07eff39a274079dd7756880fdc92e803.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 26

Lecture 11 These lecture covers introductory aspects related to: - Laser micromachining, FIB, Ebeam. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Lecture 11 These lecture covers introductory aspects related to: - Laser micromachining, FIB, Ebeam. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

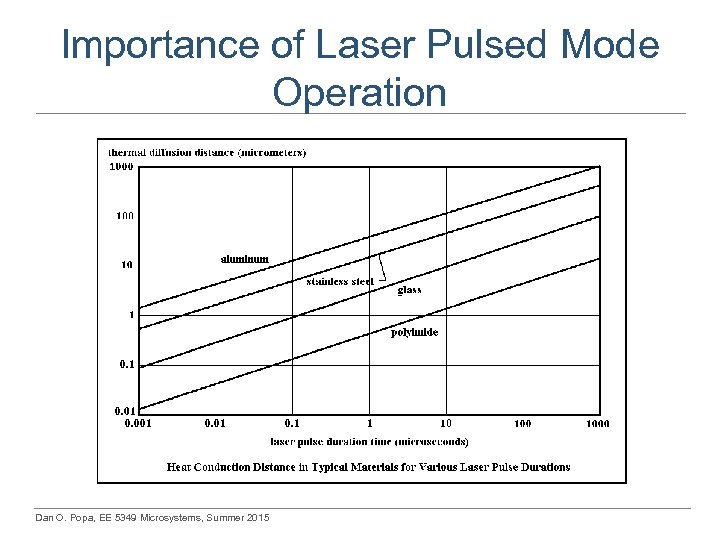

Importance of Laser Pulsed Mode Operation Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Importance of Laser Pulsed Mode Operation Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

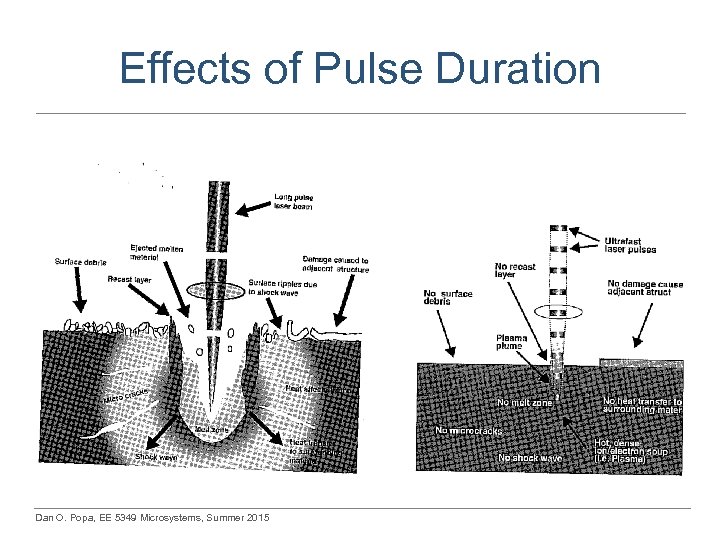

Effects of Pulse Duration Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Effects of Pulse Duration Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Properties and uses of lasers in micro-manufacturing • • Uses: heat treatment, welding, ablation (removal by vaporization), deposition, etching, lithography, stereolithography (polymer curing). Micromachining with short-pulse lasers introduced in 1982 at IBM research. Pulse lengths vary from CW (long or continuous), short (>10 ps), ultrashort (>1 fs). Laser wavelengths – from UV to IR. Shorter wavelengths can break molecular bonds in material easier. Role of optics is to focus the beam for two reasons: 1) minimizing the feature size, and 2) concentrating the laser energy. Smallest spot from a laser is limited by diffraction of the lens system, and is roughly λ/2. Dmin=4 M 2λf/πD, M-beam mode parameter (M=1 – perfect transverse mode of operation TEM 00), f-focal length of lens, D – diameter of beam at focusing lens. Depth of focus from a laser, is defined as the distance along optical path from the focus point, to the point where the beam is √ 2 larger. Do. F=8 M 2λf 2/πD 2. If Do. F is too small, one can only machine very flat surfaces unless auto-ranging is used. Laser beam intensity = 2 P/πDo 2, where P=Peak power (W) = Peak Energy/ pulse duration (s), and Do is the Gaussian beam radius, e. g. the distance from center where the power has decreased to 1/e 2 of the peak intensity. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Properties and uses of lasers in micro-manufacturing • • Uses: heat treatment, welding, ablation (removal by vaporization), deposition, etching, lithography, stereolithography (polymer curing). Micromachining with short-pulse lasers introduced in 1982 at IBM research. Pulse lengths vary from CW (long or continuous), short (>10 ps), ultrashort (>1 fs). Laser wavelengths – from UV to IR. Shorter wavelengths can break molecular bonds in material easier. Role of optics is to focus the beam for two reasons: 1) minimizing the feature size, and 2) concentrating the laser energy. Smallest spot from a laser is limited by diffraction of the lens system, and is roughly λ/2. Dmin=4 M 2λf/πD, M-beam mode parameter (M=1 – perfect transverse mode of operation TEM 00), f-focal length of lens, D – diameter of beam at focusing lens. Depth of focus from a laser, is defined as the distance along optical path from the focus point, to the point where the beam is √ 2 larger. Do. F=8 M 2λf 2/πD 2. If Do. F is too small, one can only machine very flat surfaces unless auto-ranging is used. Laser beam intensity = 2 P/πDo 2, where P=Peak power (W) = Peak Energy/ pulse duration (s), and Do is the Gaussian beam radius, e. g. the distance from center where the power has decreased to 1/e 2 of the peak intensity. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

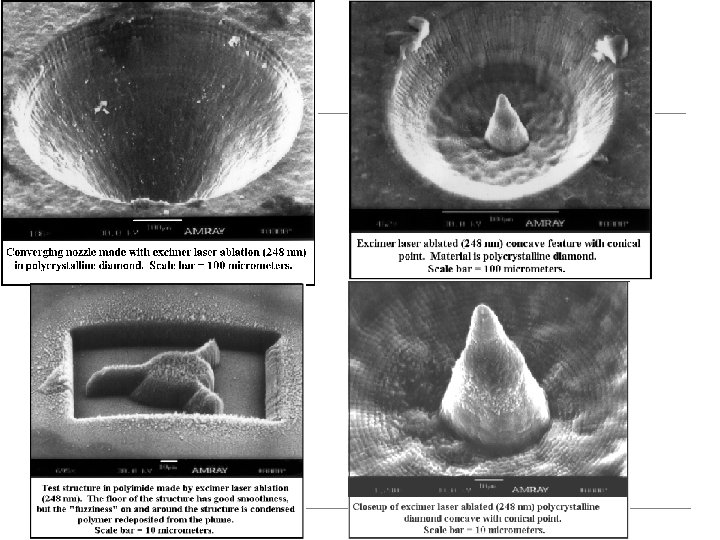

Laser Ablation: General • Ablation is removal of material because of the incident light. In most metals and glasses the removal is by vaporization of the material due to heat. In polymers the removal can be by photochemical changes which include a chemical dissolution of the polymer, akin to photolithography. • If the removal is by vaporization, special attention must be given to the plume. The plume will be a plasma-like substance consisting of molecular fragments, neutral particles, free electrons and ions, and chemical reaction products. The plume will be responsible for optical absorption and scattering of the incident beam and can condense on the surrounding work material and/or the beam delivery optics. Normally, the ablation site is cleared by a pressurized inert gas, such as nitrogen or argon. • If the material to be ablated has a poor absorption, such as diamond, but a thermally converted form of the material has relatively good absorption, such as graphite, then it is normal to cover the diamond surface with a thin coating of graphite. The laser will ablate the graphite and in doing so the surface of the underlying diamond will be converted to graphite allowing efficient absorption. Sequentially, the graphite is ablated and a new layer of diamond is converted. • Common lasers used for micromachining are pulsed excimer lasers which have a relatively low duty cycle, or less commonly they may be a continuous laser which is shuttered. That is, the pulse width (time) is very short compared to the time between pulses. Therefore, even though excimer lasers have a low average power compared to other larger lasers, the peak power of the excimers can be quite large. • Intensity (Watts/cm 2) = Peak power (W) / focal spot area (cm 2) • Fluence (Joules/cm 2) = Laser pulse energy (J) / focal spot area (cm 2) • Peak power (W) = Laser pulse energy (J) / pulse duration (sec) Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Laser Ablation: General • Ablation is removal of material because of the incident light. In most metals and glasses the removal is by vaporization of the material due to heat. In polymers the removal can be by photochemical changes which include a chemical dissolution of the polymer, akin to photolithography. • If the removal is by vaporization, special attention must be given to the plume. The plume will be a plasma-like substance consisting of molecular fragments, neutral particles, free electrons and ions, and chemical reaction products. The plume will be responsible for optical absorption and scattering of the incident beam and can condense on the surrounding work material and/or the beam delivery optics. Normally, the ablation site is cleared by a pressurized inert gas, such as nitrogen or argon. • If the material to be ablated has a poor absorption, such as diamond, but a thermally converted form of the material has relatively good absorption, such as graphite, then it is normal to cover the diamond surface with a thin coating of graphite. The laser will ablate the graphite and in doing so the surface of the underlying diamond will be converted to graphite allowing efficient absorption. Sequentially, the graphite is ablated and a new layer of diamond is converted. • Common lasers used for micromachining are pulsed excimer lasers which have a relatively low duty cycle, or less commonly they may be a continuous laser which is shuttered. That is, the pulse width (time) is very short compared to the time between pulses. Therefore, even though excimer lasers have a low average power compared to other larger lasers, the peak power of the excimers can be quite large. • Intensity (Watts/cm 2) = Peak power (W) / focal spot area (cm 2) • Fluence (Joules/cm 2) = Laser pulse energy (J) / focal spot area (cm 2) • Peak power (W) = Laser pulse energy (J) / pulse duration (sec) Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

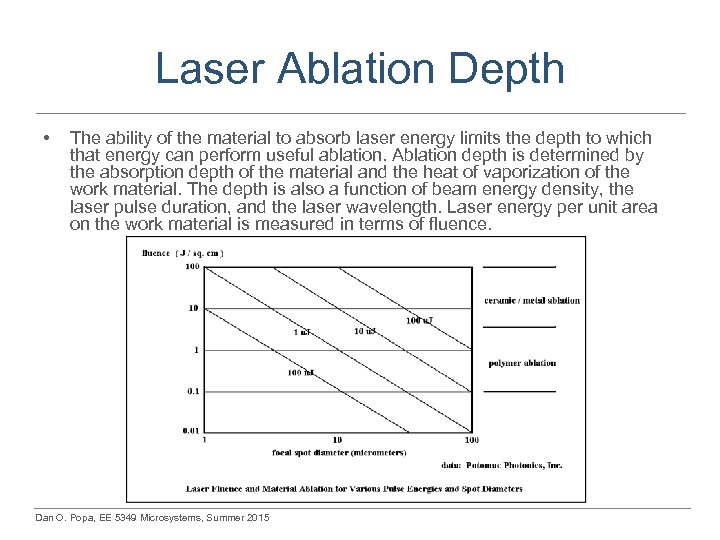

Laser Ablation Depth • The ability of the material to absorb laser energy limits the depth to which that energy can perform useful ablation. Ablation depth is determined by the absorption depth of the material and the heat of vaporization of the work material. The depth is also a function of beam energy density, the laser pulse duration, and the laser wavelength. Laser energy per unit area on the work material is measured in terms of fluence. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Laser Ablation Depth • The ability of the material to absorb laser energy limits the depth to which that energy can perform useful ablation. Ablation depth is determined by the absorption depth of the material and the heat of vaporization of the work material. The depth is also a function of beam energy density, the laser pulse duration, and the laser wavelength. Laser energy per unit area on the work material is measured in terms of fluence. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Laser Ablation Parameters • Small excimers as pulsed gas lasers operating in the deep ultra-violet spectrum (193 nm, 248 nm) with an output pulse energy between 5 m. J to 10 m. J and with repetition rates up to several hundred Hz. Typical beam sizes are in the order of 10 mm 2. A conventional 248 nm excimer laser in a production environment has a pulse energy of 250 m. J with a beam size of approximately 25 mm x 10 mm. • There are several key parameters to consider for laser ablation with excimer lasers: • The first parameter is selection of a wavelength with a minimum absorption depth. This will help ensure a high energy deposition in a small volume for rapid and complete ablation. • The second parameter is a short pulse duration to maximize peak power and to minimize thermal conduction to the surrounding work material. • The third parameter is the pulse repetition rate. If the rate is too low, all of the energy which was not used for ablation will leave the ablation zone allowing cooling. If the residual heat can be retained, thus limiting the time for conduction, by a rapid pulse repetition rate, the ablation will be more efficient. More of the incident energy will go toward ablation and less will be lost to the surrounding work material and the environment. • The fourth parameter is the beam quality. Beam quality is measured by the brightness (energy), the focusability, and the homogeneity. The beam energy is of no use if it can not be properly and efficiently delivered to the ablation region. Further, if the beam is not of a controlled size, the ablation region may be larger than desired with excessive slope in the sidewalls. • Fifth parameter is the fluence. Below a fluence threshold, no ablation occurs. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Laser Ablation Parameters • Small excimers as pulsed gas lasers operating in the deep ultra-violet spectrum (193 nm, 248 nm) with an output pulse energy between 5 m. J to 10 m. J and with repetition rates up to several hundred Hz. Typical beam sizes are in the order of 10 mm 2. A conventional 248 nm excimer laser in a production environment has a pulse energy of 250 m. J with a beam size of approximately 25 mm x 10 mm. • There are several key parameters to consider for laser ablation with excimer lasers: • The first parameter is selection of a wavelength with a minimum absorption depth. This will help ensure a high energy deposition in a small volume for rapid and complete ablation. • The second parameter is a short pulse duration to maximize peak power and to minimize thermal conduction to the surrounding work material. • The third parameter is the pulse repetition rate. If the rate is too low, all of the energy which was not used for ablation will leave the ablation zone allowing cooling. If the residual heat can be retained, thus limiting the time for conduction, by a rapid pulse repetition rate, the ablation will be more efficient. More of the incident energy will go toward ablation and less will be lost to the surrounding work material and the environment. • The fourth parameter is the beam quality. Beam quality is measured by the brightness (energy), the focusability, and the homogeneity. The beam energy is of no use if it can not be properly and efficiently delivered to the ablation region. Further, if the beam is not of a controlled size, the ablation region may be larger than desired with excessive slope in the sidewalls. • Fifth parameter is the fluence. Below a fluence threshold, no ablation occurs. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Laser Ablation: Heat Affected Zone • In laser ablation, a heat affected zone (HAZ) is left behind where molten material re-solidified in situ or where material was sufficiently heated and cooled rapidly enough to result in embrittlement. This change in material properties can alter subsequent laser ablation and material performance. The advantage of ablating with a short duration lasers is that the pulse width is short enough to greatly reduce the transfer of heat out of the ablation zone. This tends to localize the heat more and reduces the extent of the heat affected zone. • The size of the heat affected zone is a function of the laser pulse duration and the material parameters such as thermal conductivity and specific heat. The heat affected zone will depend on the distance the heat is conducted within the material and varies with material and laser wavelength. • The better the material conduction (thermal diffusivity) the greater is the extent of the heat affected zone. The effect of the HAZ on the material (embrittlement, for example) is more a function of the material thermomechanical properties. • During the ablation process, the expulsion of material in the plasma jet creates a compression on the molten pool of material under the laser spot. This will cause a portion of the liquified material to be forced out of the ablation zone and it will deposit onto the surrounding region. The amount of recast material can be minimized by a small absorption depth which will reduce the melted volume and a high laser power which will convert more of the melted material into vapor faster. • Debris is also a related problem of the ablation process. Particulate will redeposit onto the surface as solid fallout of higher boiling point second phases from the plume and as condensation of the primary material. The debris is commonly particulates of the substrate material if the ablation is sufficiently deep, oxides and nitrides of the work material or other contaminants, and products created by interactions within the plume. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Laser Ablation: Heat Affected Zone • In laser ablation, a heat affected zone (HAZ) is left behind where molten material re-solidified in situ or where material was sufficiently heated and cooled rapidly enough to result in embrittlement. This change in material properties can alter subsequent laser ablation and material performance. The advantage of ablating with a short duration lasers is that the pulse width is short enough to greatly reduce the transfer of heat out of the ablation zone. This tends to localize the heat more and reduces the extent of the heat affected zone. • The size of the heat affected zone is a function of the laser pulse duration and the material parameters such as thermal conductivity and specific heat. The heat affected zone will depend on the distance the heat is conducted within the material and varies with material and laser wavelength. • The better the material conduction (thermal diffusivity) the greater is the extent of the heat affected zone. The effect of the HAZ on the material (embrittlement, for example) is more a function of the material thermomechanical properties. • During the ablation process, the expulsion of material in the plasma jet creates a compression on the molten pool of material under the laser spot. This will cause a portion of the liquified material to be forced out of the ablation zone and it will deposit onto the surrounding region. The amount of recast material can be minimized by a small absorption depth which will reduce the melted volume and a high laser power which will convert more of the melted material into vapor faster. • Debris is also a related problem of the ablation process. Particulate will redeposit onto the surface as solid fallout of higher boiling point second phases from the plume and as condensation of the primary material. The debris is commonly particulates of the substrate material if the ablation is sufficiently deep, oxides and nitrides of the work material or other contaminants, and products created by interactions within the plume. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

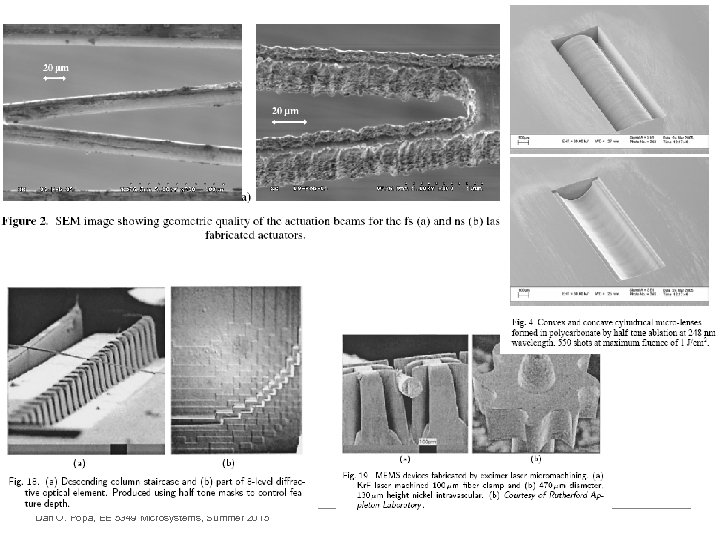

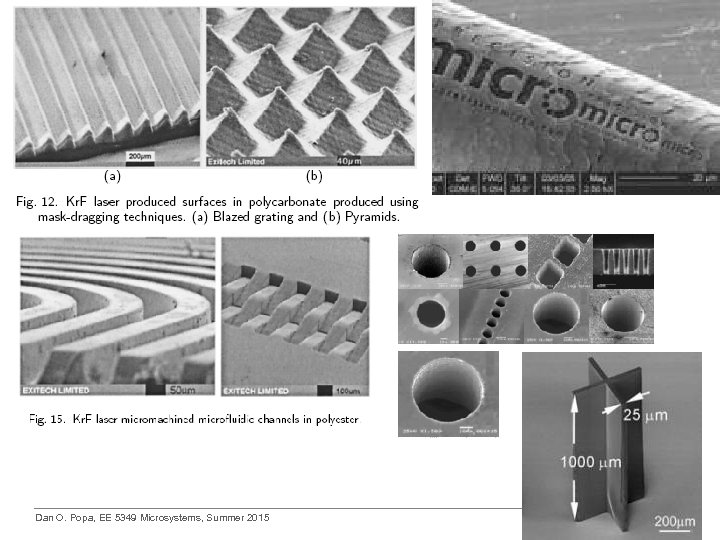

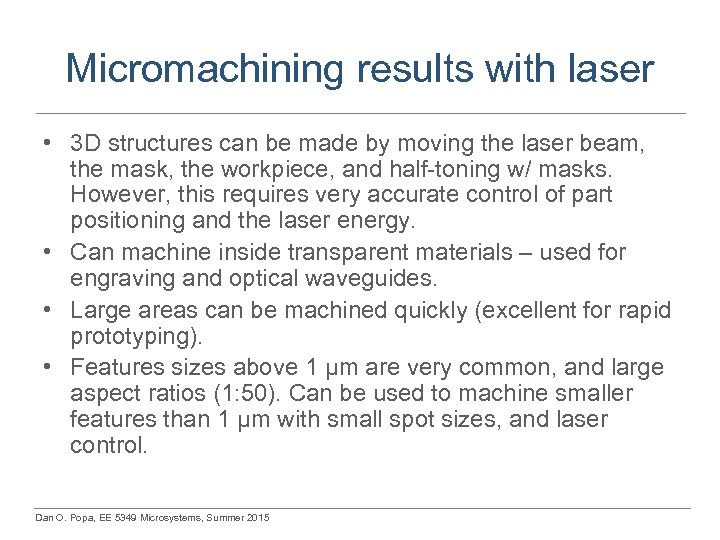

Micromachining results with laser • 3 D structures can be made by moving the laser beam, the mask, the workpiece, and half-toning w/ masks. However, this requires very accurate control of part positioning and the laser energy. • Can machine inside transparent materials – used for engraving and optical waveguides. • Large areas can be machined quickly (excellent for rapid prototyping). • Features sizes above 1 µm are very common, and large aspect ratios (1: 50). Can be used to machine smaller features than 1 µm with small spot sizes, and laser control. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Micromachining results with laser • 3 D structures can be made by moving the laser beam, the mask, the workpiece, and half-toning w/ masks. However, this requires very accurate control of part positioning and the laser energy. • Can machine inside transparent materials – used for engraving and optical waveguides. • Large areas can be machined quickly (excellent for rapid prototyping). • Features sizes above 1 µm are very common, and large aspect ratios (1: 50). Can be used to machine smaller features than 1 µm with small spot sizes, and laser control. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

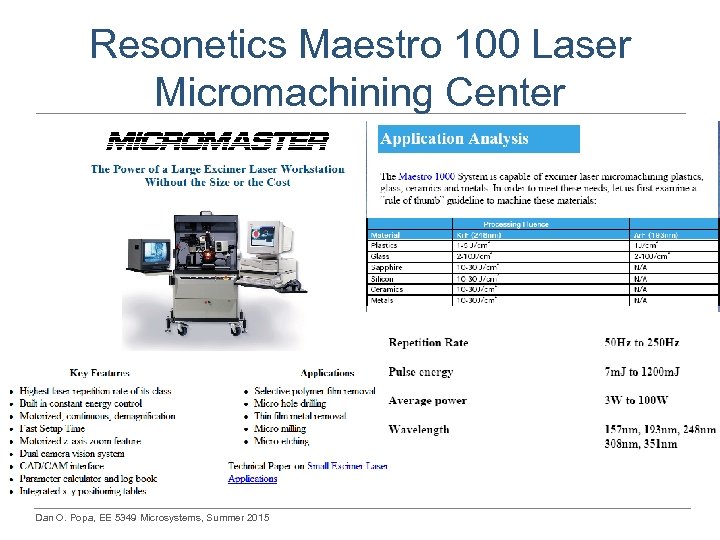

Resonetics Maestro 100 Laser Micromachining Center Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Resonetics Maestro 100 Laser Micromachining Center Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

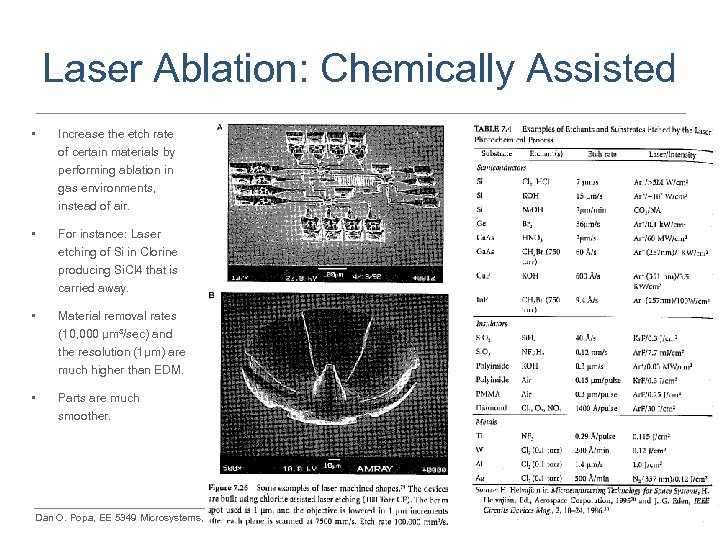

Laser Ablation: Chemically Assisted • Increase the etch rate of certain materials by performing ablation in gas environments, instead of air. • For instance: Laser etching of Si in Clorine producing Si. Cl 4 that is carried away. • Material removal rates (10, 000 µm³/sec) and the resolution (1µm) are much higher than EDM. • Parts are much smoother. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Laser Ablation: Chemically Assisted • Increase the etch rate of certain materials by performing ablation in gas environments, instead of air. • For instance: Laser etching of Si in Clorine producing Si. Cl 4 that is carried away. • Material removal rates (10, 000 µm³/sec) and the resolution (1µm) are much higher than EDM. • Parts are much smoother. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

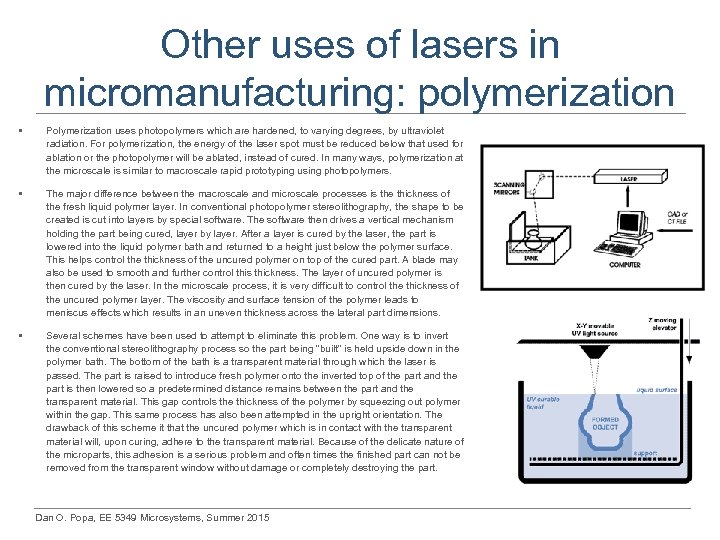

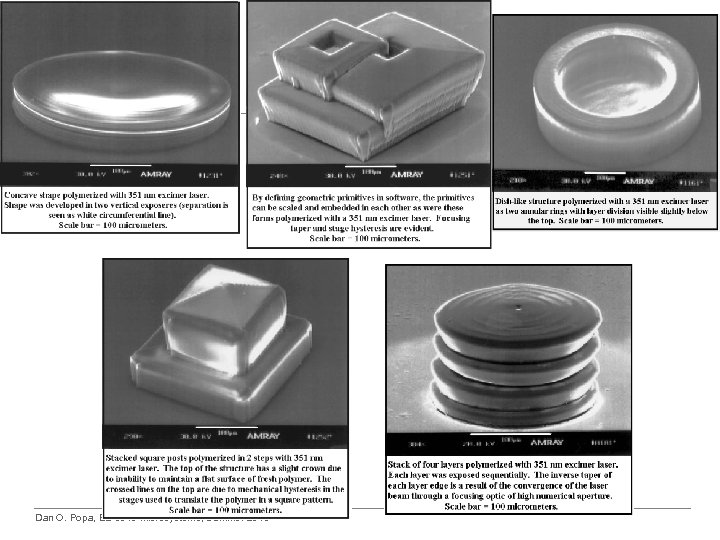

Other uses of lasers in micromanufacturing: polymerization • Polymerization uses photopolymers which are hardened, to varying degrees, by ultraviolet radiation. For polymerization, the energy of the laser spot must be reduced below that used for ablation or the photopolymer will be ablated, instead of cured. In many ways, polymerization at the microscale is similar to macroscale rapid prototyping using photopolymers. • The major difference between the macroscale and microscale processes is the thickness of the fresh liquid polymer layer. In conventional photopolymer stereolithography, the shape to be created is cut into layers by special software. The software then drives a vertical mechanism holding the part being cured, layer by layer. After a layer is cured by the laser, the part is lowered into the liquid polymer bath and returned to a height just below the polymer surface. This helps control the thickness of the uncured polymer on top of the cured part. A blade may also be used to smooth and further control this thickness. The layer of uncured polymer is then cured by the laser. In the microscale process, it is very difficult to control the thickness of the uncured polymer layer. The viscosity and surface tension of the polymer leads to meniscus effects which results in an uneven thickness across the lateral part dimensions. • Several schemes have been used to attempt to eliminate this problem. One way is to invert the conventional stereolithography process so the part being "built" is held upside down in the polymer bath. The bottom of the bath is a transparent material through which the laser is passed. The part is raised to introduce fresh polymer onto the inverted top of the part and the part is then lowered so a predetermined distance remains between the part and the transparent material. This gap controls the thickness of the polymer by squeezing out polymer within the gap. This same process has also been attempted in the upright orientation. The drawback of this scheme it that the uncured polymer which is in contact with the transparent material will, upon curing, adhere to the transparent material. Because of the delicate nature of the microparts, this adhesion is a serious problem and often times the finished part can not be removed from the transparent window without damage or completely destroying the part. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Other uses of lasers in micromanufacturing: polymerization • Polymerization uses photopolymers which are hardened, to varying degrees, by ultraviolet radiation. For polymerization, the energy of the laser spot must be reduced below that used for ablation or the photopolymer will be ablated, instead of cured. In many ways, polymerization at the microscale is similar to macroscale rapid prototyping using photopolymers. • The major difference between the macroscale and microscale processes is the thickness of the fresh liquid polymer layer. In conventional photopolymer stereolithography, the shape to be created is cut into layers by special software. The software then drives a vertical mechanism holding the part being cured, layer by layer. After a layer is cured by the laser, the part is lowered into the liquid polymer bath and returned to a height just below the polymer surface. This helps control the thickness of the uncured polymer on top of the cured part. A blade may also be used to smooth and further control this thickness. The layer of uncured polymer is then cured by the laser. In the microscale process, it is very difficult to control the thickness of the uncured polymer layer. The viscosity and surface tension of the polymer leads to meniscus effects which results in an uneven thickness across the lateral part dimensions. • Several schemes have been used to attempt to eliminate this problem. One way is to invert the conventional stereolithography process so the part being "built" is held upside down in the polymer bath. The bottom of the bath is a transparent material through which the laser is passed. The part is raised to introduce fresh polymer onto the inverted top of the part and the part is then lowered so a predetermined distance remains between the part and the transparent material. This gap controls the thickness of the polymer by squeezing out polymer within the gap. This same process has also been attempted in the upright orientation. The drawback of this scheme it that the uncured polymer which is in contact with the transparent material will, upon curing, adhere to the transparent material. Because of the delicate nature of the microparts, this adhesion is a serious problem and often times the finished part can not be removed from the transparent window without damage or completely destroying the part. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

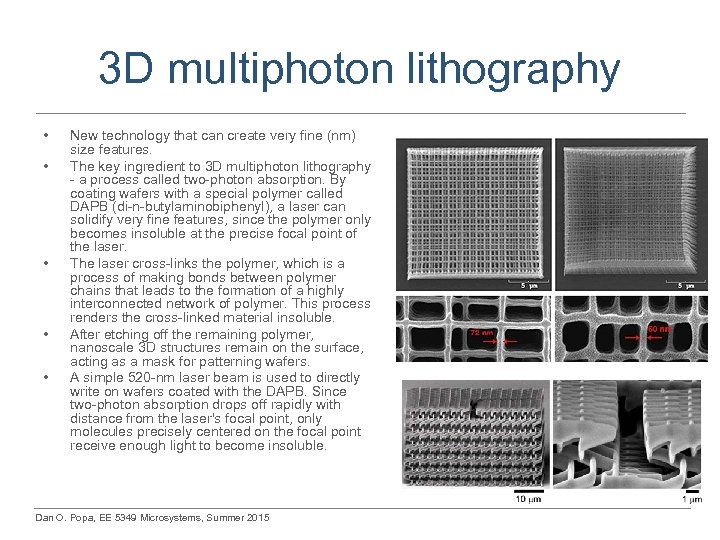

3 D multiphoton lithography • • • New technology that can create very fine (nm) size features. The key ingredient to 3 D multiphoton lithography - a process called two-photon absorption. By coating wafers with a special polymer called DAPB (di-n-butylaminobiphenyl), a laser can solidify very fine features, since the polymer only becomes insoluble at the precise focal point of the laser. The laser cross-links the polymer, which is a process of making bonds between polymer chains that leads to the formation of a highly interconnected network of polymer. This process renders the cross-linked material insoluble. After etching off the remaining polymer, nanoscale 3 D structures remain on the surface, acting as a mask for patterning wafers. A simple 520 -nm laser beam is used to directly write on wafers coated with the DAPB. Since two-photon absorption drops off rapidly with distance from the laser's focal point, only molecules precisely centered on the focal point receive enough light to become insoluble. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

3 D multiphoton lithography • • • New technology that can create very fine (nm) size features. The key ingredient to 3 D multiphoton lithography - a process called two-photon absorption. By coating wafers with a special polymer called DAPB (di-n-butylaminobiphenyl), a laser can solidify very fine features, since the polymer only becomes insoluble at the precise focal point of the laser. The laser cross-links the polymer, which is a process of making bonds between polymer chains that leads to the formation of a highly interconnected network of polymer. This process renders the cross-linked material insoluble. After etching off the remaining polymer, nanoscale 3 D structures remain on the surface, acting as a mask for patterning wafers. A simple 520 -nm laser beam is used to directly write on wafers coated with the DAPB. Since two-photon absorption drops off rapidly with distance from the laser's focal point, only molecules precisely centered on the focal point receive enough light to become insoluble. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

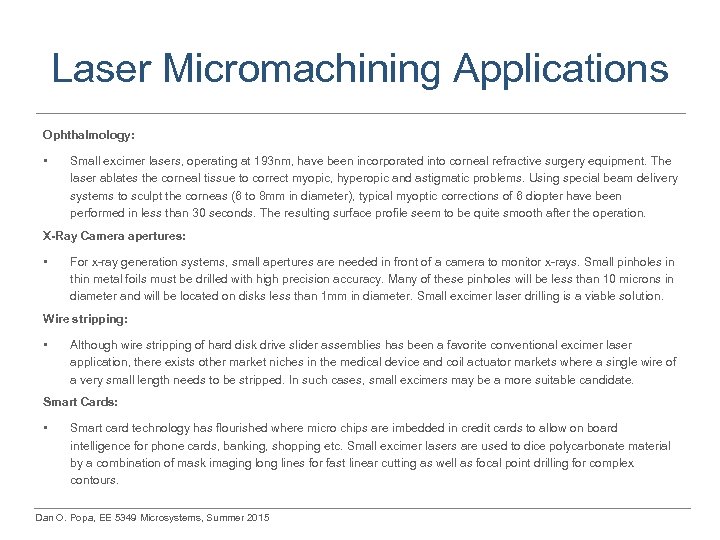

Laser Micromachining Applications Ophthalmology: • Small excimer lasers, operating at 193 nm, have been incorporated into corneal refractive surgery equipment. The laser ablates the corneal tissue to correct myopic, hyperopic and astigmatic problems. Using special beam delivery systems to sculpt the corneas (6 to 8 mm in diameter), typical myoptic corrections of 6 diopter have been performed in less than 30 seconds. The resulting surface profile seem to be quite smooth after the operation. X-Ray Camera apertures: • For x-ray generation systems, small apertures are needed in front of a camera to monitor x-rays. Small pinholes in thin metal foils must be drilled with high precision accuracy. Many of these pinholes will be less than 10 microns in diameter and will be located on disks less than 1 mm in diameter. Small excimer laser drilling is a viable solution. Wire stripping: • Although wire stripping of hard disk drive slider assemblies has been a favorite conventional excimer laser application, there exists other market niches in the medical device and coil actuator markets where a single wire of a very small length needs to be stripped. In such cases, small excimers may be a more suitable candidate. Smart Cards: • Smart card technology has flourished where micro chips are imbedded in credit cards to allow on board intelligence for phone cards, banking, shopping etc. Small excimer lasers are used to dice polycarbonate material by a combination of mask imaging long lines for fast linear cutting as well as focal point drilling for complex contours. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Laser Micromachining Applications Ophthalmology: • Small excimer lasers, operating at 193 nm, have been incorporated into corneal refractive surgery equipment. The laser ablates the corneal tissue to correct myopic, hyperopic and astigmatic problems. Using special beam delivery systems to sculpt the corneas (6 to 8 mm in diameter), typical myoptic corrections of 6 diopter have been performed in less than 30 seconds. The resulting surface profile seem to be quite smooth after the operation. X-Ray Camera apertures: • For x-ray generation systems, small apertures are needed in front of a camera to monitor x-rays. Small pinholes in thin metal foils must be drilled with high precision accuracy. Many of these pinholes will be less than 10 microns in diameter and will be located on disks less than 1 mm in diameter. Small excimer laser drilling is a viable solution. Wire stripping: • Although wire stripping of hard disk drive slider assemblies has been a favorite conventional excimer laser application, there exists other market niches in the medical device and coil actuator markets where a single wire of a very small length needs to be stripped. In such cases, small excimers may be a more suitable candidate. Smart Cards: • Smart card technology has flourished where micro chips are imbedded in credit cards to allow on board intelligence for phone cards, banking, shopping etc. Small excimer lasers are used to dice polycarbonate material by a combination of mask imaging long lines for fast linear cutting as well as focal point drilling for complex contours. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

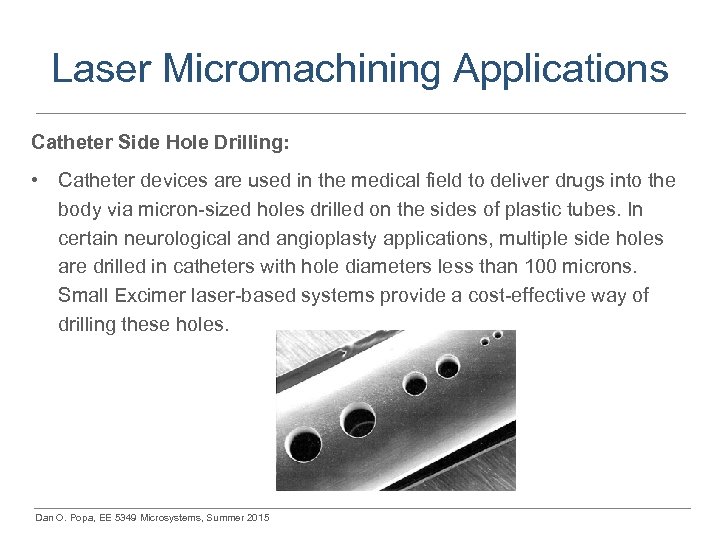

Laser Micromachining Applications Catheter Side Hole Drilling: • Catheter devices are used in the medical field to deliver drugs into the body via micron-sized holes drilled on the sides of plastic tubes. In certain neurological and angioplasty applications, multiple side holes are drilled in catheters with hole diameters less than 100 microns. Small Excimer laser-based systems provide a cost-effective way of drilling these holes. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Laser Micromachining Applications Catheter Side Hole Drilling: • Catheter devices are used in the medical field to deliver drugs into the body via micron-sized holes drilled on the sides of plastic tubes. In certain neurological and angioplasty applications, multiple side holes are drilled in catheters with hole diameters less than 100 microns. Small Excimer laser-based systems provide a cost-effective way of drilling these holes. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

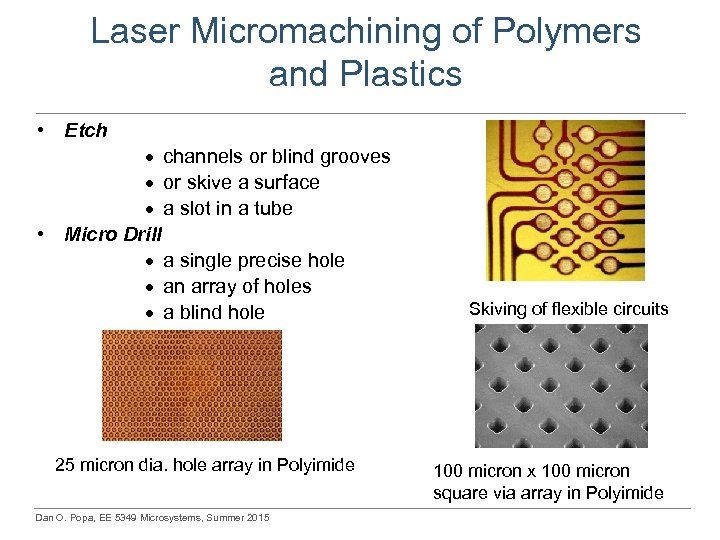

Laser Micromachining of Polymers and Plastics • Etch · channels or blind grooves · or skive a surface · a slot in a tube • Micro Drill · a single precise hole · an array of holes · a blind hole 25 micron dia. hole array in Polyimide Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015 Skiving of flexible circuits 100 micron x 100 micron square via array in Polyimide

Laser Micromachining of Polymers and Plastics • Etch · channels or blind grooves · or skive a surface · a slot in a tube • Micro Drill · a single precise hole · an array of holes · a blind hole 25 micron dia. hole array in Polyimide Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015 Skiving of flexible circuits 100 micron x 100 micron square via array in Polyimide

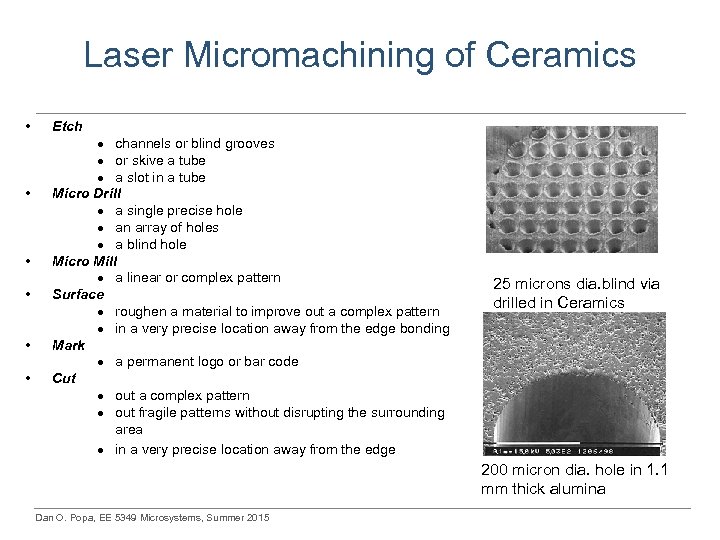

Laser Micromachining of Ceramics • • • Etch · channels or blind grooves · or skive a tube · a slot in a tube Micro Drill · a single precise hole · an array of holes · a blind hole Micro Mill · a linear or complex pattern Surface · roughen a material to improve out a complex pattern · in a very precise location away from the edge bonding Mark · a permanent logo or bar code Cut · out a complex pattern · out fragile patterns without disrupting the surrounding area · in a very precise location away from the edge 25 microns dia. blind via drilled in Ceramics 200 micron dia. hole in 1. 1 mm thick alumina Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Laser Micromachining of Ceramics • • • Etch · channels or blind grooves · or skive a tube · a slot in a tube Micro Drill · a single precise hole · an array of holes · a blind hole Micro Mill · a linear or complex pattern Surface · roughen a material to improve out a complex pattern · in a very precise location away from the edge bonding Mark · a permanent logo or bar code Cut · out a complex pattern · out fragile patterns without disrupting the surrounding area · in a very precise location away from the edge 25 microns dia. blind via drilled in Ceramics 200 micron dia. hole in 1. 1 mm thick alumina Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

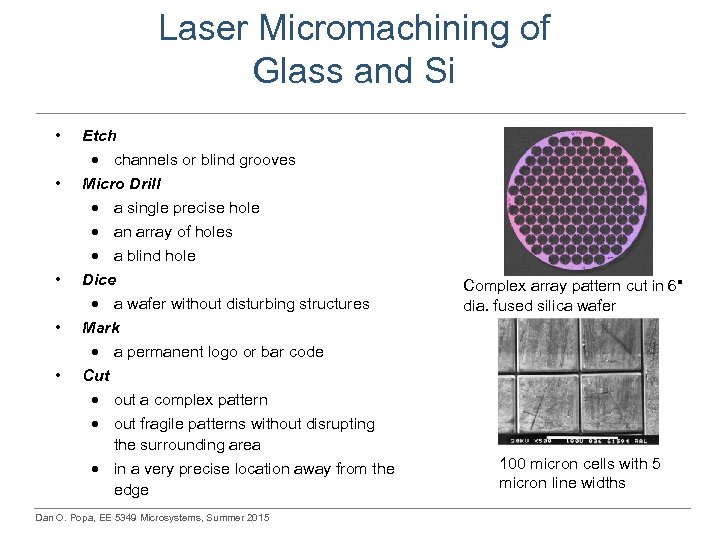

Laser Micromachining of Glass and Si • • • Etch · channels or blind grooves Micro Drill · a single precise hole · an array of holes · a blind hole Dice · a wafer without disturbing structures Mark · a permanent logo or bar code Cut · out a complex pattern · out fragile patterns without disrupting the surrounding area · in a very precise location away from the edge Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015 Complex array pattern cut in 6" dia. fused silica wafer 100 micron cells with 5 micron line widths

Laser Micromachining of Glass and Si • • • Etch · channels or blind grooves Micro Drill · a single precise hole · an array of holes · a blind hole Dice · a wafer without disturbing structures Mark · a permanent logo or bar code Cut · out a complex pattern · out fragile patterns without disrupting the surrounding area · in a very precise location away from the edge Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015 Complex array pattern cut in 6" dia. fused silica wafer 100 micron cells with 5 micron line widths

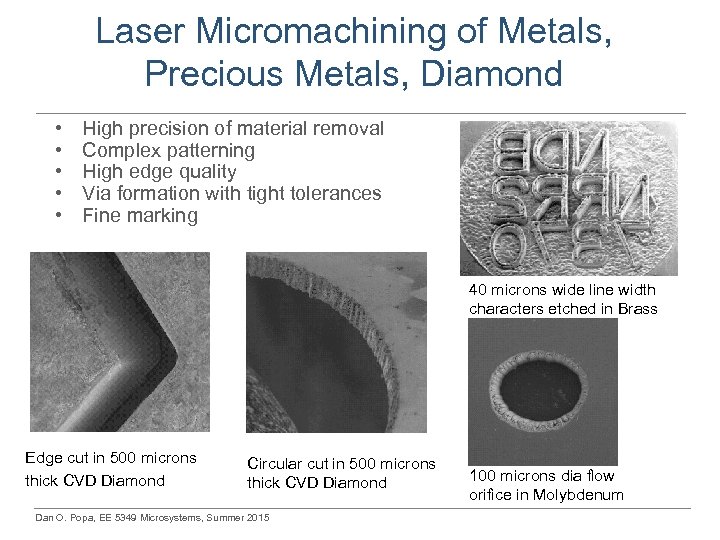

Laser Micromachining of Metals, Precious Metals, Diamond • • • High precision of material removal Complex patterning High edge quality Via formation with tight tolerances Fine marking 40 microns wide line width characters etched in Brass Edge cut in 500 microns thick CVD Diamond Circular cut in 500 microns thick CVD Diamond Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015 100 microns dia flow orifice in Molybdenum

Laser Micromachining of Metals, Precious Metals, Diamond • • • High precision of material removal Complex patterning High edge quality Via formation with tight tolerances Fine marking 40 microns wide line width characters etched in Brass Edge cut in 500 microns thick CVD Diamond Circular cut in 500 microns thick CVD Diamond Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015 100 microns dia flow orifice in Molybdenum

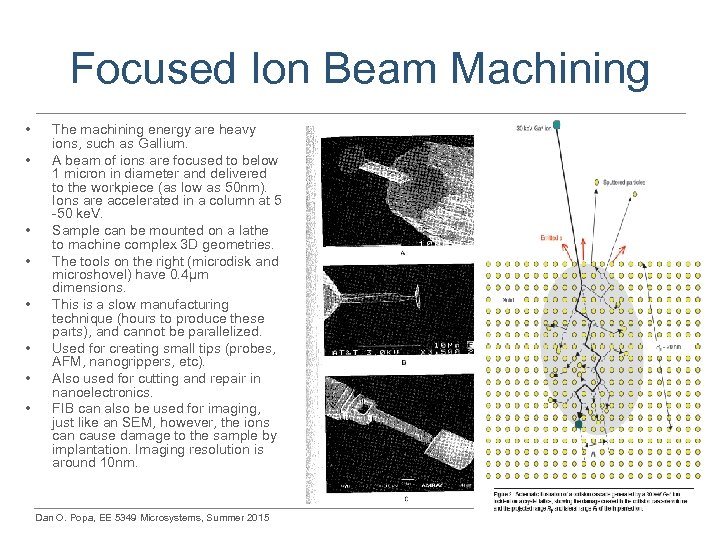

Focused Ion Beam Machining • • The machining energy are heavy ions, such as Gallium. A beam of ions are focused to below 1 micron in diameter and delivered to the workpiece (as low as 50 nm). Ions are accelerated in a column at 5 -50 ke. V. Sample can be mounted on a lathe to machine complex 3 D geometries. The tools on the right (microdisk and microshovel) have 0. 4µm dimensions. This is a slow manufacturing technique (hours to produce these parts), and cannot be parallelized. Used for creating small tips (probes, AFM, nanogrippers, etc). Also used for cutting and repair in nanoelectronics. FIB can also be used for imaging, just like an SEM, however, the ions can cause damage to the sample by implantation. Imaging resolution is around 10 nm. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Focused Ion Beam Machining • • The machining energy are heavy ions, such as Gallium. A beam of ions are focused to below 1 micron in diameter and delivered to the workpiece (as low as 50 nm). Ions are accelerated in a column at 5 -50 ke. V. Sample can be mounted on a lathe to machine complex 3 D geometries. The tools on the right (microdisk and microshovel) have 0. 4µm dimensions. This is a slow manufacturing technique (hours to produce these parts), and cannot be parallelized. Used for creating small tips (probes, AFM, nanogrippers, etc). Also used for cutting and repair in nanoelectronics. FIB can also be used for imaging, just like an SEM, however, the ions can cause damage to the sample by implantation. Imaging resolution is around 10 nm. Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

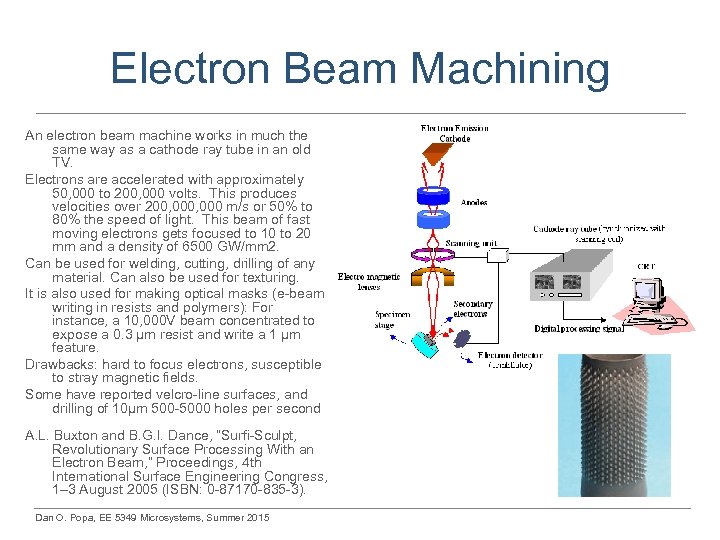

Electron Beam Machining An electron beam machine works in much the same way as a cathode ray tube in an old TV. Electrons are accelerated with approximately 50, 000 to 200, 000 volts. This produces velocities over 200, 000 m/s or 50% to 80% the speed of light. This beam of fast moving electrons gets focused to 10 to 20 mm and a density of 6500 GW/mm 2. Can be used for welding, cutting, drilling of any material. Can also be used for texturing. It is also used for making optical masks (e-beam writing in resists and polymers): For instance, a 10, 000 V beam concentrated to expose a 0. 3 µm resist and write a 1 µm feature. Drawbacks: hard to focus electrons, susceptible to stray magnetic fields. Some have reported velcro-line surfaces, and drilling of 10µm 500 -5000 holes per second A. L. Buxton and B. G. I. Dance, “Surfi-Sculpt, Revolutionary Surface Processing With an Electron Beam, ” Proceedings, 4 th International Surface Engineering Congress, 1– 3 August 2005 (ISBN: 0 -87170 -835 -3). Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Electron Beam Machining An electron beam machine works in much the same way as a cathode ray tube in an old TV. Electrons are accelerated with approximately 50, 000 to 200, 000 volts. This produces velocities over 200, 000 m/s or 50% to 80% the speed of light. This beam of fast moving electrons gets focused to 10 to 20 mm and a density of 6500 GW/mm 2. Can be used for welding, cutting, drilling of any material. Can also be used for texturing. It is also used for making optical masks (e-beam writing in resists and polymers): For instance, a 10, 000 V beam concentrated to expose a 0. 3 µm resist and write a 1 µm feature. Drawbacks: hard to focus electrons, susceptible to stray magnetic fields. Some have reported velcro-line surfaces, and drilling of 10µm 500 -5000 holes per second A. L. Buxton and B. G. I. Dance, “Surfi-Sculpt, Revolutionary Surface Processing With an Electron Beam, ” Proceedings, 4 th International Surface Engineering Congress, 1– 3 August 2005 (ISBN: 0 -87170 -835 -3). Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Readings for Week 6 • • Madou Text, Chapter 7 Laser Micromachining: http: //www. ise. rutgers. edu/research/working_paper/paper_07 -021. pdf http: //www. iop. org/EJ/article/1742 -6596/59/1/148/jpconf 7_59_148. pdf? request-id=ir 3 TCLTk 3 BGWm. Hf. O 2 wi 7 Kg http: //www. riken. go. jp/lab-www/library/publication/review/pdf/No_32/32_050. pdf http: //www 3. imperial. ac. uk/pls/portallive/docs/1/3035914. PDF http: //www. resonetics. com/PDF/MDDI_Micromachining. pdf http: //spie. org/x 8778. xml? pf=true&highlight=x 2402 http: //www. eetimes. com/news/semi/show. Article. jhtml? article. ID=198701422 • Focused Ion beam machining http: //www. fei. com/uploaded. Files/Documents/Content/MRS_Bulletin_2007_FIB_machining. pdf Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015

Readings for Week 6 • • Madou Text, Chapter 7 Laser Micromachining: http: //www. ise. rutgers. edu/research/working_paper/paper_07 -021. pdf http: //www. iop. org/EJ/article/1742 -6596/59/1/148/jpconf 7_59_148. pdf? request-id=ir 3 TCLTk 3 BGWm. Hf. O 2 wi 7 Kg http: //www. riken. go. jp/lab-www/library/publication/review/pdf/No_32/32_050. pdf http: //www 3. imperial. ac. uk/pls/portallive/docs/1/3035914. PDF http: //www. resonetics. com/PDF/MDDI_Micromachining. pdf http: //spie. org/x 8778. xml? pf=true&highlight=x 2402 http: //www. eetimes. com/news/semi/show. Article. jhtml? article. ID=198701422 • Focused Ion beam machining http: //www. fei. com/uploaded. Files/Documents/Content/MRS_Bulletin_2007_FIB_machining. pdf Dan O. Popa, EE 5349 Microsystems, Summer 2015