6add50754d5ced4c5e297d0c4f1bfeec.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 30

LNGT 0101 Introduction to Linguistics Lecture #8 Oct 12 th, 2015

LNGT 0101 Introduction to Linguistics Lecture #8 Oct 12 th, 2015

Announcements • First episode of the Language Matters series is this Thursday Oct 15 at 4: 30 -5: 30 in Axinn 219. Take that quiz. 2

Announcements • First episode of the Language Matters series is this Thursday Oct 15 at 4: 30 -5: 30 in Axinn 219. Take that quiz. 2

Announcements • HW 1 average score: 48/50. Many thanks! • Corrections on homework writing: ‘This is prescriptive I. ’ • Typo in the dataset of Language Y: the word ‘magas’ should actually appear as ‘magasak’. • Any questions on HW #2? 3

Announcements • HW 1 average score: 48/50. Many thanks! • Corrections on homework writing: ‘This is prescriptive I. ’ • Typo in the dataset of Language Y: the word ‘magas’ should actually appear as ‘magasak’. • Any questions on HW #2? 3

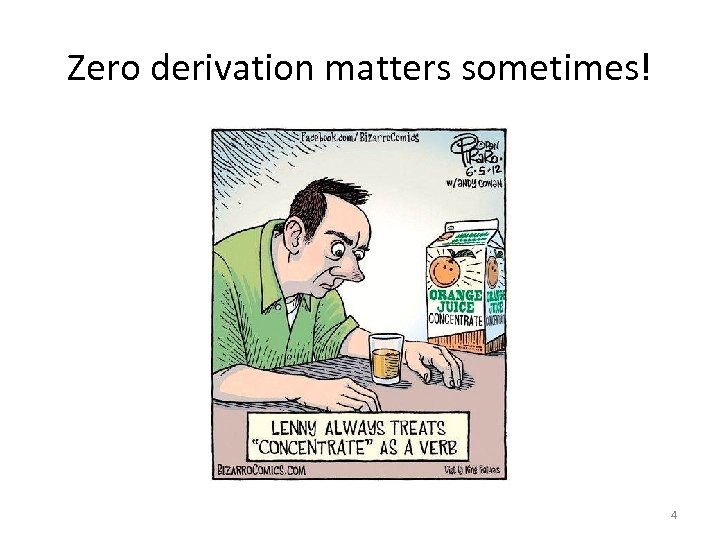

Zero derivation matters sometimes! 4

Zero derivation matters sometimes! 4

Cact-us vs. Cact-i 5

Cact-us vs. Cact-i 5

Processes of word formation - Derivation - Conversion - Compounding - Acronyms - Blending - Word coinage - Borrowing/Calques - Back-formation - Clipping - Eponyms 6

Processes of word formation - Derivation - Conversion - Compounding - Acronyms - Blending - Word coinage - Borrowing/Calques - Back-formation - Clipping - Eponyms 6

Acronyms • Acronyms are words created from the initial letters of several words. Typical examples are NATO, FBI, CIA, UNICEF, FAQ, WYSIWYG, radar, laser. • Sometimes acronyms are actually created first to match a word that already exists in the language, e. g. , MADD (Mothers against Drunk Drivers). • Common in social media today. 7

Acronyms • Acronyms are words created from the initial letters of several words. Typical examples are NATO, FBI, CIA, UNICEF, FAQ, WYSIWYG, radar, laser. • Sometimes acronyms are actually created first to match a word that already exists in the language, e. g. , MADD (Mothers against Drunk Drivers). • Common in social media today. 7

Clipping • Another process of word-formation is clipping, which is the shortening of a longer word. Clipping in English gave rise to words such as fax from facsimile, gym from gymnasium, and lab from laboratory. 8

Clipping • Another process of word-formation is clipping, which is the shortening of a longer word. Clipping in English gave rise to words such as fax from facsimile, gym from gymnasium, and lab from laboratory. 8

Blending • Blending is another way of combining two words to form a new word. The difference between blending and compounding, however, is that in blending only parts of the words, not the whole words, are combined. Here’s a couple of examples: smoke + fog smog motor + hotel motel information + commercial infomercial 9

Blending • Blending is another way of combining two words to form a new word. The difference between blending and compounding, however, is that in blending only parts of the words, not the whole words, are combined. Here’s a couple of examples: smoke + fog smog motor + hotel motel information + commercial infomercial 9

Eponyms • Eponyms are words derived from proper names, e. g. , “sandwich” from the Earl of Sandwich; “lynch” after William Lynch. • LINK 10

Eponyms • Eponyms are words derived from proper names, e. g. , “sandwich” from the Earl of Sandwich; “lynch” after William Lynch. • LINK 10

What process(es) is involved? • • Terra firma Webcam Facebook CEO Enabler Execs Blog (noun) and blog (verb) 11

What process(es) is involved? • • Terra firma Webcam Facebook CEO Enabler Execs Blog (noun) and blog (verb) 11

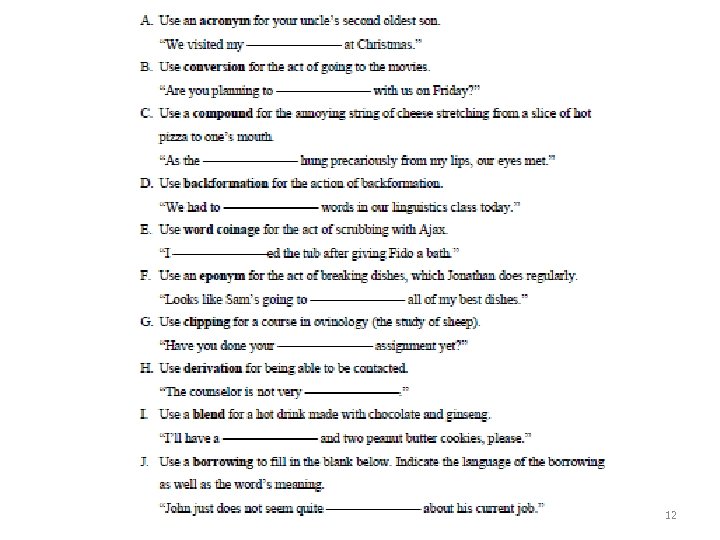

12

12

Morphological typology How do languages differ in their internal word structure? 13

Morphological typology How do languages differ in their internal word structure? 13

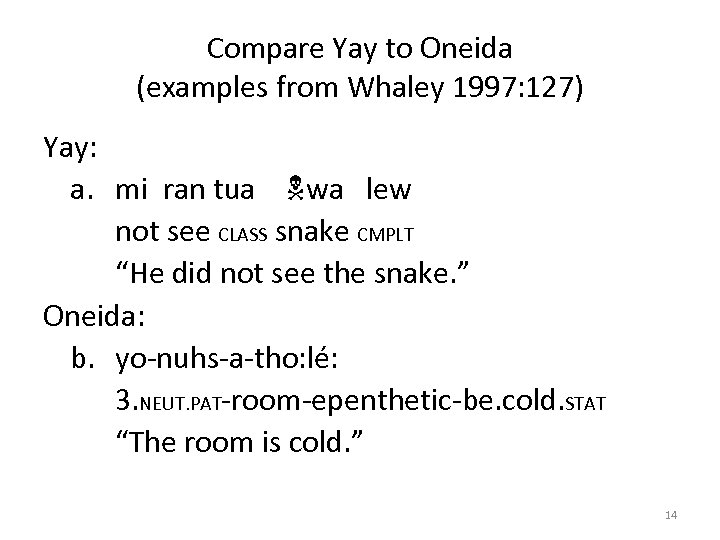

Compare Yay to Oneida (examples from Whaley 1997: 127) Yay: a. mi ran tua wa lew not see CLASS snake CMPLT “He did not see the snake. ” Oneida: b. yo-nuhs-a-tho: lé: 3. NEUT. PAT-room-epenthetic-be. cold. STAT “The room is cold. ” 14

Compare Yay to Oneida (examples from Whaley 1997: 127) Yay: a. mi ran tua wa lew not see CLASS snake CMPLT “He did not see the snake. ” Oneida: b. yo-nuhs-a-tho: lé: 3. NEUT. PAT-room-epenthetic-be. cold. STAT “The room is cold. ” 14

Synthesis: How many morphemes does your language have per word? • One aspect of morphological variation has to do with synthesis: Some languages choose to “stack” morphemes on top of one another within words; others elect to use at most one morpheme per word, and many others will fall somewhere between these two extremes. 15

Synthesis: How many morphemes does your language have per word? • One aspect of morphological variation has to do with synthesis: Some languages choose to “stack” morphemes on top of one another within words; others elect to use at most one morpheme per word, and many others will fall somewhere between these two extremes. 15

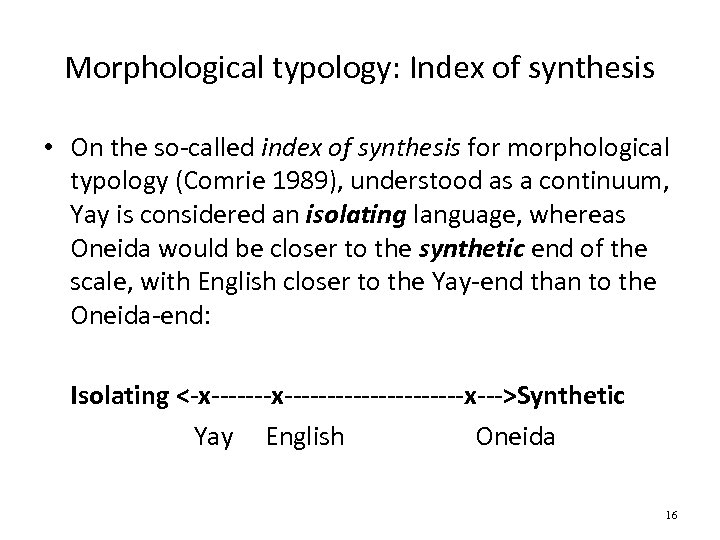

Morphological typology: Index of synthesis • On the so-called index of synthesis for morphological typology (Comrie 1989), understood as a continuum, Yay is considered an isolating language, whereas Oneida would be closer to the synthetic end of the scale, with English closer to the Yay-end than to the Oneida-end: Isolating <-x--------------x--->Synthetic Yay English Oneida 16

Morphological typology: Index of synthesis • On the so-called index of synthesis for morphological typology (Comrie 1989), understood as a continuum, Yay is considered an isolating language, whereas Oneida would be closer to the synthetic end of the scale, with English closer to the Yay-end than to the Oneida-end: Isolating <-x--------------x--->Synthetic Yay English Oneida 16

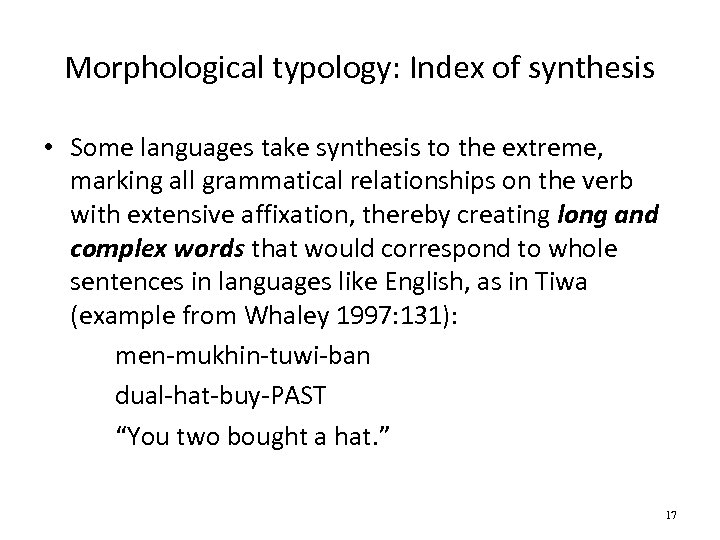

Morphological typology: Index of synthesis • Some languages take synthesis to the extreme, marking all grammatical relationships on the verb with extensive affixation, thereby creating long and complex words that would correspond to whole sentences in languages like English, as in Tiwa (example from Whaley 1997: 131): men-mukhin-tuwi-ban dual-hat-buy-PAST “You two bought a hat. ” 17

Morphological typology: Index of synthesis • Some languages take synthesis to the extreme, marking all grammatical relationships on the verb with extensive affixation, thereby creating long and complex words that would correspond to whole sentences in languages like English, as in Tiwa (example from Whaley 1997: 131): men-mukhin-tuwi-ban dual-hat-buy-PAST “You two bought a hat. ” 17

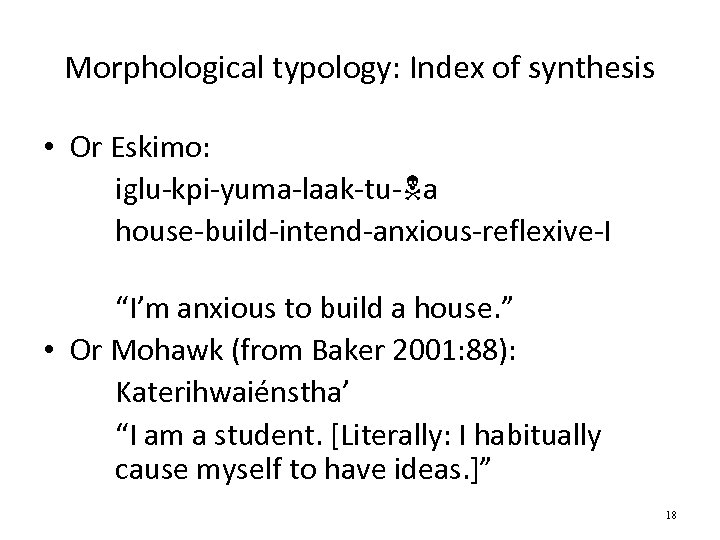

Morphological typology: Index of synthesis • Or Eskimo: iglu-kpi-yuma-laak-tu- a house-build-intend-anxious-reflexive-I “I’m anxious to build a house. ” • Or Mohawk (from Baker 2001: 88): Katerihwaiénstha’ “I am a student. [Literally: I habitually cause myself to have ideas. ]” 18

Morphological typology: Index of synthesis • Or Eskimo: iglu-kpi-yuma-laak-tu- a house-build-intend-anxious-reflexive-I “I’m anxious to build a house. ” • Or Mohawk (from Baker 2001: 88): Katerihwaiénstha’ “I am a student. [Literally: I habitually cause myself to have ideas. ]” 18

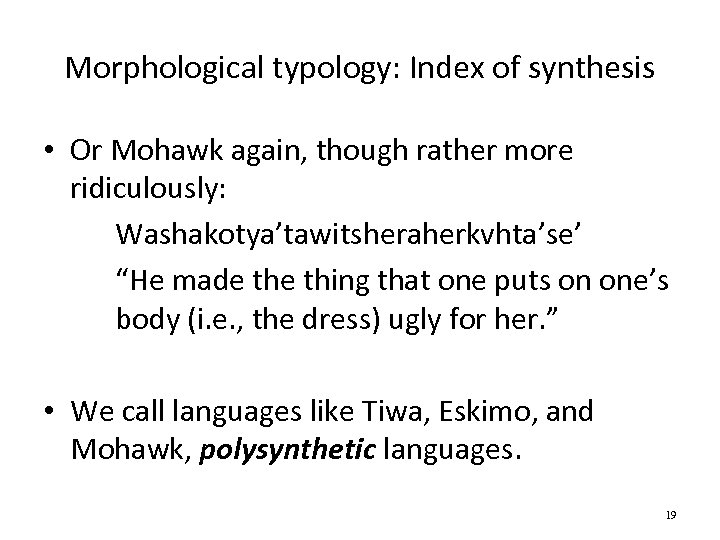

Morphological typology: Index of synthesis • Or Mohawk again, though rather more ridiculously: Washakotya’tawitsheraherkvhta’se’ “He made thing that one puts on one’s body (i. e. , the dress) ugly for her. ” • We call languages like Tiwa, Eskimo, and Mohawk, polysynthetic languages. 19

Morphological typology: Index of synthesis • Or Mohawk again, though rather more ridiculously: Washakotya’tawitsheraherkvhta’se’ “He made thing that one puts on one’s body (i. e. , the dress) ugly for her. ” • We call languages like Tiwa, Eskimo, and Mohawk, polysynthetic languages. 19

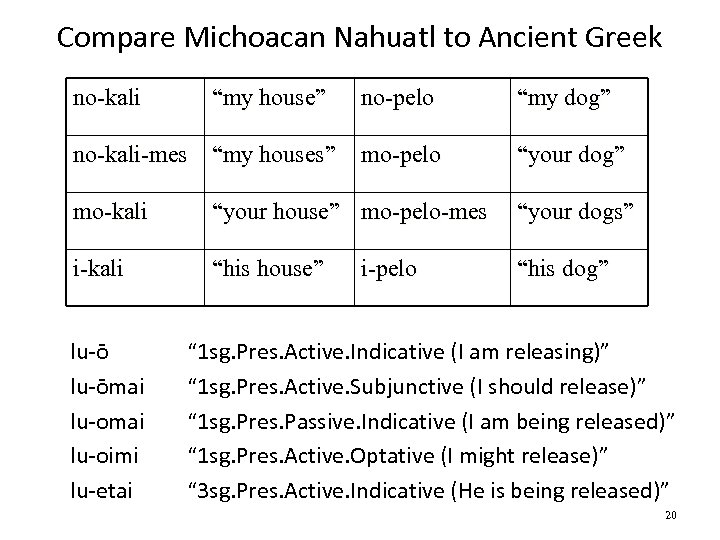

Compare Michoacan Nahuatl to Ancient Greek no-kali “my house” no-kali-mes “my houses” no-pelo “my dog” mo-pelo “your dog” mo-kali “your house” mo-pelo-mes “your dogs” i-kali “his house” “his dog” lu-ōmai lu-oimi lu-etai i-pelo “ 1 sg. Pres. Active. Indicative (I am releasing)” “ 1 sg. Pres. Active. Subjunctive (I should release)” “ 1 sg. Pres. Passive. Indicative (I am being released)” “ 1 sg. Pres. Active. Optative (I might release)” “ 3 sg. Pres. Active. Indicative (He is being released)” 20

Compare Michoacan Nahuatl to Ancient Greek no-kali “my house” no-kali-mes “my houses” no-pelo “my dog” mo-pelo “your dog” mo-kali “your house” mo-pelo-mes “your dogs” i-kali “his house” “his dog” lu-ōmai lu-oimi lu-etai i-pelo “ 1 sg. Pres. Active. Indicative (I am releasing)” “ 1 sg. Pres. Active. Subjunctive (I should release)” “ 1 sg. Pres. Passive. Indicative (I am being released)” “ 1 sg. Pres. Active. Optative (I might release)” “ 3 sg. Pres. Active. Indicative (He is being released)” 20

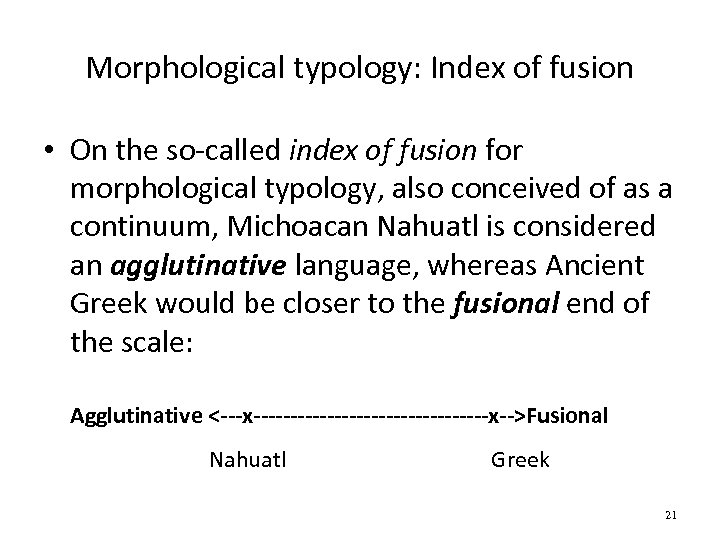

Morphological typology: Index of fusion • On the so-called index of fusion for morphological typology, also conceived of as a continuum, Michoacan Nahuatl is considered an agglutinative language, whereas Ancient Greek would be closer to the fusional end of the scale: Agglutinative <---x----------------x-->Fusional Nahuatl Greek 21

Morphological typology: Index of fusion • On the so-called index of fusion for morphological typology, also conceived of as a continuum, Michoacan Nahuatl is considered an agglutinative language, whereas Ancient Greek would be closer to the fusional end of the scale: Agglutinative <---x----------------x-->Fusional Nahuatl Greek 21

Any remaining issues on morphology? • There’s obviously plenty we have not covered. Interested to learn more? You can sign up for LNGT 0250 in the Spring! 22

Any remaining issues on morphology? • There’s obviously plenty we have not covered. Interested to learn more? You can sign up for LNGT 0250 in the Spring! 22

What’s syntax? SYNTAX is the study of sentence structure in human language. 23

What’s syntax? SYNTAX is the study of sentence structure in human language. 23

Syntax • Whether you’re a native speaker or a nonspeaker, what are some things about sentence structure in English that you find peculiar? Think of things that speakers of other languages would consider hard to learn. • What are some things about sentence structure in other languages that strike you as peculiar? 24

Syntax • Whether you’re a native speaker or a nonspeaker, what are some things about sentence structure in English that you find peculiar? Think of things that speakers of other languages would consider hard to learn. • What are some things about sentence structure in other languages that strike you as peculiar? 24

Syntax • What do we know when we know the syntax of our language? • There are several aspects of syntactic knowledge that native speakers have about their language. • Let’s look at some examples and reflect a little. 25

Syntax • What do we know when we know the syntax of our language? • There are several aspects of syntactic knowledge that native speakers have about their language. • Let’s look at some examples and reflect a little. 25

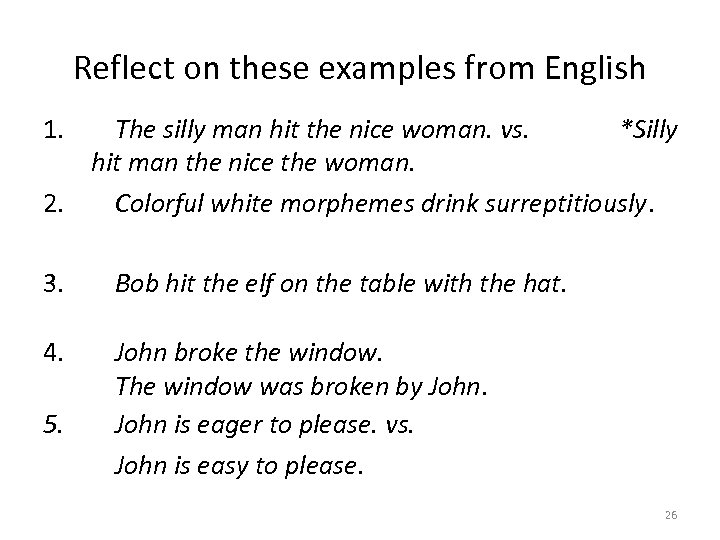

Reflect on these examples from English 1. The silly man hit the nice woman. vs. *Silly hit man the nice the woman. 2. Colorful white morphemes drink surreptitiously. 3. Bob hit the elf on the table with the hat. 4. John broke the window. The window was broken by John is eager to please. vs. John is easy to please. 5. 26

Reflect on these examples from English 1. The silly man hit the nice woman. vs. *Silly hit man the nice the woman. 2. Colorful white morphemes drink surreptitiously. 3. Bob hit the elf on the table with the hat. 4. John broke the window. The window was broken by John is eager to please. vs. John is easy to please. 5. 26

Reflect on these examples from English 6. a. The linguist knows that this language has become extinct. b. The biologist believes that the linguist knows that this language has become extinct. c. The neuroscientist claims that the biologist believes that the linguist knows that this language has become extinct. d. etc. 27

Reflect on these examples from English 6. a. The linguist knows that this language has become extinct. b. The biologist believes that the linguist knows that this language has become extinct. c. The neuroscientist claims that the biologist believes that the linguist knows that this language has become extinct. d. etc. 27

So, we know: • What is grammatical and what is ungrammatical. • Grammaticality is not dependent on meaningfulness. • The same string of words can give rise to multiple meanings. • Structures can look different but mean roughly the same thing. • Structures can look the same but have completely different meanings. • Structures can go ad infinitum, in theory. 28

So, we know: • What is grammatical and what is ungrammatical. • Grammaticality is not dependent on meaningfulness. • The same string of words can give rise to multiple meanings. • Structures can look different but mean roughly the same thing. • Structures can look the same but have completely different meanings. • Structures can go ad infinitum, in theory. 28

Syntax • For our theory of grammar to be adequate, it has to account for these different aspects of native speakers’ subconscious syntactic knowledge. • We start talking about this on Wednesday. 29

Syntax • For our theory of grammar to be adequate, it has to account for these different aspects of native speakers’ subconscious syntactic knowledge. • We start talking about this on Wednesday. 29

Next class agenda • Constituency: Finish reading pp. 76 -87 of Chapter 3 if you haven’t already. • Read Chapter 3, pp. 87 - 108, on phrase structure grammar and syntactic trees. 30

Next class agenda • Constituency: Finish reading pp. 76 -87 of Chapter 3 if you haven’t already. • Read Chapter 3, pp. 87 - 108, on phrase structure grammar and syntactic trees. 30