6d5739396bb341757c2f5a09000776f4.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 68

Introduction to Negotiation Concepts BUSS 5355 Dr Joanna Crossman 1 -1

1 -2

In the event of an emergency: Proceed quickly and quietly to the nearest exit Make your way to the assembly point BH or H building classes – Lion Courtyard RR building classes – Way Lee/George Kingston Courtyard GK building classes – Elton Mayo/Rowland Rees Courtyard Wait for further instructions Do not use the lift in an emergency If YOU identify an emergency or health related incident call security on 88888 1 -3

Objectives of the workshop • To identify different kinds of negotiation • To share some defining and key concepts of negotiation • To highlight stages in the negotiation process 1 -4

Introduction • Everyone negotiates on a daily basis (Samina & Vinta, 2010, p. 26) • Negotiation is a skill, not a profession • Vital personally and for organisations • Negotiating ability is learned through experience and training (Rai 2013). • Sometimes the stakes are high, sometimes not. Buying out a firm v what movie you decide to go to (De Janasz, Crossman, Campbell & Powers, 2014 (forthcoming). 1 -5

Everyday Negotiation • Personal lives; Who makes dinner, who drinks/drives, holiday destinations… • At work; Pay rises, priorities, benefits, mergers etc. • Employees in organisations negotiate vertically & horizontally with colleagues, partners, customers, clients and internal teams (Samina & Vinita, 2010). 1 -6

Quick Discussion Describe to another, any personal, social, professional or academic contexts in which you have recently negotiated. What was it that made you define the activity as a negotiation? What occurred that made you view it as one? 1 -7

Three basic types of negotiation. Was your example one of these? (Carrell & Heavrin, 2008, p. 4) 1. Deal Making Negotiation Eg; purchase/sale house, car, washing machine. 2. Decision Making Negotiation When a mutually beneficial decision is sought. Eg; Negotiating who does what when job sharing. 3. Dispute-Resolution Negotiation when discussions have reached an impasse 1 -8

Note down defining characteristics in the following definitions that strike you. Can you identify any variations in focus? “…a process where interested parties resolve disputes, agree upon causes of action, bargain for individual or collective advantage and or attempt to craft outcomes which serve their mutual interest” (Samina & Vinita, 2010, p. 26). “Negotiation is a social interaction between two (or more) parties who provide arguments in an attempt to influence the other to accept their view regarding the value of a negotiated object” (Maaravi, Ganzach & Pazy, 2011, p. 245). Negotiation is a process in which two or more people or groups share their concerns and interests to reach an agreement of mutual benefit (Fisher, Ury & Patton, 1991). “Business negotiation is the solution to reach an agreement or to solve the disagreement. It is also a process of exchanging, discussing and even arguing about an issue” (Zhang 2013, p. 5056). 1 -9

Common elements of negotiation (Carrell & Heavrin 2008, p. 4; Lewicki et al. 2007) • • More than one party is involved Both parties have shared interests (they are therefore committed to an extent) but there also opposed interests (but they don’t agree on everything) (De Janasz, Crossman, Campbell & Powers, 2014 (forthcoming) ). • • The parties are prepared to be flexible. Participants have the ability and authority to make decisions 1 -10

A negotiating ‘party’ (Thompson 2009, pp. 27 -28) • A party is a person or group with common interests. • Don’t assume people in the same party have the same view - beliefs, values and preferences will vary 1 -11

Negotiation continued…. Parties search for agreement rather than: – fight openly – capitulate – break off contact permanently – take their dispute to a third party Discuss possible benefits of negotiating 1 -12

Benefits of Negotiation • Cheaper than the courts • Parties can work through emotional issues over time and it can clear the air. • It can help to improve relationships when successful • Provides a sense of accomplishment • Reduces stress and frustration possibly the potential for further conflicts (De Janasz, Crossman, Campbell & Powers, 2014, p. 205).

Successful negotiation involves the management of: – Tangibles (e. g. , the price or the terms of agreement) – Intangibles (e. g. , the underlying psychological issues) 1 -14

Positions and Interests • Rooted in basic human needs requiring satisfaction. • E. g. , security, economic well-being, a sense of belonging, recognition, control over one’s life. • It is not an action • An interest is the ‘Why behind the what’ 1 -15

A position is… – about what to do; an action. – a demand or proposal – a preferred course of action I don’t have enough money to pay the rent (interest) so will ask the boss for more hours at work (position). Any more examples? 1 -16

Phases to a Negotiation (Peeling 2008) 1. Preparation 2. The actual negotiation or bargaining 3. Closure and commitment 1 -17

Preparing for Negotiation Eighty per cent of time on preparation, 20% on actual negotiation (Thompson 2009, p. 12). Wachs (2012, p. 255) – “Most important step” in negotiation. 1 -18

Planning your timing (Hynes 2008) • Although people have personal differences, the consensus is that 11 am is when individuals are at peak efficiency and so this is the best time to negotiate. • The best time to seek a pay rise or flexi time would be just after an achievement has come to the attention of your boss. • Elicit action before lunch or at the end of a meeting as people like a sense of accomplishment when they take a break. 1 -19

Consider territory in planning negotiation (Eunson 2007, p. 68) Your place • Familiar, greater control, furniture and who sits where, breaks, access to support personnel, experts, authorisation, resources (to get agreements written up), can do personal work when not at the negotiating table 1 -20

Eunson (2007, p. 68) continued. . . Their place • Can delay pleading necessity to consult • Easier to walk out • Chance to find out about them • Unfamiliar, so higher stress (lower performance) • Higher cost (travel, accommodation) Other place • More neutral 1 -21

For sensitive issues or where creativity is required…. . Port Douglas? • Change the environment, distinguish it from the regular discussions • Provide for an informal atmosphere. A picturesque spot? 1 -22

Discuss Reflect on a negotiation that was important to you. Where was it held? How do you think location played a part in the process and outcome of the negotiation? 1 -23

Preparation continued…. . • Think through the bargaining process • Clarify what you want, the goal or outcome. • Anticipate what the other party needs 1 -24

Eg; if you want to spend more time with family, point out time wasted on travel & petrol expenses to see clients that could be saved if you travel from home directly on some days. 1 -25

Preparation and framing (Peeling 2008) • A frame = context • What are the issues? What’s going on in the organisation of the opposite party? • What do stakeholders want to achieve? • Competitor prices? • Legal and financial implications • Where is the negotiator placed in the organisation? CV? • Who has the authority to make decisions? • Talk over your plans with a mentor 1 -26

Discuss In your recent negotiating experience what did you know about the following prior to the negotiation? Eg; • What influenced the position of the other party? • What did the other party wish to achieve? • Any financial, legal or personal issues involved? • Position of the negotiator in the company? • Did the other party have the power to negotiate? 1 -27

Offers during negotiation (Peeling 2008, p. 5) • Don’t leap into offers and counter offers because despite preparation there will still be things you do not know about the other party. • Deals are rarely struck after the first offer and tend to lead to successive counter-offers until agreement is reached (Maaravi, Ganzach & Pazy 2011, p. 245). 1 -28

Offers continued…. • The first offer is an anchor that affects later offers so the higher the first offer, the higher the counter offer and the higher the settlement price so negotiators sometimes want to make a high offer that is nevertheless reasonable (Maaravi et al. 2011, p. 245). • The first offer if accompanied by a persuasive argument could be effective but only if they could not be easily disputed (Maaravi et al. 2011, p. 245). 1 -29

• Don’t share the target point in detail Eg; the outcome a negotiator wants (Thompson 2009, p. 13) • You can exchange information about your respective frames however and begin to develop a respectful relationship. • Establish deadlines • The cost and benefit will need to be balanced (Peeling 2008). 1 -30

BATNA and WATNA A negotiator’s relative power (Fisher & Ury 1988; Leigh, Wang & Gunia 2009). • BATNA (Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement). If BATNA likely, Don’t bother to negotiate! • Eg; How you negotiate your employment contract depends on other offers of pay and conditions. • WATNA (Worst alternative) seems likely, negotiate! 1 -31

Discuss Reflect upon a recent negotiation. What was your best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA)? What was the worst alternative? (WATNA)? Eg: So if you don’t get what you want, what is your best Plan B? What’s the worst that could happen? 1 -32

Target and resistance points • Target point – the goal of the negotiator • Resistance point- the point a negotiator walks away • The other party will want to discover your target and resistance point and then influence you in their own favour within that range. 1 -33

Mutual adjustments occur as parties seek to influence one another • You are offered a job offshore • You don’t want to go • Your boss knows you are concerned that your kids attend an unsatisfactory school • She offers to throw international private schooling into the package • You revise your position 1 -34

Discuss In a recent negotiation identify any mutual adjustments either party made. How did they affect the progress of the negotiation? 1 -35

Concession Making • A concession is granting something valued to another person without necessarily asking anything in return (Cahn & Abigail, 2007, p. 119). • Distinguishing wants and needs can affect decisions about concessions (Wachs, 2012, p. 255) • Concessions restrict and narrow the range of bargaining options • Research indicates that concessions are more likely to elicit cooperative behaviour (Cahn & Abigail 2007, p. 119). 1 -36

Mutual adjustment and concession making continued…. . • Jessica wants a starting salary of $60 K • She scales her request down to $55 K because she thinks she won’t get $60 k • Before making a concession she must be sure she won’t be offered $60 K+ • If she makes the concession to $55 K she limits all offers above $55 K so the bargaining range is constrained. 1 -37

Differences between negotiators • • Interests Judgments about the future Risk tolerance Time preferences 1 -38

Differences in interests Negotiators seldom value all items in the negotiation equally Eg; An employer may prefer a bonus on sales knowing the cost will only last while an employee works in sales. An employee may prefer a higher starting salary as it would be fixed. Which would you prefer? 1 -39

Differences in judgments about the future Is a run down property in a great area an investment or a potential drain on hard earned money? 1 -40

Differences in risk tolerance A young family with two children is less likely to risk taking on a large loan than double income baby boomers with adult offspring who no longer live at home 1 -41

Differences in time preference A sales person may want to make the sale to receive an end of the month bonus but a buyer may be thinking of upgrading a TV sometime in the next 6 months. 1 -42

Discuss Identify and discuss differences in a recent negotiation in terms of; • Interests • Judgments about the future • risk tolerance • time preferences 1 -43

Distributive/zero sum/instrumental /winlose/position based negotiation Competitive and focused on win/lose outcomes, beating the opposition (Crossman, Bordia & Mills, 2011; Raj 2008, p. 13). The pie metaphor/I get what you don’t get There is only one winner (Lewicki, Barry & Saunders 2007, p. 9). Negotiators demonstrate a strong concern for themselves and little concern for others (Metcalf, Bird, Peterson, Shankarmahesh, Lituchy 2007). 1 -44

Distributive approaches may be characterised by (Kong, Dirks & Ferrin 2014): • • • making extreme offers resistance to sharing information gamesmanship non-reciprocity of concessions exploiting power advantages self-protective behaviours that limit vulnerability 1 -45

Integrative/principled/winwin/interest based negotiation(De Janasz, Crossman, Campbell & Powers, 2014). ‘Getting to Yes’ the seminal text by Fisher, Ury & Patton 1988 basically heralded integrative approaches. 1 -46

IN runs counter to belief that negotiation is a confrontational struggle (Fisher, Ury & Patton, 2011) IN creatively explores options for mutual benefit/gain (Fisher, Ury & Patton, 2011; Kong, Dirks & Ferrin 2014). Eg; Staff want a party in a 5 star hotel, management don’t have sufficient funds so staff agree to pay 10% of the cost per head 1 -47

Integrative Negotiation (IN) focuses on relationships • Transactional negotiation models questioned in favour of approaches that foster long term relationships and collaboration (Koeszegi 2004, p. 640). • IN thus also known as ‘expressive’ negotiation, focusing on emotions and relationships (Hammer & Rogan cited in Royce 2005, p. 7). • Altschul (2007, p. 316) exhorted researchers to consider the “social dynamics of the negotiator’s role”. 1 -48

Integrative negotiation continued. . . • Soft skills are a vital key to achieving a competitive advantage (Raj 2008, p. 8). • Focus on commonalties rather than differences (Lewicki, Barry & Saunders 2007). • Exchange information, interests and ideas in an open, free flowing environment (Kong, Dirks & Ferrin 2014; Lewicki, Barry & Saunders 2007; (Metcalf, Bird, Peterson, Shankarmahesh, Lituchy 2007). • Negotiation requires the development of trust (Ertel 2004, pp. 62 -63). 1 -49

Trust (Kong, Dirks & Ferrin 2014; Lewicki, Barry & Saunders 2007). • Trust is recognised as crucial to negotiation success • Features highly in integrative negotiation • No guarantee trust will lead to collaboration but lack of trust & mistrust can lead to; • Less collaboration • witholding information • being overly cautious 1 -50

Some risks in trusting and collaborative approaches inherent in integrative negotiations because one may share information only to find that the knowledge is exploited by the other party (Kong, Dirks & Ferrin 2014). In long term relationships negotiators are less willing to behave unethically because of the risk of damaging the relationship (Sobral & Islam 2013, p. 290). 1 -51

Mixed approaches are possible Negotiations are rarely purely win-win or winlose situations and may involve a combination of integrative and distributive negotiation strategies (Watkins 1999; Kong et al. 2014). Was your most recent negotiation integrative or distributive or a mixture of both? Explain how you came to this conclusion. 1 -52

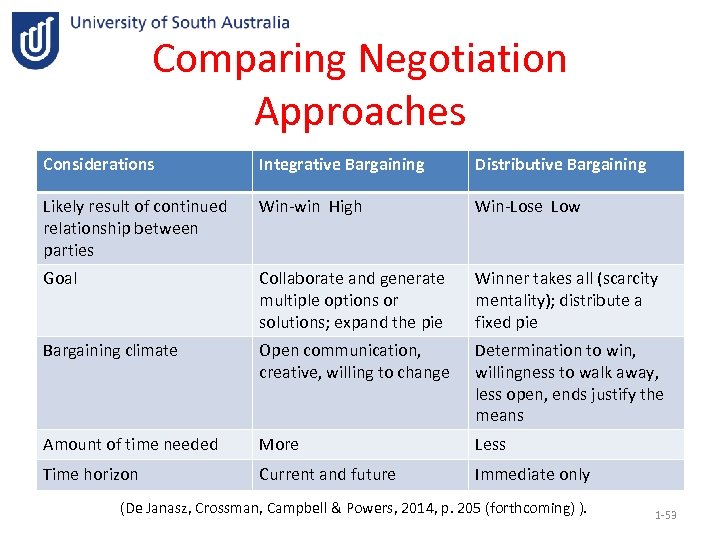

Comparing Negotiation Approaches Considerations Integrative Bargaining Distributive Bargaining Likely result of continued relationship between parties Win-win High Win-Lose Low Goal Collaborate and generate multiple options or solutions; expand the pie Winner takes all (scarcity mentality); distribute a fixed pie Bargaining climate Open communication, creative, willing to change Determination to win, willingness to walk away, less open, ends justify the means Amount of time needed More Less Time horizon Current and future Immediate only (De Janasz, Crossman, Campbell & Powers, 2014, p. 205 (forthcoming) ). 1 -53

Defining features of integrative negotiation • Identify and define the problem/issue • Understand the problem fully – identify interests and needs on both sides • Generate alternative solutions • Evaluate and select among alternatives (Lewicki, Barry & Saunders 2007). 1 -54

1. Identify and define the problem • Define the problem in a way that is mutually acceptable to both sides • What is wrong? What are the disliked facts contrasted with a preferred situation? (Fisher, Ury & Patton 1988, p. 70) • Try not to have any preconceptions about future solutions – keep an open mind • State the problem comprehensively but succinctly and with an eye toward practicality 1 -55

Identify and define the problem continued…. • Be prepared to revise the statement • Take a neutral, non-judgmental approach that does not lay blame or preference for one side over another • “We clearly have different viewpoints on the problem”. • Don’t search for solutions at this stage • Identify any obstacles and consider which can be overcome and which may not (Lewicki, Barry & Saunders 2007). 1 -56

2. Understand the Problem Fully – Identify Interests and Needs Interests: the underlying concerns, needs, desires, or fears that motivate a negotiator – These interests can be intrinsic or instrumental – $90, 000 as a salary may relate to someone’s intrinsic sense of self worth in relation to the marketplace and instrumentally make the purchase of an apartment possible. (Lewicki, Barry & Saunders 2007). 1 -57

Relationship interests indicate that one or both parties value their relationship – Instrumental interests may relate to a party feeling there are benefits in sustaining the relationship. Eg; the other party has contacts in China that you would like to develop in your own business – Intrinsic interests relate to the pleasure of the relationship (Lewicki, Barry & Saunders 2007). 1 -58

3. Generate Alternative Solutions • The creative phase of the negotiation • Brainstorm a list of options/possible solutions • Perhaps ‘expand the pie’ by combining resources or negotiate trade offs 1 -59

Planning for brainstorming Introductions & defining the purpose of brainstorming • Decide group size. Large enough to stimulate interchange, small enough for all to participate (6? ) • Get a good facilitator & someone to record the solutions without comment • Enforce ground rules 1 -60

Brainstorming continued…. . – Be spontaneous but practical – Avoid censoring ideas or being judgmental – Don’t hold up brainstorming by stopping to discuss ideas – Ask outsiders. They can offer ideas and perspectives that have not been explored 1 -61

Brainstorming continued. . . • Diagnose the problem – sort symptoms into categories and suggest causes. Observe what is lacking or blocking the solution (Fisher, Ury & Patton 1988, p. 70). • Brainstorming can be assisted by bringing in other options that cut costs or provide some means of compensation (Cahn & Abigail 2007, p. 125) Eg; We can’t lower the price of the product but we can guarantee delivery in 5 working days so you don’t lose customers • . 1 -62

4. Evaluate and Select Alternatives • Minimize formalising things (eg; record keeping) until final agreements are closed • Evaluate solutions and select the best options • Be prepared to offer a rationale • Develop and agree criteria for accepting solutions in advance. Eg; – How acceptable they are to those who have to implement them – How well they will assist in achieving goals/solving defined problem – Can they be developed in an appropriate time frame? (JC) (Lewicki, Barry & Saunders 2007). 1 -63

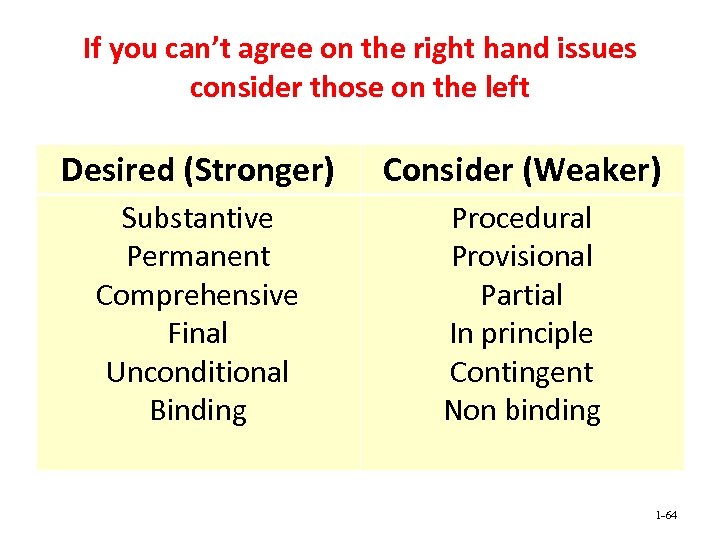

If you can’t agree on the right hand issues consider those on the left Desired (Stronger) Consider (Weaker) Substantive Permanent Comprehensive Final Unconditional Binding Procedural Provisional Partial In principle Contingent Non binding 1 -64

Use objective criteria for deciding • Insist on negotiated price based on market value • What would the replacement cost of a broken item be? • What government standards might guide negotiators? • The more you bring standards of fairness to a problem, the better • Ask questions like; How will we know the 1 -65

References Altschul, C 2007, ‘Internal coordination in complex trade negotiations’, International Negotiation, 2007, 12 (3), pp. 315 -331 Budjac Corvette, B 2007, Conflict Management. A Practical Guide to Developing Negotiation Strategies, Pearson-Prentice Hall, NJ. Cahn, D & Abigail, R 2007 Managing Conflict through Communication, 3 rd edition, Pearson, NT. Carrell, M & Heavrin, C 2008 Negotiating Essentials. Theory, Skills, and Practices. Pearson, Upper saddle River, NJ. Crossman, J, Bordia, S & Mills, C. 2011, Business Communication for the Global Age, Mc. Graw-Hill, Sydney. De Janasz, S. , Crossman, J, Campbell, N. & Powers, M. 2014 (Forthcoming). Chapter 9. ‘Negotiation’, Interpersonal Skills in Organisations (2 nd edn. ), Mc. Graw-Hill, North Ryde, NSW. Ertel, D 2004 ‘Getting past yes. Negotiating as if implementation mattered’, Harvard Business Review, 82(11), pp. 60 -68. 1 -66

Eunson, B 2007, Conflict Management, Wiley, Milton, Qld. Fisher, R, Ury, W & Patton, B 1988, Getting to Yes. Negotiating an Agreement Without Giving in , Century Business, London. Fisher, R. , Ury, W & Patton, B 1991, Getting to Yes: Negotiating without giving in, 2 nd edn, Penguin Books, New York. Fisher, R. , Ury, W. , & Patton, B. , 2011, Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in. Penguin, New York. Galin, A. , Gross, M. & Gosalker, G. 2007, ‘E-negotiation versus face-to-face negotiation. What has changed – if anything? Computers in Human Behaviour, 23, pp. 789 -797. Ghauri, P 1986 ‘International Business negotiations. A turn-key project’, Service Industries Journal, vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 74 -89. Hynes, G 2008 Managerial Communication Strategies and Application, 4 th edn. , Mc. Graw-Hill Irwin, NY. Koeszegi, S 2004 ‘Trust-building strategies in inter-organizational negotiations’, Journal of Managerial Psychology, 19(6), pp. 640 -660. Kong, D. , Dirks, K. & Ferrin, D. 2014, ‘Interpersonal trust within negotiations: Meta-analytic evidence, critical contingencies, and directions for future research’, Academy of Management Journal, vol. 57, No. 5, pp. 1235 -1255. Leigh, T 2008 The Truth About Negotiation, Pearson Education Inc. , Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. Lewicki, R, Barry, B & Saunders, D 2007 Essentials of Negotiation, 4 th edition, Mc. Graw-Hill, Sydney. Maaravi, Y. , Ganzach, Y & Pazy, A 2011, ‘Negotiations as a form of persuasion: Arguments in first offers’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 245 -55. 1 -67

Metcalf, L. , Bird, A, . Peterson, M, Shankarmahesh, M & Lituchy, T. 2007 ‘Cultural influences in negotiations. A four country comparative analysis’ International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, vol. 7(2), 147 -168. Olekalns, M. , Robert, C. , Probust, T. , Smith, Carnevale, P. 2005, ‘the impact of message frame on negotiators’ impressions, emotions, and behaviours’, The International Journal of Conflict Management, 16(4), pp. 379 -402. Peeling, N. , 2008, Brilliant Negotiations. What the Best Negotiators Know, Do and Say, Pearson Prentice Hall, London. Rai, H 2013, ‘The measurement of negotiating ability: Evidence from India’, Global Journal of Business research, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 109 -125. Raj, R. 2008 ‘Business negotiations: A ‘soft’ perspective’, ICFAI Journal of Soft Skills, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 7 -22. Royce, T 2005 Case Analysis. The Negotiator and the bomber: analysing the critical role of active listening in crisis negotiations, Negotiation Journal, January pp. 5 -27. Samina, A & Vinita, M 2010, ‘The art of negotiating’, Advances in Management’, vol. 3, no. 9, pp. 26 -30. Sobral, F. & Islam, G. 2013, ‘Ethically questionable negotiating: The integrative effects of trust, competitiveness, and situation favourability on ethical decision making’, Journal of Business Ethics, 117, pp. 281 -296. Swaab, R, Kern, M. , Diermeier, D & Medvec, V. 2009, ‘Who says what to whom? The impact of communication setting and channel on exclusion from multiparty negotiation agreements’, Social Cognition, vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 385 -401. Thompson, L. , Wang, J. & Gunia, B. 2010, “Negotiation” Annual Review of Psychology, 61, pp. 491 -515. Thompson L 2009 The mind and heart of the negotiator, 4 th edn. , Pearson International, NJ. Wachs, P. , 2012, ‘Negotiation without confrontation’, Workplace health & Safety, vol. 60, No. 6, pp. 255 -256. Watkins, M 1999, ‘Negotiating in a complex world’, Negotiation Journal, vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 245 -270. Zhang, Y. 2013, ‘The politeness principles in business negotiation’, Cross-Cultural communication, vol. 9, No. 4, pp. 50 -56. 1 -68

6d5739396bb341757c2f5a09000776f4.ppt