e0ac72dcc9e3a3eec89577bab3c6d7d4.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 18

Latinos in Technology This is the Aztec Calendar, perhaps the most famous symbol of Mexico, besides its flag. The original object is a circular stone slab with a diameter of 12 feet from the Pre-Columbian time period. Many renditions of it exist and have existed through the years and throughout Mexico. The actual physical object from which this image was rendered is a metal plate about 16" in diameter. The colored areas were painted in enamel. Historically, the Aztec name for the huge basaltic monolith is Cuauhxicalli (Eagle Bowl), but it is universally known as the Aztec Calendar or Sun Stone. It was during the reign of the 6 th Aztec monarch in 1479 that this stone was carved and dedicated to the principal Aztec deity: the sun. The stone has both mythological and astronomical significance. It weighs almost 25 tons, has a diameter of just under 12 feet, and a thickness of 3 feet. On December 17 th, 1760 the stone was discovered, buried in the "Zocalo" (the main square) of Mexico City. The viceroy of New Spain at the time was don Joaquin de Monserrat, Marquis of Cruillas. Afterwards it was embedded in the wall of the Western tower of the metropolitan Cathedral, where it remained until 1885. At that time it was transferred to the national Museum of Archaeology and History by order of then President of the Republic, General Porfirio Diaz.

Latinos in Technology This is the Aztec Calendar, perhaps the most famous symbol of Mexico, besides its flag. The original object is a circular stone slab with a diameter of 12 feet from the Pre-Columbian time period. Many renditions of it exist and have existed through the years and throughout Mexico. The actual physical object from which this image was rendered is a metal plate about 16" in diameter. The colored areas were painted in enamel. Historically, the Aztec name for the huge basaltic monolith is Cuauhxicalli (Eagle Bowl), but it is universally known as the Aztec Calendar or Sun Stone. It was during the reign of the 6 th Aztec monarch in 1479 that this stone was carved and dedicated to the principal Aztec deity: the sun. The stone has both mythological and astronomical significance. It weighs almost 25 tons, has a diameter of just under 12 feet, and a thickness of 3 feet. On December 17 th, 1760 the stone was discovered, buried in the "Zocalo" (the main square) of Mexico City. The viceroy of New Spain at the time was don Joaquin de Monserrat, Marquis of Cruillas. Afterwards it was embedded in the wall of the Western tower of the metropolitan Cathedral, where it remained until 1885. At that time it was transferred to the national Museum of Archaeology and History by order of then President of the Republic, General Porfirio Diaz.

The Influences are Everywhere From Astronomical observatories of the lowland Mayas in Tikal …. . To the great city of Teotihuacan, that at the time of the discovery was larger than any city in Europe.

The Influences are Everywhere From Astronomical observatories of the lowland Mayas in Tikal …. . To the great city of Teotihuacan, that at the time of the discovery was larger than any city in Europe.

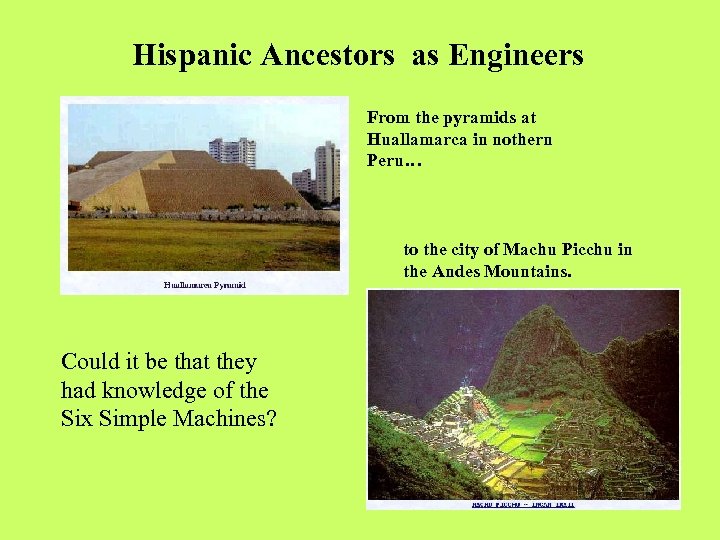

Hispanic Ancestors as Engineers From the pyramids at Huallamarca in nothern Peru… to the city of Machu Picchu in the Andes Mountains. Could it be that they had knowledge of the Six Simple Machines?

Hispanic Ancestors as Engineers From the pyramids at Huallamarca in nothern Peru… to the city of Machu Picchu in the Andes Mountains. Could it be that they had knowledge of the Six Simple Machines?

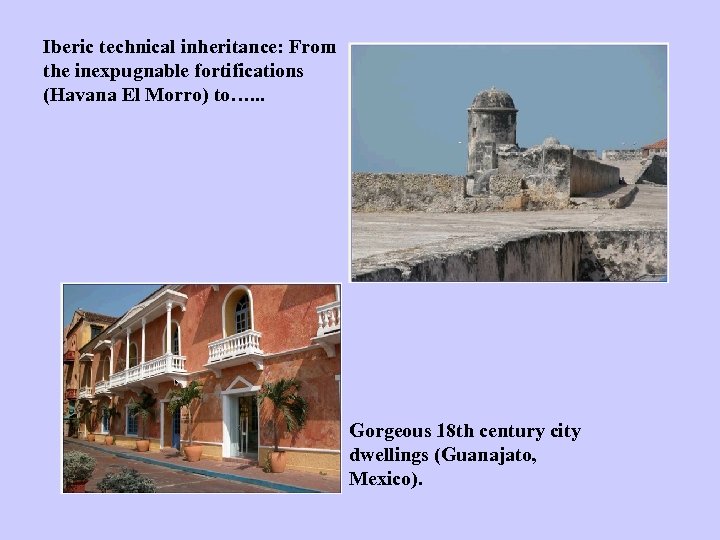

Iberic technical inheritance: From the inexpugnable fortifications (Havana El Morro) to…. . . Gorgeous 18 th century city dwellings (Guanajato, Mexico).

Iberic technical inheritance: From the inexpugnable fortifications (Havana El Morro) to…. . . Gorgeous 18 th century city dwellings (Guanajato, Mexico).

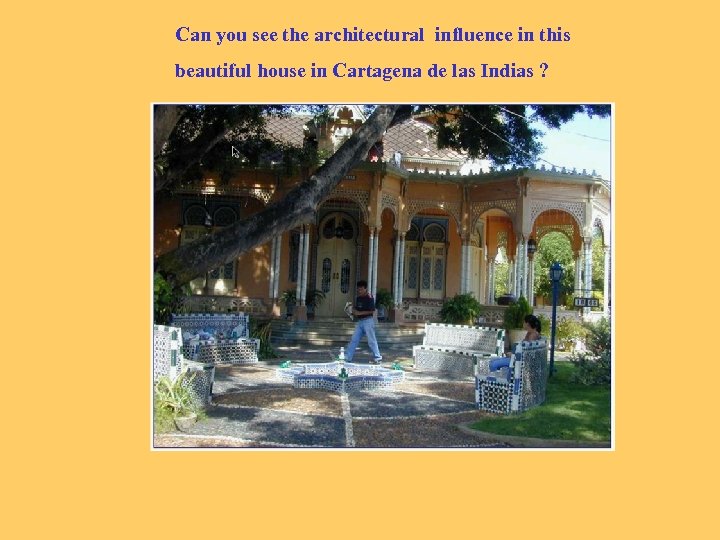

Can you see the architectural influence in this beautiful house in Cartagena de las Indias ?

Can you see the architectural influence in this beautiful house in Cartagena de las Indias ?

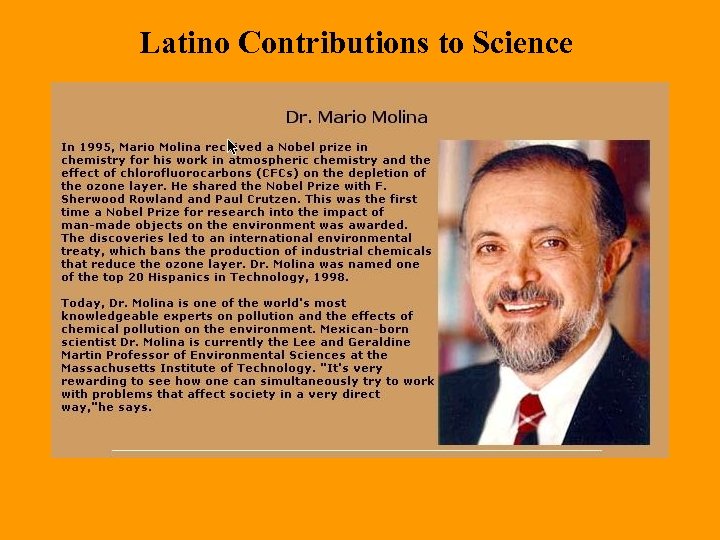

Latino Contributions to Science

Latino Contributions to Science

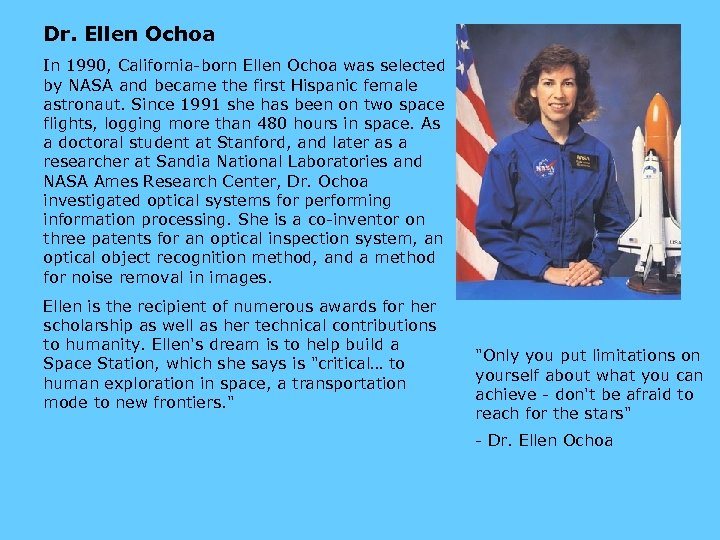

Dr. Ellen Ochoa In 1990, California-born Ellen Ochoa was selected by NASA and became the first Hispanic female astronaut. Since 1991 she has been on two space flights, logging more than 480 hours in space. As a doctoral student at Stanford, and later as a researcher at Sandia National Laboratories and NASA Ames Research Center, Dr. Ochoa investigated optical systems for performing information processing. She is a co-inventor on three patents for an optical inspection system, an optical object recognition method, and a method for noise removal in images. Ellen is the recipient of numerous awards for her scholarship as well as her technical contributions to humanity. Ellen's dream is to help build a Space Station, which she says is "critical… to human exploration in space, a transportation mode to new frontiers. " "Only you put limitations on yourself about what you can achieve - don't be afraid to reach for the stars" - Dr. Ellen Ochoa

Dr. Ellen Ochoa In 1990, California-born Ellen Ochoa was selected by NASA and became the first Hispanic female astronaut. Since 1991 she has been on two space flights, logging more than 480 hours in space. As a doctoral student at Stanford, and later as a researcher at Sandia National Laboratories and NASA Ames Research Center, Dr. Ochoa investigated optical systems for performing information processing. She is a co-inventor on three patents for an optical inspection system, an optical object recognition method, and a method for noise removal in images. Ellen is the recipient of numerous awards for her scholarship as well as her technical contributions to humanity. Ellen's dream is to help build a Space Station, which she says is "critical… to human exploration in space, a transportation mode to new frontiers. " "Only you put limitations on yourself about what you can achieve - don't be afraid to reach for the stars" - Dr. Ellen Ochoa

Dr. Manuel Berriozábal - Mathematician I attended college at Rockhurst College in Kansas City, Missouri, where I studied mathematics, earning my B. S. degree in 1952. A professor of mine at Rockhurst, Father William C. Doyle, urged me to continue my mathematicalstudies. I began my graduate studies at Notre Dame in 1952, but was interrupted with a tour in the Army. I completed the master’s degree in 1956. From 1957 to 1959, I taught at what is now Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. In 1961, I earned my Ph. D. in mathematics from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), where I wrote my dissertation on topology. After completing my Ph. D. , I taught at UCLA, Tulane University and then the University of New Orleans. In 1976, I joined the faculty at The University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA), which has essentially brought me home. I am currently a professor of mathematics at UTSA.

Dr. Manuel Berriozábal - Mathematician I attended college at Rockhurst College in Kansas City, Missouri, where I studied mathematics, earning my B. S. degree in 1952. A professor of mine at Rockhurst, Father William C. Doyle, urged me to continue my mathematicalstudies. I began my graduate studies at Notre Dame in 1952, but was interrupted with a tour in the Army. I completed the master’s degree in 1956. From 1957 to 1959, I taught at what is now Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. In 1961, I earned my Ph. D. in mathematics from the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), where I wrote my dissertation on topology. After completing my Ph. D. , I taught at UCLA, Tulane University and then the University of New Orleans. In 1976, I joined the faculty at The University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA), which has essentially brought me home. I am currently a professor of mathematics at UTSA.

Dr. Emir Jose Macari - Civil Engineer Coincidence? My Parents met in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, as students at Louisiana State University. My father was from Mexico and came to the United States to study Chemical Engineering, and my mother, a Cuban-American, was studying Nutrition. This duality in cultures is mirrored in my own life experiences. After my parents married and my sister was born in Baton Rouge, they moved to Mexico City, where I was born. From then on I lived half of my life in the US and the other half in Mexico. I completed high school in Mexico City and then came back to the US for college and eventually graduate school. After holding positions in Puerto Rico and Georgia, I have returned to live and work at the place where my parents met, LSU! What a coincidence. I am currently the Chairman of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the Bingham C. Stewart Endowed Distinguished Professor of Engineering (my position is funded by a $2, 000 endowment). My research activities are paid from the interest that the endowment earns each year. With this money I am able to support undergraduates, graduate students and postdoctoral students who work with me on many different research projects (computational mechanics, earthquake engineering, sustainable technologies and the use of virtual reality in engineering education).

Dr. Emir Jose Macari - Civil Engineer Coincidence? My Parents met in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, as students at Louisiana State University. My father was from Mexico and came to the United States to study Chemical Engineering, and my mother, a Cuban-American, was studying Nutrition. This duality in cultures is mirrored in my own life experiences. After my parents married and my sister was born in Baton Rouge, they moved to Mexico City, where I was born. From then on I lived half of my life in the US and the other half in Mexico. I completed high school in Mexico City and then came back to the US for college and eventually graduate school. After holding positions in Puerto Rico and Georgia, I have returned to live and work at the place where my parents met, LSU! What a coincidence. I am currently the Chairman of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the Bingham C. Stewart Endowed Distinguished Professor of Engineering (my position is funded by a $2, 000 endowment). My research activities are paid from the interest that the endowment earns each year. With this money I am able to support undergraduates, graduate students and postdoctoral students who work with me on many different research projects (computational mechanics, earthquake engineering, sustainable technologies and the use of virtual reality in engineering education).

Dr. Alfonso Ortega - Mechanical Engineer I was born and raised in El Paso, Texas. My parents migrated to the United States for better job opportunities so as to provide for their eleven children. My parents are from ranchitos (small ranches) outside of Durango, Mexico. My father was a teacher in Mexico; but when he migrated to the U. S. he became a bricklayer, a trade he soon mastered. He loved his job and felt passionate about being a master bricklayer. My brother and I would often work for him. I owe a great deal of my love for building things to my father. He helped me understand appreciate the value of a good structure, as well as the beauty contained within it. I went to Bel Air High School in El Paso. During high school I worked hard, and eventually I won a scholarship to Rice University, a university of high reputation. However, when I told my parents about my opportunity, they weren’t very enthusiastic about it. Though they didn’t stop me from attending Rice, they never gave me the approval I felt was necessary. I decided instead to go to the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). I have never regretted this decision, for I believe I received an excellent education. At that time the school catered to undergraduates, and I learned the essentials I would need to become a successful engineer. One professor I had at UTEP, Professor Jack Dowdy, introduced me to the engineering problems surrounding heat exchange, and set me on a course that continues to this very day. It is amazing the impact that a few small comments can have on a student. I received my B. S. degree with honors in mechanical engineering from UTEP in 1976. In January 1977, I started work at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, participating in the One Year On Campus (OYOC) program, which is meant to help minorities and women get higher degrees. I consider myself to be a case study in how the system works for getting minorities and women into advanced degrees through national laboratories. I saw people with advanced degrees doing the things I wanted to do, and that having a graduate degree in engineering was the key to success. In August 1977, I left Sandia and headed to Stanford University. I was enrolled in an intensive one-year master’s degree program. That first quarter at Stanford was the toughest that I had ever experienced. At UTEP I was used to being the top student, and things just seemed to come to me naturally. However, the higher the educational level, the more dedicated the students are. For the first time in my career I was not easily the top student in my classes. I earned my master’s degree and then returned to Sandia where I continued to work. Seeing the need for even higher education, after two and a half years I returned to Stanford to pursue my Ph. D. under the Sandia Laboratories advanced degree program. At Stanford I worked as a research assistant with Professor Bob Moffat on heat exchange problems in engineering. After five years I obtained my Ph. D. , and then returned again to Sandia. On the side I worked as an adjunct professor at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, where I learned that I enjoyed university teaching. I wasn’t looking for a position when I received a request from the University of Arizona (UA) to interview for a tenure track professorship. I had been recommended by my advisor at Stanford as a possible candidate for the position. I decided to interview, and I was offered and accepted the position in 1988. I am currently an Associate Professor, and the Director of the Experimental and Computational Heat Transfer Group, at UA.

Dr. Alfonso Ortega - Mechanical Engineer I was born and raised in El Paso, Texas. My parents migrated to the United States for better job opportunities so as to provide for their eleven children. My parents are from ranchitos (small ranches) outside of Durango, Mexico. My father was a teacher in Mexico; but when he migrated to the U. S. he became a bricklayer, a trade he soon mastered. He loved his job and felt passionate about being a master bricklayer. My brother and I would often work for him. I owe a great deal of my love for building things to my father. He helped me understand appreciate the value of a good structure, as well as the beauty contained within it. I went to Bel Air High School in El Paso. During high school I worked hard, and eventually I won a scholarship to Rice University, a university of high reputation. However, when I told my parents about my opportunity, they weren’t very enthusiastic about it. Though they didn’t stop me from attending Rice, they never gave me the approval I felt was necessary. I decided instead to go to the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). I have never regretted this decision, for I believe I received an excellent education. At that time the school catered to undergraduates, and I learned the essentials I would need to become a successful engineer. One professor I had at UTEP, Professor Jack Dowdy, introduced me to the engineering problems surrounding heat exchange, and set me on a course that continues to this very day. It is amazing the impact that a few small comments can have on a student. I received my B. S. degree with honors in mechanical engineering from UTEP in 1976. In January 1977, I started work at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, participating in the One Year On Campus (OYOC) program, which is meant to help minorities and women get higher degrees. I consider myself to be a case study in how the system works for getting minorities and women into advanced degrees through national laboratories. I saw people with advanced degrees doing the things I wanted to do, and that having a graduate degree in engineering was the key to success. In August 1977, I left Sandia and headed to Stanford University. I was enrolled in an intensive one-year master’s degree program. That first quarter at Stanford was the toughest that I had ever experienced. At UTEP I was used to being the top student, and things just seemed to come to me naturally. However, the higher the educational level, the more dedicated the students are. For the first time in my career I was not easily the top student in my classes. I earned my master’s degree and then returned to Sandia where I continued to work. Seeing the need for even higher education, after two and a half years I returned to Stanford to pursue my Ph. D. under the Sandia Laboratories advanced degree program. At Stanford I worked as a research assistant with Professor Bob Moffat on heat exchange problems in engineering. After five years I obtained my Ph. D. , and then returned again to Sandia. On the side I worked as an adjunct professor at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, where I learned that I enjoyed university teaching. I wasn’t looking for a position when I received a request from the University of Arizona (UA) to interview for a tenure track professorship. I had been recommended by my advisor at Stanford as a possible candidate for the position. I decided to interview, and I was offered and accepted the position in 1988. I am currently an Associate Professor, and the Director of the Experimental and Computational Heat Transfer Group, at UA.

Dr. George Castro - Engineer & Associate Dean I was not a very motivated undergraduate student. I received mostly C grades. It was circumstance and luck that brought me to graduate school. During my undergraduate years there was a draft for military service and I knew that when I finished school I would have to go into the army. I had never thought about graduate school before, but it sounded a lot better than going into the army. When University of California at Riverside (UCR) invited me to attend their graduate school, with tuition paid for, and a research job, I joyfully accepted. The only provision that the school mandated was that I receive B grades in my final semester at UCLA. For the first time in my life I had an academic goal. I worked hard and obtained A’s. The following semester I began UC Riverside graduate school. The experience of attending graduate school changed my whole world, I lived on campus, I did research, and earned a 4. 00 grade point average. I loved graduate school.

Dr. George Castro - Engineer & Associate Dean I was not a very motivated undergraduate student. I received mostly C grades. It was circumstance and luck that brought me to graduate school. During my undergraduate years there was a draft for military service and I knew that when I finished school I would have to go into the army. I had never thought about graduate school before, but it sounded a lot better than going into the army. When University of California at Riverside (UCR) invited me to attend their graduate school, with tuition paid for, and a research job, I joyfully accepted. The only provision that the school mandated was that I receive B grades in my final semester at UCLA. For the first time in my life I had an academic goal. I worked hard and obtained A’s. The following semester I began UC Riverside graduate school. The experience of attending graduate school changed my whole world, I lived on campus, I did research, and earned a 4. 00 grade point average. I loved graduate school.

Dr. Joan Esnayra - Geneticist Growing up in a home filled with alcoholism, domestic violence, sexual abuse, and mental illness, I can identify with the organisms called extremophiles that live in harsh environments like Antarctica or hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean. I am truly a survivor of extreme conditions. I grew up in a small town near Olympia, Washington. Home was always a violent and unpredictable place, so school became my safe haven and I excelled in my studies. I participated in student government, wrote for the school newspaper, participated in the speech and debate club, and played all kinds of sports. I also had the unique opportunity of sailing around the world in a small boat, with my father. He was not a rich man, but he was creative. For three to five months a year, for seven years, we sailed to exotic ports around the world. At the end of each summer, we anchored the boat in a foreign harbor, flew home on military planes, and I returned to school. The following year, we picked up the boat and continued our journey around the world. Over the years, we sailed to Hawaii, Tahiti, American Samoa, Australia, Israel, Algeria and Gibraltar. Sailing the world inspired me to become an ocean scientist like Jacques Cousteau. Through many years of education and personal healing, I earned my Ph. D. in Biology in 1999, nine years after I originally entered graduate school. In graduate school I studied genetics and my research was about how to create rules or policies for the development of new drugs. After graduate school, I started working as a program officer at the National Academies of Science (NAS) in Washington D. C. At NAS, I manage committees of scientists and scholars who advise the American government on matters of science and technology policy. I use my degree in philosophy as well, because I am interested in not only science, but also how we apply it to our lives, and the impact it has on our society and culture. I am excited by the work that I do at NAS, and I know that it is working hard at school that got me here. My education has completely changed my life in a very positive way. It has broadened my world-view and allowed me to celebrate human diversity. It has taught me that I can achieve anything I put my mind to.

Dr. Joan Esnayra - Geneticist Growing up in a home filled with alcoholism, domestic violence, sexual abuse, and mental illness, I can identify with the organisms called extremophiles that live in harsh environments like Antarctica or hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean. I am truly a survivor of extreme conditions. I grew up in a small town near Olympia, Washington. Home was always a violent and unpredictable place, so school became my safe haven and I excelled in my studies. I participated in student government, wrote for the school newspaper, participated in the speech and debate club, and played all kinds of sports. I also had the unique opportunity of sailing around the world in a small boat, with my father. He was not a rich man, but he was creative. For three to five months a year, for seven years, we sailed to exotic ports around the world. At the end of each summer, we anchored the boat in a foreign harbor, flew home on military planes, and I returned to school. The following year, we picked up the boat and continued our journey around the world. Over the years, we sailed to Hawaii, Tahiti, American Samoa, Australia, Israel, Algeria and Gibraltar. Sailing the world inspired me to become an ocean scientist like Jacques Cousteau. Through many years of education and personal healing, I earned my Ph. D. in Biology in 1999, nine years after I originally entered graduate school. In graduate school I studied genetics and my research was about how to create rules or policies for the development of new drugs. After graduate school, I started working as a program officer at the National Academies of Science (NAS) in Washington D. C. At NAS, I manage committees of scientists and scholars who advise the American government on matters of science and technology policy. I use my degree in philosophy as well, because I am interested in not only science, but also how we apply it to our lives, and the impact it has on our society and culture. I am excited by the work that I do at NAS, and I know that it is working hard at school that got me here. My education has completely changed my life in a very positive way. It has broadened my world-view and allowed me to celebrate human diversity. It has taught me that I can achieve anything I put my mind to.

My parents were from Puerto Rico. My father was an army officer surgeon and my mother was an elementary school teacher, and they always encouraged learning. My parents bought me a telescope for my tenth birthday. When the astronauts landed on the moon, I remember running back and forth between the television set and my telescope trying to see if I could catch a glimpse of the men on the moon. When I was in sixth grade my father left the military, and my family moved to Freeport, Illinois, where my father went in to private practice. It was then that I decided I wanted to be a physicist, sparked mainly by reading and the Apollo moon landings. I wanted to know how the universe worked. In ninth grade we moved outside of town, where I had to start a new school, Pearl City High School (PCHS), without any of my previous friends. At PCHS I had a wonderful science teacher, Jerry Heinrich, who loved science and loved to teach it to others. In 1974, Mr. Heinrich taught me to do a small amount of programming on an early computer he had. For me, science was always a large and important part of my life. Dr. Ramon E. Lopez Physicist Technically, I never graduated from high school. Stemming mainly from my “outgrowing” PCHS, I decided to go to college early. In the fall of 1976, I entered the University of Illinois (UI) as a physics major. It was quite a step going from a high school of 200 students to a major university with 35, 000 students. At first I did very poorly, as I felt significantly under-prepared for the challenges of college. In my first semester I earned under a C average. During the second semester I remember a particular calculus test. I had worked through many of the difficult problems at the end of the book, and I felt very prepared for the exam. I received a D, which was an eye-opening experience to me. I knew I wasn’t stupid; I had just studied stupidly. During that semester I finally learned to study wisely. I mastered the concepts rather than very specific problems, and I aced the next calculus test. Also during my first year, I studied very hard to fill in the gaps that were apparent from my lack of preparation. During my third semester at UI, I received straight A’s. Though I was indisputably a physics major, I had other interests as well. In fact, if I wasn’t a physicist, I think I’d be a historian. During school I worked in the physics department setting up lecture demonstrations, which was a great job for a student. I could study, and I came into contact with many of the professors I wouldn’t have known otherwise. I also wrote articles about physics for the school newspaper as an undergraduate, which helped me immensely later in life. Though it doesn’t seem like it, scientists actually write for a living; so the experience of writing for the newspaper was invaluable. I was even encouraged to go to school and receive a Master’s in journalism. But I’d wanted a Ph. D. in physics since middle school, so I pursued that dream instead. I received a National Science Foundation minority graduate fellowship to attend graduate school, where I knew I would study space science. I decided to attend Rice University in Houston for graduate school partly because I was tired of the cold winters in Illinois. At Rice, things were different than at UI. The graduate students in space science were a close knit group as opposed to the large department I’d come from. It was very difficult in graduate school, and all of us in the program had to become more serious and focused. I even thought about dropping out after the first year due to isolation from the other things that I loved, such as literature, history, art and philosophy, which I was used to being a part of at UI. However, I persevered; and in 1986 I received my Ph. D. in Space Physics. Fresh out of graduate school, I began doing pure research in space physics at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab (APL). I left APL because I wanted to put more effort into educational projects, which I did at the University of Maryland at College Park (UMCP). When I was 34, I became the Director of Education for the American Physical Society (APS); and for five years I ran all of the education programs for APS while still working half time at UMCP. However, after five years doing both jobs, I’d had enough. I wanted a faculty position. In 1999, I obtained a position at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). I was appointed C. Sharp Cook Distinguished Professor of Physics and Chair of the Department of Physics at UTEP.

My parents were from Puerto Rico. My father was an army officer surgeon and my mother was an elementary school teacher, and they always encouraged learning. My parents bought me a telescope for my tenth birthday. When the astronauts landed on the moon, I remember running back and forth between the television set and my telescope trying to see if I could catch a glimpse of the men on the moon. When I was in sixth grade my father left the military, and my family moved to Freeport, Illinois, where my father went in to private practice. It was then that I decided I wanted to be a physicist, sparked mainly by reading and the Apollo moon landings. I wanted to know how the universe worked. In ninth grade we moved outside of town, where I had to start a new school, Pearl City High School (PCHS), without any of my previous friends. At PCHS I had a wonderful science teacher, Jerry Heinrich, who loved science and loved to teach it to others. In 1974, Mr. Heinrich taught me to do a small amount of programming on an early computer he had. For me, science was always a large and important part of my life. Dr. Ramon E. Lopez Physicist Technically, I never graduated from high school. Stemming mainly from my “outgrowing” PCHS, I decided to go to college early. In the fall of 1976, I entered the University of Illinois (UI) as a physics major. It was quite a step going from a high school of 200 students to a major university with 35, 000 students. At first I did very poorly, as I felt significantly under-prepared for the challenges of college. In my first semester I earned under a C average. During the second semester I remember a particular calculus test. I had worked through many of the difficult problems at the end of the book, and I felt very prepared for the exam. I received a D, which was an eye-opening experience to me. I knew I wasn’t stupid; I had just studied stupidly. During that semester I finally learned to study wisely. I mastered the concepts rather than very specific problems, and I aced the next calculus test. Also during my first year, I studied very hard to fill in the gaps that were apparent from my lack of preparation. During my third semester at UI, I received straight A’s. Though I was indisputably a physics major, I had other interests as well. In fact, if I wasn’t a physicist, I think I’d be a historian. During school I worked in the physics department setting up lecture demonstrations, which was a great job for a student. I could study, and I came into contact with many of the professors I wouldn’t have known otherwise. I also wrote articles about physics for the school newspaper as an undergraduate, which helped me immensely later in life. Though it doesn’t seem like it, scientists actually write for a living; so the experience of writing for the newspaper was invaluable. I was even encouraged to go to school and receive a Master’s in journalism. But I’d wanted a Ph. D. in physics since middle school, so I pursued that dream instead. I received a National Science Foundation minority graduate fellowship to attend graduate school, where I knew I would study space science. I decided to attend Rice University in Houston for graduate school partly because I was tired of the cold winters in Illinois. At Rice, things were different than at UI. The graduate students in space science were a close knit group as opposed to the large department I’d come from. It was very difficult in graduate school, and all of us in the program had to become more serious and focused. I even thought about dropping out after the first year due to isolation from the other things that I loved, such as literature, history, art and philosophy, which I was used to being a part of at UI. However, I persevered; and in 1986 I received my Ph. D. in Space Physics. Fresh out of graduate school, I began doing pure research in space physics at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab (APL). I left APL because I wanted to put more effort into educational projects, which I did at the University of Maryland at College Park (UMCP). When I was 34, I became the Director of Education for the American Physical Society (APS); and for five years I ran all of the education programs for APS while still working half time at UMCP. However, after five years doing both jobs, I’d had enough. I wanted a faculty position. In 1999, I obtained a position at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). I was appointed C. Sharp Cook Distinguished Professor of Physics and Chair of the Department of Physics at UTEP.

Dr. Theresa Maldonado - Electrical Engineer Both my parents are Texans, but I was born at Travis Air Force Base, California, and grew up in California, North Dakota, Georgia, and Texas. My parents first language was Spanish, but they chose not to teach us Spanish so that we would never face discrimination due to an accent. I am the oldest of five children, with two brothers and two sisters. I am the first person in my family to attend college. In an unusual turn of events, my decision to attend college motivated my parents to attend college as well. When I was growing up, I was taught that school should come after all of my other responsibilities at home. Because of this I felt guilty for pursuing an education. In traditional Mexican-American culture, girls are often taught to take care of the house and family, whereas men are in charge and do things outside the home. However, being the oldest, I always had to take care of the others, which put me in a leadership role. This experience would help me later in my education. I went to thirteen different schools between kindergarten and twelfth grade. Although military schools are excellent, I did not get a strong science background. Junior high was when the pace of my educational development accelerated. I was placed in advanced classes in English, mathematics, science, and social studies. My trigonometry and calculus teachers were very encouraging. My calculus teacher, in fact, suggested that I consider engineering as my major in college, but I just thought ”What the heck is that? ” I was also in the concert band on the basketball team. I learned some very valuable lessons from basketball in those years. We would have two hours of practice, and the first hour and a half focused only on the fundamentals - running, dribbling, shooting, etc. The last half hour was spent on strategy. I began to realize that by concentrating on fundamentals, whether in athletics or academics, a person will have the abilities needed to excel at other things. After graduating high school, I attended a junior college in Georgia. My goal was to be a high school mathematics teacher. I took one education class, and I ended up changing my mind. I had one very interesting calculus professor at this school. My perception was that he was sexist, and he made a couple of comments in class that substantiated my thoughts. I remember one time he asked one of the two other girls in my calculus class a question, and when she didn’t know the answer, he shouted ”You women belong in the kitchen!” Pretty soon I was the only female left in my calculus class. However, this same teacher told me at the end of the year that I should consider applying to Georgia Institute of Technology after I got my two year degree, and that I should try engineering. Although I was offended by this person at first, he ended up being very encouraging and gave me real motivation to focus on engineering. I chose electrical engineering rather blindly, but I did know that mathematics was my ticket to engineering. I ended up making straight As my first quarter there. There were not very many women in the electrical engineering department at Georgia Tech. I was usually one of two or three women in a class of 80. That fact alone made me uncomfortable. I was afraid to ask my professors questions. I would spend hours trying to figure out trivial things so that I wouldn’t have to approach the professors. In general, I found engineering and mathematics faculty to be very uncommunicative. I graduated with a 3. 8 GPA and was recruited by a company that sent me back to school for my master’s degree in electrical engineering. I finished my Ph. D. in electrical engineering in 1990, and accepted a faculty position at University of Texas, Arlington. Finally, after all these years, I am the teacher I wanted to be. It is very important that I am a female who is a professor of engineering. Over the years I have had to listen to comments from others who said I was not qualified. I had to convince myself that I was qualified and that I would get my Ph. D. By concentrating on the fundamentals, I have attained a position that I truly enjoy, and that is the most important point.

Dr. Theresa Maldonado - Electrical Engineer Both my parents are Texans, but I was born at Travis Air Force Base, California, and grew up in California, North Dakota, Georgia, and Texas. My parents first language was Spanish, but they chose not to teach us Spanish so that we would never face discrimination due to an accent. I am the oldest of five children, with two brothers and two sisters. I am the first person in my family to attend college. In an unusual turn of events, my decision to attend college motivated my parents to attend college as well. When I was growing up, I was taught that school should come after all of my other responsibilities at home. Because of this I felt guilty for pursuing an education. In traditional Mexican-American culture, girls are often taught to take care of the house and family, whereas men are in charge and do things outside the home. However, being the oldest, I always had to take care of the others, which put me in a leadership role. This experience would help me later in my education. I went to thirteen different schools between kindergarten and twelfth grade. Although military schools are excellent, I did not get a strong science background. Junior high was when the pace of my educational development accelerated. I was placed in advanced classes in English, mathematics, science, and social studies. My trigonometry and calculus teachers were very encouraging. My calculus teacher, in fact, suggested that I consider engineering as my major in college, but I just thought ”What the heck is that? ” I was also in the concert band on the basketball team. I learned some very valuable lessons from basketball in those years. We would have two hours of practice, and the first hour and a half focused only on the fundamentals - running, dribbling, shooting, etc. The last half hour was spent on strategy. I began to realize that by concentrating on fundamentals, whether in athletics or academics, a person will have the abilities needed to excel at other things. After graduating high school, I attended a junior college in Georgia. My goal was to be a high school mathematics teacher. I took one education class, and I ended up changing my mind. I had one very interesting calculus professor at this school. My perception was that he was sexist, and he made a couple of comments in class that substantiated my thoughts. I remember one time he asked one of the two other girls in my calculus class a question, and when she didn’t know the answer, he shouted ”You women belong in the kitchen!” Pretty soon I was the only female left in my calculus class. However, this same teacher told me at the end of the year that I should consider applying to Georgia Institute of Technology after I got my two year degree, and that I should try engineering. Although I was offended by this person at first, he ended up being very encouraging and gave me real motivation to focus on engineering. I chose electrical engineering rather blindly, but I did know that mathematics was my ticket to engineering. I ended up making straight As my first quarter there. There were not very many women in the electrical engineering department at Georgia Tech. I was usually one of two or three women in a class of 80. That fact alone made me uncomfortable. I was afraid to ask my professors questions. I would spend hours trying to figure out trivial things so that I wouldn’t have to approach the professors. In general, I found engineering and mathematics faculty to be very uncommunicative. I graduated with a 3. 8 GPA and was recruited by a company that sent me back to school for my master’s degree in electrical engineering. I finished my Ph. D. in electrical engineering in 1990, and accepted a faculty position at University of Texas, Arlington. Finally, after all these years, I am the teacher I wanted to be. It is very important that I am a female who is a professor of engineering. Over the years I have had to listen to comments from others who said I was not qualified. I had to convince myself that I was qualified and that I would get my Ph. D. By concentrating on the fundamentals, I have attained a position that I truly enjoy, and that is the most important point.