a697cb8ad671f16c8fe9ef04a4de2947.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 91

Lecture 28: Binary-Valued Dependent Variables (Chapter 19. 1– 19. 2) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

Agenda • Binary-Valued Dependent Variables (Chapter 19. 1) • Probit/Logit Models (Chapter 19. 2) • Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (Chapter 19. 2) • Deriving Probit/Logit (Chapter 19. 2) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 2

Binary Dependent Variables • We have worked extensively with regression models in which Y is continuous. • We have predicted the effect of education and experience on earnings. • We have predicted the effect of exogenous changes in price on quantity demanded. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 3

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • However, our methods are inappropriate when the dependent variable takes on just a few discrete values. • For example, we may be interested in the effect of a brand’s advertising on consumers’ decisions to buy that brand. • We may want to predict the effect of Head Start on children’s graduating from high school. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 4

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • Discrete-valued dependent variables are a special case that comes up sufficiently frequently to warrant its own special techniques. • In this lecture, we will focus on dependent variables that can take on only 2 values, 0 or 1 (dummy variables). Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 5

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • Suppose we were to predict whether NFL football teams win individual games, using the reported point spread from sports gambling authorities. • For example, if the Packers have a spread of 6 against the Dolphins, the gambling authorities expect the Packers to lose by no more than 6 points. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 6

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • Using the techniques we have developed so far, we might regress • How would we interpret the coefficients and predicted values from such a model? Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 7

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • Di. Win is either 0 or 1. It does not make sense to say that a 1 point increase in the spread increases Di. Win by b 1. Di. Win can change only from 0 to 1 or from 1 to 0. • Instead of predicting Di. Win itself, we predict the probability that Di. Win = 1. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 8

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • It can make sense to say that a 1 point increase in the spread increases the probability of winning by b 1. • Our predicted values of Di. Win are the probability of winning. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 9

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • When we use a linear regression model to estimate probabilities, we call the model the linear probability model. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 10

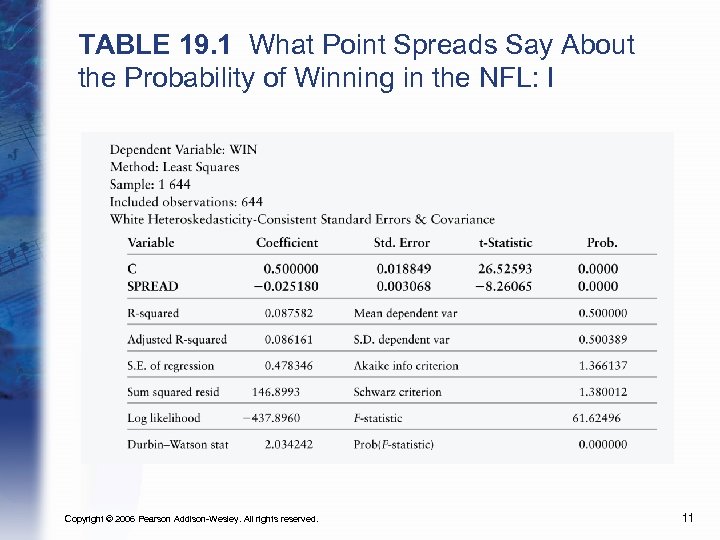

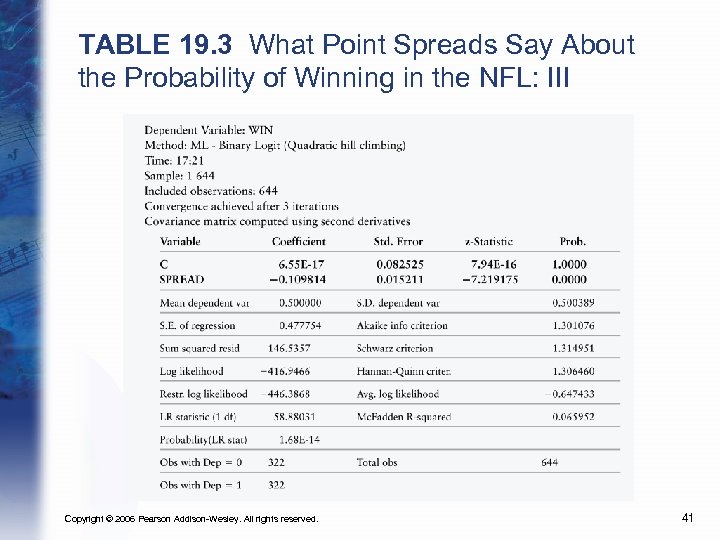

TABLE 19. 1 What Point Spreads Say About the Probability of Winning in the NFL: I Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 11

Binary Dependent Variables • Note that the table reports White Robust Estimated Standard Errors. • The Linear Probability Model disturbances are heteroskedastic. • Heteroskedasticity is the only violation of the Gauss–Markov assumptions inherent in using dummy variables as Y. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 12

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • The linear probability model works fine mathematically. • However, it faces a serious drawback in interpretation. • If the point spread is 21 points, the team’s predicted probability of winning is: 0. 5 - 0. 025 • 21 = -0. 025 Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 13

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • If X = 21, E(Y | X ) = -0. 025 • We predict that the team has a -2. 5% probability of victory. • If X = -21, we predict that the team has a 102. 5% probability of victory. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 14

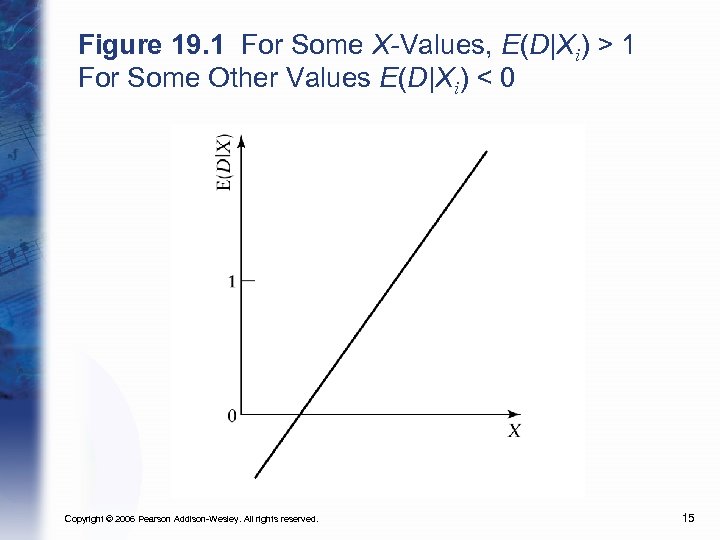

Figure 19. 1 For Some X-Values, E(D|Xi) > 1 For Some Other Values E(D|Xi) < 0 Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 15

Binary Dependent Variables • Linear regression methods predict values between -∞ and +∞. • Probabilities must fall between 0 and 1. • The linear probability model cannot guarantee sensible predictions. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 16

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • Intuitively, if the linear probability model predicts a -2. 5% chance of victory, we expect the team to have a very small probability of winning. • Similarly, if we predict that the team has a 102. 5% chance of victory, we expect the team to have a very high probability of winning. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 17

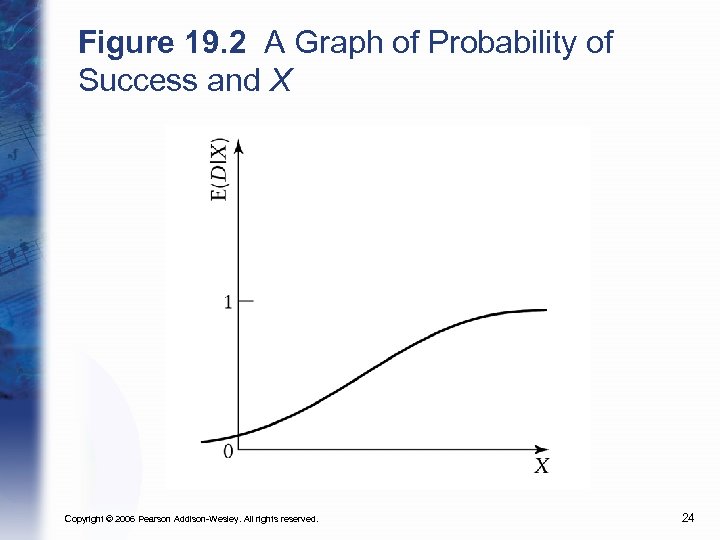

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • We need a procedure to translate our linear regression results into true probabilities. • We need a function that takes a value from -∞ to +∞ and returns a value from 0 to 1. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 18

Binary Dependent Variables (cont. ) • We want a translator such that: The closer to -∞ is the value from our linear regression model, the closer to 0 is our predicted probability. The closer to +∞ is the value from our linear regression model, the closer to 1 is our predicted probability. No predicted probabilities are less than 0 or greater than 1. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 19

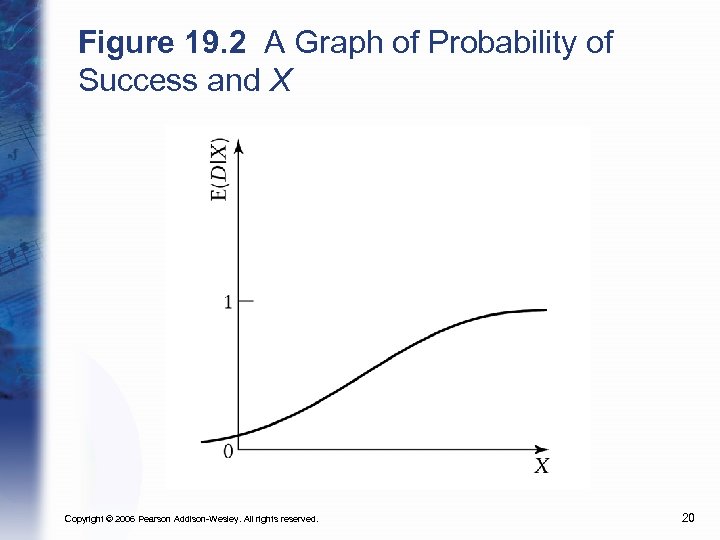

Figure 19. 2 A Graph of Probability of Success and X Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 20

Binary Dependent Variables • How can we construct such a translator? • How can we estimate it? Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 21

Probit/Logit Models (Chapter 19. 2) • In common practice, econometricians use TWO such “translators”: probit logit • The differences between the two models are subtle. • For present purposes there is no practical difference between the two models. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 22

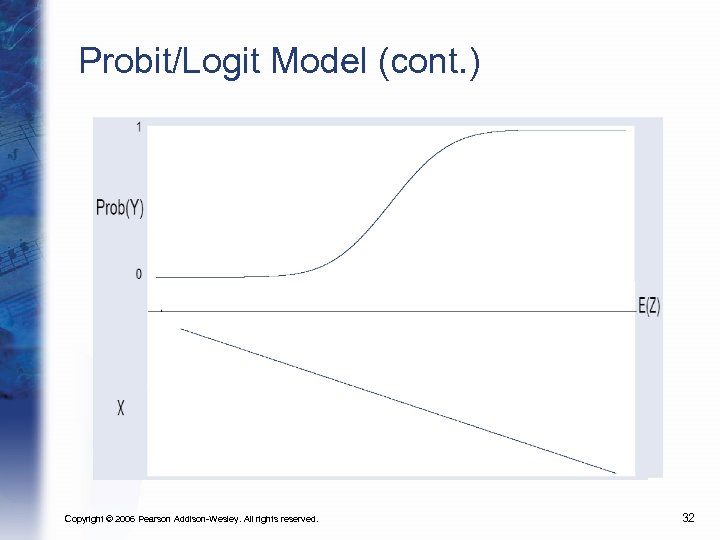

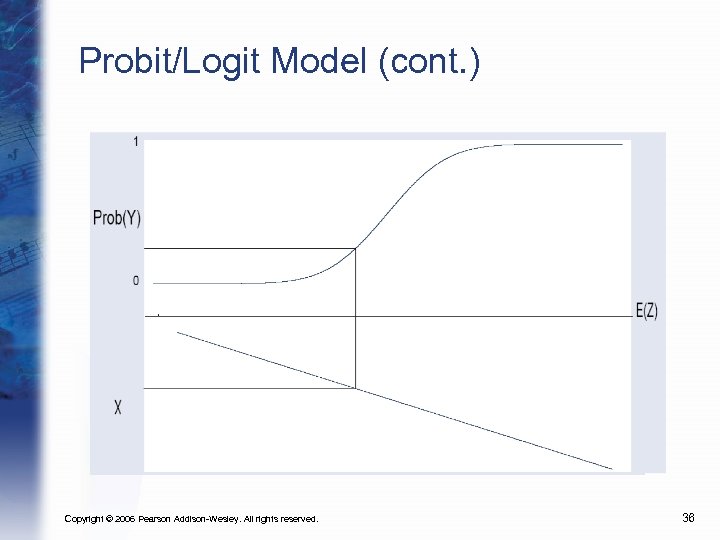

Probit/Logit Models (cont. ) • Notice that the slope varies dramatically. • When the team is very likely or very unlikely to win, a small change in the point spread has very little impact. • When the team’s chance of victory is 50/50, a small change in the point spread can lead to a large change in probabilities. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 23

Figure 19. 2 A Graph of Probability of Success and X Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 24

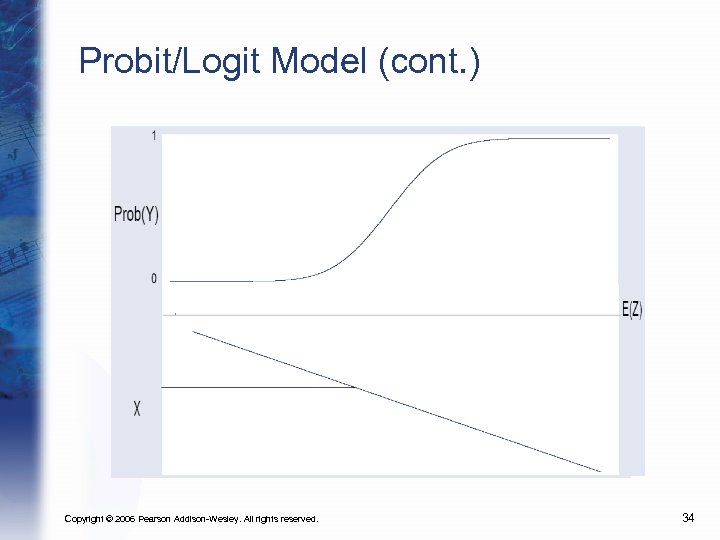

Probit/Logit Models • Both the Probit and Logit models have the same basic structure. 1. Estimate a latent variable Z using a linear model. Z ranges from negative infinity to positive infinity. 2. Use a non-linear function to transform Z into a predicted Y value between 0 and 1. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 25

Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • Suppose there is some unobserved continuous variable Z that can take on values from negative infinity to infinity. • The higher E(Z) is, the more probable it is that a team will win, or a student will graduate, or a consumer will purchase a particular brand. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 26

Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • We call an unobserved variable, Z, that we use for intermediate calculations, a latent variable. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 27

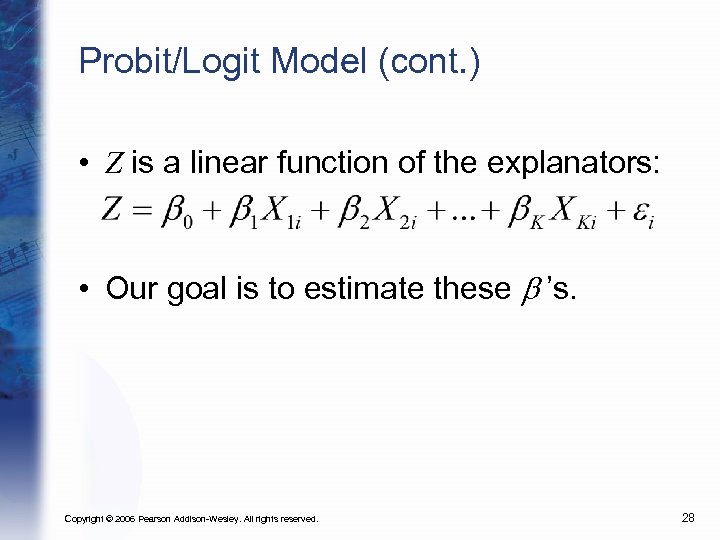

Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • Z is a linear function of the explanators: • Our goal is to estimate these b ’s. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 28

Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • We will focus particularly on E(Z): • It is convenient to consider the E(Z) separately from its stochastic component. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 29

Probit/Logit (cont. ) • The predicted probability of Y is a non-linear function of E(Z). • The probit model uses the standard normal cumulative density function. • The logit model uses the logistic cumulative density function. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 30

Probit/Logit (cont. ) • The logistic cumulative density function is computationally much more tractable than the standard normal, but modern computers can calculate probits quite easily. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 31

Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 32

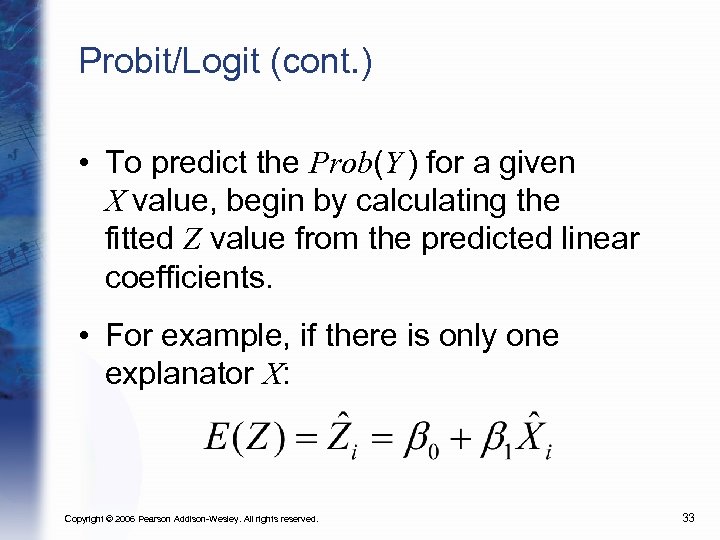

Probit/Logit (cont. ) • To predict the Prob(Y ) for a given X value, begin by calculating the fitted Z value from the predicted linear coefficients. • For example, if there is only one explanator X: Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 33

Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 34

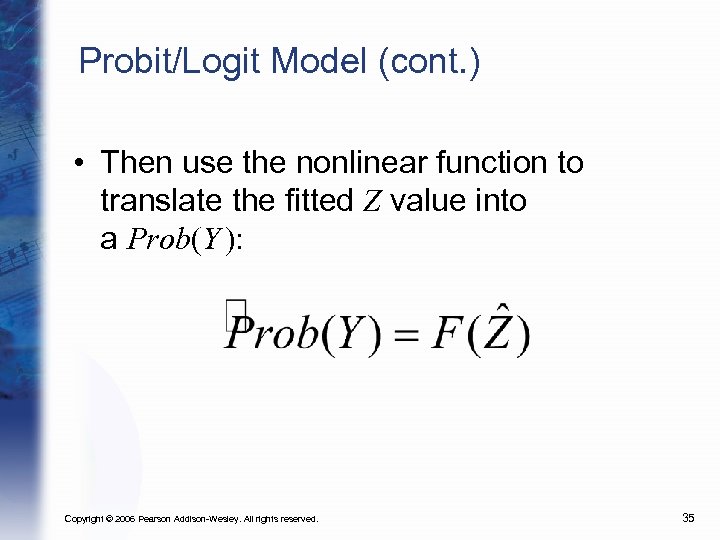

Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • Then use the nonlinear function to translate the fitted Z value into a Prob(Y ): Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 35

Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 36

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (Chapter 19. 2) • In practice, how do we implement a probit or logit model? • Either model is estimated using a statistical method called the method of maximum likelihood. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 37

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • You must specify three elements: 1. The dummy outcome variable (whether the NFL team actually won game i) 2. The explanator/s (the NFL team’s point spread for game i) 3. Which nonlinear function F( • ) you wish to use (you specify F when you tell the computer whether to use logit or probit) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 38

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • The computer then calculates the b ’s that assigns the highest probability to the outcomes that were observed. • The computer can calculate the b ’s for you. You must know how to interpret them. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 39

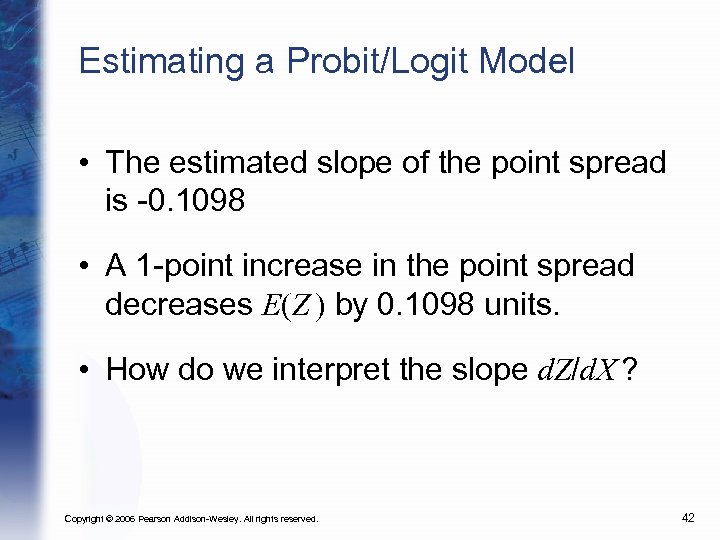

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • For example, let us estimate the probability of winning an NFL game using the logit model. • We could just as easily have used the probit model. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 40

TABLE 19. 3 What Point Spreads Say About the Probability of Winning in the NFL: III Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 41

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model • The estimated slope of the point spread is -0. 1098 • A 1 -point increase in the point spread decreases E(Z ) by 0. 1098 units. • How do we interpret the slope d. Z/d. X ? Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 42

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • In a linear regression, we look to coefficients for three elements: 1. Statistical significance: You can still read statistical significance from the slope d. Z/d. X. The z-statistic reported for probit or logit is analogous to OLS’s t-statistic. 2. Sign: If d. Z/d. X is positive, then d. Prob(Y)/d. X is also positive. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 43

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) The z-statistic on the point spread is -7. 22, well exceeding the 5% critical value of 1. 96. The point spread is a statistically significant explanator of winning NFL games. The sign of the coefficient is negative. A higher point spread predicts a lower chance of winning. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 44

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) 3. Magnitude: the magnitude of d. Z/d. X has no particular interpretation. We care about the magnitude of d. Prob(Y)/d. X. From the computer output for a probit or logit estimation, you can interpret the statistical significance and sign of each coefficient directly. Assessing magnitude is trickier. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 45

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • Problems in Interpreting Magnitude: 1. The estimated coefficient relates X to Z. We care about the relationship between X and Prob(Y = 1). 2. The effect of X on Prob(Y = 1) varies depending on Z. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 46

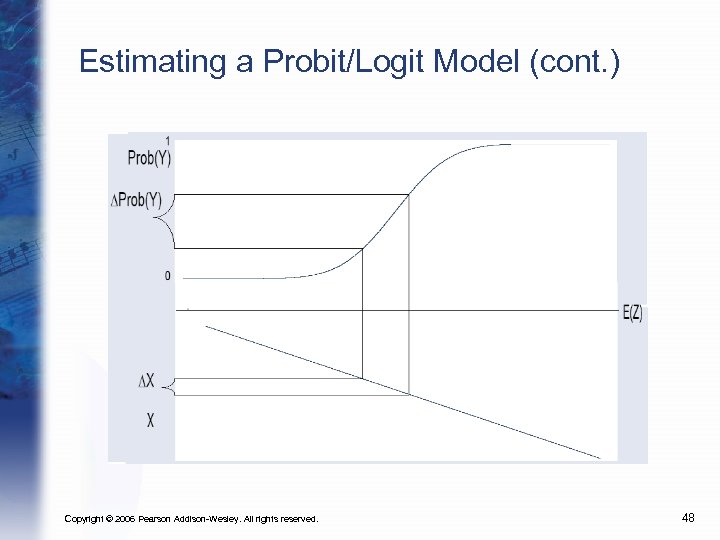

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • There are two basic approaches to assessing the magnitude of the estimated coefficient. • One approach is to predict Prob(Y ) for different values of X, to see how the probability changes as X changes. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 47

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 48

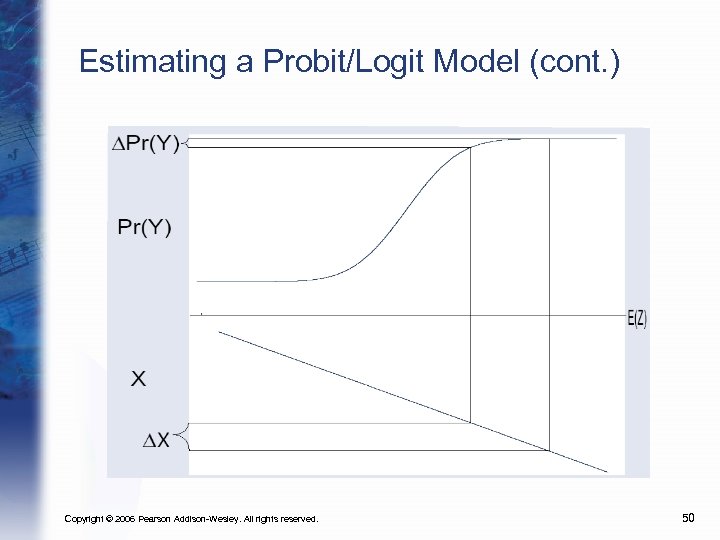

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • Note Well: the effect of a 1 -unit change in X varies greatly, depending on the initial value of E(Z ). • E(Z ) depends on the values of all explanators. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 49

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 50

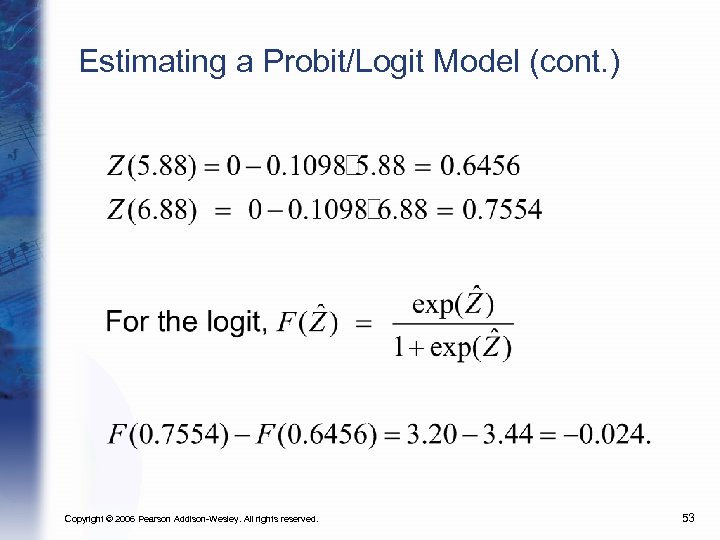

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • For example, let’s consider the effect of 1 point change in the point spread, when we start 1 standard deviation above the mean, at SPREAD = 5. 88 points. • Note: In this example, there is only one explanator, SPREAD. If we had other explanators, we would have to specify their values for this calculation, as well. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 51

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • Step One: Calculate the E(Z ) values for X = 5. 88 and X = 6. 88, using the fitted values. • Step Two: Plug the E(Z ) values into the formula for the logistic density function. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 52

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 53

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • Changing the point spread from 5. 88 to 6. 88 predicts a 2. 4 percentage point decrease in the team’s chance of victory. • Note that changing the point spread from 8. 88 to 9. 88 predicts only a 2. 1 percentage point decrease. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 54

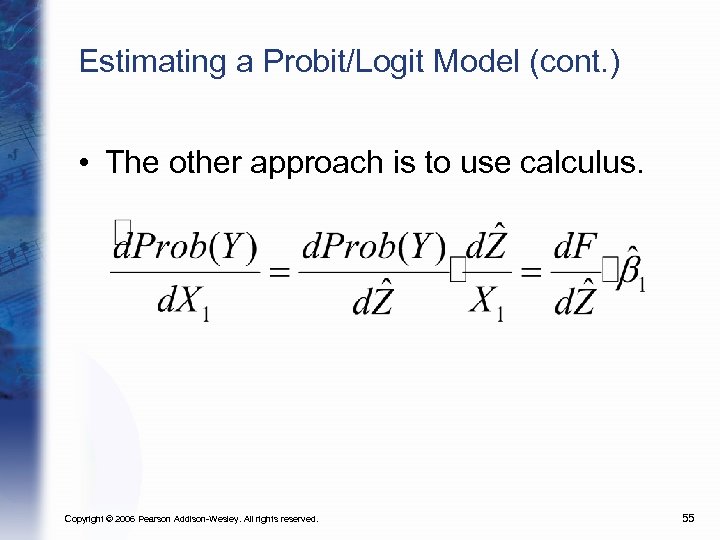

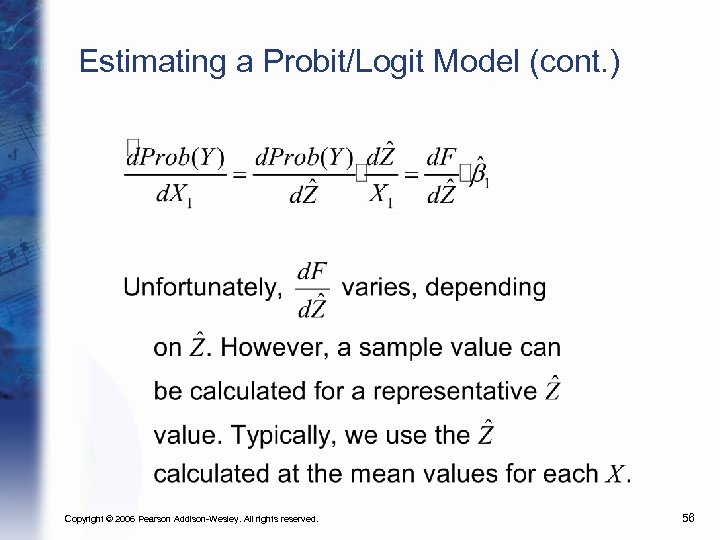

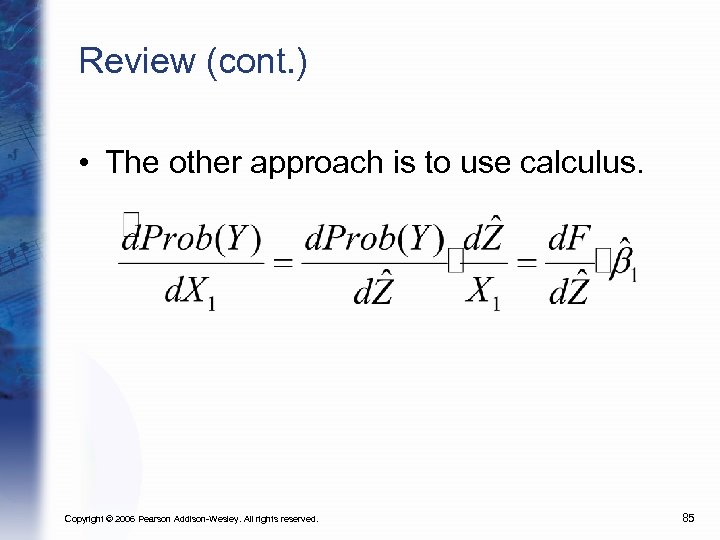

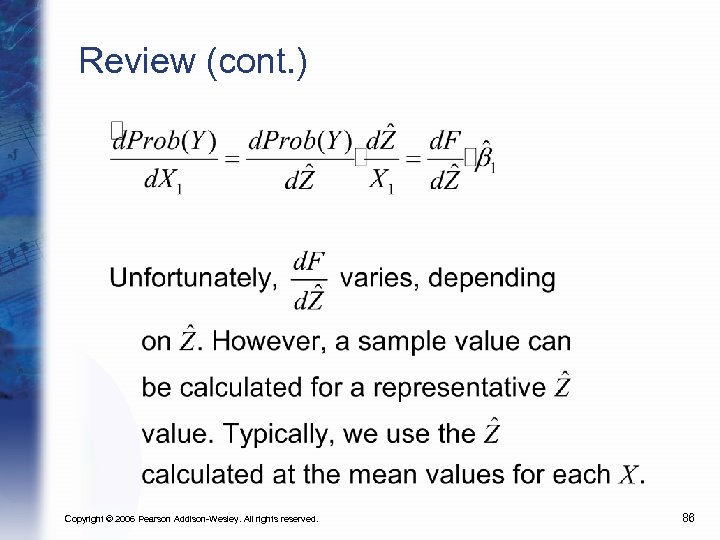

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • The other approach is to use calculus. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 55

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 56

Estimating a Probit/Logit Model (cont. ) • Some econometrics software packages can calculate such “pseudo-slopes” for you. • In STATA, the command is “dprobit. ” • EViews does NOT have this function. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 57

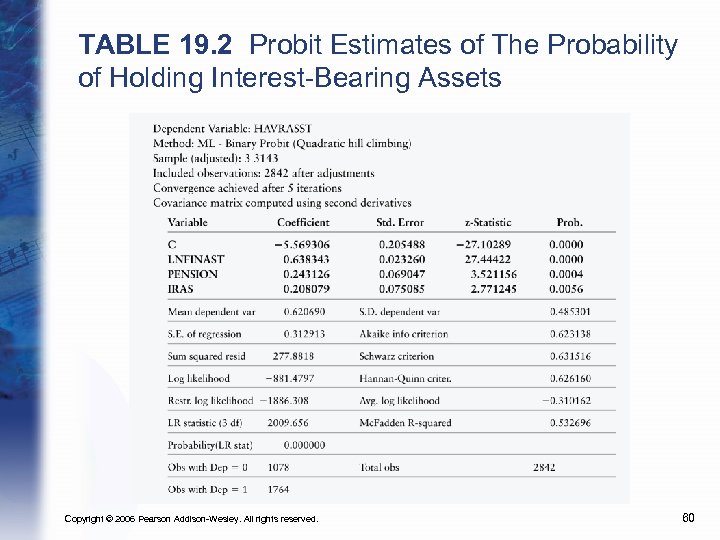

Checking Understanding • The following table reports a probit on the probability of holding interestbearing assets, as a function of total financial assets (LNFINAST) and dummy variables for having a pension (PENSION) or IRA (IRAS). Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 58

Checking Understanding (cont. ) • What can you determine about the effects of each explanator, based directly on the table? • Suggest a follow-up calculation to give a clearer understanding of the impact on Y of having a pension (the dummy variable PENSION). Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 59

TABLE 19. 2 Probit Estimates of The Probability of Holding Interest-Bearing Assets Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 60

Checking Understanding • We can directly see that all three explanators are statistically significant (using the z-statistics). • Also, all three explanators have positive coefficients. Increasing total financial assets, having a pension, and having an IRA all increase the probability of holding interest-bearing assets. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 61

Checking Understanding (cont. ) • To assess the magnitude of the coefficient on PENSION, we need to conduct a follow-up calculation. • A reasonable calculation would be to predict Prob(Y ) when PENSION = 0 and when PENSION = 1, holding the other explanators fixed at their sample means. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 62

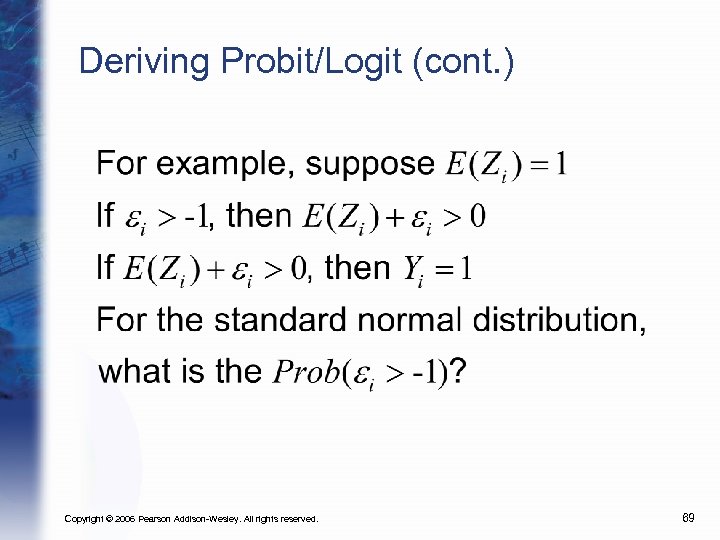

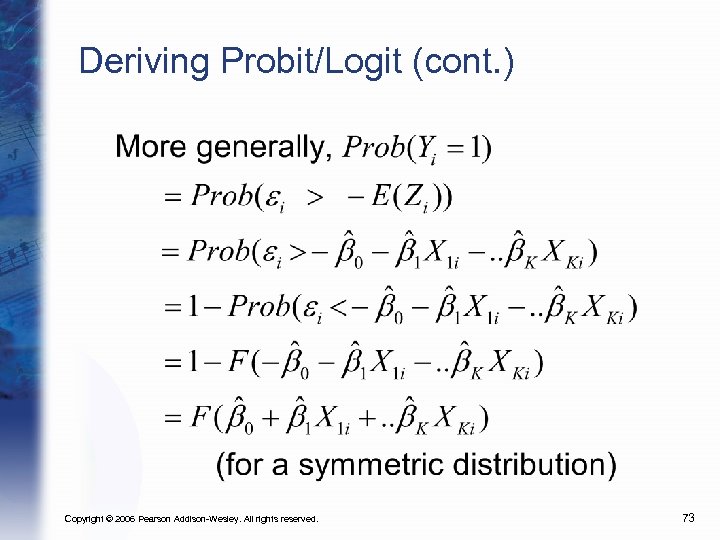

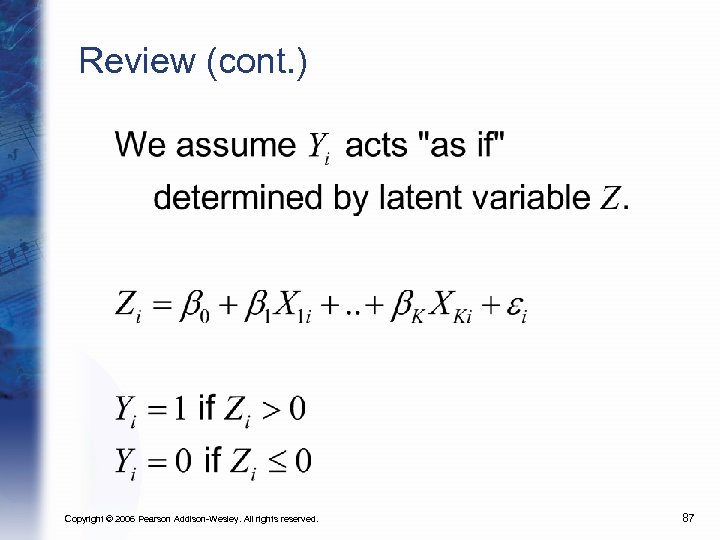

Deriving Probit/Logit (Chapter 19. 2) • Where do the Logit and Probit estimators come from? • How does the latent variable Z determine whether Y = 1 or Y = 0? • What role do the ei ’s play? Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 63

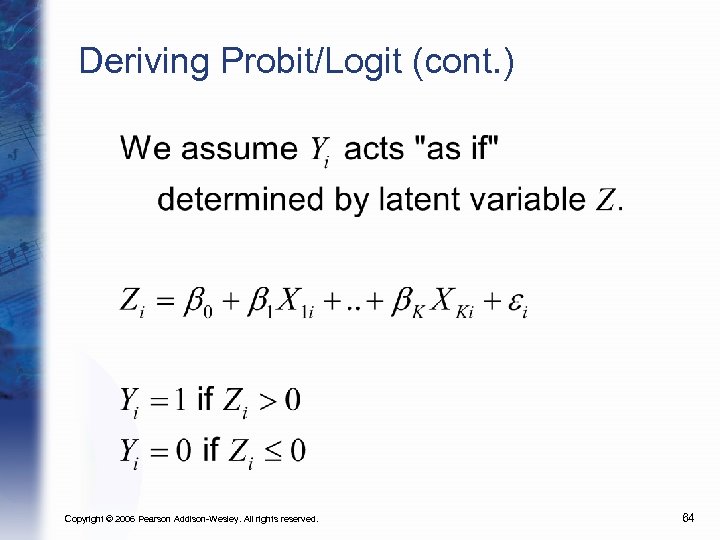

Deriving Probit/Logit (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 64

Deriving Probit/Logit (cont. ) • Note: the assumption that the breakpoint falls at 0 is arbitrary. • b 0 can adjust for whichever breakpoint you might choose to set. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 65

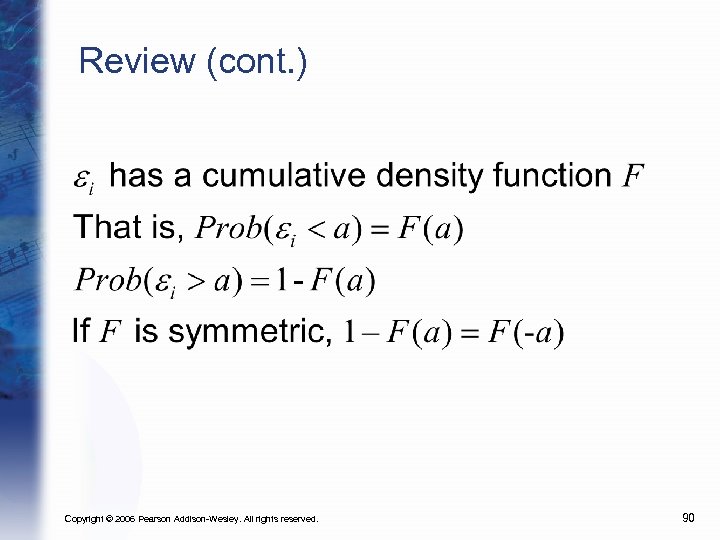

Deriving Probit/Logit (cont. ) • We assume we know the distribution of ei. • In the probit model, we assume ei is distributed by the standard normal. • In the logit model, we assume ei is distributed by the logistic. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 66

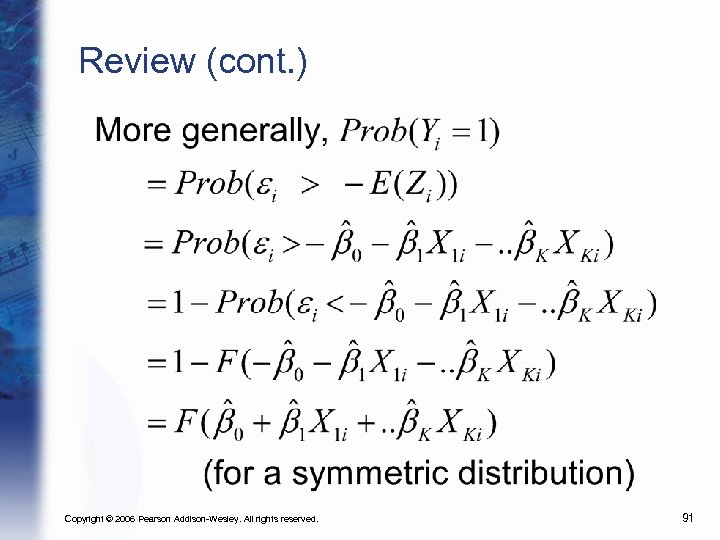

Deriving Probit/Logit (cont. ) • The key to Probit/Logit: since we know the distribution of ei , we can calculate the probability that a given observation receives a shock ei that pushes Z into the Z > 0 or Z < 0 region. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 67

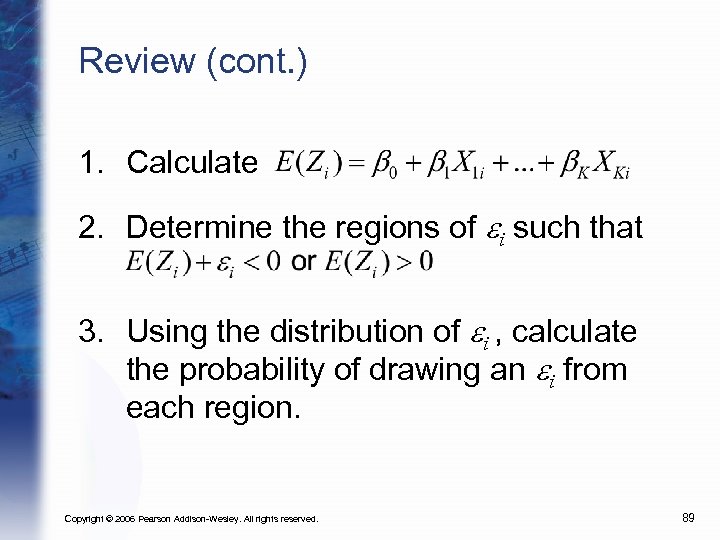

Deriving Probit/Logit (cont. ) 1. Calculate 2. Determine the regions of ei such that 3. Using the distribution of ei , calculate the probability of drawing an ei from each region. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 68

Deriving Probit/Logit (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 69

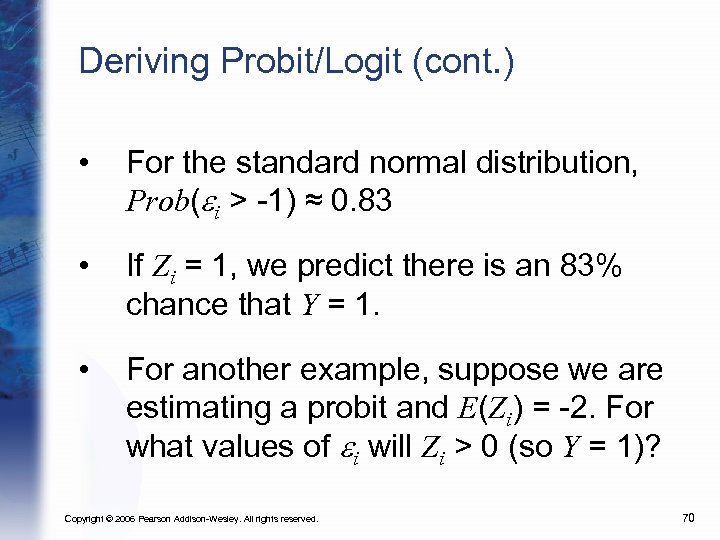

Deriving Probit/Logit (cont. ) • For the standard normal distribution, Prob(ei > -1) ≈ 0. 83 • If Zi = 1, we predict there is an 83% chance that Y = 1. • For another example, suppose we are estimating a probit and E(Zi) = -2. For what values of ei will Zi > 0 (so Y = 1)? Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 70

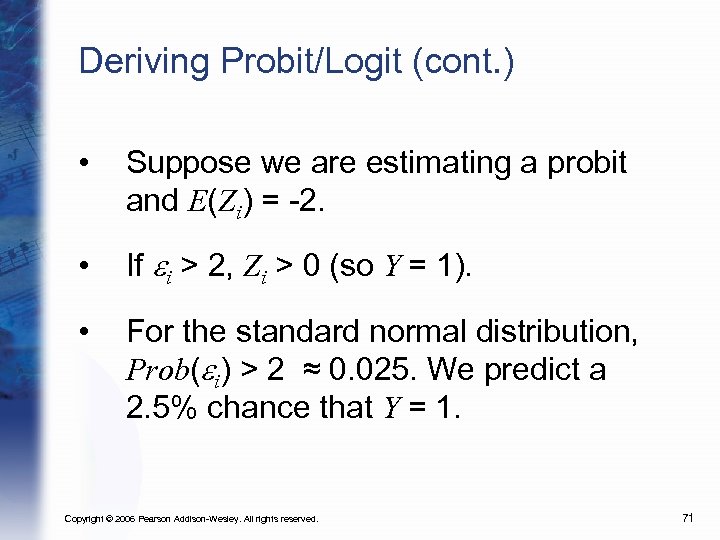

Deriving Probit/Logit (cont. ) • Suppose we are estimating a probit and E(Zi) = -2. • If ei > 2, Zi > 0 (so Y = 1). • For the standard normal distribution, Prob(ei) > 2 ≈ 0. 025. We predict a 2. 5% chance that Y = 1. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 71

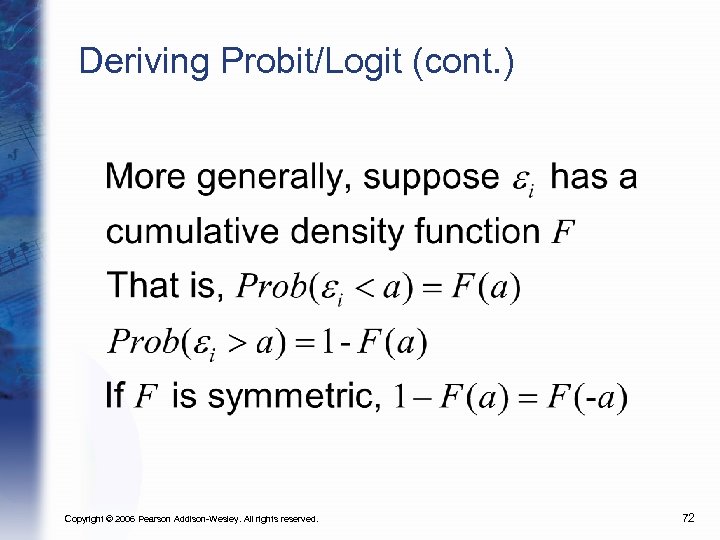

Deriving Probit/Logit (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 72

Deriving Probit/Logit (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 73

Review • Frequently econometricians wish to estimate the probability that a discrete event occurs. • The Linear Probability Model: estimating a probability by using a linear model (e. g. OLS) with a dummy variable for Y. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 74

Review (cont. ) • Problems with the Linear Probability Model: – OLS disturbances are heteroskedastic. – OLS predictions range from - ∞ to + ∞. A probability needs to range from 0 to 1. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 75

Review (cont. ) • Solution: Probit or Logit • Assume a latent variable, Z, mediates between the explanators and the dummy variable Y. • The higher Z is, the higher the probability that Y = 1. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 76

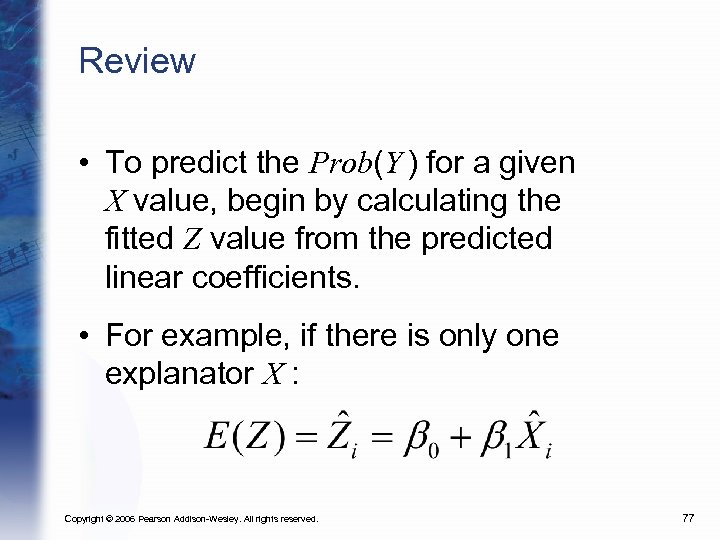

Review • To predict the Prob(Y ) for a given X value, begin by calculating the fitted Z value from the predicted linear coefficients. • For example, if there is only one explanator X : Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 77

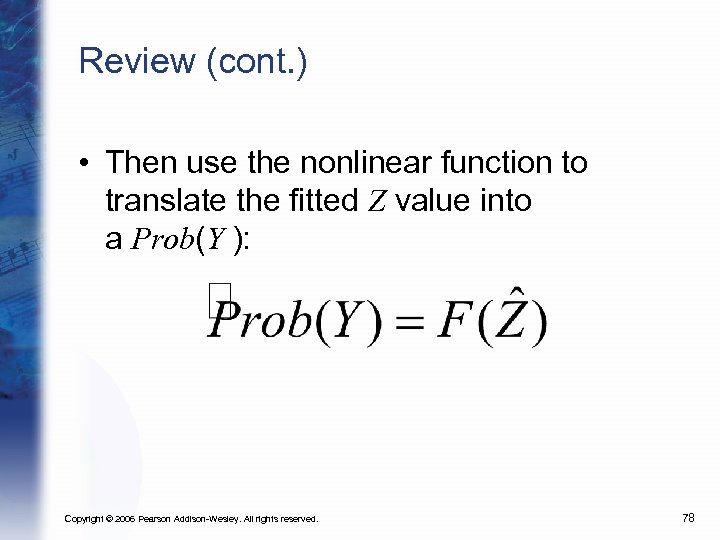

Review (cont. ) • Then use the nonlinear function to translate the fitted Z value into a Prob(Y ): Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 78

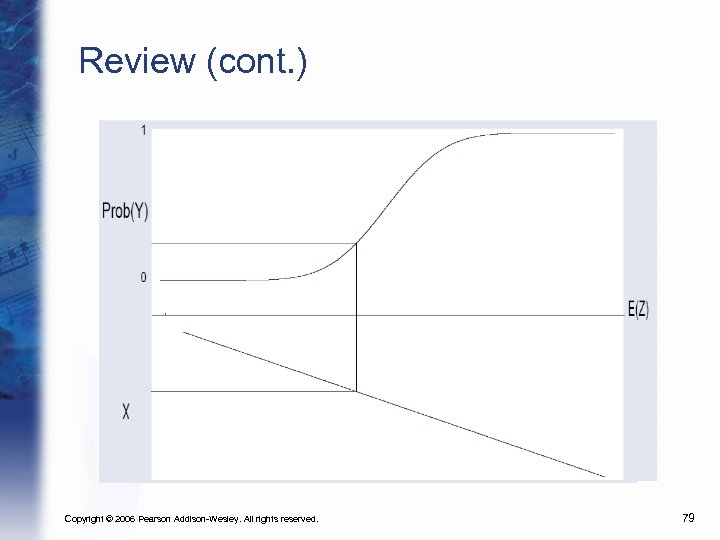

Review (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 79

Review (cont. ) • The estimated coefficients relate X to Z. • In interpreting the coefficients, look for: 1. Statistical significance: You can still read statistical significance from the slope d. Z/d. X. The z-statistic reported for probit or logit is analogous to OLS’s t-statistic. 2. Sign: If d. Z/d. X is positive, then d. Prob(Y )/d. X is also positive. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 80

Review (cont. ) 3. Magnitude: the magnitude of d. Z/d. X has no particular interpretation. We care about the magnitude of d. Prob(Y)/d. X. From the computer output for a probit or logit estimation, you can interpret the statistical significance and sign of each coefficient directly. Assessing magnitude is trickier. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 81

Review (cont. ) • Problems in Interpreting Magnitude: 1. The estimated coefficient relates X to Z. We care about the relationship between X and Prob(Y = 1). 2. The effect of X on Prob(Y = 1) varies depending on Z. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 82

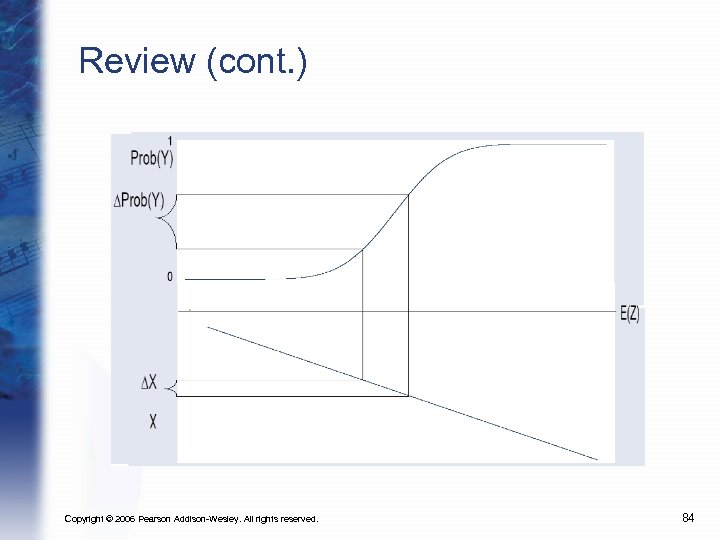

Review (cont. ) • There are two basic approaches to assessing the magnitude of the estimated coefficient. • One approach is to predict Prob(Y ) for different values of X, to see how the probability changes as X changes. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 83

Review (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 84

Review (cont. ) • The other approach is to use calculus. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 85

Review (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 86

Review (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 87

Review (cont. ) • We assume we know the distribution of ei. • In the probit model, we assume ei is distributed by the standard normal. • In the logit model, we assume ei is distributed by the logistic. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 88

Review (cont. ) 1. Calculate 2. Determine the regions of ei such that 3. Using the distribution of ei , calculate the probability of drawing an ei from each region. Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 89

Review (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 90

Review (cont. ) Copyright © 2006 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 91

a697cb8ad671f16c8fe9ef04a4de2947.ppt