5491895422b42998c6bb34f68d9c3405.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 34

Is the Current ESA Working? 4 Recovery Plans have been required since 1978 4 Plan’s goals are to restore the listed species to a point where they are viable, selfsustaining components of their ecosystems 4 Tear et al. (1993) reviewed 54 plans on T & E species filed up to that time

Is the Current ESA Working? 4 Recovery Plans have been required since 1978 4 Plan’s goals are to restore the listed species to a point where they are viable, selfsustaining components of their ecosystems 4 Tear et al. (1993) reviewed 54 plans on T & E species filed up to that time

Are Recovery Plans Adequate? (Tear et al. 1993) 4 28% had recovery goals calling for populations of smaller size than current 4 37% called for fewer populations than present 4 60% had goals below that used by IUCN (red list) to define endangered 4 So, we seem to be managing species to extinction, not recovery

Are Recovery Plans Adequate? (Tear et al. 1993) 4 28% had recovery goals calling for populations of smaller size than current 4 37% called for fewer populations than present 4 60% had goals below that used by IUCN (red list) to define endangered 4 So, we seem to be managing species to extinction, not recovery

Alternative Ways to Score ESA Effectiveness (Noecker 1998, USFWS web page) 4 Are species recovered to level where protection is no longer required? – NO, as of 2018 only 85 have been delisted • 52 due to recovery – Brown Pelican, Palau fantail flycatcher, Palau ground-dove, Palau owl, Tinian Monarch, American alligator, Gray whale, Arctic and American peregrines, Aleutian Canada Goose, Robbins’ Cinquefoil, Douglas Co population of Columbia White-tailed Deer, 3 species of kangaroos, Bald Eagle, Gray Wolf, YNP Grizzly, etc… » reasons for endangerment (DDT, WWII, overharvest) • 11 went extinct (eastern Puma) and 21 were delisted due to revision in taxonomy, new or improved data (mostly taxonomic revision, Mexican Duck)

Alternative Ways to Score ESA Effectiveness (Noecker 1998, USFWS web page) 4 Are species recovered to level where protection is no longer required? – NO, as of 2018 only 85 have been delisted • 52 due to recovery – Brown Pelican, Palau fantail flycatcher, Palau ground-dove, Palau owl, Tinian Monarch, American alligator, Gray whale, Arctic and American peregrines, Aleutian Canada Goose, Robbins’ Cinquefoil, Douglas Co population of Columbia White-tailed Deer, 3 species of kangaroos, Bald Eagle, Gray Wolf, YNP Grizzly, etc… » reasons for endangerment (DDT, WWII, overharvest) • 11 went extinct (eastern Puma) and 21 were delisted due to revision in taxonomy, new or improved data (mostly taxonomic revision, Mexican Duck)

Alternative Ways to Score ESA Effectiveness (Noecker 1998) 4 Have populations of listed species become more stable since listing? – Maybe (estimate 41% of 1676 species have improved or stabilized) – 18 currently proposed for downlisting

Alternative Ways to Score ESA Effectiveness (Noecker 1998) 4 Have populations of listed species become more stable since listing? – Maybe (estimate 41% of 1676 species have improved or stabilized) – 18 currently proposed for downlisting

Alternative Ways to Score ESA Effectiveness (Noecker 1998, USFWS) 4 Has listing prevented extinction? – YES, only 11 of the >2300 listed species have gone extinct • Guam Broadbill, Longjaw Cisco, Amistad Gambusia, Mariana Mallard, Sampson’s Pearlymussel, Blue Pike, Pecopa Pupfish, Santa Barbara Song Sparrow, Dusky Seaside Sparrow – some of these were actually extinct at time of listing! • Condor, Red Wolf, Whooping Crane would likely be extinct without the Act

Alternative Ways to Score ESA Effectiveness (Noecker 1998, USFWS) 4 Has listing prevented extinction? – YES, only 11 of the >2300 listed species have gone extinct • Guam Broadbill, Longjaw Cisco, Amistad Gambusia, Mariana Mallard, Sampson’s Pearlymussel, Blue Pike, Pecopa Pupfish, Santa Barbara Song Sparrow, Dusky Seaside Sparrow – some of these were actually extinct at time of listing! • Condor, Red Wolf, Whooping Crane would likely be extinct without the Act

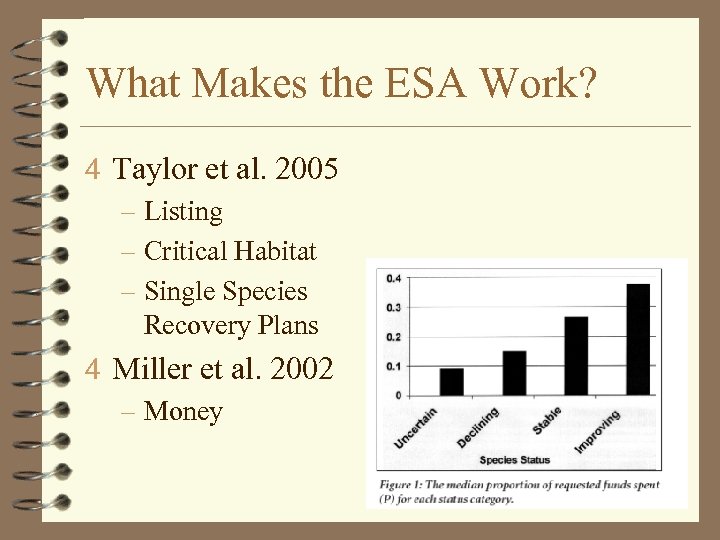

What Makes the ESA Work? 4 Taylor et al. 2005 – Listing – Critical Habitat – Single Species Recovery Plans 4 Miller et al. 2002 – Money

What Makes the ESA Work? 4 Taylor et al. 2005 – Listing – Critical Habitat – Single Species Recovery Plans 4 Miller et al. 2002 – Money

Recent Evaluations of Recovery Plans (Boersma et al. 2001) 4 Effective recovery plans (those associated with increasing population trends) are those with: – Non-federal participation, especially on the Recovery Team – Recovery goals clearly linked to species biology – Focus on single, rather than multiple, species 4 Planning can be improved by: – Increasing speed of prep – Monitoring management actions – Using adaptive management 4 But the measurement of success (species status trend) is influenced by myriad factors of which the recovery plan is but one. Therefore, while suggestive, the results are far from definitive.

Recent Evaluations of Recovery Plans (Boersma et al. 2001) 4 Effective recovery plans (those associated with increasing population trends) are those with: – Non-federal participation, especially on the Recovery Team – Recovery goals clearly linked to species biology – Focus on single, rather than multiple, species 4 Planning can be improved by: – Increasing speed of prep – Monitoring management actions – Using adaptive management 4 But the measurement of success (species status trend) is influenced by myriad factors of which the recovery plan is but one. Therefore, while suggestive, the results are far from definitive.

Does the ESA protect Ecosystems? (NRC 1995) 4 Difficult to tell--most emphasis is on single species 4 Of 411 recovery plans, 25% include multiple species – some cover full communities (Ash Meadows, Maui-Molokai birds, Channel Islands) 4 Even single species plans can protect ecosystems – spotted owl, marbled murrelet

Does the ESA protect Ecosystems? (NRC 1995) 4 Difficult to tell--most emphasis is on single species 4 Of 411 recovery plans, 25% include multiple species – some cover full communities (Ash Meadows, Maui-Molokai birds, Channel Islands) 4 Even single species plans can protect ecosystems – spotted owl, marbled murrelet

Could the ESA be Strengthened? (Carroll et al. 1996) 4 Yes, by basing many of the decisions and priorities on sound conservation science – listing • do it faster • extend population level protection to plants (including fungi) • use ESU concept to define “species” • adjust priority scheme to include – Inclusive benefits (umbrella species like Florida Scrub Jay) – Ecological role (keystone species)

Could the ESA be Strengthened? (Carroll et al. 1996) 4 Yes, by basing many of the decisions and priorities on sound conservation science – listing • do it faster • extend population level protection to plants (including fungi) • use ESU concept to define “species” • adjust priority scheme to include – Inclusive benefits (umbrella species like Florida Scrub Jay) – Ecological role (keystone species)

Use More Science in the Recovery Planning Arena Also 4 Use PVA and Sink-Source models to define critical habitat size and spatial arrangement 4 Take a more holistic approach – still focus on species (not ecosystems), but more likely to protect HABITAT not just species 4 Provide tangible standards of jeopardy for particular federal actions 4 Set recovery and de-listing goals that will result in viable populations – need to be flexible as populations are rarely naturally stable

Use More Science in the Recovery Planning Arena Also 4 Use PVA and Sink-Source models to define critical habitat size and spatial arrangement 4 Take a more holistic approach – still focus on species (not ecosystems), but more likely to protect HABITAT not just species 4 Provide tangible standards of jeopardy for particular federal actions 4 Set recovery and de-listing goals that will result in viable populations – need to be flexible as populations are rarely naturally stable

Science and Recovery Planning (Carroll et al. 1996) 4 Setting Goals for Recovery – Establish multiple populations with possibility for migration among them • removes effect of single catastrophe – Move to stop known threats • stop decline and possible extinction of species – Plan to achieve annual population growth rates above 0 • requires habitat analysis and knowledge of spatial distribution of species (metapopulation structure)

Science and Recovery Planning (Carroll et al. 1996) 4 Setting Goals for Recovery – Establish multiple populations with possibility for migration among them • removes effect of single catastrophe – Move to stop known threats • stop decline and possible extinction of species – Plan to achieve annual population growth rates above 0 • requires habitat analysis and knowledge of spatial distribution of species (metapopulation structure)

Setting Recovery Targets 4 Should they be detailed? – Need well parameterized PVA – They will be used for down-listing targets – Make sure you have DATA to support need to reach target 4 Should they be rigid? – Populations don’t remain stable through time (Carroll et al. 1996) – Give range of acceptable fluctuation 4 Should they be revised? – As data become available

Setting Recovery Targets 4 Should they be detailed? – Need well parameterized PVA – They will be used for down-listing targets – Make sure you have DATA to support need to reach target 4 Should they be rigid? – Populations don’t remain stable through time (Carroll et al. 1996) – Give range of acceptable fluctuation 4 Should they be revised? – As data become available

Dealing With Uncertainty 4 At time of recovery planning we rarely know what is needed to effectively recover a species – Interim Recovery Goals (Carroll et al. 1996) provide a bridge between initiating recovery and finalizing a recovery strategy • determine and state data needs for full PVA • give a biologically attainable target for first few years – reduce or stabilize decline – start active management/husbandry – get population to size x • assess possible limiting factors

Dealing With Uncertainty 4 At time of recovery planning we rarely know what is needed to effectively recover a species – Interim Recovery Goals (Carroll et al. 1996) provide a bridge between initiating recovery and finalizing a recovery strategy • determine and state data needs for full PVA • give a biologically attainable target for first few years – reduce or stabilize decline – start active management/husbandry – get population to size x • assess possible limiting factors

Admit Uncertainty (Marbled Murrelet Recovery Plan) – Objectives • gather necessary information to develop scientific delisting criteria – reasonable, attainable, and adequate to maintain the species over period of reduced habitat availability over next 50 years (then expect habitat to have regrown) – Interim Delisting Criteria • trend in population size, density, and productivity are stable or increasing in 4/6 zones over 10 years (including an El Nino) • Management commitments and monitoring are in place in all zones – ID critical habitat, have habitat protection plans in place

Admit Uncertainty (Marbled Murrelet Recovery Plan) – Objectives • gather necessary information to develop scientific delisting criteria – reasonable, attainable, and adequate to maintain the species over period of reduced habitat availability over next 50 years (then expect habitat to have regrown) – Interim Delisting Criteria • trend in population size, density, and productivity are stable or increasing in 4/6 zones over 10 years (including an El Nino) • Management commitments and monitoring are in place in all zones – ID critical habitat, have habitat protection plans in place

Address Habitat Concerns (Carroll et al. 1996) 4 Determine extent of currently suitable habitat 4 Assess quality of formerly occupied, but currently unoccupied habitat 4 Establish priority habitat areas for restoration – how should restoration be done?

Address Habitat Concerns (Carroll et al. 1996) 4 Determine extent of currently suitable habitat 4 Assess quality of formerly occupied, but currently unoccupied habitat 4 Establish priority habitat areas for restoration – how should restoration be done?

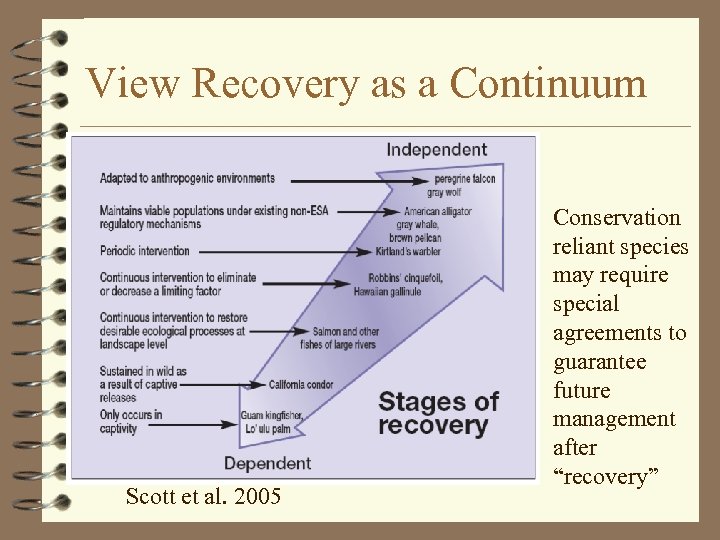

View Recovery as a Continuum Scott et al. 2005 Conservation reliant species may require special agreements to guarantee future management after “recovery”

View Recovery as a Continuum Scott et al. 2005 Conservation reliant species may require special agreements to guarantee future management after “recovery”

Evolving Condor Recovery

Evolving Condor Recovery

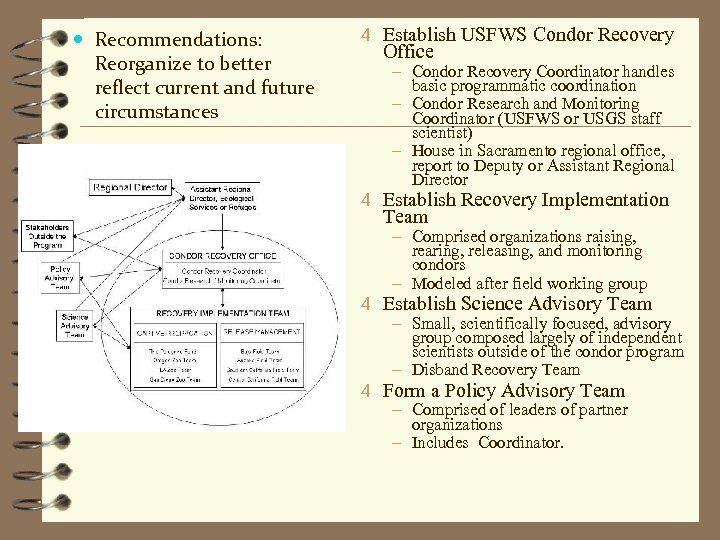

Recommendations: Reorganize to better reflect current and future circumstances 4 Establish USFWS Condor Recovery Office – Condor Recovery Coordinator handles basic programmatic coordination – Condor Research and Monitoring Coordinator (USFWS or USGS staff scientist) – House in Sacramento regional office, report to Deputy or Assistant Regional Director 4 Establish Recovery Implementation Team – Comprised organizations raising, rearing, releasing, and monitoring condors – Modeled after field working group 4 Establish Science Advisory Team – Small, scientifically focused, advisory group composed largely of independent scientists outside of the condor program – Disband Recovery Team 4 Form a Policy Advisory Team – Comprised of leaders of partner organizations – Includes Coordinator.

Recommendations: Reorganize to better reflect current and future circumstances 4 Establish USFWS Condor Recovery Office – Condor Recovery Coordinator handles basic programmatic coordination – Condor Research and Monitoring Coordinator (USFWS or USGS staff scientist) – House in Sacramento regional office, report to Deputy or Assistant Regional Director 4 Establish Recovery Implementation Team – Comprised organizations raising, rearing, releasing, and monitoring condors – Modeled after field working group 4 Establish Science Advisory Team – Small, scientifically focused, advisory group composed largely of independent scientists outside of the condor program – Disband Recovery Team 4 Form a Policy Advisory Team – Comprised of leaders of partner organizations – Includes Coordinator.

Consider the reading in your groups 4 Is/are your rare species conservation reliant? 4 Is the recovery continuum concept useful for considering what needs to be done to avert extinction of your species? 4 Would a recovery management agreement be useful for your species? With whom?

Consider the reading in your groups 4 Is/are your rare species conservation reliant? 4 Is the recovery continuum concept useful for considering what needs to be done to avert extinction of your species? 4 Would a recovery management agreement be useful for your species? With whom?

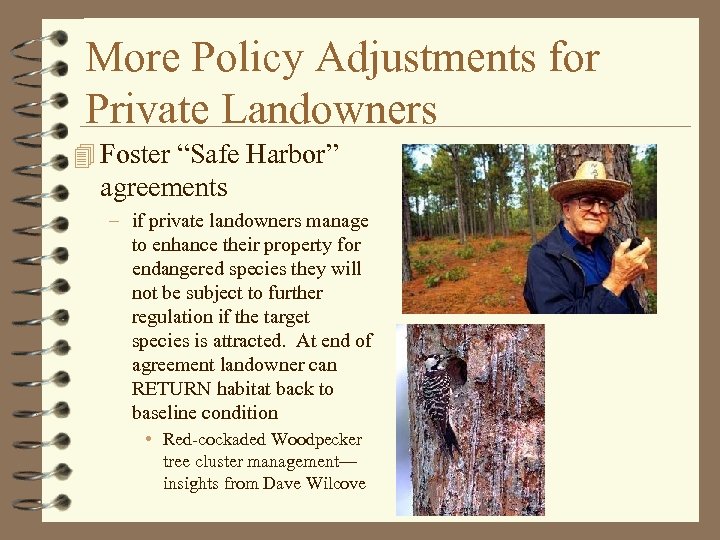

More Policy Adjustments for Private Landowners 4 Foster “Safe Harbor” agreements – if private landowners manage to enhance their property for endangered species they will not be subject to further regulation if the target species is attracted. At end of agreement landowner can RETURN habitat back to baseline condition • Red-cockaded Woodpecker tree cluster management— insights from Dave Wilcove

More Policy Adjustments for Private Landowners 4 Foster “Safe Harbor” agreements – if private landowners manage to enhance their property for endangered species they will not be subject to further regulation if the target species is attracted. At end of agreement landowner can RETURN habitat back to baseline condition • Red-cockaded Woodpecker tree cluster management— insights from Dave Wilcove

Private lands are important. 4 General Accounting Office (1995) – 37% of our endangered species do not occur on any federal lands. 4 Precious Heritage (2001) – 40% of our endangered species do not occur on any federal lands.

Private lands are important. 4 General Accounting Office (1995) – 37% of our endangered species do not occur on any federal lands. 4 Precious Heritage (2001) – 40% of our endangered species do not occur on any federal lands.

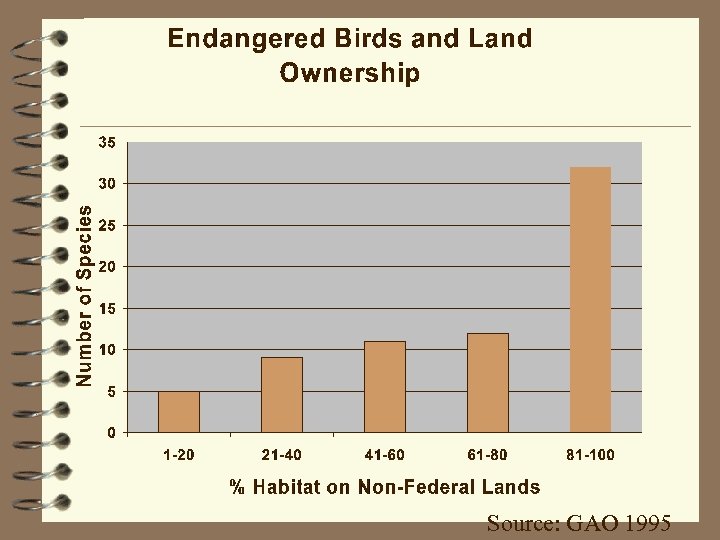

Source: GAO 1995

Source: GAO 1995

Safe Harbor Agreements 4 Voluntary. 4 Enable landowners to restore habitats of endangered species without the risk of new regulations. 4 Do not diminish protection for any endangered species already on the property (“baseline”). 4 Must provide a net benefit to the species.

Safe Harbor Agreements 4 Voluntary. 4 Enable landowners to restore habitats of endangered species without the risk of new regulations. 4 Do not diminish protection for any endangered species already on the property (“baseline”). 4 Must provide a net benefit to the species.

Sandhills Safe Harbor Program 4 April, 1995 and 4 4 continuing 126 landowners in NC alone in 2015 65, 194 acres enrolled woodlots, golf courses, horse farms, residential property 73 woodpecker social groups are protected in the program

Sandhills Safe Harbor Program 4 April, 1995 and 4 4 continuing 126 landowners in NC alone in 2015 65, 194 acres enrolled woodlots, golf courses, horse farms, residential property 73 woodpecker social groups are protected in the program

International Paper’s Woodpecker Bank: Background 4 IP owns > 4 million acres of forest in the south. 4 1999: only 16 groups of woodpeckers on commercial timberland. Little chance they will survive – Some “groups” consist of single birds. 4 2 more groups on IP’s research forest in Bainbridge, GA.

International Paper’s Woodpecker Bank: Background 4 IP owns > 4 million acres of forest in the south. 4 1999: only 16 groups of woodpeckers on commercial timberland. Little chance they will survive – Some “groups” consist of single birds. 4 2 more groups on IP’s research forest in Bainbridge, GA.

IP’s Plan 4 Turn research forest into a woodpecker bank. 4 4 “Southlands Forest” 1999: 1, 500 acres of suitable habitat. IP will increase habitat to > 5, 000 acres. Goal of 25 -30 woodpecker groups. Translocate birds from Ft. Benning to Southlands

IP’s Plan 4 Turn research forest into a woodpecker bank. 4 4 “Southlands Forest” 1999: 1, 500 acres of suitable habitat. IP will increase habitat to > 5, 000 acres. Goal of 25 -30 woodpecker groups. Translocate birds from Ft. Benning to Southlands

What IP Can Do: 4 For each new group it creates at the bank, IP can cut timber around an existing group on its commercial timberland. 4 1: 1 mitigation. 4 No new birds in the bank, no cutting.

What IP Can Do: 4 For each new group it creates at the bank, IP can cut timber around an existing group on its commercial timberland. 4 1: 1 mitigation. 4 No new birds in the bank, no cutting.

How Can IP Make Money? 4 IP has a baseline of 18 groups (2 at research forest/bank, 16 on commercial timberlands). 4 If it creates more than 18 groups at the bank, it can “sell” those additional groups to other parties in search of mitigation.

How Can IP Make Money? 4 IP has a baseline of 18 groups (2 at research forest/bank, 16 on commercial timberlands). 4 If it creates more than 18 groups at the bank, it can “sell” those additional groups to other parties in search of mitigation.

Who Benefits? International Paper • Consolidation of responsibilities. • Potential economic gain from selling credits. Red-cockaded Woodpecker • Larger population in better habitat. • Long-term management of that habitat.

Who Benefits? International Paper • Consolidation of responsibilities. • Potential economic gain from selling credits. Red-cockaded Woodpecker • Larger population in better habitat. • Long-term management of that habitat.

The woodpecker population in the bank has already grown from 2 groups (3 non -breeders) to 15 breeding groups (50 birds and 13 potential breeding pairs) in the first 5 years of the program (2005). In 2008, IP sold US holdings, Southlands bought by State of Georgia

The woodpecker population in the bank has already grown from 2 groups (3 non -breeders) to 15 breeding groups (50 birds and 13 potential breeding pairs) in the first 5 years of the program (2005). In 2008, IP sold US holdings, Southlands bought by State of Georgia

Literature Cited 4 USFWS. 1997. Recovery plan for the threatened Marbled Murrelet in Washington, Oregon, and California. Portland, OR. 203 pp. 4 GAO. 1993. Factors associated with delayed listing decisions. GAO/RCED-93 -152. 4 Sidle, JG. 1998. Arbitrary and capricious species conservation. Conservation Biology 12: 248 -249. 4 Clark, T. W. , Reading, R. P. , and Clark, A. L. (eds. ) 1994. Endangered species recovery: finding the lessons, improving the process. Island Press

Literature Cited 4 USFWS. 1997. Recovery plan for the threatened Marbled Murrelet in Washington, Oregon, and California. Portland, OR. 203 pp. 4 GAO. 1993. Factors associated with delayed listing decisions. GAO/RCED-93 -152. 4 Sidle, JG. 1998. Arbitrary and capricious species conservation. Conservation Biology 12: 248 -249. 4 Clark, T. W. , Reading, R. P. , and Clark, A. L. (eds. ) 1994. Endangered species recovery: finding the lessons, improving the process. Island Press

References 4 Tear, TH et al. 1993. Status and prospects for success of the 4 4 endangered species act: a look at recovery plans. Science 262: 976 -977. Noecker, RJ (1998) Endangered species list revisions: a summary of delisting and downlisting. Congressional Research Service. Library of Congress. Washington DC. General Accounting Office (GAO). 1988. Endanagered Species: Management improvements could enhance recovery program. GAO/RCED-89 -5. Washington DC. General Accounting Office (GAO). 1994. Endangered Species Act: Information on species protection on nonfederal lands. GAO RCED-95 -16. Washington DC. Stein, BA. Kutner, LS, and JS Adams. 2000. Precious Heritage. Oxford University Press.

References 4 Tear, TH et al. 1993. Status and prospects for success of the 4 4 endangered species act: a look at recovery plans. Science 262: 976 -977. Noecker, RJ (1998) Endangered species list revisions: a summary of delisting and downlisting. Congressional Research Service. Library of Congress. Washington DC. General Accounting Office (GAO). 1988. Endanagered Species: Management improvements could enhance recovery program. GAO/RCED-89 -5. Washington DC. General Accounting Office (GAO). 1994. Endangered Species Act: Information on species protection on nonfederal lands. GAO RCED-95 -16. Washington DC. Stein, BA. Kutner, LS, and JS Adams. 2000. Precious Heritage. Oxford University Press.

More References 4 Carroll, R. et al. 1996. Strengthening the use of science in achieving the goals of the endangered species act: an assessment by the ecological society of america. Ecological Applications 6: 1 -11. 4 USFWS and NMFS. 1997. Making the esa work better. Washington DC. 4 Boersma, PD, P. Kareiva, WF Fagan, JA Clark, and JM Hoekstra. 2001. How good are endangered species recovery plans? Bio. Science 51: 643 -649. (see also Bio. Science 52: 212 -214 for further discussion)

More References 4 Carroll, R. et al. 1996. Strengthening the use of science in achieving the goals of the endangered species act: an assessment by the ecological society of america. Ecological Applications 6: 1 -11. 4 USFWS and NMFS. 1997. Making the esa work better. Washington DC. 4 Boersma, PD, P. Kareiva, WF Fagan, JA Clark, and JM Hoekstra. 2001. How good are endangered species recovery plans? Bio. Science 51: 643 -649. (see also Bio. Science 52: 212 -214 for further discussion)

More References 4 Miller, J. K. et al. 2002. The endangered species act: dollars and sense? Bio. Science 52: 163 -168. 4 Taylor, M. F. et al. 2005. The effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act: a quantitative analysis. Bio. Science 55: 360 -367. 4 Scott, J. M. et al. 2005. Recovery of imperiled species under the Endangered Species Act: the need for a new approach. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 3: 383 -389.

More References 4 Miller, J. K. et al. 2002. The endangered species act: dollars and sense? Bio. Science 52: 163 -168. 4 Taylor, M. F. et al. 2005. The effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act: a quantitative analysis. Bio. Science 55: 360 -367. 4 Scott, J. M. et al. 2005. Recovery of imperiled species under the Endangered Species Act: the need for a new approach. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 3: 383 -389.