khrushchev reforms.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 32

Lecture VII: KHRUSHCHOV‘S REFORMS AND THEIR FAILURE

Lecture VII: KHRUSHCHOV‘S REFORMS AND THEIR FAILURE

Contents list: I. Fighting for power after Stalin's death. Khrushchov's victory II. XXth Congress of the CPSU - denouncement of Stalin's personality cult III. Khrushchov's political and economical reforms. Reasons of their failure IV. Khrushchov's discharge

Contents list: I. Fighting for power after Stalin's death. Khrushchov's victory II. XXth Congress of the CPSU - denouncement of Stalin's personality cult III. Khrushchov's political and economical reforms. Reasons of their failure IV. Khrushchov's discharge

I. Fighting for power after Stalin's death. Khrushchov's victory Dissatisfaction with Stalin's regime From 1946 -1948 communist governments were imposed in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria and home-grown communist dictatorships rose to power in Yugoslavia and Albania. These nations became known as the "Communist Bloc". Stalin viewed Soviet consolidation of power in the region as a necessary step to protect the USSR by surrounding it with countries with friendly governments, to act as a buffer against possible invaders. n Finland retained formal independence, but was politically isolated and economically dependent on the Soviet Union. n Greece, Italy and France were under the strong influence of local communist parties, which were at the very least friendly towards Moscow. n After West Germany was formed by the union of the three Western occupation zones, the Soviets declared East Germany a separate country in 1949, ruled by the communists.

I. Fighting for power after Stalin's death. Khrushchov's victory Dissatisfaction with Stalin's regime From 1946 -1948 communist governments were imposed in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria and home-grown communist dictatorships rose to power in Yugoslavia and Albania. These nations became known as the "Communist Bloc". Stalin viewed Soviet consolidation of power in the region as a necessary step to protect the USSR by surrounding it with countries with friendly governments, to act as a buffer against possible invaders. n Finland retained formal independence, but was politically isolated and economically dependent on the Soviet Union. n Greece, Italy and France were under the strong influence of local communist parties, which were at the very least friendly towards Moscow. n After West Germany was formed by the union of the three Western occupation zones, the Soviets declared East Germany a separate country in 1949, ruled by the communists.

Dissatisfaction with Stalin's regime n In the post-war years the political self-consciousness of the people was gradually growing. Having passed all the ordeals, the people straitened up, and by came to understanding that it was not the Leader who played the decisive role in the historical process, but the people themselves. That development of the people's self-consciousness could not coexist with the Stalin’s regime. The Soviet society started to realise more and more clearly the necessity of reforms. n A part of the population expressed dissatisfaction with Stalin's policy. The situation was aggravated by the monetary reform of 1947 and by the abolition of ration cards. The reform gave a start to the development of commerce, many products and commodities appeared, but the majority of the population could not afford them. The thinking part of the Soviet society and first of all the intelligentsia' started to think over the problems of the society. Various people suggested carrying out most radical reforms. n The drafts of the new Program of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) which was supposed to be adopted by the end of 1947, had a provision for the competition of candidates in elections to the Soviets.

Dissatisfaction with Stalin's regime n In the post-war years the political self-consciousness of the people was gradually growing. Having passed all the ordeals, the people straitened up, and by came to understanding that it was not the Leader who played the decisive role in the historical process, but the people themselves. That development of the people's self-consciousness could not coexist with the Stalin’s regime. The Soviet society started to realise more and more clearly the necessity of reforms. n A part of the population expressed dissatisfaction with Stalin's policy. The situation was aggravated by the monetary reform of 1947 and by the abolition of ration cards. The reform gave a start to the development of commerce, many products and commodities appeared, but the majority of the population could not afford them. The thinking part of the Soviet society and first of all the intelligentsia' started to think over the problems of the society. Various people suggested carrying out most radical reforms. n The drafts of the new Program of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) which was supposed to be adopted by the end of 1947, had a provision for the competition of candidates in elections to the Soviets.

Countermeasures. New wave of repression n The committee in charge of the draft, which was headed by A. A. Zhdanov, rejected all those ideas. The administrative-commanding system, that is Stalin's regime, started protecting itself from the progressive people. n In the late 1940 s, repression started again. It did not reach the scale of the 1930 s, but still affected hundreds of thousands of people. n The first blow was directed against the intelligentsia. Severely criticised were writer M. Zoschenko, poet A. Akhmatova, composer D. Shostakovich, and others. They did not want to work under the methods of Soviet's realism. n 1948 - an well-known "Leningrad case" was started, in which such prominent figures as the chairman of the State Planning Committee (Gosplan) N. Voznesensky, the secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU A. Kuznetsov, the chairmen of the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) of the Russian Federation M. Rodionov, and some others were arrested and shot in secret

Countermeasures. New wave of repression n The committee in charge of the draft, which was headed by A. A. Zhdanov, rejected all those ideas. The administrative-commanding system, that is Stalin's regime, started protecting itself from the progressive people. n In the late 1940 s, repression started again. It did not reach the scale of the 1930 s, but still affected hundreds of thousands of people. n The first blow was directed against the intelligentsia. Severely criticised were writer M. Zoschenko, poet A. Akhmatova, composer D. Shostakovich, and others. They did not want to work under the methods of Soviet's realism. n 1948 - an well-known "Leningrad case" was started, in which such prominent figures as the chairman of the State Planning Committee (Gosplan) N. Voznesensky, the secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU A. Kuznetsov, the chairmen of the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) of the Russian Federation M. Rodionov, and some others were arrested and shot in secret

Anti-Semitic campaign n n 1948 -1953 -the anti-Semitic campaign against so-called "rootless cosmopolitans, " destruction of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, the fabrication of the "Doctors' plot, " the rise of "Zionology" and subsequent activities of official organizations such as the Anti. Zionist committee of the Soviet public were officially carried out under the banner of "anti. Zionism, " By the mid-1950 s the state persecution of Soviet Jews emerged as a major human rights issue in the West and domestically. 1948 - First Jews were arrested. Members of the Jewish Anti-fascist Committee were sentenced to death and subsequently shot. The campaign was held under the slogan of fighting the "cosmopolitanism without kith or kin". January 1953 - a group of Jewish doctors of the Kremlin hospital were condemned of assassinating the secretaries of the CPSU Central Committee Zhdanov and Scherbakov by means of improper medical treatment, and of preparing the assassination of Stalin. The doctors were said to work under the guidance of international Zionist organisation. A new campaign of mass repression was about to start, and only Stalin's death in March of 1953 stopped it.

Anti-Semitic campaign n n 1948 -1953 -the anti-Semitic campaign against so-called "rootless cosmopolitans, " destruction of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, the fabrication of the "Doctors' plot, " the rise of "Zionology" and subsequent activities of official organizations such as the Anti. Zionist committee of the Soviet public were officially carried out under the banner of "anti. Zionism, " By the mid-1950 s the state persecution of Soviet Jews emerged as a major human rights issue in the West and domestically. 1948 - First Jews were arrested. Members of the Jewish Anti-fascist Committee were sentenced to death and subsequently shot. The campaign was held under the slogan of fighting the "cosmopolitanism without kith or kin". January 1953 - a group of Jewish doctors of the Kremlin hospital were condemned of assassinating the secretaries of the CPSU Central Committee Zhdanov and Scherbakov by means of improper medical treatment, and of preparing the assassination of Stalin. The doctors were said to work under the guidance of international Zionist organisation. A new campaign of mass repression was about to start, and only Stalin's death in March of 1953 stopped it.

The starting point of the fight for power n Match 5, 1953 - Stalin's death. It unleashed a new struggle for succession to the leadership of the party and the country. Molotov had been widely thought to be Stalin's obvious successor but he had fallen into disfavour during Stalin's final years and had been removed from the Politburo in 1952 (though he was reinstated after Stalin's death). The struggle for succession became a contest between Beria (the feared leader of the NKVD), Malenkov and Khrushchev.

The starting point of the fight for power n Match 5, 1953 - Stalin's death. It unleashed a new struggle for succession to the leadership of the party and the country. Molotov had been widely thought to be Stalin's obvious successor but he had fallen into disfavour during Stalin's final years and had been removed from the Politburo in 1952 (though he was reinstated after Stalin's death). The struggle for succession became a contest between Beria (the feared leader of the NKVD), Malenkov and Khrushchev.

Beria's execution n July 1953 - the plenary session of Central Committee discussed the "Beria case". For a long time Beria headed the bodies of State Security and Internal Affairs and thus he was directly responsible for the repression. He was condemned of organising a plot to seize the power. L. Beria and six of his closest suppoters were shot. n After the execution of L. Beria Soviet people started to speak openly about the mass repression and the abuse of power. Mass rehabilitation of those condemned of political crimes was started.

Beria's execution n July 1953 - the plenary session of Central Committee discussed the "Beria case". For a long time Beria headed the bodies of State Security and Internal Affairs and thus he was directly responsible for the repression. He was condemned of organising a plot to seize the power. L. Beria and six of his closest suppoters were shot. n After the execution of L. Beria Soviet people started to speak openly about the mass repression and the abuse of power. Mass rehabilitation of those condemned of political crimes was started.

Lavrenty Beria (1899 - 1953)

Lavrenty Beria (1899 - 1953)

Khrushchev's personality n Khrushchev was regarded by his political enemies in the Soviet Union as uncivilized peasant, with a reputation for interrupting speakers to insult them. n He repeatedly disrupted a United Nations conference in September-October 1960 by pounding his fists on the table and shouting in Russian during speeches. On September 29, 1960, Khrushchev twice interrupted a speech by British prime minister Harold Macmillan by shouting out and pounding his desk. The unflappable Macmillan famously commented: "I should like that to be translated if he wants to say anything. “ n At another occasion, Khrushchev said in reference to capitalism, "We will bury you. " This phrase, ambiguous both in English and in Russian, was interpreted in several ways. He is famous for boasting to the U. S. President: "We will bury you. Our rockets could hit a fly over the United States. "

Khrushchev's personality n Khrushchev was regarded by his political enemies in the Soviet Union as uncivilized peasant, with a reputation for interrupting speakers to insult them. n He repeatedly disrupted a United Nations conference in September-October 1960 by pounding his fists on the table and shouting in Russian during speeches. On September 29, 1960, Khrushchev twice interrupted a speech by British prime minister Harold Macmillan by shouting out and pounding his desk. The unflappable Macmillan famously commented: "I should like that to be translated if he wants to say anything. “ n At another occasion, Khrushchev said in reference to capitalism, "We will bury you. " This phrase, ambiguous both in English and in Russian, was interpreted in several ways. He is famous for boasting to the U. S. President: "We will bury you. Our rockets could hit a fly over the United States. "

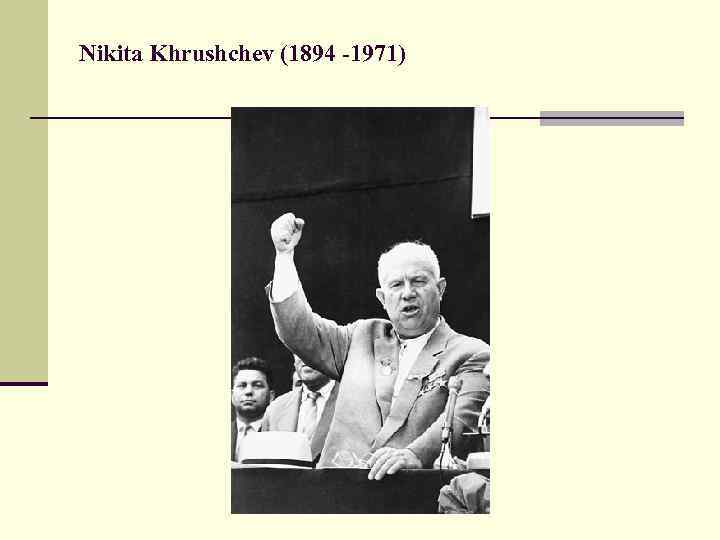

Nikita Khrushchev (1894 -1971)

Nikita Khrushchev (1894 -1971)

Beginning of the "Thaw" n April 1954 - the Supreme Court of the USSR considered again the "Leningrad case"; discharge of the people who had suffered from the political trials of the 1930 s was started. At that time there appeared the first timid attempts of criticising the "personality cult" in the media, but Stalin's name was not mentioned yet. That was the beginning of the socalled "thaw" period in Russian history. n The revision of the "Leningrad case" undermined the position G. Malenkov. February 1955 - he was relieved of the Chairman of the Council of Ministers. n As a result, N. S. Khruschov alone took the leading position. Under his leadership the process of rehabilitation grew faster.

Beginning of the "Thaw" n April 1954 - the Supreme Court of the USSR considered again the "Leningrad case"; discharge of the people who had suffered from the political trials of the 1930 s was started. At that time there appeared the first timid attempts of criticising the "personality cult" in the media, but Stalin's name was not mentioned yet. That was the beginning of the socalled "thaw" period in Russian history. n The revision of the "Leningrad case" undermined the position G. Malenkov. February 1955 - he was relieved of the Chairman of the Council of Ministers. n As a result, N. S. Khruschov alone took the leading position. Under his leadership the process of rehabilitation grew faster.

II. XX Congress of the CPSU - denouncement of Stalin's personality cult n The XX Congress of the CPSU was a turning point in the development of the Soviet society. n 1956 - Khrushchev pronounce at the XX Congress of the CPSU his report "Concerning the personality cult and its consequences”. n After the Congress, a special resolution of the CPSU Central Committee was passed ("Concerning the personality cult and its consequences"). It planed taking measures to reestablish Lenin's standards and the principle of collective leadership both in the communist party and in the state. n After long deliberations, in a month the speech was reported to the general public, but the full text was published only in 1989. n However the attempts made in the 1950 s to give a profound analysis of such a complex phenomenon as stalinism were not successful. Most studies were focused on the issue of personality and on criticising Stalin's personal characteristics. Stalin was declared to be personally responsible for all crimes and mistakes. Analysts at that time failed to realize that the personality cult is a complex political, moral, social and psychological issue.

II. XX Congress of the CPSU - denouncement of Stalin's personality cult n The XX Congress of the CPSU was a turning point in the development of the Soviet society. n 1956 - Khrushchev pronounce at the XX Congress of the CPSU his report "Concerning the personality cult and its consequences”. n After the Congress, a special resolution of the CPSU Central Committee was passed ("Concerning the personality cult and its consequences"). It planed taking measures to reestablish Lenin's standards and the principle of collective leadership both in the communist party and in the state. n After long deliberations, in a month the speech was reported to the general public, but the full text was published only in 1989. n However the attempts made in the 1950 s to give a profound analysis of such a complex phenomenon as stalinism were not successful. Most studies were focused on the issue of personality and on criticising Stalin's personal characteristics. Stalin was declared to be personally responsible for all crimes and mistakes. Analysts at that time failed to realize that the personality cult is a complex political, moral, social and psychological issue.

Nikita Khrushchev is delivering a speech on the Stalin's cult of personality at the 20 th Congress of the CPSU

Nikita Khrushchev is delivering a speech on the Stalin's cult of personality at the 20 th Congress of the CPSU

Internal party struggle n June 1957 - meeting of the Presidium of the CPSU Central Committee, Molotov and Malenkov unexpectedly raised the question of Khruschov 's dismissal. Khruschov was condemned of economical voluntarism, of illegal and ill-considered actions. Many of the reproaches were fair, but the main problem was that Khruschov had gone too far in revealing Stalin's deeds and that he had diminished the authority of the CPSU in the world communist movement. n The Presidium of CPSU Central Committee passed a resolution on Khruschov's dismissal from the post of the First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, but Khruschov refused to obey and demanded to summon a plenary meeting of the Central Committee. At the plenary meeting Khruschov was supported by the majority, while V. Molotov, G. Malenkov and L. Kaganovich were condemned of organising an "antiparty" group and dismissed from their posts. That put an end to the collective leadership, as Khruschov got unlimited power both in the party and in the state.

Internal party struggle n June 1957 - meeting of the Presidium of the CPSU Central Committee, Molotov and Malenkov unexpectedly raised the question of Khruschov 's dismissal. Khruschov was condemned of economical voluntarism, of illegal and ill-considered actions. Many of the reproaches were fair, but the main problem was that Khruschov had gone too far in revealing Stalin's deeds and that he had diminished the authority of the CPSU in the world communist movement. n The Presidium of CPSU Central Committee passed a resolution on Khruschov's dismissal from the post of the First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, but Khruschov refused to obey and demanded to summon a plenary meeting of the Central Committee. At the plenary meeting Khruschov was supported by the majority, while V. Molotov, G. Malenkov and L. Kaganovich were condemned of organising an "antiparty" group and dismissed from their posts. That put an end to the collective leadership, as Khruschov got unlimited power both in the party and in the state.

III. Khrushchov's political and economical reforms. Reasons of their failure Process of democratization n The XX Congress of the CPSU cleared the way for the processes of democratisation and renewal. The appraisals of the past which were made public, shocked people, especially shocking were the facts about the repressed and sunk into oblivion people. Changes in the public consciousness were under-way. n The democratisation process touched the political structure of the country. Lenin's standards and principles of the party life were reestablished. n Regular convocation of party congresses and plenary sessions of the Central Committee were provided. Party and state documents were published in the mass media and discussed by people. The activities of the Soviets, trade unions and the Komsomol stirred up. n New ideal and approaches were fruitful for the development of science, space, literature, and art.

III. Khrushchov's political and economical reforms. Reasons of their failure Process of democratization n The XX Congress of the CPSU cleared the way for the processes of democratisation and renewal. The appraisals of the past which were made public, shocked people, especially shocking were the facts about the repressed and sunk into oblivion people. Changes in the public consciousness were under-way. n The democratisation process touched the political structure of the country. Lenin's standards and principles of the party life were reestablished. n Regular convocation of party congresses and plenary sessions of the Central Committee were provided. Party and state documents were published in the mass media and discussed by people. The activities of the Soviets, trade unions and the Komsomol stirred up. n New ideal and approaches were fruitful for the development of science, space, literature, and art.

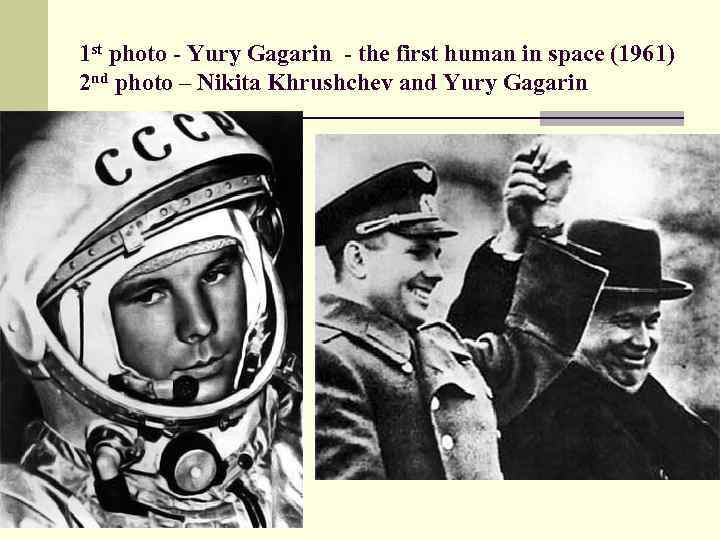

1 st photo - Yury Gagarin - the first human in space (1961) 2 nd photo – Nikita Khrushchev and Yury Gagarin

1 st photo - Yury Gagarin - the first human in space (1961) 2 nd photo – Nikita Khrushchev and Yury Gagarin

Foreign policy n Khrushchev liberated millions of political prisoners (the GULAG population declined from 13 million in 1953 to 5 million in 1956 -57) and initiating economic policies that emphasized commercial goods rather than coal and steel production, allowing living standards to rise dramatically and at the same time having high levels of economic growth. n Such loosening of controls also caused an enormous impact on its satellites in Central Europe, many of whom were resentful of Soviet influence in their affairs. n 1956 - Hungarian Revolution was suppressed by Soviet troops. About 25 -50, 000 Hungarian insurgents and 7, 000 Soviet troops were killed, thousands more were wounded, and nearly a quarter million left the country as refugees. The revolution was a blow to the Communists in Western countries; many who had formerly supported the Soviet Union now criticized it.

Foreign policy n Khrushchev liberated millions of political prisoners (the GULAG population declined from 13 million in 1953 to 5 million in 1956 -57) and initiating economic policies that emphasized commercial goods rather than coal and steel production, allowing living standards to rise dramatically and at the same time having high levels of economic growth. n Such loosening of controls also caused an enormous impact on its satellites in Central Europe, many of whom were resentful of Soviet influence in their affairs. n 1956 - Hungarian Revolution was suppressed by Soviet troops. About 25 -50, 000 Hungarian insurgents and 7, 000 Soviet troops were killed, thousands more were wounded, and nearly a quarter million left the country as refugees. The revolution was a blow to the Communists in Western countries; many who had formerly supported the Soviet Union now criticized it.

Economic reforms Late 1950 s and early 1960 s – economic reforms were designed to provide the democratization of management, i. e. to give more economical rights to the republics, to strengthen local management, to reduce the managing staff. n But many economical problems were approached with mere political methods. n The tasks of the development of virgin lands and the construction projects in Siberia were undertaken with the old well-known appeals to the enthusiasm and consciousness. The movement in favour of the "communist labour" was born at the peak of the enthusiasm. n All attempts of linking it with the economical interest were regarded as the restoration of capitalism in the economy.

Economic reforms Late 1950 s and early 1960 s – economic reforms were designed to provide the democratization of management, i. e. to give more economical rights to the republics, to strengthen local management, to reduce the managing staff. n But many economical problems were approached with mere political methods. n The tasks of the development of virgin lands and the construction projects in Siberia were undertaken with the old well-known appeals to the enthusiasm and consciousness. The movement in favour of the "communist labour" was born at the peak of the enthusiasm. n All attempts of linking it with the economical interest were regarded as the restoration of capitalism in the economy.

Administrative changes n Krushchev’s economic reforms were focused on decentralization and on strengthening the economical independence of enterprises. n February 1957 - the Plenary meeting of the CPSU Central Committee passed a resolution on the liquidation of Ministries and establishing Councils of National Economy (sovnarkhoz's) instead. n 1962 - Khrushchev's decision to divide party organizations into party committees in industry and agriculture n Sovnarkhoz, (Совнархоз, Совет Народного Хозяйства, Sovet Narodnogo Hozyaistva, "Council of National Economy"), usually translated as Regional Economic Council, is an organization of the Soviet Union to manage a separate economic region. They were subordinated to the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy.

Administrative changes n Krushchev’s economic reforms were focused on decentralization and on strengthening the economical independence of enterprises. n February 1957 - the Plenary meeting of the CPSU Central Committee passed a resolution on the liquidation of Ministries and establishing Councils of National Economy (sovnarkhoz's) instead. n 1962 - Khrushchev's decision to divide party organizations into party committees in industry and agriculture n Sovnarkhoz, (Совнархоз, Совет Народного Хозяйства, Sovet Narodnogo Hozyaistva, "Council of National Economy"), usually translated as Regional Economic Council, is an organization of the Soviet Union to manage a separate economic region. They were subordinated to the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy.

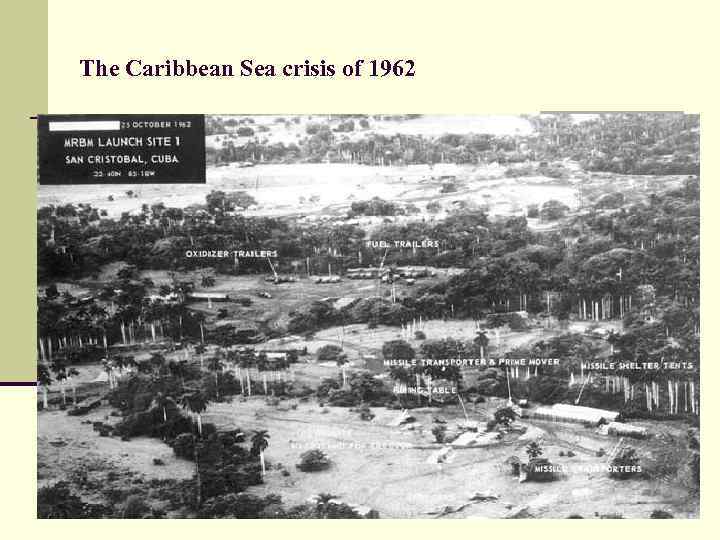

Results of the reforms n The first results of the 1957 reform were positive, but later it resulted in the dissociation of industries, and weakened the integral technical policy. n A great damage for the agriculture were the attempts to plant corn all around the country. n The reform of party bodies failed too (party bodies were divided into party committees which headed industry and agriculture) Industrial growth had slowed, while agriculture showed no new progress. n Abroad, the split with China, the construction of the Berlin Wall, and the Cuban crisis hurt the Soviet Union's international status. n In military policy Khrushchev pursued a policy of developing the Soviet Union's missile forces with a view to reducing the size of the armed forces.

Results of the reforms n The first results of the 1957 reform were positive, but later it resulted in the dissociation of industries, and weakened the integral technical policy. n A great damage for the agriculture were the attempts to plant corn all around the country. n The reform of party bodies failed too (party bodies were divided into party committees which headed industry and agriculture) Industrial growth had slowed, while agriculture showed no new progress. n Abroad, the split with China, the construction of the Berlin Wall, and the Cuban crisis hurt the Soviet Union's international status. n In military policy Khrushchev pursued a policy of developing the Soviet Union's missile forces with a view to reducing the size of the armed forces.

Assimilation of newly-ploughed virgin soil in the USSR

Assimilation of newly-ploughed virgin soil in the USSR

Nikita Khrushchev convinced to plant the corn in the USSR

Nikita Khrushchev convinced to plant the corn in the USSR

The Caribbean Sea crisis of 1962

The Caribbean Sea crisis of 1962

Fidel Alejandro Castro and Nikita Khrushchev

Fidel Alejandro Castro and Nikita Khrushchev

IV. Khrushchov's discharge Changes in social environment n The processes of democratisation found support among the working people. But people raised hard questions concerning not only the responsibility of Stalin, but also that of the whole political leadership. Thus Khruschov made himself and his colleagues an aim for criticism. n Minister of culture Furtseva confessed that the leadership was not ready to face the criticism.

IV. Khrushchov's discharge Changes in social environment n The processes of democratisation found support among the working people. But people raised hard questions concerning not only the responsibility of Stalin, but also that of the whole political leadership. Thus Khruschov made himself and his colleagues an aim for criticism. n Minister of culture Furtseva confessed that the leadership was not ready to face the criticism.

Slide back n Early 1960 s were marked by the deviation from the decisions of the XX n n Congress of CPSU. The attitude towards searching the "truth of life" in works of art began to change (criticism of Dudintsev's novel "Not by bread alone", persecution of B. Pasternak for the novel "Doctor Zhivago", the "bulldozer exhibitions", etc). The leadership of the country headed by Khruschov was not convinced that the processes of democratisation in the country are socialistic by nature. International factors were important, too. First of all, the events in Hungary in 1956 were taken into account. They were considered as counter-revolution against the leadership of the ruling party in Hungary, which finally resulted in the revolt of October - November. The Soviet leadership was very much concerned about possible repetition of the Hungarian revolt in the USSR. The events in Novocherkassk, where soldiers shot at striking workers, also concerned Khruschov.

Slide back n Early 1960 s were marked by the deviation from the decisions of the XX n n Congress of CPSU. The attitude towards searching the "truth of life" in works of art began to change (criticism of Dudintsev's novel "Not by bread alone", persecution of B. Pasternak for the novel "Doctor Zhivago", the "bulldozer exhibitions", etc). The leadership of the country headed by Khruschov was not convinced that the processes of democratisation in the country are socialistic by nature. International factors were important, too. First of all, the events in Hungary in 1956 were taken into account. They were considered as counter-revolution against the leadership of the ruling party in Hungary, which finally resulted in the revolt of October - November. The Soviet leadership was very much concerned about possible repetition of the Hungarian revolt in the USSR. The events in Novocherkassk, where soldiers shot at striking workers, also concerned Khruschov.

Anti-Khruschov’s opposition Early 1960 s were marked by the struggle between the democratic and the conservative trends in the social life. Who were the opponents of Khruschov's reforms? 1) Party and Soviet bodies; 2) Officers of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the KGB were dissatisfied the Khruschev’s policy. n 3) The attitude of the working people and of city dwellers became more and more negative (prices for meat and milk grew, State loans were not paid back, food supplies were not constant, the events in Novocherkassk where tanks were used against workers). 4) Agricultural problems became deeper. In early 1960 s country people opposed Khruschov's policy. 5) The "intelligentsia" shared common people's dissatisfaction with Khruschov too. The "thaw" of late 1950 s failed to become spring. Persecution of the intelligentsia grew in early 1960 -s.

Anti-Khruschov’s opposition Early 1960 s were marked by the struggle between the democratic and the conservative trends in the social life. Who were the opponents of Khruschov's reforms? 1) Party and Soviet bodies; 2) Officers of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the KGB were dissatisfied the Khruschev’s policy. n 3) The attitude of the working people and of city dwellers became more and more negative (prices for meat and milk grew, State loans were not paid back, food supplies were not constant, the events in Novocherkassk where tanks were used against workers). 4) Agricultural problems became deeper. In early 1960 s country people opposed Khruschov's policy. 5) The "intelligentsia" shared common people's dissatisfaction with Khruschov too. The "thaw" of late 1950 s failed to become spring. Persecution of the intelligentsia grew in early 1960 -s.

Khrushchev's fall n October 14, 1964 - Khrushchev's rivals in the party deposed him at a Central Committee meeting. The Communist Party subsequently accused Khrushschev of making political mistakes, such as provoking the 1962 Cuban crisis and disorganizing the Soviet economy, especially in the agricultural sector. n Following his removal from power, Khrushchev spent seven years under house arrest. He died at his home in Moscow on September 11, 1971 and is interred in the Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow, Russia.

Khrushchev's fall n October 14, 1964 - Khrushchev's rivals in the party deposed him at a Central Committee meeting. The Communist Party subsequently accused Khrushschev of making political mistakes, such as provoking the 1962 Cuban crisis and disorganizing the Soviet economy, especially in the agricultural sector. n Following his removal from power, Khrushchev spent seven years under house arrest. He died at his home in Moscow on September 11, 1971 and is interred in the Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow, Russia.

Literature to the topic 7: n n n n n n Ulam, A. B. Expansion and Coexistence: A History of Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917 -1967. -New York, 1968. Dallin, A. , and T. B. Larson, eds. Soviet Politics since Khrushchev. Englewood Cliffs, N. J. , 1968. Hammer, D. P. USSR: The Politics of Oligarchy. Hinsdale, Ill. , 1974. Leonard, W. The Kremlin since Stalin. New York, 1962. Schapiro, L. B. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union. New York, 1971. Swearer, H. R. , and M. Rush The Politics of Succession in the USSR: Materials on Khrushchev s Rise to Leadership. Boston, 1964. Breslauer, G. W. Khrushchev and Brezhnev as Leaders: Building Authority in Soviet Politics. London, 1982. Khrushchev, N. S. Khrushchev Remembers. Vol 1, edited and translated by S. Talbott. Introduction and Commentary by E. Crankshaw. Vol 2, The Last Testament. Mc. Neal, R. H. The Bolshevik Tradition: Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev. -Englewood Cliffs, N. J. , 1963. Mc. Neal, R. H. , ed. Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev: Voices of Bolshevism. -Englewood Cliffs, N. J. , 1963. Alec Nove. The Soviet economic system. Boston, Massachusetts; London; Sydney; Wellington: Unwin Hyman, 1986. 3 rd ed. 425 p. bibliog. Talbott S. Khrushchev Remembers. New York, 1974. Lazar Pistrak. The Grand Tactician: Khrushchev s Rise to Power. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. , 1961. Wolfgang Leonhard, trans. Elizabeth Wiskemann and Marian Jackson. The Kremlin Since Stalin. - New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. , 1962. Bertram D. Wolf. Khrushchev and Stalin s Ghost. - New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. , 1957. Zbigniew K. Brzezinski. The Soviet Bloc: Unity and Conflict. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960. Joseph S. Berliner. Soviet Economic Aid. - New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. , 1958. John N. Hazard. The Soviet system of government. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press, 1980. 5 th rev. ed. 330 p. bibliog. Seweryn Bialer. Stalin s successors: leadership, stability and change in the Soviet Union. Cambridge, England; London; New York; New Rochelle, New York; Melbourne; Sydney: Cambridge University Press, 1980. 312 p. Heller, M. and Nekrich, A. Utopia in Power: A History of the USSR from 1917 to the Present. London, Hutchinson, 1986. Agursky, Mikhail. The Third Rome: National Bolshevism in the USSR. Boulder and London, Westview Press, 1987. Azrael, Jeremy (ed. ). Soviet Nationality Policies and Practices. New York, Praeger, 1978. Isaac Deutscher. The unfinished revolution: Russia 1917 -1967. London, New York: Oxford University Press, 1967. viii+115 p. (George Macaulay Lectures, Cambridge, 1967).

Literature to the topic 7: n n n n n n Ulam, A. B. Expansion and Coexistence: A History of Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917 -1967. -New York, 1968. Dallin, A. , and T. B. Larson, eds. Soviet Politics since Khrushchev. Englewood Cliffs, N. J. , 1968. Hammer, D. P. USSR: The Politics of Oligarchy. Hinsdale, Ill. , 1974. Leonard, W. The Kremlin since Stalin. New York, 1962. Schapiro, L. B. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union. New York, 1971. Swearer, H. R. , and M. Rush The Politics of Succession in the USSR: Materials on Khrushchev s Rise to Leadership. Boston, 1964. Breslauer, G. W. Khrushchev and Brezhnev as Leaders: Building Authority in Soviet Politics. London, 1982. Khrushchev, N. S. Khrushchev Remembers. Vol 1, edited and translated by S. Talbott. Introduction and Commentary by E. Crankshaw. Vol 2, The Last Testament. Mc. Neal, R. H. The Bolshevik Tradition: Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev. -Englewood Cliffs, N. J. , 1963. Mc. Neal, R. H. , ed. Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev: Voices of Bolshevism. -Englewood Cliffs, N. J. , 1963. Alec Nove. The Soviet economic system. Boston, Massachusetts; London; Sydney; Wellington: Unwin Hyman, 1986. 3 rd ed. 425 p. bibliog. Talbott S. Khrushchev Remembers. New York, 1974. Lazar Pistrak. The Grand Tactician: Khrushchev s Rise to Power. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. , 1961. Wolfgang Leonhard, trans. Elizabeth Wiskemann and Marian Jackson. The Kremlin Since Stalin. - New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. , 1962. Bertram D. Wolf. Khrushchev and Stalin s Ghost. - New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. , 1957. Zbigniew K. Brzezinski. The Soviet Bloc: Unity and Conflict. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960. Joseph S. Berliner. Soviet Economic Aid. - New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. , 1958. John N. Hazard. The Soviet system of government. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press, 1980. 5 th rev. ed. 330 p. bibliog. Seweryn Bialer. Stalin s successors: leadership, stability and change in the Soviet Union. Cambridge, England; London; New York; New Rochelle, New York; Melbourne; Sydney: Cambridge University Press, 1980. 312 p. Heller, M. and Nekrich, A. Utopia in Power: A History of the USSR from 1917 to the Present. London, Hutchinson, 1986. Agursky, Mikhail. The Third Rome: National Bolshevism in the USSR. Boulder and London, Westview Press, 1987. Azrael, Jeremy (ed. ). Soviet Nationality Policies and Practices. New York, Praeger, 1978. Isaac Deutscher. The unfinished revolution: Russia 1917 -1967. London, New York: Oxford University Press, 1967. viii+115 p. (George Macaulay Lectures, Cambridge, 1967).

Literature to the topic 7: n n n n n n n Sally Pickering. Twentieth-century Russia. London, New York: Oxford University Press, 1965. Reprinted with corrections, 1972. 80 p. maps. (The Changing World). Donald W. Treadgold. Twentieth-century Russia. Chicago, Illinois: Rand Mc. Nally, 1971. 3 rd ed. 563 p. Alexander Werth. Russia: hopes and fears. London: Barrie & Rockliff: The Cresset Press, 1969. 391 p. J. N. Westwood. Russia, 1917 -1964. London: Batsford, 1966. 208 p. 2 maps. Aleksandrov A. History of Soviet foreign policy: 1945 -1970. Moscow, 1974. Lateber Walter. America, Russia and the Cold War 1945 -1966. New York, 1967. Laird Robbin. Soviet foreign policy. New York, 1987. Hearst William Randolph. Khrushchev and the Russian challenge. New York, 1961. Pistrak Lazar. The grand taetician: Khrushchev s rise to power. London, 1961. Mc. Neal Robert. The Bolshevik tradition: Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev. Englewood Cliffs, N. J. , 1963. Medvedev Roj Aleksandrovic. Khrushchev: the years in power. London, 1977. Medvedev Roj Aleksandrovic. Nikita Chruscew. Höganäs: Viken, 1984. Cohen Stephen. The Soviet Union since Stalin. Bloomington, 1980. Zubok Vladislav Martinovic. Inside the Kremlin s cold war: from Stalin to Khrushchev. Cambridge, 1996. Schapiro Leonard. The Communist party of the Soviet Union. New York, 1960. Lelcuk V. A short history of Soviet society. Moscow, 1971. Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. History of Russia. New York: Oxford Univ. P. , 1993. Mc. Auley, Mary. Soviet politics 1917 -1991. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1992. Treadgold, Donald W. Twentieth century Russia. Chicago: Rand Mc. Nally, 1964. Schapiro, Leonard. The Communist party of the Soviet Union. New York, 1960. Ponomarev, Boris Nikolaevic. A short history of the Communist party of the Soviet Union. Moscow, 1970. Roy Medvedev, translated by Brian Pearce. Khrushchev. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1982. 292 p. Roy A. Medvedev, Zhores A. Medvedev, translated from the Russian by Andrew R. Durkin. Khrushchev: the years in power. New York, London: Cjlumbia University Press, Oxford University Press, 1975, 1977. 198 p. map. Edited by Martin Mc. Cauley. Khrushchev and Khrushchevism. Basingstoke, England; London: Macmillan in association with the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University of London, 1987. 243 p. bibliog. Edited by R. F. Miller, F. Féhér. Khrushchev and the communist world. London; Canberra: Totowa, New Jersey: Croom Helm, Barnes & Noble, 1984. 243 p.

Literature to the topic 7: n n n n n n n Sally Pickering. Twentieth-century Russia. London, New York: Oxford University Press, 1965. Reprinted with corrections, 1972. 80 p. maps. (The Changing World). Donald W. Treadgold. Twentieth-century Russia. Chicago, Illinois: Rand Mc. Nally, 1971. 3 rd ed. 563 p. Alexander Werth. Russia: hopes and fears. London: Barrie & Rockliff: The Cresset Press, 1969. 391 p. J. N. Westwood. Russia, 1917 -1964. London: Batsford, 1966. 208 p. 2 maps. Aleksandrov A. History of Soviet foreign policy: 1945 -1970. Moscow, 1974. Lateber Walter. America, Russia and the Cold War 1945 -1966. New York, 1967. Laird Robbin. Soviet foreign policy. New York, 1987. Hearst William Randolph. Khrushchev and the Russian challenge. New York, 1961. Pistrak Lazar. The grand taetician: Khrushchev s rise to power. London, 1961. Mc. Neal Robert. The Bolshevik tradition: Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev. Englewood Cliffs, N. J. , 1963. Medvedev Roj Aleksandrovic. Khrushchev: the years in power. London, 1977. Medvedev Roj Aleksandrovic. Nikita Chruscew. Höganäs: Viken, 1984. Cohen Stephen. The Soviet Union since Stalin. Bloomington, 1980. Zubok Vladislav Martinovic. Inside the Kremlin s cold war: from Stalin to Khrushchev. Cambridge, 1996. Schapiro Leonard. The Communist party of the Soviet Union. New York, 1960. Lelcuk V. A short history of Soviet society. Moscow, 1971. Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. History of Russia. New York: Oxford Univ. P. , 1993. Mc. Auley, Mary. Soviet politics 1917 -1991. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1992. Treadgold, Donald W. Twentieth century Russia. Chicago: Rand Mc. Nally, 1964. Schapiro, Leonard. The Communist party of the Soviet Union. New York, 1960. Ponomarev, Boris Nikolaevic. A short history of the Communist party of the Soviet Union. Moscow, 1970. Roy Medvedev, translated by Brian Pearce. Khrushchev. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1982. 292 p. Roy A. Medvedev, Zhores A. Medvedev, translated from the Russian by Andrew R. Durkin. Khrushchev: the years in power. New York, London: Cjlumbia University Press, Oxford University Press, 1975, 1977. 198 p. map. Edited by Martin Mc. Cauley. Khrushchev and Khrushchevism. Basingstoke, England; London: Macmillan in association with the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University of London, 1987. 243 p. bibliog. Edited by R. F. Miller, F. Féhér. Khrushchev and the communist world. London; Canberra: Totowa, New Jersey: Croom Helm, Barnes & Noble, 1984. 243 p.

Literature to the topic 7: n n n n n Edited by R. F. Miller, F. Féhér. Khrushchev and the communist world. London; Canberra: Totowa, New Jersey: Croom Helm, Barnes & Noble, 1984. 243 p. Sergei Khrushchev, edited and translated from the Russian by William Taubman. Khrushchev on Khrushchev: an inside account of the man and his era. Boston, Massachusetts; Toronto; London: Little, Brown, 1990. 423 p. Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, with an introduction, commentary and notes by Edward Crankshaw, translated from the Russian and edited by Strobe Talbott. Khrushchev remembers. Boston, Massachusetts; Toronto: Little, Brown, 1970. 639 p. Foreword by Strobe Talbott, translated from the Russian and edited by Jerrold L. Schecter, Vyacheslav V. Luchkov. Khrushchev remembers: the glasnost tapes. Boston, Massachusetts: Toronto; London: Little, Brown, 1990. 219 p. 4 maps. Translated from the Russian and edited by Strobe Talbott, with a foreword by Edward Crankshaw and an introduction by Jerrold L. Schecter. Khrushchev remembers: the last testament. London: André Deutsch, Little, Brown, 1974. 602 p. Martin Mc. Cauley. Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev. London: Cardinal, 1991. 144 p. map. bibliog. (makers of the Twentieth Century). Edward Crankshaw. Khrushchev: a biography. _London: Collins, 1966. 316 p. Edward Crankshaw. Khrushchev s Russia. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1959. 175 p. (Penguin Special). Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, with an introduction and commentary and notes by Edward Crankshaw, translated and edited by Strobe Talbott. Khrushchev remembers (Part 1: From the coal mines to the Kremlin. Part 2: The world outside). London: Deutsch, 1971. xxviii+639 p. Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, translated and edited by Strobe Talbott, foreword by Edward Crankshaw, introduction by Jerrold L. Schecter. Khrushchev remembers: the last testament (Part 1: Citizens and comrades; Part 2: Foreign policy and travels). London: Deutsch, 1974. xxxi+603 p. Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, edited with commentary by Thomas P. Whitney. Khrushchev speaks: selected speeches, articles and press conferences, 1949 -1961. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1963. 466 p. Roy A. Medvedev, Zhores A. Medvedev, translated by Andrew R. Durkin. Khrushchev: the years in power. -New York: Columbia University Press, 1976; London: Oxford University Press, 1977. xi+198 p. Roger William Pethybridge. A history of postwar Russsia. London: Allen & Unwin, 1966. 263 p. (Minerva Series of Students Handbooks, no. 14). Alexander Werth. The Khrushchev phase: the Soviet Union enters the decisive sixties. London: Robert Hale, 1961. 284 p. Merle Fainsod. How Russia is ruled. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1964. 2 nd ed. 684 p. (Russian Research Center Studies, no. 11). John N. Hazard. The Soviet system of government. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1964. 3 rd revised ed. 282 p. Communist Party of the Soviet Union, compiled by B. N. Ponomaryov (et al. ). History of the Communist Party of the Sovien Union. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1960. 765 p.

Literature to the topic 7: n n n n n Edited by R. F. Miller, F. Féhér. Khrushchev and the communist world. London; Canberra: Totowa, New Jersey: Croom Helm, Barnes & Noble, 1984. 243 p. Sergei Khrushchev, edited and translated from the Russian by William Taubman. Khrushchev on Khrushchev: an inside account of the man and his era. Boston, Massachusetts; Toronto; London: Little, Brown, 1990. 423 p. Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, with an introduction, commentary and notes by Edward Crankshaw, translated from the Russian and edited by Strobe Talbott. Khrushchev remembers. Boston, Massachusetts; Toronto: Little, Brown, 1970. 639 p. Foreword by Strobe Talbott, translated from the Russian and edited by Jerrold L. Schecter, Vyacheslav V. Luchkov. Khrushchev remembers: the glasnost tapes. Boston, Massachusetts: Toronto; London: Little, Brown, 1990. 219 p. 4 maps. Translated from the Russian and edited by Strobe Talbott, with a foreword by Edward Crankshaw and an introduction by Jerrold L. Schecter. Khrushchev remembers: the last testament. London: André Deutsch, Little, Brown, 1974. 602 p. Martin Mc. Cauley. Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev. London: Cardinal, 1991. 144 p. map. bibliog. (makers of the Twentieth Century). Edward Crankshaw. Khrushchev: a biography. _London: Collins, 1966. 316 p. Edward Crankshaw. Khrushchev s Russia. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1959. 175 p. (Penguin Special). Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, with an introduction and commentary and notes by Edward Crankshaw, translated and edited by Strobe Talbott. Khrushchev remembers (Part 1: From the coal mines to the Kremlin. Part 2: The world outside). London: Deutsch, 1971. xxviii+639 p. Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, translated and edited by Strobe Talbott, foreword by Edward Crankshaw, introduction by Jerrold L. Schecter. Khrushchev remembers: the last testament (Part 1: Citizens and comrades; Part 2: Foreign policy and travels). London: Deutsch, 1974. xxxi+603 p. Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, edited with commentary by Thomas P. Whitney. Khrushchev speaks: selected speeches, articles and press conferences, 1949 -1961. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1963. 466 p. Roy A. Medvedev, Zhores A. Medvedev, translated by Andrew R. Durkin. Khrushchev: the years in power. -New York: Columbia University Press, 1976; London: Oxford University Press, 1977. xi+198 p. Roger William Pethybridge. A history of postwar Russsia. London: Allen & Unwin, 1966. 263 p. (Minerva Series of Students Handbooks, no. 14). Alexander Werth. The Khrushchev phase: the Soviet Union enters the decisive sixties. London: Robert Hale, 1961. 284 p. Merle Fainsod. How Russia is ruled. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1964. 2 nd ed. 684 p. (Russian Research Center Studies, no. 11). John N. Hazard. The Soviet system of government. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1964. 3 rd revised ed. 282 p. Communist Party of the Soviet Union, compiled by B. N. Ponomaryov (et al. ). History of the Communist Party of the Sovien Union. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1960. 765 p.