cc6de145f2e3ab84583c84ccd014bb64.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 69

LTC (P) Kurt W Grathwohl, MD, FS, FCCP Program Director Anesth/Critical Care Medical Director STICU, BAMC Associate Professor of Surgery, Trauma Division, UTHSCSA Critical Care Consultant for the Army Surgeon General

LTC (P) Kurt W Grathwohl, MD, FS, FCCP Program Director Anesth/Critical Care Medical Director STICU, BAMC Associate Professor of Surgery, Trauma Division, UTHSCSA Critical Care Consultant for the Army Surgeon General

‘‘The manner of treatment is of importance in only a minority of cases, since many subjects of intracranial injury are fated to die whatever measures may be adopted for their relief, and a still greater number are destined to recover though left entirely to the resources of nature. It is probable that in by far the larger proportion of cases in which the issue is determined by treatment it is met in the initial stage, and by insuring restoration from primary shock’’ Phelps C. Principles of treatment. In: Traumatic Injuries of the Brain and its Membranes: with a special study of Pistol-shot wounds of the head in their medico-legal and surgical relations. New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1897. p. 206– 32.

‘‘The manner of treatment is of importance in only a minority of cases, since many subjects of intracranial injury are fated to die whatever measures may be adopted for their relief, and a still greater number are destined to recover though left entirely to the resources of nature. It is probable that in by far the larger proportion of cases in which the issue is determined by treatment it is met in the initial stage, and by insuring restoration from primary shock’’ Phelps C. Principles of treatment. In: Traumatic Injuries of the Brain and its Membranes: with a special study of Pistol-shot wounds of the head in their medico-legal and surgical relations. New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1897. p. 206– 32.

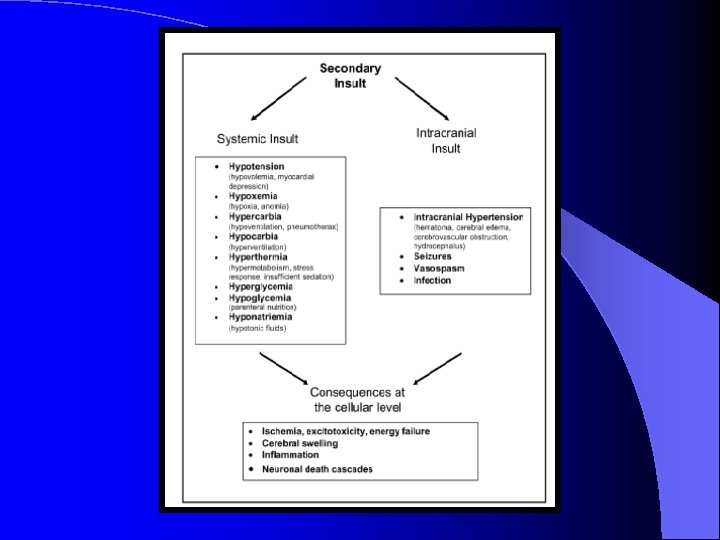

Although secondary insults from factors such as hypotension, hypoxemia, and hyperventilation increase morbidity and mortality, data are not yet available to indicate whether scrupulous prevention and prompt treatment of secondary injuries will reduce morbidity and mortality. In addition, no specific intervention to date has improved overall long-term outcome. With ongoing research, perhaps active interventions will become available. Until that time, thoughtful and careful attention to physiologic management provides the greatest opportunity for a good outcome.

Although secondary insults from factors such as hypotension, hypoxemia, and hyperventilation increase morbidity and mortality, data are not yet available to indicate whether scrupulous prevention and prompt treatment of secondary injuries will reduce morbidity and mortality. In addition, no specific intervention to date has improved overall long-term outcome. With ongoing research, perhaps active interventions will become available. Until that time, thoughtful and careful attention to physiologic management provides the greatest opportunity for a good outcome.

Summary: Management of TBI • • • Normocarbia Normovolemia Normoglycemia Normotension Normothermia

Summary: Management of TBI • • • Normocarbia Normovolemia Normoglycemia Normotension Normothermia

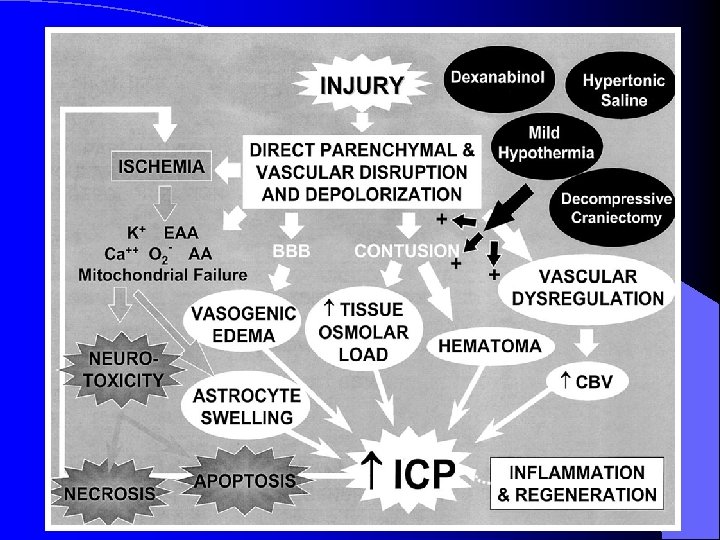

Traumatic Brain Injury Pathophysiology Secondary Injury BRAIN Research ? Outcomes Treatment Body

Traumatic Brain Injury Pathophysiology Secondary Injury BRAIN Research ? Outcomes Treatment Body

Medical Practices l Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomized controlled trials Smith GCS, Pell JP. BMJ 2003; 327: 1459 -61

Medical Practices l Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomized controlled trials Smith GCS, Pell JP. BMJ 2003; 327: 1459 -61

Evidence Based Medical Practices l Penicillin – Alexander Fleming 1920 Lysozyme l Mold 1928 l – Medical Community acted coldly l Once Bacteria entered body nothing could be done – Florey/Chain 1930’s Powdered Form 1941 l Overwhelming casualties WWII l

Evidence Based Medical Practices l Penicillin – Alexander Fleming 1920 Lysozyme l Mold 1928 l – Medical Community acted coldly l Once Bacteria entered body nothing could be done – Florey/Chain 1930’s Powdered Form 1941 l Overwhelming casualties WWII l

Medical Practices Pulse Oximetry Pulse oximetry can detect hypoxemia and related events l No evidence that pulse oximetry affects the outcome of anesthesia l Conflicting subjective and objective results of studies l – Intense, methodical collection of data – Large population l The value of perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry is questionable – No improved reliable outcomes – Effectiveness – Efficiency. Pedersen T, Dyrlund Pedersen B, Møller AM. Pulse oximetry for perioperative monitoring. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 2. Art. No. : CD 002013. DOI: 10. 1002/14651858. CD 002013

Medical Practices Pulse Oximetry Pulse oximetry can detect hypoxemia and related events l No evidence that pulse oximetry affects the outcome of anesthesia l Conflicting subjective and objective results of studies l – Intense, methodical collection of data – Large population l The value of perioperative monitoring with pulse oximetry is questionable – No improved reliable outcomes – Effectiveness – Efficiency. Pedersen T, Dyrlund Pedersen B, Møller AM. Pulse oximetry for perioperative monitoring. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 2. Art. No. : CD 002013. DOI: 10. 1002/14651858. CD 002013

Medical Practices l 1767 - The Dutch Method of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation- l First Introduced to colonists by the American Indians 1. Keep the patient warm 2. Artificial respiration 3. Fumigation tobacco smoke through the rectum 4. Place stimulants orally and rectally 5. Bleeding Abandoned when research found 4 ounces tobacco could kill a dog

Medical Practices l 1767 - The Dutch Method of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation- l First Introduced to colonists by the American Indians 1. Keep the patient warm 2. Artificial respiration 3. Fumigation tobacco smoke through the rectum 4. Place stimulants orally and rectally 5. Bleeding Abandoned when research found 4 ounces tobacco could kill a dog

Woodpecker- TBI? High Decel 1200 g 1. Small Size/smooth surface reduces stress 2. 2. Short duration 3. 3. Minimize side to side movement

Woodpecker- TBI? High Decel 1200 g 1. Small Size/smooth surface reduces stress 2. 2. Short duration 3. 3. Minimize side to side movement

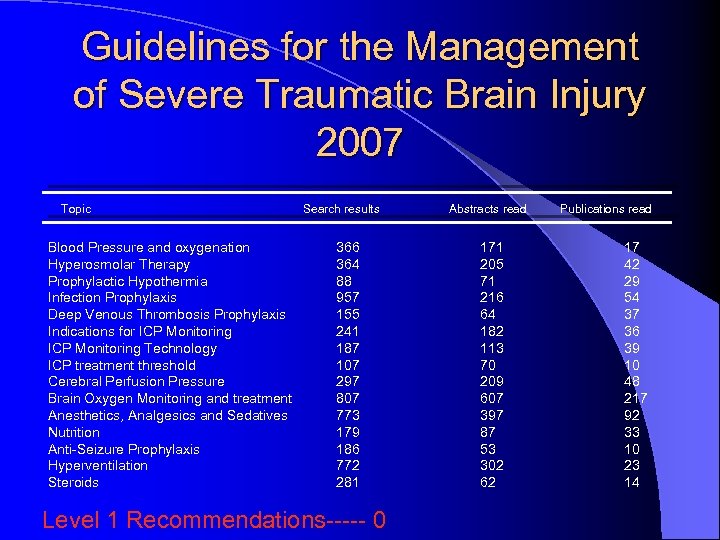

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury 2007 Topic Blood Pressure and oxygenation Hyperosmolar Therapy Prophylactic Hypothermia Infection Prophylaxis Deep Venous Thrombosis Prophylaxis Indications for ICP Monitoring Technology ICP treatment threshold Cerebral Perfusion Pressure Brain Oxygen Monitoring and treatment Anesthetics, Analgesics and Sedatives Nutrition Anti-Seizure Prophylaxis Hyperventilation Steroids Search results 366 364 88 957 155 241 187 107 297 807 773 179 186 772 281 Level 1 Recommendations----- 0 Abstracts read 171 205 71 216 64 182 113 70 209 607 397 87 53 302 62 Publications read 17 42 29 54 37 36 39 10 48 217 92 33 10 23 14

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury 2007 Topic Blood Pressure and oxygenation Hyperosmolar Therapy Prophylactic Hypothermia Infection Prophylaxis Deep Venous Thrombosis Prophylaxis Indications for ICP Monitoring Technology ICP treatment threshold Cerebral Perfusion Pressure Brain Oxygen Monitoring and treatment Anesthetics, Analgesics and Sedatives Nutrition Anti-Seizure Prophylaxis Hyperventilation Steroids Search results 366 364 88 957 155 241 187 107 297 807 773 179 186 772 281 Level 1 Recommendations----- 0 Abstracts read 171 205 71 216 64 182 113 70 209 607 397 87 53 302 62 Publications read 17 42 29 54 37 36 39 10 48 217 92 33 10 23 14

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury 2007 l Brain Trauma Foundation l American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) l Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) l www. braintrauma. org l Journal of Neurotrauma Vol 24, S 1 2007

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury 2007 l Brain Trauma Foundation l American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) l Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) l www. braintrauma. org l Journal of Neurotrauma Vol 24, S 1 2007

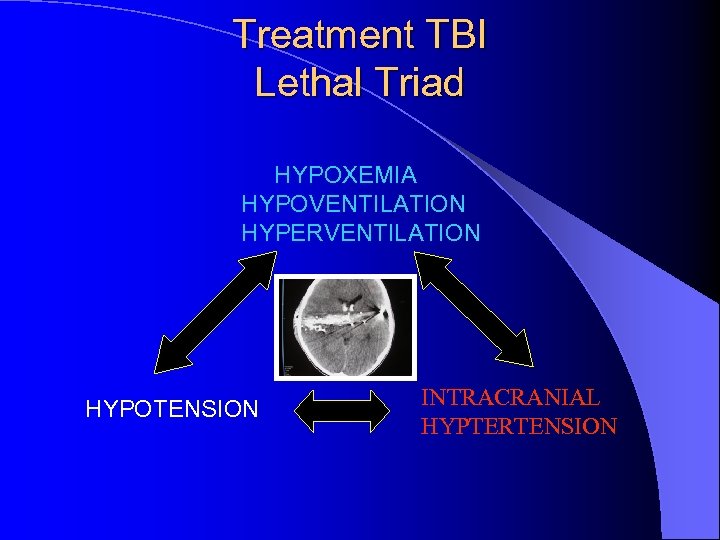

Treatment TBI Lethal Triad HYPOXEMIA HYPOVENTILATION HYPERVENTILATION HYPOTENSION INTRACRANIAL HYPTERTENSION

Treatment TBI Lethal Triad HYPOXEMIA HYPOVENTILATION HYPERVENTILATION HYPOTENSION INTRACRANIAL HYPTERTENSION

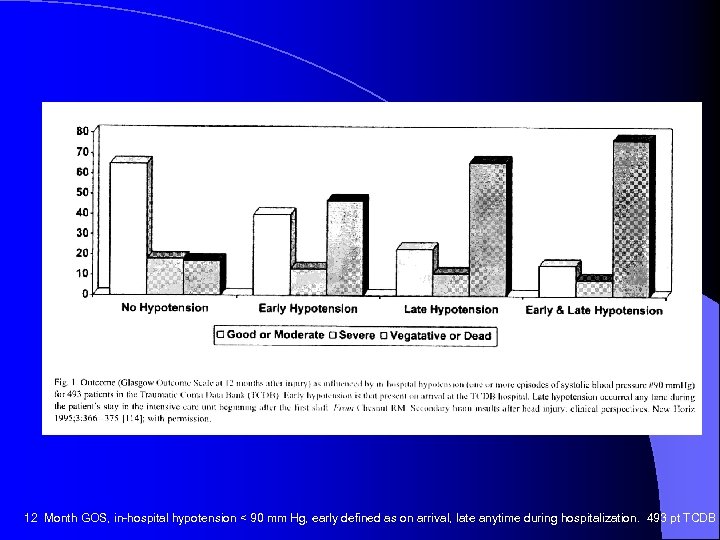

12 Month GOS, in-hospital hypotension < 90 mm Hg, early defined as on arrival, late anytime during hospitalization. 493 pt TCDB

12 Month GOS, in-hospital hypotension < 90 mm Hg, early defined as on arrival, late anytime during hospitalization. 493 pt TCDB

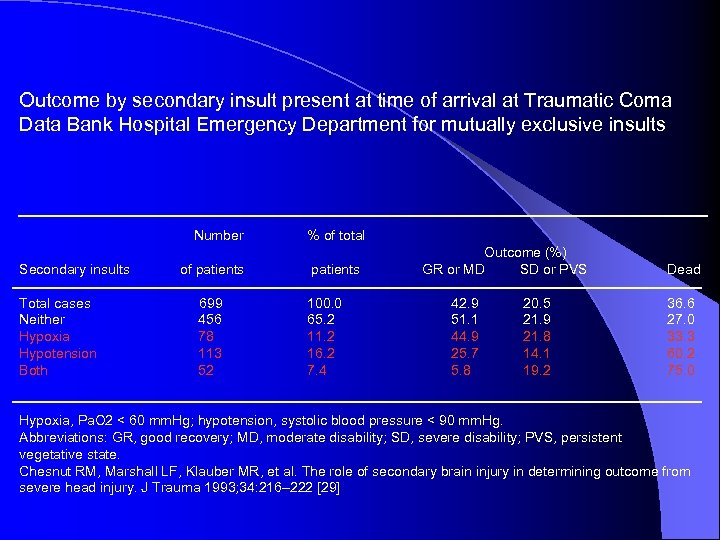

Outcome by secondary insult present at time of arrival at Traumatic Coma Data Bank Hospital Emergency Department for mutually exclusive insults Number Secondary insults Total cases Neither Hypoxia Hypotension Both of patients 699 456 78 113 52 % of total patients 100. 0 65. 2 11. 2 16. 2 7. 4 Outcome (%) GR or MD SD or PVS 42. 9 51. 1 44. 9 25. 7 5. 8 20. 5 21. 9 21. 8 14. 1 19. 2 Dead 36. 6 27. 0 33. 3 60. 2 75. 0 Hypoxia, Pa. O 2 < 60 mm. Hg; hypotension, systolic blood pressure < 90 mm. Hg. Abbreviations: GR, good recovery; MD, moderate disability; SD, severe disability; PVS, persistent vegetative state. Chesnut RM, Marshall LF, Klauber MR, et al. The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. J Trauma 1993; 34: 216– 222 [29]

Outcome by secondary insult present at time of arrival at Traumatic Coma Data Bank Hospital Emergency Department for mutually exclusive insults Number Secondary insults Total cases Neither Hypoxia Hypotension Both of patients 699 456 78 113 52 % of total patients 100. 0 65. 2 11. 2 16. 2 7. 4 Outcome (%) GR or MD SD or PVS 42. 9 51. 1 44. 9 25. 7 5. 8 20. 5 21. 9 21. 8 14. 1 19. 2 Dead 36. 6 27. 0 33. 3 60. 2 75. 0 Hypoxia, Pa. O 2 < 60 mm. Hg; hypotension, systolic blood pressure < 90 mm. Hg. Abbreviations: GR, good recovery; MD, moderate disability; SD, severe disability; PVS, persistent vegetative state. Chesnut RM, Marshall LF, Klauber MR, et al. The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. J Trauma 1993; 34: 216– 222 [29]

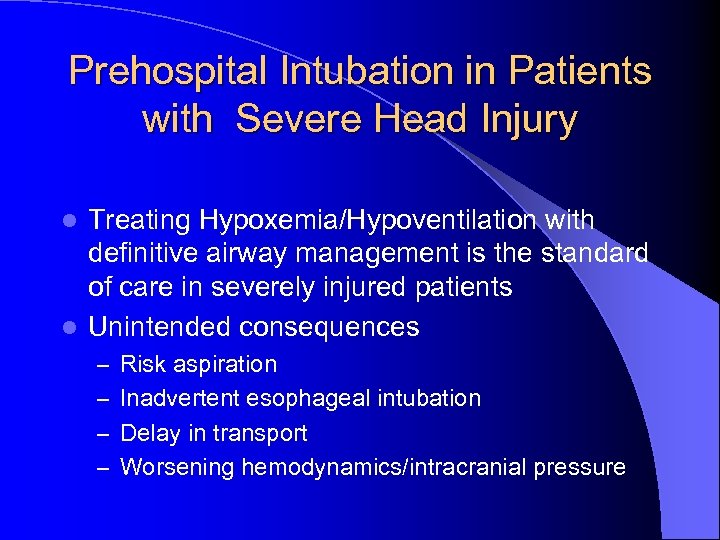

Prehospital Intubation in Patients with Severe Head Injury Treating Hypoxemia/Hypoventilation with definitive airway management is the standard of care in severely injured patients l Unintended consequences l – Risk aspiration – Inadvertent esophageal intubation – Delay in transport – Worsening hemodynamics/intracranial pressure

Prehospital Intubation in Patients with Severe Head Injury Treating Hypoxemia/Hypoventilation with definitive airway management is the standard of care in severely injured patients l Unintended consequences l – Risk aspiration – Inadvertent esophageal intubation – Delay in transport – Worsening hemodynamics/intracranial pressure

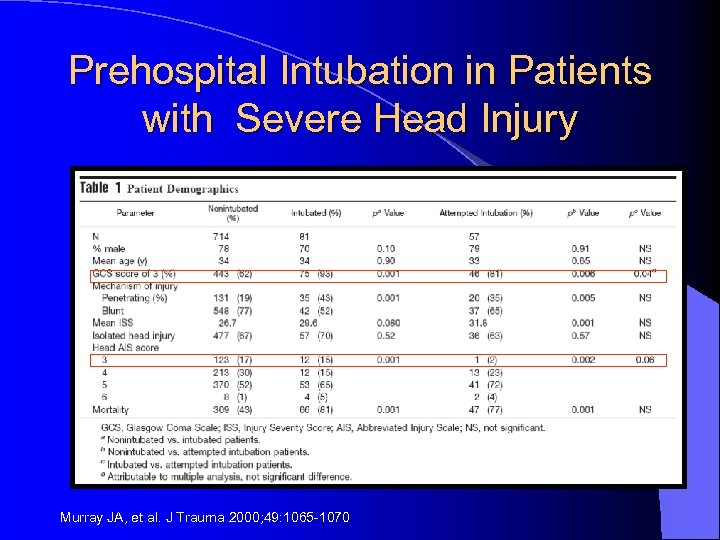

Prehospital Intubation in Patients with Severe Head Injury Murray JA, et al. J Trauma 2000; 49: 1065 -1070

Prehospital Intubation in Patients with Severe Head Injury Murray JA, et al. J Trauma 2000; 49: 1065 -1070

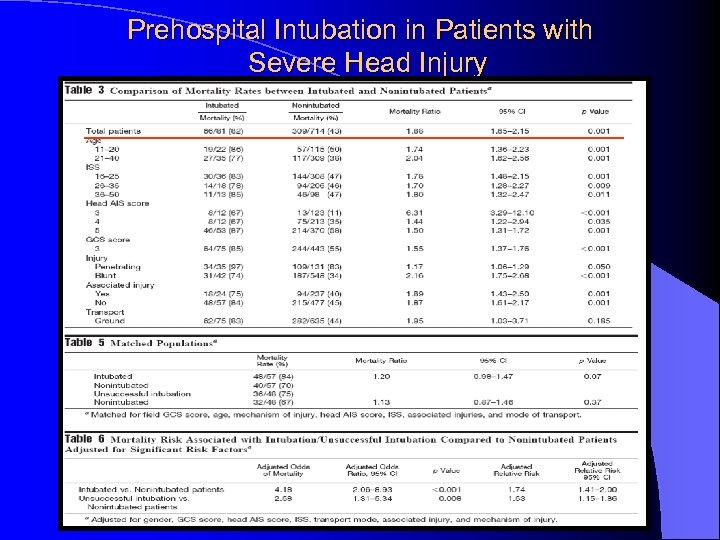

Prehospital Intubation in Patients with Severe Head Injury

Prehospital Intubation in Patients with Severe Head Injury

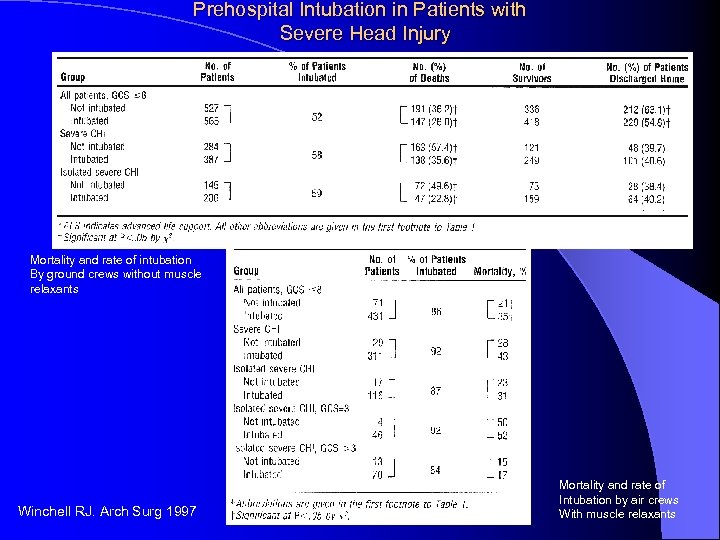

Prehospital Intubation in Patients with Severe Head Injury Mortality and rate of intubation By ground crews without muscle relaxants Winchell RJ. Arch Surg 1997 Mortality and rate of Intubation by air crews With muscle relaxants

Prehospital Intubation in Patients with Severe Head Injury Mortality and rate of intubation By ground crews without muscle relaxants Winchell RJ. Arch Surg 1997 Mortality and rate of Intubation by air crews With muscle relaxants

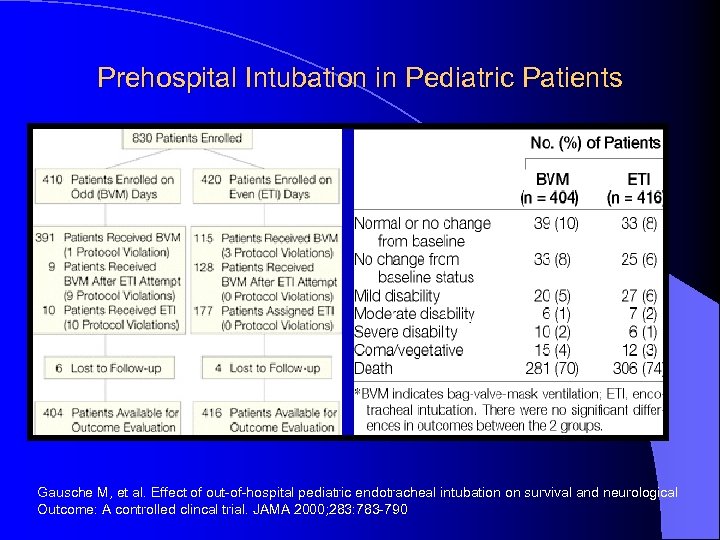

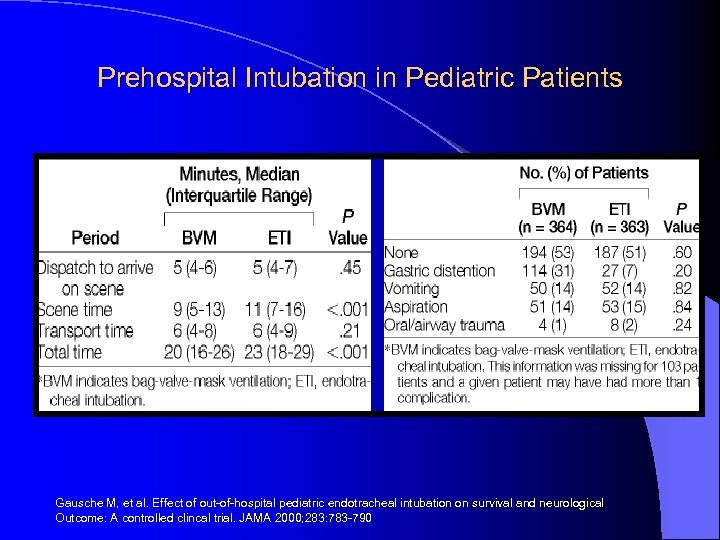

Prehospital Intubation in Pediatric Patients Gausche M, et al. Effect of out-of-hospital pediatric endotracheal intubation on survival and neurological Outcome: A controlled clincal trial. JAMA 2000; 283: 783 -790

Prehospital Intubation in Pediatric Patients Gausche M, et al. Effect of out-of-hospital pediatric endotracheal intubation on survival and neurological Outcome: A controlled clincal trial. JAMA 2000; 283: 783 -790

Prehospital Intubation in Pediatric Patients Gausche M, et al. Effect of out-of-hospital pediatric endotracheal intubation on survival and neurological Outcome: A controlled clincal trial. JAMA 2000; 283: 783 -790

Prehospital Intubation in Pediatric Patients Gausche M, et al. Effect of out-of-hospital pediatric endotracheal intubation on survival and neurological Outcome: A controlled clincal trial. JAMA 2000; 283: 783 -790

Hypothermia in Severe TBI l Beneficial effects first noted by Hippocrates l First Clinical Application 1938 – Terminally ill cancer pts – 80º F (27º C) – Tumor Shrinkage, palliative pain effect l Neuroprotective effects discovered

Hypothermia in Severe TBI l Beneficial effects first noted by Hippocrates l First Clinical Application 1938 – Terminally ill cancer pts – 80º F (27º C) – Tumor Shrinkage, palliative pain effect l Neuroprotective effects discovered

Hypothermia in Severe TBI l Decrease CMR l Maintain ion channels l Decrease neurotransmission l Decrease Ca+ flux l Prevent lipid peroxidation l Maintain blood brain barrier

Hypothermia in Severe TBI l Decrease CMR l Maintain ion channels l Decrease neurotransmission l Decrease Ca+ flux l Prevent lipid peroxidation l Maintain blood brain barrier

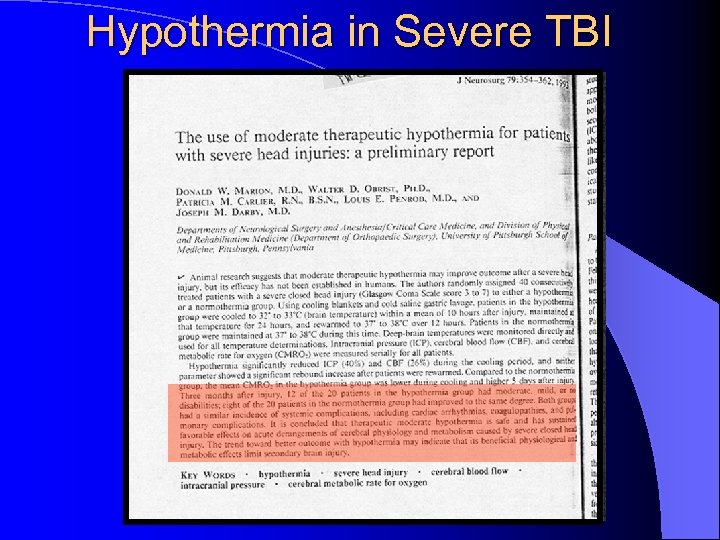

Hypothermia in Severe TBI

Hypothermia in Severe TBI

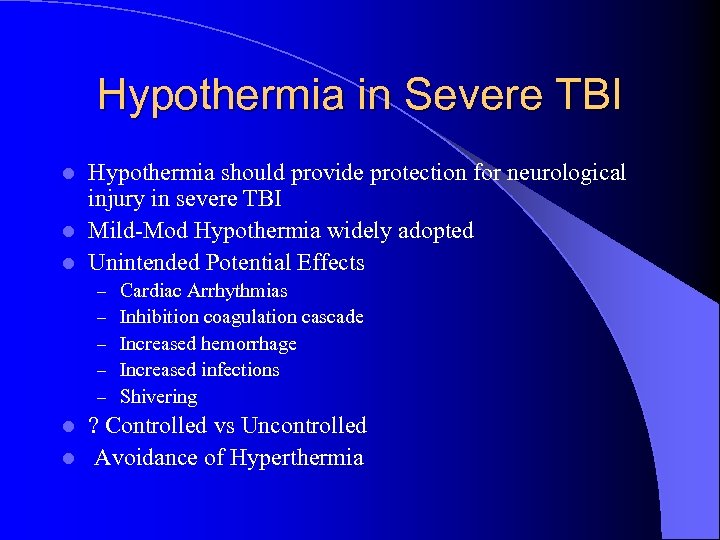

Hypothermia in Severe TBI Hypothermia should provide protection for neurological injury in severe TBI l Mild-Mod Hypothermia widely adopted l Unintended Potential Effects l – – – Cardiac Arrhythmias Inhibition coagulation cascade Increased hemorrhage Increased infections Shivering ? Controlled vs Uncontrolled l Avoidance of Hyperthermia l

Hypothermia in Severe TBI Hypothermia should provide protection for neurological injury in severe TBI l Mild-Mod Hypothermia widely adopted l Unintended Potential Effects l – – – Cardiac Arrhythmias Inhibition coagulation cascade Increased hemorrhage Increased infections Shivering ? Controlled vs Uncontrolled l Avoidance of Hyperthermia l

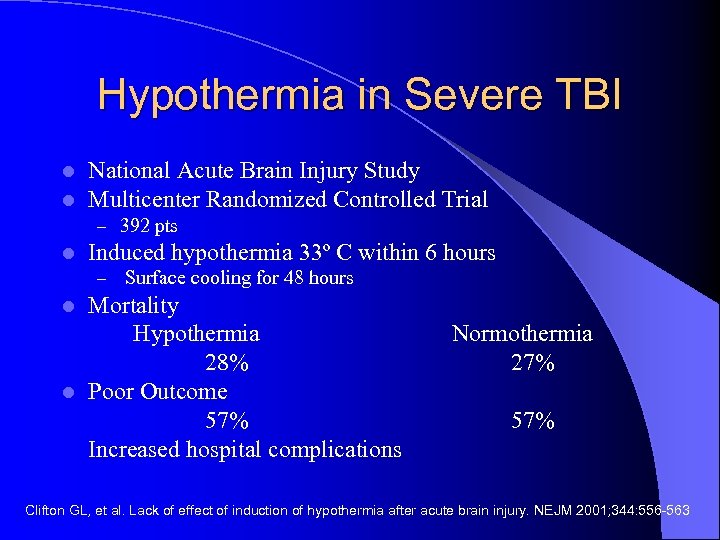

Hypothermia in Severe TBI l l National Acute Brain Injury Study Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial – 392 pts l Induced hypothermia 33º C within 6 hours – Surface cooling for 48 hours Mortality Hypothermia 28% l Poor Outcome 57% Increased hospital complications l Normothermia 27% 57% Clifton GL, et al. Lack of effect of induction of hypothermia after acute brain injury. NEJM 2001; 344: 556 -563

Hypothermia in Severe TBI l l National Acute Brain Injury Study Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial – 392 pts l Induced hypothermia 33º C within 6 hours – Surface cooling for 48 hours Mortality Hypothermia 28% l Poor Outcome 57% Increased hospital complications l Normothermia 27% 57% Clifton GL, et al. Lack of effect of induction of hypothermia after acute brain injury. NEJM 2001; 344: 556 -563

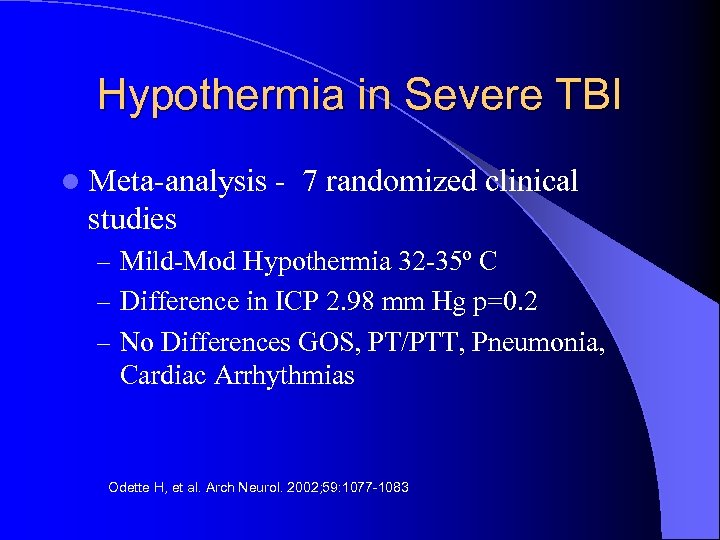

Hypothermia in Severe TBI l Meta-analysis - 7 randomized clinical studies – Mild-Mod Hypothermia 32 -35º C – Difference in ICP 2. 98 mm Hg p=0. 2 – No Differences GOS, PT/PTT, Pneumonia, Cardiac Arrhythmias Odette H, et al. Arch Neurol. 2002; 59: 1077 -1083

Hypothermia in Severe TBI l Meta-analysis - 7 randomized clinical studies – Mild-Mod Hypothermia 32 -35º C – Difference in ICP 2. 98 mm Hg p=0. 2 – No Differences GOS, PT/PTT, Pneumonia, Cardiac Arrhythmias Odette H, et al. Arch Neurol. 2002; 59: 1077 -1083

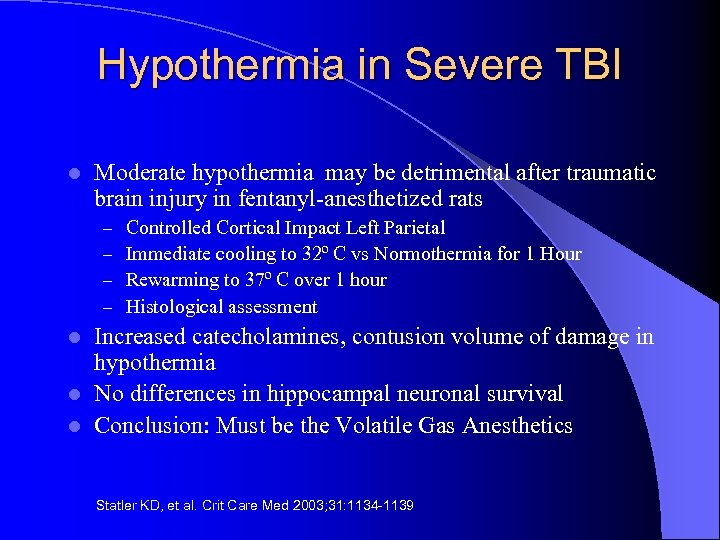

Hypothermia in Severe TBI l Moderate hypothermia may be detrimental after traumatic brain injury in fentanyl-anesthetized rats – – Controlled Cortical Impact Left Parietal Immediate cooling to 32º C vs Normothermia for 1 Hour Rewarming to 37º C over 1 hour Histological assessment Increased catecholamines, contusion volume of damage in hypothermia l No differences in hippocampal neuronal survival l Conclusion: Must be the Volatile Gas Anesthetics l Statler KD, et al. Crit Care Med 2003; 31: 1134 -1139

Hypothermia in Severe TBI l Moderate hypothermia may be detrimental after traumatic brain injury in fentanyl-anesthetized rats – – Controlled Cortical Impact Left Parietal Immediate cooling to 32º C vs Normothermia for 1 Hour Rewarming to 37º C over 1 hour Histological assessment Increased catecholamines, contusion volume of damage in hypothermia l No differences in hippocampal neuronal survival l Conclusion: Must be the Volatile Gas Anesthetics l Statler KD, et al. Crit Care Med 2003; 31: 1134 -1139

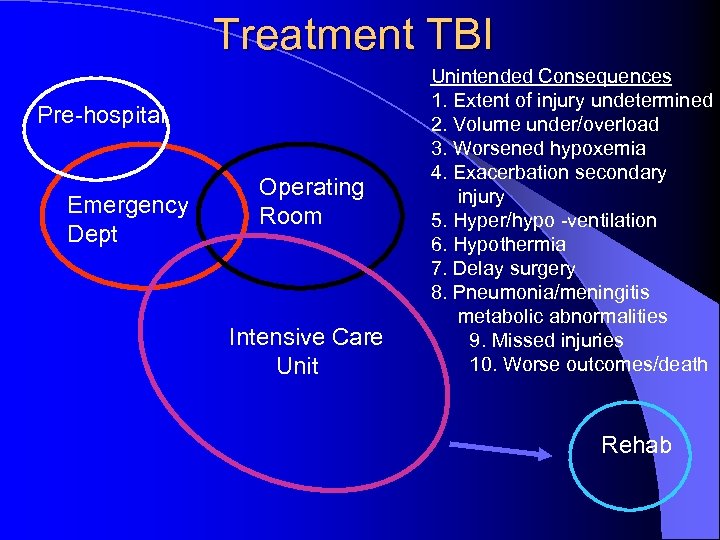

Treatment TBI Pre-hospital Emergency Dept Operating Room Intensive Care Unit Unintended Consequences 1. Extent of injury undetermined 2. Volume under/overload 3. Worsened hypoxemia 4. Exacerbation secondary injury 5. Hyper/hypo -ventilation 6. Hypothermia 7. Delay surgery 8. Pneumonia/meningitis metabolic abnormalities 9. Missed injuries 10. Worse outcomes/death Rehab

Treatment TBI Pre-hospital Emergency Dept Operating Room Intensive Care Unit Unintended Consequences 1. Extent of injury undetermined 2. Volume under/overload 3. Worsened hypoxemia 4. Exacerbation secondary injury 5. Hyper/hypo -ventilation 6. Hypothermia 7. Delay surgery 8. Pneumonia/meningitis metabolic abnormalities 9. Missed injuries 10. Worse outcomes/death Rehab

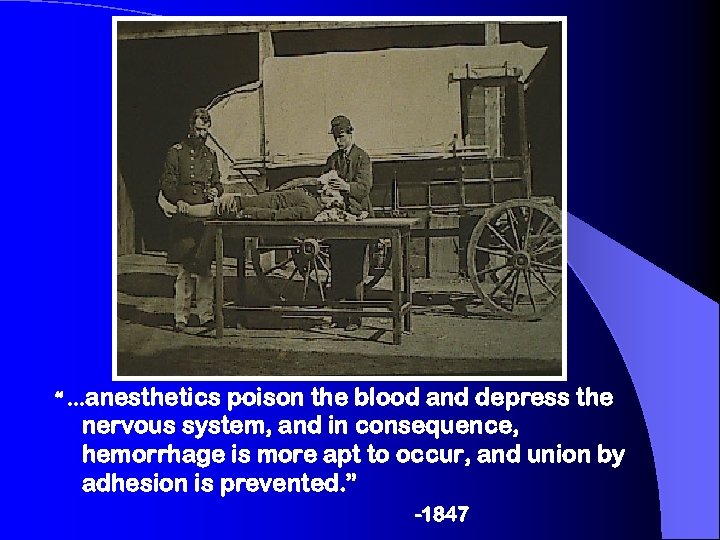

“ …anesthetics poison the blood and depress the nervous system, and in consequence, hemorrhage is more apt to occur, and union by adhesion is prevented. ” -1847

“ …anesthetics poison the blood and depress the nervous system, and in consequence, hemorrhage is more apt to occur, and union by adhesion is prevented. ” -1847

“an ideal method for euthanasia” F. J. Halford

“an ideal method for euthanasia” F. J. Halford

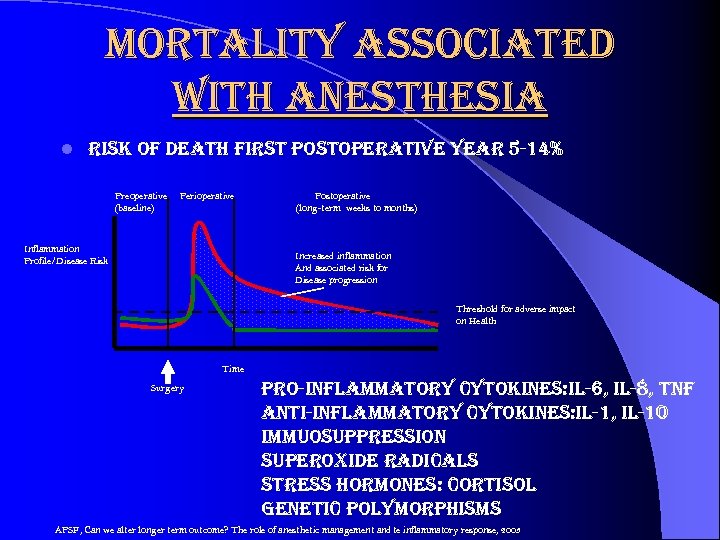

mortality associated with anesthesia l risk of death first postoperative year 5 -14% Preoperative (baseline) Perioperative Inflammation Profile/Disease Risk Postoperative (long-term weeks to months) Increased inflammation And associated risk for Disease progression Threshold for adverse impact on Health Time Surgery pro-inflammatory cytokines: il-6, il-8, tnf anti-inflammatory cytokines: il-1, il-10 immuosuppression superoxide radicals stress hormones: cortisol genetic polymorphisms APSF, Can we alter longer term outcome? The role of anesthetic management and te inflammatory response, 2003

mortality associated with anesthesia l risk of death first postoperative year 5 -14% Preoperative (baseline) Perioperative Inflammation Profile/Disease Risk Postoperative (long-term weeks to months) Increased inflammation And associated risk for Disease progression Threshold for adverse impact on Health Time Surgery pro-inflammatory cytokines: il-6, il-8, tnf anti-inflammatory cytokines: il-1, il-10 immuosuppression superoxide radicals stress hormones: cortisol genetic polymorphisms APSF, Can we alter longer term outcome? The role of anesthetic management and te inflammatory response, 2003

Anesthesia/Perioperative Related Outcomes l Controlling stress response l Glucose Control l Beta-blockade l Clonidine l Post operative/Discharge Nausea l Time to discharge PACU

Anesthesia/Perioperative Related Outcomes l Controlling stress response l Glucose Control l Beta-blockade l Clonidine l Post operative/Discharge Nausea l Time to discharge PACU

mortality associated with anesthesia l preoperative/intraoperative management strategies – – beta blockers avoidance hypothermia intraoperative glucose control statins – ? anesthesia/anesthetics

mortality associated with anesthesia l preoperative/intraoperative management strategies – – beta blockers avoidance hypothermia intraoperative glucose control statins – ? anesthesia/anesthetics

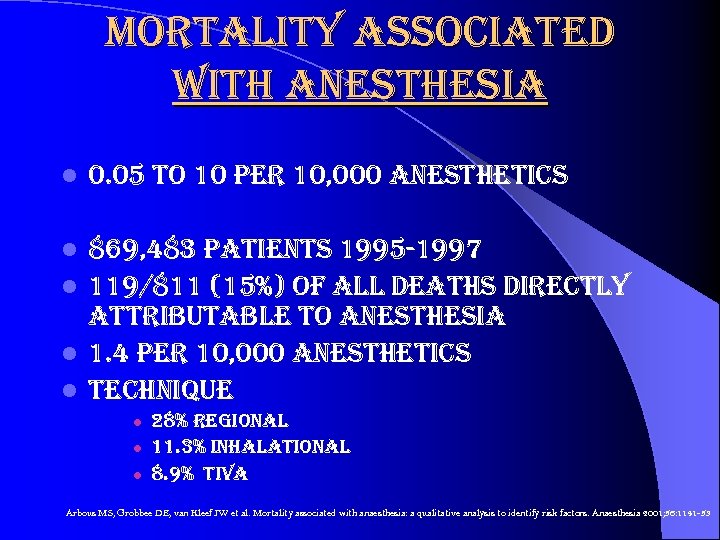

mortality associated with anesthesia l 0. 05 to 10 per 10, 000 anesthetics 869, 483 patients 1995 -1997 l 119/811 (15%) of all deaths directly attributable to anesthesia l 1. 4 per 10, 000 anesthetics l technique l l 28% regional 11. 3% inhalational 8. 9% tiva Arbous MS, Grobbee DE, van Kleef JW et al. Mortality associated with anaesthesia: a qualitative analysis to identify risk factors. Anaesthesia 2001; 56: 1141 -53

mortality associated with anesthesia l 0. 05 to 10 per 10, 000 anesthetics 869, 483 patients 1995 -1997 l 119/811 (15%) of all deaths directly attributable to anesthesia l 1. 4 per 10, 000 anesthetics l technique l l 28% regional 11. 3% inhalational 8. 9% tiva Arbous MS, Grobbee DE, van Kleef JW et al. Mortality associated with anaesthesia: a qualitative analysis to identify risk factors. Anaesthesia 2001; 56: 1141 -53

mortality associated with anesthesia “the impact of this study, should the findings be validated, could result in major changes in how anesthesia is provided, what anesthetics are used, and how hemodynamic variables are controlled during surgery” neal cohen, md, mph, ms Cohen NH. Anesthetic Depth Is Not (Yet) a Predictor of Mortality! Anesthesia and Analgesia 2005; 100: 1 -3

mortality associated with anesthesia “the impact of this study, should the findings be validated, could result in major changes in how anesthesia is provided, what anesthetics are used, and how hemodynamic variables are controlled during surgery” neal cohen, md, mph, ms Cohen NH. Anesthetic Depth Is Not (Yet) a Predictor of Mortality! Anesthesia and Analgesia 2005; 100: 1 -3

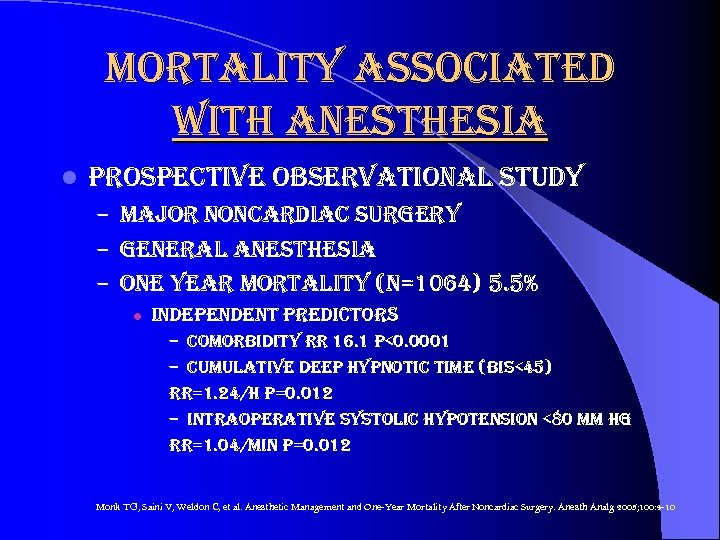

mortality associated with anesthesia l prospective observational study – major noncardiac surgery – general anesthesia – one year mortality (n=1064) 5. 5% l independent predictors – comorbidity rr 16. 1 p<0. 0001 – cumulative deep hypnotic time (bis<45) rr=1. 24/h p=0. 012 – intraoperative systolic hypotension <80 mm hg rr=1. 04/min p=0. 012 Monk TG, Saini V, Weldon C, et al. Anesthetic Management and One-Year Mortality After Noncardiac Surgery. Anesth Analg 2005; 100: 4 -10

mortality associated with anesthesia l prospective observational study – major noncardiac surgery – general anesthesia – one year mortality (n=1064) 5. 5% l independent predictors – comorbidity rr 16. 1 p<0. 0001 – cumulative deep hypnotic time (bis<45) rr=1. 24/h p=0. 012 – intraoperative systolic hypotension <80 mm hg rr=1. 04/min p=0. 012 Monk TG, Saini V, Weldon C, et al. Anesthetic Management and One-Year Mortality After Noncardiac Surgery. Anesth Analg 2005; 100: 4 -10

mortality associated with anesthesia l ? larger doses volatile anesthetics associated with mortality l titration volatiles – movement, bp, hr l l associated with higher doses underutilization adjuvant therapies l adverse effects of countermeasures l ? benefit of reducing exposure

mortality associated with anesthesia l ? larger doses volatile anesthetics associated with mortality l titration volatiles – movement, bp, hr l l associated with higher doses underutilization adjuvant therapies l adverse effects of countermeasures l ? benefit of reducing exposure

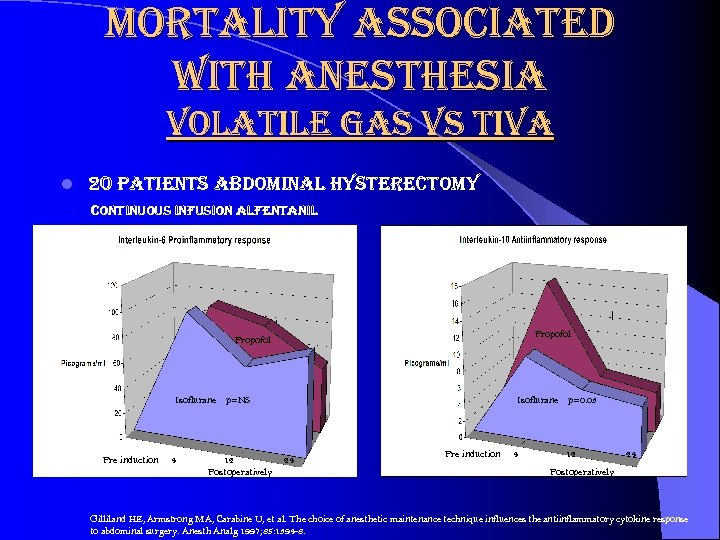

mortality associated with anesthesia volatile gas vs tiva l 20 patients abdominal hysterectomy continuous infusion alfentanil Propofol Isoflurane p=NS Pre induction 4 12 Postoperatively Isoflurane p=0. 03 24 Pre induction 4 12 24 Postoperatively Gilliland HE, Armstrong MA, Carabine U, et al. The choice of anesthetic maintenance technique influences the antiinflammatory cytokine response to abdominal surgery. Anesth Analg 1997; 85: 1394 -8.

mortality associated with anesthesia volatile gas vs tiva l 20 patients abdominal hysterectomy continuous infusion alfentanil Propofol Isoflurane p=NS Pre induction 4 12 Postoperatively Isoflurane p=0. 03 24 Pre induction 4 12 24 Postoperatively Gilliland HE, Armstrong MA, Carabine U, et al. The choice of anesthetic maintenance technique influences the antiinflammatory cytokine response to abdominal surgery. Anesth Analg 1997; 85: 1394 -8.

Anesthesia/Perioperative Related Outcomes Veterans Affairs Medical Centers l NSQIP 1995 -2003 l Infrainguinal arterial bypass compared GETA/Spinal/Epidural l – Increased Graft Failure – Increased Cardiac events with poor functional recovery – Increased pneumonia, return to OR, LOS l Although most common type of anesthetic maybe not best strategy?

Anesthesia/Perioperative Related Outcomes Veterans Affairs Medical Centers l NSQIP 1995 -2003 l Infrainguinal arterial bypass compared GETA/Spinal/Epidural l – Increased Graft Failure – Increased Cardiac events with poor functional recovery – Increased pneumonia, return to OR, LOS l Although most common type of anesthetic maybe not best strategy?

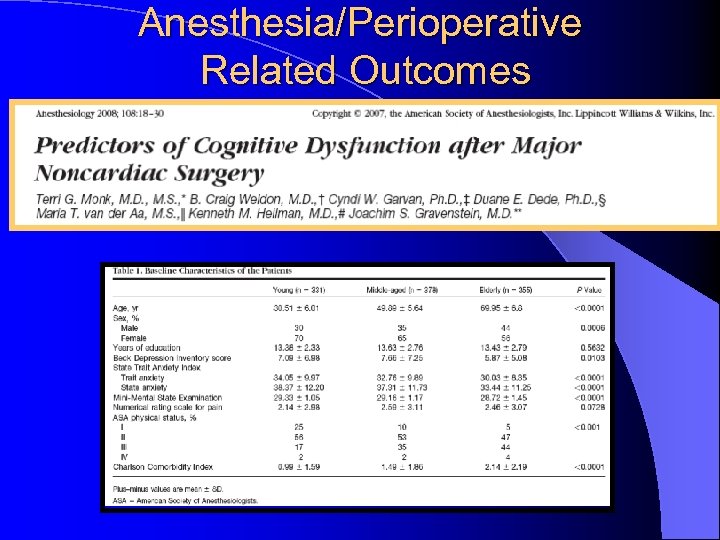

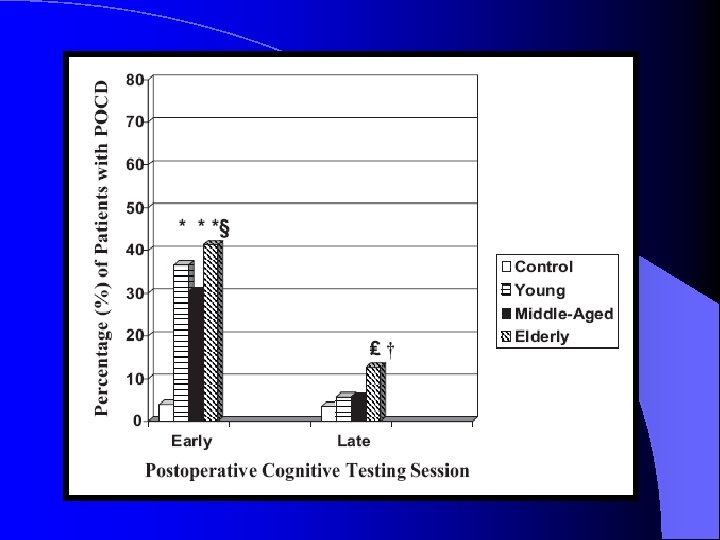

Anesthesia/Perioperative Related Outcomes

Anesthesia/Perioperative Related Outcomes

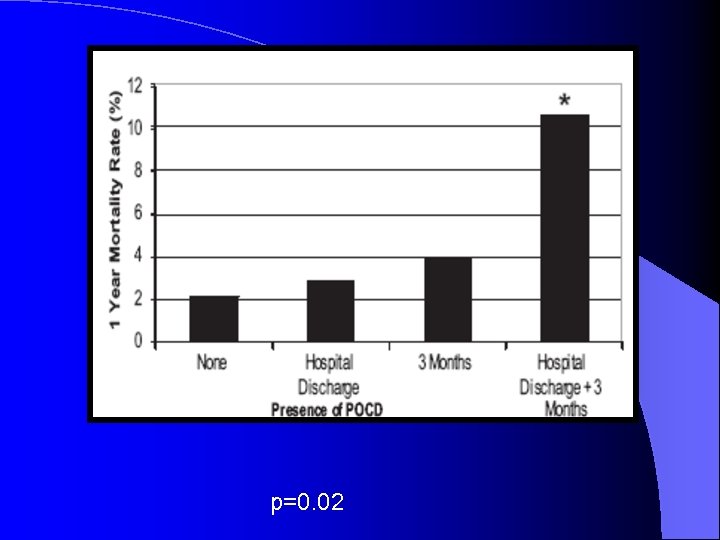

p=0. 02

p=0. 02

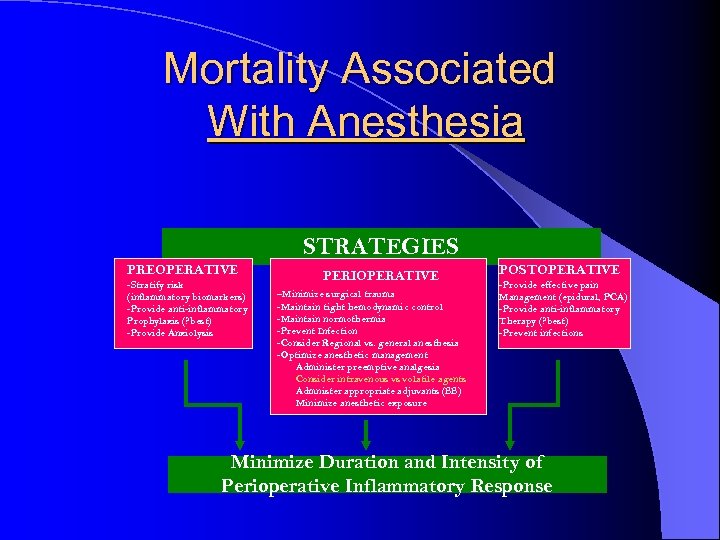

Mortality Associated With Anesthesia STRATEGIES PREOPERATIVE -Stratify risk (inflammatory biomarkers) -Provide anti-inflammatory Prophylaxis (? best) -Provide Anxiolysis PERIOPERATIVE -Minimize surgical trauma -Maintain tight hemodynamic control -Maintain normothermia -Prevent Infection -Consider Regional vs. general anesthesia -Optimize anesthetic management Administer preemptive analgesia Consider intravenous vs volatile agents Admnister appropriate adjuvants (BB) Minimize anesthetic exposure POSTOPERATIVE -Provide effective pain Management (epidural, PCA) -Provide anti-inflammatory Therapy (? best) -Prevent infections Minimize Duration and Intensity of Perioperative Inflammatory Response

Mortality Associated With Anesthesia STRATEGIES PREOPERATIVE -Stratify risk (inflammatory biomarkers) -Provide anti-inflammatory Prophylaxis (? best) -Provide Anxiolysis PERIOPERATIVE -Minimize surgical trauma -Maintain tight hemodynamic control -Maintain normothermia -Prevent Infection -Consider Regional vs. general anesthesia -Optimize anesthetic management Administer preemptive analgesia Consider intravenous vs volatile agents Admnister appropriate adjuvants (BB) Minimize anesthetic exposure POSTOPERATIVE -Provide effective pain Management (epidural, PCA) -Provide anti-inflammatory Therapy (? best) -Prevent infections Minimize Duration and Intensity of Perioperative Inflammatory Response

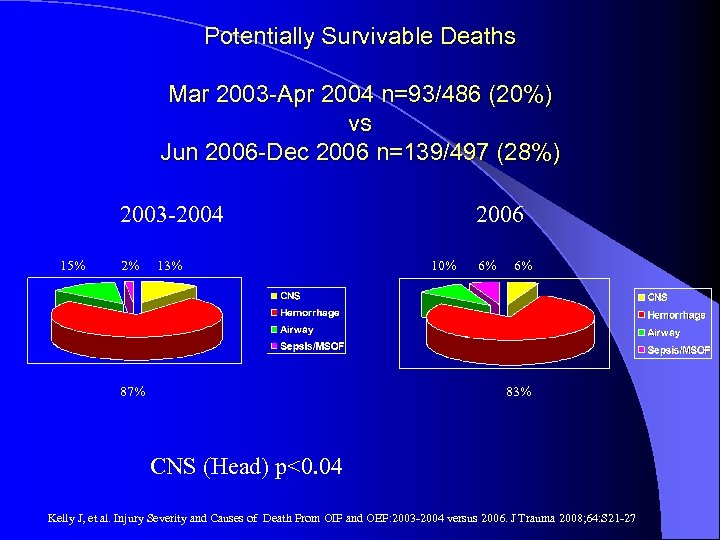

Potentially Survivable Deaths Mar 2003 -Apr 2004 n=93/486 (20%) vs Jun 2006 -Dec 2006 n=139/497 (28%) 2003 -2004 15% 2% 13% 87% 2006 10% 6% 6% 83% CNS (Head) p<0. 04 Kelly J, et al. Injury Severity and Causes of Death From OIF and OEF: 2003 -2004 versus 2006. J Trauma 2008; 64: S 21 -27

Potentially Survivable Deaths Mar 2003 -Apr 2004 n=93/486 (20%) vs Jun 2006 -Dec 2006 n=139/497 (28%) 2003 -2004 15% 2% 13% 87% 2006 10% 6% 6% 83% CNS (Head) p<0. 04 Kelly J, et al. Injury Severity and Causes of Death From OIF and OEF: 2003 -2004 versus 2006. J Trauma 2008; 64: S 21 -27

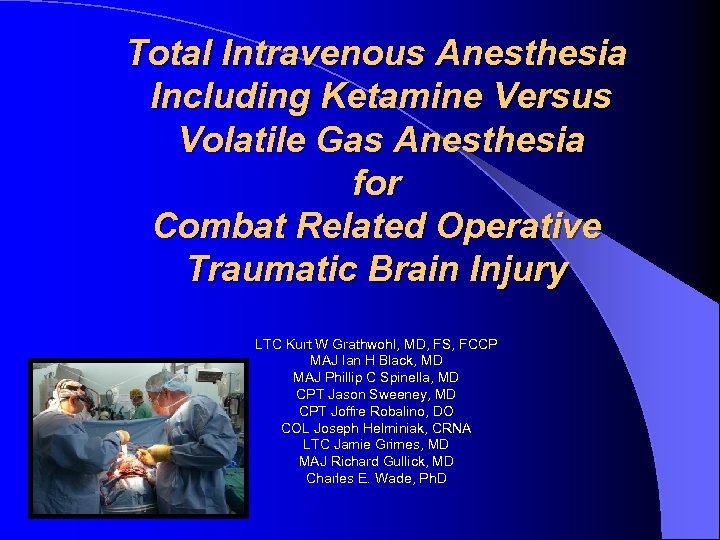

Total Intravenous Anesthesia Including Ketamine Versus Volatile Gas Anesthesia for Combat Related Operative Traumatic Brain Injury LTC Kurt W Grathwohl, MD, FS, FCCP MAJ Ian H Black, MD MAJ Phillip C Spinella, MD CPT Jason Sweeney, MD CPT Joffre Robalino, DO COL Joseph Helminiak, CRNA LTC Jamie Grimes, MD MAJ Richard Gullick, MD Charles E. Wade, Ph. D

Total Intravenous Anesthesia Including Ketamine Versus Volatile Gas Anesthesia for Combat Related Operative Traumatic Brain Injury LTC Kurt W Grathwohl, MD, FS, FCCP MAJ Ian H Black, MD MAJ Phillip C Spinella, MD CPT Jason Sweeney, MD CPT Joffre Robalino, DO COL Joseph Helminiak, CRNA LTC Jamie Grimes, MD MAJ Richard Gullick, MD Charles E. Wade, Ph. D

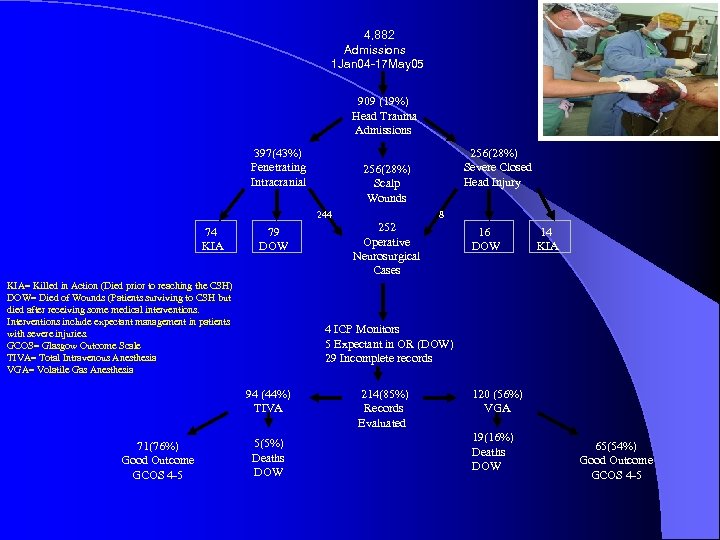

4, 882 Admissions 1 Jan 04 -17 May 05 909 (19%) Head Trauma Admissions 397(43%) Penetrating Intracranial 256(28%) Scalp Wounds 244 74 KIA 79 DOW KIA= Killed in Action (Died prior to reaching the CSH) DOW= Died of Wounds (Patients surviving to CSH but died after receiving some medical interventions. Interventions include expectant management in patients with severe injuries. GCOS= Glasgow Outcome Scale TIVA= Total Intravenous Anesthesia VGA= Volatile Gas Anesthesia 8 252 Operative Neurosurgical Cases 16 DOW 14 KIA 4 ICP Monitors 5 Expectant in OR (DOW) 29 Incomplete records 94 (44%) TIVA 71(76%) Good Outcome GCOS 4 -5 256(28%) Severe Closed Head Injury 5(5%) Deaths DOW 214(85%) Records Evaluated 120 (56%) VGA 19(16%) Deaths DOW 65(54%) Good Outcome GCOS 4 -5

4, 882 Admissions 1 Jan 04 -17 May 05 909 (19%) Head Trauma Admissions 397(43%) Penetrating Intracranial 256(28%) Scalp Wounds 244 74 KIA 79 DOW KIA= Killed in Action (Died prior to reaching the CSH) DOW= Died of Wounds (Patients surviving to CSH but died after receiving some medical interventions. Interventions include expectant management in patients with severe injuries. GCOS= Glasgow Outcome Scale TIVA= Total Intravenous Anesthesia VGA= Volatile Gas Anesthesia 8 252 Operative Neurosurgical Cases 16 DOW 14 KIA 4 ICP Monitors 5 Expectant in OR (DOW) 29 Incomplete records 94 (44%) TIVA 71(76%) Good Outcome GCOS 4 -5 256(28%) Severe Closed Head Injury 5(5%) Deaths DOW 214(85%) Records Evaluated 120 (56%) VGA 19(16%) Deaths DOW 65(54%) Good Outcome GCOS 4 -5

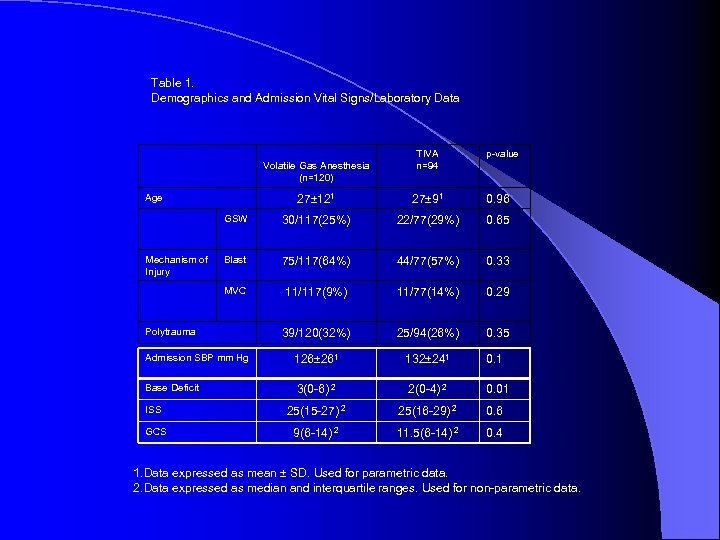

Table 1. Demographics and Admission Vital Signs/Laboratory Data Volatile Gas Anesthesia (n=120) Age TIVA n=94 p-value 27± 121 27± 91 0. 96 GSW 30/117(25%) 22/77(29%) 0. 65 Blast 75/117(64%) 44/77(57%) 0. 33 MVC 11/117(9%) 11/77(14%) 0. 29 39/120(32%) 25/94(26%) 0. 35 Admission SBP mm Hg 126± 261 132± 241 0. 1 Base Deficit 3(0 -6) 2 2(0 -4) 2 0. 01 ISS 25(15 -27) 2 25(16 -29) 2 0. 6 GCS 9(6 -14) 2 11. 5(6 -14) 2 0. 4 Mechanism of Injury Polytrauma 1. Data expressed as mean ± SD. Used for parametric data. 2. Data expressed as median and interquartile ranges. Used for non-parametric data.

Table 1. Demographics and Admission Vital Signs/Laboratory Data Volatile Gas Anesthesia (n=120) Age TIVA n=94 p-value 27± 121 27± 91 0. 96 GSW 30/117(25%) 22/77(29%) 0. 65 Blast 75/117(64%) 44/77(57%) 0. 33 MVC 11/117(9%) 11/77(14%) 0. 29 39/120(32%) 25/94(26%) 0. 35 Admission SBP mm Hg 126± 261 132± 241 0. 1 Base Deficit 3(0 -6) 2 2(0 -4) 2 0. 01 ISS 25(15 -27) 2 25(16 -29) 2 0. 6 GCS 9(6 -14) 2 11. 5(6 -14) 2 0. 4 Mechanism of Injury Polytrauma 1. Data expressed as mean ± SD. Used for parametric data. 2. Data expressed as median and interquartile ranges. Used for non-parametric data.

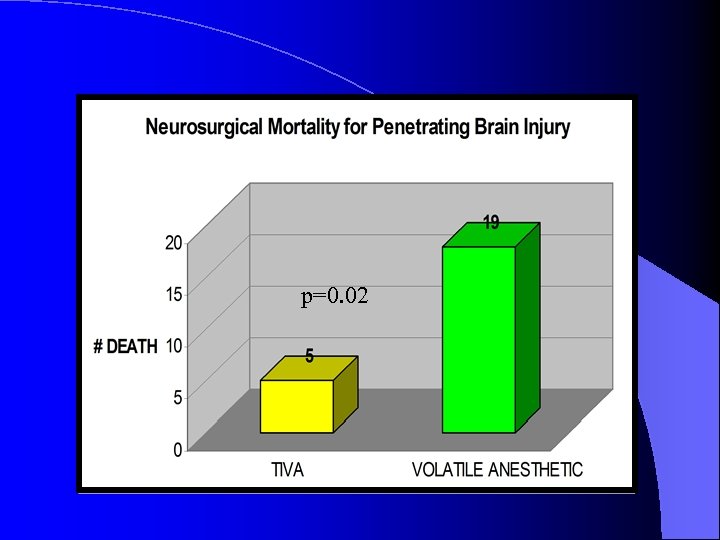

16% p=0. 02 5% n=94 n=120

16% p=0. 02 5% n=94 n=120

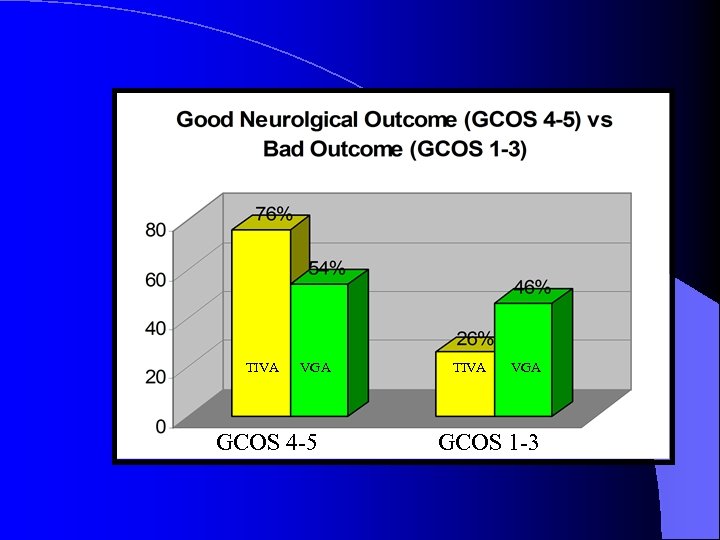

TIVA VGA GCOS 4 -5 TIVA VGA GCOS 1 -3

TIVA VGA GCOS 4 -5 TIVA VGA GCOS 1 -3

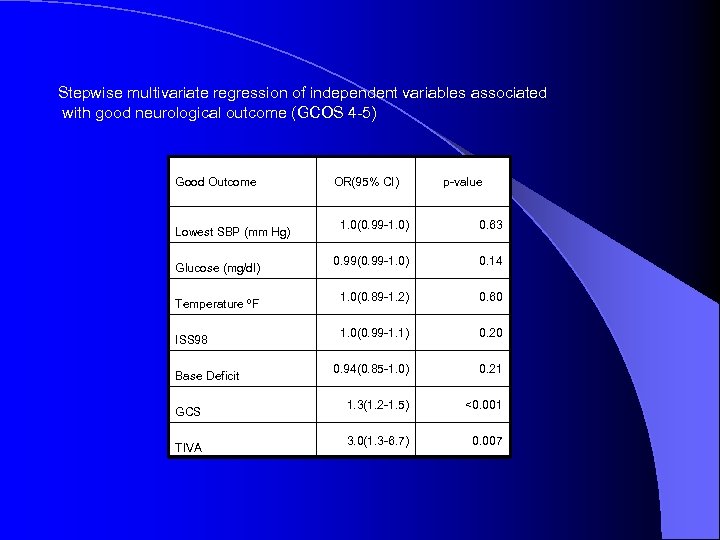

Stepwise multivariate regression of independent variables associated with good neurological outcome (GCOS 4 -5) Good Outcome Lowest SBP (mm Hg) Glucose (mg/dl) Temperature ºF ISS 98 Base Deficit GCS TIVA OR(95% CI) p-value 1. 0(0. 99 -1. 0) 0. 63 0. 99(0. 99 -1. 0) 0. 14 1. 0(0. 89 -1. 2) 0. 60 1. 0(0. 99 -1. 1) 0. 20 0. 94(0. 85 -1. 0) 0. 21 1. 3(1. 2 -1. 5) <0. 001 3. 0(1. 3 -6. 7) 0. 007

Stepwise multivariate regression of independent variables associated with good neurological outcome (GCOS 4 -5) Good Outcome Lowest SBP (mm Hg) Glucose (mg/dl) Temperature ºF ISS 98 Base Deficit GCS TIVA OR(95% CI) p-value 1. 0(0. 99 -1. 0) 0. 63 0. 99(0. 99 -1. 0) 0. 14 1. 0(0. 89 -1. 2) 0. 60 1. 0(0. 99 -1. 1) 0. 20 0. 94(0. 85 -1. 0) 0. 21 1. 3(1. 2 -1. 5) <0. 001 3. 0(1. 3 -6. 7) 0. 007

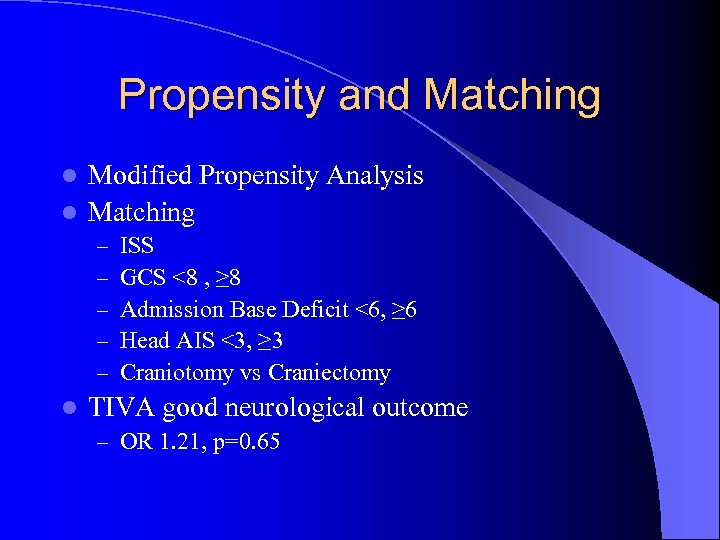

Propensity and Matching Modified Propensity Analysis l Matching l – – – l ISS GCS <8 , ≥ 8 Admission Base Deficit <6, ≥ 6 Head AIS <3, ≥ 3 Craniotomy vs Craniectomy TIVA good neurological outcome – OR 1. 21, p=0. 65

Propensity and Matching Modified Propensity Analysis l Matching l – – – l ISS GCS <8 , ≥ 8 Admission Base Deficit <6, ≥ 6 Head AIS <3, ≥ 3 Craniotomy vs Craniectomy TIVA good neurological outcome – OR 1. 21, p=0. 65

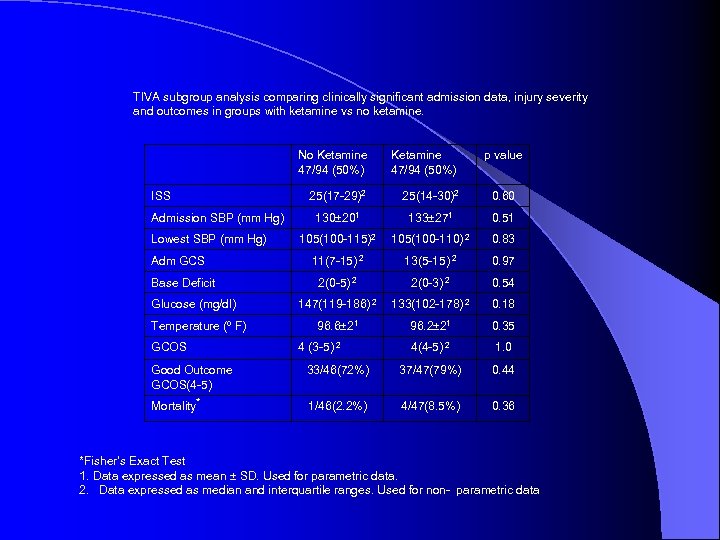

TIVA subgroup analysis comparing clinically significant admission data, injury severity and outcomes in groups with ketamine vs no ketamine. No Ketamine 47/94 (50%) ISS Admission SBP (mm Hg) Lowest SBP (mm Hg) Adm GCS Base Deficit Glucose (mg/dl) Temperature (º F) GCOS Ketamine 47/94 (50%) 25(17 -29)2 25(14 -30)2 0. 60 130± 201 133± 271 0. 51 105(100 -115)2 105(100 -110) 2 0. 83 11(7 -15) 2 13(5 -15) 2 0. 97 2(0 -5) 2 2(0 -3) 2 0. 54 147(119 -186) 2 133(102 -178) 2 0. 18 96. 6± 21 96. 2± 21 0. 35 4(4 -5) 2 1. 0 4 (3 -5) 2 p value Good Outcome GCOS(4 -5) 33/46(72%) 37/47(79%) 0. 44 Mortality* 1/46(2. 2%) 4/47(8. 5%) 0. 36 *Fisher’s Exact Test 1. Data expressed as mean ± SD. Used for parametric data. 2. Data expressed as median and interquartile ranges. Used for non- parametric data

TIVA subgroup analysis comparing clinically significant admission data, injury severity and outcomes in groups with ketamine vs no ketamine. No Ketamine 47/94 (50%) ISS Admission SBP (mm Hg) Lowest SBP (mm Hg) Adm GCS Base Deficit Glucose (mg/dl) Temperature (º F) GCOS Ketamine 47/94 (50%) 25(17 -29)2 25(14 -30)2 0. 60 130± 201 133± 271 0. 51 105(100 -115)2 105(100 -110) 2 0. 83 11(7 -15) 2 13(5 -15) 2 0. 97 2(0 -5) 2 2(0 -3) 2 0. 54 147(119 -186) 2 133(102 -178) 2 0. 18 96. 6± 21 96. 2± 21 0. 35 4(4 -5) 2 1. 0 4 (3 -5) 2 p value Good Outcome GCOS(4 -5) 33/46(72%) 37/47(79%) 0. 44 Mortality* 1/46(2. 2%) 4/47(8. 5%) 0. 36 *Fisher’s Exact Test 1. Data expressed as mean ± SD. Used for parametric data. 2. Data expressed as median and interquartile ranges. Used for non- parametric data

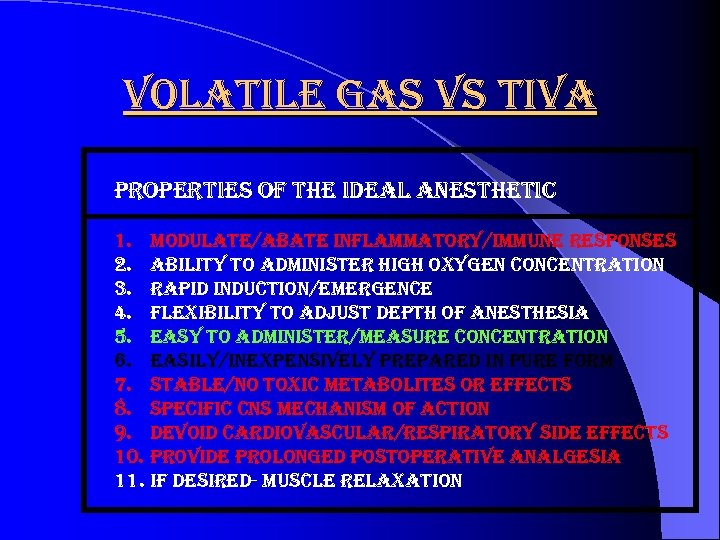

volatile gas vs tiva properties of the ideal anesthetic 1. modulate/abate inflammatory/immune responses 2. ability to administer high oxygen concentration 3. rapid induction/emergence 4. flexibility to adjust depth of anesthesia 5. easy to administer/measure concentration 6. easily/inexpensively prepared in pure form 7. stable/no toxic metabolites or effects 8. specific cns mechanism of action 9. devoid cardiovascular/respiratory side effects 10. provide prolonged postoperative analgesia 11. if desired- muscle relaxation

volatile gas vs tiva properties of the ideal anesthetic 1. modulate/abate inflammatory/immune responses 2. ability to administer high oxygen concentration 3. rapid induction/emergence 4. flexibility to adjust depth of anesthesia 5. easy to administer/measure concentration 6. easily/inexpensively prepared in pure form 7. stable/no toxic metabolites or effects 8. specific cns mechanism of action 9. devoid cardiovascular/respiratory side effects 10. provide prolonged postoperative analgesia 11. if desired- muscle relaxation

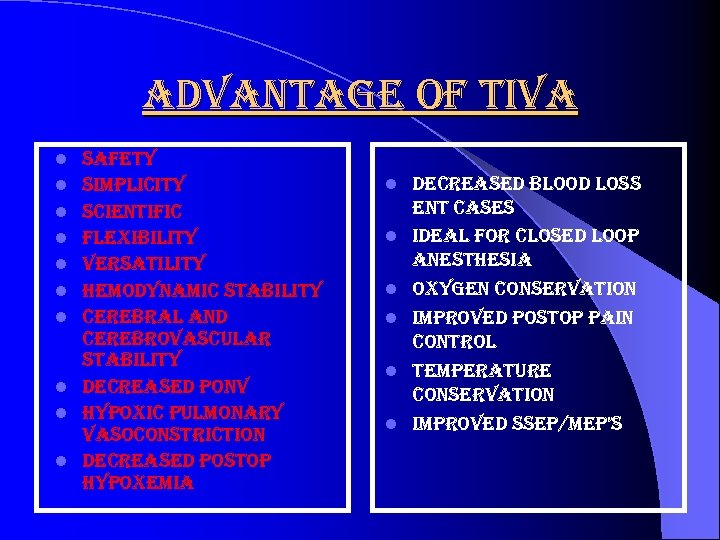

advantage of tiva l l l l l safety simplicity scientific flexibility versatility hemodynamic stability cerebral and cerebrovascular stability decreased ponv hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction decreased postop hypoxemia l l l decreased blood loss ent cases ideal for closed loop anesthesia oxygen conservation improved postop pain control temperature conservation improved ssep/mep’s

advantage of tiva l l l l l safety simplicity scientific flexibility versatility hemodynamic stability cerebral and cerebrovascular stability decreased ponv hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction decreased postop hypoxemia l l l decreased blood loss ent cases ideal for closed loop anesthesia oxygen conservation improved postop pain control temperature conservation improved ssep/mep’s

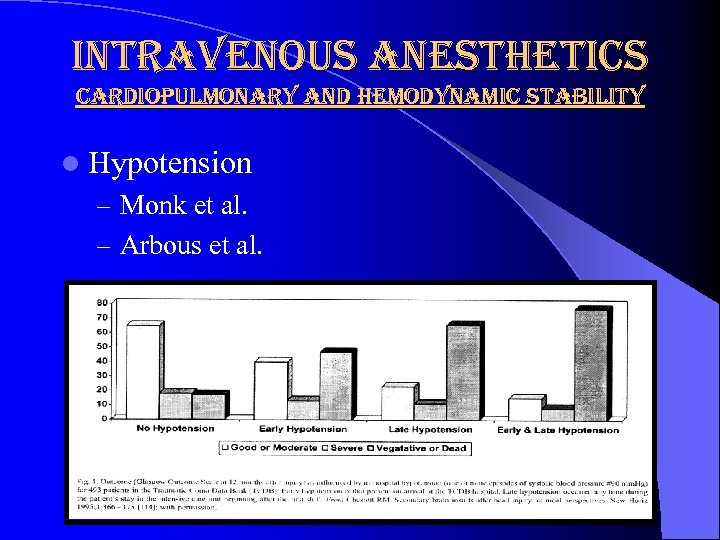

intravenous anesthetics cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic stability l Hypotension – Monk et al. – Arbous et al.

intravenous anesthetics cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic stability l Hypotension – Monk et al. – Arbous et al.

intravenous anesthetics cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic stability l anesthetic agent or technique may not be as important as the anesthetic management l anesthetic management – – adequate oxygenation ventilation tissue perfusion avoidance hypotension

intravenous anesthetics cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic stability l anesthetic agent or technique may not be as important as the anesthetic management l anesthetic management – – adequate oxygenation ventilation tissue perfusion avoidance hypotension

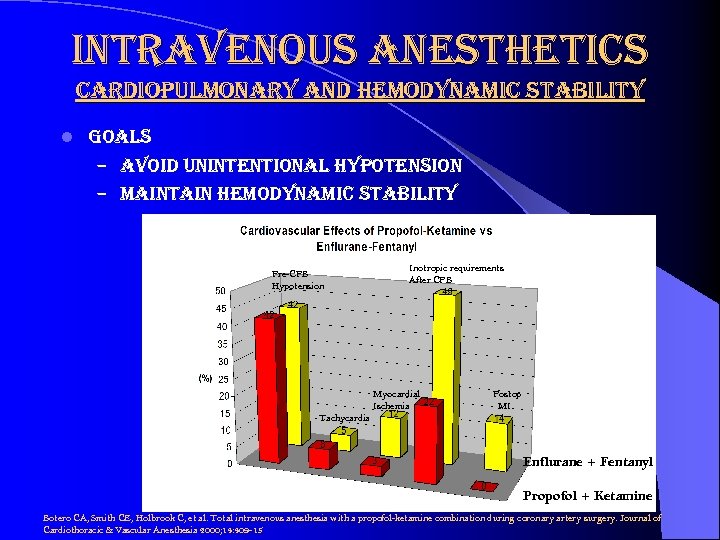

intravenous anesthetics cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic stability l goals – avoid unintentional hypotension – maintain hemodynamic stability Pre-CPB Hypotension Inotropic requirements After CPB Myocardial Ischemia Postop MI Tachycardia Enflurane + Fentanyl Propofol + Ketamine Botero CA, Smith CE, Holbrook C, et al. Total intravenous anesthesia with a propofol-ketamine combination during coronary artery surgery. Journal of Cardiothoracic & Vascular Anesthesia 2000; 14: 409 -15

intravenous anesthetics cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic stability l goals – avoid unintentional hypotension – maintain hemodynamic stability Pre-CPB Hypotension Inotropic requirements After CPB Myocardial Ischemia Postop MI Tachycardia Enflurane + Fentanyl Propofol + Ketamine Botero CA, Smith CE, Holbrook C, et al. Total intravenous anesthesia with a propofol-ketamine combination during coronary artery surgery. Journal of Cardiothoracic & Vascular Anesthesia 2000; 14: 409 -15

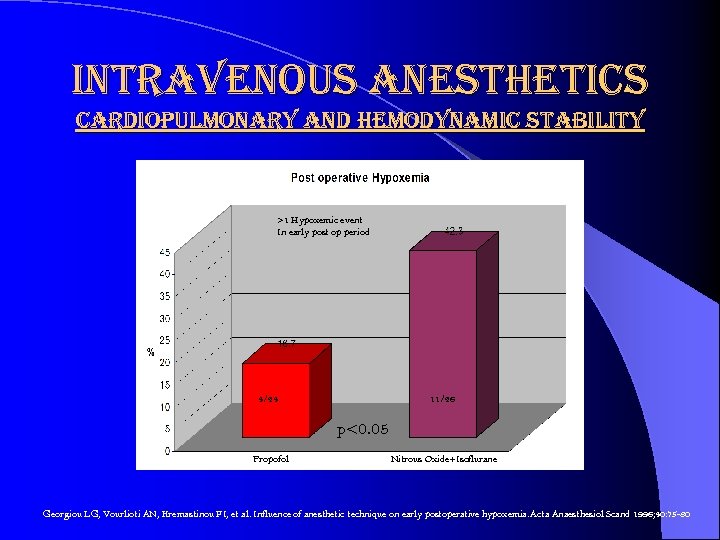

intravenous anesthetics cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic stability >1 Hypoxemic event In early post op period 4/24 11/26 p<0. 05 Propofol Nitrous Oxide+Isoflurane Georgiou LG, Vourlioti AN, Kremastinou FI, et al. Influence of anesthetic technique on early postoperative hypoxemia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1996; 40: 75 -80

intravenous anesthetics cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic stability >1 Hypoxemic event In early post op period 4/24 11/26 p<0. 05 Propofol Nitrous Oxide+Isoflurane Georgiou LG, Vourlioti AN, Kremastinou FI, et al. Influence of anesthetic technique on early postoperative hypoxemia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1996; 40: 75 -80

intravenous anesthetics cerebral and cerebrovascular stability – hemodynamic stability – intracranial pressure – cerebral blood flow – cerebrovascular autoregulation – cerebral oxygen consumption – avoid respiratory depression

intravenous anesthetics cerebral and cerebrovascular stability – hemodynamic stability – intracranial pressure – cerebral blood flow – cerebrovascular autoregulation – cerebral oxygen consumption – avoid respiratory depression

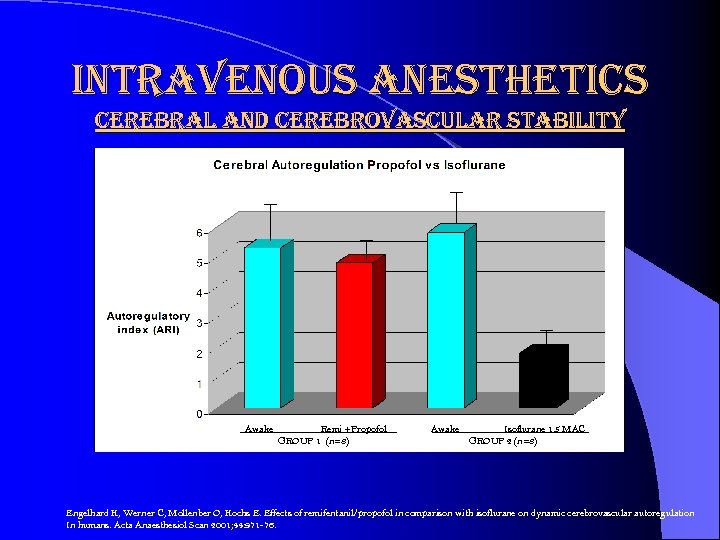

intravenous anesthetics cerebral and cerebrovascular stability Awake Remi +Propofol GROUP 1 (n=8) Awake Isoflurane 1. 5 MAC GROUP 2 (n=8) Engelhard K, Werner C, Mollenber O, Kochs E. Effects of remifentanil/propofol in comparison with isoflurane on dynamic cerebrovascular autoregulation In humans. Acta Anaesthesiol Scan 2001; 44: 971 -76.

intravenous anesthetics cerebral and cerebrovascular stability Awake Remi +Propofol GROUP 1 (n=8) Awake Isoflurane 1. 5 MAC GROUP 2 (n=8) Engelhard K, Werner C, Mollenber O, Kochs E. Effects of remifentanil/propofol in comparison with isoflurane on dynamic cerebrovascular autoregulation In humans. Acta Anaesthesiol Scan 2001; 44: 971 -76.

intravenous anesthetics postoperative nausea and vomiting 30 -40% patients l worse than surgical pain l increased l – resource utilization – recovery time – hospitalization – cost l complications – suture dehiscence – esophageal rupture – subcutaneous emphysema – pneumothorax – pulmonary aspiration – increased icp – increased iop – wound bleeding/hematoma

intravenous anesthetics postoperative nausea and vomiting 30 -40% patients l worse than surgical pain l increased l – resource utilization – recovery time – hospitalization – cost l complications – suture dehiscence – esophageal rupture – subcutaneous emphysema – pneumothorax – pulmonary aspiration – increased icp – increased iop – wound bleeding/hematoma

disadvantages/unknowns associated with tiva l l l l l outcomes training depth anesthesia drug levels during hemorrhage increased incidence atrial fib propofol syndrome complexity dosing/drug regimens intraoperative awareness allergic reactions lipid emulsions immunosuppressive

disadvantages/unknowns associated with tiva l l l l l outcomes training depth anesthesia drug levels during hemorrhage increased incidence atrial fib propofol syndrome complexity dosing/drug regimens intraoperative awareness allergic reactions lipid emulsions immunosuppressive

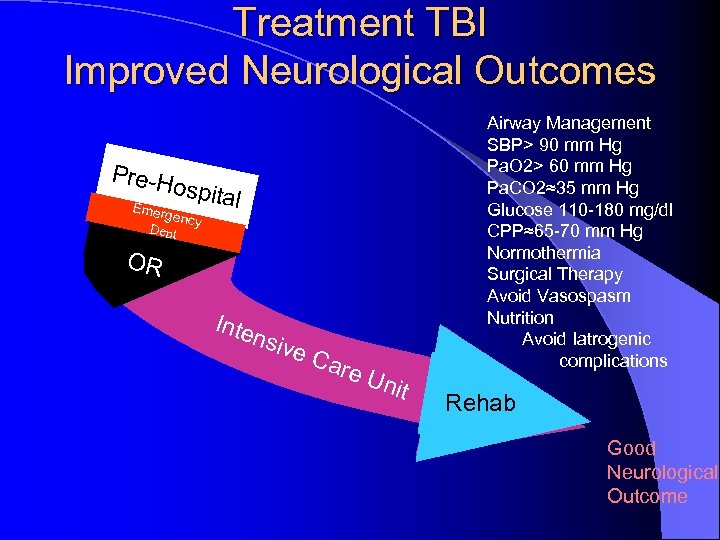

Treatment TBI Improved Neurological Outcomes Pre-H Airway Management SBP> 90 mm Hg Pa. O 2> 60 mm Hg Pa. CO 2≈35 mm Hg Glucose 110 -180 mg/dl CPP≈65 -70 mm Hg Normothermia Surgical Therapy Avoid Vasospasm Nutrition Avoid Iatrogenic complications ospita Emerg ency Dept l OR Inte nsiv e. C are Uni t Rehab Good Neurological Outcome

Treatment TBI Improved Neurological Outcomes Pre-H Airway Management SBP> 90 mm Hg Pa. O 2> 60 mm Hg Pa. CO 2≈35 mm Hg Glucose 110 -180 mg/dl CPP≈65 -70 mm Hg Normothermia Surgical Therapy Avoid Vasospasm Nutrition Avoid Iatrogenic complications ospita Emerg ency Dept l OR Inte nsiv e. C are Uni t Rehab Good Neurological Outcome