332821dcdaef8bed94f363e66bc9fd4b.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 26

Lecture 11: Birthday Paradoxes CS 588: Security and Privacy David Evans University of Virginia 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 http: //www. cs. virginia. edu/~evans Computer Science

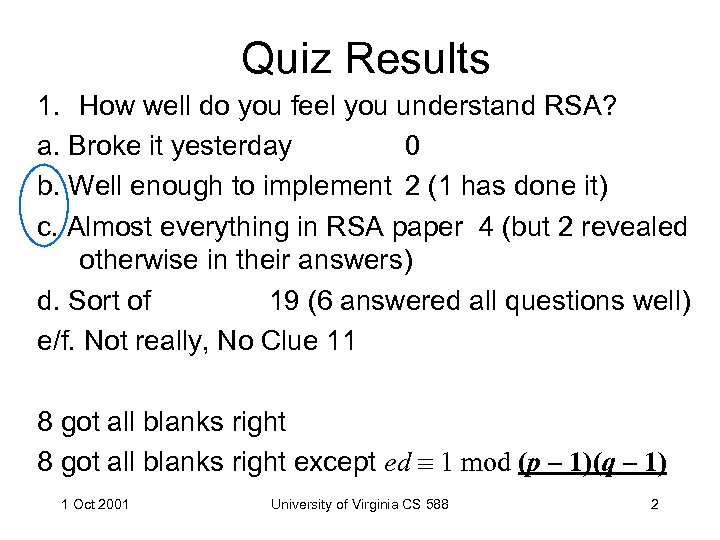

Quiz Results 1. How well do you feel you understand RSA? a. Broke it yesterday 0 b. Well enough to implement 2 (1 has done it) c. Almost everything in RSA paper 4 (but 2 revealed otherwise in their answers) d. Sort of 19 (6 answered all questions well) e/f. Not really, No Clue 11 8 got all blanks right except ed 1 mod (p – 1)(q – 1) 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 2

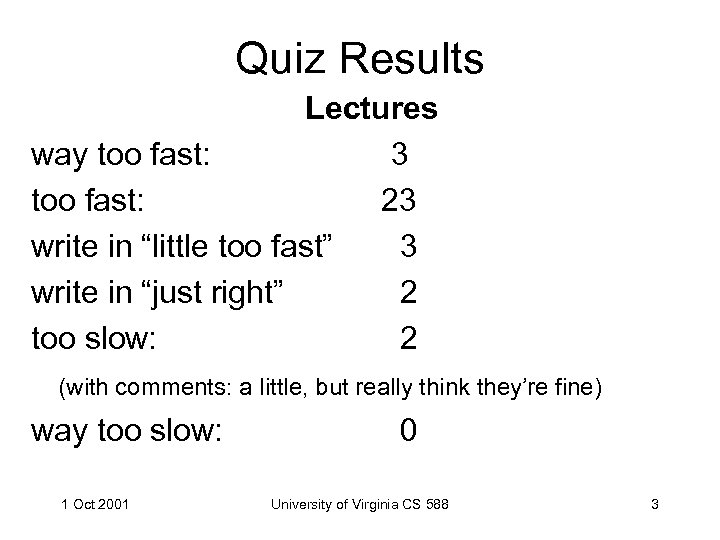

Quiz Results Lectures way too fast: 3 too fast: 23 write in “little too fast” 3 write in “just right” 2 too slow: 2 (with comments: a little, but really think they’re fine) way too slow: 1 Oct 2001 0 University of Virginia CS 588 3

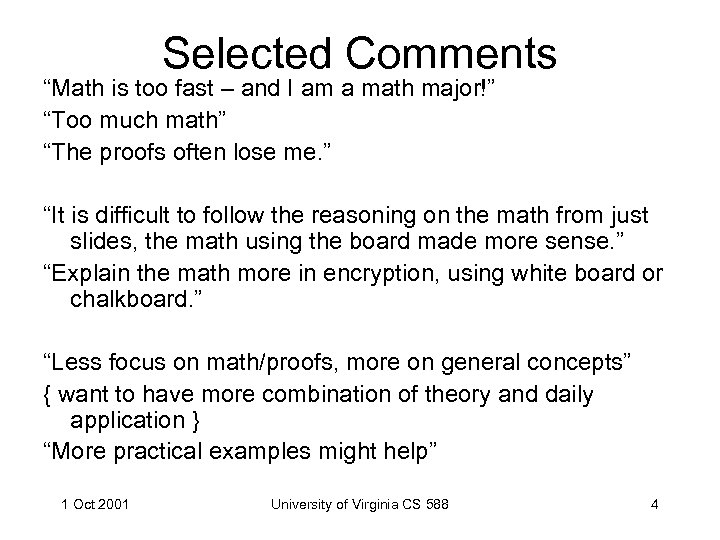

Selected Comments “Math is too fast – and I am a math major!” “Too much math” “The proofs often lose me. ” “It is difficult to follow the reasoning on the math from just slides, the math using the board made more sense. ” “Explain the math more in encryption, using white board or chalkboard. ” “Less focus on math/proofs, more on general concepts” { want to have more combination of theory and daily application } “More practical examples might help” 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 4

More Comments “Doing the homework always helps me understand much better. ” “I usually can’t keep up in lectures, but can understand after reviewing slides out of class. ” “All quizes and tests should be anonymous. ” “Wish people felt more comfortable speaking out answers even when wrong. ” “You tend to progress as soon as you have verification that 1 person understands. Wait ‘till the majority of the class understands. ” 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 5

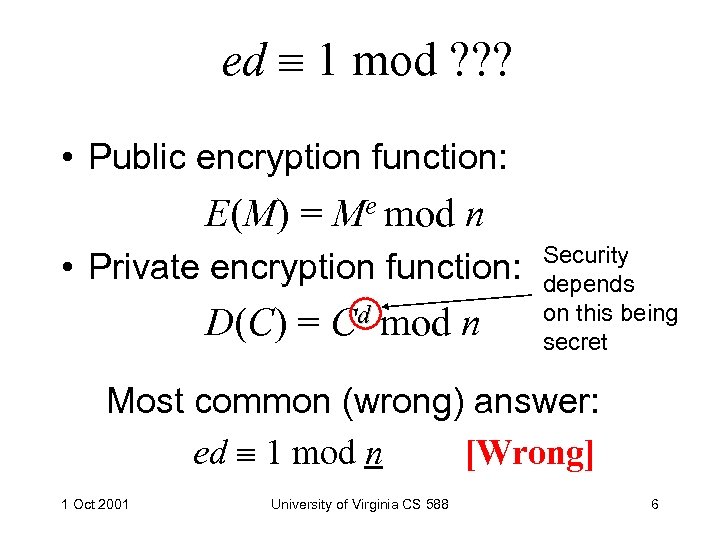

ed 1 mod ? ? ? • Public encryption function: E(M) = Me mod n • Private encryption function: D(C) = Cd mod n Security depends on this being secret Most common (wrong) answer: ed 1 mod n [Wrong] 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 6

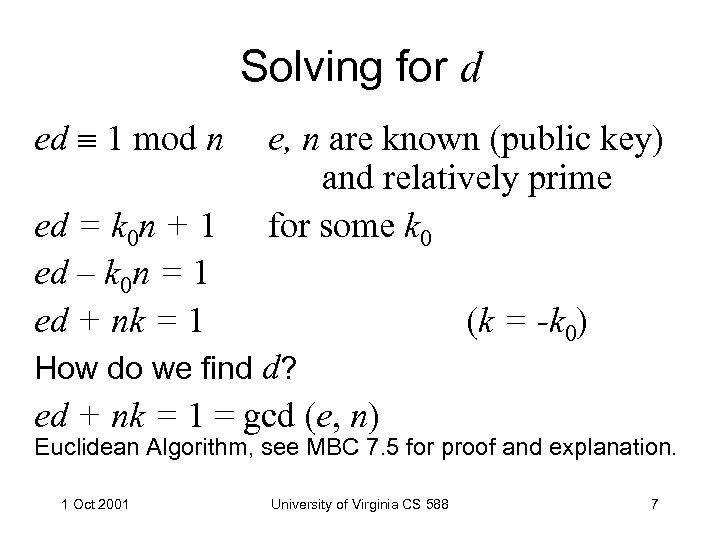

Solving for d ed 1 mod n ed = k 0 n + 1 ed – k 0 n = 1 ed + nk = 1 e, n are known (public key) and relatively prime for some k 0 (k = -k 0) How do we find d? ed + nk = 1 = gcd (e, n) Euclidean Algorithm, see MBC 7. 5 for proof and explanation. 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 7

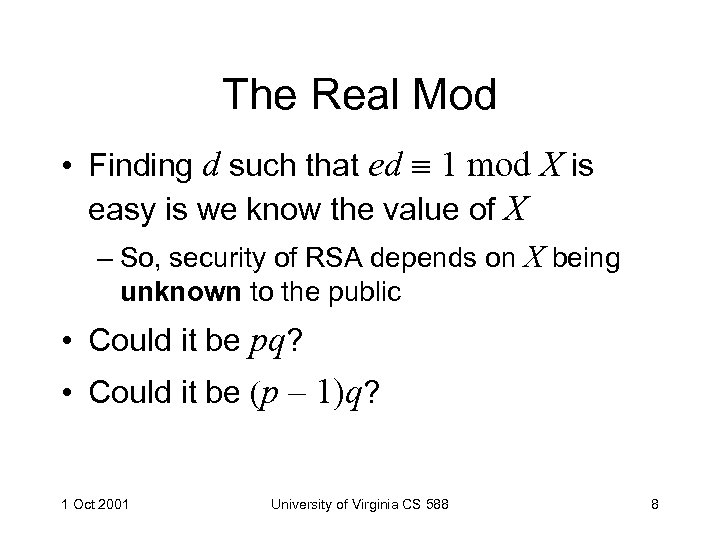

The Real Mod • Finding d such that ed 1 mod X is easy is we know the value of X – So, security of RSA depends on X being unknown to the public • Could it be pq? • Could it be (p – 1)q? 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 8

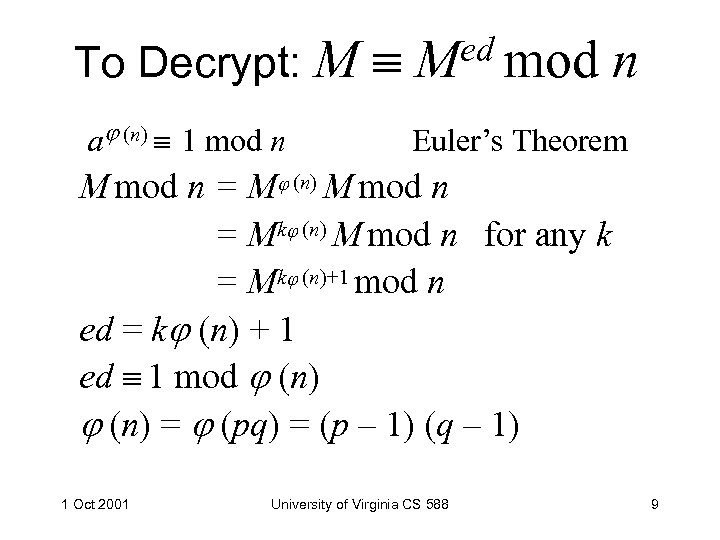

To Decrypt: M a (n) 1 mod n ed mod M n Euler’s Theorem M mod n = M (n) M mod n = Mk (n) M mod n for any k = Mk (n)+1 mod n ed = k (n) + 1 ed 1 mod (n) = (pq) = (p – 1) (q – 1) 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 9

Hashes 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 10

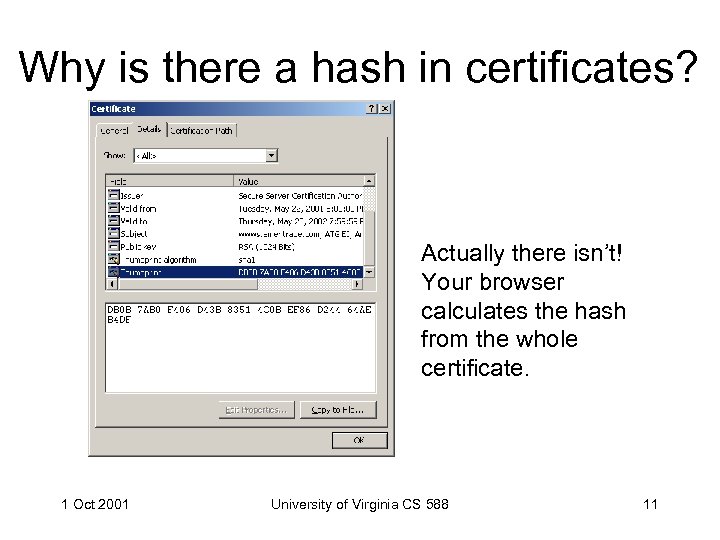

Why is there a hash in certificates? Actually there isn’t! Your browser calculates the hash from the whole certificate. 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 11

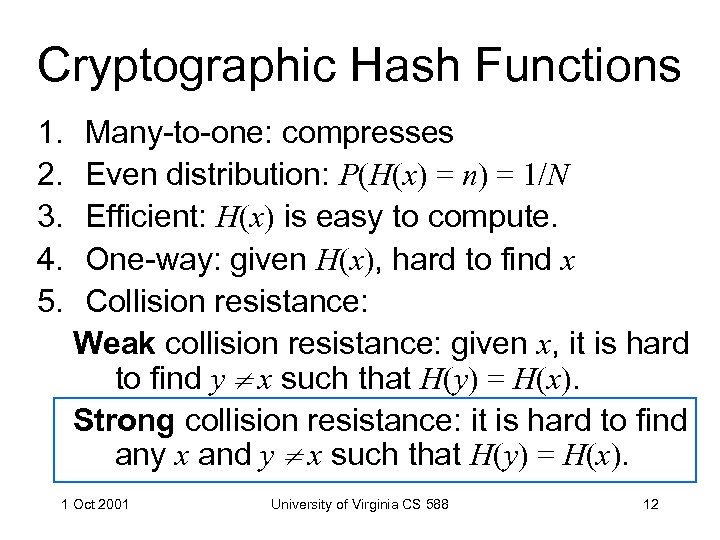

Cryptographic Hash Functions 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Many-to-one: compresses Even distribution: P(H(x) = n) = 1/N Efficient: H(x) is easy to compute. One-way: given H(x), hard to find x Collision resistance: Weak collision resistance: given x, it is hard to find y x such that H(y) = H(x). Strong collision resistance: it is hard to find any x and y x such that H(y) = H(x). 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 12

![IOU Request Protocol x EKRA[H(x)] Bob knows KUA Alice {KUA, KRA} y EKRA[H(x)] Bob IOU Request Protocol x EKRA[H(x)] Bob knows KUA Alice {KUA, KRA} y EKRA[H(x)] Bob](https://present5.com/presentation/332821dcdaef8bed94f363e66bc9fd4b/image-13.jpg)

IOU Request Protocol x EKRA[H(x)] Bob knows KUA Alice {KUA, KRA} y EKRA[H(x)] Bob picks x and y such that H(x) = H(y). 1 Oct 2001 Judge knows KUA University of Virginia CS 588 13

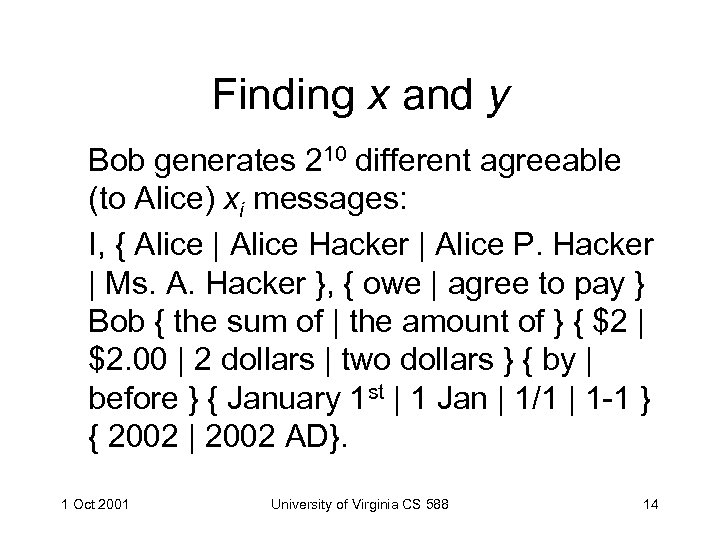

Finding x and y Bob generates 210 different agreeable (to Alice) xi messages: I, { Alice | Alice Hacker | Alice P. Hacker | Ms. A. Hacker }, { owe | agree to pay } Bob { the sum of | the amount of } { $2 | $2. 00 | 2 dollars | two dollars } { by | before } { January 1 st | 1 Jan | 1/1 | 1 -1 } { 2002 | 2002 AD}. 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 14

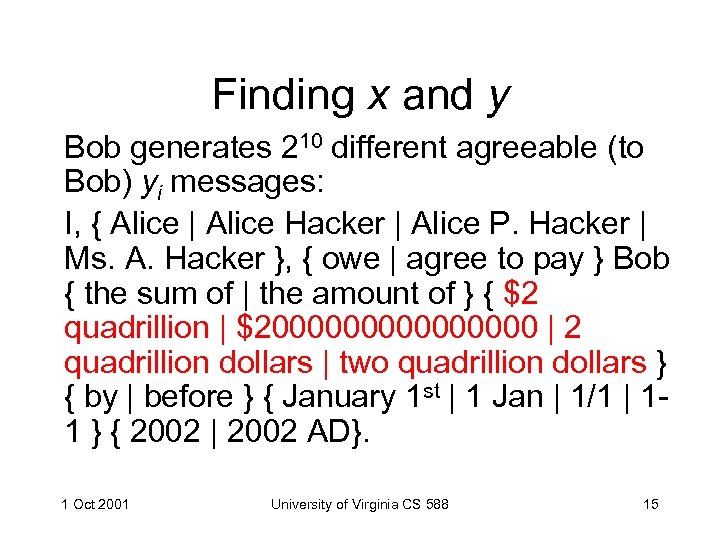

Finding x and y Bob generates 210 different agreeable (to Bob) yi messages: I, { Alice | Alice Hacker | Alice P. Hacker | Ms. A. Hacker }, { owe | agree to pay } Bob { the sum of | the amount of } { $2 quadrillion | $200000000 | 2 quadrillion dollars | two quadrillion dollars } { by | before } { January 1 st | 1 Jan | 1/1 | 11 } { 2002 | 2002 AD}. 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 15

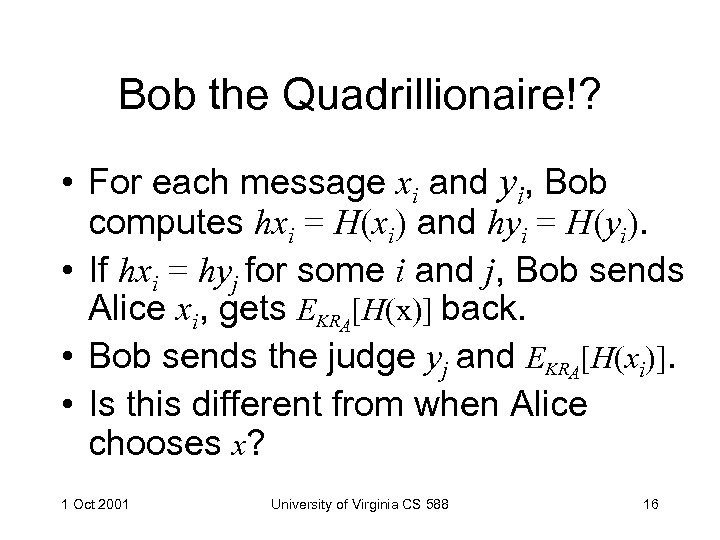

Bob the Quadrillionaire!? • For each message xi and yi, Bob computes hxi = H(xi) and hyi = H(yi). • If hxi = hyj for some i and j, Bob sends Alice xi, gets EKRA[H(x)] back. • Bob sends the judge yj and EKRA[H(xi)]. • Is this different from when Alice chooses x? 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 16

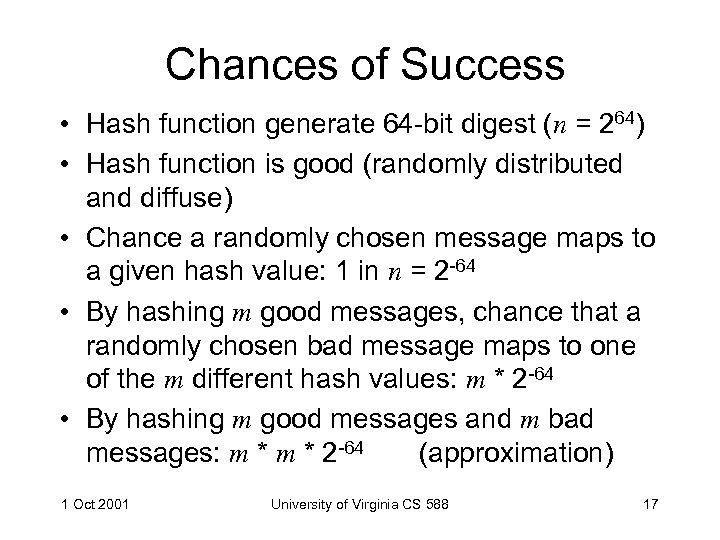

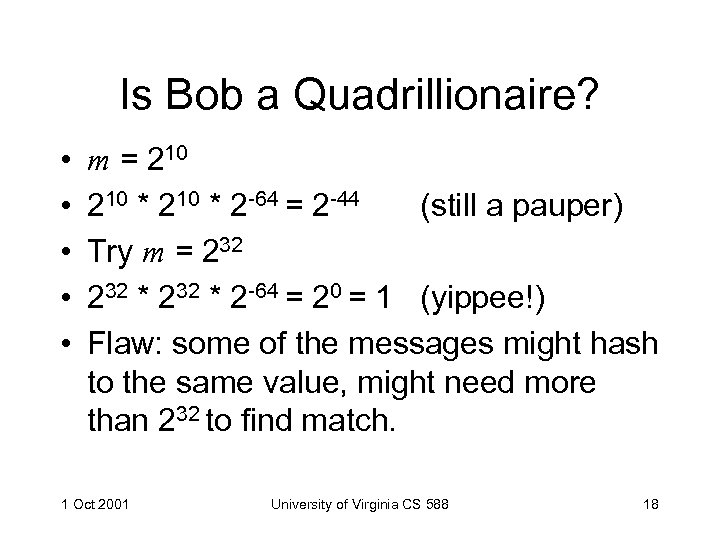

Chances of Success • Hash function generate 64 -bit digest (n = 264) • Hash function is good (randomly distributed and diffuse) • Chance a randomly chosen message maps to a given hash value: 1 in n = 2 -64 • By hashing m good messages, chance that a randomly chosen bad message maps to one of the m different hash values: m * 2 -64 • By hashing m good messages and m bad messages: m * 2 -64 (approximation) 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 17

Is Bob a Quadrillionaire? • • • m = 210 * 2 -64 = 2 -44 (still a pauper) Try m = 232 * 2 -64 = 20 = 1 (yippee!) Flaw: some of the messages might hash to the same value, might need more than 232 to find match. 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 18

Birthday “Paradox” What is the probability that two people in this room have the same birthday? 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 19

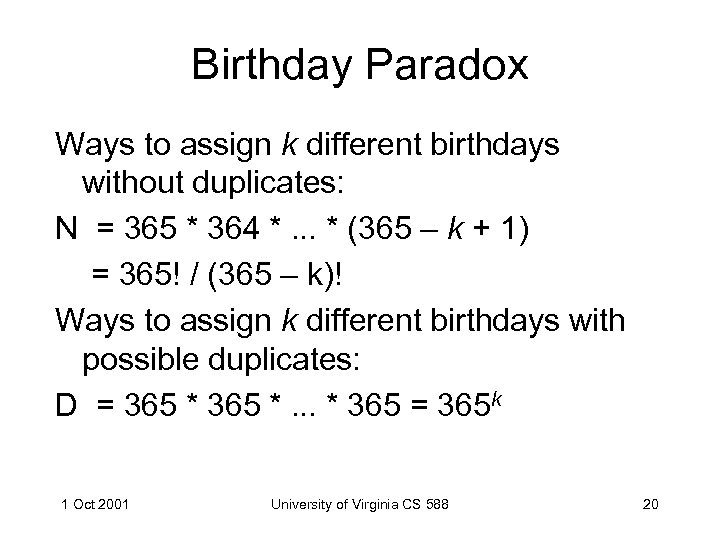

Birthday Paradox Ways to assign k different birthdays without duplicates: N = 365 * 364 *. . . * (365 – k + 1) = 365! / (365 – k)! Ways to assign k different birthdays with possible duplicates: D = 365 *. . . * 365 = 365 k 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 20

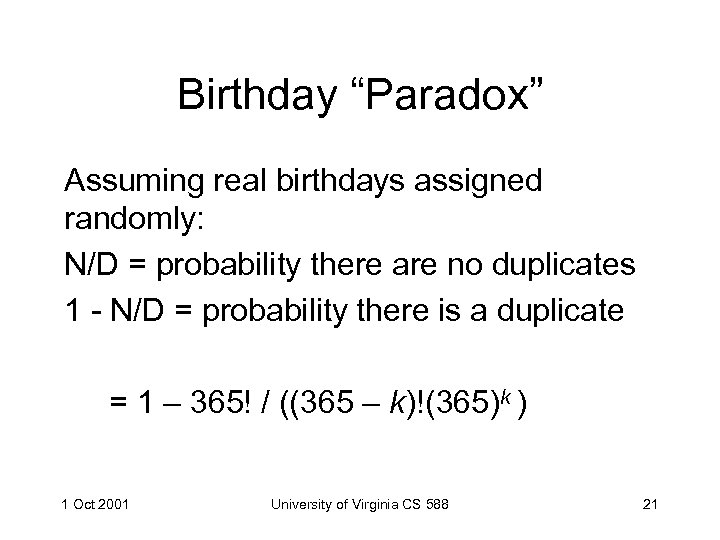

Birthday “Paradox” Assuming real birthdays assigned randomly: N/D = probability there are no duplicates 1 - N/D = probability there is a duplicate = 1 – 365! / ((365 – k)!(365)k ) 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 21

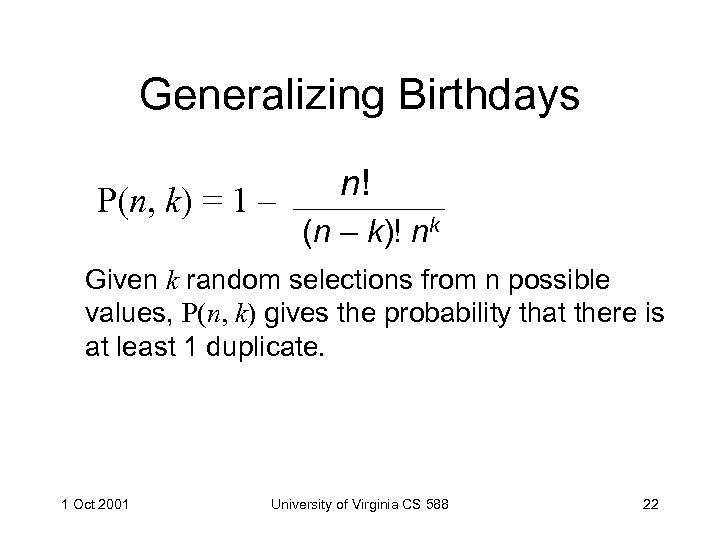

Generalizing Birthdays P(n, k) = 1 – n! (n – k)! nk Given k random selections from n possible values, P(n, k) gives the probability that there is at least 1 duplicate. 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 22

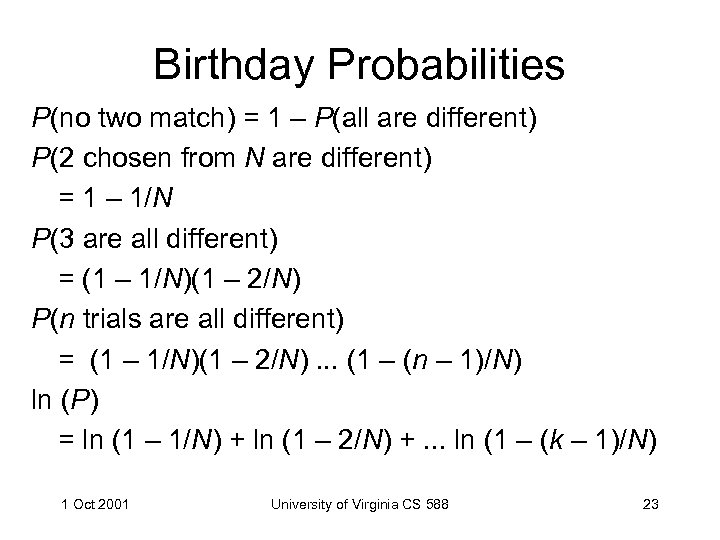

Birthday Probabilities P(no two match) = 1 – P(all are different) P(2 chosen from N are different) = 1 – 1/N P(3 are all different) = (1 – 1/N)(1 – 2/N) P(n trials are all different) = (1 – 1/N)(1 – 2/N). . . (1 – (n – 1)/N) ln (P) = ln (1 – 1/N) + ln (1 – 2/N) +. . . ln (1 – (k – 1)/N) 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 23

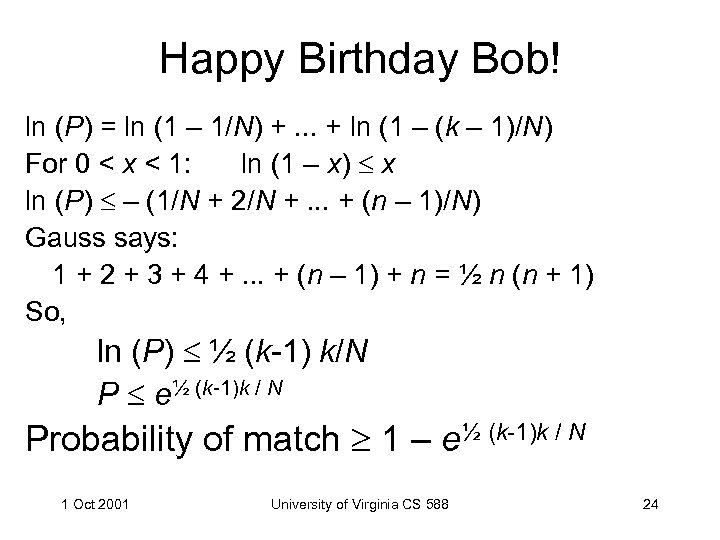

Happy Birthday Bob! ln (P) = ln (1 – 1/N) +. . . + ln (1 – (k – 1)/N) For 0 < x < 1: ln (1 – x) x ln (P) – (1/N + 2/N +. . . + (n – 1)/N) Gauss says: 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 +. . . + (n – 1) + n = ½ n (n + 1) So, ln (P) ½ (k-1) k/N P e½ (k-1)k / N Probability of match 1 – e½ (k-1)k / N 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 24

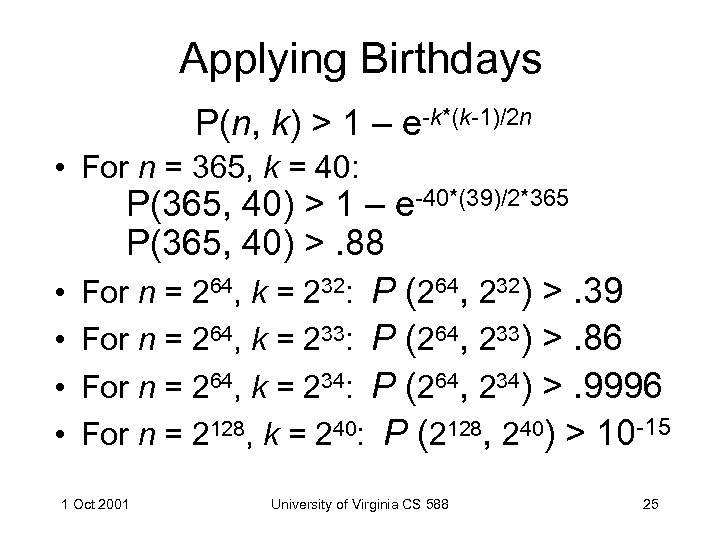

Applying Birthdays P(n, k) > 1 – e-k*(k-1)/2 n • For n = 365, k = 40: • • P(365, 40) > 1 – e-40*(39)/2*365 P(365, 40) >. 88 For n = 264, k = 232: P (264, 232) >. 39 For n = 264, k = 233: P (264, 233) >. 86 For n = 264, k = 234: P (264, 234) >. 9996 For n = 2128, k = 240: P (2128, 240) > 10 -15 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 25

Finding Problem Set Partners • Simple way: – Ask people in the class if they want to work with you • Problems: – You face rejection and ridicule if they say no • Can you find partners without revealing your wishes unless they are reciprocated? – Identify people who want to work together, but don’t reveal anything about anyone’s desires to work with people who don’t want to work with them 1 Oct 2001 University of Virginia CS 588 26

332821dcdaef8bed94f363e66bc9fd4b.ppt