69b3e51db7b157fa6e654b98ac6a415c.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 24

LING 001 Language Acquisition II 3 -17 -2010

LING 001 Language Acquisition II 3 -17 -2010

The study of child language • • Striving for a universal theory What goes in: • • What comes out: • • • recordings, transcripts experimental approaches: less demanding of the child What goes on inside • • mode of child-adult interaction mechanisms vs. descriptions (e. g. , stages) Two case studies: word segmentation and English past tense

The study of child language • • Striving for a universal theory What goes in: • • What comes out: • • • recordings, transcripts experimental approaches: less demanding of the child What goes on inside • • mode of child-adult interaction mechanisms vs. descriptions (e. g. , stages) Two case studies: word segmentation and English past tense

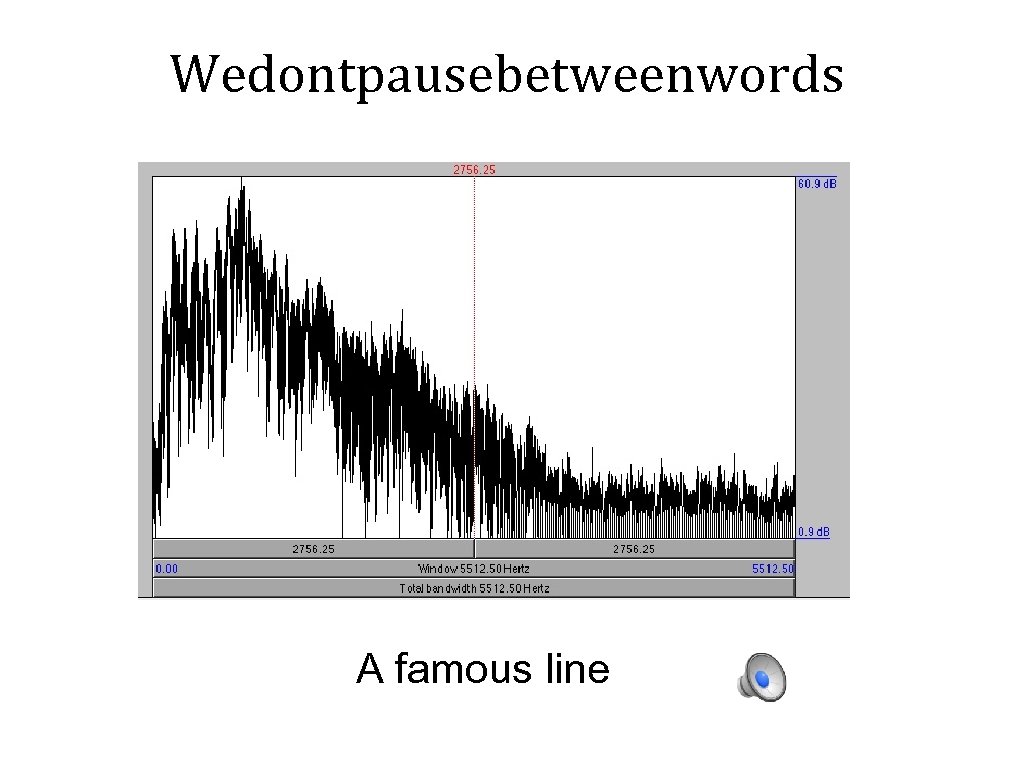

Wedontpausebetweenwords A famous line

Wedontpausebetweenwords A famous line

Word Segmentation • • • Recognize familiar sounds/words retain these sounds in the long-term memory of words (the LEXICON) Infants begin to do so at 7. 5 month • • more attention to familiar words/sounds Many mechanisms of segmentation have been proposed

Word Segmentation • • • Recognize familiar sounds/words retain these sounds in the long-term memory of words (the LEXICON) Infants begin to do so at 7. 5 month • • more attention to familiar words/sounds Many mechanisms of segmentation have been proposed

Isolated Words • • Up to 9 -10% of sentences in spoken English (to children) are single words (“drink”, “here? ”, “up!”), and these words tend to be learned faster But how does the infant know so? Longer utterances may be a single word (“spaghetti”), but shorter utterances may consist of multiple words (“Isee”)

Isolated Words • • Up to 9 -10% of sentences in spoken English (to children) are single words (“drink”, “here? ”, “up!”), and these words tend to be learned faster But how does the infant know so? Longer utterances may be a single word (“spaghetti”), but shorter utterances may consist of multiple words (“Isee”)

Stress cues • • 82 -90% English content words are stress initial when you hear a stressed syllable, you say that’s a new word, and you’d 82 -90% words right 7. 5 month olds prefer kingdom, hamlet, over device and guitar Problem: chicken and egg? • How does the child learn this to begin with? Not all languages have the stress pattern of English

Stress cues • • 82 -90% English content words are stress initial when you hear a stressed syllable, you say that’s a new word, and you’d 82 -90% words right 7. 5 month olds prefer kingdom, hamlet, over device and guitar Problem: chicken and egg? • How does the child learn this to begin with? Not all languages have the stress pattern of English

Memory • Need memory: storage in the lexicon • • can store sounds--not words yet--at 7. 5 months (Jusczyk & Hohne 1997) stories containing “vine”, “python”, “jungle”, infants listen longer to passages containing words with prior experience how do children extract pre-analyzed speech materials into words?

Memory • Need memory: storage in the lexicon • • can store sounds--not words yet--at 7. 5 months (Jusczyk & Hohne 1997) stories containing “vine”, “python”, “jungle”, infants listen longer to passages containing words with prior experience how do children extract pre-analyzed speech materials into words?

Statistical Learning • Infants can gather statistics in speech to extract words • • Chomsky (1955): P(A→B), transitional probability, is a good indicator of what word boundaries can be found • • this strategy is not specific to any language Prob(A→B) = (# of B’s following A)/ (# of everything following A) pre→tty → ba → by P(pre→tty)>P(tty→ba)

Statistical Learning • Infants can gather statistics in speech to extract words • • Chomsky (1955): P(A→B), transitional probability, is a good indicator of what word boundaries can be found • • this strategy is not specific to any language Prob(A→B) = (# of B’s following A)/ (# of everything following A) pre→tty → ba → by P(pre→tty)>P(tty→ba)

padoti vs. dotigo babies prefer high-transitional-probability strings of syllables But does it work?

padoti vs. dotigo babies prefer high-transitional-probability strings of syllables But does it work?

Statistical Learning of English • • If we look at real data to children, statistical learning clearly doesn’t work: only 41. 6% of “words” thus extracted are real words, but close to 80% of real words are not extracted The reason: most words in spoken English can monosyllabic: • 85% of time, a monosyllabic word is immediately The Cat in the Hat followed by another one The Sun did not shine. It was too wet to play. So we sat in the house All that cold, wet day. Too wet to go out And too cold to play ball. So we sat in the house. We did nothing at all. I sat there with Sally. We sat there, we two. And I said, “How I wish We had something to do!” So all we could do was to Sit! And we did not like it. Not one little bit.

Statistical Learning of English • • If we look at real data to children, statistical learning clearly doesn’t work: only 41. 6% of “words” thus extracted are real words, but close to 80% of real words are not extracted The reason: most words in spoken English can monosyllabic: • 85% of time, a monosyllabic word is immediately The Cat in the Hat followed by another one The Sun did not shine. It was too wet to play. So we sat in the house All that cold, wet day. Too wet to go out And too cold to play ball. So we sat in the house. We did nothing at all. I sat there with Sally. We sat there, we two. And I said, “How I wish We had something to do!” So all we could do was to Sit! And we did not like it. Not one little bit.

Constraints on Wordhood • Words have stress: a word cannot have more than one primary stress • • darthvader vs. chewbecca If the child knows this, “b. Igb. Adw. Olf” breaks up into 3 words for free And children are perceptually prepared to do this: recall that 7. 5 month-olds can detect primary stress (Jusczyk, Hohne, & Baumann 1999, J, Johnson, & Newsome 1999) Note that we do NOT need to use language-particular patterns, unlike the multiple cue approach (Jusczyk 1999)

Constraints on Wordhood • Words have stress: a word cannot have more than one primary stress • • darthvader vs. chewbecca If the child knows this, “b. Igb. Adw. Olf” breaks up into 3 words for free And children are perceptually prepared to do this: recall that 7. 5 month-olds can detect primary stress (Jusczyk, Hohne, & Baumann 1999, J, Johnson, & Newsome 1999) Note that we do NOT need to use language-particular patterns, unlike the multiple cue approach (Jusczyk 1999)

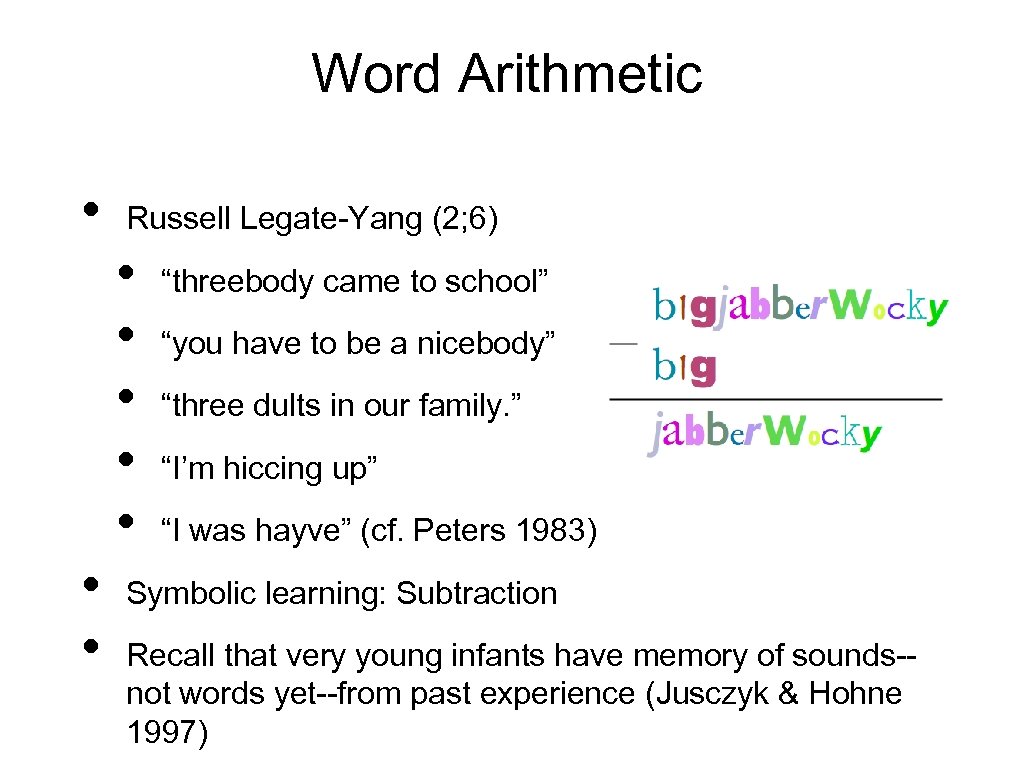

Word Arithmetic • Russell Legate-Yang (2; 6) • • “threebody came to school” “you have to be a nicebody” “three dults in our family. ” “I’m hiccing up” “I was hayve” (cf. Peters 1983) Symbolic learning: Subtraction Recall that very young infants have memory of sounds-not words yet--from past experience (Jusczyk & Hohne 1997)

Word Arithmetic • Russell Legate-Yang (2; 6) • • “threebody came to school” “you have to be a nicebody” “three dults in our family. ” “I’m hiccing up” “I was hayve” (cf. Peters 1983) Symbolic learning: Subtraction Recall that very young infants have memory of sounds-not words yet--from past experience (Jusczyk & Hohne 1997)

“Experiment” • • • Subject: RLY (2; 10) C: “Look! Tulips!” RLY: “Three lips! One is just a baby. ”

“Experiment” • • • Subject: RLY (2; 10) C: “Look! Tulips!” RLY: “Three lips! One is just a baby. ”

Mommy & Me • • 6 -month-olds can use familiar words to extract new words (Bortfeld et al. 2006) XY (X: familiar word; Y: novel word) vs. ZY (both novel) • • “Mommy bike” vs. “Sturdy bike” Can extract Y with X, but not with Z • children exposed to “Mommy bike” show recognition of “bike” but those exposed to “Sturdy bike” do not

Mommy & Me • • 6 -month-olds can use familiar words to extract new words (Bortfeld et al. 2006) XY (X: familiar word; Y: novel word) vs. ZY (both novel) • • “Mommy bike” vs. “Sturdy bike” Can extract Y with X, but not with Z • children exposed to “Mommy bike” show recognition of “bike” but those exposed to “Sturdy bike” do not

Summary • • Children use prosody to follow the pattern of speech Brute-force statistical pattern finding does not scale up • beware of the gaps between lab results and real learning settings

Summary • • Children use prosody to follow the pattern of speech Brute-force statistical pattern finding does not scale up • beware of the gaps between lab results and real learning settings

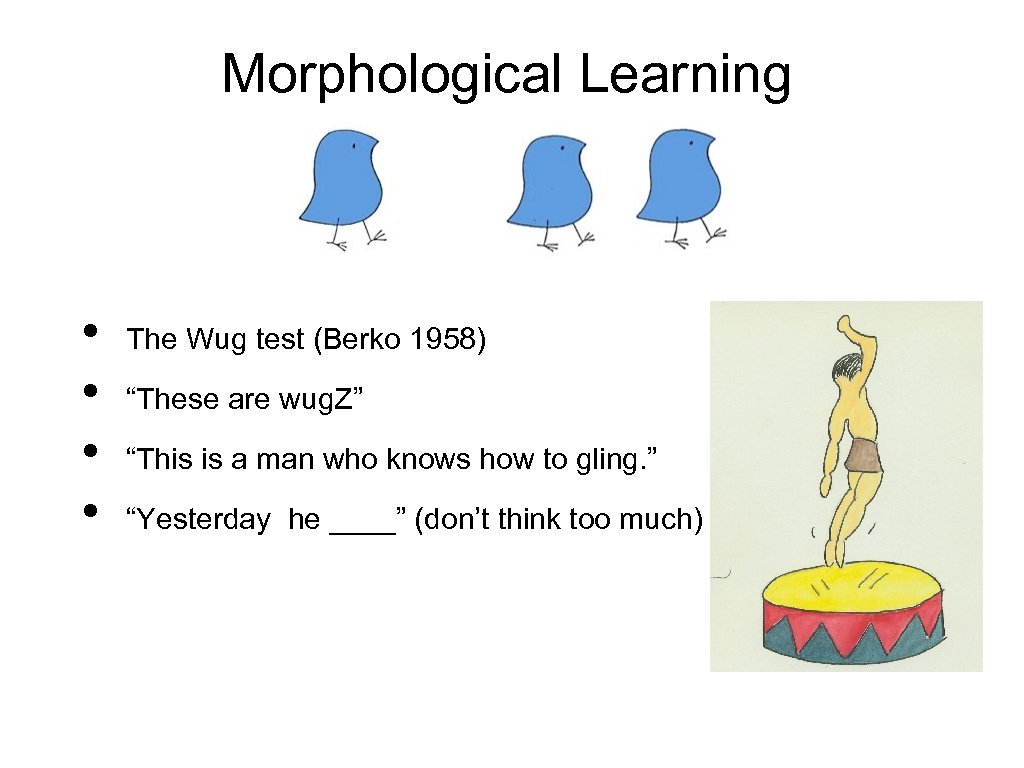

Morphological Learning • • The Wug test (Berko 1958) “These are wug. Z” “This is a man who knows how to gling. ” “Yesterday he ____” (don’t think too much)

Morphological Learning • • The Wug test (Berko 1958) “These are wug. Z” “This is a man who knows how to gling. ” “Yesterday he ____” (don’t think too much)

• • The Global View Basically, the more complex a morphology is, the better children are at learning it Italian, Spanish, and Catalan speaking children use singular agreement with the appropriate subject • • Plural agreement morphemes are initially absent, and appear a couple of months after singulars Errors are very rare and occur almost always for plurals By 1; 8 -1; 10 (first stage of multiple word combinations), I/C/S children use all morphemes up to 90% (correctly) in obligatory contexts When they don’t, it’s usually errors of omission (not using it, or using a default one) not substitution (e. g. , using 1 st person for 3 rd person)

• • The Global View Basically, the more complex a morphology is, the better children are at learning it Italian, Spanish, and Catalan speaking children use singular agreement with the appropriate subject • • Plural agreement morphemes are initially absent, and appear a couple of months after singulars Errors are very rare and occur almost always for plurals By 1; 8 -1; 10 (first stage of multiple word combinations), I/C/S children use all morphemes up to 90% (correctly) in obligatory contexts When they don’t, it’s usually errors of omission (not using it, or using a default one) not substitution (e. g. , using 1 st person for 3 rd person)

English Past Tense • • Is consistent with the general pattern across languages Overregularization: Children quite frequently use the -ed form on irregular verbs (“hold-holded”, “go-goed”), about 10% of all irregular verb past tense Over-irregularization: virtually absent (“bring-brang”, “thinkthunk” <0. 2%; many conceivable errors never occur) Even broad contexts: exceptions and regularities are the essence of language

English Past Tense • • Is consistent with the general pattern across languages Overregularization: Children quite frequently use the -ed form on irregular verbs (“hold-holded”, “go-goed”), about 10% of all irregular verb past tense Over-irregularization: virtually absent (“bring-brang”, “thinkthunk” <0. 2%; many conceivable errors never occur) Even broad contexts: exceptions and regularities are the essence of language

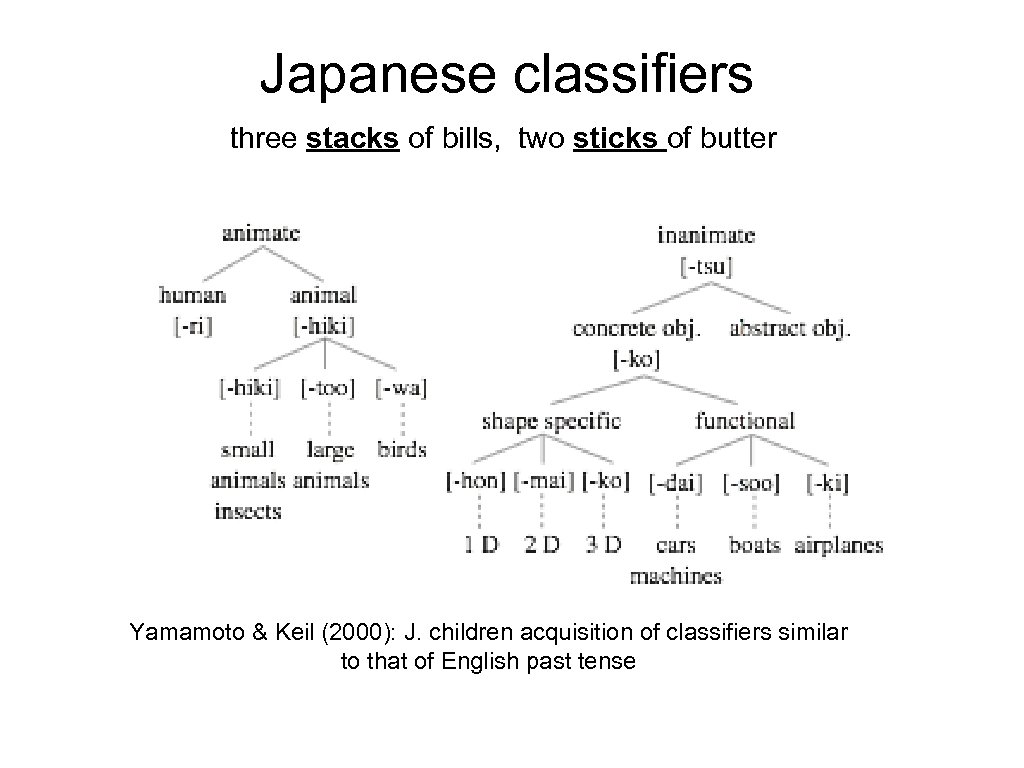

Japanese classifiers three stacks of bills, two sticks of butter Yamamoto & Keil (2000): J. children acquisition of classifiers similar to that of English past tense

Japanese classifiers three stacks of bills, two sticks of butter Yamamoto & Keil (2000): J. children acquisition of classifiers similar to that of English past tense

Overregularization • Result of failing to receive the memorized forms of irregular verbs • • irregulars are by definition unpredictable so they can only be learned by repeated exposure high frequency irregulars tend to be learned better than low frequency ones • what’s the past tense of “cleave”? what’s the stem form of “wrought”?

Overregularization • Result of failing to receive the memorized forms of irregular verbs • • irregulars are by definition unpredictable so they can only be learned by repeated exposure high frequency irregulars tend to be learned better than low frequency ones • what’s the past tense of “cleave”? what’s the stem form of “wrought”?

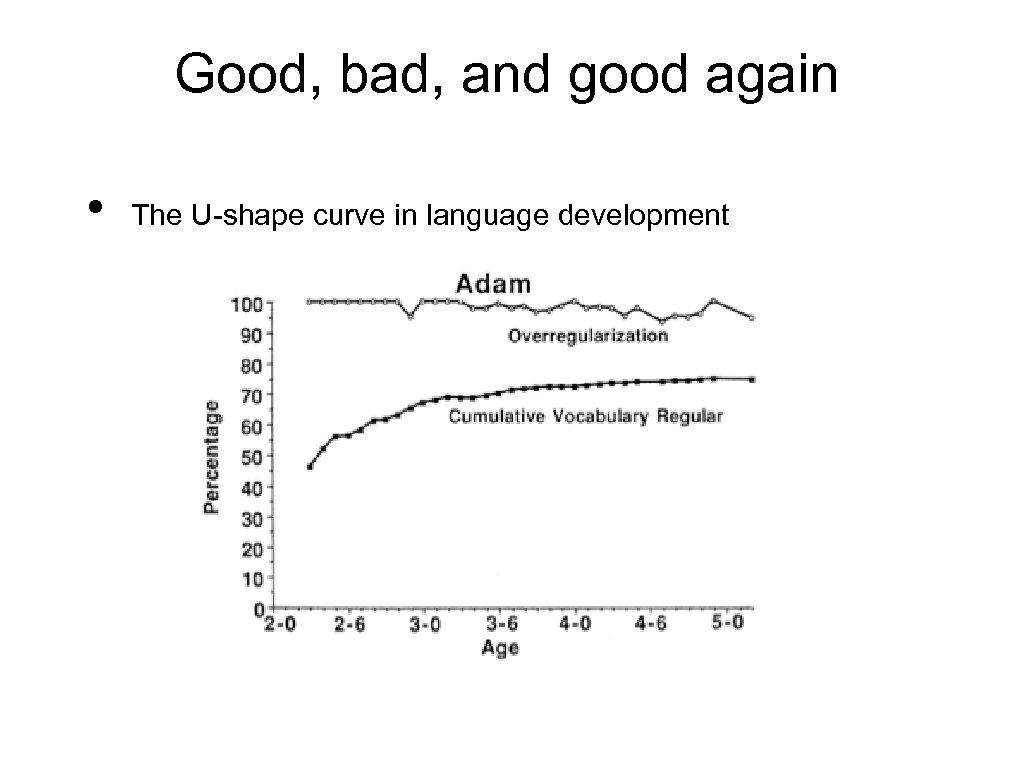

Good, bad, and good again • The U-shape curve in language development

Good, bad, and good again • The U-shape curve in language development

Explanation • Initially, children haven’t learned the -ed rule yet • • • at this point, they would not make irregular errors but there is not opportunity for overapplication yet regular verbs are less frequent than irregulars and tend to be learned later the child needs to learn a fair amount of regulars to know the “batting average” of “add -d” is good enough! After -ed rule becomes operative, children will start making overregularization errors As memory for irregulars gets stronger, the errors will gradually disappear

Explanation • Initially, children haven’t learned the -ed rule yet • • • at this point, they would not make irregular errors but there is not opportunity for overapplication yet regular verbs are less frequent than irregulars and tend to be learned later the child needs to learn a fair amount of regulars to know the “batting average” of “add -d” is good enough! After -ed rule becomes operative, children will start making overregularization errors As memory for irregulars gets stronger, the errors will gradually disappear

More questions • How does the child know “held” blocks “holded”? • • Well, they have never heard “holded”: but absence of evidence is is not evidence of absence (e. g. , Wug test) One possibility is that the blocking effect (more specific form trumps more general form) is an innate principle of language and cognition finger or thumb

More questions • How does the child know “held” blocks “holded”? • • Well, they have never heard “holded”: but absence of evidence is is not evidence of absence (e. g. , Wug test) One possibility is that the blocking effect (more specific form trumps more general form) is an innate principle of language and cognition finger or thumb

More questions • Learning rules: • • • what they are: “add -d to verbs” how generally they apply: “add -d” vs. “change i to a” (singsang) rules are language specific so universal principles of morphology must be plastic enough to adapt to particular languages

More questions • Learning rules: • • • what they are: “add -d to verbs” how generally they apply: “add -d” vs. “change i to a” (singsang) rules are language specific so universal principles of morphology must be plastic enough to adapt to particular languages