67f536dacc83ec252a962e0bcd923678.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 57

Macroeconomics Class 3: Economic Growth (cont. )

Macroeconomics Class 3: Economic Growth (cont. )

This class: tying lose ends left from Class 2 “globalisation”, externalities and increasing returns to scale Growth under “globalisation” • where accumulation may be funded by foreign savers • The costs and the benefits of globalization (and liberalization) • The concept of an externality • Back to the slow model – evidence on convergence – impediments to convergence – growth with increasing returns to scale 2

This class: tying lose ends left from Class 2 “globalisation”, externalities and increasing returns to scale Growth under “globalisation” • where accumulation may be funded by foreign savers • The costs and the benefits of globalization (and liberalization) • The concept of an externality • Back to the slow model – evidence on convergence – impediments to convergence – growth with increasing returns to scale 2

Opening the economy to foreign savers In a Solow world: I = S • investment is funded by domestic savings In an open economy, foreign savings are an additional resource That would generate a balance-of-payments (BOP) deficit • but would accelerate convergence Hence, the convergence result is strengthened in an open economy 3

Opening the economy to foreign savers In a Solow world: I = S • investment is funded by domestic savings In an open economy, foreign savings are an additional resource That would generate a balance-of-payments (BOP) deficit • but would accelerate convergence Hence, the convergence result is strengthened in an open economy 3

Claim: a current account deficit is just the imbalance between domestic spending over GNP Start with the basic equality between uses and resources Y + IM = C + I + G + EX • (at this stage, thing of all items as if measured in terms of potatoes) Rearranging, we get: (IM – EX) = (C + I + G) – Y where • (IM – EX) ≡ CAD – Current Account Deficit – the excess of imports over exports • colloquially, balance-of-payments (BOP) deficit 4

Claim: a current account deficit is just the imbalance between domestic spending over GNP Start with the basic equality between uses and resources Y + IM = C + I + G + EX • (at this stage, thing of all items as if measured in terms of potatoes) Rearranging, we get: (IM – EX) = (C + I + G) – Y where • (IM – EX) ≡ CAD – Current Account Deficit – the excess of imports over exports • colloquially, balance-of-payments (BOP) deficit 4

Alternatively: the CAD is the imbalance between domestic savings over domestic investment Hence • CAD = (C + I + G) – Y – CAD is the excess of domestic spending over domestic production Rearranging, we get • CAD = I – [Y – (C + G) ] ≡ S, domestic savings by both government and households – hence, CAD is the excess of domestic investment over domestic savings These, however, are just accounting identities • to derive an economic explanation of the BOP • we need to substitute in behavioural functions 5

Alternatively: the CAD is the imbalance between domestic savings over domestic investment Hence • CAD = (C + I + G) – Y – CAD is the excess of domestic spending over domestic production Rearranging, we get • CAD = I – [Y – (C + G) ] ≡ S, domestic savings by both government and households – hence, CAD is the excess of domestic investment over domestic savings These, however, are just accounting identities • to derive an economic explanation of the BOP • we need to substitute in behavioural functions 5

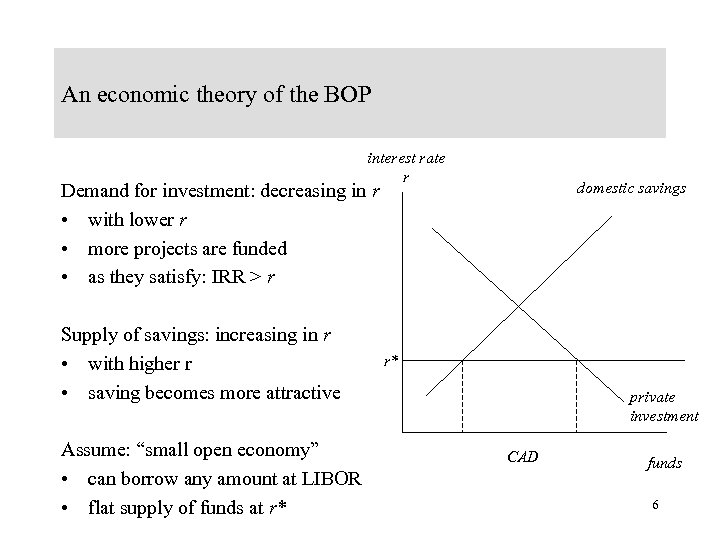

An economic theory of the BOP interest rate r domestic savings Demand for investment: decreasing in r • with lower r • more projects are funded • as they satisfy: IRR > r Supply of savings: increasing in r • with higher r • saving becomes more attractive Assume: “small open economy” • can borrow any amount at LIBOR • flat supply of funds at r* r* private investment CAD funds 6

An economic theory of the BOP interest rate r domestic savings Demand for investment: decreasing in r • with lower r • more projects are funded • as they satisfy: IRR > r Supply of savings: increasing in r • with higher r • saving becomes more attractive Assume: “small open economy” • can borrow any amount at LIBOR • flat supply of funds at r* r* private investment CAD funds 6

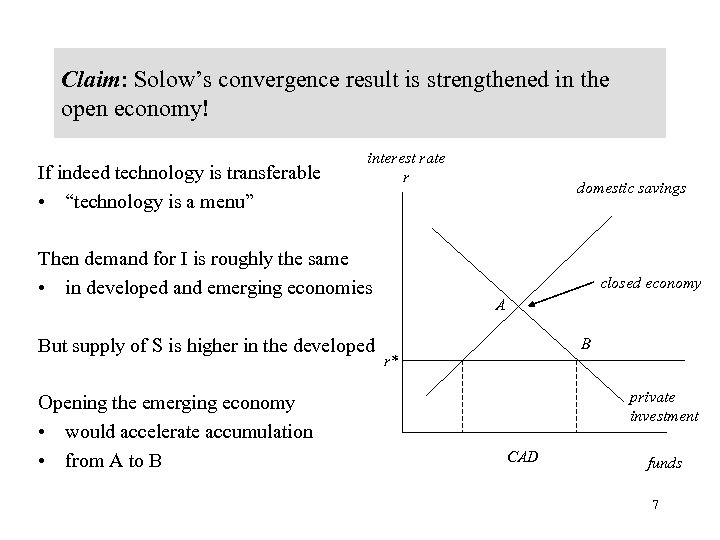

Claim: Solow’s convergence result is strengthened in the open economy! If indeed technology is transferable • “technology is a menu” interest rate r Then demand for I is roughly the same • in developed and emerging economies But supply of S is higher in the developed Opening the emerging economy • would accelerate accumulation • from A to B domestic savings closed economy A B r* private investment CAD funds 7

Claim: Solow’s convergence result is strengthened in the open economy! If indeed technology is transferable • “technology is a menu” interest rate r Then demand for I is roughly the same • in developed and emerging economies But supply of S is higher in the developed Opening the emerging economy • would accelerate accumulation • from A to B domestic savings closed economy A B r* private investment CAD funds 7

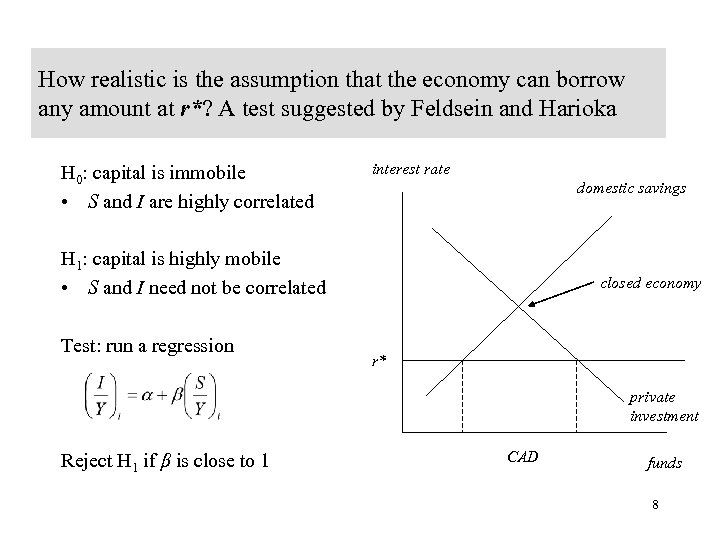

How realistic is the assumption that the economy can borrow any amount at r*? A test suggested by Feldsein and Harioka H 0: capital is immobile • S and I are highly correlated interest rate domestic savings H 1: capital is highly mobile • S and I need not be correlated Test: run a regression closed economy r* private investment Reject H 1 if β is close to 1 CAD funds 8

How realistic is the assumption that the economy can borrow any amount at r*? A test suggested by Feldsein and Harioka H 0: capital is immobile • S and I are highly correlated interest rate domestic savings H 1: capital is highly mobile • S and I need not be correlated Test: run a regression closed economy r* private investment Reject H 1 if β is close to 1 CAD funds 8

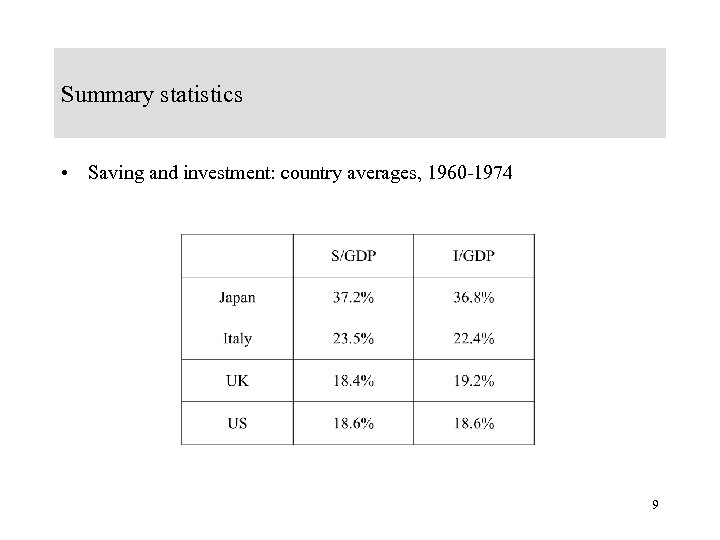

Summary statistics • Saving and investment: country averages, 1960 -1974 9

Summary statistics • Saving and investment: country averages, 1960 -1974 9

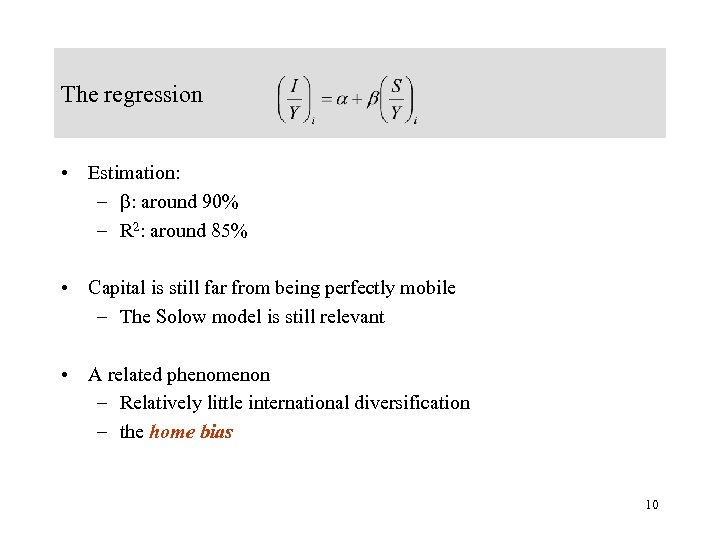

The regression • Estimation: – : around 90% – R 2: around 85% • Capital is still far from being perfectly mobile – The Solow model is still relevant • A related phenomenon – Relatively little international diversification – the home bias 10

The regression • Estimation: – : around 90% – R 2: around 85% • Capital is still far from being perfectly mobile – The Solow model is still relevant • A related phenomenon – Relatively little international diversification – the home bias 10

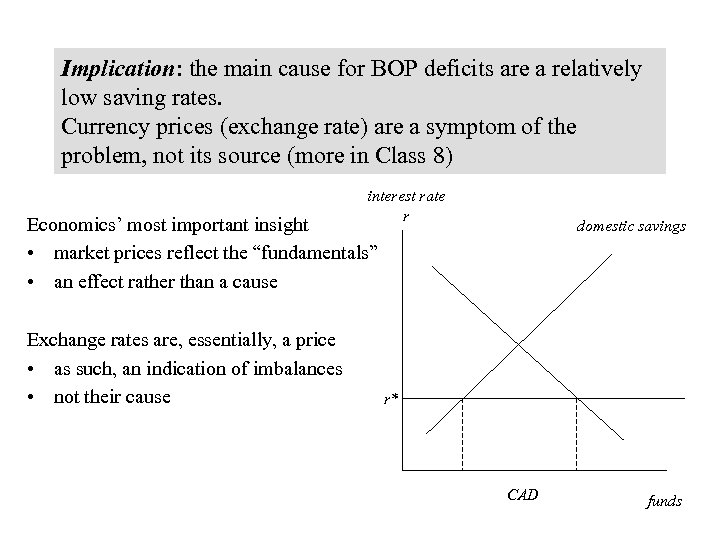

Implication: the main cause for BOP deficits are a relatively low saving rates. Currency prices (exchange rate) are a symptom of the problem, not its source (more in Class 8) interest rate r Economics’ most important insight • market prices reflect the “fundamentals” • an effect rather than a cause Exchange rates are, essentially, a price • as such, an indication of imbalances • not their cause domestic savings r* CAD funds 11

Implication: the main cause for BOP deficits are a relatively low saving rates. Currency prices (exchange rate) are a symptom of the problem, not its source (more in Class 8) interest rate r Economics’ most important insight • market prices reflect the “fundamentals” • an effect rather than a cause Exchange rates are, essentially, a price • as such, an indication of imbalances • not their cause domestic savings r* CAD funds 11

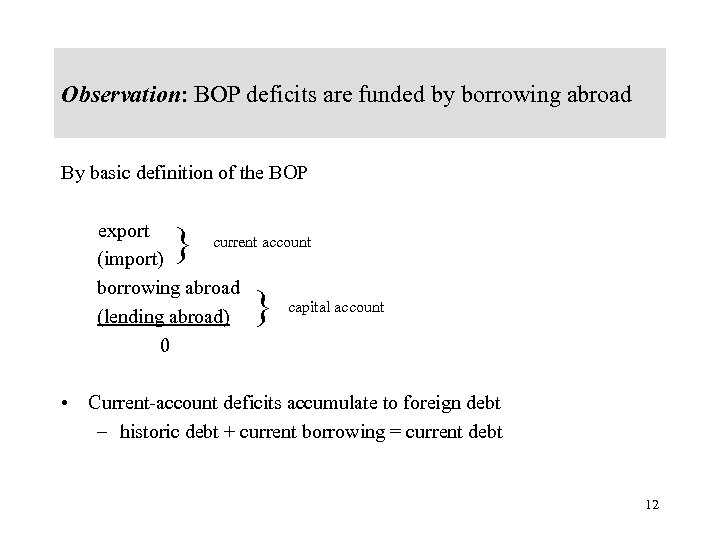

Observation: BOP deficits are funded by borrowing abroad By basic definition of the BOP export current account (import) borrowing abroad capital account (lending abroad) 0 } } • Current-account deficits accumulate to foreign debt – historic debt + current borrowing = current debt 12

Observation: BOP deficits are funded by borrowing abroad By basic definition of the BOP export current account (import) borrowing abroad capital account (lending abroad) 0 } } • Current-account deficits accumulate to foreign debt – historic debt + current borrowing = current debt 12

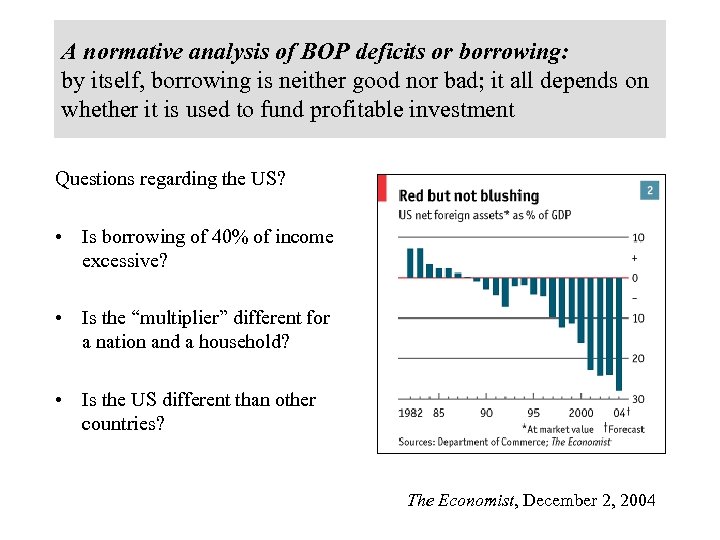

A normative analysis of BOP deficits or borrowing: by itself, borrowing is neither good nor bad; it all depends on whether it is used to fund profitable investment Questions regarding the US? • Is borrowing of 40% of income excessive? • Is the “multiplier” different for a nation and a household? • Is the US different than other countries? The Economist, December 2, 2004 13

A normative analysis of BOP deficits or borrowing: by itself, borrowing is neither good nor bad; it all depends on whether it is used to fund profitable investment Questions regarding the US? • Is borrowing of 40% of income excessive? • Is the “multiplier” different for a nation and a household? • Is the US different than other countries? The Economist, December 2, 2004 13

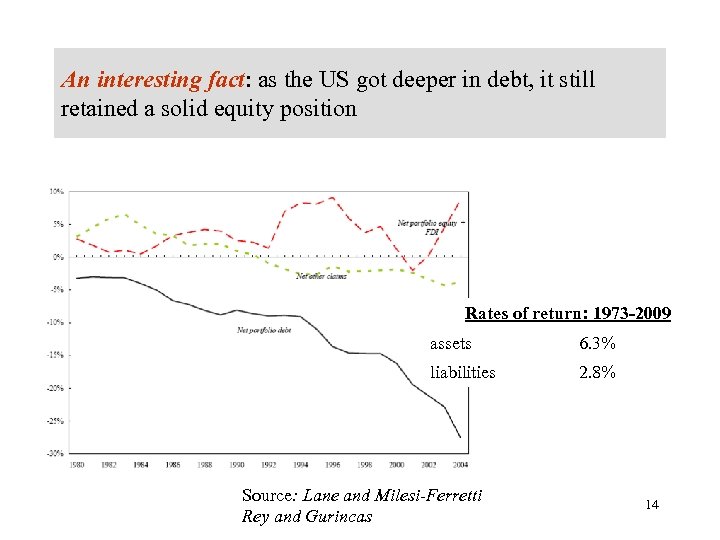

An interesting fact: as the US got deeper in debt, it still retained a solid equity position Rates of return: 1973 -2009 assets 6. 3% liabilities 2. 8% Source: Lane and Milesi-Ferretti Rey and Gurincas 14

An interesting fact: as the US got deeper in debt, it still retained a solid equity position Rates of return: 1973 -2009 assets 6. 3% liabilities 2. 8% Source: Lane and Milesi-Ferretti Rey and Gurincas 14

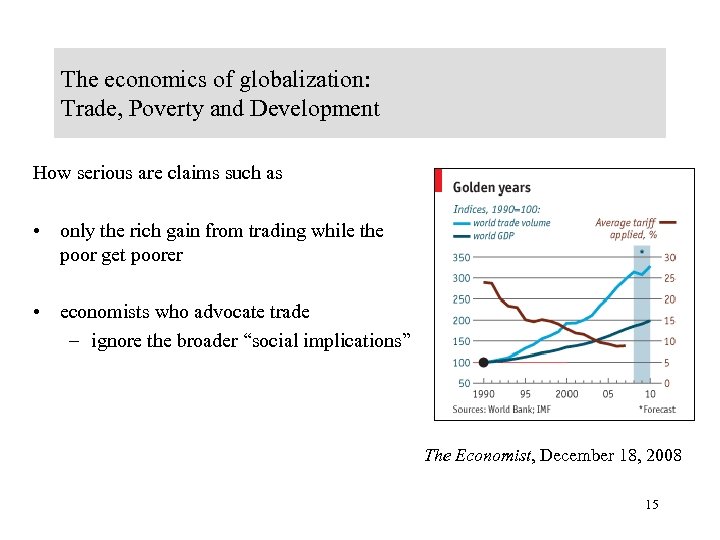

The economics of globalization: Trade, Poverty and Development How serious are claims such as • only the rich gain from trading while the poor get poorer • economists who advocate trade – ignore the broader “social implications” The Economist, December 18, 2008 15

The economics of globalization: Trade, Poverty and Development How serious are claims such as • only the rich gain from trading while the poor get poorer • economists who advocate trade – ignore the broader “social implications” The Economist, December 18, 2008 15

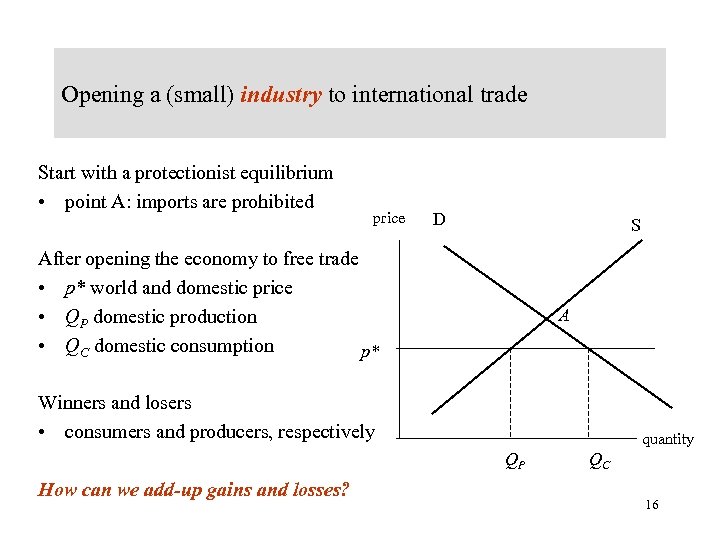

Opening a (small) industry to international trade Start with a protectionist equilibrium • point A: imports are prohibited price D S After opening the economy to free trade • p* world and domestic price • QP domestic production • QC domestic consumption p* A Winners and losers • consumers and producers, respectively quantity QP How can we add-up gains and losses? QC 16

Opening a (small) industry to international trade Start with a protectionist equilibrium • point A: imports are prohibited price D S After opening the economy to free trade • p* world and domestic price • QP domestic production • QC domestic consumption p* A Winners and losers • consumers and producers, respectively quantity QP How can we add-up gains and losses? QC 16

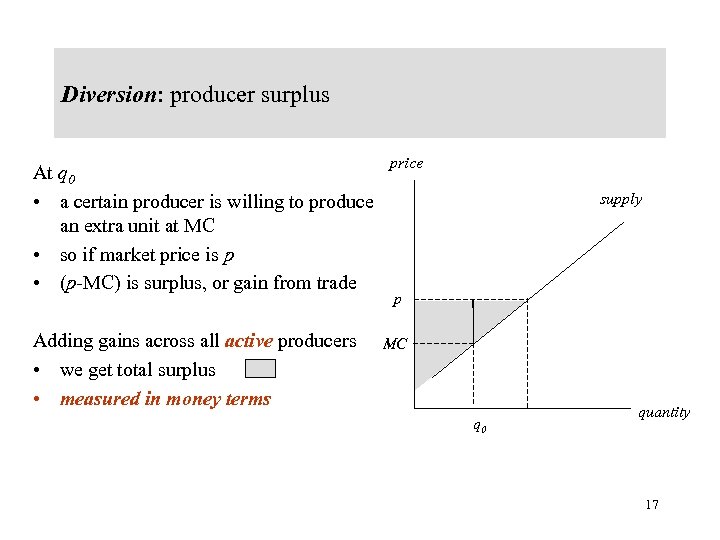

Diversion: producer surplus At q 0 • a certain producer is willing to produce an extra unit at MC • so if market price is p • (p-MC) is surplus, or gain from trade Adding gains across all active producers • we get total surplus • measured in money terms price supply p MC q 0 quantity 17

Diversion: producer surplus At q 0 • a certain producer is willing to produce an extra unit at MC • so if market price is p • (p-MC) is surplus, or gain from trade Adding gains across all active producers • we get total surplus • measured in money terms price supply p MC q 0 quantity 17

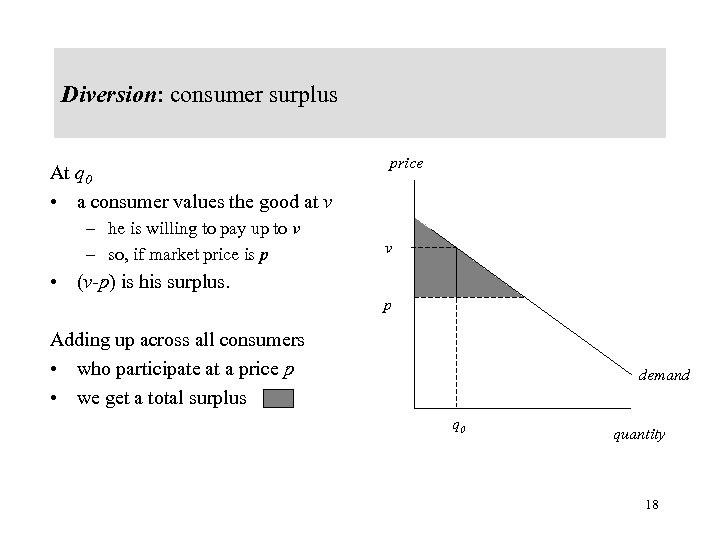

Diversion: consumer surplus At q 0 • a consumer values the good at v – he is willing to pay up to v – so, if market price is p price v • (v-p) is his surplus. p Adding up across all consumers • who participate at a price p • we get a total surplus demand q 0 quantity 18

Diversion: consumer surplus At q 0 • a consumer values the good at v – he is willing to pay up to v – so, if market price is p price v • (v-p) is his surplus. p Adding up across all consumers • who participate at a price p • we get a total surplus demand q 0 quantity 18

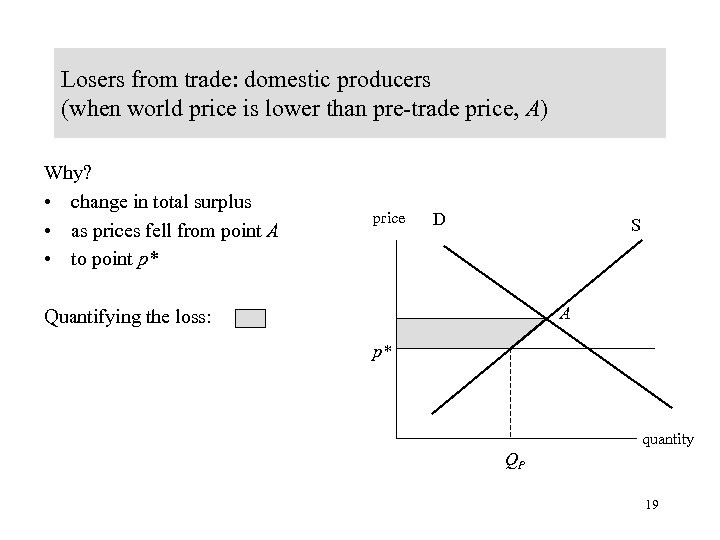

Losers from trade: domestic producers (when world price is lower than pre-trade price, A) Why? • change in total surplus • as prices fell from point A • to point p* price D S A Quantifying the loss: p* quantity QP 19

Losers from trade: domestic producers (when world price is lower than pre-trade price, A) Why? • change in total surplus • as prices fell from point A • to point p* price D S A Quantifying the loss: p* quantity QP 19

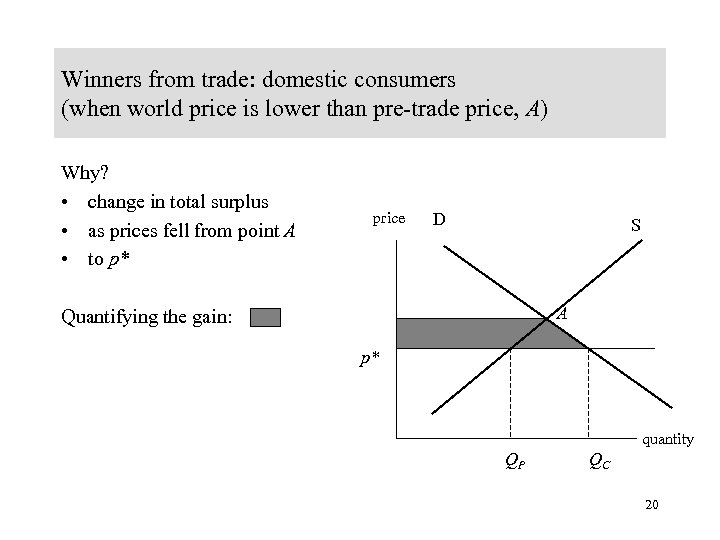

Winners from trade: domestic consumers (when world price is lower than pre-trade price, A) Why? • change in total surplus • as prices fell from point A • to p* price D S A Quantifying the gain: p* quantity QP QC 20

Winners from trade: domestic consumers (when world price is lower than pre-trade price, A) Why? • change in total surplus • as prices fell from point A • to p* price D S A Quantifying the gain: p* quantity QP QC 20

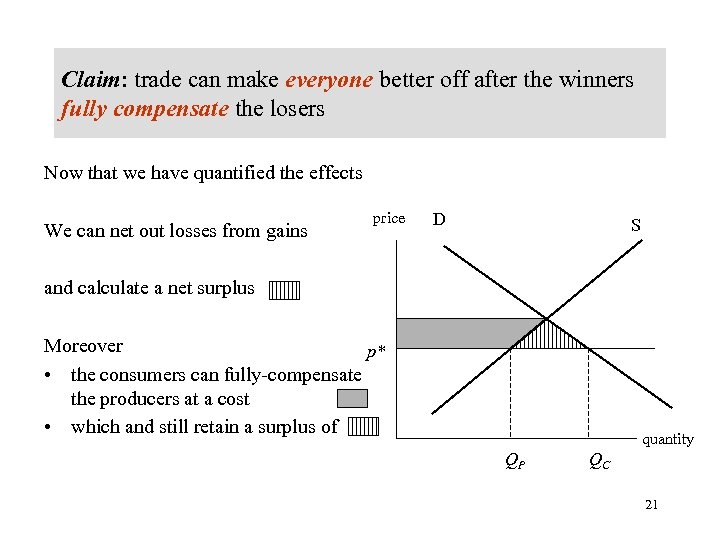

Claim: trade can make everyone better off after the winners fully compensate the losers Now that we have quantified the effects We can net out losses from gains price D S and calculate a net surplus Moreover p* • the consumers can fully-compensate the producers at a cost • which and still retain a surplus of quantity QP QC 21

Claim: trade can make everyone better off after the winners fully compensate the losers Now that we have quantified the effects We can net out losses from gains price D S and calculate a net surplus Moreover p* • the consumers can fully-compensate the producers at a cost • which and still retain a surplus of quantity QP QC 21

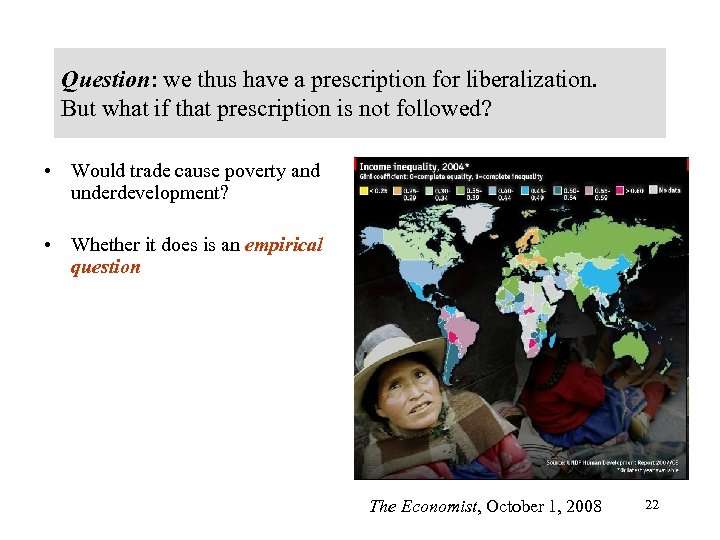

Question: we thus have a prescription for liberalization. But what if that prescription is not followed? • Would trade cause poverty and underdevelopment? • Whether it does is an empirical question The Economist, October 1, 2008 22

Question: we thus have a prescription for liberalization. But what if that prescription is not followed? • Would trade cause poverty and underdevelopment? • Whether it does is an empirical question The Economist, October 1, 2008 22

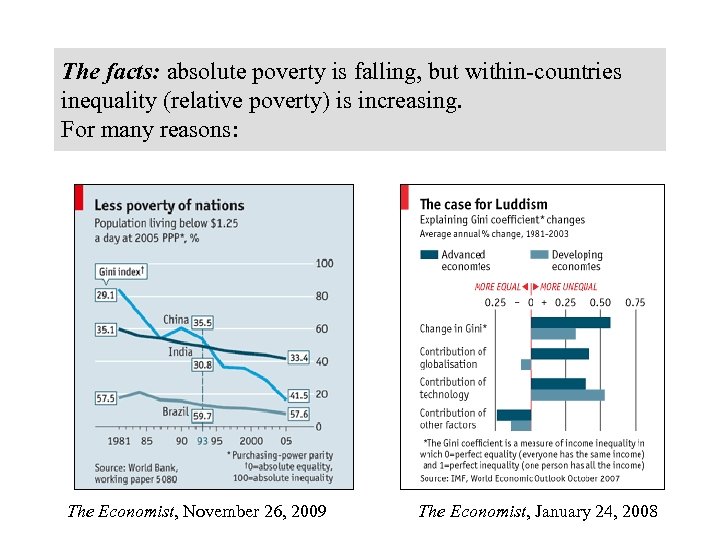

The facts: absolute poverty is falling, but within-countries inequality (relative poverty) is increasing. For many reasons: The Economist, November 26, 2009 23 The Economist, January 24, 2008

The facts: absolute poverty is falling, but within-countries inequality (relative poverty) is increasing. For many reasons: The Economist, November 26, 2009 23 The Economist, January 24, 2008

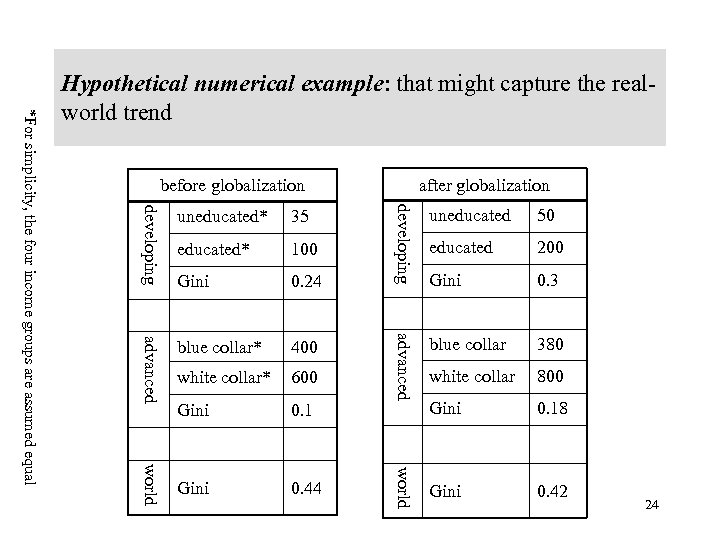

after globalization before globalization 100 Gini 0. 24 advanced blue collar* 400 white collar* 600 Gini 0. 1 Gini 0. 44 50 educated 200 Gini 0. 3 blue collar 380 white collar 800 Gini 0. 18 Gini 0. 42 world educated* uneducated advanced 35 developing uneducated* world developing *For simplicity, the four income groups are assumed equal Hypothetical numerical example: that might capture the realworld trend 24

after globalization before globalization 100 Gini 0. 24 advanced blue collar* 400 white collar* 600 Gini 0. 1 Gini 0. 44 50 educated 200 Gini 0. 3 blue collar 380 white collar 800 Gini 0. 18 Gini 0. 42 world educated* uneducated advanced 35 developing uneducated* world developing *For simplicity, the four income groups are assumed equal Hypothetical numerical example: that might capture the realworld trend 24

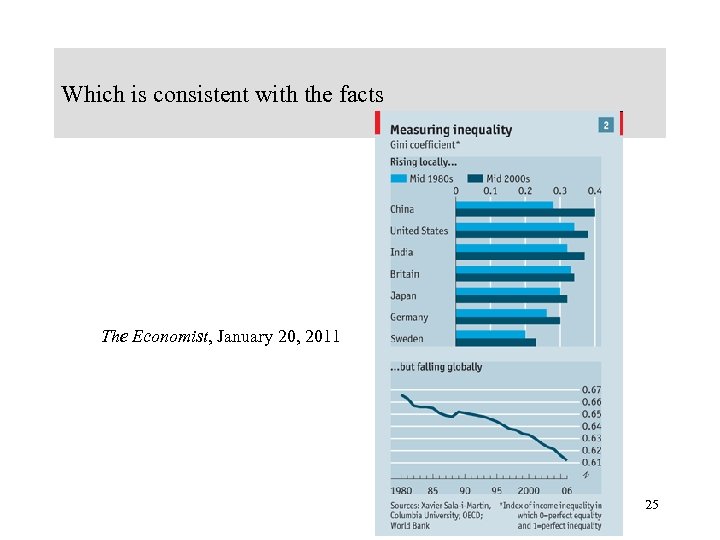

Which is consistent with the facts The Economist, January 20, 2011 25

Which is consistent with the facts The Economist, January 20, 2011 25

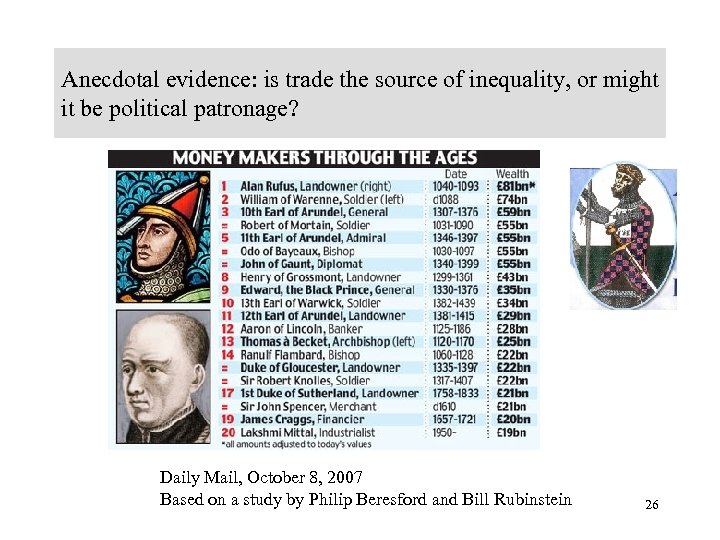

Anecdotal evidence: is trade the source of inequality, or might it be political patronage? Daily Mail, October 8, 2007 Based on a study by Philip Beresford and Bill Rubinstein 26

Anecdotal evidence: is trade the source of inequality, or might it be political patronage? Daily Mail, October 8, 2007 Based on a study by Philip Beresford and Bill Rubinstein 26

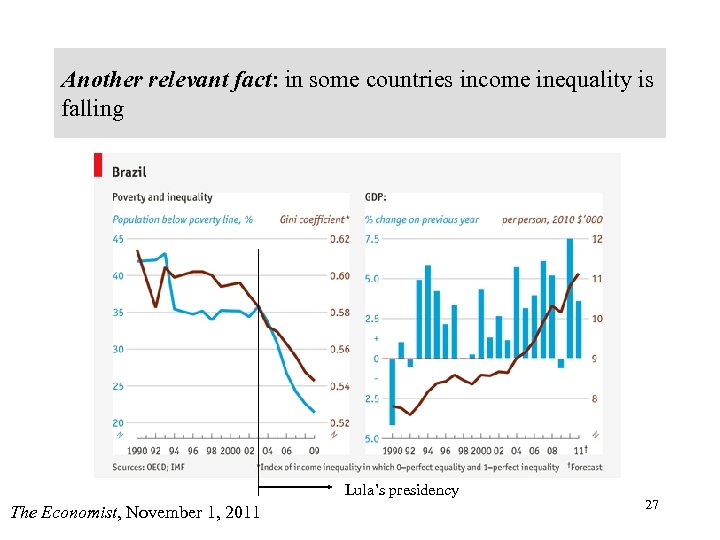

Another relevant fact: in some countries income inequality is falling Lula’s presidency The Economist, November 1, 2011 27

Another relevant fact: in some countries income inequality is falling Lula’s presidency The Economist, November 1, 2011 27

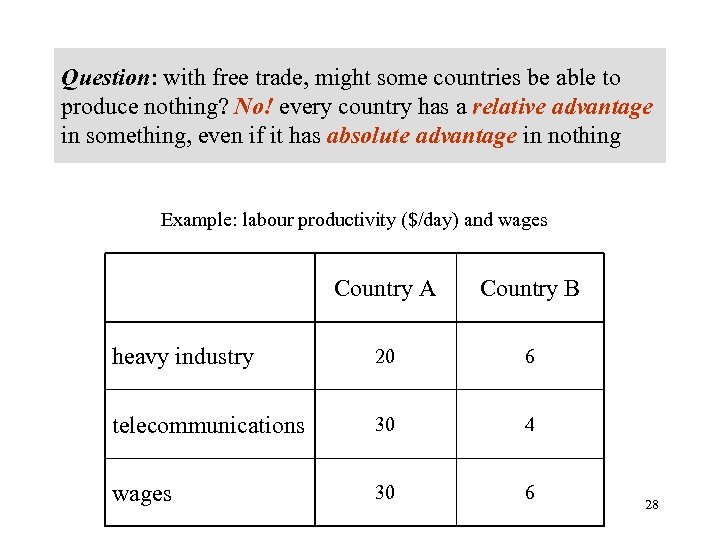

Question: with free trade, might some countries be able to produce nothing? No! every country has a relative advantage in something, even if it has absolute advantage in nothing Example: labour productivity ($/day) and wages Country A Country B heavy industry 20 6 telecommunications 30 4 wages 30 6 28

Question: with free trade, might some countries be able to produce nothing? No! every country has a relative advantage in something, even if it has absolute advantage in nothing Example: labour productivity ($/day) and wages Country A Country B heavy industry 20 6 telecommunications 30 4 wages 30 6 28

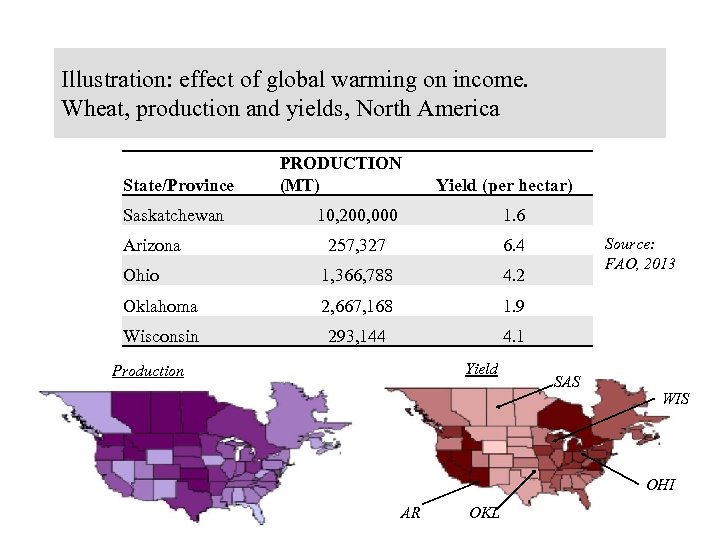

Illustration: effect of global warming on income. Wheat, production and yields, North America State/Province Saskatchewan PRODUCTION (MT) Yield (per hectar) 10, 200, 000 1. 6 257, 327 6. 4 Ohio 1, 366, 788 4. 2 Oklahoma 2, 667, 168 1. 9 Wisconsin 293, 144 4. 1 Arizona Yield Production Source: FAO, 2013 SAS WIS OHI AR OKL 29

Illustration: effect of global warming on income. Wheat, production and yields, North America State/Province Saskatchewan PRODUCTION (MT) Yield (per hectar) 10, 200, 000 1. 6 257, 327 6. 4 Ohio 1, 366, 788 4. 2 Oklahoma 2, 667, 168 1. 9 Wisconsin 293, 144 4. 1 Arizona Yield Production Source: FAO, 2013 SAS WIS OHI AR OKL 29

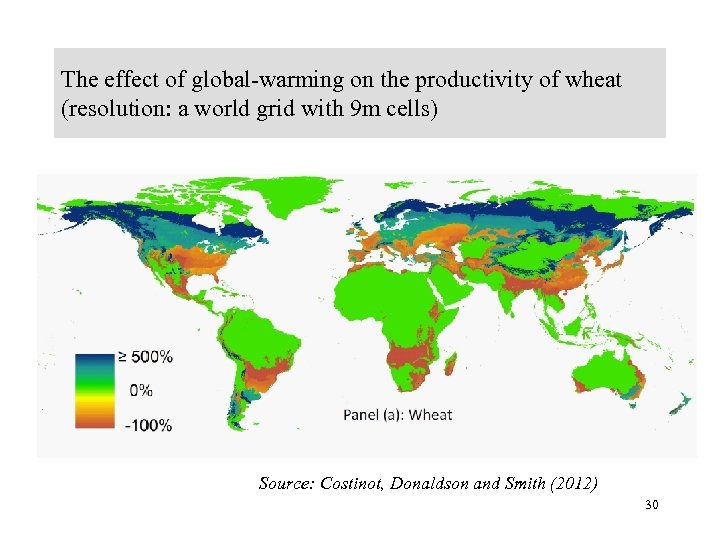

The effect of global-warming on the productivity of wheat (resolution: a world grid with 9 m cells) Source: Costinot, Donaldson and Smith (2012) 30

The effect of global-warming on the productivity of wheat (resolution: a world grid with 9 m cells) Source: Costinot, Donaldson and Smith (2012) 30

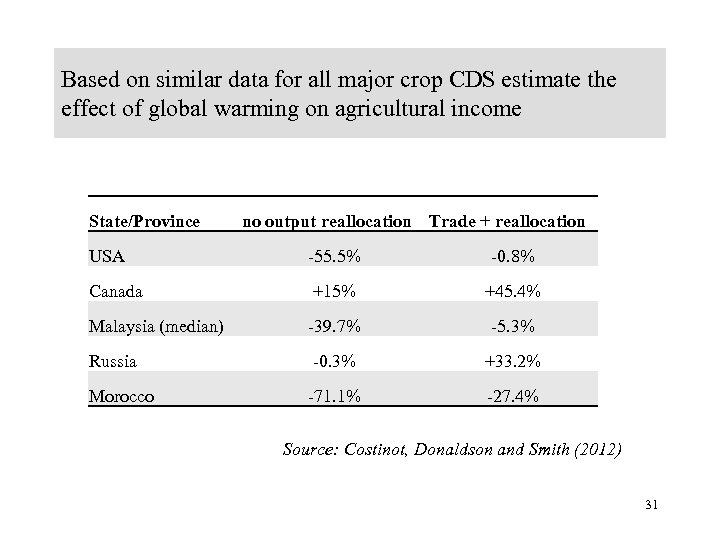

Based on similar data for all major crop CDS estimate the effect of global warming on agricultural income State/Province no output reallocation Trade + reallocation USA -55. 5% -0. 8% Canada +15% +45. 4% Malaysia (median) -39. 7% -5. 3% Russia -0. 3% +33. 2% Morocco -71. 1% -27. 4% Source: Costinot, Donaldson and Smith (2012) 31

Based on similar data for all major crop CDS estimate the effect of global warming on agricultural income State/Province no output reallocation Trade + reallocation USA -55. 5% -0. 8% Canada +15% +45. 4% Malaysia (median) -39. 7% -5. 3% Russia -0. 3% +33. 2% Morocco -71. 1% -27. 4% Source: Costinot, Donaldson and Smith (2012) 31

Diversion: do markets always achieve efficient outcomes? Not in the case of externalities Paradigmatic example: pollution A common misunderstanding • the problem is not the “dirty stuff” But rather the missing market for pollutants • the polluter • need not pay (a market price) • the bearer of pollution for taking the stuff • he just dumps it 32

Diversion: do markets always achieve efficient outcomes? Not in the case of externalities Paradigmatic example: pollution A common misunderstanding • the problem is not the “dirty stuff” But rather the missing market for pollutants • the polluter • need not pay (a market price) • the bearer of pollution for taking the stuff • he just dumps it 32

Externalities: a simple numerical example Consider a polluting industry • Market price of output: P=35 • Private cost of production: 20 – so the industry makes a profit Extra cost of pollution (illness, economic damage, aesthetic damage): C • social cost of production is 20+C • had a market existed, the neighbours would negotiate a price (at least) C • and the industry would face the full social cost of production Suppose C<15 • production is economically efficient – though fairness may require that neighbours may have a share of profits Shut-down otherwise 33

Externalities: a simple numerical example Consider a polluting industry • Market price of output: P=35 • Private cost of production: 20 – so the industry makes a profit Extra cost of pollution (illness, economic damage, aesthetic damage): C • social cost of production is 20+C • had a market existed, the neighbours would negotiate a price (at least) C • and the industry would face the full social cost of production Suppose C<15 • production is economically efficient – though fairness may require that neighbours may have a share of profits Shut-down otherwise 33

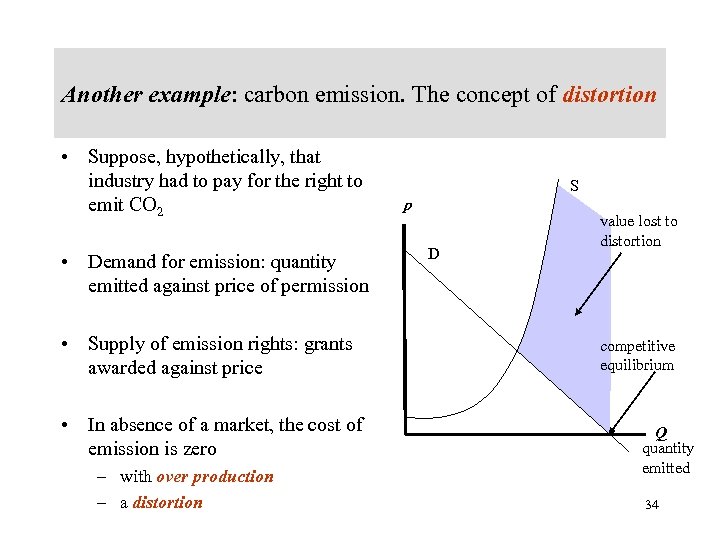

Another example: carbon emission. The concept of distortion • Suppose, hypothetically, that industry had to pay for the right to emit CO 2 • Demand for emission: quantity emitted against price of permission • Supply of emission rights: grants awarded against price • In absence of a market, the cost of emission is zero – with over production – a distortion S p D value lost to distortion competitive equilibrium Q quantity emitted 34

Another example: carbon emission. The concept of distortion • Suppose, hypothetically, that industry had to pay for the right to emit CO 2 • Demand for emission: quantity emitted against price of permission • Supply of emission rights: grants awarded against price • In absence of a market, the cost of emission is zero – with over production – a distortion S p D value lost to distortion competitive equilibrium Q quantity emitted 34

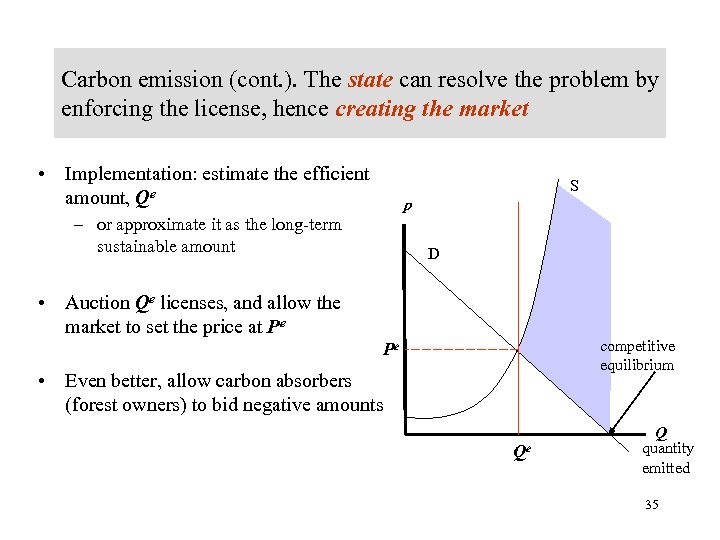

Carbon emission (cont. ). The state can resolve the problem by enforcing the license, hence creating the market • Implementation: estimate the efficient amount, Qe S p – or approximate it as the long-term sustainable amount D • Auction Qe licenses, and allow the market to set the price at Pe competitive equilibrium Pe • Even better, allow carbon absorbers (forest owners) to bid negative amounts Qe Q quantity emitted 35

Carbon emission (cont. ). The state can resolve the problem by enforcing the license, hence creating the market • Implementation: estimate the efficient amount, Qe S p – or approximate it as the long-term sustainable amount D • Auction Qe licenses, and allow the market to set the price at Pe competitive equilibrium Pe • Even better, allow carbon absorbers (forest owners) to bid negative amounts Qe Q quantity emitted 35

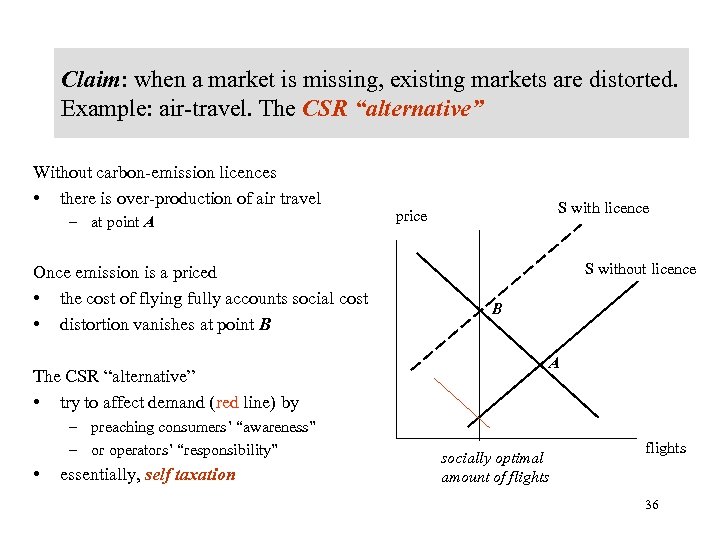

Claim: when a market is missing, existing markets are distorted. Example: air-travel. The CSR “alternative” Without carbon-emission licences • there is over-production of air travel – at point A Once emission is a priced • the cost of flying fully accounts social cost • distortion vanishes at point B The CSR “alternative” • try to affect demand (red line) by – preaching consumers’ “awareness” – or operators’ “responsibility” • essentially, self taxation S with licence price S without licence B A socially optimal amount of flights 36

Claim: when a market is missing, existing markets are distorted. Example: air-travel. The CSR “alternative” Without carbon-emission licences • there is over-production of air travel – at point A Once emission is a priced • the cost of flying fully accounts social cost • distortion vanishes at point B The CSR “alternative” • try to affect demand (red line) by – preaching consumers’ “awareness” – or operators’ “responsibility” • essentially, self taxation S with licence price S without licence B A socially optimal amount of flights 36

The “old fashioned” approach: some goods (services) have no market; the state should regulate their production Goods that have no market: public goods For example • law and order • protection of property rights • defence • regulating emission In practice, identifying externalities is difficult and contested • for example: education, health, equal opportunities, fairness 37

The “old fashioned” approach: some goods (services) have no market; the state should regulate their production Goods that have no market: public goods For example • law and order • protection of property rights • defence • regulating emission In practice, identifying externalities is difficult and contested • for example: education, health, equal opportunities, fairness 37

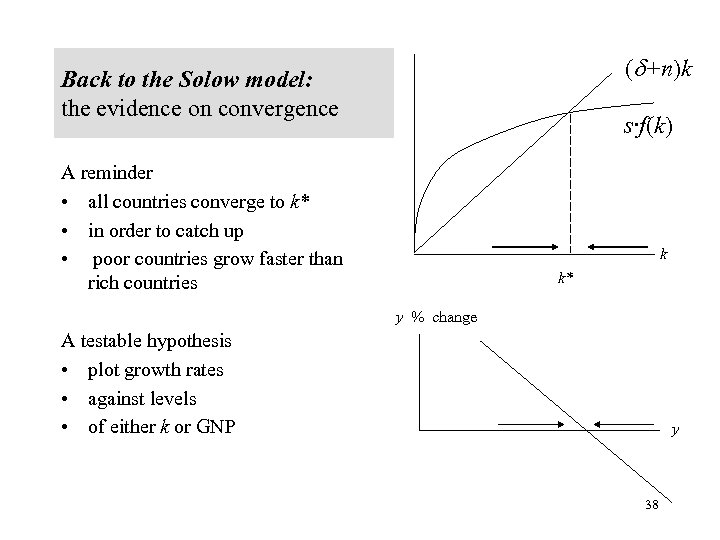

( +n)k Back to the Solow model: the evidence on convergence s·f(k) A reminder • all countries converge to k* • in order to catch up • poor countries grow faster than rich countries k k* y % change A testable hypothesis • plot growth rates • against levels • of either k or GNP y 38

( +n)k Back to the Solow model: the evidence on convergence s·f(k) A reminder • all countries converge to k* • in order to catch up • poor countries grow faster than rich countries k k* y % change A testable hypothesis • plot growth rates • against levels • of either k or GNP y 38

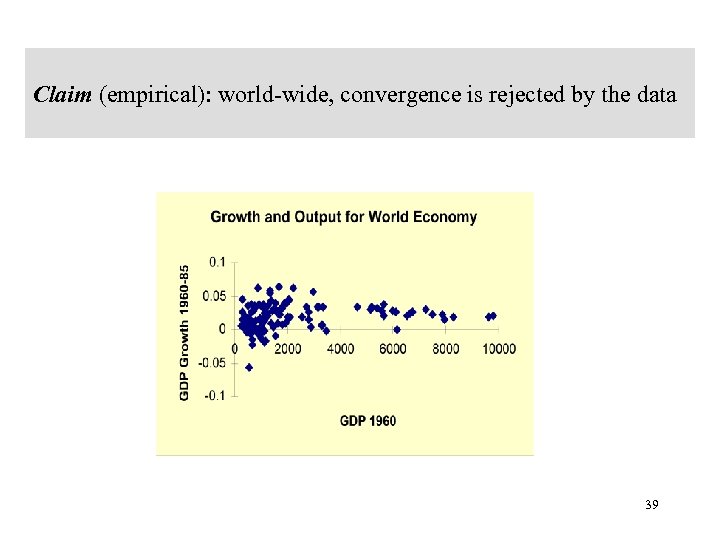

Claim (empirical): world-wide, convergence is rejected by the data 39

Claim (empirical): world-wide, convergence is rejected by the data 39

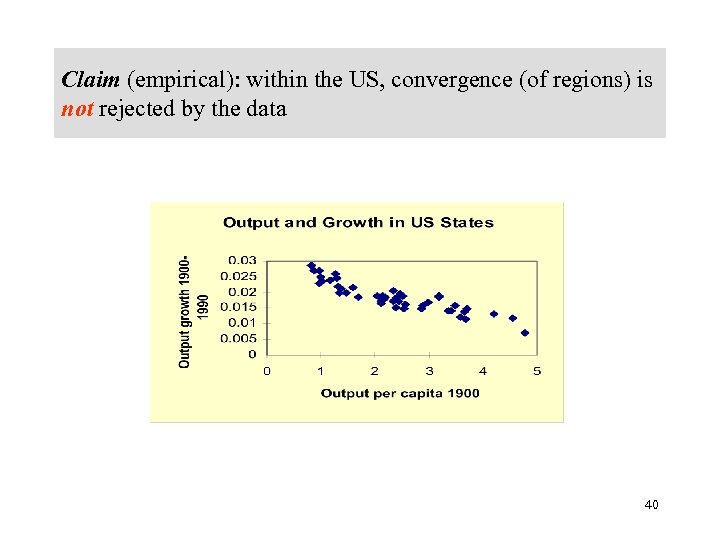

Claim (empirical): within the US, convergence (of regions) is not rejected by the data 40

Claim (empirical): within the US, convergence (of regions) is not rejected by the data 40

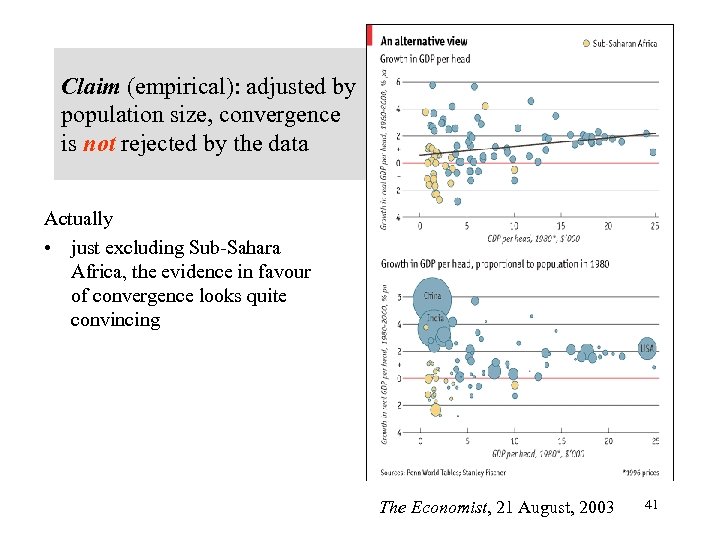

Claim (empirical): adjusted by population size, convergence is not rejected by the data Actually • just excluding Sub-Sahara Africa, the evidence in favour of convergence looks quite convincing The Economist, 21 August, 2003 41

Claim (empirical): adjusted by population size, convergence is not rejected by the data Actually • just excluding Sub-Sahara Africa, the evidence in favour of convergence looks quite convincing The Economist, 21 August, 2003 41

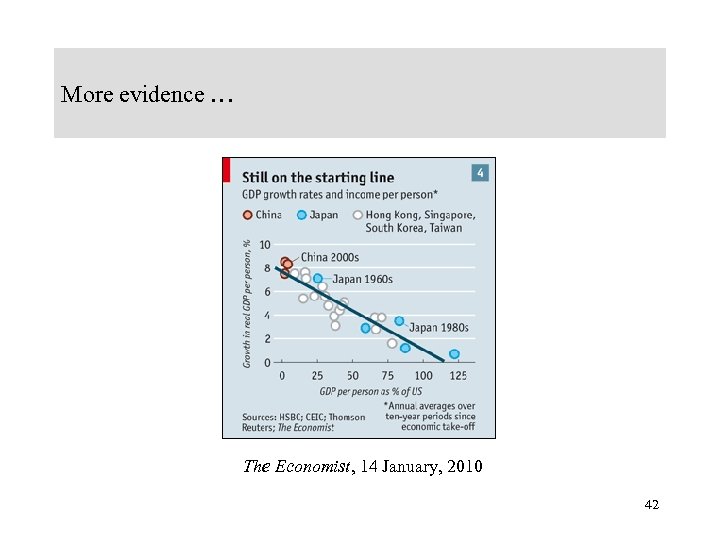

More evidence … The Economist, 14 January, 2010 42

More evidence … The Economist, 14 January, 2010 42

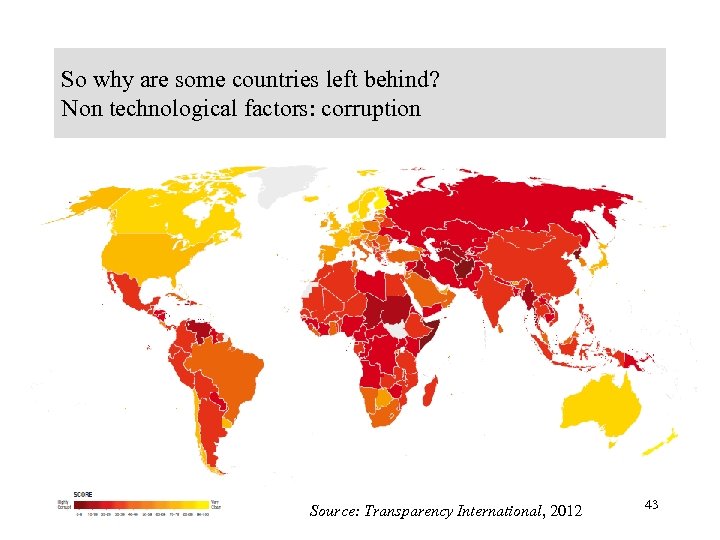

So why are some countries left behind? Non technological factors: corruption Source: Transparency International, 2012 43

So why are some countries left behind? Non technological factors: corruption Source: Transparency International, 2012 43

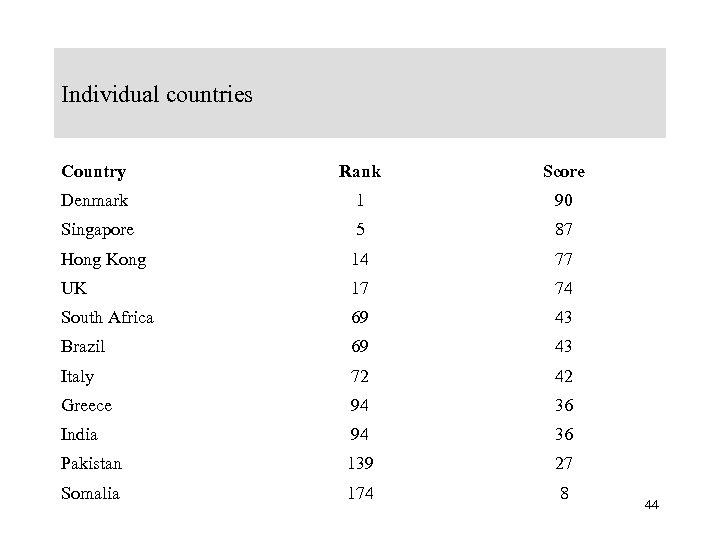

Individual countries Country Rank Score Denmark 1 90 Singapore 5 87 Hong Kong 14 77 UK 17 74 South Africa 69 43 Brazil 69 43 Italy 72 42 Greece 94 36 India 94 36 Pakistan 139 27 Somalia 174 8 44

Individual countries Country Rank Score Denmark 1 90 Singapore 5 87 Hong Kong 14 77 UK 17 74 South Africa 69 43 Brazil 69 43 Italy 72 42 Greece 94 36 India 94 36 Pakistan 139 27 Somalia 174 8 44

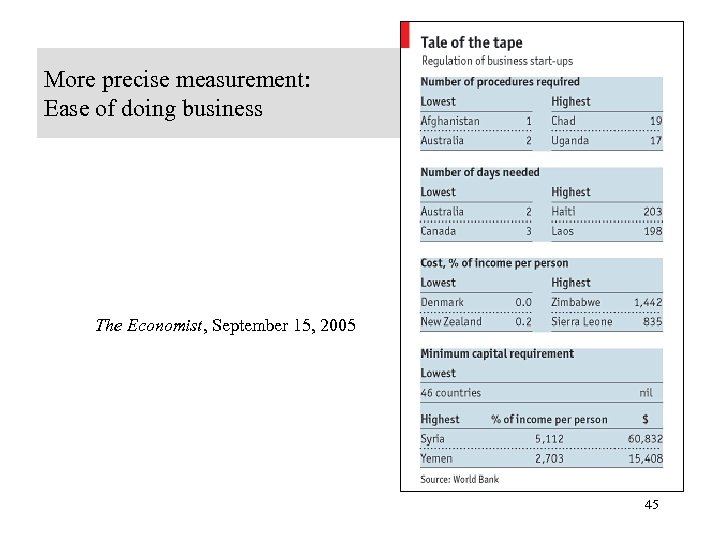

More precise measurement: Ease of doing business The Economist, September 15, 2005 45

More precise measurement: Ease of doing business The Economist, September 15, 2005 45

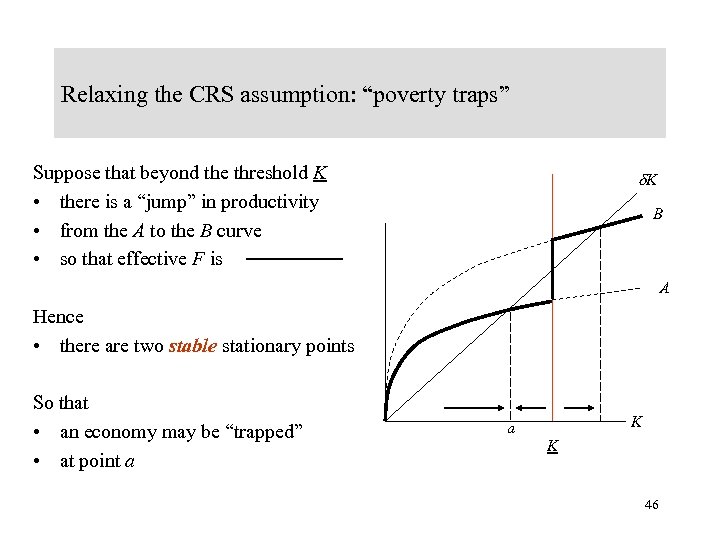

Relaxing the CRS assumption: “poverty traps” Suppose that beyond the threshold K • there is a “jump” in productivity • from the A to the B curve • so that effective F is K B A Hence • there are two stable stationary points So that • an economy may be “trapped” • at point a K 46

Relaxing the CRS assumption: “poverty traps” Suppose that beyond the threshold K • there is a “jump” in productivity • from the A to the B curve • so that effective F is K B A Hence • there are two stable stationary points So that • an economy may be “trapped” • at point a K 46

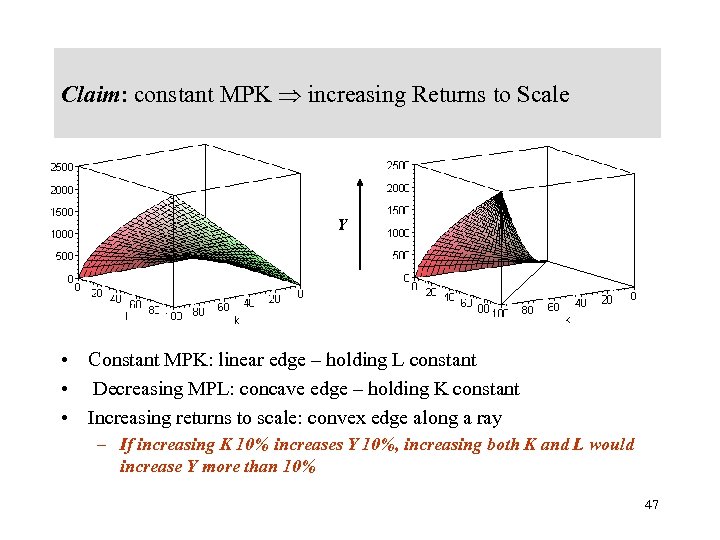

Claim: constant MPK increasing Returns to Scale Y • Constant MPK: linear edge – holding L constant • Decreasing MPL: concave edge – holding K constant • Increasing returns to scale: convex edge along a ray – If increasing K 10% increases Y 10%, increasing both K and L would increase Y more than 10% 47

Claim: constant MPK increasing Returns to Scale Y • Constant MPK: linear edge – holding L constant • Decreasing MPL: concave edge – holding K constant • Increasing returns to scale: convex edge along a ray – If increasing K 10% increases Y 10%, increasing both K and L would increase Y more than 10% 47

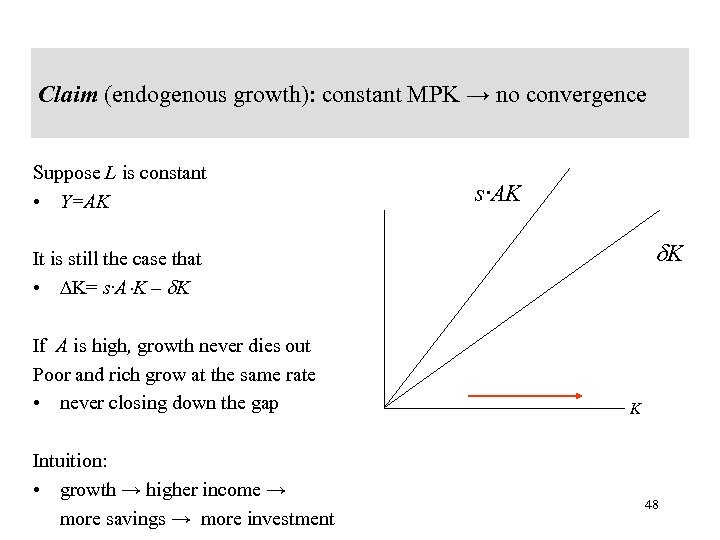

Claim (endogenous growth): constant MPK → no convergence Suppose L is constant • Y=AK s·AK K It is still the case that • K= s·A K – K If A is high, growth never dies out Poor and rich grow at the same rate • never closing down the gap Intuition: • growth → higher income → more savings → more investment K 48

Claim (endogenous growth): constant MPK → no convergence Suppose L is constant • Y=AK s·AK K It is still the case that • K= s·A K – K If A is high, growth never dies out Poor and rich grow at the same rate • never closing down the gap Intuition: • growth → higher income → more savings → more investment K 48

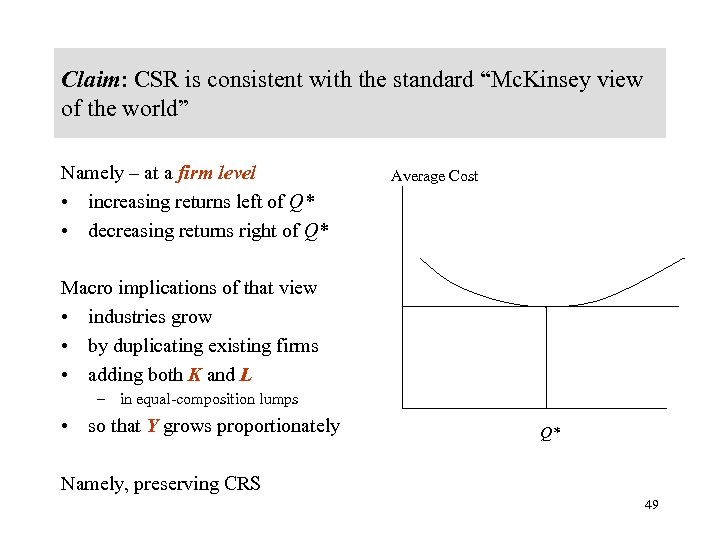

Claim: CSR is consistent with the standard “Mc. Kinsey view of the world” Namely – at a firm level • increasing returns left of Q* • decreasing returns right of Q* Average Cost Macro implications of that view • industries grow • by duplicating existing firms • adding both K and L – in equal-composition lumps • so that Y grows proportionately Q* Namely, preserving CRS 49

Claim: CSR is consistent with the standard “Mc. Kinsey view of the world” Namely – at a firm level • increasing returns left of Q* • decreasing returns right of Q* Average Cost Macro implications of that view • industries grow • by duplicating existing firms • adding both K and L – in equal-composition lumps • so that Y grows proportionately Q* Namely, preserving CRS 49

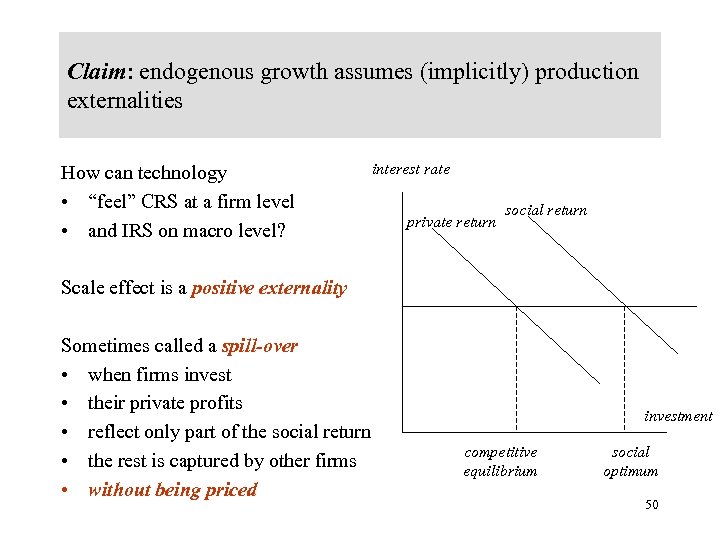

Claim: endogenous growth assumes (implicitly) production externalities How can technology • “feel” CRS at a firm level • and IRS on macro level? interest rate private return social return Scale effect is a positive externality Sometimes called a spill-over • when firms invest • their private profits • reflect only part of the social return • the rest is captured by other firms • without being priced investment competitive equilibrium social optimum 50

Claim: endogenous growth assumes (implicitly) production externalities How can technology • “feel” CRS at a firm level • and IRS on macro level? interest rate private return social return Scale effect is a positive externality Sometimes called a spill-over • when firms invest • their private profits • reflect only part of the social return • the rest is captured by other firms • without being priced investment competitive equilibrium social optimum 50

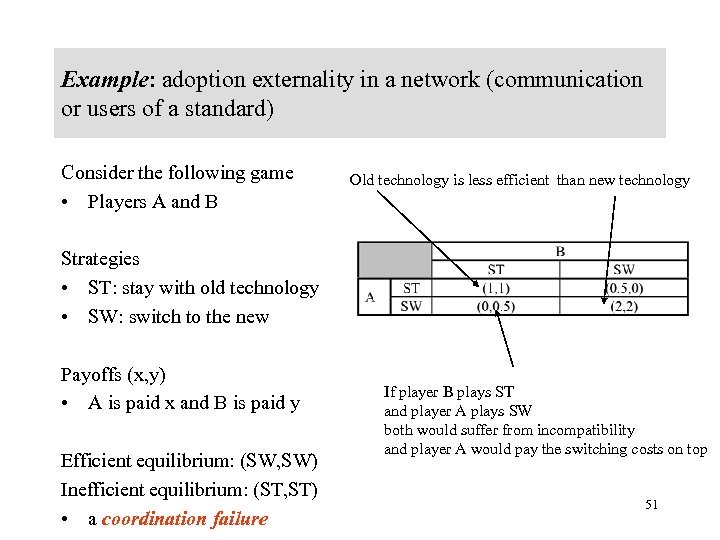

Example: adoption externality in a network (communication or users of a standard) Consider the following game • Players A and B Old technology is less efficient than new technology Strategies • ST: stay with old technology • SW: switch to the new Payoffs (x, y) • A is paid x and B is paid y Efficient equilibrium: (SW, SW) Inefficient equilibrium: (ST, ST) • a coordination failure If player B plays ST and player A plays SW both would suffer from incompatibility and player A would pay the switching costs on top 51

Example: adoption externality in a network (communication or users of a standard) Consider the following game • Players A and B Old technology is less efficient than new technology Strategies • ST: stay with old technology • SW: switch to the new Payoffs (x, y) • A is paid x and B is paid y Efficient equilibrium: (SW, SW) Inefficient equilibrium: (ST, ST) • a coordination failure If player B plays ST and player A plays SW both would suffer from incompatibility and player A would pay the switching costs on top 51

Real world example of network externalities: QWERTY is the standard for key-boards (in English) • inherited from the type-writer Standards are paradigmatic examples of network externalities • the value of adopting a standard • is a function of others adopting the same standard 52

Real world example of network externalities: QWERTY is the standard for key-boards (in English) • inherited from the type-writer Standards are paradigmatic examples of network externalities • the value of adopting a standard • is a function of others adopting the same standard 52

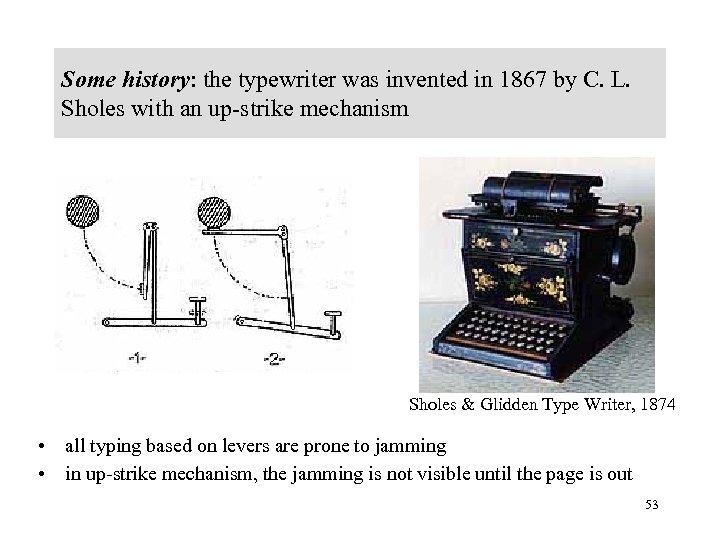

Some history: the typewriter was invented in 1867 by C. L. Sholes with an up-strike mechanism Sholes & Glidden Type Writer, 1874 • all typing based on levers are prone to jamming • in up-strike mechanism, the jamming is not visible until the page is out 53

Some history: the typewriter was invented in 1867 by C. L. Sholes with an up-strike mechanism Sholes & Glidden Type Writer, 1874 • all typing based on levers are prone to jamming • in up-strike mechanism, the jamming is not visible until the page is out 53

Claim (by Paul David): the QWERTY standard is inefficient Evidence for the inefficiency • QWERTY was invented with the deliberate intention of slowing down the speed of typing (in order to avoid jamming) • a more efficient arrangement exist – Dvorak Simplified Keyboard, DSK – where keys for high-frequency letters are concentrated • the US Navy (1940) has estimated that retraining a secretary would pay back within 10 days • some Apple models offered a button to switch standard – with an increased typing speed of 20 -40% 54

Claim (by Paul David): the QWERTY standard is inefficient Evidence for the inefficiency • QWERTY was invented with the deliberate intention of slowing down the speed of typing (in order to avoid jamming) • a more efficient arrangement exist – Dvorak Simplified Keyboard, DSK – where keys for high-frequency letters are concentrated • the US Navy (1940) has estimated that retraining a secretary would pay back within 10 days • some Apple models offered a button to switch standard – with an increased typing speed of 20 -40% 54

… and its survival is an “historic accident” Still, the more efficient technology was never adopted Interpretation • the industry is stuck in the (ST, ST) equilibrium Each player expects that the others are conservative, and would play ST • hence, switching implies bearing a cost • and becoming incompatible with other’s typewriters Conclusion • spill-overs probably exist, but it is doubtful whether they are so pervasive so as to seriously undermine CRS on a macro scale 55

… and its survival is an “historic accident” Still, the more efficient technology was never adopted Interpretation • the industry is stuck in the (ST, ST) equilibrium Each player expects that the others are conservative, and would play ST • hence, switching implies bearing a cost • and becoming incompatible with other’s typewriters Conclusion • spill-overs probably exist, but it is doubtful whether they are so pervasive so as to seriously undermine CRS on a macro scale 55

Implication: with positive externalities, competitive equilibrium will be economically inefficient. To restore efficiency, the state has to implement industrial policy While negative externalities lead to over production • to be resolved by way of taxation Positive externalities lead to under production • to be resolved by way of investment subsidies • so that investing companies would internalize the full economic value that they generate Such policies widely used in the 1950 s in South America • never worked in practice 56

Implication: with positive externalities, competitive equilibrium will be economically inefficient. To restore efficiency, the state has to implement industrial policy While negative externalities lead to over production • to be resolved by way of taxation Positive externalities lead to under production • to be resolved by way of investment subsidies • so that investing companies would internalize the full economic value that they generate Such policies widely used in the 1950 s in South America • never worked in practice 56

Summary (my own view) • While examples of the sort of QWERTY are convincing enough • There is no evidence that their quantitative effect, on a macro level, is strong enough to make the Solow model irrelevant • Better view the process of accumulation is critical to economic growth – and treat technological innovations as an exogenous process • At the same time, the role of the state in providing infrastructure, law and order, protection of property rights etc. – is absolutely essential 57

Summary (my own view) • While examples of the sort of QWERTY are convincing enough • There is no evidence that their quantitative effect, on a macro level, is strong enough to make the Solow model irrelevant • Better view the process of accumulation is critical to economic growth – and treat technological innovations as an exogenous process • At the same time, the role of the state in providing infrastructure, law and order, protection of property rights etc. – is absolutely essential 57