2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 42

Medical Robotics: An Overview Jennifer Brooks for Comp 790 -072, Robotics: An Introduction at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill November 9, 2006

3 Categories l l l Biorobotics Rehabilitation Robotics for Surgery – – Autonomous Robots Computer Assisted Surgery

Biorobotics l Modeling and simulating biological systems in order to provide a better understanding of human physiology – l For example, haptics research to provide force-feedback in master-slave systems May also lead to a number of practical applications for the substitution of organs and/or functions of humans – Examples: l l l l bionic limb prosthesis hearing aids and other aids targeted at neuromotor recovery the possibility of inserting brain chips implanting microscopic activators in the heart to pump blood data and image acquisition microsystems for artificial sight microchips to detect sound and to substitute the auditory nerve May be used to aid in investigation of diseases or other health-related ailments – Examples l l inch-worm robot developed in Singapore for colon exploration intestinal bug developed in the Nanorobotics lab at CMU

![Example Biorobotic System: DDX [Rovetta, 2001] l DDX is an experimental biorobotic system designed Example Biorobotic System: DDX [Rovetta, 2001] l DDX is an experimental biorobotic system designed](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-4.jpg)

Example Biorobotic System: DDX [Rovetta, 2001] l DDX is an experimental biorobotic system designed to acquire and provide data about human finger movement, applied in analysis of neural disturbances with quantitative evaluation of both response times and dynamic action of the patient. l The goal is to measure the response parameters of a person in front of a “soft touch”, made by his finger in front of a button. l It is now applied in daily clinical activity to diagnose the progression of the Parkinson pathology.

![Disease Detector 3 (DD 3) [Rovetta, 2001] l A fuzzy-based control system for detection Disease Detector 3 (DD 3) [Rovetta, 2001] l A fuzzy-based control system for detection](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-5.jpg)

Disease Detector 3 (DD 3) [Rovetta, 2001] l A fuzzy-based control system for detection of Parkinson disease l May be used remotely to monitor a patient’s health at his or her home l Patient pushes button on a joystick; system measures response time, speed, fingertip pressure, and tremor l Virtual Movement: on a display, the patient is asked to follow a virtual image relating to each moment of the test. Again, system measures response time, speed, fingertip pressure, and tremor from the press of a button and grip on a joystick.

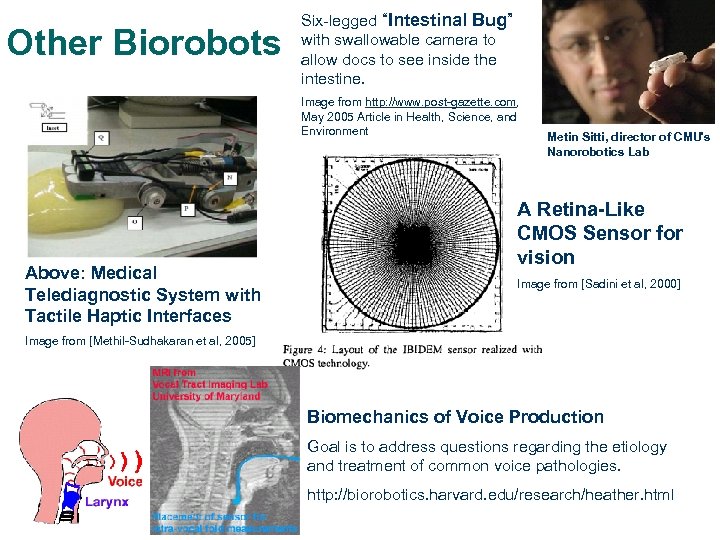

Other Biorobots Six-legged “Intestinal Bug” with swallowable camera to allow docs to see inside the intestine. Image from http: //www. post-gazette. com, May 2005 Article in Health, Science, and Environment Above: Medical Telediagnostic System with Tactile Haptic Interfaces Metin Sitti, director of CMU's Nanorobotics Lab A Retina-Like CMOS Sensor for vision Image from [Sadini et al, 2000] Image from [Methil-Sudhakaran et al, 2005] Biomechanics of Voice Production Goal is to address questions regarding the etiology and treatment of common voice pathologies. http: //biorobotics. harvard. edu/research/heather. html

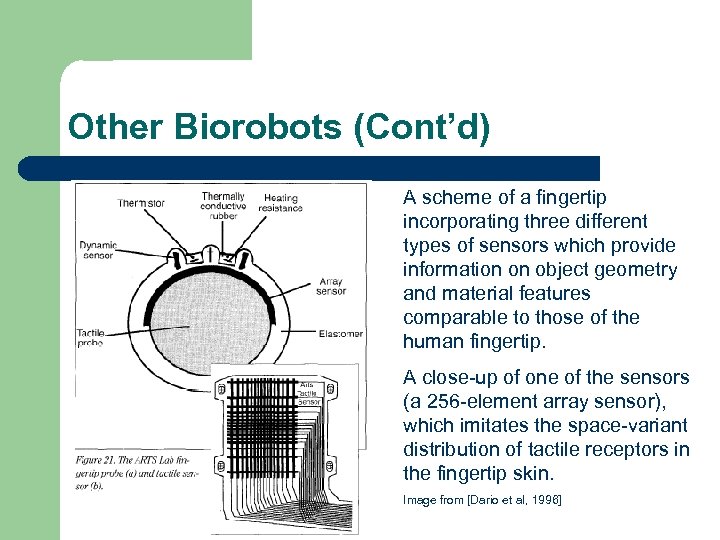

Other Biorobots (Cont’d) A scheme of a fingertip incorporating three different types of sensors which provide information on object geometry and material features comparable to those of the human fingertip. A close-up of one of the sensors (a 256 -element array sensor), which imitates the space-variant distribution of tactile receptors in the fingertip skin. Image from [Dario et al, 1996]

Rehabilitation Robotics l Robotics systems for hospitals – – l Manipulators in rehabilitation – – – l l MOVAID: a mobile base which fits into different activity workstations, built on URMAD technology Advanced prosthesis and orthosis Functional Electric Simulation (FES) – l self-navigating wheelchairs with sensors enabling them to avoid obstacles Daily life home assistance – l Wheelchair-mounted arms Mo. VAR: the Mobile Vocational Assistant URMAD: a mobile base that responds to a fixed workstation, mainly devised for residential applications “Intelligent” wheelchairs – l Help. Mates MELKONG Computer-Aided Locomotion by Implanted Electro-Stimulation (CALIES) Virtual environments for training and rehabilitative therapies

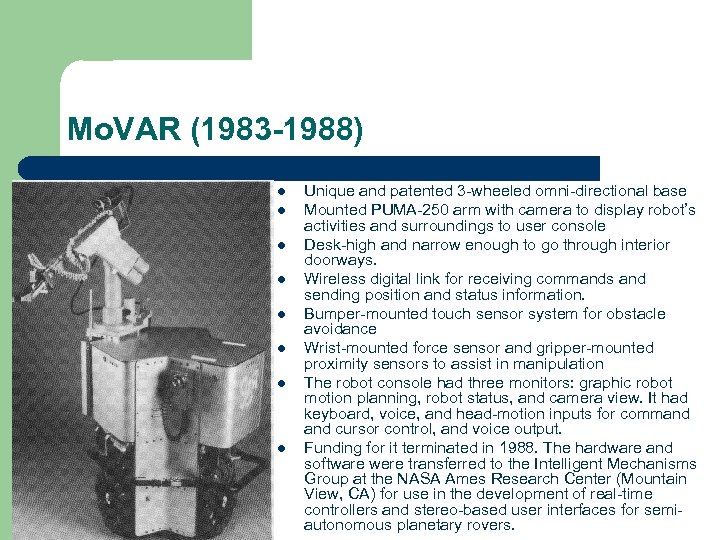

Mo. VAR (1983 -1988) l l l l Unique and patented 3 -wheeled omni-directional base Mounted PUMA-250 arm with camera to display robot’s activities and surroundings to user console Desk-high and narrow enough to go through interior doorways. Wireless digital link for receiving commands and sending position and status information. Bumper-mounted touch sensor system for obstacle avoidance Wrist-mounted force sensor and gripper-mounted proximity sensors to assist in manipulation The robot console had three monitors: graphic robot motion planning, robot status, and camera view. It had keyboard, voice, and head-motion inputs for command cursor control, and voice output. Funding for it terminated in 1988. The hardware and software were transferred to the Intelligent Mechanisms Group at the NASA Ames Research Center (Mountain View, CA) for use in the development of real-time controllers and stereo-based user interfaces for semiautonomous planetary rovers.

![URMAD Image from [Dario, 1996] URMAD Image from [Dario, 1996]](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-10.jpg)

URMAD Image from [Dario, 1996]

Computer-Aided Locomotion by Implanted Electro-Stimulation (CALIES) l l Probably the most important coordinated effort in the world for restoring autonomous locomotion in paralyzed persons [Dario, 1996] Investigated the possibility of implanting electrodes into lower limb muscles, or nerves, which could be stimulated via an external computer to produce close to natural walking

Robotics for Surgery

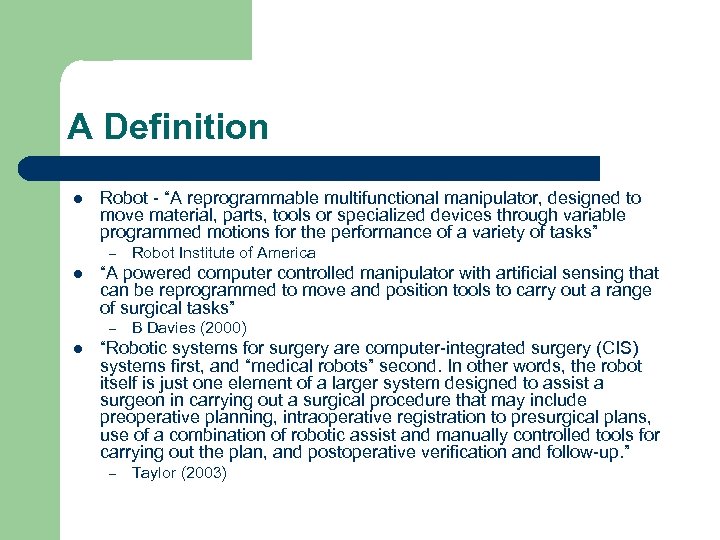

A Definition l Robot - “A reprogrammable multifunctional manipulator, designed to move material, parts, tools or specialized devices through variable programmed motions for the performance of a variety of tasks” – l “A powered computer controlled manipulator with artificial sensing that can be reprogrammed to move and position tools to carry out a range of surgical tasks” – l Robot Institute of America B Davies (2000) “Robotic systems for surgery are computer-integrated surgery (CIS) systems first, and “medical robots” second. In other words, the robot itself is just one element of a larger system designed to assist a surgeon in carrying out a surgical procedure that may include preoperative planning, intraoperative registration to presurgical plans, use of a combination of robotic assist and manually controlled tools for carrying out the plan, and postoperative verification and follow-up. ” – Taylor (2003)

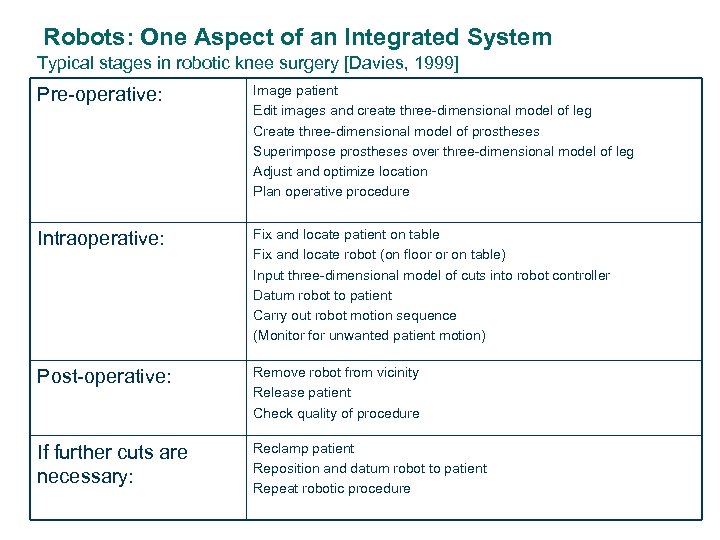

Robots: One Aspect of an Integrated System Typical stages in robotic knee surgery [Davies, 1999] Pre-operative: Image patient Edit images and create three-dimensional model of leg Create three-dimensional model of prostheses Superimpose prostheses over three-dimensional model of leg Adjust and optimize location Plan operative procedure Intraoperative: Fix and locate patient on table Fix and locate robot (on floor or on table) Input three-dimensional model of cuts into robot controller Datum robot to patient Carry out robot motion sequence (Monitor for unwanted patient motion) Post-operative: Remove robot from vicinity Release patient Check quality of procedure If further cuts are necessary: Reclamp patient Reposition and datum robot to patient Repeat robotic procedure

![Benefits from [Davies, 1999]: l The ability to move in a predefined and reprogrammable Benefits from [Davies, 1999]: l The ability to move in a predefined and reprogrammable](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-15.jpg)

Benefits from [Davies, 1999]: l The ability to move in a predefined and reprogrammable complex threedimensional path, both accurately and predictably. l The ability to actively constrain tools to a particular path or location, even against externally imposed forces, thus preventing damage to vital regions. This can lead to safer procedures than those achieved using Computer Assisted Surgery (CAS). l The ability to make repetitive motions, for long periods, tirelessly. l The ability to move to a location and then hold tools there for long periods accurately, rigidly and without tremor. l The ability to perform in environments unsafe for humans, such as radioactive and fluoroscopic. l Precise micromotions with prespecified microforces. l Quick and automatic response to sensor signals or to changes in commands. l To be able to perform ‘keyhole’ minimal access surgery, without the aid of vision and without ‘forgetting’ the path or the location.

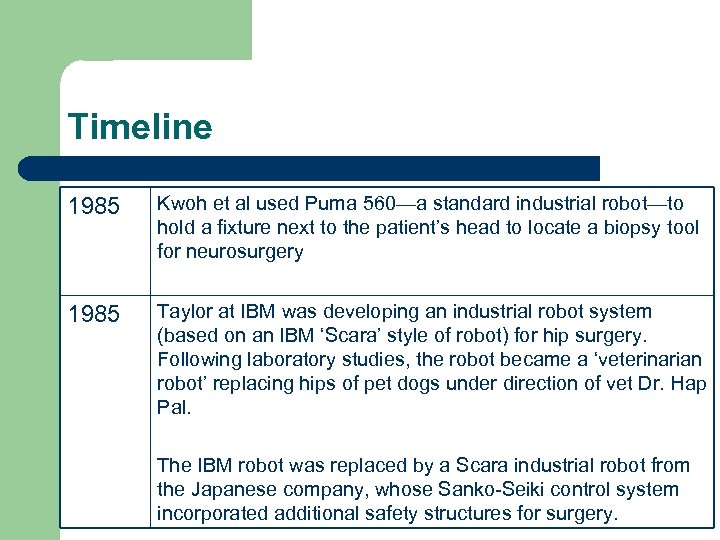

Timeline 1985 Kwoh et al used Puma 560—a standard industrial robot—to hold a fixture next to the patient’s head to locate a biopsy tool for neurosurgery 1985 Taylor at IBM was developing an industrial robot system (based on an IBM ‘Scara’ style of robot) for hip surgery. Following laboratory studies, the robot became a ‘veterinarian robot’ replacing hips of pet dogs under direction of vet Dr. Hap Pal. The IBM robot was replaced by a Scara industrial robot from the Japanese company, whose Sanko-Seiki control system incorporated additional safety structures for surgery.

Timeline (cont’d) 1988 First attempt at active motion robot in surgery. The Mechatronics in Medicine Group at Imperial College built onto Puma 560 to perform soft-tissue surgery in transurethral resection of prostate (TURP). April 1991 First time an active robot was used to automatically remove tissue from patients. This resulted from developments based on the PUMA studies for TURP. Since that time a 2 ndgeneration prostate robot (called Probot) has been developed at Imperial College. Late 1991 The modified Sanko Seiki robot system, now called ‘Robodoc’ was tried clinically on human patients.

Timeline (cont’d) Dec 1993 The AESOP 1000, used for holding an endoscopic camera in minimal invasive laparoscopic surgery, developed by Computer Motion was approved by the FDA. 1997 The da Vinci Surgical System manufactured by Intuitive Surgical Inc. , became the first assisting surgical robot to receive FDA approval to help surgeons more easily perform laparoscopic surgery. Jacques Himpens and Guy Cardier in Brussels, Belgium used the da Vinci by Intuitive Surgical Inc. system to perform the first telesurgery gall bladder operation.

Timeline (cont’d) Oct 2001 ZEUS® Robotic Surgical System from Computer Motion receives FDA regulatory clearance. (ZEUS’s 3 rd arm is an AESOP voice-controlled robotic endoscope for visualization [Lanfranco et al, 2004]. ) Sept 2001 ZEUS robotic system developed by Computer Motion was used in the trans-Atlantic operation. A doctor in New York removed the diseased gallbladder of a 68 -year-old patient in Strasbourg, France. See [Marescaux, 2002] for details. * There are many more; these are just some highlights to give an idea about how medical robotics has evolved.

Robot Trivia The word "robot" was first used by Czech writer Karl Capek for his 1920 play, R. U. R. : Rossum's Universal Robots, in which artificial workers eventually overthrow their creators. But contrary to popular opinion, Karl Capek didn't invent the word "robot". He wanted to call the workers "labori" but his brother, cubist painter and writer Josef Capek, suggested they be called "robots". The Czech word "robota" means "forced work or labour".

Timeline l For another, more extensive timeline, see http: //biomed. brown. edu/Courses/BI 108/BI 10 8_2005_Groups/04/timeline. html

![“Robotic Surgery”: How it differs from “Computer-Assisted Surgery” (CAS)? l [Davies, 1999] differentiates between “Robotic Surgery”: How it differs from “Computer-Assisted Surgery” (CAS)? l [Davies, 1999] differentiates between](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-22.jpg)

“Robotic Surgery”: How it differs from “Computer-Assisted Surgery” (CAS)? l [Davies, 1999] differentiates between the two: – In CAS, the surgeon holds the tools and could ignore warnings to the contrary and cut into unsafe regions; whereas, a robot can be programmed to prevent motions into critical regions or only allow motions along a specified direction l – l computers might help in planning and positioning In robotic surgery, robots will hold the tools, providing greater accuracy and precision More recent developments, however, don’t fit easily into one of these categories based on the definitions offered by Davies (and later by [Bann et al, 2003]). – Consider telesurgery…

Benefits of “Computer-Assisted Surgery” l l l Some systems correct the surgeon’s tremor Higher accuracy Minimally Invasive Surgery Reduction of radiation exposure for both patient and surgeon Less time consuming interventions because of better planning and simulation [Schep et al, 2001]

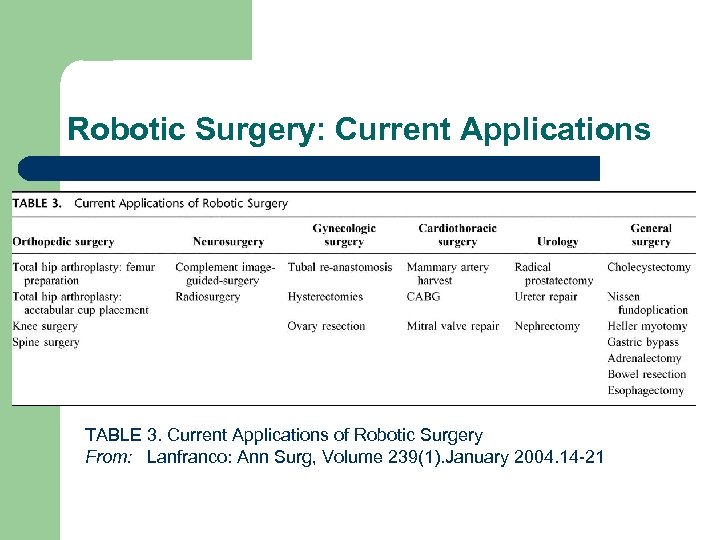

Robotic Surgery: Current Applications TABLE 3. Current Applications of Robotic Surgery From: Lanfranco: Ann Surg, Volume 239(1). January 2004. 14 -21

2 Main Types of Robotics for Surgery l l Those based on “image guidance” and Those aimed at obtaining minimal “invasiveness” [Dario et al, 1996] – For example l l Bone-mounted miniature robot Some achieve both – For example l l da Vinci Surgical System – a master-slave system Zeus – a master-slave system

![MARS: A Bone-Mounted Miniature Robot [Shoham et al, 2003] l Reasons given for slow MARS: A Bone-Mounted Miniature Robot [Shoham et al, 2003] l Reasons given for slow](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-26.jpg)

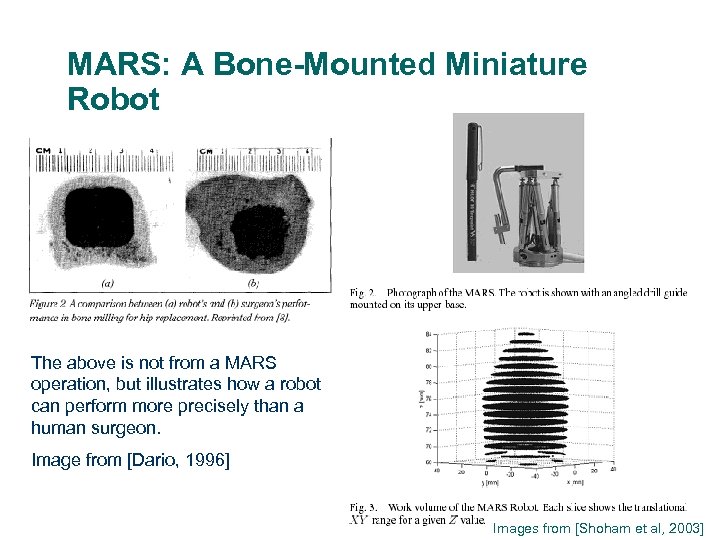

MARS: A Bone-Mounted Miniature Robot [Shoham et al, 2003] l Reasons given for slow uptake of Surgical Robots in the Operating Room: – – – Contemporary medical robots are voluminous. They occupy too much space and raise safety issues. Commercial surgical robot systems are expensive ($300, 000 to $1, 000). Thus, their use is limited to the few large research hospitals that can afford them. The patient anatomy needs to be immobilized by fixing it to the operating room table, or compensated for by tracking it in real time and adjusting the fixed robot position accordingly.

![MARS: A Bone-Mounted Miniature Robot [Shoham et al, 2003] l l MARS is a MARS: A Bone-Mounted Miniature Robot [Shoham et al, 2003] l l MARS is a](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-27.jpg)

MARS: A Bone-Mounted Miniature Robot [Shoham et al, 2003] l l MARS is a cylindrical 5 x 7 cm 3, 200 -g, six-degree-of-freedom parallel manipulator. Authors were developing two clinical applications to demonstrate the concept: 1) 2) l l surgical tools guiding for spinal pedicle screws placement; and drill guiding for distal locking screws in intramedullary nailing. In both cases, a tool guide attached to the robot is positioned at a planned location with a few intraoperative fluoroscopic X-ray images. Preliminary in-vitro experiments demonstrated the feasibility of this concept.

![MARS: A Bone-Mounted Miniature Robot [Shoham et al, 2003] l Design goals: – – MARS: A Bone-Mounted Miniature Robot [Shoham et al, 2003] l Design goals: – –](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-28.jpg)

MARS: A Bone-Mounted Miniature Robot [Shoham et al, 2003] l Design goals: – – – – – precise position and orientation of long, handheld surgical instruments, such as a drill or a needle, with respect to a surgical target; small work volume enclosing a sphere whose radius is several centimeters; rigid attachment to the bone; lightweight and compact structure; lockable structure at given configurations to provide rigid guidance; capable of withstanding lateral forces resulting from instrument guidance of up to 10 N; modular design to allow customization of the bone attachment and targeting guide for different surgical applications; repeatedly sterilizable in its entirety or easily covered with a sterile sleeve; quick and easy installation and removal from the bone.

MARS: A Bone-Mounted Miniature Robot The above is not from a MARS operation, but illustrates how a robot can perform more precisely than a human surgeon. Image from [Dario, 1996] Images from [Shoham et al, 2003]

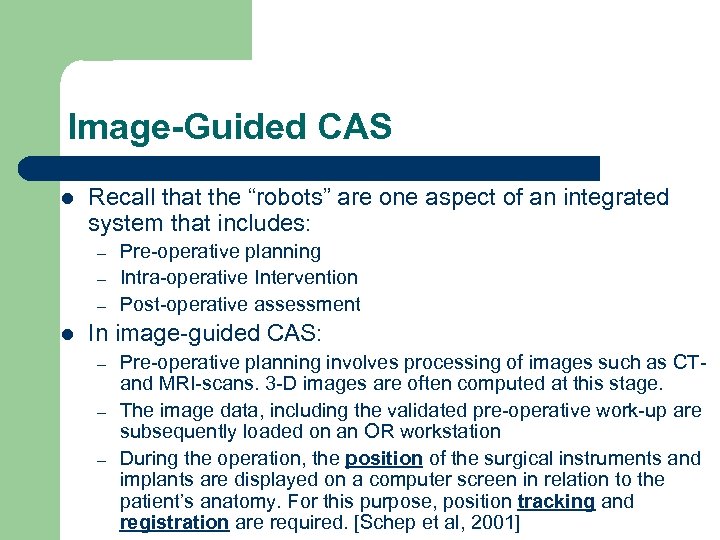

Image-Guided CAS l Recall that the “robots” are one aspect of an integrated system that includes: – – – l Pre-operative planning Intra-operative Intervention Post-operative assessment In image-guided CAS: – – – Pre-operative planning involves processing of images such as CT- and MRI-scans. 3 -D images are often computed at this stage. The image data, including the validated pre-operative work-up are subsequently loaded on an OR workstation During the operation, the position of the surgical instruments and implants are displayed on a computer screen in relation to the patient’s anatomy. For this purpose, position tracking and registration are required. [Schep et al, 2001]

![Image-Guided CAS: Instrument and Position Tracking [Schep et al, 2003] l The system has Image-Guided CAS: Instrument and Position Tracking [Schep et al, 2003] l The system has](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-31.jpg)

Image-Guided CAS: Instrument and Position Tracking [Schep et al, 2003] l The system has been compared with a global positioning system (GPS) – – – l l l car surgical instrument driver surgeon In surgical navigation, pre- or intra-operatively acquired digital radiographic images act as the roadmap. Key element is the tracking sensor, which identifies the instruments in order to determine their position. In a GPS, the tracking sensor is a satellite. Surgical tracking systems use magnetic, acoustic or optical signals for locating a target within the operating room.

![Image-Guided CAS: Instrument and Position Tracking (Cont’d) [Schep et al, 2003] l Most commonly Image-Guided CAS: Instrument and Position Tracking (Cont’d) [Schep et al, 2003] l Most commonly](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-32.jpg)

Image-Guided CAS: Instrument and Position Tracking (Cont’d) [Schep et al, 2003] l Most commonly used technique is tracking by (infrared) light emitting diodes (LEDs) or passive markers such as retroreflective spheres or disks. – – Shields with typically four or six LEDs/passive markers are attached to the instruments and the operated bone. To allow freedom of movement during surgery, the position of the target bone is also tracked. Therefore, a frame with LEDs or passive markers is attached to the skeleton, the so-called dynamic reference frame (DRF).

![Image-Guided CAS: Instrument and Position Tracking (Cont’d) [Schep et al, 2003] l The tracking Image-Guided CAS: Instrument and Position Tracking (Cont’d) [Schep et al, 2003] l The tracking](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-33.jpg)

Image-Guided CAS: Instrument and Position Tracking (Cont’d) [Schep et al, 2003] l The tracking sensor overlooking the surgical field receives the signals emitted by the LEDs/passive markers of both the DRF and the surgical instruments. l Subsequently, the position of the instruments is superimposed on the radiographic images of the operated bone.

![Image-Guided CAS: Registration of Pre. Operatively Obtained Images [Schep et al, 2003] l Registration Image-Guided CAS: Registration of Pre. Operatively Obtained Images [Schep et al, 2003] l Registration](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-34.jpg)

Image-Guided CAS: Registration of Pre. Operatively Obtained Images [Schep et al, 2003] l Registration is required to establish a relationship between the anatomy in the operating field and the anatomy displayed in pre -operative images. l The procedure can be roughly divided in two different kinds of techniques. – External markers l l – Requires additional operation to implant the markers Each marker on the patient is touched in a predefined order with a tracked instrument that registers it with a position on the pre-operative image Anatomic landmarks l l No operation needed to implant markers Registration of the landmarks can be done a couple of ways: Paired-point registration – a 3 D localiser is used to touch well-defined anatomic landmarks on the bone surface. 2) Surface registration – a random cluster of points is used instead of specific landmarks. The computer uses trial and error technique to match the touched bone surface area with the corresponding 3 -D image area 1)

![Image-Guided CAS Paired-point Registration Images from [Schep, 2003] Image-Guided CAS Paired-point Registration Images from [Schep, 2003]](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-35.jpg)

Image-Guided CAS Paired-point Registration Images from [Schep, 2003]

![Image-Guided CAS: Registration (Cont’d) l [Schep, 2003] also mentions 2 newer types of registration Image-Guided CAS: Registration (Cont’d) l [Schep, 2003] also mentions 2 newer types of registration](https://present5.com/presentation/2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4/image-36.jpg)

Image-Guided CAS: Registration (Cont’d) l [Schep, 2003] also mentions 2 newer types of registration which are non-invasive: – – Ultrasound Laser beams

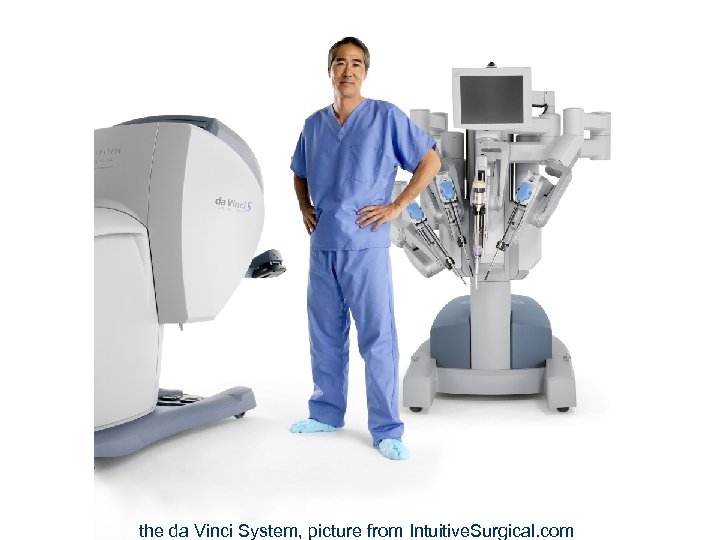

the da Vinci System, picture from Intuitive. Surgical. com

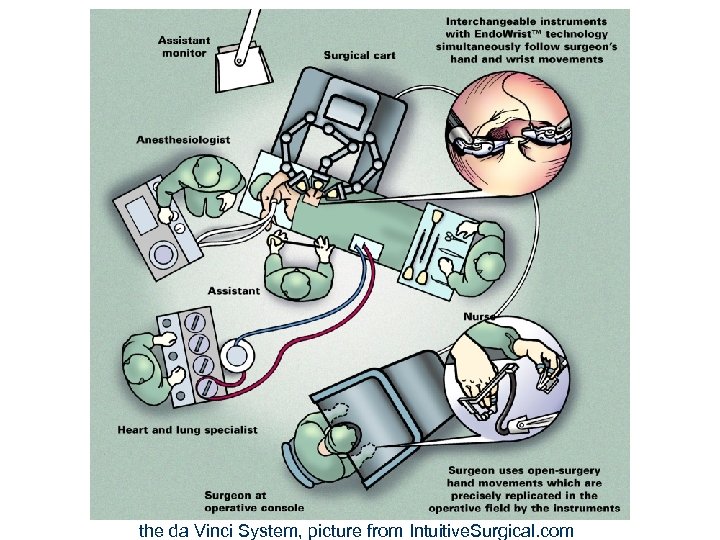

the da Vinci System, picture from Intuitive. Surgical. com

Da Vinci System in Action l video-clip – Recording by students in Brown Medical School (http: //biomed. brown. edu/Courses/BI 108_2005_Grou ps/04/davinci. html)

Summary l l l Medical Robotics have a bright future. Research and practice have shown that Robotic Surgery is safe, less invasive, and more accurate than surgery performed in the absence of robotics. It is still in its infancy, however [Lanfranco et al, 2003] so there’s plenty of opportunity.

Some Current Opportunities in Medical Robotics Research l l Robots with more autonomy to perform procedures Haptics research that will provide force-feedback to the surgeon manipulating the tools in master-slave systems [Schep et al, 2003] l Though initial experiences have been promising, CAS is still complex and sensitive to failures due to pitfalls in registration, tracking and instability of software. l A more sophisticated solution is automated registration by intra-operative imaging. – l l Flouroscopy based CAS is evolving rapidly (i. e. navigation in 3 D fluoroscopic images) An additional inconvenience is limitation in tracking techniques. Optical tracking requires a straight line of sight between the LEDs and the camera, which could be obstructed by the surgeon. More flexible tracking techniques with multi-angle detection of signals would allow a surgeon greater freedom of movement in OR.

References l l l l Bann et al (2003) Bann et al, Robotics in Surgery Boilot (2002) Classification of bacteria responsible for ENT and eye infections using the Cyranose system Dario et al (1996) Robotics for Medical Applications Davies (1999) A Review of Robotics in Surgery Lanfranco (2004) Robotic Surgery: A Current Perspective Marescaux et al (2002) Transcontinental Robot-Assisted Remote Telesurgery: Feasibility and Potential Applications Methil-Sudhakaran et al (2005) Development of a Medical Telediagnostic System with Tactile Haptic Interfaces Rovetta (2001) Biorobotics: An Instrument for an Improved Quality of Life. An Application for the Analysis of Neuromotor Diseases Sandini (2000) A Retina-Like CMOS Sensor and Its Applications Schep et al (2001) Computer assisted orthopaedic and trauma surgery: State of the art and future perspectives Shoham et al (2003) Bone-Mounted Miniature Robot for Surgical Procedures: Concept and Clinical Applications Sugano (2003) Computer-assisted orthopedic surgery Taylor (2003) Medical Robotics in Computer-Integrated Surgery

2ee352e572f6bdcef18f074ddbc0b2c4.ppt