0e8e6da81118523e23136168a8bddefc.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 75

Lecture 13 Adaptation Theory Literary Translation

Brian Friel Translations 1980

Brian Friel Irish playwright was born in Killyclogher, Co. Tyrone, Northern Ireland, 1929, died in Greencastle, Co. Donegal, Republic of Ireland, 2015. He was born into a recently partitioned country that was further divided along sectarian lines.

Brian Friel (1929– 2015) Background and Literary Career Born into a Catholic family living in a predominantly Protestant constituency. Parents wanted to avoid difficulty with the authorities of registering a Gaelic name (Brian), so an Anglicised version (Bernard) was adopted. He was translated into English right at his birth. • the ritual of naming – key to individual and national identity • the problem of communication between cultures – major issue addressed in Translations

Translations and its companion piece, Making History were the first and last plays to be produced by the Field Day Theatre Company that Brian Friel founded with the actor Stephen Rae in 1980; the company was a cross-border initiative financed by the Arts Council of both Northern Ireland the Republic of Ireland which aimed to reach a broad constituency across the country

Translations The plot is set in 1833 in a small community in Baile Beag, (later anglicized to Ballybeg), in an Irish speaking community in County Donegal. The British Army are making the first Ordnance Survey map of Ireland, Anglicising all the Irish names, and the National School are being established to impose English as the national language

Translations General Summary Translations is a three-act play by Brian Friel written in 1980. It is set in Baile Beag (Ballybeg), a small village in 19 th century agricultural Ireland. Friel has said that Translations is "a play about language and only about language", but it deals with a wide range of issues, stretching from language and communication to Irish history and cultural imperialism. Despite the 1833 setting, there are obvious parallels between Baile Beag and today's world.

Plot The scene is set in a hedge school. (A hedge school (Irish names include scoil chois claí, scoil ghairid and scoil scairte) is the name given to an educational practice in 19 th century Ireland, so called due to its rural nature. It came about as local educated men began an oral tradition of teaching the community. Hedge schools declined from the foundation of the National School system by government in the 1830 s. )

Hedge School While the "hedge school" label suggests the classes always took place out-doors (by a hedgerow), classes were more regularly held in a house or barn. Subjects included primarily basic grammar, English and maths. In some schools the Irish bardic tradition, Latin, history and home economics were also taught. Hedge schools declined from the foundation of the National School system by government in the 1830 s. Yet Hedge schools existed into the 1890 s,

Plot cont. Hugh, the alcoholic master at the school is hoping to get an appointment at the new national school (but eventually does not get it). He is away to baptize a newborn babe. In his absence, his son, Manus substitutes him. He manages to teach Sarah, a mute girl to pronounce her name.

Plot cont. The action begins with Owen, younger son of the schoolmaster Hugh and brother to Manus returning home after six years away in Dublin. He accompanies Captain Lancey, a middle-aged, pragmatic cartographer, and Lieutenant Yolland, a young, romantic orthographer. Owen acts as a translator for the British and Irish. However, his translation is always selective, deliberately mistranslates the speech of Captain Lancey so that locals might not know exactly what was going on.

Translations Act One OWEN: And I'll translate as you go along. LANCEY: I see. Yes. Very well. Perhaps you're right. Well. What we are doing is this. (He looks at OWEN nods reassuringly. ) His Majesty's government has ordered the first ever comprehensive survey of this entire country – a general triangulation which will embrace detailed hydrographic and topographic information and which will be executed to a scale of six inches to the English mile. HUGH: (Pouring a drink) Excellent-excellent. (LANCEY looks at OWEN. ) OWEN: A new map is being made of the whole country. (LANCEY looks to OWEN: Is that all? OWEN smiles reassuringly and indicates to proceed. )

Translations Act One, cont. LANCEY: This enormous task has been embarked on so that the military authorities will be equipped with up-todate and accurate information on every corner of this part of the Empire. OWEN: The job is being done by soldiers because they are skilled in this work. LANCEY: And also so that the entire basis of land valuation can be reassessed for purposes of more equitable taxation. OWEN: This new map will take the place of the estate agent's map so that from now on you will know exactly what is yours in law.

Translations Act One, cont. LANCEY: In conclusion I wish to quote two brief extracts from the white paper which is our governing charter: (Reads) 'All former surveys of Ireland originated in forfeiture and violent transfer of property; the present survey has for its object the relief which can be afforded to the proprietors and occupiers of land from unequal taxation. OWEN: The captain hopes that the public will cooperate with the sappers and that the new map will mean that taxes are reduced. HUGH: A worthy enterprise – opus honestum! And Extract B? LANCEY: 'Ireland is privileged. No such survey is being undertaken in England. So this survey cannot but be received as proof of the disposition of this government to advance the interests of lreland. ' My sentiments, too.

Translations Act One, cont. OWEN: This survey demonstrates the government's interest in Ireland the captain thanks you for listening so attentively to him. HUGH: Our pleasure, Captain. LANCEY : Lieutenant Yolland? YOLLAND: I – I've nothing to say – really – OWEN: The captain is the man who actually makes the new map. George's task is to see that the placenames on this map are. . . correct. (To Y 0 LLAND. ) Just a few words-they'd like to hear you. (To class. ) Don't you want to hear George, too? MAIRE: Has he anything to say?

Translations Act One, cont. YOLLAND: (To MAIRE) Sorry – sorry? OWEN: She says she's dying to hear you. YOLLAND: (To MAIRE) Very kind of you – thank you. . . (To class) I can only say that I feel – I feel very foolish to – to be working here and not to speak your language. But I intend to rectify that – with Roland's help – indeed I do. OWEN: He wants me to teach him Irish! HUGH: You are doubly welcome, sir. YOLLAND: I think your countryside is –is– is very beautiful. I've fallen in love with it already. I hope we're not too – too crude an intrusion on your lives. And I know that I'm going to be happy, very happy, here.

Translations Act One, cont. OWEN: He is already a committed Hibernophile – JIMMY: He loves – OWEN: All right, Jimmy – we know – he loves Baile Beag; and he loves you all. HUGH: Please. . . May I. . . ? (HUGH is now drunk. He holds on to the edge of the table. ) OWEN: Go ahead, Father. (Hands up for quiet. ) Please – please. HUGH: And we, gentlemen, we in turn are happy to offer you our friendship, our hospitality, and every assistance that you may require. Gentlemen – welcome!

Translations Act One, cont. (A few desultory claps. The formalities are over. General conversation. The soldiers meet the locals. MANUS and OWEN meet down stage. ) OWEN: Lancey's a bloody ramrod but George's all right. How are you anyway? MANUS: What sort of a translation was that, Owen? OWEN: Did I make a mess of it? MANUS: You weren't saying what Lancey was saying! OWEN: 'Uncertainty in meaning is incipient poetry' – who said that? MANUS: There was nothing uncertain about what Lancey said: it's a bloody military operation, Owen! And what's Yolland's function? What's 'incorrect' about the placenames we have here?

Translations Act One, cont. OWEN: Nothing at all. They're just going to be standardized. MANUS: You mean changed into English?

Plot cont. Yolland Owen work to translate local placenames into English for purposes of the first ordnance survey map of Ireland. Owen has no reservations about anglicizing the names of places that form part of his heritage, yet Yolland, fallen in love with Ireland, is uneasy about it.

Plot cont. There develops a love triangle between Yolland, Manus, and a local girl, Maire insists on the necessity of learning English as a way of escape (she wishes to emigrate to America). Yolland, speaking only English, and Maire, speaking only Irish, transgress linguistic obstacles and express their feelings for each other. They ‘leap across the ditch’, i. e. they leap across the tribal and class boundaries, communicating their love through place-names. But the local Irish girl in the arms of a British soldier is a romantic but also shocking image suggesting conquest, collaboration, colonisation.

Plot cont. Manus who was hoping to marry Maire, gets jealous and plans to attack Yolland. But in the end he is unable to set up his mind to perpetrate it. Unfortunately, Yolland goes missing. He has been attacked by rebellious locals, so Manus has to escape. The British soldiers rampage across Baile Beag, and Captain Lancey threatens first shooting all livestock and then evicting and destroying houses if Yolland is not found.

Plot cont. Hugh does not get the appointment Nellie Ruadh’s baby, baptised at the beginning of the play, dies. The play ends ambiguously yet forebodingly.

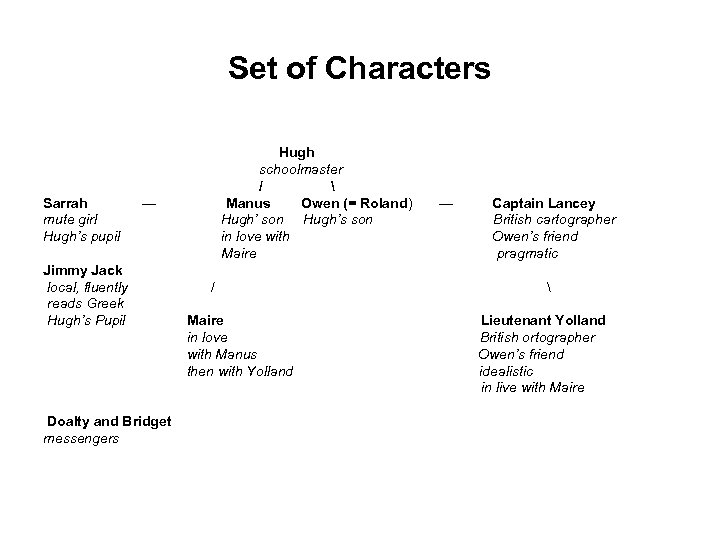

Set of Characters Sarrah mute girl Hugh’s pupil Hugh schoolmaster / — Manus Owen (= Roland) — Captain Lancey Hugh’ son Hugh’s son British cartographer in love with Owen’s friend Maire pragmatic Jimmy Jack local, fluently reads Greek Hugh’s Pupil Doalty and Bridget messengers / Maire in love with Manus then with Yolland Lieutenant Yolland British ortographer Owen’s friend idealistic in live with Maire

Translation There are different forms of translation in the play (1) From one language to another: from Irish into English and English into Irish, from Greek and Latin into Irish and English (2) Between two worlds, two cultures, two privacies (3) Other forms of translation relate to the interpretation of facts, historical or individual Hugh: ‘We must learn those new names … we must learn where we live. We must learn to make them our own. We must make them our new home. ”

Translations Theme • The play is about language – the death of Irish language and the implicit loss of cultural and national identity. • The historical moment brings irreversible change for Baile Beag and the whole of Ireland. It explores notions of naming and translation. • The theme is personalised through the experience of the people in Baile Beag and in particular the O’Donnel family: Hugh, father and schoolmaster Manus, eldest son and scholar Owen, the ‘exiled’ younger son, who returns as a translator for the British Army

Translations Theme • The cultural climate of Baile Beag is a dying climate. The representatives of the community are dumb, lame, alcoholic. Physical maiming is the representation of their spiritual deprivation. • It portrays an Irish-speaking community – devises a theatrical conceit by which even though the actors speak English, the audience will assume or accept that they are speaking Irish.

Language For the British – power For the Irish – a form of romantic evasion (into mythologies of fantasy, hope and self-deception) The audience is reminded many times that the Irish characters are speaking Gaelic, e. g. Lancey asks Owen if the hedge-school pupils speak any English, Maire and Yolland have great difficulty in communicating with each other, Owen translates between Lancey and the community.

Language cont. • Hugh, Manus, Owen, Jimmy are fluent in Greek and Latin • Through these languages they keep in touch with ancient civilizations • For Hugh, Manus, and Jimmy these languages are not dead, they are part of their daily lives, but their knowledge will not equip these scholars to deal with the changing reality of the world • For them Irish is also a living thing, but for the outside world it is effectively dead or dying • Yet the establishment of English as the first language in Ireland is seen as inevitable and by many as a good thing

Language cont. • Language is the means by which the British Army rapes the land, one culture penetrates the other • Owen translates Irish place-names into English, towards the end of the play Lancey inverts the case, ordering Owen to translate from English into Irish so that locals which of their townlands are under threat of extinction

Naming • Name and identity are synonymous throughout the play • Sarah, the mute girl is carefully taught by Manus her own name, thus being able to articulate herself, thus being given an identity; her first words are those of personal identification, but eventually she retreats back into silence, into the loss of identity, which is precisely what happens to Ireland • Owen, when returns home, is called Roland by the British soldiers, but eventually insists that his name is Owen and not Roland

Naming cont. • The play starts with a christening which Hugh calls the ritual of naming • All the Irish characters are referred to by their Christian names, suggesting a degree of familiarity • English are referred to by their surnames, distancing them from the audience

Irony • Irony is the chief dramatic method which runs throughout the play. • The greatest irony of all is that all the Irish characters are obliged to speak in English to be understood by an audience, including an Irish one.

Bellybeg / Baile Beag The majority of Friel’s plays are set in Donegal in a mythical place called Bellybeg, which is a generic name given to small Irish towns. Friel's Ballybeg has often been compared to the village of Glenties, close to where the playwright lives. The name comes from the Gaelic words Baile Beag which literally means ‘small town’. The term is originated in France (bailie being the Old French term for a bailiff, see Bailiwick).

Bellybeg / Baile Beag Baile also means ‘home’; so Baile Beag indicates some sort of a cohesive community. But the name can be interpreted in the pejorative sense of a rigid and conservative mindset.

Ballybeg may also refer to: • Ballybeg, County Waterford, the name of a working class suburb of Waterford, Ireland • Ballybeg, County Wicklow, a small village in County Wicklow, Ireland • Ballybeg, County Antrim, a townland in County Antrim, Northern Ireland • Ballybeg, County Down, a townland in County Down, Northern Ireland • Ballybeg, County Carlow, a townland in County Carlow, Ireland • Ballybeg, small road between Portglenone and Ahoghill in County Antrim, Northern Ireland.

Three historical perspectives Events referred to in the past which affected the relationship between Ireland Britain. Contemporary audience was indirectly reminded of then current political issues. In the decade that preceded the première of the play, internment without trial was introduced. The event known as Bloody Sunday occurred in Derry. Secterian killings, Protestant strikes, UDA atrocities, IRA bombing, the Prevention Terrorism Act, hunger strikes in Belfast in protest against inhuman and degrading treatment of prisoners were part of the turbulent period which is called ‘troubles’.

Bloody Sunday (Irish: Domhnach na Fola) Sometimes called the Bogside Massacre—was an incident on 30 January 1972 in the Bogside area of Derry, Northern Ireland, in which twenty-six unarmed civil rights protesters and bystanders were shot by oldiers of the British Army. Thirteen males, seven of whom were teenagers, died immediately or soon after, while the death of another man four and a half months later has been attributed to the injuries he received on that day. The incident occurred during a Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association march; the soldiers involved were the First Battalion of the Parachute Regiment.

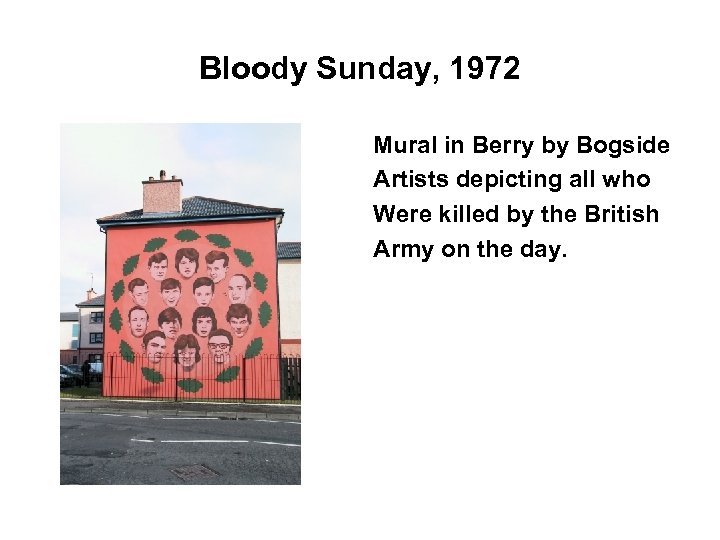

Bloody Sunday, 1972 Mural in Berry by Bogside Artists depicting all who Were killed by the British Army on the day.

Conclusion Translations raises a lot more questions than it answers. The legacy of the relationship between Britain and Ireland remains unresolved. The play provides the audience with the critical perspective to see how the historical process is working and what questions to ask of it. The play is about the death of a language which still remains vibrant and alive. It also problematizes the connection between language and national identity.

Sources Friel, Brian: ”Translations. ” In: Brian Friel: Plays 1. London: Faber and Faber, 1996, 377 -451 Jones, Nesta: ”Translations. ” In: Jones, Nesta: A Faber Critical Guide: Brian Friel. London: Faber and Faber, 2000, 57 -116 Pelletier, Martine: “Translations, the Field Day debate and the re-imagining of Irish identity. ” In: Roche, Anthony, ed. : The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006, 66 -77

Translation Studies See: http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Translation_studies Translation studies is an interdiscipline containing elements of social science and the humanities, dealing with the systematic study of theory, the description and the application of translation, interpreting or both these activities. Translation studies can be normative (prescribing rules for the application of these activities) or descriptive.

Translation Studies See: http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Translation_studies As an interdisciplinary discipline, translation studies borrows much from the different fields of study that support translation. These include comparative literature, computer science, history, linguistics, philology, philosophy, semiotics, terminology, and so forth. Note that occasionally in English writers will use the term translatology to refer to translation studies.

Translation Studies Basnett, Susan: “Literary Research and Translation. ” In: da Sousa Correa, Della; Owens, W. R. , eds. : The Handbook to Literary Research. London, New York: Routledge, 2010, 167 -183 ’Cultural translation’ - expanding the idea of translation as linguistic transfer to describe the processes and the condition of the global migration and exchange.

Translation Studies Globalisation Global mobility – mass movement of people, movement of capital, commodities, information, and images Intercultural communication Not a marginal literary activity – has been a major shaping force in literary and cultural history, a means of bringing in in new forms, genres and ideas

Translation Studies Translation as linguistic process An ancient form of textual practice The transposition of a text that has come into being in one context into a different one The process involves reshaping and rewriting the text Negotiation between the original, the source and its destination, the target

Translation Studies See: http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Translation_studies CULTURAL TRANSLATION is a new area of interest in the field of translation studies. Cultural translation is a concept used in cultural studies to denote the process of transformation, linguistic or otherwise, in a given culture. The concept uses linguistic translation as a tool or metaphor in analysing the nature of transformation in cultures. For example, ethnography is considered a translated narrative of an abstract living culture.

Translation Studies Cultural Translation Continually reminds the reader of difference. A text produced for one set of readers is rendered to a different set of readers with different expectations, aesthetic concepts, embedded in different cultural Context. The translator has to take into account not only the linguistic dimensions but the problem of diverse layers of meaning in the different cultural contexts

George Steiner (1975, 1992)

Understanding As Translation ‚Any model of communication is at the same time is model of trans-lation, of vertical or horizontal transfer of significance. ’ Understanding is translation

Translation Studies Question of equivalence No translation is identical with the original Literal, word to word translation – is it possible? Restructuring another author’s work – to what extent is it ethical?

Translation Studies The emphasis is on what the text is destined to do for the readers for whom it is intended Can meaning remain unchanged? Is meaning culturally and thus linguistically determined?

Translation Studies Shift from source-oriented theories to target-oriented theories The shift includes cultural factors Translation as intercultural and transnational communication An act of disruption and repositioning the subject in the world and history

Translation Studies Ancient text brought to contemporary readers This is how the writer would have written had she/he been writing now The translator introduces an alternative existence, a “might have been” or “is yet to come” into the substance or historical condition of one’s own language

Translation Studies Technical aspect versus cultural aspects How to translate regional and social dialects? Cockney English, Yorkshire accent, Hiberno-English, working-class language usage, Black American slang, 18 th century sailors’ jargon, Loiner skinhead talk, etc.

Translation Studies Translating ancient texts into modern To archaize or to modernize To historicize or to contemporize Ancient texts brought to contemporary readers – to show an ancient work would have been written had its author lived now

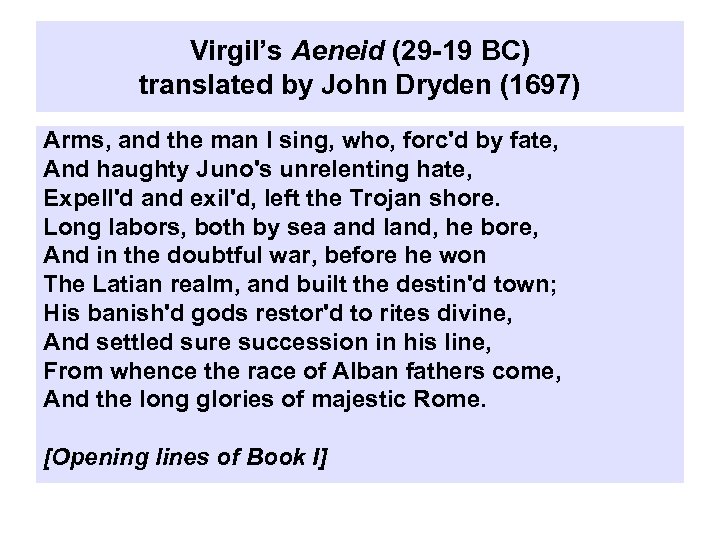

Virgil’s Aeneid (29 -19 BC) translated by John Dryden (1697) Arms, and the man I sing, who, forc'd by fate, And haughty Juno's unrelenting hate, Expell'd and exil'd, left the Trojan shore. Long labors, both by sea and land, he bore, And in the doubtful war, before he won The Latian realm, and built the destin'd town; His banish'd gods restor'd to rites divine, And settled sure succession in his line, From whence the race of Alban fathers come, And the long glories of majestic Rome. [Opening lines of Book I]

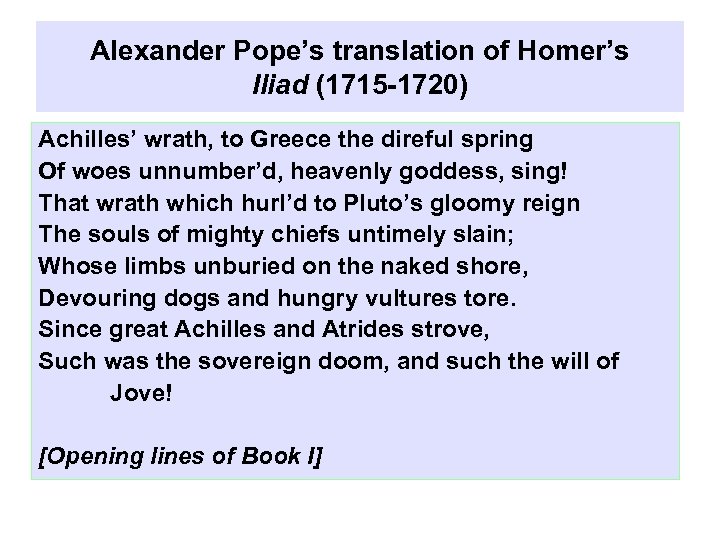

Alexander Pope’s translation of Homer’s Iliad (1715 -1720) Achilles’ wrath, to Greece the direful spring Of woes unnumber’d, heavenly goddess, sing! That wrath which hurl’d to Pluto’s gloomy reign The souls of mighty chiefs untimely slain; Whose limbs unburied on the naked shore, Devouring dogs and hungry vultures tore. Since great Achilles and Atrides strove, Such was the sovereign doom, and such the will of Jove! [Opening lines of Book I]

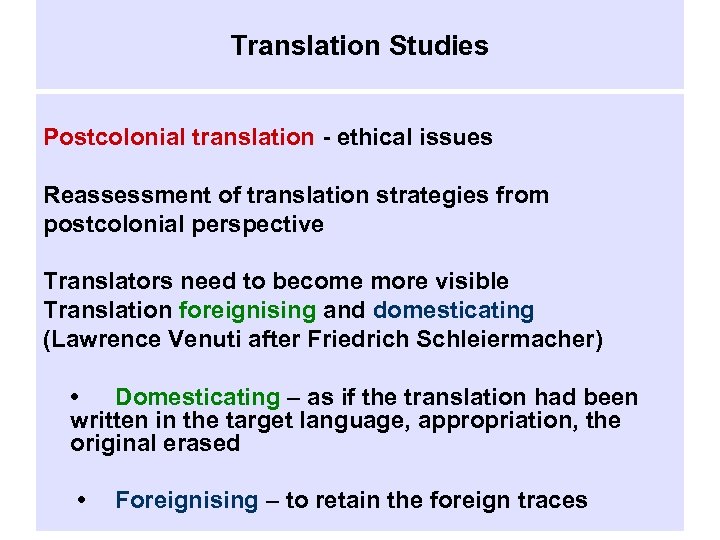

Translation Studies Postcolonial translation - ethical issues Reassessment of translation strategies from postcolonial perspective Translators need to become more visible Translation foreignising and domesticating (Lawrence Venuti after Friedrich Schleiermacher) • Domesticating – as if the translation had been written in the target language, appropriation, the original erased • Foreignising – to retain the foreign traces

Translation Studies Writing and translating are twin processes, engaged in constant interaction Crossing linguistic and cultural/national boundaries through translation Translation as reconciliation

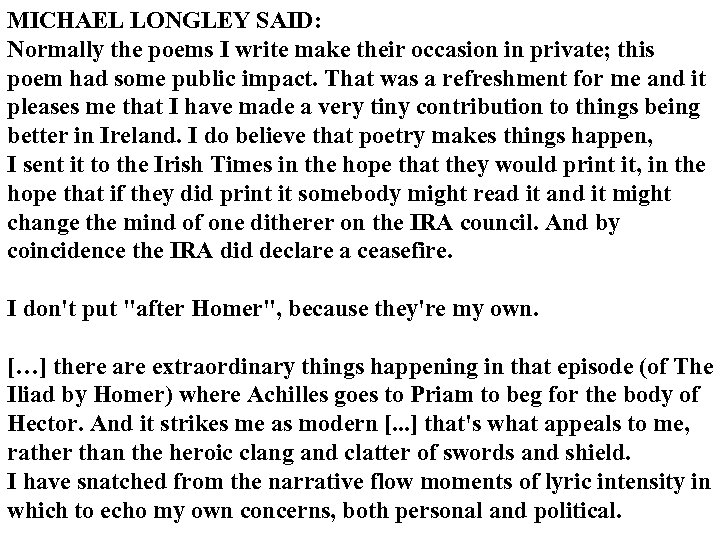

Michael Longley: Ceasefire In his poem titled Ceasefire Michael Longley (1939) draws on Homer's The Iliad. Longley makes an inter textual allusion to King Priam's request to Achilles for the release of the dead body of his son Hector killed in Battle during the Trojan Wars. (The Iliad, Book XXIV). Longley's sonnet was published in 1994, the year which saw important Republican and Loyalist para military ceasefires in the Ulster Troubles in Norhern Ireland.

Michael Longley: Ceasefire has often been read in the context of political events in Ireland known as 'The Peace Process'. Longley has translated this part of Homer’s epic poem into the 14 line English sonnet form.

Michael Longley (1939)

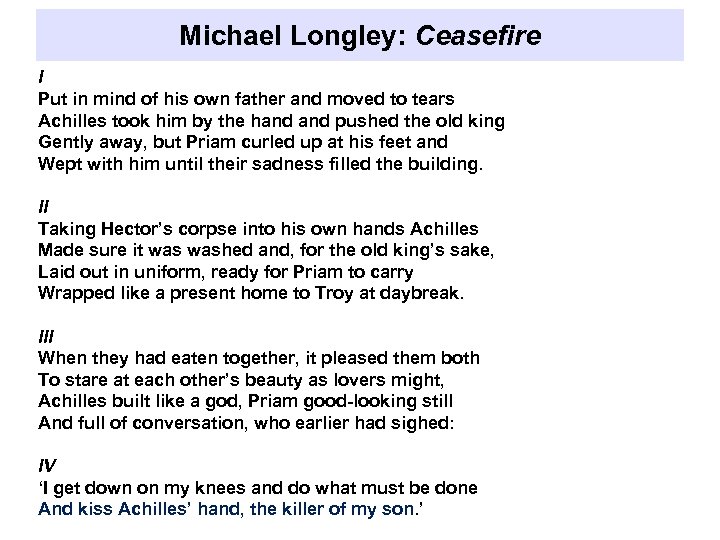

Michael Longley: Ceasefire I Put in mind of his own father and moved to tears Achilles took him by the hand pushed the old king Gently away, but Priam curled up at his feet and Wept with him until their sadness filled the building. II Taking Hector’s corpse into his own hands Achilles Made sure it washed and, for the old king’s sake, Laid out in uniform, ready for Priam to carry Wrapped like a present home to Troy at daybreak. III When they had eaten together, it pleased them both To stare at each other’s beauty as lovers might, Achilles built like a god, Priam good-looking still And full of conversation, who earlier had sighed: IV ‘I get down on my knees and do what must be done And kiss Achilles’ hand, the killer of my son. ’

MICHAEL LONGLEY SAID: Normally the poems I write make their occasion in private; this poem had some public impact. That was a refreshment for me and it pleases me that I have made a very tiny contribution to things being better in Ireland. I do believe that poetry makes things happen, I sent it to the Irish Times in the hope that they would print it, in the hope that if they did print it somebody might read it and it might change the mind of one ditherer on the IRA council. And by coincidence the IRA did declare a ceasefire. I don't put "after Homer", because they're my own. […] there are extraordinary things happening in that episode (of The Iliad by Homer) where Achilles goes to Priam to beg for the body of Hector. And it strikes me as modern [. . . ] that's what appeals to me, rather than the heroic clang and clatter of swords and shield. I have snatched from the narrative flow moments of lyric intensity in which to echo my own concerns, both personal and political.

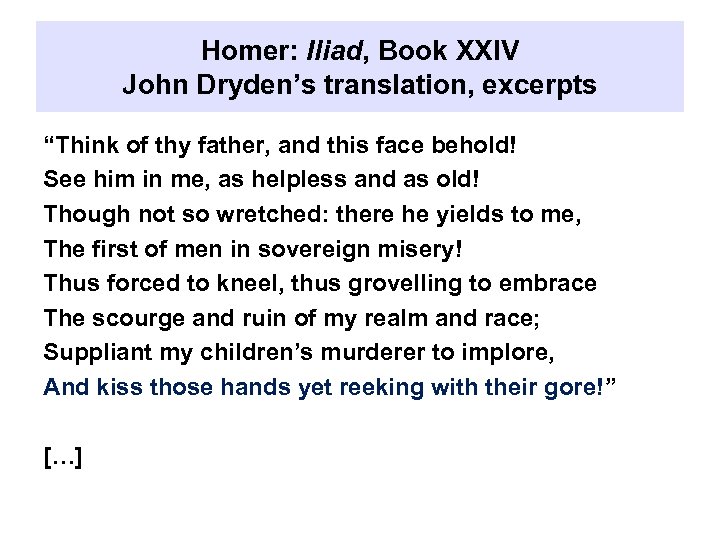

Homer: Iliad, Book XXIV John Dryden’s translation, excerpts “Think of thy father, and this face behold! See him in me, as helpless and as old! Though not so wretched: there he yields to me, The first of men in sovereign misery! Thus forced to kneel, thus grovelling to embrace The scourge and ruin of my realm and race; Suppliant my children’s murderer to implore, And kiss those hands yet reeking with their gore!” […]

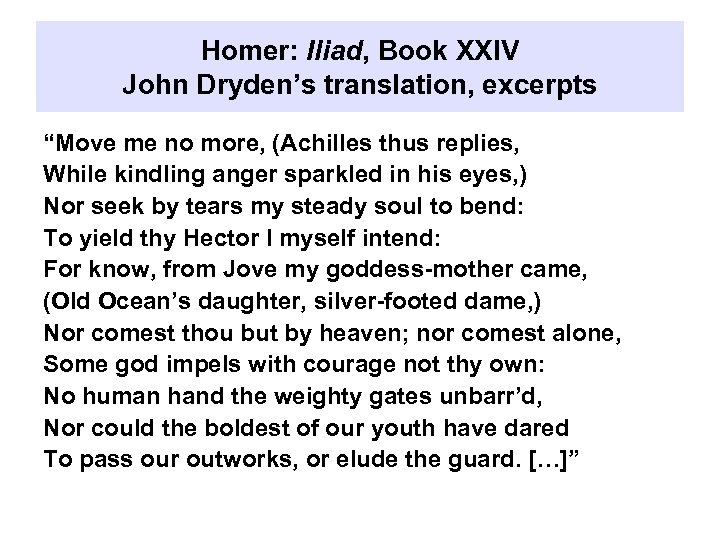

Homer: Iliad, Book XXIV John Dryden’s translation, excerpts “Move me no more, (Achilles thus replies, While kindling anger sparkled in his eyes, ) Nor seek by tears my steady soul to bend: To yield thy Hector I myself intend: For know, from Jove my goddess-mother came, (Old Ocean’s daughter, silver-footed dame, ) Nor comest thou but by heaven; nor comest alone, Some god impels with courage not thy own: No human hand the weighty gates unbarr’d, Nor could the boldest of our youth have dared To pass our outworks, or elude the guard. […]”

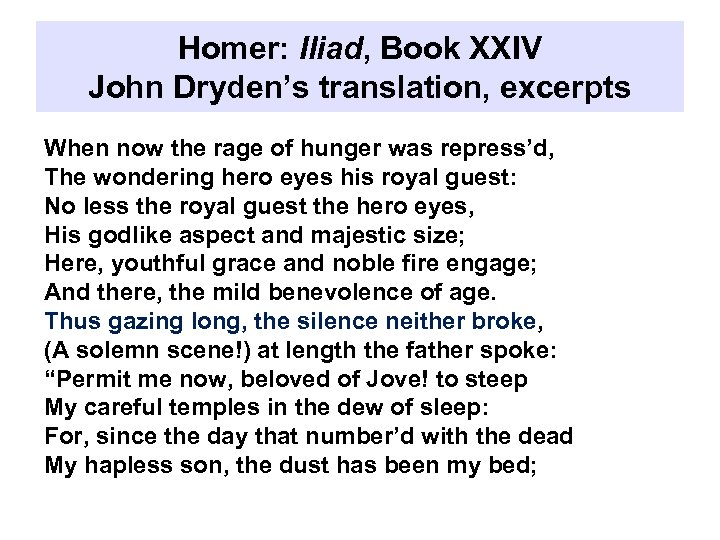

Homer: Iliad, Book XXIV John Dryden’s translation, excerpts When now the rage of hunger was repress’d, The wondering hero eyes his royal guest: No less the royal guest the hero eyes, His godlike aspect and majestic size; Here, youthful grace and noble fire engage; And there, the mild benevolence of age. Thus gazing long, the silence neither broke, (A solemn scene!) at length the father spoke: “Permit me now, beloved of Jove! to steep My careful temples in the dew of sleep: For, since the day that number’d with the dead My hapless son, the dust has been my bed;

Homer: Iliad, Book XXIV John Dryden’s translation, excerpts Then call the handmaids, with assistant toil To wash the body and anoint with oil, Apart from Priam: lest the unhappy sire, Provoked to passion, once more rouse to ire The stern Pelides; and nor sacred age, Nor Jove’s command, should check the rising rage. This done, the garments o’er the corse they spread; Achilles lifts it to the funeral bed: Then, while the body on the car they laid, He groans, and calls on loved Patroclus’ shade […]

Translation Studies Seamus Heaney (1939– 2013) • Sweeney Astray. A version from the Irish (1983) 12 th century Irish myth from the historical cycle • Beowulf (1999) • 8 th century Old English epic poem • Robert Henryson: The Testament of Cresseid (2004) • 15 th century Scottish epic poem • Laments, a cycle of Polish Renaissance elegies by Jan Kochanowski, translated with Stanisław Barańczak (1995)

Adaptation theory Connection between literary texts and work in other media Also, references to other media in literary works Affords new insights into literary texts and cultures that produce them Provide explicit or implicit commentarz on the author!s own art

Adaptation theory Research Discipline-specific skills required for productive engagement with another discipline, work in music or the visual arts, cinema Adaptations imply the possibility of some form of “translation” between literary and other forms , yet at the same, they draw attention to what is unique about each particular medium

Adaptation theory What a film director, opera composer or painter have made of a literary text often prompt judgements about the adaptations’s authenticity As a version of the source text or as work in its own right

Translation Studies See: http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Translation_studies Bhabha, Homi: The Location of Culture. London & New York: Routledge, 1994 Bassnett, Susan: Translation Studies. London & New York: Routledge, (1980) 2002 Steiner, George: After Babel. Oxford University Press, 1975 Venuti, Lawrence: The Translator's Invisibility: A History of Translation. London & New York: Routledge, 1995

0e8e6da81118523e23136168a8bddefc.ppt