20c3b715d39698e631a9077988855a69.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 165

LECTURE 8: Coalitions, Voting Power, and Computational Social Choice An Introduction to Multi. Agent Systems http: //www. csc. liv. ac. uk/~mjw/pubs/imas (Thanks to Georgios Chalkiadakis, Edith Elkind, and Michael Wooldridge, for making available slides from their AAMAS’ 11 tutorial on “Cooperative Games in MAS”) 7 -1

LECTURE 8: Coalitions, Voting Power, and Computational Social Choice An Introduction to Multi. Agent Systems http: //www. csc. liv. ac. uk/~mjw/pubs/imas (Thanks to Georgios Chalkiadakis, Edith Elkind, and Michael Wooldridge, for making available slides from their AAMAS’ 11 tutorial on “Cooperative Games in MAS”) 7 -1

Game Theory in MAS n n Multi-agent systems research area studies interactions between self-interested computational entities Game theory: a branch of economics that deals with decision-making in environments full of self-interested entities Game theory proposes solution concepts, defining rational outcomes However, solution concepts may be hard to compute. . .

Game Theory in MAS n n Multi-agent systems research area studies interactions between self-interested computational entities Game theory: a branch of economics that deals with decision-making in environments full of self-interested entities Game theory proposes solution concepts, defining rational outcomes However, solution concepts may be hard to compute. . .

A Point of Reference: Non-Cooperative Games n n n A non-cooperative game is defined by q a set of agents (players) N = {1, . . , n} q for each agent i N, a set of actions Si q for each agent i N, a utility function ui , ui: S 1 x. . x Sn → R An agent’s utility depends not just on her action, but on actions of other agents; thus, for i finding the best action involves deliberating about what other will do Classic example: Prisoners’ Dilemma

A Point of Reference: Non-Cooperative Games n n n A non-cooperative game is defined by q a set of agents (players) N = {1, . . , n} q for each agent i N, a set of actions Si q for each agent i N, a utility function ui , ui: S 1 x. . x Sn → R An agent’s utility depends not just on her action, but on actions of other agents; thus, for i finding the best action involves deliberating about what other will do Classic example: Prisoners’ Dilemma

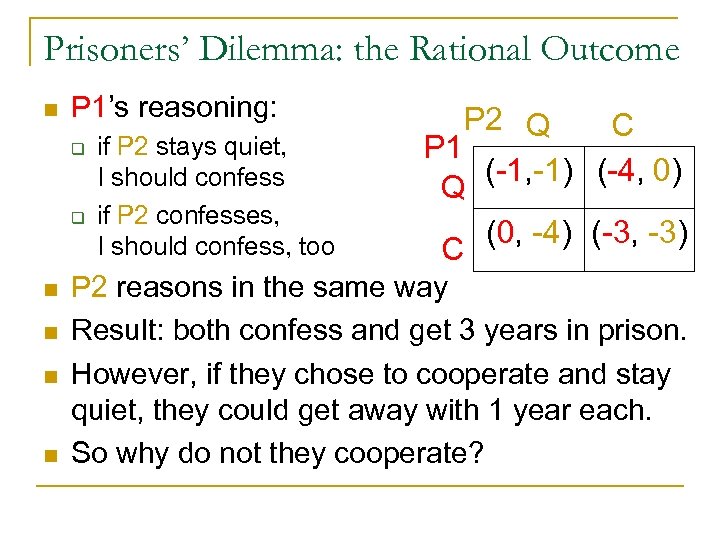

Prisoners’ Dilemma: the Rational Outcome n P 1’s reasoning: q q n n if P 2 stays quiet, I should confess if P 2 confesses, I should confess, too P 2 Q C P 1 (-1, -1) (-4, 0) Q (0, -4) (-3, -3) C P 2 reasons in the same way Result: both confess and get 3 years in prison. However, if they chose to cooperate and stay quiet, they could get away with 1 year each. So why do not they cooperate?

Prisoners’ Dilemma: the Rational Outcome n P 1’s reasoning: q q n n if P 2 stays quiet, I should confess if P 2 confesses, I should confess, too P 2 Q C P 1 (-1, -1) (-4, 0) Q (0, -4) (-3, -3) C P 2 reasons in the same way Result: both confess and get 3 years in prison. However, if they chose to cooperate and stay quiet, they could get away with 1 year each. So why do not they cooperate?

Assumptions in Non-Cooperative Games n n n Cooperation does not occur in prisoners’ dilemma, because players cannot make binding agreements But what if binding agreements are possible? This is exactly the class of scenarios studied by cooperative game theory

Assumptions in Non-Cooperative Games n n n Cooperation does not occur in prisoners’ dilemma, because players cannot make binding agreements But what if binding agreements are possible? This is exactly the class of scenarios studied by cooperative game theory

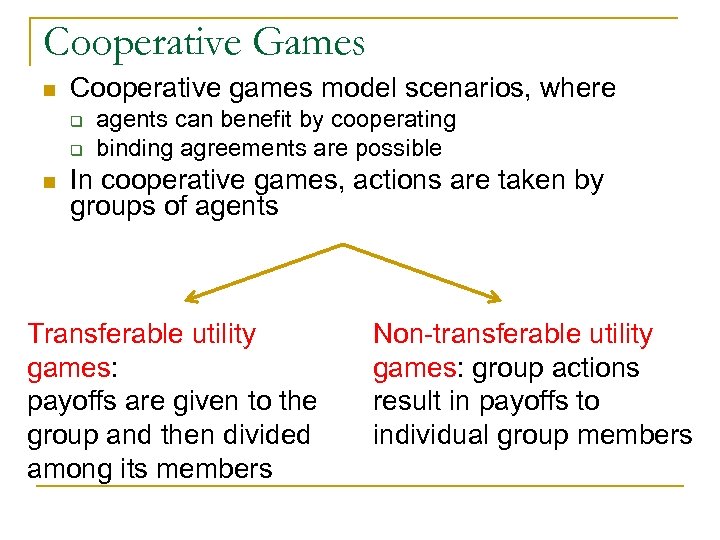

Cooperative Games n Cooperative games model scenarios, where q q n agents can benefit by cooperating binding agreements are possible In cooperative games, actions are taken by groups of agents Transferable utility games: payoffs are given to the group and then divided among its members Non-transferable utility games: group actions result in payoffs to individual group members

Cooperative Games n Cooperative games model scenarios, where q q n agents can benefit by cooperating binding agreements are possible In cooperative games, actions are taken by groups of agents Transferable utility games: payoffs are given to the group and then divided among its members Non-transferable utility games: group actions result in payoffs to individual group members

Phases of Coalitional Action n n Agents form coalitions (teams) Each coalition chooses its action Non-transferable utility (NTU) games: the choice of coalitional actions (by all coalitions) determines each player’s payoffs Transferable utility (TU) games: the choice of coalitional actions (by all coalitions) determines the payoff of each coalition q the members of the coalition then need to divide this joint payoff

Phases of Coalitional Action n n Agents form coalitions (teams) Each coalition chooses its action Non-transferable utility (NTU) games: the choice of coalitional actions (by all coalitions) determines each player’s payoffs Transferable utility (TU) games: the choice of coalitional actions (by all coalitions) determines the payoff of each coalition q the members of the coalition then need to divide this joint payoff

Non-Transferable Utility Games: Writing Papers n n researchers working at n different universities can form groups to write papers on game theory each group of researchers can work together; the composition of a group determines the quality of the paper they produce each author receives a payoff from his own university q q q n promotion bonus teaching load reduction Payoffs are non-transferable

Non-Transferable Utility Games: Writing Papers n n researchers working at n different universities can form groups to write papers on game theory each group of researchers can work together; the composition of a group determines the quality of the paper they produce each author receives a payoff from his own university q q q n promotion bonus teaching load reduction Payoffs are non-transferable

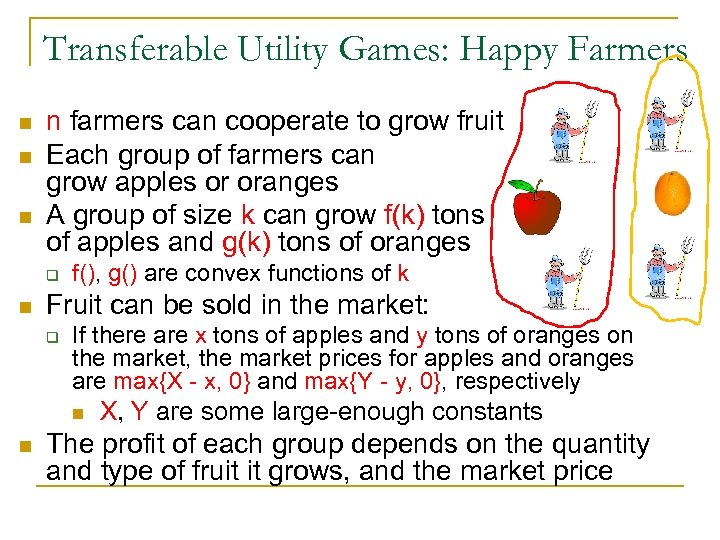

Transferable Utility Games: Happy Farmers n n farmers can cooperate to grow fruit Each group of farmers can grow apples or oranges A group of size k can grow f(k) tons of apples and g(k) tons of oranges q n f(), g() are convex functions of k Fruit can be sold in the market: q If there are x tons of apples and y tons of oranges on the market, the market prices for apples and oranges are max{X - x, 0} and max{Y - y, 0}, respectively n n X, Y are some large-enough constants The profit of each group depends on the quantity and type of fruit it grows, and the market price

Transferable Utility Games: Happy Farmers n n farmers can cooperate to grow fruit Each group of farmers can grow apples or oranges A group of size k can grow f(k) tons of apples and g(k) tons of oranges q n f(), g() are convex functions of k Fruit can be sold in the market: q If there are x tons of apples and y tons of oranges on the market, the market prices for apples and oranges are max{X - x, 0} and max{Y - y, 0}, respectively n n X, Y are some large-enough constants The profit of each group depends on the quantity and type of fruit it grows, and the market price

Transferable Utility Games: Buying Ice-Cream n n children, each has some amount of money q n Three types of ice-cream tubs are for sale: q q q n n n the i-th child has bi dollars Type 1 costs $7, contains 500 g Type 2 costs $9, contains 750 g Type 3 costs $11, contains 1 kg Children have utility for ice-cream, and do not care about money The payoff of each group: the maximum quantity of ice-cream the members of the group can buy by pooling their money The ice-cream can be shared arbitrarily within the group

Transferable Utility Games: Buying Ice-Cream n n children, each has some amount of money q n Three types of ice-cream tubs are for sale: q q q n n n the i-th child has bi dollars Type 1 costs $7, contains 500 g Type 2 costs $9, contains 750 g Type 3 costs $11, contains 1 kg Children have utility for ice-cream, and do not care about money The payoff of each group: the maximum quantity of ice-cream the members of the group can buy by pooling their money The ice-cream can be shared arbitrarily within the group

Characteristic Function Games vs. Partition Function Games n n In general TU games, the payoff obtained by a coalition depends on the actions chosen by other coalitions; these games are also known as partition function games (PFG) Characteristic function games (CFG): the payoff of each coalition only depends on the action of that coalition q q q in such games, each coalition can be identified with the profit it obtains by choosing its best action Ice Cream game is a CFG Happy Farmers game is a PFG, but not a CFG

Characteristic Function Games vs. Partition Function Games n n In general TU games, the payoff obtained by a coalition depends on the actions chosen by other coalitions; these games are also known as partition function games (PFG) Characteristic function games (CFG): the payoff of each coalition only depends on the action of that coalition q q q in such games, each coalition can be identified with the profit it obtains by choosing its best action Ice Cream game is a CFG Happy Farmers game is a PFG, but not a CFG

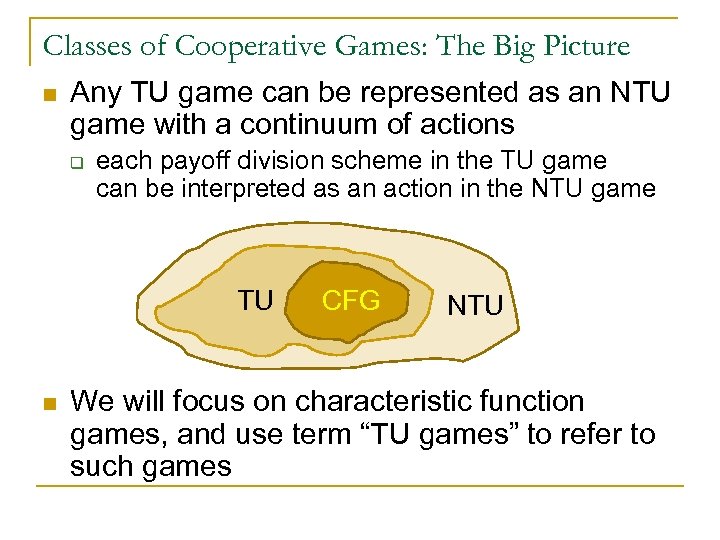

Classes of Cooperative Games: The Big Picture n Any TU game can be represented as an NTU game with a continuum of actions q each payoff division scheme in the TU game can be interpreted as an action in the NTU game TU n CFG NTU We will focus on characteristic function games, and use term “TU games” to refer to such games

Classes of Cooperative Games: The Big Picture n Any TU game can be represented as an NTU game with a continuum of actions q each payoff division scheme in the TU game can be interpreted as an action in the NTU game TU n CFG NTU We will focus on characteristic function games, and use term “TU games” to refer to such games

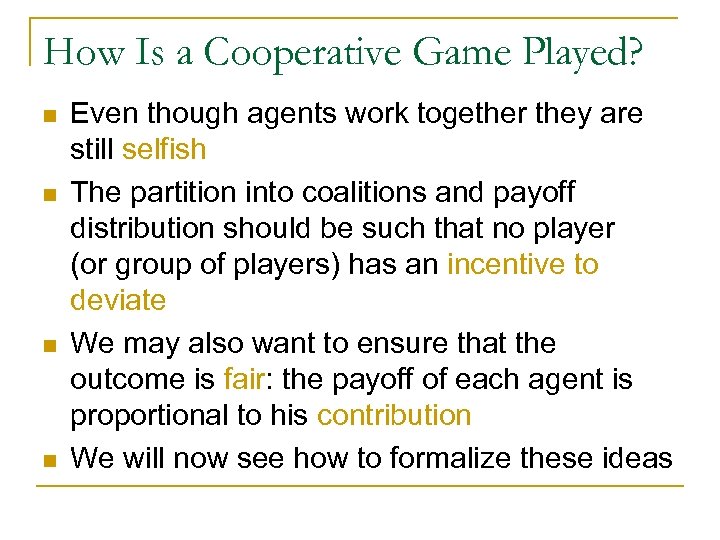

How Is a Cooperative Game Played? n n Even though agents work together they are still selfish The partition into coalitions and payoff distribution should be such that no player (or group of players) has an incentive to deviate We may also want to ensure that the outcome is fair: the payoff of each agent is proportional to his contribution We will now see how to formalize these ideas

How Is a Cooperative Game Played? n n Even though agents work together they are still selfish The partition into coalitions and payoff distribution should be such that no player (or group of players) has an incentive to deviate We may also want to ensure that the outcome is fair: the payoff of each agent is proportional to his contribution We will now see how to formalize these ideas

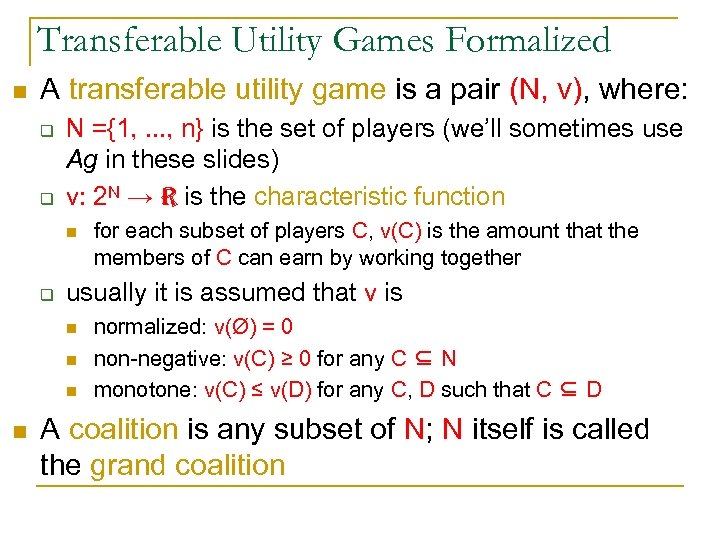

Transferable Utility Games Formalized n A transferable utility game is a pair (N, v), where: q q N ={1, . . . , n} is the set of players (we’ll sometimes use Ag in these slides) v: 2 N → R is the characteristic function n q usually it is assumed that v is n n for each subset of players C, v(C) is the amount that the members of C can earn by working together normalized: v(Ø) = 0 non-negative: v(C) ≥ 0 for any C ⊆ N monotone: v(C) ≤ v(D) for any C, D such that C ⊆ D A coalition is any subset of N; N itself is called the grand coalition

Transferable Utility Games Formalized n A transferable utility game is a pair (N, v), where: q q N ={1, . . . , n} is the set of players (we’ll sometimes use Ag in these slides) v: 2 N → R is the characteristic function n q usually it is assumed that v is n n for each subset of players C, v(C) is the amount that the members of C can earn by working together normalized: v(Ø) = 0 non-negative: v(C) ≥ 0 for any C ⊆ N monotone: v(C) ≤ v(D) for any C, D such that C ⊆ D A coalition is any subset of N; N itself is called the grand coalition

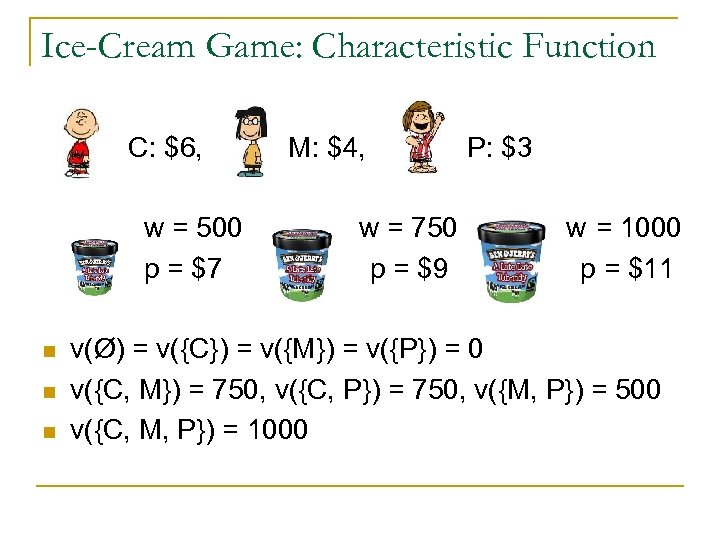

Ice-Cream Game: Characteristic Function C: $6, w = 500 p = $7 n n n M: $4, w = 750 p = $9 P: $3 w = 1000 p = $11 v(Ø) = v({C}) = v({M}) = v({P}) = 0 v({C, M}) = 750, v({C, P}) = 750, v({M, P}) = 500 v({C, M, P}) = 1000

Ice-Cream Game: Characteristic Function C: $6, w = 500 p = $7 n n n M: $4, w = 750 p = $9 P: $3 w = 1000 p = $11 v(Ø) = v({C}) = v({M}) = v({P}) = 0 v({C, M}) = 750, v({C, P}) = 750, v({M, P}) = 500 v({C, M, P}) = 1000

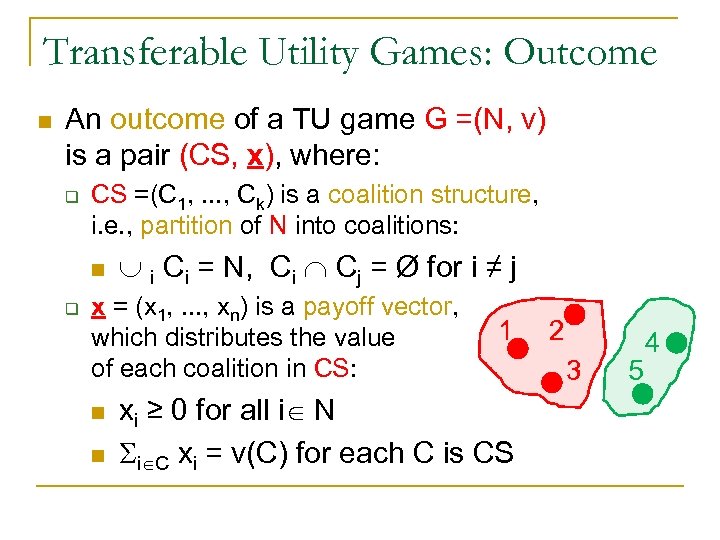

Transferable Utility Games: Outcome n An outcome of a TU game G =(N, v) is a pair (CS, x), where: q CS =(C 1, . . . , Ck) is a coalition structure, i. e. , partition of N into coalitions: n q i Ci = N, Ci Cj = Ø for i ≠ j x = (x 1, . . . , xn) is a payoff vector, which distributes the value of each coalition in CS: n n 1 xi ≥ 0 for all i N Si C xi = v(C) for each C is CS 2 3 5 4

Transferable Utility Games: Outcome n An outcome of a TU game G =(N, v) is a pair (CS, x), where: q CS =(C 1, . . . , Ck) is a coalition structure, i. e. , partition of N into coalitions: n q i Ci = N, Ci Cj = Ø for i ≠ j x = (x 1, . . . , xn) is a payoff vector, which distributes the value of each coalition in CS: n n 1 xi ≥ 0 for all i N Si C xi = v(C) for each C is CS 2 3 5 4

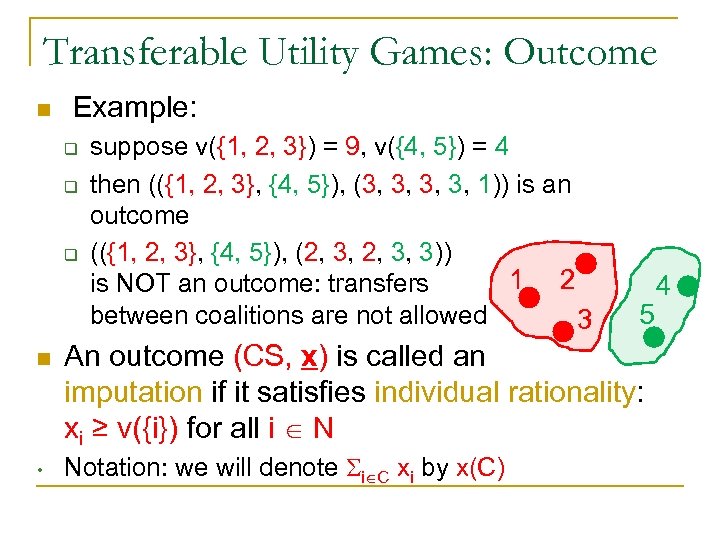

Transferable Utility Games: Outcome n Example: q q q n • suppose v({1, 2, 3}) = 9, v({4, 5}) = 4 then (({1, 2, 3}, {4, 5}), (3, 3, 1)) is an outcome (({1, 2, 3}, {4, 5}), (2, 3, 3)) 1 2 is NOT an outcome: transfers between coalitions are not allowed 3 5 An outcome (CS, x) is called an imputation if it satisfies individual rationality: xi ≥ v({i}) for all i N Notation: we will denote Si C xi by x(C) 4

Transferable Utility Games: Outcome n Example: q q q n • suppose v({1, 2, 3}) = 9, v({4, 5}) = 4 then (({1, 2, 3}, {4, 5}), (3, 3, 1)) is an outcome (({1, 2, 3}, {4, 5}), (2, 3, 3)) 1 2 is NOT an outcome: transfers between coalitions are not allowed 3 5 An outcome (CS, x) is called an imputation if it satisfies individual rationality: xi ≥ v({i}) for all i N Notation: we will denote Si C xi by x(C) 4

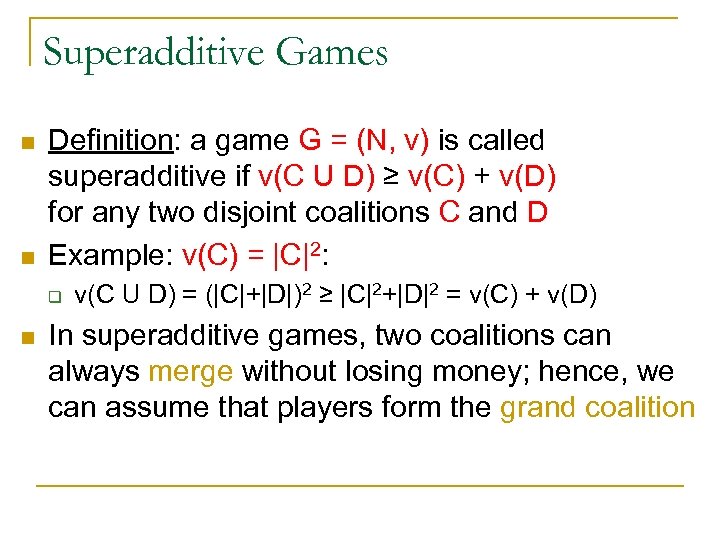

Superadditive Games n n Definition: a game G = (N, v) is called superadditive if v(C U D) ≥ v(C) + v(D) for any two disjoint coalitions C and D Example: v(C) = |C|2: q n v(C U D) = (|C|+|D|)2 ≥ |C|2+|D|2 = v(C) + v(D) In superadditive games, two coalitions can always merge without losing money; hence, we can assume that players form the grand coalition

Superadditive Games n n Definition: a game G = (N, v) is called superadditive if v(C U D) ≥ v(C) + v(D) for any two disjoint coalitions C and D Example: v(C) = |C|2: q n v(C U D) = (|C|+|D|)2 ≥ |C|2+|D|2 = v(C) + v(D) In superadditive games, two coalitions can always merge without losing money; hence, we can assume that players form the grand coalition

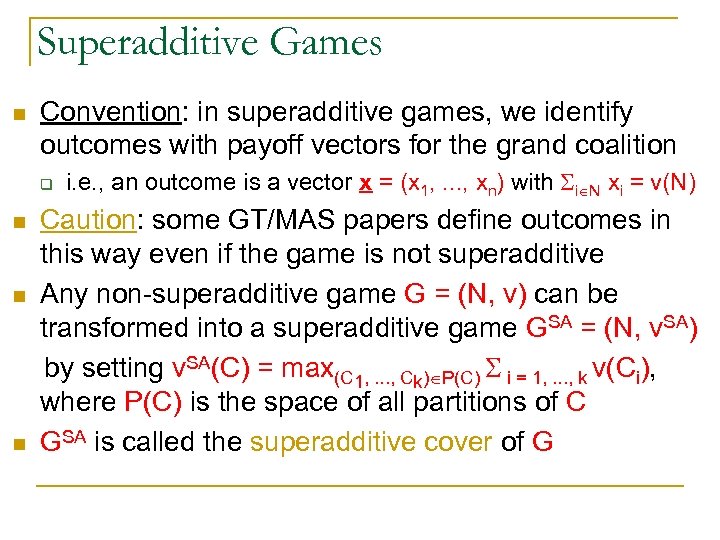

Superadditive Games n Convention: in superadditive games, we identify outcomes with payoff vectors for the grand coalition q n n n i. e. , an outcome is a vector x = (x 1, . . . , xn) with Si N xi = v(N) Caution: some GT/MAS papers define outcomes in this way even if the game is not superadditive Any non-superadditive game G = (N, v) can be transformed into a superadditive game GSA = (N, v. SA) by setting v. SA(C) = max(C 1, . . . , Ck) P(C) S i = 1, . . . , k v(Ci), where P(C) is the space of all partitions of C GSA is called the superadditive cover of G

Superadditive Games n Convention: in superadditive games, we identify outcomes with payoff vectors for the grand coalition q n n n i. e. , an outcome is a vector x = (x 1, . . . , xn) with Si N xi = v(N) Caution: some GT/MAS papers define outcomes in this way even if the game is not superadditive Any non-superadditive game G = (N, v) can be transformed into a superadditive game GSA = (N, v. SA) by setting v. SA(C) = max(C 1, . . . , Ck) P(C) S i = 1, . . . , k v(Ci), where P(C) is the space of all partitions of C GSA is called the superadditive cover of G

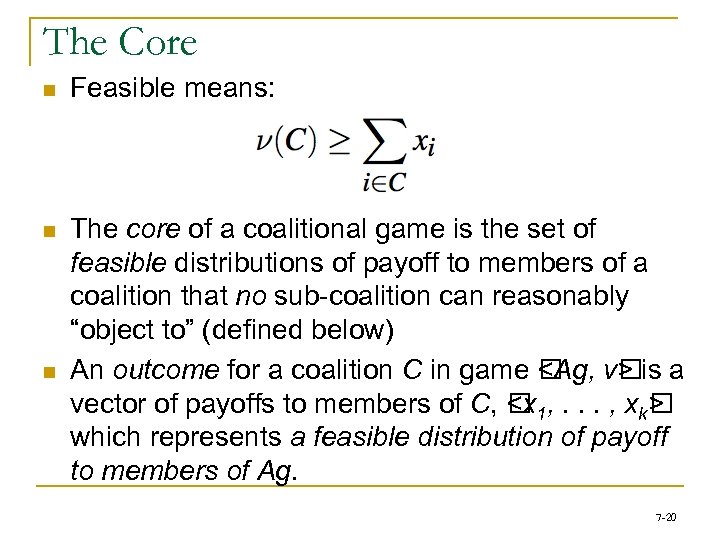

The Core n Feasible means: n The core of a coalitional game is the set of feasible distributions of payoff to members of a coalition that no sub-coalition can reasonably “object to” (defined below) An outcome for a coalition C in game ν is a

The Core n Feasible means: n The core of a coalitional game is the set of feasible distributions of payoff to members of a coalition that no sub-coalition can reasonably “object to” (defined below) An outcome for a coalition C in game ν is a

Example n If ν({1, 2}) = 20, then possible outcomes are <20, 0 1> 18, 2 . . . , 20 >, <19, , < >, <0, >. (Actually there will be infinitely many!) 7 -21

Example n If ν({1, 2}) = 20, then possible outcomes are <20, 0 1> 18, 2 . . . , 20 >, <19, , < >, <0, >. (Actually there will be infinitely many!) 7 -21

Objections n n n Intuitively, a coalition C objects to an outcome if there is some outcome for them that makes all of them strictly better off Formally, C ⊆ Ag objects to an outcome 1, …, xn

Objections n n n Intuitively, a coalition C objects to an outcome if there is some outcome for them that makes all of them strictly better off Formally, C ⊆ Ag objects to an outcome 1, …, xn

The Core n n The core is the set of outcomes for the grand coalition to which no coalition objects (The grand coalition is particularly interesting if the characteristic function v is superadditive) If the core is non-empty then the grand coalition is stable, since nobody can benefit from defection Thus, asking is the grand coalition stable? is the same as asking: is the core non-empty? 7 -23

The Core n n The core is the set of outcomes for the grand coalition to which no coalition objects (The grand coalition is particularly interesting if the characteristic function v is superadditive) If the core is non-empty then the grand coalition is stable, since nobody can benefit from defection Thus, asking is the grand coalition stable? is the same as asking: is the core non-empty? 7 -23

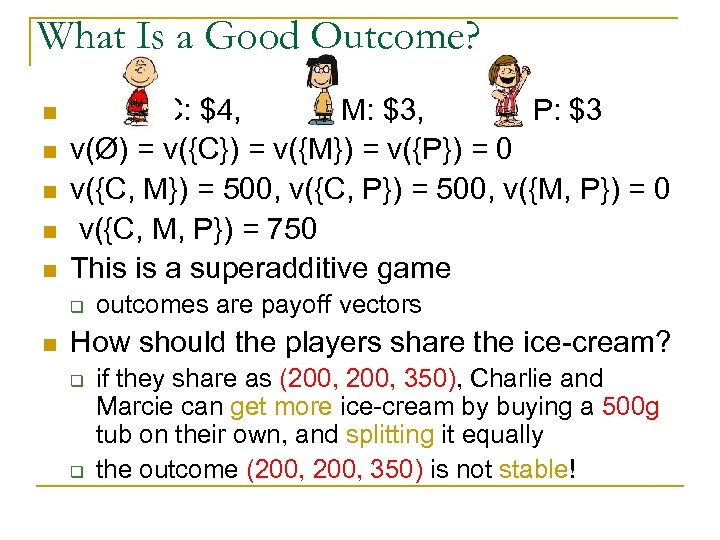

What Is a Good Outcome? n n n C: $4, M: $3, P: $3 v(Ø) = v({C}) = v({M}) = v({P}) = 0 v({C, M}) = 500, v({C, P}) = 500, v({M, P}) = 0 v({C, M, P}) = 750 This is a superadditive game q n outcomes are payoff vectors How should the players share the ice-cream? q q if they share as (200, 350), Charlie and Marcie can get more ice-cream by buying a 500 g tub on their own, and splitting it equally the outcome (200, 350) is not stable!

What Is a Good Outcome? n n n C: $4, M: $3, P: $3 v(Ø) = v({C}) = v({M}) = v({P}) = 0 v({C, M}) = 500, v({C, P}) = 500, v({M, P}) = 0 v({C, M, P}) = 750 This is a superadditive game q n outcomes are payoff vectors How should the players share the ice-cream? q q if they share as (200, 350), Charlie and Marcie can get more ice-cream by buying a 500 g tub on their own, and splitting it equally the outcome (200, 350) is not stable!

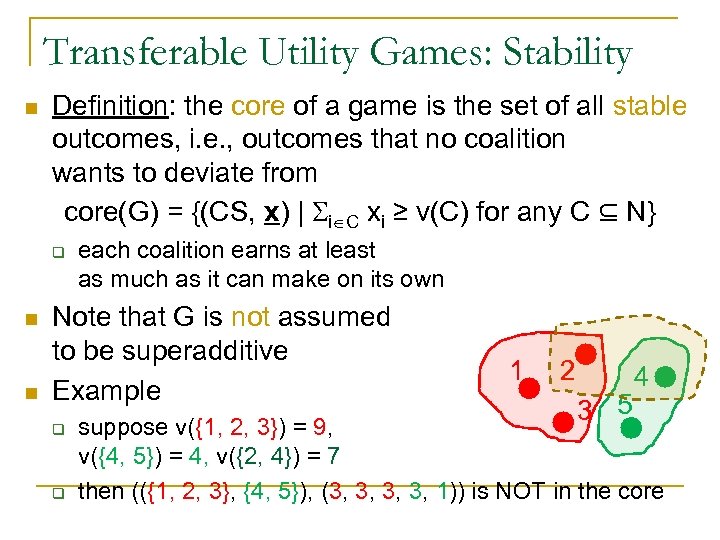

Transferable Utility Games: Stability n Definition: the core of a game is the set of all stable outcomes, i. e. , outcomes that no coalition wants to deviate from core(G) = {(CS, x) | Si C xi ≥ v(C) for any C ⊆ N} q n n each coalition earns at least as much as it can make on its own Note that G is not assumed to be superadditive Example q q 1 2 3 5 4 suppose v({1, 2, 3}) = 9, v({4, 5}) = 4, v({2, 4}) = 7 then (({1, 2, 3}, {4, 5}), (3, 3, 1)) is NOT in the core

Transferable Utility Games: Stability n Definition: the core of a game is the set of all stable outcomes, i. e. , outcomes that no coalition wants to deviate from core(G) = {(CS, x) | Si C xi ≥ v(C) for any C ⊆ N} q n n each coalition earns at least as much as it can make on its own Note that G is not assumed to be superadditive Example q q 1 2 3 5 4 suppose v({1, 2, 3}) = 9, v({4, 5}) = 4, v({2, 4}) = 7 then (({1, 2, 3}, {4, 5}), (3, 3, 1)) is NOT in the core

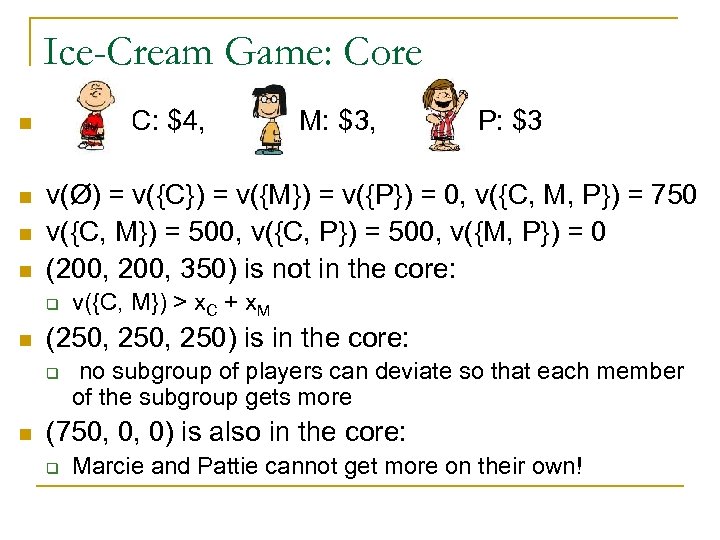

Ice-Cream Game: Core C: $4, n n v({C, M}) > x. C + x. M (250, 250) is in the core: q n P: $3 v(Ø) = v({C}) = v({M}) = v({P}) = 0, v({C, M, P}) = 750 v({C, M}) = 500, v({C, P}) = 500, v({M, P}) = 0 (200, 350) is not in the core: q n M: $3, no subgroup of players can deviate so that each member of the subgroup gets more (750, 0, 0) is also in the core: q Marcie and Pattie cannot get more on their own!

Ice-Cream Game: Core C: $4, n n v({C, M}) > x. C + x. M (250, 250) is in the core: q n P: $3 v(Ø) = v({C}) = v({M}) = v({P}) = 0, v({C, M, P}) = 750 v({C, M}) = 500, v({C, P}) = 500, v({M, P}) = 0 (200, 350) is not in the core: q n M: $3, no subgroup of players can deviate so that each member of the subgroup gets more (750, 0, 0) is also in the core: q Marcie and Pattie cannot get more on their own!

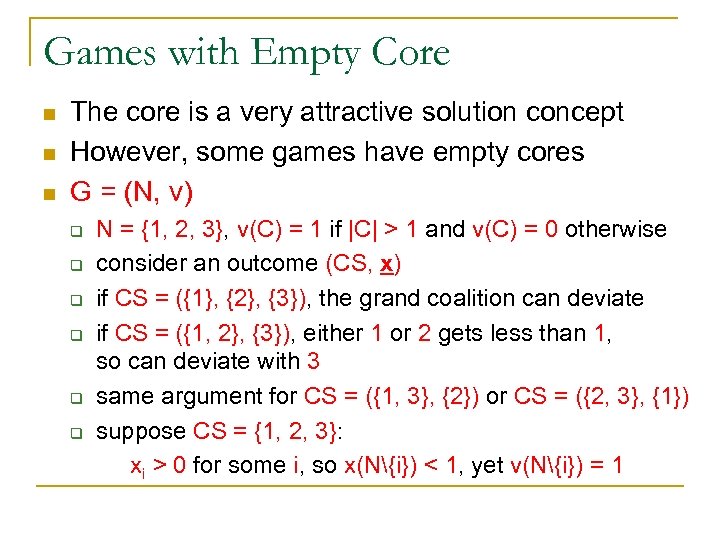

Games with Empty Core n n n The core is a very attractive solution concept However, some games have empty cores G = (N, v) q q q N = {1, 2, 3}, v(C) = 1 if |C| > 1 and v(C) = 0 otherwise consider an outcome (CS, x) if CS = ({1}, {2}, {3}), the grand coalition can deviate if CS = ({1, 2}, {3}), either 1 or 2 gets less than 1, so can deviate with 3 same argument for CS = ({1, 3}, {2}) or CS = ({2, 3}, {1}) suppose CS = {1, 2, 3}: xi > 0 for some i, so x(N{i}) < 1, yet v(N{i}) = 1

Games with Empty Core n n n The core is a very attractive solution concept However, some games have empty cores G = (N, v) q q q N = {1, 2, 3}, v(C) = 1 if |C| > 1 and v(C) = 0 otherwise consider an outcome (CS, x) if CS = ({1}, {2}, {3}), the grand coalition can deviate if CS = ({1, 2}, {3}), either 1 or 2 gets less than 1, so can deviate with 3 same argument for CS = ({1, 3}, {2}) or CS = ({2, 3}, {1}) suppose CS = {1, 2, 3}: xi > 0 for some i, so x(N{i}) < 1, yet v(N{i}) = 1

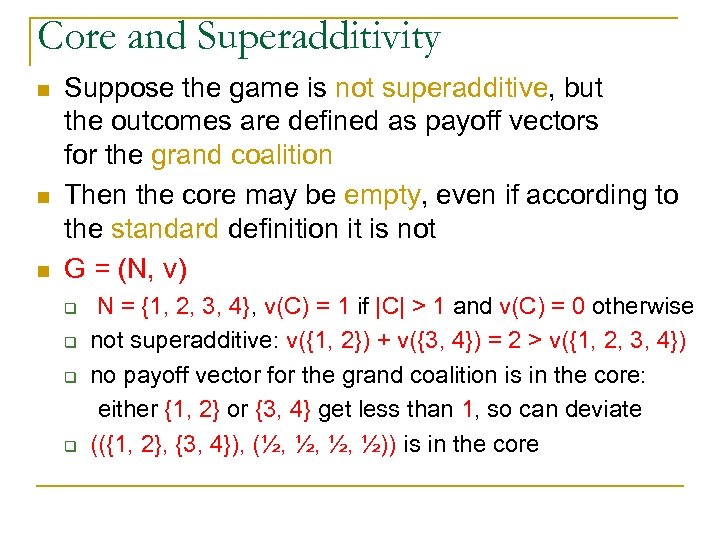

Core and Superadditivity n n n Suppose the game is not superadditive, but the outcomes are defined as payoff vectors for the grand coalition Then the core may be empty, even if according to the standard definition it is not G = (N, v) q q N = {1, 2, 3, 4}, v(C) = 1 if |C| > 1 and v(C) = 0 otherwise not superadditive: v({1, 2}) + v({3, 4}) = 2 > v({1, 2, 3, 4}) no payoff vector for the grand coalition is in the core: either {1, 2} or {3, 4} get less than 1, so can deviate (({1, 2}, {3, 4}), (½, ½, ½, ½)) is in the core

Core and Superadditivity n n n Suppose the game is not superadditive, but the outcomes are defined as payoff vectors for the grand coalition Then the core may be empty, even if according to the standard definition it is not G = (N, v) q q N = {1, 2, 3, 4}, v(C) = 1 if |C| > 1 and v(C) = 0 otherwise not superadditive: v({1, 2}) + v({3, 4}) = 2 > v({1, 2, 3, 4}) no payoff vector for the grand coalition is in the core: either {1, 2} or {3, 4} get less than 1, so can deviate (({1, 2}, {3, 4}), (½, ½, ½, ½)) is in the core

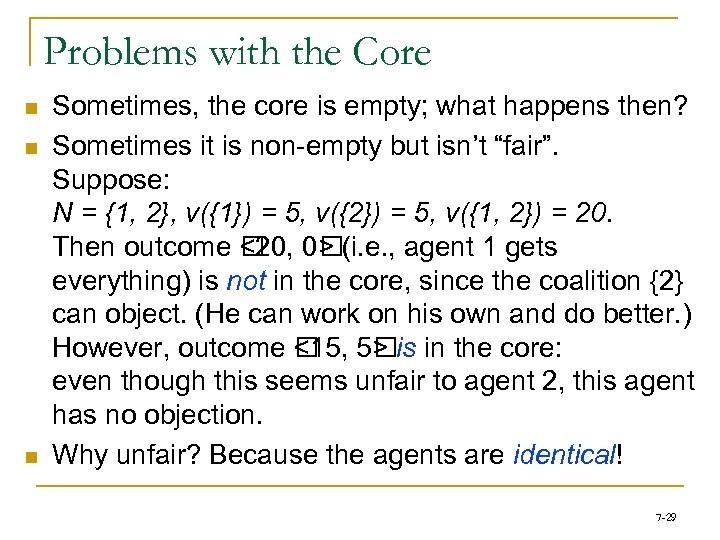

Problems with the Core n n n Sometimes, the core is empty; what happens then? Sometimes it is non-empty but isn’t “fair”. Suppose: N = {1, 2}, ν({1}) = 5, ν({2}) = 5, ν({1, 2}) = 20. Then outcome 0 (i. e. , agent 1 gets <20, > everything) is not in the core, since the coalition {2} can object. (He can work on his own and do better. ) However, outcome 5 is in the core: <15, > even though this seems unfair to agent 2, this agent has no objection. Why unfair? Because the agents are identical! 7 -29

Problems with the Core n n n Sometimes, the core is empty; what happens then? Sometimes it is non-empty but isn’t “fair”. Suppose: N = {1, 2}, ν({1}) = 5, ν({2}) = 5, ν({1, 2}) = 20. Then outcome 0 (i. e. , agent 1 gets <20, > everything) is not in the core, since the coalition {2} can object. (He can work on his own and do better. ) However, outcome 5 is in the core: <15, > even though this seems unfair to agent 2, this agent has no objection. Why unfair? Because the agents are identical! 7 -29

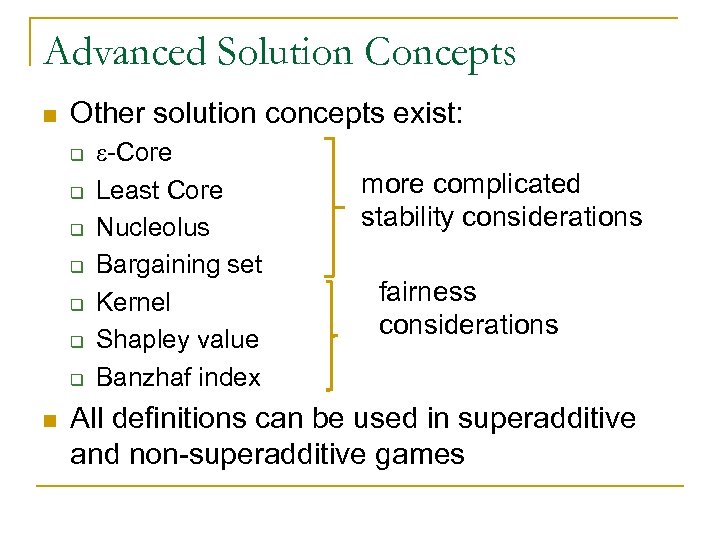

Advanced Solution Concepts n Other solution concepts exist: q q q q n e-Core Least Core Nucleolus Bargaining set Kernel Shapley value Banzhaf index more complicated stability considerations fairness considerations All definitions can be used in superadditive and non-superadditive games

Advanced Solution Concepts n Other solution concepts exist: q q q q n e-Core Least Core Nucleolus Bargaining set Kernel Shapley value Banzhaf index more complicated stability considerations fairness considerations All definitions can be used in superadditive and non-superadditive games

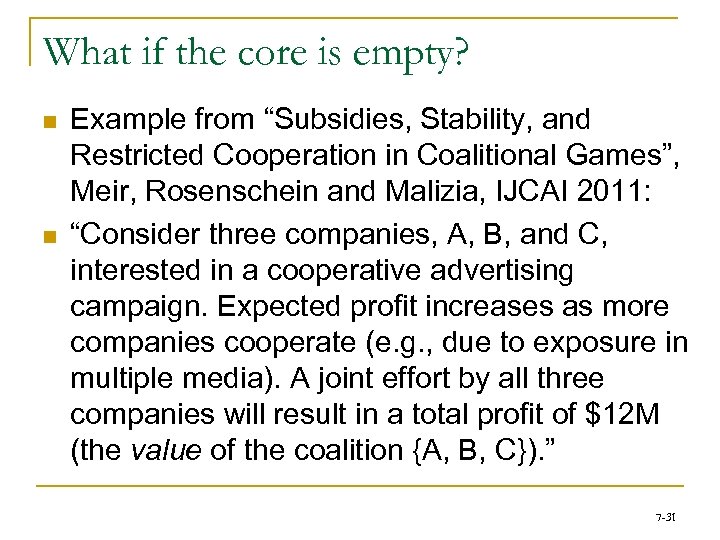

What if the core is empty? n n Example from “Subsidies, Stability, and Restricted Cooperation in Coalitional Games”, Meir, Rosenschein and Malizia, IJCAI 2011: “Consider three companies, A, B, and C, interested in a cooperative advertising campaign. Expected profit increases as more companies cooperate (e. g. , due to exposure in multiple media). A joint effort by all three companies will result in a total profit of $12 M (the value of the coalition {A, B, C}). ” 7 -31

What if the core is empty? n n Example from “Subsidies, Stability, and Restricted Cooperation in Coalitional Games”, Meir, Rosenschein and Malizia, IJCAI 2011: “Consider three companies, A, B, and C, interested in a cooperative advertising campaign. Expected profit increases as more companies cooperate (e. g. , due to exposure in multiple media). A joint effort by all three companies will result in a total profit of $12 M (the value of the coalition {A, B, C}). ” 7 -31

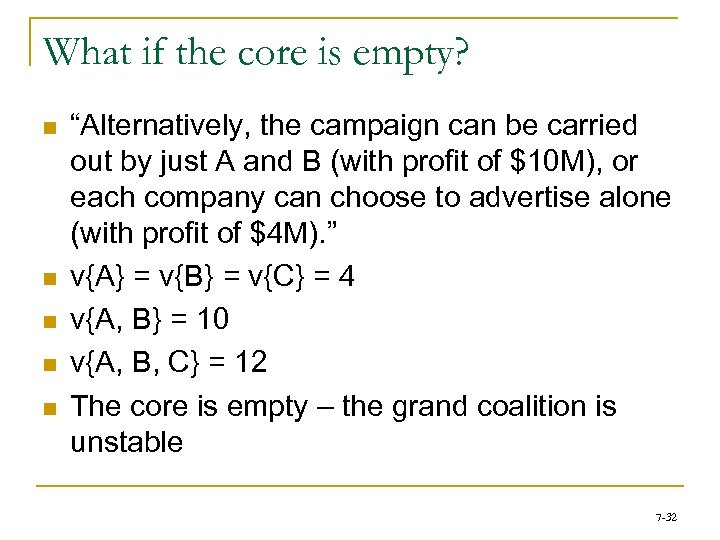

What if the core is empty? n n n “Alternatively, the campaign can be carried out by just A and B (with profit of $10 M), or each company can choose to advertise alone (with profit of $4 M). ” v{A} = v{B} = v{C} = 4 v{A, B} = 10 v{A, B, C} = 12 The core is empty – the grand coalition is unstable 7 -32

What if the core is empty? n n n “Alternatively, the campaign can be carried out by just A and B (with profit of $10 M), or each company can choose to advertise alone (with profit of $4 M). ” v{A} = v{B} = v{C} = 4 v{A, B} = 10 v{A, B, C} = 12 The core is empty – the grand coalition is unstable 7 -32

Cost of Stability n n n Some outside source injects a subsidy into the coalition, in order to create stability In the above example, a subsidy of $2 M enables a payment of $5 M to A, $5 M to B, and $4 M to C, creating grand coalition stability Another example: 3 hospitals who could cooperate to buy an expensive piece of equipment (and a government subsidy would make it worthwhile for them to cooperate) 7 -33

Cost of Stability n n n Some outside source injects a subsidy into the coalition, in order to create stability In the above example, a subsidy of $2 M enables a payment of $5 M to A, $5 M to B, and $4 M to C, creating grand coalition stability Another example: 3 hospitals who could cooperate to buy an expensive piece of equipment (and a government subsidy would make it worthwhile for them to cooperate) 7 -33

An area of ongoing research n n n Bounding the Cost of Stability in Games over Interaction Networks, Reshef Meir, Yair Zick, Edith Elkind, and Jeffrey S. Rosenschein. The Twenty-Seventh National Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI 2013), Bellevue, Washington, July 2013. To appear. Subsidies, Stability, and Restricted Cooperation in Coalitional Games, Reshef Meir, Jeffrey S. Rosenschein, and Enrico Malizia. The Twenty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 2011), Barcelona, July 2011, pages 301 -306. The Cost of Stability in Weighted Voting Games (Extended Abstract), Yoram Bachrach, Reshef Meir, Michael Zuckerman, Joerg Rothe, and Jeffrey S. Rosenschein. The Eighth International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Budapest, Hungary, May 2009, pages 1289 -1290. The Cost of Stability in Network Flow Games, Ezra Resnick, Yoram Bachrach, Reshef Meir, and Jeffrey S. Rosenschein. Mathematical Foundations of Computer Science 2009: The Thirty-Fourth International Symposium on Mathematical Foundations of Computer Science, Novy Smokovec, High Tatras, Slovakia, August 2009. Lecture Notes in Computer Science Volume 5734, R. Kralovic and D. Niwinski (editors), Springer, 2009, pages 636650. Power and Stability in Connectivity Games, Yoram Bachrach, Jeffrey S. Rosenschein, and Ely Porat. The Seventh International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Estoril, Portugal, May 2008, pages 999 -1006. 7 -34

An area of ongoing research n n n Bounding the Cost of Stability in Games over Interaction Networks, Reshef Meir, Yair Zick, Edith Elkind, and Jeffrey S. Rosenschein. The Twenty-Seventh National Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI 2013), Bellevue, Washington, July 2013. To appear. Subsidies, Stability, and Restricted Cooperation in Coalitional Games, Reshef Meir, Jeffrey S. Rosenschein, and Enrico Malizia. The Twenty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 2011), Barcelona, July 2011, pages 301 -306. The Cost of Stability in Weighted Voting Games (Extended Abstract), Yoram Bachrach, Reshef Meir, Michael Zuckerman, Joerg Rothe, and Jeffrey S. Rosenschein. The Eighth International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Budapest, Hungary, May 2009, pages 1289 -1290. The Cost of Stability in Network Flow Games, Ezra Resnick, Yoram Bachrach, Reshef Meir, and Jeffrey S. Rosenschein. Mathematical Foundations of Computer Science 2009: The Thirty-Fourth International Symposium on Mathematical Foundations of Computer Science, Novy Smokovec, High Tatras, Slovakia, August 2009. Lecture Notes in Computer Science Volume 5734, R. Kralovic and D. Niwinski (editors), Springer, 2009, pages 636650. Power and Stability in Connectivity Games, Yoram Bachrach, Jeffrey S. Rosenschein, and Ely Porat. The Seventh International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Estoril, Portugal, May 2008, pages 999 -1006. 7 -34

Stability vs. Fairness n n Outcomes in the core may be unfair G = (N, v) q n (15, 5) is in the core: q n n N = {1, 2}, v(Ø) = 0, v({1}) = v({2}) = 5, v({1, 2}) = 20 player 2 cannot benefit by deviating However, this is unfair since 1 and 2 are symmetric How do we divide payoffs in a fair way?

Stability vs. Fairness n n Outcomes in the core may be unfair G = (N, v) q n (15, 5) is in the core: q n n N = {1, 2}, v(Ø) = 0, v({1}) = v({2}) = 5, v({1, 2}) = 20 player 2 cannot benefit by deviating However, this is unfair since 1 and 2 are symmetric How do we divide payoffs in a fair way?

Marginal Contribution n n A fair payment scheme would reward each agent according to his contribution First attempt: given a game G = (N, v), set xi = v({1, . . . , i-1, i}) - v({1, . . . , i-1}) q n We have x 1 +. . . + xn = v(N) q n n payoff to each player = his marginal contribution to the coalition of his predecessors x is a payoff vector However, payoff to each player depends on the order G = (N, v) q q N = {1, 2}, v(Ø) = 0, v({1}) = v({2}) = 5, v({1, 2}) = 20 x 1 = v(1) - v(Ø) = 5, x 2 = v({1, 2}) - v({1}) = 15

Marginal Contribution n n A fair payment scheme would reward each agent according to his contribution First attempt: given a game G = (N, v), set xi = v({1, . . . , i-1, i}) - v({1, . . . , i-1}) q n We have x 1 +. . . + xn = v(N) q n n payoff to each player = his marginal contribution to the coalition of his predecessors x is a payoff vector However, payoff to each player depends on the order G = (N, v) q q N = {1, 2}, v(Ø) = 0, v({1}) = v({2}) = 5, v({1, 2}) = 20 x 1 = v(1) - v(Ø) = 5, x 2 = v({1, 2}) - v({1}) = 15

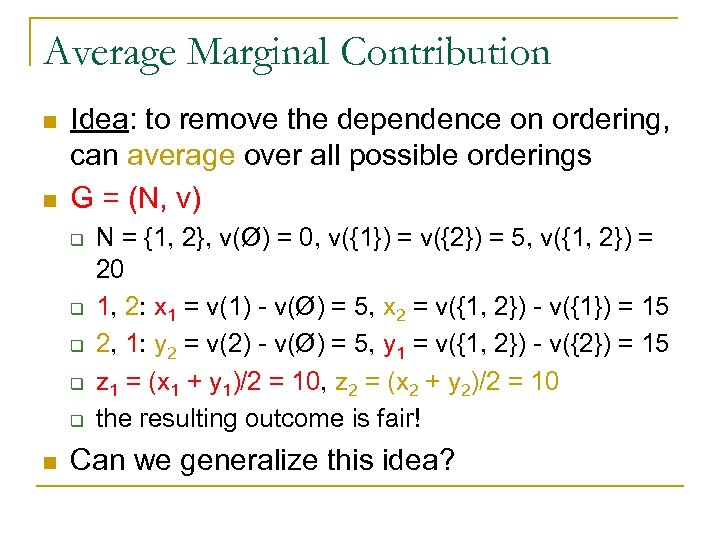

Average Marginal Contribution n n Idea: to remove the dependence on ordering, can average over all possible orderings G = (N, v) q q q n N = {1, 2}, v(Ø) = 0, v({1}) = v({2}) = 5, v({1, 2}) = 20 1, 2: x 1 = v(1) - v(Ø) = 5, x 2 = v({1, 2}) - v({1}) = 15 2, 1: y 2 = v(2) - v(Ø) = 5, y 1 = v({1, 2}) - v({2}) = 15 z 1 = (x 1 + y 1)/2 = 10, z 2 = (x 2 + y 2)/2 = 10 the resulting outcome is fair! Can we generalize this idea?

Average Marginal Contribution n n Idea: to remove the dependence on ordering, can average over all possible orderings G = (N, v) q q q n N = {1, 2}, v(Ø) = 0, v({1}) = v({2}) = 5, v({1, 2}) = 20 1, 2: x 1 = v(1) - v(Ø) = 5, x 2 = v({1, 2}) - v({1}) = 15 2, 1: y 2 = v(2) - v(Ø) = 5, y 1 = v({1, 2}) - v({2}) = 15 z 1 = (x 1 + y 1)/2 = 10, z 2 = (x 2 + y 2)/2 = 10 the resulting outcome is fair! Can we generalize this idea?

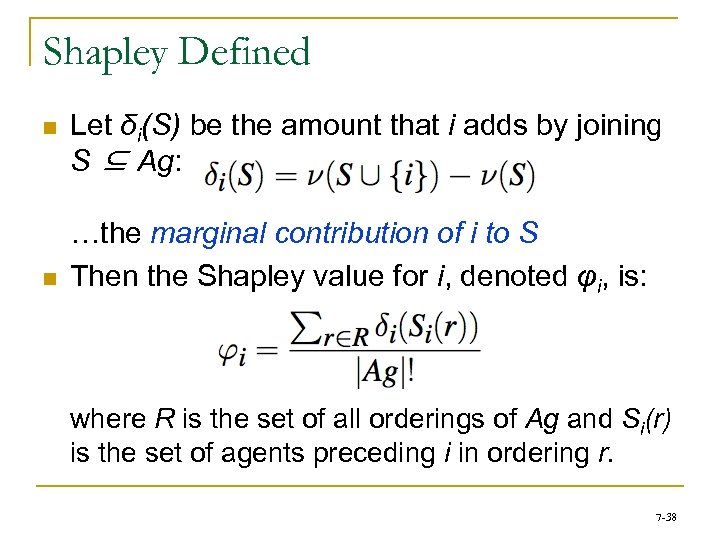

Shapley Defined n n Let δi(S) be the amount that i adds by joining S ⊆ Ag: …the marginal contribution of i to S Then the Shapley value for i, denoted φi, is: where R is the set of all orderings of Ag and Si(r) is the set of agents preceding i in ordering r. 7 -38

Shapley Defined n n Let δi(S) be the amount that i adds by joining S ⊆ Ag: …the marginal contribution of i to S Then the Shapley value for i, denoted φi, is: where R is the set of all orderings of Ag and Si(r) is the set of agents preceding i in ordering r. 7 -38

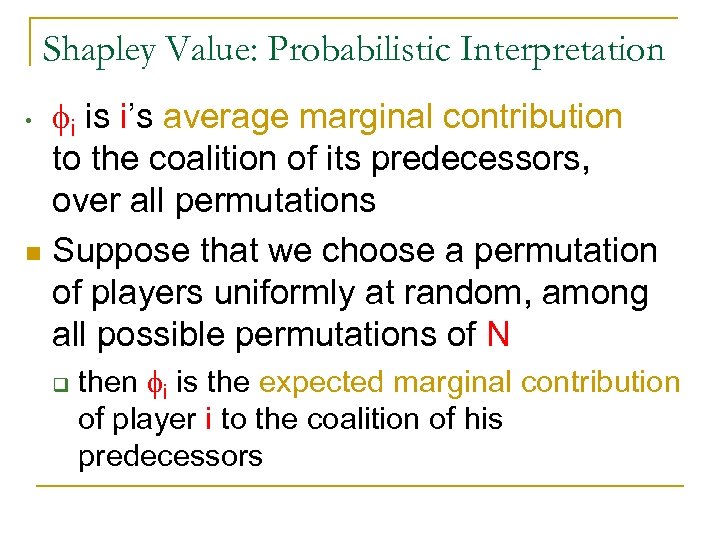

Shapley Value: Probabilistic Interpretation fi is i’s average marginal contribution to the coalition of its predecessors, over all permutations n Suppose that we choose a permutation of players uniformly at random, among all possible permutations of N • q then fi is the expected marginal contribution of player i to the coalition of his predecessors

Shapley Value: Probabilistic Interpretation fi is i’s average marginal contribution to the coalition of its predecessors, over all permutations n Suppose that we choose a permutation of players uniformly at random, among all possible permutations of N • q then fi is the expected marginal contribution of player i to the coalition of his predecessors

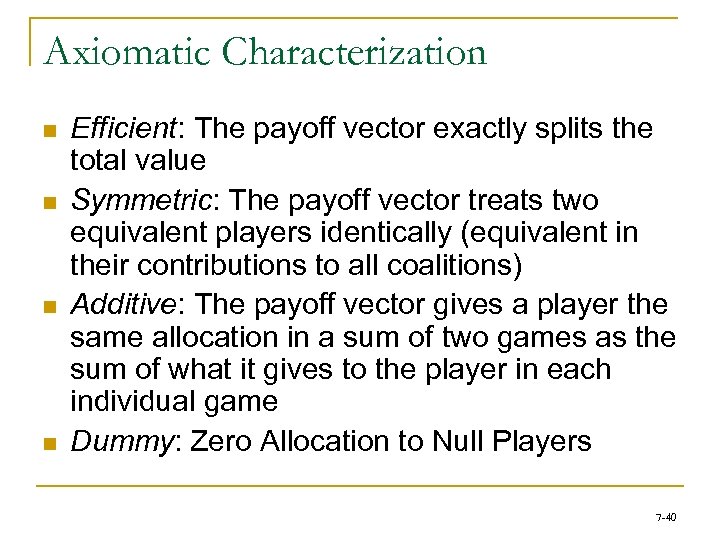

Axiomatic Characterization n n Efficient: The payoff vector exactly splits the total value Symmetric: The payoff vector treats two equivalent players identically (equivalent in their contributions to all coalitions) Additive: The payoff vector gives a player the same allocation in a sum of two games as the sum of what it gives to the player in each individual game Dummy: Zero Allocation to Null Players 7 -40

Axiomatic Characterization n n Efficient: The payoff vector exactly splits the total value Symmetric: The payoff vector treats two equivalent players identically (equivalent in their contributions to all coalitions) Additive: The payoff vector gives a player the same allocation in a sum of two games as the sum of what it gives to the player in each individual game Dummy: Zero Allocation to Null Players 7 -40

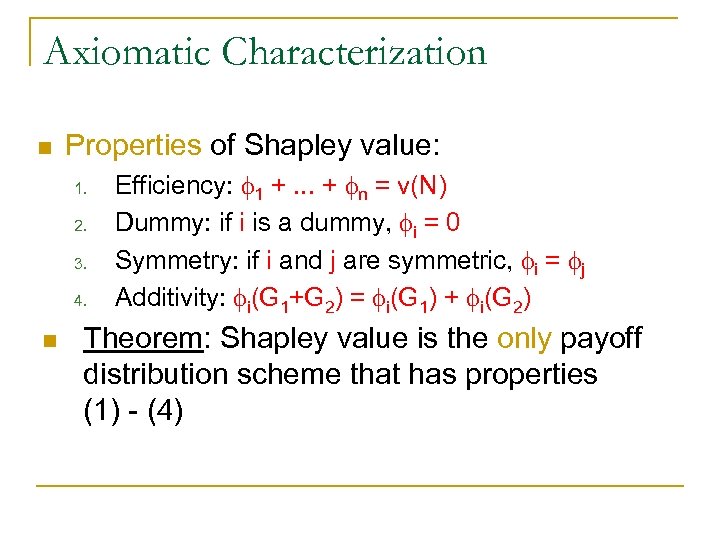

Axiomatic Characterization n Properties of Shapley value: 1. 2. 3. 4. n Efficiency: f 1 +. . . + fn = v(N) Dummy: if i is a dummy, fi = 0 Symmetry: if i and j are symmetric, fi = fj Additivity: fi(G 1+G 2) = fi(G 1) + fi(G 2) Theorem: Shapley value is the only payoff distribution scheme that has properties (1) - (4)

Axiomatic Characterization n Properties of Shapley value: 1. 2. 3. 4. n Efficiency: f 1 +. . . + fn = v(N) Dummy: if i is a dummy, fi = 0 Symmetry: if i and j are symmetric, fi = fj Additivity: fi(G 1+G 2) = fi(G 1) + fi(G 2) Theorem: Shapley value is the only payoff distribution scheme that has properties (1) - (4)

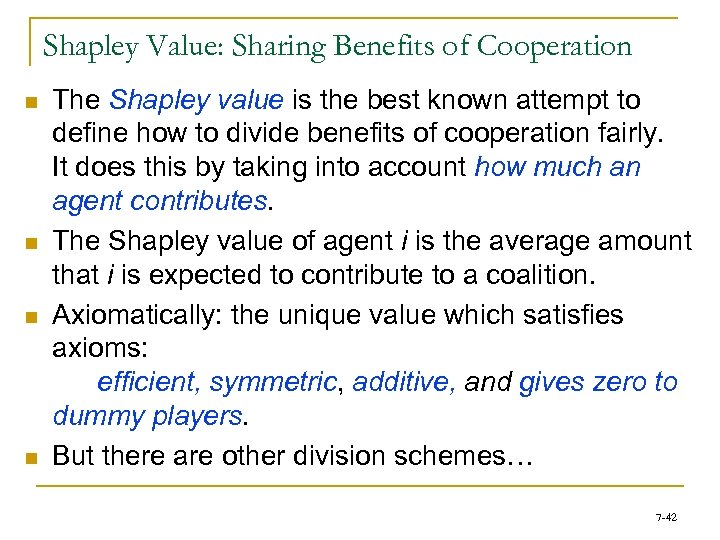

Shapley Value: Sharing Benefits of Cooperation n n The Shapley value is the best known attempt to define how to divide benefits of cooperation fairly. It does this by taking into account how much an agent contributes. The Shapley value of agent i is the average amount that i is expected to contribute to a coalition. Axiomatically: the unique value which satisfies axioms: efficient, symmetric, additive, and gives zero to dummy players. But there are other division schemes… 7 -42

Shapley Value: Sharing Benefits of Cooperation n n The Shapley value is the best known attempt to define how to divide benefits of cooperation fairly. It does this by taking into account how much an agent contributes. The Shapley value of agent i is the average amount that i is expected to contribute to a coalition. Axiomatically: the unique value which satisfies axioms: efficient, symmetric, additive, and gives zero to dummy players. But there are other division schemes… 7 -42

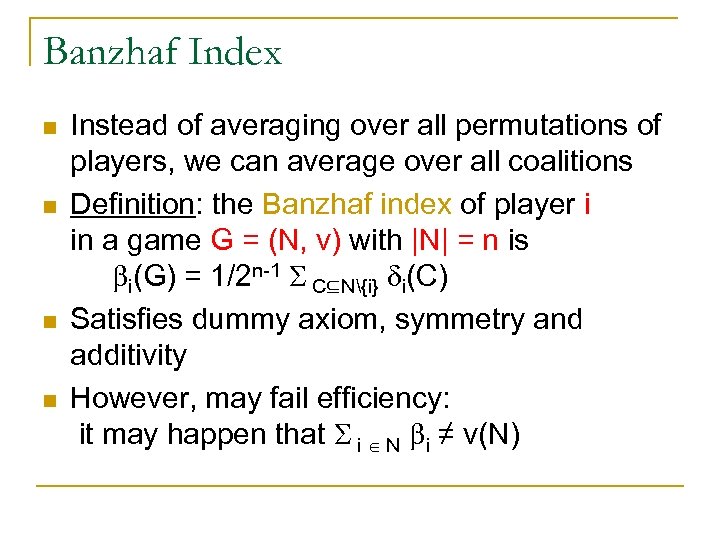

Banzhaf Index n n Instead of averaging over all permutations of players, we can average over all coalitions Definition: the Banzhaf index of player i in a game G = (N, v) with |N| = n is bi(G) = 1/2 n-1 S C⊆N{i} di(C) Satisfies dummy axiom, symmetry and additivity However, may fail efficiency: it may happen that S i N bi ≠ v(N)

Banzhaf Index n n Instead of averaging over all permutations of players, we can average over all coalitions Definition: the Banzhaf index of player i in a game G = (N, v) with |N| = n is bi(G) = 1/2 n-1 S C⊆N{i} di(C) Satisfies dummy axiom, symmetry and additivity However, may fail efficiency: it may happen that S i N bi ≠ v(N)

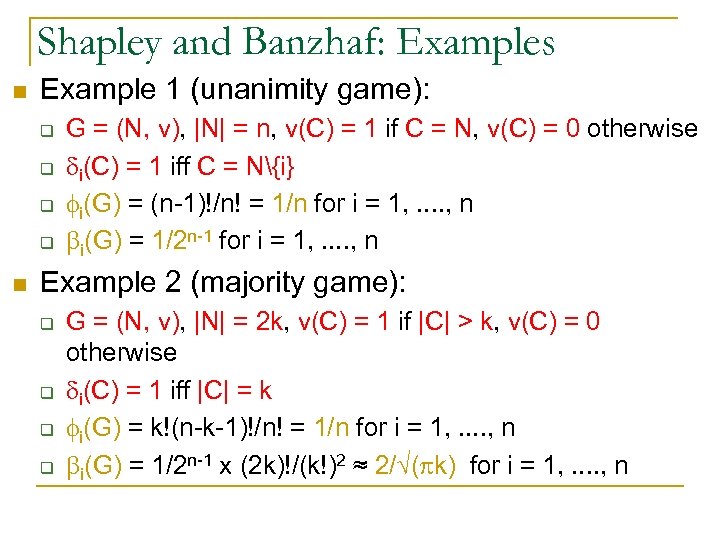

Shapley and Banzhaf: Examples n Example 1 (unanimity game): q q n G = (N, v), |N| = n, v(C) = 1 if C = N, v(C) = 0 otherwise di(C) = 1 iff C = N{i} fi(G) = (n-1)!/n! = 1/n for i = 1, . . , n bi(G) = 1/2 n-1 for i = 1, . . , n Example 2 (majority game): q q G = (N, v), |N| = 2 k, v(C) = 1 if |C| > k, v(C) = 0 otherwise di(C) = 1 iff |C| = k fi(G) = k!(n-k-1)!/n! = 1/n for i = 1, . . , n bi(G) = 1/2 n-1 x (2 k)!/(k!)2 ≈ 2/√(pk) for i = 1, . . , n

Shapley and Banzhaf: Examples n Example 1 (unanimity game): q q n G = (N, v), |N| = n, v(C) = 1 if C = N, v(C) = 0 otherwise di(C) = 1 iff C = N{i} fi(G) = (n-1)!/n! = 1/n for i = 1, . . , n bi(G) = 1/2 n-1 for i = 1, . . , n Example 2 (majority game): q q G = (N, v), |N| = 2 k, v(C) = 1 if |C| > k, v(C) = 0 otherwise di(C) = 1 iff |C| = k fi(G) = k!(n-k-1)!/n! = 1/n for i = 1, . . , n bi(G) = 1/2 n-1 x (2 k)!/(k!)2 ≈ 2/√(pk) for i = 1, . . , n

Imputations n n n A pre-imputation is an efficient payoff vector An individually rational pre-imputation (i. e. , one that gives each player at least as much as it could get alone) is called an imputation Most solution concepts (and in particular, the Shapley Value for superadditive games) are imputations 7 -45

Imputations n n n A pre-imputation is an efficient payoff vector An individually rational pre-imputation (i. e. , one that gives each player at least as much as it could get alone) is called an imputation Most solution concepts (and in particular, the Shapley Value for superadditive games) are imputations 7 -45

Representing Coalitional Games n n n It is important for an agent to know (for example) whether the core of a coalition is non-empty…so, how hard is it to decide this? Problem: naive, obvious representation of coalitional game is exponential in the size of Ag Now such a representation is: – utterly infeasible in practice; and – so large that it renders comparisons to this input size meaningless: stating that we have an algorithm that runs in (say) time linear in the size of such a representation means it runs in time exponential in the size of Ag 7 -46

Representing Coalitional Games n n n It is important for an agent to know (for example) whether the core of a coalition is non-empty…so, how hard is it to decide this? Problem: naive, obvious representation of coalitional game is exponential in the size of Ag Now such a representation is: – utterly infeasible in practice; and – so large that it renders comparisons to this input size meaningless: stating that we have an algorithm that runs in (say) time linear in the size of such a representation means it runs in time exponential in the size of Ag 7 -46

How to Represent Characteristic Functions? n Three approaches to this problem: q Strategy 1: oracle representation n n q Strategy 2: restricted classes n n q assume that we have a black-box poly-time algorithm that, given a coalition C ⊆ N, outputs its value v(C) for some special classes of games, this allows us compute some solution concepts using polynomially many queries consider games on combinatorial structures problem: not all games can be represented in this way Strategy 3: give up on worst-case succinctness n devise complete representation languages that allow for compact representation of interesting games 7 -47

How to Represent Characteristic Functions? n Three approaches to this problem: q Strategy 1: oracle representation n n q Strategy 2: restricted classes n n q assume that we have a black-box poly-time algorithm that, given a coalition C ⊆ N, outputs its value v(C) for some special classes of games, this allows us compute some solution concepts using polynomially many queries consider games on combinatorial structures problem: not all games can be represented in this way Strategy 3: give up on worst-case succinctness n devise complete representation languages that allow for compact representation of interesting games 7 -47

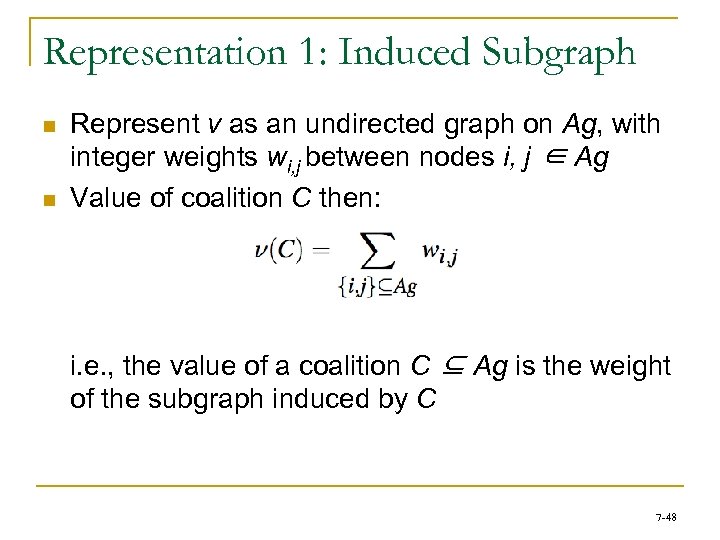

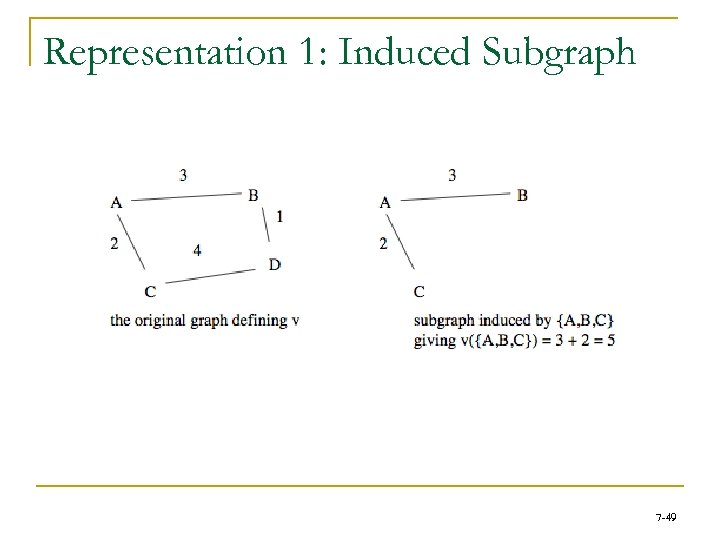

Representation 1: Induced Subgraph n n Represent ν as an undirected graph on Ag, with integer weights wi, j between nodes i, j ∈ Ag Value of coalition C then: i. e. , the value of a coalition C ⊆ Ag is the weight of the subgraph induced by C 7 -48

Representation 1: Induced Subgraph n n Represent ν as an undirected graph on Ag, with integer weights wi, j between nodes i, j ∈ Ag Value of coalition C then: i. e. , the value of a coalition C ⊆ Ag is the weight of the subgraph induced by C 7 -48

Representation 1: Induced Subgraph 7 -49

Representation 1: Induced Subgraph 7 -49

Representation 1: Induced Subgraph (Deng & Papadimitriou, 94) n Computing Shapley: in polynomial time n Determining emptiness of the core: NP-complete n Checking whether a specific distribution is in the core: co-NP-complete n But this representation is not complete 7 -50

Representation 1: Induced Subgraph (Deng & Papadimitriou, 94) n Computing Shapley: in polynomial time n Determining emptiness of the core: NP-complete n Checking whether a specific distribution is in the core: co-NP-complete n But this representation is not complete 7 -50

Representation 2: Weighted Voting Games n For each agent i ∈ Ag, assign a weight wi, and define an overall quota, q. n Shapley value: #P-complete, and “hard to approximate” (Deng & Papadimitriou, 94) Core non-emptiness: in polynomial time Not a complete representation n n 7 -51

Representation 2: Weighted Voting Games n For each agent i ∈ Ag, assign a weight wi, and define an overall quota, q. n Shapley value: #P-complete, and “hard to approximate” (Deng & Papadimitriou, 94) Core non-emptiness: in polynomial time Not a complete representation n n 7 -51

Simple Games (e. g. , weighted voting) n Definition: a game G = (N, v) is simple if q q n n A coalition C in a simple game is said to be winning if v(C) = 1 and losing if v(C) = 0 Definition: in a simple game, a player i is a veto player if v(C) = 0 for any C ⊆ N{i} q n n v(C) {0, 1} for any C ⊆ N v is monotone: if v(C) = 1 and C ⊆ D, then v(D) = 1 equivalently, by monotonicity, v(N{i}) = 0 Traditionally, in simple games an outcome is identified with a payoff vector for N Theorem: a simple game has a non-empty core iff it has a veto player.

Simple Games (e. g. , weighted voting) n Definition: a game G = (N, v) is simple if q q n n A coalition C in a simple game is said to be winning if v(C) = 1 and losing if v(C) = 0 Definition: in a simple game, a player i is a veto player if v(C) = 0 for any C ⊆ N{i} q n n v(C) {0, 1} for any C ⊆ N v is monotone: if v(C) = 1 and C ⊆ D, then v(D) = 1 equivalently, by monotonicity, v(N{i}) = 0 Traditionally, in simple games an outcome is identified with a payoff vector for N Theorem: a simple game has a non-empty core iff it has a veto player.

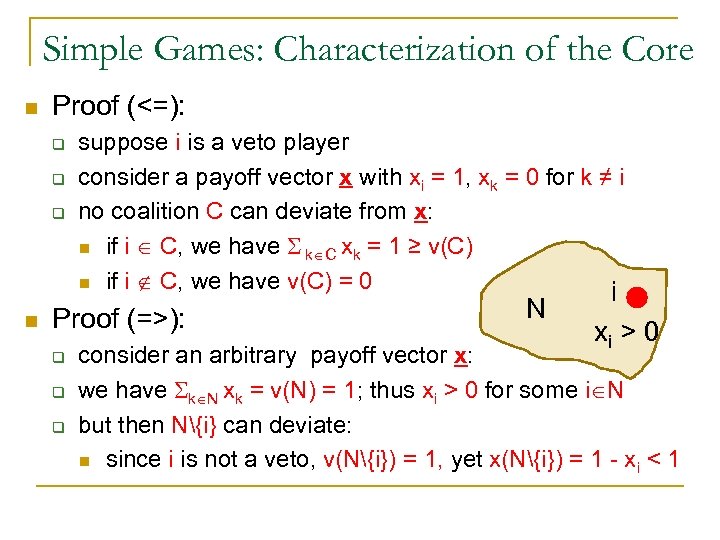

Simple Games: Characterization of the Core n Proof (<=): q q q n suppose i is a veto player consider a payoff vector x with xi = 1, xk = 0 for k ≠ i no coalition C can deviate from x: n if i C, we have S k C xk = 1 ≥ v(C) n if i C, we have v(C) = 0 Proof (=>): q q q N i xi > 0 consider an arbitrary payoff vector x: we have Sk N xk = v(N) = 1; thus xi > 0 for some i N but then N{i} can deviate: n since i is not a veto, v(N{i}) = 1, yet x(N{i}) = 1 - xi < 1

Simple Games: Characterization of the Core n Proof (<=): q q q n suppose i is a veto player consider a payoff vector x with xi = 1, xk = 0 for k ≠ i no coalition C can deviate from x: n if i C, we have S k C xk = 1 ≥ v(C) n if i C, we have v(C) = 0 Proof (=>): q q q N i xi > 0 consider an arbitrary payoff vector x: we have Sk N xk = v(N) = 1; thus xi > 0 for some i N but then N{i} can deviate: n since i is not a veto, v(N{i}) = 1, yet x(N{i}) = 1 - xi < 1

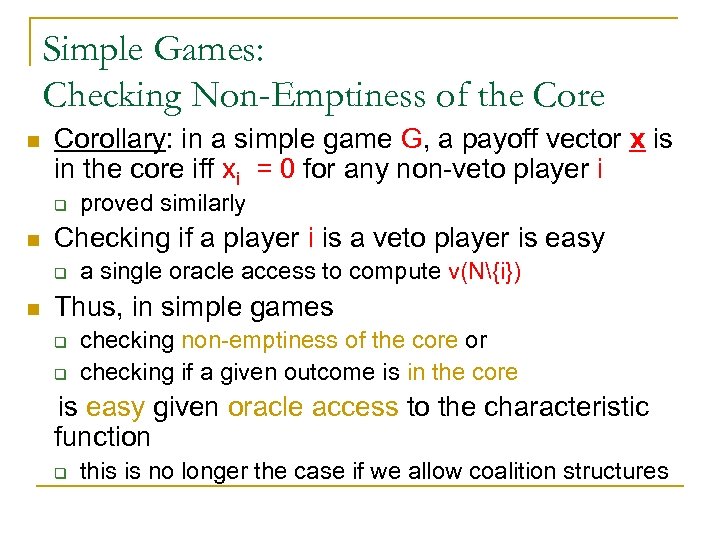

Simple Games: Checking Non-Emptiness of the Core n Corollary: in a simple game G, a payoff vector x is in the core iff xi = 0 for any non-veto player i q n Checking if a player i is a veto player is easy q n proved similarly a single oracle access to compute v(N{i}) Thus, in simple games q q checking non-emptiness of the core or checking if a given outcome is in the core is easy given oracle access to the characteristic function q this is no longer the case if we allow coalition structures

Simple Games: Checking Non-Emptiness of the Core n Corollary: in a simple game G, a payoff vector x is in the core iff xi = 0 for any non-veto player i q n Checking if a player i is a veto player is easy q n proved similarly a single oracle access to compute v(N{i}) Thus, in simple games q q checking non-emptiness of the core or checking if a given outcome is in the core is easy given oracle access to the characteristic function q this is no longer the case if we allow coalition structures

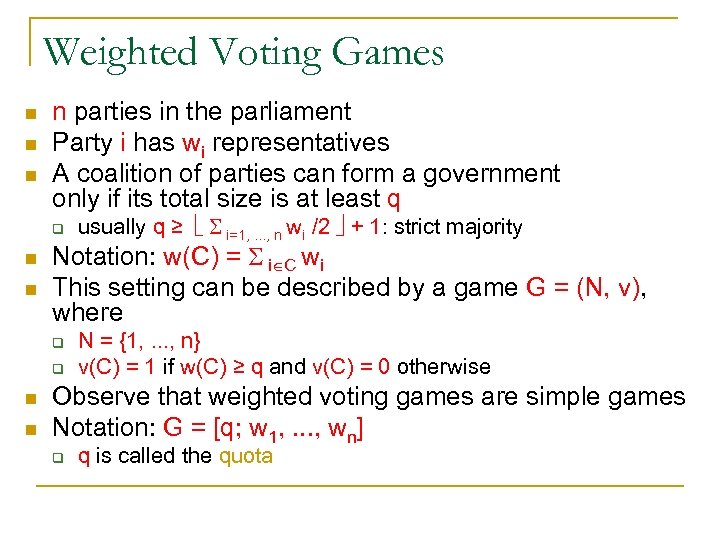

Weighted Voting Games n n parties in the parliament Party i has wi representatives A coalition of parties can form a government only if its total size is at least q q n n Notation: w(C) = S i C wi This setting can be described by a game G = (N, v), where q q n n usually q ≥ S i=1, . . . , n wi /2 + 1: strict majority N = {1, . . . , n} v(C) = 1 if w(C) ≥ q and v(C) = 0 otherwise Observe that weighted voting games are simple games Notation: G = [q; w 1, . . . , wn] q q is called the quota

Weighted Voting Games n n parties in the parliament Party i has wi representatives A coalition of parties can form a government only if its total size is at least q q n n Notation: w(C) = S i C wi This setting can be described by a game G = (N, v), where q q n n usually q ≥ S i=1, . . . , n wi /2 + 1: strict majority N = {1, . . . , n} v(C) = 1 if w(C) ≥ q and v(C) = 0 otherwise Observe that weighted voting games are simple games Notation: G = [q; w 1, . . . , wn] q q is called the quota

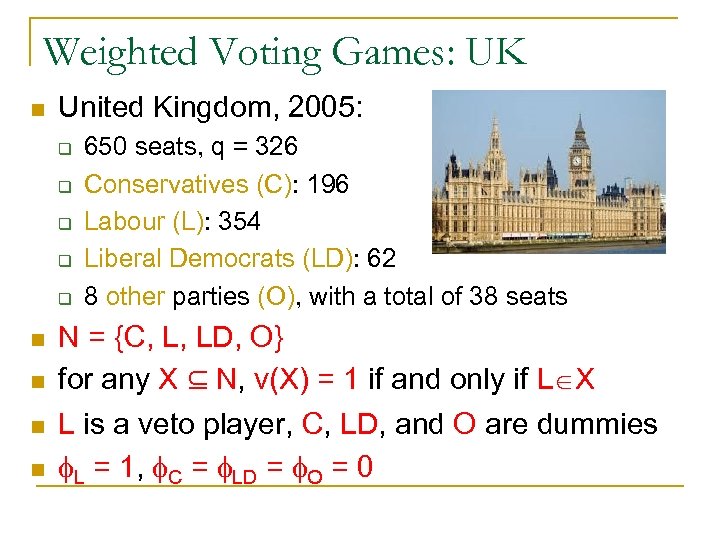

Weighted Voting Games: UK n United Kingdom, 2005: q q q n n 650 seats, q = 326 Conservatives (C): 196 Labour (L): 354 Liberal Democrats (LD): 62 8 other parties (O), with a total of 38 seats N = {C, L, LD, O} for any X ⊆ N, v(X) = 1 if and only if L X L is a veto player, C, LD, and O are dummies f. L = 1, f. C = f. LD = f. O = 0

Weighted Voting Games: UK n United Kingdom, 2005: q q q n n 650 seats, q = 326 Conservatives (C): 196 Labour (L): 354 Liberal Democrats (LD): 62 8 other parties (O), with a total of 38 seats N = {C, L, LD, O} for any X ⊆ N, v(X) = 1 if and only if L X L is a veto player, C, LD, and O are dummies f. L = 1, f. C = f. LD = f. O = 0

Weighted Voting Games: UK n United Kingdom, 2010: q q q n n n 650 seats, q = 326 Conservatives (C): 307 Labour (L): 258 Liberal Democrats (LD): 57 8 other parties (O), with a total of 28 seats N = {C, L, LD, O} v({C, L}) = v({C, LD}) = v({C, O}) = 1 v({L, LD}) = v({L, O}) = v({LD, O}) = 0, v({L, LD, O}) = 1 L, LD and O are symmetric f. C = 1/2, f. L = f. LD = f. O = 1/6

Weighted Voting Games: UK n United Kingdom, 2010: q q q n n n 650 seats, q = 326 Conservatives (C): 307 Labour (L): 258 Liberal Democrats (LD): 57 8 other parties (O), with a total of 28 seats N = {C, L, LD, O} v({C, L}) = v({C, LD}) = v({C, O}) = 1 v({L, LD}) = v({L, O}) = v({LD, O}) = 0, v({L, LD, O}) = 1 L, LD and O are symmetric f. C = 1/2, f. L = f. LD = f. O = 1/6

Weighted Voting Games as Resource Allocation Games n Each agent i has a certain amount of a resource wi q n n One or more tasks with a resource requirement q and a value V If a coalition has enough resources to complete the task (q or more units), it earns its value V, else it earns 0 q n time or money or battery power By normalization, can assume V = 1 If q < S i wi/2, grand coalition need not form q weighted voting games with coalition structures

Weighted Voting Games as Resource Allocation Games n Each agent i has a certain amount of a resource wi q n n One or more tasks with a resource requirement q and a value V If a coalition has enough resources to complete the task (q or more units), it earns its value V, else it earns 0 q n time or money or battery power By normalization, can assume V = 1 If q < S i wi/2, grand coalition need not form q weighted voting games with coalition structures

Shapley Value in Weighted Voting Games n In a simple game G = (N, v), a player i is said to be pivotal q q n In simple games player i’s Shapley value = Pr[i is pivotal for a random permutation] q n n for a coalition C ⊆ N if v(C) = 0, v(C U {i}) = 1 for a permutation p P(N) if he is pivotal for Sp(i) measure of voting power Shapley value is widely used to measure power in various voting bodies UK elections’ 10 illustrate that power ≠ weight

Shapley Value in Weighted Voting Games n In a simple game G = (N, v), a player i is said to be pivotal q q n In simple games player i’s Shapley value = Pr[i is pivotal for a random permutation] q n n for a coalition C ⊆ N if v(C) = 0, v(C U {i}) = 1 for a permutation p P(N) if he is pivotal for Sp(i) measure of voting power Shapley value is widely used to measure power in various voting bodies UK elections’ 10 illustrate that power ≠ weight

Shapley Value Paradoxes in Weighted Voting Games (1/2) n n Shapley value may sometimes behave in a counterintuitive way as the game changes Paradox of new members [Felsenthal and Machover’ 98]: when a new player joins, the power of an existing player may go up q q G = [4; 2, 2, 1]: player 3 is a dummy, so f 3 = 0 G = [4; 2, 2, 1, 1] (a new player of weight 1 joins): f 3 = 1/12

Shapley Value Paradoxes in Weighted Voting Games (1/2) n n Shapley value may sometimes behave in a counterintuitive way as the game changes Paradox of new members [Felsenthal and Machover’ 98]: when a new player joins, the power of an existing player may go up q q G = [4; 2, 2, 1]: player 3 is a dummy, so f 3 = 0 G = [4; 2, 2, 1, 1] (a new player of weight 1 joins): f 3 = 1/12

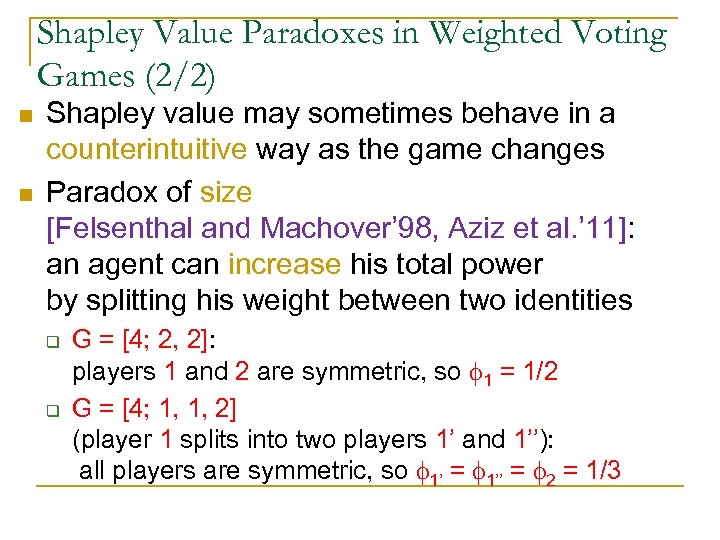

Shapley Value Paradoxes in Weighted Voting Games (2/2) n n Shapley value may sometimes behave in a counterintuitive way as the game changes Paradox of size [Felsenthal and Machover’ 98, Aziz et al. ’ 11]: an agent can increase his total power by splitting his weight between two identities q q G = [4; 2, 2]: players 1 and 2 are symmetric, so f 1 = 1/2 G = [4; 1, 1, 2] (player 1 splits into two players 1’ and 1’’): all players are symmetric, so f 1’ = f 1’’ = f 2 = 1/3

Shapley Value Paradoxes in Weighted Voting Games (2/2) n n Shapley value may sometimes behave in a counterintuitive way as the game changes Paradox of size [Felsenthal and Machover’ 98, Aziz et al. ’ 11]: an agent can increase his total power by splitting his weight between two identities q q G = [4; 2, 2]: players 1 and 2 are symmetric, so f 1 = 1/2 G = [4; 1, 1, 2] (player 1 splits into two players 1’ and 1’’): all players are symmetric, so f 1’ = f 1’’ = f 2 = 1/3

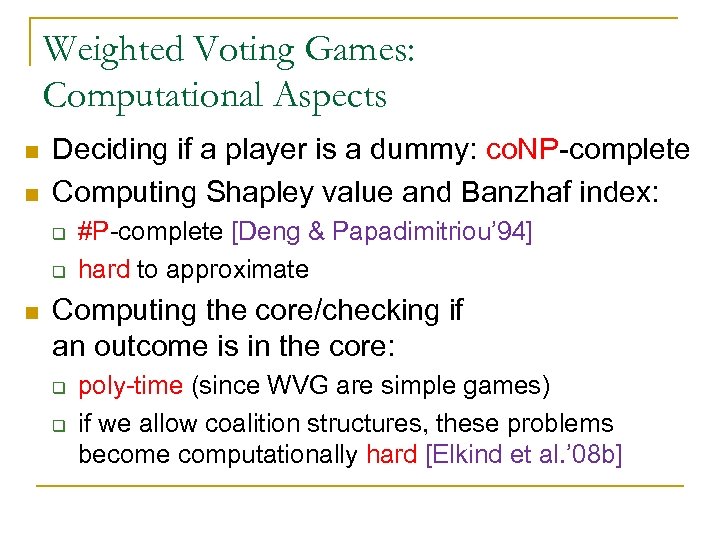

Weighted Voting Games: Computational Aspects n n Deciding if a player is a dummy: co. NP-complete Computing Shapley value and Banzhaf index: q q n #P-complete [Deng & Papadimitriou’ 94] hard to approximate Computing the core/checking if an outcome is in the core: q q poly-time (since WVG are simple games) if we allow coalition structures, these problems become computationally hard [Elkind et al. ’ 08 b]

Weighted Voting Games: Computational Aspects n n Deciding if a player is a dummy: co. NP-complete Computing Shapley value and Banzhaf index: q q n #P-complete [Deng & Papadimitriou’ 94] hard to approximate Computing the core/checking if an outcome is in the core: q q poly-time (since WVG are simple games) if we allow coalition structures, these problems become computationally hard [Elkind et al. ’ 08 b]

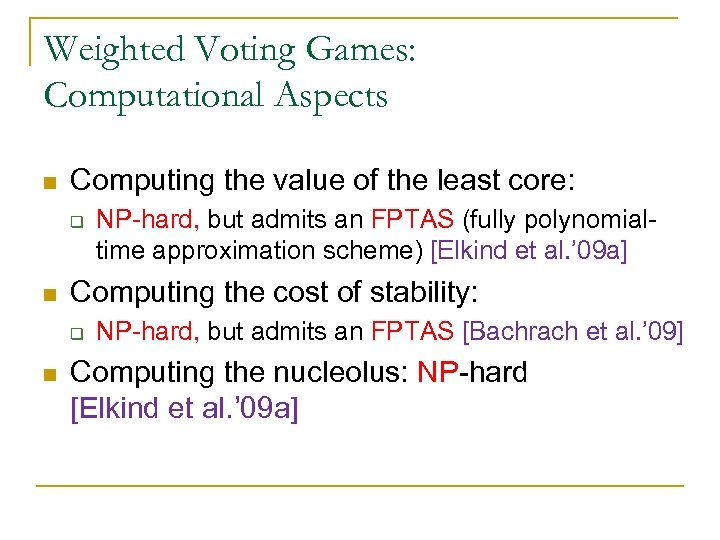

Weighted Voting Games: Computational Aspects n Computing the value of the least core: q n Computing the cost of stability: q n NP-hard, but admits an FPTAS (fully polynomialtime approximation scheme) [Elkind et al. ’ 09 a] NP-hard, but admits an FPTAS [Bachrach et al. ’ 09] Computing the nucleolus: NP-hard [Elkind et al. ’ 09 a]

Weighted Voting Games: Computational Aspects n Computing the value of the least core: q n Computing the cost of stability: q n NP-hard, but admits an FPTAS (fully polynomialtime approximation scheme) [Elkind et al. ’ 09 a] NP-hard, but admits an FPTAS [Bachrach et al. ’ 09] Computing the nucleolus: NP-hard [Elkind et al. ’ 09 a]

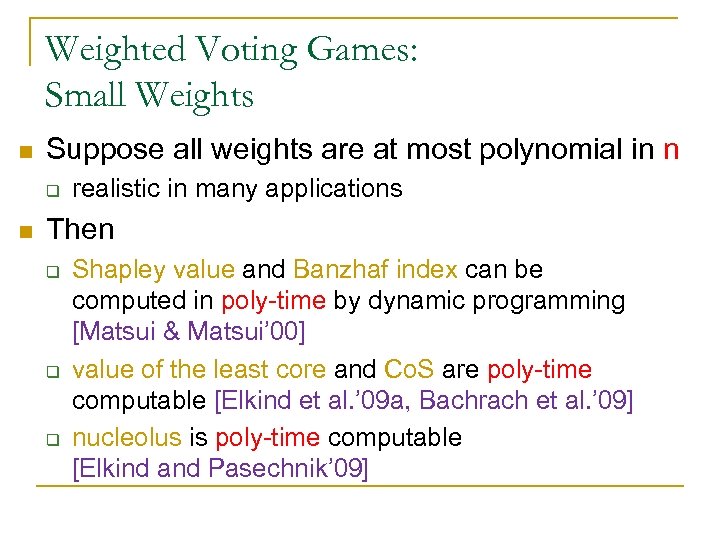

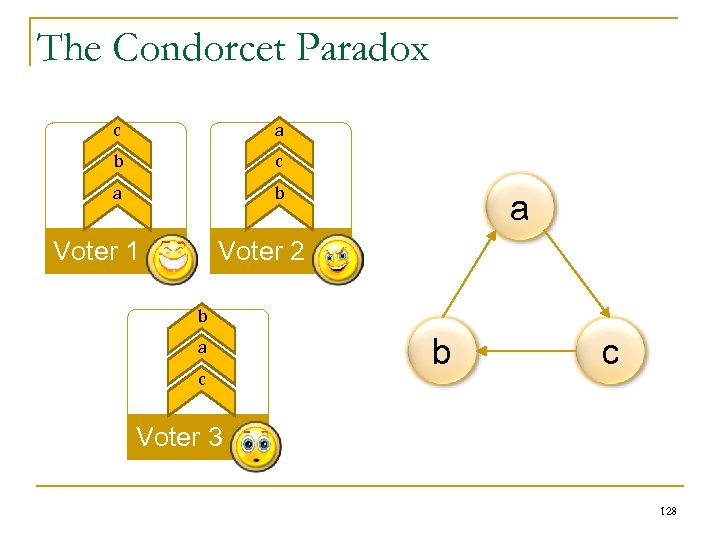

Weighted Voting Games: Small Weights n Suppose all weights are at most polynomial in n q n realistic in many applications Then q q q Shapley value and Banzhaf index can be computed in poly-time by dynamic programming [Matsui & Matsui’ 00] value of the least core and Co. S are poly-time computable [Elkind et al. ’ 09 a, Bachrach et al. ’ 09] nucleolus is poly-time computable [Elkind and Pasechnik’ 09]

Weighted Voting Games: Small Weights n Suppose all weights are at most polynomial in n q n realistic in many applications Then q q q Shapley value and Banzhaf index can be computed in poly-time by dynamic programming [Matsui & Matsui’ 00] value of the least core and Co. S are poly-time computable [Elkind et al. ’ 09 a, Bachrach et al. ’ 09] nucleolus is poly-time computable [Elkind and Pasechnik’ 09]

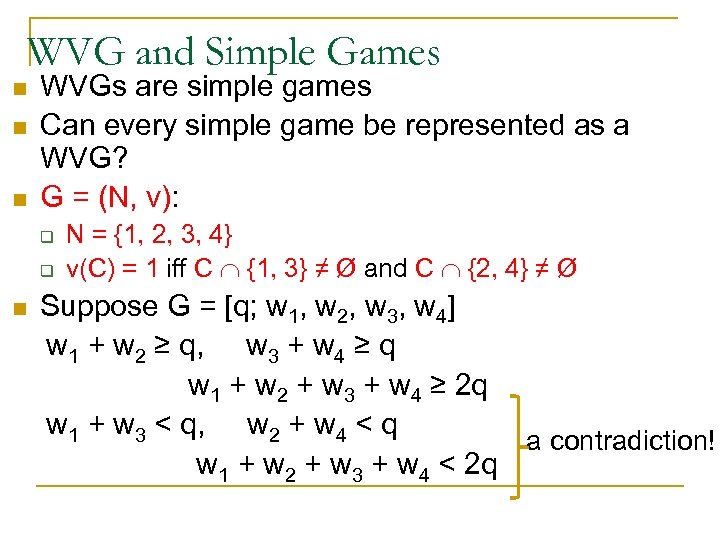

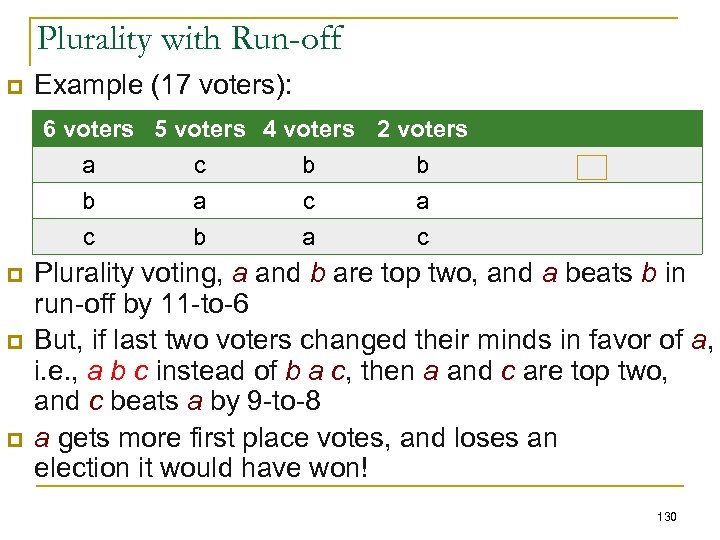

WVG and Simple Games n n n WVGs are simple games Can every simple game be represented as a WVG? G = (N, v): q q n N = {1, 2, 3, 4} v(C) = 1 iff C {1, 3} ≠ Ø and C {2, 4} ≠ Ø Suppose G = [q; w 1, w 2, w 3, w 4] w 1 + w 2 ≥ q, w 3 + w 4 ≥ q w 1 + w 2 + w 3 + w 4 ≥ 2 q w 1 + w 3 < q, w 2 + w 4 < q a contradiction! w 1 + w 2 + w 3 + w 4 < 2 q

WVG and Simple Games n n n WVGs are simple games Can every simple game be represented as a WVG? G = (N, v): q q n N = {1, 2, 3, 4} v(C) = 1 iff C {1, 3} ≠ Ø and C {2, 4} ≠ Ø Suppose G = [q; w 1, w 2, w 3, w 4] w 1 + w 2 ≥ q, w 3 + w 4 ≥ q w 1 + w 2 + w 3 + w 4 ≥ 2 q w 1 + w 3 < q, w 2 + w 4 < q a contradiction! w 1 + w 2 + w 3 + w 4 < 2 q

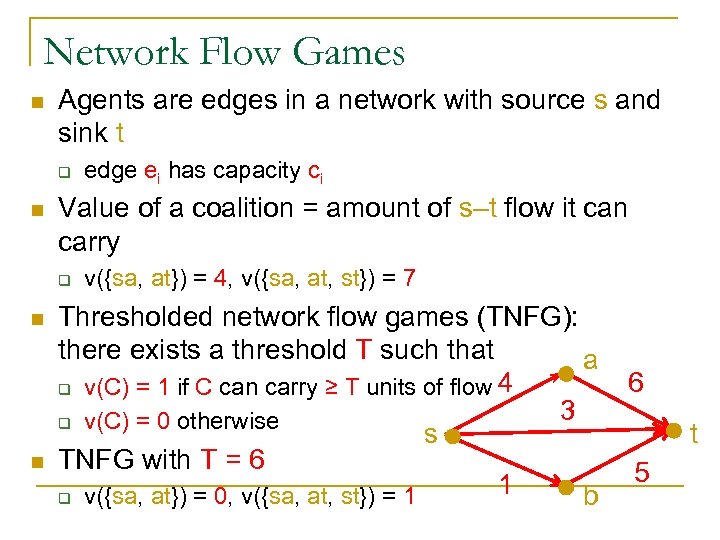

Network Flow Games n Agents are edges in a network with source s and sink t q n Value of a coalition = amount of s–t flow it can carry q n n edge ei has capacity ci v({sa, at}) = 4, v({sa, at, st}) = 7 Thresholded network flow games (TNFG): there exists a threshold T such that a q v(C) = 1 if C can carry ≥ T units of flow 4 3 q v(C) = 0 otherwise s TNFG with T = 6 1 q v({sa, at}) = 0, v({sa, at, st}) = 1 b 6 t 5

Network Flow Games n Agents are edges in a network with source s and sink t q n Value of a coalition = amount of s–t flow it can carry q n n edge ei has capacity ci v({sa, at}) = 4, v({sa, at, st}) = 7 Thresholded network flow games (TNFG): there exists a threshold T such that a q v(C) = 1 if C can carry ≥ T units of flow 4 3 q v(C) = 0 otherwise s TNFG with T = 6 1 q v({sa, at}) = 0, v({sa, at, st}) = 1 b 6 t 5

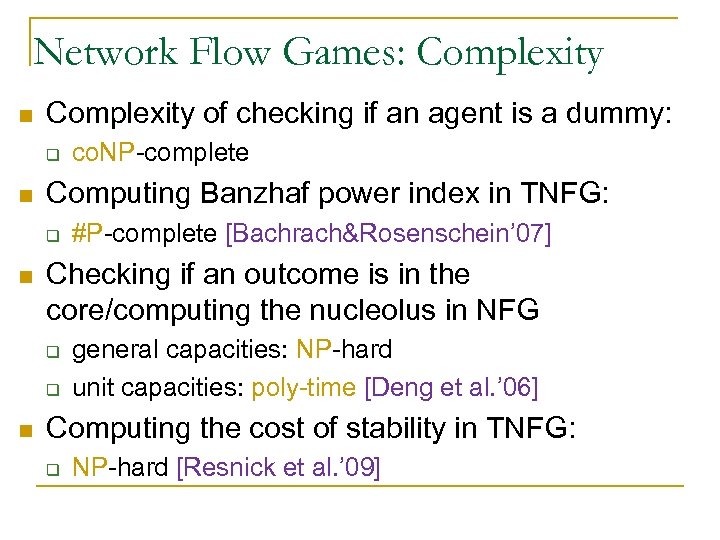

Network Flow Games: Complexity n Complexity of checking if an agent is a dummy: q n Computing Banzhaf power index in TNFG: q n #P-complete [Bachrach&Rosenschein’ 07] Checking if an outcome is in the core/computing the nucleolus in NFG q q n co. NP-complete general capacities: NP-hard unit capacities: poly-time [Deng et al. ’ 06] Computing the cost of stability in TNFG: q NP-hard [Resnick et al. ’ 09]

Network Flow Games: Complexity n Complexity of checking if an agent is a dummy: q n Computing Banzhaf power index in TNFG: q n #P-complete [Bachrach&Rosenschein’ 07] Checking if an outcome is in the core/computing the nucleolus in NFG q q n co. NP-complete general capacities: NP-hard unit capacities: poly-time [Deng et al. ’ 06] Computing the cost of stability in TNFG: q NP-hard [Resnick et al. ’ 09]

![Coalitional Skill Games [Bachrach&Rosenschein’ 08] n n n Set of skills S = {s Coalitional Skill Games [Bachrach&Rosenschein’ 08] n n n Set of skills S = {s](https://present5.com/presentation/20c3b715d39698e631a9077988855a69/image-68.jpg) Coalitional Skill Games [Bachrach&Rosenschein’ 08] n n n Set of skills S = {s 1, . . . , sk} Set of agents N: agent i has a subset of skills Si ⊆ S Set of tasks T = {t 1, . . . , tm} q n n n A skill set of a coalition C: s(C) = U i C Si Tasks that C can perform: T(C) = {tj | S(tj) ⊆ S(C)} Utility function u : 2 T → R q n each task tj requires a subset of skills S(tj) ⊆ S e. g. , sum or max of values of individual tasks Characteristic function: v(C) = u(T(C))

Coalitional Skill Games [Bachrach&Rosenschein’ 08] n n n Set of skills S = {s 1, . . . , sk} Set of agents N: agent i has a subset of skills Si ⊆ S Set of tasks T = {t 1, . . . , tm} q n n n A skill set of a coalition C: s(C) = U i C Si Tasks that C can perform: T(C) = {tj | S(tj) ⊆ S(C)} Utility function u : 2 T → R q n each task tj requires a subset of skills S(tj) ⊆ S e. g. , sum or max of values of individual tasks Characteristic function: v(C) = u(T(C))

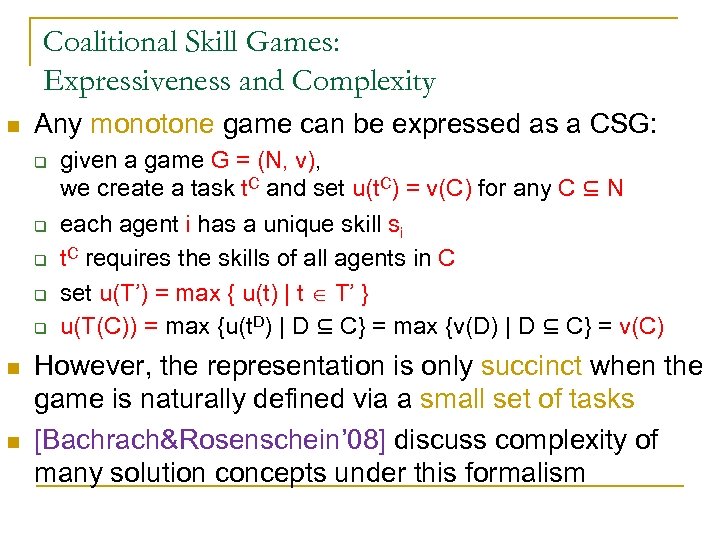

Coalitional Skill Games: Expressiveness and Complexity n Any monotone game can be expressed as a CSG: q q q n n given a game G = (N, v), we create a task t. C and set u(t. C) = v(C) for any C ⊆ N each agent i has a unique skill si t. C requires the skills of all agents in C set u(T’) = max { u(t) | t T’ } u(T(C)) = max {u(t. D) | D ⊆ C} = max {v(D) | D ⊆ C} = v(C) However, the representation is only succinct when the game is naturally defined via a small set of tasks [Bachrach&Rosenschein’ 08] discuss complexity of many solution concepts under this formalism

Coalitional Skill Games: Expressiveness and Complexity n Any monotone game can be expressed as a CSG: q q q n n given a game G = (N, v), we create a task t. C and set u(t. C) = v(C) for any C ⊆ N each agent i has a unique skill si t. C requires the skills of all agents in C set u(T’) = max { u(t) | t T’ } u(T(C)) = max {u(t. D) | D ⊆ C} = max {v(D) | D ⊆ C} = v(C) However, the representation is only succinct when the game is naturally defined via a small set of tasks [Bachrach&Rosenschein’ 08] discuss complexity of many solution concepts under this formalism

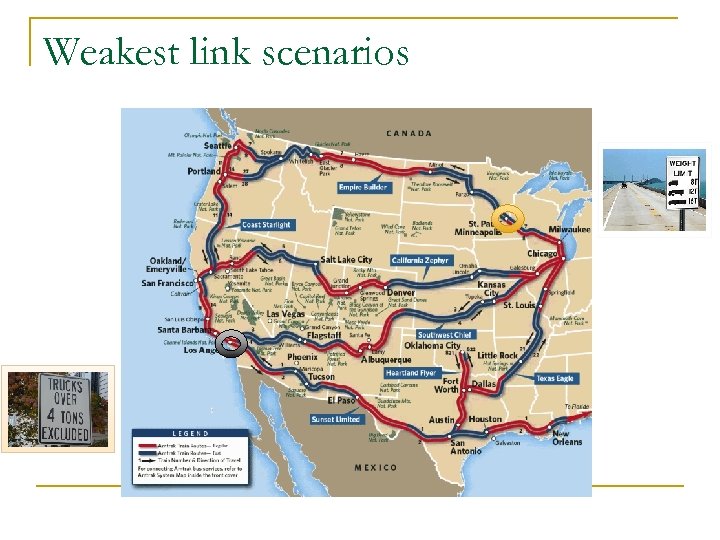

Weakest link scenarios

Weakest link scenarios

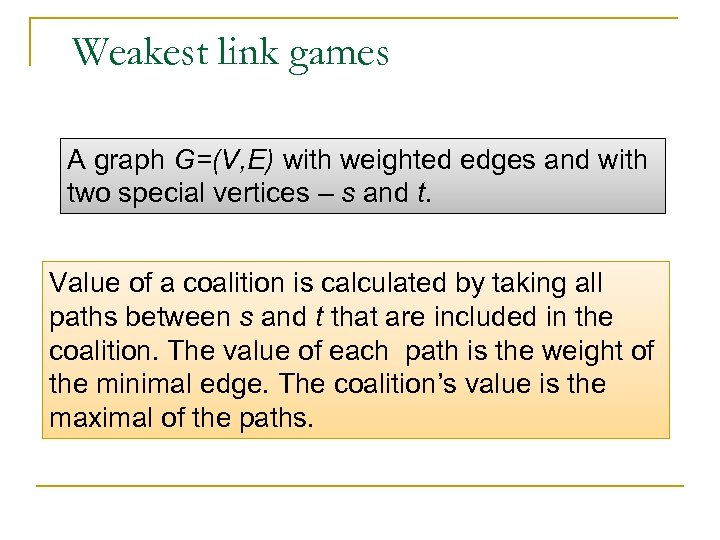

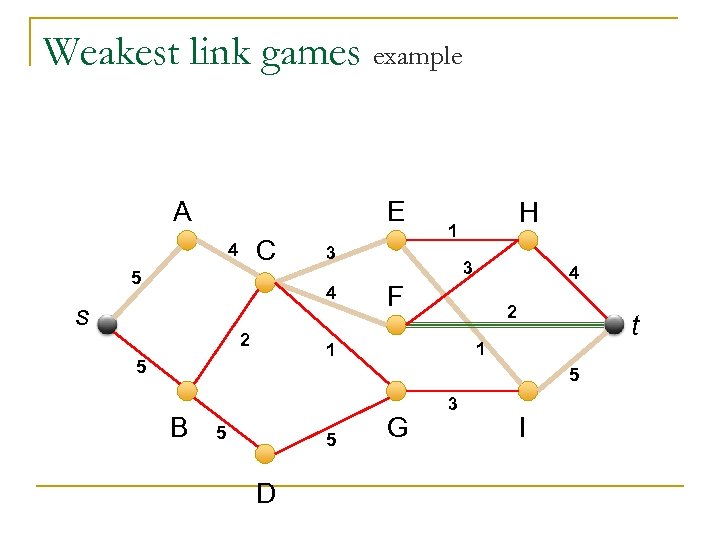

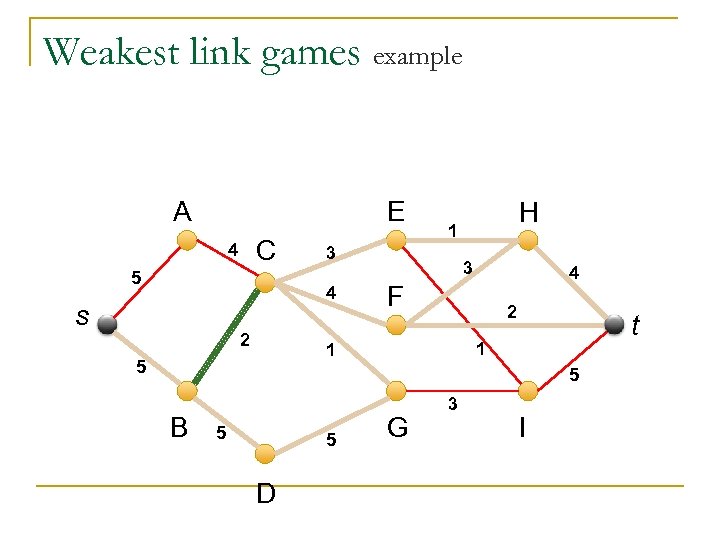

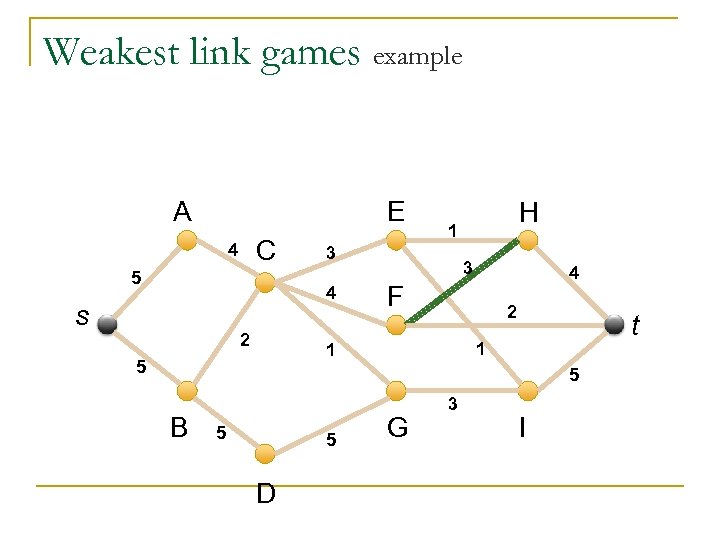

Weakest link games A graph G=(V, E) with weighted edges and with two special vertices – s and t. Value of a coalition is calculated by taking all paths between s and t that are included in the coalition. The value of each path is the weight of the minimal edge. The coalition’s value is the maximal of the paths.

Weakest link games A graph G=(V, E) with weighted edges and with two special vertices – s and t. Value of a coalition is calculated by taking all paths between s and t that are included in the coalition. The value of each path is the weight of the minimal edge. The coalition’s value is the maximal of the paths.

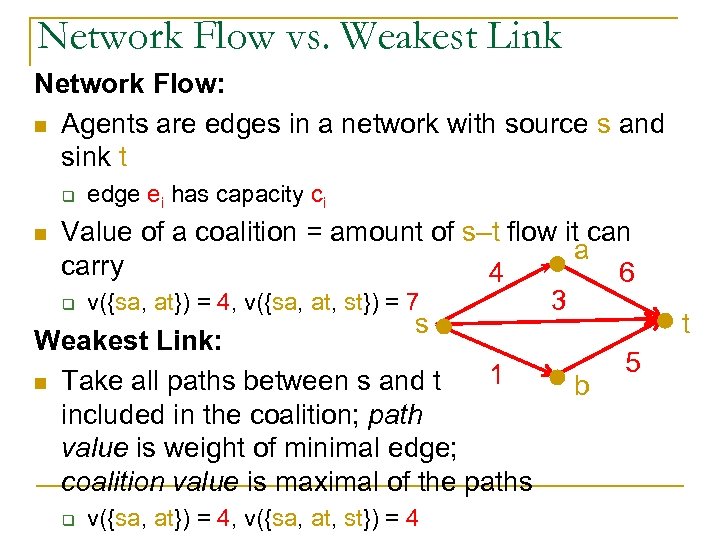

Network Flow vs. Weakest Link Network Flow: n Agents are edges in a network with source s and sink t q edge ei has capacity ci Value of a coalition = amount of s–t flow it can a carry 4 6 3 q v({sa, at}) = 4, v({sa, at, st}) = 7 s Weakest Link: 5 1 n Take all paths between s and t b included in the coalition; path value is weight of minimal edge; coalition value is maximal of the paths n q v({sa, at}) = 4, v({sa, at, st}) = 4 t

Network Flow vs. Weakest Link Network Flow: n Agents are edges in a network with source s and sink t q edge ei has capacity ci Value of a coalition = amount of s–t flow it can a carry 4 6 3 q v({sa, at}) = 4, v({sa, at, st}) = 7 s Weakest Link: 5 1 n Take all paths between s and t b included in the coalition; path value is weight of minimal edge; coalition value is maximal of the paths n q v({sa, at}) = 4, v({sa, at, st}) = 4 t

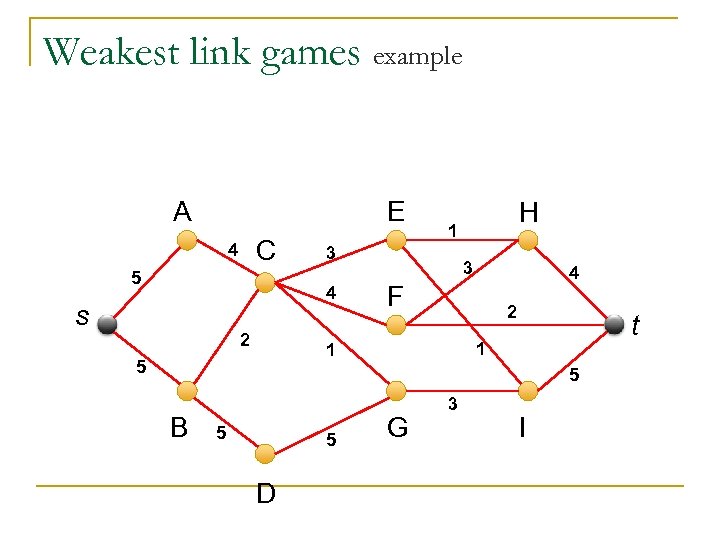

Weakest link games example A E C 4 5 s 2 1 3 4 F 2 t 1 1 5 H 5 B 5 5 D G 3 I

Weakest link games example A E C 4 5 s 2 1 3 4 F 2 t 1 1 5 H 5 B 5 5 D G 3 I

Weakest link games example A E C 4 5 s 2 1 3 4 F 2 t 1 1 5 H 5 B 5 5 D G 3 I

Weakest link games example A E C 4 5 s 2 1 3 4 F 2 t 1 1 5 H 5 B 5 5 D G 3 I

Weakest link games example A E C 4 5 s 2 1 3 4 F 2 t 1 1 5 H 5 B 5 5 D G 3 I

Weakest link games example A E C 4 5 s 2 1 3 4 F 2 t 1 1 5 H 5 B 5 5 D G 3 I

Weakest link games example A E C 4 5 s 2 1 3 4 F 2 t 1 1 5 H 5 B 5 5 D G 3 I

Weakest link games example A E C 4 5 s 2 1 3 4 F 2 t 1 1 5 H 5 B 5 5 D G 3 I

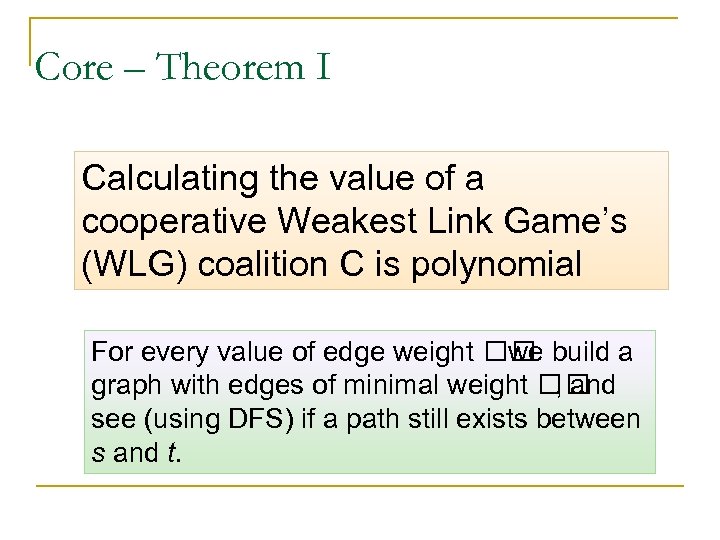

Core – Theorem I Calculating the value of a cooperative Weakest Link Game’s (WLG) coalition C is polynomial For every value of edge weight build a we graph with edges of minimal weight , and see (using DFS) if a path still exists between s and t.

Core – Theorem I Calculating the value of a cooperative Weakest Link Game’s (WLG) coalition C is polynomial For every value of edge weight build a we graph with edges of minimal weight , and see (using DFS) if a path still exists between s and t.

Core – Theorem II Testing if an imputation is in the core (or -core) of a WLG is polynomial For every value of edge weight build a we graph with edges of minimal weight , and modify the weight of each edge to be its imputation. We find the shortest path, and if its total weight is below have a , we blocking coalition.

Core – Theorem II Testing if an imputation is in the core (or -core) of a WLG is polynomial For every value of edge weight build a we graph with edges of minimal weight , and modify the weight of each edge to be its imputation. We find the shortest path, and if its total weight is below have a , we blocking coalition.

Core – Theorem III Emptiness of core (or -core) of a WLG is polynomial

Core – Theorem III Emptiness of core (or -core) of a WLG is polynomial

Representation 3: Marginal Contribution Nets (Ieong & Shoham, 2005) n Characteristic function represented as rules: pattern → value 7 -80

Representation 3: Marginal Contribution Nets (Ieong & Shoham, 2005) n Characteristic function represented as rules: pattern → value 7 -80

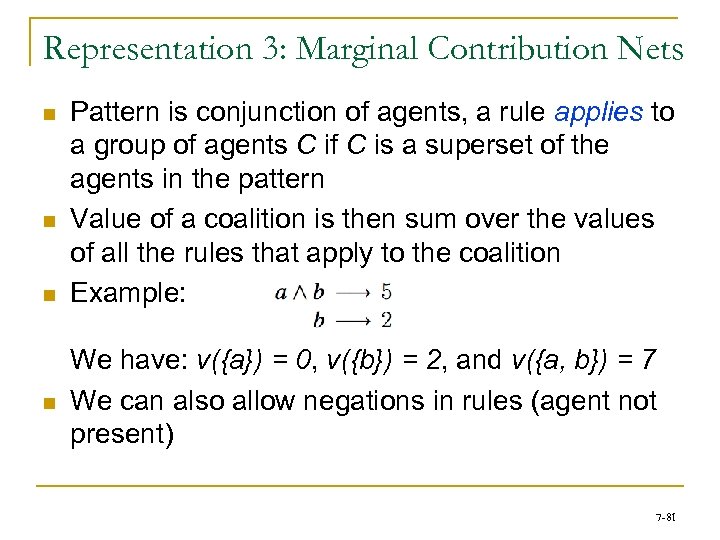

Representation 3: Marginal Contribution Nets n n Pattern is conjunction of agents, a rule applies to a group of agents C if C is a superset of the agents in the pattern Value of a coalition is then sum over the values of all the rules that apply to the coalition Example: We have: ν({a}) = 0, ν({b}) = 2, and ν({a, b}) = 7 We can also allow negations in rules (agent not present) 7 -81

Representation 3: Marginal Contribution Nets n n Pattern is conjunction of agents, a rule applies to a group of agents C if C is a superset of the agents in the pattern Value of a coalition is then sum over the values of all the rules that apply to the coalition Example: We have: ν({a}) = 0, ν({b}) = 2, and ν({a, b}) = 7 We can also allow negations in rules (agent not present) 7 -81

Representation 3: Marginal Contribution Nets n n Shapley value: in polynomial time Checking whether distribution is in the core: co-NP-complete Checking whether the core is non-empty: co-NP-hard. A complete representation, but not necessarily succinct 7 -82

Representation 3: Marginal Contribution Nets n n Shapley value: in polynomial time Checking whether distribution is in the core: co-NP-complete Checking whether the core is non-empty: co-NP-hard. A complete representation, but not necessarily succinct 7 -82

Voting Power Assume that there is a body voting “yes” or “no” on a law. How much voting power does each member have? Example: Four member body, A, B, C, D. If there is a tie, A (the chairman) gets to break the tie. How much extra voting power does A have? 83

Voting Power Assume that there is a body voting “yes” or “no” on a law. How much voting power does each member have? Example: Four member body, A, B, C, D. If there is a tie, A (the chairman) gets to break the tie. How much extra voting power does A have? 83

Shapley-Shubik Index Shapley-Shubik index: Assume all orderings are possible, see when each member is pivotal (i. e. , the losing coalition becomes the winning coalition when that member joins it). The pivotal member holds the power. Arrange the members in order of their enthusiasm for the bill. We don’t know what members’ preferences are, so assume a priori that any order is equally likely (big assumption in the real world). 84

Shapley-Shubik Index Shapley-Shubik index: Assume all orderings are possible, see when each member is pivotal (i. e. , the losing coalition becomes the winning coalition when that member joins it). The pivotal member holds the power. Arrange the members in order of their enthusiasm for the bill. We don’t know what members’ preferences are, so assume a priori that any order is equally likely (big assumption in the real world). 84

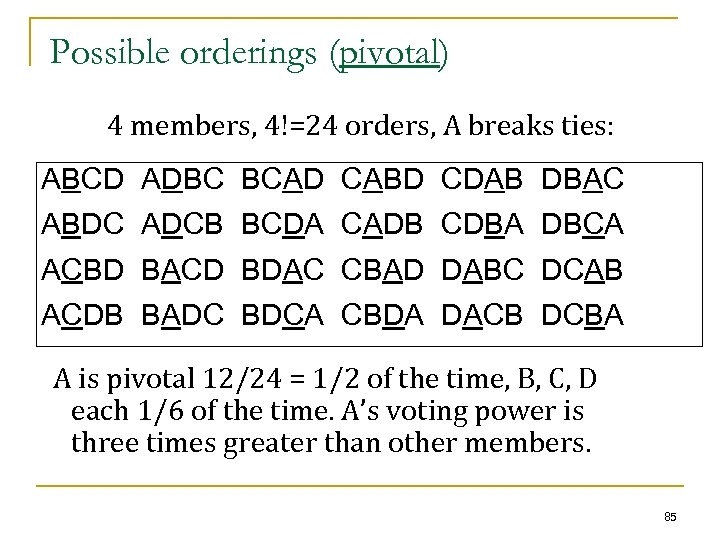

Possible orderings (pivotal) 4 members, 4!=24 orders, A breaks ties: ABCD ADBC BCAD CABD CDAB DBAC ABDC ADCB BCDA CADB CDBA DBCA ACBD BACD BDAC CBAD DABC DCAB ACDB BADC BDCA CBDA DACB DCBA A is pivotal 12/24 = 1/2 of the time, B, C, D each 1/6 of the time. A’s voting power is three times greater than other members. 85

Possible orderings (pivotal) 4 members, 4!=24 orders, A breaks ties: ABCD ADBC BCAD CABD CDAB DBAC ABDC ADCB BCDA CADB CDBA DBCA ACBD BACD BDAC CBAD DABC DCAB ACDB BADC BDCA CBDA DACB DCBA A is pivotal 12/24 = 1/2 of the time, B, C, D each 1/6 of the time. A’s voting power is three times greater than other members. 85

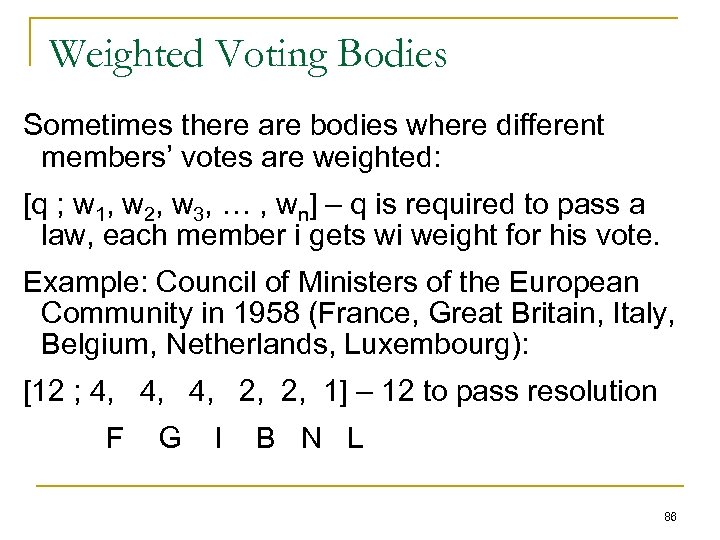

Weighted Voting Bodies Sometimes there are bodies where different members’ votes are weighted: [q ; w 1, w 2, w 3, … , wn] – q is required to pass a law, each member i gets wi weight for his vote. Example: Council of Ministers of the European Community in 1958 (France, Great Britain, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg): [12 ; 4, 4, 4, 2, 2, 1] – 12 to pass resolution F G I B N L 86

Weighted Voting Bodies Sometimes there are bodies where different members’ votes are weighted: [q ; w 1, w 2, w 3, … , wn] – q is required to pass a law, each member i gets wi weight for his vote. Example: Council of Ministers of the European Community in 1958 (France, Great Britain, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg): [12 ; 4, 4, 4, 2, 2, 1] – 12 to pass resolution F G I B N L 86

![60 different ways to arrange 4, 4, 4, 2, 2, 1 [6!/(3!2!1!)]. A “ 60 different ways to arrange 4, 4, 4, 2, 2, 1 [6!/(3!2!1!)]. A “](https://present5.com/presentation/20c3b715d39698e631a9077988855a69/image-87.jpg) 60 different ways to arrange 4, 4, 4, 2, 2, 1 [6!/(3!2!1!)]. A “ 4” occupies the pivotal position in 42 orders, a “ 2” occupies the pivotal position in 18 orders, and a “ 1” never occupies the pivotal position. Shapley-Shubik index: ( 14/60, 9/60, 0) F G I B N L % votes % power France, Germany, Italy 23. 5% 23. 3% Belgium, Netherlands 11. 8% 15. 0% Luxembourg 5. 9% 0. 0. % Luxembourg is a “dummy. ” 87

60 different ways to arrange 4, 4, 4, 2, 2, 1 [6!/(3!2!1!)]. A “ 4” occupies the pivotal position in 42 orders, a “ 2” occupies the pivotal position in 18 orders, and a “ 1” never occupies the pivotal position. Shapley-Shubik index: ( 14/60, 9/60, 0) F G I B N L % votes % power France, Germany, Italy 23. 5% 23. 3% Belgium, Netherlands 11. 8% 15. 0% Luxembourg 5. 9% 0. 0. % Luxembourg is a “dummy. ” 87

![Another example (no dummy) [5 ; 2, 2, 1, 1] (A, B, C, D) Another example (no dummy) [5 ; 2, 2, 1, 1] (A, B, C, D)](https://present5.com/presentation/20c3b715d39698e631a9077988855a69/image-88.jpg) Another example (no dummy) [5 ; 2, 2, 1, 1] (A, B, C, D) Six possible orders: 2211 2121 2112 1221 1212 1122 A “ 2” pivots in five of them, so power indices are: (5/12, 1/12, 1/12) [Voting bodies with same winning coalitions are “structurally equivalent”; e. g. , body with dummy equivalent to same body without the dummy. ] 88

Another example (no dummy) [5 ; 2, 2, 1, 1] (A, B, C, D) Six possible orders: 2211 2121 2112 1221 1212 1122 A “ 2” pivots in five of them, so power indices are: (5/12, 1/12, 1/12) [Voting bodies with same winning coalitions are “structurally equivalent”; e. g. , body with dummy equivalent to same body without the dummy. ] 88

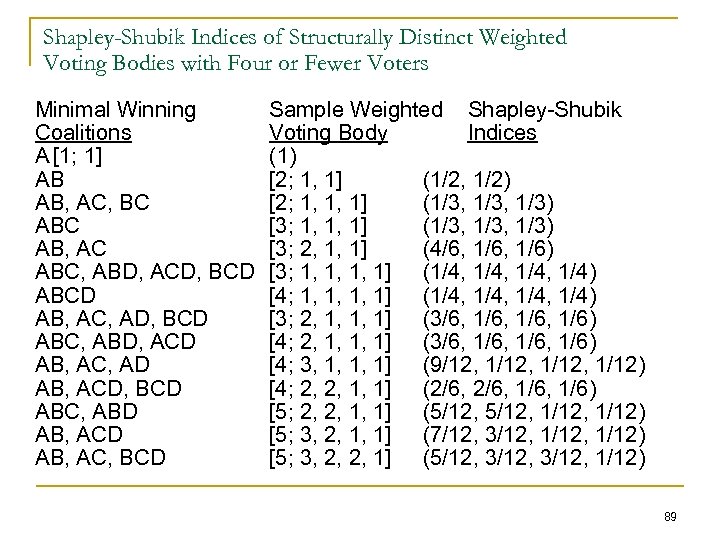

Shapley-Shubik Indices of Structurally Distinct Weighted Voting Bodies with Four or Fewer Voters Minimal Winning Coalitions A [1; 1] AB AB, AC, BC AB, AC ABC, ABD, ACD, BCD AB, AC, AD, BCD ABC, ABD, ACD AB, AC, AD AB, ACD, BCD ABC, ABD AB, AC, BCD Sample Weighted Shapley-Shubik Voting Body Indices (1) [2; 1, 1] (1/2, 1/2) [2; 1, 1, 1] (1/3, 1/3) [3; 2, 1, 1] (4/6, 1/6) [3; 1, 1, 1, 1] (1/4, 1/4) [4; 1, 1, 1, 1] (1/4, 1/4) [3; 2, 1, 1, 1] (3/6, 1/6, 1/6) [4; 3, 1, 1, 1] (9/12, 1/12, 1/12) [4; 2, 2, 1, 1] (2/6, 1/6, 1/6) [5; 2, 2, 1, 1] (5/12, 1/12, 1/12) [5; 3, 2, 1, 1] (7/12, 3/12, 1/12) [5; 3, 2, 2, 1] (5/12, 3/12, 1/12) 89

Shapley-Shubik Indices of Structurally Distinct Weighted Voting Bodies with Four or Fewer Voters Minimal Winning Coalitions A [1; 1] AB AB, AC, BC AB, AC ABC, ABD, ACD, BCD AB, AC, AD, BCD ABC, ABD, ACD AB, AC, AD AB, ACD, BCD ABC, ABD AB, AC, BCD Sample Weighted Shapley-Shubik Voting Body Indices (1) [2; 1, 1] (1/2, 1/2) [2; 1, 1, 1] (1/3, 1/3) [3; 2, 1, 1] (4/6, 1/6) [3; 1, 1, 1, 1] (1/4, 1/4) [4; 1, 1, 1, 1] (1/4, 1/4) [3; 2, 1, 1, 1] (3/6, 1/6, 1/6) [4; 3, 1, 1, 1] (9/12, 1/12, 1/12) [4; 2, 2, 1, 1] (2/6, 1/6, 1/6) [5; 2, 2, 1, 1] (5/12, 1/12, 1/12) [5; 3, 2, 1, 1] (7/12, 3/12, 1/12) [5; 3, 2, 2, 1] (5/12, 3/12, 1/12) 89

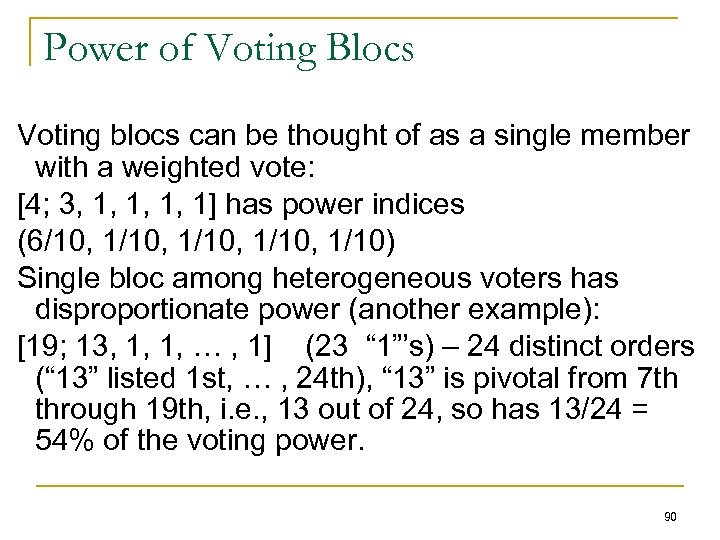

Power of Voting Blocs Voting blocs can be thought of as a single member with a weighted vote: [4; 3, 1, 1] has power indices (6/10, 1/10, 1/10) Single bloc among heterogeneous voters has disproportionate power (another example): [19; 13, 1, 1, … , 1] (23 “ 1”’s) – 24 distinct orders (“ 13” listed 1 st, … , 24 th), “ 13” is pivotal from 7 th through 19 th, i. e. , 13 out of 24, so has 13/24 = 54% of the voting power. 90

Power of Voting Blocs Voting blocs can be thought of as a single member with a weighted vote: [4; 3, 1, 1] has power indices (6/10, 1/10, 1/10) Single bloc among heterogeneous voters has disproportionate power (another example): [19; 13, 1, 1, … , 1] (23 “ 1”’s) – 24 distinct orders (“ 13” listed 1 st, … , 24 th), “ 13” is pivotal from 7 th through 19 th, i. e. , 13 out of 24, so has 13/24 = 54% of the voting power. 90

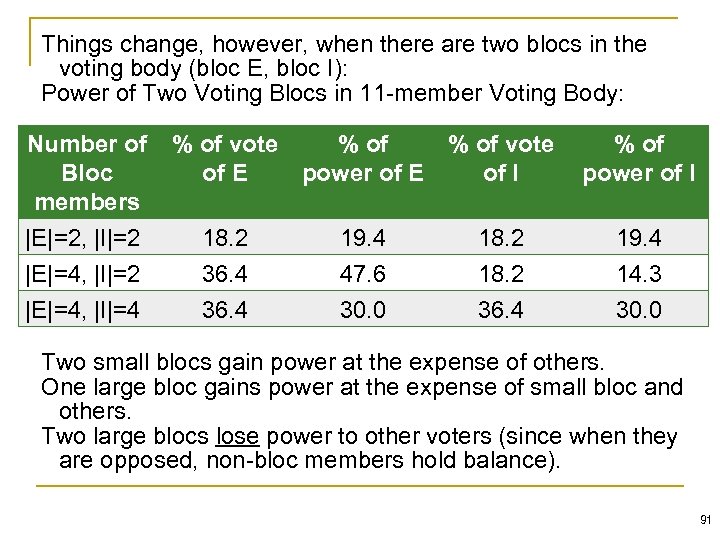

Things change, however, when there are two blocs in the voting body (bloc E, bloc I): Power of Two Voting Blocs in 11 -member Voting Body: Number of Bloc members % of vote of E power of E of I % of power of I |E|=2, |I|=2 18. 2 19. 4 |E|=4, |I|=2 36. 4 47. 6 18. 2 14. 3 |E|=4, |I|=4 36. 4 30. 0 Two small blocs gain power at the expense of others. One large bloc gains power at the expense of small bloc and others. Two large blocs lose power to other voters (since when they are opposed, non-bloc members hold balance). 91

Things change, however, when there are two blocs in the voting body (bloc E, bloc I): Power of Two Voting Blocs in 11 -member Voting Body: Number of Bloc members % of vote of E power of E of I % of power of I |E|=2, |I|=2 18. 2 19. 4 |E|=4, |I|=2 36. 4 47. 6 18. 2 14. 3 |E|=4, |I|=4 36. 4 30. 0 Two small blocs gain power at the expense of others. One large bloc gains power at the expense of small bloc and others. Two large blocs lose power to other voters (since when they are opposed, non-bloc members hold balance). 91

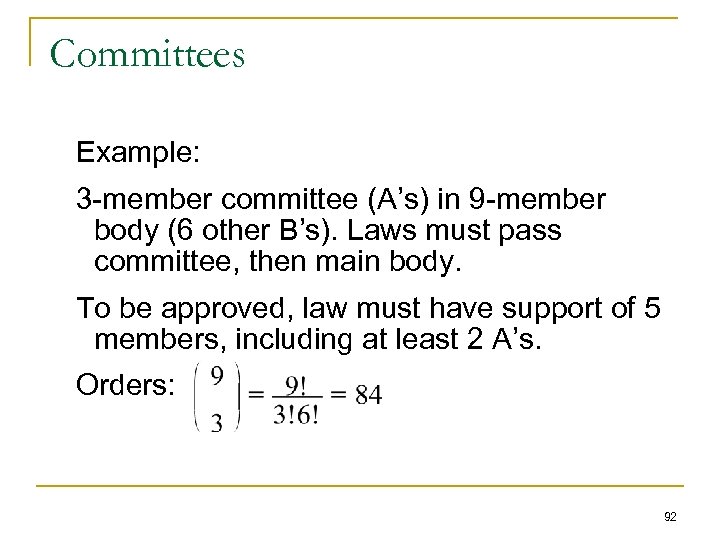

Committees Example: 3 -member committee (A’s) in 9 -member body (6 other B’s). Laws must pass committee, then main body. To be approved, law must have support of 5 members, including at least 2 A’s. Orders: 92

Committees Example: 3 -member committee (A’s) in 9 -member body (6 other B’s). Laws must pass committee, then main body. To be approved, law must have support of 5 members, including at least 2 A’s. Orders: 92

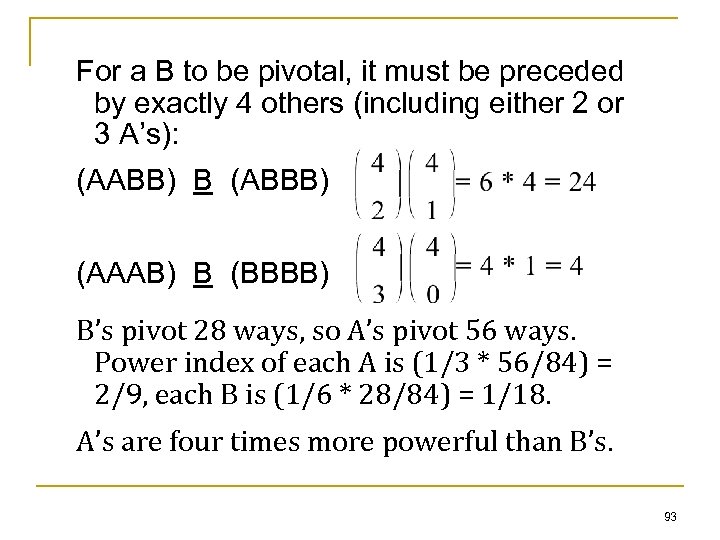

For a B to be pivotal, it must be preceded by exactly 4 others (including either 2 or 3 A’s): (AABB) B (ABBB) (AAAB) B (BBBB) B’s pivot 28 ways, so A’s pivot 56 ways. Power index of each A is (1/3 * 56/84) = 2/9, each B is (1/6 * 28/84) = 1/18. A’s are four times more powerful than B’s. 93

For a B to be pivotal, it must be preceded by exactly 4 others (including either 2 or 3 A’s): (AABB) B (ABBB) (AAAB) B (BBBB) B’s pivot 28 ways, so A’s pivot 56 ways. Power index of each A is (1/3 * 56/84) = 2/9, each B is (1/6 * 28/84) = 1/18. A’s are four times more powerful than B’s. 93

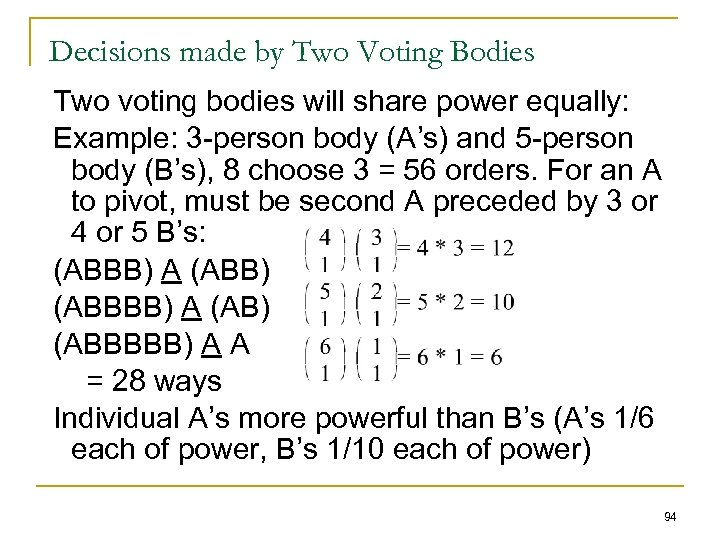

Decisions made by Two Voting Bodies Two voting bodies will share power equally: Example: 3 -person body (A’s) and 5 -person body (B’s), 8 choose 3 = 56 orders. For an A to pivot, must be second A preceded by 3 or 4 or 5 B’s: (ABBB) A (ABB) (ABBBB) A (AB) (ABBBBB) A A = 28 ways Individual A’s more powerful than B’s (A’s 1/6 each of power, B’s 1/10 each of power) 94

Decisions made by Two Voting Bodies Two voting bodies will share power equally: Example: 3 -person body (A’s) and 5 -person body (B’s), 8 choose 3 = 56 orders. For an A to pivot, must be second A preceded by 3 or 4 or 5 B’s: (ABBB) A (ABB) (ABBBB) A (AB) (ABBBBB) A A = 28 ways Individual A’s more powerful than B’s (A’s 1/6 each of power, B’s 1/10 each of power) 94

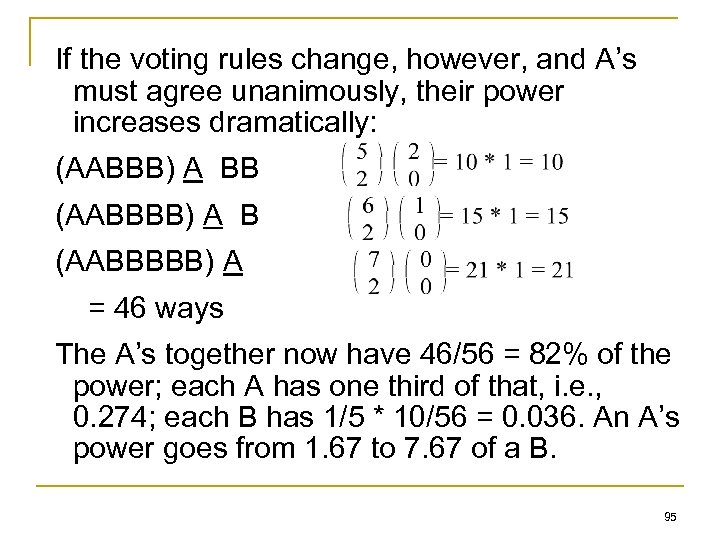

If the voting rules change, however, and A’s must agree unanimously, their power increases dramatically: (AABBB) A BB (AABBBB) A B (AABBBBB) A = 46 ways The A’s together now have 46/56 = 82% of the power; each A has one third of that, i. e. , 0. 274; each B has 1/5 * 10/56 = 0. 036. An A’s power goes from 1. 67 to 7. 67 of a B. 95

If the voting rules change, however, and A’s must agree unanimously, their power increases dramatically: (AABBB) A BB (AABBBB) A B (AABBBBB) A = 46 ways The A’s together now have 46/56 = 82% of the power; each A has one third of that, i. e. , 0. 274; each B has 1/5 * 10/56 = 0. 036. An A’s power goes from 1. 67 to 7. 67 of a B. 95

Fill Out the Seker Hora’a! n Don’t forget to fill out the “seker hora’a” for Intro to Multi-Agent Systems, Course 67715: http: //www. huji. ac. il/seker 7 -96

Fill Out the Seker Hora’a! n Don’t forget to fill out the “seker hora’a” for Intro to Multi-Agent Systems, Course 67715: http: //www. huji. ac. il/seker 7 -96

In my Daughter Elianna’s 7 th Grade Class… n Class has to decide about class shirt: 97

In my Daughter Elianna’s 7 th Grade Class… n Class has to decide about class shirt: 97

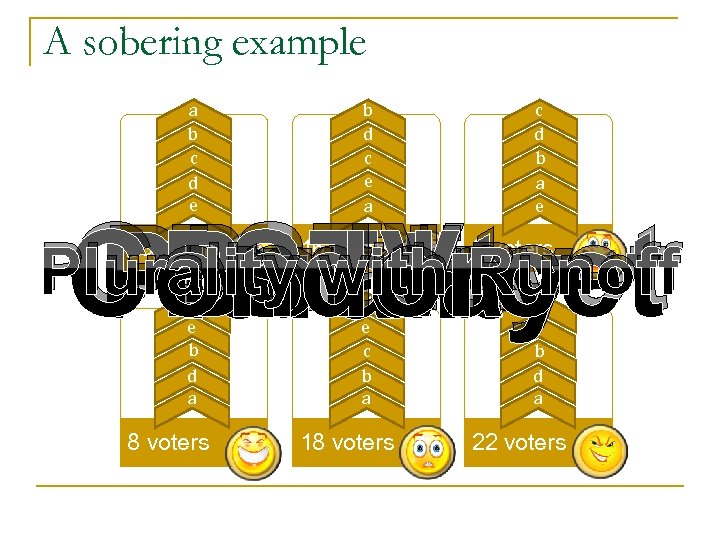

Preferences n n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, green, red, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink What should be chosen? The teacher uses plurality voting, and declares pink the winner My daughter, who knows about voting and doesn’t like pink, protests 98

Preferences n n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, green, red, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink What should be chosen? The teacher uses plurality voting, and declares pink the winner My daughter, who knows about voting and doesn’t like pink, protests 98

Preferences n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, green, red, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink My daughter wants a run-off election (plurality with run-off), and blue will win 99

Preferences n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, green, red, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink My daughter wants a run-off election (plurality with run-off), and blue will win 99

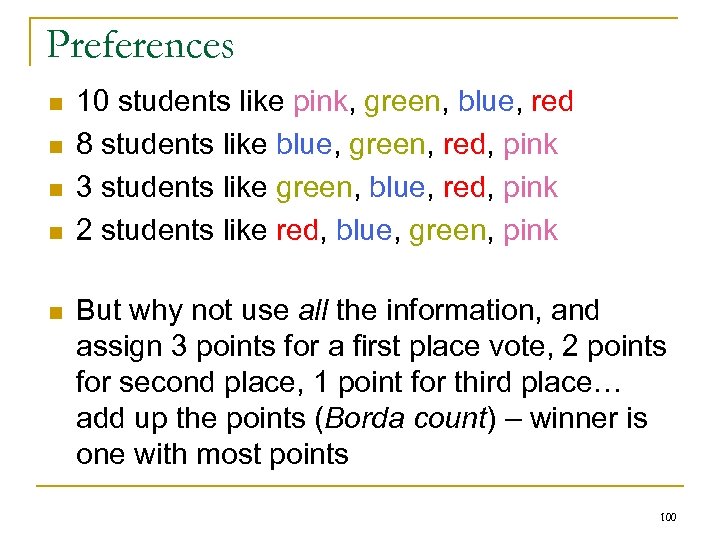

Preferences n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, green, red, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink But why not use all the information, and assign 3 points for a first place vote, 2 points for second place, 1 point for third place… add up the points (Borda count) – winner is one with most points 100

Preferences n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, green, red, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink But why not use all the information, and assign 3 points for a first place vote, 2 points for second place, 1 point for third place… add up the points (Borda count) – winner is one with most points 100

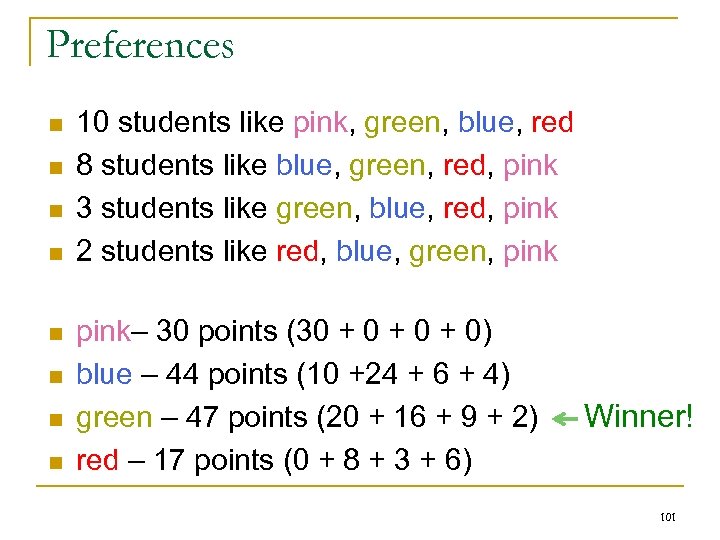

Preferences n n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, green, red, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink– 30 points (30 + 0 + 0) blue – 44 points (10 +24 + 6 + 4) green – 47 points (20 + 16 + 9 + 2) red – 17 points (0 + 8 + 3 + 6) Winner! 101

Preferences n n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, green, red, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink– 30 points (30 + 0 + 0) blue – 44 points (10 +24 + 6 + 4) green – 47 points (20 + 16 + 9 + 2) red – 17 points (0 + 8 + 3 + 6) Winner! 101

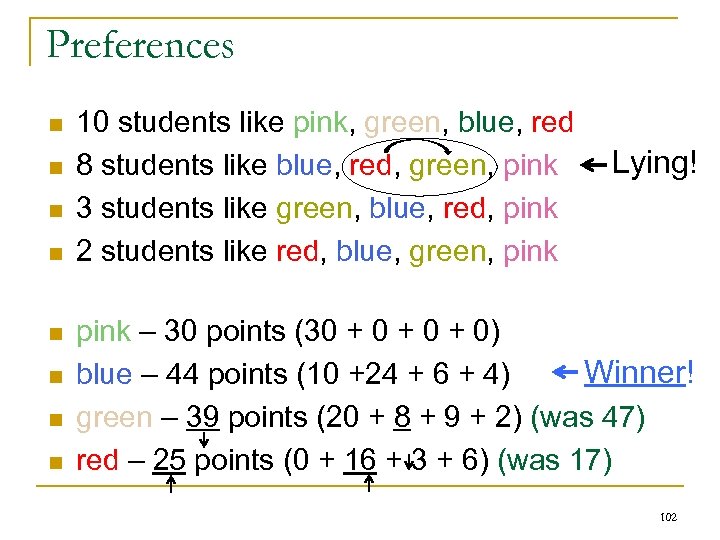

Preferences n n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, red, green, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink Lying! pink – 30 points (30 + 0 + 0) Winner! blue – 44 points (10 +24 + 6 + 4) green – 39 points (20 + 8 + 9 + 2) (was 47) red – 25 points (0 + 16 + 3 + 6) (was 17) 102

Preferences n n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, red, green, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink Lying! pink – 30 points (30 + 0 + 0) Winner! blue – 44 points (10 +24 + 6 + 4) green – 39 points (20 + 8 + 9 + 2) (was 47) red – 25 points (0 + 16 + 3 + 6) (was 17) 102

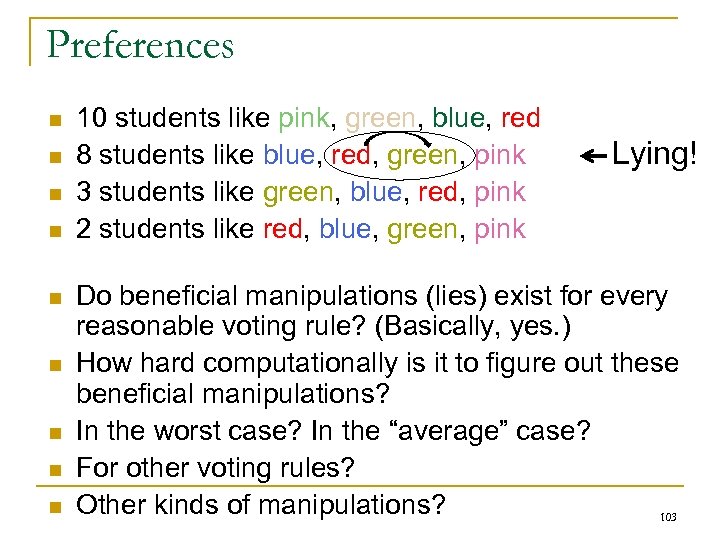

Preferences n n n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, red, green, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink Lying! Do beneficial manipulations (lies) exist for every reasonable voting rule? (Basically, yes. ) How hard computationally is it to figure out these beneficial manipulations? In the worst case? In the “average” case? For other voting rules? Other kinds of manipulations? 103

Preferences n n n n n 10 students like pink, green, blue, red 8 students like blue, red, green, pink 3 students like green, blue, red, pink 2 students like red, blue, green, pink Lying! Do beneficial manipulations (lies) exist for every reasonable voting rule? (Basically, yes. ) How hard computationally is it to figure out these beneficial manipulations? In the worst case? In the “average” case? For other voting rules? Other kinds of manipulations? 103

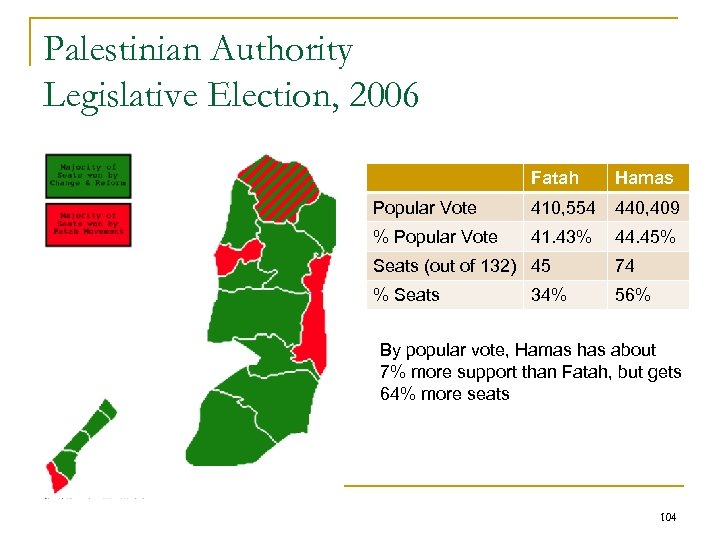

Palestinian Authority Legislative Election, 2006 Fatah Hamas Popular Vote 410, 554 440, 409 % Popular Vote 41. 43% 44. 45% Seats (out of 132) 45 74 % Seats 56% 34% By popular vote, Hamas has about 7% more support than Fatah, but gets 64% more seats 104

Palestinian Authority Legislative Election, 2006 Fatah Hamas Popular Vote 410, 554 440, 409 % Popular Vote 41. 43% 44. 45% Seats (out of 132) 45 74 % Seats 56% 34% By popular vote, Hamas has about 7% more support than Fatah, but gets 64% more seats 104

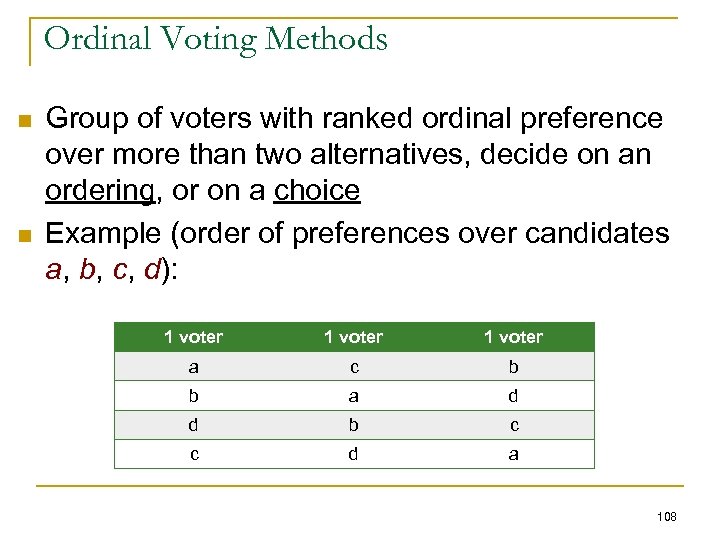

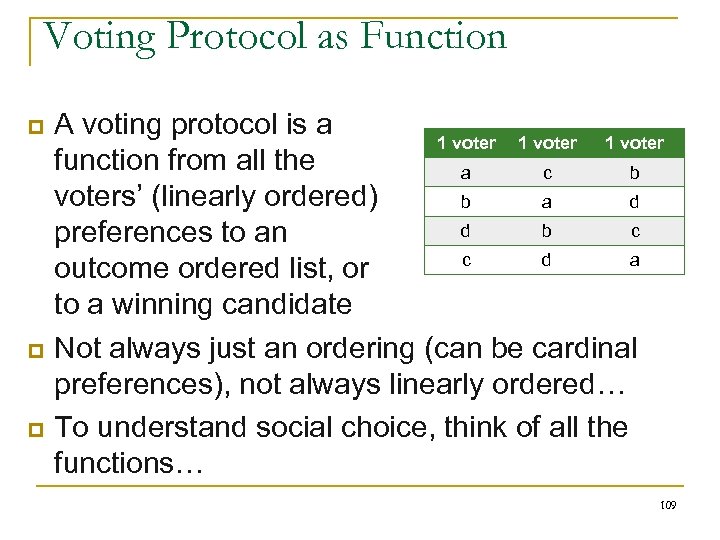

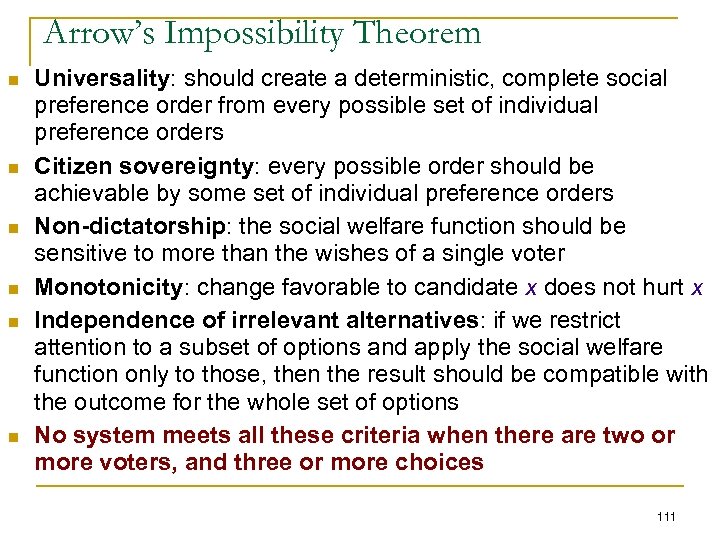

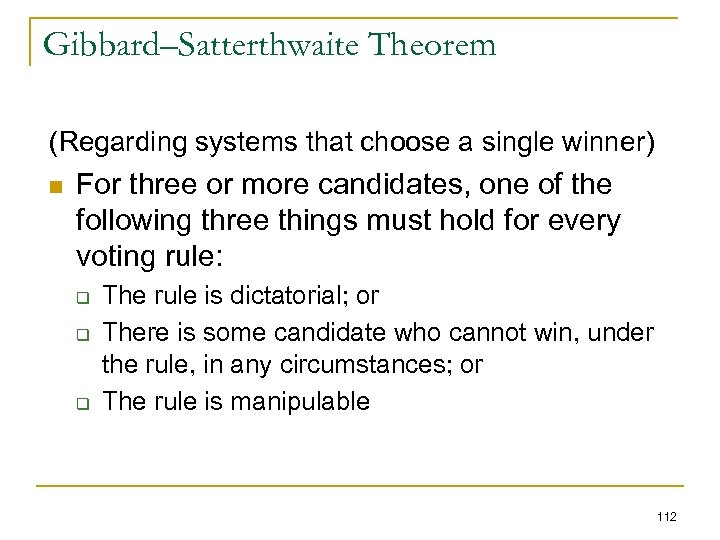

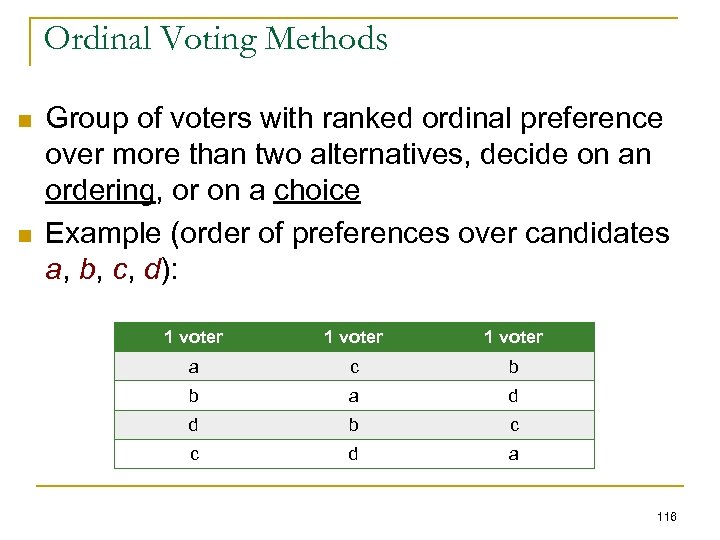

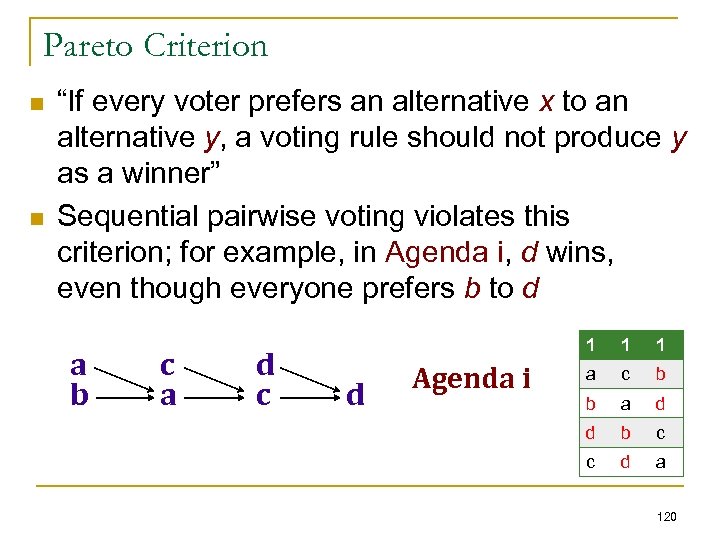

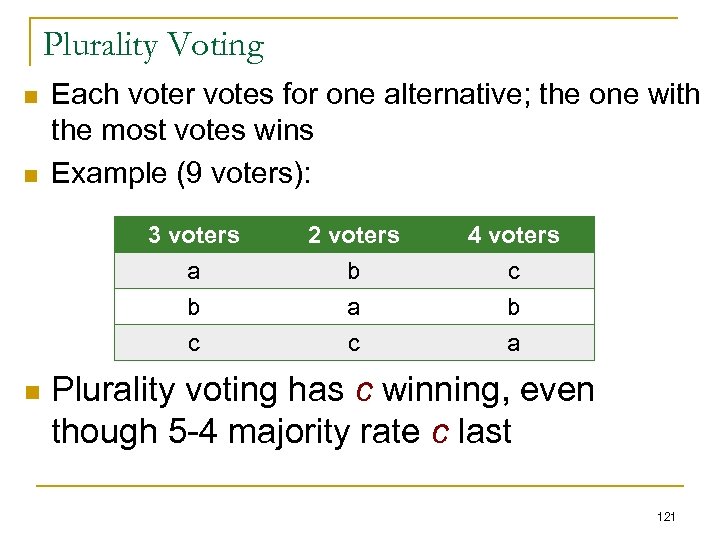

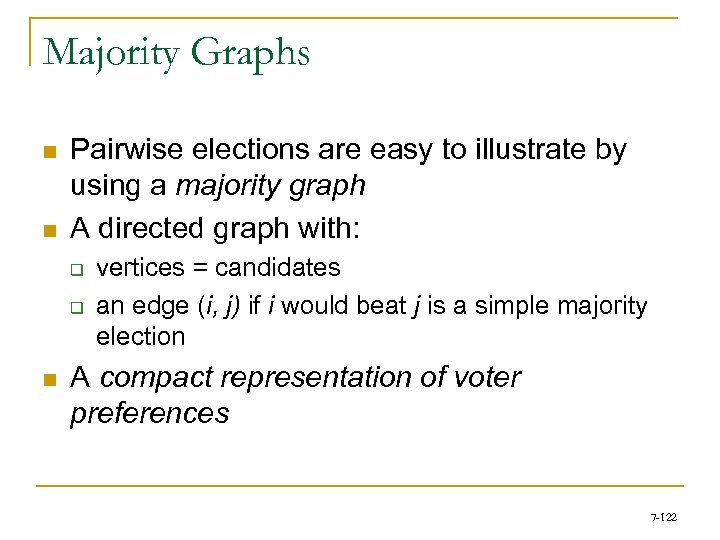

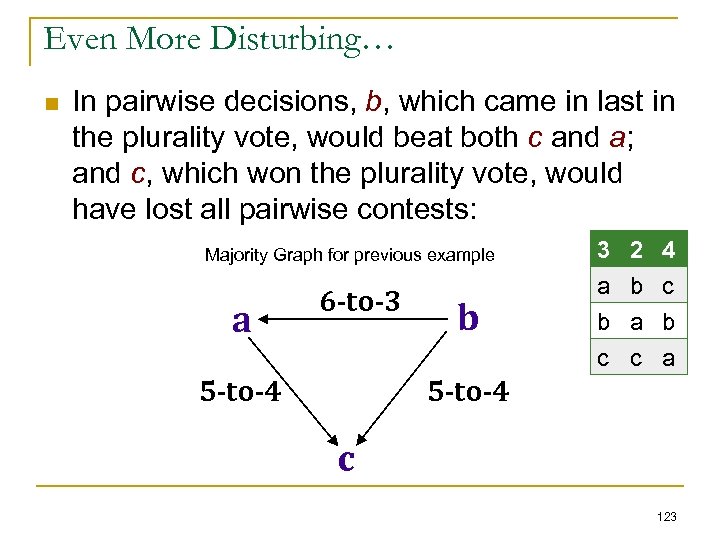

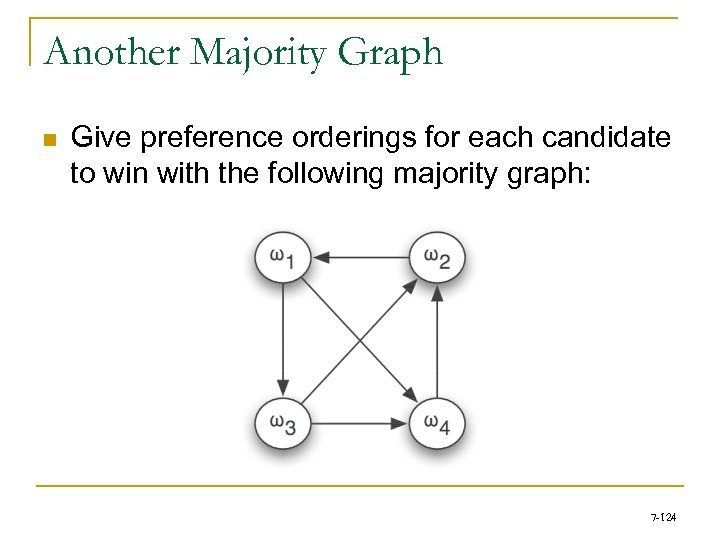

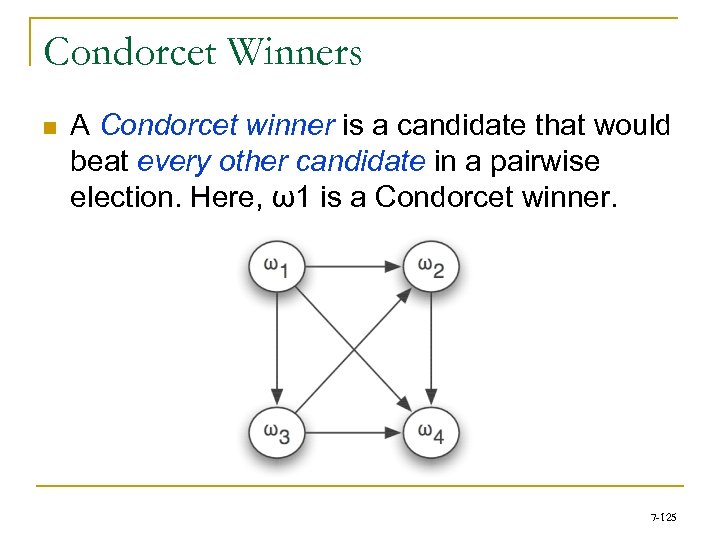

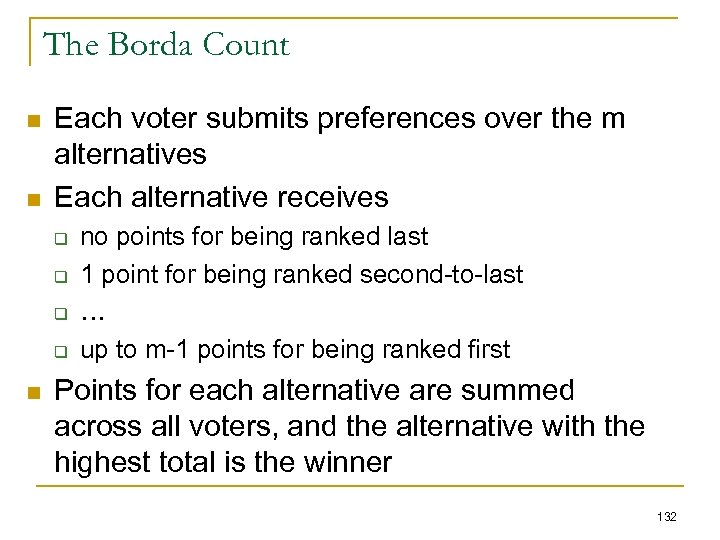

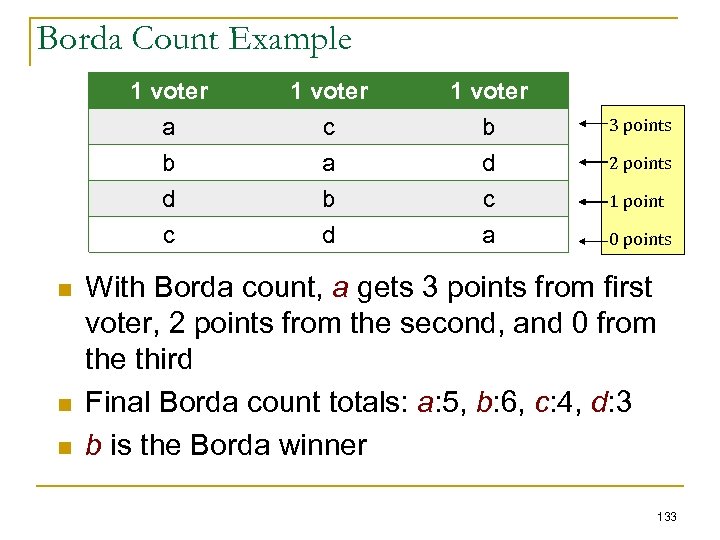

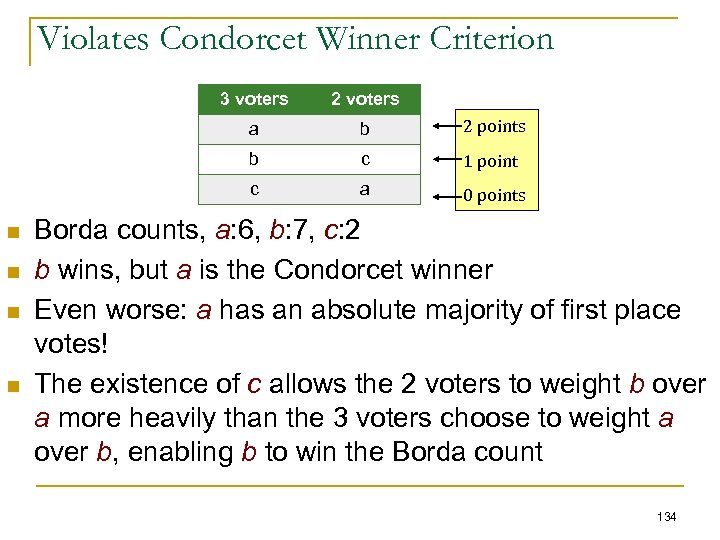

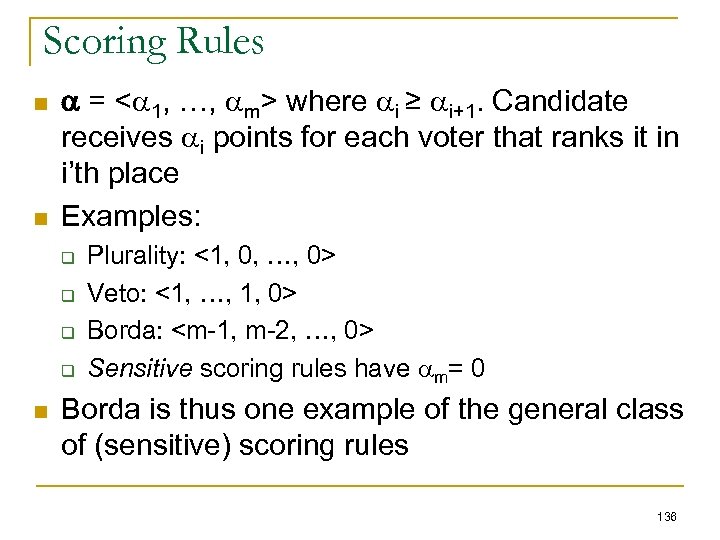

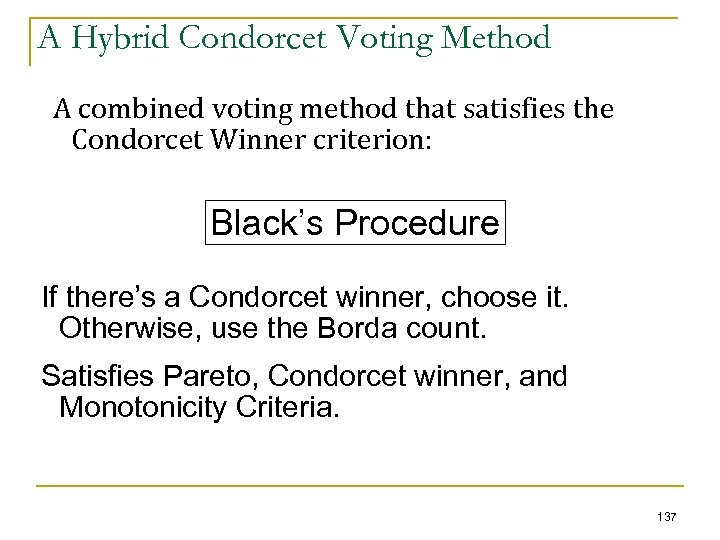

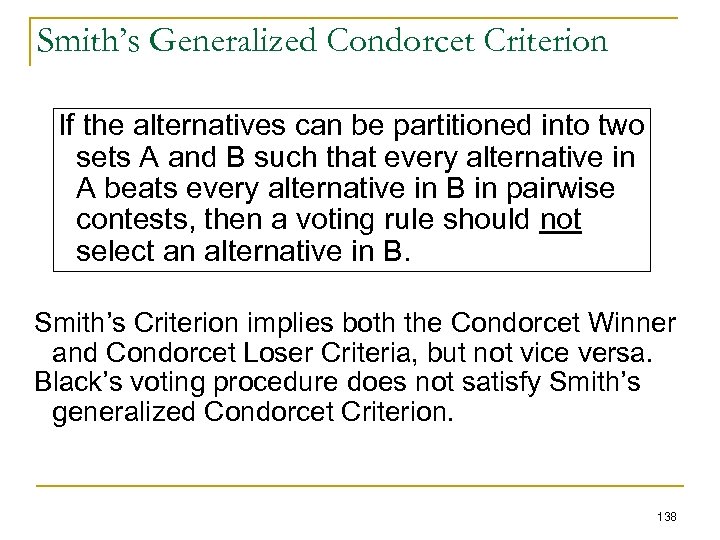

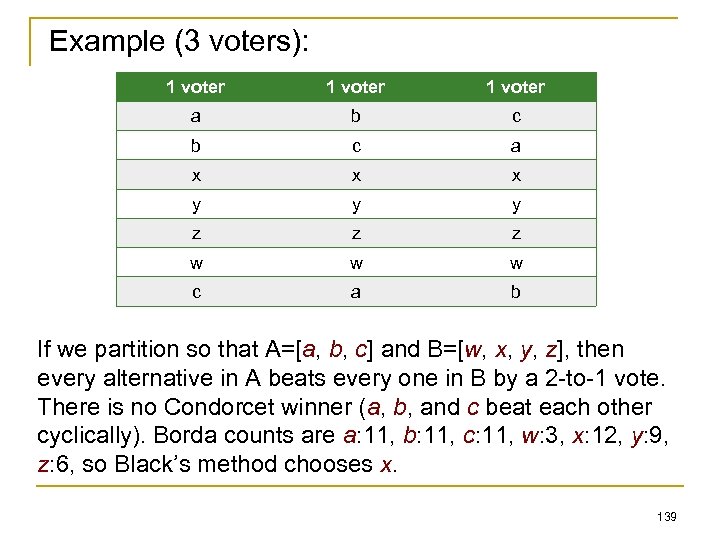

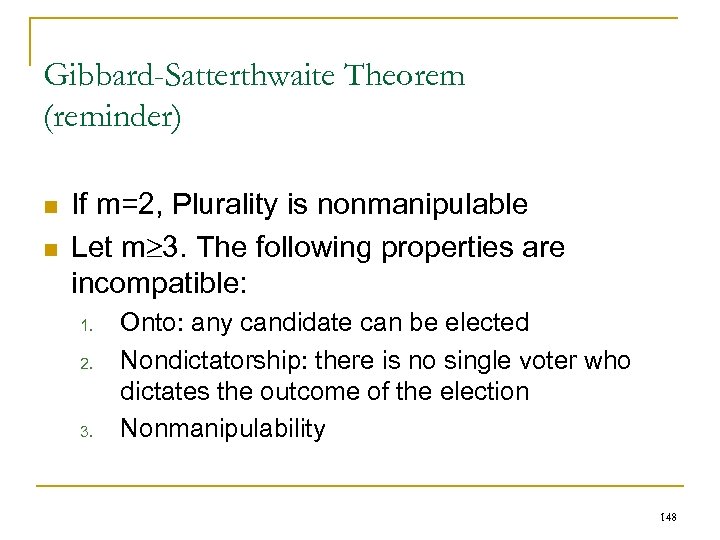

Palestinian Authority Legislative Election, 2006 n n This could be a result of district division of votes, but more likely was a result of the voting rule used (mixed proportional and district voting) Simplified Example: Multiple candidates from same party split vote; A and B are from same party q q q n n 32% of voters prefer A > B > C 30% of voters prefer B > A > C 36% of voters prefer C > A > B Plurality vote: C wins Couldn’t we figure out a way to combine the first two groups of voters? We could, if we used Single Transferable Vote, STV (also known as Instant Runoff Voting, IRV) 105