1a406a830021eb180b3d3e57da28cc58.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 14

Microeconomics Corso E John Hey

Microeconomics Corso E John Hey

What do we know? • The reservation price of a buyer is. . . • . . . the maximum price he or she would pay. • The reservation price of a seller is. . . • . . . the minimum price he or she would accept.

What do we know? • The reservation price of a buyer is. . . • . . . the maximum price he or she would pay. • The reservation price of a seller is. . . • . . . the minimum price he or she would accept.

What do we know? • The surplus of a buyer is. . . • . . . the area between the price paid and the demand curve. • The surplus of a seller is. . . • . . . the area between the price received and the supply curve. • An indifference curve is. . . • . . . a set of points about which the individual is indifferent.

What do we know? • The surplus of a buyer is. . . • . . . the area between the price paid and the demand curve. • The surplus of a seller is. . . • . . . the area between the price received and the supply curve. • An indifference curve is. . . • . . . a set of points about which the individual is indifferent.

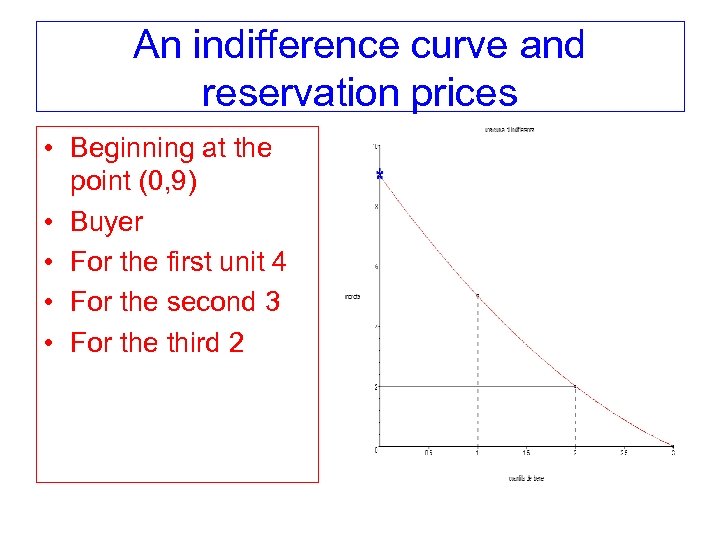

An indifference curve and reservation prices • Beginning at the point (0, 9) • Buyer • For the first unit 4 • For the second 3 • For the third 2

An indifference curve and reservation prices • Beginning at the point (0, 9) • Buyer • For the first unit 4 • For the second 3 • For the third 2

![Reservation prices and the demand curve • [Beginning at the point (0, 9)] • Reservation prices and the demand curve • [Beginning at the point (0, 9)] •](https://present5.com/presentation/1a406a830021eb180b3d3e57da28cc58/image-5.jpg) Reservation prices and the demand curve • [Beginning at the point (0, 9)] • Buyer • For the first unit 4 • For the second 3 • For the third 2

Reservation prices and the demand curve • [Beginning at the point (0, 9)] • Buyer • For the first unit 4 • For the second 3 • For the third 2

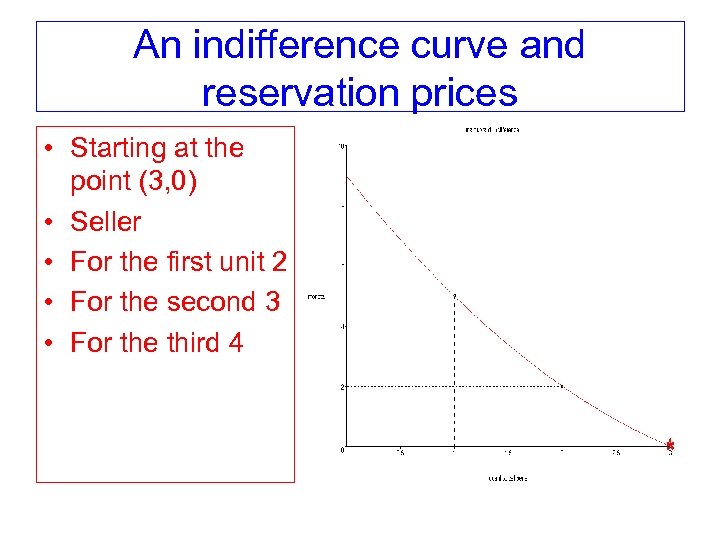

An indifference curve and reservation prices • Starting at the point (3, 0) • Seller • For the first unit 2 • For the second 3 • For the third 4

An indifference curve and reservation prices • Starting at the point (3, 0) • Seller • For the first unit 2 • For the second 3 • For the third 4

![Reservation prices and the supply curve • [Starting at the point (3, 3)] • Reservation prices and the supply curve • [Starting at the point (3, 3)] •](https://present5.com/presentation/1a406a830021eb180b3d3e57da28cc58/image-7.jpg) Reservation prices and the supply curve • [Starting at the point (3, 3)] • Seller • For the first unit 2 • For the second 3 • For the third 4

Reservation prices and the supply curve • [Starting at the point (3, 3)] • Seller • For the first unit 2 • For the second 3 • For the third 4

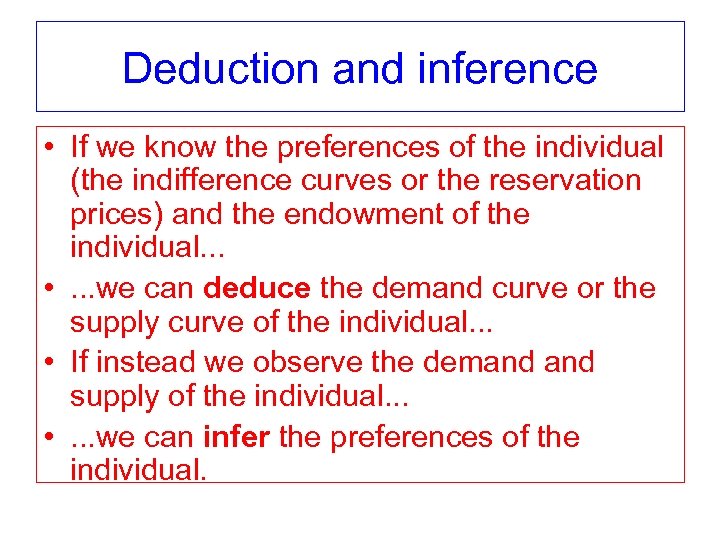

Deduction and inference • If we know the preferences of the individual (the indifference curves or the reservation prices) and the endowment of the individual. . . • . . . we can deduce the demand curve or the supply curve of the individual. . . • If instead we observe the demand supply of the individual. . . • . . . we can infer the preferences of the individual.

Deduction and inference • If we know the preferences of the individual (the indifference curves or the reservation prices) and the endowment of the individual. . . • . . . we can deduce the demand curve or the supply curve of the individual. . . • If instead we observe the demand supply of the individual. . . • . . . we can infer the preferences of the individual.

Deduction and inference The preferences of the individual (the indifference curves or the reservationprices) and the endowment Whether the individual is a buyer or a seller and either the demand or supply curve of the individual.

Deduction and inference The preferences of the individual (the indifference curves or the reservationprices) and the endowment Whether the individual is a buyer or a seller and either the demand or supply curve of the individual.

A Quiz • I do not like Japanese beer. . . • . . . hence I never buy Japanese beer. • Hence my indifference curves (between money and Japanese beer) are. . . ? • . . . • My reservation prices (as a buyer) for Japanese beer are. . ?

A Quiz • I do not like Japanese beer. . . • . . . hence I never buy Japanese beer. • Hence my indifference curves (between money and Japanese beer) are. . . ? • . . . • My reservation prices (as a buyer) for Japanese beer are. . ?

Chapter 4 • In Chapter 3 we have worked with a discrete good – that is, a good that can be traded in integer units. • In Chapter 4 we work with a perfectly divisible good. . which can be traded in any quantities, not only integer units. • We continue to work with a particular kind of preferences – quasi-linear. . . • . . . which imply indifference curves parallel in a vertical direction.

Chapter 4 • In Chapter 3 we have worked with a discrete good – that is, a good that can be traded in integer units. • In Chapter 4 we work with a perfectly divisible good. . which can be traded in any quantities, not only integer units. • We continue to work with a particular kind of preferences – quasi-linear. . . • . . . which imply indifference curves parallel in a vertical direction.

If you like mathematics. . . • m – 60/q = costant is the equation of an indifference curve – the larger the constant, the higher the indifference curve. • pq + m = 3 p + 30 is the equation of the budget line. Here 3 is the endowment of the good and 30 that of money, p is the price of the good, q the quantity consumed and m the amount of money left to spend on other goods. • If we maximise the constant given the budget constraint we obtain the gross demand for the good: • q = √(60/p) • The individual begins with 3 units of the good; hence the net demand is: • q = √(60/p) – 3 • Note: this is positive if p < 60/9 = 6. 66666. . . • is negative if p > 60/9 = 6. 6666. . . • is zero if p = 60/9 = 6. 6666. .

If you like mathematics. . . • m – 60/q = costant is the equation of an indifference curve – the larger the constant, the higher the indifference curve. • pq + m = 3 p + 30 is the equation of the budget line. Here 3 is the endowment of the good and 30 that of money, p is the price of the good, q the quantity consumed and m the amount of money left to spend on other goods. • If we maximise the constant given the budget constraint we obtain the gross demand for the good: • q = √(60/p) • The individual begins with 3 units of the good; hence the net demand is: • q = √(60/p) – 3 • Note: this is positive if p < 60/9 = 6. 66666. . . • is negative if p > 60/9 = 6. 6666. . . • is zero if p = 60/9 = 6. 6666. .

Chapter 4 • Goodbye!

Chapter 4 • Goodbye!