bb758c130de43f5a7f46f9662eca6e58.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 90

Logical Program Specification and Testing Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and Fraunhofer FIRST, Berlin, Germany SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009

Logical Program Specification and Testing Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and Fraunhofer FIRST, Berlin, Germany SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009

Plan for Today • Terms and definitions • Propositional modelling • Testing problems • Topics in testing • First-order formalisms, Z • Functional (unit) testing and test selection • Structural testing and test coverage • Model-based test generation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 2

Plan for Today • Terms and definitions • Propositional modelling • Testing problems • Topics in testing • First-order formalisms, Z • Functional (unit) testing and test selection • Structural testing and test coverage • Model-based test generation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 2

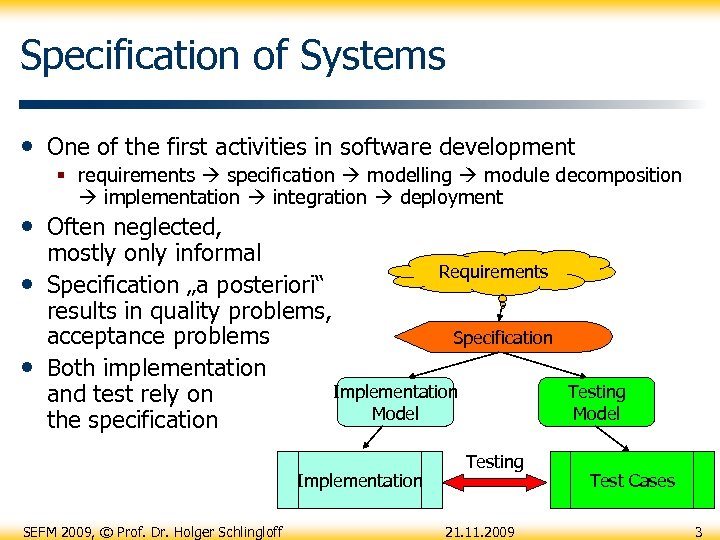

Specification of Systems • One of the first activities in software development § requirements specification modelling module decomposition implementation integration deployment • Often neglected, • • mostly only informal Requirements Specification „a posteriori“ results in quality problems, Specification acceptance problems Both implementation Implementation and test rely on Model the specification Implementation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff Testing 21. 11. 2009 Testing Model Test Cases 3

Specification of Systems • One of the first activities in software development § requirements specification modelling module decomposition implementation integration deployment • Often neglected, • • mostly only informal Requirements Specification „a posteriori“ results in quality problems, Specification acceptance problems Both implementation Implementation and test rely on Model the specification Implementation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff Testing 21. 11. 2009 Testing Model Test Cases 3

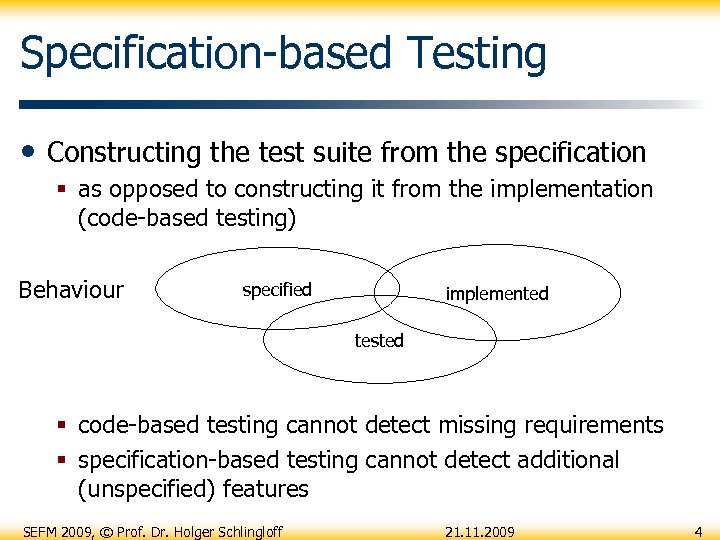

Specification-based Testing • Constructing the test suite from the specification § as opposed to constructing it from the implementation (code-based testing) Behaviour specified implemented tested § code-based testing cannot detect missing requirements § specification-based testing cannot detect additional (unspecified) features SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 4

Specification-based Testing • Constructing the test suite from the specification § as opposed to constructing it from the implementation (code-based testing) Behaviour specified implemented tested § code-based testing cannot detect missing requirements § specification-based testing cannot detect additional (unspecified) features SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 4

VVT: Validation, Verification, Testing Trying to answer different questions • Testing: Did we build the software right? • Validation: Did we build the right software? • Verification: Can we show that the software is correct? • Dijkstra: “Testing can only show the presence of bugs, not • their absence. ” Hoare (attributed): “Beware of this program. I haven’t tried it yet, I only proved its correctness. ” Consider two airplanes: One brand new, with verified but untested software. The other one with software which is thoroughly tested but not verified. Which one would you enter? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 5

VVT: Validation, Verification, Testing Trying to answer different questions • Testing: Did we build the software right? • Validation: Did we build the right software? • Verification: Can we show that the software is correct? • Dijkstra: “Testing can only show the presence of bugs, not • their absence. ” Hoare (attributed): “Beware of this program. I haven’t tried it yet, I only proved its correctness. ” Consider two airplanes: One brand new, with verified but untested software. The other one with software which is thoroughly tested but not verified. Which one would you enter? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 5

Implementation and Testing • “Programmer” and “Tester” are fundamentally different roles § programmer wants to show correctness of his creation § tester has the task to find errors, i. e. testing is successful if it uncovers deficiencies • “Programmer” and “Tester” are essentially similar roles § programmer creates executable artefacts (programs) from specifications § tester creates executable artefacts (test suites) from specifications SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 6

Implementation and Testing • “Programmer” and “Tester” are fundamentally different roles § programmer wants to show correctness of his creation § tester has the task to find errors, i. e. testing is successful if it uncovers deficiencies • “Programmer” and “Tester” are essentially similar roles § programmer creates executable artefacts (programs) from specifications § tester creates executable artefacts (test suites) from specifications SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 6

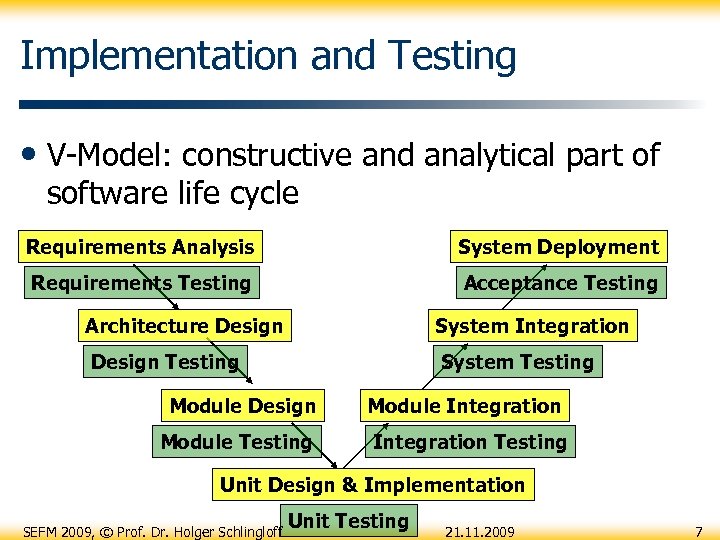

Implementation and Testing • V-Model: constructive and analytical part of software life cycle Requirements Analysis System Deployment Requirements Testing Acceptance Testing Architecture Design System Integration Design Testing System Testing Module Design Module Testing Module Integration Testing Unit Design & Implementation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff Unit Testing 21. 11. 2009 7

Implementation and Testing • V-Model: constructive and analytical part of software life cycle Requirements Analysis System Deployment Requirements Testing Acceptance Testing Architecture Design System Integration Design Testing System Testing Module Design Module Testing Module Integration Testing Unit Design & Implementation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff Unit Testing 21. 11. 2009 7

Topics in Testing • • • What is the specification, what is the SUT? Which interfaces to the SUT are needed? (Harness) What is the testing objective? (Purpose, Conditions) How are test cases derived? (Test case generation) How can the verdict be assigned? (Test oracle) How to write down test cases? (Testing languages) When is a test suite sufficient for the objective? (Test strategy) How are test cases executed? (Testing environment) When to stop testing? (Test coverage) How to reuse test results for subsequent activities? (Regression testing) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 8

Topics in Testing • • • What is the specification, what is the SUT? Which interfaces to the SUT are needed? (Harness) What is the testing objective? (Purpose, Conditions) How are test cases derived? (Test case generation) How can the verdict be assigned? (Test oracle) How to write down test cases? (Testing languages) When is a test suite sufficient for the objective? (Test strategy) How are test cases executed? (Testing environment) When to stop testing? (Test coverage) How to reuse test results for subsequent activities? (Regression testing) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 8

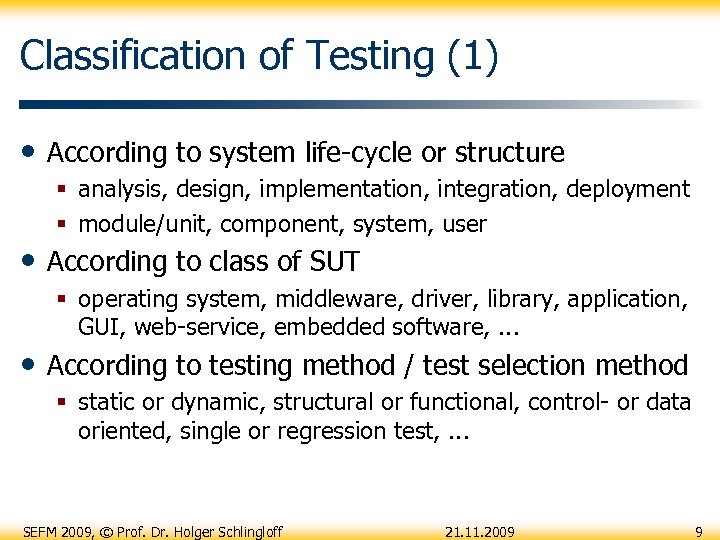

Classification of Testing (1) • According to system life-cycle or structure § analysis, design, implementation, integration, deployment § module/unit, component, system, user • According to class of SUT § operating system, middleware, driver, library, application, GUI, web-service, embedded software, . . . • According to testing method / test selection method § static or dynamic, structural or functional, control- or data oriented, single or regression test, . . . SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 9

Classification of Testing (1) • According to system life-cycle or structure § analysis, design, implementation, integration, deployment § module/unit, component, system, user • According to class of SUT § operating system, middleware, driver, library, application, GUI, web-service, embedded software, . . . • According to testing method / test selection method § static or dynamic, structural or functional, control- or data oriented, single or regression test, . . . SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 9

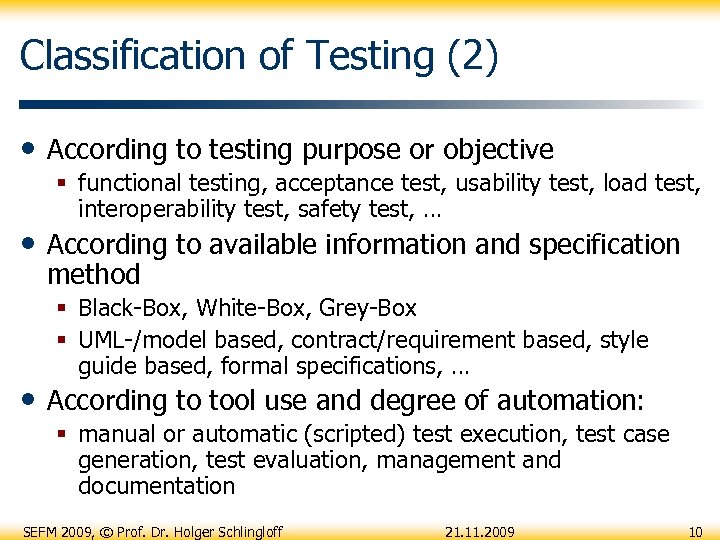

Classification of Testing (2) • According to testing purpose or objective § functional testing, acceptance test, usability test, load test, interoperability test, safety test, … • According to available information and specification method § Black-Box, White-Box, Grey-Box § UML-/model based, contract/requirement based, style guide based, formal specifications, … • According to tool use and degree of automation: § manual or automatic (scripted) test execution, test case generation, test evaluation, management and documentation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 10

Classification of Testing (2) • According to testing purpose or objective § functional testing, acceptance test, usability test, load test, interoperability test, safety test, … • According to available information and specification method § Black-Box, White-Box, Grey-Box § UML-/model based, contract/requirement based, style guide based, formal specifications, … • According to tool use and degree of automation: § manual or automatic (scripted) test execution, test case generation, test evaluation, management and documentation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 10

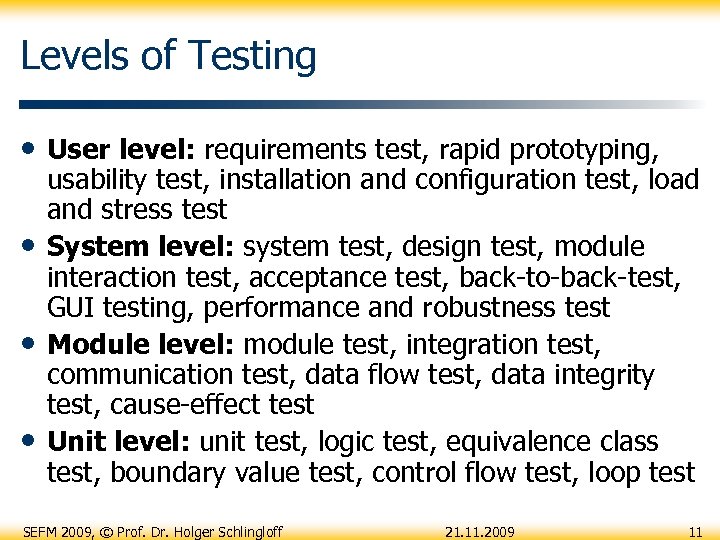

Levels of Testing • User level: requirements test, rapid prototyping, • • • usability test, installation and configuration test, load and stress test System level: system test, design test, module interaction test, acceptance test, back-to-back-test, GUI testing, performance and robustness test Module level: module test, integration test, communication test, data flow test, data integrity test, cause-effect test Unit level: unit test, logic test, equivalence class test, boundary value test, control flow test, loop test SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 11

Levels of Testing • User level: requirements test, rapid prototyping, • • • usability test, installation and configuration test, load and stress test System level: system test, design test, module interaction test, acceptance test, back-to-back-test, GUI testing, performance and robustness test Module level: module test, integration test, communication test, data flow test, data integrity test, cause-effect test Unit level: unit test, logic test, equivalence class test, boundary value test, control flow test, loop test SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 11

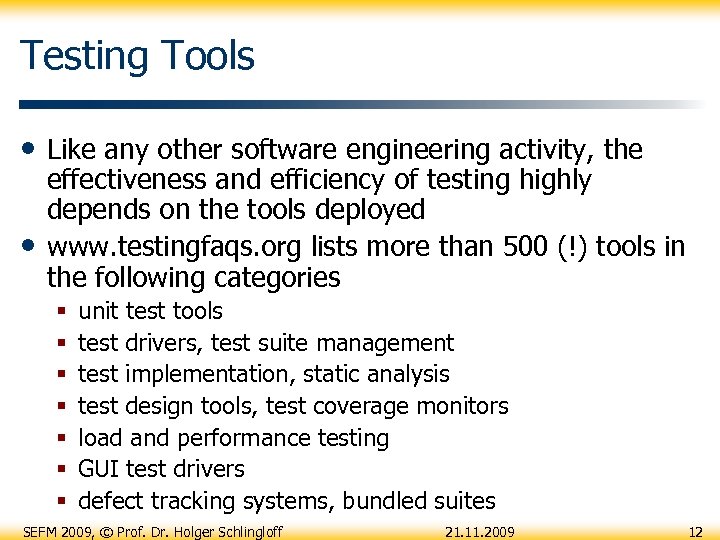

Testing Tools • Like any other software engineering activity, the • effectiveness and efficiency of testing highly depends on the tools deployed www. testingfaqs. org lists more than 500 (!) tools in the following categories § § § § unit test tools test drivers, test suite management test implementation, static analysis test design tools, test coverage monitors load and performance testing GUI test drivers defect tracking systems, bundled suites SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 12

Testing Tools • Like any other software engineering activity, the • effectiveness and efficiency of testing highly depends on the tools deployed www. testingfaqs. org lists more than 500 (!) tools in the following categories § § § § unit test tools test drivers, test suite management test implementation, static analysis test design tools, test coverage monitors load and performance testing GUI test drivers defect tracking systems, bundled suites SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 12

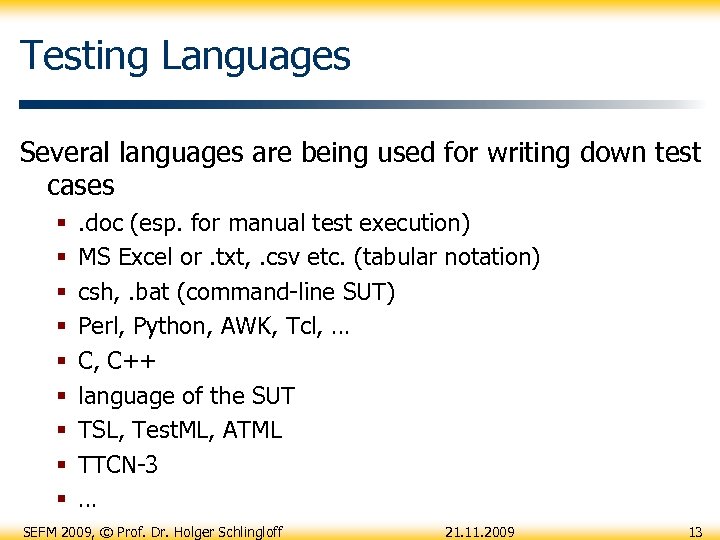

Testing Languages Several languages are being used for writing down test cases § § § § § . doc (esp. for manual test execution) MS Excel or. txt, . csv etc. (tabular notation) csh, . bat (command-line SUT) Perl, Python, AWK, Tcl, … C, C++ language of the SUT TSL, Test. ML, ATML TTCN-3 … SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 13

Testing Languages Several languages are being used for writing down test cases § § § § § . doc (esp. for manual test execution) MS Excel or. txt, . csv etc. (tabular notation) csh, . bat (command-line SUT) Perl, Python, AWK, Tcl, … C, C++ language of the SUT TSL, Test. ML, ATML TTCN-3 … SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 13

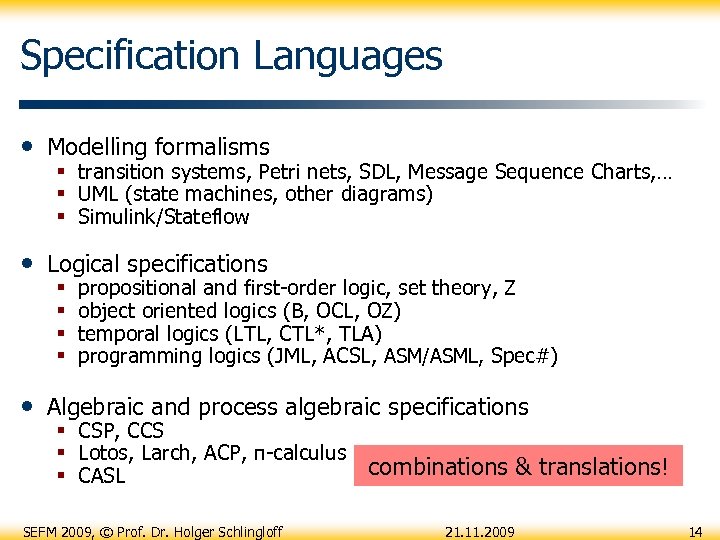

Specification Languages • Modelling formalisms § transition systems, Petri nets, SDL, Message Sequence Charts, … § UML (state machines, other diagrams) § Simulink/Stateflow • Logical specifications § § propositional and first-order logic, set theory, Z object oriented logics (B, OCL, OZ) temporal logics (LTL, CTL*, TLA) programming logics (JML, ACSL, ASM/ASML, Spec#) • Algebraic and process algebraic specifications § CSP, CCS § Lotos, Larch, ACP, π-calculus § CASL SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff combinations & translations! 21. 11. 2009 14

Specification Languages • Modelling formalisms § transition systems, Petri nets, SDL, Message Sequence Charts, … § UML (state machines, other diagrams) § Simulink/Stateflow • Logical specifications § § propositional and first-order logic, set theory, Z object oriented logics (B, OCL, OZ) temporal logics (LTL, CTL*, TLA) programming logics (JML, ACSL, ASM/ASML, Spec#) • Algebraic and process algebraic specifications § CSP, CCS § Lotos, Larch, ACP, π-calculus § CASL SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff combinations & translations! 21. 11. 2009 14

SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 15

SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 15

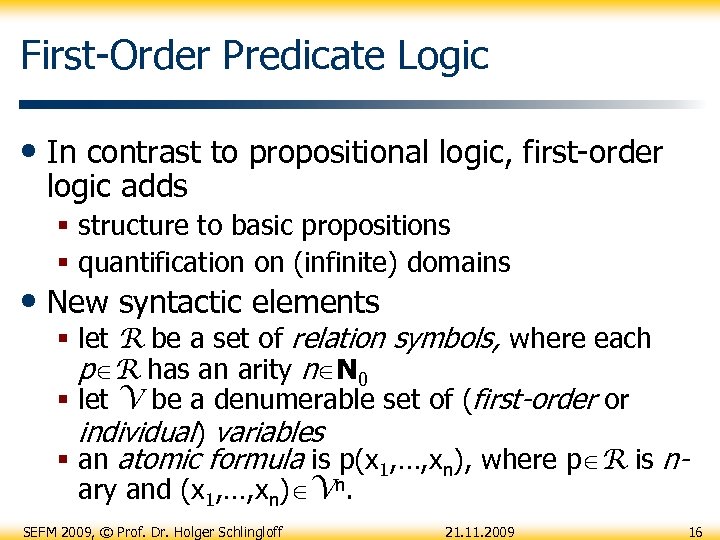

First-Order Predicate Logic • In contrast to propositional logic, first-order logic adds § structure to basic propositions § quantification on (infinite) domains • New syntactic elements § let R be a set of relation symbols, where each p R has an arity n N 0 § let V be a denumerable set of (first-order or individual) variables § an atomic formula is p(x 1, …, xn), where p R is nary and (x 1, …, xn) Vn. SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 16

First-Order Predicate Logic • In contrast to propositional logic, first-order logic adds § structure to basic propositions § quantification on (infinite) domains • New syntactic elements § let R be a set of relation symbols, where each p R has an arity n N 0 § let V be a denumerable set of (first-order or individual) variables § an atomic formula is p(x 1, …, xn), where p R is nary and (x 1, …, xn) Vn. SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 16

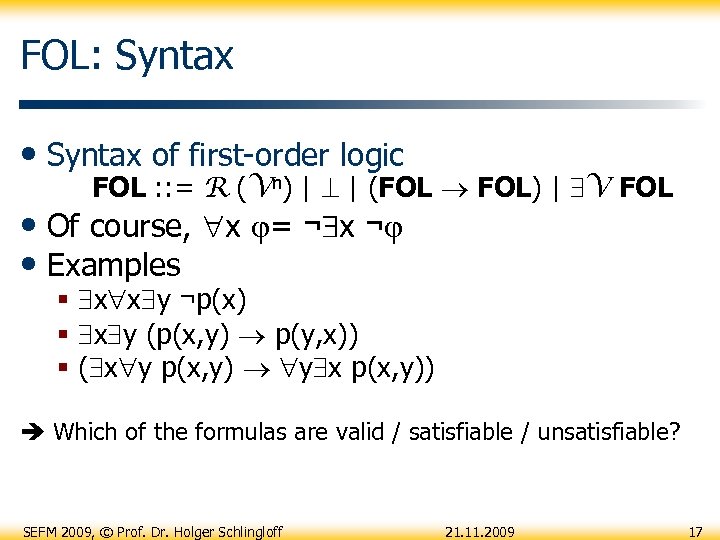

FOL: Syntax • Syntax of first-order logic FOL : : = R (Vn) | | (FOL FOL) | V FOL • Of course, x = ¬ x ¬ • Examples § x x y ¬p(x) § x y (p(x, y) p(y, x)) § ( x y p(x, y) y x p(x, y)) Which of the formulas are valid / satisfiable / unsatisfiable? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 17

FOL: Syntax • Syntax of first-order logic FOL : : = R (Vn) | | (FOL FOL) | V FOL • Of course, x = ¬ x ¬ • Examples § x x y ¬p(x) § x y (p(x, y) p(y, x)) § ( x y p(x, y) y x p(x, y)) Which of the formulas are valid / satisfiable / unsatisfiable? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 17

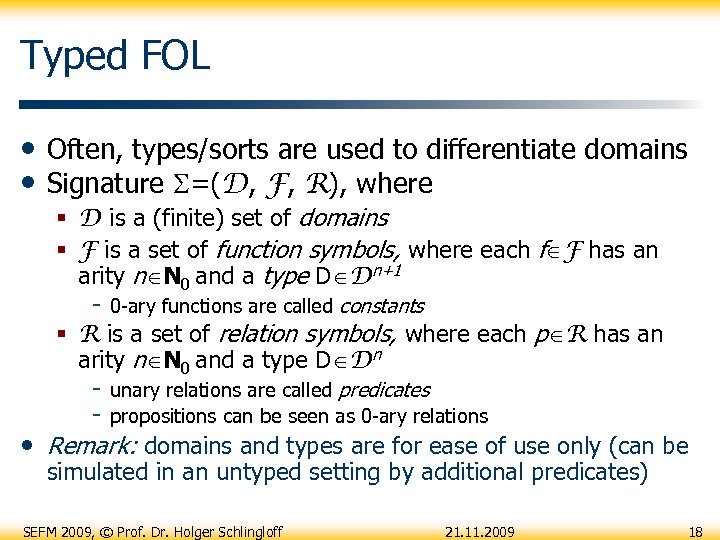

Typed FOL • Often, types/sorts are used to differentiate domains • Signature =(D, F, R), where § D is a (finite) set of domains § F is a set of function symbols, where each f F has an arity n N 0 and a type D Dn+1 - 0 -ary functions are called constants § R is a set of relation symbols, where each p R has an arity n N 0 and a type D Dn - unary relations are called predicates - propositions can be seen as 0 -ary relations • Remark: domains and types are for ease of use only (can be simulated in an untyped setting by additional predicates) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 18

Typed FOL • Often, types/sorts are used to differentiate domains • Signature =(D, F, R), where § D is a (finite) set of domains § F is a set of function symbols, where each f F has an arity n N 0 and a type D Dn+1 - 0 -ary functions are called constants § R is a set of relation symbols, where each p R has an arity n N 0 and a type D Dn - unary relations are called predicates - propositions can be seen as 0 -ary relations • Remark: domains and types are for ease of use only (can be simulated in an untyped setting by additional predicates) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 18

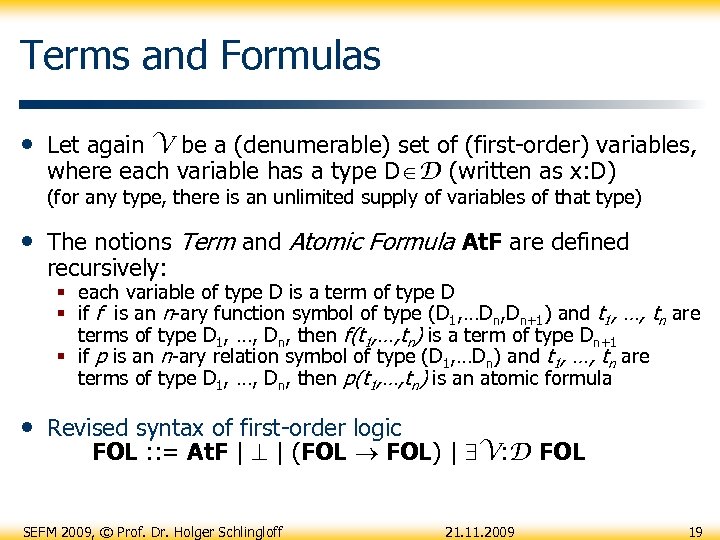

Terms and Formulas • Let again V be a (denumerable) set of (first-order) variables, where each variable has a type D D (written as x: D) (for any type, there is an unlimited supply of variables of that type) • The notions Term and Atomic Formula At. F are defined recursively: § each variable of type D is a term of type D § if f is an n-ary function symbol of type (D 1, …Dn, Dn+1) and t 1, …, tn are terms of type D 1, …, Dn, then f(t 1, …, tn) is a term of type Dn+1 § if p is an n-ary relation symbol of type (D 1, …Dn) and t 1, …, tn are terms of type D 1, …, Dn, then p(t 1, …, tn) is an atomic formula • Revised syntax of first-order logic FOL : : = At. F | | (FOL FOL) | V: D FOL SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 19

Terms and Formulas • Let again V be a (denumerable) set of (first-order) variables, where each variable has a type D D (written as x: D) (for any type, there is an unlimited supply of variables of that type) • The notions Term and Atomic Formula At. F are defined recursively: § each variable of type D is a term of type D § if f is an n-ary function symbol of type (D 1, …Dn, Dn+1) and t 1, …, tn are terms of type D 1, …, Dn, then f(t 1, …, tn) is a term of type Dn+1 § if p is an n-ary relation symbol of type (D 1, …Dn) and t 1, …, tn are terms of type D 1, …, Dn, then p(t 1, …, tn) is an atomic formula • Revised syntax of first-order logic FOL : : = At. F | | (FOL FOL) | V: D FOL SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 19

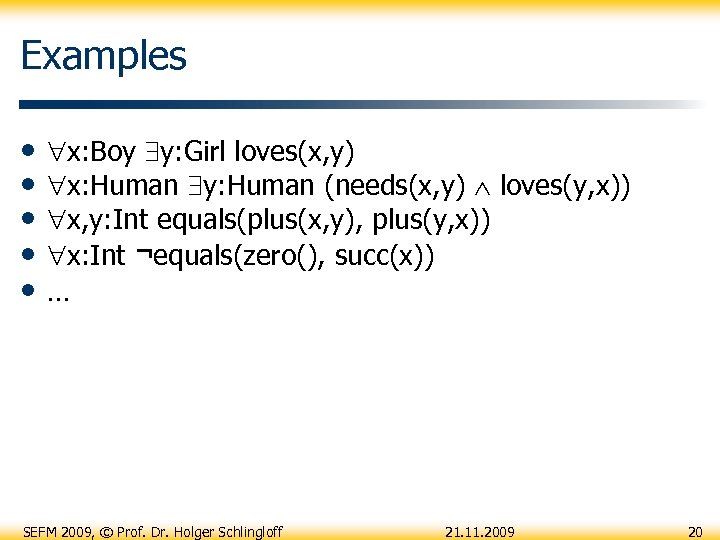

Examples • • • x: Boy y: Girl loves(x, y) x: Human y: Human (needs(x, y) loves(y, x)) x, y: Int equals(plus(x, y), plus(y, x)) x: Int ¬equals(zero(), succ(x)) … SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20

Examples • • • x: Boy y: Girl loves(x, y) x: Human y: Human (needs(x, y) loves(y, x)) x, y: Int equals(plus(x, y), plus(y, x)) x: Int ¬equals(zero(), succ(x)) … SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20

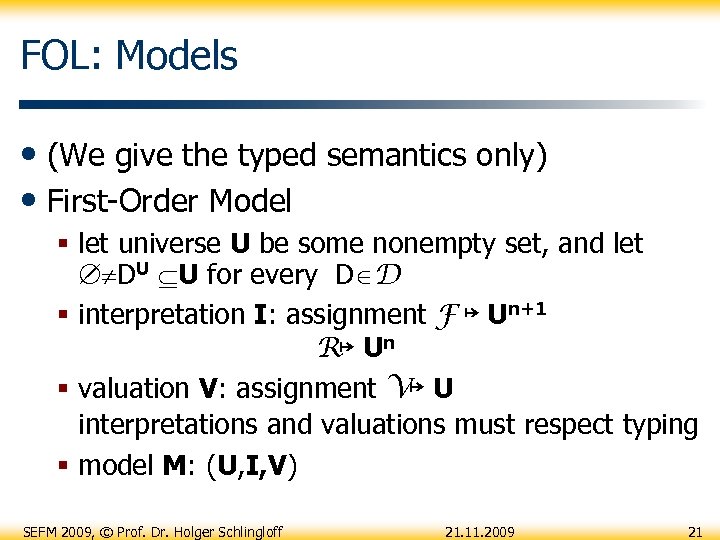

FOL: Models • (We give the typed semantics only) • First-Order Model § let universe U be some nonempty set, and let DU U for every D D § interpretation I: assignment F ↦ Un+1 R↦ Un § valuation V: assignment V↦ U interpretations and valuations must respect typing § model M: (U, I, V) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 21

FOL: Models • (We give the typed semantics only) • First-Order Model § let universe U be some nonempty set, and let DU U for every D D § interpretation I: assignment F ↦ Un+1 R↦ Un § valuation V: assignment V↦ U interpretations and valuations must respect typing § model M: (U, I, V) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 21

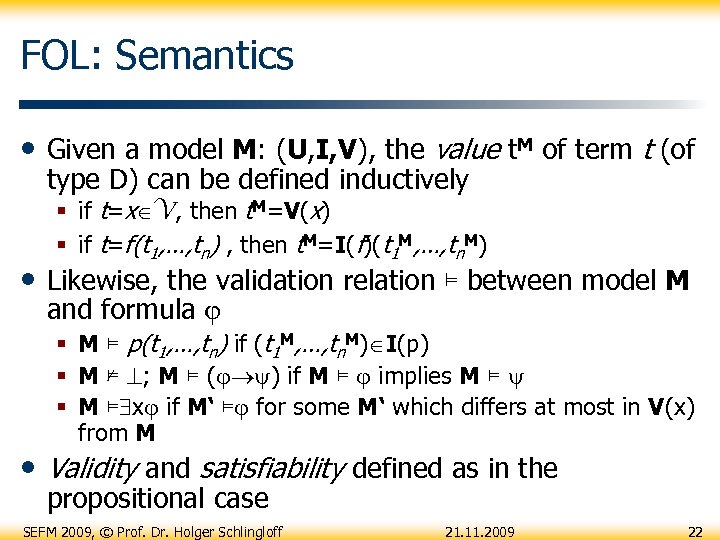

FOL: Semantics • Given a model M: (U, I, V), the value t. M of term t (of type D) can be defined inductively § if t=x V, then t. M=V(x) § if t=f(t 1, …, tn) , then t. M=I(f)(t 1 M, …, tn. M) • Likewise, the validation relation ⊨ between model M and formula § M ⊨ p(t 1, …, tn) if (t 1 M, …, tn. M) I(p) § M ⊭ ; M ⊨ ( ) if M ⊨ implies M ⊨ § M ⊨ x if M‘ ⊨ for some M‘ which differs at most in V(x) from M • Validity and satisfiability defined as in the propositional case SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 22

FOL: Semantics • Given a model M: (U, I, V), the value t. M of term t (of type D) can be defined inductively § if t=x V, then t. M=V(x) § if t=f(t 1, …, tn) , then t. M=I(f)(t 1 M, …, tn. M) • Likewise, the validation relation ⊨ between model M and formula § M ⊨ p(t 1, …, tn) if (t 1 M, …, tn. M) I(p) § M ⊭ ; M ⊨ ( ) if M ⊨ implies M ⊨ § M ⊨ x if M‘ ⊨ for some M‘ which differs at most in V(x) from M • Validity and satisfiability defined as in the propositional case SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 22

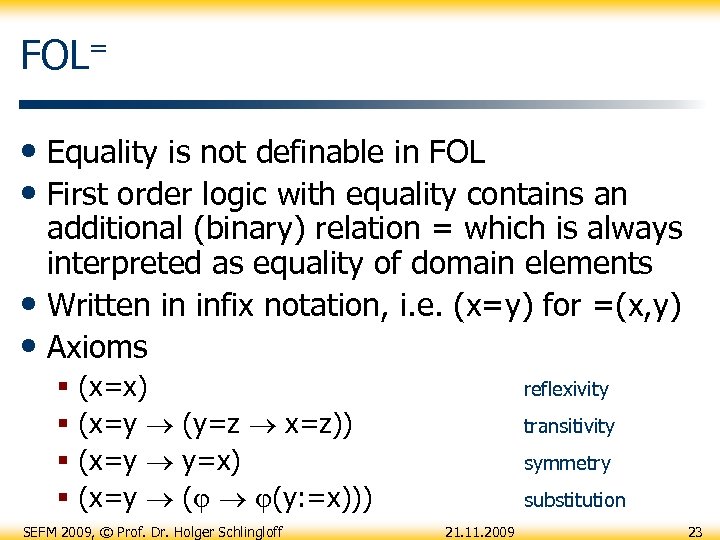

FOL= • Equality is not definable in FOL • First order logic with equality contains an additional (binary) relation = which is always interpreted as equality of domain elements • Written in infix notation, i. e. (x=y) for =(x, y) • Axioms § § (x=x) (x=y (y=z x=z)) (x=y y=x) (x=y ( (y: =x))) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff reflexivity transitivity symmetry substitution 21. 11. 2009 23

FOL= • Equality is not definable in FOL • First order logic with equality contains an additional (binary) relation = which is always interpreted as equality of domain elements • Written in infix notation, i. e. (x=y) for =(x, y) • Axioms § § (x=x) (x=y (y=z x=z)) (x=y y=x) (x=y ( (y: =x))) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff reflexivity transitivity symmetry substitution 21. 11. 2009 23

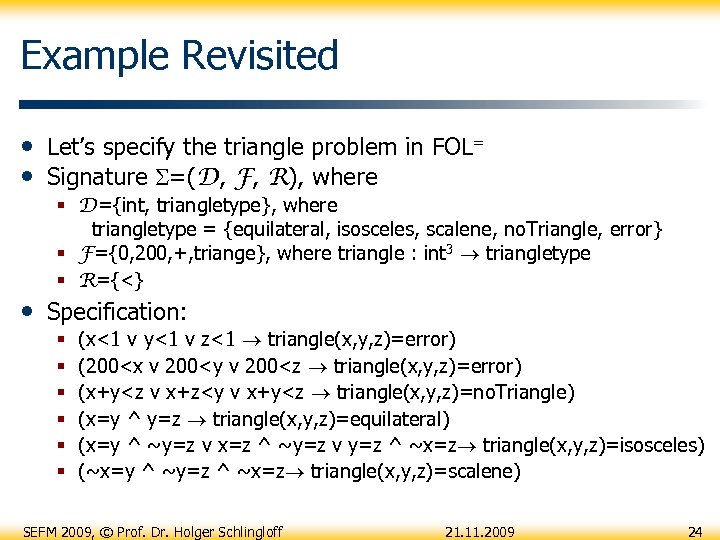

Example Revisited • Let’s specify the triangle problem in FOL= • Signature =(D, F, R), where § D={int, triangletype}, where triangletype = {equilateral, isosceles, scalene, no. Triangle, error} § F={0, 200, +, triange}, where triangle : int 3 triangletype § R={<} • Specification: § § § (x<1 v y<1 v z<1 triangle(x, y, z)=error) (200

Example Revisited • Let’s specify the triangle problem in FOL= • Signature =(D, F, R), where § D={int, triangletype}, where triangletype = {equilateral, isosceles, scalene, no. Triangle, error} § F={0, 200, +, triange}, where triangle : int 3 triangletype § R={<} • Specification: § § § (x<1 v y<1 v z<1 triangle(x, y, z)=error) (200

Remarks • A clean requirements analysis eases the formal specification considerably • First-order logic is well-suited to formalize most mathematical problems • Again, a formal specification can be used for § interactively deriving an implementation, or § interactively deriving and evaluating test cases - we’ll come back to this later SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 25

Remarks • A clean requirements analysis eases the formal specification considerably • First-order logic is well-suited to formalize most mathematical problems • Again, a formal specification can be used for § interactively deriving an implementation, or § interactively deriving and evaluating test cases - we’ll come back to this later SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 25

Exercise • Give a FOL= specification of the “integer square root” function! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 26

Exercise • Give a FOL= specification of the “integer square root” function! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 26

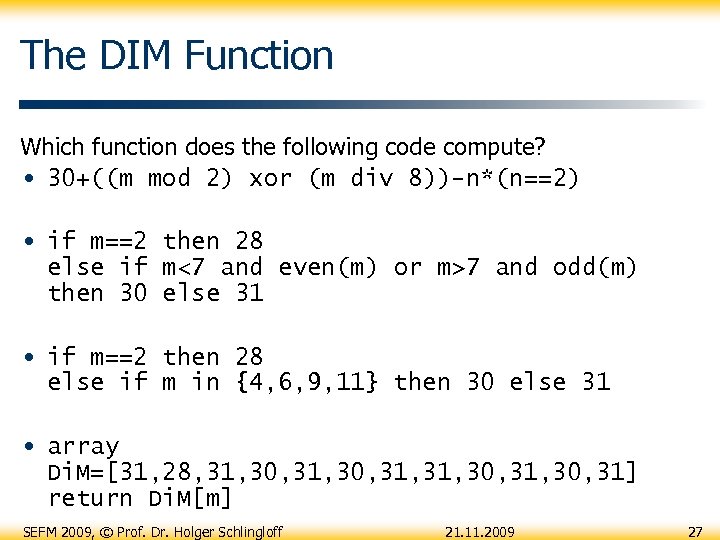

The DIM Function Which function does the following code compute? • 30+((m mod 2) xor (m div 8))-n*(n==2) • if m==2 then 28 else if m<7 and even(m) or m>7 and odd(m) then 30 else 31 • if m==2 then 28 else if m in {4, 6, 9, 11} then 30 else 31 • array Di. M=[31, 28, 31, 30, 31] return Di. M[m] SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 27

The DIM Function Which function does the following code compute? • 30+((m mod 2) xor (m div 8))-n*(n==2) • if m==2 then 28 else if m<7 and even(m) or m>7 and odd(m) then 30 else 31 • if m==2 then 28 else if m in {4, 6, 9, 11} then 30 else 31 • array Di. M=[31, 28, 31, 30, 31] return Di. M[m] SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 27

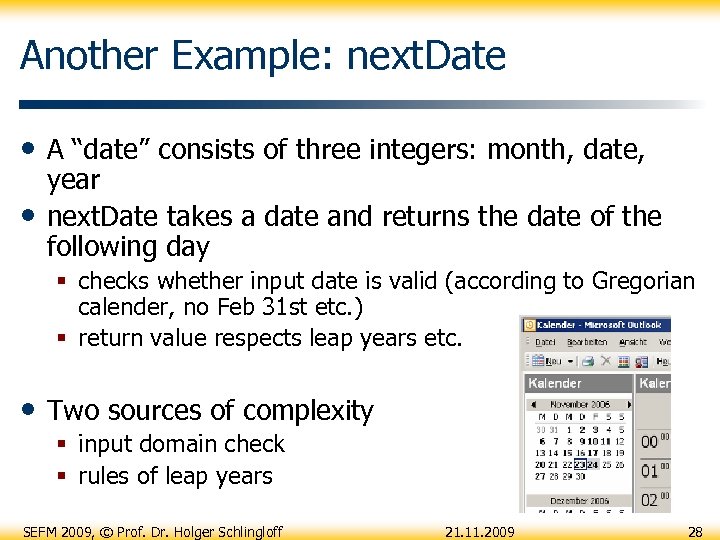

Another Example: next. Date • A “date” consists of three integers: month, date, • year next. Date takes a date and returns the date of the following day § checks whether input date is valid (according to Gregorian calender, no Feb 31 st etc. ) § return value respects leap years etc. • Two sources of complexity § input domain check § rules of leap years SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 28

Another Example: next. Date • A “date” consists of three integers: month, date, • year next. Date takes a date and returns the date of the following day § checks whether input date is valid (according to Gregorian calender, no Feb 31 st etc. ) § return value respects leap years etc. • Two sources of complexity § input domain check § rules of leap years SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 28

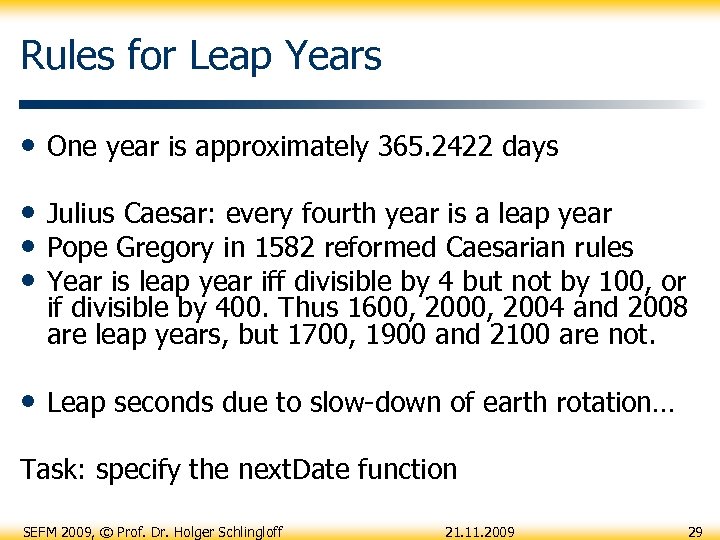

Rules for Leap Years • One year is approximately 365. 2422 days • Julius Caesar: every fourth year is a leap year • Pope Gregory in 1582 reformed Caesarian rules • Year is leap year iff divisible by 4 but not by 100, or if divisible by 400. Thus 1600, 2004 and 2008 are leap years, but 1700, 1900 and 2100 are not. • Leap seconds due to slow-down of earth rotation… Task: specify the next. Date function SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 29

Rules for Leap Years • One year is approximately 365. 2422 days • Julius Caesar: every fourth year is a leap year • Pope Gregory in 1582 reformed Caesarian rules • Year is leap year iff divisible by 4 but not by 100, or if divisible by 400. Thus 1600, 2004 and 2008 are leap years, but 1700, 1900 and 2100 are not. • Leap seconds due to slow-down of earth rotation… Task: specify the next. Date function SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 29

Break! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 30

Break! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 30

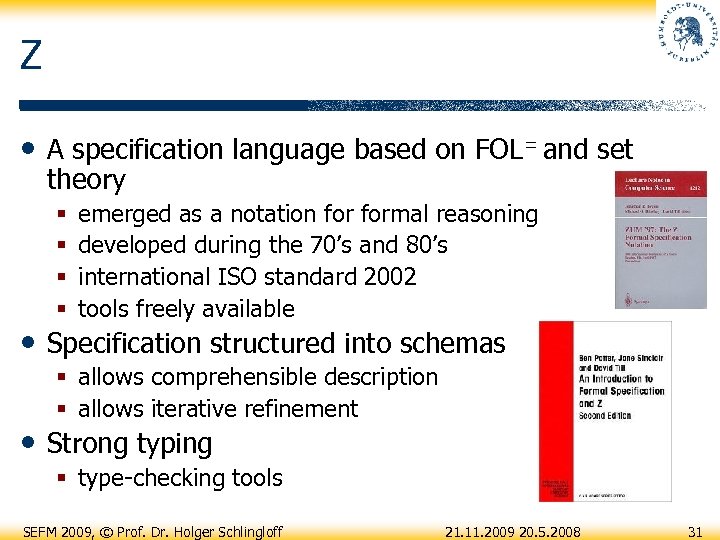

Z • A specification language based on FOL= and set theory § § emerged as a notation formal reasoning developed during the 70’s and 80’s international ISO standard 2002 tools freely available • Specification structured into schemas § allows comprehensible description § allows iterative refinement • Strong typing § type-checking tools SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 31

Z • A specification language based on FOL= and set theory § § emerged as a notation formal reasoning developed during the 70’s and 80’s international ISO standard 2002 tools freely available • Specification structured into schemas § allows comprehensible description § allows iterative refinement • Strong typing § type-checking tools SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 31

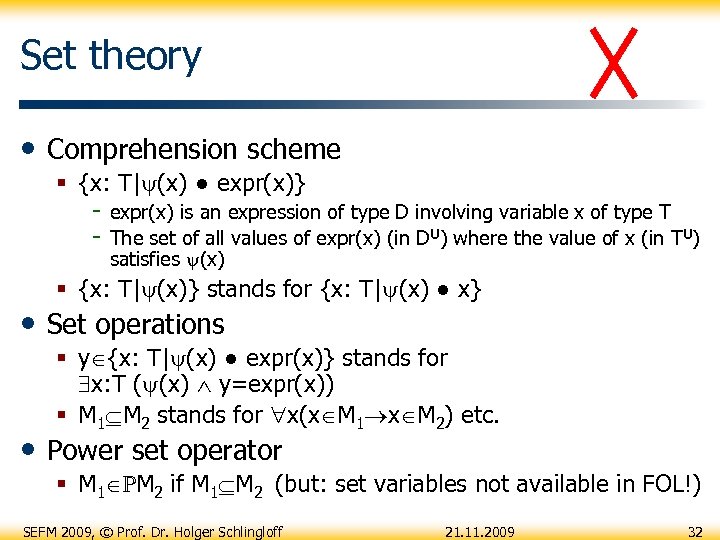

Set theory • Comprehension scheme § {x: T| (x) ● expr(x)} - expr(x) is an expression of type D involving variable x of type T - The set of all values of expr(x) (in DU) where the value of x (in TU) satisfies (x) § {x: T| (x)} stands for {x: T| (x) ● x} • Set operations § y {x: T| (x) ● expr(x)} stands for x: T ( (x) y=expr(x)) § M 1 M 2 stands for x(x M 1 x M 2) etc. • Power set operator § M 1 ℙM 2 if M 1 M 2 (but: set variables not available in FOL!) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 32

Set theory • Comprehension scheme § {x: T| (x) ● expr(x)} - expr(x) is an expression of type D involving variable x of type T - The set of all values of expr(x) (in DU) where the value of x (in TU) satisfies (x) § {x: T| (x)} stands for {x: T| (x) ● x} • Set operations § y {x: T| (x) ● expr(x)} stands for x: T ( (x) y=expr(x)) § M 1 M 2 stands for x(x M 1 x M 2) etc. • Power set operator § M 1 ℙM 2 if M 1 M 2 (but: set variables not available in FOL!) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 32

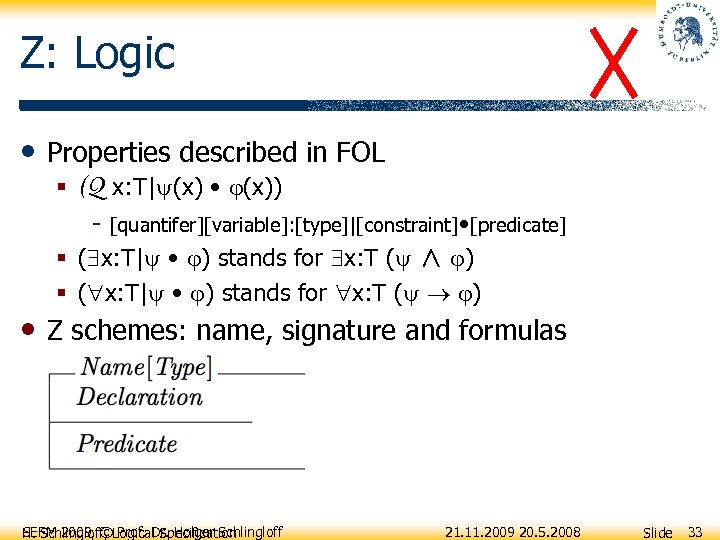

Z: Logic • Properties described in FOL § (Q x: T| (x) • (x)) - [quantifer][variable]: [type]|[constraint] • [predicate] § ( x: T| • ) stands for x: T ( ∧ ) § ( x: T| • ) stands for x: T ( ) • Z schemes: name, signature and formulas SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff H. Schlingloff, Logical Specification 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 Slide 33

Z: Logic • Properties described in FOL § (Q x: T| (x) • (x)) - [quantifer][variable]: [type]|[constraint] • [predicate] § ( x: T| • ) stands for x: T ( ∧ ) § ( x: T| • ) stands for x: T ( ) • Z schemes: name, signature and formulas SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff H. Schlingloff, Logical Specification 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 Slide 33

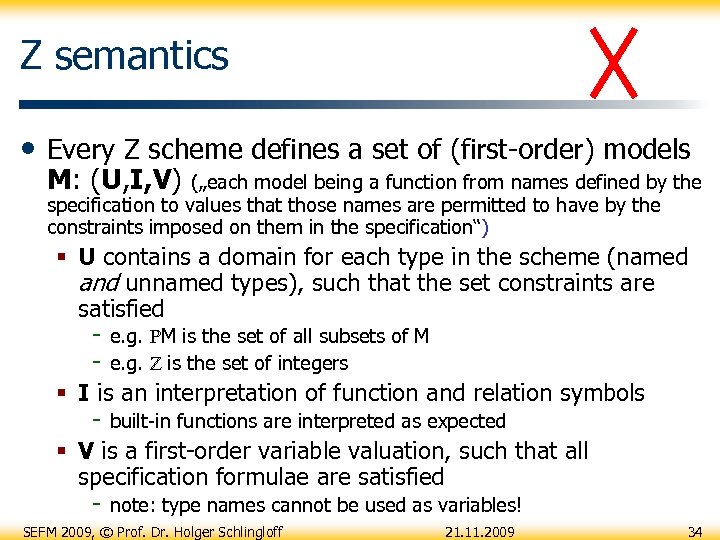

Z semantics • Every Z scheme defines a set of (first-order) models M: (U, I, V) („each model being a function from names defined by the specification to values that those names are permitted to have by the constraints imposed on them in the specification“) § U contains a domain for each type in the scheme (named and unnamed types), such that the set constraints are satisfied - e. g. ℙM is the set of all subsets of M - e. g. ℤ is the set of integers § I is an interpretation of function and relation symbols - built-in functions are interpreted as expected § V is a first-order variable valuation, such that all specification formulae are satisfied - note: type names cannot be used as variables! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 34

Z semantics • Every Z scheme defines a set of (first-order) models M: (U, I, V) („each model being a function from names defined by the specification to values that those names are permitted to have by the constraints imposed on them in the specification“) § U contains a domain for each type in the scheme (named and unnamed types), such that the set constraints are satisfied - e. g. ℙM is the set of all subsets of M - e. g. ℤ is the set of integers § I is an interpretation of function and relation symbols - built-in functions are interpreted as expected § V is a first-order variable valuation, such that all specification formulae are satisfied - note: type names cannot be used as variables! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 34

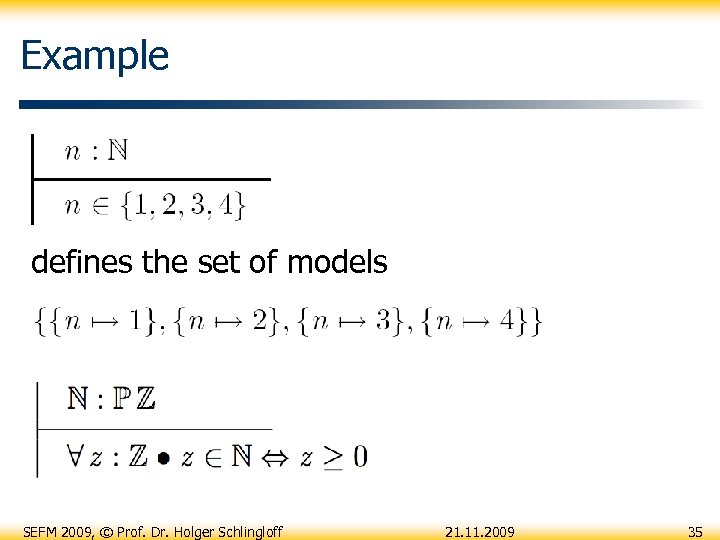

Example defines the set of models SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 35

Example defines the set of models SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 35

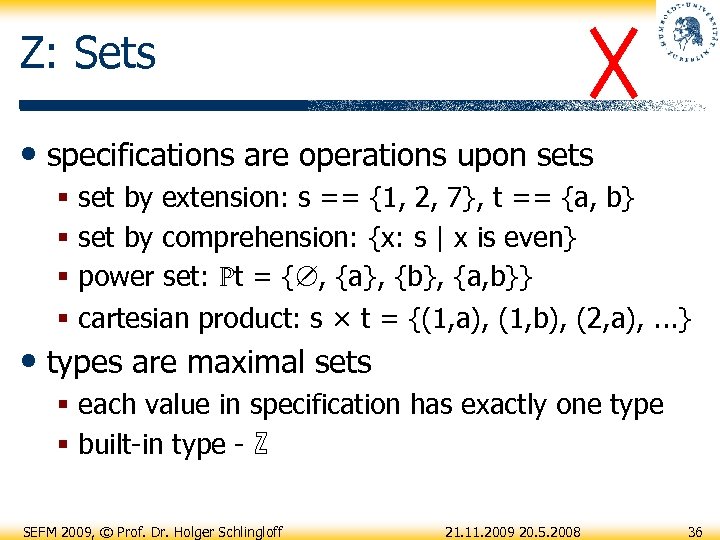

Z: Sets • specifications are operations upon sets § § set by extension: s == {1, 2, 7}, t == {a, b} set by comprehension: {x: s | x is even} power set: ℙt = { , {a}, {b}, {a, b}} cartesian product: s × t = {(1, a), (1, b), (2, a), . . . } • types are maximal sets § each value in specification has exactly one type § built-in type - ℤ SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 36

Z: Sets • specifications are operations upon sets § § set by extension: s == {1, 2, 7}, t == {a, b} set by comprehension: {x: s | x is even} power set: ℙt = { , {a}, {b}, {a, b}} cartesian product: s × t = {(1, a), (1, b), (2, a), . . . } • types are maximal sets § each value in specification has exactly one type § built-in type - ℤ SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 36

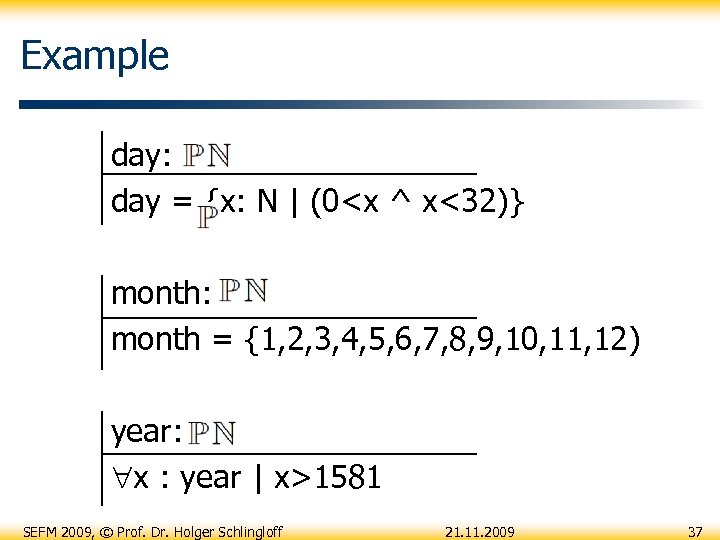

Example day: day = {x: N | (0

Example day: day = {x: N | (0

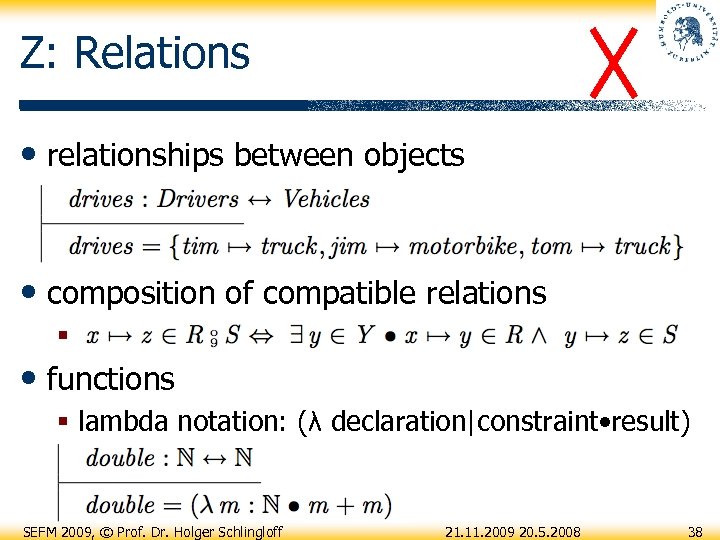

Z: Relations • relationships between objects • composition of compatible relations § • functions § lambda notation: (λ declaration|constraint • result) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 38

Z: Relations • relationships between objects • composition of compatible relations § • functions § lambda notation: (λ declaration|constraint • result) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 38

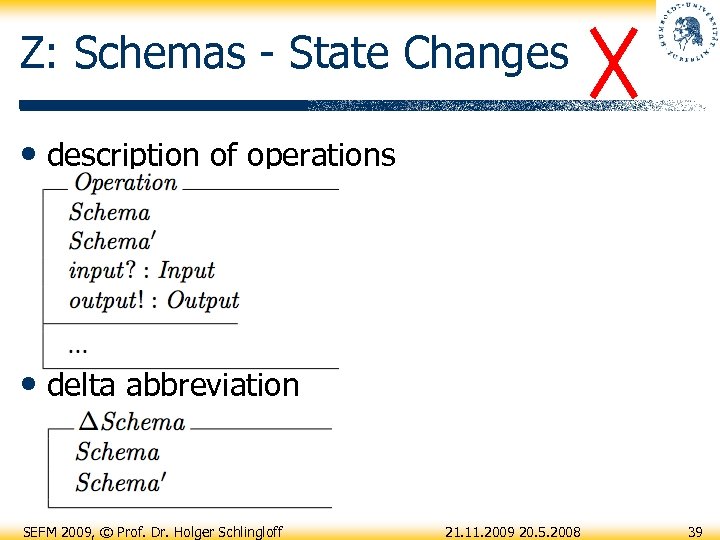

Z: Schemas - State Changes • description of operations • delta abbreviation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 39

Z: Schemas - State Changes • description of operations • delta abbreviation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 39

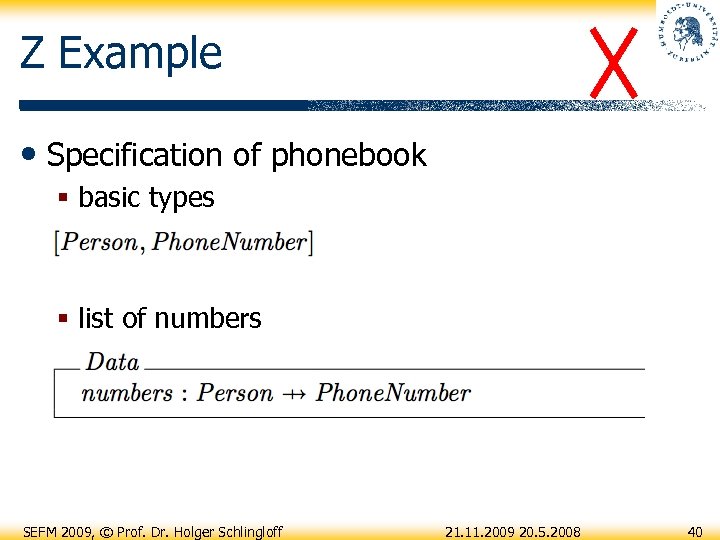

Z Example • Specification of phonebook § basic types § list of numbers SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 40

Z Example • Specification of phonebook § basic types § list of numbers SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 40

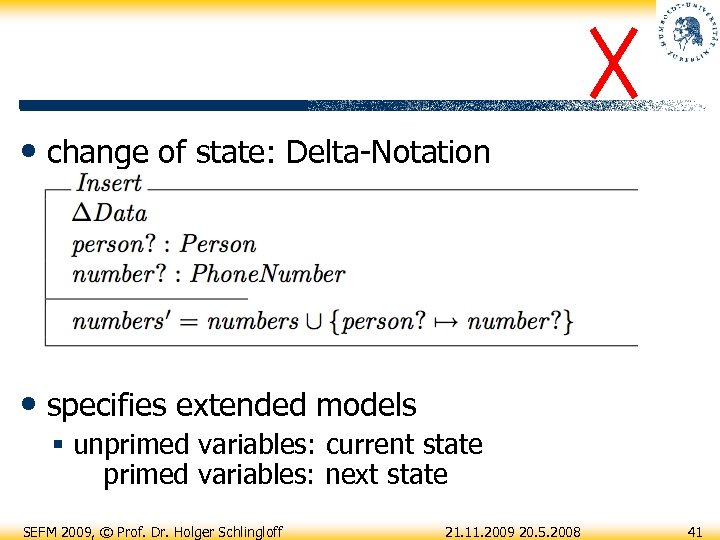

• change of state: Delta-Notation • specifies extended models § unprimed variables: current state primed variables: next state SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 41

• change of state: Delta-Notation • specifies extended models § unprimed variables: current state primed variables: next state SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 41

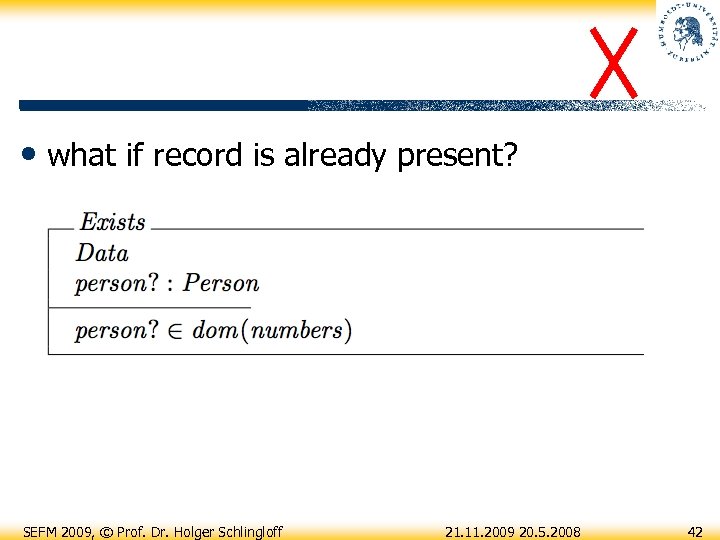

• what if record is already present? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 42

• what if record is already present? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 42

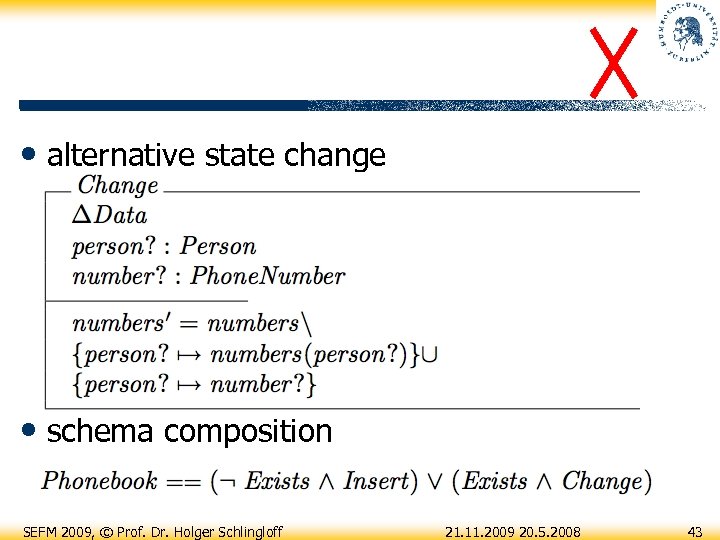

• alternative state change • schema composition SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 43

• alternative state change • schema composition SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 43

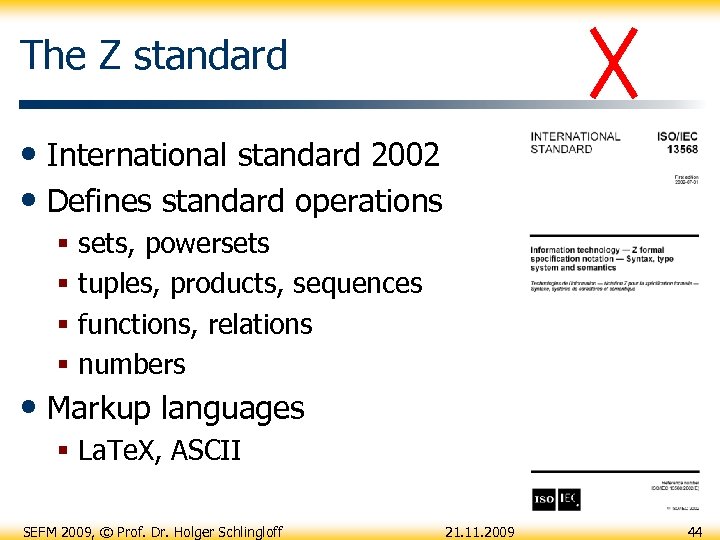

The Z standard • International standard 2002 • Defines standard operations § § sets, powersets tuples, products, sequences functions, relations numbers • Markup languages § La. Te. X, ASCII SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 44

The Z standard • International standard 2002 • Defines standard operations § § sets, powersets tuples, products, sequences functions, relations numbers • Markup languages § La. Te. X, ASCII SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 44

Z: References and Tools • Z notation § J. Mike Spivey (1992). The Z Notation: a reference manual § Jim Davies and Jim Woodcock (1996). Using Z: Specification, Refinement and Proof • Community Z tools (CZT) § editing and type-checking Z specifications § czt. sourceforge. net • Smartesting Leirios Test Generator (LTG) § derivation of test cases from Z and B schemas SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 45

Z: References and Tools • Z notation § J. Mike Spivey (1992). The Z Notation: a reference manual § Jim Davies and Jim Woodcock (1996). Using Z: Specification, Refinement and Proof • Community Z tools (CZT) § editing and type-checking Z specifications § czt. sourceforge. net • Smartesting Leirios Test Generator (LTG) § derivation of test cases from Z and B schemas SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 20. 5. 2008 45

Summary: Z • Basic building blocks: Z schemes § declarations (signature) § predicates (formulas constraining variable values) § well-defined semantics via predicate logic • High expressiveness by set theory and logic • Modularity (but no object orientation) • Well-suited for program verification • Not so well-suited for refinement (transformational program development) and/or test generation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 46

Summary: Z • Basic building blocks: Z schemes § declarations (signature) § predicates (formulas constraining variable values) § well-defined semantics via predicate logic • High expressiveness by set theory and logic • Modularity (but no object orientation) • Well-suited for program verification • Not so well-suited for refinement (transformational program development) and/or test generation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 46

SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 47

SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 47

Unit Testing • Often considered “the” testing § often the first analytical step after coding § first execution of actual system parts § often done by programmer herself • The SUT consists of: § procedures, functions (in imperative languages) § modules, units, classes, interfaces (in oo programs) § blocks (in model-based development) • Same or similar development environment as for SUT itself (compiler, linker, platform, …) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 48

Unit Testing • Often considered “the” testing § often the first analytical step after coding § first execution of actual system parts § often done by programmer herself • The SUT consists of: § procedures, functions (in imperative languages) § modules, units, classes, interfaces (in oo programs) § blocks (in model-based development) • Same or similar development environment as for SUT itself (compiler, linker, platform, …) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 48

Unit Testing Methodology • Each unit is tested independently of all the others § no external influences or disturbances § fault localisation is usually no problem § nesting is allowed, poses additional difficulties • Unit is linked with testing program § setting of SUT environment (variables) by testing program § invocation of SUT functions with appropriate parameters § evaluation of result by comparison of variables SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 49

Unit Testing Methodology • Each unit is tested independently of all the others § no external influences or disturbances § fault localisation is usually no problem § nesting is allowed, poses additional difficulties • Unit is linked with testing program § setting of SUT environment (variables) by testing program § invocation of SUT functions with appropriate parameters § evaluation of result by comparison of variables SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 49

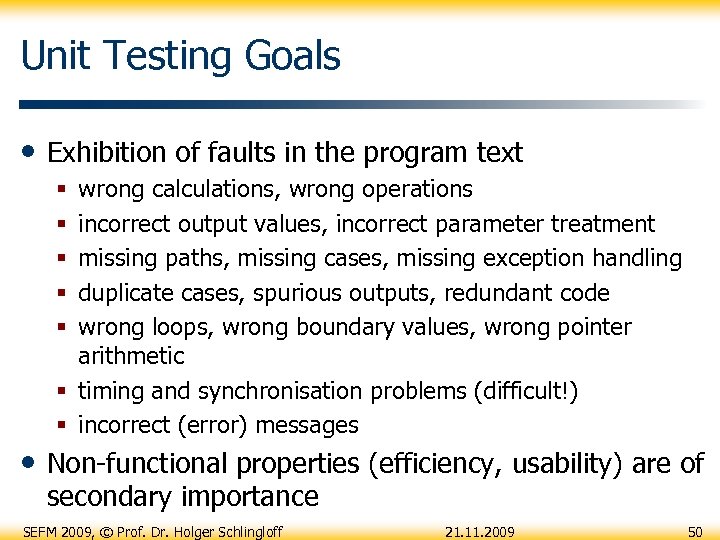

Unit Testing Goals • Exhibition of faults in the program text wrong calculations, wrong operations incorrect output values, incorrect parameter treatment missing paths, missing cases, missing exception handling duplicate cases, spurious outputs, redundant code wrong loops, wrong boundary values, wrong pointer arithmetic § timing and synchronisation problems (difficult!) § incorrect (error) messages § § § • Non-functional properties (efficiency, usability) are of secondary importance SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 50

Unit Testing Goals • Exhibition of faults in the program text wrong calculations, wrong operations incorrect output values, incorrect parameter treatment missing paths, missing cases, missing exception handling duplicate cases, spurious outputs, redundant code wrong loops, wrong boundary values, wrong pointer arithmetic § timing and synchronisation problems (difficult!) § incorrect (error) messages § § § • Non-functional properties (efficiency, usability) are of secondary importance SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 50

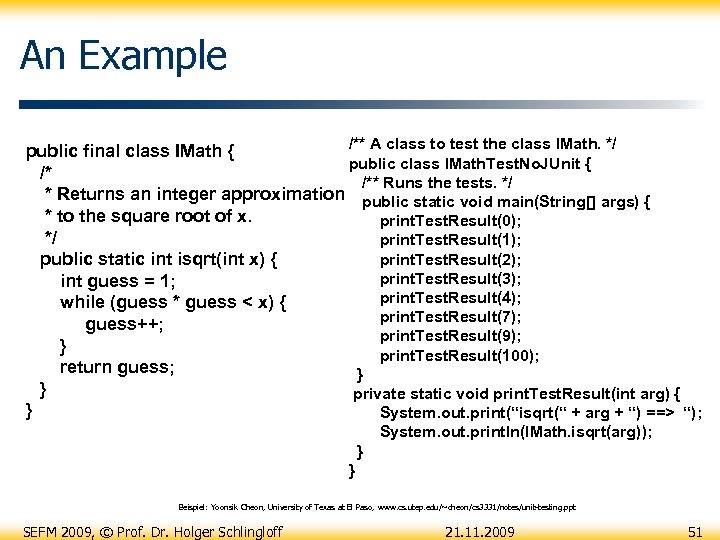

An Example /** A class to test the class IMath. */ public final class IMath { public class IMath. Test. No. JUnit { /* /** Runs the tests. */ * Returns an integer approximation public static void main(String[] args) { * to the square root of x. print. Test. Result(0); */ print. Test. Result(1); print. Test. Result(2); public static int isqrt(int x) { print. Test. Result(3); int guess = 1; print. Test. Result(4); while (guess * guess < x) { print. Test. Result(7); guess++; print. Test. Result(9); } print. Test. Result(100); return guess; } } private static void print. Test. Result(int arg) { } System. out. print(“isqrt(“ + arg + “) ==> “); System. out. println(IMath. isqrt(arg)); } } Beispiel: Yoonsik Cheon, University of Texas at El Paso, www. cs. utep. edu/~cheon/cs 3331/notes/unit-testing. ppt SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 51

An Example /** A class to test the class IMath. */ public final class IMath { public class IMath. Test. No. JUnit { /* /** Runs the tests. */ * Returns an integer approximation public static void main(String[] args) { * to the square root of x. print. Test. Result(0); */ print. Test. Result(1); print. Test. Result(2); public static int isqrt(int x) { print. Test. Result(3); int guess = 1; print. Test. Result(4); while (guess * guess < x) { print. Test. Result(7); guess++; print. Test. Result(9); } print. Test. Result(100); return guess; } } private static void print. Test. Result(int arg) { } System. out. print(“isqrt(“ + arg + “) ==> “); System. out. println(IMath. isqrt(arg)); } } Beispiel: Yoonsik Cheon, University of Texas at El Paso, www. cs. utep. edu/~cheon/cs 3331/notes/unit-testing. ppt SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 51

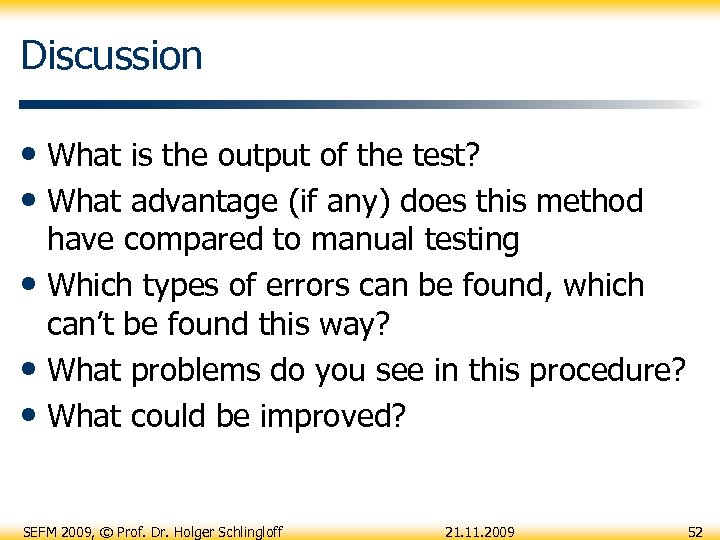

Discussion • What is the output of the test? • What advantage (if any) does this method have compared to manual testing • Which types of errors can be found, which can’t be found this way? • What problems do you see in this procedure? • What could be improved? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 52

Discussion • What is the output of the test? • What advantage (if any) does this method have compared to manual testing • Which types of errors can be found, which can’t be found this way? • What problems do you see in this procedure? • What could be improved? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 52

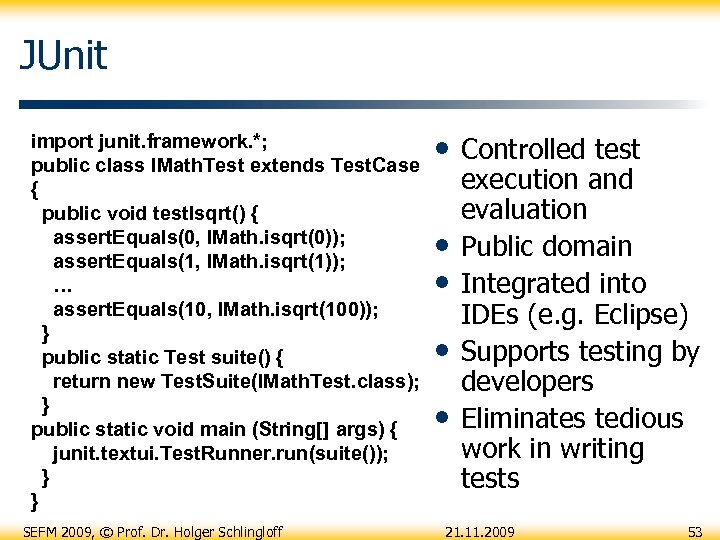

JUnit import junit. framework. *; public class IMath. Test extends Test. Case { public void test. Isqrt() { assert. Equals(0, IMath. isqrt(0)); assert. Equals(1, IMath. isqrt(1)); … assert. Equals(10, IMath. isqrt(100)); } public static Test suite() { return new Test. Suite(IMath. Test. class); } public static void main (String[] args) { junit. textui. Test. Runner. run(suite()); } } SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff • Controlled test • • execution and evaluation Public domain Integrated into IDEs (e. g. Eclipse) Supports testing by developers Eliminates tedious work in writing tests 21. 11. 2009 53

JUnit import junit. framework. *; public class IMath. Test extends Test. Case { public void test. Isqrt() { assert. Equals(0, IMath. isqrt(0)); assert. Equals(1, IMath. isqrt(1)); … assert. Equals(10, IMath. isqrt(100)); } public static Test suite() { return new Test. Suite(IMath. Test. class); } public static void main (String[] args) { junit. textui. Test. Runner. run(suite()); } } SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff • Controlled test • • execution and evaluation Public domain Integrated into IDEs (e. g. Eclipse) Supports testing by developers Eliminates tedious work in writing tests 21. 11. 2009 53

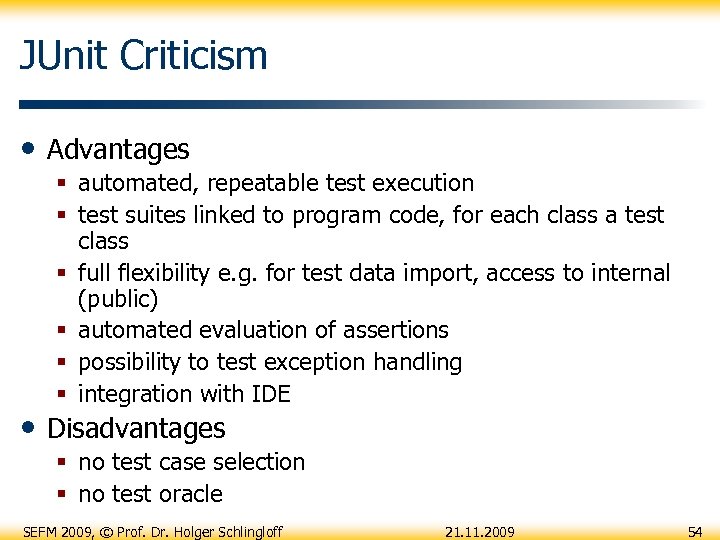

JUnit Criticism • Advantages § automated, repeatable test execution § test suites linked to program code, for each class a test class § full flexibility e. g. for test data import, access to internal (public) § automated evaluation of assertions § possibility to test exception handling § integration with IDE • Disadvantages § no test case selection § no test oracle SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 54

JUnit Criticism • Advantages § automated, repeatable test execution § test suites linked to program code, for each class a test class § full flexibility e. g. for test data import, access to internal (public) § automated evaluation of assertions § possibility to test exception handling § integration with IDE • Disadvantages § no test case selection § no test oracle SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 54

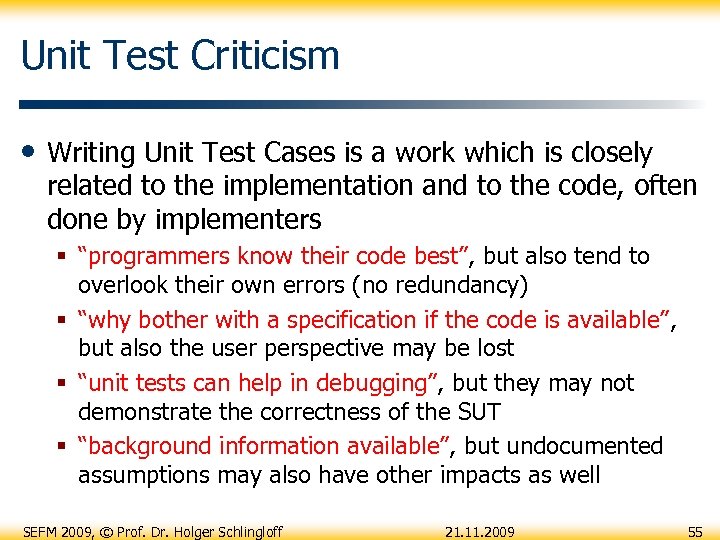

Unit Test Criticism • Writing Unit Test Cases is a work which is closely related to the implementation and to the code, often done by implementers § “programmers know their code best”, but also tend to overlook their own errors (no redundancy) § “why bother with a specification if the code is available”, but also the user perspective may be lost § “unit tests can help in debugging”, but they may not demonstrate the correctness of the SUT § “background information available”, but undocumented assumptions may also have other impacts as well SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 55

Unit Test Criticism • Writing Unit Test Cases is a work which is closely related to the implementation and to the code, often done by implementers § “programmers know their code best”, but also tend to overlook their own errors (no redundancy) § “why bother with a specification if the code is available”, but also the user perspective may be lost § “unit tests can help in debugging”, but they may not demonstrate the correctness of the SUT § “background information available”, but undocumented assumptions may also have other impacts as well SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 55

SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 56

SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 56

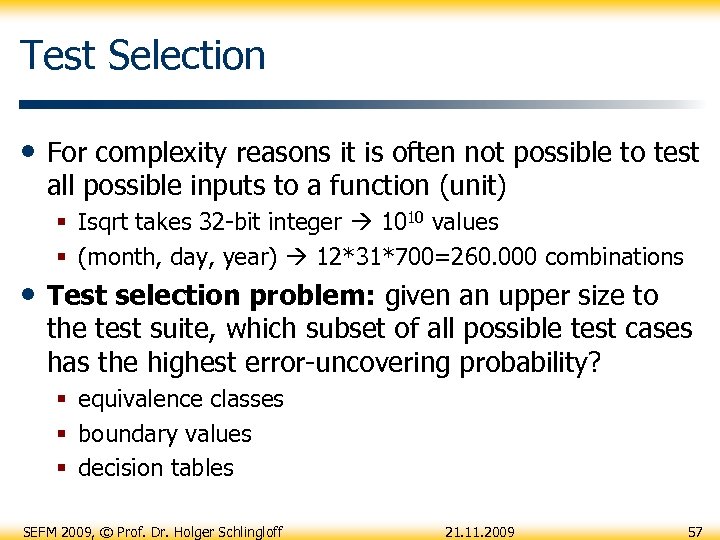

Test Selection • For complexity reasons it is often not possible to test all possible inputs to a function (unit) § Isqrt takes 32 -bit integer 1010 values § (month, day, year) 12*31*700=260. 000 combinations • Test selection problem: given an upper size to the test suite, which subset of all possible test cases has the highest error-uncovering probability? § equivalence classes § boundary values § decision tables SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 57

Test Selection • For complexity reasons it is often not possible to test all possible inputs to a function (unit) § Isqrt takes 32 -bit integer 1010 values § (month, day, year) 12*31*700=260. 000 combinations • Test selection problem: given an upper size to the test suite, which subset of all possible test cases has the highest error-uncovering probability? § equivalence classes § boundary values § decision tables SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 57

Equivalence Class Method • 1 st step: partition the input domain into a finite number of equivalence classes (w. r. t. potential errors) § e. g. equilateral triangle, i. e. three equal positive integers § e. g. [-maxint, -1] [0] [1, 3] [4, maxint] • 2 nd step: choose one representative from each class § e. g. (2, 2, 2) § e. g. -3, 0, 2, 7 • 3 rd step: combine representatives into test cases § only feasible combinations SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 58

Equivalence Class Method • 1 st step: partition the input domain into a finite number of equivalence classes (w. r. t. potential errors) § e. g. equilateral triangle, i. e. three equal positive integers § e. g. [-maxint, -1] [0] [1, 3] [4, maxint] • 2 nd step: choose one representative from each class § e. g. (2, 2, 2) § e. g. -3, 0, 2, 7 • 3 rd step: combine representatives into test cases § only feasible combinations SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 58

How to build equivalence classes • Look at the domains for input and output • For each parameter there are valid and invalid classes § enumerations: contained / not contained § different computation paths: for each path a valid, plus one invalid class § outputs which must be calculated differently: one class for each case § input preconditions: one valid and one invalid class for each input • Split a class if you have reasons to assume that the elements are treated differently SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 59

How to build equivalence classes • Look at the domains for input and output • For each parameter there are valid and invalid classes § enumerations: contained / not contained § different computation paths: for each path a valid, plus one invalid class § outputs which must be calculated differently: one class for each case § input preconditions: one valid and one invalid class for each input • Split a class if you have reasons to assume that the elements are treated differently SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 59

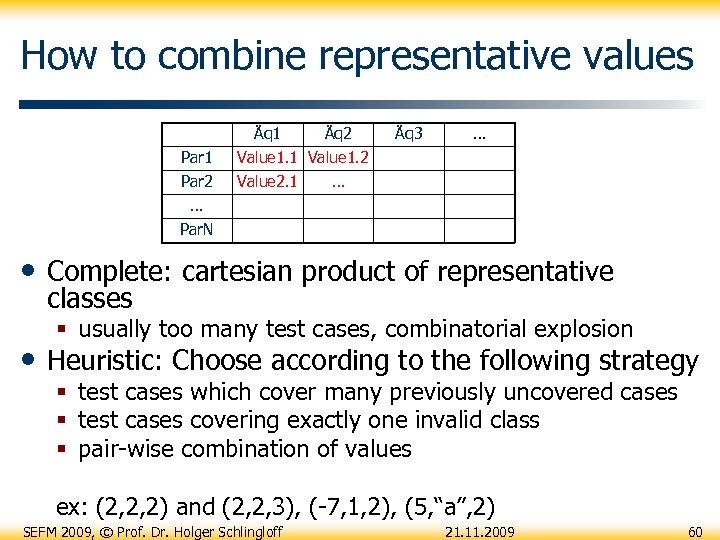

How to combine representative values Äq 1 Äq 2 Par 1 Value 2. 1 … Value 1. 1 Value 1. 2 Par 2 … Äq 3 … Par. N • Complete: cartesian product of representative classes § usually too many test cases, combinatorial explosion • Heuristic: Choose according to the following strategy § test cases which cover many previously uncovered cases § test cases covering exactly one invalid class § pair-wise combination of values ex: (2, 2, 2) and (2, 2, 3), (-7, 1, 2), (5, “a”, 2) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 60

How to combine representative values Äq 1 Äq 2 Par 1 Value 2. 1 … Value 1. 1 Value 1. 2 Par 2 … Äq 3 … Par. N • Complete: cartesian product of representative classes § usually too many test cases, combinatorial explosion • Heuristic: Choose according to the following strategy § test cases which cover many previously uncovered cases § test cases covering exactly one invalid class § pair-wise combination of values ex: (2, 2, 2) and (2, 2, 3), (-7, 1, 2), (5, “a”, 2) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 60

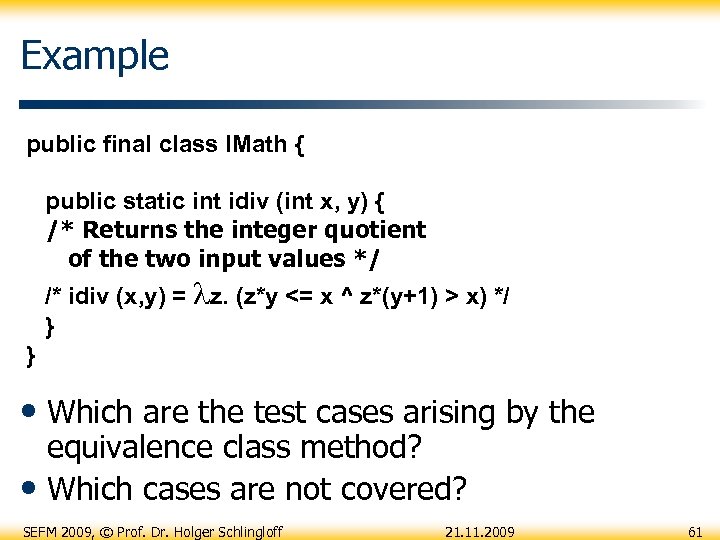

Example public final class IMath { public static int idiv (int x, y) { /* Returns the integer quotient of the two input values */ /* idiv (x, y) = z. (z*y <= x ^ z*(y+1) > x) */ } } • Which are the test cases arising by the equivalence class method? • Which cases are not covered? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 61

Example public final class IMath { public static int idiv (int x, y) { /* Returns the integer quotient of the two input values */ /* idiv (x, y) = z. (z*y <= x ^ z*(y+1) > x) */ } } • Which are the test cases arising by the equivalence class method? • Which cases are not covered? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 61

Discussion • Pro § systematic procedure § reasonable number of test cases § well-suited for “small” functions with pre- and postconditions • Con § selection of test cases by heuristics § interaction between parameter values neglected § with complex parameter sets many equivalence classes • Improvement § boundary value analysis: for each parameter in each test case, find satisfying and unsatisfying assignments SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 62

Discussion • Pro § systematic procedure § reasonable number of test cases § well-suited for “small” functions with pre- and postconditions • Con § selection of test cases by heuristics § interaction between parameter values neglected § with complex parameter sets many equivalence classes • Improvement § boundary value analysis: for each parameter in each test case, find satisfying and unsatisfying assignments SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 62

Equivalence classes for young snakes SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 63

Equivalence classes for young snakes SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 63

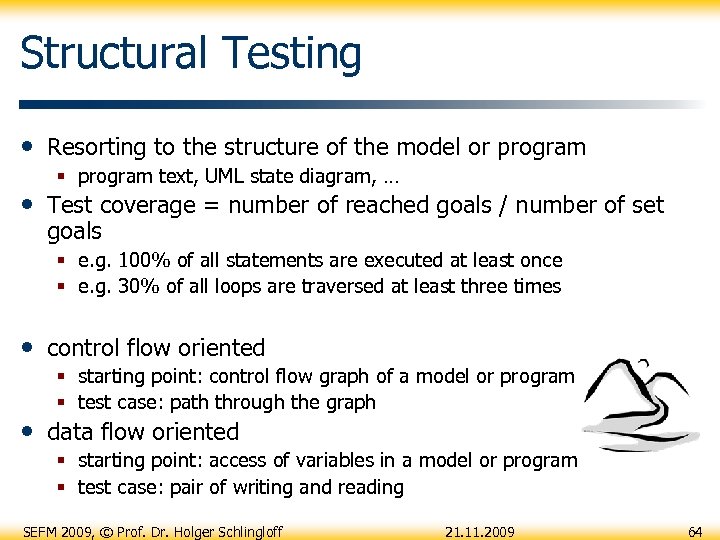

Structural Testing • Resorting to the structure of the model or program § program text, UML state diagram, … • Test coverage = number of reached goals / number of set goals § e. g. 100% of all statements are executed at least once § e. g. 30% of all loops are traversed at least three times • control flow oriented § starting point: control flow graph of a model or program § test case: path through the graph • data flow oriented § starting point: access of variables in a model or program § test case: pair of writing and reading SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 64

Structural Testing • Resorting to the structure of the model or program § program text, UML state diagram, … • Test coverage = number of reached goals / number of set goals § e. g. 100% of all statements are executed at least once § e. g. 30% of all loops are traversed at least three times • control flow oriented § starting point: control flow graph of a model or program § test case: path through the graph • data flow oriented § starting point: access of variables in a model or program § test case: pair of writing and reading SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 64

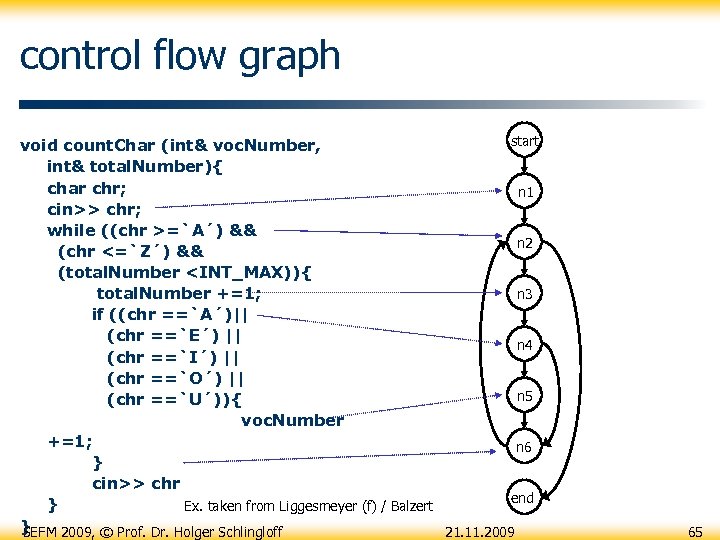

control flow graph start void count. Char (int& voc. Number, int& total. Number){ char chr; n 1 cin>> chr; while ((chr >=`A´) && n 2 (chr <=`Z´) && (total. Number

control flow graph start void count. Char (int& voc. Number, int& total. Number){ char chr; n 1 cin>> chr; while ((chr >=`A´) && n 2 (chr <=`Z´) && (total. Number

Coverage • Criteria § statement coverage § branch coverage § condition coverage - simple condition coverage - multiple condition coverage - minimal condition coverage § path coverage SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 66

Coverage • Criteria § statement coverage § branch coverage § condition coverage - simple condition coverage - multiple condition coverage - minimal condition coverage § path coverage SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 66

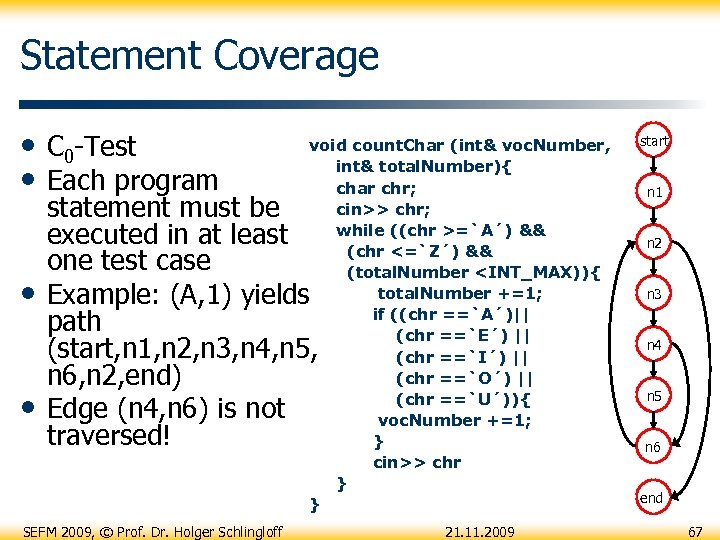

Statement Coverage • C 0 -Test • Each program • • void count. Char (int& voc. Number, int& total. Number){ char chr; cin>> chr; while ((chr >=`A´) && (chr <=`Z´) && (total. Number

Statement Coverage • C 0 -Test • Each program • • void count. Char (int& voc. Number, int& total. Number){ char chr; cin>> chr; while ((chr >=`A´) && (chr <=`Z´) && (total. Number

Critique Statement Coverage • Often „complete statement coverage“ is the absolutely minimal criterium for the construction of a test suite § in theory it is an undecidable problem whether a certain statement is reachable at all! • Percentage measured in number of reached / number of all program statement; (desirable: 100%) • • E. g. in DO-178 B (above level C) Often used, easy to calculate Weak criterion (18% discovered errors) E. g. (x>5) for (x>=5) not discovered SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 68

Critique Statement Coverage • Often „complete statement coverage“ is the absolutely minimal criterium for the construction of a test suite § in theory it is an undecidable problem whether a certain statement is reachable at all! • Percentage measured in number of reached / number of all program statement; (desirable: 100%) • • E. g. in DO-178 B (above level C) Often used, easy to calculate Weak criterion (18% discovered errors) E. g. (x>5) for (x>=5) not discovered SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 68

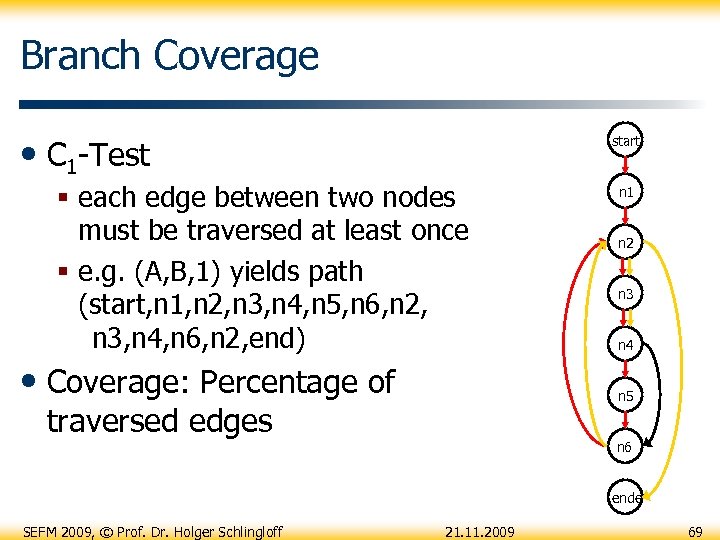

Branch Coverage • C 1 -Test start § each edge between two nodes must be traversed at least once § e. g. (A, B, 1) yields path (start, n 1, n 2, n 3, n 4, n 5, n 6, n 2, n 3, n 4, n 6, n 2, end) • Coverage: Percentage of n 1 n 2 n 3 n 4 n 5 traversed edges n 6 ende SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 69

Branch Coverage • C 1 -Test start § each edge between two nodes must be traversed at least once § e. g. (A, B, 1) yields path (start, n 1, n 2, n 3, n 4, n 5, n 6, n 2, n 3, n 4, n 6, n 2, end) • Coverage: Percentage of n 1 n 2 n 3 n 4 n 5 traversed edges n 6 ende SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 69

Critique Branch Coverage • Subsumes statement coverage • Still, loops are insufficiently tested (e. g. only once) • Each branching condition must be true in one and • false in another test case Edges can be weighted to correlate the coverage with the number of test cases • Well suited to find logical errors, not so well for data • errors Easy to implement with tool support (code annotation) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 70

Critique Branch Coverage • Subsumes statement coverage • Still, loops are insufficiently tested (e. g. only once) • Each branching condition must be true in one and • false in another test case Edges can be weighted to correlate the coverage with the number of test cases • Well suited to find logical errors, not so well for data • errors Easy to implement with tool support (code annotation) SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 70

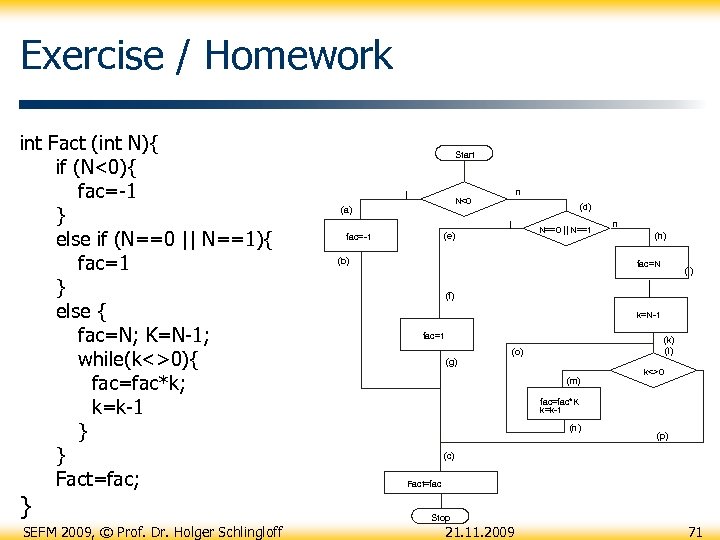

Exercise / Homework int Fact (int N){ if (N<0){ fac=-1 } else if (N==0 || N==1){ fac=1 } else { fac=N; K=N-1; while(k<>0){ fac=fac*k; k=k-1 } } Fact=fac; } SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff Start j n N<0 (a) (d) j (e) fac=-1 N==0 || N==1 (b) n (h) fac=N (j) (f) k=N-1 fac=1 (g) (k) (l) (o) (m) k<>0 fac=fac*K k=k-1 (n) (p) (c) Fact=fac Stop 21. 11. 2009 71

Exercise / Homework int Fact (int N){ if (N<0){ fac=-1 } else if (N==0 || N==1){ fac=1 } else { fac=N; K=N-1; while(k<>0){ fac=fac*k; k=k-1 } } Fact=fac; } SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff Start j n N<0 (a) (d) j (e) fac=-1 N==0 || N==1 (b) n (h) fac=N (j) (f) k=N-1 fac=1 (g) (k) (l) (o) (m) k<>0 fac=fac*K k=k-1 (n) (p) (c) Fact=fac Stop 21. 11. 2009 71

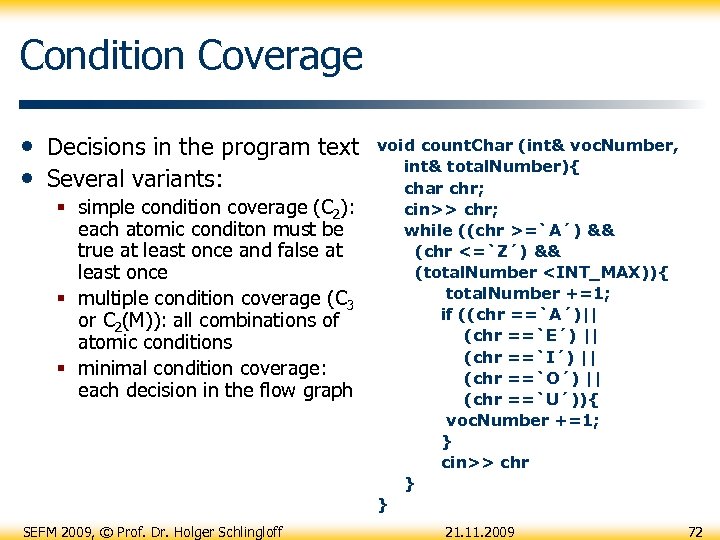

Condition Coverage • Decisions in the program text • Several variants: § simple condition coverage (C 2): each atomic conditon must be true at least once and false at least once § multiple condition coverage (C 3 or C 2(M)): all combinations of atomic conditions § minimal condition coverage: each decision in the flow graph SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff void count. Char (int& voc. Number, int& total. Number){ char chr; cin>> chr; while ((chr >=`A´) && (chr <=`Z´) && (total. Number

Condition Coverage • Decisions in the program text • Several variants: § simple condition coverage (C 2): each atomic conditon must be true at least once and false at least once § multiple condition coverage (C 3 or C 2(M)): all combinations of atomic conditions § minimal condition coverage: each decision in the flow graph SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff void count. Char (int& voc. Number, int& total. Number){ char chr; cin>> chr; while ((chr >=`A´) && (chr <=`Z´) && (total. Number

simple condition coverage • Each atomic conditon must be true at least once and false at least once § e. g. (p & q || r) yields six test cases • Condition coverage is often combined with branch coverage , so called condition/decision coverage • Problem: could be compiler dependent! (incomplete • • evaluation of conditions) Problem: how to control the program flow such that it yields the required conditions (dependent variables) Problem: total condition might be always the same SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 73

simple condition coverage • Each atomic conditon must be true at least once and false at least once § e. g. (p & q || r) yields six test cases • Condition coverage is often combined with branch coverage , so called condition/decision coverage • Problem: could be compiler dependent! (incomplete • • evaluation of conditions) Problem: how to control the program flow such that it yields the required conditions (dependent variables) Problem: total condition might be always the same SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 73

Multiple Condition Coverage • All variations of atomic conditions § e. g. (p & q || r) yields eight test cases • Total decision is guaranteed to vary • Exponentielly many possibilities • Problem: possible dependencies of variables! (e. g. (chr==`A´)||(chr==`E´)) can not both be true) • Not a feasible coverage criterion! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 74

Multiple Condition Coverage • All variations of atomic conditions § e. g. (p & q || r) yields eight test cases • Total decision is guaranteed to vary • Exponentielly many possibilities • Problem: possible dependencies of variables! (e. g. (chr==`A´)||(chr==`E´)) can not both be true) • Not a feasible coverage criterion! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 74

Minimal Condition Coverage • Evaluation with respect to the structure of the formula (each • • • subformula true and false) compound decisions will be evaluated compoundly problem: ((A&&B)||C) is covered by (www) and (fff), but not tested satisfactorily Modification: additional proof that each atomic decision is relevant (e. g. by one positive and one negative test case) • In combination with branch coverage used for flight critical software (MC/DC); most important coverage criterion to date SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 75

Minimal Condition Coverage • Evaluation with respect to the structure of the formula (each • • • subformula true and false) compound decisions will be evaluated compoundly problem: ((A&&B)||C) is covered by (www) and (fff), but not tested satisfactorily Modification: additional proof that each atomic decision is relevant (e. g. by one positive and one negative test case) • In combination with branch coverage used for flight critical software (MC/DC); most important coverage criterion to date SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 75

Path coverage • Each path through the control flow graph • In general there are infinitely many paths! • • (Coverage? ) Even if loops are restricted: „very many“ Structured path coverage: equivalence classes of paths (similar to boundary values) § each loop executed no time, one time, more than two times (boundary or interior condition) • Additionally manual constructed test cases • Tool support? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 76

Path coverage • Each path through the control flow graph • In general there are infinitely many paths! • • (Coverage? ) Even if loops are restricted: „very many“ Structured path coverage: equivalence classes of paths (similar to boundary values) § each loop executed no time, one time, more than two times (boundary or interior condition) • Additionally manual constructed test cases • Tool support? SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 76

Coverage Tools SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 77

Coverage Tools SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 77

Break! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 78

Break! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 78

Model-Based Testing • A technology where tests are generated from § finite state machines § UML state machine diagrams - potentially with class diagrams and/or OCL constraints § UML sequence or activity diagrams § Simulink diagrams § timed or hybrid automata SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 79

Model-Based Testing • A technology where tests are generated from § finite state machines § UML state machine diagrams - potentially with class diagrams and/or OCL constraints § UML sequence or activity diagrams § Simulink diagrams § timed or hybrid automata SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 79

Description of Systems • Finite automata have been known since the 1960’s § Moore / Mealy: used to describe relations between words (input sequence is transformed into output sequence) § Rabin / Scott: used to describe sets of words (accepting / non-accepting states) • Can be used to describe the control flow of any system § states are (equivalence classes of) configurations of the SUT § transitions are actions (external or internal) changing the state SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 80

Description of Systems • Finite automata have been known since the 1960’s § Moore / Mealy: used to describe relations between words (input sequence is transformed into output sequence) § Rabin / Scott: used to describe sets of words (accepting / non-accepting states) • Can be used to describe the control flow of any system § states are (equivalence classes of) configurations of the SUT § transitions are actions (external or internal) changing the state SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 80

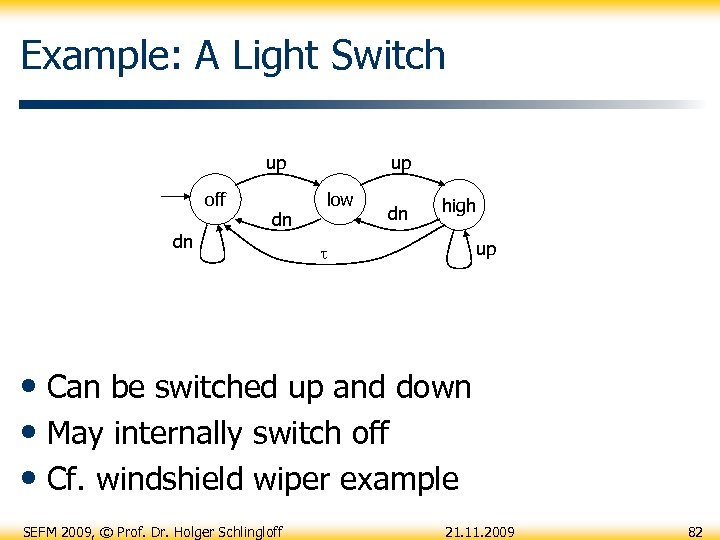

Labelled Transition Systems • “finite automaton without accepting states” • Formally: (S, L, T, s 0) § § S: finite or countable nonempty set of states L: finite set of labels, L transition relation T S (L { }) S s 0 initial state • Run=finite sequence {(silisi+1)i N}, where s 0 is the • • initial state and (silisi+1) T Trace = sequence of observable actions (labels ) of a run Undirected communication! Actions just “happen”! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 81

Labelled Transition Systems • “finite automaton without accepting states” • Formally: (S, L, T, s 0) § § S: finite or countable nonempty set of states L: finite set of labels, L transition relation T S (L { }) S s 0 initial state • Run=finite sequence {(silisi+1)i N}, where s 0 is the • • initial state and (silisi+1) T Trace = sequence of observable actions (labels ) of a run Undirected communication! Actions just “happen”! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 81

Example: A Light Switch up off dn dn up low dn high up • Can be switched up and down • May internally switch off • Cf. windshield wiper example SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 82

Example: A Light Switch up off dn dn up low dn high up • Can be switched up and down • May internally switch off • Cf. windshield wiper example SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 82

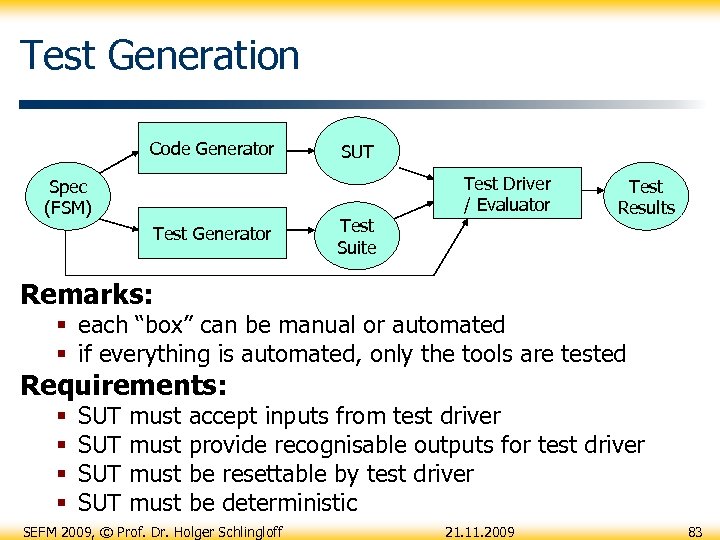

Test Generation Code Generator Spec (FSM) Test Generator SUT Test Suite Test Driver / Evaluator Test Results Remarks: § each “box” can be manual or automated § if everything is automated, only the tools are tested Requirements: § § SUT SUT must accept inputs from test driver provide recognisable outputs for test driver be resettable by test driver be deterministic SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 83

Test Generation Code Generator Spec (FSM) Test Generator SUT Test Suite Test Driver / Evaluator Test Results Remarks: § each “box” can be manual or automated § if everything is automated, only the tools are tested Requirements: § § SUT SUT must accept inputs from test driver provide recognisable outputs for test driver be resettable by test driver be deterministic SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 83

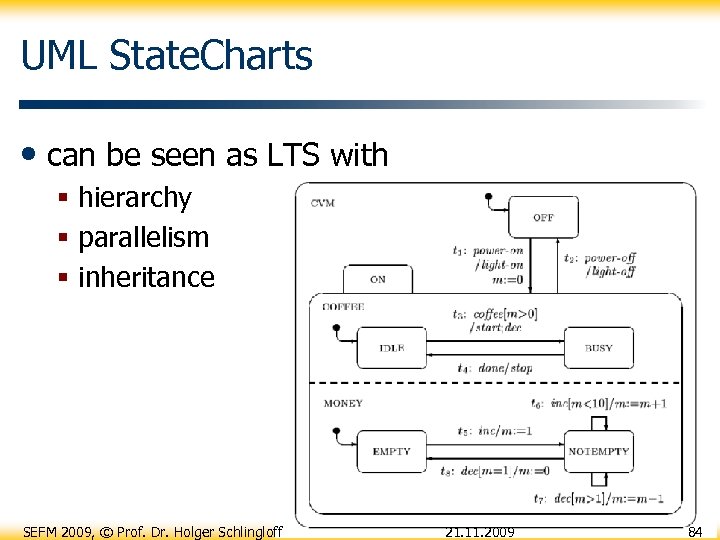

UML State. Charts • can be seen as LTS with § hierarchy § parallelism § inheritance SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 84

UML State. Charts • can be seen as LTS with § hierarchy § parallelism § inheritance SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 84

Parallelism • What is the meaning of parallelism in the specification? § structural: must be implemented in parallel § engineering: may be implemented in any order § pragmatic: will be implemented according to the tool’s scheduling strategy SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 85

Parallelism • What is the meaning of parallelism in the specification? § structural: must be implemented in parallel § engineering: may be implemented in any order § pragmatic: will be implemented according to the tool’s scheduling strategy SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 85

Test Generation from State. Charts • ATG (“automated test generator”): Add-on to the UML-tool Rhapsody by ILogix / IBM • First, the model is translated into C++ by the • • Rhapsody code generator Then, inputs and outputs to the model / SUT are identified Then, ATG constructs test cases from the generated code according to certain coverage goals § all states § all transitions § MC/DC SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 86

Test Generation from State. Charts • ATG (“automated test generator”): Add-on to the UML-tool Rhapsody by ILogix / IBM • First, the model is translated into C++ by the • • Rhapsody code generator Then, inputs and outputs to the model / SUT are identified Then, ATG constructs test cases from the generated code according to certain coverage goals § all states § all transitions § MC/DC SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 86

A “Real-Life” Example • A safety protocol for industrial automation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 87

A “Real-Life” Example • A safety protocol for industrial automation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 87

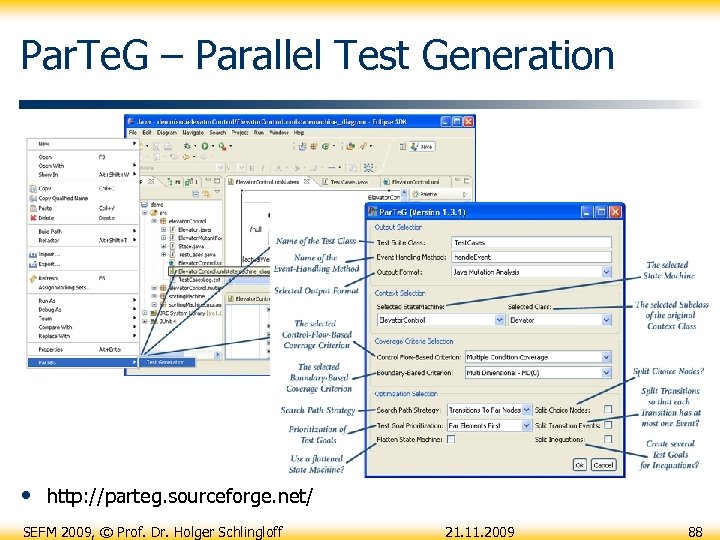

Par. Te. G – Parallel Test Generation • http: //parteg. sourceforge. net/ SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 88

Par. Te. G – Parallel Test Generation • http: //parteg. sourceforge. net/ SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 88

What have we learned? • Terms and definitions • Propositional modelling • Testing problems • Topics in testing • First-order formalisms, Z • Functional (unit) testing § test selection • Structural testing § test coverage • Model-based test generation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 89

What have we learned? • Terms and definitions • Propositional modelling • Testing problems • Topics in testing • First-order formalisms, Z • Functional (unit) testing § test selection • Structural testing § test coverage • Model-based test generation SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 89

That’s It! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 90

That’s It! SEFM 2009, © Prof. Dr. Holger Schlingloff 21. 11. 2009 90