2c5ebe2b417ffe31a64b91d4fe9c396a.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 25

Lecture 16 Oct 18 • Context-Free Languages (CFL) - basic definitions • Examples

Lecture 16 Oct 18 • Context-Free Languages (CFL) - basic definitions • Examples

Context-Free Languages (Ch. 2) Context-free languages allow us to describe non-regular languages like { 0 n 1 n | n 0} General idea: CFL’s are languages that can be recognized by automata that have one stack: { 0 n 1 n | n 0} is a CFL { 0 n 1 n 0 n | n 0} is not a CFL

Context-Free Languages (Ch. 2) Context-free languages allow us to describe non-regular languages like { 0 n 1 n | n 0} General idea: CFL’s are languages that can be recognized by automata that have one stack: { 0 n 1 n | n 0} is a CFL { 0 n 1 n 0 n | n 0} is not a CFL

Context-Free Grammars Start symbol S with rewrite rules: 1) S 0 S 1 2) S S yields 0 n 1 n : S 0 S 1 00 S 11 … 0 n. S 1 n 0 n 1 n

Context-Free Grammars Start symbol S with rewrite rules: 1) S 0 S 1 2) S S yields 0 n 1 n : S 0 S 1 00 S 11 … 0 n. S 1 n 0 n 1 n

Context-Free Grammars (Def. ) A context free grammar G=(V, , R, S) is defined by • V: a finite set variables (non-terminals) • : finite set terminals (with V = ) • R: finite set of substitution rules V (V )* • S: start symbol V The language of grammar G is denoted by L(G): L(G) = { w * | S * w }

Context-Free Grammars (Def. ) A context free grammar G=(V, , R, S) is defined by • V: a finite set variables (non-terminals) • : finite set terminals (with V = ) • R: finite set of substitution rules V (V )* • S: start symbol V The language of grammar G is denoted by L(G): L(G) = { w * | S * w }

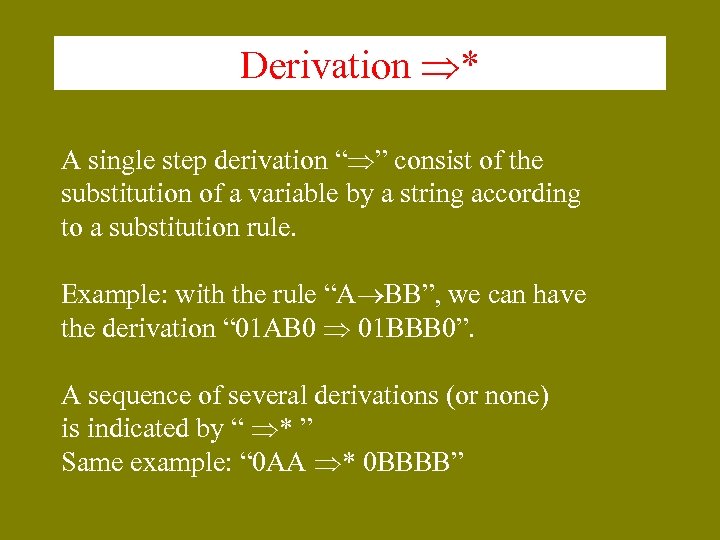

Derivation * A single step derivation “ ” consist of the substitution of a variable by a string according to a substitution rule. Example: with the rule “A BB”, we can have the derivation “ 01 AB 0 01 BBB 0”. A sequence of several derivations (or none) is indicated by “ * ” Same example: “ 0 AA * 0 BBBB”

Derivation * A single step derivation “ ” consist of the substitution of a variable by a string according to a substitution rule. Example: with the rule “A BB”, we can have the derivation “ 01 AB 0 01 BBB 0”. A sequence of several derivations (or none) is indicated by “ * ” Same example: “ 0 AA * 0 BBBB”

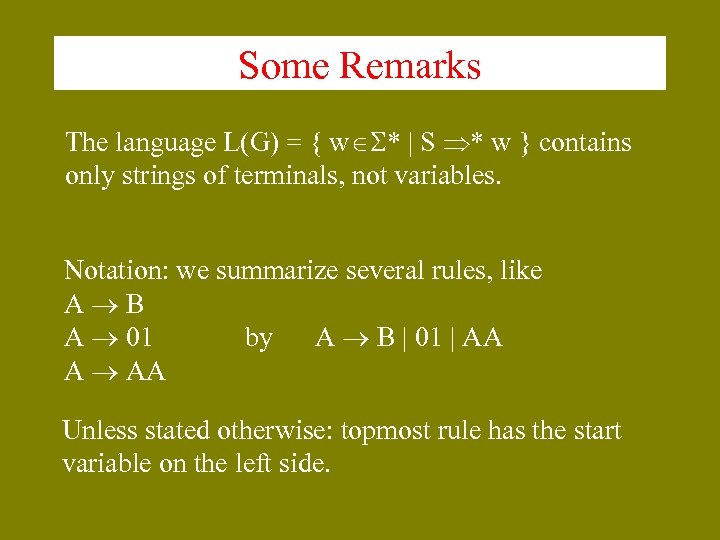

Some Remarks The language L(G) = { w * | S * w } contains only strings of terminals, not variables. Notation: we summarize several rules, like A B A 01 by A B | 01 | AA A AA Unless stated otherwise: topmost rule has the start variable on the left side.

Some Remarks The language L(G) = { w * | S * w } contains only strings of terminals, not variables. Notation: we summarize several rules, like A B A 01 by A B | 01 | AA A AA Unless stated otherwise: topmost rule has the start variable on the left side.

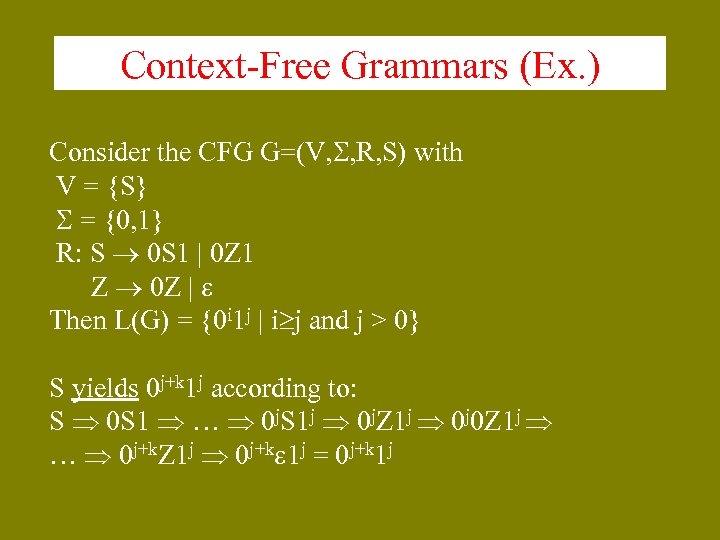

Context-Free Grammars (Ex. ) Consider the CFG G=(V, , R, S) with V = {S} = {0, 1} R: S 0 S 1 | 0 Z 1 Z 0 Z | Then L(G) = {0 i 1 j | i j and j > 0} S yields 0 j+k 1 j according to: S 0 S 1 … 0 j. S 1 j 0 j. Z 1 j 0 j 0 Z 1 j … 0 j+k. Z 1 j 0 j+k 1 j = 0 j+k 1 j

Context-Free Grammars (Ex. ) Consider the CFG G=(V, , R, S) with V = {S} = {0, 1} R: S 0 S 1 | 0 Z 1 Z 0 Z | Then L(G) = {0 i 1 j | i j and j > 0} S yields 0 j+k 1 j according to: S 0 S 1 … 0 j. S 1 j 0 j. Z 1 j 0 j 0 Z 1 j … 0 j+k. Z 1 j 0 j+k 1 j = 0 j+k 1 j

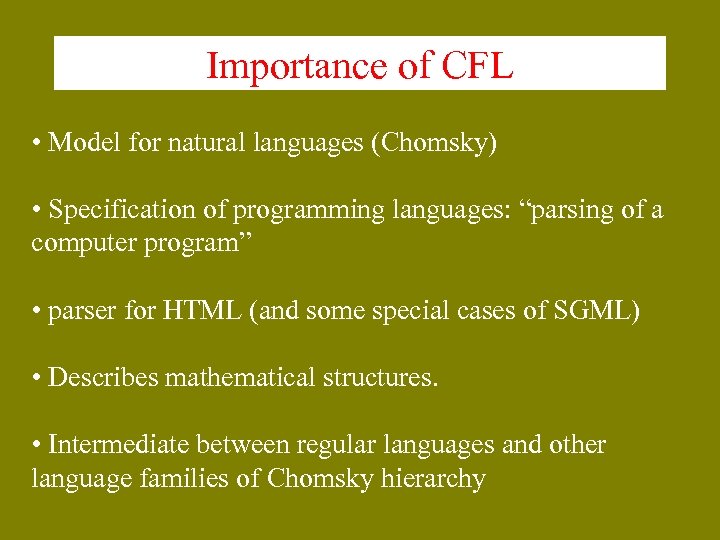

Importance of CFL • Model for natural languages (Chomsky) • Specification of programming languages: “parsing of a computer program” • parser for HTML (and some special cases of SGML) • Describes mathematical structures. • Intermediate between regular languages and other language families of Chomsky hierarchy

Importance of CFL • Model for natural languages (Chomsky) • Specification of programming languages: “parsing of a computer program” • parser for HTML (and some special cases of SGML) • Describes mathematical structures. • Intermediate between regular languages and other language families of Chomsky hierarchy

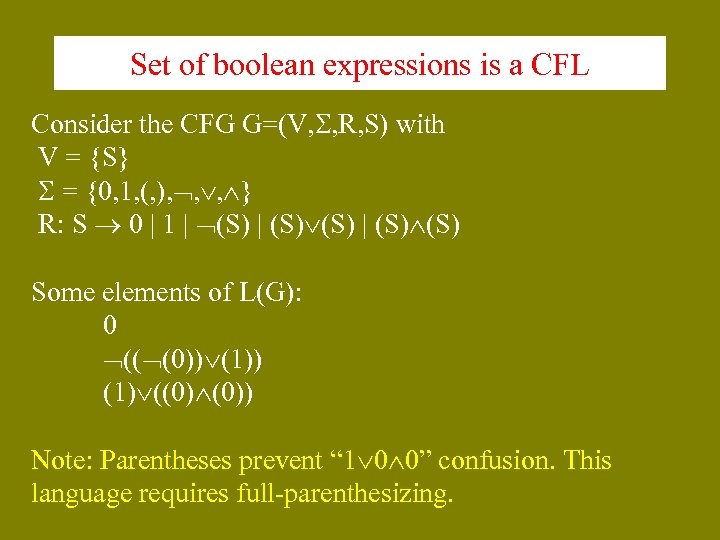

Set of boolean expressions is a CFL Consider the CFG G=(V, , R, S) with V = {S} = {0, 1, (, ), , , } R: S 0 | 1 | (S) (S) | (S) Some elements of L(G): 0 (( (0)) (1) ((0) (0)) Note: Parentheses prevent “ 1 0 0” confusion. This language requires full-parenthesizing.

Set of boolean expressions is a CFL Consider the CFG G=(V, , R, S) with V = {S} = {0, 1, (, ), , , } R: S 0 | 1 | (S) (S) | (S) Some elements of L(G): 0 (( (0)) (1) ((0) (0)) Note: Parentheses prevent “ 1 0 0” confusion. This language requires full-parenthesizing.

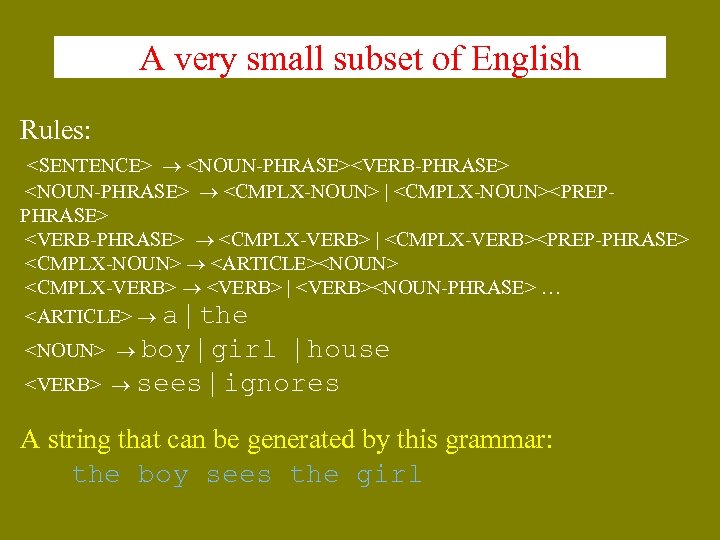

A very small subset of English Rules:

A very small subset of English Rules:

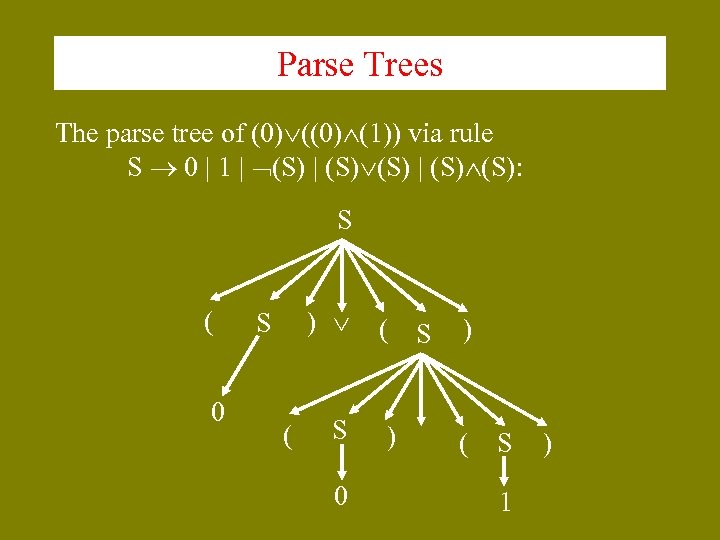

Parse Trees The parse tree of (0) (1)) via rule S 0 | 1 | (S) (S) | (S): S ( 0 ) S ( S 0 ( S ) ) ( S 1 )

Parse Trees The parse tree of (0) (1)) via rule S 0 | 1 | (S) (S) | (S): S ( 0 ) S ( S 0 ( S ) ) ( S 1 )

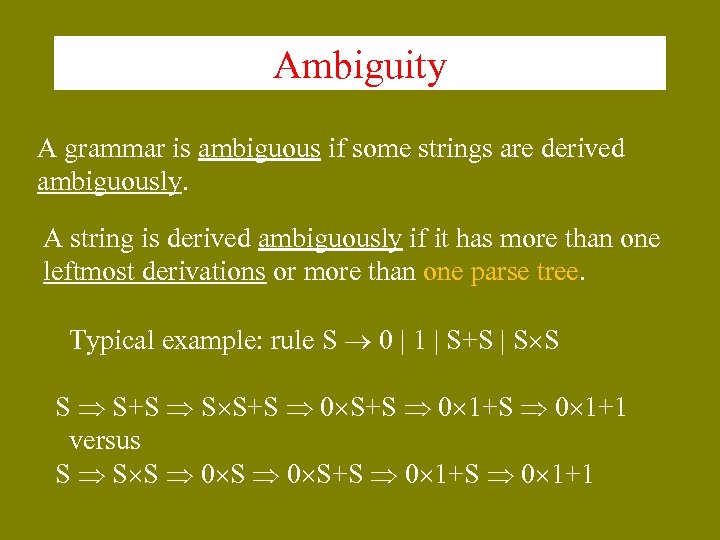

Ambiguity A grammar is ambiguous if some strings are derived ambiguously. A string is derived ambiguously if it has more than one leftmost derivations or more than one parse tree. Typical example: rule S 0 | 1 | S+S | S S S S+S S S+S 0 1+S 0 1+1 versus S S S 0 S+S 0 1+1

Ambiguity A grammar is ambiguous if some strings are derived ambiguously. A string is derived ambiguously if it has more than one leftmost derivations or more than one parse tree. Typical example: rule S 0 | 1 | S+S | S S S S+S S S+S 0 1+S 0 1+1 versus S S S 0 S+S 0 1+1

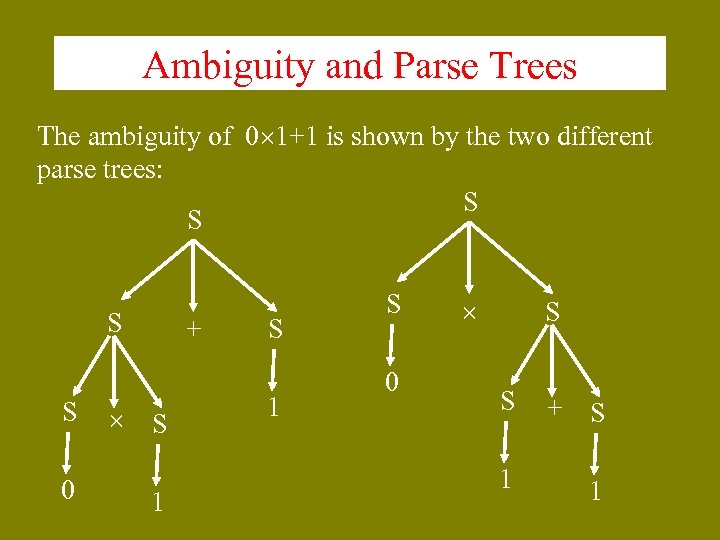

Ambiguity and Parse Trees The ambiguity of 0 1+1 is shown by the two different parse trees: S S 0 + S 1 S 0 S S + S 1 1

Ambiguity and Parse Trees The ambiguity of 0 1+1 is shown by the two different parse trees: S S 0 + S 1 S 0 S S + S 1 1

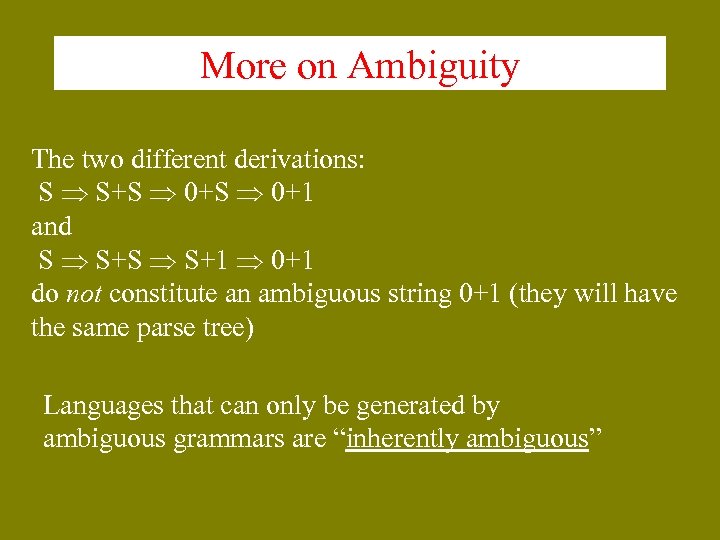

More on Ambiguity The two different derivations: S S+S 0+1 and S S+1 0+1 do not constitute an ambiguous string 0+1 (they will have the same parse tree) Languages that can only be generated by ambiguous grammars are “inherently ambiguous”

More on Ambiguity The two different derivations: S S+S 0+1 and S S+1 0+1 do not constitute an ambiguous string 0+1 (they will have the same parse tree) Languages that can only be generated by ambiguous grammars are “inherently ambiguous”

Context-Free Languages Any language that can be generated by a context free grammar is a context-free language (CFL). The CFL { 0 n 1 n | n 0 } shows us that certain CFLs are nonregular languages. Q 1: Are all regular languages context free? Q 2: Which languages are outside the class CFL?

Context-Free Languages Any language that can be generated by a context free grammar is a context-free language (CFL). The CFL { 0 n 1 n | n 0 } shows us that certain CFLs are nonregular languages. Q 1: Are all regular languages context free? Q 2: Which languages are outside the class CFL?

Example. A context-free grammar for the set of strings over {0, 1} with an equal number of 0’s and 1’s. We need a grammar for the language L = { w | w has an equal number of 0’s and 1’s} Consider the grammar: S 0 S 1|1 S 0| This does not cover all the strings. Exhibit a string in L that is not generated by G.

Example. A context-free grammar for the set of strings over {0, 1} with an equal number of 0’s and 1’s. We need a grammar for the language L = { w | w has an equal number of 0’s and 1’s} Consider the grammar: S 0 S 1|1 S 0| This does not cover all the strings. Exhibit a string in L that is not generated by G.

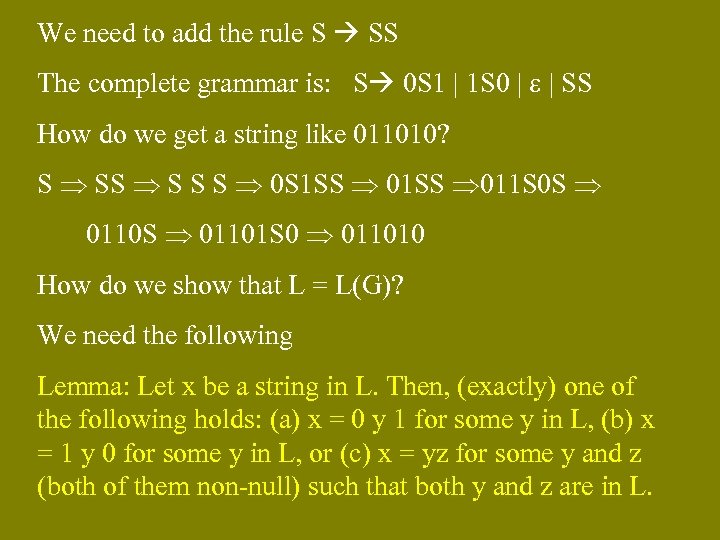

We need to add the rule S SS The complete grammar is: S 0 S 1 | 1 S 0 | | SS How do we get a string like 011010? S S S S 0 S 1 SS 01 SS 011 S 0 S 01101 S 0 011010 How do we show that L = L(G)? We need the following Lemma: Let x be a string in L. Then, (exactly) one of the following holds: (a) x = 0 y 1 for some y in L, (b) x = 1 y 0 for some y in L, or (c) x = yz for some y and z (both of them non-null) such that both y and z are in L.

We need to add the rule S SS The complete grammar is: S 0 S 1 | 1 S 0 | | SS How do we get a string like 011010? S S S S 0 S 1 SS 01 SS 011 S 0 S 01101 S 0 011010 How do we show that L = L(G)? We need the following Lemma: Let x be a string in L. Then, (exactly) one of the following holds: (a) x = 0 y 1 for some y in L, (b) x = 1 y 0 for some y in L, or (c) x = yz for some y and z (both of them non-null) such that both y and z are in L.

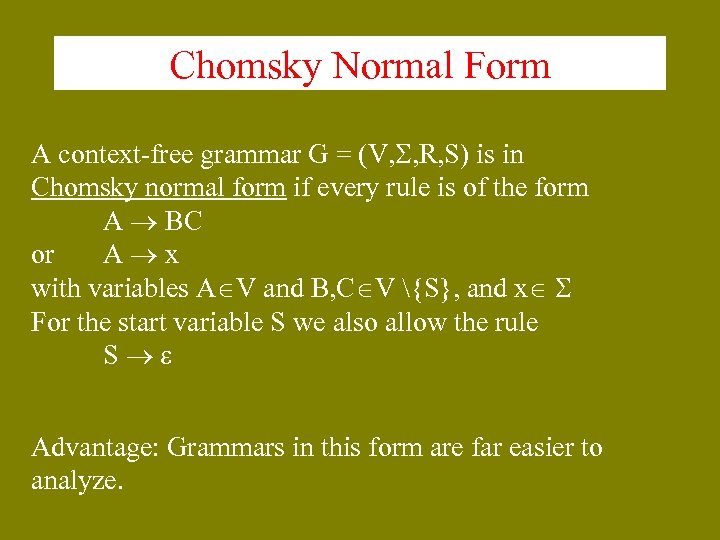

Chomsky Normal Form A context-free grammar G = (V, , R, S) is in Chomsky normal form if every rule is of the form A BC or A x with variables A V and B, C V {S}, and x For the start variable S we also allow the rule S Advantage: Grammars in this form are far easier to analyze.

Chomsky Normal Form A context-free grammar G = (V, , R, S) is in Chomsky normal form if every rule is of the form A BC or A x with variables A V and B, C V {S}, and x For the start variable S we also allow the rule S Advantage: Grammars in this form are far easier to analyze.

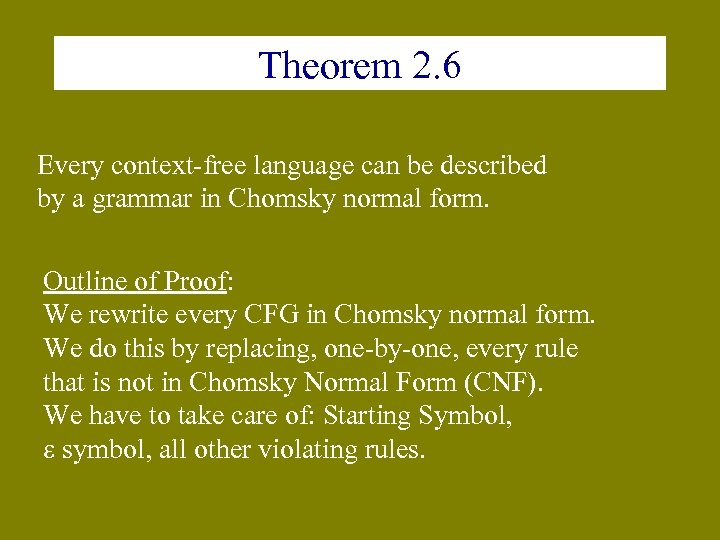

Theorem 2. 6 Every context-free language can be described by a grammar in Chomsky normal form. Outline of Proof: We rewrite every CFG in Chomsky normal form. We do this by replacing, one-by-one, every rule that is not in Chomsky Normal Form (CNF). We have to take care of: Starting Symbol, symbol, all other violating rules.

Theorem 2. 6 Every context-free language can be described by a grammar in Chomsky normal form. Outline of Proof: We rewrite every CFG in Chomsky normal form. We do this by replacing, one-by-one, every rule that is not in Chomsky Normal Form (CNF). We have to take care of: Starting Symbol, symbol, all other violating rules.

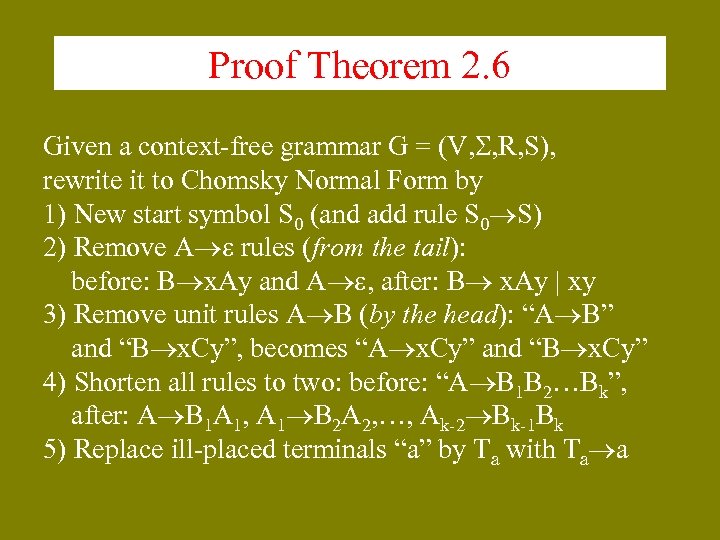

Proof Theorem 2. 6 Given a context-free grammar G = (V, , R, S), rewrite it to Chomsky Normal Form by 1) New start symbol S 0 (and add rule S 0 S) 2) Remove A rules (from the tail): before: B x. Ay and A , after: B x. Ay | xy 3) Remove unit rules A B (by the head): “A B” and “B x. Cy”, becomes “A x. Cy” and “B x. Cy” 4) Shorten all rules to two: before: “A B 1 B 2…Bk”, after: A B 1 A 1, A 1 B 2 A 2, …, Ak-2 Bk-1 Bk 5) Replace ill-placed terminals “a” by Ta with Ta a

Proof Theorem 2. 6 Given a context-free grammar G = (V, , R, S), rewrite it to Chomsky Normal Form by 1) New start symbol S 0 (and add rule S 0 S) 2) Remove A rules (from the tail): before: B x. Ay and A , after: B x. Ay | xy 3) Remove unit rules A B (by the head): “A B” and “B x. Cy”, becomes “A x. Cy” and “B x. Cy” 4) Shorten all rules to two: before: “A B 1 B 2…Bk”, after: A B 1 A 1, A 1 B 2 A 2, …, Ak-2 Bk-1 Bk 5) Replace ill-placed terminals “a” by Ta with Ta a

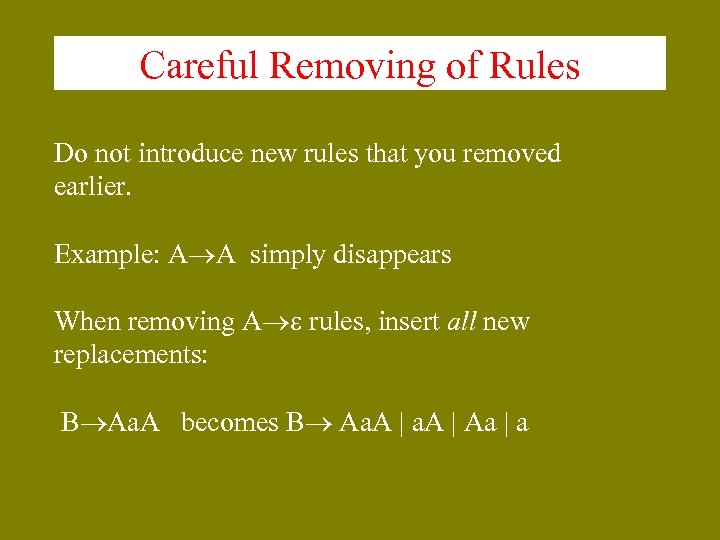

Careful Removing of Rules Do not introduce new rules that you removed earlier. Example: A A simply disappears When removing A rules, insert all new replacements: B Aa. A becomes B Aa. A | Aa | a

Careful Removing of Rules Do not introduce new rules that you removed earlier. Example: A A simply disappears When removing A rules, insert all new replacements: B Aa. A becomes B Aa. A | Aa | a

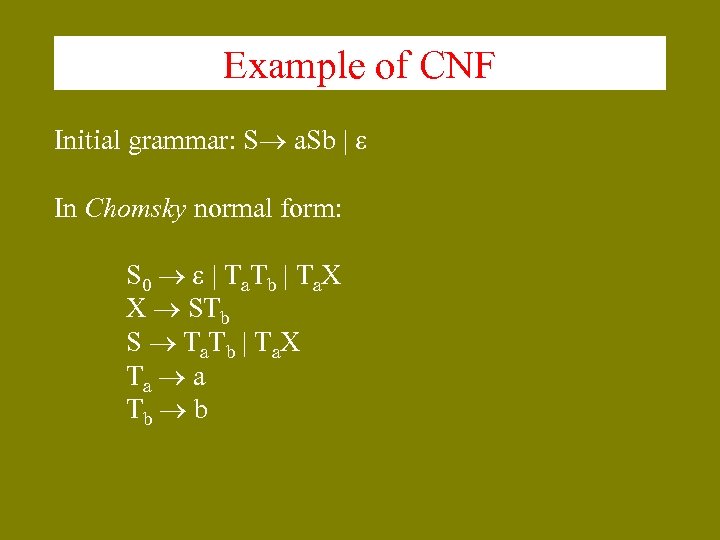

Example of CNF Initial grammar: S a. Sb | In Chomsky normal form: S 0 | T a T b | T a X X STb S T a. T b | T a. X Ta a Tb b

Example of CNF Initial grammar: S a. Sb | In Chomsky normal form: S 0 | T a T b | T a X X STb S T a. T b | T a. X Ta a Tb b

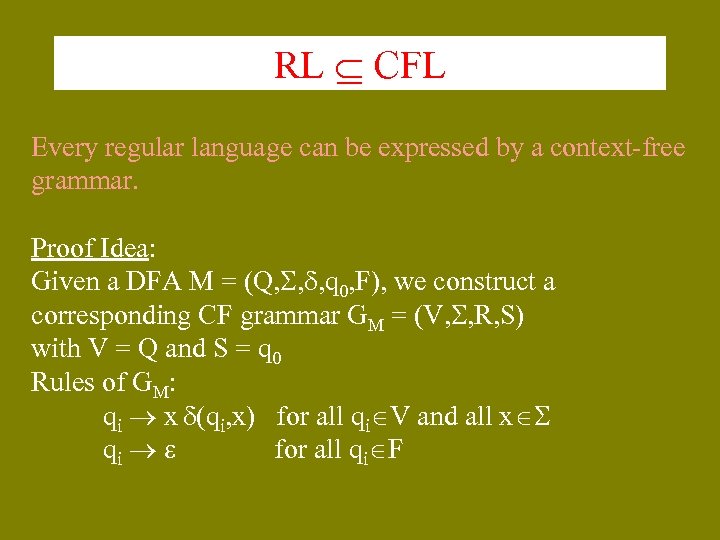

RL CFL Every regular language can be expressed by a context-free grammar. Proof Idea: Given a DFA M = (Q, , , q 0, F), we construct a corresponding CF grammar GM = (V, , R, S) with V = Q and S = q 0 Rules of GM: qi x (qi, x) for all qi V and all x qi for all qi F

RL CFL Every regular language can be expressed by a context-free grammar. Proof Idea: Given a DFA M = (Q, , , q 0, F), we construct a corresponding CF grammar GM = (V, , R, S) with V = Q and S = q 0 Rules of GM: qi x (qi, x) for all qi V and all x qi for all qi F

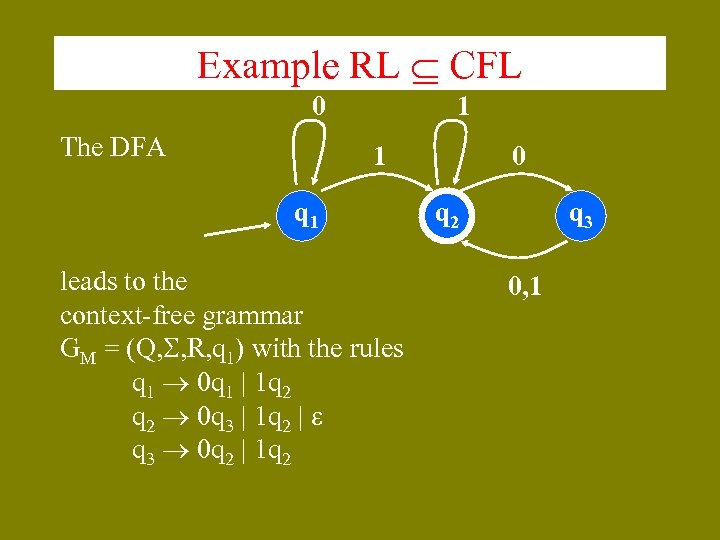

Example RL CFL 0 The DFA 1 1 q 1 leads to the context-free grammar GM = (Q, , R, q 1) with the rules q 1 0 q 1 | 1 q 2 0 q 3 | 1 q 2 | q 3 0 q 2 | 1 q 2 0 q 2 q 3 0, 1

Example RL CFL 0 The DFA 1 1 q 1 leads to the context-free grammar GM = (Q, , R, q 1) with the rules q 1 0 q 1 | 1 q 2 0 q 3 | 1 q 2 | q 3 0 q 2 | 1 q 2 0 q 2 q 3 0, 1

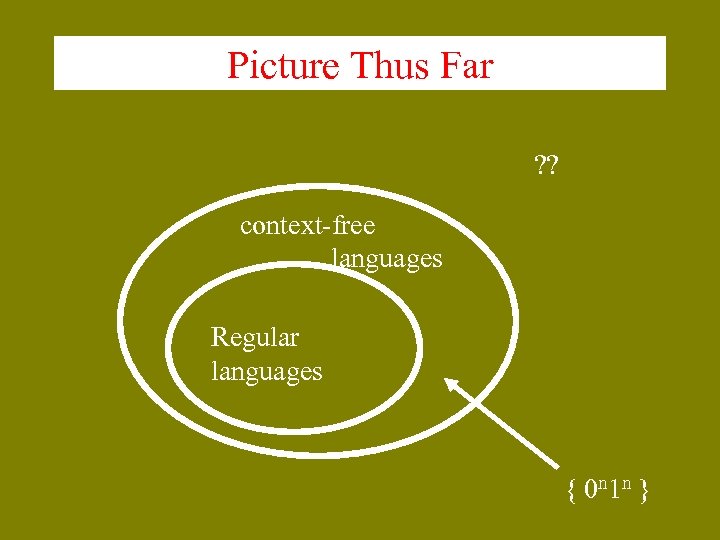

Picture Thus Far ? ? context-free languages Regular languages { 0 n 1 n }

Picture Thus Far ? ? context-free languages Regular languages { 0 n 1 n }