6162be8cb3009bb19122e7f72bec6dd7.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 55

Mark Wheeler Nottinghamshire Healthcare Trust Child & Adolescent Mental Health Service 22 nd April 2016 Do family therapists use photographs in their practice? How do family therapists find it helpful to use photographs in their practice?

Mark Wheeler Nottinghamshire Healthcare Trust Child & Adolescent Mental Health Service 22 nd April 2016 Do family therapists use photographs in their practice? How do family therapists find it helpful to use photographs in their practice?

Do family therapists use photographs in their practice? How do family therapists find it helpful to use photographs in their practice? An investigation

Do family therapists use photographs in their practice? How do family therapists find it helpful to use photographs in their practice? An investigation

Mark Wheeler Nottinghamshire Healthcare Trust Child & Adolescent Mental Health Service

Mark Wheeler Nottinghamshire Healthcare Trust Child & Adolescent Mental Health Service

Mark Wheeler UK Art Psychotherapist & Systemic Practitioner State Registered member of B. A. A. T Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society www. phototherapy. org. uk

Mark Wheeler UK Art Psychotherapist & Systemic Practitioner State Registered member of B. A. A. T Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society www. phototherapy. org. uk

Researcher position This study is the latest example of an obsession with photographs and photography, beginning when 10 years old arising from myopia & its correction, and fitting into a 3 generation family script. Acknowledgements This study was made possible by the interview participants who offered their time and expertise to contribute the data from which all else flows. Lesley Novelle, Gary Robinson and trainee patch supervision groups, and student support also made this research possible. My partner Heather helped with transcribing and so many other ways.

Researcher position This study is the latest example of an obsession with photographs and photography, beginning when 10 years old arising from myopia & its correction, and fitting into a 3 generation family script. Acknowledgements This study was made possible by the interview participants who offered their time and expertise to contribute the data from which all else flows. Lesley Novelle, Gary Robinson and trainee patch supervision groups, and student support also made this research possible. My partner Heather helped with transcribing and so many other ways.

Do family therapists use photographs in their practice? How do family therapists find it helpful to use photographs in their practice?

Do family therapists use photographs in their practice? How do family therapists find it helpful to use photographs in their practice?

“Every snapshot is a mirror with memory” (Weiser, 2007, p 4)

“Every snapshot is a mirror with memory” (Weiser, 2007, p 4)

It is hoped that a discussion about viewing and talking about photographs with families, in systemic terms, may be helpful to other practitioners. It was found that there is little recent research into the use of photographs in family therapy.

It is hoped that a discussion about viewing and talking about photographs with families, in systemic terms, may be helpful to other practitioners. It was found that there is little recent research into the use of photographs in family therapy.

Are there differences now that many people carry photos everywhere in their phones?

Are there differences now that many people carry photos everywhere in their phones?

The importance of family photographs in constructing and maintaining family stories is widely acknowledged, to the extent that it became one of themes in the fictional everyday story of country folk on BBC Radio, The Archers. After the great flood of Ambridge 2015, Clarie Grundy, one of the main characters in the long-running radio drama series, is most upset that a family photograph album had been destroyed in flooding affecting their family home. She delivered a soliloquy bemoaning that, “All the pictures of the boys as babies. . . [are] spoiled” (The Archers, 2015).

The importance of family photographs in constructing and maintaining family stories is widely acknowledged, to the extent that it became one of themes in the fictional everyday story of country folk on BBC Radio, The Archers. After the great flood of Ambridge 2015, Clarie Grundy, one of the main characters in the long-running radio drama series, is most upset that a family photograph album had been destroyed in flooding affecting their family home. She delivered a soliloquy bemoaning that, “All the pictures of the boys as babies. . . [are] spoiled” (The Archers, 2015).

Ethics The research project design was submitted for ethical approval to the agency and to the university. When changes were made to the design, this was notified to both organisations and resubmission made as appropriate.

Ethics The research project design was submitted for ethical approval to the agency and to the university. When changes were made to the design, this was notified to both organisations and resubmission made as appropriate.

Process A literature review was undertaken, offering context for contemporary practice. Three, purposefully sampled, qualified family therapists gave semi-structured interviews, reflecting on their practice. Their responses, primary source material, were analysed by In interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA; Smith, Flowers & Larkin, 2009)

Process A literature review was undertaken, offering context for contemporary practice. Three, purposefully sampled, qualified family therapists gave semi-structured interviews, reflecting on their practice. Their responses, primary source material, were analysed by In interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA; Smith, Flowers & Larkin, 2009)

The seminal texts on therapeutic practice using photographs were not written by family therapists: 'Phototherapy in Mental Health' (Krauss & Fryrear, eds, 1983). 'Photo-Art-Therapy', written from an Analytical Psychology (Jungian and post-Jungian) position (Fryrear & Corbett, 1992). 'Photo. Therapy Techniques: Exploring the Secrets of Personal Snapshots and Family Albums' (Weiser, 1993 & 1999). Weiser, originally a psychologist, describes her practice as systemic, particularly influenced by the intergenerational ideas of Murray Bowen. 'Beyond The Smile: The therapeutic use of the photograph' (Berman, 1993). 'Phototherapy in a Digital Age' (Loewenthal, ed. 2012).

The seminal texts on therapeutic practice using photographs were not written by family therapists: 'Phototherapy in Mental Health' (Krauss & Fryrear, eds, 1983). 'Photo-Art-Therapy', written from an Analytical Psychology (Jungian and post-Jungian) position (Fryrear & Corbett, 1992). 'Photo. Therapy Techniques: Exploring the Secrets of Personal Snapshots and Family Albums' (Weiser, 1993 & 1999). Weiser, originally a psychologist, describes her practice as systemic, particularly influenced by the intergenerational ideas of Murray Bowen. 'Beyond The Smile: The therapeutic use of the photograph' (Berman, 1993). 'Phototherapy in a Digital Age' (Loewenthal, ed. 2012).

The literature review summaries were based on the Dallos & Vetere (2005) critique criteria. The effective search words were: family therapy systemic psychotherapy systemic practice phototherapy photographs photograph album A lack of results led to exploration of references lists and personal communication with authors

The literature review summaries were based on the Dallos & Vetere (2005) critique criteria. The effective search words were: family therapy systemic psychotherapy systemic practice phototherapy photographs photograph album A lack of results led to exploration of references lists and personal communication with authors

Eventually, after further suggestions by Judy Weiser of The Phototherapy Centre (Vancouver), 72 full texts were optimistically obtained and read A total of 11 articles and chapters met the criteria for inclusion, 5 by the same author (Entin, all in refs). Only two were written in the 21 st century (Cook & Poulson, 2011; de Bernart, 2013). There is scant peer reviewed literature on therapeutic use of photographs by family therapists.

Eventually, after further suggestions by Judy Weiser of The Phototherapy Centre (Vancouver), 72 full texts were optimistically obtained and read A total of 11 articles and chapters met the criteria for inclusion, 5 by the same author (Entin, all in refs). Only two were written in the 21 st century (Cook & Poulson, 2011; de Bernart, 2013). There is scant peer reviewed literature on therapeutic use of photographs by family therapists.

The 11 articles identified as appropriate are in the context of family therapy cultural landscapes. “The shift to second-order cybernetics has been seen as centred on a critique of the first applications of systems theory. . . the emphasis moved to an exploration of the meanings, beliefs, explanations and stories held by family members” (Dallos & Draper, 2010, p 66)

The 11 articles identified as appropriate are in the context of family therapy cultural landscapes. “The shift to second-order cybernetics has been seen as centred on a critique of the first applications of systems theory. . . the emphasis moved to an exploration of the meanings, beliefs, explanations and stories held by family members” (Dallos & Draper, 2010, p 66)

This coincides with similar shifts in ideas in art and cultural theory, moving from 'decoding' photographs to 'bringing meaning' to photographs. These too, emerge from the ideas of Viktor Schklovsky (via Lev Vygostky in family therapy), Jaques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, etc

This coincides with similar shifts in ideas in art and cultural theory, moving from 'decoding' photographs to 'bringing meaning' to photographs. These too, emerge from the ideas of Viktor Schklovsky (via Lev Vygostky in family therapy), Jaques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, etc

Authors like Barthes identified ideas about finding meaning in literary text analogous with finding meaning in photographs. Lax argues that, “The examination of the text as an analogy for human systems has become popular recently in different disciplines. . . In clinical practice the text analogy has been utilized by White and Epston (1990) and Penn and Sheinberg (1991)”, Lax (1992, p 73)

Authors like Barthes identified ideas about finding meaning in literary text analogous with finding meaning in photographs. Lax argues that, “The examination of the text as an analogy for human systems has become popular recently in different disciplines. . . In clinical practice the text analogy has been utilized by White and Epston (1990) and Penn and Sheinberg (1991)”, Lax (1992, p 73)

The literature review revealed other articles and book chapters that might be described as systemic. None of these were written by authors identified as “family therapists” There has been a change from photographic prints to smart-phones, in domestic photography, and a shift towards socially constructed approaches (Mc. Namee & Gergen, 1992) since most literature on this subject was published.

The literature review revealed other articles and book chapters that might be described as systemic. None of these were written by authors identified as “family therapists” There has been a change from photographic prints to smart-phones, in domestic photography, and a shift towards socially constructed approaches (Mc. Namee & Gergen, 1992) since most literature on this subject was published.

Family photographs and photographs albums can be propaganda (Spence, 1984, 1986 b; Seabrook, 1991, p 178) as the selfie craze makes even more explicit

Family photographs and photographs albums can be propaganda (Spence, 1984, 1986 b; Seabrook, 1991, p 178) as the selfie craze makes even more explicit

Photographs contain and reinforce stories in families and this has been encountered in practice with families. Spence and Holland (2000) and Sontag (1977) have written about these acts of narrative construction and Hirsch (2012) has described the reclaiming of lost family stories from photograph albums.

Photographs contain and reinforce stories in families and this has been encountered in practice with families. Spence and Holland (2000) and Sontag (1977) have written about these acts of narrative construction and Hirsch (2012) has described the reclaiming of lost family stories from photograph albums.

Photographs also prompt stories, to the extent that novelists have been inspired by photographs (Coe, 2004) to imagine family histories that might connect collections of photographs. De Bernart (2013, p 123) describes photography as “reverse prophecy”

Photographs also prompt stories, to the extent that novelists have been inspired by photographs (Coe, 2004) to imagine family histories that might connect collections of photographs. De Bernart (2013, p 123) describes photography as “reverse prophecy”

At the end of the twentieth century family therapy literature had recently focused on “Language generating aspects of human meaning systems to the exclusion of other methods of communication”, (Webster and Huffington, 1993, p 22 -23) Our understanding, in the context of family therapy is likely to come through words, which in the presence of pictures might offer us 'bothand' opportunities.

At the end of the twentieth century family therapy literature had recently focused on “Language generating aspects of human meaning systems to the exclusion of other methods of communication”, (Webster and Huffington, 1993, p 22 -23) Our understanding, in the context of family therapy is likely to come through words, which in the presence of pictures might offer us 'bothand' opportunities.

Since the appearance of the Kodak Brownie camera, photographs have become ‘signs’ in and of family life. Photographs succeed in being effective signs in that they are simultaneously both the signifiers and are representations of that which is signified, and are interpreted as such.

Since the appearance of the Kodak Brownie camera, photographs have become ‘signs’ in and of family life. Photographs succeed in being effective signs in that they are simultaneously both the signifiers and are representations of that which is signified, and are interpreted as such.

The study of the meaning of photographs (Barthes, 1977, 2000; Burgin, 1982; Kozloff, 1979) has been concurrent with an increased interest in meaning in family therapy practice (Mc. Namee & Gergen, 1992). In the study of photographic meaning a whole language has developed based on the terminology of textual analysis.

The study of the meaning of photographs (Barthes, 1977, 2000; Burgin, 1982; Kozloff, 1979) has been concurrent with an increased interest in meaning in family therapy practice (Mc. Namee & Gergen, 1992). In the study of photographic meaning a whole language has developed based on the terminology of textual analysis.

![This study of meanings in photography (Benjamen, [1936]1999; Barthes, 1977; Burgin, 1982; Kozloff, 1979) This study of meanings in photography (Benjamen, [1936]1999; Barthes, 1977; Burgin, 1982; Kozloff, 1979)](https://present5.com/presentation/6162be8cb3009bb19122e7f72bec6dd7/image-26.jpg) This study of meanings in photography (Benjamen, [1936]1999; Barthes, 1977; Burgin, 1982; Kozloff, 1979) has much in common with both the structuralist and post-modern studies of meaning (Cronen & Pearce 1985; Anderson, 2007; Bertrando, 2007) in conversation in family therapy. The history of photography runs alongside the history of psychological therapies. There has been mutual influence between these activities, from psychiatric work with photographs in the first decade of photography onwards.

This study of meanings in photography (Benjamen, [1936]1999; Barthes, 1977; Burgin, 1982; Kozloff, 1979) has much in common with both the structuralist and post-modern studies of meaning (Cronen & Pearce 1985; Anderson, 2007; Bertrando, 2007) in conversation in family therapy. The history of photography runs alongside the history of psychological therapies. There has been mutual influence between these activities, from psychiatric work with photographs in the first decade of photography onwards.

Interviewee B described how stories can be concealed in photographs, drawing on movies for examples that might emerge in conversations with families. Interviewee B describes biomedical model of 'truth', and that the presence of photographs provides opportunities for change and for different stories and how the dilemmas people face may offer opportunities for change.

Interviewee B described how stories can be concealed in photographs, drawing on movies for examples that might emerge in conversations with families. Interviewee B describes biomedical model of 'truth', and that the presence of photographs provides opportunities for change and for different stories and how the dilemmas people face may offer opportunities for change.

Interviewee B described how stories can be concealed in photographs, drawing on movies for examples that might emerge in conversations with families. Interviewee B describes biomedical model of 'truth', and that the presence of photographs provides opportunities for change and for different stories and how the dilemmas people face may offer opportunities for change.

Interviewee B described how stories can be concealed in photographs, drawing on movies for examples that might emerge in conversations with families. Interviewee B describes biomedical model of 'truth', and that the presence of photographs provides opportunities for change and for different stories and how the dilemmas people face may offer opportunities for change.

The three family therapists who participated in this study described their practice with photographs with families. They described practice led by, and matched to, those families who find it helpful. Participation in the study enabled practitioners to notice their competence, and consider increasing their practice with photographs.

The three family therapists who participated in this study described their practice with photographs with families. They described practice led by, and matched to, those families who find it helpful. Participation in the study enabled practitioners to notice their competence, and consider increasing their practice with photographs.

I attended art school during a fertile period of feminist critique of photography's portrayal of women's roles (Spence, 1984). I met or worked with women who were developing practices with photographs, including Spence (1986), Martin (1999), and Weiser (1993), shortly afterwards and I am influenced by their ideas in subsequent encounters with images. These ideas act contextually on my responses during the semistructured interviews and my reading and coding of the texts.

I attended art school during a fertile period of feminist critique of photography's portrayal of women's roles (Spence, 1984). I met or worked with women who were developing practices with photographs, including Spence (1986), Martin (1999), and Weiser (1993), shortly afterwards and I am influenced by their ideas in subsequent encounters with images. These ideas act contextually on my responses during the semistructured interviews and my reading and coding of the texts.

Interviewee A described enthusiastically how our social encounters now include the showing of photos in phones and B described it in sessions. “what you do with your friends these days. . you know. . . You go for a coffee with your friends and you're talking about something. . you haven't been talking 5 minutes before it twigs and you get your phone out and you're either showing a text, or a photo, or something like that” Interviewee A. “Now people are always showing you things on their phone, frequently showing you things, as recordings” Interviewee B.

Interviewee A described enthusiastically how our social encounters now include the showing of photos in phones and B described it in sessions. “what you do with your friends these days. . you know. . . You go for a coffee with your friends and you're talking about something. . you haven't been talking 5 minutes before it twigs and you get your phone out and you're either showing a text, or a photo, or something like that” Interviewee A. “Now people are always showing you things on their phone, frequently showing you things, as recordings” Interviewee B.

Each interviewee had examples to offer of very different practice with photographs. Photographs were used in 'tool-kits' of happy places and happy times (interviewee A), self image (interviewee C), less substantive expression than language (interviewee B), engagement (all interviews), eliciting untold stories (all interviewees).

Each interviewee had examples to offer of very different practice with photographs. Photographs were used in 'tool-kits' of happy places and happy times (interviewee A), self image (interviewee C), less substantive expression than language (interviewee B), engagement (all interviews), eliciting untold stories (all interviewees).

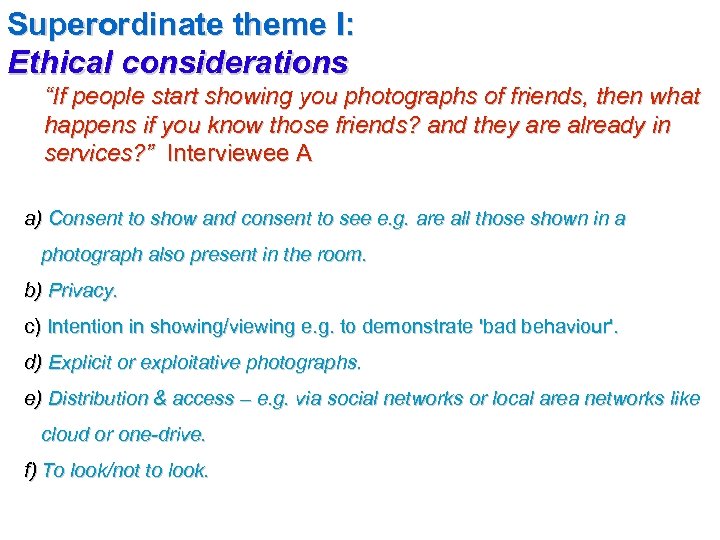

Superordinate theme I: Ethical considerations “If people start showing you photographs of friends, then what happens if you know those friends? and they are already in services? ” Interviewee A a) Consent to show and consent to see e. g. are all those shown in a photograph also present in the room. b) Privacy. c) Intention in showing/viewing e. g. to demonstrate 'bad behaviour'. d) Explicit or exploitative photographs. e) Distribution & access – e. g. via social networks or local area networks like cloud or one-drive. f) To look/not to look.

Superordinate theme I: Ethical considerations “If people start showing you photographs of friends, then what happens if you know those friends? and they are already in services? ” Interviewee A a) Consent to show and consent to see e. g. are all those shown in a photograph also present in the room. b) Privacy. c) Intention in showing/viewing e. g. to demonstrate 'bad behaviour'. d) Explicit or exploitative photographs. e) Distribution & access – e. g. via social networks or local area networks like cloud or one-drive. f) To look/not to look.

![Superordinate theme II: Untold and differently told stories “[Using photographs] specifically fits with a Superordinate theme II: Untold and differently told stories “[Using photographs] specifically fits with a](https://present5.com/presentation/6162be8cb3009bb19122e7f72bec6dd7/image-34.jpg) Superordinate theme II: Untold and differently told stories “[Using photographs] specifically fits with a narrative model, in terms of trying to create new identities, new stories about people's identity. ” Interviewee C a) Meaning of photo changed by therapy activity e. g. from being thought to look 'fat'. b) Intention to show photo/video being subverted by content showing different story. c) Language can fix stories in families – photos can unfix. d) Tool-kit of happy times.

Superordinate theme II: Untold and differently told stories “[Using photographs] specifically fits with a narrative model, in terms of trying to create new identities, new stories about people's identity. ” Interviewee C a) Meaning of photo changed by therapy activity e. g. from being thought to look 'fat'. b) Intention to show photo/video being subverted by content showing different story. c) Language can fix stories in families – photos can unfix. d) Tool-kit of happy times.

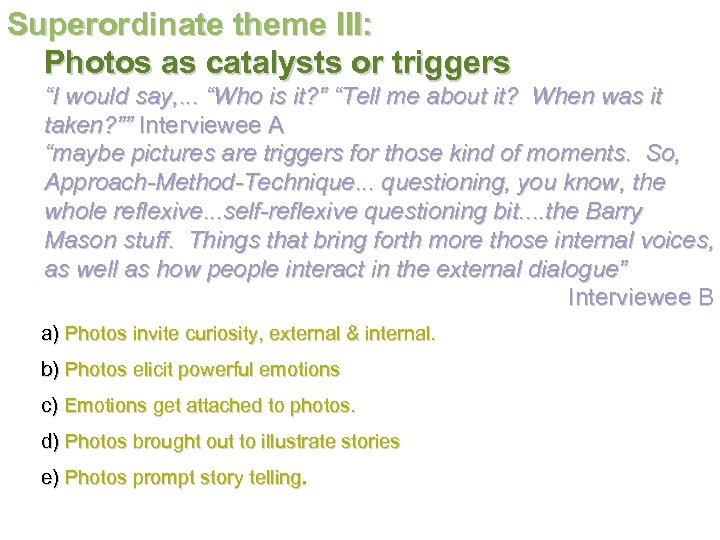

Superordinate theme III: Photos as catalysts or triggers “I would say, . . . “Who is it? ” “Tell me about it? When was it taken? ”” Interviewee A “maybe pictures are triggers for those kind of moments. So, Approach-Method-Technique. . . questioning, you know, the whole reflexive. . . self-reflexive questioning bit. . the Barry Mason stuff. Things that bring forth more those internal voices, as well as how people interact in the external dialogue” Interviewee B a) Photos invite curiosity, external & internal. b) Photos elicit powerful emotions c) Emotions get attached to photos. d) Photos brought out to illustrate stories e) Photos prompt story telling.

Superordinate theme III: Photos as catalysts or triggers “I would say, . . . “Who is it? ” “Tell me about it? When was it taken? ”” Interviewee A “maybe pictures are triggers for those kind of moments. So, Approach-Method-Technique. . . questioning, you know, the whole reflexive. . . self-reflexive questioning bit. . the Barry Mason stuff. Things that bring forth more those internal voices, as well as how people interact in the external dialogue” Interviewee B a) Photos invite curiosity, external & internal. b) Photos elicit powerful emotions c) Emotions get attached to photos. d) Photos brought out to illustrate stories e) Photos prompt story telling.

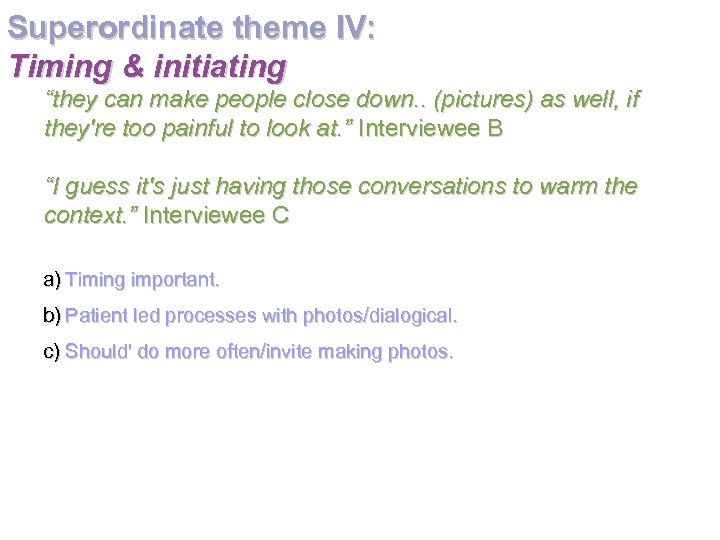

Superordinate theme IV: Timing & initiating “they can make people close down. . (pictures) as well, if they're too painful to look at. ” Interviewee B “I guess it's just having those conversations to warm the context. ” Interviewee C a) Timing important. b) Patient led processes with photos/dialogical. c) Should' do more often/invite making photos.

Superordinate theme IV: Timing & initiating “they can make people close down. . (pictures) as well, if they're too painful to look at. ” Interviewee B “I guess it's just having those conversations to warm the context. ” Interviewee C a) Timing important. b) Patient led processes with photos/dialogical. c) Should' do more often/invite making photos.

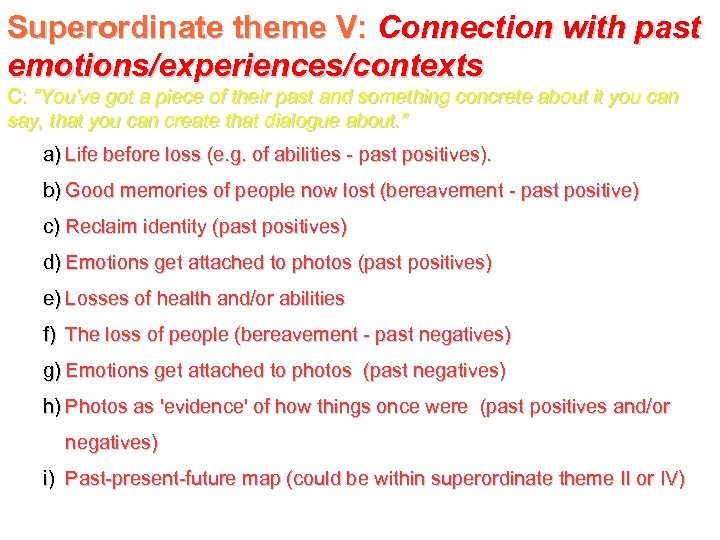

Superordinate theme V: Connection with past emotions/experiences/contexts C: “You've got a piece of their past and something concrete about it you can say, that you can create that dialogue about. ” a) Life before loss (e. g. of abilities - past positives). b) Good memories of people now lost (bereavement - past positive) c) Reclaim identity (past positives) d) Emotions get attached to photos (past positives) e) Losses of health and/or abilities f) The loss of people (bereavement - past negatives) g) Emotions get attached to photos (past negatives) h) Photos as 'evidence' of how things once were (past positives and/or negatives) i) Past-present-future map (could be within superordinate theme II or IV)

Superordinate theme V: Connection with past emotions/experiences/contexts C: “You've got a piece of their past and something concrete about it you can say, that you can create that dialogue about. ” a) Life before loss (e. g. of abilities - past positives). b) Good memories of people now lost (bereavement - past positive) c) Reclaim identity (past positives) d) Emotions get attached to photos (past positives) e) Losses of health and/or abilities f) The loss of people (bereavement - past negatives) g) Emotions get attached to photos (past negatives) h) Photos as 'evidence' of how things once were (past positives and/or negatives) i) Past-present-future map (could be within superordinate theme II or IV)

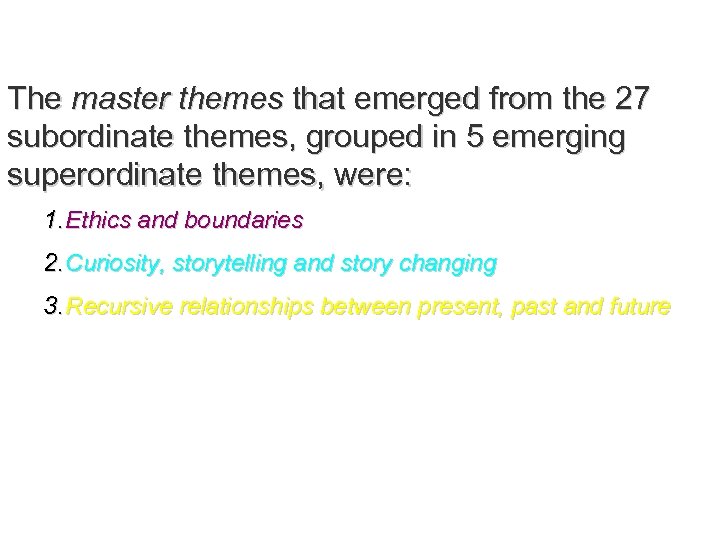

The master themes that emerged from the 27 subordinate themes, grouped in 5 emerging superordinate themes, were: 1. Ethics and boundaries 2. Curiosity, storytelling and story changing 3. Recursive relationships between present, past and future

The master themes that emerged from the 27 subordinate themes, grouped in 5 emerging superordinate themes, were: 1. Ethics and boundaries 2. Curiosity, storytelling and story changing 3. Recursive relationships between present, past and future

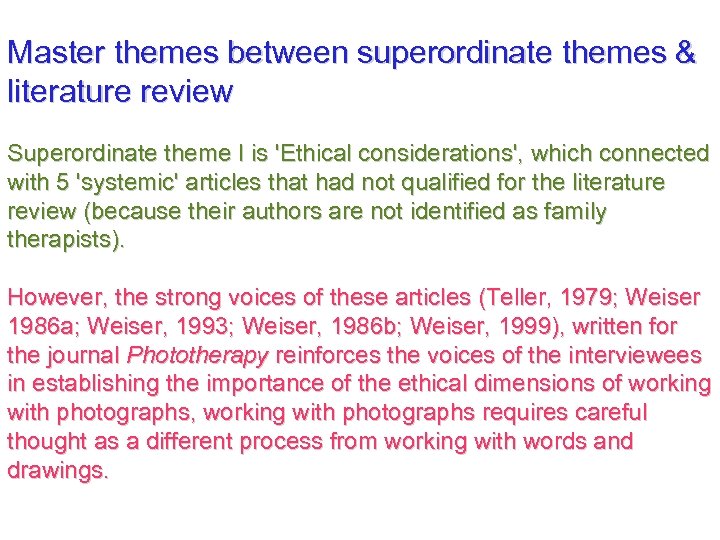

Master themes between superordinate themes & literature review Superordinate theme I is 'Ethical considerations', which connected with 5 'systemic' articles that had not qualified for the literature review (because their authors are not identified as family therapists). However, the strong voices of these articles (Teller, 1979; Weiser 1986 a; Weiser, 1993; Weiser, 1986 b; Weiser, 1999), written for the journal Phototherapy reinforces the voices of the interviewees in establishing the importance of the ethical dimensions of working with photographs, working with photographs requires careful thought as a different process from working with words and drawings.

Master themes between superordinate themes & literature review Superordinate theme I is 'Ethical considerations', which connected with 5 'systemic' articles that had not qualified for the literature review (because their authors are not identified as family therapists). However, the strong voices of these articles (Teller, 1979; Weiser 1986 a; Weiser, 1993; Weiser, 1986 b; Weiser, 1999), written for the journal Phototherapy reinforces the voices of the interviewees in establishing the importance of the ethical dimensions of working with photographs, working with photographs requires careful thought as a different process from working with words and drawings.

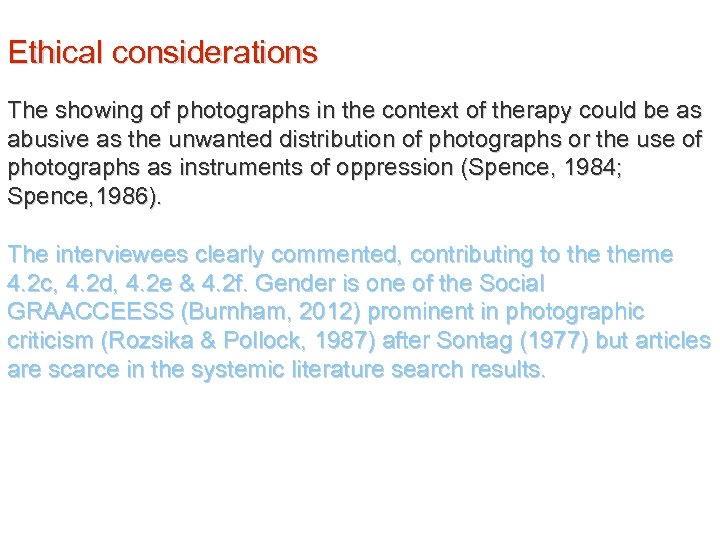

Ethical considerations The showing of photographs in the context of therapy could be as abusive as the unwanted distribution of photographs or the use of photographs as instruments of oppression (Spence, 1984; Spence, 1986). The interviewees clearly commented, contributing to theme 4. 2 c, 4. 2 d, 4. 2 e & 4. 2 f. Gender is one of the Social GRAACCEESS (Burnham, 2012) prominent in photographic criticism (Rozsika & Pollock, 1987) after Sontag (1977) but articles are scarce in the systemic literature search results.

Ethical considerations The showing of photographs in the context of therapy could be as abusive as the unwanted distribution of photographs or the use of photographs as instruments of oppression (Spence, 1984; Spence, 1986). The interviewees clearly commented, contributing to theme 4. 2 c, 4. 2 d, 4. 2 e & 4. 2 f. Gender is one of the Social GRAACCEESS (Burnham, 2012) prominent in photographic criticism (Rozsika & Pollock, 1987) after Sontag (1977) but articles are scarce in the systemic literature search results.

The interviewees' practice has both progressed from some of the published ideas and continues to resonate with the literature. Two therapists recounted examples of families wishing to show videos recorded of a young person behaving badly (in the view of the parents) and were shown despite reluctance on the part of therapist. Instead of the 'bad behaviour', one therapist witnessed a different story of a frightened young person and the other, a different situational circularity. “What I find helpful is really that meaning generation around photographs. It gives you another opportunity to ask questions in a different way, with a different type of evidence in front of you” Interviewee C

The interviewees' practice has both progressed from some of the published ideas and continues to resonate with the literature. Two therapists recounted examples of families wishing to show videos recorded of a young person behaving badly (in the view of the parents) and were shown despite reluctance on the part of therapist. Instead of the 'bad behaviour', one therapist witnessed a different story of a frightened young person and the other, a different situational circularity. “What I find helpful is really that meaning generation around photographs. It gives you another opportunity to ask questions in a different way, with a different type of evidence in front of you” Interviewee C

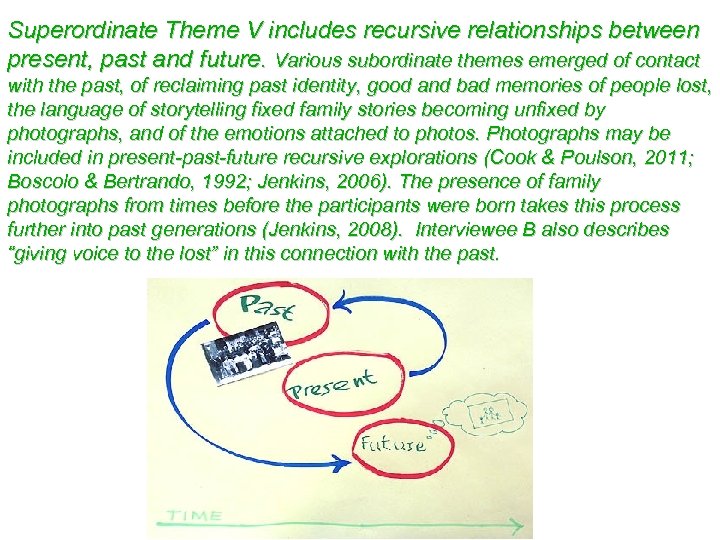

Superordinate Theme V includes recursive relationships between present, past and future. Various subordinate themes emerged of contact with the past, of reclaiming past identity, good and bad memories of people lost, the language of storytelling fixed family stories becoming unfixed by photographs, and of the emotions attached to photos. Photographs may be included in present-past-future recursive explorations (Cook & Poulson, 2011; Boscolo & Bertrando, 1992; Jenkins, 2006). The presence of family photographs from times before the participants were born takes this process further into past generations (Jenkins, 2008). Interviewee B also describes “giving voice to the lost” in this connection with the past.

Superordinate Theme V includes recursive relationships between present, past and future. Various subordinate themes emerged of contact with the past, of reclaiming past identity, good and bad memories of people lost, the language of storytelling fixed family stories becoming unfixed by photographs, and of the emotions attached to photos. Photographs may be included in present-past-future recursive explorations (Cook & Poulson, 2011; Boscolo & Bertrando, 1992; Jenkins, 2006). The presence of family photographs from times before the participants were born takes this process further into past generations (Jenkins, 2008). Interviewee B also describes “giving voice to the lost” in this connection with the past.

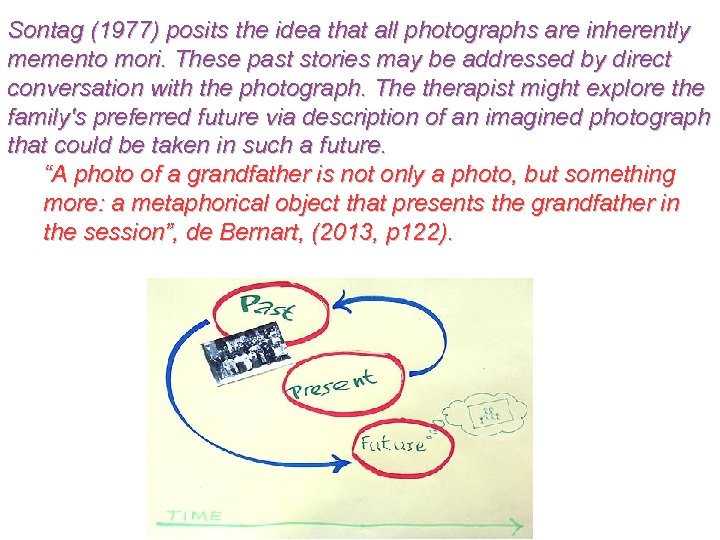

Sontag (1977) posits the idea that all photographs are inherently memento mori. These past stories may be addressed by direct conversation with the photograph. The therapist might explore the family's preferred future via description of an imagined photograph that could be taken in such a future. “A photo of a grandfather is not only a photo, but something more: a metaphorical object that presents the grandfather in the session”, de Bernart, (2013, p 122).

Sontag (1977) posits the idea that all photographs are inherently memento mori. These past stories may be addressed by direct conversation with the photograph. The therapist might explore the family's preferred future via description of an imagined photograph that could be taken in such a future. “A photo of a grandfather is not only a photo, but something more: a metaphorical object that presents the grandfather in the session”, de Bernart, (2013, p 122).

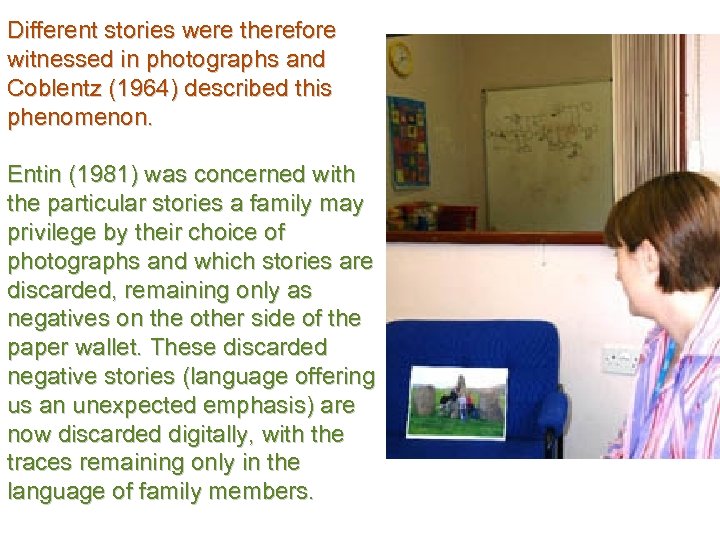

Different stories were therefore witnessed in photographs and Coblentz (1964) described this phenomenon. Entin (1981) was concerned with the particular stories a family may privilege by their choice of photographs and which stories are discarded, remaining only as negatives on the other side of the paper wallet. These discarded negative stories (language offering us an unexpected emphasis) are now discarded digitally, with the traces remaining only in the language of family members.

Different stories were therefore witnessed in photographs and Coblentz (1964) described this phenomenon. Entin (1981) was concerned with the particular stories a family may privilege by their choice of photographs and which stories are discarded, remaining only as negatives on the other side of the paper wallet. These discarded negative stories (language offering us an unexpected emphasis) are now discarded digitally, with the traces remaining only in the language of family members.

What we see in the picture or the text, what is 'denoted', is the literal content of the photograph or text. It is the "literal" denotation, the recognition of identifiable object in the photograph, irrespective of the larger societal code and it is not coded in any way. The 'connotation' of what is said or shown (second order), is the additional meaning attached by the viewer or by the researcher to the text. This may arise from culture or experience and expressed in CMM (Cronen & Pearce, 1985)

What we see in the picture or the text, what is 'denoted', is the literal content of the photograph or text. It is the "literal" denotation, the recognition of identifiable object in the photograph, irrespective of the larger societal code and it is not coded in any way. The 'connotation' of what is said or shown (second order), is the additional meaning attached by the viewer or by the researcher to the text. This may arise from culture or experience and expressed in CMM (Cronen & Pearce, 1985)

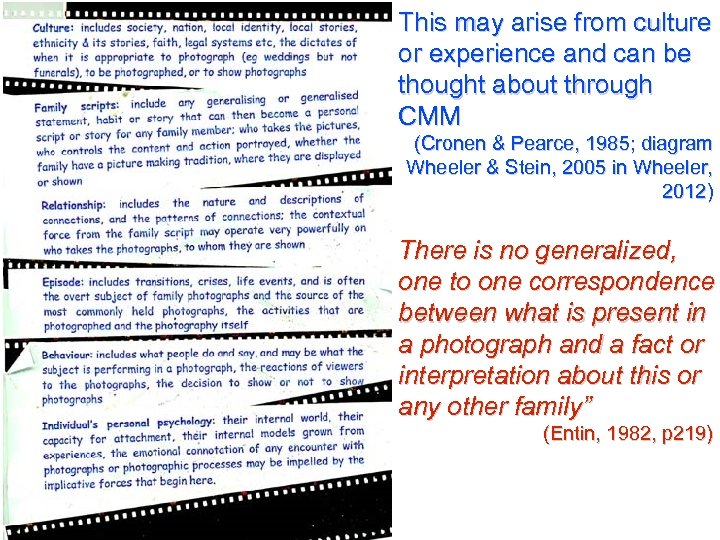

This may arise from culture or experience and can be thought about through CMM (Cronen & Pearce, 1985; diagram Wheeler & Stein, 2005 in Wheeler, 2012) There is no generalized, one to one correspondence between what is present in a photograph and a fact or interpretation about this or any other family” (Entin, 1982, p 219)

This may arise from culture or experience and can be thought about through CMM (Cronen & Pearce, 1985; diagram Wheeler & Stein, 2005 in Wheeler, 2012) There is no generalized, one to one correspondence between what is present in a photograph and a fact or interpretation about this or any other family” (Entin, 1982, p 219)

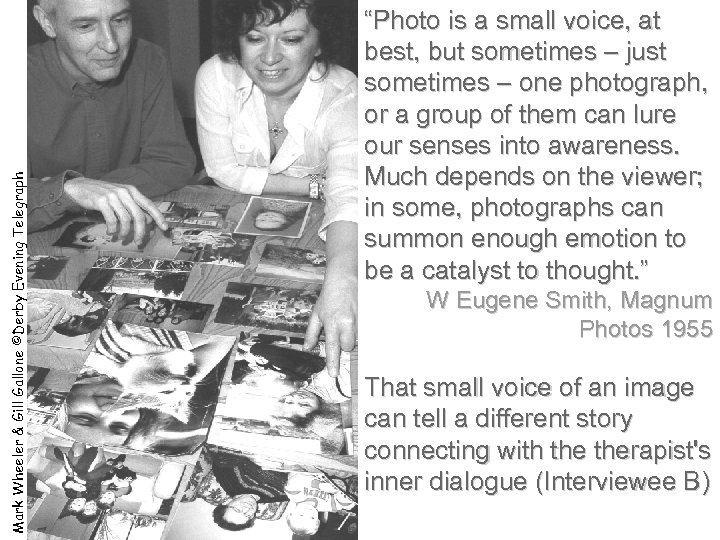

Mark Wheeler & Gill Gallone ©Derby Evening Telegraph “Photo is a small voice, at best, but sometimes – just sometimes – one photograph, or a group of them can lure our senses into awareness. Much depends on the viewer; in some, photographs can summon enough emotion to be a catalyst to thought. ” W Eugene Smith, Magnum Photos 1955 That small voice of an image can tell a different story connecting with therapist's inner dialogue (Interviewee B)

Mark Wheeler & Gill Gallone ©Derby Evening Telegraph “Photo is a small voice, at best, but sometimes – just sometimes – one photograph, or a group of them can lure our senses into awareness. Much depends on the viewer; in some, photographs can summon enough emotion to be a catalyst to thought. ” W Eugene Smith, Magnum Photos 1955 That small voice of an image can tell a different story connecting with therapist's inner dialogue (Interviewee B)

De Bernart, author of the most recent result in the literature review, cites James Hillman's (1997) idea that primarily each life is a continuum of images (de Bernart, 2013, p 122). “The verbal channel is too saturated, and because of this, one should use the non-verbal channel as it is less controlled by patients and can allow us to use the non-verbal image of the family” (de Bernart, 2013, p 122).

De Bernart, author of the most recent result in the literature review, cites James Hillman's (1997) idea that primarily each life is a continuum of images (de Bernart, 2013, p 122). “The verbal channel is too saturated, and because of this, one should use the non-verbal channel as it is less controlled by patients and can allow us to use the non-verbal image of the family” (de Bernart, 2013, p 122).

The researcher noticed a difference in emphasis between the current practice of the interviewees and the older literature. The development of understanding photographic meaning has evolved in parallel with family therapy practice in the period since then. The interviewees offered more postmodern dialogical, social constructionist and narrative accounts which reflect progress in family therapy approaches with language over the same period.

The researcher noticed a difference in emphasis between the current practice of the interviewees and the older literature. The development of understanding photographic meaning has evolved in parallel with family therapy practice in the period since then. The interviewees offered more postmodern dialogical, social constructionist and narrative accounts which reflect progress in family therapy approaches with language over the same period.

This research intended to establish whether contemporary practice by family therapists, in the researcher's CAMHS agency, are using photographs in their practice. If these family therapist are using photographs, how do they find this helpful? “If I saw 20 families, maybe only 3 of them, I had used photographs, but the 3 that I did, seem quite significant” Interviewee A This comment neatly encapsulates how family therapists are sometimes using photographs with those families who might find it helpful. Please ask questions or offer comments or share your practice

This research intended to establish whether contemporary practice by family therapists, in the researcher's CAMHS agency, are using photographs in their practice. If these family therapist are using photographs, how do they find this helpful? “If I saw 20 families, maybe only 3 of them, I had used photographs, but the 3 that I did, seem quite significant” Interviewee A This comment neatly encapsulates how family therapists are sometimes using photographs with those families who might find it helpful. Please ask questions or offer comments or share your practice

All images used under Copyright fair use (2015) Copyright Fair Use and How it Works for Online Images. available at http: //www. socialmediaexaminer. com/copyright-fair-use-and-how-it-works-for-online-images/ accessed 15 -01 -15 at 15: 00 Anderson, H (2007) Therapist and the Postmodern Therapy System: A Way of Being with Others. 32 nd Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice Conference, Glasgow, Scotland, October 5, 2007 References Anderson, C. M. & Malloy, E. S. (1976) Family Photographs: in Treatment and Training. Family Process p 259 -264 Barthes, Roland (1977): Image-Music-Text. London: Fontana Barthes, R (2000) Camera Lucida. Trans: Richard Howard from 1980 Editions de Seuil. London: Vintage Books. Benjamen, W ([1936] 999) The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. In Walter Benjamen (1999) Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Tr. Harry Zorn. London: Pimlico Berman, L (1993) 'Beyond the Smile': The therapeutic use of the photograph. London: Routledge Bertrando, 2007 The Dialogical Therapist. London: Karnac Boscolo, L. & Bertrando, P. (1992) The Reflexive Loop of Past, Present, and Future in Systemic Therapy and Consultation. Family Process, Vol. 31, June 1992 Burgin, Victor (Ed. ) (1982): Thinking Photography. London: Macmillan Burnham, J. (2012) ‘Developments in Social GRRRAAACCEEESSS: Visible-Invisible and Voiced-Unvoiced’, In Inga-Britt Krause (Ed. 2012) Culture and Reflexivity in Systemic Psychotherapy: Mutual Perspectives, London: Karnac, p. 139 -160 Coblentz, A. L. (1964) Use of photographs in a Family mental health Clinic. The American Journal of psychiatry. December 1964, p 601 -802

All images used under Copyright fair use (2015) Copyright Fair Use and How it Works for Online Images. available at http: //www. socialmediaexaminer. com/copyright-fair-use-and-how-it-works-for-online-images/ accessed 15 -01 -15 at 15: 00 Anderson, H (2007) Therapist and the Postmodern Therapy System: A Way of Being with Others. 32 nd Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice Conference, Glasgow, Scotland, October 5, 2007 References Anderson, C. M. & Malloy, E. S. (1976) Family Photographs: in Treatment and Training. Family Process p 259 -264 Barthes, Roland (1977): Image-Music-Text. London: Fontana Barthes, R (2000) Camera Lucida. Trans: Richard Howard from 1980 Editions de Seuil. London: Vintage Books. Benjamen, W ([1936] 999) The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. In Walter Benjamen (1999) Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Tr. Harry Zorn. London: Pimlico Berman, L (1993) 'Beyond the Smile': The therapeutic use of the photograph. London: Routledge Bertrando, 2007 The Dialogical Therapist. London: Karnac Boscolo, L. & Bertrando, P. (1992) The Reflexive Loop of Past, Present, and Future in Systemic Therapy and Consultation. Family Process, Vol. 31, June 1992 Burgin, Victor (Ed. ) (1982): Thinking Photography. London: Macmillan Burnham, J. (2012) ‘Developments in Social GRRRAAACCEEESSS: Visible-Invisible and Voiced-Unvoiced’, In Inga-Britt Krause (Ed. 2012) Culture and Reflexivity in Systemic Psychotherapy: Mutual Perspectives, London: Karnac, p. 139 -160 Coblentz, A. L. (1964) Use of photographs in a Family mental health Clinic. The American Journal of psychiatry. December 1964, p 601 -802

Cook, J. N. & Poulson, S. S. , (2011) Utilizing Photographs with the Genogram: A technique for enhancing couple therapy. Journal of Systemic Therapy. Vol 30(1), March 2011, p. 14 -23 Cronen & Pearce 1985 Dallos, R. & Vetere, A. (2005) Researching Psychotherapy and Counselling. Maidenhead: OU Press Dallos, R & Draper, R (2010) An Introduction to family Therapy: systemic theory and practice. Maidenhead: OU Press. 3 rd edition. De Bernart, R (2013) The photographic Genogram and family therapy. In Del Loewenthal (2013) Phototherapy and Therapeutic Photography in a Digital Age. London: Routledge Entin, A. D. (1980). Phototherapy: Family albums & multigenerational portraits. Camera Lucida 1: 2, 39 -51. Entin, A. D. (1981). The use of photographs and family albums in family therapy. In: A. Gurman, (Ed. ), Questions And Answers In The Practice Of Family Therapy (p. 421 -425). New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. Entin, A. D (1982). Family icons: Photographs in family therapy. In: E. Abt & I. R. Stuart (Eds. ), The Newer Therapies: A Sourcebook (p. 207 -227). New York: Van. Nostrand. p. 207 -227 Entin, A. D. (1983). The family album as icon: Photographs in family psychotherapy. In: D. A. Krauss & J. L. Fryrear (Eds. ), Phototherapy In Mental Health (p. 117 -134). Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas. Entin, A. D. (1985 a). Phototherapy: The uses of photography in psychotherapy. The Independent Practitioner, 5: 1, 15 -16. Entin, A. D. (1985 b) Photo Therapy: Family Albums and Multigenerational Portraits. Camera Lucida. Vol 1(2) Win 1980, p. 51 Entin, A D. (1986) The pet focused family: A systemic theory perspective. Psychotherapy in Private Practice, Vol 4(2). Sum 1986 p. 13 -17

Cook, J. N. & Poulson, S. S. , (2011) Utilizing Photographs with the Genogram: A technique for enhancing couple therapy. Journal of Systemic Therapy. Vol 30(1), March 2011, p. 14 -23 Cronen & Pearce 1985 Dallos, R. & Vetere, A. (2005) Researching Psychotherapy and Counselling. Maidenhead: OU Press Dallos, R & Draper, R (2010) An Introduction to family Therapy: systemic theory and practice. Maidenhead: OU Press. 3 rd edition. De Bernart, R (2013) The photographic Genogram and family therapy. In Del Loewenthal (2013) Phototherapy and Therapeutic Photography in a Digital Age. London: Routledge Entin, A. D. (1980). Phototherapy: Family albums & multigenerational portraits. Camera Lucida 1: 2, 39 -51. Entin, A. D. (1981). The use of photographs and family albums in family therapy. In: A. Gurman, (Ed. ), Questions And Answers In The Practice Of Family Therapy (p. 421 -425). New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. Entin, A. D (1982). Family icons: Photographs in family therapy. In: E. Abt & I. R. Stuart (Eds. ), The Newer Therapies: A Sourcebook (p. 207 -227). New York: Van. Nostrand. p. 207 -227 Entin, A. D. (1983). The family album as icon: Photographs in family psychotherapy. In: D. A. Krauss & J. L. Fryrear (Eds. ), Phototherapy In Mental Health (p. 117 -134). Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas. Entin, A. D. (1985 a). Phototherapy: The uses of photography in psychotherapy. The Independent Practitioner, 5: 1, 15 -16. Entin, A. D. (1985 b) Photo Therapy: Family Albums and Multigenerational Portraits. Camera Lucida. Vol 1(2) Win 1980, p. 51 Entin, A D. (1986) The pet focused family: A systemic theory perspective. Psychotherapy in Private Practice, Vol 4(2). Sum 1986 p. 13 -17

Fryrear, J. L. & Corbit, I. E. (1982) Photo-Art-Therapy: A Jungian Perspective. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, publisher Hirsch, M (2012) Family Frames: photography, narrative and postmemory. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press. Holland, P. , Spence, J. , & Watnery, S. (1986) Photography/Politics: Two, London, Comedia/Photography Workshop, 1986 Jenkins, H. (2006) Inside out, or outside in: meeting with couples. Journal of Family Therapy. 28: 113 -135 Jenkins, H (2008) Making meanings: A family's multiple constructs of time. Terapia Systemica (Systems Therapy). May issue p. 24 -47 Kaslow, F. W. , & Friedman, J. (1977). Utilization of family photos and movies in family therapy. Journal of Marriage and Family Counseling, 3: 1, 19 -25 Kozloff, M (1979) Photography & Fascination. Danbury NH: Addison House Leoewenthal, D (2012) Phototherapy in a digital age. London: Routledge Mc. Namee, S. & Gergen, K. J. (eds), (1992), Therapy as Social Construction. London: Sage. Ruben, A. G. (1978) The Family Picture. Journal of Marriage and family Counselling. July 1976 Seabrook, J (1991) My Life is in that box. In Jo Spence & Patricia Holland: Family Snaps: The Meanings of Domestic Photography. London: Virago Smith, J. A. , Flowers, P. & Larkin, M. (2009) Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London: Sage Sontag, S (1977) On Photography. NY: Delta

Fryrear, J. L. & Corbit, I. E. (1982) Photo-Art-Therapy: A Jungian Perspective. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, publisher Hirsch, M (2012) Family Frames: photography, narrative and postmemory. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press. Holland, P. , Spence, J. , & Watnery, S. (1986) Photography/Politics: Two, London, Comedia/Photography Workshop, 1986 Jenkins, H. (2006) Inside out, or outside in: meeting with couples. Journal of Family Therapy. 28: 113 -135 Jenkins, H (2008) Making meanings: A family's multiple constructs of time. Terapia Systemica (Systems Therapy). May issue p. 24 -47 Kaslow, F. W. , & Friedman, J. (1977). Utilization of family photos and movies in family therapy. Journal of Marriage and Family Counseling, 3: 1, 19 -25 Kozloff, M (1979) Photography & Fascination. Danbury NH: Addison House Leoewenthal, D (2012) Phototherapy in a digital age. London: Routledge Mc. Namee, S. & Gergen, K. J. (eds), (1992), Therapy as Social Construction. London: Sage. Ruben, A. G. (1978) The Family Picture. Journal of Marriage and family Counselling. July 1976 Seabrook, J (1991) My Life is in that box. In Jo Spence & Patricia Holland: Family Snaps: The Meanings of Domestic Photography. London: Virago Smith, J. A. , Flowers, P. & Larkin, M. (2009) Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London: Sage Sontag, S (1977) On Photography. NY: Delta

Spence, 1984, 1986 b Spence, Jo. (1984). Public images/private functions; Reflections on High Street practice. Ten-8, 13, 7 -17 Spence, J. (1986). Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political Personal and Photographic Autobiography. London: Camden Press Spence, J. & Holland, P. (2000) Family Snaps: The meanings of Domestic Photography. London: Virago Teller, Alan. (1979). Some questions for photo therapy. Phototherapy, 2: 2, 12 -13 The Archers (2015) [radio] BBC Radio 4. March 15 at 10: 20 AM Webster, J. & Huffington, C (1993) Creativity and the Family: Using Non-Verbal Approaches. Context. 17, Winter 1993/4 Weiser, Judy. (1986 a). Ethical considerations in Photo. Therapy training and practice. Phototherapy, 5: 1, 12 -17. Weiser, Judy. (1986 b). Ethical considerations in Photo. Therapy training and practice. Video-Informationen, 9: 2, 5 -10 Weiser, J. (1993), Photo. Therapy Techniques, Exploring the Secrets of Personal Snapshots and Family Albums. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Weiser, J (1999) Photo. Therapy Techniques: Exploring the Secrets of personal Snapshots and family Albums. 2 nd edition. Vancouver: Photo. Therapy Centre Weiser, J. (2014) personal correspondence Wheeler, M. & Stein, N. (2004) Review of Judy Weiser's 4 day phototherapy training. Available at The Phototherapy Centre.

Spence, 1984, 1986 b Spence, Jo. (1984). Public images/private functions; Reflections on High Street practice. Ten-8, 13, 7 -17 Spence, J. (1986). Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political Personal and Photographic Autobiography. London: Camden Press Spence, J. & Holland, P. (2000) Family Snaps: The meanings of Domestic Photography. London: Virago Teller, Alan. (1979). Some questions for photo therapy. Phototherapy, 2: 2, 12 -13 The Archers (2015) [radio] BBC Radio 4. March 15 at 10: 20 AM Webster, J. & Huffington, C (1993) Creativity and the Family: Using Non-Verbal Approaches. Context. 17, Winter 1993/4 Weiser, Judy. (1986 a). Ethical considerations in Photo. Therapy training and practice. Phototherapy, 5: 1, 12 -17. Weiser, Judy. (1986 b). Ethical considerations in Photo. Therapy training and practice. Video-Informationen, 9: 2, 5 -10 Weiser, J. (1993), Photo. Therapy Techniques, Exploring the Secrets of Personal Snapshots and Family Albums. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Weiser, J (1999) Photo. Therapy Techniques: Exploring the Secrets of personal Snapshots and family Albums. 2 nd edition. Vancouver: Photo. Therapy Centre Weiser, J. (2014) personal correspondence Wheeler, M. & Stein, N. (2004) Review of Judy Weiser's 4 day phototherapy training. Available at The Phototherapy Centre.