8438e9facca75c8cec7567066f41480f.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 111

Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and Postconcussion Syndrome: The New Evidence Base for Diagnosis and Treatment Michael Mc. Crea, Ph. D, ABPP-CN Neuroscience Center, Waukesha Memorial Hospital Department of Neurology, Medical College of Wisconsin

Objective: MTBI from A to Z Review and gain a clearer understanding of: 1. 2. 3. 4. MTBI on the all-Severity TBI Landscape Basic and Clinical Science of MTBI The True Natural History of MTBI Implications for Rethinking Postconcussion Syndrome What does the scientific literature tell us?

Unpaid Political Announcement 1. MTBI, more than any other clinical entity, is a neuropsychological construct 2. The contribution by neuropsychologists to MTBI research is unmatched by any other discipline 3. Neuropsychologists are uniquely suited to evaluate and treat MTBI 4. Neuropsychologists should not limit their role in MTBI just to neuropsych testing

Concussion Research Consortium (CRC) Neuropsychology: Neurosurgery: Neurology: Sports Medicine: Epidemiology: William Barr, Ph. D, ABPP Thomas Hammeke, Ph. D, ABPP Michael Mc. Crea, Ph. D, ABPP Scott Millis, Ph. D, ABPP Christopher Randolph, Ph. D, ABPP Robert Cantu, MD James Kelly, MD Kevin Guskiewicz, Ph. D, ATC Steve Marshall, Ph. D

Part 1: The TBI Landscape 1. Epidemiology and impact of allseverity TBI 2. Zeroing in on MTBI: Epi and Impact 3. Challenges in Defining & Diagnosing MTBI 4. Advances in MTBI research methodologies 5. Top 10 Conclusions

Traumatic Brain Injury: The Big Picture • Major public health problem world wide • 1. 4 -3. 0 million cases/yr in US • Leading cause of death & disability: 50 -100 K TBI deaths/yr in U. S. • 40+% of all trauma fatalities in US each year • At risk: very young/very old, males, minorities, low SES, substance abusers • Cost: ~ $100 billion/yr in US • The Forgotten Entity

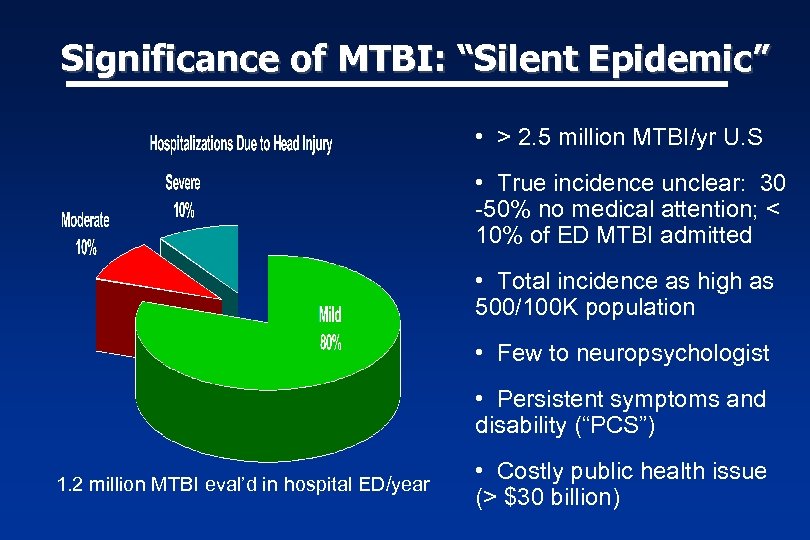

Significance of MTBI: “Silent Epidemic” • > 2. 5 million MTBI/yr U. S • True incidence unclear: 30 -50% no medical attention; < 10% of ED MTBI admitted • Total incidence as high as 500/100 K population • Few to neuropsychologist • Persistent symptoms and disability (“PCS”) 1. 2 million MTBI eval’d in hospital ED/year • Costly public health issue (> $30 billion)

Challenges in Defining & Diagnosing MTBI • Classifying TBI severity an imperfect science • Varied emphasis on acute injury characteristics • Limitations of traditional methods (GCS) • Limited reliability, validity, predictive power of newer classification methods • Numerous case and administrative definitions 2005

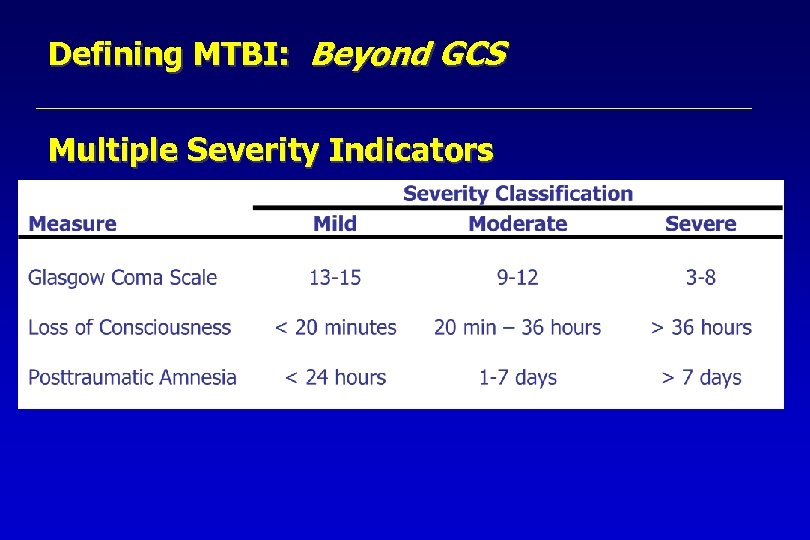

Defining MTBI: Beyond GCS Multiple Severity Indicators

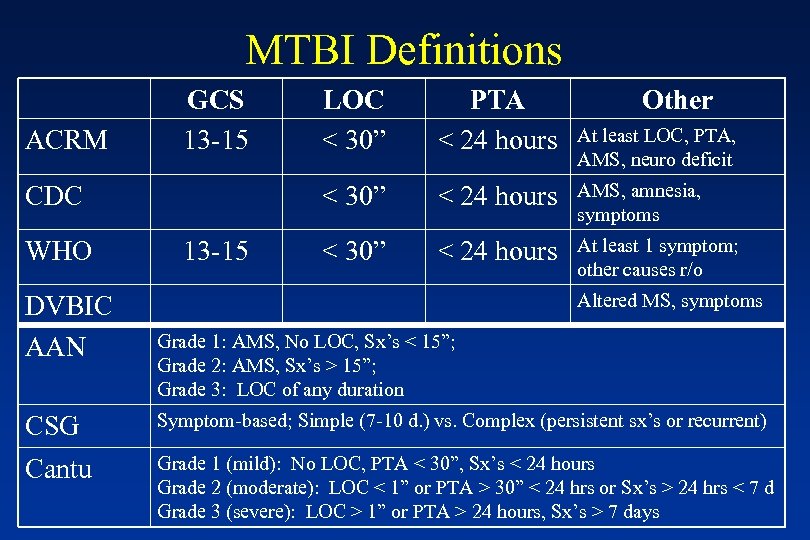

MTBI Definitions ACRM GCS 13 -15 WHO DVBIC AAN 13 -15 PTA < 24 hours < 30” CDC LOC < 30” Other < 24 hours AMS, amnesia, symptoms < 30” < 24 hours At least 1 symptom; other causes r/o At least LOC, PTA, AMS, neuro deficit Altered MS, symptoms Grade 1: AMS, No LOC, Sx’s < 15”; Grade 2: AMS, Sx’s > 15”; Grade 3: LOC of any duration CSG Symptom-based; Simple (7 -10 d. ) vs. Complex (persistent sx’s or recurrent) Cantu Grade 1 (mild): No LOC, PTA < 30”, Sx’s < 24 hours Grade 2 (moderate): LOC < 1” or PTA > 30” < 24 hrs or Sx’s > 24 hrs < 7 d Grade 3 (severe): LOC > 1” or PTA > 24 hours, Sx’s > 7 days

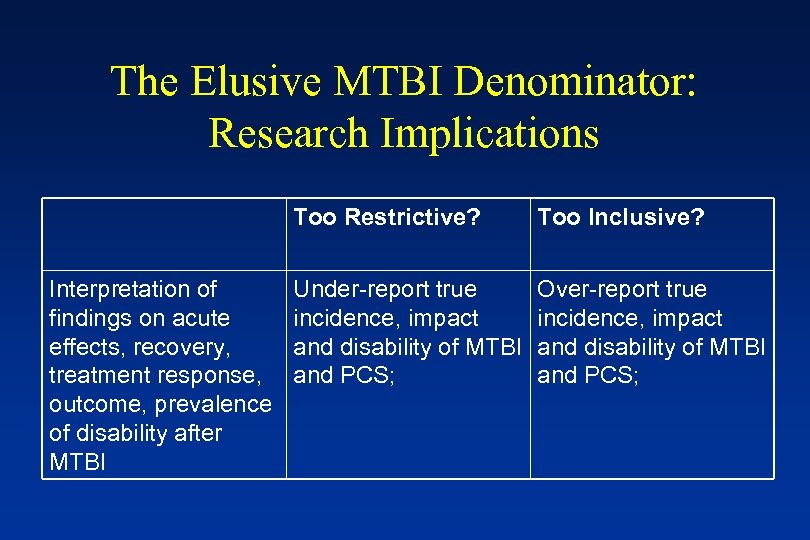

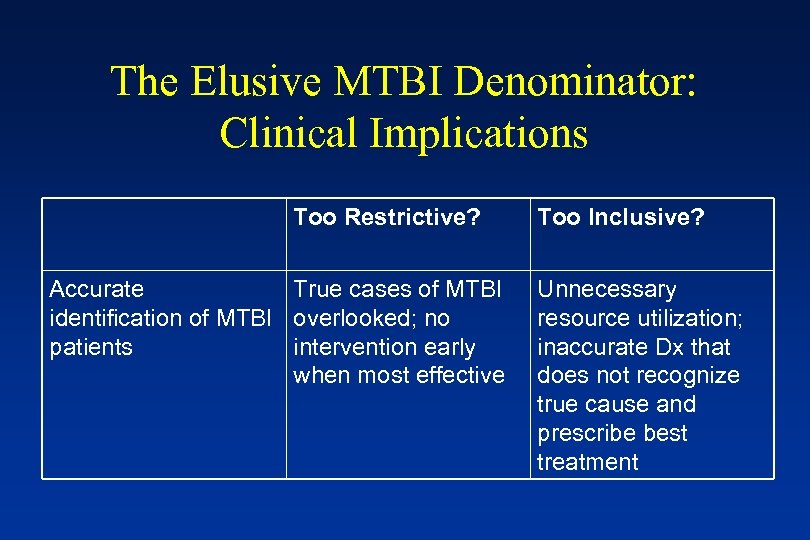

The Elusive MTBI Denominator: Research Implications Too Restrictive? Interpretation of findings on acute effects, recovery, treatment response, outcome, prevalence of disability after MTBI Too Inclusive? Under-report true incidence, impact and disability of MTBI and PCS; Over-report true incidence, impact and disability of MTBI and PCS;

The Elusive MTBI Denominator: Clinical Implications Too Restrictive? Accurate True cases of MTBI identification of MTBI overlooked; no patients intervention early when most effective Too Inclusive? Unnecessary resource utilization; inaccurate Dx that does not recognize true cause and prescribe best treatment

TBI Prognosis: Some Things Are Crystal Clear… Injury Severity is Strongest Predictor of Recovery after moderate and severe TBI

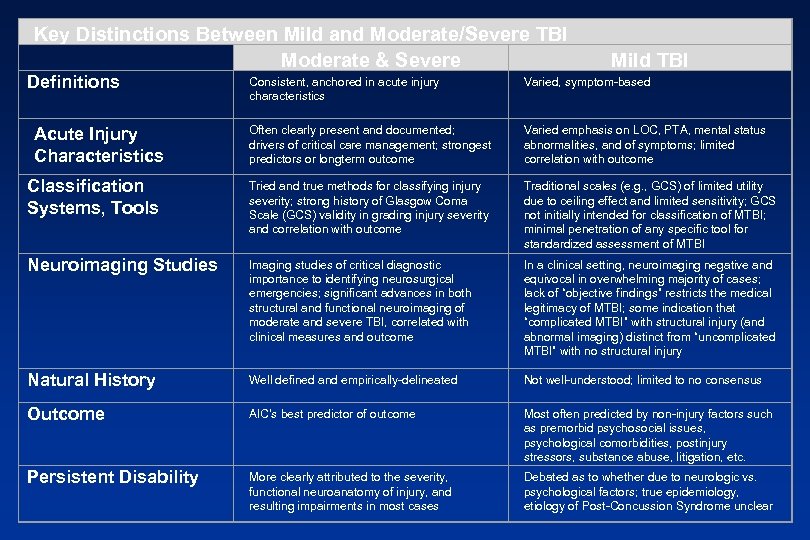

Key Distinctions Between Mild and Moderate/Severe TBI Moderate & Severe Definitions Mild TBI Consistent, anchored in acute injury characteristics Varied, symptom-based Often clearly present and documented; drivers of critical care management; strongest predictors or longterm outcome Varied emphasis on LOC, PTA, mental status abnormalities, and of symptoms; limited correlation with outcome Classification Systems, Tools Tried and true methods for classifying injury severity; strong history of Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) validity in grading injury severity and correlation with outcome Traditional scales (e. g. , GCS) of limited utility due to ceiling effect and limited sensitivity; GCS not initially intended for classification of MTBI; minimal penetration of any specific tool for standardized assessment of MTBI Neuroimaging Studies Imaging studies of critical diagnostic importance to identifying neurosurgical emergencies; significant advances in both structural and functional neuroimaging of moderate and severe TBI, correlated with clinical measures and outcome In a clinical setting, neuroimaging negative and equivocal in overwhelming majority of cases; lack of “objective findings” restricts the medical legitimacy of MTBI; some indication that “complicated MTBI” with structural injury (and abnormal imaging) distinct from “uncomplicated MTBI” with no structural injury Natural History Well defined and empirically-delineated Not well-understood; limited to no consensus Outcome AIC’s best predictor of outcome Most often predicted by non-injury factors such as premorbid psychosocial issues, psychological comorbidities, postinjury stressors, substance abuse, litigation, etc. Persistent Disability More clearly attributed to the severity, functional neuroanatomy of injury, and resulting impairments in most cases Debated as to whether due to neurologic vs. psychological factors; true epidemiology, etiology of Post-Concussion Syndrome unclear Acute Injury Characteristics

… And Some Things Are Not So Clear MTBI is a Different Animal All Together “All MTBI Are Not Created Equally” – Grant Iverson, 2005

Acute MTBI Research Limitations • • • Lack of witness account of injury Immediate accessibility to injured patients Neuropsychological testing impractical in ER Lack of objective measures under constraints Lack of premorbid baseline measures Multitude of non-injury factors: alcohol/drugs, other injuries, litigation, others

MTBI Unknowns & Clinical Challenges • Diagnosis: Minimum threshold for injury (i. e. , was there indeed an MTBI? ) Defining characteristics? Other causes for symptoms? • Recovery: How long should it take to recovery after MTBI? What is the expected natural course of this injury? • Prognosis: What are the acute and subacute predictors of positive and negative outcomes after MTBI? • Complications: To what extent are neurologic versus psychological factors contributing to symptoms and deficits? • Treatment: Given all this, what approach to treatment gives my patient the best chance for recovery? • Outcome: What are the best methods to assess recovery and functional outcome after MTBI?

Streaker Suffers Concussion If you're planning to streak at an NHL game, at least wear a pair of skates. In the third period of Thursday's Bruins-Flames game in Calgary, a male streaker (wearing only red socks and a smile) scaled the low glass near the scorers table and jumped onto the playing surface. The naked stranger quickly lost his balance, falling backwards and hitting his head on the ice, knocking himself unconscious. After a sixminute delay, the streaker was covered up and carted off the ice on a stretcher, waving to cheering fans.

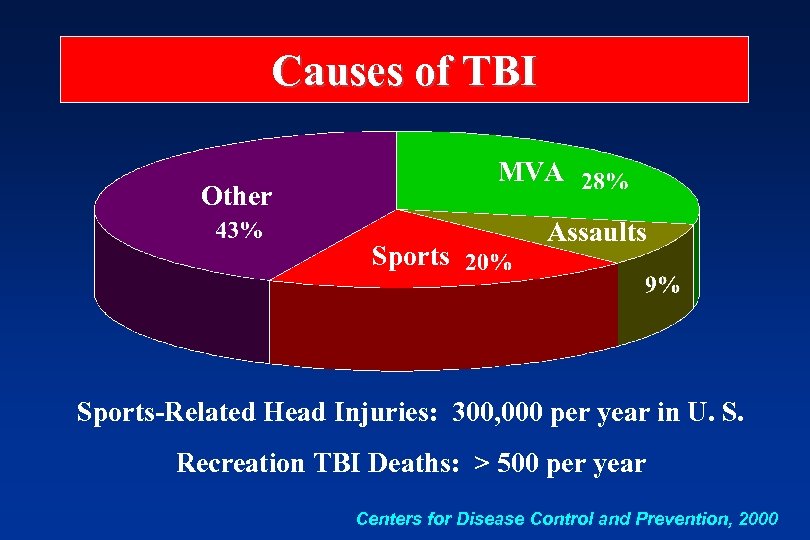

Causes of TBI MVA Other Sports Assaults Sports-Related Head Injuries: 300, 000 per year in U. S. Recreation TBI Deaths: > 500 per year Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2000

TBI Landscape: Main Conclusions 1. TBI a major public health problem worldwide 2. > 80% classified as MTBI (500/100 K population) 3. Young/old, male, minorities of low SES at risk 4. Nothing “mild” about the total impact of MTBI 5. What works for moderate/severe may not for MTBI 6. Traditional MTBI research hampered by many issues 7. New innovative approaches to prospective researchers 8. New groundbreaking findings to date 9. Poised to answer: What is natural history of MTBI? 10. MTBI science extends our understanding of PCS

Part 2: Basic & Clinical Science of MTBI 1. Biomechanics 2. Neurophysiology 3. Neuroimaging

Biomechanics of MTBI: Establishing a minimal biomechanical threshold How much is enough to cause brain injury?

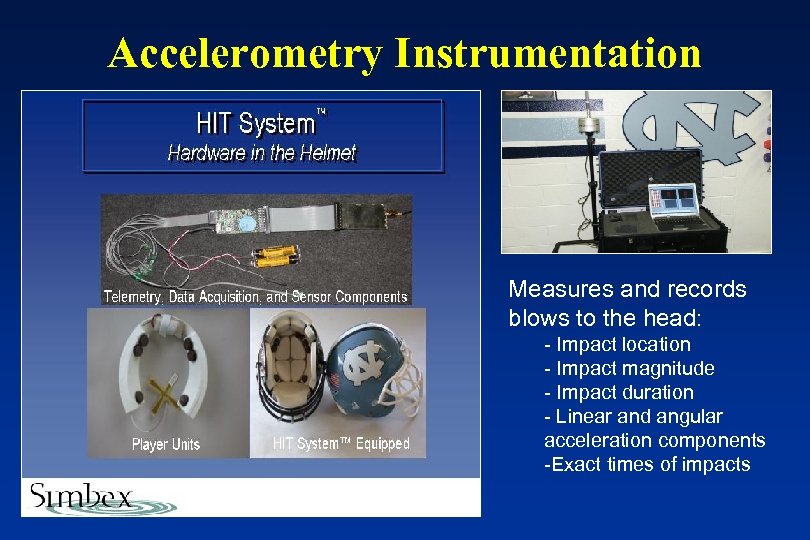

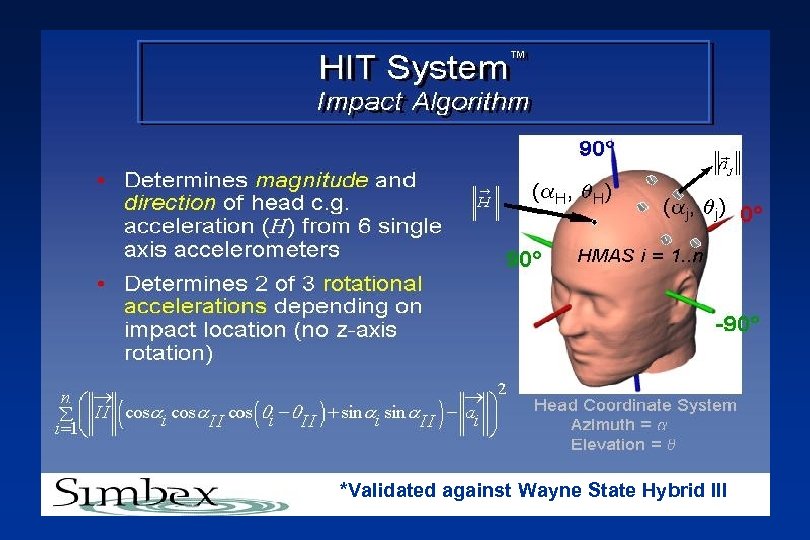

Accelerometry Instrumentation Measures and records blows to the head: - Impact location - Impact magnitude - Impact duration - Linear and angular acceleration components -Exact times of impacts

*Validated against Wayne State Hybrid III

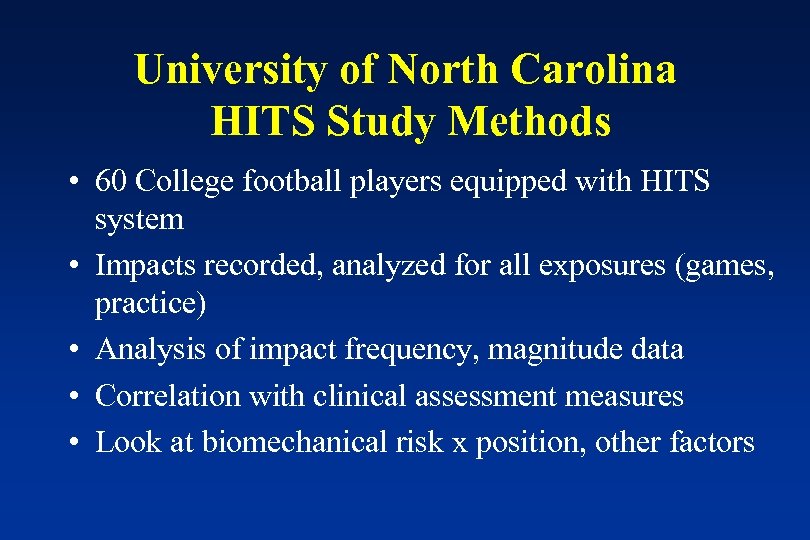

University of North Carolina HITS Study Methods • 60 College football players equipped with HITS system • Impacts recorded, analyzed for all exposures (games, practice) • Analysis of impact frequency, magnitude data • Correlation with clinical assessment measures • Look at biomechanical risk x position, other factors

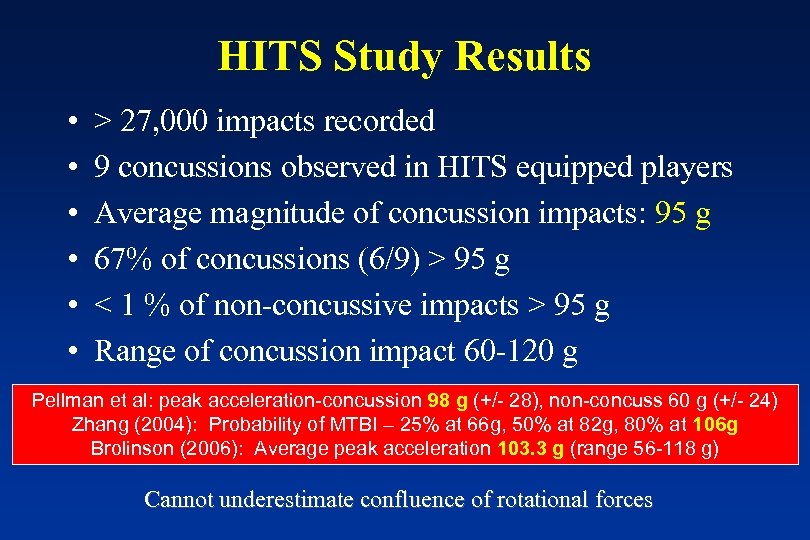

HITS Study Results • • • > 27, 000 impacts recorded 9 concussions observed in HITS equipped players Average magnitude of concussion impacts: 95 g 67% of concussions (6/9) > 95 g < 1 % of non-concussive impacts > 95 g Range of concussion impact 60 -120 g Pellman et al: peak acceleration-concussion 98 g (+/- 28), non-concuss 60 g (+/- 24) Zhang (2004): Probability of MTBI – 25% at 66 g, 50% at 82 g, 80% at 106 g Brolinson (2006): Average peak acceleration 103. 3 g (range 56 -118 g) Cannot underestimate confluence of rotational forces

Neurophysiology of MTBI • Diffuse Axonal Injury (DAI) prominent in moderate and severe TBI, not in MTBI • The pathophysiology of MTBI renders neurons dysfunctional, but not destroyed

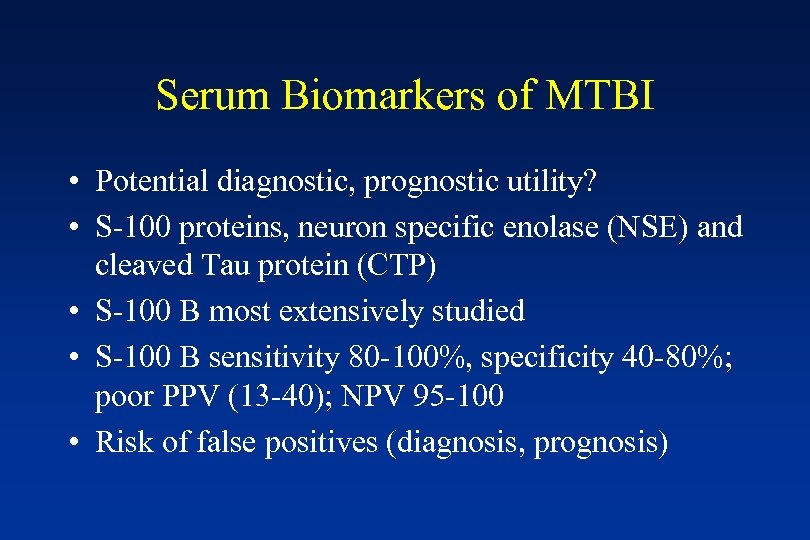

Serum Biomarkers of MTBI • Potential diagnostic, prognostic utility? • S-100 proteins, neuron specific enolase (NSE) and cleaved Tau protein (CTP) • S-100 B most extensively studied • S-100 B sensitivity 80 -100%, specificity 40 -80%; poor PPV (13 -40); NPV 95 -100 • Risk of false positives (diagnosis, prognosis)

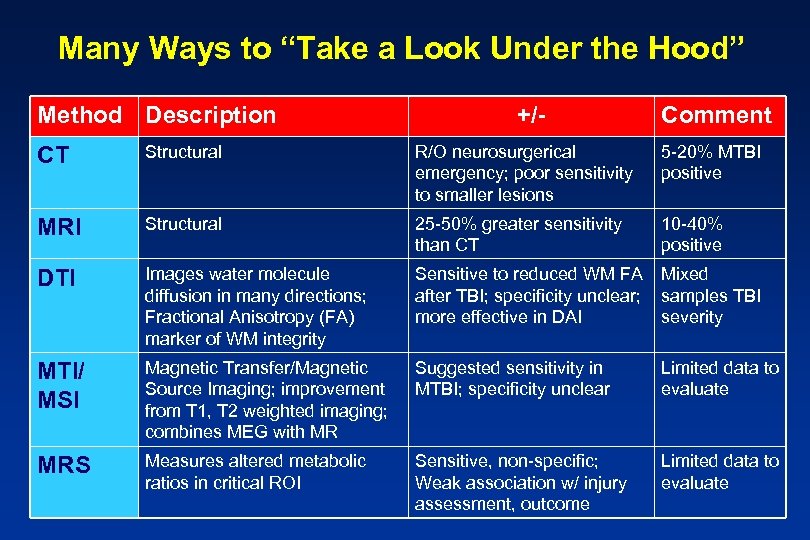

Many Ways to “Take a Look Under the Hood” Method Description +/- Comment CT Structural R/O neurosurgerical emergency; poor sensitivity to smaller lesions 5 -20% MTBI positive MRI Structural 25 -50% greater sensitivity than CT 10 -40% positive DTI Images water molecule diffusion in many directions; Fractional Anisotropy (FA) marker of WM integrity Sensitive to reduced WM FA Mixed after TBI; specificity unclear; samples TBI more effective in DAI severity MTI/ MSI Magnetic Transfer/Magnetic Source Imaging; improvement from T 1, T 2 weighted imaging; combines MEG with MR Suggested sensitivity in MTBI; specificity unclear Limited data to evaluate MRS Measures altered metabolic ratios in critical ROI Sensitive, non-specific; Weak association w/ injury assessment, outcome Limited data to evaluate

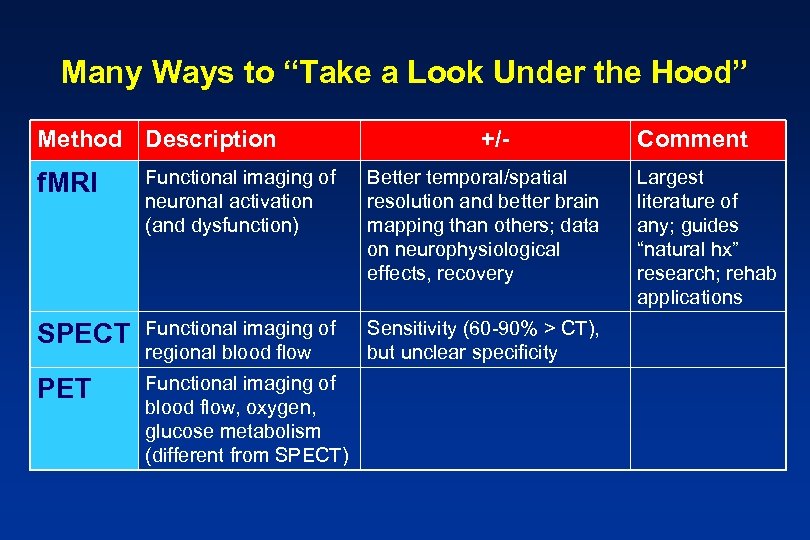

Many Ways to “Take a Look Under the Hood” Method Description +/- f. MRI Functional imaging of neuronal activation (and dysfunction) Better temporal/spatial resolution and better brain mapping than others; data on neurophysiological effects, recovery SPECT Functional imaging of regional blood flow Sensitivity (60 -90% > CT), but unclear specificity PET Functional imaging of blood flow, oxygen, glucose metabolism (different from SPECT) Comment Largest literature of any; guides “natural hx” research; rehab applications

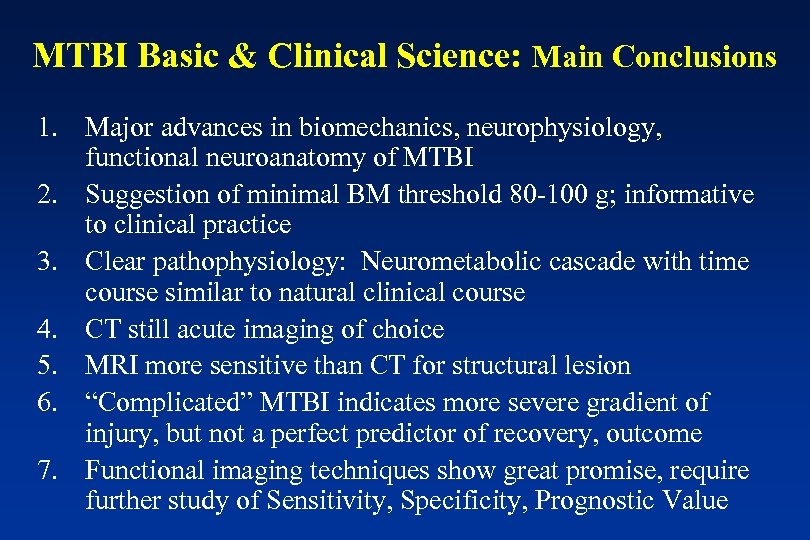

MTBI Basic & Clinical Science: Main Conclusions 1. Major advances in biomechanics, neurophysiology, functional neuroanatomy of MTBI 2. Suggestion of minimal BM threshold 80 -100 g; informative to clinical practice 3. Clear pathophysiology: Neurometabolic cascade with time course similar to natural clinical course 4. CT still acute imaging of choice 5. MRI more sensitive than CT for structural lesion 6. “Complicated” MTBI indicates more severe gradient of injury, but not a perfect predictor of recovery, outcome 7. Functional imaging techniques show great promise, require further study of Sensitivity, Specificity, Prognostic Value

Part 3: What is the true natural history of MTBI?

Part 3: Natural History of MTBI 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Acute symptoms and symptom recovery Acute cognitive effects and early recovery Neuropsychological recovery Influence of acute injury characteristics on recovery Measuring neurophysiological recovery Functional outcome after MTBI Exceptions to the rule: Longterm effects of MTBI? Top 10 Conclusions

Can we measure the immediate effects of injury? What does earliest recovery look like?

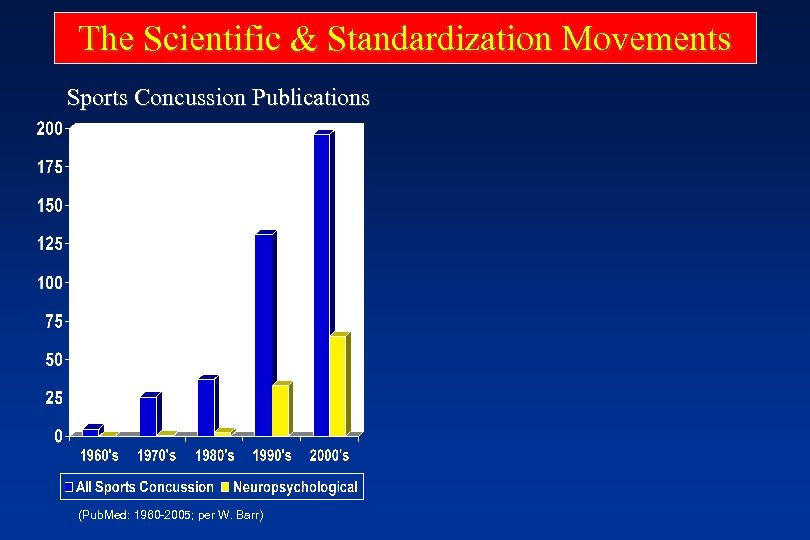

The Scientific & Standardization Movements Sports Concussion Publications (Pub. Med: 1960 -2005; per W. Barr)

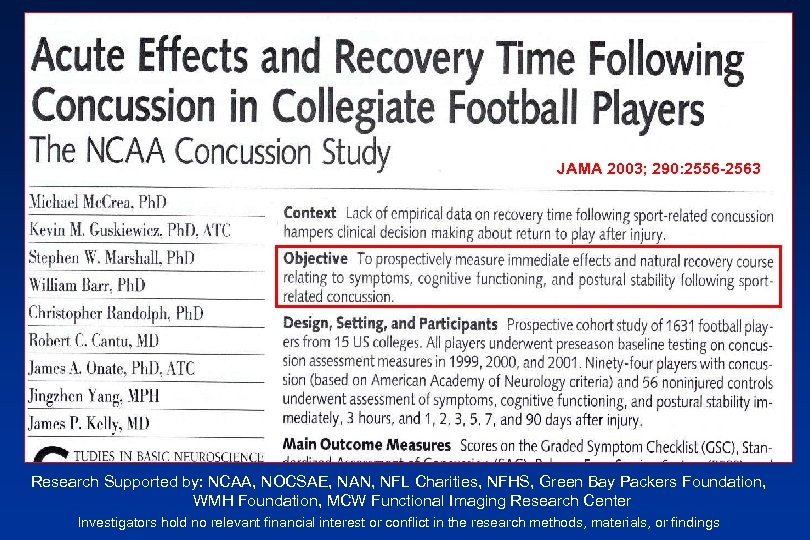

JAMA 2003; 290: 2556 -2563 Research Supported by: NCAA, NOCSAE, NAN, NFL Charities, NFHS, Green Bay Packers Foundation, WMH Foundation, MCW Functional Imaging Research Center Investigators hold no relevant financial interest or conflict in the research methods, materials, or findings

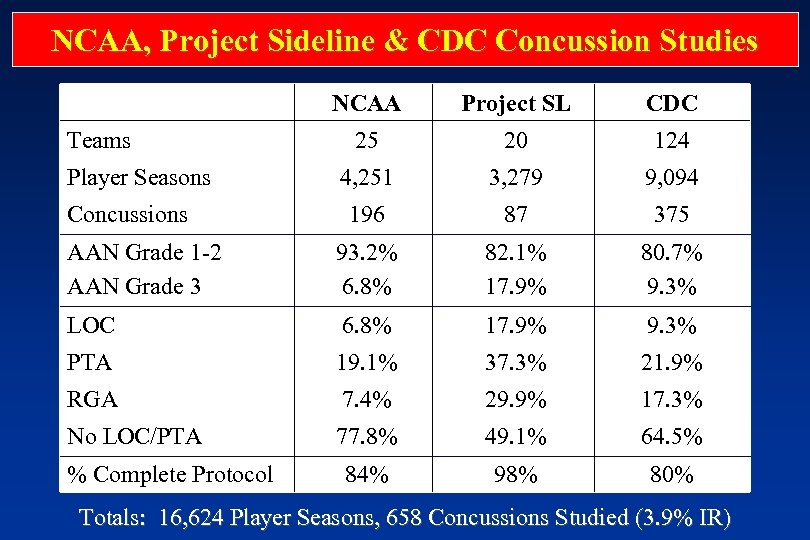

NCAA, Project Sideline & CDC Concussion Studies NCAA Project SL CDC 25 20 124 4, 251 3, 279 9, 094 196 87 375 AAN Grade 1 -2 AAN Grade 3 93. 2% 6. 8% 82. 1% 17. 9% 80. 7% 9. 3% LOC 6. 8% 17. 9% 9. 3% PTA 19. 1% 37. 3% 21. 9% RGA 7. 4% 29. 9% 17. 3% No LOC/PTA 77. 8% 49. 1% 64. 5% 84% 98% 80% Teams Player Seasons Concussions % Complete Protocol Totals: 16, 624 Player Seasons, 658 Concussions Studied (3. 9% IR)

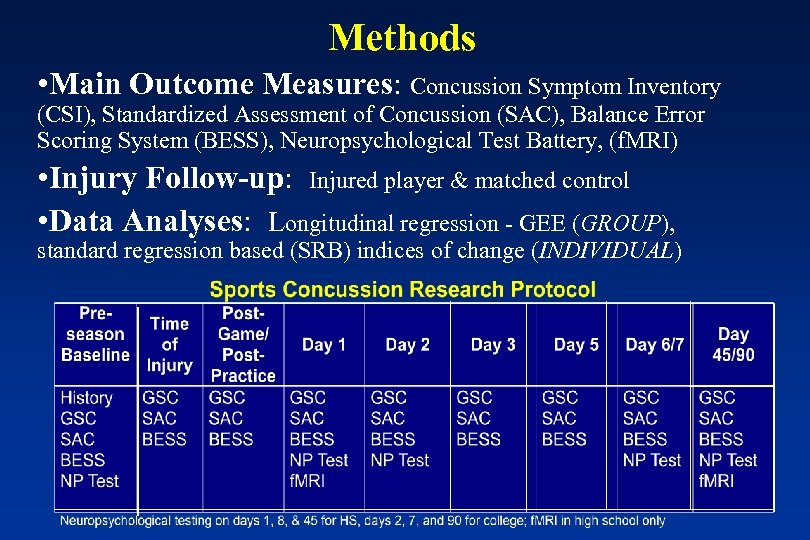

Methods • Main Outcome Measures: Concussion Symptom Inventory (CSI), Standardized Assessment of Concussion (SAC), Balance Error Scoring System (BESS), Neuropsychological Test Battery, (f. MRI) • Injury Follow-up: Injured player & matched control • Data Analyses: Longitudinal regression - GEE (GROUP), standard regression based (SRB) indices of change (INDIVIDUAL)

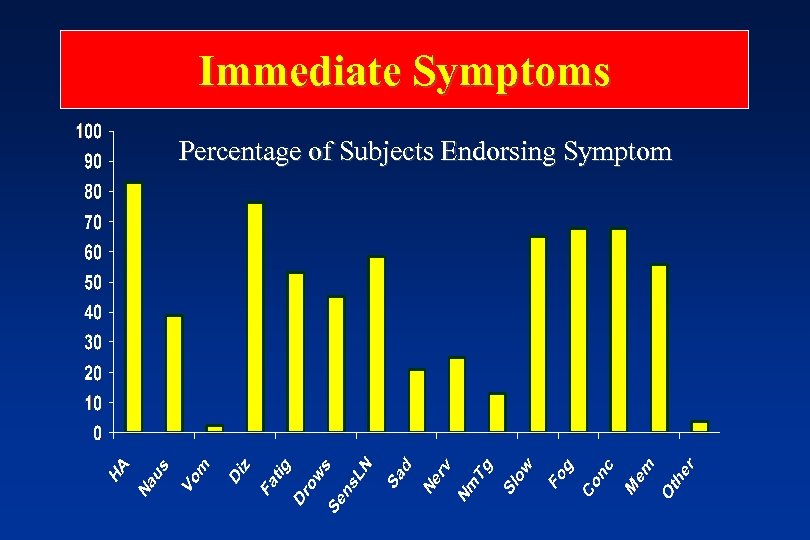

Immediate Symptoms Percentage of Subjects Endorsing Symptom

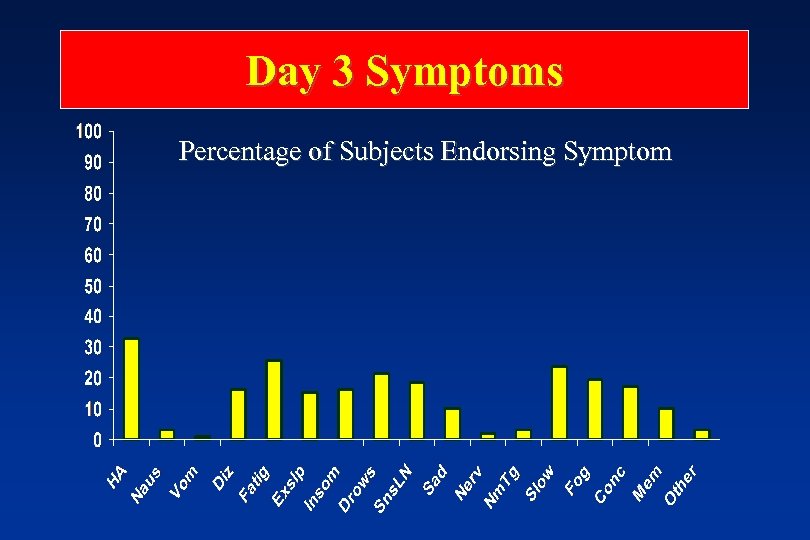

Day 3 Symptoms Percentage of Subjects Endorsing Symptom

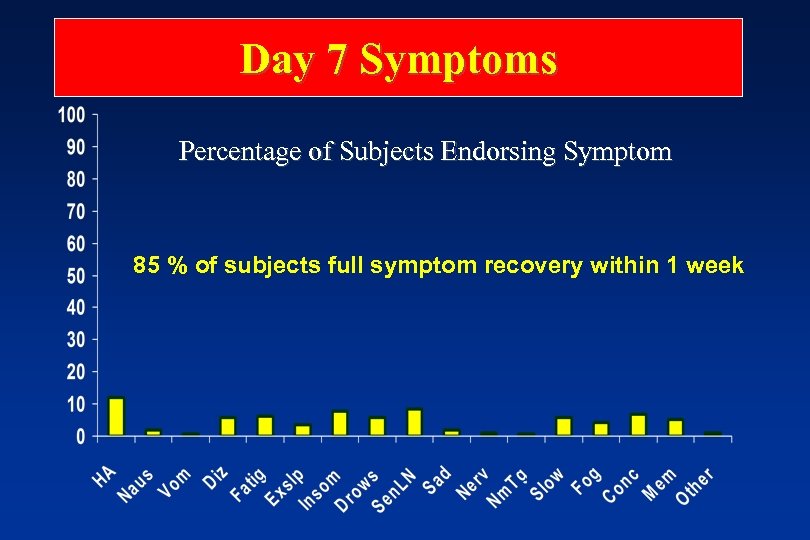

Day 7 Symptoms Percentage of Subjects Endorsing Symptom 85 % of subjects full symptom recovery within 1 week

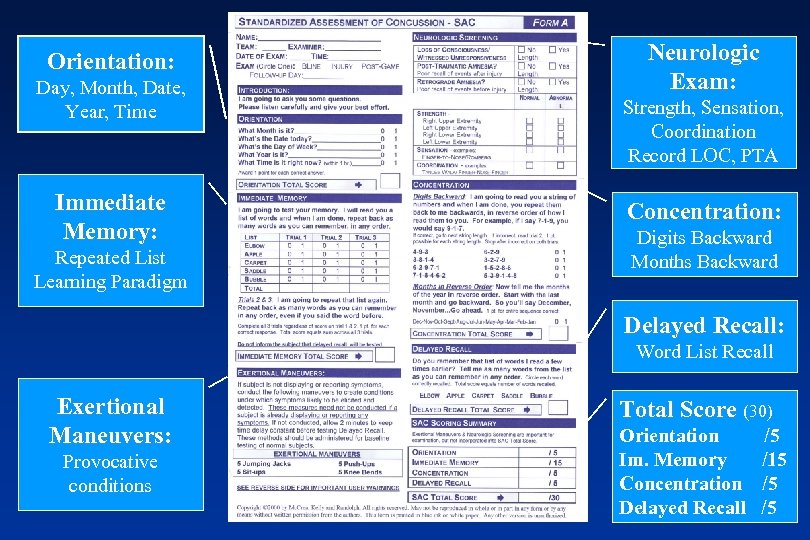

Orientation: Day, Month, Date, Year, Time Immediate Memory: Repeated List Learning Paradigm Neurologic Exam: Strength, Sensation, Coordination Record LOC, PTA Concentration: Digits Backward Months Backward Delayed Recall: Word List Recall Exertional Maneuvers: Provocative conditions Total Score (30) Orientation Im. Memory Concentration Delayed Recall /5 /15 /5 /5

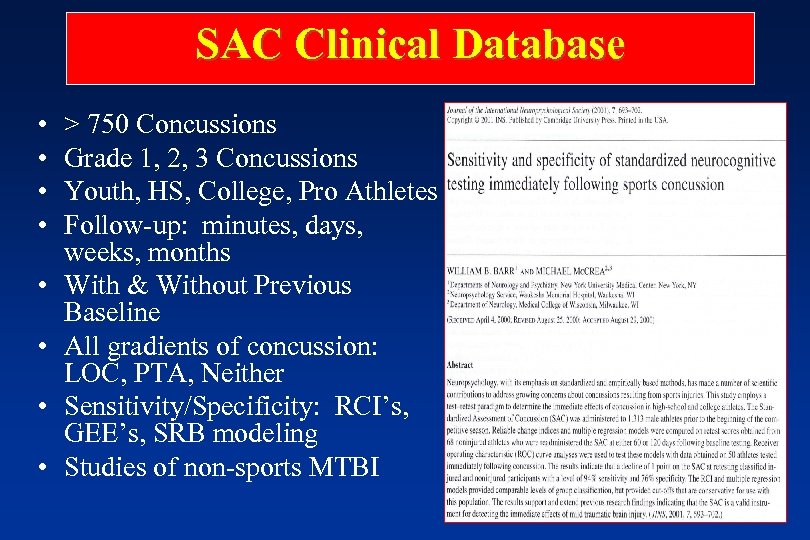

SAC Clinical Database • • > 750 Concussions Grade 1, 2, 3 Concussions Youth, HS, College, Pro Athletes Follow-up: minutes, days, weeks, months With & Without Previous Baseline All gradients of concussion: LOC, PTA, Neither Sensitivity/Specificity: RCI’s, GEE’s, SRB modeling Studies of non-sports MTBI

Complexity of Neuropsychological Testing

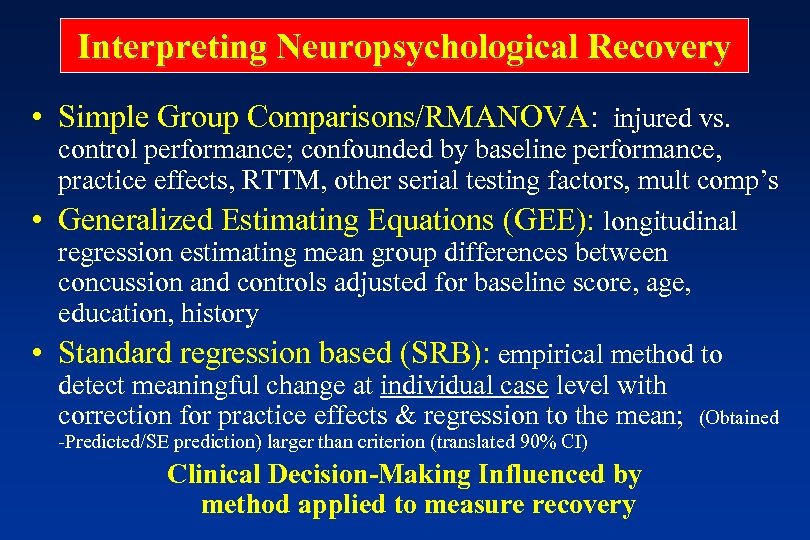

Interpreting Neuropsychological Recovery • Simple Group Comparisons/RMANOVA: injured vs. control performance; confounded by baseline performance, practice effects, RTTM, other serial testing factors, mult comp’s • Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE): longitudinal regression estimating mean group differences between concussion and controls adjusted for baseline score, age, education, history • Standard regression based (SRB): empirical method to detect meaningful change at individual case level with correction for practice effects & regression to the mean; (Obtained -Predicted/SE prediction) larger than criterion (translated 90% CI) Clinical Decision-Making Influenced by method applied to measure recovery

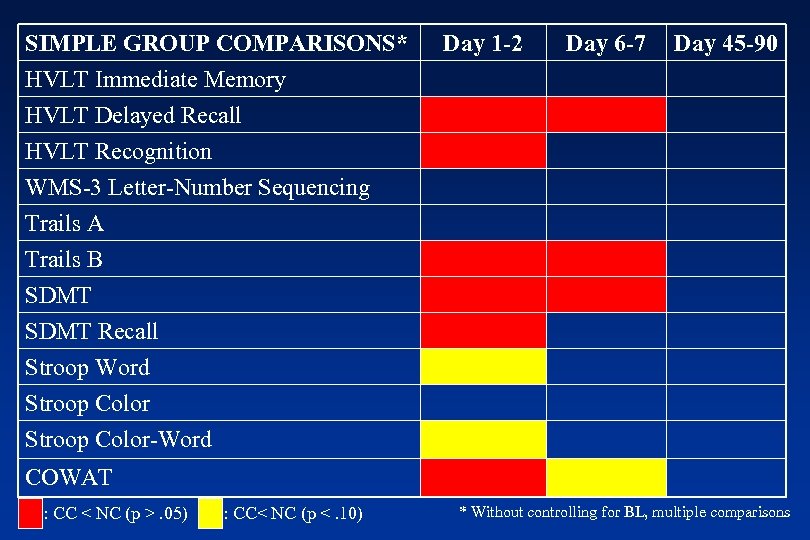

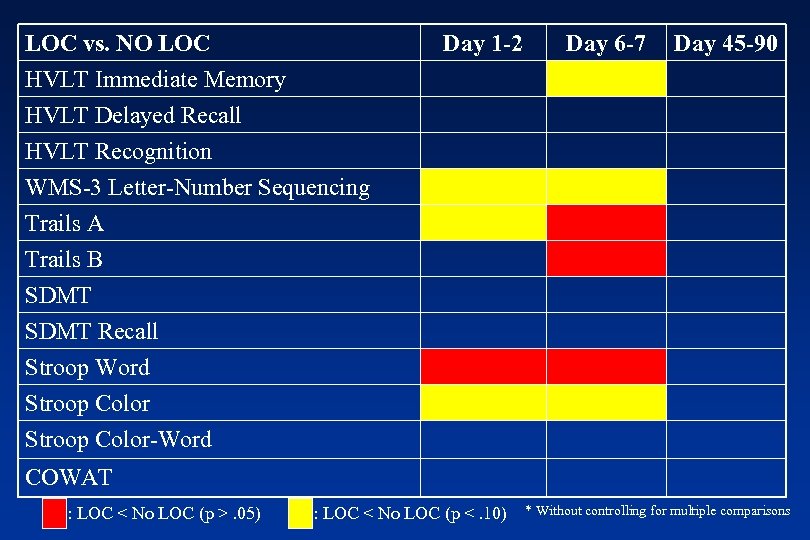

SIMPLE GROUP COMPARISONS* HVLT Immediate Memory HVLT Delayed Recall HVLT Recognition Day 1 -2 Day 6 -7 Day 45 -90 WMS-3 Letter-Number Sequencing Trails A Trails B SDMT Recall Stroop Word Stroop Color-Word COWAT : CC < NC (p >. 05) : CC< NC (p <. 10) * Without controlling for BL, multiple comparisons

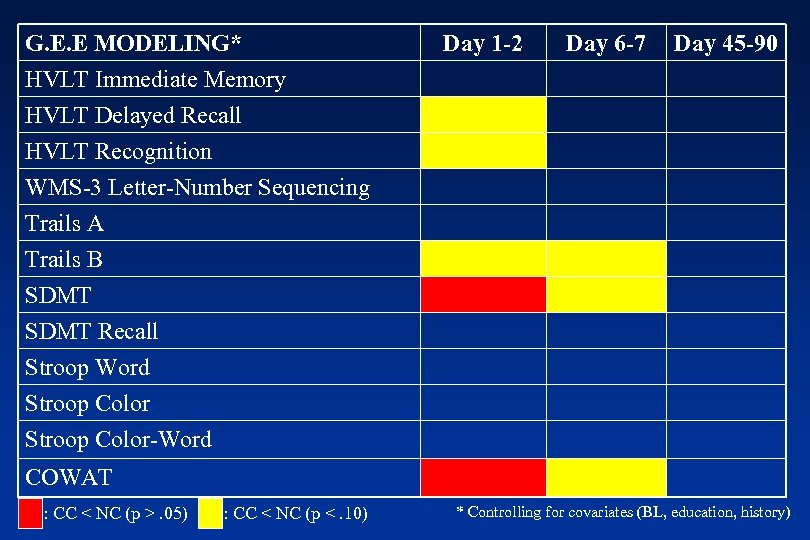

G. E. E MODELING* HVLT Immediate Memory HVLT Delayed Recall HVLT Recognition Day 1 -2 Day 6 -7 Day 45 -90 WMS-3 Letter-Number Sequencing Trails A Trails B SDMT Recall Stroop Word Stroop Color-Word COWAT : CC < NC (p >. 05) : CC < NC (p <. 10) * Controlling for covariates (BL, education, history)

• Meta-analysis: 21 studies, 790 concussions, 2014 controls • Acute effects (w/n 24 hrs) greatest for delayed memory (d=1. 00), memory acquisition (d=1. 03), and global cognitive functioning (d=1. 42) • No residual neuropsych impairment > 7 days postinjury • Findings moderated by cognitive domain, comparison group (control vs. self-control) Overall ES (d=0. 49) comparable to non-sports (d=0. 54)

Neuropsychological Recovery after MTBI: The Meta-Analytic Age • A Quantitative Review of the Effects of Traumatic Brain Injury on Cognitive Functioning Schretlin, David & Shapiro, Ann (International Review of Psychiatry, 2003, 15, 341 -349) • Factors Moderating Neuropsychological Outcomes Following MTBI: A Meta-Analysis Belanger, Curtiss, Demery, Lebowitz, & Vanderploeg (JINS, 2005, 11, 215 -227) • Outcomes from Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Iverson, Grant (Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 2005, 18, 301 -317)

Summary – 39 studies, 48 MTBI (n=1716) vs. control (n=1164) comparisons; –“Moderate” ↓ in overall cognitive functioning <7 days post-injury (d=. 41) –Learning/memory, RT, and attention show greatest acute effects –Effects diminish by 7 -29 days (. 29), disappear by 30 -89 days (. 08) post –“Recovery” of overall functioning follows a logarithmic course

• Meta-analysis: 39 studies, 1463 MTBI cases, 1191 controls • Overall effect of MTBI on neuropsychological functioning moderate (d=. 54) • Acute: greatest affect on memory (d=1. 03), fluency (d =. 89) • Unselected or prospective samples: No residual NP effects by 3 mos. (d=. 04) • Clinic samples (. 74) & litigants (. 78) at 3 mos. • Litigation associated with stable or worsening cognition

• Extensive literature review; excellent MTBI shelf reference • Little doubt about abnormal neurophysiology as cause of sx’s, dysfunction acutely • Maximal sx’s first 72 hours, rapid improvement over 1 st week • Delayed recovery often largely related to other comorbidities (e. g. , depression, pain, PTSD, etc. ) • All MTBI not created equally “Clearly, the estimate of 10 -20% of patients with MTBIs not recoverying by 6 -12 months is much too high”

Putting Tests to the Test How sensitive is standardized testing in detecting real abnormalities in the asymptomatic player who says “I’m fine” and would otherwise be returned to play?

Classifying Individual Impairment • SRB Model: Linear regression on control BL scores to generate formula to predict scores at T 2. . . • Regression coefficient, intercept of regression line used with BL score to predict score for each subject at T 2 and subsequent time points • Meaningful change: (Obtained. Predicted/SE prediction) > criterion JINS , 2005, 11, 1 -12 (translated 90% CI) • Empirical method to detect “true” impairment/recovery; correction for practice effects, RTTM

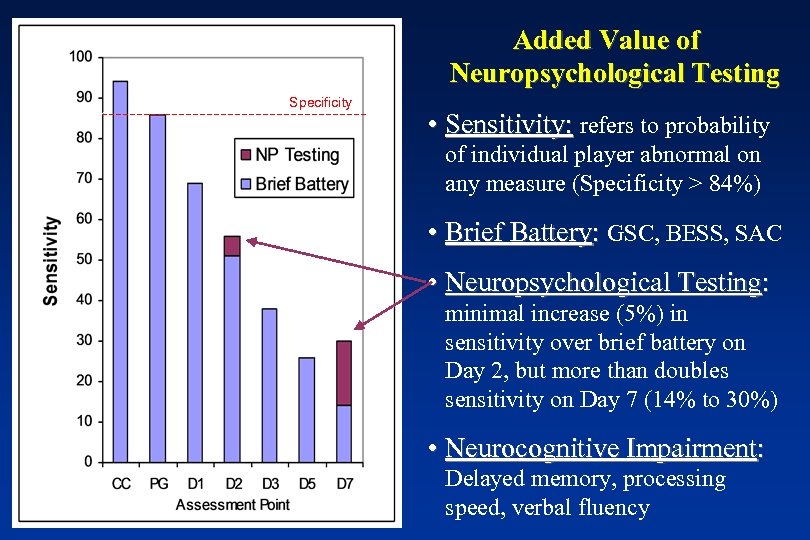

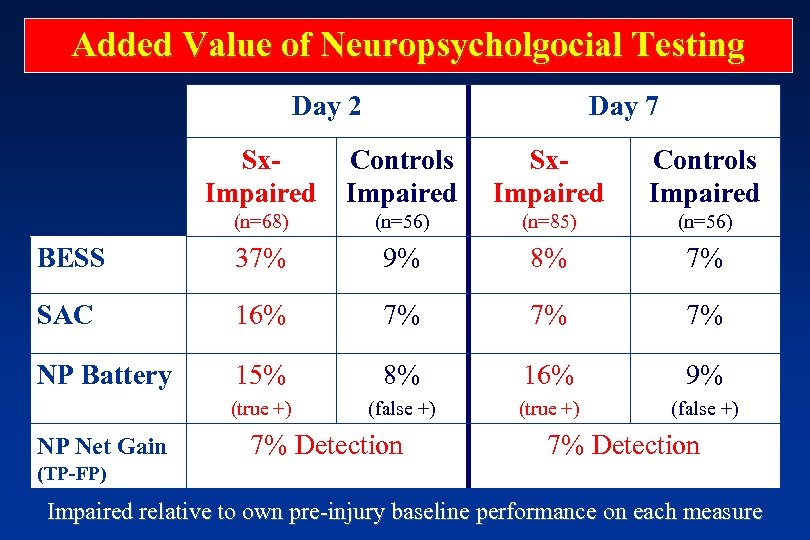

Added Value of Neuropsychological Testing Specificity • Sensitivity: refers to probability of individual player abnormal on any measure (Specificity > 84%) • Brief Battery: GSC, BESS, SAC • Neuropsychological Testing: minimal increase (5%) in sensitivity over brief battery on Day 2, but more than doubles sensitivity on Day 7 (14% to 30%) • Neurocognitive Impairment: Delayed memory, processing speed, verbal fluency

Added Value of Neuropsycholgocial Testing Day 2 Day 7 Sx. Controls Impaired Sx. Impaired Controls Impaired (n=68) (n=56) (n=85) (n=56) BESS 37% 9% 8% 7% SAC 16% 7% 7% 7% NP Battery 15% 8% 16% 9% (true +) (false +) NP Net Gain 7% Detection (TP-FP) Impaired relative to own pre-injury baseline performance on each measure

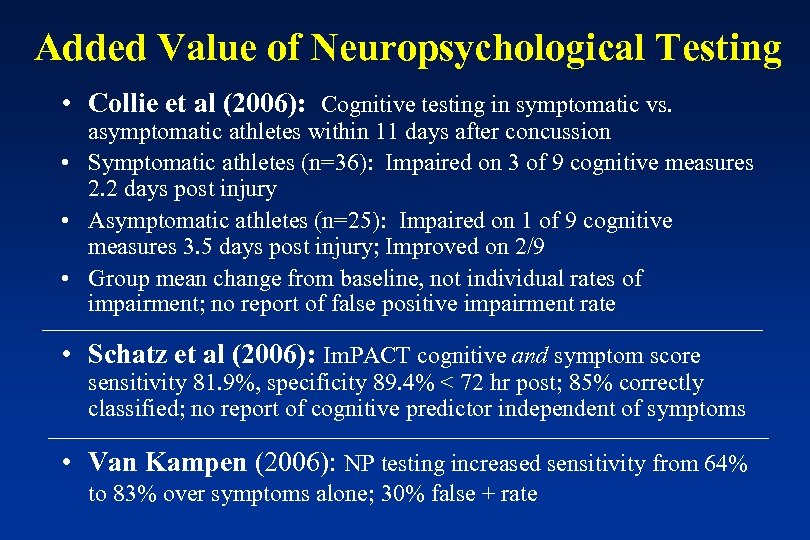

Added Value of Neuropsychological Testing • Collie et al (2006): Cognitive testing in symptomatic vs. asymptomatic athletes within 11 days after concussion • Symptomatic athletes (n=36): Impaired on 3 of 9 cognitive measures 2. 2 days post injury • Asymptomatic athletes (n=25): Impaired on 1 of 9 cognitive measures 3. 5 days post injury; Improved on 2/9 • Group mean change from baseline, not individual rates of impairment; no report of false positive impairment rate • Schatz et al (2006): Im. PACT cognitive and symptom score sensitivity 81. 9%, specificity 89. 4% < 72 hr post; 85% correctly classified; no report of cognitive predictor independent of symptoms • Van Kampen (2006): NP testing increased sensitivity from 64% to 83% over symptoms alone; 30% false + rate

Evolution of Neuropsychological Testing in Sports Concussion • 1997: “Development of a standardized neuropsychological test battery is recommended to detect impairment associated with concussion” (AAN Practice Parameter) • 1999: “The usefulness of neuropsychological assessment in clinical decision making should not be short-changed” (AOSSM Concussion Workshop Group) • 2001: “Neuropsychological Testing is one of the cornerstones of concussion evaluation” (CISG, Vienna Agreement Statement)

Evolution of Neuropsychological Testing • 2004: “Neuropsychological testing should not be done while the athlete is symptomatic because it adds nothing to return-to-play decisions and may contaminate the testing process by allowing practice effects to confound results” • “recommended that neuropsychological testing remain one of the cornerstones of concussion evaluation in complex concussion…is not currently regarded as important in the evaluation of simple concussion… should not be the sole basis for management decisions, either for continued time out or return to play decisions” (CISG, Prague Agreement Statement)

Influence of Acute Injury Characteristics on Recovery

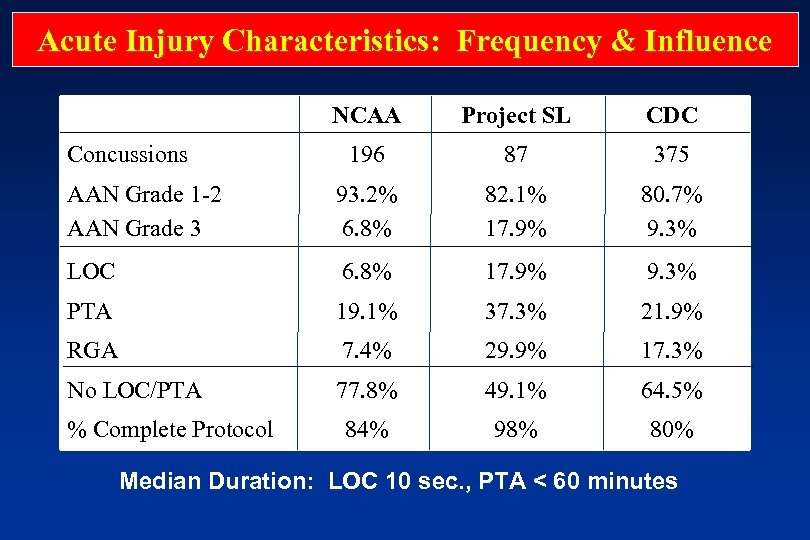

Acute Injury Characteristics: Frequency & Influence NCAA Project SL CDC 196 87 375 AAN Grade 1 -2 AAN Grade 3 93. 2% 6. 8% 82. 1% 17. 9% 80. 7% 9. 3% LOC 6. 8% 17. 9% 9. 3% PTA 19. 1% 37. 3% 21. 9% RGA 7. 4% 29. 9% 17. 3% No LOC/PTA 77. 8% 49. 1% 64. 5% 84% 98% 80% Concussions % Complete Protocol Median Duration: LOC 10 sec. , PTA < 60 minutes

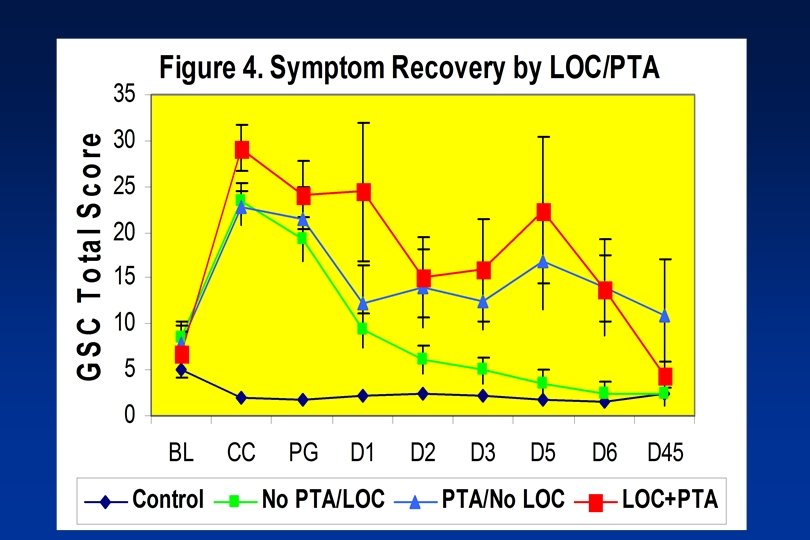

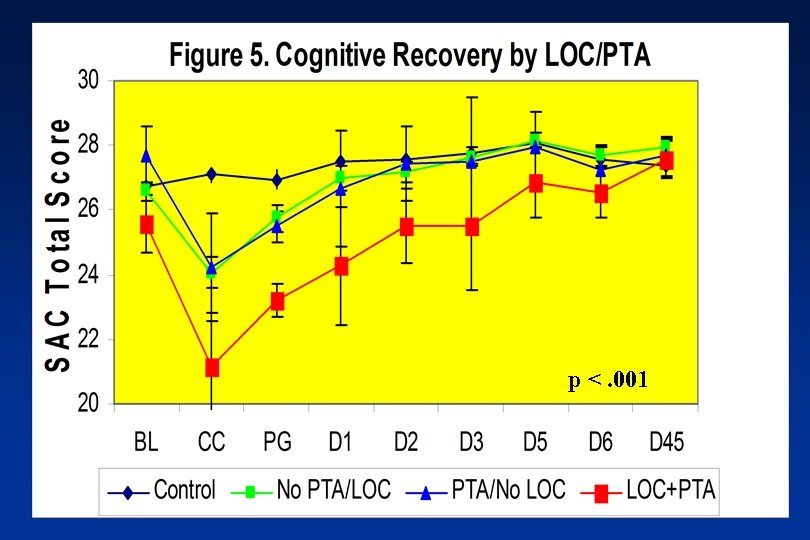

p <. 001

LOC vs. NO LOC HVLT Immediate Memory HVLT Delayed Recall HVLT Recognition Day 1 -2 Day 6 -7 Day 45 -90 WMS-3 Letter-Number Sequencing Trails A Trails B SDMT Recall Stroop Word Stroop Color-Word COWAT : LOC < No LOC (p >. 05) : LOC < No LOC (p <. 10) * Without controlling for multiple comparisons

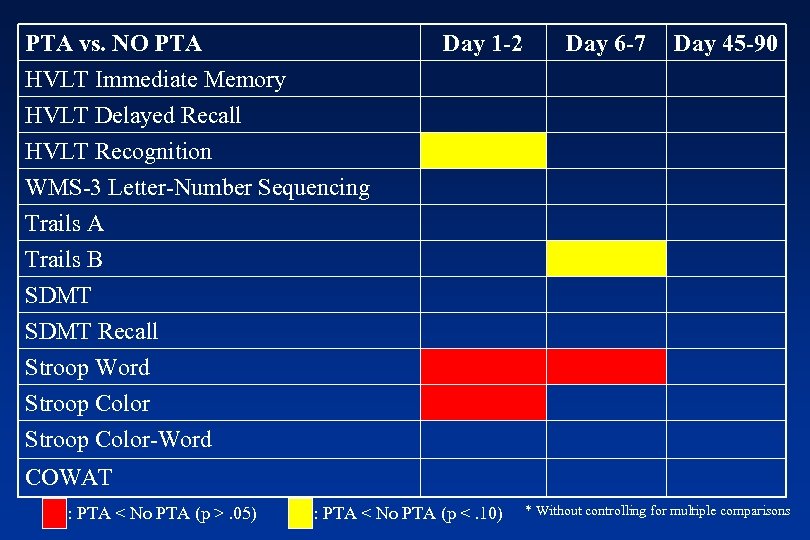

PTA vs. NO PTA HVLT Immediate Memory HVLT Delayed Recall HVLT Recognition Day 1 -2 Day 6 -7 Day 45 -90 WMS-3 Letter-Number Sequencing Trails A Trails B SDMT Recall Stroop Word Stroop Color-Word COWAT : PTA < No PTA (p >. 05) : PTA < No PTA (p <. 10) * Without controlling for multiple comparisons

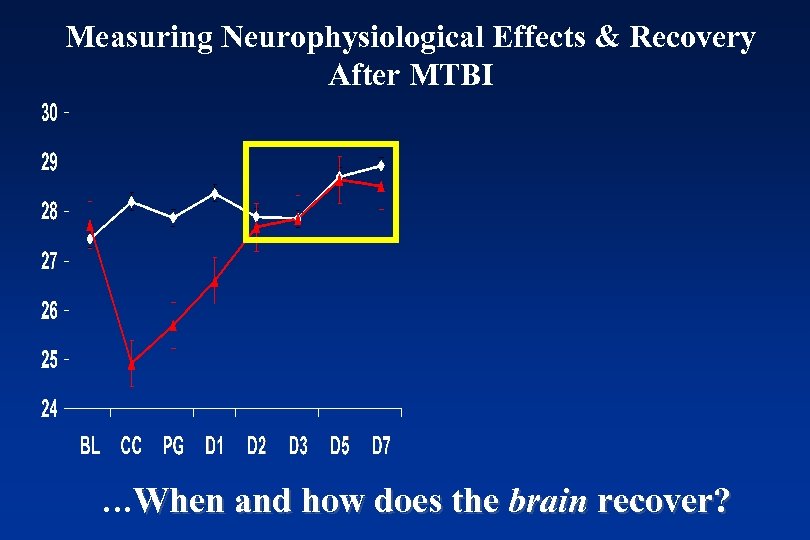

Measuring Neurophysiological Effects & Recovery After MTBI …When and how does the brain recover?

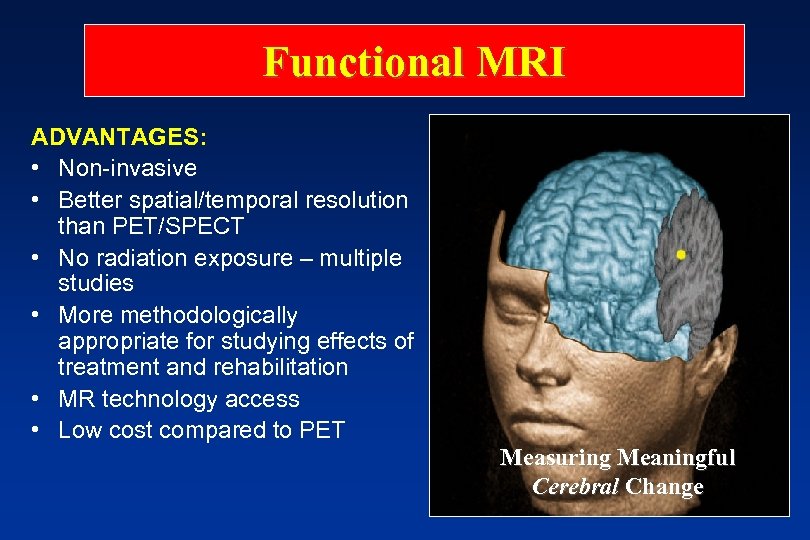

Functional MRI ADVANTAGES: • Non-invasive • Better spatial/temporal resolution than PET/SPECT • No radiation exposure – multiple studies • More methodologically appropriate for studying effects of treatment and rehabilitation • MR technology access • Low cost compared to PET Measuring Meaningful Cerebral Change

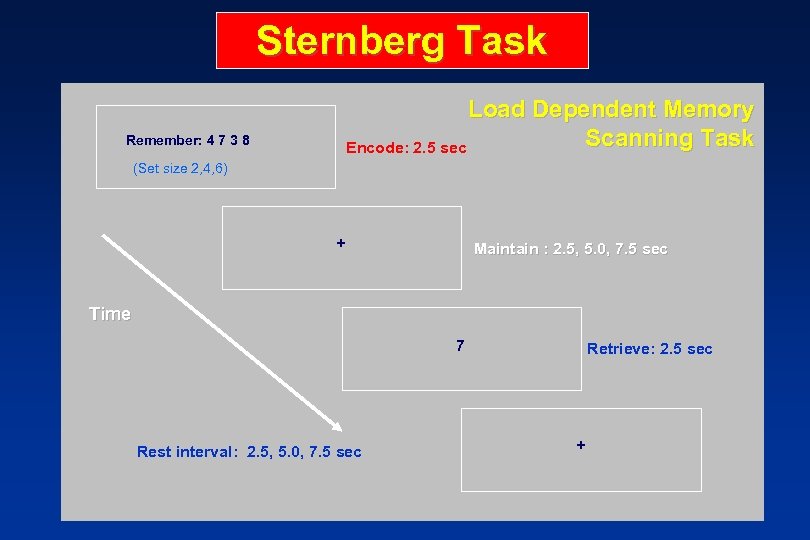

Sternberg Task Load Dependent Memory Scanning Task Encode: 2. 5 sec Remember: 4 7 3 8 (Set size 2, 4, 6) + Maintain : 2. 5, 5. 0, 7. 5 sec Time 7 Rest interval: 2. 5, 5. 0, 7. 5 sec Retrieve: 2. 5 sec +

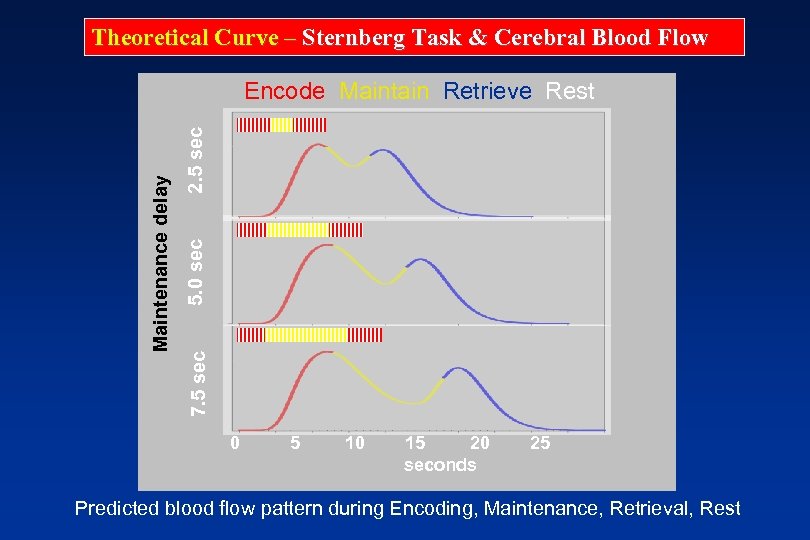

Theoretical Curve – Sternberg Task & Cerebral Blood Flow 2. 5 sec 5. 0 sec 7. 5 sec Maintenance delay Encode Maintain Retrieve Rest 0 5 10 15 20 seconds 25 Predicted blood flow pattern during Encoding, Maintenance, Retrieval, Rest

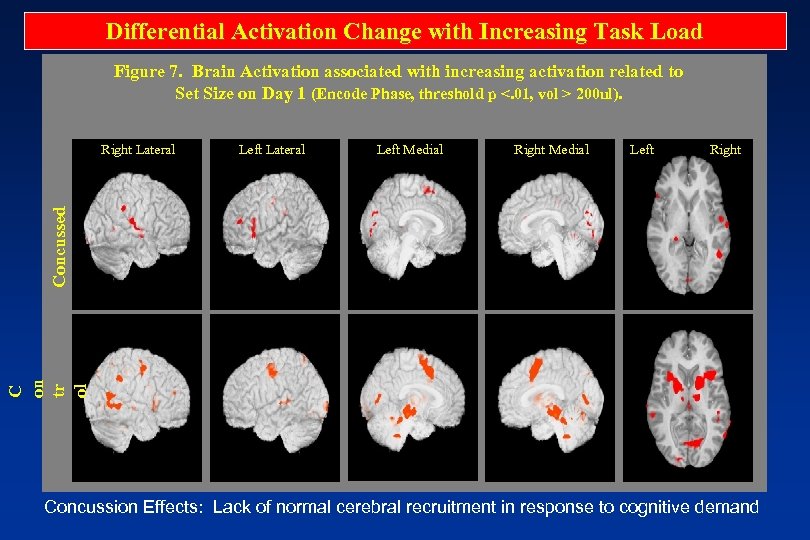

Differential Activation Change with Increasing Task Load Figure 7. Brain Activation associated with increasing activation related to Set Size on Day 1 (Encode Phase, threshold p <. 01, vol > 200 ul). Left Lateral Left Medial Right Medial Left Right C on tr ol Concussed Right Lateral Concussion Effects: Lack of normal cerebral recruitment in response to cognitive demand

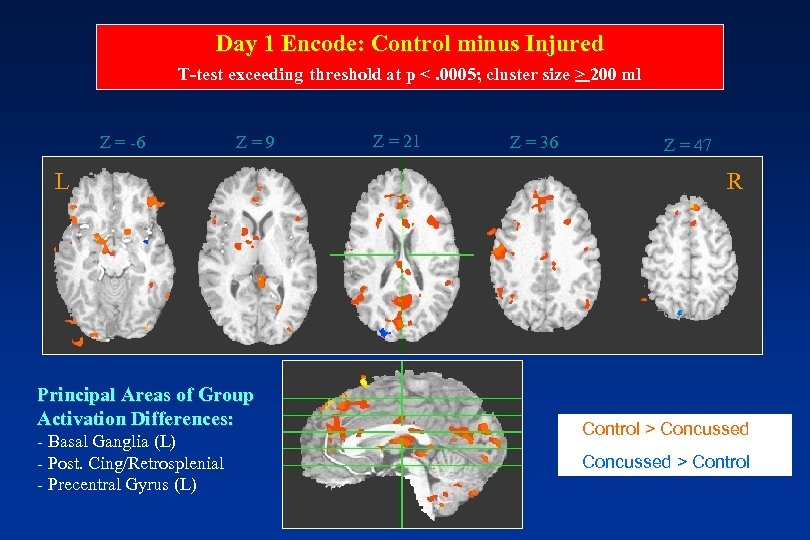

Day 1 Encode: Control minus Injured T-test exceeding threshold at p <. 0005; cluster size > 200 ml Z = -6 Z = 9 L Principal Areas of Group Activation Differences: - Basal Ganglia (L) - Post. Cing/Retrosplenial - Precentral Gyrus (L) Z = 21 Z = 36 Z = 47 R • Control > Concussed • Concussed > Control

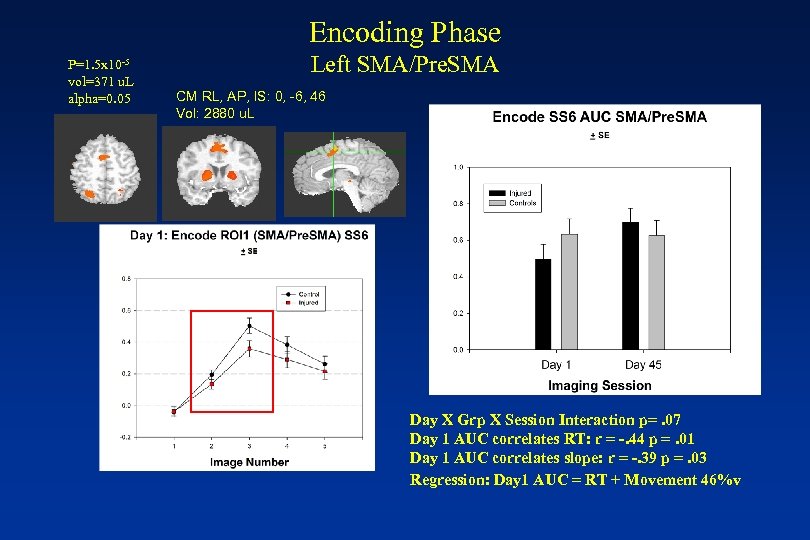

Encoding Phase P=1. 5 x 10 -5 vol=371 u. L alpha=0. 05 Left SMA/Pre. SMA CM RL, AP, IS: 0, -6, 46 Vol: 2880 u. L Day X Grp X Session Interaction p=. 07 Day 1 AUC correlates RT: r = -. 44 p =. 01 Day 1 AUC correlates slope: r = -. 39 p =. 03 Regression: Day 1 AUC = RT + Movement 46%v

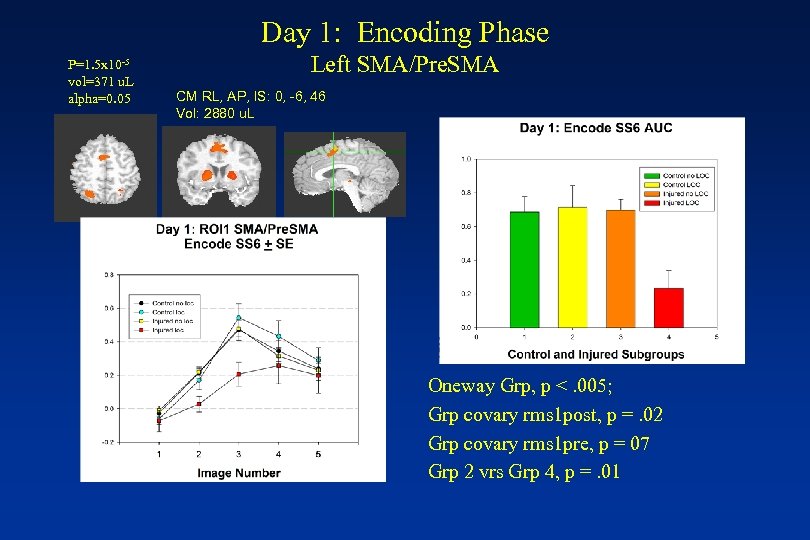

Day 1: Encoding Phase P=1. 5 x 10 -5 vol=371 u. L alpha=0. 05 Left SMA/Pre. SMA CM RL, AP, IS: 0, -6, 46 Vol: 2880 u. L Oneway Grp, p <. 005; Grp covary rms 1 post, p =. 02 Grp covary rms 1 pre, p = 07 Grp 2 vrs Grp 4, p =. 01

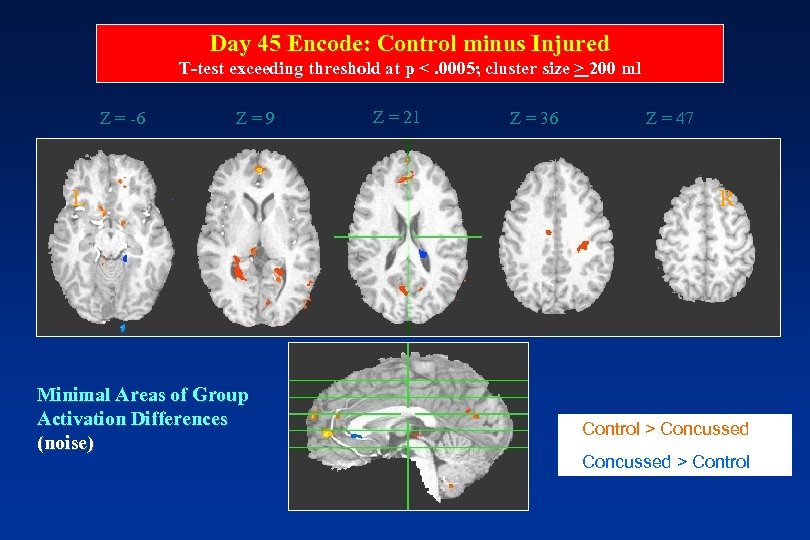

Day 45 Encode: Control minus Injured T-test exceeding threshold at p <. 0005; cluster size > 200 ml Z = -6 Z = 9 L L Minimal Areas of Group Activation Differences (noise) Z = 21 Z = 36 Z = 47 R R • Control > Concussed • Concussed > Control

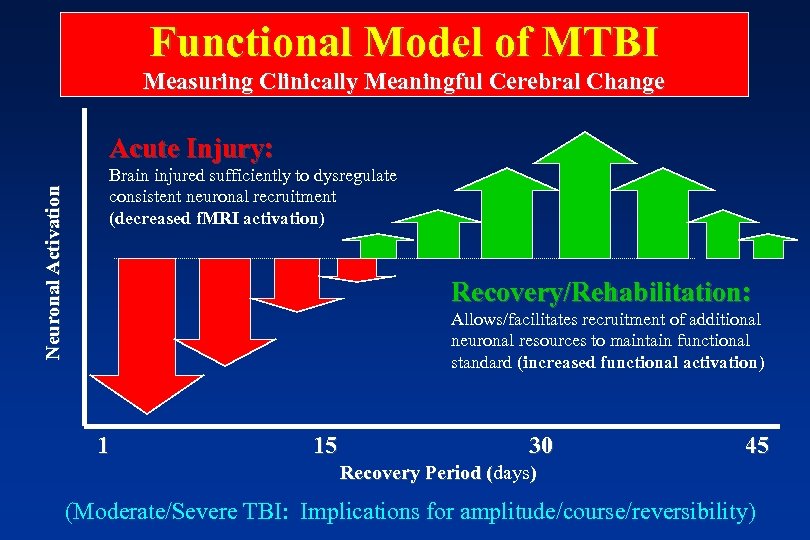

Functional Model of MTBI Measuring Clinically Meaningful Cerebral Change Neuronal Activation Acute Injury: Brain injured sufficiently to dysregulate consistent neuronal recruitment (decreased f. MRI activation) Recovery/Rehabilitation: Allows/facilitates recruitment of additional neuronal resources to maintain functional standard (increased functional activation) 1 15 30 45 Recovery Period (days) ( (Moderate/Severe TBI: Implications for amplitude/course/reversibility)

Functional Outcome After MTBI • Overwhelming majority of MTBI resume normal independent social, occupational, educational function within days to weeks of injury • Highly variable methods on RTW research • Non-injury factors associated with poor functional outcome • Higher risk of depression, anxiety (12 -44%), which receive insufficient attention

Science of MTBI Recovery • Clear, sound evidence • Kids: rapid recovery, no residual cognitive, behavioral, academic deficits • Adults: rapid symptom, cognitive recovery; no impairments 3 -12 mos • Non-injury factors predict persistent symptoms

Exceptions to the Rule? • Single, uncomplicated concussion a benign neurologic event, but…. • “Complicated” MTBI • Repeat Concussion: Immediate, mid-range, longterm risks • Second Impact Syndrome: - Mechanism, pathology, risk • Chronic effect on symptoms and cognition • Longterm Effects: What happens when they get old?

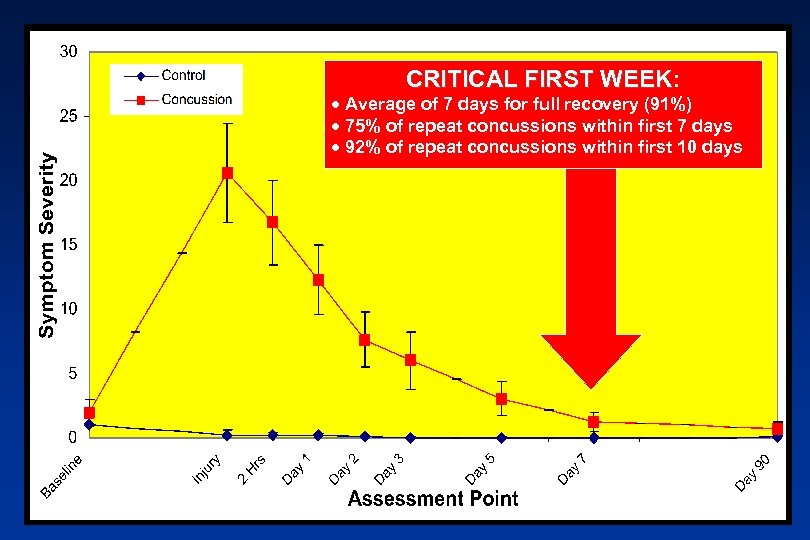

CRITICAL FIRST WEEK: WEEK · Average of 7 days for full recovery (91%) · 75% of repeat concussions within first 7 days · 92% of repeat concussions within first 10 days

What about chronic symptoms or functional impairments after repeat concussion?

Center for the Study of Retired Athletes

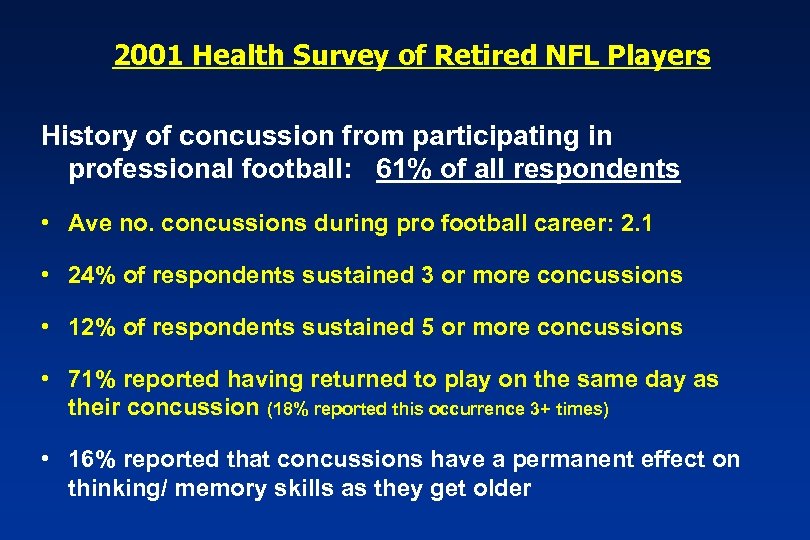

2001 Health Survey of Retired NFL Players History of concussion from participating in professional football: 61% of all respondents • Ave no. concussions during pro football career: 2. 1 • 24% of respondents sustained 3 or more concussions • 12% of respondents sustained 5 or more concussions • 71% reported having returned to play on the same day as their concussion (18% reported this occurrence 3+ times) • 16% reported that concussions have a permanent effect on thinking/ memory skills as they get older

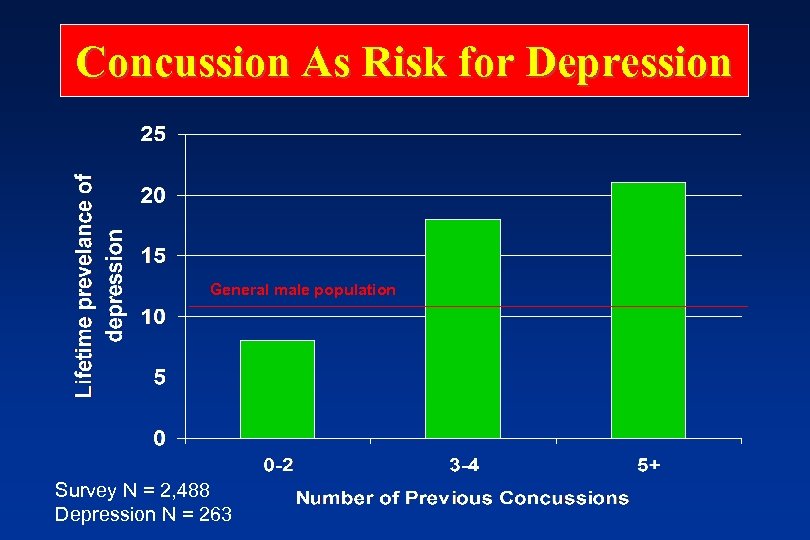

Is recurrent concussion a longterm risk for depression? • 12% of retired NFL players have had or currently have a bout with clinical depression. Of those with a history of depression: • 87% still suffer from depression • 46% currently being medically treated – “Does depression limit your activities of daily living? ” 23% = NEVER 64% = SOME 12%=OFTEN

Concussion As Risk for Depression General male population Survey N = 2, 488 Depression N = 263

Is recurrent concussion a risk factor for late life cognitive decline or dementia? “Webster was diagnosed in 1999 as having brain damage caused by repeated head injuries during his playing days. According to his doctors, several concussions damaged his frontal lobe causing cognitive dysfunction. His doctors said the progressively worsening injury caused him to behave erratically at times. ” USA TODAY 9/24/02

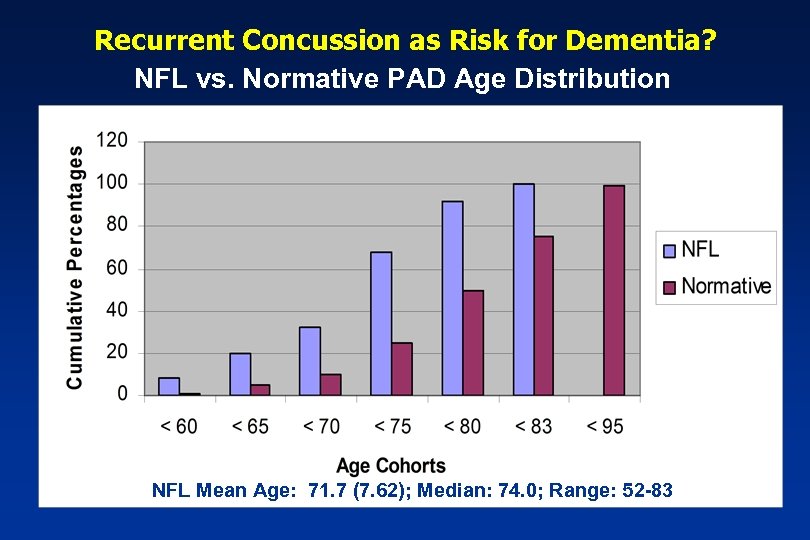

Recurrent Concussion as Risk for Dementia? NFL vs. Normative PAD Age Distribution NFL Mean Age: 71. 7 (7. 62); Median: 74. 0; Range: 52 -83

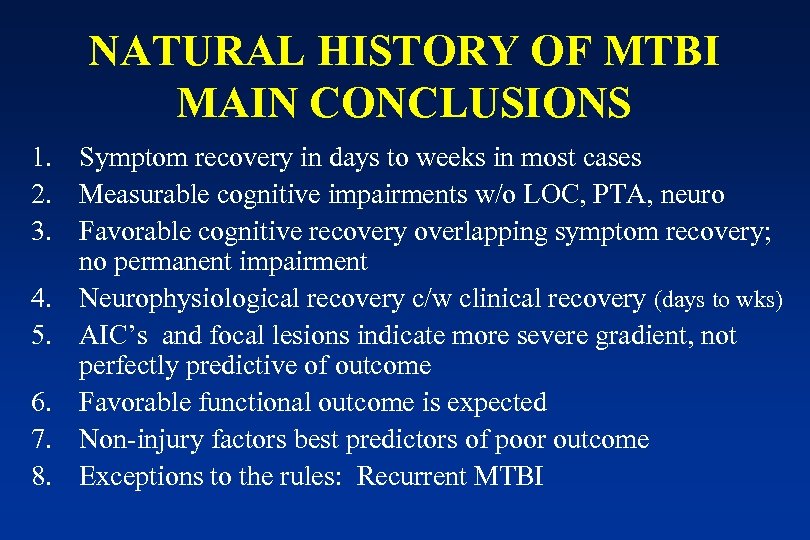

NATURAL HISTORY OF MTBI MAIN CONCLUSIONS 1. Symptom recovery in days to weeks in most cases 2. Measurable cognitive impairments w/o LOC, PTA, neuro 3. Favorable cognitive recovery overlapping symptom recovery; no permanent impairment 4. Neurophysiological recovery c/w clinical recovery (days to wks) 5. AIC’s and focal lesions indicate more severe gradient, not perfectly predictive of outcome 6. Favorable functional outcome is expected 7. Non-injury factors best predictors of poor outcome 8. Exceptions to the rules: Recurrent MTBI

Implications for Rethinking Postconcussion Syndrome

Part 4: Implications for Rethinking Postconcussion Syndrome 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Defining Postconcussion Syndrome Non-specificity of PCS Symptoms Epidemiology of PCS: Another denominator problem PCS: Neuropsychological Disorder Psychological Theories of PCS Interventional Models for PCS A practical model for clinical management of PCS Top 10 Conclusions

What is “PCS”? • ICD-10: F 07. 2 (part of class of disorders with “a demonstrable etiology in cerebral disease, brain injury, or other insult leading to cerebral dysfunction”). – Def: A syndrome that occurs following head trauma (usually sufficiently severe to result in loss of consciousness) and includes a number of disparate symptoms such as headache, dizziness, fatigue, irritability, difficulty in concentration and performing mental tasks, impairment of memory, insomnia, and reduced tolerance to stress, emotional excitement, or alcohol.

What is “PCS”? • DSM-IV- proposed new category: – A. History of a head trauma that has caused significant concussion (loc, pta, sz) – B. Evidence from neuropsychological testing of impaired attention or memory – C. Three or more occur shortly post-injury and persist for at least 3 months: • • Headache Dizziness Irritability Fatigue Anxiety, depression, or emotional lability Sleep disturbance Personality change Apathy

Non-specificity of PCS symptoms • Symptoms are not specific to concussion/TBI; e. g. : – Trahan et al, 2001: Pts with depression endorse significantly more PCS Sxs than pts with m. TBI. – Lees-Haley et al, 2001: Non-TBI personal injury claimants endorse PCS symptomatology at high rates, comparable on many symptoms to m. TBI claimants (e. g. , concentration impairments 63% m. TBI, 65% other). – Iverson & Mc. Kraken, 1997: Chronic pain pts endorse PCS Sxs at high rate (81% endorsing 3+ symptoms) – Gouvier et al. , 1988: High base rates of “PCS” symptoms in normal (college) population

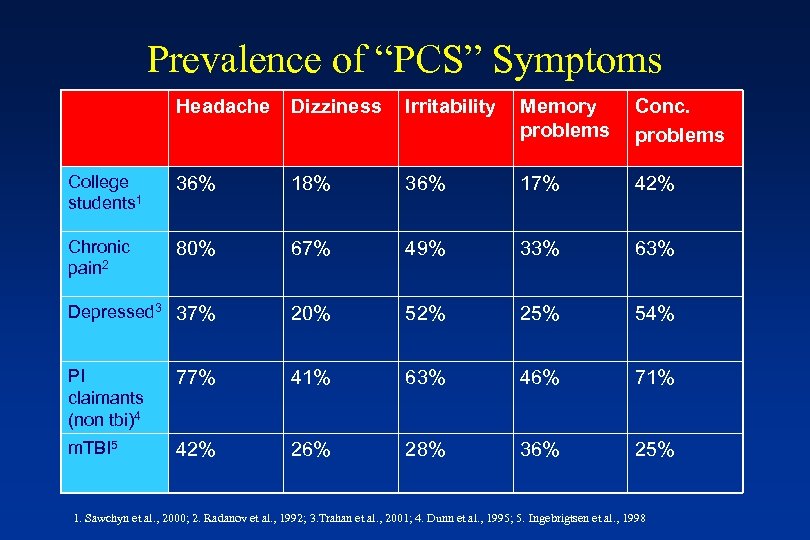

Prevalence of “PCS” Symptoms Headache Dizziness Irritability Memory problems Conc. problems College students 1 36% 18% 36% 17% 42% Chronic pain 2 80% 67% 49% 33% 63% Depressed 3 37% 20% 52% 25% 54% PI claimants (non tbi)4 77% 41% 63% 46% 71% m. TBI 5 42% 26% 28% 36% 25% 1. Sawchyn et al. , 2000; 2. Radanov et al. , 1992; 3. Trahan et al. , 2001; 4. Dunn et al. , 1995; 5. Ingebrigtsen et al. , 1998

Reliability & Validity of PCS Criteria • Boake et al (2004): agreement b/n DSM and ICD symptom criteria, poor overall agreement because few patients met criteria for cognitive deficit and clinical significance Conclusion: limited agreement b/n diagnostic systems leading to different diagnosis and treatment in the same case • Boake et al. (2005): At 3 mos, higher prevalence of PCS with ICD-10 (64%) than DSM-IV (11%); 40% of non-TBI sample met ICD criteria, 7% for DSM; Conclusion: PCS symptoms are not sufficient to make the diagnosis of MTBI; linking residual symptoms to TBI is a major problem • Kashluba et al (2006): ICD-10 PCS symptoms unable to accurately classify MTBI patients from NC’s at 3 months

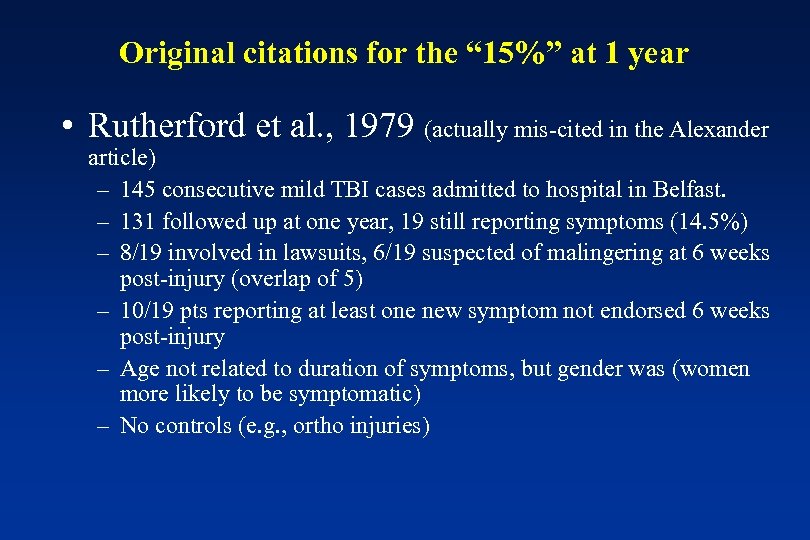

What’s the incidence of “PCS”? • Epidemiology? – Frequent citation of influential Alexander (1995 Neurology) review article: “at one year after injury approximately 15% of [mild TBI] patients still have disabling symptoms” – Articles referenced for this figure are Rutherford et al. , 1978; Mc. Lean et al. , 1983. • This figure and these citations echoed in multiple publications, but…. .

Original citations for the “ 15%” at 1 year • Rutherford et al. , 1979 (actually mis-cited in the Alexander article) – 145 consecutive mild TBI cases admitted to hospital in Belfast. – 131 followed up at one year, 19 still reporting symptoms (14. 5%) – 8/19 involved in lawsuits, 6/19 suspected of malingering at 6 weeks post-injury (overlap of 5) – 10/19 pts reporting at least one new symptom not endorsed 6 weeks post-injury – Age not related to duration of symptoms, but gender was (women more likely to be symptomatic) – No controls (e. g. , ortho injuries)

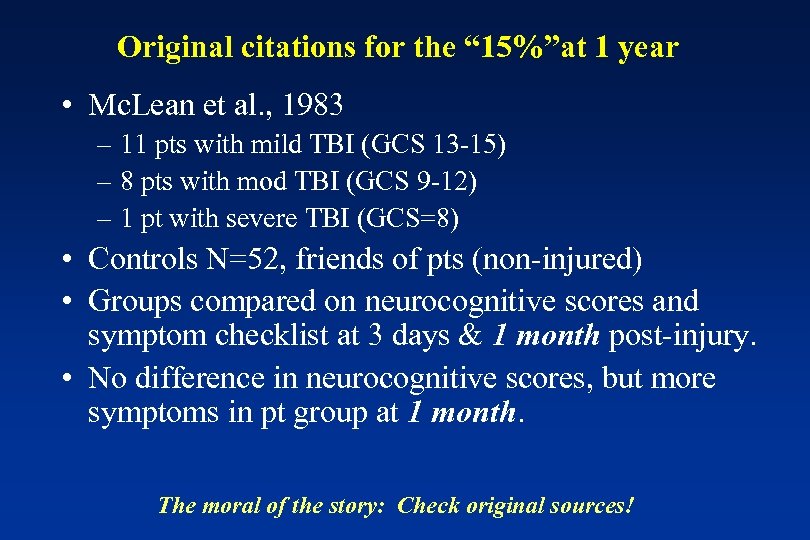

Original citations for the “ 15%”at 1 year • Mc. Lean et al. , 1983 – 11 pts with mild TBI (GCS 13 -15) – 8 pts with mod TBI (GCS 9 -12) – 1 pt with severe TBI (GCS=8) • Controls N=52, friends of pts (non-injured) • Groups compared on neurocognitive scores and symptom checklist at 3 days & 1 month post-injury. • No difference in neurocognitive scores, but more symptoms in pt group at 1 month. The moral of the story: Check original sources!

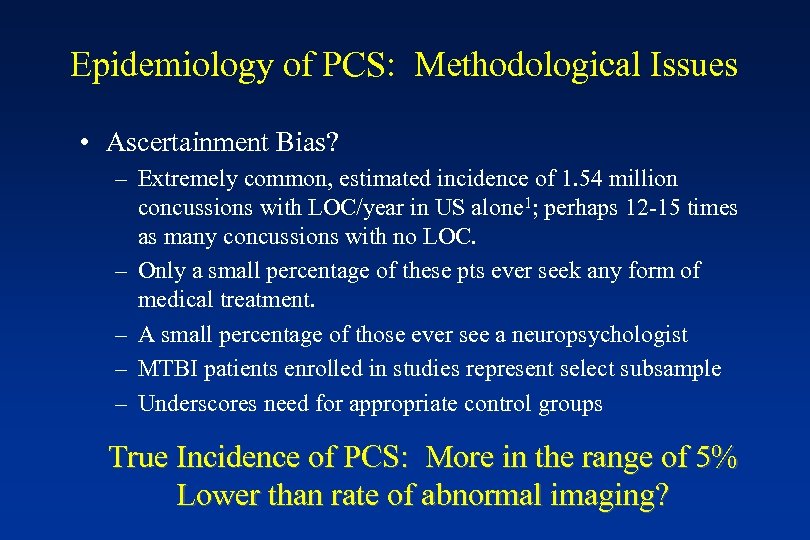

Epidemiology of PCS: Methodological Issues • Ascertainment Bias? – Extremely common, estimated incidence of 1. 54 million concussions with LOC/year in US alone 1; perhaps 12 -15 times as many concussions with no LOC. – Only a small percentage of these pts ever seek any form of medical treatment. – A small percentage of those ever see a neuropsychologist – MTBI patients enrolled in studies represent select subsample – Underscores need for appropriate control groups True Incidence of PCS: More in the range of 5% Lower than rate of abnormal imaging?

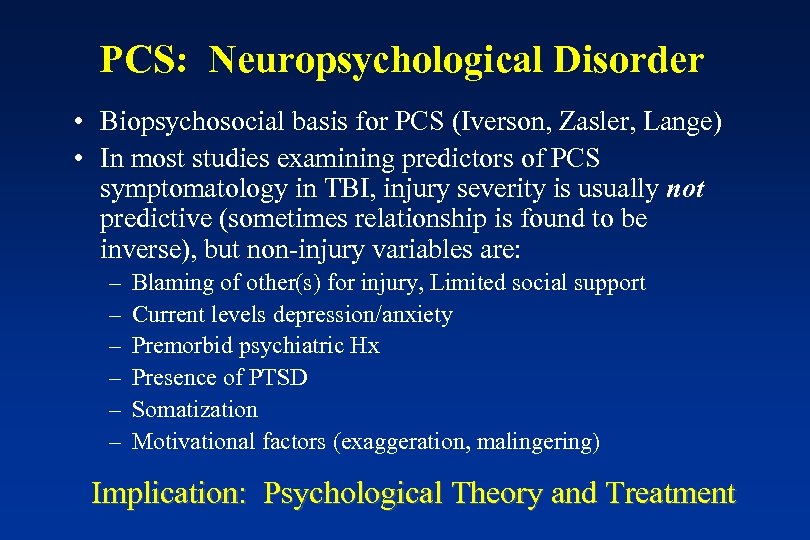

PCS: Neuropsychological Disorder • Biopsychosocial basis for PCS (Iverson, Zasler, Lange) • In most studies examining predictors of PCS symptomatology in TBI, injury severity is usually not predictive (sometimes relationship is found to be inverse), but non-injury variables are: – – – Blaming of other(s) for injury, Limited social support Current levels depression/anxiety Premorbid psychiatric Hx Presence of PTSD Somatization Motivational factors (exaggeration, malingering) Implication: Psychological Theory and Treatment

Psychological Theories of PCS • Expectation as Etiology: preformed expectations about effects of head injury, misattribute common complaints to head injury • “Good Old Days” Hypothesis: EAE + consideration that people attribute all sx’s to negative event • Nocebo Effect: expectations of sickness and associated emotional distress cause the sickness in question • Diasthesis-Stress Model: interaction b/n physiological, psychological, motivational and iatrogenic factors Implication: Psychological Intervention

Efficacy of Psychological Intervention for PCS • Mittenberg et al. (1996): 58 subjects with m. TBI, randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups: – Treatment: given printed educational material and met once (1 hr) prior to discharge with therapist – Control- normal hospital treatment and discharge instructions • 6 -month follow-up by blinded interviewer (no baseline Sx differences)…

Efficacy of Psychological Intervention for PCS • Treatment group reported significantly shorter mean symptom duration (33 vs 51 days), fewer symptoms, and less severe symptoms • Results suggest that brief, early psychological intervention can minimize “PCS” • Additional studies…

Efficacy of Psychological Intervention for PCS • Ponsford et al. , (2002): 202 adults with m. TBI, 79 assigned to intervention within one week of injury: – Intervention consisted only of informational booklet re expected natural history of symptoms and coping strategies • At 3 months post-injury, intervention group reported fewer overall symptoms and less current stress • Similar findings from Minderhoud et al. (1980), Relander et al. (1972), Wade et al. , (1998), Paniak et al. , 2000, Ponsford et al. , 2001.

WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury • Results of survey of nonsurgical interventions and cost for m. TBI (J Rehabil Med 2004): – “Evidence that early intervention can reduce long-term complaints, and that this intervention need not be intensive. ”

Postconcussion Syndrome: Main Conclusions 1. Sx-Based diagnosis of PCS problematic (poor reliability of criteria, nonspecificity of sx’s) 2. PCS estimates severely inflated; true incidence ~ 1 -5% 3. Frequency of structural injury higher than PCS 4. Science to rethink PCS: Neuropsychological Disorder 5. Psychological bases indicates psychological and educational interventions 6. Effective intervention will improve functional outcome and reduce disability from PCS 7. Need to rule out motivational factors 8. Neuropsychologists the key component

Warning: Commercial Re-Run 1. MTBI, more than any other clinical entity, is a neuropsychological construct 2. The contribution by neuropsychologists to MTBI research is unmatched by any other discipline 3. Neuropsychologists are uniquely suited to evaluate and treat MTBI 4. Neuropsychologists should not limit their role in MTBI just to neuropsych testing

Neuropsych Consult: STAT • EMS education • ED consultation • Acute TBI Clinic • Multidisciplinary Approach • Neuropsychology & PM/R • Patient/family education • Supportive follow-up • Outcome research

Neuropsychology’s Response • AAN Position Statement: Where are neuropsychology and rehabilitation psychology? • Military MTBI Task Force: Inter-organizational collaboration between: - APA Division 40 - APA Division 22 - American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology - National Academy of Neuropsychology • Military, VA, Civilian Psychologists • Position statement and call to action Anyone up for a drink and some chatter?

Contact Information • Michael Mc. Crea, Ph. D, ABPP-CN Neuropsychology Service Waukesha Memorial Hospital 721 American Avenue, Suite 501 Waukesha Memorial Hospital Waukesha, WI 53188 Office: 262 -928 -2156 Fax: 262 -928 -5580 Email: michael. mccrea@phci. org

8438e9facca75c8cec7567066f41480f.ppt