51f9845d6b1738827921ed842d271527.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 36

Methodology 2 • Design research programs • Computational Philosophy of Science – Formation of Concepts and Hypotheses

Methodology 2 • Design research programs • Computational Philosophy of Science – Formation of Concepts and Hypotheses

Design research programs Sect. 10 PM Structure-components in research programs – domain – problem/goal – idea/hard core (incl. vocabulary) – positive heuristic – model as positive heuristics

Design research programs Sect. 10 PM Structure-components in research programs – domain – problem/goal – idea/hard core (incl. vocabulary) – positive heuristic – model as positive heuristics

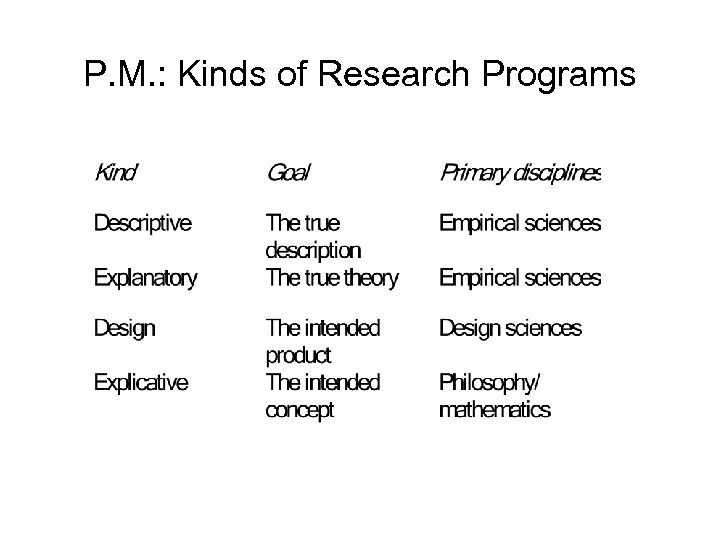

P. M. : Kinds of Research Programs

P. M. : Kinds of Research Programs

Design (research) programs • Examples: new materials, medical drugs, education programs, computer programs • other RP’s as supply-RP’s • CORE IDEA: descriptive meta-RP (Weeder c. s. ): – development of a research-RP: ± systematic attempt to reach agreement between: • properties of available materials • demands derived from intended applications

Design (research) programs • Examples: new materials, medical drugs, education programs, computer programs • other RP’s as supply-RP’s • CORE IDEA: descriptive meta-RP (Weeder c. s. ): – development of a research-RP: ± systematic attempt to reach agreement between: • properties of available materials • demands derived from intended applications

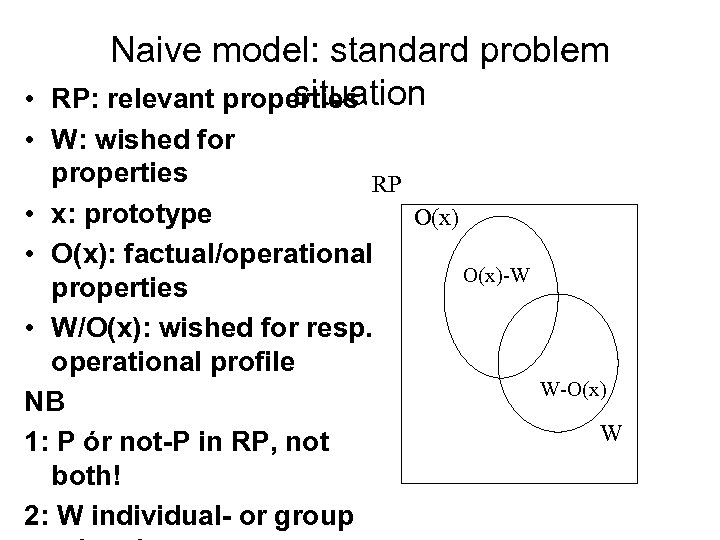

Naive model: standard problem situation RP: relevant properties • • W: wished for properties RP • x: prototype O(x) • O(x): factual/operational O(x)-W properties • W/O(x): wished for resp. operational profile NB 1: P ór not-P in RP, not both! 2: W individual- or group W-O(x) W

Naive model: standard problem situation RP: relevant properties • • W: wished for properties RP • x: prototype O(x) • O(x): factual/operational O(x)-W properties • W/O(x): wished for resp. operational profile NB 1: P ór not-P in RP, not both! 2: W individual- or group W-O(x) W

Standard problems • W-O(x) – not-realized desired properties • O(x)-W – realized undesired properties • to be established by experimentally testing of the claim W=O(x) • forming the options for revision and negotiation

Standard problems • W-O(x) – not-realized desired properties • O(x)-W – realized undesired properties • to be established by experimentally testing of the claim W=O(x) • forming the options for revision and negotiation

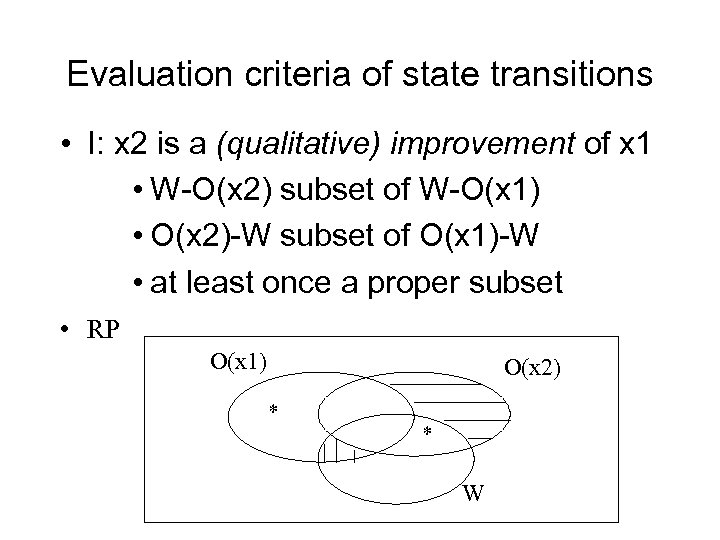

Evaluation criteria of state transitions • I: x 2 is a (qualitative) improvement of x 1 • W-O(x 2) subset of W-O(x 1) • O(x 2)-W subset of O(x 1)-W • at least once a proper subset • RP O(x 1) O(x 2) * * W

Evaluation criteria of state transitions • I: x 2 is a (qualitative) improvement of x 1 • W-O(x 2) subset of W-O(x 1) • O(x 2)-W subset of O(x 1)-W • at least once a proper subset • RP O(x 1) O(x 2) * * W

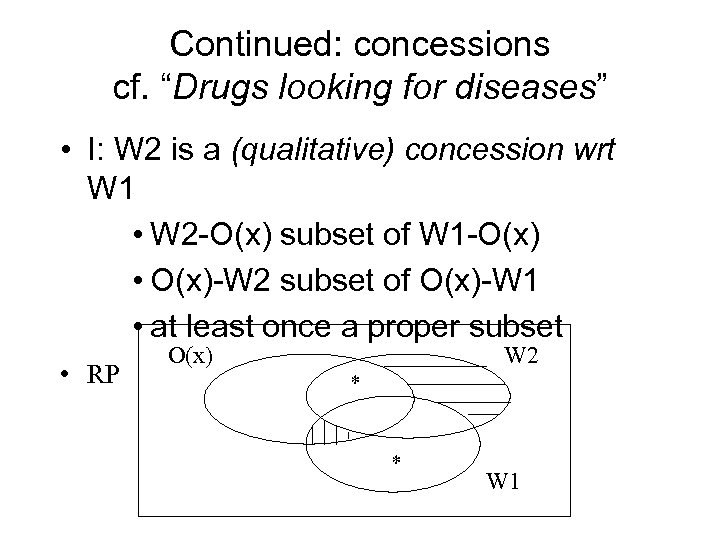

Continued: concessions cf. “Drugs looking for diseases” • I: W 2 is a (qualitative) concession wrt W 1 • W 2 -O(x) subset of W 1 -O(x) • O(x)-W 2 subset of O(x)-W 1 • at least once a proper subset • RP O(x) W 2 * * W 1

Continued: concessions cf. “Drugs looking for diseases” • I: W 2 is a (qualitative) concession wrt W 1 • W 2 -O(x) subset of W 1 -O(x) • O(x)-W 2 subset of O(x)-W 1 • at least once a proper subset • RP O(x) W 2 * * W 1

• Concretizations etc of the naive model Distinction structural/functional properties: to be • • • presented potential applications/ potential realizations extension with possibly relevant properties refinement YES/NO character of properties , , , , with degrees of relevance of properties quantitative versions of the criteria • partial analogy with truth approximation • extrapolation to products on the market

• Concretizations etc of the naive model Distinction structural/functional properties: to be • • • presented potential applications/ potential realizations extension with possibly relevant properties refinement YES/NO character of properties , , , , with degrees of relevance of properties quantitative versions of the criteria • partial analogy with truth approximation • extrapolation to products on the market

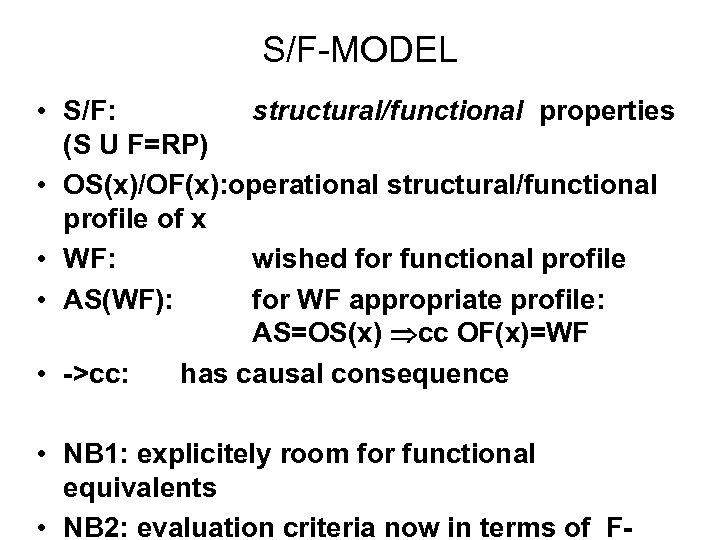

S/F-MODEL • S/F: structural/functional properties (S U F=RP) • OS(x)/OF(x): operational structural/functional profile of x • WF: wished for functional profile • AS(WF): for WF appropriate profile: AS=OS(x) cc OF(x)=WF • ->cc: has causal consequence • NB 1: explicitely room for functional equivalents • NB 2: evaluation criteria now in terms of F-

S/F-MODEL • S/F: structural/functional properties (S U F=RP) • OS(x)/OF(x): operational structural/functional profile of x • WF: wished for functional profile • AS(WF): for WF appropriate profile: AS=OS(x) cc OF(x)=WF • ->cc: has causal consequence • NB 1: explicitely room for functional equivalents • NB 2: evaluation criteria now in terms of F-

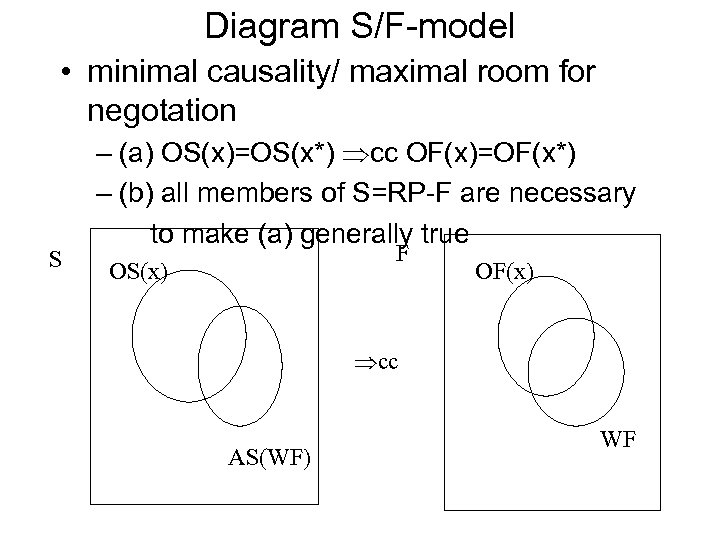

Diagram S/F-model • minimal causality/ maximal room for negotation S – (a) OS(x)=OS(x*) cc OF(x)=OF(x*) – (b) all members of S=RP-F are necessary to make (a) generally true F OS(x) OF(x) cc AS(WF) WF

Diagram S/F-model • minimal causality/ maximal room for negotation S – (a) OS(x)=OS(x*) cc OF(x)=OF(x*) – (b) all members of S=RP-F are necessary to make (a) generally true F OS(x) OF(x) cc AS(WF) WF

HEURISTIC PRINCIPLES (invalid, but useful as default rules) • HP 1: increasing structural similarity (presumably) leads to increasing functional similarity • HP 2: and vice versa, though with more exceptions due to causal asymmetry • NB 1: no HP's for functional concessions • NB 2: Weeber c. s. confused W/O and S/F

HEURISTIC PRINCIPLES (invalid, but useful as default rules) • HP 1: increasing structural similarity (presumably) leads to increasing functional similarity • HP 2: and vice versa, though with more exceptions due to causal asymmetry • NB 1: no HP's for functional concessions • NB 2: Weeber c. s. confused W/O and S/F

Computational Philosophy of Science (CPS) Formation of Concepts and Hypotheses Section 11, Appendices 11 A-D • CPS: co-production Philosophy of Science and Cognitive Science (notably CP&AI) • Intended results: computer programs for – (re-)discovery of concepts and laws – formation, testing and revision of hypotheses – proposing experiments – separate and comparative evaluation of theories • Using heuristics based on cognitive structures

Computational Philosophy of Science (CPS) Formation of Concepts and Hypotheses Section 11, Appendices 11 A-D • CPS: co-production Philosophy of Science and Cognitive Science (notably CP&AI) • Intended results: computer programs for – (re-)discovery of concepts and laws – formation, testing and revision of hypotheses – proposing experiments – separate and comparative evaluation of theories • Using heuristics based on cognitive structures

Points of Departure • Context of Justification (Co. J) and Discovery (Co. D) can both be systematised and programmed • Scientific research is a form of problem solving, with paradigm: heuristic search (Newell/Shaw/Simon) • Possible aims – historical/psychological/philosophical adequacy

Points of Departure • Context of Justification (Co. J) and Discovery (Co. D) can both be systematised and programmed • Scientific research is a form of problem solving, with paradigm: heuristic search (Newell/Shaw/Simon) • Possible aims – historical/psychological/philosophical adequacy

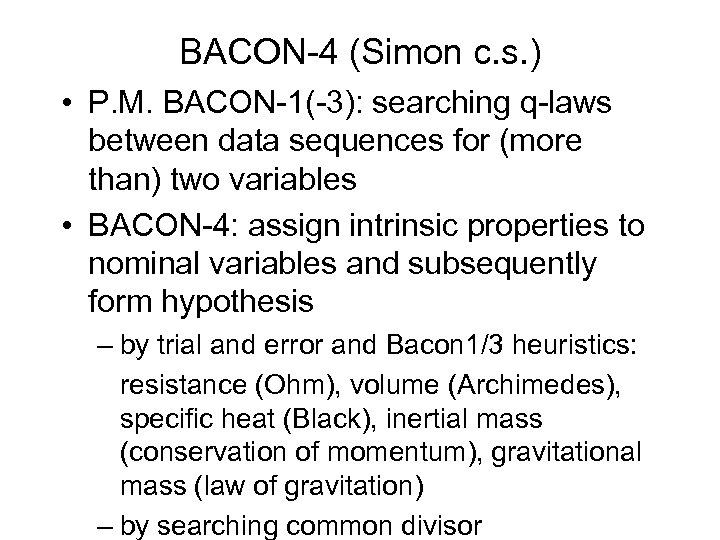

BACON-4 (Simon c. s. ) • P. M. BACON-1(-3): searching q-laws between data sequences for (more than) two variables • BACON-4: assign intrinsic properties to nominal variables and subsequently form hypothesis – by trial and error and Bacon 1/3 heuristics: resistance (Ohm), volume (Archimedes), specific heat (Black), inertial mass (conservation of momentum), gravitational mass (law of gravitation) – by searching common divisor

BACON-4 (Simon c. s. ) • P. M. BACON-1(-3): searching q-laws between data sequences for (more than) two variables • BACON-4: assign intrinsic properties to nominal variables and subsequently form hypothesis – by trial and error and Bacon 1/3 heuristics: resistance (Ohm), volume (Archimedes), specific heat (Black), inertial mass (conservation of momentum), gravitational mass (law of gravitation) – by searching common divisor

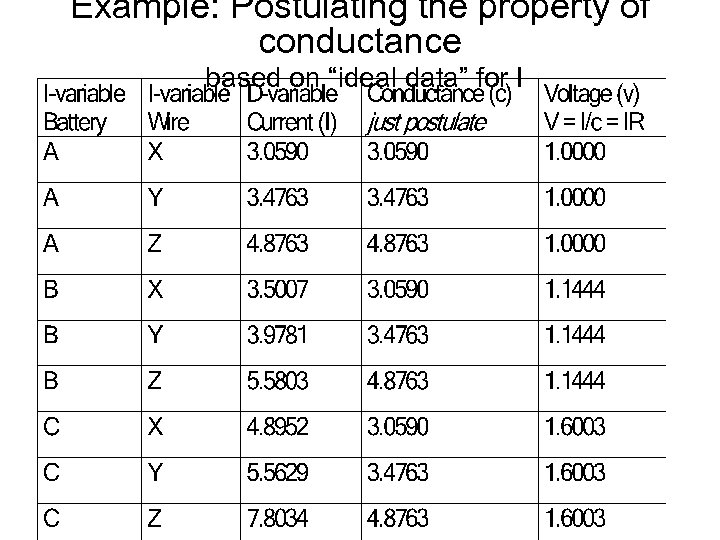

Example: Postulating the property of conductance based on “ideal data” for I

Example: Postulating the property of conductance based on “ideal data” for I

GLAUBER (Simon c. s. ) • Given: properties and reaction equations of some (pure) substances • Goal: classes of substances and reaction equations in terms of these classes • Heuristic Operations: – form the largest possible classes – quantify universally if possible, otherwise existentially

GLAUBER (Simon c. s. ) • Given: properties and reaction equations of some (pure) substances • Goal: classes of substances and reaction equations in terms of these classes • Heuristic Operations: – form the largest possible classes – quantify universally if possible, otherwise existentially

Example • Given: 8 substances – 3 taste similarities: sour, bitter, salt, – 4 reaction equations • Results: – three classes: ACID, ALKALI(BASE), SALT – “ACIDS and ALKALIS form SALTS” • Similar programs, e. g. CLUSTER

Example • Given: 8 substances – 3 taste similarities: sour, bitter, salt, – 4 reaction equations • Results: – three classes: ACID, ALKALI(BASE), SALT – “ACIDS and ALKALIS form SALTS” • Similar programs, e. g. CLUSTER

Processes of Induction (PI, Thagard, c. s. ) • Explanation problem, start with knowledge base (KB) • When matching fails, try Induction and Evaluation: generalisation, abduction, concept&theory formation • Example concept formation: – Why does sound propagate? – Initially activated concept: sound, with spherical propagation – Sec. act. concept: (water-)wave, with propagation in plane

Processes of Induction (PI, Thagard, c. s. ) • Explanation problem, start with knowledge base (KB) • When matching fails, try Induction and Evaluation: generalisation, abduction, concept&theory formation • Example concept formation: – Why does sound propagate? – Initially activated concept: sound, with spherical propagation – Sec. act. concept: (water-)wave, with propagation in plane

General scheme • • General explanation problem C 1: initially activated concept C 2: secondarily activated concept if C 1 - and C 2 -rules are partially incompatible form combination concept C* with all C 1 -rules plus all compatible C 2 -rules form theory: all C 1 are C* evaluate separately and comparatively select the best one

General scheme • • General explanation problem C 1: initially activated concept C 2: secondarily activated concept if C 1 - and C 2 -rules are partially incompatible form combination concept C* with all C 1 -rules plus all compatible C 2 -rules form theory: all C 1 are C* evaluate separately and comparatively select the best one

Other approaches • For pre-1990, see: Shrager and Langley (1990), spec. Ch’s 3, 6 -11 on theory evaluation resp. revision: – ECHO: quasi connectionist evaluation (also Thagard, 1992) – PINEAS: A unified approach to explanation and theory formation – Ab. E (Abduction Engine): Theory formation by abduction – COAST: A computational approach to theory revision – KEKADA: Experimentation in machine discovery – HYPGENE: Hypothesis formation as design

Other approaches • For pre-1990, see: Shrager and Langley (1990), spec. Ch’s 3, 6 -11 on theory evaluation resp. revision: – ECHO: quasi connectionist evaluation (also Thagard, 1992) – PINEAS: A unified approach to explanation and theory formation – Ab. E (Abduction Engine): Theory formation by abduction – COAST: A computational approach to theory revision – KEKADA: Experimentation in machine discovery – HYPGENE: Hypothesis formation as design

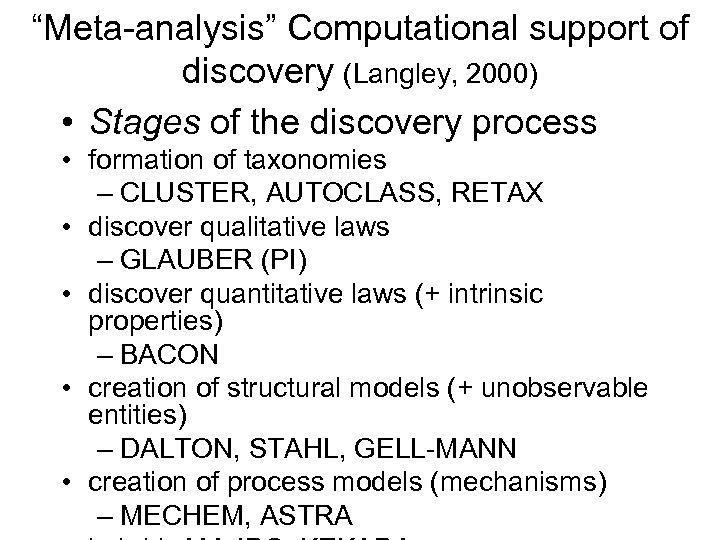

“Meta-analysis” Computational support of discovery (Langley, 2000) • Stages of the discovery process • formation of taxonomies – CLUSTER, AUTOCLASS, RETAX • discover qualitative laws – GLAUBER (PI) • discover quantitative laws (+ intrinsic properties) – BACON • creation of structural models (+ unobservable entities) – DALTON, STAHL, GELL-MANN • creation of process models (mechanisms) – MECHEM, ASTRA

“Meta-analysis” Computational support of discovery (Langley, 2000) • Stages of the discovery process • formation of taxonomies – CLUSTER, AUTOCLASS, RETAX • discover qualitative laws – GLAUBER (PI) • discover quantitative laws (+ intrinsic properties) – BACON • creation of structural models (+ unobservable entities) – DALTON, STAHL, GELL-MANN • creation of process models (mechanisms) – MECHEM, ASTRA

Steps at which the developer or user can influence system behavior • • • problem formulation representation engineering data manipulation algorithm invocation filtering and interpretation

Steps at which the developer or user can influence system behavior • • • problem formulation representation engineering data manipulation algorithm invocation filtering and interpretation

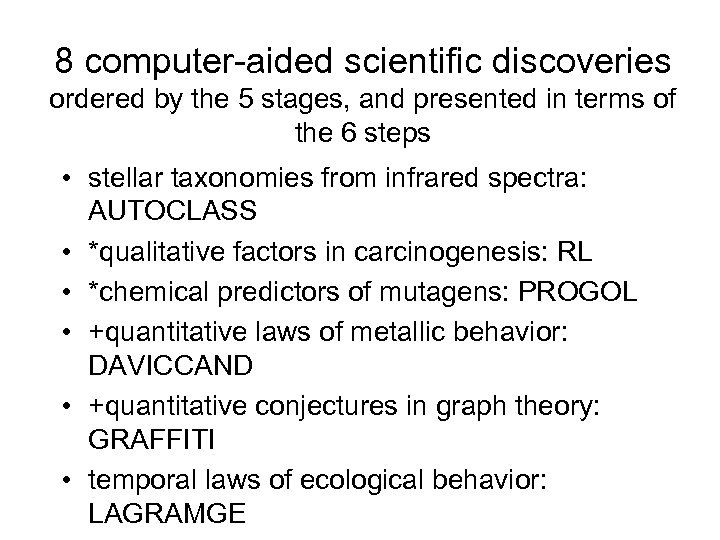

8 computer-aided scientific discoveries ordered by the 5 stages, and presented in terms of the 6 steps • stellar taxonomies from infrared spectra: AUTOCLASS • *qualitative factors in carcinogenesis: RL • *chemical predictors of mutagens: PROGOL • +quantitative laws of metallic behavior: DAVICCAND • +quantitative conjectures in graph theory: GRAFFITI • temporal laws of ecological behavior: LAGRAMGE

8 computer-aided scientific discoveries ordered by the 5 stages, and presented in terms of the 6 steps • stellar taxonomies from infrared spectra: AUTOCLASS • *qualitative factors in carcinogenesis: RL • *chemical predictors of mutagens: PROGOL • +quantitative laws of metallic behavior: DAVICCAND • +quantitative conjectures in graph theory: GRAFFITI • temporal laws of ecological behavior: LAGRAMGE

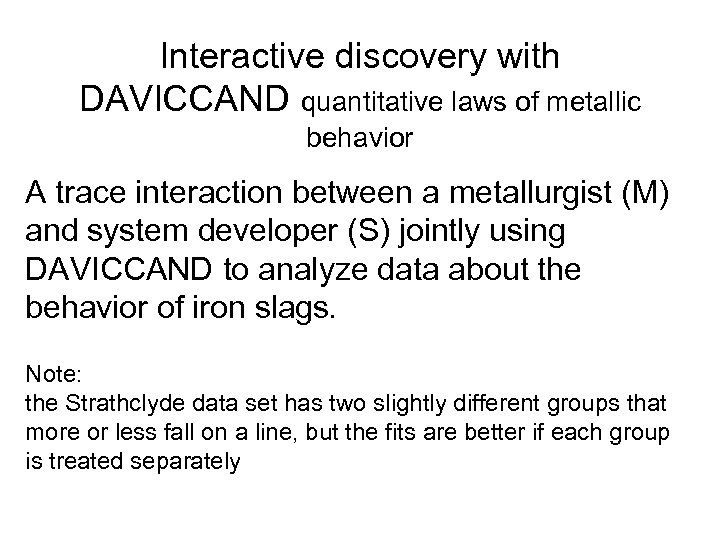

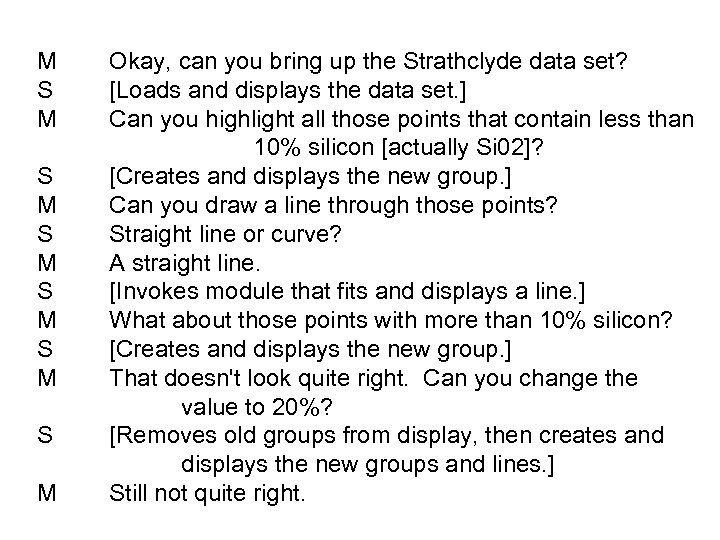

Interactive discovery with DAVICCAND quantitative laws of metallic behavior A trace interaction between a metallurgist (M) and system developer (S) jointly using DAVICCAND to analyze data about the behavior of iron slags. Note: the Strathclyde data set has two slightly different groups that more or less fall on a line, but the fits are better if each group is treated separately

Interactive discovery with DAVICCAND quantitative laws of metallic behavior A trace interaction between a metallurgist (M) and system developer (S) jointly using DAVICCAND to analyze data about the behavior of iron slags. Note: the Strathclyde data set has two slightly different groups that more or less fall on a line, but the fits are better if each group is treated separately

M S M S M S M Okay, can you bring up the Strathclyde data set? [Loads and displays the data set. ] Can you highlight all those points that contain less than 10% silicon [actually Si 02]? [Creates and displays the new group. ] Can you draw a line through those points? Straight line or curve? A straight line. [Invokes module that fits and displays a line. ] What about those points with more than 10% silicon? [Creates and displays the new group. ] That doesn't look quite right. Can you change the value to 20%? [Removes old groups from display, then creates and displays the new groups and lines. ] Still not quite right.

M S M S M S M Okay, can you bring up the Strathclyde data set? [Loads and displays the data set. ] Can you highlight all those points that contain less than 10% silicon [actually Si 02]? [Creates and displays the new group. ] Can you draw a line through those points? Straight line or curve? A straight line. [Invokes module that fits and displays a line. ] What about those points with more than 10% silicon? [Creates and displays the new group. ] That doesn't look quite right. Can you change the value to 20%? [Removes old groups from display, then creates and displays the new groups and lines. ] Still not quite right.

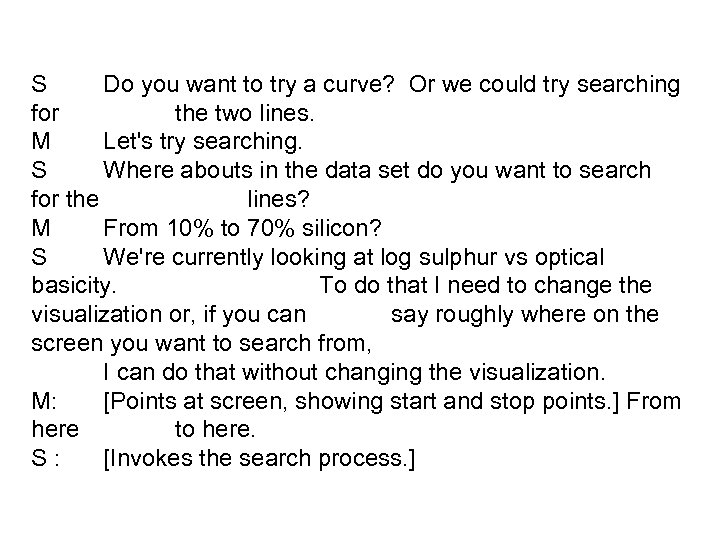

S Do you want to try a curve? Or we could try searching for the two lines. M Let's try searching. S Where abouts in the data set do you want to search for the lines? M From 10% to 70% silicon? S We're currently looking at log sulphur vs optical basicity. To do that I need to change the visualization or, if you can say roughly where on the screen you want to search from, I can do that without changing the visualization. M: [Points at screen, showing start and stop points. ] From here to here. S: [Invokes the search process. ]

S Do you want to try a curve? Or we could try searching for the two lines. M Let's try searching. S Where abouts in the data set do you want to search for the lines? M From 10% to 70% silicon? S We're currently looking at log sulphur vs optical basicity. To do that I need to change the visualization or, if you can say roughly where on the screen you want to search from, I can do that without changing the visualization. M: [Points at screen, showing start and stop points. ] From here to here. S: [Invokes the search process. ]

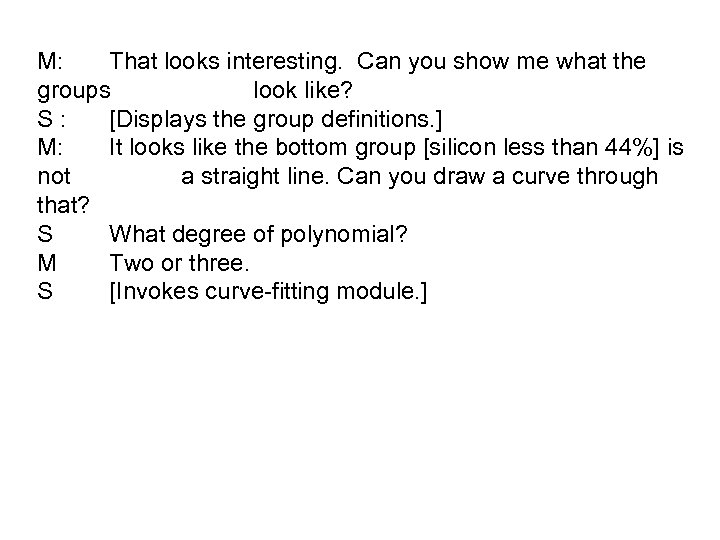

M: That looks interesting. Can you show me what the groups look like? S: [Displays the group definitions. ] M: It looks like the bottom group [silicon less than 44%] is not a straight line. Can you draw a curve through that? S What degree of polynomial? M Two or three. S [Invokes curve-fitting module. ]

M: That looks interesting. Can you show me what the groups look like? S: [Displays the group definitions. ] M: It looks like the bottom group [silicon less than 44%] is not a straight line. Can you draw a curve through that? S What degree of polynomial? M Two or three. S [Invokes curve-fitting module. ]

Progress and prospects • so far: mainly historical cases, but some novel discoveries • great potential for aiding the scientific process • requires substantial interaction of developer and researcher • researchers show not much enthusiasm for collaboration • “If we want to encourage synergy between human and artificial scientists, then we must modify our discovery systems to support their interaction more directly” • “We predict that, as more developers realize the need to provide explicit support for human intervention, we will see even more productive systems and even

Progress and prospects • so far: mainly historical cases, but some novel discoveries • great potential for aiding the scientific process • requires substantial interaction of developer and researcher • researchers show not much enthusiasm for collaboration • “If we want to encourage synergy between human and artificial scientists, then we must modify our discovery systems to support their interaction more directly” • “We predict that, as more developers realize the need to provide explicit support for human intervention, we will see even more productive systems and even

Knowledge Discovery in Science (Raúl Valdés-Pérez, 1999) • Basic concepts: – Heuristic search in combinatorial spaces – Data-driven and knowledge driven approaches – Enhancing human discovery – The goals of scientific discovery • Three examples of successful Discovery Programs: – ARROSMITH (med), GRAFFITI (math), MECHEM (chem) • Guiding questions for automating discovery • Patterns of successful user/computer collaboration:

Knowledge Discovery in Science (Raúl Valdés-Pérez, 1999) • Basic concepts: – Heuristic search in combinatorial spaces – Data-driven and knowledge driven approaches – Enhancing human discovery – The goals of scientific discovery • Three examples of successful Discovery Programs: – ARROSMITH (med), GRAFFITI (math), MECHEM (chem) • Guiding questions for automating discovery • Patterns of successful user/computer collaboration:

Patterns of successful user/computer collaboration • Search a combinatorial space comprehensively • report the simplest solutions first • design a search space with highly understandable elements • if knowledge-driven: – let relevant knowledge be inputted interactively – solutions should respect that knowledge • if data-driven: – use abundant data if possible – use permutation tests if the data are scarce • Finally: cultivate interdisciplinary collaboration

Patterns of successful user/computer collaboration • Search a combinatorial space comprehensively • report the simplest solutions first • design a search space with highly understandable elements • if knowledge-driven: – let relevant knowledge be inputted interactively – solutions should respect that knowledge • if data-driven: – use abundant data if possible – use permutation tests if the data are scarce • Finally: cultivate interdisciplinary collaboration

Challenge 1: Law laden concept formation? Example (Kuipers, 2001, Ch. 2): Empirical absolute temperature T and the ideal gas constant R can be explicitly defined on the basis of 3 empirical (asymptotic) gas laws dealing with V(olume), P(ressure) and ‘thermal states’, based on the eq. rel. of thermal equilibrium. The laws provide the necessary existence and uniqueness conditions. After the definition: the 3 laws can be summarised in the standard form: PV=RT BACON-4/5/BLACK seem not yet able to do this NB: B-5 /BLACK operate theory (symmetry, conservation) driven

Challenge 1: Law laden concept formation? Example (Kuipers, 2001, Ch. 2): Empirical absolute temperature T and the ideal gas constant R can be explicitly defined on the basis of 3 empirical (asymptotic) gas laws dealing with V(olume), P(ressure) and ‘thermal states’, based on the eq. rel. of thermal equilibrium. The laws provide the necessary existence and uniqueness conditions. After the definition: the 3 laws can be summarised in the standard form: PV=RT BACON-4/5/BLACK seem not yet able to do this NB: B-5 /BLACK operate theory (symmetry, conservation) driven

Challenge 2: Belief revision aiming at truth approximation • Belief revision = theory revision in the face of evidence = generation and evaluation of a revised theory = abduction of a revision • Peirce, Thagard, Aliseda, etc. • General characterization: • in search of an acceptable explanatory hypothesis for a surprising or anomalous (individual or general) observational fact

Challenge 2: Belief revision aiming at truth approximation • Belief revision = theory revision in the face of evidence = generation and evaluation of a revised theory = abduction of a revision • Peirce, Thagard, Aliseda, etc. • General characterization: • in search of an acceptable explanatory hypothesis for a surprising or anomalous (individual or general) observational fact

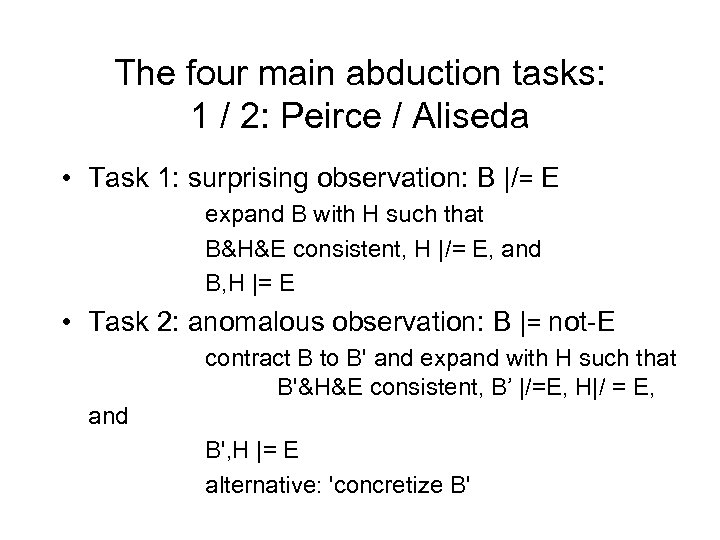

The four main abduction tasks: 1 / 2: Peirce / Aliseda • Task 1: surprising observation: B |/= E expand B with H such that B&H&E consistent, H |/= E, and B, H |= E • Task 2: anomalous observation: B |= not-E contract B to B' and expand with H such that B'&H&E consistent, B’ |/=E, H|/ = E, and B', H |= E alternative: 'concretize B'

The four main abduction tasks: 1 / 2: Peirce / Aliseda • Task 1: surprising observation: B |/= E expand B with H such that B&H&E consistent, H |/= E, and B, H |= E • Task 2: anomalous observation: B |= not-E contract B to B' and expand with H such that B'&H&E consistent, B’ |/=E, H|/ = E, and B', H |= E alternative: 'concretize B'

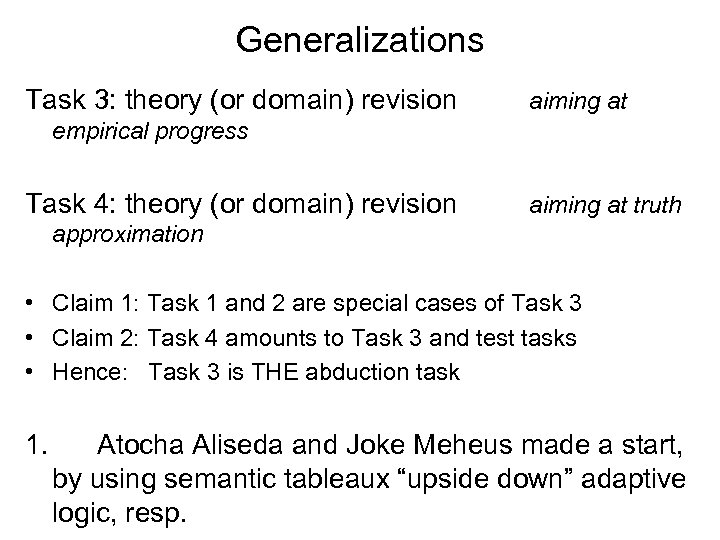

Generalizations Task 3: theory (or domain) revision aiming at empirical progress Task 4: theory (or domain) revision aiming at truth approximation • Claim 1: Task 1 and 2 are special cases of Task 3 • Claim 2: Task 4 amounts to Task 3 and test tasks • Hence: Task 3 is THE abduction task 1. Atocha Aliseda and Joke Meheus made a start, by using semantic tableaux “upside down” adaptive logic, resp.

Generalizations Task 3: theory (or domain) revision aiming at empirical progress Task 4: theory (or domain) revision aiming at truth approximation • Claim 1: Task 1 and 2 are special cases of Task 3 • Claim 2: Task 4 amounts to Task 3 and test tasks • Hence: Task 3 is THE abduction task 1. Atocha Aliseda and Joke Meheus made a start, by using semantic tableaux “upside down” adaptive logic, resp.

References Darden, L. (1997): "Recent work in computational scientific discovery", in: Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, eds. M. Shafto and P. Langley, Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, pp. 161 -166. Web: www. cs. umd. edu/~zben/demo/dist/papers/darden 97. r. html Kuipers, T. (1999), “Abduction Aiming at Empirical Progress or Even at Truth Approximation”, Foundations of Science, 4, 30723. Kuipers, T. (2001): “Computational Philosophy of Science”, Ch. 11, Structures in Science, Synthese Libarary 301, Kluwer AP Langley, P. (2000): “The computational support of scientific discovery”, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 53, 393410. Web: www. isle. org/~langley/pubs. html. Langley, P. , H. Simon, C. Bradshaw, J. Zytkow (1987): Scientific Discovery, Computational Explorations of the Creative Processes, MIT, Cambridge, Mass. Shrager, J. and P. Langley (1990): Computational models of scientific discovery and theory formation, Kaufmann, San Mateo Thagard, P. Computational Philosophy of Science, MIT-Press, Cambridge, 1988/1993

References Darden, L. (1997): "Recent work in computational scientific discovery", in: Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, eds. M. Shafto and P. Langley, Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, pp. 161 -166. Web: www. cs. umd. edu/~zben/demo/dist/papers/darden 97. r. html Kuipers, T. (1999), “Abduction Aiming at Empirical Progress or Even at Truth Approximation”, Foundations of Science, 4, 30723. Kuipers, T. (2001): “Computational Philosophy of Science”, Ch. 11, Structures in Science, Synthese Libarary 301, Kluwer AP Langley, P. (2000): “The computational support of scientific discovery”, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 53, 393410. Web: www. isle. org/~langley/pubs. html. Langley, P. , H. Simon, C. Bradshaw, J. Zytkow (1987): Scientific Discovery, Computational Explorations of the Creative Processes, MIT, Cambridge, Mass. Shrager, J. and P. Langley (1990): Computational models of scientific discovery and theory formation, Kaufmann, San Mateo Thagard, P. Computational Philosophy of Science, MIT-Press, Cambridge, 1988/1993