MIDDLE ENGLISH OUTLINE 1. Historical Background from the

MIDDLE ENGLISH

OUTLINE 1. Historical Background from the 11th to 15th c. - Scandinavian Invasion - Norman Conquest 2. Middle English dialects. The London dialect 3. Written records in Middle English. The age of Chaucer 4. Spelling changes in Middle English. Rules of reading 5. Changes in the phonetic system in Middle English 6. Changes in the nominal system in Middle English 7. Changes in the verbal system in Middle English 8. Middle English vocabulary

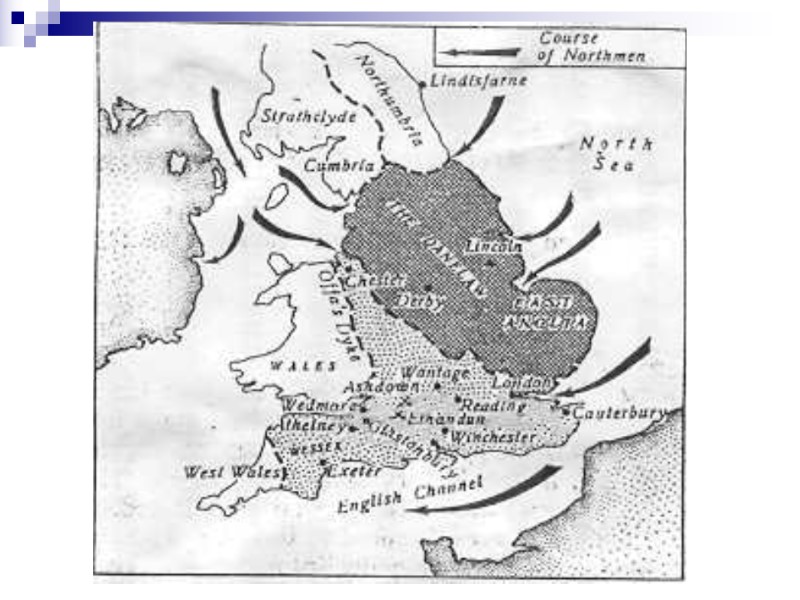

The influence of the Scandinavian invasion changes in different spheres of the English language: word-stock, grammar and phonetics; the influence of Scandinavian dialects was especially felt in the North and East parts of England, where mass settlement of the invaders and intermarriages with the local population were especially common.

The influence of the Scandinavian invasion The relative ease of the mutual penetration of the languages was conditioned by the circumstances of the Anglo-Scandinavian contacts: There were no political or social barriers between the English and the Scandinavians, the latter not having formed the ruling class of the society but living on an equal footing with the English; 2) There were no cultural barriers between the two peoples as they were approximately the same in their culture, habits and customs due to their common origin, both of the nations being Germanic. 3) The language difference was not so strong as to make their mutual understanding impossible, as their speech developed from the same source — Common Germanic, and the words composing the basic word-stock of both the languages were the same, and the grammar systems similar in essence.

In Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Northumberland, Cumberland up to 75% of the place-names are Danish or Norwegian. More than 1400 English villages and towns bear names of Scandinavian origin: e.g. Woodthorp, Linthorp, etc. – with the element thorp meaning “village”; Brimtoft, Lowestoft, etc. – with the element toft “a piece of land”

Norman Conquest began in 1066. The Normans were by origin a Scandinavian tribe who two centuries back began their inroads on the Northern part of France and finally occupied the territory on both shores of the Seine. The French King Charles the Simple ceded to the Normans the territory occupied by them, which came to be called Normandy. The Normans adopted the French language and culture, and when they came to Britain they brought with them the French language.

The influence of the Norman Conquest The English language emerged after the struggle, but it came in a different position. Its vocabulary was enriched by a great number of French words and its grammatical structure underwent material changes. the following decisive steps in the way upward of the English language after the Norman conquest: - 1258 - Proclamation of King Henry III was published besides French also in English; - 1362 - the English language became the language of Parliament, courts of law; later, at the end of the century - the language of teaching; - the rule of King Henry IV (1399—1413) - the first king after the conquest whose native tongue was English.

Middle English Dialects

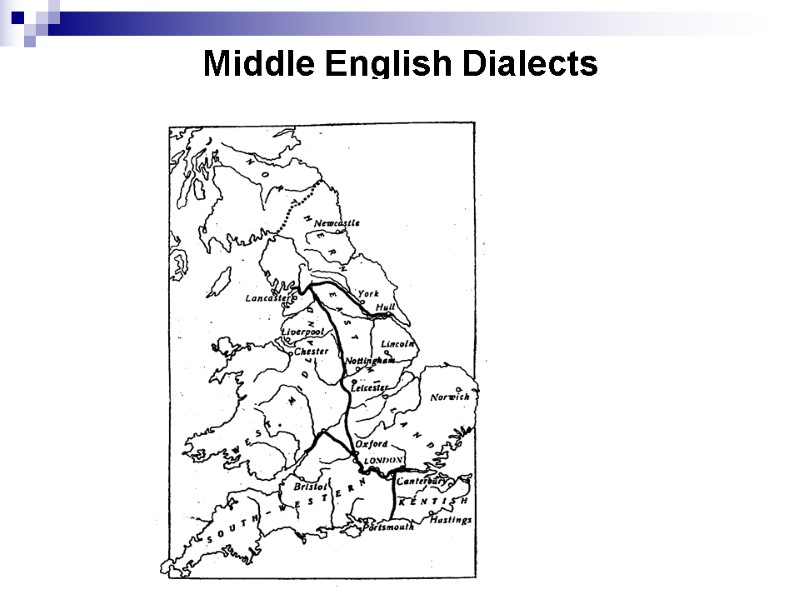

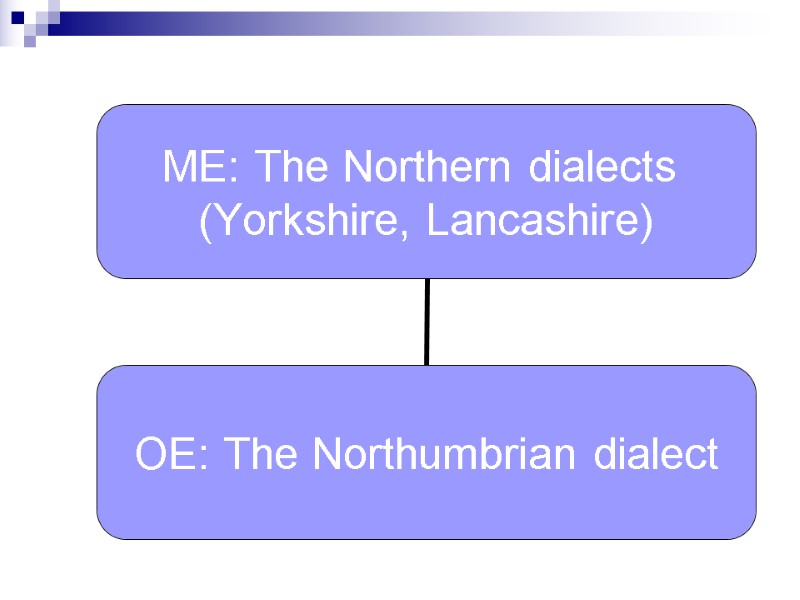

Middle English Dialects Southern dialects Midland ("Central") dialects Northern dialects

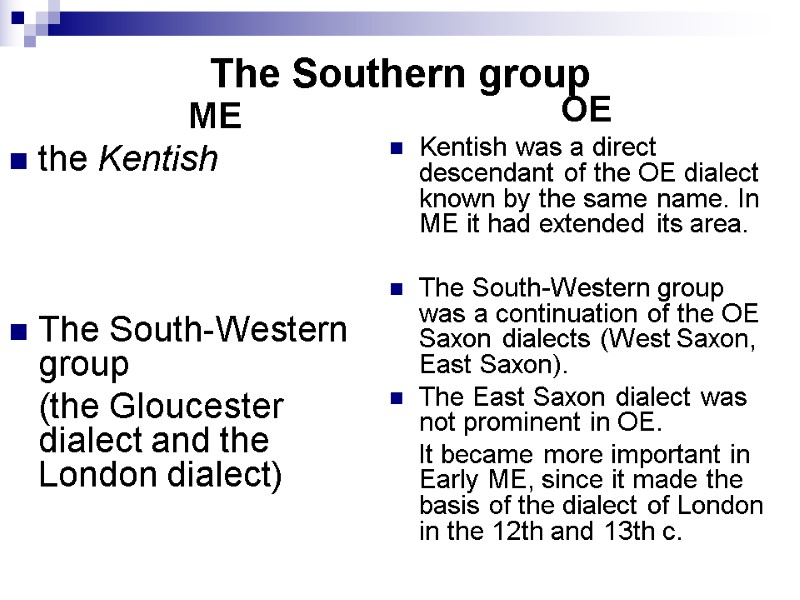

The Southern group ME the Kentish The South-Western group (the Gloucester dialect and the London dialect) OE Kentish was a direct descendant of the OE dialect known by the same name. In ME it had extended its area. The South-Western group was a continuation of the OE Saxon dialects (West Saxon, East Saxon). The East Saxon dialect was not prominent in OE. It became more important in Early ME, since it made the basis of the dialect of London in the 12th and 13th c.

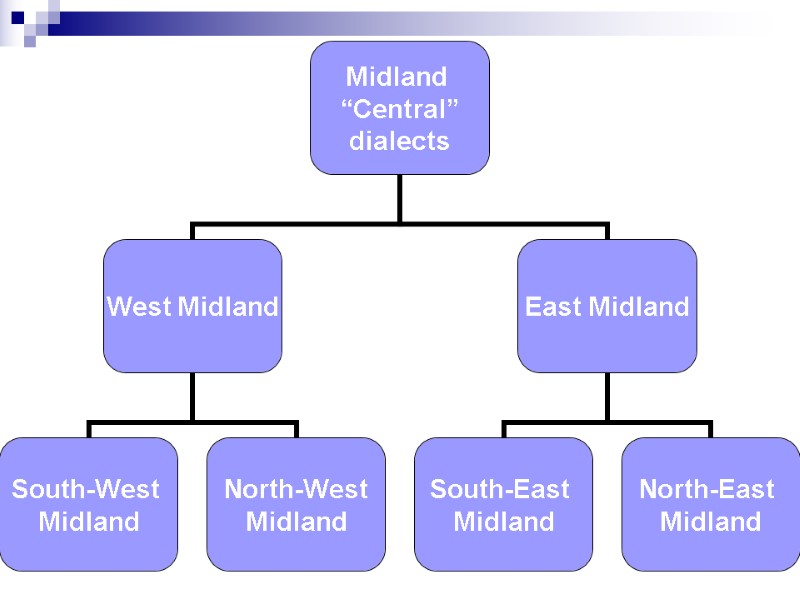

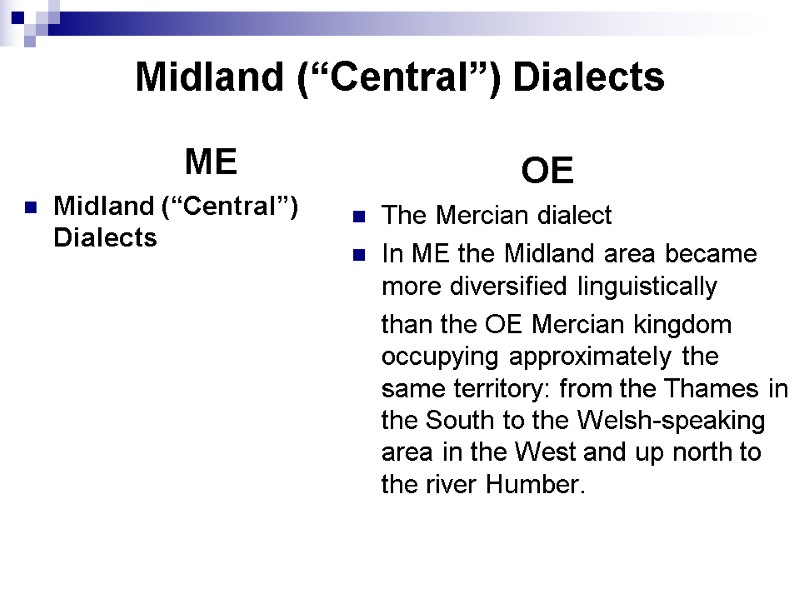

Midland (“Central”) Dialects ME Midland (“Central”) Dialects OE The Mercian dialect In ME the Midland area became more diversified linguistically than the OE Mercian kingdom occupying approximately the same territory: from the Thames in the South to the Welsh-speaking area in the West and up north to the river Humber.

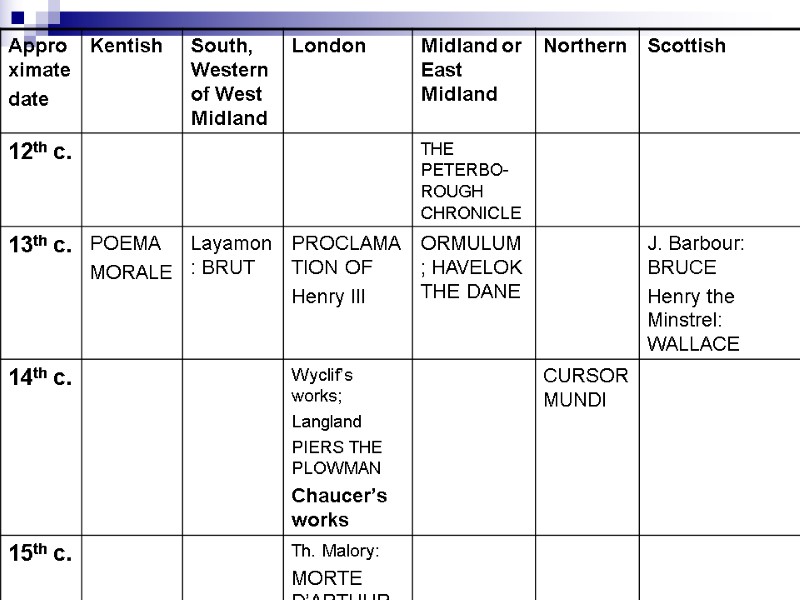

Principal Middle English Written Records

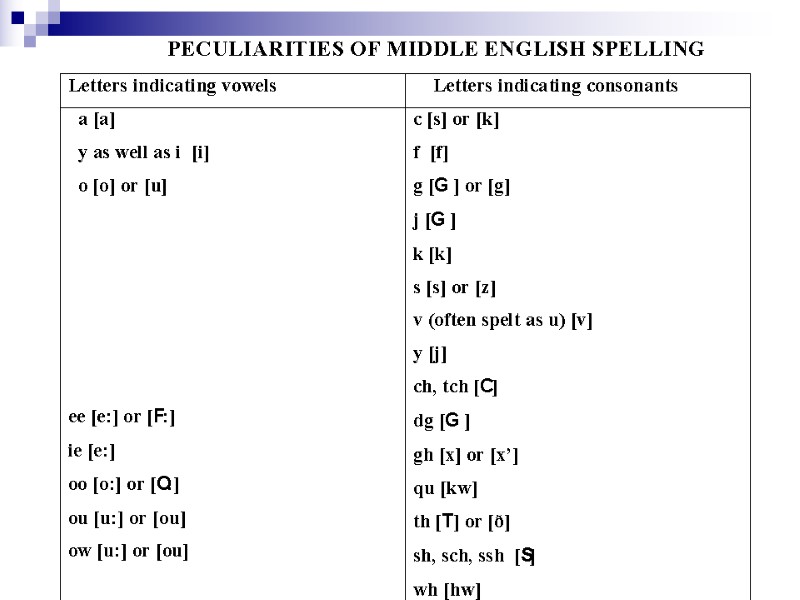

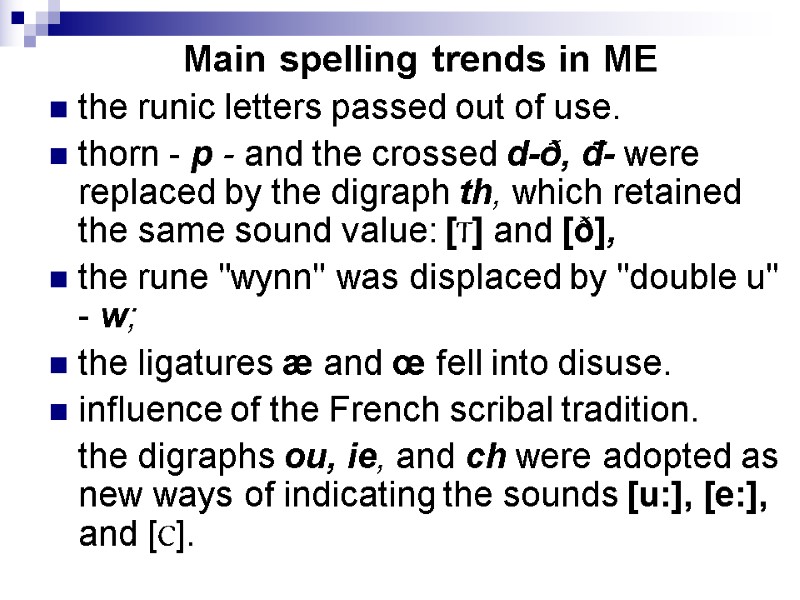

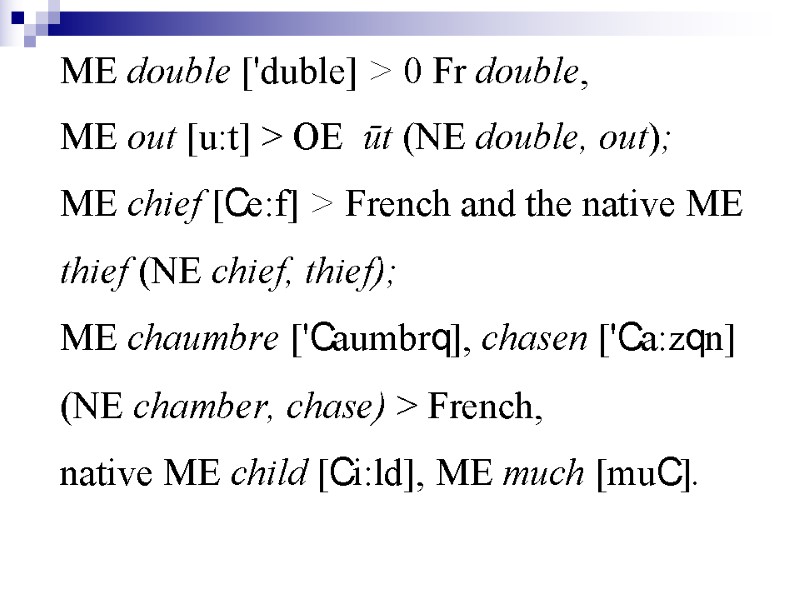

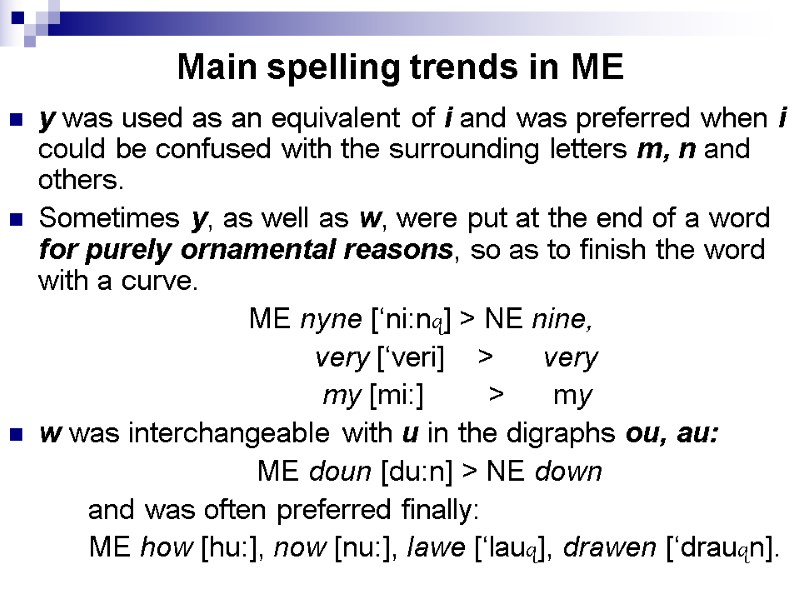

Main spelling trends in ME the runic letters passed out of use. thorn - p - and the crossed d-ð, đ- were replaced by the digraph th, which retained the same sound value: [T] and [ð], the rune "wynn" was displaced by "double u" - w; the ligatures æ and œ fell into disuse. influence of the French scribal tradition. the digraphs ou, ie, and ch were adopted as new ways of indicating the sounds [u:], [e:], and [C].

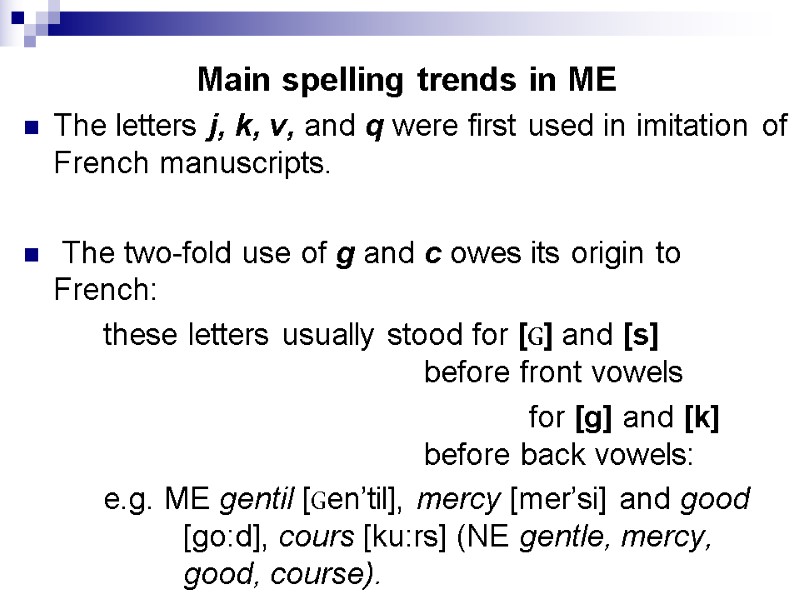

Main spelling trends in ME The letters j, k, v, and q were first used in imitation of French manuscripts. The two-fold use of g and c owes its origin to French: these letters usually stood for [G] and [s] before front vowels for [g] and [k] before back vowels: e.g. ME gentil [Gen’til], mercy [mer’si] and good [go:d], cours [ku:rs] (NE gentle, mercy, good, course).

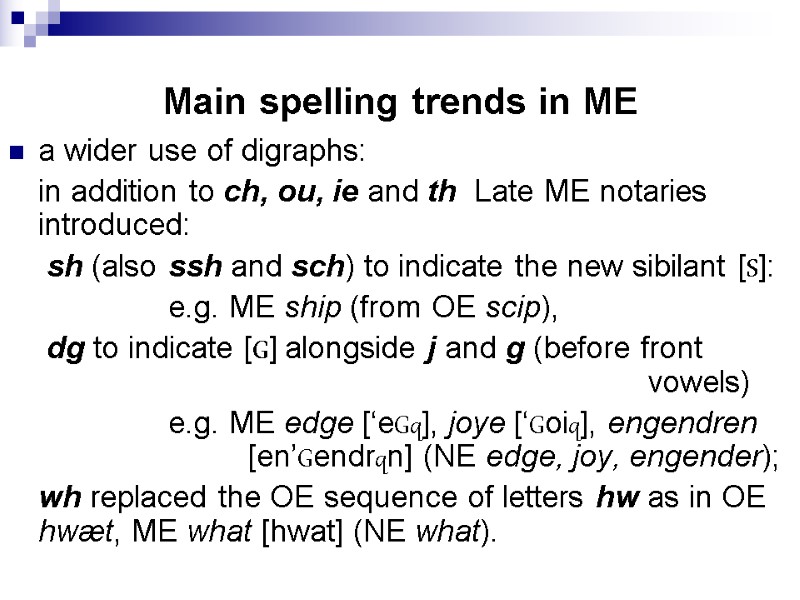

a wider use of digraphs: in addition to ch, ou, ie and th Late ME notaries introduced: sh (also ssh and sch) to indicate the new sibilant [S]: e.g. ME ship (from OE scip), dg to indicate [G] alongside j and g (before front vowels) e.g. ME edge [‘eGq], joye [‘Goiq], engendren [en’Gendrqn] (NE edge, joy, engender); wh replaced the OE sequence of letters hw as in OE hwæt, ME what [hwat] (NE what). Main spelling trends in ME

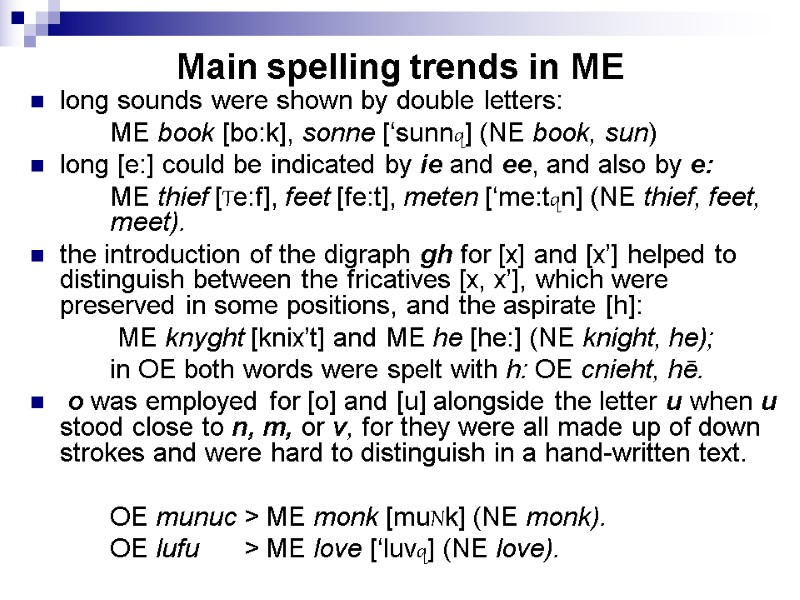

Main spelling trends in ME long sounds were shown by double letters: ME book [bo:k], sonne [‘sunnq] (NE book, sun) long [e:] could be indicated by ie and ee, and also by e: ME thief [Te:f], feet [fe:t], meten [‘me:tqn] (NE thief, feet, meet). the introduction of the digraph gh for [x] and [x’] helped to distinguish between the fricatives [x, x’], which were preserved in some positions, and the aspirate [h]: ME knyght [knix’t] and ME he [he:] (NE knight, he); in OE both words were spelt with h: OE cnieht, hē. o was employed for [o] and [u] alongside the letter u when u stood close to n, m, or v, for they were all made up of down strokes and were hard to distinguish in a hand-written text. OE munuc > ME monk [muNk] (NE monk). OE lufu > ME love [‘luvq] (NE love).

Main spelling trends in ME y was used as an equivalent of i and was preferred when i could be confused with the surrounding letters m, n and others. Sometimes y, as well as w, were put at the end of a word for purely ornamental reasons, so as to finish the word with a curve. ME nyne [‘ni:nq] > NE nine, very [‘veri] > very my [mi:] > my w was interchangeable with u in the digraphs ou, au: ME doun [du:n] > NE down and was often preferred finally: ME how [hu:], now [nu:], lawe [‘lauq], drawen [‘drauqn].

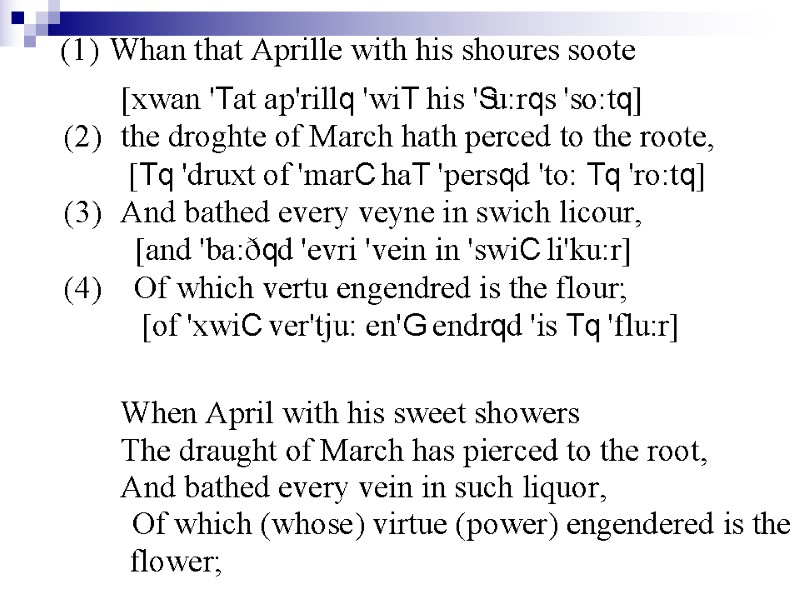

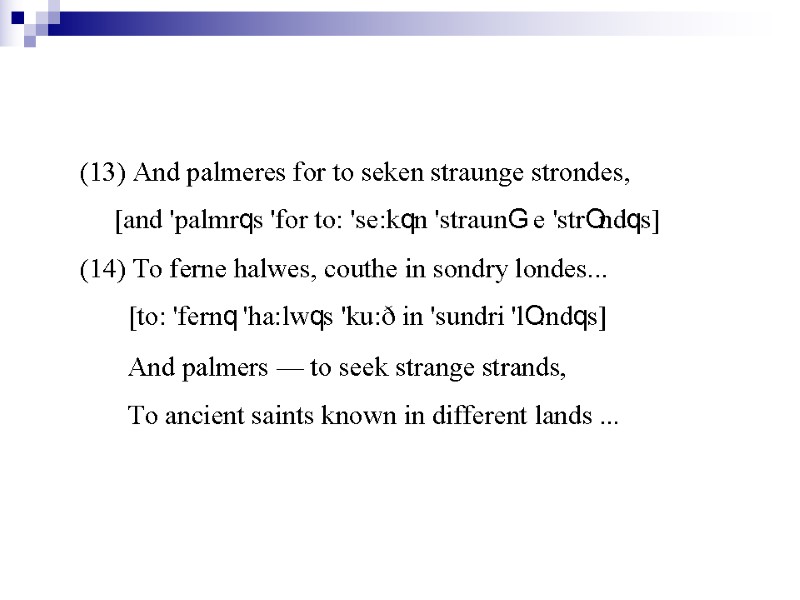

(5) Whan Zephirus eek with his swete breeth [xwan 'zefi ‘rus F:k 'wiT his 'swe:tq 'brF:T] (6) Inspired hath in every holt and heeth [in’spirqd ‘haT in 'evri 'hO:lt and 'hF:T] (7) The tendre croppes, and the younge sonne [Tq 'tendrq ' kroppqs 'and Tq 'jungq 'sunnq] (8) Hath in the Ram his halve cours y-ronne, [haT ‘in Tq ram his 'halvq 'kurs i-'runnq] When Zephyr also with his sweet breath Inspired has into every holt and heath The tender crops, and the young sun Has in the Ram half his course run (has passed half of its way in the constellation of Ram).

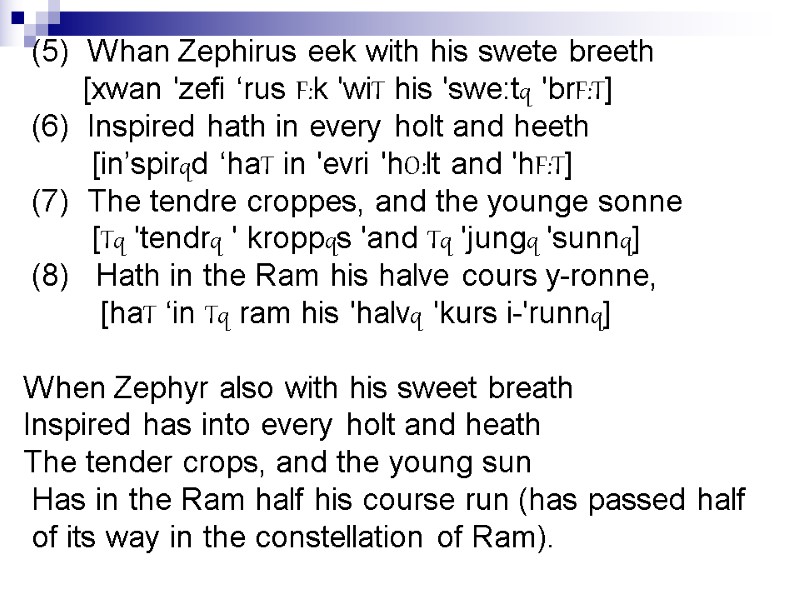

(9) And smale foweles maken melodye, [and 'smalq 'fu:lqs 'ma:kqn 'melo'diq] (10) That slepen al the nyght with open ye — [Tat 'slF:pqn 'al T q 'nix't wiT 'o:pqn 'i:e] (11) So priketh hem nature in here corages— [sO: 'prikqT 'hem na'tju:r in 'her ku'raGqs] (12) Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages, [Tan 'loNgqn 'folk to: 'go:n on 'pilgri'maGqs] And small birds sing (lit. fowls make melody) That sleep all the night with open eyes (i.e. do not sleep) - So raises nature their spirit (lit. pricks their courage)— Then folks long to go on pilgrimages,

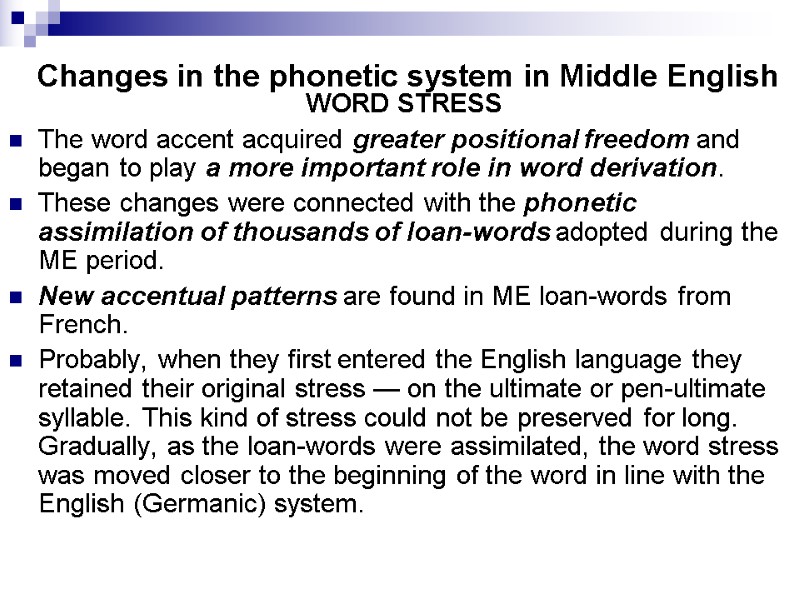

Changes in the phonetic system in Middle English WORD STRESS The word accent acquired greater positional freedom and began to play a more important role in word derivation. These changes were connected with the phonetic assimilation of thousands of loan-words adopted during the ME period. New accentual patterns are found in ME loan-words from French. Probably, when they first entered the English language they retained their original stress — on the ultimate or pen-ultimate syllable. This kind of stress could not be preserved for long. Gradually, as the loan-words were assimilated, the word stress was moved closer to the beginning of the word in line with the English (Germanic) system.

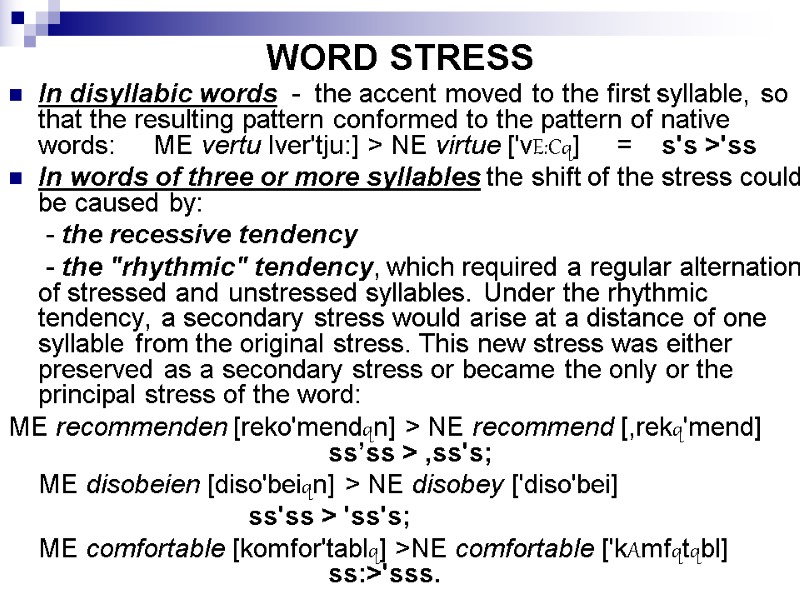

WORD STRESS In disyllabic words - the accent moved to the first syllable, so that the resulting pattern conformed to the pattern of native words: ME vertu Iver'tju:] > NE virtue ['vE:Cq] = s's >'ss In words of three or more syllables the shift of the stress could be caused by: - the recessive tendency - the "rhythmic" tendency, which required a regular alternation of stressed and unstressed syllables. Under the rhythmic tendency, a secondary stress would arise at a distance of one syllable from the original stress. This new stress was either preserved as a secondary stress or became the only or the principal stress of the word: ME recommenden [reko'mendqn] > NE recommend [,rekq'mend] ss’ss > ,ss's; ME disobeien [diso'beiqn] > NE disobey ['diso'bei] ss'ss > 'ss's; ME comfortable [komfor'tablq] >NE comfortable ['kAmfqtqbl] ss:>'sss.

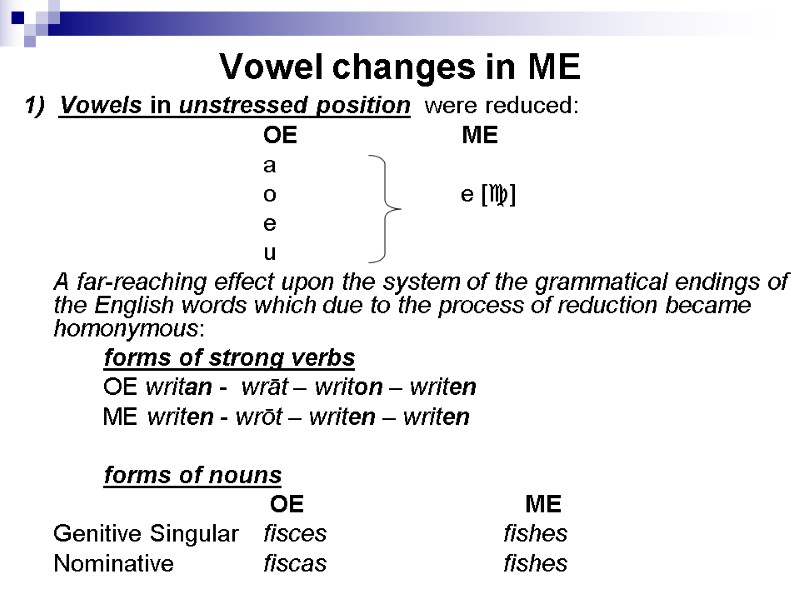

Vowel changes in ME 1) Vowels in unstressed position were reduced: OE ME a o e [] e u A far-reaching effect upon the system of the grammatical endings of the English words which due to the process of reduction became homonymous: forms of strong verbs OE writan - wrāt – writon – writen ME writen - wrōt – writen – writen forms of nouns OE ME Genitive Singular fisces fishes Nominative fiscas fishes

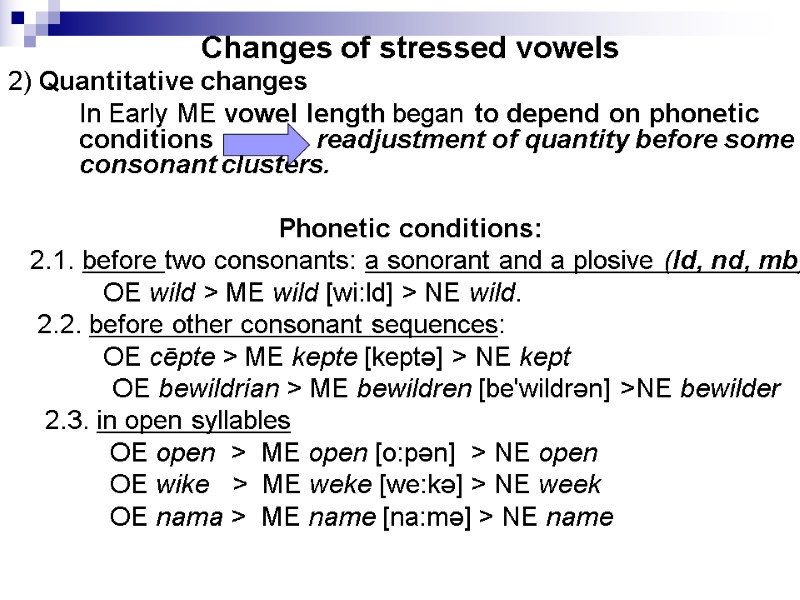

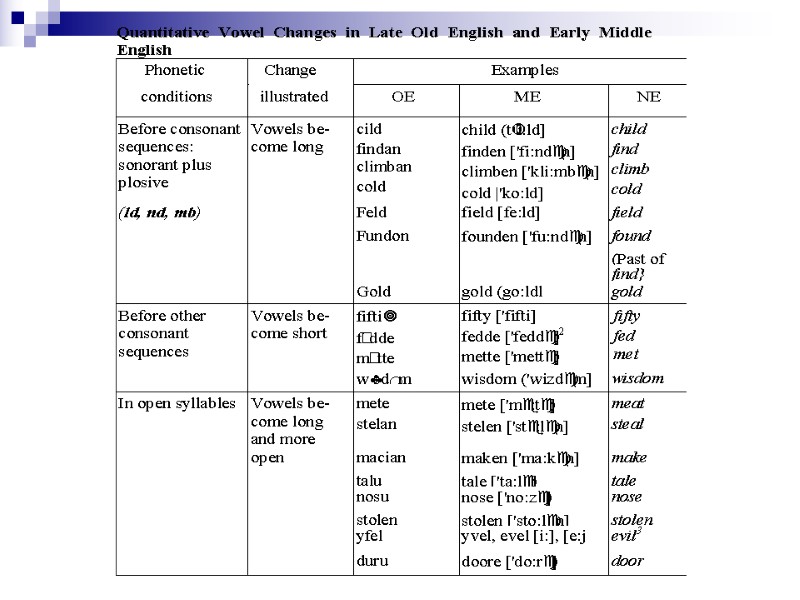

Changes of stressed vowels 2) Quantitative changes In Early ME vowel length began to depend on phonetic conditions readjustment of quantity before some consonant clusters. Phonetic conditions: 2.1. before two consonants: a sonorant and a plosive (ld, nd, mb): OE wild > ME wild [wi:ld] > NE wild. 2.2. before other consonant sequences: OE cēpte > ME kepte [keptə] > NE kept OE bewildrian > ME bewildren [be'wildrən] >NE bewilder 2.3. in open syllables OE open > ME open [o:pən] > NE open OE wike > ME weke [we:kə] > NE week OE nama > ME name [na:mə] > NE name

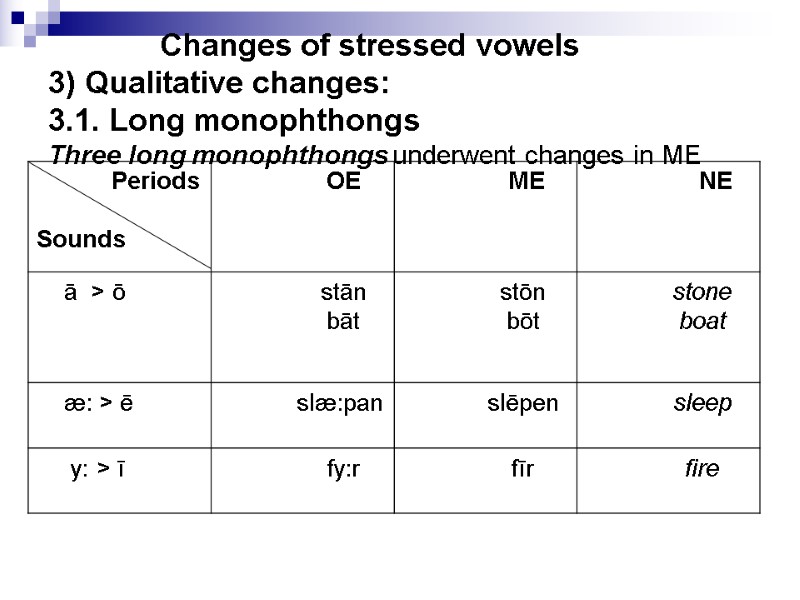

Changes of stressed vowels 3) Qualitative changes: 3.1. Long monophthongs Three long monophthongs underwent changes in ME

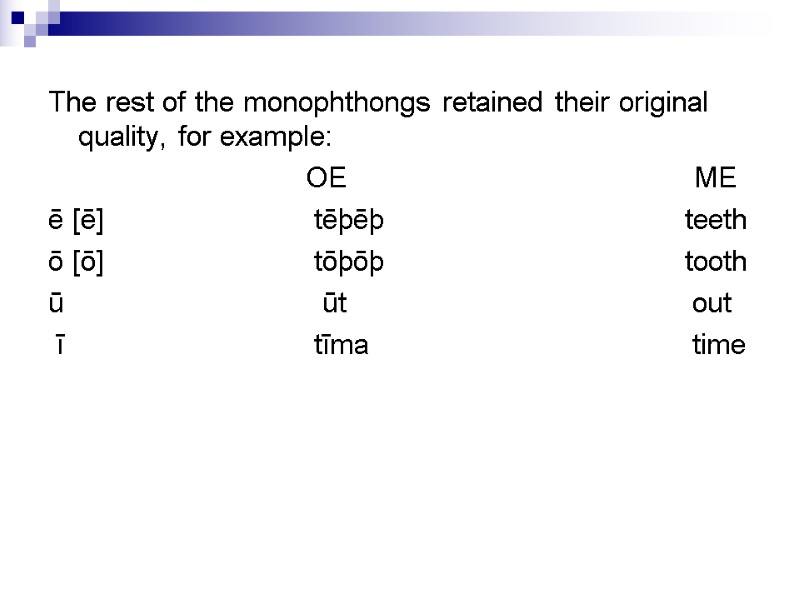

The rest of the monophthongs retained their original quality, for example: OE ME ē [ē] tēþēþ teeth ō [ō] tōþōþ tooth ū ūt out ī tīma time

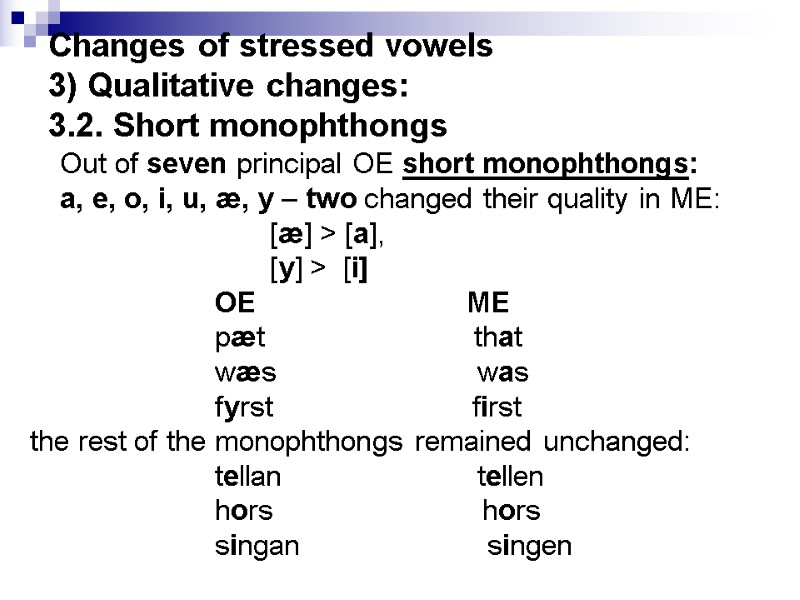

Changes of stressed vowels 3) Qualitative changes: 3.2. Short monophthongs Out of seven principal OE short monophthongs: a, e, o, i, u, æ, y – two changed their quality in ME: [æ] > [a], [y] > [i] OE ME pæt that wæs was fyrst first the rest of the monophthongs remained unchanged: tellan tellen hors hors singan singen

![5) Growth of new diphthongs in ME four new diphthongs: [ai], [ei], [au], [ou]. 5) Growth of new diphthongs in ME four new diphthongs: [ai], [ei], [au], [ou].](https://present5.com/presentacii-2/20171208\9700-me_phonetics_and_nominal_system.ppt\9700-me_phonetics_and_nominal_system_40.jpg)

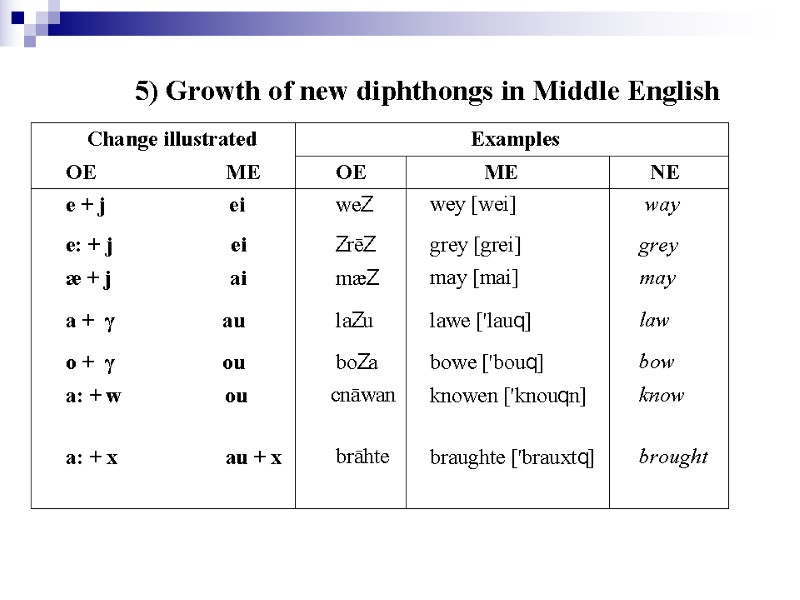

5) Growth of new diphthongs in ME four new diphthongs: [ai], [ei], [au], [ou]. In addition to the diphthongs which developed from native sources, similar diphthongs – with i- and u-glides – are found in some ME loan-words: [Oi] in ME boy, joy, [au] in ME pause, cause ['pauzq, 'kauzq]. The newly formed ME diphthongs differed from the OE in structure: - they had an open nucleus and a closer glide; - they were arranged in a system consisting of two sets (with i-glides and with u-glides) but were not contrasted through quantity as long to short.

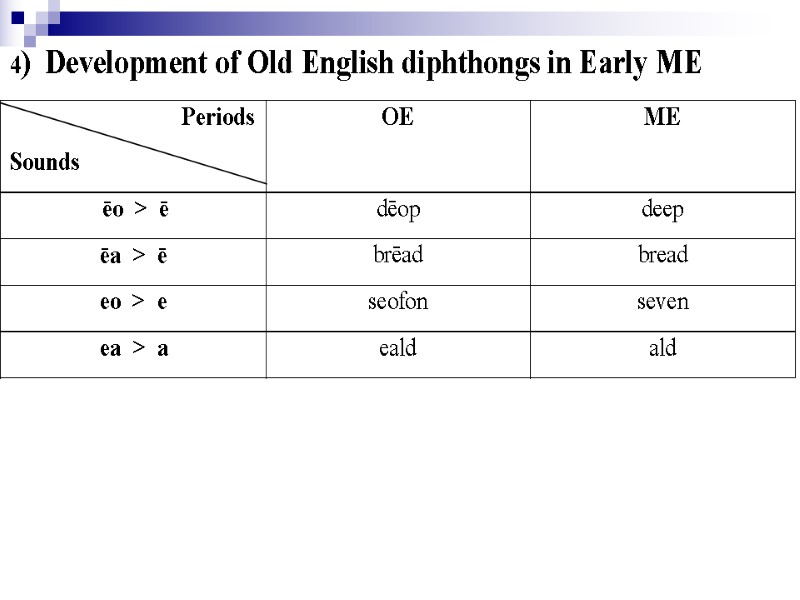

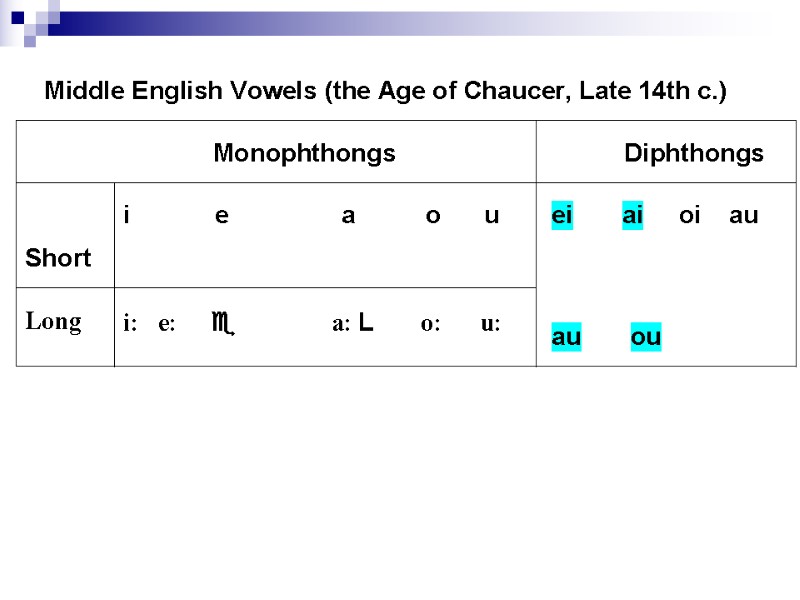

Main characteristics of the vowel system in ME: summary Levelling of vowels in the unstressed position. No principally new monophthongs in the system of the language appeared, but the monophthongs of the [o] and [e] type may differ: they are either “open” – generally those developed from the OE ā (stān > stōn – NE stone) or “close” – developing from the OE ō (bōk > bōk - NE book). 3. The sounds [æ] and [y] disappeared from the system of the language. 4. There are no long diphthongs. 5. New diphthongs appeared with the glide more close than the nucleus (because of the origin) as contrasted to OE with the glide more open than the nucleus.

Main characteristics of the vowel system in ME: summary 6. No parallelism exists between long and short monophthongs different only in their quantity. 7. The quantity of the vowel depends upon its position in the word: - a, o, e – always long in an open syllable or before ld, mb, nd. - all vowels are always short before two consonants with the exception of ld, mb, nd.

![Consonant changes in ME New affricates [t], [d] and the fricative [S] appeared in Consonant changes in ME New affricates [t], [d] and the fricative [S] appeared in](https://present5.com/presentacii-2/20171208\9700-me_phonetics_and_nominal_system.ppt\9700-me_phonetics_and_nominal_system_44.jpg)

Consonant changes in ME New affricates [t], [d] and the fricative [S] appeared in the system of the language from OE palatal consonants or consonant combinations. Old English Middle English [k’] > [t] cild child benc bench cin chin cicen chicken [sk’] > [] scip ship sceal shall [g’] > [d] bryc bridge 2. The resonance (the voiced or the voiceless nature) of the consonants ([f], [v], [s], [z] and [T], [ð]) became phonetic. It does not depend so much on the position of the consonant, and voiced consonants can appear not only in intervocal, but also in initial and other positions.

Middle English Grammar Main Trends of Development The grammatical type of the language has changed: from a synthetic or inflected language into a language of the "analytical type“. The analytical way of form-building was a new device, which developed in Late OE and ME. Analytical forms developed from free word groups (phrases, syntactical constructions): the first component of these phrases gradually weakened or even lost its lexical meaning and turned into a grammatical marker, the second component retained its lexical meaning and acquired a new grammatical value in the compound form. Analytical forms and ways of word connection prevailed over synthetic ones in ME and Early NE. In the synthetic forms of the ME and Early NE periods the means of form-building were the same as before: inflections, sound interchanges, suppletion; Prefixation, namely the prefix Ze-, which was commonly used in OE to mark Participle II, went out of use in Late ME.

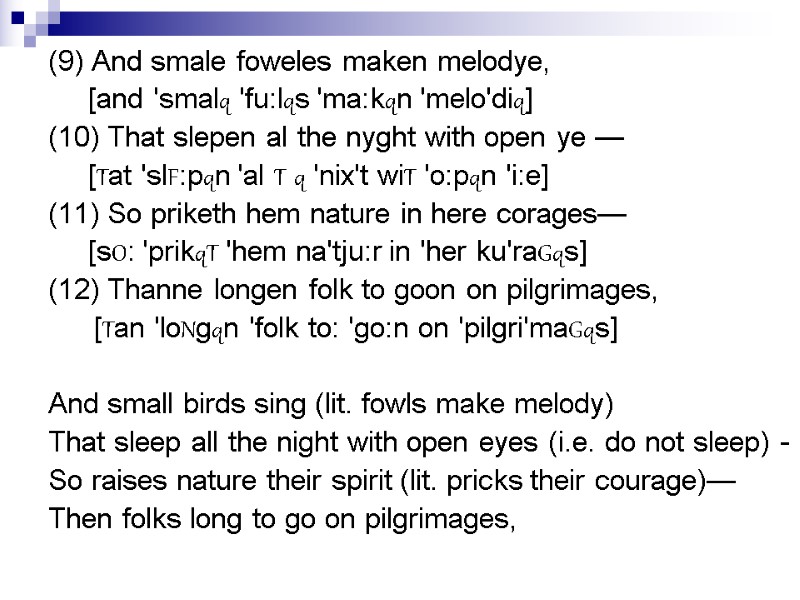

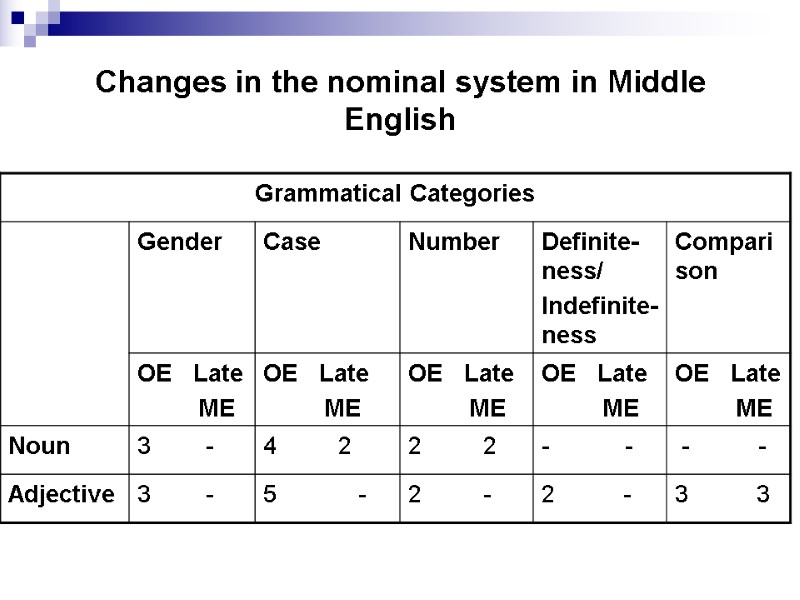

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English morphological simplification. simplifying changes resulted in the decline and transformation of the nominal morphological system. some nominal categories were lost — Gender and Case in adjectives, Gender in nouns; the number of forms in the surviving categories was reduced – cases in nouns and noun-pronouns, numbers in personal pronouns; morphological division into types of declension practically disappeared; In Late ME the adjective lost the distinction of number and the distinction of weak and strong forms.

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Noun Increased variation of the noun forms resulted in re-arrangement and simplification of the declensions. The decline of the OE declension system lasted over three hundred years (10-12c).

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Noun The OE Gender disappeared together with other distinctive features of the noun declensions. In the 11th and 12th c. the gender of nouns was deprived of its main formal support – the weakened and levelled endings of adjectives and adjective pronouns ceased to indicate gender. Semantically gender was associated with the differentiation of sex and therefore the formal grouping into genders was smoothly and naturally superceded by a semantic division into inanimate and animate nouns, with a further subdivision of the latter into males and females.

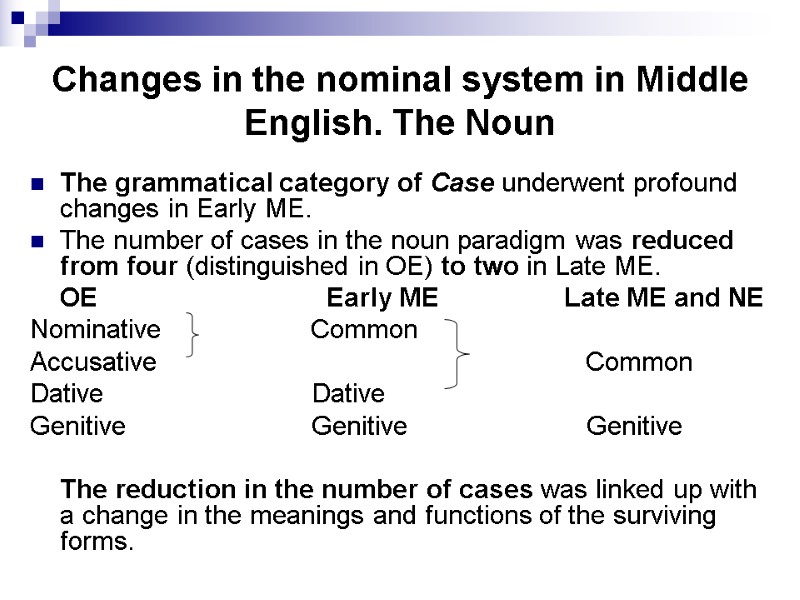

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Noun The grammatical category of Case underwent profound changes in Early ME. The number of cases in the noun paradigm was reduced from four (distinguished in OE) to two in Late ME. OE Early ME Late ME and NE Nominative Common Accusative Common Dative Dative Genitive Genitive Genitive The reduction in the number of cases was linked up with a change in the meanings and functions of the surviving forms.

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Noun the Gen. case was kept separate from the other forms, with more explicit formal distinctions in the singular than in the plural. In the 14th c. the ending -es of the Gen. singular had become almost universal. In the plural the Gen. case had no special marker - it was not distinguished from the Common case. The formal distinction between cases in the plural was lost, except in the nouns which did not take -es in the plural. Several nouns with a weak plural form in -en or with a vowel interchange, such as oxen or men, added the marker of the Gen. case to these forms: oxenes, mennes. In the 17th and l8th c. a new graphic marker of the Gen. case - the apostrophe - came into use: e. g. man's, children's This device could be employed only in writing; in oral speech the forms remained homonymous.

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Noun Number proved to be the most stable of all the nominal categories. The noun preserved the formal distinction of two numbers through all the historical periods. In Late ME the ending -es was the prevalent marker of nouns in the plural. In Early NE it extended: - to the new words of the growing English vocabulary - to many words, which built their plural in a different way in ME or employed -es as one of the variant endings. The plural ending -es underwent several phonetic changes: the voicing of fricatives and the loss of unstressed vowels in final syllables.

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Noun The ME plural ending -en, used as a variant marker with some nouns, lost its former productivity, so that in Standard Mod E it is found only in oxen, brethren, and children. The small group of ME nouns with homonymous forms of number (ME deer, hors, thing) has been further reduced to three "exceptions" in NE: deer, sheep and swine. The group of former root-stems has survived only as exceptions: man, tooth and the like.

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Noun: summary the majority of English nouns have preserved and reinforced the formal distinction of Number in the Comm. Case. English nouns practically lost these distinctions in the Gen. Case, for Gen. has a distinct form in the plural only with nouns whose plural ending is not -es.

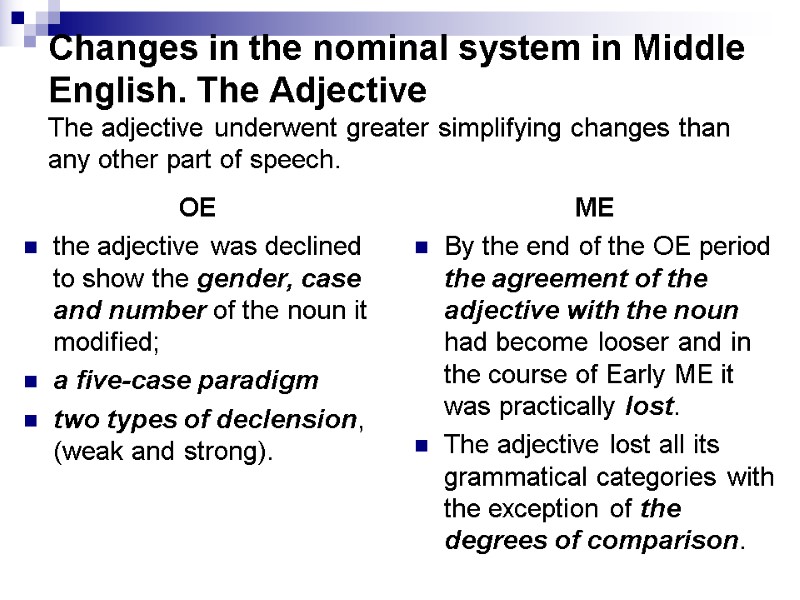

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Adjective The adjective underwent greater simplifying changes than any other part of speech. OE the adjective was declined to show the gender, case and number of the noun it modified; a five-case paradigm two types of declension, (weak and strong). ME By the end of the OE period the agreement of the adjective with the noun had become looser and in the course of Early ME it was practically lost. The adjective lost all its grammatical categories with the exception of the degrees of comparison.

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Adjective The decay of the grammatical categories of the adjective proceeded in the following order: 1) Gender (in the 11 c.) 2) Case (by the end of the 13th c.) 3) The strong and weak forms of adjectives were often confused in Early ME texts. A strong form could be used after a demonstrative pronoun (according to the existing rules, this position belonged to the weak form). In the 14th c. the difference between the strong and weak form is sometimes shown in the sg with the help of the ending -e. The loss of final -e in the transition to NE made the adjective an entirely uninflected part of speech.

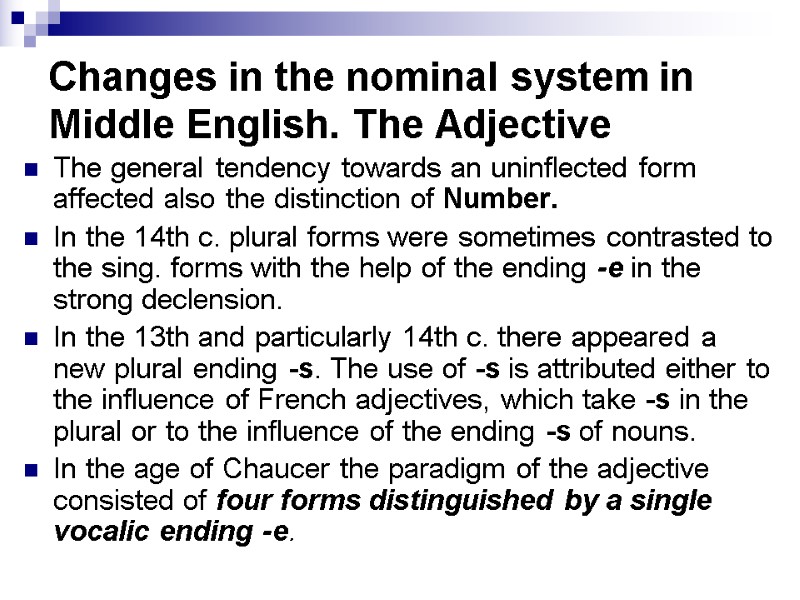

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Adjective The general tendency towards an uninflected form affected also the distinction of Number. In the 14th c. plural forms were sometimes contrasted to the sing. forms with the help of the ending -e in the strong declension. In the 13th and particularly 14th c. there appeared a new plural ending -s. The use of -s is attributed either to the influence of French adjectives, which take -s in the plural or to the influence of the ending -s of nouns. In the age of Chaucer the paradigm of the adjective consisted of four forms distinguished by a single vocalic ending -e.

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Adjective Degrees of Comparison the only set of forms which the adjective has preserved through all historical periods. the means employed to build up the forms of the degrees of comparison have considerably altered. The growth of analytical forms of the degrees of comparison is the most important innovation in the adjective system in the ME period was. the ground for the new system of comparisons had been prepared by the use of the OE adverbs mā, bet, betst, swīþor — 'more', 'better', 'to a greater degree' with adjectives and participles. in ME the phrases with more and most became more common and were used with all kinds of adjectives, regardless of the number of syllables and were even preferred with mono- and disyllabic words.

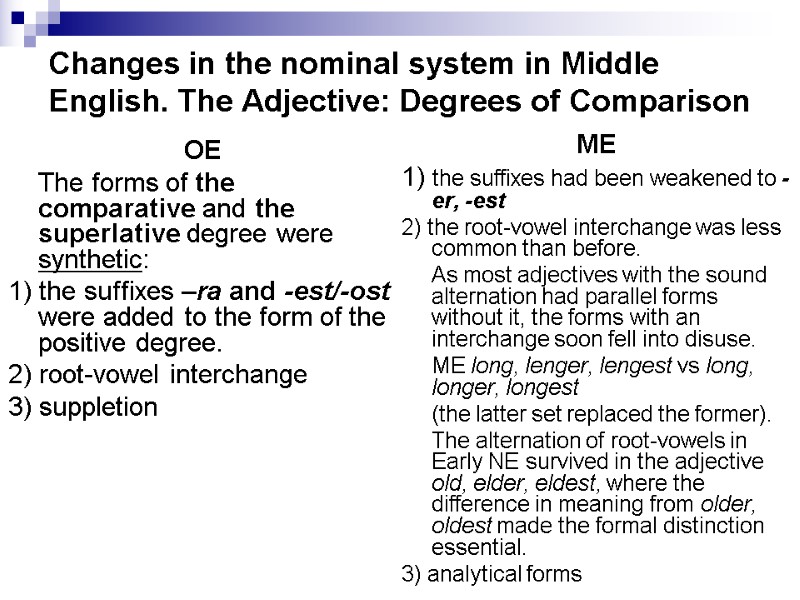

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Adjective: Degrees of Comparison OE The forms of the comparative and the superlative degree were synthetic: 1) the suffixes –ra and -est/-ost were added to the form of the positive degree. 2) root-vowel interchange 3) suppletion ME 1) the suffixes had been weakened to -er, -est 2) the root-vowel interchange was less common than before. As most adjectives with the sound alternation had parallel forms without it, the forms with an interchange soon fell into disuse. ME long, lenger, lengest vs long, longer, longest (the latter set replaced the former). The alternation of root-vowels in Early NE survived in the adjective old, elder, eldest, where the difference in meaning from older, oldest made the formal distinction essential. 3) analytical forms

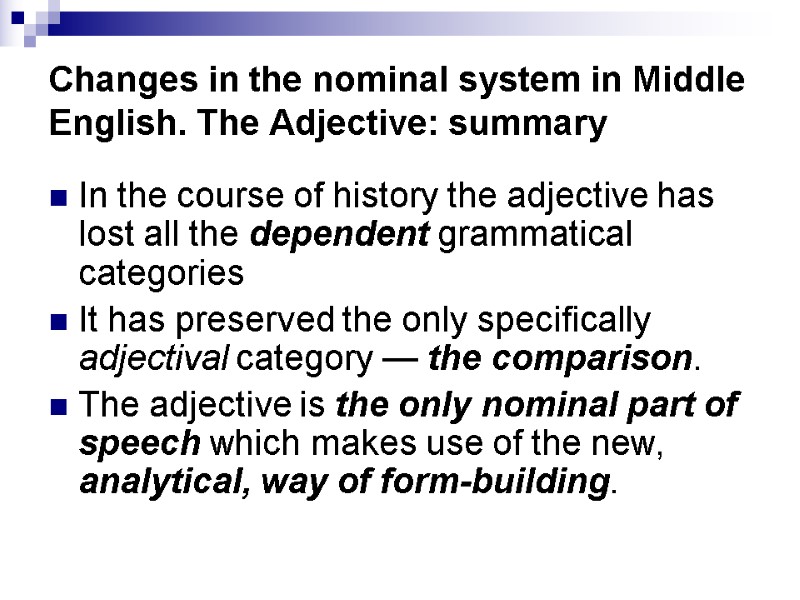

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English. The Adjective: summary In the course of history the adjective has lost all the dependent grammatical categories It has preserved the only specifically adjectival category — the comparison. The adjective is the only nominal part of speech which makes use of the new, analytical, way of form-building.

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English

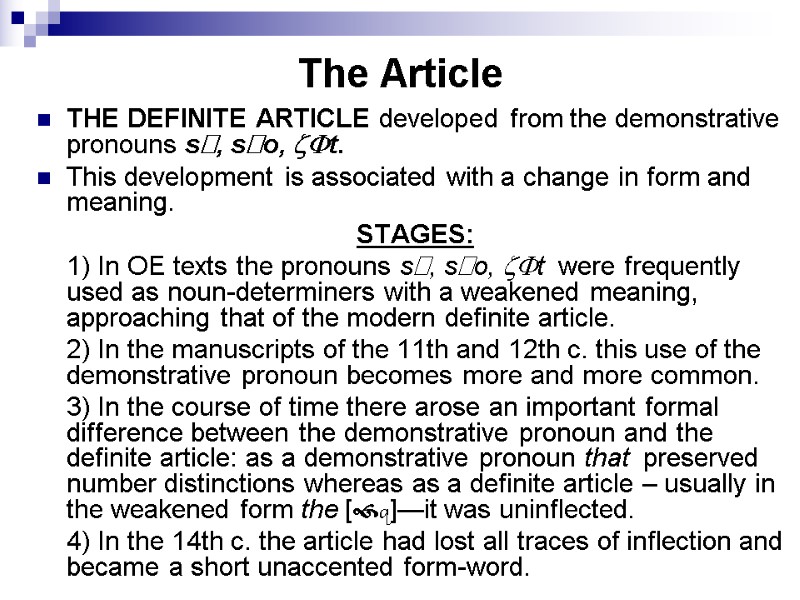

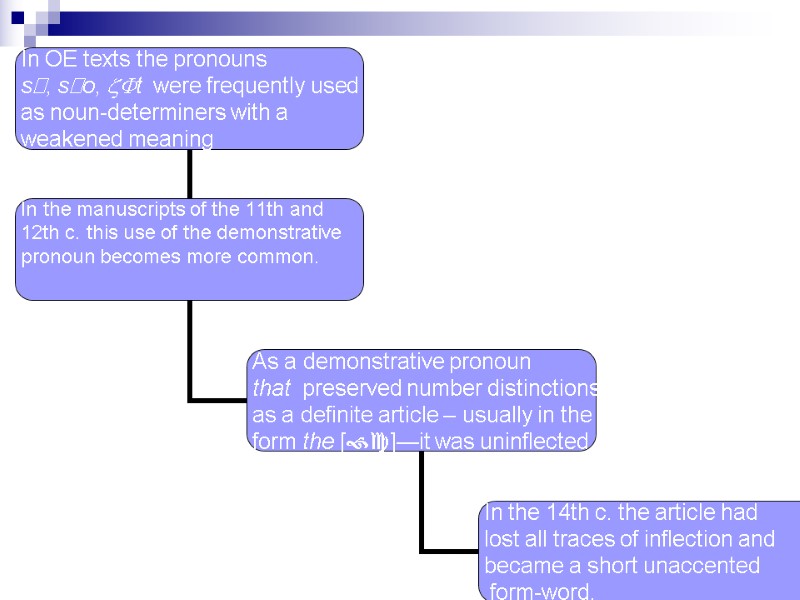

The Article THE DEFINITE ARTICLE developed from the demonstrative pronouns s, so, t. This development is associated with a change in form and meaning. STAGES: 1) In OE texts the pronouns s, so, t were frequently used as noun-determiners with a weakened meaning, approaching that of the modern definite article. 2) In the manuscripts of the 11th and 12th c. this use of the demonstrative pronoun becomes more and more common. 3) In the course of time there arose an important formal difference between the demonstrative pronoun and the definite article: as a demonstrative pronoun that preserved number distinctions whereas as a definite article – usually in the weakened form the [q]—it was uninflected. 4) In the 14th c. the article had lost all traces of inflection and became a short unaccented form-word.

The Indefinite Article The Indefinite Article developed from the OE numeral and indefinite pronoun n. In OE there existed two words, n (a numeral) and sum (an indefinite pronoun) which were often used in functions approaching those of the modern indefinite article. n (a numeral) was a more colloquial word, sum (an indefinite pronoun) tended to assume a literary character and soon fell into disuse in this function. In Early ME the indefinite pronoun n (which had a five-case declension in OE) lost its inflection: - in the 12th c. the inflectional forms of n reveal a state of confusion; - in the 13th c. the uninflected oon/one and their reduced forms an/a are firmly established in all regions. The use of articles in the age of Chaucer is similar to what we find in English today.

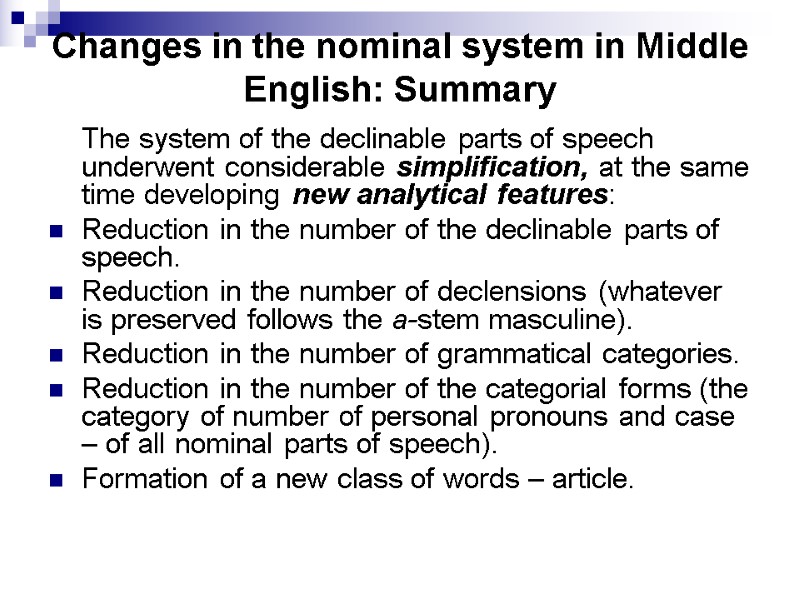

Changes in the nominal system in Middle English: Summary The system of the declinable parts of speech underwent considerable simplification, at the same time developing new analytical features: Reduction in the number of the declinable parts of speech. Reduction in the number of declensions (whatever is preserved follows the a-stem masculine). Reduction in the number of grammatical categories. Reduction in the number of the categorial forms (the category of number of personal pronouns and case – of all nominal parts of speech). Formation of a new class of words – article.

9700-me_phonetics_and_nominal_system.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 65