973db005c787163a1cfa403a5f843fe7.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 102

MANAGERIAL ECONOMICS: THEORY, APPLICATIONS, AND CASES W. Bruce Allen | Keith Weigelt | Neil Doherty | Edwin Mansfield Learning Unit 5 Sophisticated Pricing Strategies

MOTIVATION FOR PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Figure 8. 1: Single-Price Monopolist Profit-Maximizing Outcome • Single-price monopoly equilibrium fails to capture all consumer surplus and also results in a dead-weight loss. • Price discrimination provides a strategic mechanism for capturing some, or all, of this lost surplus.

PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Price discrimination: When the same product is sold at more than one price • Differences in price among similar products are not evidence of price discrimination unless these price differences are not based on cost differences.

PRICE DISCRIMINATION • First-Degree Price Discrimination • All customers are charged a price equal to their reservation price. • The firm captures 100 percent of the consumer surplus. • Equilibrium output and marginal cost are the same as under perfect competition. • There is no dead-weight loss. • Requires that firms have a relatively small number of buyers and that they are able to estimate buyers' reservations prices • May be operationalized by means of a two-part tariff

PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Second-Degree Price Discrimination • Most commonly used by utilities (gas, electric, water, etc. ). • Different prices are charged for different quantities of a good. • Figure 8. 2: Second-Degree Price Discrimination • Third-Degree Price Discrimination • Most common form of price discrimination

PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Conditions • Demand must be heterogeneous; that is, different demand segments must have different price elasticities of demand. • Managers must be able to identify and segregate the different segments. • Markets must be successfully sealed so that customers in one segment cannot transfer the goods to another segment.

PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Example: Students • Limited income makes students more responsive to price differences. • Students' price elasticity of demand is thus likely to be more elastic than that of other segments. • Students can be readily identified by their student IDs, aiding in segmentation.

PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Other conditions • Segments must differ significantly in their price elasticities. • Managers must be able to identify and target the segments at moderate cost. • Buyers must be unable to transfer a product from one segment to another. • These two conditions are referred to as the ability to "segment and seal" the market.

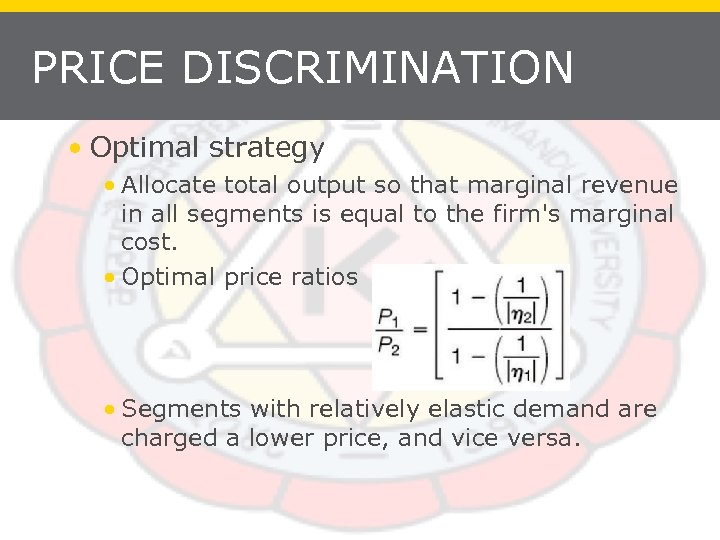

PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Optimal strategy • Allocate total output so that marginal revenue in all segments is equal to the firm's marginal cost. • Optimal price ratios • Segments with relatively elastic demand are charged a lower price, and vice versa.

USING COUPONS AND REBATES FOR PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Coupons and rebates are used to segment a market. • People who use coupons or send in rebates are likely to have more elastic demand than those who do not. • Coupons and rebates lead people to selfselect their market segment.

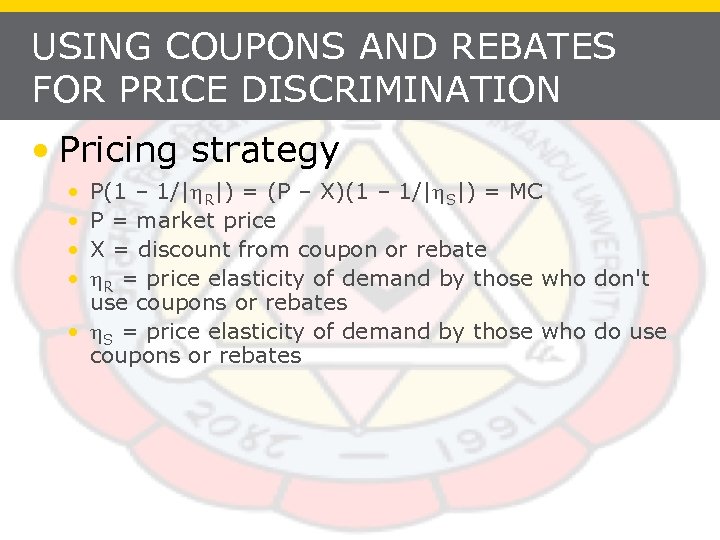

USING COUPONS AND REBATES FOR PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Pricing strategy • • P(1 – 1/| R|) = (P – X)(1 – 1/| S|) = MC P = market price X = discount from coupon or rebate R = price elasticity of demand by those who don't use coupons or rebates • S = price elasticity of demand by those who do use coupons or rebates

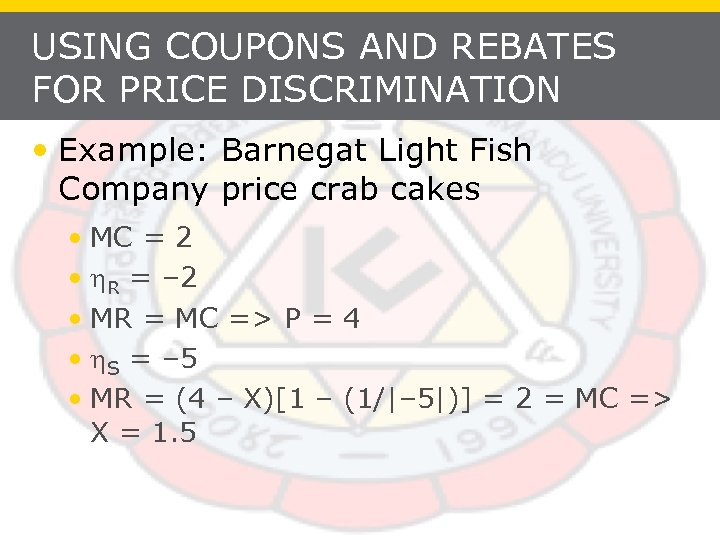

USING COUPONS AND REBATES FOR PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Example: Barnegat Light Fish Company price crab cakes • MC = 2 • R = – 2 • MR = MC => P = 4 • S = – 5 • MR = (4 – X)[1 – (1/|– 5|)] = 2 = MC => X = 1. 5

PEAK LOAD PRICING • Issues in pricing strategy • The demand for some goods is time sensitive or seasonal. • Plant capacity is constant.

PEAK LOAD PRICING • Issues in pricing strategy (Continued) • Examples • • Electricity generation Roadways Resort and hotel rooms Intertemporal pricing of intellectual property—early release charges peak pricing and later release charges trough pricing—books released first as hard-bound with higher price followed by paperback at a lower price— leaders and followers in markets

PEAK LOAD PRICING • Strategic response • During peak time periods, when demand is high, managers should charge a higher price (PP). • During trough time periods, when demand is low, managers should charge a lower price (PT). • Marginal cost often follows a cyclical pattern in which MC is high during peak periods and low during trough time periods. • Firms should equate marginal cost and marginal revenue separately in the two time periods to determine the appropriate prices.

TWO-PART TARIFFS • Two-part tariff • When managers set prices so that consumers pay an entry fee and then a use fee for each unit of the product they consume

TWO-PART TARIFFS • Examples • Clubs (golf, health, discount, etc. ) that charge a membership fee and a per use fee • Wireless phone plans that charge a fixed fee and then additional fees per minute • Personal seat licenses (PSL) for sports stadiums —a fixed cost that gives the purchaser the right to buy tickets to games.

TWO-PART TARIFFS • Strategy when all demanders are the same • Model • Assume that all consumers have the same preferences, defined by the demand curve P = a – b. Q. • Assume that the firm's marginal cost is constant. • Entry fee is equal to consumer surplus. • Use fee is equal to marginal cost. • Total revenue is the same as under first-degree price discrimination.

TWO-PART TARIFFS • A Two-Part Tariff with a Rising Marginal Cost • Strategy is the same as when marginal cost is constant. • Variable cost profit is positive when marginal cost has a positive slope. • Figure 8. 6: Optimal Two-Part Tariff When Marginal Cost Is Rising • A Two-Part Tariff with Different Demand Curves • Model • Market consists of strong demanders and weak demanders

TWO-PART TARIFFS • Pricing strategies • When strong demand is much stronger than weak demand: Set use fee equal to marginal cost and entry fee equal to the strong demanders' consumer surplus. Weak demanders will be excluded from the market. • When strong demand is not much stronger than weak demand: Set use fee equal to marginal cost and entry fee equal to the weak demanders' consumer surplus. Weak demanders will not be excluded from the market.

TWO-PART TARIFFS • Pricing strategies (Continued) • When strong demand is not much stronger than weak demand: Set use above marginal cost at a price that maximizes variable cost profit and entry fee equal to the weak demanders' consumer surplus. Weak demanders will not be excluded from the market. • Optimal strategy when strong demand is not much stronger than weak demand is found by comparing total average cost profit from the two strategies.

DEFINITIONS • Simple bundling: When managers offer several products or services as one package so consumers do not have an option to purchase package components separately • Example: Inclusion of a service contract with a product

DEFINITIONS • Mixed bundling: Allows consumers to purchase package components either as a single unit or separately • The bundle price is generally less than the sum of the prices of the individual components. • Examples: Season tickets to sporting events or value meals at Mc. Donald’s

DEFINITIONS • Negative correlation: When some customers have higher reservation prices for one item in the bundle but lower reservation prices for another item in the bundle, whereas another group of customers has the reverse preferences • Managers form bundles so as to increase profit by creating negative correlations across consumers.

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Advantages of bundling • Bundling can increase the seller’s profit as customers have varied tastes. • Bundling can emulate first-degree price discrimination when it is not otherwise possible because individual reservation prices cannot be determined or laws prohibit price discrimination. • Bundling does not require knowledge of individual consumers’ reservation prices, but only the distribution of consumers’ reservation prices.

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Strategies • Assumption: Goods are independent, so the value of a bundle is equal to the sum of the reservation prices of the goods in the bundle. • Separate pricing: Goods are not bundled. • Prices are set equal to profit-maximizing monopoly prices.

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Strategies (Continued) • Pure bundling • Bundle price is set to maximize profit. • Mixed bundling • Bundle price and individual good prices are set to maximize profit. • Optimal strategy is that which maximizes profit

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example Figures • Notation • ri = Reservation price of good i • pi# = Price charged for good i • PB# = Price of bundle

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example Figures (Continued) • Figure 9. 1: Price Separately • If r 1 < p 1# and neither good. • If r 1 > p 1# and only good 1. • If r 1 < p 1# and only good 2. • If r 1 > p 1# and both goods. r 2 < p 2#, then consumer buys r 2 > p 2#, then consumer buys

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Figure 9. 2: Pure Bundling • If (r 1 + r 2) < PB#, then consumer does not buy the bundle. • If (r 1 + r 2) > PB#, then consumer buys the bundle. • Figure 9. 3: Mixed Bundling • Buy neither good nor bundle: (r 1 + r 2) < PB#, r 1 < p 1#, and r 2 < p 2# • Buy bundle: (r 1 + r 2) > PB# • Buy good 1 only: r 1 > p 1#, r 2 < p 2#, and r 2 < (PB# – p 1#) • Buy good 2 only: r 2 > p 2#, r 1 < p 1#, and r 1 < (PB# – p 2#)

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example 1 • Assumptions • Perfect negative correlation among consumer reservation prices (Figure 9. 4) • No variation in total bundle valuation; all value the bundle at $100. • Unit cost of production for each good = $1. • Table 9. 1: Consumer Reservation Prices • Table 9. 2: Optimal Separate Prices for Good 1 and Good 2: Profit = $264

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example 1 • Table 9. 3: Optimal Pure Bundle Price for Consumers A, B, C, and D: Profit = $392 • Table 9. 4: Optimal Mixed Bundle Prices: Profit = $392 • Table 9. 5: Optimal Mixed Bundle Prices When Consumers Buy Bundle and at Least One of the Separately Priced Goods: Profit = $373. 98

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Definitions • Credibility of the bundle: When managers correctly anticipate which customers will purchase the bundle or the goods separately • Extraction: When the manager extracts the entire consumer surplus from each customer • Exclusion: When the manager does not sell a good to a customer who values the good at less than the cost of producing it • Inclusion: When a manager sells a good to a consumer who values the good at greater than the seller’s cost of producing the good

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Definitions • Extraction, exclusion, and inclusion are all satisfied by perfect price discrimination. • Pricing separately will satisfy exclusion but will not result in complete extraction or inclusion.

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Definitions (Continued) • Pure bundling can result in complete extraction, but if consumer reservation prices do not have a perfect negative correlation, extraction will be less than complete. It is also possible for pure bundling to fail to attain full inclusion and exclusion. • The profit from mixed bundling is always equal to or better than that of pricing separately or pure bundling.

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example 2 • Assumptions • Perfect negative correlation among consumer reservation prices • No variation in total bundle valuation; all value the bundle at $100. • Unit cost of production for each good = $11.

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example 2 (Continued) • Table 9. 6: Optimal Separate Prices for Good 1 and Good 2: Profit = $204 • Table 9. 7: Optimal Pure Bundle Price for Consumers A, B, C, and D: Profit = $312 • Table 9. 8: Optimal Mixed Bundle Prices: Profit = $312 • Table 9. 9: Optimal Mixed Bundle Prices When Consumers Buy Bundle and at Least One of the Separately Priced Goods: Profit = $313. 98

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example 3 • Assumptions • Perfect negative correlation among consumer reservation prices • No variation in total bundle valuation; all value the bundle at $100. • Unit cost of production for each good = $55.

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example 3 (Continued) • Table 9. 10: Optimal Separate Prices for Good 1 and Good 2: Profit = $70 • Table 9. 11: Optimal Pure Bundle Price for Consumers A, B, C, and D: Profit = $0 • Table 9. 12: Optimal Mixed Bundle Prices at Any Pure Bundle Price over $100 (So No Bundle Is Purchased): Profit = $70

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Conclusions from Examples 1– 3: When reservation prices are negatively correlated • When production cost is low, pure bundling will extract all consumer surplus. • When production cost rises, mixed bundling is best. • When production cost rises further, separate pricing is best.

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Conclusions from Examples 1– 3: When reservation prices are negatively correlated (Continued) • The optimal separate prices are always equal to consumers' reservation prices. • The optimal pure bundle price is always equal to the sum of consumers' reservation prices. • The optimal mixed bundle prices are not necessarily equal to reservation prices or their sum.

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example 4 • Assumptions • Distribution of reservation prices is uniform over the range $0 to $100 for each good. • Correlation is zero. • There are 10, 000 customers. • Production cost is zero. • Figure 9. 5: Optimal Separate Prices in the Case of Uniformly Distributed Consumer Reservation Prices: Profit = $500, 000

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example 4 • Figure 9. 6: Optimal Pure Bundle Price in the Case of Uniformly Distributed Reservation Prices: Profit = $544, 331. 10 • Figure 9. 7: Optimal Mixed Bundle Pricing in the Case of Uniformly Distributed Reservation Prices: Profit = $549, 201

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example 5 • Assumptions • Quantity discounting is a form of mixed bundling. • Unit cost of production for each good = $1. • Table 9. 13: Reservation Prices for the First and Second Units of a Good by Consumers A and B • Table 9. 14: Optimal Separate Prices for the Good: Profit = $6

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example 5 (Continued) • Table 9. 15: Optimal Pure Bundle Price for Two Units of the Good: Profit = $7 • Table 9. 16: Optimal Mixed Bundling Prices for the Case of a Single Good: Profit = $7. 99

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example 6 • Assumptions • Three consumers with negatively correlated reservation prices • Each consumer wants no more than one unit of each of two goods. • Cost of production is $4. • Table 9. 17: Consumer Reservation Prices for Good X and Good Y (in Dollars) • Table 9. 18: Best Separate Price Strategy: Profit = $16. 00

THE MECHANICS OF BUNDLING • Example (Continued) • Table 9. 19: Best Pure Bundling Strategy: Profit = $15. 99 • Table 9. 20: Best Mixed Bundling Strategy: Profit = $17. 97

WHEN TO UNBUNDLE • Example • Assumptions • Three consumers with negatively correlated reservation prices • Each consumer wants no more than one unit of each of two goods.

WHEN TO UNBUNDLE • Example (Continued) • Table 9. 21: The Reservation Prices for Consumers A, B, and C for Good X, Good Y, and a Bundle of Good X and Good Y • Figure 9. 8: Depiction of Bundling Problem in Table 9. 21 • Pure bundling gives the lowest profit. • Mixed bundling gives the highest profit.

BUNDLING AS A PREEMPTIVE ENTRY STRATEGY • Bundling can be used to deter entry. • Assumptions • The bundle offered by Alpha Company is made up of W and S, has a cost of 4, and will be priced at $X. • The Beta Company is developing C that has a cost of 2 and is a close substitute for W.

BUNDLING AS A PREEMPTIVE ENTRY STRATEGY • Assumptions (Continued) • The Gamma Company is developing N that has a cost of 2 and is a close substitute for S. • Only Alpha has the assets to produce a bundle. • Alpha's entry cost to the market with a bundle is 30. Entry cost for each product individually is 15. • Beta's entry cost to the market is 17. • Alpha's entry cost to the market is 17. • Demand for the goods are perfectly negatively correlated.

BUNDLING AS A PREEMPTIVE ENTRY STRATEGY • Example • Table 9. 22: the Reservation Prices for Consumers A, B, and C for Good W or C, Good S or N, and a Bundle of Good W and Good S or a Bundle of Good C and Good N

TYING AT IBM, XEROX, AND MICROSOFT • Tying: A pricing technique in which managers sell a product that needs a complementary product • This is a form of bundling that applies to complementary products. • Tying requires market power. • Tying may be used to protect a monopoly. • Tying may be used to ensure that a firm's product works properly and its brand name is protected. • Examples: Maintenance contracts and franchise requirements

TYING AT IBM, XEROX, AND MICROSOFT • Examples • Xerox required customers who leased copy machines to use Xerox paper. • IBM required customers who leased computers to use IBM punch cards. • Microsoft forced customers to use Internet Explorer with its operating system in order to exclude Netscape and protect its monopoly.

TYING AT IBM, XEROX, AND MICROSOFT • Notice to wholesale liquor dealers from the Department of the Treasury (2003) prohibited the following tying practices: • Requiring a retailer to purchase a regular case of distilled spirits to be able to purchase the spirits in a special holiday container. • Requiring a retailer to purchase 10 cases of a winery’s Chardonnay with 10 cases of the winery’s Merlot. • Requiring a retailer to purchase a two-bottle package of a winery’s Merlot and Chardonnay to purchase cases of the winery’s Merlot.

TRANSFER PRICING • Transfer price: Payment that simulates a market where no formal market exists. • Refers to intrafirm pricing among wholly owned subsidiaries or divisions. • The purpose of transfer prices: • Encourage profit-maximizing or costminimizing behavior by providing an incentive. • Measure the performance of semi-autonomous divisions.

TRANSFER PRICING • Notation (MRD – MCD)MPU = MCU • In the absence of an external market, the optimal transfer price is the marginal cost of the upstream product (MCU) when the optimal quantity (QU) is produced.

TRANSFER PRICING: A PERFECTLY COMPETITIVE MARKET FOR THE UPSTEAM PRODUCT • The optimal transfer price is the competitive market price. • Example: Figure 9. 10: Determination of the Transfer Price, Given a Perfectly Competitive External Market for the Transferred Product

THE GLOBAL USE OF TRANSFER PRICING • For international transfers, the most common methods of determining transfer prices are market-based transfer prices and full productions costs plus a markup. • A comparison with the results of an earlier study indicates the market-based transfer prices are increasingly being used.

THE GLOBAL USE OF TRANSFER PRICING • Managers can use transfer pricing to shift profits between divisions to minimize tax liability. • Increase profit in low-tax countries and decrease profit in high-tax countries

THE GLOBAL USE OF TRANSFER PRICING • Notation and implication • Assume there is no external market for the upstream product and that all profits are expressed in the same currency. • = Tax rate in a downstream country • = Tax rate in an upstream country, where >

THE GLOBAL USE OF TRANSFER PRICING • Notation and implication (Continued) • After-tax profit in the downstream country = (1 – )(TRD – TCD – PUQU) • After-tax profit in the upstream country = (1 – )(PUQU – TCU) • Total after-tax profit = (1 – )(TRD – TCD) – (1 – )(TCU) + ( – )(PUQU) • Increasing the transfer price (PU) will increase after-tax profit.

THE GLOBAL USE OF TRANSFER PRICING • Reasons for the importance of global transfer prices: • Increased globalization • Different level of taxation in various countries • Greater scrutiny by tax authorities • Inconsistent rules and laws in different tax jurisdictions

THE GLOBAL USE OF TRANSFER PRICING • Transfer price policies that cause the fewest problems: • Comparable uncontrolled price (arms-length price) • Cost-plus prices, using the arms-length markup • Resale price

973db005c787163a1cfa403a5f843fe7.ppt