4f543913ba651210989d216d5d70eb77.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 87

LAW 503 International and Transnational Criminal Law and Procedure Assist. Prof. R. Murat ÖNOK 27. 09. 2013 - II

LAW 503 International and Transnational Criminal Law and Procedure Assist. Prof. R. Murat ÖNOK 27. 09. 2013 - II

INDEX 1. The ad hoc Tribunals Established by the UN SC A. Intro B. Establishment of the ICTY and the ICTR 2. Was the establishment of the ICTY (and ICTR) lawful? A. Relevant provisions of the UN Charter B. Why the establishment of the tribunals was lawful C. ICTY’s own view D. Summary 3. ICTY A. Basic Documents B. Legal Status of the ICTY C. Structure of the ICTY D. Qualifications and election of judges E. The Office of the Prosecutor F. The Registry

INDEX 1. The ad hoc Tribunals Established by the UN SC A. Intro B. Establishment of the ICTY and the ICTR 2. Was the establishment of the ICTY (and ICTR) lawful? A. Relevant provisions of the UN Charter B. Why the establishment of the tribunals was lawful C. ICTY’s own view D. Summary 3. ICTY A. Basic Documents B. Legal Status of the ICTY C. Structure of the ICTY D. Qualifications and election of judges E. The Office of the Prosecutor F. The Registry

INDEX G. Jurisdiction of the ICTY H. Relationship with national criminal jurisdiction I. General Principles of Criminal Law J. Investigation, Prosecution, and Enforcement of Sentences K. Co-operation with the ICTY L. ICTY’s Activity M. ICTY- Assessment 4. ICTR A. Events Leading to the Establishment of the ICTR B. Basics C. Legitimacy of the ICTR D. Characteristics of the ICTR E. Jurisdiction F. ICTR’s Activity G. Assessment 5. ‘The Mechanism’

INDEX G. Jurisdiction of the ICTY H. Relationship with national criminal jurisdiction I. General Principles of Criminal Law J. Investigation, Prosecution, and Enforcement of Sentences K. Co-operation with the ICTY L. ICTY’s Activity M. ICTY- Assessment 4. ICTR A. Events Leading to the Establishment of the ICTR B. Basics C. Legitimacy of the ICTR D. Characteristics of the ICTR E. Jurisdiction F. ICTR’s Activity G. Assessment 5. ‘The Mechanism’

1. The ad hoc Tribunals Established by the UN SC

1. The ad hoc Tribunals Established by the UN SC

A. Intro • Two international criminal tribunals were established in 1993 and 1994. • The first one, the International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) holds special importance because it was the first court entrusted with holding int’l. criminal trials 48 years after the Nuremberg and Tokyo experience. • Furthermore, the ICTR created the next year mirrors the ICTY. • Both tribunals set a precedent and a reference for the future permanent ICC. In particular, the successful operation of the ICTY was a catalyst to the establishment of the ICC.

A. Intro • Two international criminal tribunals were established in 1993 and 1994. • The first one, the International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) holds special importance because it was the first court entrusted with holding int’l. criminal trials 48 years after the Nuremberg and Tokyo experience. • Furthermore, the ICTR created the next year mirrors the ICTY. • Both tribunals set a precedent and a reference for the future permanent ICC. In particular, the successful operation of the ICTY was a catalyst to the establishment of the ICC.

B. Establishment of the ICTY and ICTR • The widespread and grave violations of human rights committed during the war by rival ethnic groups throughout the territory of the former Yugoslavia had caused the reaction of the world community. • The UN and the great states had made a weak effort in preventing the conflict and the related atrocities, hence they tried to make up by prosecuting the perpetrators, thus realizing justice and peace. • For that purpose, various UN SC Resolutions adopted throughout the conflict set the legal basis for the establishment of a tribunal. In chronological order, these resolutions are the following: - UN SC Res. 713 (25. 9. 1991): It was determined that the continuation of the situation constituted a threat to int’l. peace and security; - UN SC Res. 764 (13. 7. 1992): It was reaffirmed that all parties are bound to comply with the obligations under IHL and in particular the Geneva Conventions of 1949, and that persons who commit or order the commission of grave breaches of the Conventions are individually responsible in respect of such breaches.

B. Establishment of the ICTY and ICTR • The widespread and grave violations of human rights committed during the war by rival ethnic groups throughout the territory of the former Yugoslavia had caused the reaction of the world community. • The UN and the great states had made a weak effort in preventing the conflict and the related atrocities, hence they tried to make up by prosecuting the perpetrators, thus realizing justice and peace. • For that purpose, various UN SC Resolutions adopted throughout the conflict set the legal basis for the establishment of a tribunal. In chronological order, these resolutions are the following: - UN SC Res. 713 (25. 9. 1991): It was determined that the continuation of the situation constituted a threat to int’l. peace and security; - UN SC Res. 764 (13. 7. 1992): It was reaffirmed that all parties are bound to comply with the obligations under IHL and in particular the Geneva Conventions of 1949, and that persons who commit or order the commission of grave breaches of the Conventions are individually responsible in respect of such breaches.

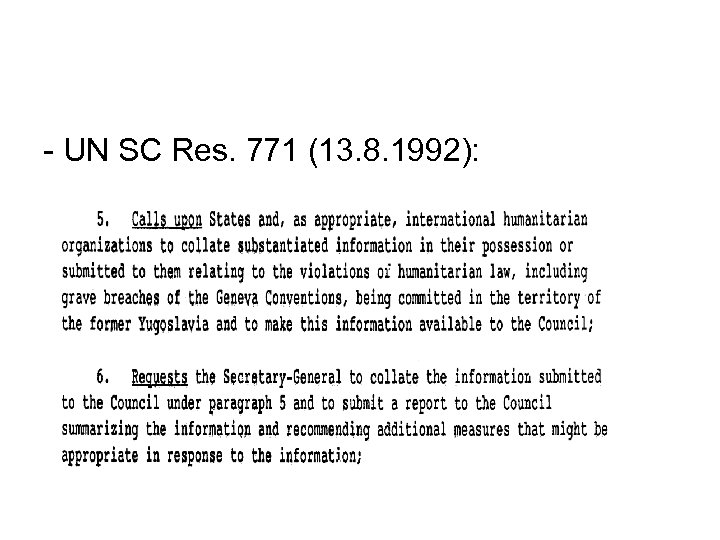

- UN SC Res. 771 (13. 8. 1992):

- UN SC Res. 771 (13. 8. 1992):

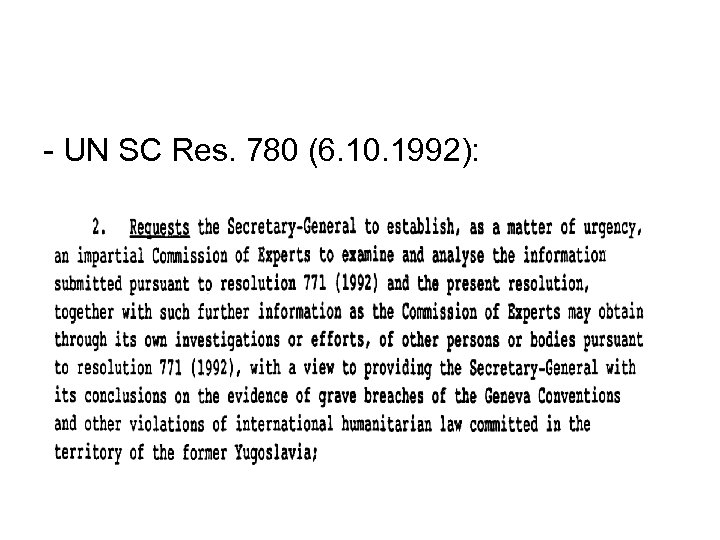

- UN SC Res. 780 (6. 10. 1992):

- UN SC Res. 780 (6. 10. 1992):

• The Commission created through Res. 780 was an int’l. fact-finding body as envisaged under Art. 90 of the Add. Prot. I (1977) to the 1949 Geneva Conventions. • The novelty is that, contrary to the understanding of the article in question, the commission was established without the explicit consent of the States involved. • The Commission could not obtain significant State support, materially or financially, but under the chairmanship of C. Bassiouni it managed to obtain financing from private resources. • The Commission succeed in gathering important evidence and it reported on its findings in 1994.

• The Commission created through Res. 780 was an int’l. fact-finding body as envisaged under Art. 90 of the Add. Prot. I (1977) to the 1949 Geneva Conventions. • The novelty is that, contrary to the understanding of the article in question, the commission was established without the explicit consent of the States involved. • The Commission could not obtain significant State support, materially or financially, but under the chairmanship of C. Bassiouni it managed to obtain financing from private resources. • The Commission succeed in gathering important evidence and it reported on its findings in 1994.

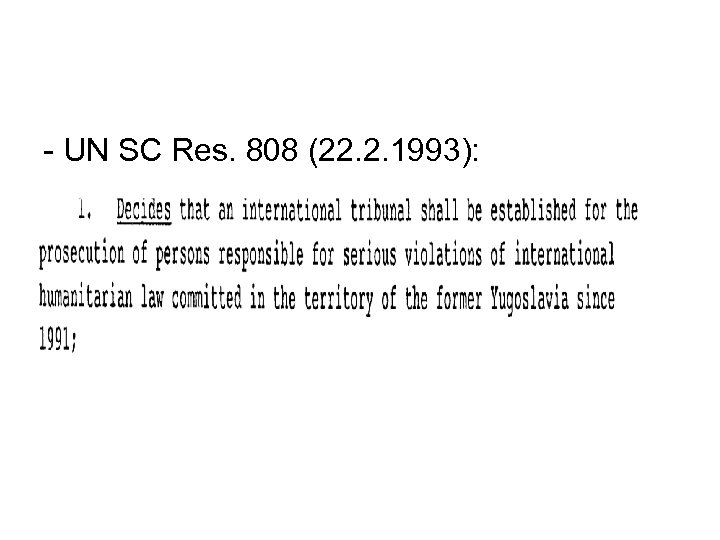

- UN SC Res. 808 (22. 2. 1993):

- UN SC Res. 808 (22. 2. 1993):

• In SC Res. 808, the UN SG was also instructed to examine whether the establishment of such tribunal would have a basis in law, and, if so, to formulate an appropriate statute. • The report prepared by the SG was in the affirmative and included the requested statute. • The SG recommended the creation of a tribunal by resolution (Report of the Secretary General Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 808 (1993), para. 20).

• In SC Res. 808, the UN SG was also instructed to examine whether the establishment of such tribunal would have a basis in law, and, if so, to formulate an appropriate statute. • The report prepared by the SG was in the affirmative and included the requested statute. • The SG recommended the creation of a tribunal by resolution (Report of the Secretary General Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 808 (1993), para. 20).

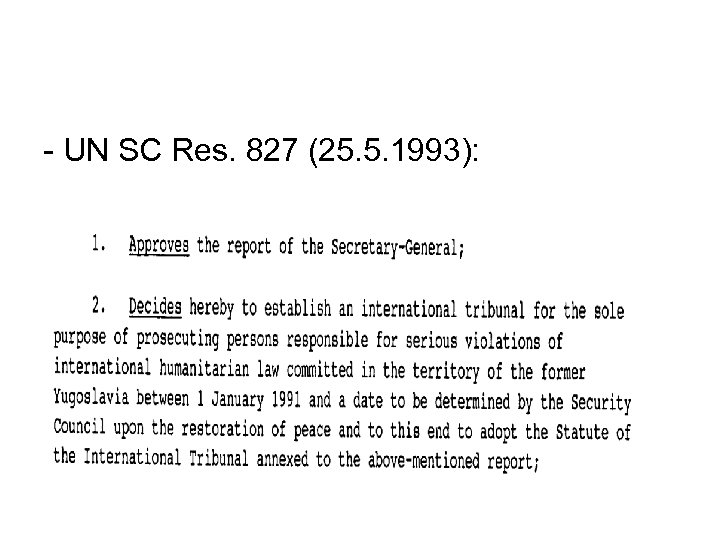

- UN SC Res. 827 (25. 5. 1993):

- UN SC Res. 827 (25. 5. 1993):

ICTR - Res. 955 (1994): “Acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations, 1. Decides hereby, having received the request of the Government of Rwanda (S/1994/1115), to establish an international tribunal for the sole purpose of prosecuting persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of Rwanda and Rwandan citizens responsible for genocide and other such violations committed in the territory of neighbouring States, between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 1994 and to this end to adopt the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda annexed hereto”. • Interestingly, Rwanda eventually voted against the Resolution because it did not have the control it meant over the Tribunal, and due to fact that the limited scope of temporal jurisdiction which did not include events occurring before January 1994 was unacceptable to the new gov’t (other factors: no death penalty included, unable to exclude crimes other than genocide from the Tribunal’s jurisdiction)

ICTR - Res. 955 (1994): “Acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations, 1. Decides hereby, having received the request of the Government of Rwanda (S/1994/1115), to establish an international tribunal for the sole purpose of prosecuting persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of Rwanda and Rwandan citizens responsible for genocide and other such violations committed in the territory of neighbouring States, between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 1994 and to this end to adopt the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda annexed hereto”. • Interestingly, Rwanda eventually voted against the Resolution because it did not have the control it meant over the Tribunal, and due to fact that the limited scope of temporal jurisdiction which did not include events occurring before January 1994 was unacceptable to the new gov’t (other factors: no death penalty included, unable to exclude crimes other than genocide from the Tribunal’s jurisdiction)

2. Was the establishment of the ICTY (and ICTR) lawful? • The first paragraph of the ICTY Statute, which is of introductory nature, states the following: “Having been established by the Security Council acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations, the International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991 (hereinafter referred to as “the International Tribunal”) shall function in accordance with the provisions of the present Statute. ” • As such, the ICTY is a subsidiary organ of the Security Council (UN Charter Art. 29). • The legal basis for the establishment of the court is Chapter VII of the UN Charter. The same holds true for the ICTR. That is why the explanations furnished below apply to both tribunals. • Chapter VII of the UN Charter is entitled «Action with Respect to Threats to the Peace, Breaches of the Peace, and Acts of Aggression» (Arts. 39 -51).

2. Was the establishment of the ICTY (and ICTR) lawful? • The first paragraph of the ICTY Statute, which is of introductory nature, states the following: “Having been established by the Security Council acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations, the International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991 (hereinafter referred to as “the International Tribunal”) shall function in accordance with the provisions of the present Statute. ” • As such, the ICTY is a subsidiary organ of the Security Council (UN Charter Art. 29). • The legal basis for the establishment of the court is Chapter VII of the UN Charter. The same holds true for the ICTR. That is why the explanations furnished below apply to both tribunals. • Chapter VII of the UN Charter is entitled «Action with Respect to Threats to the Peace, Breaches of the Peace, and Acts of Aggression» (Arts. 39 -51).

A. Relevant provisions of the UN Charter (Chapter VII) Article 39: The Security Council shall determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression and shall make recommendations, or decide what measures shall be taken in accordance with Articles 41 and 42, to maintain or restore international peace and security. Article 40: In order to prevent an aggravation of the situation, the Security Council may, before making the recommendations or deciding upon the measures provided for in Article 39, call upon the parties concerned to comply with such provisional measures as it deems necessary or desirable. Such provisional measures shall be without prejudice to the rights, claims, or position of the parties concerned. The Security Council shall duly take account of failure to comply with such provisional measures. Article 41: The Security Council may decide what measures not involving the use of armed force are to be employed to give effect to its decisions, and it may call upon the Members of the United Nations to apply such measures. These may include complete or partial interruption of economic relations and of rail, sea, air, postal, telegraphic, radio, and other means of communication, and the severance of diplomatic relations. Article 42: Should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in Article 41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may take such action by air, sea, or land forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security. Such action may include demonstrations, blockade, and other operations by air, sea, or land forces of Members of the United Nations. • The remaining articles of the Chapter regard the implementation of these measures. • Thus, there is no explicit provision in Chapter VII granting the SC the power to establish a judicial organ. In fact, the SC itself has no judicial (or legislative) power with regard to preventing or ending a conflict. For these reasons, some writers argue that the establishment of the ICTY was ultra vires.

A. Relevant provisions of the UN Charter (Chapter VII) Article 39: The Security Council shall determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression and shall make recommendations, or decide what measures shall be taken in accordance with Articles 41 and 42, to maintain or restore international peace and security. Article 40: In order to prevent an aggravation of the situation, the Security Council may, before making the recommendations or deciding upon the measures provided for in Article 39, call upon the parties concerned to comply with such provisional measures as it deems necessary or desirable. Such provisional measures shall be without prejudice to the rights, claims, or position of the parties concerned. The Security Council shall duly take account of failure to comply with such provisional measures. Article 41: The Security Council may decide what measures not involving the use of armed force are to be employed to give effect to its decisions, and it may call upon the Members of the United Nations to apply such measures. These may include complete or partial interruption of economic relations and of rail, sea, air, postal, telegraphic, radio, and other means of communication, and the severance of diplomatic relations. Article 42: Should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in Article 41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may take such action by air, sea, or land forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security. Such action may include demonstrations, blockade, and other operations by air, sea, or land forces of Members of the United Nations. • The remaining articles of the Chapter regard the implementation of these measures. • Thus, there is no explicit provision in Chapter VII granting the SC the power to establish a judicial organ. In fact, the SC itself has no judicial (or legislative) power with regard to preventing or ending a conflict. For these reasons, some writers argue that the establishment of the ICTY was ultra vires.

B. Why the establishment of the tribunals was lawful • • - - - The measures indicated in the above-mentioned articles are of an indicative nature, the articles do not provide for an exhaustive (numerus clausus) list. There is no doubt that the SC can resort to all measures that are adequate with a view to achieving world peace. The implied powers doctrine leads to the same conclusion. This refers to the degree of int’l. competence that is required to enable an int’l. organ to achieve its purposes. Even if certain competences are not explicitly stated in its constituent treaty, an organization may still enjoy those powers which are indispensable for the fulfilment of its duties and purposes. In other words, this doctrine suggests that organs of int’l. organisations may be deemed to possess all the powers necessary for the discharge of their powers and the fulfilment of the organisation’s goal, even when such powers are not clearly recognised by the constitutive instrument. The WHO case (Legality of the Use by a State of Nuclear Weapons in Armed Conflict, 1996) before the ICJ: “The necessities of international life may point to the need for organisations, in order to achieve their objectives, to possess subsidiary powers which are not expressly provided for in the basic instruments which govern their activities. It is generally accepted that international organisations can exercise such powers, known as implied powers”. Since the Yugoslavian crisis endangered world peace, the power to intervene judicially by prosecuting the perpetrators of certain violations in order to reestablish peace should be granted to the SC.

B. Why the establishment of the tribunals was lawful • • - - - The measures indicated in the above-mentioned articles are of an indicative nature, the articles do not provide for an exhaustive (numerus clausus) list. There is no doubt that the SC can resort to all measures that are adequate with a view to achieving world peace. The implied powers doctrine leads to the same conclusion. This refers to the degree of int’l. competence that is required to enable an int’l. organ to achieve its purposes. Even if certain competences are not explicitly stated in its constituent treaty, an organization may still enjoy those powers which are indispensable for the fulfilment of its duties and purposes. In other words, this doctrine suggests that organs of int’l. organisations may be deemed to possess all the powers necessary for the discharge of their powers and the fulfilment of the organisation’s goal, even when such powers are not clearly recognised by the constitutive instrument. The WHO case (Legality of the Use by a State of Nuclear Weapons in Armed Conflict, 1996) before the ICJ: “The necessities of international life may point to the need for organisations, in order to achieve their objectives, to possess subsidiary powers which are not expressly provided for in the basic instruments which govern their activities. It is generally accepted that international organisations can exercise such powers, known as implied powers”. Since the Yugoslavian crisis endangered world peace, the power to intervene judicially by prosecuting the perpetrators of certain violations in order to reestablish peace should be granted to the SC.

• Another argument is based on Arts. 24 -5 of the UN Charter. - Art. 24 (1): In order to ensure prompt and effective action by the United Nations, its Members confer on the Security Council primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security, and agree that in carrying out its duties under this responsibility the Security Council acts on their behalf. - Art. 25: The Members of the United Nations agree to accept and carry out the decisions of the Security Council in accordance with the present Charter. - Therefore, the UN SC is entitled to take decisions on behalf of the member States, such decisions are binding, and states may not fail to comply with it. - However, this argument does not really address the «lawfulness» of the decision.

• Another argument is based on Arts. 24 -5 of the UN Charter. - Art. 24 (1): In order to ensure prompt and effective action by the United Nations, its Members confer on the Security Council primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security, and agree that in carrying out its duties under this responsibility the Security Council acts on their behalf. - Art. 25: The Members of the United Nations agree to accept and carry out the decisions of the Security Council in accordance with the present Charter. - Therefore, the UN SC is entitled to take decisions on behalf of the member States, such decisions are binding, and states may not fail to comply with it. - However, this argument does not really address the «lawfulness» of the decision.

• • • - During the Gulf War, the SC, again acting under Chapter VII had set up the United Nations Compensation Commission in order to redress those victimized by the conflict. The Commission had the duty to decide on requests for compensation. As such, it had a judicial function too. No State ever objected to this power. Similarly, in the past, the UN GA created an administrative tribunal, and that action received approval by the ICJ in Effect of Awards of Compensation Made by the United Nations Administrative Tribunal (1954). If Chapter VII entitles the SC to authorize the use of military force, it has to be condeded that the Council is a fortiori allowed to authorize a measure which is not as coercive and exigent. (Criticism: you may not compare apples with pears!) Practical views: The UN, having failed to prevent the warfare and slaughters in Yugoslavia, could at least try those who were responsible for the atrocities and retrieve the credibility it depleted in the eyes of the global arena. Besides, concluding an international agreement in order to establish such a court, with regard to the preparation of its text, its ratification and coming into force, required a long process, and, in addition, there was no guarantee that all the relevant states would ratify it. However, the massacres committed by the Serbian had not come to an end a prompt, robust intervention was highly necessary. With this respect, establishment of a court with the interference of the Security Council via a resolution was deemed to be the only feasible solution.

• • • - During the Gulf War, the SC, again acting under Chapter VII had set up the United Nations Compensation Commission in order to redress those victimized by the conflict. The Commission had the duty to decide on requests for compensation. As such, it had a judicial function too. No State ever objected to this power. Similarly, in the past, the UN GA created an administrative tribunal, and that action received approval by the ICJ in Effect of Awards of Compensation Made by the United Nations Administrative Tribunal (1954). If Chapter VII entitles the SC to authorize the use of military force, it has to be condeded that the Council is a fortiori allowed to authorize a measure which is not as coercive and exigent. (Criticism: you may not compare apples with pears!) Practical views: The UN, having failed to prevent the warfare and slaughters in Yugoslavia, could at least try those who were responsible for the atrocities and retrieve the credibility it depleted in the eyes of the global arena. Besides, concluding an international agreement in order to establish such a court, with regard to the preparation of its text, its ratification and coming into force, required a long process, and, in addition, there was no guarantee that all the relevant states would ratify it. However, the massacres committed by the Serbian had not come to an end a prompt, robust intervention was highly necessary. With this respect, establishment of a court with the interference of the Security Council via a resolution was deemed to be the only feasible solution.

![C. ICTY’s own view • In the first case before the ICTY[1] the accused, C. ICTY’s own view • In the first case before the ICTY[1] the accused,](https://present5.com/presentation/4f543913ba651210989d216d5d70eb77/image-19.jpg) C. ICTY’s own view • In the first case before the ICTY[1] the accused, Duško Tadić, submitted a preliminary motion challenging the Tribunal’s jurisdiction by arguing, inter alia, that the Tribunal was established in violation of the UN Charter and should decline to exercise jurisdiction. • The Trial Chamber refused to deal with the substance of the argument because it thought that the powers of the SC had to be scrutinised in order to make a determination, and this was not a matter of jurisdiction open to the determination of the Tribunal. • However, the Appeals Chamber made a full review by arguing that any judicial body had the inherent or incidental jurisdiction to determine its own competence (Kompetenz-Kompetenz). The Appeals Chamber rejected the argument of the defence and determined that Art. 41, because of its open-ended character, was the appropriate legal basis for the establishment of the tribunal. - You may also read Cryer et al. at 126 -8 for the other findings on this issue. [1] Duško Tadić- Case no. IT-94 -1 -AR 72.

C. ICTY’s own view • In the first case before the ICTY[1] the accused, Duško Tadić, submitted a preliminary motion challenging the Tribunal’s jurisdiction by arguing, inter alia, that the Tribunal was established in violation of the UN Charter and should decline to exercise jurisdiction. • The Trial Chamber refused to deal with the substance of the argument because it thought that the powers of the SC had to be scrutinised in order to make a determination, and this was not a matter of jurisdiction open to the determination of the Tribunal. • However, the Appeals Chamber made a full review by arguing that any judicial body had the inherent or incidental jurisdiction to determine its own competence (Kompetenz-Kompetenz). The Appeals Chamber rejected the argument of the defence and determined that Art. 41, because of its open-ended character, was the appropriate legal basis for the establishment of the tribunal. - You may also read Cryer et al. at 126 -8 for the other findings on this issue. [1] Duško Tadić- Case no. IT-94 -1 -AR 72.

D. Summary • The understanding that the establishment of the Tribunal was legitimate and within the powers granted to the SC is the prevailing view in academic writings. • The Hague District Court dealing with Milošević’s claim that the Netherlands is hosting an illegal organization also affirmed the evaluations and conclusion of the ICTY with regard to its legitimacy[1]. • Even more important, state practice also seems to be in firm support of the establishment of both ad hoc tribunals. • In sum, it would be fair to say that the establishment of the ICTY and the ICTR were a lawful exercise of the powers attributed to the UN SC by the UN Charter. [1] Slobodan Milošević tegen de Staat der Nederlanden, Arrondissementsrechtbank’s-Gravenhage, Sector Civiel Recht – President, Vonnis in kort geding van 31 augustus 2001 (rolnummer KG 01/975).

D. Summary • The understanding that the establishment of the Tribunal was legitimate and within the powers granted to the SC is the prevailing view in academic writings. • The Hague District Court dealing with Milošević’s claim that the Netherlands is hosting an illegal organization also affirmed the evaluations and conclusion of the ICTY with regard to its legitimacy[1]. • Even more important, state practice also seems to be in firm support of the establishment of both ad hoc tribunals. • In sum, it would be fair to say that the establishment of the ICTY and the ICTR were a lawful exercise of the powers attributed to the UN SC by the UN Charter. [1] Slobodan Milošević tegen de Staat der Nederlanden, Arrondissementsrechtbank’s-Gravenhage, Sector Civiel Recht – President, Vonnis in kort geding van 31 augustus 2001 (rolnummer KG 01/975).

3. ICTY

3. ICTY

Excursus: Events leading to the establishment of the ICTY • Optional reading (in Turkish) concerning the political history and ethnic-cultural structure of, and civil war in, the Former Yugoslavia: You may read Önok, Tarihi Perspektifiyle Uluslararası Ceza Divanı, Ankara, 2003, s. 55 -63. • “Hatta mahkemede tanık ve sair delillerle ispatlanmış bir olayda, bir dede, torununun ciğerini yemeye zorlanmış; diğer bir vakada, bir esir, üç arkadaşının cinsel organlarını dişleriyle parçalamaya zorlanmış; diğer bir örnekte ise(, ) 14 yaşındaki bir çocuk, annesine tecavüz etmek zorunda bırakılmıştır” (aktaran Önok, s. 61, dn. 216). • You may read the Brdanin case, para. 498 -499, 503, 508509, 512 et seq.

Excursus: Events leading to the establishment of the ICTY • Optional reading (in Turkish) concerning the political history and ethnic-cultural structure of, and civil war in, the Former Yugoslavia: You may read Önok, Tarihi Perspektifiyle Uluslararası Ceza Divanı, Ankara, 2003, s. 55 -63. • “Hatta mahkemede tanık ve sair delillerle ispatlanmış bir olayda, bir dede, torununun ciğerini yemeye zorlanmış; diğer bir vakada, bir esir, üç arkadaşının cinsel organlarını dişleriyle parçalamaya zorlanmış; diğer bir örnekte ise(, ) 14 yaşındaki bir çocuk, annesine tecavüz etmek zorunda bırakılmıştır” (aktaran Önok, s. 61, dn. 216). • You may read the Brdanin case, para. 498 -499, 503, 508509, 512 et seq.

A. Basic Documents • Res. 808 (1993) envisaged the creation of the ICTY. However, it was Res. 827 (1993) that implemented such decision. • Indeed, Res. 827 meant the adoption of the Statute establishing the ICTY. As such, it determines the structure and competence of the tribunal. This is why it should be considered as the founding resolution. • The Statute adopted through Res. 827 (1993) defines the structure, competence, powers and procedure of the Court. It has been amended around 10 times. • The “Rules of Procedure and Evidence” which elaborate in detail the procedural rules governing the functioning of the Tribunal have been adopted on 11. 2. 1994, and have been amended tens of times.

A. Basic Documents • Res. 808 (1993) envisaged the creation of the ICTY. However, it was Res. 827 (1993) that implemented such decision. • Indeed, Res. 827 meant the adoption of the Statute establishing the ICTY. As such, it determines the structure and competence of the tribunal. This is why it should be considered as the founding resolution. • The Statute adopted through Res. 827 (1993) defines the structure, competence, powers and procedure of the Court. It has been amended around 10 times. • The “Rules of Procedure and Evidence” which elaborate in detail the procedural rules governing the functioning of the Tribunal have been adopted on 11. 2. 1994, and have been amended tens of times.

• • There also some other documents which are important with regard to the operation of the Court: The Headquarter Agreement of 1994 between the UN and the Netherlands, National legislations implementing the ICTY Statute and regulating cooperation with the court, Agreements on the enforcement of sentences, The Code of Professional Conduct for Defence Counsel Appearing before the International Tribunal Directive on Assignment of Defence Counsel, “Rules Governing the Detention of Persons Awaiting Trial or Appeal Before the Tribunal or Otherwise Detained on the Authority of the Tribunal”. In addition there are many other documents: Regulations Regarding Visits to and Communications with Detainees, House Rules for Detainees, Regulations for the Establishment of a Complaints Procedure for Detainees, Regulations for the Establishment of a Disciplinary Procedure for Detainees, and many “practice directions” regarding procedural or enforcement issues (for example, the Practice Direction on the Procedure for the Determination of Applications for Pardon, Commutation of Sentence and Early Release of Persons Convicted by the International Tribunal. ) As of March 2009, the Tribunal employed 1118 staff members from 82 different nationalities. That number dropped to 988 as of January 2011. As of September 2013, the ICTY employed 760 staff members representing 76 nationalities. The budget of the Tribunal is: 2002 -2003 = $ 223, 169, 800 // 2004 -2005 = $ 271, 854, 600 // 2006 -2007 = $ 276, 474, 100 // 2008 -2009 = $ 342, 332, 300 // 20102011: $ 301, 895, 900// 2012 -2013: $ 250, 814, 000.

• • There also some other documents which are important with regard to the operation of the Court: The Headquarter Agreement of 1994 between the UN and the Netherlands, National legislations implementing the ICTY Statute and regulating cooperation with the court, Agreements on the enforcement of sentences, The Code of Professional Conduct for Defence Counsel Appearing before the International Tribunal Directive on Assignment of Defence Counsel, “Rules Governing the Detention of Persons Awaiting Trial or Appeal Before the Tribunal or Otherwise Detained on the Authority of the Tribunal”. In addition there are many other documents: Regulations Regarding Visits to and Communications with Detainees, House Rules for Detainees, Regulations for the Establishment of a Complaints Procedure for Detainees, Regulations for the Establishment of a Disciplinary Procedure for Detainees, and many “practice directions” regarding procedural or enforcement issues (for example, the Practice Direction on the Procedure for the Determination of Applications for Pardon, Commutation of Sentence and Early Release of Persons Convicted by the International Tribunal. ) As of March 2009, the Tribunal employed 1118 staff members from 82 different nationalities. That number dropped to 988 as of January 2011. As of September 2013, the ICTY employed 760 staff members representing 76 nationalities. The budget of the Tribunal is: 2002 -2003 = $ 223, 169, 800 // 2004 -2005 = $ 271, 854, 600 // 2006 -2007 = $ 276, 474, 100 // 2008 -2009 = $ 342, 332, 300 // 20102011: $ 301, 895, 900// 2012 -2013: $ 250, 814, 000.

B. Legal Status of the ICTY • It is an ad hoc tribunal; It is another instance of ex post facto justice. • Contrary to the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals, it is not a military court. • It is a subsidiary organ of the UN SC (Art. 29 UN Charter), as such, the Statute of the ICTY is binding upon every member of the UN (Art. 25 UN Charter) • However, as a judicial organ, the ICTY is independent from the SC (ICTY Trial Chamber, 18. 7. 1997, Blaškić case). • Because it has been established through a resolution of the UN SC, all UN member states are under certain obligations with regard to the ICTY. In that sense, the tribunal has some supranational powers. • The Statute of the ICTY (and of the ICTR) is equated by the Tribunal itself to an int’l treaty. Academic writings agree with this view.

B. Legal Status of the ICTY • It is an ad hoc tribunal; It is another instance of ex post facto justice. • Contrary to the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals, it is not a military court. • It is a subsidiary organ of the UN SC (Art. 29 UN Charter), as such, the Statute of the ICTY is binding upon every member of the UN (Art. 25 UN Charter) • However, as a judicial organ, the ICTY is independent from the SC (ICTY Trial Chamber, 18. 7. 1997, Blaškić case). • Because it has been established through a resolution of the UN SC, all UN member states are under certain obligations with regard to the ICTY. In that sense, the tribunal has some supranational powers. • The Statute of the ICTY (and of the ICTR) is equated by the Tribunal itself to an int’l treaty. Academic writings agree with this view.

C. Structure of the ICTY • According to Art. 11 of the Statute, the ICTY consists of the following organs: (a) the Chambers, comprising three Trial Chambers and an Appeals Chamber; (b) the Office of the Prosecutor; and (c) a Registry, servicing both the Chambers and the Prosecutor. • A maximum at any one time of three permanent judges and six ad litem judges shall be members of each Trial Chamber. (Art. 12 (2)). Ad litem judges are specially appointed to sit on a particular case or cases. • Seven of the permanent judges shall be members of the Appeals Chamber. The Appeals Chamber shall, for each appeal, be composed of five of its members. (Art. 12 (3)). • The International Tribunal shall have its seat at The Hague (Art. 31 ICTY Statute)

C. Structure of the ICTY • According to Art. 11 of the Statute, the ICTY consists of the following organs: (a) the Chambers, comprising three Trial Chambers and an Appeals Chamber; (b) the Office of the Prosecutor; and (c) a Registry, servicing both the Chambers and the Prosecutor. • A maximum at any one time of three permanent judges and six ad litem judges shall be members of each Trial Chamber. (Art. 12 (2)). Ad litem judges are specially appointed to sit on a particular case or cases. • Seven of the permanent judges shall be members of the Appeals Chamber. The Appeals Chamber shall, for each appeal, be composed of five of its members. (Art. 12 (3)). • The International Tribunal shall have its seat at The Hague (Art. 31 ICTY Statute)

D. Qualifications and election of judges • Art. 13: The permanent and ad litem judges shall be persons of high moral character, impartiality and integrity who possess the qualifications required in their respective countries for appointment to the highest judicial offices. In the overall composition of the Chambers and sections of the Trial Chambers, due account shall be taken of the experience of the judges in criminal law, international law, including international humanitarian law and human rights law.

D. Qualifications and election of judges • Art. 13: The permanent and ad litem judges shall be persons of high moral character, impartiality and integrity who possess the qualifications required in their respective countries for appointment to the highest judicial offices. In the overall composition of the Chambers and sections of the Trial Chambers, due account shall be taken of the experience of the judges in criminal law, international law, including international humanitarian law and human rights law.

• • Art. 13 bis (Election of permanent judges): Fourteen of the permanent judges shall be elected by the General Assembly from a list submitted by the Security Council. Each State may nominate up to two candidates. From the nominations received the Security Council shall establish a list of not less than twenty-eight and not more than forty-two candidates, taking due account of the adequate representation of the principal legal systems of the world The candidates who receive an absolute majority of the votes of the States Members of the United Nations and of the non-member States maintaining permanent observer missions at United Nations Headquarters, shall be declared elected. The permanent judges shall be elected for a term of four years. The terms and conditions of service shall be those of the judges of the International Court of Justice. They shall be eligible for re-election. Art. 13 ter (Election and appointment of ad litem judges): The ad litem judges of the International Tribunal shall be elected by the General Assembly from a list submitted by the Security Council. Each State may nominate up to four candidates. From the nominations received the Security Council shall establish a list of not less than fifty-four candidates, taking due account of the adequate representation of the principal legal systems of the world and bearing in mind the importance of equitable geographical distribution. The candidates who receive an absolute majority of the votes of the States Members of the United Nations and of the non-member States maintaining permanent observer missions at United Nations Headquarters shall be declared elected. The ad litem judges shall be elected for a term of four years. They shall be eligible for re-election.

• • Art. 13 bis (Election of permanent judges): Fourteen of the permanent judges shall be elected by the General Assembly from a list submitted by the Security Council. Each State may nominate up to two candidates. From the nominations received the Security Council shall establish a list of not less than twenty-eight and not more than forty-two candidates, taking due account of the adequate representation of the principal legal systems of the world The candidates who receive an absolute majority of the votes of the States Members of the United Nations and of the non-member States maintaining permanent observer missions at United Nations Headquarters, shall be declared elected. The permanent judges shall be elected for a term of four years. The terms and conditions of service shall be those of the judges of the International Court of Justice. They shall be eligible for re-election. Art. 13 ter (Election and appointment of ad litem judges): The ad litem judges of the International Tribunal shall be elected by the General Assembly from a list submitted by the Security Council. Each State may nominate up to four candidates. From the nominations received the Security Council shall establish a list of not less than fifty-four candidates, taking due account of the adequate representation of the principal legal systems of the world and bearing in mind the importance of equitable geographical distribution. The candidates who receive an absolute majority of the votes of the States Members of the United Nations and of the non-member States maintaining permanent observer missions at United Nations Headquarters shall be declared elected. The ad litem judges shall be elected for a term of four years. They shall be eligible for re-election.

E. The Office of the Prosecutor • The Office of the Prosecutor is the organ responsible with investigating allegations, issuing indictments (which have to be confirmed by a judge), and bring matters to trial. • Art. 16 (4): The Prosecutor shall be appointed by the Security Council on nomination by the Secretary-General. He or she shall be of high moral character and possess the highest level of competence and experience in the conduct of investigations and prosecutions of criminal cases. The Prosecutor shall serve for a four -year term and be eligible for reappointment. • Art. 16 (2): The Prosecutor shall act independently as a separate organ of the International Tribunal. He or she shall not seek or receive instructions from any Government or from any other source. • Art. 16 (3): The Office of the Prosecutor shall be composed of a Prosecutor and such other qualified staff as may be required. • UN SC Res. 1786 (2007): On 28. 11. 2007, Serge Brammertz has been appointed for a four-year term to serve as the prosecutor of the Tribunal as of 1. 1. 2008. His mandate has been extended, and he is still serving.

E. The Office of the Prosecutor • The Office of the Prosecutor is the organ responsible with investigating allegations, issuing indictments (which have to be confirmed by a judge), and bring matters to trial. • Art. 16 (4): The Prosecutor shall be appointed by the Security Council on nomination by the Secretary-General. He or she shall be of high moral character and possess the highest level of competence and experience in the conduct of investigations and prosecutions of criminal cases. The Prosecutor shall serve for a four -year term and be eligible for reappointment. • Art. 16 (2): The Prosecutor shall act independently as a separate organ of the International Tribunal. He or she shall not seek or receive instructions from any Government or from any other source. • Art. 16 (3): The Office of the Prosecutor shall be composed of a Prosecutor and such other qualified staff as may be required. • UN SC Res. 1786 (2007): On 28. 11. 2007, Serge Brammertz has been appointed for a four-year term to serve as the prosecutor of the Tribunal as of 1. 1. 2008. His mandate has been extended, and he is still serving.

F. The Registry • Art. 17: The Registry shall be responsible for the administration and servicing of the International Tribunal. • The Registry shall consist of a Registrar and such other staff as may be required. • The Registrar shall be appointed by the Secretary. General after consultation with the President of the International Tribunal. He or she shall serve for a fouryear term and be eligible for reappointment. • The staff of the Registry shall be appointed by the Secretary-General on the recommendation of the Registrar. • Mr. John Hocking, from Australia, has been Registrar since 15 May 2009.

F. The Registry • Art. 17: The Registry shall be responsible for the administration and servicing of the International Tribunal. • The Registry shall consist of a Registrar and such other staff as may be required. • The Registrar shall be appointed by the Secretary. General after consultation with the President of the International Tribunal. He or she shall serve for a fouryear term and be eligible for reappointment. • The staff of the Registry shall be appointed by the Secretary-General on the recommendation of the Registrar. • Mr. John Hocking, from Australia, has been Registrar since 15 May 2009.

G. Jurisdiction of the ICTY • • General competence (Art. 1): The International Tribunal shall have the power to prosecute persons responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 in accordance with the provisions of the present Statute. Temporal jurisdiction (Art. 8): The temporal jurisdiction of the International Tribunal shall extend to a period beginning on 1 January 1991. This is to mean that only acts committed after that date may be tried by the ICTY. There is no clarity as to the final date after which the Tribunal no longer possesses temporal jurisdiction. It may be said that the temporal jurisdiction can comprise all events occurring until the Tribunal continues its activity, in other words, until the UN SC terminates the existence of the Court. That is how the later conflicts in Kosovo and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia fell within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal. However, in accordance with the Tribunal’s “completion strategy”, the last indictments were issued at the end of 2004. The UN SC wanted a completion strategy to be implemented by the end of 2010. Thus, it had requested both the ICTY and ICTR to complete all investigations by the end of 2004, to complete all trial activities at first instance by the end of 2008 and to complete all work in 2010. (Res. 1503 (2003) and Res. 1534 (2004)). However, the ICTY has stated in its Completion Strategy Report (S/2009/252) that the Tribunal will not be in a position to complete all its work in 2010. Similarly, the Completion Strategy Report (S/2009/247) by the ICTR also states that the Tribunal will not be in a position to complete all its work in 2010. Thus, the Court will at least continue its activity until all current cases are finalized. That will be, it seems, until the end of 2016.

G. Jurisdiction of the ICTY • • General competence (Art. 1): The International Tribunal shall have the power to prosecute persons responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 in accordance with the provisions of the present Statute. Temporal jurisdiction (Art. 8): The temporal jurisdiction of the International Tribunal shall extend to a period beginning on 1 January 1991. This is to mean that only acts committed after that date may be tried by the ICTY. There is no clarity as to the final date after which the Tribunal no longer possesses temporal jurisdiction. It may be said that the temporal jurisdiction can comprise all events occurring until the Tribunal continues its activity, in other words, until the UN SC terminates the existence of the Court. That is how the later conflicts in Kosovo and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia fell within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal. However, in accordance with the Tribunal’s “completion strategy”, the last indictments were issued at the end of 2004. The UN SC wanted a completion strategy to be implemented by the end of 2010. Thus, it had requested both the ICTY and ICTR to complete all investigations by the end of 2004, to complete all trial activities at first instance by the end of 2008 and to complete all work in 2010. (Res. 1503 (2003) and Res. 1534 (2004)). However, the ICTY has stated in its Completion Strategy Report (S/2009/252) that the Tribunal will not be in a position to complete all its work in 2010. Similarly, the Completion Strategy Report (S/2009/247) by the ICTR also states that the Tribunal will not be in a position to complete all its work in 2010. Thus, the Court will at least continue its activity until all current cases are finalized. That will be, it seems, until the end of 2016.

• Territorial jurisdiction (Art. 8): The territorial jurisdiction of the International Tribunal shall extend to the territory of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, including its land surface, airspace and territorial waters • Personal jurisdiction (Art. 6): The International Tribunal shall have jurisdiction over natural persons pursuant to the provisions of the present Statute. • Subject-matter jurisdiction (madde bakımından yetki - Arts. 25): • This refers to the categories of crimes over which the ICTY may exercise jurisdiction. The Statute only embodies those acts which are clearly criminalized under positive int’l law, in other words, acts that are considered crimes under int’l treaties and int’l customary law. The idea behind such choice is to prevent objections based on the principle of legality.

• Territorial jurisdiction (Art. 8): The territorial jurisdiction of the International Tribunal shall extend to the territory of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, including its land surface, airspace and territorial waters • Personal jurisdiction (Art. 6): The International Tribunal shall have jurisdiction over natural persons pursuant to the provisions of the present Statute. • Subject-matter jurisdiction (madde bakımından yetki - Arts. 25): • This refers to the categories of crimes over which the ICTY may exercise jurisdiction. The Statute only embodies those acts which are clearly criminalized under positive int’l law, in other words, acts that are considered crimes under int’l treaties and int’l customary law. The idea behind such choice is to prevent objections based on the principle of legality.

Art. 2 (Grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949) • The International Tribunal shall have the power to prosecute persons committing or ordering to be committed grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, namely the following acts against persons or property protected under the provisions of the relevant Geneva Convention: (a) wilful killing; (b) torture or inhuman treatment, including biological experiments; (c) willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health; (d) extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly; (e) compelling a prisoner of war or a civilian to serve in the forces of a hostile power; (f) willfully depriving a prisoner of war or a civilian of the rights of fair and regular trial; (g) unlawful deportation or transfer or unlawful confinement of a civilian; (h) taking civilians as hostages. • • The 1949 Conventions only apply to international armed conflicts. • The Appeals Chamber in Tadic has declared that with regard to Bosnia, the armed conflict occurring after May 19, 1992 constitutes an int’l. armed conflict. After the declaration of independence by Slovenia on June 25, 1991 the conflict has assumed an int’l. character, thus the 1949 Conventions became applicable.

Art. 2 (Grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949) • The International Tribunal shall have the power to prosecute persons committing or ordering to be committed grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, namely the following acts against persons or property protected under the provisions of the relevant Geneva Convention: (a) wilful killing; (b) torture or inhuman treatment, including biological experiments; (c) willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health; (d) extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly; (e) compelling a prisoner of war or a civilian to serve in the forces of a hostile power; (f) willfully depriving a prisoner of war or a civilian of the rights of fair and regular trial; (g) unlawful deportation or transfer or unlawful confinement of a civilian; (h) taking civilians as hostages. • • The 1949 Conventions only apply to international armed conflicts. • The Appeals Chamber in Tadic has declared that with regard to Bosnia, the armed conflict occurring after May 19, 1992 constitutes an int’l. armed conflict. After the declaration of independence by Slovenia on June 25, 1991 the conflict has assumed an int’l. character, thus the 1949 Conventions became applicable.

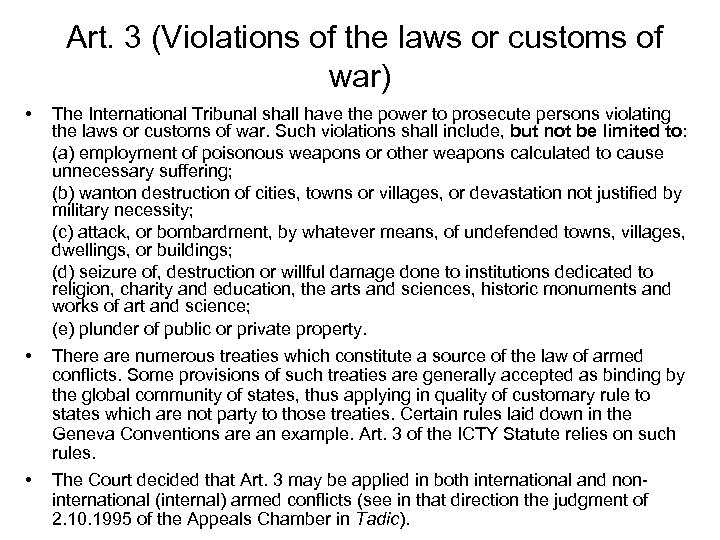

Art. 3 (Violations of the laws or customs of war) • The International Tribunal shall have the power to prosecute persons violating the laws or customs of war. Such violations shall include, but not be limited to: (a) employment of poisonous weapons or other weapons calculated to cause unnecessary suffering; (b) wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity; (c) attack, or bombardment, by whatever means, of undefended towns, villages, dwellings, or buildings; (d) seizure of, destruction or willful damage done to institutions dedicated to religion, charity and education, the arts and sciences, historic monuments and works of art and science; (e) plunder of public or private property. • There are numerous treaties which constitute a source of the law of armed conflicts. Some provisions of such treaties are generally accepted as binding by the global community of states, thus applying in quality of customary rule to states which are not party to those treaties. Certain rules laid down in the Geneva Conventions are an example. Art. 3 of the ICTY Statute relies on such rules. • The Court decided that Art. 3 may be applied in both international and noninternational (internal) armed conflicts (see in that direction the judgment of 2. 10. 1995 of the Appeals Chamber in Tadic).

Art. 3 (Violations of the laws or customs of war) • The International Tribunal shall have the power to prosecute persons violating the laws or customs of war. Such violations shall include, but not be limited to: (a) employment of poisonous weapons or other weapons calculated to cause unnecessary suffering; (b) wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity; (c) attack, or bombardment, by whatever means, of undefended towns, villages, dwellings, or buildings; (d) seizure of, destruction or willful damage done to institutions dedicated to religion, charity and education, the arts and sciences, historic monuments and works of art and science; (e) plunder of public or private property. • There are numerous treaties which constitute a source of the law of armed conflicts. Some provisions of such treaties are generally accepted as binding by the global community of states, thus applying in quality of customary rule to states which are not party to those treaties. Certain rules laid down in the Geneva Conventions are an example. Art. 3 of the ICTY Statute relies on such rules. • The Court decided that Art. 3 may be applied in both international and noninternational (internal) armed conflicts (see in that direction the judgment of 2. 10. 1995 of the Appeals Chamber in Tadic).

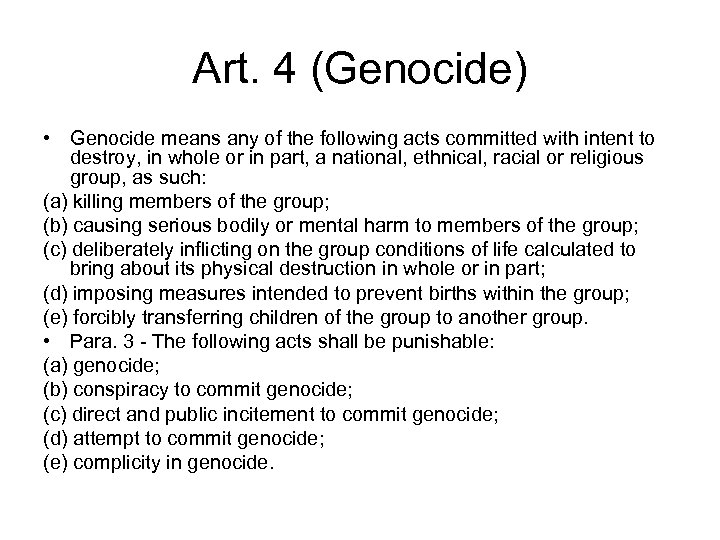

Art. 4 (Genocide) • Genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: (a) killing members of the group; (b) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. • Para. 3 - The following acts shall be punishable: (a) genocide; (b) conspiracy to commit genocide; (c) direct and public incitement to commit genocide; (d) attempt to commit genocide; (e) complicity in genocide.

Art. 4 (Genocide) • Genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: (a) killing members of the group; (b) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. • Para. 3 - The following acts shall be punishable: (a) genocide; (b) conspiracy to commit genocide; (c) direct and public incitement to commit genocide; (d) attempt to commit genocide; (e) complicity in genocide.

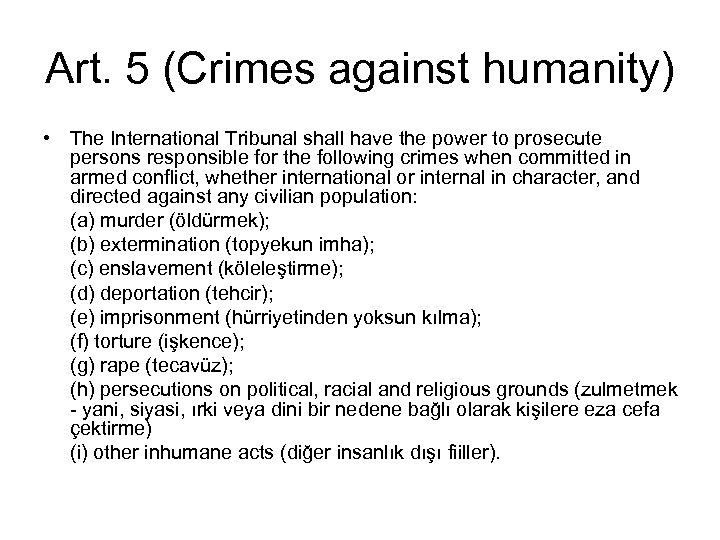

Art. 5 (Crimes against humanity) • The International Tribunal shall have the power to prosecute persons responsible for the following crimes when committed in armed conflict, whether international or internal in character, and directed against any civilian population: (a) murder (öldürmek); (b) extermination (topyekun imha); (c) enslavement (köleleştirme); (d) deportation (tehcir); (e) imprisonment (hürriyetinden yoksun kılma); (f) torture (işkence); (g) rape (tecavüz); (h) persecutions on political, racial and religious grounds (zulmetmek - yani, siyasi, ırki veya dini bir nedene bağlı olarak kişilere eza cefa çektirme) (i) other inhumane acts (diğer insanlık dışı fiiller).

Art. 5 (Crimes against humanity) • The International Tribunal shall have the power to prosecute persons responsible for the following crimes when committed in armed conflict, whether international or internal in character, and directed against any civilian population: (a) murder (öldürmek); (b) extermination (topyekun imha); (c) enslavement (köleleştirme); (d) deportation (tehcir); (e) imprisonment (hürriyetinden yoksun kılma); (f) torture (işkence); (g) rape (tecavüz); (h) persecutions on political, racial and religious grounds (zulmetmek - yani, siyasi, ırki veya dini bir nedene bağlı olarak kişilere eza cefa çektirme) (i) other inhumane acts (diğer insanlık dışı fiiller).

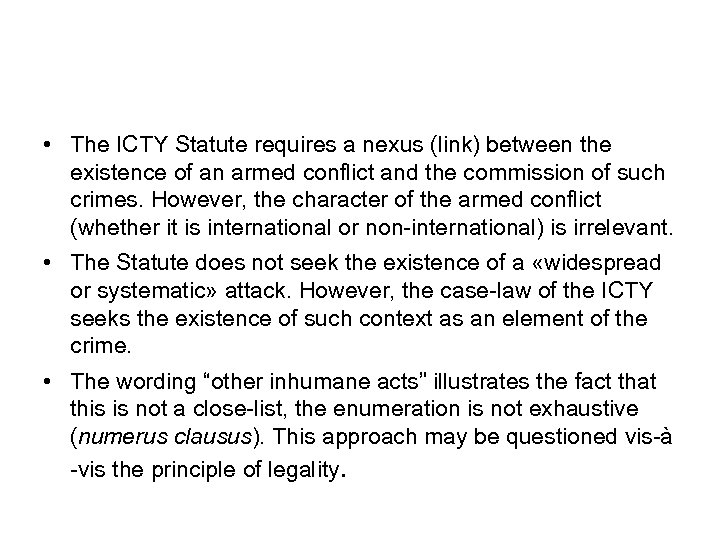

• The ICTY Statute requires a nexus (link) between the existence of an armed conflict and the commission of such crimes. However, the character of the armed conflict (whether it is international or non-international) is irrelevant. • The Statute does not seek the existence of a «widespread or systematic» attack. However, the case-law of the ICTY seeks the existence of such context as an element of the crime. • The wording “other inhumane acts” illustrates the fact that this is not a close-list, the enumeration is not exhaustive (numerus clausus). This approach may be questioned vis-à -vis the principle of legality.

• The ICTY Statute requires a nexus (link) between the existence of an armed conflict and the commission of such crimes. However, the character of the armed conflict (whether it is international or non-international) is irrelevant. • The Statute does not seek the existence of a «widespread or systematic» attack. However, the case-law of the ICTY seeks the existence of such context as an element of the crime. • The wording “other inhumane acts” illustrates the fact that this is not a close-list, the enumeration is not exhaustive (numerus clausus). This approach may be questioned vis-à -vis the principle of legality.

No aggression? • For reasons of political expedience the crime of aggression has not been incorporated into the Statute. • This is because it was impossible to accept on the political level as a legitimate counterpart during peace negotiations those persons who had started and leadered the war on the one hand, and try to prosecute them as the perpetrators of the “supreme crime”of aggression, on the other.

No aggression? • For reasons of political expedience the crime of aggression has not been incorporated into the Statute. • This is because it was impossible to accept on the political level as a legitimate counterpart during peace negotiations those persons who had started and leadered the war on the one hand, and try to prosecute them as the perpetrators of the “supreme crime”of aggression, on the other.

H. Relationship with national criminal jurisdiction (Art. 9) • • “ 1. The International Tribunal and national courts shall have concurrent jurisdiction to prosecute persons for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1 January 1991. 2. The International Tribunal shall have primacy over national courts. At any stage of the procedure, the International Tribunal may formally request national courts to defer to the competence of the International Tribunal in accordance with the present Statute and the Rules of Procedure and Evidence of the International Tribunal”. On the one hand, the ICTY and national criminal courts have concurrent jurisdiction, they are both entitled to try the crimes enumerated in the Statute. So, the crimes described above may be committed for trial before national Bosnian, Serbian, Croatian, Slovenian courts too. However, para. 2 of Art. 9 grants primacy to the international tribunal. Although the provision speaks of “request”ing national courts to defer the case, national courts are in fact obliged to comply with such request. This is confirmed by the prioritary position of the Tribunal as stressed out by the UN SG’s report accepted through Res. 808, and by Articles 9 and Art. 29 (1): “States shall co-operate with the International Tribunal in the investigation and prosecution of persons accused of committing serious violations of international humanitarian law. “ Rule 9 RPE explains when deferral is justified.

H. Relationship with national criminal jurisdiction (Art. 9) • • “ 1. The International Tribunal and national courts shall have concurrent jurisdiction to prosecute persons for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1 January 1991. 2. The International Tribunal shall have primacy over national courts. At any stage of the procedure, the International Tribunal may formally request national courts to defer to the competence of the International Tribunal in accordance with the present Statute and the Rules of Procedure and Evidence of the International Tribunal”. On the one hand, the ICTY and national criminal courts have concurrent jurisdiction, they are both entitled to try the crimes enumerated in the Statute. So, the crimes described above may be committed for trial before national Bosnian, Serbian, Croatian, Slovenian courts too. However, para. 2 of Art. 9 grants primacy to the international tribunal. Although the provision speaks of “request”ing national courts to defer the case, national courts are in fact obliged to comply with such request. This is confirmed by the prioritary position of the Tribunal as stressed out by the UN SG’s report accepted through Res. 808, and by Articles 9 and Art. 29 (1): “States shall co-operate with the International Tribunal in the investigation and prosecution of persons accused of committing serious violations of international humanitarian law. “ Rule 9 RPE explains when deferral is justified.

• • Thus, the relationship with national criminal jurisdiction is configured differently compared with other int’l. criminal tribunals. Indeed, the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals had replaced national courts. On the other hand, the ICC, as we shall see, is only complementary to national jurisdiction (Arts. 1 and 17 of the Rome Statute). The ICTY and ICTR differ from both systems. They do not replace national courts, but unlike the ICC, they do not only complete national jurisdiction neither. They work together with national courts, but have primacy over them. An important rule in this regard is incorporated in the Rules of Procedure and Evidence, Rule 11 bis: In certain cases, by considering the gravity of the crimes charged and the level of responsibility of the accused, certain cases before the ICTY may be referred to national courts. This rule alleviates the workload of the Tribunal and allows the defendants to be tried witihn a reasonable time. By referring certain cases of minor importance to national courts, it is made sure that the ICTY only has to deal with those criminals bearing the major responsibility. This rule will also help achieve the Completion Strategy.

• • Thus, the relationship with national criminal jurisdiction is configured differently compared with other int’l. criminal tribunals. Indeed, the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals had replaced national courts. On the other hand, the ICC, as we shall see, is only complementary to national jurisdiction (Arts. 1 and 17 of the Rome Statute). The ICTY and ICTR differ from both systems. They do not replace national courts, but unlike the ICC, they do not only complete national jurisdiction neither. They work together with national courts, but have primacy over them. An important rule in this regard is incorporated in the Rules of Procedure and Evidence, Rule 11 bis: In certain cases, by considering the gravity of the crimes charged and the level of responsibility of the accused, certain cases before the ICTY may be referred to national courts. This rule alleviates the workload of the Tribunal and allows the defendants to be tried witihn a reasonable time. By referring certain cases of minor importance to national courts, it is made sure that the ICTY only has to deal with those criminals bearing the major responsibility. This rule will also help achieve the Completion Strategy.

• Non bis in idem principle: “ 1. No person shall be tried before a national court for acts constituting serious violations of international humanitarian law under the present Statute, for which he or she has already been tried by the International Tribunal. 2. A person who has been tried by a national court for acts constituting serious violations of international humanitarian law may be subsequently tried by the International Tribunal only if: (a) the act for which he or she was tried was characterized as an ordinary crime; or (b) the national court proceedings were not impartial or independent, were designed to shield the accused from international criminal responsibility, or the case was not diligently prosecuted. 3. In considering the penalty to be imposed on a person convicted of a crime under the present Statute, the International Tribunal shall take into account the extent to which any penalty imposed by a national court on the same person for the same act has already been served. ”

• Non bis in idem principle: “ 1. No person shall be tried before a national court for acts constituting serious violations of international humanitarian law under the present Statute, for which he or she has already been tried by the International Tribunal. 2. A person who has been tried by a national court for acts constituting serious violations of international humanitarian law may be subsequently tried by the International Tribunal only if: (a) the act for which he or she was tried was characterized as an ordinary crime; or (b) the national court proceedings were not impartial or independent, were designed to shield the accused from international criminal responsibility, or the case was not diligently prosecuted. 3. In considering the penalty to be imposed on a person convicted of a crime under the present Statute, the International Tribunal shall take into account the extent to which any penalty imposed by a national court on the same person for the same act has already been served. ”

I. General Principles of Criminal Law • - - Art. 7, on individual criminal responsibility, lays down the following rules: A person who planned, instigated, ordered, committed or otherwise aided and abetted in the planning, preparation or execution of a crime referred to in articles 2 to 5 of the present Statute, shall be individually responsible for the crime (para. 1). The official position of any accused person, whether as Head of State or Government or as a responsible Government official, shall not relieve such person of criminal responsibility nor mitigate punishment (para. 2). The fact that any of the acts referred to in articles 2 to 5 of the present Statute was committed by a subordinate does not relieve his superior of criminal responsibility if he knew or had reason to know that the subordinate was about to commit such acts or had done so and the superior failed to take the necessary and reasonable measures to prevent such acts or to punish the perpetrators thereof. (para. 3) (‘superior/command responsibility’). (This rule on ‘superior responsibility’ is similar to that found in Art. 28 of the ICC Statute. The difference is that the ICC Statute also makes mention to a “person effectively acting as a military commander” (de facto commander). So, the ICC Statute explicitly provides for the responsibility of persons such as gang leaders. However, the case-law of the ICTY has also included de facto superiors/commanders within the ambit of this paragraph. )

I. General Principles of Criminal Law • - - Art. 7, on individual criminal responsibility, lays down the following rules: A person who planned, instigated, ordered, committed or otherwise aided and abetted in the planning, preparation or execution of a crime referred to in articles 2 to 5 of the present Statute, shall be individually responsible for the crime (para. 1). The official position of any accused person, whether as Head of State or Government or as a responsible Government official, shall not relieve such person of criminal responsibility nor mitigate punishment (para. 2). The fact that any of the acts referred to in articles 2 to 5 of the present Statute was committed by a subordinate does not relieve his superior of criminal responsibility if he knew or had reason to know that the subordinate was about to commit such acts or had done so and the superior failed to take the necessary and reasonable measures to prevent such acts or to punish the perpetrators thereof. (para. 3) (‘superior/command responsibility’). (This rule on ‘superior responsibility’ is similar to that found in Art. 28 of the ICC Statute. The difference is that the ICC Statute also makes mention to a “person effectively acting as a military commander” (de facto commander). So, the ICC Statute explicitly provides for the responsibility of persons such as gang leaders. However, the case-law of the ICTY has also included de facto superiors/commanders within the ambit of this paragraph. )

- The fact that an accused person acted pursuant to an order of a Government or of a superior shall not relieve him of criminal responsibility, but may be considered in mitigation of punishment if the International Tribunal determines that justice so requires (para. 4). This is similar to Art. 33 of the ICC Statute. However, in the Rome Statute the superior order defence neither constitutes a justification nor a mitigatory circumstance. However, as we shall see later on, under certain conditions, the person acting under superior orders may be relieved altogether from criminal responsibility under the Rome Statute.

- The fact that an accused person acted pursuant to an order of a Government or of a superior shall not relieve him of criminal responsibility, but may be considered in mitigation of punishment if the International Tribunal determines that justice so requires (para. 4). This is similar to Art. 33 of the ICC Statute. However, in the Rome Statute the superior order defence neither constitutes a justification nor a mitigatory circumstance. However, as we shall see later on, under certain conditions, the person acting under superior orders may be relieved altogether from criminal responsibility under the Rome Statute.

• There is no provision regarding the punishment of attempt. - In my opinion, the principle of legality prevents the punishment of attempt since there is no explicit rule in the Statute regarding its criminalization. However, many writers argue that attempt can be punished based on customary law. - In practice, the prosecutor has punished attempted crimes by considering them under other categories of crimes. For example, the indictments have qualified attempted murder as inhuman treatment. • Similarly, there are no provisions regarding culpability and circumstances excluding culpability, such as mental disorder, involuntary intoxication, force majeure. However, such institutions are part of general principles of law recognized by all legal systems, and will thus apply in such quality. The principle of legality is not a bar in this case since the application of these rules will be in favour of the suspect.

• There is no provision regarding the punishment of attempt. - In my opinion, the principle of legality prevents the punishment of attempt since there is no explicit rule in the Statute regarding its criminalization. However, many writers argue that attempt can be punished based on customary law. - In practice, the prosecutor has punished attempted crimes by considering them under other categories of crimes. For example, the indictments have qualified attempted murder as inhuman treatment. • Similarly, there are no provisions regarding culpability and circumstances excluding culpability, such as mental disorder, involuntary intoxication, force majeure. However, such institutions are part of general principles of law recognized by all legal systems, and will thus apply in such quality. The principle of legality is not a bar in this case since the application of these rules will be in favour of the suspect.

J. Investigation, Prosecution, and Enforcement of Sentences • Art. 18 (Investigation and preparation of indictment): 1. The Prosecutor shall initiate investigations ex-officio or on the basis of information obtained from any source, particularly from Governments, United Nations organs, intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations. The Prosecutor shall assess the information received or obtained and decide whethere is sufficient basis to proceed. 2. The Prosecutor shall have the power to question suspects, victims and witnesses, to collect evidence and to conduct on-site investigations. In carrying out these tasks, the Prosecutor may, as appropriate, seek the assistance of the State authorities concerned. 3. If questioned, the suspect shall be entitled to be assisted by counsel of his own choice, including the right to have legal assistance assigned to him without payment by him in any such case if he does not have sufficient means to pay for it, as well as to necessary translation into and from a language he speaks and understands. 4. Upon a determination that a prima facie case exists, the Prosecutor shall prepare an indictment containing a concise statement of the facts and the crime or crimes with which the accused is charged under the Statute. The indictment shall be transmitted to a judge of the Trial Chamber.

J. Investigation, Prosecution, and Enforcement of Sentences • Art. 18 (Investigation and preparation of indictment): 1. The Prosecutor shall initiate investigations ex-officio or on the basis of information obtained from any source, particularly from Governments, United Nations organs, intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations. The Prosecutor shall assess the information received or obtained and decide whethere is sufficient basis to proceed. 2. The Prosecutor shall have the power to question suspects, victims and witnesses, to collect evidence and to conduct on-site investigations. In carrying out these tasks, the Prosecutor may, as appropriate, seek the assistance of the State authorities concerned. 3. If questioned, the suspect shall be entitled to be assisted by counsel of his own choice, including the right to have legal assistance assigned to him without payment by him in any such case if he does not have sufficient means to pay for it, as well as to necessary translation into and from a language he speaks and understands. 4. Upon a determination that a prima facie case exists, the Prosecutor shall prepare an indictment containing a concise statement of the facts and the crime or crimes with which the accused is charged under the Statute. The indictment shall be transmitted to a judge of the Trial Chamber.

• Article 19 (Review of the indictment) 1. The judge of the Trial Chamber to whom the indictment has been transmitted shall review it. If satisfied that a prima facie case has been established by the Prosecutor, he shall confirm the indictment. If not so satisfied, the indictment shall be dismissed. 2. Upon confirmation of an indictment, the judge may, at the request of the Prosecutor, issue such orders and warrants for the arrest, detention, surrender or transfer of persons, and any other orders as may be required for the conduct of the trial. • Article 20 (Commencement and conduct of trial proceedings): 1. The Trial Chambers shall ensure that a trial is fair and expeditious and that proceedings are conducted in accordance with the rules of procedure and evidence, with full respect for the rights of the accused and due regard for the protection of victims and witnesses. 2. A person against whom an indictment has been confirmed shall, pursuant to an order or an arrest warrant of the International Tribunal, be taken into custody, immediately informed of the charges against him and transferred to the International Tribunal. 3. The Trial Chamber shall read the indictment, satisfy itself that the rights of the accused are respected, confirm that the accused understands the indictment, and instruct the accused to enter a plea. The Trial Chamber shall then set the date for trial. 4. The hearings shall be public unless the Trial Chamber decides to close the proceedings in accordance with its rules of procedure and evidence.