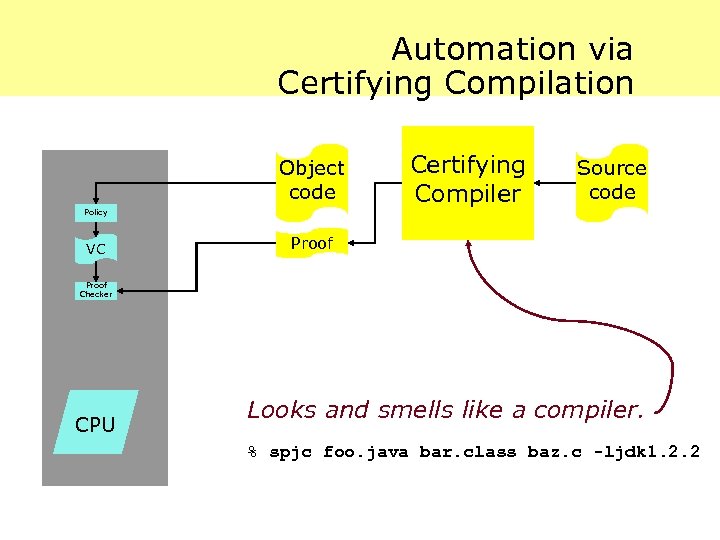

Automation via Certifying Compilation Object code Policy VC Certifying Compiler Source code Proof Checker CPU Looks and smells like a compiler. % spjc foo. java bar. class baz. c -ljdk 1. 2. 2

Ten Good Things About PCC 6. Can sometimes be easy-to-use. 7. You can still be a “hero theorem hacker” if you want. .

Ten Good Things About PCC 8. Proofs are a “semantic checksum”. 9. Possibility for richer safety policies. 10. Co-exists peacefully with crypto.

Acknowledgments George Necula. Robert Harper and Frank Pfenning. Mark Plesko, Fred Blau, and John Gregorski.

Microsoft’s Active. F Technology WHa. T DO you WANT TO prove TODAy?

4f7906959ae10b1f9341c63b3fa23066.ppt