4696a80ba4a707b117b1ace1d56494d4.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 28

Matrix Scorecards: A Tutorial

About Scorecards A good performance measurement system will measure multiple dimensions of performance, including results and behavior measures as needed. A scorecard is simply a framework for tracking multiple measures in a way that lets you see how you’re doing on each one, as well as how you’re doing on the whole relative to a goal level (expressed conveniently in one score. ) You may need measures in each of the following categories: Quantity, Quality, Timeliness, Financial, and Customer Satisfaction. Some of these measures check and balance others. For example, tracking both quantity and quality insures that you can’t increase quantity at the expense of quality. Similarly, if you track labor costs and order turnaround time, you can’t simply cut employee hours to lower labor costs if that worsens turnaround time. You want a mix of measures that, together, tells you how well you are doing. Scorecards permit you to track these data on a regular, consistent basis.

About Scorecards A well-designed scorecard can prevent trouble that would be caused by tying evaluation or incentives to a single measure. For example, paying salespeople commissions only based on the number or dollar value of sales can encourage them to promise customers items that can’t be delivered, or sell low-profit margin items, or sell to bad credit risks, and so on. A scorecard for salespeople that tracks sales volume and some measure of the quality of the sale (profitable orders or orders that were paid on time) can hedge against this. Measurement is the foundation of the performance system in your organization. You need a valid, comprehensive measurement system to use the data for: effective feedback or personnel evaluation activities; to see whether you are making progress on your strategic initiatives; to gauge the ongoing impact of organizational changes; or to pay people for their actual performance (instead of perceived performance based on manager opinion. ) If you are interested in and ongoing comprehensive measurement system, a weighted matrix kind of scorecard may be ideal. Now, let’s look at scorecard design.

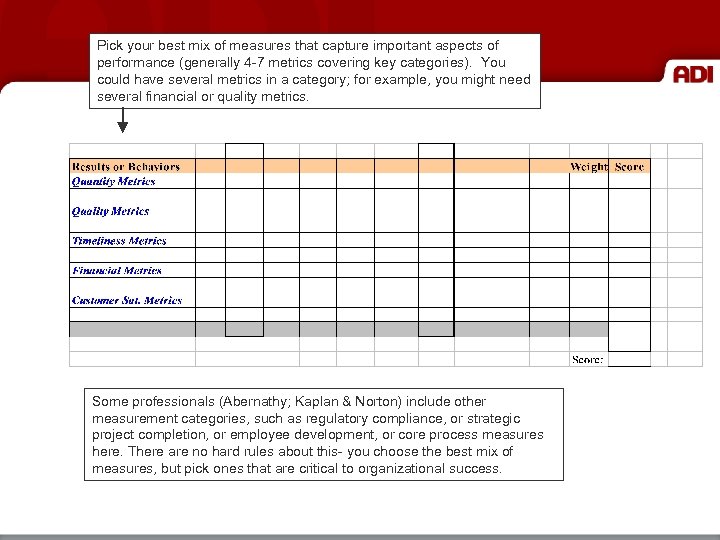

Pick your best mix of measures that capture important aspects of performance (generally 4 -7 metrics covering key categories). You could have several metrics in a category; for example, you might need several financial or quality metrics. Some professionals (Abernathy; Kaplan & Norton) include other measurement categories, such as regulatory compliance, or strategic project completion, or employee development, or core process measures here. There are no hard rules about this- you choose the best mix of measures, but pick ones that are critical to organizational success.

Metrics • Quantity: Amount of results or behavior producedusually expressed as a ratio. • • • Some Examples (not an exhaustive list): # sales orders/week average # customers served/hr tons of steel produced/employee % safe behaviors # regulatory violations per month # of cold calls made per salesperson per week

Metrics • Quality: Accuracy to standard, class (form or style) or novelty. Examples: • % error-free products or services (or defect rates*) • A rating from a Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scale used by a supervisor to judge quality of a sales rep’s behavior in a customer service interaction • $ waste or scrap * In world-class manufacturing for example, they may use the rigorous defects per million opportunities (DPMO) as a quality metric. Six Sigma standards strive to attain as few as 3. 4 DPMO! A 90% on a college exam might get you an A, but in fact that’s 100, 000 DPMO- poor by industrial standards!

Metrics • Timeliness: How long it takes to produce a result or behavior- usually relative to some deadline or goal. Examples: • Order turnaround time in minutes (time from order to delivery; generically any measure of duration of a performance cycle is called “cycle time”) • Days ahead or behind of schedule • % of on-time deliveries

Metrics • Financial: Revenue, costs (labor costs, materials costs, mgt. costs), cash flow, or bottom-line measures such as profit. • • Examples: $ in sales revenue/order $ in labor it takes on average to produce one widget days accounts spend in Accounts Receivable (unpaid by customers) $ in net profit obtained/quarter or per product line

Metrics • Customer Satisfaction: Soft (customer surveys) or hard data (something that customers do that indicates they are satisfied). • • Examples: Average customer survey rating % of customers who do repeat business with you # of customers who refer their friends to your business # customer complaints/month

Design Issues • Scope: Scorecards can be designed to measure individual performance, or for a team, a department or function, or even an entire company. • Some organizations have scorecards of every scope. The scorecards are different for each scope, but aligned and compatible with the other scorecards. • Scorecards for individuals track individual performance, but they can also include group or company-wide measures (like a customer satisfaction score that pertains to everyone, or a group results measure to encourage collaboration instead of competition. ) • Scorecards at different job levels may include similar metrics (e. g. , the same productivity metric for supervisor and middle manager) but they may be weighted differently to reflect different priorities or degree of influence.

Design Issues • Timeframe: Some metrics may update on one timeframe (e. g. , they make sense as weekly totals or averages), whereas other metrics may only update monthly or quarterly (like profit data). Choose timeframes so you can see important changes or trends. • Short timeframes increase apparent variability. Measures of sales per minute might fluctuate wildly, for example. Timeframes that are too long obscure important variations; the ideal timeframe lets you see order. • You can mix metrics with different timeframes on the same scorecard; the longer timeframe metrics simply generate line item scores that don’t change when the scores based on shorter timeframe metrics do. You could have a monthly scorecard that has some metrics tracking monthly averages or totals, and some metrics that track 3 -month averages.

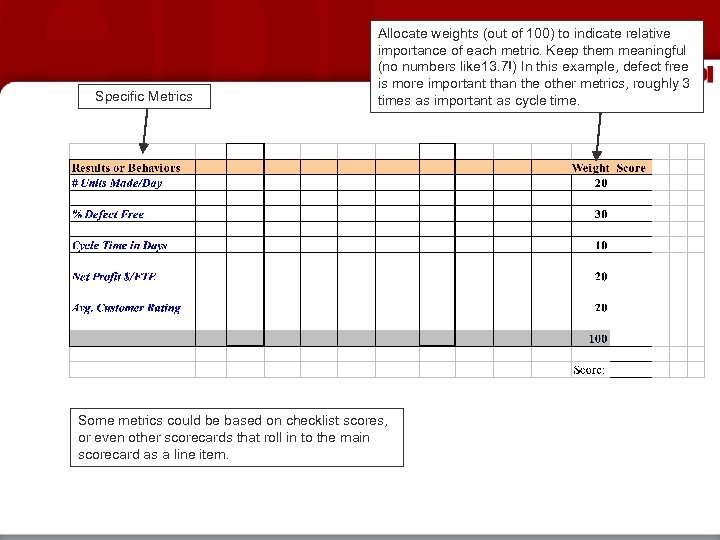

Specific Metrics Allocate weights (out of 100) to indicate relative importance of each metric. Keep them meaningful (no numbers like 13. 7!) In this example, defect free is more important than the other metrics, roughly 3 times as important as cycle time. Some metrics could be based on checklist scores, or even other scorecards that roll in to the main scorecard as a line item.

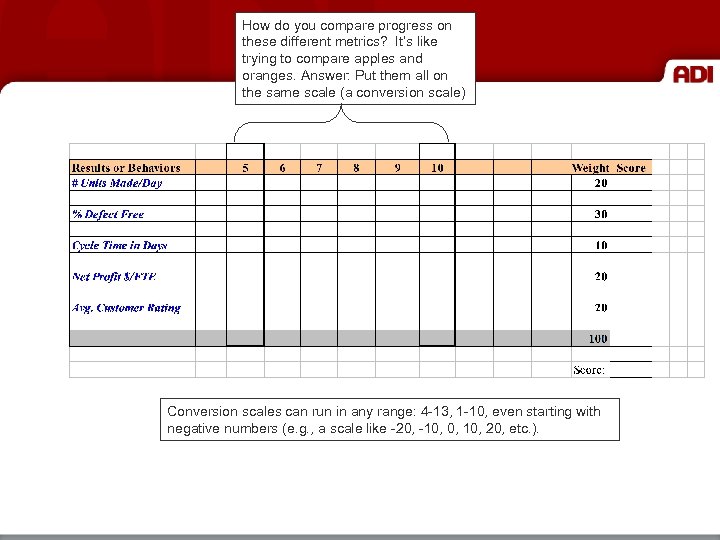

How do you compare progress on these different metrics? It’s like trying to compare apples and oranges. Answer: Put them all on the same scale (a conversion scale) Conversion scales can run in any range: 4 -13, 1 -10, even starting with negative numbers (e. g. , a scale like -20, -10, 0, 10, 20, etc. ).

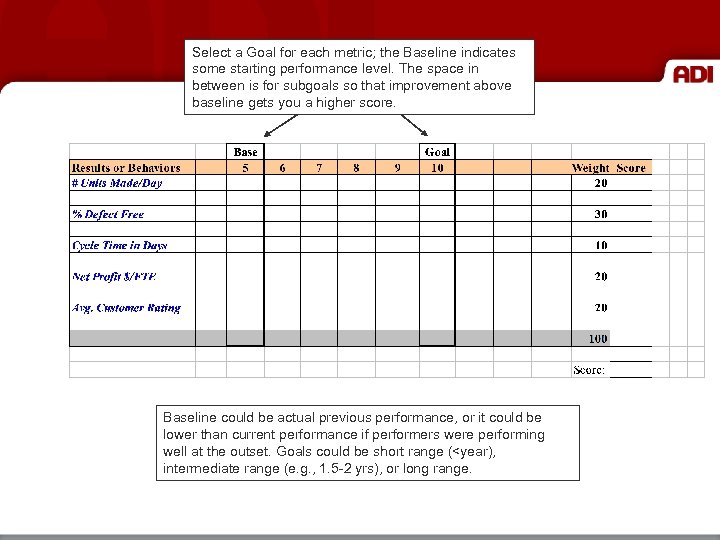

Select a Goal for each metric; the Baseline indicates some starting performance level. The space in between is for subgoals so that improvement above baseline gets you a higher score. Baseline could be actual previous performance, or it could be lower than current performance if performers were performing well at the outset. Goals could be short range (<year), intermediate range (e. g. , 1. 5 -2 yrs), or long range.

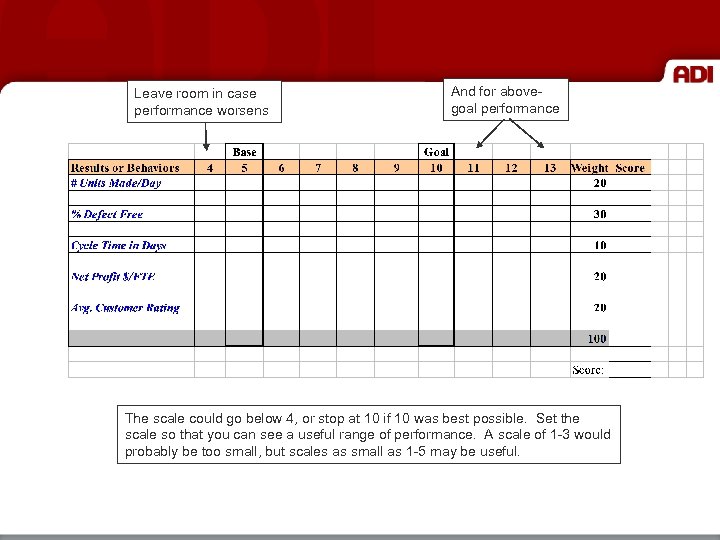

Leave room in case performance worsens And for abovegoal performance The scale could go below 4, or stop at 10 if 10 was best possible. Set the scale so that you can see a useful range of performance. A scale of 1 -3 would probably be too small, but scales as small as 1 -5 may be useful.

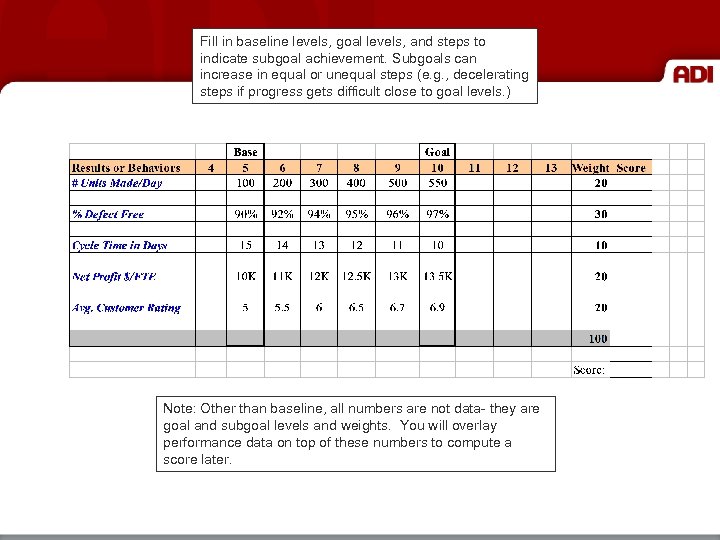

Fill in baseline levels, goal levels, and steps to indicate subgoal achievement. Subgoals can increase in equal or unequal steps (e. g. , decelerating steps if progress gets difficult close to goal levels. ) Note: Other than baseline, all numbers are not data- they are goal and subgoal levels and weights. You will overlay performance data on top of these numbers to compute a score later.

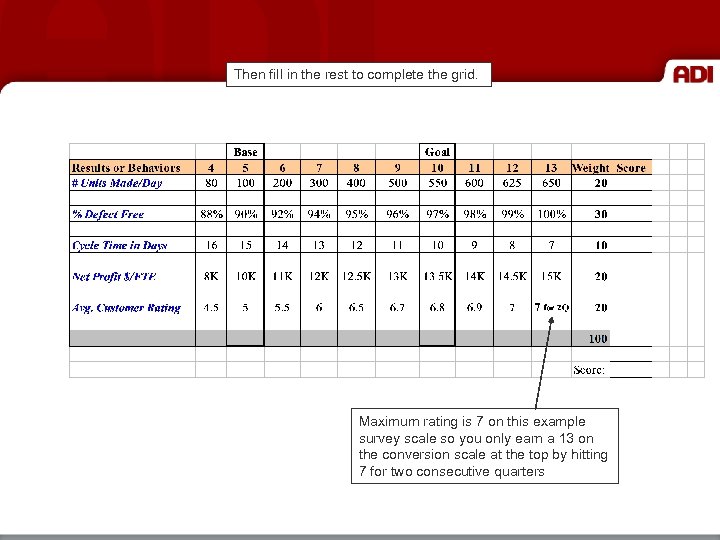

Then fill in the rest to complete the grid. Maximum rating is 7 on this example survey scale so you only earn a 13 on the conversion scale at the top by hitting 7 for two consecutive quarters

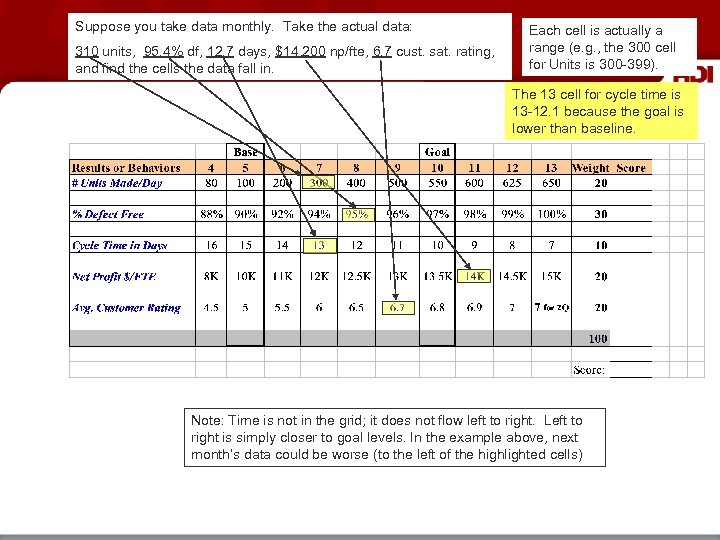

Suppose you take data monthly. Take the actual data: 310 units, 95. 4% df, 12. 7 days, $14, 200 np/fte, 6. 7 cust. sat. rating, and find the cells the data fall in. Each cell is actually a range (e. g. , the 300 cell for Units is 300 -399). The 13 cell for cycle time is 13 -12. 1 because the goal is lower than baseline. Note: Time is not in the grid; it does not flow left to right. Left to right is simply closer to goal levels. In the example above, next month’s data could be worse (to the left of the highlighted cells)

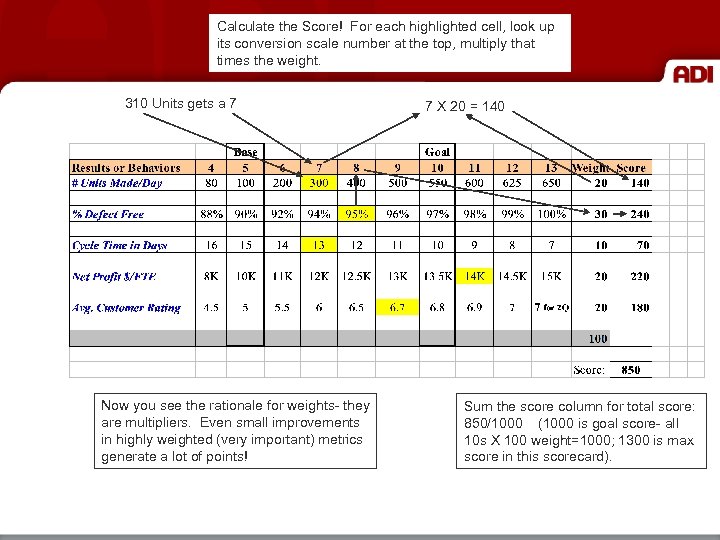

Calculate the Score! For each highlighted cell, look up its conversion scale number at the top, multiply that times the weight. 310 Units gets a 7 Now you see the rationale for weights- they are multipliers. Even small improvements in highly weighted (very important) metrics generate a lot of points! 7 X 20 = 140 Sum the score column for total score: 850/1000 (1000 is goal score- all 10 s X 100 weight=1000; 1300 is max score in this scorecard).

The Score • The score gives you 1 number that summarizes performance for that measurement cycle relative to goal. - You can also examine line scores to “drill down” and see what’s happening with each metric. - In the next measurement cycle, compute a new score using the new data. - Graph scores across time to look at trends!

Capping promotes Balance • Notice you get no additional points if you exceed the level in the right-most performance cell. • This “cap” prevents people from maximizing performance on one dimension at the expense of other dimensions. • To earn the most points possible, performance must be good across all measures, so the performers have an incentive to produce more balanced performances (taking into account the weights for each line item of course. )

Some Example Scorecards • These other example scorecards are fairly complex ones used by companies. They illustrate different layouts or different conversion scales.

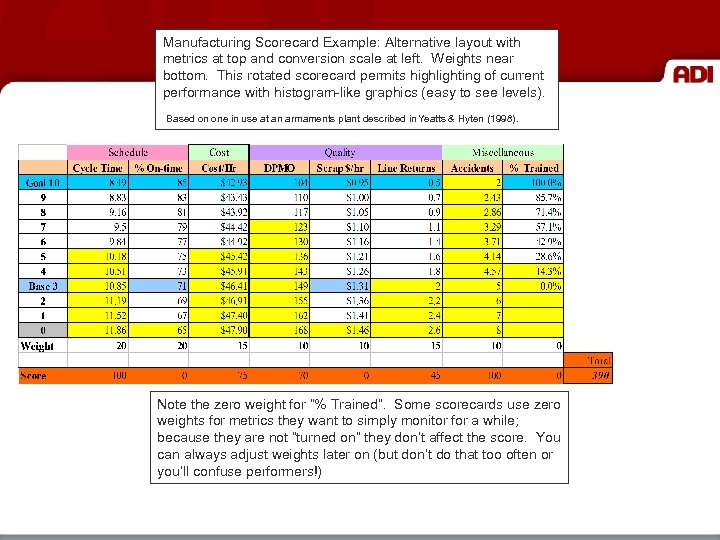

Manufacturing Scorecard Example: Alternative layout with metrics at top and conversion scale at left. Weights near bottom. This rotated scorecard permits highlighting of current performance with histogram-like graphics (easy to see levels). Based on one in use at an armaments plant described in Yeatts & Hyten (1998). Note the zero weight for “% Trained”. Some scorecards use zero weights for metrics they want to simply monitor for a while; because they are not “turned on” they don’t affect the score. You can always adjust weights later on (but don’t do that too often or you’ll confuse performers!)

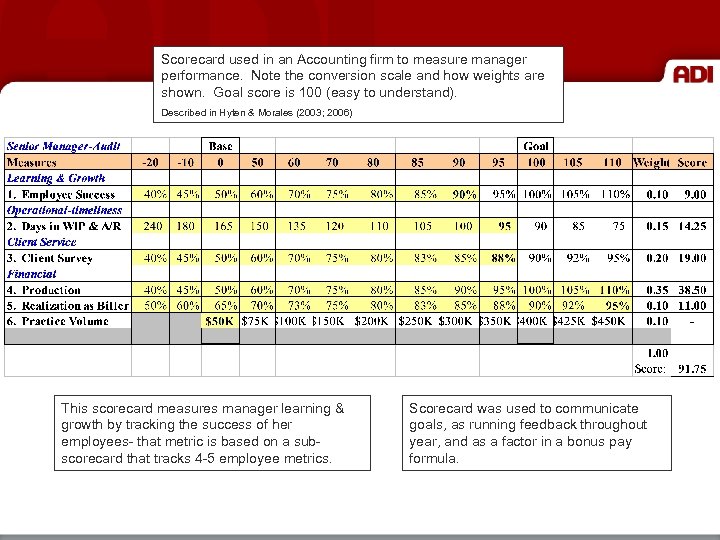

Scorecard used in an Accounting firm to measure manager performance. Note the conversion scale and how weights are shown. Goal score is 100 (easy to understand). Described in Hyten & Morales (2003; 2006) This scorecard measures manager learning & growth by tracking the success of her employees- that metric is based on a subscorecard that tracks 4 -5 employee metrics. Scorecard was used to communicate goals, as running feedback throughout year, and as a factor in a bonus pay formula.

Using Scorecards • Scorecards are very flexible tools. • You can use any combination of metrics that gives you the best picture of performance. • and any layout that has conversion scales at right angles to measurement categories. • Use graphics to highlight current performance levels and the scorecard can be both a table and a graph of sorts. • Emphasize objective data where you can. Subjective ratings data are appropriate for: • Judgments of the quality of performance by experienced or trained people if judgment is a more valid or complete assessment than hard counts. • Ratings by customers of satisfaction, where, unlike above, loose judgments are still informative.

Using Scorecards • If you’re measuring service performance, think about having some of the metrics measure objective impact of the service • Training: student learning, business impact of trained employees • Medical: patient improvement • Management: employee success • Make scorecard data accessible to performers to provide continuous data feedback. • Software versions can be linked to databases for automatic updating. • Tie scorecards reflecting individual performance to reinforcement systems.

Scorecard References Abernathy, W. (2000). Managing without supervising: Creating an organization-wide performance system. Perf. Sys Press. (See Ch. 7 for extensive discussion of scorecards; other chapters show possible metrics) Daniels, A. C. , & Daniels, J. E. (2004). Performance management: Changing behavior that drives organizational effectiveness. Performance Management Publications. (See Ch. 13) Eikenhout, N. , & Austin, J. (2005). Using goals, feedback, reinforcement, and a performance matrix to improve customer service in a large department store. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 24(3), 27 -62. (Case study that utilized scorecards) Hyten, C. & Morales, B. (2006, April). Profit-indexed, scorecard-based performance pay in a professional service firm. Paper presented at International Society for Performance Improvement conference, Dallas. Kaplan, R. & Norton, D. (1996). The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action. Harvard Business School Press. Morales, B. , Hyten, C. , & Porter, M. (2003, May). A multi-level performance measurement and pay for performance system: Design and organizational impact. In B. Cole (Chair), Building performance systems in an accounting firm: Five years of strategy and projects. Symposium at the meeting of the Association for Behavior Analysis, San Francisco. Riggs, J. (1986). Productivity by the objectives matrix. Manual by the Oregon Productivity Center at Oregon State University. (Riggs introduced the matrix type scorecard discussed here) Yeatts, D. , & Hyten, C. (1998). High-performing self-managed work teams: A comparison of theory to practice. Sage. (see Ch. 13)

ADI 3344 Peachtree Rd, Suite 1050 Atlanta, Georgia 30326 www. aubreydaniels. com

4696a80ba4a707b117b1ace1d56494d4.ppt