8421faf5b0f0d79cfcd086f5c09fa739.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 92

LAW OF TORTS

LAW OF TORTS

Essentials of Tort Law Origins Historically dealt with "duty" owed to everyone you haven't agreed with in advance "Tort" = “Wrong” The law of negligence Personal injury Property damage Not for economic losses

Essentials of Tort Law Origins Historically dealt with "duty" owed to everyone you haven't agreed with in advance "Tort" = “Wrong” The law of negligence Personal injury Property damage Not for economic losses

WHAT IS A TORT? • A tort is a civil wrong • That (wrong) is based a breach of a duty imposed by law • Which (breach) gives rise to a (personal) civil right of action for a remedy not exclusive to another area of law

WHAT IS A TORT? • A tort is a civil wrong • That (wrong) is based a breach of a duty imposed by law • Which (breach) gives rise to a (personal) civil right of action for a remedy not exclusive to another area of law

Tort Law Operation Must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions that you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour “Negligence is the omission to do something which a reasonable man, guided upon those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs, would do, or doing something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do. ”

Tort Law Operation Must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions that you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour “Negligence is the omission to do something which a reasonable man, guided upon those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs, would do, or doing something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do. ”

Reasonable Care -- The "reasonable man" test “The reasonable man is a mythical creature of the law whose conduct is the standard by which the Courts measure the conduct of all other persons and find it to be proper or improper in particular circumstances as they may exist from time to time. He is not an extraordinary or unusual creature; he is not superhuman; he is not required to display the highest skill of which anyone is capable; his is not a genius who can perform uncommon feats, nor is he possessed of unusual powers of foresight. He is a person of normal intelligence who makes prudence a guide to his conduct. He does nothing that a prudent man would not do and does not omit to do anything that a prudent man would do. His conduct is guided by considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs. His conduct is the standard ‘adopted in the community by persons of ordinary intelligence and prudence’. ”

Reasonable Care -- The "reasonable man" test “The reasonable man is a mythical creature of the law whose conduct is the standard by which the Courts measure the conduct of all other persons and find it to be proper or improper in particular circumstances as they may exist from time to time. He is not an extraordinary or unusual creature; he is not superhuman; he is not required to display the highest skill of which anyone is capable; his is not a genius who can perform uncommon feats, nor is he possessed of unusual powers of foresight. He is a person of normal intelligence who makes prudence a guide to his conduct. He does nothing that a prudent man would not do and does not omit to do anything that a prudent man would do. His conduct is guided by considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs. His conduct is the standard ‘adopted in the community by persons of ordinary intelligence and prudence’. ”

The "Reasonable Engineer or Geoscientist" “How do you test whether this act or failure is negligent? In an ordinary case it is generally said, that you judge that by the action of the man in the street. He is the ordinary man. In one case it has been said that you judge it by the conduct of the man on the top of a Clapham omnibus. He is the ordinary man. But where you get a situation which involves the use of some special skill or competence, then the test whethere has been negligence or not is not the test of the man on the top of a Clapham omnibus, because he has not got this special skill. The test is the standard of the ordinary skilled man exercising and professing to have that special skill. A man need not possess the highest expert skill at the risk of being found negligent. It is well established law that it is sufficient if he exercises the ordinary skill of an ordinary competent man exercising that particular art. ”

The "Reasonable Engineer or Geoscientist" “How do you test whether this act or failure is negligent? In an ordinary case it is generally said, that you judge that by the action of the man in the street. He is the ordinary man. In one case it has been said that you judge it by the conduct of the man on the top of a Clapham omnibus. He is the ordinary man. But where you get a situation which involves the use of some special skill or competence, then the test whethere has been negligence or not is not the test of the man on the top of a Clapham omnibus, because he has not got this special skill. The test is the standard of the ordinary skilled man exercising and professing to have that special skill. A man need not possess the highest expert skill at the risk of being found negligent. It is well established law that it is sufficient if he exercises the ordinary skill of an ordinary competent man exercising that particular art. ”

Application of Tort Law to Commercial Transactions Historically, liability had to follow contractual chain Manufacturer ↓ Distributor ↓ Consumer

Application of Tort Law to Commercial Transactions Historically, liability had to follow contractual chain Manufacturer ↓ Distributor ↓ Consumer

Who is my "neighbour" and what is "foreseeable"? • There must be a "sufficiently close relationship between the parties" (proximity) to "justify imposition of a duty" and • There must be no "policy considerations" to prevent the imposition of liability Very complicated to determine, but the number of people to whom a duty is owed is probably expanding

Who is my "neighbour" and what is "foreseeable"? • There must be a "sufficiently close relationship between the parties" (proximity) to "justify imposition of a duty" and • There must be no "policy considerations" to prevent the imposition of liability Very complicated to determine, but the number of people to whom a duty is owed is probably expanding

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A TORT AND A CRIME • A crime is public /community wrong that gives rise to sanctions usually designated in a specified code. A tort is a civil ‘private’ wrong. • Action in criminal law is usually brought by the state or the Crown. Tort actions are usually brought by the victims of the tort. • The principal objective in criminal law is punishment. In torts, it is compensation

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A TORT AND A CRIME • A crime is public /community wrong that gives rise to sanctions usually designated in a specified code. A tort is a civil ‘private’ wrong. • Action in criminal law is usually brought by the state or the Crown. Tort actions are usually brought by the victims of the tort. • The principal objective in criminal law is punishment. In torts, it is compensation

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A TORT AND A CRIME • Differences in Procedure: Standard of Proof – • Criminal law: beyond reasonable doubt • Torts: on the balance of probabilities

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A TORT AND A CRIME • Differences in Procedure: Standard of Proof – • Criminal law: beyond reasonable doubt • Torts: on the balance of probabilities

THE AIMS OF TORT LAW • Loss distribution/adjustment: shifting losses from victims to perpetrators • Compensation: Through the award of (pecuniary) damages – The object of compensation is to place the victim in the position he/she was before the tort was committed. • Punishment: through exemplary or punitive damages. This is a secondary aim.

THE AIMS OF TORT LAW • Loss distribution/adjustment: shifting losses from victims to perpetrators • Compensation: Through the award of (pecuniary) damages – The object of compensation is to place the victim in the position he/she was before the tort was committed. • Punishment: through exemplary or punitive damages. This is a secondary aim.

INTERESTS PROTECTED IN TORT LAW • Personal security – Trespass – Negligence • Reputation – Defamation • Property – Trespass – Conversion • Economic and financial interests

INTERESTS PROTECTED IN TORT LAW • Personal security – Trespass – Negligence • Reputation – Defamation • Property – Trespass – Conversion • Economic and financial interests

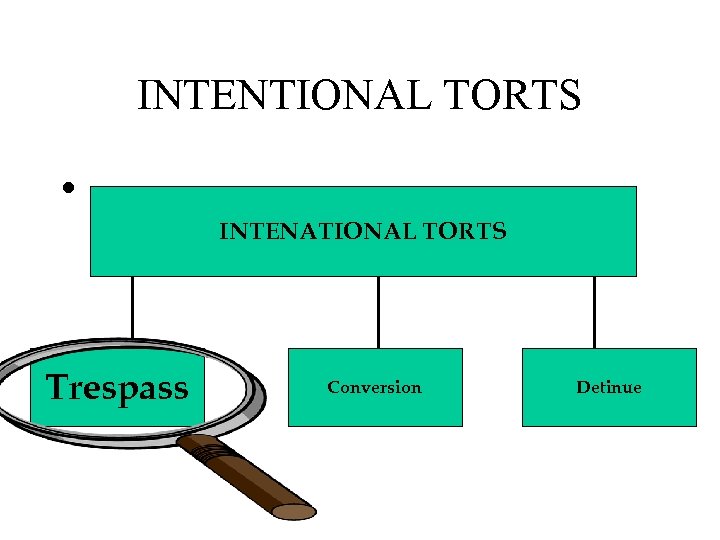

INTENTIONAL TORTS • INTENATIONAL TORTS Trespass Conversion Detinue

INTENTIONAL TORTS • INTENATIONAL TORTS Trespass Conversion Detinue

WHAT IS TRESPASS? • Intentional or negligent act of D which directly causes an injury to the P or his /her property without lawful justification • The Elements of Trespass: – fault: intentional or negligent act - injury must be direct – injury* may be to the P or to his/her property - No lawful justification

WHAT IS TRESPASS? • Intentional or negligent act of D which directly causes an injury to the P or his /her property without lawful justification • The Elements of Trespass: – fault: intentional or negligent act - injury must be direct – injury* may be to the P or to his/her property - No lawful justification

*INJURY IN TRESPASS • Injury = a breach of right, not necessarily actual damage • Trespass requires only proof of injury not actual damage

*INJURY IN TRESPASS • Injury = a breach of right, not necessarily actual damage • Trespass requires only proof of injury not actual damage

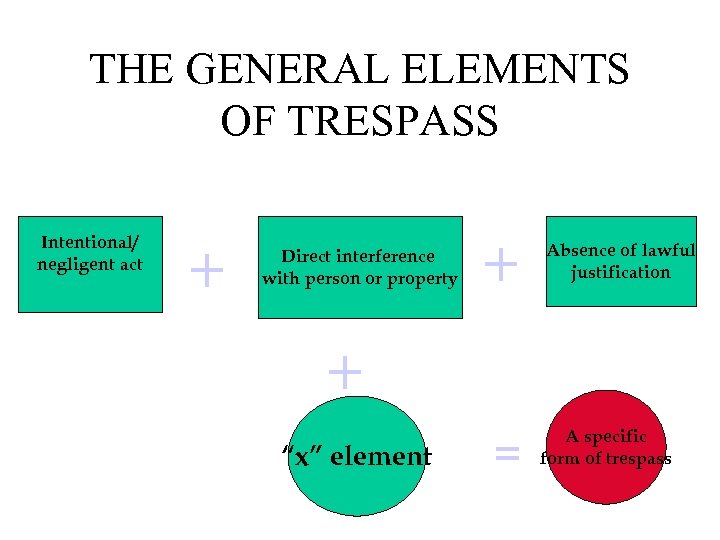

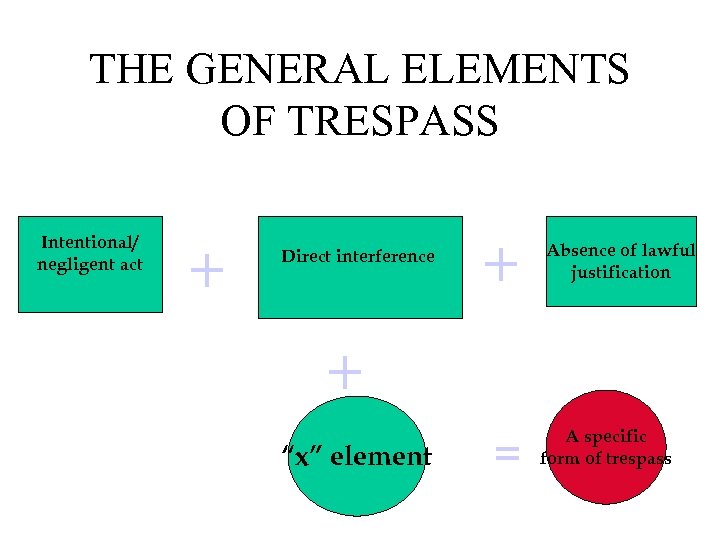

THE GENERAL ELEMENTS OF TRESPASS Intentional/ negligent act + Direct interference with person or property + Absence of lawful justification + “x” element = A specific form of trespass

THE GENERAL ELEMENTS OF TRESPASS Intentional/ negligent act + Direct interference with person or property + Absence of lawful justification + “x” element = A specific form of trespass

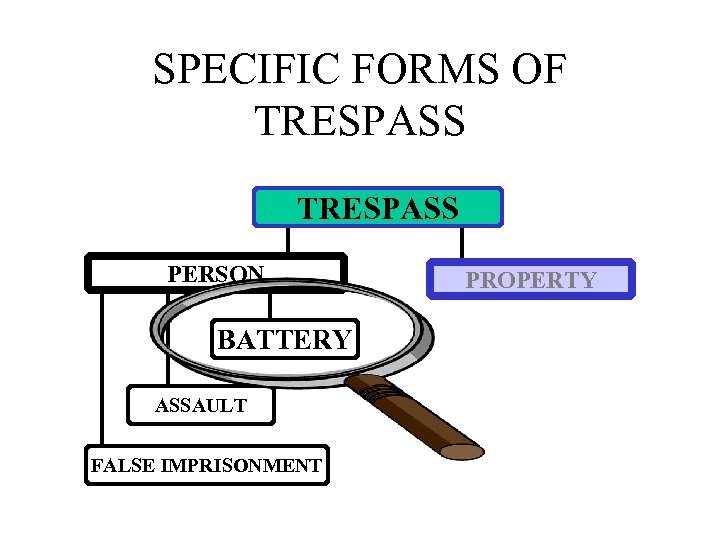

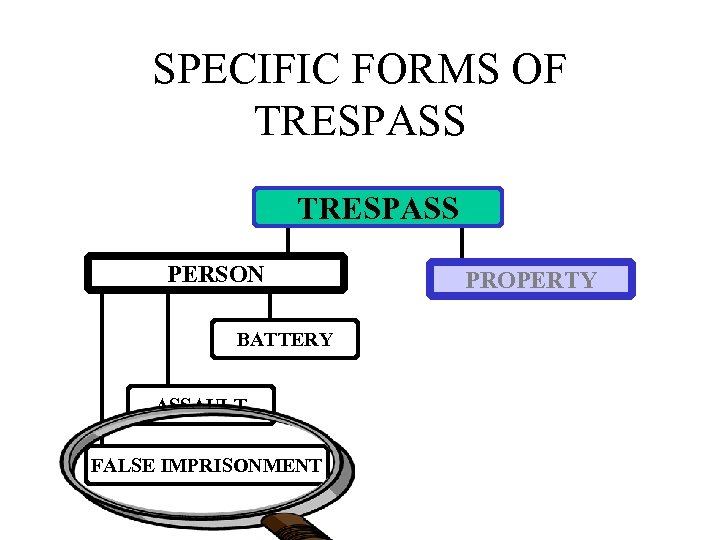

SPECIFIC FORMS OF TRESPASS PERSON BATTERY ASSAULT FALSE IMPRISONMENT PROPERTY

SPECIFIC FORMS OF TRESPASS PERSON BATTERY ASSAULT FALSE IMPRISONMENT PROPERTY

BATTERY • The intentional or negligent act of D which directly causes a physical interference with the body of P without lawful justification • The distinguishing element: physical interference with P’s body

BATTERY • The intentional or negligent act of D which directly causes a physical interference with the body of P without lawful justification • The distinguishing element: physical interference with P’s body

THE INTENTIONAL ACT IN BATTERY • No liability without intention • The intentional act = basic willful act + the consequences.

THE INTENTIONAL ACT IN BATTERY • No liability without intention • The intentional act = basic willful act + the consequences.

CAPACITY TO FORM THE INTENT • D is deemed capable of forming intent if he/she understands the nature of (‘intended’) his/her act • -Infants –Lunatics –Morris v Marsden –Hart v A. G. of Tasmania ( infant cutting another infant with razor blade)

CAPACITY TO FORM THE INTENT • D is deemed capable of forming intent if he/she understands the nature of (‘intended’) his/her act • -Infants –Lunatics –Morris v Marsden –Hart v A. G. of Tasmania ( infant cutting another infant with razor blade)

THE ACT MUST CAUSE PHYSICAL INTERFERENCE • The essence of the tort is the protection of the person of P. D’s act short of physical contact is therefore not a battery • The least touching of another could be battery – Cole v Turner (dicta per Holt CJ) • ‘The fundamental principle, plain and incontestable, is that every person’s body is inviolate’ ( per Goff LJ, Collins v Wilcock)

THE ACT MUST CAUSE PHYSICAL INTERFERENCE • The essence of the tort is the protection of the person of P. D’s act short of physical contact is therefore not a battery • The least touching of another could be battery – Cole v Turner (dicta per Holt CJ) • ‘The fundamental principle, plain and incontestable, is that every person’s body is inviolate’ ( per Goff LJ, Collins v Wilcock)

The Nature of the Physical Interference • Rixon v Star City Casino (D places hand on P’s shoulder to attract his attention; no battery) • Collins v Wilcock (Police officer holds D’s arm with a view to restraining her when D declines to answer questions and begins to walk away; battery) • Platt v Nutt

The Nature of the Physical Interference • Rixon v Star City Casino (D places hand on P’s shoulder to attract his attention; no battery) • Collins v Wilcock (Police officer holds D’s arm with a view to restraining her when D declines to answer questions and begins to walk away; battery) • Platt v Nutt

THE INJURY MUST BE CAUSED DIRECTLY • Injury should be the immediate: – Scott v Shepherd ( Lit squib/fireworks in market place) – Hutchins v Maughan (poisoned bait left for dog) – Southport v Esso Petroleum(Spilt oil on P’s beach)

THE INJURY MUST BE CAUSED DIRECTLY • Injury should be the immediate: – Scott v Shepherd ( Lit squib/fireworks in market place) – Hutchins v Maughan (poisoned bait left for dog) – Southport v Esso Petroleum(Spilt oil on P’s beach)

THE ACT MUST BE WITHOUT LAWFUL JUSTIFICATION • Consent is Lawful justification • Consent must be freely given by the P if P is able to understand the nature of the act • Lawful justification includes the lawful act of law enforcement officers – Wilson v. Marshall (D accused of assaulting police officer, held officer’s conduct not lawful)

THE ACT MUST BE WITHOUT LAWFUL JUSTIFICATION • Consent is Lawful justification • Consent must be freely given by the P if P is able to understand the nature of the act • Lawful justification includes the lawful act of law enforcement officers – Wilson v. Marshall (D accused of assaulting police officer, held officer’s conduct not lawful)

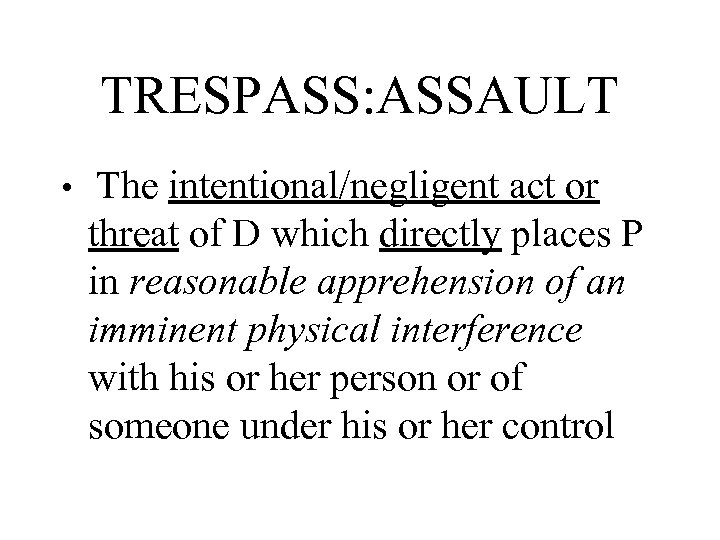

TRESPASS: ASSAULT • The intentional/negligent act or threat of D which directly places P in reasonable apprehension of an imminent physical interference with his or her person or of someone under his or her control

TRESPASS: ASSAULT • The intentional/negligent act or threat of D which directly places P in reasonable apprehension of an imminent physical interference with his or her person or of someone under his or her control

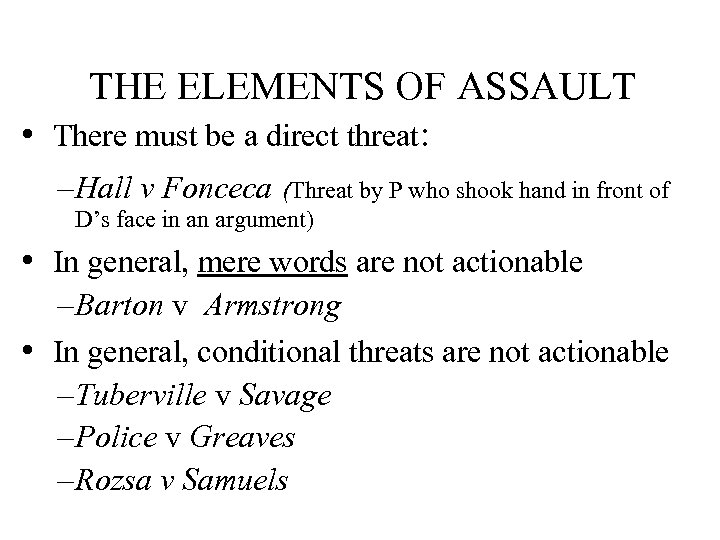

THE ELEMENTS OF ASSAULT • There must be a direct threat: – Hall v Fonceca (Threat by P who shook hand in front of D’s face in an argument) • In general, mere words are not actionable – Barton v Armstrong • In general, conditional threats are not actionable – Tuberville v Savage – Police v Greaves – Rozsa v Samuels

THE ELEMENTS OF ASSAULT • There must be a direct threat: – Hall v Fonceca (Threat by P who shook hand in front of D’s face in an argument) • In general, mere words are not actionable – Barton v Armstrong • In general, conditional threats are not actionable – Tuberville v Savage – Police v Greaves – Rozsa v Samuels

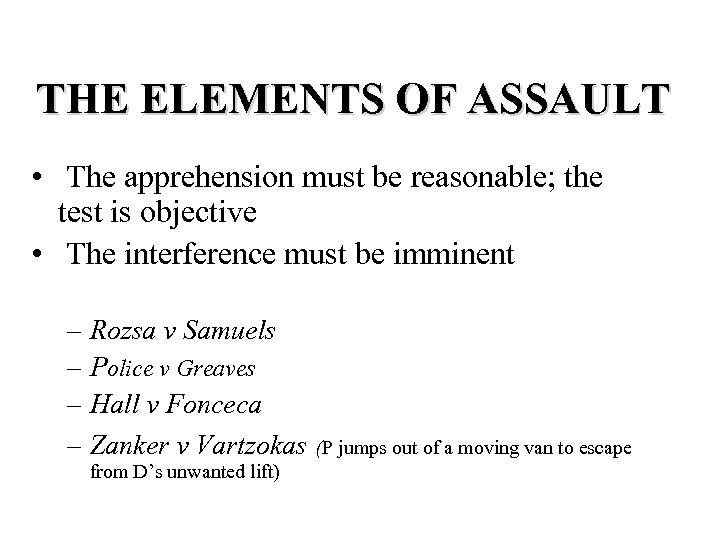

THE ELEMENTS OF ASSAULT • The apprehension must be reasonable; the test is objective • The interference must be imminent – Rozsa v Samuels – Police v Greaves – Hall v Fonceca – Zanker v Vartzokas (P jumps out of a moving van to escape from D’s unwanted lift)

THE ELEMENTS OF ASSAULT • The apprehension must be reasonable; the test is objective • The interference must be imminent – Rozsa v Samuels – Police v Greaves – Hall v Fonceca – Zanker v Vartzokas (P jumps out of a moving van to escape from D’s unwanted lift)

THE GENERAL ELEMENTS OF TRESPASS Intentional/ negligent act + Direct interference + Absence of lawful justification + “x” element = A specific form of trespass

THE GENERAL ELEMENTS OF TRESPASS Intentional/ negligent act + Direct interference + Absence of lawful justification + “x” element = A specific form of trespass

SPECIFIC FORMS OF TRESPASS PERSON BATTERY ASSAULT FALSE IMPRISONMENT PROPERTY

SPECIFIC FORMS OF TRESPASS PERSON BATTERY ASSAULT FALSE IMPRISONMENT PROPERTY

FALSE IMPRISONMENT • The intentional or negligent act of D which directly causes the total restraint of P and thereby confines him/her to a delimited area without lawful justification • The essential distinctive element is the total restraint

FALSE IMPRISONMENT • The intentional or negligent act of D which directly causes the total restraint of P and thereby confines him/her to a delimited area without lawful justification • The essential distinctive element is the total restraint

THE ELEMENTS OF THE TORT • It requires all the basic elements of trespass: – Intentional/negligent act – Directness – absence of lawful justification/consent , and • total restraint

THE ELEMENTS OF THE TORT • It requires all the basic elements of trespass: – Intentional/negligent act – Directness – absence of lawful justification/consent , and • total restraint

RESTRAINT IN FALSE IMPRISONMENT • The restraint must be total – Bird v Jones (passage over bridge) – The Balmain New Ferry Co v Robertson • Total restraint implies the absence of a reasonable means of escape – Burton v Davies (D refuses to allow P out of car) • Restraint may be total where D subjects P to his/her authority with no option to leave – Symes v Mahon (police officer arrests P by mistake) – Myer Stores v Soo

RESTRAINT IN FALSE IMPRISONMENT • The restraint must be total – Bird v Jones (passage over bridge) – The Balmain New Ferry Co v Robertson • Total restraint implies the absence of a reasonable means of escape – Burton v Davies (D refuses to allow P out of car) • Restraint may be total where D subjects P to his/her authority with no option to leave – Symes v Mahon (police officer arrests P by mistake) – Myer Stores v Soo

FORMS OF FALSE IMPRISONMENT • See the following Cases: – Cowell v. Corrective Services Commissioner of NSW (1988) Aust. Torts Reporter ¶ 81 -197. – Louis v. The Commonwealth of Australia 87 FLR 277. – Lippl v. Haines & Another (1989) Aust. Torts Reporter ¶ 80 -302; (1989) 18 NSWLR 620.

FORMS OF FALSE IMPRISONMENT • See the following Cases: – Cowell v. Corrective Services Commissioner of NSW (1988) Aust. Torts Reporter ¶ 81 -197. – Louis v. The Commonwealth of Australia 87 FLR 277. – Lippl v. Haines & Another (1989) Aust. Torts Reporter ¶ 80 -302; (1989) 18 NSWLR 620.

VOLUNTARY CASES • In general, there is no FI where one voluntarily submits to a form of restraint – Herd v Weardale (D refuses to allow P out of mine shaft) – Robinson v The Balmain New Ferry Co. (D refuses to allow P to leave unless P pays fare) – Lippl v Haines • Where there is no volition for restraint, the confinement may be FI (Bahner v Marwest Hotels Co. )

VOLUNTARY CASES • In general, there is no FI where one voluntarily submits to a form of restraint – Herd v Weardale (D refuses to allow P out of mine shaft) – Robinson v The Balmain New Ferry Co. (D refuses to allow P to leave unless P pays fare) – Lippl v Haines • Where there is no volition for restraint, the confinement may be FI (Bahner v Marwest Hotels Co. )

WORDS AND FALSE IMPRISONMENT • In general, words can constitute FI see Balkin & Davis pp. 55 to 56: “restraint… even by mere threat of force which intimidates a person into compliance without any laying on of hands” may be false imprisonment - Symes v Mahon

WORDS AND FALSE IMPRISONMENT • In general, words can constitute FI see Balkin & Davis pp. 55 to 56: “restraint… even by mere threat of force which intimidates a person into compliance without any laying on of hands” may be false imprisonment - Symes v Mahon

KNOWLEDGE IN FALSE IMPRISONMENT • The knowledge of the P at the moment of restraint is not essential. – Meering v Graham White Aviation – Murray v Ministry of Defense

KNOWLEDGE IN FALSE IMPRISONMENT • The knowledge of the P at the moment of restraint is not essential. – Meering v Graham White Aviation – Murray v Ministry of Defense

WHO IS LIABLE? THE AGGRIEVED CITIZEN OR THE POLICE OFFICER? • In each case, the issue is whether the police in making the arrest acted independently or as the agent of the citizen who promoted and caused the arrest – Dickenson v Waters Ltd – Bahner v Marwest Hotels Co

WHO IS LIABLE? THE AGGRIEVED CITIZEN OR THE POLICE OFFICER? • In each case, the issue is whether the police in making the arrest acted independently or as the agent of the citizen who promoted and caused the arrest – Dickenson v Waters Ltd – Bahner v Marwest Hotels Co

THE ‘MENTALLY ILL’ AND FALSE IMPRISONMENT l In Common Law, the lawfulness of an act of detention of a person must depend on "overriding necessity for the protection of himself and others’ per Harvey J in In re Hawke (1923) 40 WN (NSW) 58 l The situation under statute: l Watson v Marshall and Cade (1971) 124 CLR 621 l The Vic Mental Health Act 1959: Any person may be admitted into and detained in a psychiatric hospital upon the production of l (a) a request under the hand of some person in the prescribed form; l (b) a statement of the prescribed particulars; and l (c) a recommendation in the prescribed form of a medical practitioner based upon a personal examination of such person made not more than seven clear days before the admission of such person.

THE ‘MENTALLY ILL’ AND FALSE IMPRISONMENT l In Common Law, the lawfulness of an act of detention of a person must depend on "overriding necessity for the protection of himself and others’ per Harvey J in In re Hawke (1923) 40 WN (NSW) 58 l The situation under statute: l Watson v Marshall and Cade (1971) 124 CLR 621 l The Vic Mental Health Act 1959: Any person may be admitted into and detained in a psychiatric hospital upon the production of l (a) a request under the hand of some person in the prescribed form; l (b) a statement of the prescribed particulars; and l (c) a recommendation in the prescribed form of a medical practitioner based upon a personal examination of such person made not more than seven clear days before the admission of such person.

DAMAGES o False imprisonment is actionable per se o The failure to prove any actual financial loss does not mean that the plaintiff should recover nothing. The damages are at large. An interference with personal liberty even for a short period is not a trivial wrong. The injury to the plaintiff's dignity and to his feelings can be taken into account in assessing damages (Watson v Marshall and Cade )

DAMAGES o False imprisonment is actionable per se o The failure to prove any actual financial loss does not mean that the plaintiff should recover nothing. The damages are at large. An interference with personal liberty even for a short period is not a trivial wrong. The injury to the plaintiff's dignity and to his feelings can be taken into account in assessing damages (Watson v Marshall and Cade )

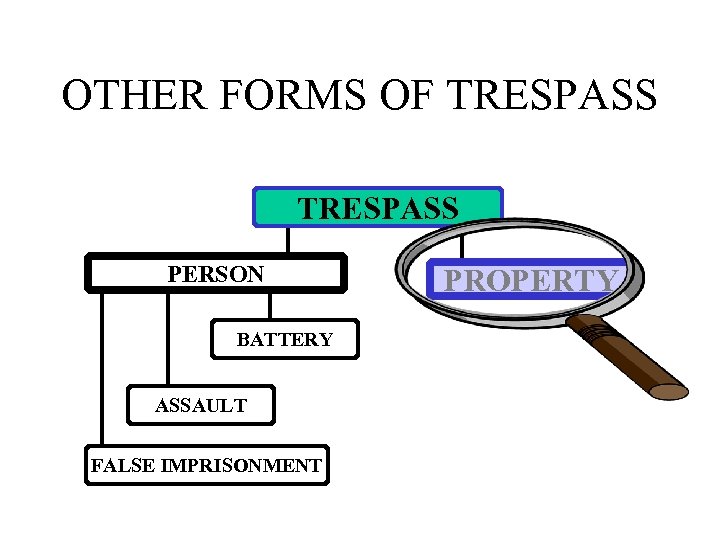

OTHER FORMS OF TRESPASS PERSON BATTERY ASSAULT FALSE IMPRISONMENT PROPERTY

OTHER FORMS OF TRESPASS PERSON BATTERY ASSAULT FALSE IMPRISONMENT PROPERTY

TRESPASS TO PROPERTY LAND GOODS/CHATTELS

TRESPASS TO PROPERTY LAND GOODS/CHATTELS

TRESPASS TO LAND • The intentional or negligent act of D which directly interferes with the plaintiff’s exclusive possession of land

TRESPASS TO LAND • The intentional or negligent act of D which directly interferes with the plaintiff’s exclusive possession of land

THE NATURE OF THE TORT • Land includes the actual soil/dirt, the structures/plants on it and the airspace above it • Cujus est solum ejus est usque ad coelum et inferos –Bernstein of Leigh v Skyways & General Ltd –Kelson v Imperial Tobacco

THE NATURE OF THE TORT • Land includes the actual soil/dirt, the structures/plants on it and the airspace above it • Cujus est solum ejus est usque ad coelum et inferos –Bernstein of Leigh v Skyways & General Ltd –Kelson v Imperial Tobacco

STATUTORY EASEMENTS • Conveyancing Act 1919 s 88 K (NSW) – 1. The Court may make an order imposing an easement over land if the easement is reasonably necessary for the effective use or development of other land that will have the benefit of the easement. – 2. Such an order may be made only if the Court is satisfied that: • (a) use of the land having the benefit of the easement will not be inconsistent with the public interest, and • (b) the owner of the land to be burdened by the easement and each other person having an estate or interest in that land …can be adequately compensated for any loss or other disadvantage that will arise from imposition of the easement • all reasonable attempts have been made by the applicant for the order to obtain the easement or an easement having the same effect but have been unsuccessful

STATUTORY EASEMENTS • Conveyancing Act 1919 s 88 K (NSW) – 1. The Court may make an order imposing an easement over land if the easement is reasonably necessary for the effective use or development of other land that will have the benefit of the easement. – 2. Such an order may be made only if the Court is satisfied that: • (a) use of the land having the benefit of the easement will not be inconsistent with the public interest, and • (b) the owner of the land to be burdened by the easement and each other person having an estate or interest in that land …can be adequately compensated for any loss or other disadvantage that will arise from imposition of the easement • all reasonable attempts have been made by the applicant for the order to obtain the easement or an easement having the same effect but have been unsuccessful

RESTRICTIONS ON STATUTORY EASEMENTS • ‘Property rights are valuable rights and the court should not lightly interfere with [such] property rights… [the section] does not exist for people build right up to the boundary of their property [or] build without adequate access and then expect others to make their land available for access’ per Young J Hanny v Lewis (1999) NSW Conv. R 55 -879 at 56 -875 • ‘Developers have a responsibility to act reasonably as do the proprietors of adjoining land the developers should not just proceed as if they would automatically get what they seek without negotiations’ (per Windeyer J Goodwin v Yee Holdings Pty Ltd (1997) 8 BPR)

RESTRICTIONS ON STATUTORY EASEMENTS • ‘Property rights are valuable rights and the court should not lightly interfere with [such] property rights… [the section] does not exist for people build right up to the boundary of their property [or] build without adequate access and then expect others to make their land available for access’ per Young J Hanny v Lewis (1999) NSW Conv. R 55 -879 at 56 -875 • ‘Developers have a responsibility to act reasonably as do the proprietors of adjoining land the developers should not just proceed as if they would automatically get what they seek without negotiations’ (per Windeyer J Goodwin v Yee Holdings Pty Ltd (1997) 8 BPR)

The Issue of Compensation • 88 K (2) Such an order may be made only if the Court is satisfied that: the owner of the land to be burdened by the easement and each other person having an estate or interest in that land …can be adequately compensated for any loss or other disadvantage that will arise from imposition of the easement • Adequate compensation: (Wengarin Pty Ltd v Byron Shire Council [1999] NSWSC 485) – – the diminished market value of the servient land associated costs that would be caused to the owner loss of amenities such as peace and quite where assessment proves difficult, the court may assess compensation on a percentage of the profits that would be made from the use of the easement

The Issue of Compensation • 88 K (2) Such an order may be made only if the Court is satisfied that: the owner of the land to be burdened by the easement and each other person having an estate or interest in that land …can be adequately compensated for any loss or other disadvantage that will arise from imposition of the easement • Adequate compensation: (Wengarin Pty Ltd v Byron Shire Council [1999] NSWSC 485) – – the diminished market value of the servient land associated costs that would be caused to the owner loss of amenities such as peace and quite where assessment proves difficult, the court may assess compensation on a percentage of the profits that would be made from the use of the easement

Neighbouring land Access and Utility Service Orders • The Access to Neighbouring Land Act 2000 ss 11 and 13 – (1) A Local Court may make a neighbouring land access /utility service access order if it is satisfied that access to land is required for the purpose of carrying out work on or in connection with a utility service situated on the land it is satisfied that it is appropriate to make the order in the circumstances of the case – (2) The Court must not make a utility service access order unless it is satisfied: – (a) that the applicant has made a reasonable effort to reach agreement with every person whose consent to access is required as to the access and carrying out of the work, and – (b) if the requirement to give notice has not been waived, that the applicant has given notice of the application in accordance with [the Act]

Neighbouring land Access and Utility Service Orders • The Access to Neighbouring Land Act 2000 ss 11 and 13 – (1) A Local Court may make a neighbouring land access /utility service access order if it is satisfied that access to land is required for the purpose of carrying out work on or in connection with a utility service situated on the land it is satisfied that it is appropriate to make the order in the circumstances of the case – (2) The Court must not make a utility service access order unless it is satisfied: – (a) that the applicant has made a reasonable effort to reach agreement with every person whose consent to access is required as to the access and carrying out of the work, and – (b) if the requirement to give notice has not been waived, that the applicant has given notice of the application in accordance with [the Act]

![The Nature of D’s Act: A General Note • . . . [E]very invasion The Nature of D’s Act: A General Note • . . . [E]very invasion](https://present5.com/presentation/8421faf5b0f0d79cfcd086f5c09fa739/image-48.jpg) The Nature of D’s Act: A General Note • . . . [E]very invasion of private property, be it ever so minute, is a trespass. No man can set his foot upon my ground without my license, but he is liable to an action, though the damage be nothing. . If he admits the fact, he is bound to show by way of justification, that some positive law has empowered or excused him ( Entick v Carrington (1765) 16 St Tr 1029, 1066)

The Nature of D’s Act: A General Note • . . . [E]very invasion of private property, be it ever so minute, is a trespass. No man can set his foot upon my ground without my license, but he is liable to an action, though the damage be nothing. . If he admits the fact, he is bound to show by way of justification, that some positive law has empowered or excused him ( Entick v Carrington (1765) 16 St Tr 1029, 1066)

THE NATURE OF D’S ACT • The act must constitute some physical interference which disturbs P’s exclusive possession of the land – Victoria Racing Co. v Taylor – Barthust City Council v Saban – Lincoln Hunt v Willesse

THE NATURE OF D’S ACT • The act must constitute some physical interference which disturbs P’s exclusive possession of the land – Victoria Racing Co. v Taylor – Barthust City Council v Saban – Lincoln Hunt v Willesse

THE NATURE OF THE PLAINTIFF’S INTEREST IN THE LAND • P must have exclusive possession of the land at the time of the interference exclusion of all others

THE NATURE OF THE PLAINTIFF’S INTEREST IN THE LAND • P must have exclusive possession of the land at the time of the interference exclusion of all others

THE NATURE OF EXCLUSIVE POSSESSION • Exclusive possession is distinct from ownership. • Ownership refers to title in the land. Exclusive possession refers to physical holding of the land • Possession may be immediate or constructive • The nature of possession depends on the material possessed

THE NATURE OF EXCLUSIVE POSSESSION • Exclusive possession is distinct from ownership. • Ownership refers to title in the land. Exclusive possession refers to physical holding of the land • Possession may be immediate or constructive • The nature of possession depends on the material possessed

EXCLUSIVE POSSESSION: COOWNERS • In general, a co-owner cannot be liable in trespass in respect of the land he/she owns; but this is debatable where the ’trespassing’ co-owner is not in possession. (Greig v Greig) • A co-possessor can maintain an action against a trespasser (Coles Smith v Smith and Ors)¯

EXCLUSIVE POSSESSION: COOWNERS • In general, a co-owner cannot be liable in trespass in respect of the land he/she owns; but this is debatable where the ’trespassing’ co-owner is not in possession. (Greig v Greig) • A co-possessor can maintain an action against a trespasser (Coles Smith v Smith and Ors)¯

THE POSITION OF LICENSEES • A licensee is one who has the permission of P to enter or use land (belonging to P) • A licensee is a party not in possession, and can therefore not sue in trespass • A licensee for value however may be entitled to sue(E. R. Investments v Hugh)

THE POSITION OF LICENSEES • A licensee is one who has the permission of P to enter or use land (belonging to P) • A licensee is a party not in possession, and can therefore not sue in trespass • A licensee for value however may be entitled to sue(E. R. Investments v Hugh)

THE TRESPASSORY ACT • Preventing P’s access Waters v Maynard) • The continuation of the initial trespassory act is a continuing trespass • Where D enters land for purposes different from that for which P gave a license, D’s conduct may constitute trespass ab initio (Barker v R)

THE TRESPASSORY ACT • Preventing P’s access Waters v Maynard) • The continuation of the initial trespassory act is a continuing trespass • Where D enters land for purposes different from that for which P gave a license, D’s conduct may constitute trespass ab initio (Barker v R)

THE POSITION OF POLICE OFFICERS • Unless authorized by law, police officers have no special right of entry into any premises without consent of P ( Halliday v Neville) • A police officer charged with the duty of serving a summons must obtain the consent of the party in possession (Plenty v. Dillion )

THE POSITION OF POLICE OFFICERS • Unless authorized by law, police officers have no special right of entry into any premises without consent of P ( Halliday v Neville) • A police officer charged with the duty of serving a summons must obtain the consent of the party in possession (Plenty v. Dillion )

Police Officers; The Common Law Position • The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all forces of the Crown. It may be frail- its roof may shake- the wind may blow through it- the rain may enter- but the King of England cannot enter- all his force dares not cross the threshold of the ruined tenement. So be it- unless he has justification by law’. Southam v Smout [1964] 1 QB 308, 320.

Police Officers; The Common Law Position • The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all forces of the Crown. It may be frail- its roof may shake- the wind may blow through it- the rain may enter- but the King of England cannot enter- all his force dares not cross the threshold of the ruined tenement. So be it- unless he has justification by law’. Southam v Smout [1964] 1 QB 308, 320.

REMEDIES • • Ejectment Recovery of Possession Award of damages Injunction Parramatta CC v Lutz Campbelltown CC v Mackay XL Petroleum (NSW) v Caltex Oil

REMEDIES • • Ejectment Recovery of Possession Award of damages Injunction Parramatta CC v Lutz Campbelltown CC v Mackay XL Petroleum (NSW) v Caltex Oil

TRESPASS TO PROPERTY LAND GOODS/CHATTELS

TRESPASS TO PROPERTY LAND GOODS/CHATTELS

TRESPASS TO GOODS/CHATTEL • The intentional/negligent act of D which directly interferes with the plaintiff’s possession of a chattel without lawful justification • The P must have actual or constructive possession at the time of interference.

TRESPASS TO GOODS/CHATTEL • The intentional/negligent act of D which directly interferes with the plaintiff’s possession of a chattel without lawful justification • The P must have actual or constructive possession at the time of interference.

DAMAGES • It may not be actionable per se (Everitt v Martin)

DAMAGES • It may not be actionable per se (Everitt v Martin)

CONVERSION • The act of D in relation to another’s chattel which constitutes an unjustifiable denial of his/her title

CONVERSION • The act of D in relation to another’s chattel which constitutes an unjustifiable denial of his/her title

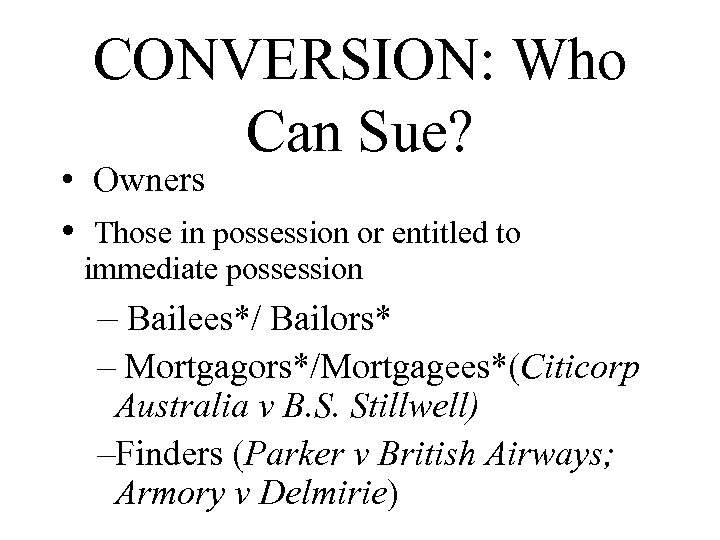

CONVERSION: Who Can Sue? • Owners • Those in possession or entitled to immediate possession – Bailees*/ Bailors* – Mortgagors*/Mortgagees*(Citicorp Australia v B. S. Stillwell) –Finders (Parker v British Airways; Armory v Delmirie)

CONVERSION: Who Can Sue? • Owners • Those in possession or entitled to immediate possession – Bailees*/ Bailors* – Mortgagors*/Mortgagees*(Citicorp Australia v B. S. Stillwell) –Finders (Parker v British Airways; Armory v Delmirie)

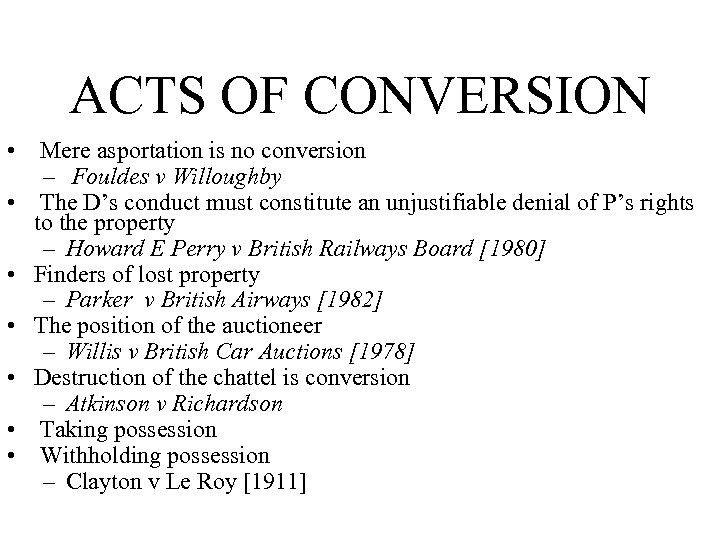

ACTS OF CONVERSION • Mere asportation is no conversion – Fouldes v Willoughby • The D’s conduct must constitute an unjustifiable denial of P’s rights to the property – Howard E Perry v British Railways Board [1980] • Finders of lost property – Parker v British Airways [1982] • The position of the auctioneer – Willis v British Car Auctions [1978] • Destruction of the chattel is conversion – Atkinson v Richardson • Taking possession • Withholding possession – Clayton v Le Roy [1911]

ACTS OF CONVERSION • Mere asportation is no conversion – Fouldes v Willoughby • The D’s conduct must constitute an unjustifiable denial of P’s rights to the property – Howard E Perry v British Railways Board [1980] • Finders of lost property – Parker v British Airways [1982] • The position of the auctioneer – Willis v British Car Auctions [1978] • Destruction of the chattel is conversion – Atkinson v Richardson • Taking possession • Withholding possession – Clayton v Le Roy [1911]

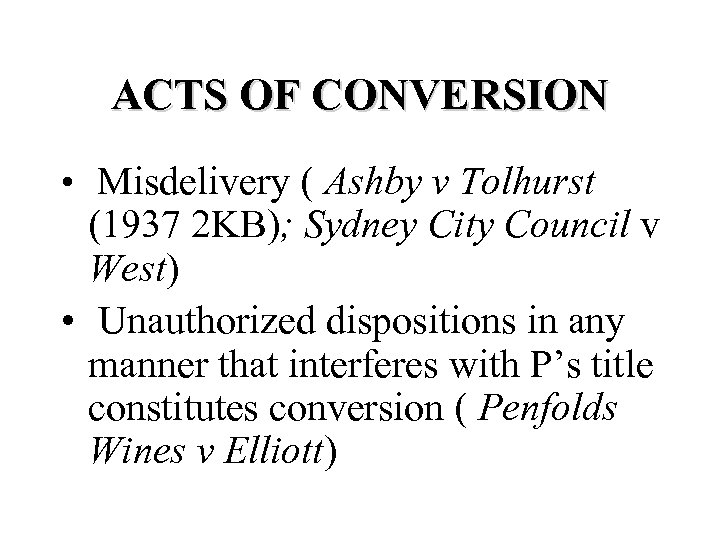

ACTS OF CONVERSION • Misdelivery ( Ashby v Tolhurst (1937 2 KB); Sydney City Council v West) • Unauthorized dispositions in any manner that interferes with P’s title constitutes conversion ( Penfolds Wines v Elliott)

ACTS OF CONVERSION • Misdelivery ( Ashby v Tolhurst (1937 2 KB); Sydney City Council v West) • Unauthorized dispositions in any manner that interferes with P’s title constitutes conversion ( Penfolds Wines v Elliott)

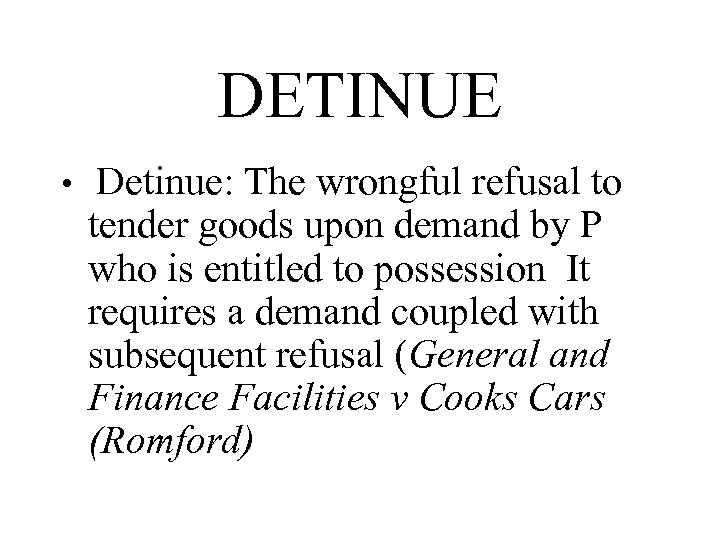

DETINUE • Detinue: The wrongful refusal to tender goods upon demand by P who is entitled to possession It requires a demand coupled with subsequent refusal (General and Finance Facilities v Cooks Cars (Romford)

DETINUE • Detinue: The wrongful refusal to tender goods upon demand by P who is entitled to possession It requires a demand coupled with subsequent refusal (General and Finance Facilities v Cooks Cars (Romford)

DAMAGES IN CONVERSION AND DETINUE • In conversion, damages usually take the form of pecuniary compensation • In detinue, the court may in appropriate circumstances order the return of the chattel • Damages in conversion are calculated as at the time of conversion; in detinue it is as at the time of judgment – The Medianal – Butler v The Egg and Pulp Marketing Board – The Winkfield – General and Finance Facilities v Cooks Cars (Romford)

DAMAGES IN CONVERSION AND DETINUE • In conversion, damages usually take the form of pecuniary compensation • In detinue, the court may in appropriate circumstances order the return of the chattel • Damages in conversion are calculated as at the time of conversion; in detinue it is as at the time of judgment – The Medianal – Butler v The Egg and Pulp Marketing Board – The Winkfield – General and Finance Facilities v Cooks Cars (Romford)

THE LAW OF TORTS Action on the Case for Indirect Injuries

THE LAW OF TORTS Action on the Case for Indirect Injuries

INDIRECT INTENTIONAL INJURIES • ACTION ON THE CASE FOR PHYSICAL INJURIES OR NERVOUS SHOCK • ACTION ON THE CASE REFERS TO ACTIONS BASED ON INJURIES THAT ARE CAUSED INDIRECTLY OR CONSEQUENTIALLY

INDIRECT INTENTIONAL INJURIES • ACTION ON THE CASE FOR PHYSICAL INJURIES OR NERVOUS SHOCK • ACTION ON THE CASE REFERS TO ACTIONS BASED ON INJURIES THAT ARE CAUSED INDIRECTLY OR CONSEQUENTIALLY

INDIRECT INTENTIONAL INJURIES: CASE LAW • Bird v Holbrook (trap set in garden) – D is liable in an action on the case for damages for intentional acts which are meant to cause damage to P and which in fact cause damage (to P)

INDIRECT INTENTIONAL INJURIES: CASE LAW • Bird v Holbrook (trap set in garden) – D is liable in an action on the case for damages for intentional acts which are meant to cause damage to P and which in fact cause damage (to P)

THE INTENTIONAL ACT • The intentional may be deliberate and preconceived(Bird v Holbrook ) • It may also be inferred or implied; the test for the inference is objective • Wilkinson v Downton [1897] • Janvier v Sweeney [1919]

THE INTENTIONAL ACT • The intentional may be deliberate and preconceived(Bird v Holbrook ) • It may also be inferred or implied; the test for the inference is objective • Wilkinson v Downton [1897] • Janvier v Sweeney [1919]

Action on the Case for Indirect Intentional Harm: Elements • D is liable in an action on the case for damages for intentional acts which are meant to cause damage to P and which in fact cause damage to P • The elements of this tort: – The act must be intentional – It must be one calculated to cause harm/damage – It must in fact cause harm/actual damage • Where D intends no harm from his act but the harm caused is one that is reasonably foreseeable, D’s intention to cause the resulting harm can be imputed/implied

Action on the Case for Indirect Intentional Harm: Elements • D is liable in an action on the case for damages for intentional acts which are meant to cause damage to P and which in fact cause damage to P • The elements of this tort: – The act must be intentional – It must be one calculated to cause harm/damage – It must in fact cause harm/actual damage • Where D intends no harm from his act but the harm caused is one that is reasonably foreseeable, D’s intention to cause the resulting harm can be imputed/implied

THE SCOPE OF THE RULE • The rule does not cover ‘pure’ mental stress or mere fright • The act must be reasonably capable of causing mental distress to a normal* person: – Bunyan v Jordan (1937) – Stevenson v Basham [1922]

THE SCOPE OF THE RULE • The rule does not cover ‘pure’ mental stress or mere fright • The act must be reasonably capable of causing mental distress to a normal* person: – Bunyan v Jordan (1937) – Stevenson v Basham [1922]

ONUS OF PROOF • In Common Law, he who asserts proves • Traditionally, in trespass D was required to disprove fault once P proved injury. Depending on whether the injury occurred on or off the highway ( Mc. Hale v Watson; Venning v Chin) • The current Australian position is contentious but seems to support the view that in off highway cases D is required to prove all the elements of the tort once P proves injury – Hackshaw v Shaw – Platt v Nutt – See Blay; ‘Onus of Proof of Consent in an Action for Trespass to the Person’ Vol. 61 ALJ (1987) 25 – But see Mc. Hugh J in See Secretary DHCS v JWB and SMB (Marion’s Case) 1992 175 CLR 218

ONUS OF PROOF • In Common Law, he who asserts proves • Traditionally, in trespass D was required to disprove fault once P proved injury. Depending on whether the injury occurred on or off the highway ( Mc. Hale v Watson; Venning v Chin) • The current Australian position is contentious but seems to support the view that in off highway cases D is required to prove all the elements of the tort once P proves injury – Hackshaw v Shaw – Platt v Nutt – See Blay; ‘Onus of Proof of Consent in an Action for Trespass to the Person’ Vol. 61 ALJ (1987) 25 – But see Mc. Hugh J in See Secretary DHCS v JWB and SMB (Marion’s Case) 1992 175 CLR 218

THE LAW OF TORTS Defences to Intentional Torts

THE LAW OF TORTS Defences to Intentional Torts

INTRODUCTION: The Concept of Defence • Broader Concept: The content of the Statement of Defence- The response to the P’s Statement of Claim-The basis for non-liability • Statement of Defence may contain: Denial – Objection to a point of law – Confession and avoidance: –

INTRODUCTION: The Concept of Defence • Broader Concept: The content of the Statement of Defence- The response to the P’s Statement of Claim-The basis for non-liability • Statement of Defence may contain: Denial – Objection to a point of law – Confession and avoidance: –

MISTAKE • An intentional conduct done under a misapprehension • Mistake is thus not the same as inevitable accident • Mistake is generally not a defence in tort law ( Rendell v Associated Finance Ltd, Symes v Mahon) •

MISTAKE • An intentional conduct done under a misapprehension • Mistake is thus not the same as inevitable accident • Mistake is generally not a defence in tort law ( Rendell v Associated Finance Ltd, Symes v Mahon) •

CONSENT • In a strict sense, consent is not a defence as such because in trespass, the absence of consent is an element of the tort – See: Blay; ‘Onus of Proof of Consent in an Action for Trespass to the Person’ Vol. 61 ALJ (1987) 25 – But Mc. Hugh J in See Secretary DHCS v JWB and SMB (Marion’s Case) 1992 175 CLR 218

CONSENT • In a strict sense, consent is not a defence as such because in trespass, the absence of consent is an element of the tort – See: Blay; ‘Onus of Proof of Consent in an Action for Trespass to the Person’ Vol. 61 ALJ (1987) 25 – But Mc. Hugh J in See Secretary DHCS v JWB and SMB (Marion’s Case) 1992 175 CLR 218

VALID CONSENT • To be valid, consent must be informed and procured without fraud or coercion: ( R v Williams; ) • To invalidate consent, fraud must relate directly to the agreement itself, and not to an incidental issue: (Papadimitropoulos v R (1957) 98 CLR 249)

VALID CONSENT • To be valid, consent must be informed and procured without fraud or coercion: ( R v Williams; ) • To invalidate consent, fraud must relate directly to the agreement itself, and not to an incidental issue: (Papadimitropoulos v R (1957) 98 CLR 249)

CONSENT IN SPORTS • In contact sports, consent is not necessarily a defence to foul play (Mc. Namara v Duncan; Hilton v Wallace) • To succeed in an action for trespass in contact sports however, the P must of course prove the relevant elements of the tort. – Giumelli v Johnston

CONSENT IN SPORTS • In contact sports, consent is not necessarily a defence to foul play (Mc. Namara v Duncan; Hilton v Wallace) • To succeed in an action for trespass in contact sports however, the P must of course prove the relevant elements of the tort. – Giumelli v Johnston

THE BURDEN OF PROOF • Since the absence of consent is a definitional element in trespass, it is for the P to prove absence of consent and not for the D to prove consent

THE BURDEN OF PROOF • Since the absence of consent is a definitional element in trespass, it is for the P to prove absence of consent and not for the D to prove consent

STATUTORY PROVISIONS ON CONSENT • Minors (Property and Contracts) Act 1970 (NSW) ss 14, 49 • Children & Young Persons (Care and Protection Act) 1998 (NSW) ss 174, 175

STATUTORY PROVISIONS ON CONSENT • Minors (Property and Contracts) Act 1970 (NSW) ss 14, 49 • Children & Young Persons (Care and Protection Act) 1998 (NSW) ss 174, 175

SELF DEFENCE, DEFENCE OF OTHERS • A P who is attacked or threatened with an attack, is allowed to use reasonable force to defend him/herself • In each case, the force used must be proportional to the threat; it must not be excessive. (Fontin v Katapodis) • D may also use reasonable force to defend a third party where he/she reasonably believes that the party is being attacked or being threatened

SELF DEFENCE, DEFENCE OF OTHERS • A P who is attacked or threatened with an attack, is allowed to use reasonable force to defend him/herself • In each case, the force used must be proportional to the threat; it must not be excessive. (Fontin v Katapodis) • D may also use reasonable force to defend a third party where he/she reasonably believes that the party is being attacked or being threatened

THE DEFENCE OF PROPERTY • D may use reasonable force to defend his/her property if he/she reasonably believes that the property is under attack or threatened • What is reasonable force will depend on the facts of each case, but it is debatable whether reasonable force includes ‘deadly force’

THE DEFENCE OF PROPERTY • D may use reasonable force to defend his/her property if he/she reasonably believes that the property is under attack or threatened • What is reasonable force will depend on the facts of each case, but it is debatable whether reasonable force includes ‘deadly force’

PROVOCATION • Provocation is not a defence in tort law. • It can only be used to avoid the award of exemplary damages: Fontin v Katapodis; Downham v Bellette (1986) Aust Torts Reports 80 -038

PROVOCATION • Provocation is not a defence in tort law. • It can only be used to avoid the award of exemplary damages: Fontin v Katapodis; Downham v Bellette (1986) Aust Torts Reports 80 -038

The Case for Allowing the Defence of Provocation • The relationship between provocation and contributory negligence • The implication of counterclaims • Note possible qualifications Fontin v Katapodis to: – Lane v Holloway – Murphy v Culhane – See Blay: ‘Provocation in Tort Liability: A Time for Reassessment’, QUT Law Journal, Vol. 4 (1988) pp. 151159.

The Case for Allowing the Defence of Provocation • The relationship between provocation and contributory negligence • The implication of counterclaims • Note possible qualifications Fontin v Katapodis to: – Lane v Holloway – Murphy v Culhane – See Blay: ‘Provocation in Tort Liability: A Time for Reassessment’, QUT Law Journal, Vol. 4 (1988) pp. 151159.

NECESSITY • The defence is allowed where an act which is otherwise a tort is done to save life or property: urgent situations of imminent peril

NECESSITY • The defence is allowed where an act which is otherwise a tort is done to save life or property: urgent situations of imminent peril

Urgent Situations of Imminent Peril • The situation must pose a threat to life or property to warrant the act: Southwark London B. Council v Williams • The defence is available in very strict circumstances R v Dudley and Stephens • D’s act must be reasonably necessary and not just convenient Murray v Mc. Murchy – In re F – Cope v Sharp

Urgent Situations of Imminent Peril • The situation must pose a threat to life or property to warrant the act: Southwark London B. Council v Williams • The defence is available in very strict circumstances R v Dudley and Stephens • D’s act must be reasonably necessary and not just convenient Murray v Mc. Murchy – In re F – Cope v Sharp

INSANITY • Insanity is not a defence as such to an intentional tort. • What is essential is whether D by reason of insanity was capable of forming the intent to commit the tort. (White v Pile; Morris v Marsden)

INSANITY • Insanity is not a defence as such to an intentional tort. • What is essential is whether D by reason of insanity was capable of forming the intent to commit the tort. (White v Pile; Morris v Marsden)

INFANTS • Minority is not a defence as such in torts. • What is essential is whether the D understood the nature of his/her conduct (Smith v Leurs; Hart v AG of Tasmania)

INFANTS • Minority is not a defence as such in torts. • What is essential is whether the D understood the nature of his/her conduct (Smith v Leurs; Hart v AG of Tasmania)

DISCIPLINE • PARENTS – A parent may use reasonable and moderate force to discipline a child. What is reasonable will depend on the age, mentality, and physique of the child and on the means and instrument used. (R v Terry)

DISCIPLINE • PARENTS – A parent may use reasonable and moderate force to discipline a child. What is reasonable will depend on the age, mentality, and physique of the child and on the means and instrument used. (R v Terry)

ILLEGALITY: Ex turpi causa non oritur actio • Persons who join in committing an illegal act have no legal rights inter se in relation to torts arising directly from that act. – Hegarty v Shine – Smith v Jenkins – Jackson v Harrison – Gala v Preston

ILLEGALITY: Ex turpi causa non oritur actio • Persons who join in committing an illegal act have no legal rights inter se in relation to torts arising directly from that act. – Hegarty v Shine – Smith v Jenkins – Jackson v Harrison – Gala v Preston

TRESPASS & CLA 2002 • s. 3 B(1)(a) Civil Liability Act (“CLA”) i. e. CLA does not apply to “intentional torts”, except Part 7 of the Act. • s. 52 (2) CLA subjective/objective test i. e. subjective ("…believes…" & "…perceives…")/ objective ("…reasonable response…") test. • s. 53(1)(a) & (b) CLA i. e. “and” = two limb test; "exceptional" and "harsh and unjust“ are not defined in the Act so s. 34 of the Interpretation Act 1987. • s. 54(1) & (2) CLA i. e. "Serious offence" and "offence" are criminal terms so reference should be made to the criminal law to confirm whether P's actions are covered by the provisions.

TRESPASS & CLA 2002 • s. 3 B(1)(a) Civil Liability Act (“CLA”) i. e. CLA does not apply to “intentional torts”, except Part 7 of the Act. • s. 52 (2) CLA subjective/objective test i. e. subjective ("…believes…" & "…perceives…")/ objective ("…reasonable response…") test. • s. 53(1)(a) & (b) CLA i. e. “and” = two limb test; "exceptional" and "harsh and unjust“ are not defined in the Act so s. 34 of the Interpretation Act 1987. • s. 54(1) & (2) CLA i. e. "Serious offence" and "offence" are criminal terms so reference should be made to the criminal law to confirm whether P's actions are covered by the provisions.