26e2f9f2742f31ca39e63f00a8933aea.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 109

Introduction to Map and Compass SHSM Certificate

Introduction to Map and Compass SHSM Certificate

Introduction to Map and Compass This tutorial consists of four parts. The objective is to provide you with a basic understanding of the map and compass as used for navigation on land. There is a short quiz at the end of each part. Part 1: Part 2: Part 3: Part 4: Globe to Map – Round to Flat Topographic Maps The Magnetic Compass Navigation

Introduction to Map and Compass This tutorial consists of four parts. The objective is to provide you with a basic understanding of the map and compass as used for navigation on land. There is a short quiz at the end of each part. Part 1: Part 2: Part 3: Part 4: Globe to Map – Round to Flat Topographic Maps The Magnetic Compass Navigation

Introduction to Map and Compass Part 1: Globe to Map – Round to Flat

Introduction to Map and Compass Part 1: Globe to Map – Round to Flat

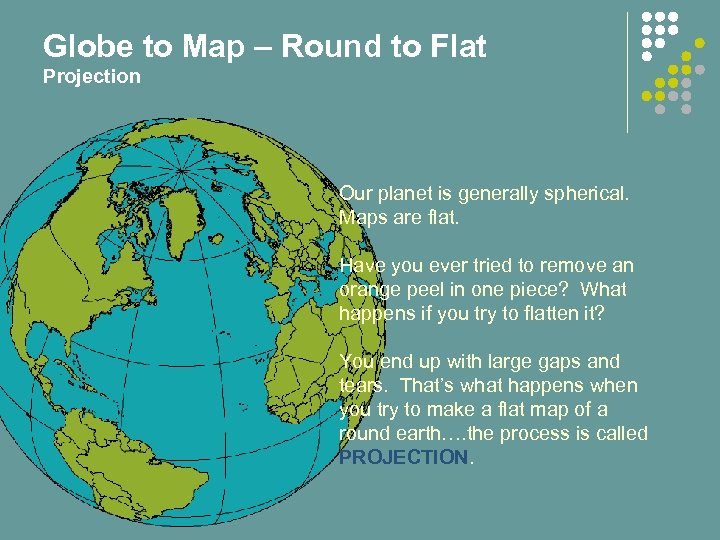

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection Our planet is generally spherical. Maps are flat. Have you ever tried to remove an orange peel in one piece? What happens if you try to flatten it? You end up with large gaps and tears. That’s what happens when you try to make a flat map of a round earth…. the process is called PROJECTION.

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection Our planet is generally spherical. Maps are flat. Have you ever tried to remove an orange peel in one piece? What happens if you try to flatten it? You end up with large gaps and tears. That’s what happens when you try to make a flat map of a round earth…. the process is called PROJECTION.

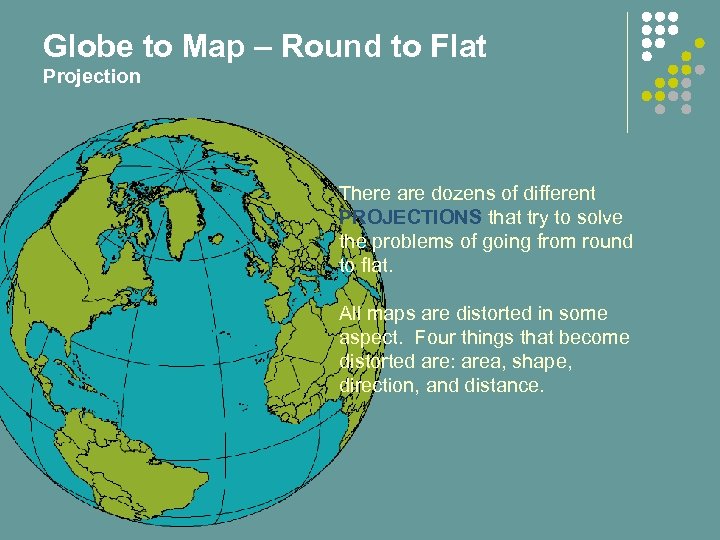

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection There are dozens of different PROJECTIONS that try to solve the problems of going from round to flat. All maps are distorted in some aspect. Four things that become distorted are: area, shape, direction, and distance.

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection There are dozens of different PROJECTIONS that try to solve the problems of going from round to flat. All maps are distorted in some aspect. Four things that become distorted are: area, shape, direction, and distance.

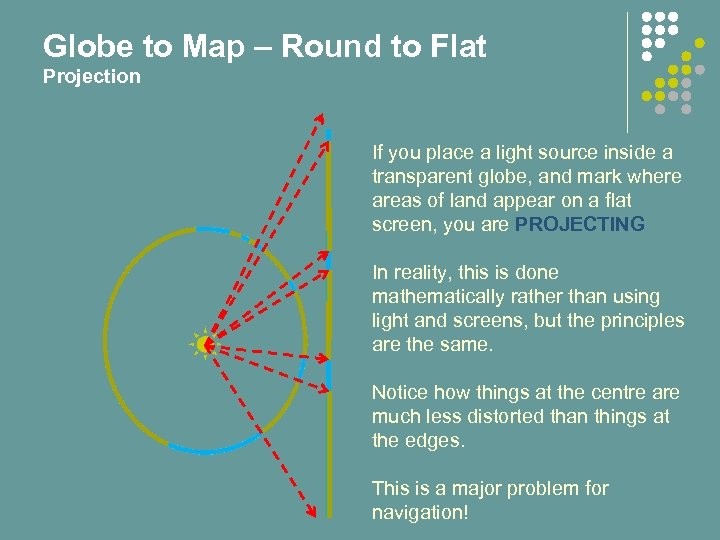

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection If you place a light source inside a transparent globe, and mark where areas of land appear on a flat screen, you are PROJECTING In reality, this is done mathematically rather than using light and screens, but the principles are the same. Notice how things at the centre are much less distorted than things at the edges. This is a major problem for navigation!

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection If you place a light source inside a transparent globe, and mark where areas of land appear on a flat screen, you are PROJECTING In reality, this is done mathematically rather than using light and screens, but the principles are the same. Notice how things at the centre are much less distorted than things at the edges. This is a major problem for navigation!

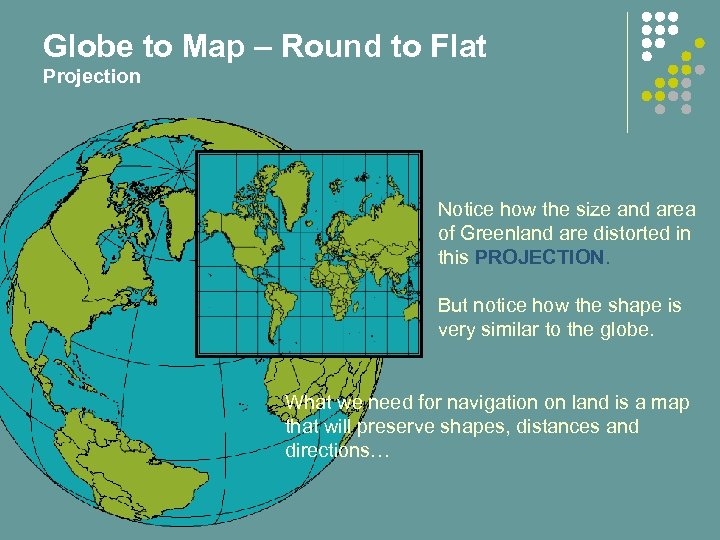

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection Notice how the size and area of Greenland are distorted in this PROJECTION. But notice how the shape is very similar to the globe. What we need for navigation on land is a map that will preserve shapes, distances and directions…

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection Notice how the size and area of Greenland are distorted in this PROJECTION. But notice how the shape is very similar to the globe. What we need for navigation on land is a map that will preserve shapes, distances and directions…

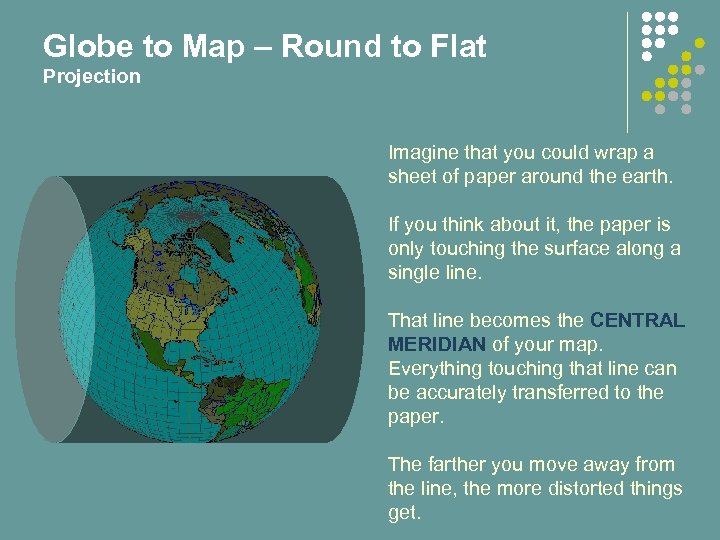

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection Imagine that you could wrap a sheet of paper around the earth. If you think about it, the paper is only touching the surface along a single line. That line becomes the CENTRAL MERIDIAN of your map. Everything touching that line can be accurately transferred to the paper. The farther you move away from the line, the more distorted things get.

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection Imagine that you could wrap a sheet of paper around the earth. If you think about it, the paper is only touching the surface along a single line. That line becomes the CENTRAL MERIDIAN of your map. Everything touching that line can be accurately transferred to the paper. The farther you move away from the line, the more distorted things get.

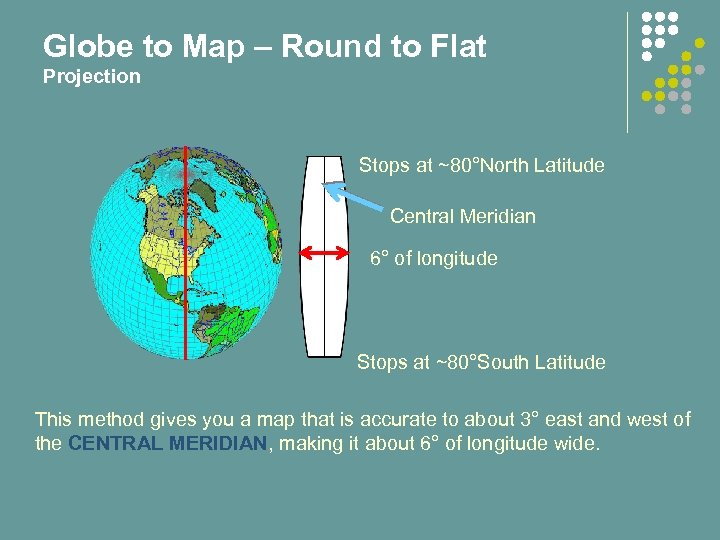

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection Stops at ~80°North Latitude Central Meridian 6° of longitude Stops at ~80°South Latitude This method gives you a map that is accurate to about 3° east and west of the CENTRAL MERIDIAN, making it about 6° of longitude wide.

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection Stops at ~80°North Latitude Central Meridian 6° of longitude Stops at ~80°South Latitude This method gives you a map that is accurate to about 3° east and west of the CENTRAL MERIDIAN, making it about 6° of longitude wide.

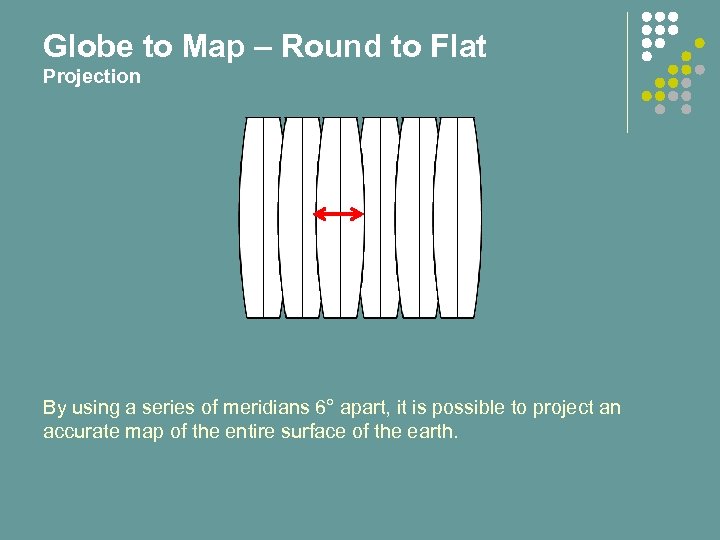

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection By using a series of meridians 6° apart, it is possible to project an accurate map of the entire surface of the earth.

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection By using a series of meridians 6° apart, it is possible to project an accurate map of the entire surface of the earth.

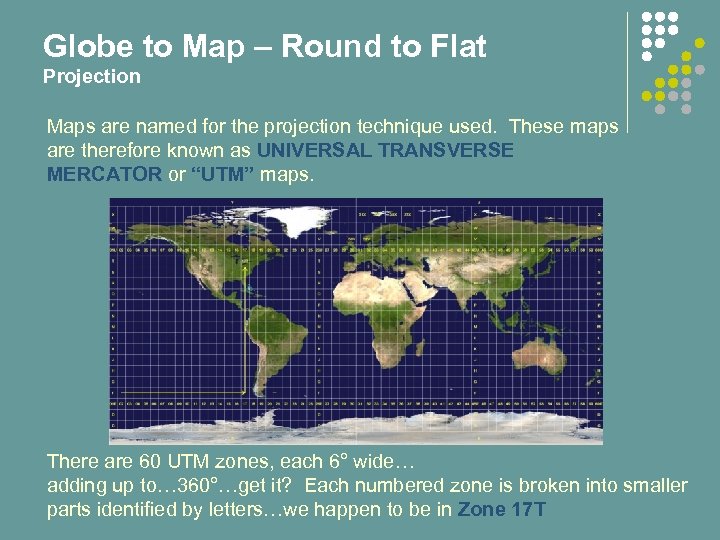

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection Maps are named for the projection technique used. These maps are therefore known as UNIVERSAL TRANSVERSE MERCATOR or “UTM” maps. There are 60 UTM zones, each 6° wide… adding up to… 360°…get it? Each numbered zone is broken into smaller parts identified by letters…we happen to be in Zone 17 T

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection Maps are named for the projection technique used. These maps are therefore known as UNIVERSAL TRANSVERSE MERCATOR or “UTM” maps. There are 60 UTM zones, each 6° wide… adding up to… 360°…get it? Each numbered zone is broken into smaller parts identified by letters…we happen to be in Zone 17 T

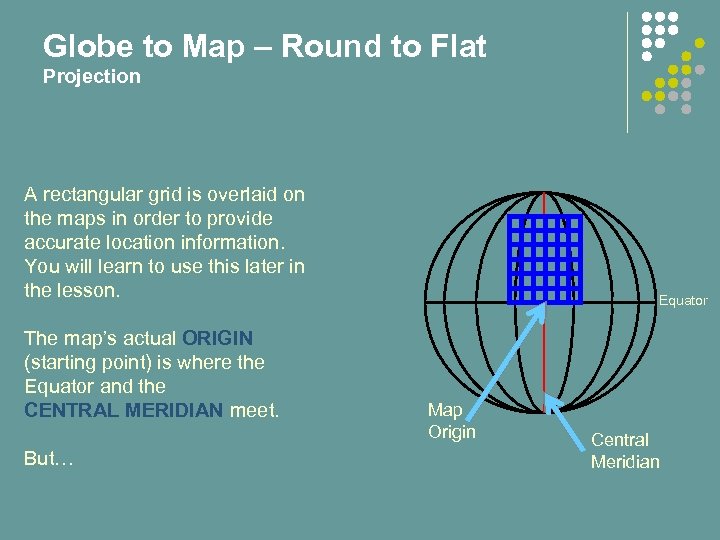

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection A rectangular grid is overlaid on the maps in order to provide accurate location information. You will learn to use this later in the lesson. The map’s actual ORIGIN (starting point) is where the Equator and the CENTRAL MERIDIAN meet. But… Map Origin Equator Central Meridian

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection A rectangular grid is overlaid on the maps in order to provide accurate location information. You will learn to use this later in the lesson. The map’s actual ORIGIN (starting point) is where the Equator and the CENTRAL MERIDIAN meet. But… Map Origin Equator Central Meridian

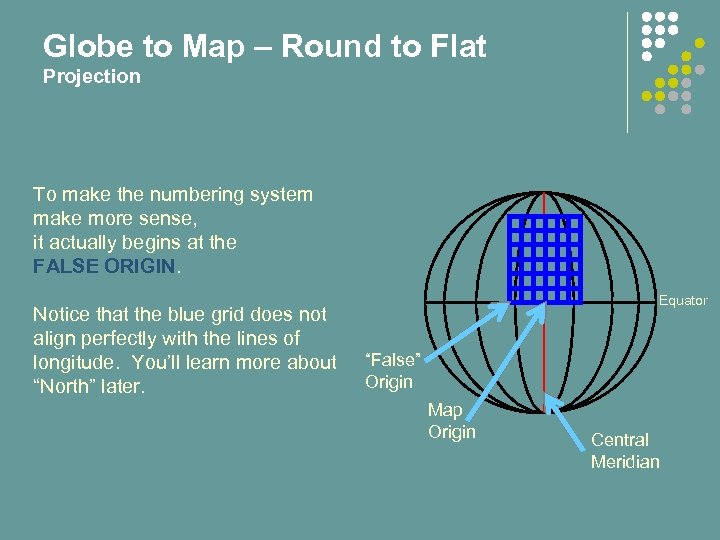

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection To make the numbering system make more sense, it actually begins at the FALSE ORIGIN. Notice that the blue grid does not align perfectly with the lines of longitude. You’ll learn more about “North” later. Equator “False” Origin Map Origin Central Meridian

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Projection To make the numbering system make more sense, it actually begins at the FALSE ORIGIN. Notice that the blue grid does not align perfectly with the lines of longitude. You’ll learn more about “North” later. Equator “False” Origin Map Origin Central Meridian

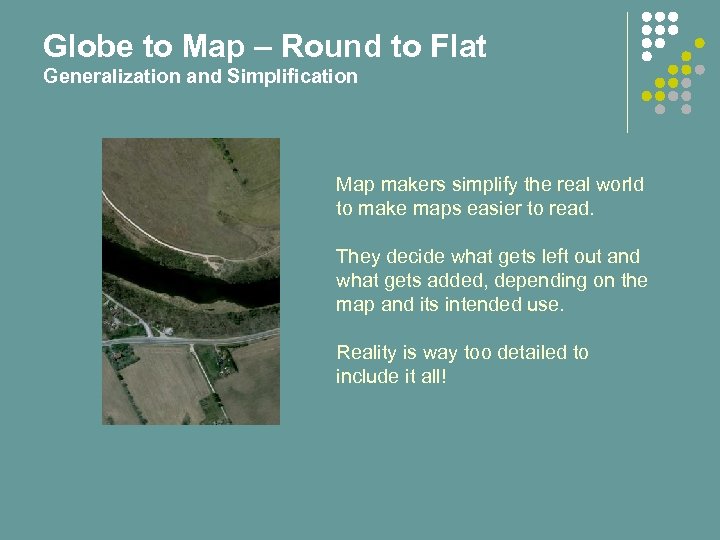

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Generalization and Simplification Map makers simplify the real world to make maps easier to read. They decide what gets left out and what gets added, depending on the map and its intended use. Reality is way too detailed to include it all!

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Generalization and Simplification Map makers simplify the real world to make maps easier to read. They decide what gets left out and what gets added, depending on the map and its intended use. Reality is way too detailed to include it all!

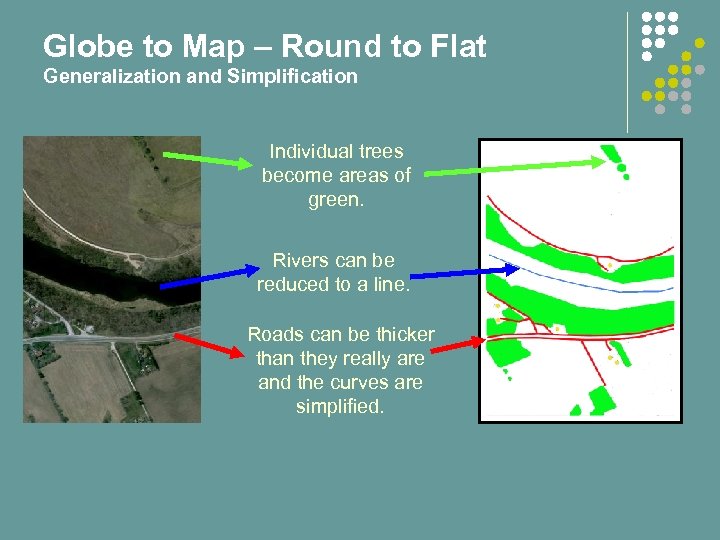

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Generalization and Simplification Individual trees become areas of green. Rivers can be reduced to a line. Roads can be thicker than they really are and the curves are simplified.

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Generalization and Simplification Individual trees become areas of green. Rivers can be reduced to a line. Roads can be thicker than they really are and the curves are simplified.

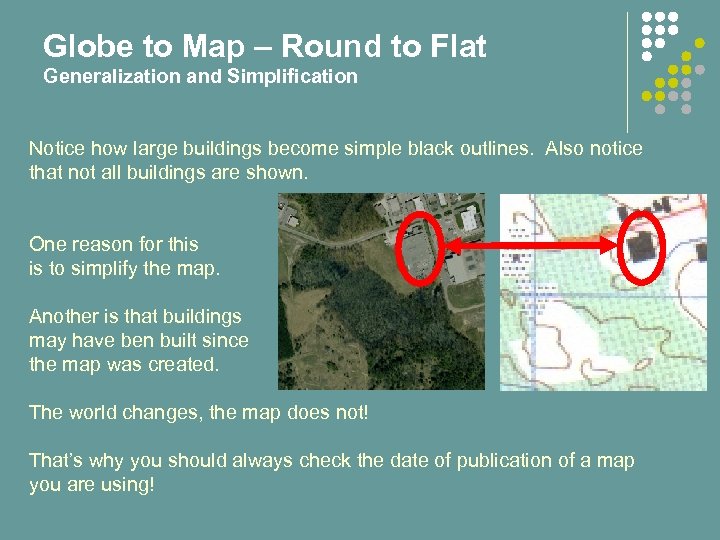

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Generalization and Simplification Notice how large buildings become simple black outlines. Also notice that not all buildings are shown. One reason for this is to simplify the map. Another is that buildings may have ben built since the map was created. The world changes, the map does not! That’s why you should always check the date of publication of a map you are using!

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Generalization and Simplification Notice how large buildings become simple black outlines. Also notice that not all buildings are shown. One reason for this is to simplify the map. Another is that buildings may have ben built since the map was created. The world changes, the map does not! That’s why you should always check the date of publication of a map you are using!

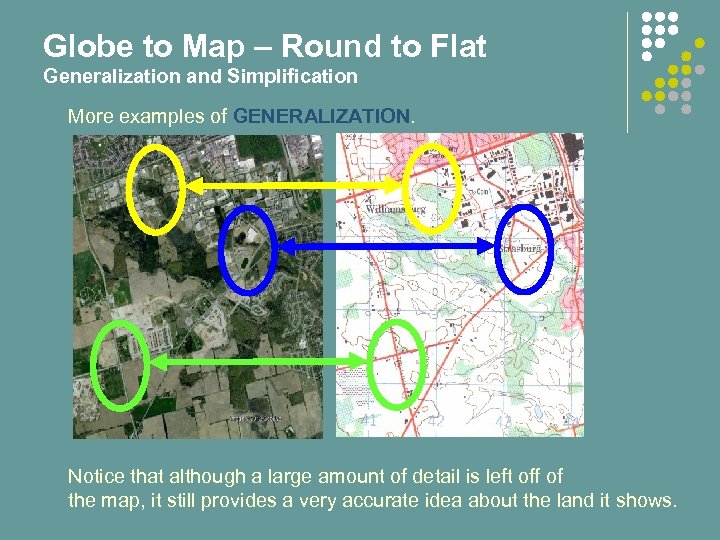

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Generalization and Simplification More examples of GENERALIZATION. Notice that although a large amount of detail is left off of the map, it still provides a very accurate idea about the land it shows.

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Generalization and Simplification More examples of GENERALIZATION. Notice that although a large amount of detail is left off of the map, it still provides a very accurate idea about the land it shows.

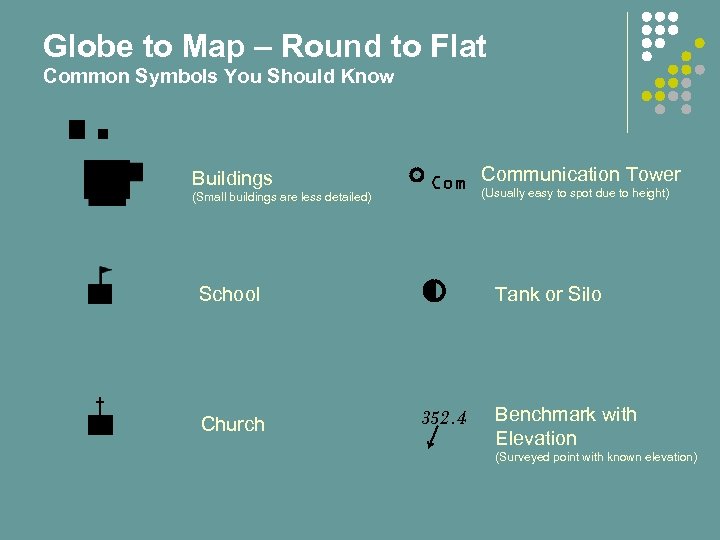

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Common Symbols You Should Know Buildings (Small buildings are less detailed) Communication Tower (Usually easy to spot due to height) School Church Tank or Silo 352. 4 Benchmark with Elevation (Surveyed point with known elevation)

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Common Symbols You Should Know Buildings (Small buildings are less detailed) Communication Tower (Usually easy to spot due to height) School Church Tank or Silo 352. 4 Benchmark with Elevation (Surveyed point with known elevation)

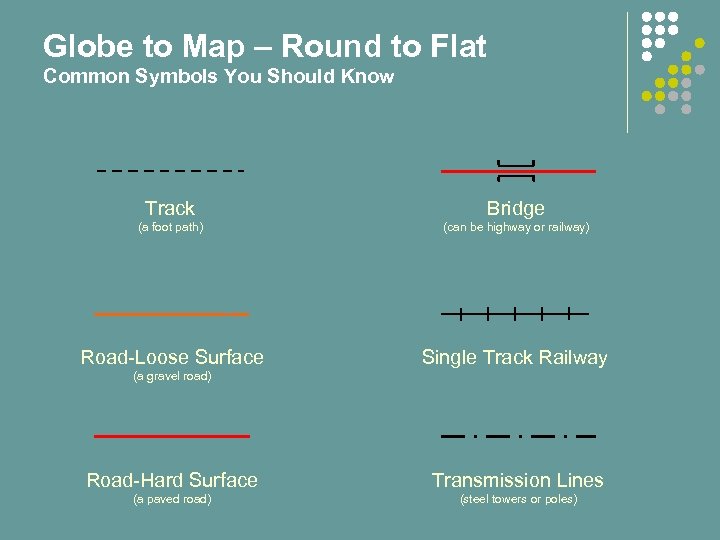

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Common Symbols You Should Know Track Bridge (a foot path) (can be highway or railway) Road-Loose Surface Single Track Railway (a gravel road) Road-Hard Surface Transmission Lines (a paved road) (steel towers or poles)

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Common Symbols You Should Know Track Bridge (a foot path) (can be highway or railway) Road-Loose Surface Single Track Railway (a gravel road) Road-Hard Surface Transmission Lines (a paved road) (steel towers or poles)

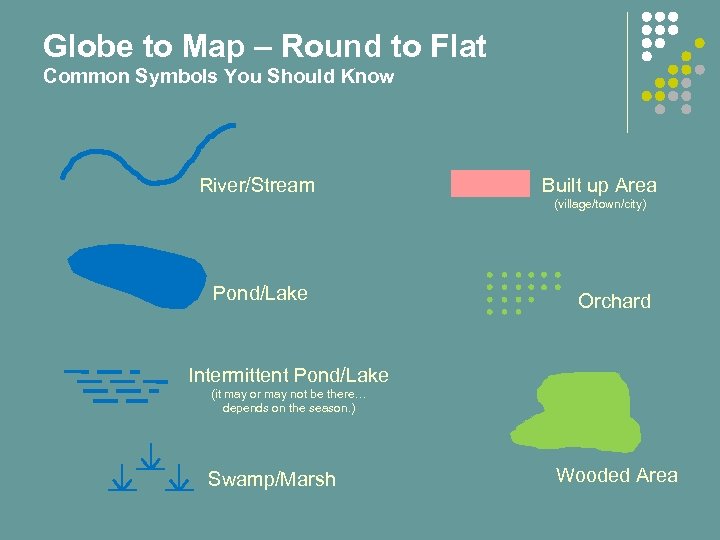

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Common Symbols You Should Know River/Stream Built up Area (village/town/city) Pond/Lake Orchard Intermittent Pond/Lake (it may or may not be there… depends on the season. ) Swamp/Marsh Wooded Area

Globe to Map – Round to Flat Common Symbols You Should Know River/Stream Built up Area (village/town/city) Pond/Lake Orchard Intermittent Pond/Lake (it may or may not be there… depends on the season. ) Swamp/Marsh Wooded Area

Introduction to Map and Compass End of Part 1 Do QUIZ 1 now.

Introduction to Map and Compass End of Part 1 Do QUIZ 1 now.

Introduction to Map and Compass Part 2: Topographic Maps

Introduction to Map and Compass Part 2: Topographic Maps

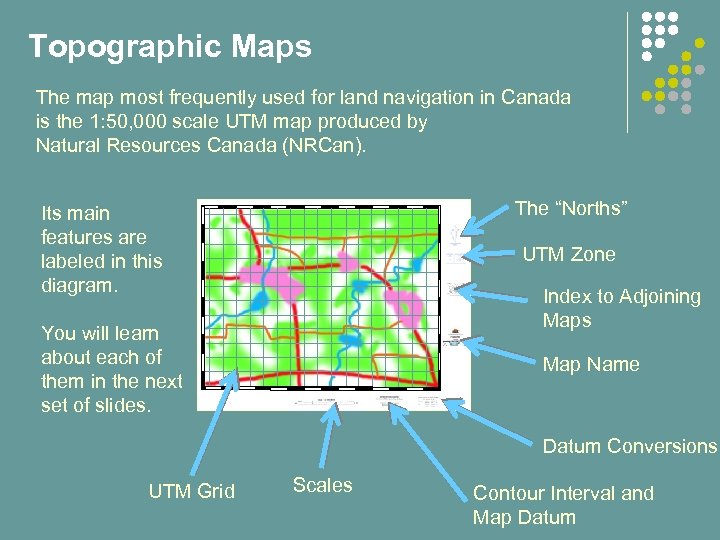

Topographic Maps The map most frequently used for land navigation in Canada is the 1: 50, 000 scale UTM map produced by Natural Resources Canada (NRCan). The “Norths” Its main features are labeled in this diagram. UTM Zone Index to Adjoining Maps You will learn about each of them in the next set of slides. Map Name Datum Conversions UTM Grid Scales Contour Interval and Map Datum

Topographic Maps The map most frequently used for land navigation in Canada is the 1: 50, 000 scale UTM map produced by Natural Resources Canada (NRCan). The “Norths” Its main features are labeled in this diagram. UTM Zone Index to Adjoining Maps You will learn about each of them in the next set of slides. Map Name Datum Conversions UTM Grid Scales Contour Interval and Map Datum

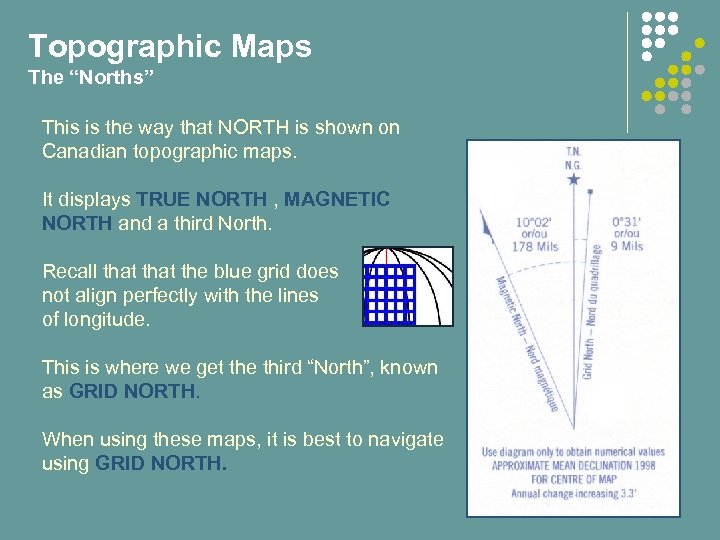

Topographic Maps The “Norths” This is the way that NORTH is shown on Canadian topographic maps. It displays TRUE NORTH , MAGNETIC NORTH and a third North. Recall that the blue grid does not align perfectly with the lines of longitude. This is where we get the third “North”, known as GRID NORTH. When using these maps, it is best to navigate using GRID NORTH.

Topographic Maps The “Norths” This is the way that NORTH is shown on Canadian topographic maps. It displays TRUE NORTH , MAGNETIC NORTH and a third North. Recall that the blue grid does not align perfectly with the lines of longitude. This is where we get the third “North”, known as GRID NORTH. When using these maps, it is best to navigate using GRID NORTH.

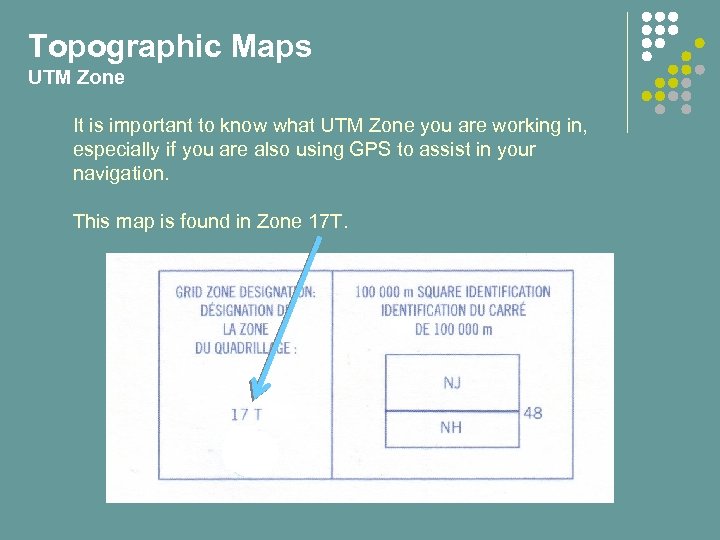

Topographic Maps UTM Zone It is important to know what UTM Zone you are working in, especially if you are also using GPS to assist in your navigation. This map is found in Zone 17 T.

Topographic Maps UTM Zone It is important to know what UTM Zone you are working in, especially if you are also using GPS to assist in your navigation. This map is found in Zone 17 T.

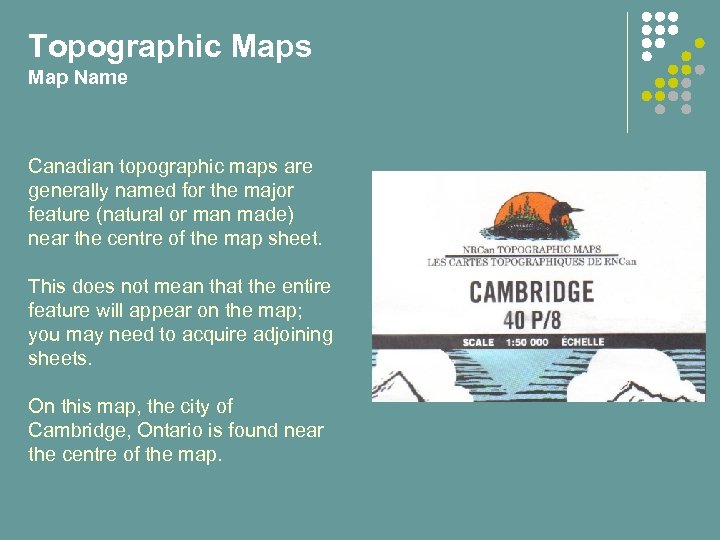

Topographic Maps Map Name Canadian topographic maps are generally named for the major feature (natural or man made) near the centre of the map sheet. This does not mean that the entire feature will appear on the map; you may need to acquire adjoining sheets. On this map, the city of Cambridge, Ontario is found near the centre of the map.

Topographic Maps Map Name Canadian topographic maps are generally named for the major feature (natural or man made) near the centre of the map sheet. This does not mean that the entire feature will appear on the map; you may need to acquire adjoining sheets. On this map, the city of Cambridge, Ontario is found near the centre of the map.

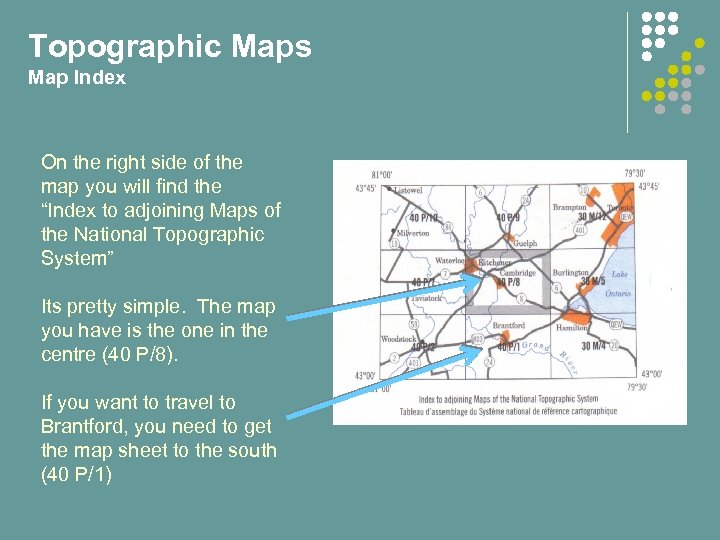

Topographic Maps Map Index On the right side of the map you will find the “Index to adjoining Maps of the National Topographic System” Its pretty simple. The map you have is the one in the centre (40 P/8). If you want to travel to Brantford, you need to get the map sheet to the south (40 P/1)

Topographic Maps Map Index On the right side of the map you will find the “Index to adjoining Maps of the National Topographic System” Its pretty simple. The map you have is the one in the centre (40 P/8). If you want to travel to Brantford, you need to get the map sheet to the south (40 P/1)

Topographic Maps Map Datum Contrary to what you may have been taught, the earth is not a sphere. Its actually more pear shaped…and its lumpy. Actual shape of earth

Topographic Maps Map Datum Contrary to what you may have been taught, the earth is not a sphere. Its actually more pear shaped…and its lumpy. Actual shape of earth

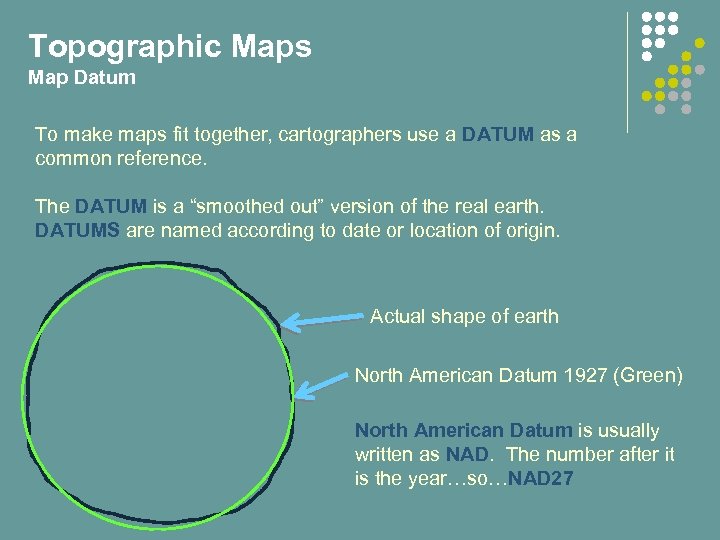

Topographic Maps Map Datum To make maps fit together, cartographers use a DATUM as a common reference. The DATUM is a “smoothed out” version of the real earth. DATUMS are named according to date or location of origin. Actual shape of earth North American Datum 1927 (Green) North American Datum is usually written as NAD. The number after it is the year…so…NAD 27

Topographic Maps Map Datum To make maps fit together, cartographers use a DATUM as a common reference. The DATUM is a “smoothed out” version of the real earth. DATUMS are named according to date or location of origin. Actual shape of earth North American Datum 1927 (Green) North American Datum is usually written as NAD. The number after it is the year…so…NAD 27

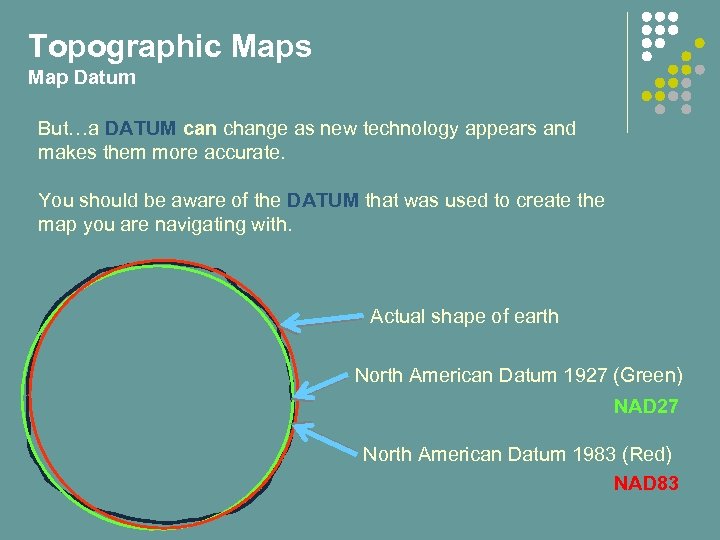

Topographic Maps Map Datum But…a DATUM can change as new technology appears and makes them more accurate. You should be aware of the DATUM that was used to create the map you are navigating with. Actual shape of earth North American Datum 1927 (Green) NAD 27 North American Datum 1983 (Red) NAD 83

Topographic Maps Map Datum But…a DATUM can change as new technology appears and makes them more accurate. You should be aware of the DATUM that was used to create the map you are navigating with. Actual shape of earth North American Datum 1927 (Green) NAD 27 North American Datum 1983 (Red) NAD 83

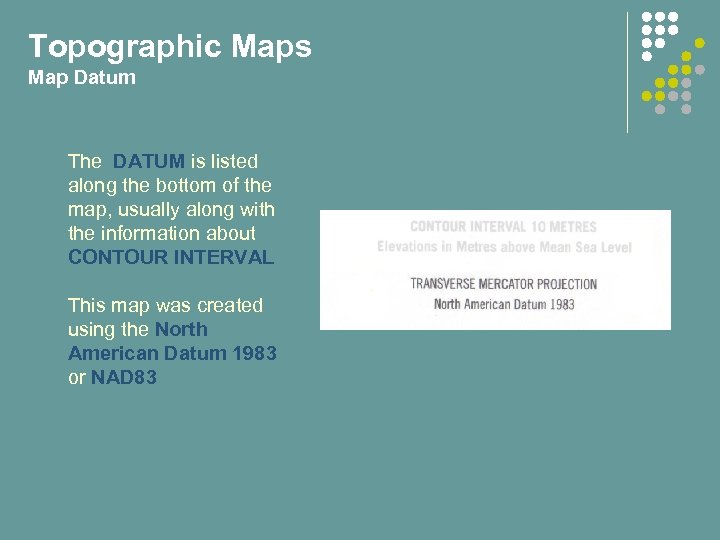

Topographic Maps Map Datum The DATUM is listed along the bottom of the map, usually along with the information about CONTOUR INTERVAL This map was created using the North American Datum 1983 or NAD 83

Topographic Maps Map Datum The DATUM is listed along the bottom of the map, usually along with the information about CONTOUR INTERVAL This map was created using the North American Datum 1983 or NAD 83

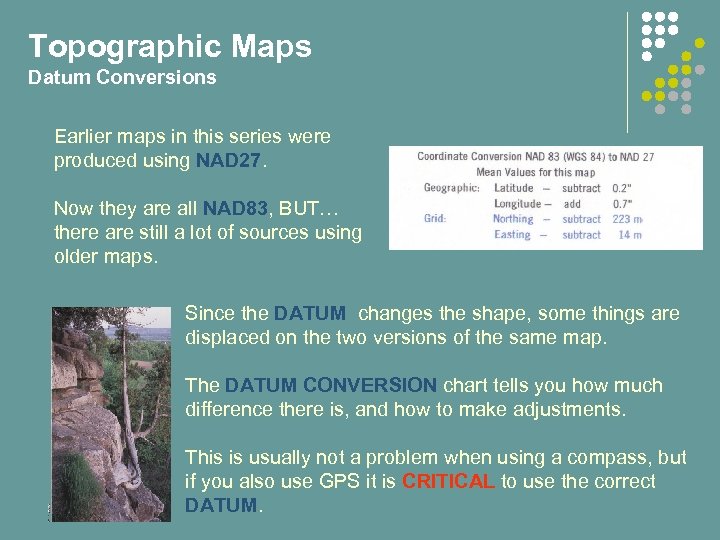

Topographic Maps Datum Conversions Earlier maps in this series were produced using NAD 27. Now they are all NAD 83, BUT… there are still a lot of sources using older maps. Since the DATUM changes the shape, some things are displaced on the two versions of the same map. The DATUM CONVERSION chart tells you how much difference there is, and how to make adjustments. This is usually not a problem when using a compass, but if you also use GPS it is CRITICAL to use the correct DATUM.

Topographic Maps Datum Conversions Earlier maps in this series were produced using NAD 27. Now they are all NAD 83, BUT… there are still a lot of sources using older maps. Since the DATUM changes the shape, some things are displaced on the two versions of the same map. The DATUM CONVERSION chart tells you how much difference there is, and how to make adjustments. This is usually not a problem when using a compass, but if you also use GPS it is CRITICAL to use the correct DATUM.

Topographic Maps Contours One of the most valuable aspects of the TOPOGRAPHIC MAP is its ability to convey information about the shape of the land. It shows the shape by using CONTOURS You may recall from Grade 9 Geography that a CONTOUR is a line that joins points with the same elevation. If you walk ALONG a CONTOUR LINE you stay at the same elevation. If you walk ACROSS a CONTOUR LINE you either go up or down. In the next few slides you will learn to tell the difference!

Topographic Maps Contours One of the most valuable aspects of the TOPOGRAPHIC MAP is its ability to convey information about the shape of the land. It shows the shape by using CONTOURS You may recall from Grade 9 Geography that a CONTOUR is a line that joins points with the same elevation. If you walk ALONG a CONTOUR LINE you stay at the same elevation. If you walk ACROSS a CONTOUR LINE you either go up or down. In the next few slides you will learn to tell the difference!

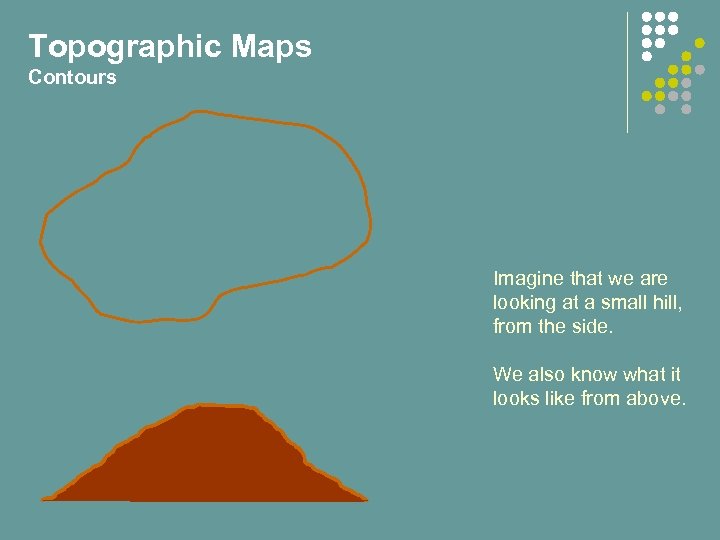

Topographic Maps Contours Imagine that we are looking at a small hill, from the side. We also know what it looks like from above.

Topographic Maps Contours Imagine that we are looking at a small hill, from the side. We also know what it looks like from above.

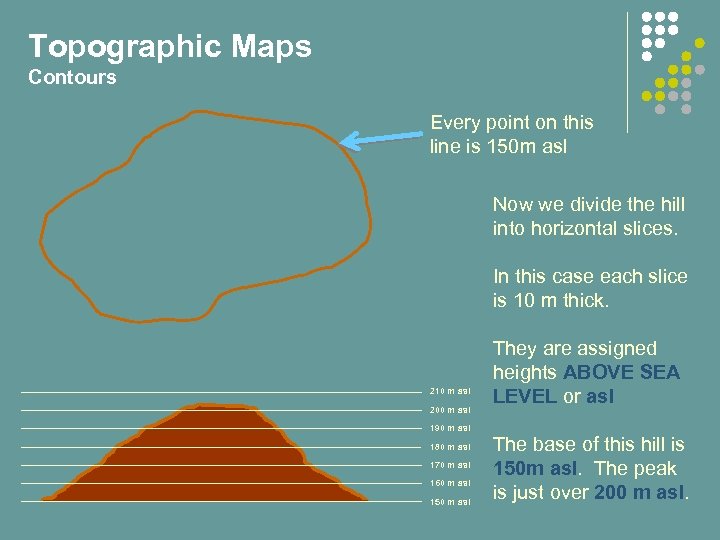

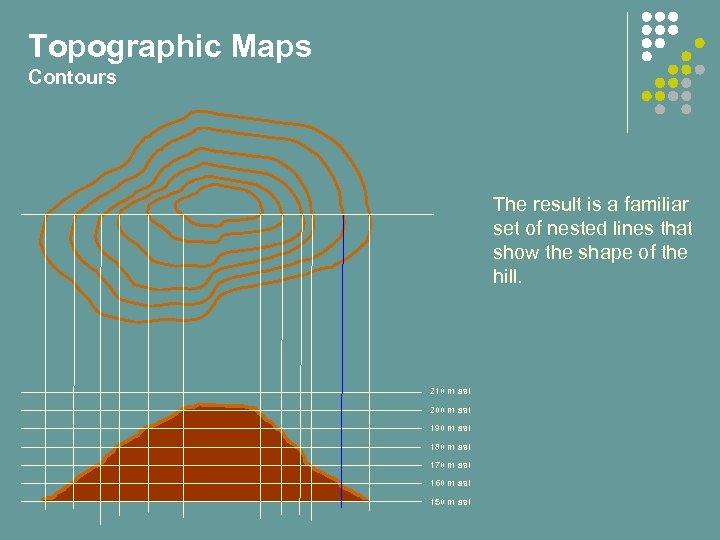

Topographic Maps Contours Every point on this line is 150 m asl Now we divide the hill into horizontal slices. In this case each slice is 10 m thick. 210 m asl 200 m asl 190 m asl 180 m asl 170 m asl 160 m asl 150 m asl They are assigned heights ABOVE SEA LEVEL or asl The base of this hill is 150 m asl. The peak is just over 200 m asl.

Topographic Maps Contours Every point on this line is 150 m asl Now we divide the hill into horizontal slices. In this case each slice is 10 m thick. 210 m asl 200 m asl 190 m asl 180 m asl 170 m asl 160 m asl 150 m asl They are assigned heights ABOVE SEA LEVEL or asl The base of this hill is 150 m asl. The peak is just over 200 m asl.

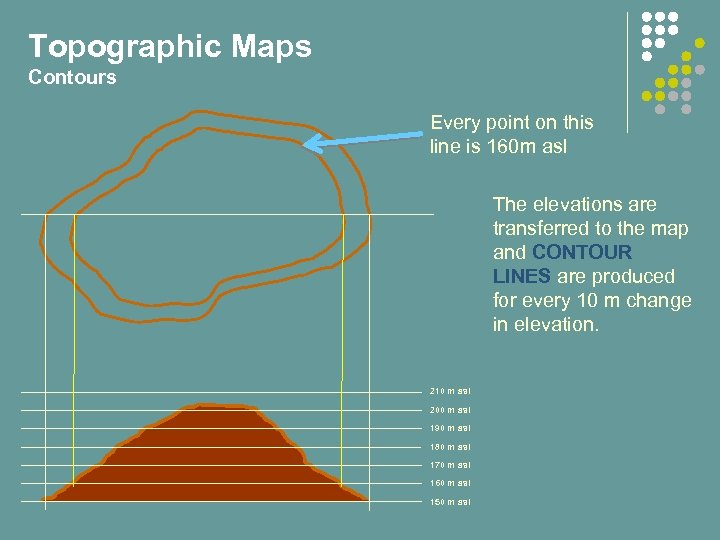

Topographic Maps Contours Every point on this line is 160 m asl The elevations are transferred to the map and CONTOUR LINES are produced for every 10 m change in elevation. 210 m asl 200 m asl 190 m asl 180 m asl 170 m asl 160 m asl 150 m asl

Topographic Maps Contours Every point on this line is 160 m asl The elevations are transferred to the map and CONTOUR LINES are produced for every 10 m change in elevation. 210 m asl 200 m asl 190 m asl 180 m asl 170 m asl 160 m asl 150 m asl

Topographic Maps Contours The result is a familiar set of nested lines that show the shape of the hill. 210 m asl 200 m asl 190 m asl 180 m asl 170 m asl 160 m asl 150 m asl

Topographic Maps Contours The result is a familiar set of nested lines that show the shape of the hill. 210 m asl 200 m asl 190 m asl 180 m asl 170 m asl 160 m asl 150 m asl

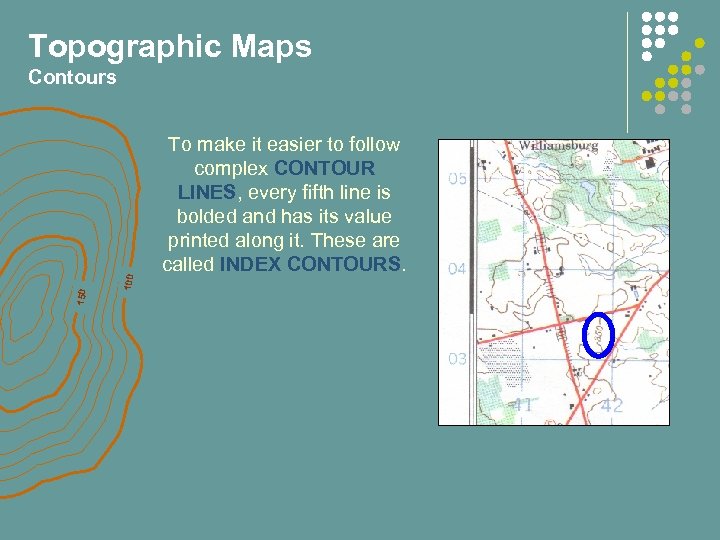

Topographic Maps 100 150 Contours To make it easier to follow complex CONTOUR LINES, every fifth line is bolded and has its value printed along it. These are called INDEX CONTOURS.

Topographic Maps 100 150 Contours To make it easier to follow complex CONTOUR LINES, every fifth line is bolded and has its value printed along it. These are called INDEX CONTOURS.

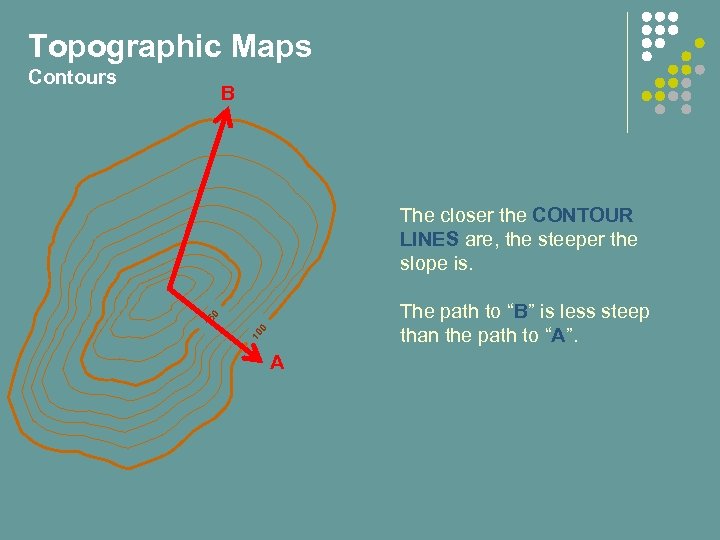

Topographic Maps Contours B The closer the CONTOUR LINES are, the steeper the slope is. 10 0 15 0 The path to “B” is less steep than the path to “A”. A

Topographic Maps Contours B The closer the CONTOUR LINES are, the steeper the slope is. 10 0 15 0 The path to “B” is less steep than the path to “A”. A

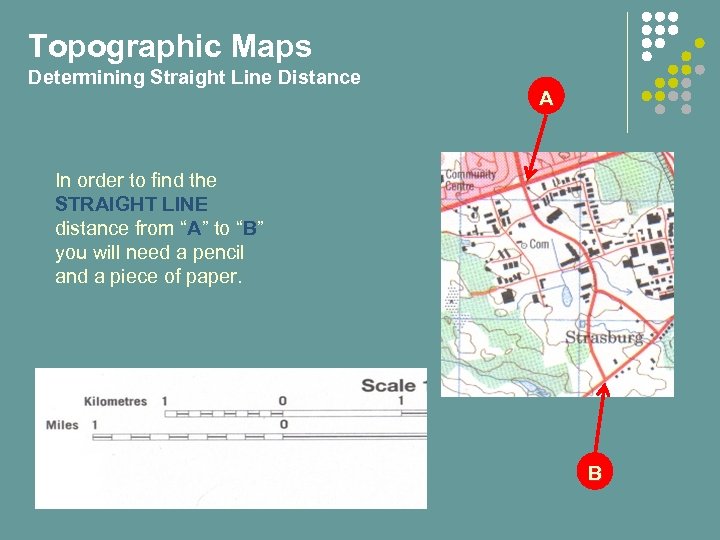

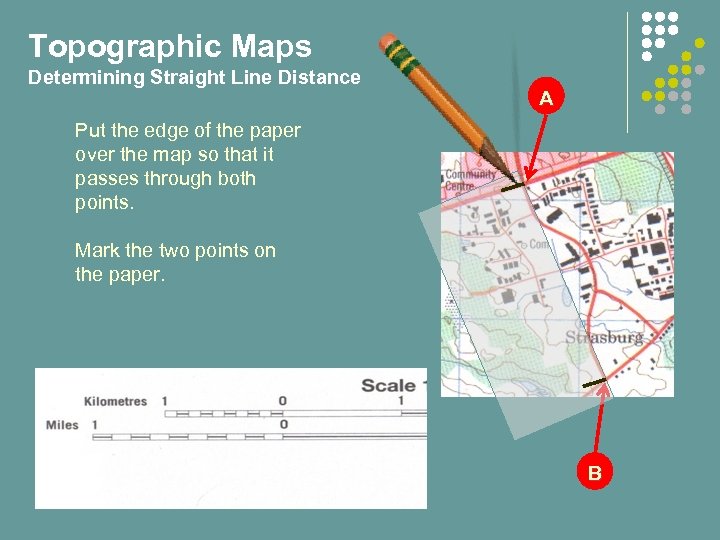

Topographic Maps Determining Straight Line Distance A In order to find the STRAIGHT LINE distance from “A” to “B” you will need a pencil and a piece of paper. B

Topographic Maps Determining Straight Line Distance A In order to find the STRAIGHT LINE distance from “A” to “B” you will need a pencil and a piece of paper. B

Topographic Maps Determining Straight Line Distance A Put the edge of the paper over the map so that it passes through both points. Mark the two points on the paper. B

Topographic Maps Determining Straight Line Distance A Put the edge of the paper over the map so that it passes through both points. Mark the two points on the paper. B

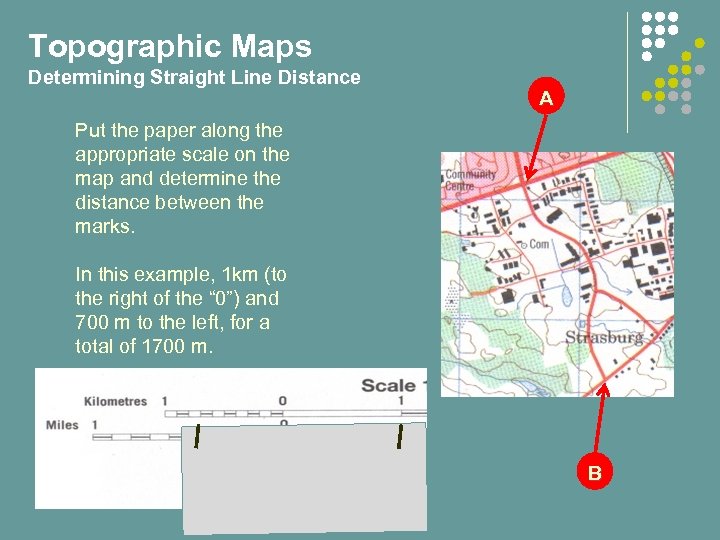

Topographic Maps Determining Straight Line Distance A Put the paper along the appropriate scale on the map and determine the distance between the marks. In this example, 1 km (to the right of the “ 0”) and 700 m to the left, for a total of 1700 m. B

Topographic Maps Determining Straight Line Distance A Put the paper along the appropriate scale on the map and determine the distance between the marks. In this example, 1 km (to the right of the “ 0”) and 700 m to the left, for a total of 1700 m. B

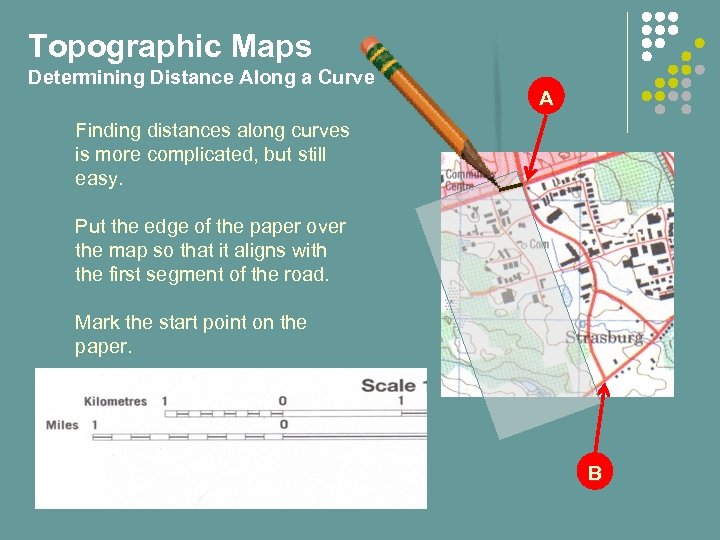

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Finding distances along curves is more complicated, but still easy. Put the edge of the paper over the map so that it aligns with the first segment of the road. Mark the start point on the paper. B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Finding distances along curves is more complicated, but still easy. Put the edge of the paper over the map so that it aligns with the first segment of the road. Mark the start point on the paper. B

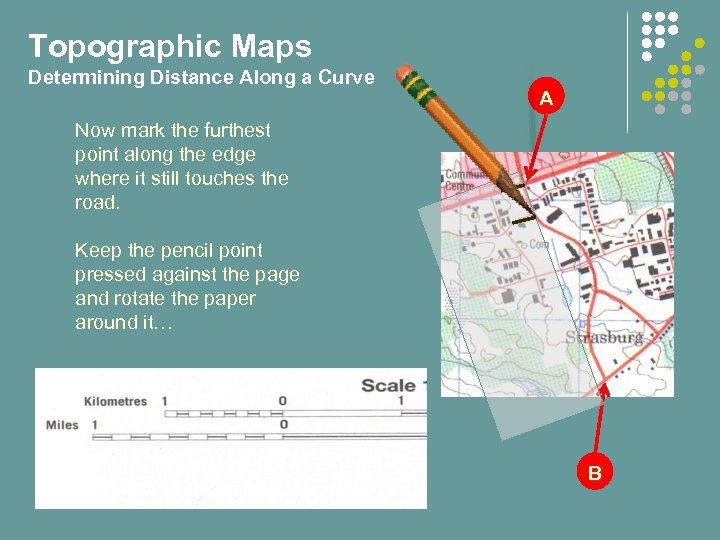

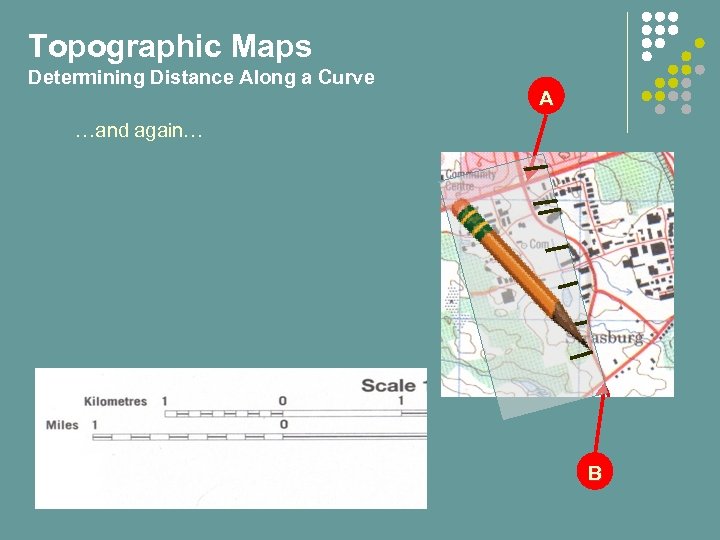

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Now mark the furthest point along the edge where it still touches the road. Keep the pencil point pressed against the page and rotate the paper around it… B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Now mark the furthest point along the edge where it still touches the road. Keep the pencil point pressed against the page and rotate the paper around it… B

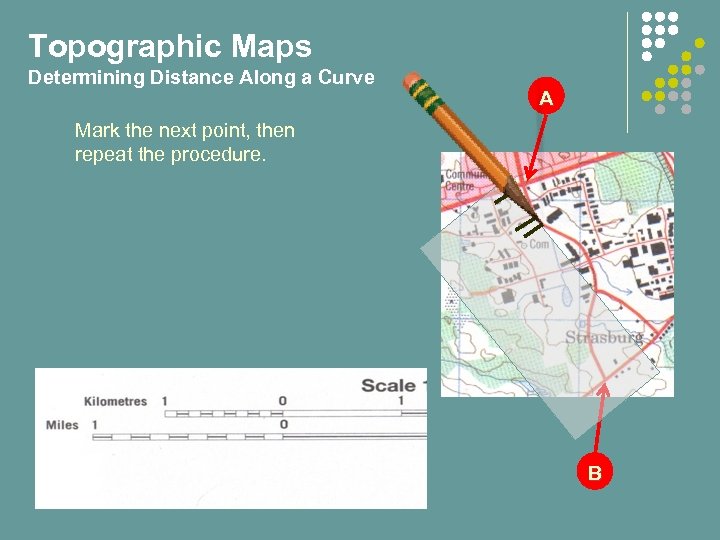

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Mark the next point, then repeat the procedure. B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Mark the next point, then repeat the procedure. B

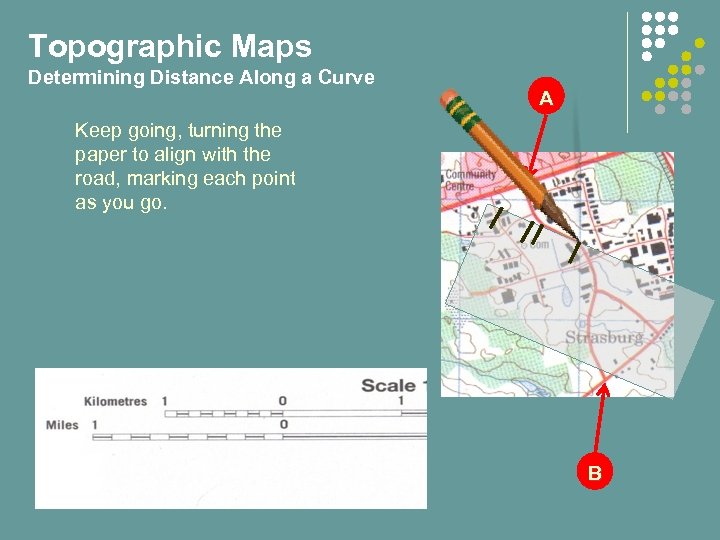

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Keep going, turning the paper to align with the road, marking each point as you go. B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Keep going, turning the paper to align with the road, marking each point as you go. B

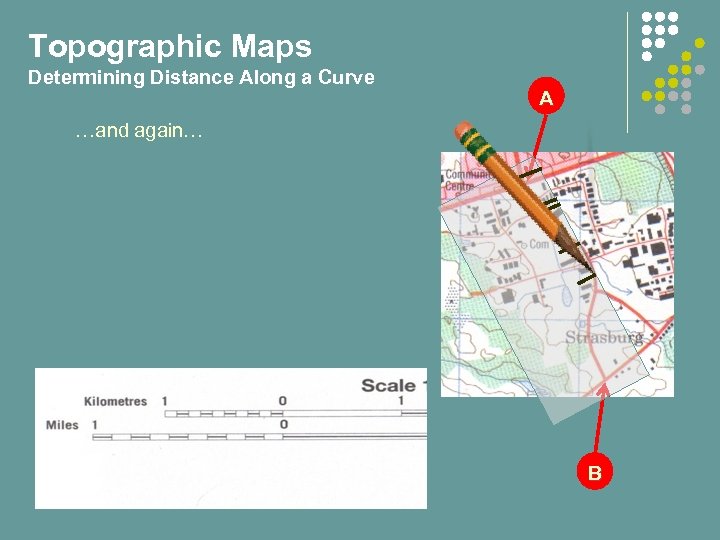

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A …and again… B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A …and again… B

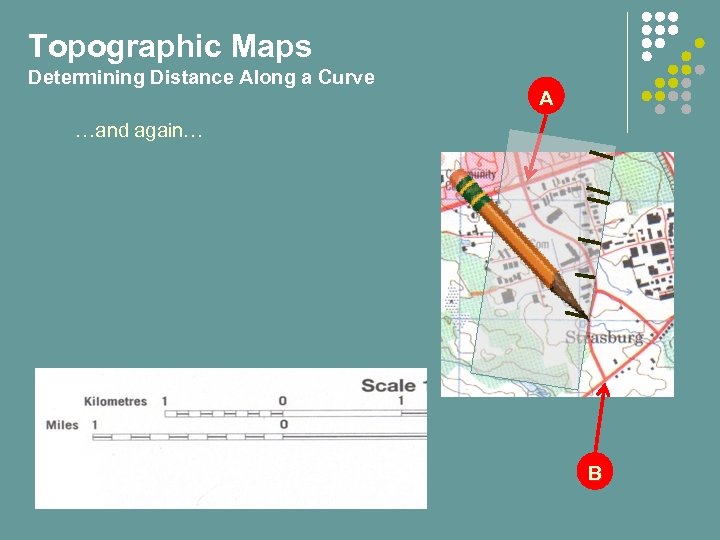

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A …and again… B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A …and again… B

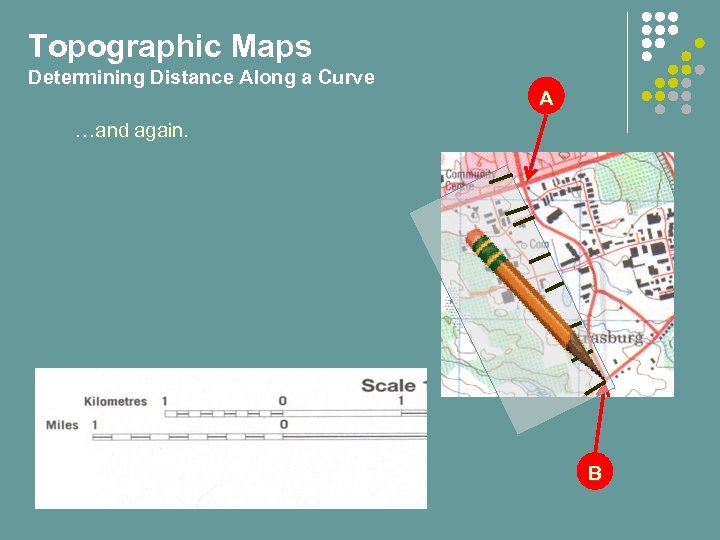

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A …and again… B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A …and again… B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A …and again. B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A …and again. B

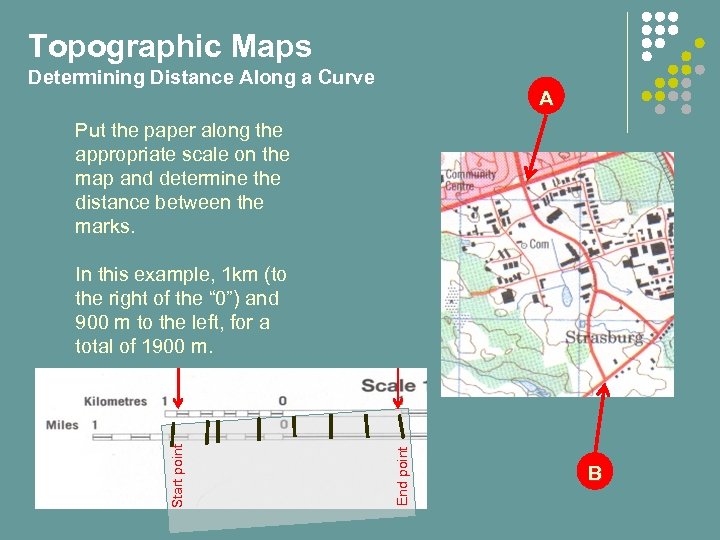

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Put the paper along the appropriate scale on the map and determine the distance between the marks. End point Start point In this example, 1 km (to the right of the “ 0”) and 900 m to the left, for a total of 1900 m. . B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Put the paper along the appropriate scale on the map and determine the distance between the marks. End point Start point In this example, 1 km (to the right of the “ 0”) and 900 m to the left, for a total of 1900 m. . B

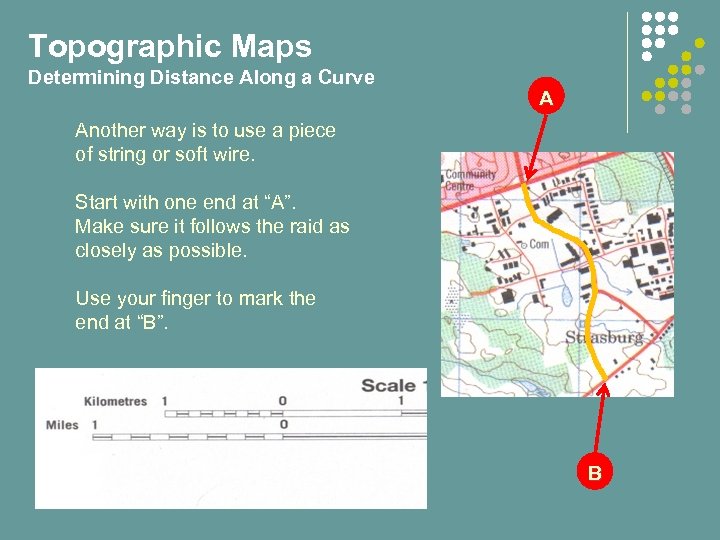

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Another way is to use a piece of string or soft wire. Start with one end at “A”. Make sure it follows the raid as closely as possible. Use your finger to mark the end at “B”. B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Another way is to use a piece of string or soft wire. Start with one end at “A”. Make sure it follows the raid as closely as possible. Use your finger to mark the end at “B”. B

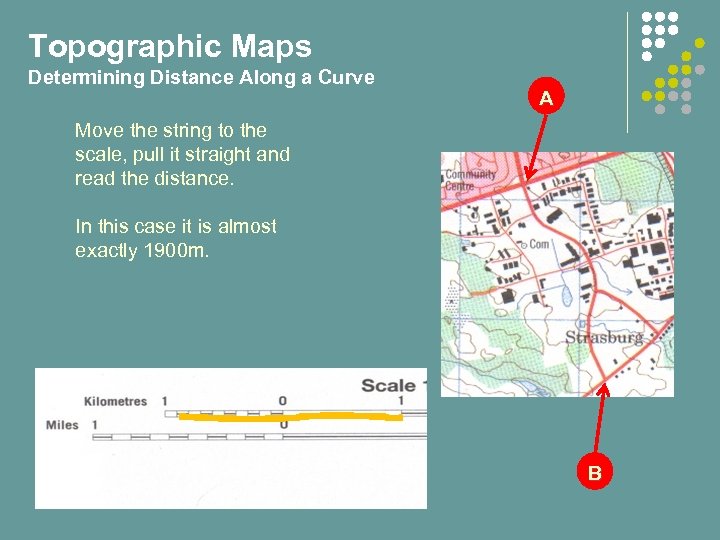

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Move the string to the scale, pull it straight and read the distance. In this case it is almost exactly 1900 m. B

Topographic Maps Determining Distance Along a Curve A Move the string to the scale, pull it straight and read the distance. In this case it is almost exactly 1900 m. B

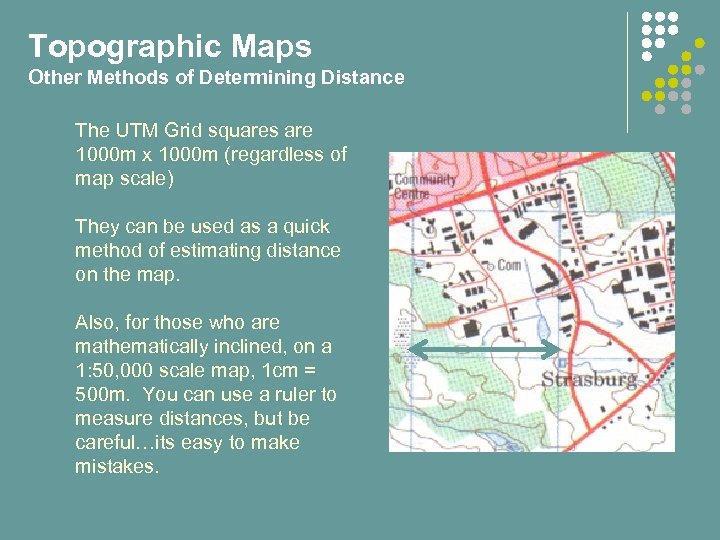

Topographic Maps Other Methods of Determining Distance The UTM Grid squares are 1000 m x 1000 m (regardless of map scale) They can be used as a quick method of estimating distance on the map. Also, for those who are mathematically inclined, on a 1: 50, 000 scale map, 1 cm = 500 m. You can use a ruler to measure distances, but be careful…its easy to make mistakes.

Topographic Maps Other Methods of Determining Distance The UTM Grid squares are 1000 m x 1000 m (regardless of map scale) They can be used as a quick method of estimating distance on the map. Also, for those who are mathematically inclined, on a 1: 50, 000 scale map, 1 cm = 500 m. You can use a ruler to measure distances, but be careful…its easy to make mistakes.

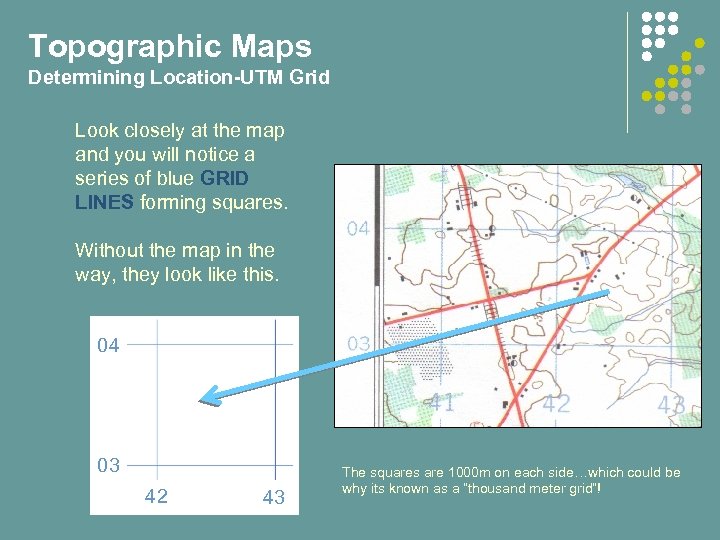

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid Look closely at the map and you will notice a series of blue GRID LINES forming squares. Without the map in the way, they look like this. 04 03 42 43 The squares are 1000 m on each side…which could be why its known as a “thousand meter grid”!

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid Look closely at the map and you will notice a series of blue GRID LINES forming squares. Without the map in the way, they look like this. 04 03 42 43 The squares are 1000 m on each side…which could be why its known as a “thousand meter grid”!

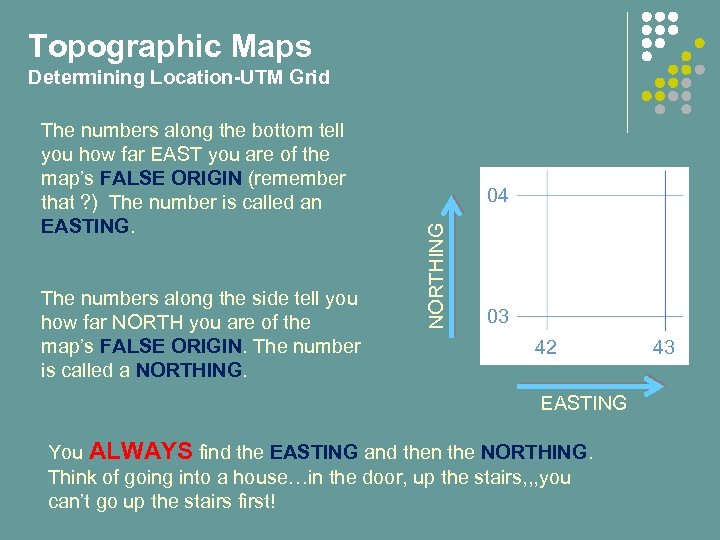

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid The numbers along the side tell you how far NORTH you are of the map’s FALSE ORIGIN. The number is called a NORTHING. 04 NORTHING The numbers along the bottom tell you how far EAST you are of the map’s FALSE ORIGIN (remember that ? ) The number is called an EASTING. 03 42 EASTING You ALWAYS find the EASTING and then the NORTHING. Think of going into a house…in the door, up the stairs, , , you can’t go up the stairs first! 43

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid The numbers along the side tell you how far NORTH you are of the map’s FALSE ORIGIN. The number is called a NORTHING. 04 NORTHING The numbers along the bottom tell you how far EAST you are of the map’s FALSE ORIGIN (remember that ? ) The number is called an EASTING. 03 42 EASTING You ALWAYS find the EASTING and then the NORTHING. Think of going into a house…in the door, up the stairs, , , you can’t go up the stairs first! 43

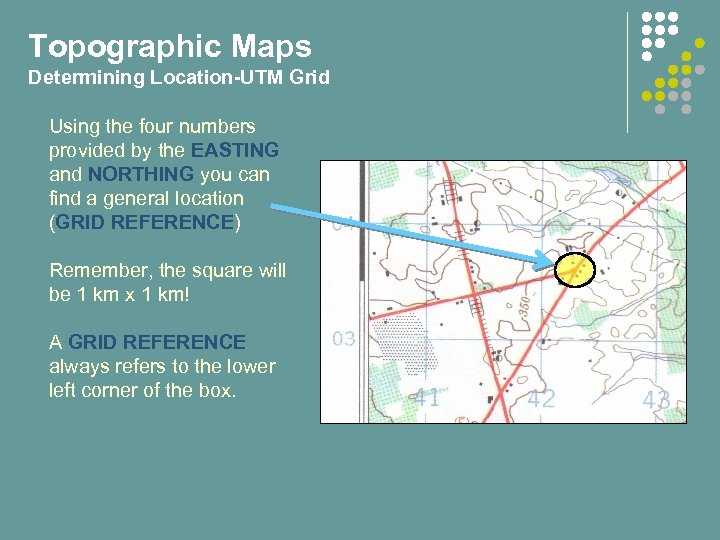

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid Using the four numbers provided by the EASTING and NORTHING you can find a general location (GRID REFERENCE) Remember, the square will be 1 km x 1 km! A GRID REFERENCE always refers to the lower left corner of the box.

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid Using the four numbers provided by the EASTING and NORTHING you can find a general location (GRID REFERENCE) Remember, the square will be 1 km x 1 km! A GRID REFERENCE always refers to the lower left corner of the box.

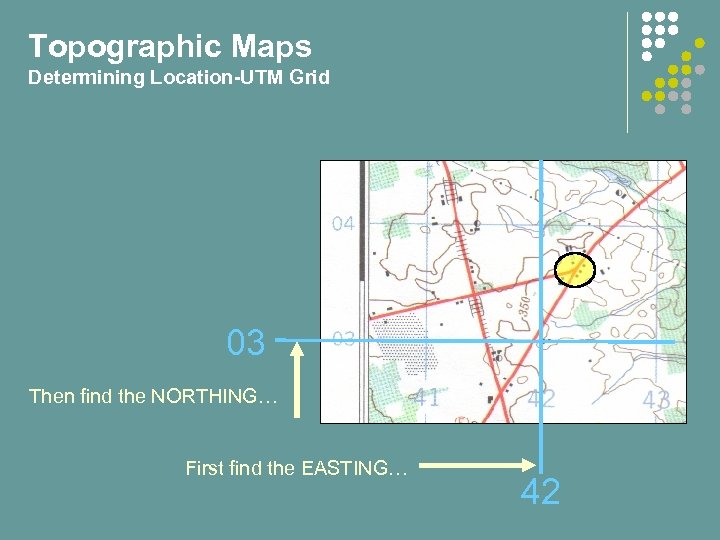

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid 03 Then find the NORTHING… First find the EASTING… 42

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid 03 Then find the NORTHING… First find the EASTING… 42

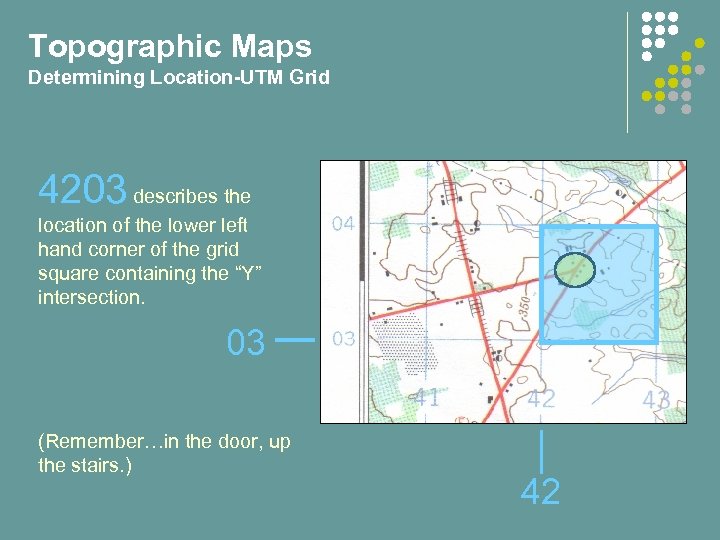

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid 4203 describes the location of the lower left hand corner of the grid square containing the “Y” intersection. 03 (Remember…in the door, up the stairs. ) 42

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid 4203 describes the location of the lower left hand corner of the grid square containing the “Y” intersection. 03 (Remember…in the door, up the stairs. ) 42

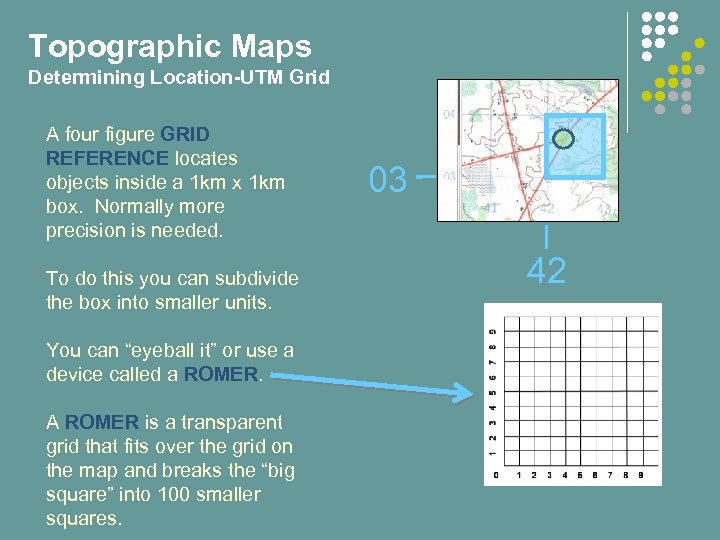

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid A four figure GRID REFERENCE locates objects inside a 1 km x 1 km box. Normally more precision is needed. To do this you can subdivide the box into smaller units. You can “eyeball it” or use a device called a ROMER. A ROMER is a transparent grid that fits over the grid on the map and breaks the “big square” into 100 smaller squares. 03 42

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid A four figure GRID REFERENCE locates objects inside a 1 km x 1 km box. Normally more precision is needed. To do this you can subdivide the box into smaller units. You can “eyeball it” or use a device called a ROMER. A ROMER is a transparent grid that fits over the grid on the map and breaks the “big square” into 100 smaller squares. 03 42

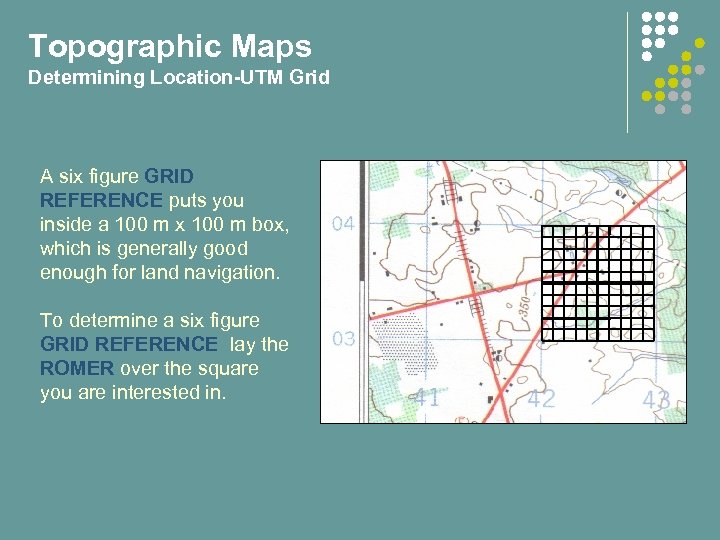

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid A six figure GRID REFERENCE puts you inside a 100 m x 100 m box, which is generally good enough for land navigation. To determine a six figure GRID REFERENCE lay the ROMER over the square you are interested in.

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid A six figure GRID REFERENCE puts you inside a 100 m x 100 m box, which is generally good enough for land navigation. To determine a six figure GRID REFERENCE lay the ROMER over the square you are interested in.

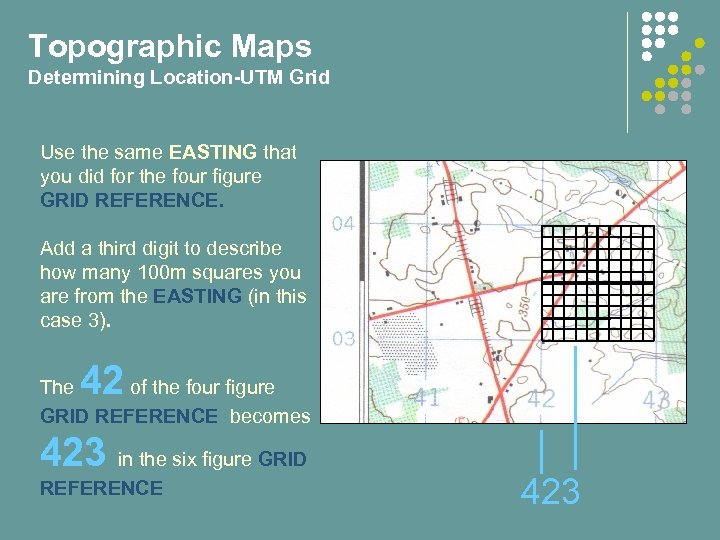

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid Use the same EASTING that you did for the four figure GRID REFERENCE. Add a third digit to describe how many 100 m squares you are from the EASTING (in this case 3). 42 The of the four figure GRID REFERENCE becomes 423 in the six figure GRID REFERENCE 423

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid Use the same EASTING that you did for the four figure GRID REFERENCE. Add a third digit to describe how many 100 m squares you are from the EASTING (in this case 3). 42 The of the four figure GRID REFERENCE becomes 423 in the six figure GRID REFERENCE 423

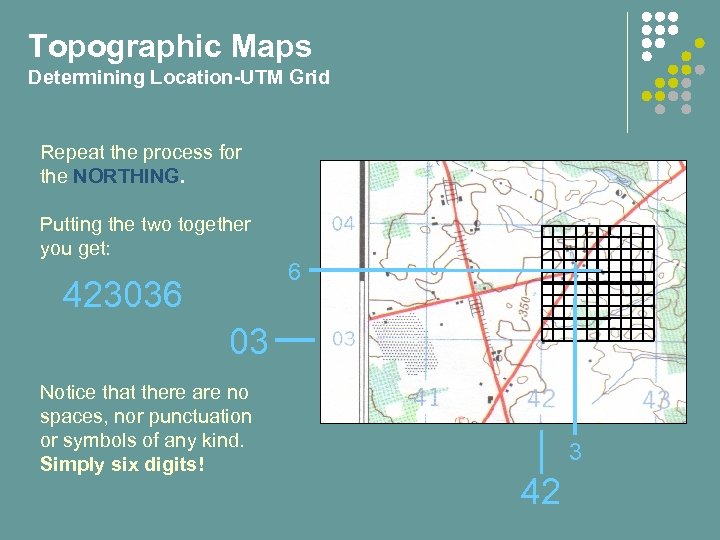

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid Repeat the process for the NORTHING. Putting the two together you get: 423036 6 03 Notice that there are no spaces, nor punctuation or symbols of any kind. Simply six digits! 3 42

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid Repeat the process for the NORTHING. Putting the two together you get: 423036 6 03 Notice that there are no spaces, nor punctuation or symbols of any kind. Simply six digits! 3 42

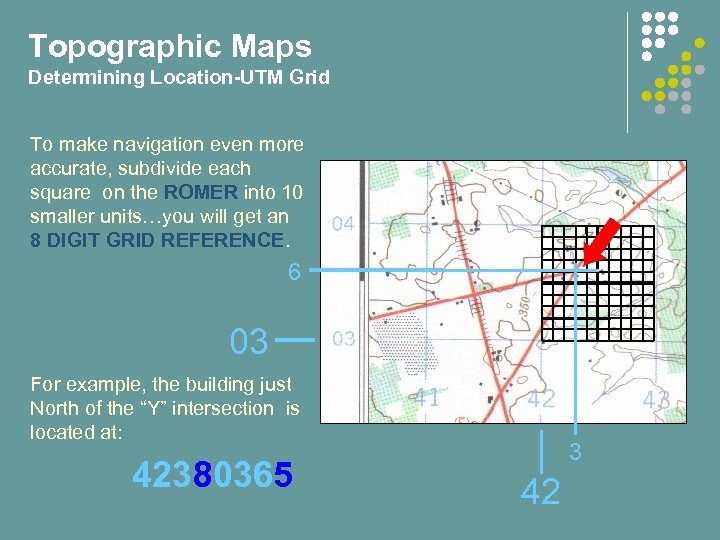

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid To make navigation even more accurate, subdivide each square on the ROMER into 10 smaller units…you will get an 8 DIGIT GRID REFERENCE. 6 03 For example, the building just North of the “Y” intersection is located at: 42380365 3 42

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid To make navigation even more accurate, subdivide each square on the ROMER into 10 smaller units…you will get an 8 DIGIT GRID REFERENCE. 6 03 For example, the building just North of the “Y” intersection is located at: 42380365 3 42

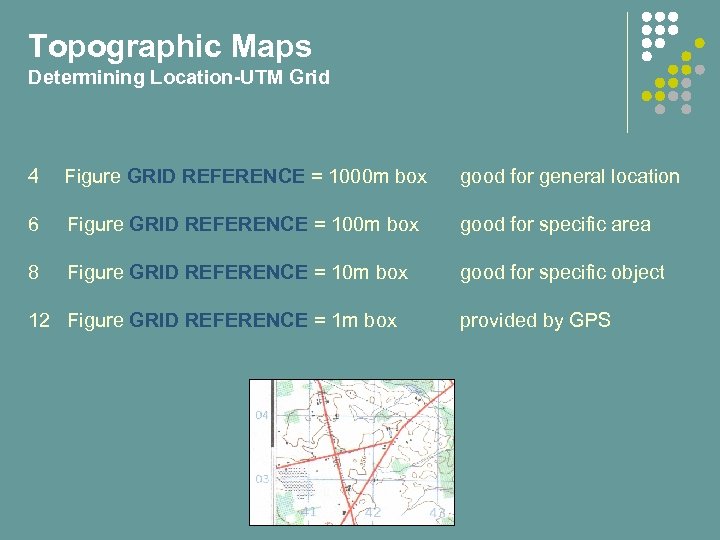

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid 4 Figure GRID REFERENCE = 1000 m box good for general location 6 Figure GRID REFERENCE = 100 m box good for specific area 8 Figure GRID REFERENCE = 10 m box good for specific object 12 Figure GRID REFERENCE = 1 m box provided by GPS

Topographic Maps Determining Location-UTM Grid 4 Figure GRID REFERENCE = 1000 m box good for general location 6 Figure GRID REFERENCE = 100 m box good for specific area 8 Figure GRID REFERENCE = 10 m box good for specific object 12 Figure GRID REFERENCE = 1 m box provided by GPS

Introduction to Map and Compass End of Part 2 Do QUIZ 2 now.

Introduction to Map and Compass End of Part 2 Do QUIZ 2 now.

Introduction to Map and Compass Part 3: The Compass

Introduction to Map and Compass Part 3: The Compass

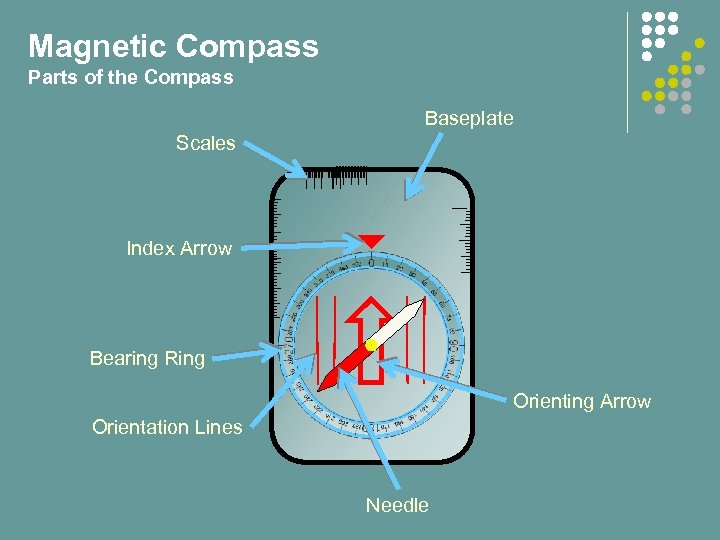

Magnetic Compass Parts of the Compass Baseplate Scales Index Arrow Bearing Ring Orienting Arrow Orientation Lines Needle

Magnetic Compass Parts of the Compass Baseplate Scales Index Arrow Bearing Ring Orienting Arrow Orientation Lines Needle

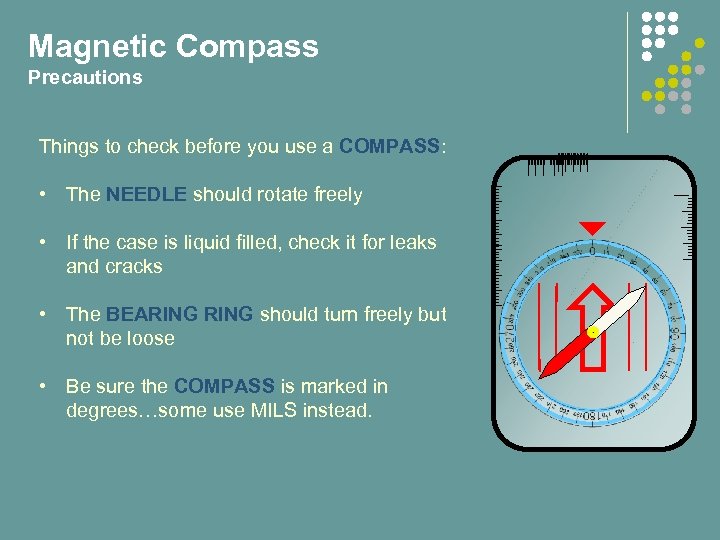

Magnetic Compass Precautions Things to check before you use a COMPASS: • The NEEDLE should rotate freely • If the case is liquid filled, check it for leaks and cracks • The BEARING should turn freely but not be loose • Be sure the COMPASS is marked in degrees…some use MILS instead.

Magnetic Compass Precautions Things to check before you use a COMPASS: • The NEEDLE should rotate freely • If the case is liquid filled, check it for leaks and cracks • The BEARING should turn freely but not be loose • Be sure the COMPASS is marked in degrees…some use MILS instead.

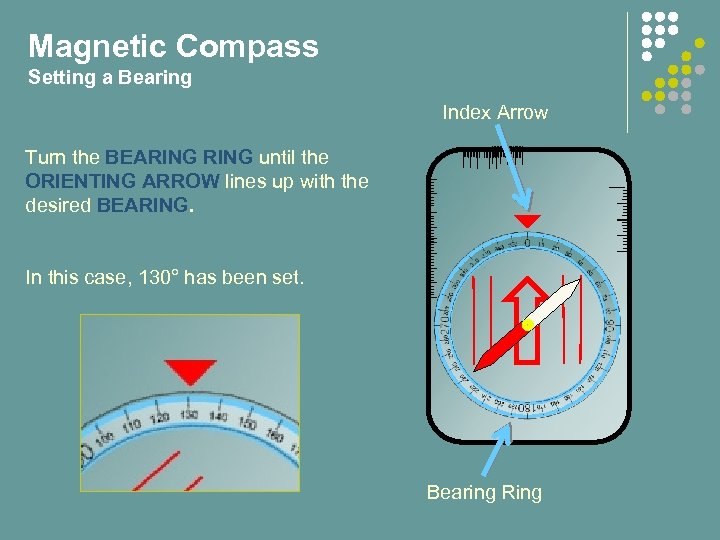

Magnetic Compass Setting a Bearing Index Arrow Turn the BEARING until the ORIENTING ARROW lines up with the desired BEARING. In this case, 130° has been set. Bearing Ring

Magnetic Compass Setting a Bearing Index Arrow Turn the BEARING until the ORIENTING ARROW lines up with the desired BEARING. In this case, 130° has been set. Bearing Ring

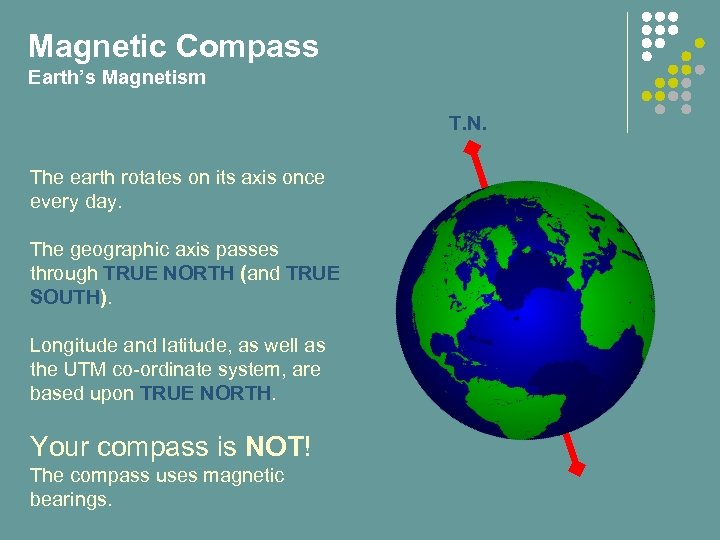

Magnetic Compass Earth’s Magnetism T. N. The earth rotates on its axis once every day. The geographic axis passes through TRUE NORTH (and TRUE SOUTH). Longitude and latitude, as well as the UTM co-ordinate system, are based upon TRUE NORTH. Your compass is NOT! The compass uses magnetic bearings.

Magnetic Compass Earth’s Magnetism T. N. The earth rotates on its axis once every day. The geographic axis passes through TRUE NORTH (and TRUE SOUTH). Longitude and latitude, as well as the UTM co-ordinate system, are based upon TRUE NORTH. Your compass is NOT! The compass uses magnetic bearings.

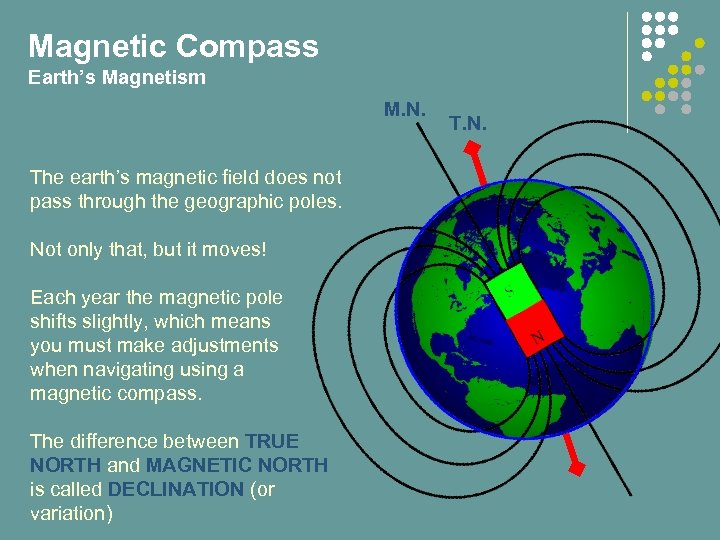

Magnetic Compass Earth’s Magnetism M. N. The earth’s magnetic field does not pass through the geographic poles. Not only that, but it moves! Each year the magnetic pole shifts slightly, which means you must make adjustments when navigating using a magnetic compass. The difference between TRUE NORTH and MAGNETIC NORTH is called DECLINATION (or variation) T. N.

Magnetic Compass Earth’s Magnetism M. N. The earth’s magnetic field does not pass through the geographic poles. Not only that, but it moves! Each year the magnetic pole shifts slightly, which means you must make adjustments when navigating using a magnetic compass. The difference between TRUE NORTH and MAGNETIC NORTH is called DECLINATION (or variation) T. N.

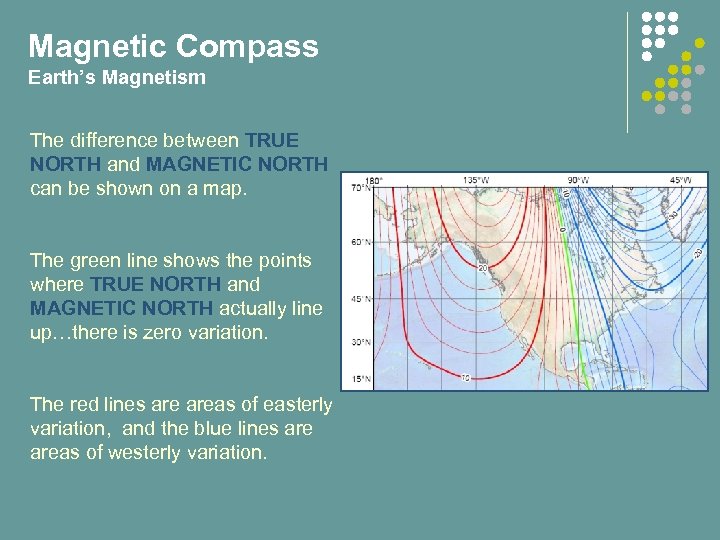

Magnetic Compass Earth’s Magnetism The difference between TRUE NORTH and MAGNETIC NORTH can be shown on a map. The green line shows the points where TRUE NORTH and MAGNETIC NORTH actually line up…there is zero variation. The red lines areas of easterly variation, and the blue lines areas of westerly variation.

Magnetic Compass Earth’s Magnetism The difference between TRUE NORTH and MAGNETIC NORTH can be shown on a map. The green line shows the points where TRUE NORTH and MAGNETIC NORTH actually line up…there is zero variation. The red lines areas of easterly variation, and the blue lines areas of westerly variation.

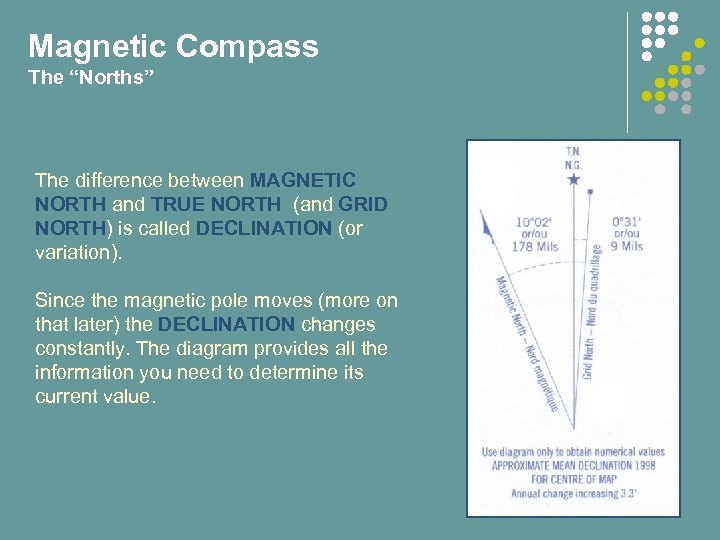

Magnetic Compass The “Norths” The difference between MAGNETIC NORTH and TRUE NORTH (and GRID NORTH) is called DECLINATION (or variation). Since the magnetic pole moves (more on that later) the DECLINATION changes constantly. The diagram provides all the information you need to determine its current value.

Magnetic Compass The “Norths” The difference between MAGNETIC NORTH and TRUE NORTH (and GRID NORTH) is called DECLINATION (or variation). Since the magnetic pole moves (more on that later) the DECLINATION changes constantly. The diagram provides all the information you need to determine its current value.

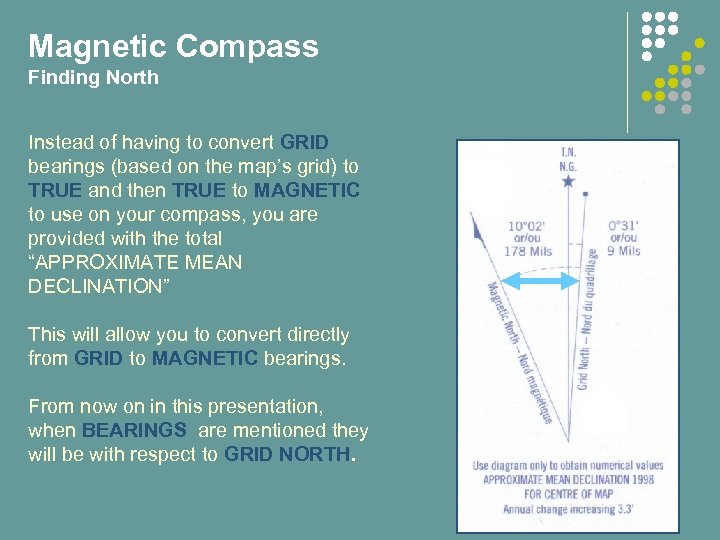

Magnetic Compass Finding North Instead of having to convert GRID bearings (based on the map’s grid) to TRUE and then TRUE to MAGNETIC to use on your compass, you are provided with the total “APPROXIMATE MEAN DECLINATION” This will allow you to convert directly from GRID to MAGNETIC bearings. From now on in this presentation, when BEARINGS are mentioned they will be with respect to GRID NORTH.

Magnetic Compass Finding North Instead of having to convert GRID bearings (based on the map’s grid) to TRUE and then TRUE to MAGNETIC to use on your compass, you are provided with the total “APPROXIMATE MEAN DECLINATION” This will allow you to convert directly from GRID to MAGNETIC bearings. From now on in this presentation, when BEARINGS are mentioned they will be with respect to GRID NORTH.

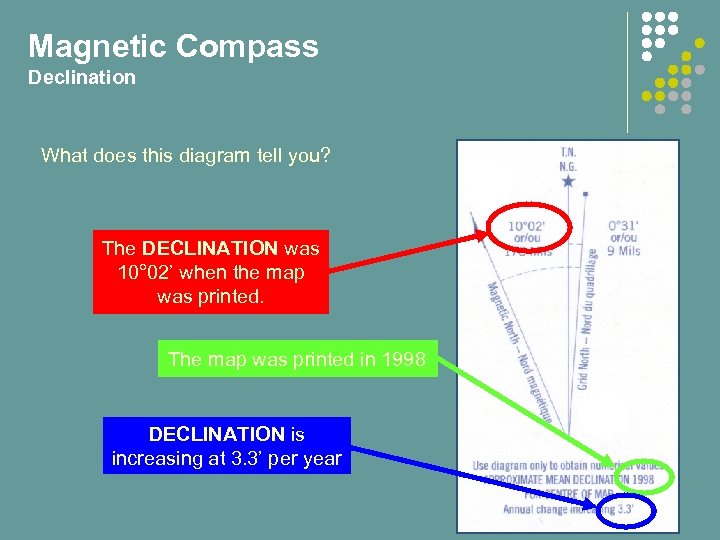

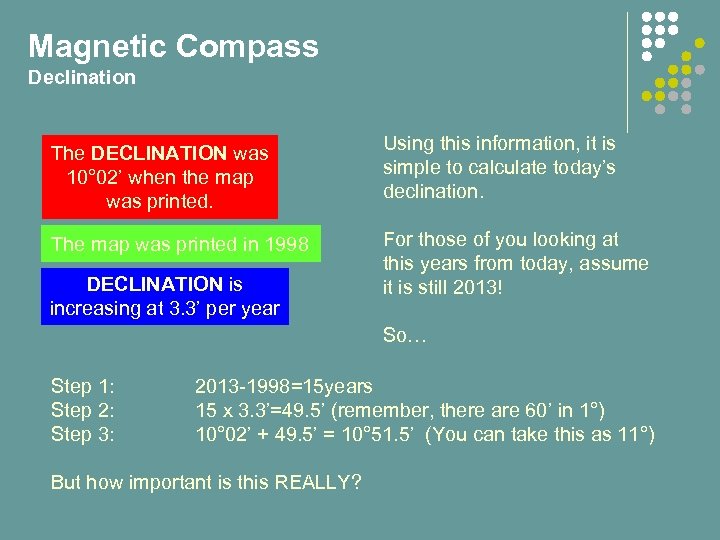

Magnetic Compass Declination What does this diagram tell you? The DECLINATION was 10° 02’ when the map was printed. The map was printed in 1998 DECLINATION is increasing at 3. 3’ per year

Magnetic Compass Declination What does this diagram tell you? The DECLINATION was 10° 02’ when the map was printed. The map was printed in 1998 DECLINATION is increasing at 3. 3’ per year

Magnetic Compass Declination The DECLINATION was 10° 02’ when the map was printed. Using this information, it is simple to calculate today’s declination. The map was printed in 1998 For those of you looking at this years from today, assume it is still 2013! DECLINATION is increasing at 3. 3’ per year So… Step 1: Step 2: Step 3: 2013 -1998=15 years 15 x 3. 3’=49. 5’ (remember, there are 60’ in 1°) 10° 02’ + 49. 5’ = 10° 51. 5’ (You can take this as 11°) But how important is this REALLY?

Magnetic Compass Declination The DECLINATION was 10° 02’ when the map was printed. Using this information, it is simple to calculate today’s declination. The map was printed in 1998 For those of you looking at this years from today, assume it is still 2013! DECLINATION is increasing at 3. 3’ per year So… Step 1: Step 2: Step 3: 2013 -1998=15 years 15 x 3. 3’=49. 5’ (remember, there are 60’ in 1°) 10° 02’ + 49. 5’ = 10° 51. 5’ (You can take this as 11°) But how important is this REALLY?

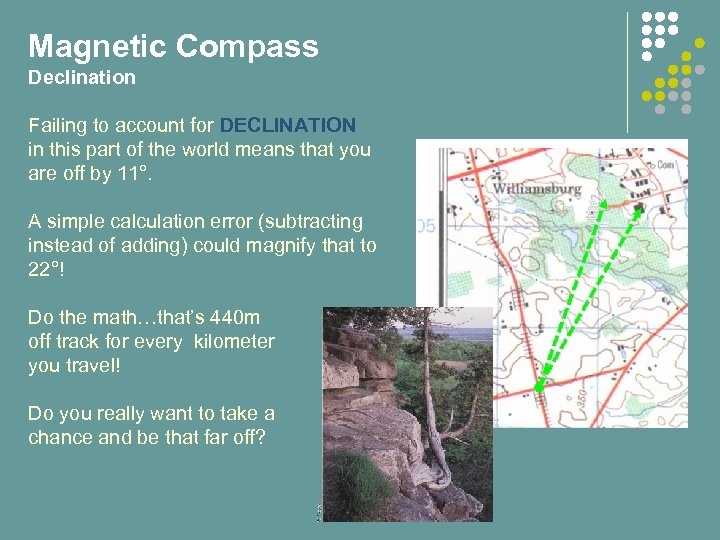

Magnetic Compass Declination Failing to account for DECLINATION in this part of the world means that you are off by 11°. A simple calculation error (subtracting instead of adding) could magnify that to 22°! Do the math…that’s 440 m off track for every kilometer you travel! Do you really want to take a chance and be that far off?

Magnetic Compass Declination Failing to account for DECLINATION in this part of the world means that you are off by 11°. A simple calculation error (subtracting instead of adding) could magnify that to 22°! Do the math…that’s 440 m off track for every kilometer you travel! Do you really want to take a chance and be that far off?

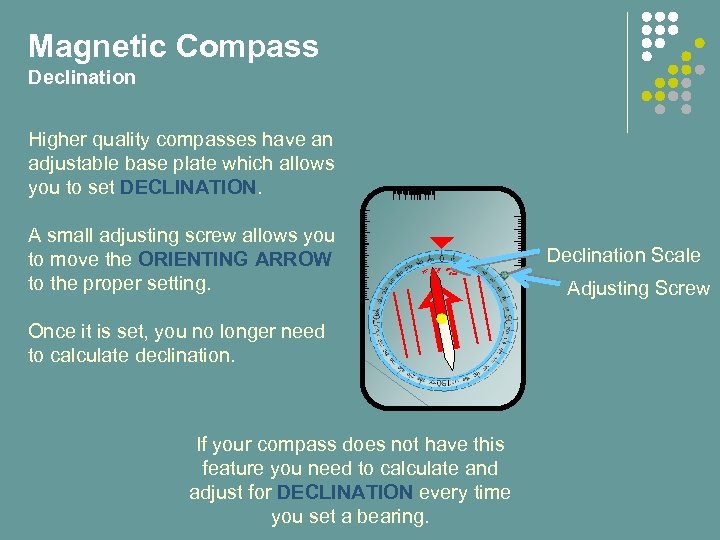

Magnetic Compass Declination Higher quality compasses have an adjustable base plate which allows you to set DECLINATION. A small adjusting screw allows you to move the ORIENTING ARROW to the proper setting. Declination Scale 10° 5° 20° West 5° 10° East 20° Once it is set, you no longer need to calculate declination. If your compass does not have this feature you need to calculate and adjust for DECLINATION every time you set a bearing. Adjusting Screw

Magnetic Compass Declination Higher quality compasses have an adjustable base plate which allows you to set DECLINATION. A small adjusting screw allows you to move the ORIENTING ARROW to the proper setting. Declination Scale 10° 5° 20° West 5° 10° East 20° Once it is set, you no longer need to calculate declination. If your compass does not have this feature you need to calculate and adjust for DECLINATION every time you set a bearing. Adjusting Screw

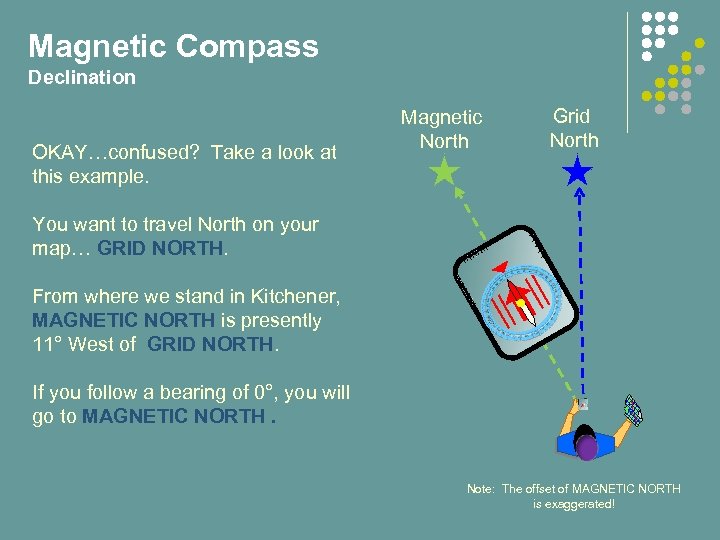

Magnetic Compass Declination OKAY…confused? Take a look at this example. Magnetic North Grid North You want to travel North on your map… GRID NORTH. From where we stand in Kitchener, MAGNETIC NORTH is presently 11° West of GRID NORTH. If you follow a bearing of 0°, you will go to MAGNETIC NORTH. Note: The offset of MAGNETIC NORTH is exaggerated!

Magnetic Compass Declination OKAY…confused? Take a look at this example. Magnetic North Grid North You want to travel North on your map… GRID NORTH. From where we stand in Kitchener, MAGNETIC NORTH is presently 11° West of GRID NORTH. If you follow a bearing of 0°, you will go to MAGNETIC NORTH. Note: The offset of MAGNETIC NORTH is exaggerated!

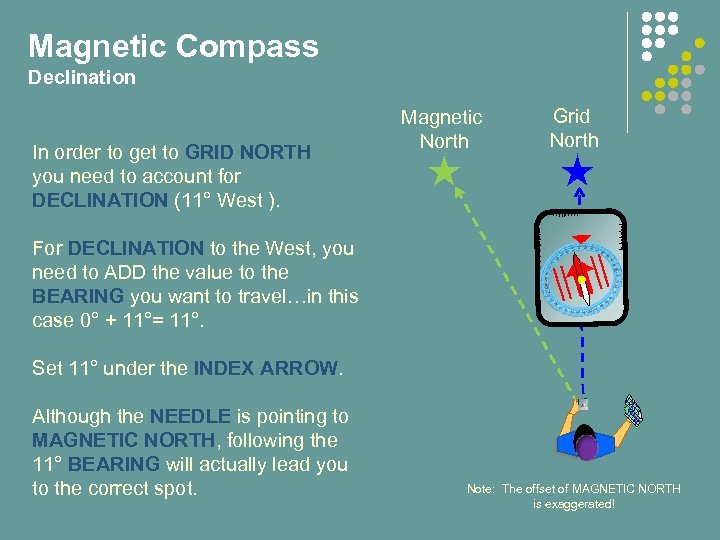

Magnetic Compass Declination In order to get to GRID NORTH you need to account for DECLINATION (11° West ). Magnetic North Grid North For DECLINATION to the West, you need to ADD the value to the BEARING you want to travel…in this case 0° + 11°= 11°. Set 11° under the INDEX ARROW. Although the NEEDLE is pointing to MAGNETIC NORTH, following the 11° BEARING will actually lead you to the correct spot. Note: The offset of MAGNETIC NORTH is exaggerated!

Magnetic Compass Declination In order to get to GRID NORTH you need to account for DECLINATION (11° West ). Magnetic North Grid North For DECLINATION to the West, you need to ADD the value to the BEARING you want to travel…in this case 0° + 11°= 11°. Set 11° under the INDEX ARROW. Although the NEEDLE is pointing to MAGNETIC NORTH, following the 11° BEARING will actually lead you to the correct spot. Note: The offset of MAGNETIC NORTH is exaggerated!

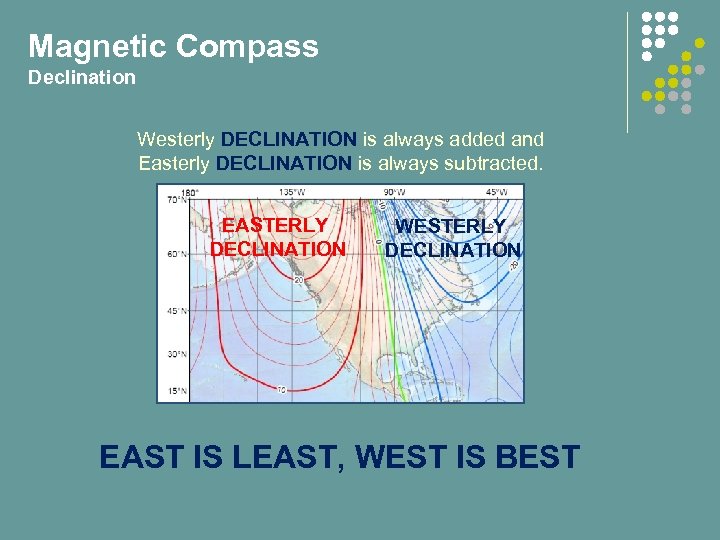

Magnetic Compass Declination Westerly DECLINATION is always added and Easterly DECLINATION is always subtracted. EASTERLY DECLINATION WESTERLY DECLINATION EAST IS LEAST, WEST IS BEST

Magnetic Compass Declination Westerly DECLINATION is always added and Easterly DECLINATION is always subtracted. EASTERLY DECLINATION WESTERLY DECLINATION EAST IS LEAST, WEST IS BEST

Introduction to Map and Compass End of Part 3 Do QUIZ 3 now.

Introduction to Map and Compass End of Part 3 Do QUIZ 3 now.

Introduction to Map and Compass Part 4: Navigation

Introduction to Map and Compass Part 4: Navigation

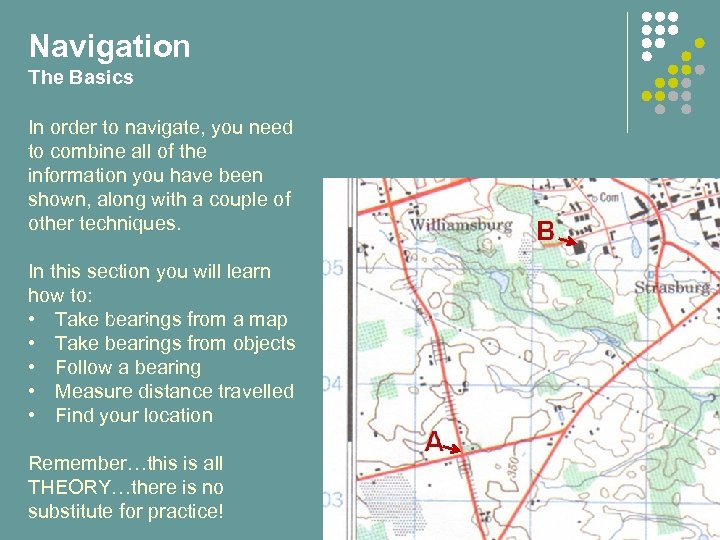

Navigation The Basics In order to navigate, you need to combine all of the information you have been shown, along with a couple of other techniques. In this section you will learn how to: • Take bearings from a map • Take bearings from objects • Follow a bearing • Measure distance travelled • Find your location Remember…this is all THEORY…there is no substitute for practice!

Navigation The Basics In order to navigate, you need to combine all of the information you have been shown, along with a couple of other techniques. In this section you will learn how to: • Take bearings from a map • Take bearings from objects • Follow a bearing • Measure distance travelled • Find your location Remember…this is all THEORY…there is no substitute for practice!

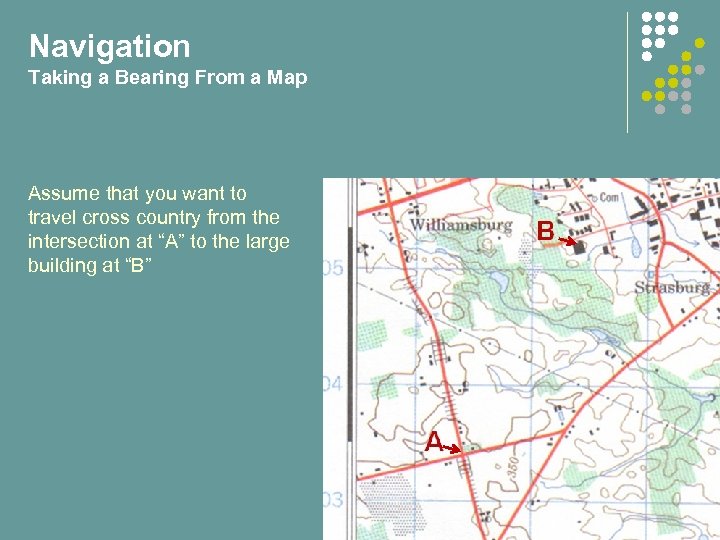

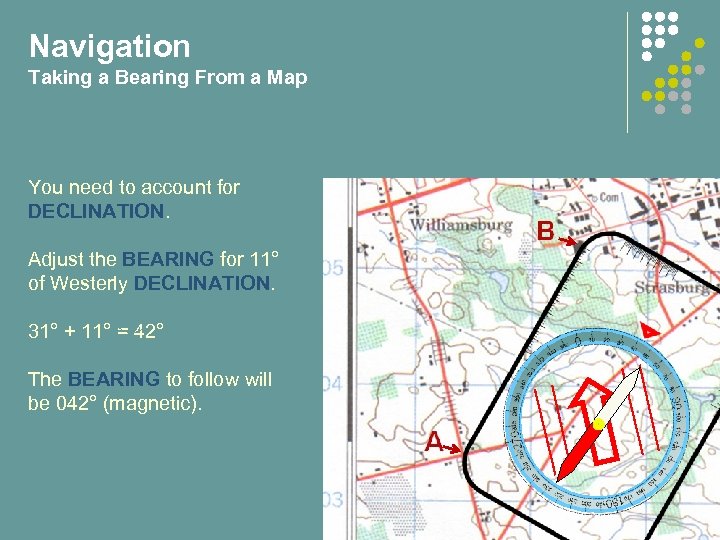

Navigation Taking a Bearing From a Map Assume that you want to travel cross country from the intersection at “A” to the large building at “B”

Navigation Taking a Bearing From a Map Assume that you want to travel cross country from the intersection at “A” to the large building at “B”

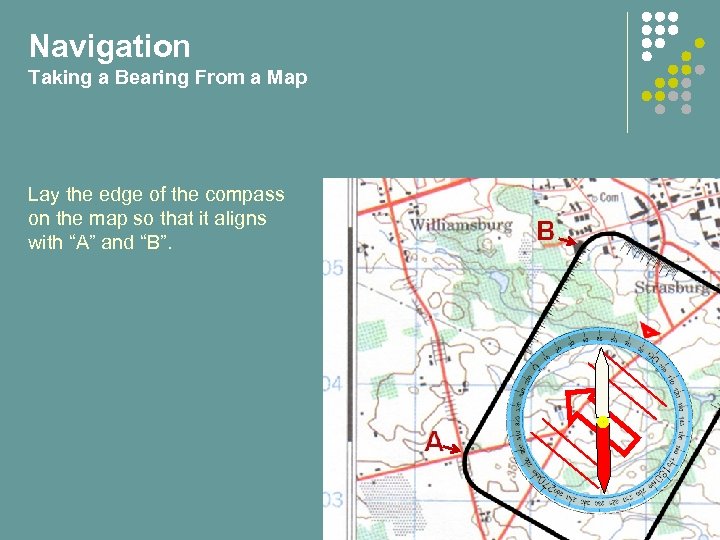

Navigation Taking a Bearing From a Map Lay the edge of the compass on the map so that it aligns with “A” and “B”.

Navigation Taking a Bearing From a Map Lay the edge of the compass on the map so that it aligns with “A” and “B”.

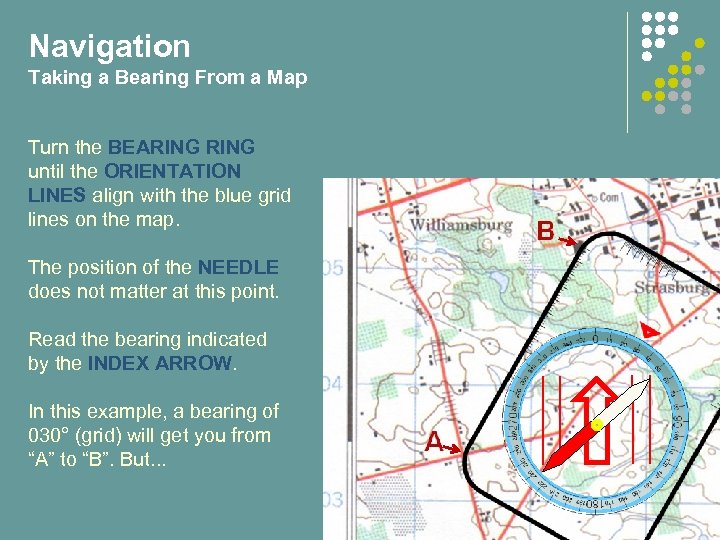

Navigation Taking a Bearing From a Map Turn the BEARING until the ORIENTATION LINES align with the blue grid lines on the map. The position of the NEEDLE does not matter at this point. Read the bearing indicated by the INDEX ARROW. In this example, a bearing of 030° (grid) will get you from “A” to “B”. But. . .

Navigation Taking a Bearing From a Map Turn the BEARING until the ORIENTATION LINES align with the blue grid lines on the map. The position of the NEEDLE does not matter at this point. Read the bearing indicated by the INDEX ARROW. In this example, a bearing of 030° (grid) will get you from “A” to “B”. But. . .

Navigation Taking a Bearing From a Map You need to account for DECLINATION. Adjust the BEARING for 11° of Westerly DECLINATION. 31° + 11° = 42° The BEARING to follow will be 042° (magnetic).

Navigation Taking a Bearing From a Map You need to account for DECLINATION. Adjust the BEARING for 11° of Westerly DECLINATION. 31° + 11° = 42° The BEARING to follow will be 042° (magnetic).

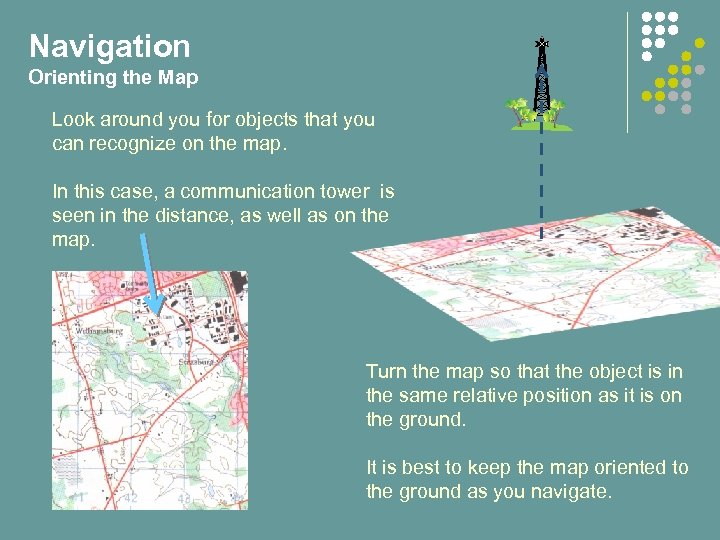

Navigation Orienting the Map Look around you for objects that you can recognize on the map. In this case, a communication tower is seen in the distance, as well as on the map. Turn the map so that the object is in the same relative position as it is on the ground. It is best to keep the map oriented to the ground as you navigate.

Navigation Orienting the Map Look around you for objects that you can recognize on the map. In this case, a communication tower is seen in the distance, as well as on the map. Turn the map so that the object is in the same relative position as it is on the ground. It is best to keep the map oriented to the ground as you navigate.

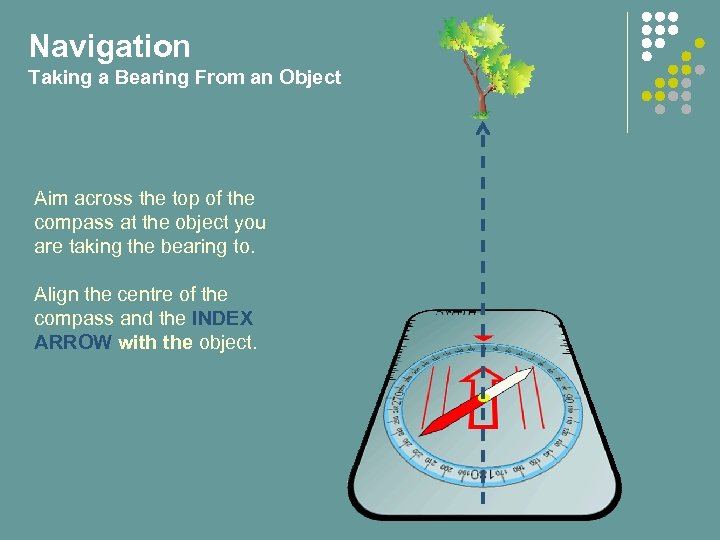

Navigation Taking a Bearing From an Object Aim across the top of the compass at the object you are taking the bearing to. Align the centre of the compass and the INDEX ARROW with the object.

Navigation Taking a Bearing From an Object Aim across the top of the compass at the object you are taking the bearing to. Align the centre of the compass and the INDEX ARROW with the object.

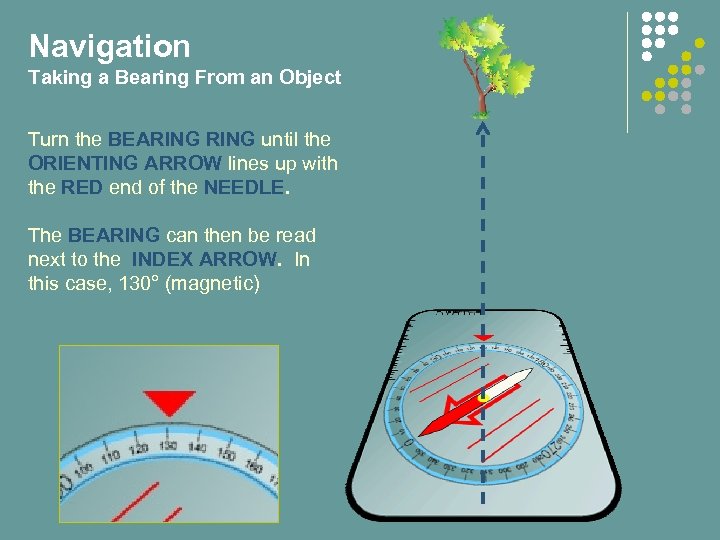

Navigation Taking a Bearing From an Object Turn the BEARING until the ORIENTING ARROW lines up with the RED end of the NEEDLE. The BEARING can then be read next to the INDEX ARROW. In this case, 130° (magnetic)

Navigation Taking a Bearing From an Object Turn the BEARING until the ORIENTING ARROW lines up with the RED end of the NEEDLE. The BEARING can then be read next to the INDEX ARROW. In this case, 130° (magnetic)

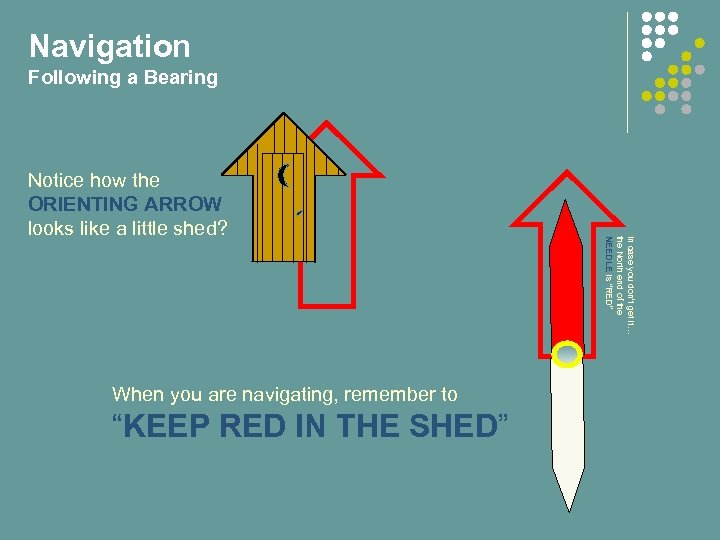

Navigation Following a Bearing When you are navigating, remember to “KEEP RED IN THE SHED” In case you don’t get it… the North end of the NEEDLE is “RED” Notice how the ORIENTING ARROW looks like a little shed?

Navigation Following a Bearing When you are navigating, remember to “KEEP RED IN THE SHED” In case you don’t get it… the North end of the NEEDLE is “RED” Notice how the ORIENTING ARROW looks like a little shed?

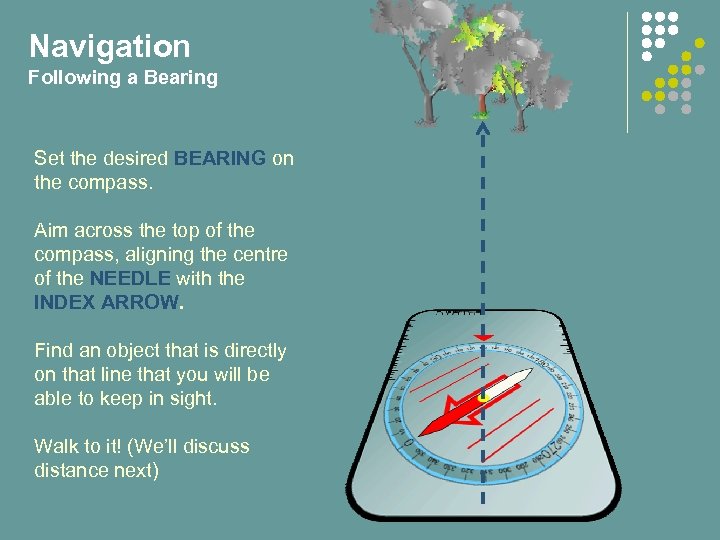

Navigation Following a Bearing Set the desired BEARING on the compass. Aim across the top of the compass, aligning the centre of the NEEDLE with the INDEX ARROW. Find an object that is directly on that line that you will be able to keep in sight. Walk to it! (We’ll discuss distance next)

Navigation Following a Bearing Set the desired BEARING on the compass. Aim across the top of the compass, aligning the centre of the NEEDLE with the INDEX ARROW. Find an object that is directly on that line that you will be able to keep in sight. Walk to it! (We’ll discuss distance next)

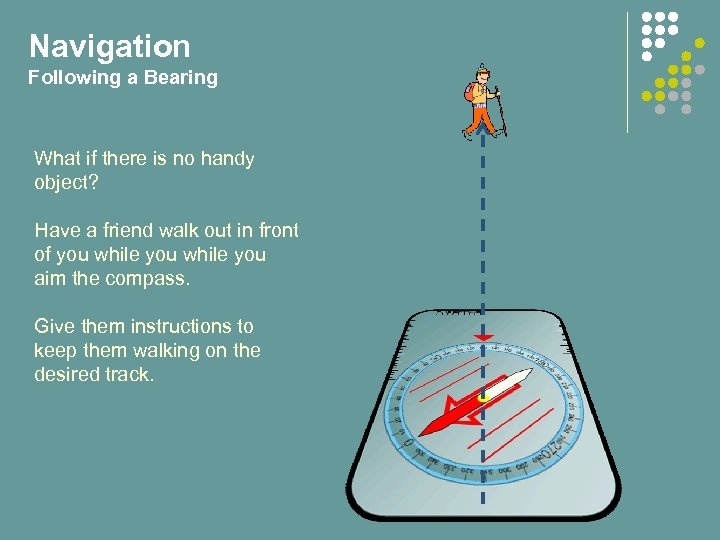

Navigation Following a Bearing What if there is no handy object? Have a friend walk out in front of you while you aim the compass. Give them instructions to keep them walking on the desired track.

Navigation Following a Bearing What if there is no handy object? Have a friend walk out in front of you while you aim the compass. Give them instructions to keep them walking on the desired track.

Navigation Determining Distance The compass will point you in the correct direction, but you also need to know how to measure the distance you have covered. The easiest way to do this is by counting paces. Everybody’s pace is different, so you need to know yours!

Navigation Determining Distance The compass will point you in the correct direction, but you also need to know how to measure the distance you have covered. The easiest way to do this is by counting paces. Everybody’s pace is different, so you need to know yours!

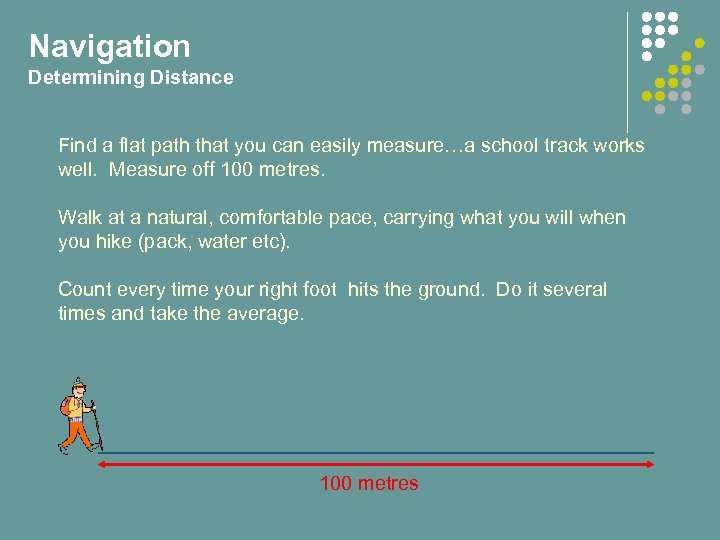

Navigation Determining Distance Find a flat path that you can easily measure…a school track works well. Measure off 100 metres. Walk at a natural, comfortable pace, carrying what you will when you hike (pack, water etc). Count every time your right foot hits the ground. Do it several times and take the average. 100 metres

Navigation Determining Distance Find a flat path that you can easily measure…a school track works well. Measure off 100 metres. Walk at a natural, comfortable pace, carrying what you will when you hike (pack, water etc). Count every time your right foot hits the ground. Do it several times and take the average. 100 metres

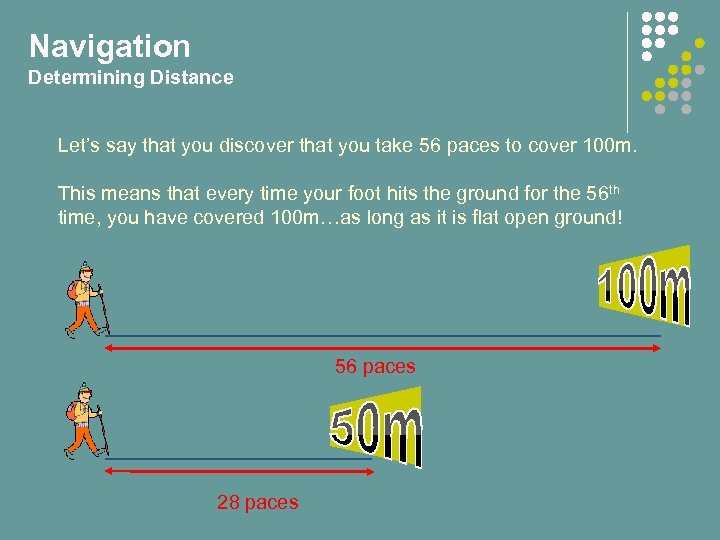

Navigation Determining Distance Let’s say that you discover that you take 56 paces to cover 100 m. This means that every time your foot hits the ground for the 56 th time, you have covered 100 m…as long as it is flat open ground! 56 paces 28 paces

Navigation Determining Distance Let’s say that you discover that you take 56 paces to cover 100 m. This means that every time your foot hits the ground for the 56 th time, you have covered 100 m…as long as it is flat open ground! 56 paces 28 paces

Navigation Determining Distance You should find a place to try pacing up a hill…it will take more paces! Also pace down the hill…you should take fewer. Also, pacing in wooded areas is significantly different that open fields! This requires practice, but with time you will learn how to accurately measure your movement over various types of terrain.

Navigation Determining Distance You should find a place to try pacing up a hill…it will take more paces! Also pace down the hill…you should take fewer. Also, pacing in wooded areas is significantly different that open fields! This requires practice, but with time you will learn how to accurately measure your movement over various types of terrain.

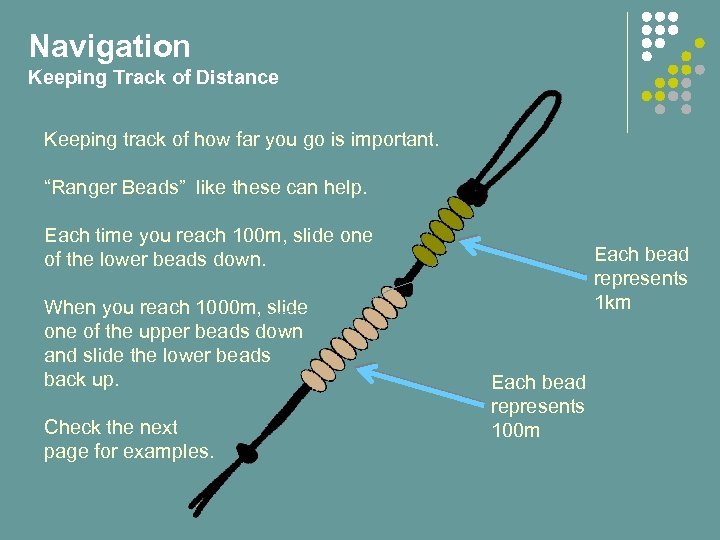

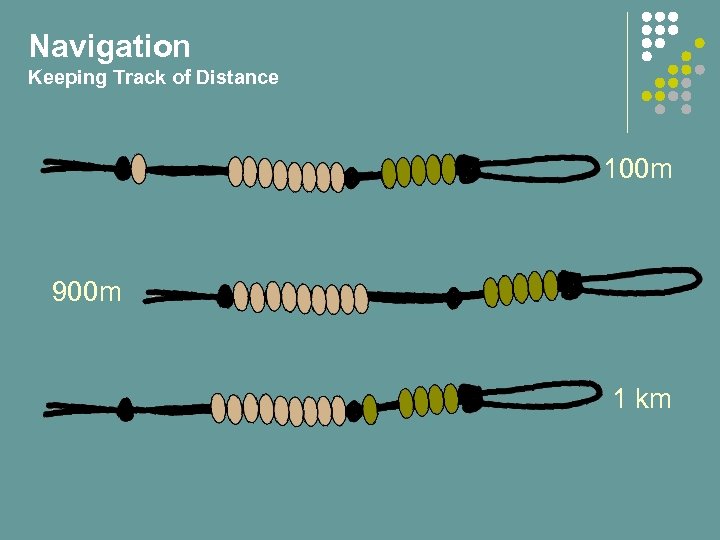

Navigation Keeping Track of Distance Keeping track of how far you go is important. “Ranger Beads” like these can help. Each time you reach 100 m, slide one of the lower beads down. When you reach 1000 m, slide one of the upper beads down and slide the lower beads back up. Check the next page for examples. Each bead represents 1 km Each bead represents 100 m

Navigation Keeping Track of Distance Keeping track of how far you go is important. “Ranger Beads” like these can help. Each time you reach 100 m, slide one of the lower beads down. When you reach 1000 m, slide one of the upper beads down and slide the lower beads back up. Check the next page for examples. Each bead represents 1 km Each bead represents 100 m

Navigation Keeping Track of Distance 100 m 900 m 1 km

Navigation Keeping Track of Distance 100 m 900 m 1 km

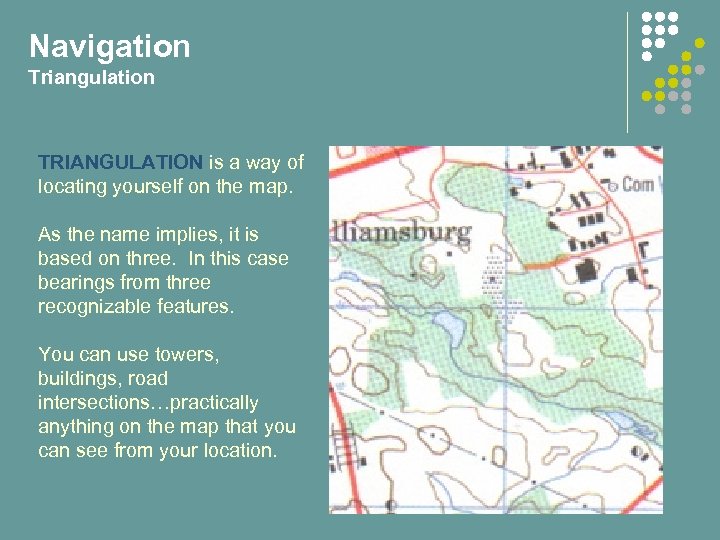

Navigation Triangulation TRIANGULATION is a way of locating yourself on the map. As the name implies, it is based on three. In this case bearings from three recognizable features. You can use towers, buildings, road intersections…practically anything on the map that you can see from your location.

Navigation Triangulation TRIANGULATION is a way of locating yourself on the map. As the name implies, it is based on three. In this case bearings from three recognizable features. You can use towers, buildings, road intersections…practically anything on the map that you can see from your location.

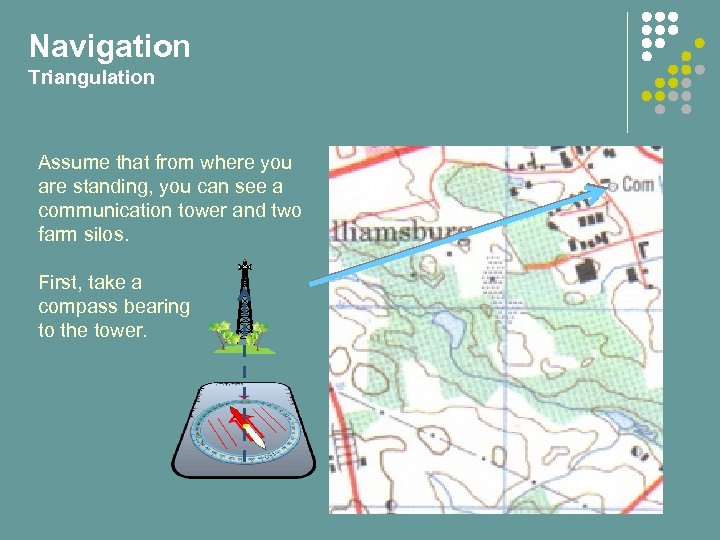

Navigation Triangulation Assume that from where you are standing, you can see a communication tower and two farm silos. First, take a compass bearing to the tower.

Navigation Triangulation Assume that from where you are standing, you can see a communication tower and two farm silos. First, take a compass bearing to the tower.

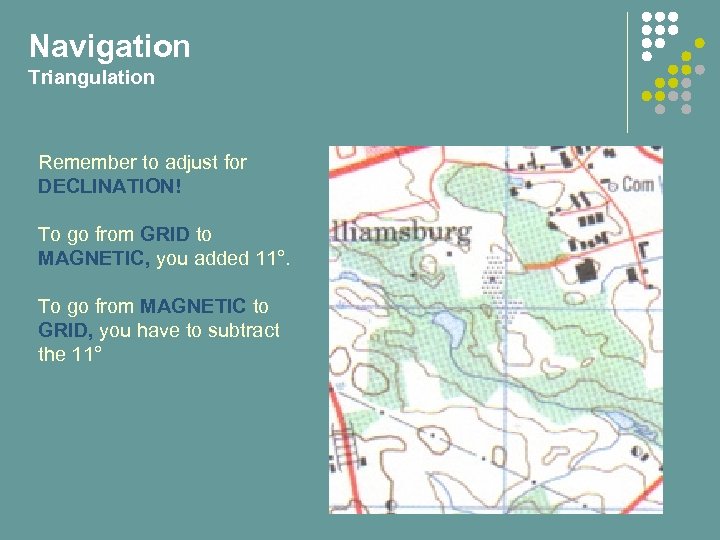

Navigation Triangulation Remember to adjust for DECLINATION! To go from GRID to MAGNETIC, you added 11°. To go from MAGNETIC to GRID, you have to subtract the 11°

Navigation Triangulation Remember to adjust for DECLINATION! To go from GRID to MAGNETIC, you added 11°. To go from MAGNETIC to GRID, you have to subtract the 11°

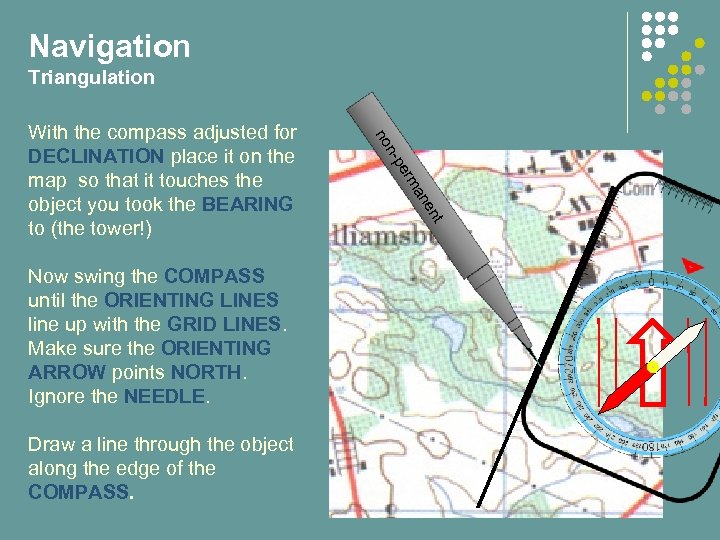

Navigation Triangulation en an erm t Draw a line through the object along the edge of the COMPASS. n-p Now swing the COMPASS until the ORIENTING LINES line up with the GRID LINES. Make sure the ORIENTING ARROW points NORTH. Ignore the NEEDLE. no With the compass adjusted for DECLINATION place it on the map so that it touches the object you took the BEARING to (the tower!)

Navigation Triangulation en an erm t Draw a line through the object along the edge of the COMPASS. n-p Now swing the COMPASS until the ORIENTING LINES line up with the GRID LINES. Make sure the ORIENTING ARROW points NORTH. Ignore the NEEDLE. no With the compass adjusted for DECLINATION place it on the map so that it touches the object you took the BEARING to (the tower!)

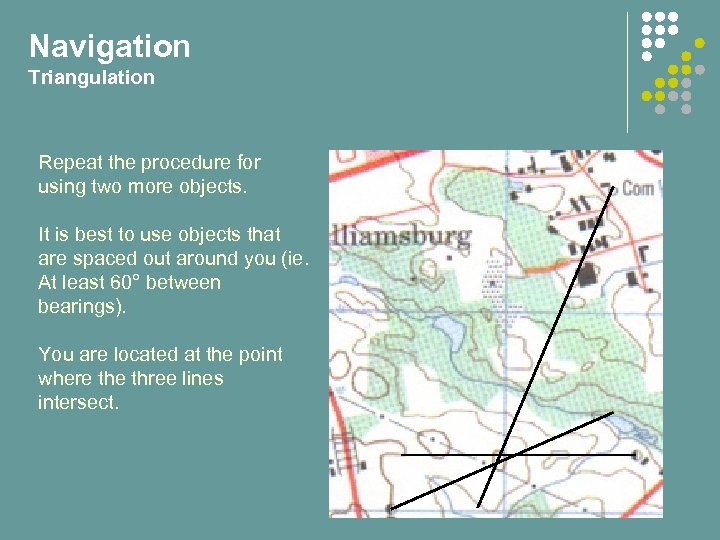

Navigation Triangulation Repeat the procedure for using two more objects. It is best to use objects that are spaced out around you (ie. At least 60° between bearings). You are located at the point where three lines intersect.

Navigation Triangulation Repeat the procedure for using two more objects. It is best to use objects that are spaced out around you (ie. At least 60° between bearings). You are located at the point where three lines intersect.

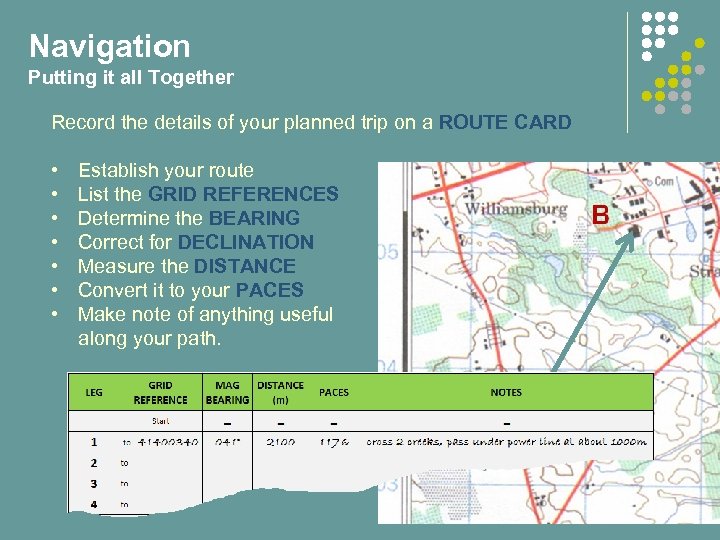

Navigation Putting it all Together Record the details of your planned trip on a ROUTE CARD • Establish your route • List the GRID REFERENCES • Determine the BEARING • Correct for DECLINATION • Measure the DISTANCE • Convert it to your PACES • Make note of anything useful along your path.

Navigation Putting it all Together Record the details of your planned trip on a ROUTE CARD • Establish your route • List the GRID REFERENCES • Determine the BEARING • Correct for DECLINATION • Measure the DISTANCE • Convert it to your PACES • Make note of anything useful along your path.

Navigation Putting it all Together Things to keep in mind while navigating: • Keep the COMPASS level so the NEEDLE can rotate • Keep away from metal! • Be aware of magnetic anomalies in the area you are hiking (like large amounts of iron bearing rock!) • Don’t constantly stare at the COMPASS while you walk…you may be surprised what you trip over or fall off of! • Be aware of your general surroundings. For example…in the morning the sun should be in the EAST…not the WEST.

Navigation Putting it all Together Things to keep in mind while navigating: • Keep the COMPASS level so the NEEDLE can rotate • Keep away from metal! • Be aware of magnetic anomalies in the area you are hiking (like large amounts of iron bearing rock!) • Don’t constantly stare at the COMPASS while you walk…you may be surprised what you trip over or fall off of! • Be aware of your general surroundings. For example…in the morning the sun should be in the EAST…not the WEST.

Introduction to Map and Compass End of Part 4 Do QUIZ 4 now.

Introduction to Map and Compass End of Part 4 Do QUIZ 4 now.