Introduction to Forensic Linguistics_Lecture1.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 28

Introduction to Forensic Linguistics Roger W. Shuy: “Forensic linguistics is the intersection of law and language”. John Olsson: “Forensic linguistics is the application of linguistics to legal issues”. Alison Johnson: “Forensic linguistics is an applied and multidisciplinary field focusing on language in legal setting”. David Crystal: “Forensic linguistics is the use of linguistic techniques to investigate crimes in which language data constitute part of evidence”.

Introduction to Forensic Linguistics Roger W. Shuy: “Forensic linguistics is the intersection of law and language”. John Olsson: “Forensic linguistics is the application of linguistics to legal issues”. Alison Johnson: “Forensic linguistics is an applied and multidisciplinary field focusing on language in legal setting”. David Crystal: “Forensic linguistics is the use of linguistic techniques to investigate crimes in which language data constitute part of evidence”.

Lecture #1. The Foundations of Forensic Linguistics. Points for Discussion: • Forensic Linguistics as a Branch of Applied Linguistics • A Brief History of Forensic Linguistics • The Areas Directly Related to Forensic Linguistics

Lecture #1. The Foundations of Forensic Linguistics. Points for Discussion: • Forensic Linguistics as a Branch of Applied Linguistics • A Brief History of Forensic Linguistics • The Areas Directly Related to Forensic Linguistics

Consider the following historical occasions: • 70 BC - Gaius Verres, a Roman magistrate, was sent into voluntary exile after Marcus Tullius Cicero, acting as his prosecutor, gave a succinct presentation of the evidence accompanied by witness statements instead of a traditional long opening speech complete with intricate arguments and a lengthy presentation of evidence. • December 28, 1170 – Assassination of Thomas Beckett, the Archbishop of Canterbury after Henry II, King of England, cried out in the presence of several of his knights, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest? ” • January 17, 1998 - William Jefferson Clinton, 42 th US President, answering a question during his deposition in a sexual harassment lawsuit stated that he “[had] never had sexual relations with [Monica Lewinski]". Seven months later, during his grand jury testimony, he acknowledged “inappropriate intimate contact” with her but explained that it did not constitute part of a sexual relationship in his understanding of the term.

Consider the following historical occasions: • 70 BC - Gaius Verres, a Roman magistrate, was sent into voluntary exile after Marcus Tullius Cicero, acting as his prosecutor, gave a succinct presentation of the evidence accompanied by witness statements instead of a traditional long opening speech complete with intricate arguments and a lengthy presentation of evidence. • December 28, 1170 – Assassination of Thomas Beckett, the Archbishop of Canterbury after Henry II, King of England, cried out in the presence of several of his knights, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest? ” • January 17, 1998 - William Jefferson Clinton, 42 th US President, answering a question during his deposition in a sexual harassment lawsuit stated that he “[had] never had sexual relations with [Monica Lewinski]". Seven months later, during his grand jury testimony, he acknowledged “inappropriate intimate contact” with her but explained that it did not constitute part of a sexual relationship in his understanding of the term.

• - Did the style of Cicero’s speech influence the outcome of Verres’ trial? • - Was Henry II guilty of incitement to murder? • - What is the meaning of the term "sexual relations"?

• - Did the style of Cicero’s speech influence the outcome of Verres’ trial? • - Was Henry II guilty of incitement to murder? • - What is the meaning of the term "sexual relations"?

The origin of the word ‘forensic’ forensic (adj. ) "pertaining to or suitable for courts of law, " 1650 s, from L. forensis "of a forum, place of assembly, " from forum "public place" (see forum). Used in sense of "pertaining to legal trials, " as in forensic medicine (1845). Related: Forensical (1580 s). Online Etymology Dictionary

The origin of the word ‘forensic’ forensic (adj. ) "pertaining to or suitable for courts of law, " 1650 s, from L. forensis "of a forum, place of assembly, " from forum "public place" (see forum). Used in sense of "pertaining to legal trials, " as in forensic medicine (1845). Related: Forensical (1580 s). Online Etymology Dictionary

The birth of Forensic linguistics • Svartvik, J. 1968. The Evans Statements: A Case for Forensic Linguistics. Göteborg: University of Göteborg. • Philbrick; Frederick A. 1949. Language and the Law: the Semantics of Forensic English. New York: Mac. Millan.

The birth of Forensic linguistics • Svartvik, J. 1968. The Evans Statements: A Case for Forensic Linguistics. Göteborg: University of Göteborg. • Philbrick; Frederick A. 1949. Language and the Law: the Semantics of Forensic English. New York: Mac. Millan.

Beginnings • US and Canada (60’s, 70’s and 80’s): - Lawyers, judicial police and other professional people devoted to the investigation of crime, had been requesting linguists their expertise in relation to issues related to language and the law. • Europe: - Pioneer studies on forensic linguistics can be traced back to 1985. - Primarily in Birmingham. - Experts were called in court to contribute their expertise in authorship attribution both of spoken and written texts.

Beginnings • US and Canada (60’s, 70’s and 80’s): - Lawyers, judicial police and other professional people devoted to the investigation of crime, had been requesting linguists their expertise in relation to issues related to language and the law. • Europe: - Pioneer studies on forensic linguistics can be traced back to 1985. - Primarily in Birmingham. - Experts were called in court to contribute their expertise in authorship attribution both of spoken and written texts.

Prior to the founding of the IAFL • 1988: two-day conference in FL, The Bunderskriminnalamt (BKA). Wiesbaden, Germany. • 1989: Conferences on forensic handwriting analysis, with FL presentations. Mannheim University, Germany. • 1990 and 1991: Conferences in York on forensic phonetics and linguistics. The University of York. UK. • 1990, 1991, 1992 and beyond: GAL, the German Applied Linguistics Association, had a session ("Arbeitskreis") on FL. Göttingen, Mainz and Saarbrücken universities, respectively. Germany. • 20 -22 March 1992: First British Seminar on FL at the University of Birmingham, with delegates from Australia, Brazil, Eire, Holland, Greece, Ukraine and Germany as well as the U. K. Consensus that an international association was needed; from this seminar the IAFL was born. UK. • 14 November 1992: One day seminar (Second British Seminar on FL). Birmingham. UK.

Prior to the founding of the IAFL • 1988: two-day conference in FL, The Bunderskriminnalamt (BKA). Wiesbaden, Germany. • 1989: Conferences on forensic handwriting analysis, with FL presentations. Mannheim University, Germany. • 1990 and 1991: Conferences in York on forensic phonetics and linguistics. The University of York. UK. • 1990, 1991, 1992 and beyond: GAL, the German Applied Linguistics Association, had a session ("Arbeitskreis") on FL. Göttingen, Mainz and Saarbrücken universities, respectively. Germany. • 20 -22 March 1992: First British Seminar on FL at the University of Birmingham, with delegates from Australia, Brazil, Eire, Holland, Greece, Ukraine and Germany as well as the U. K. Consensus that an international association was needed; from this seminar the IAFL was born. UK. • 14 November 1992: One day seminar (Second British Seminar on FL). Birmingham. UK.

Forceful emergence in the 90’s • The experts’ performance became more professionalized; • Outstanding increase in the publication of articles and chapters in a number of forensic linguistics topics, whose content was much more methodologically grounded than before; • The founding of the International Association of Forensic Phonetics (now named the International Association of Forensic Phonetics and Acoustics) took place in 1991. • The International Association of Forensic Linguists was founded in 1992. Other associations: Chinese Association of FL (1999). • A FL journal was created in 1994, whose title underwent several changes and had different publishers. It started as Forensic Linguistics. The International Journal of Speech Language and the Law (Blackwell 19941996; The University of Birmingham Press 1997 -2002), then changed into its present name: The International Journal of Speech Language and the Law (The University of Birmingham Press 2003 -2005; Equinox 2006 -)

Forceful emergence in the 90’s • The experts’ performance became more professionalized; • Outstanding increase in the publication of articles and chapters in a number of forensic linguistics topics, whose content was much more methodologically grounded than before; • The founding of the International Association of Forensic Phonetics (now named the International Association of Forensic Phonetics and Acoustics) took place in 1991. • The International Association of Forensic Linguists was founded in 1992. Other associations: Chinese Association of FL (1999). • A FL journal was created in 1994, whose title underwent several changes and had different publishers. It started as Forensic Linguistics. The International Journal of Speech Language and the Law (Blackwell 19941996; The University of Birmingham Press 1997 -2002), then changed into its present name: The International Journal of Speech Language and the Law (The University of Birmingham Press 2003 -2005; Equinox 2006 -)

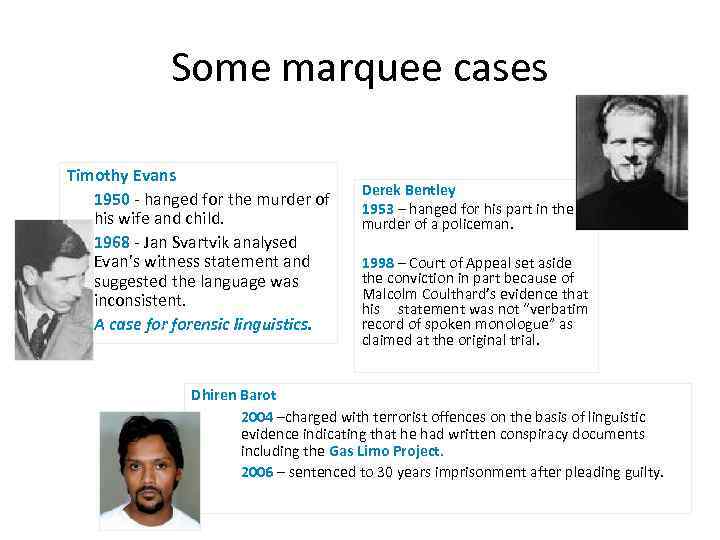

Some marquee cases Timothy Evans 1950 - hanged for the murder of his wife and child. 1968 - Jan Svartvik analysed Evan’s witness statement and suggested the language was inconsistent. A case forensic linguistics. Derek Bentley 1953 – hanged for his part in the murder of a policeman. 1998 – Court of Appeal set aside the conviction in part because of Malcolm Coulthard’s evidence that his statement was not “verbatim record of spoken monologue” as claimed at the original trial. Dhiren Barot 2004 –charged with terrorist offences on the basis of linguistic evidence indicating that he had written conspiracy documents including the Gas Limo Project. 2006 – sentenced to 30 years imprisonment after pleading guilty.

Some marquee cases Timothy Evans 1950 - hanged for the murder of his wife and child. 1968 - Jan Svartvik analysed Evan’s witness statement and suggested the language was inconsistent. A case forensic linguistics. Derek Bentley 1953 – hanged for his part in the murder of a policeman. 1998 – Court of Appeal set aside the conviction in part because of Malcolm Coulthard’s evidence that his statement was not “verbatim record of spoken monologue” as claimed at the original trial. Dhiren Barot 2004 –charged with terrorist offences on the basis of linguistic evidence indicating that he had written conspiracy documents including the Gas Limo Project. 2006 – sentenced to 30 years imprisonment after pleading guilty.

‘Forensic linguistics’ appears to be functioning as an umbrella term referring to research and practice in all those areas where legal and linguistic interests converge. Forensic linguistics is concerned with the role, shape and evidential value of language in legal and forensic settings.

‘Forensic linguistics’ appears to be functioning as an umbrella term referring to research and practice in all those areas where legal and linguistic interests converge. Forensic linguistics is concerned with the role, shape and evidential value of language in legal and forensic settings.

Areas of Forensic Linguistics -organisation of interaction in legal settings (e. g. in police interviews), -speech style in the courtroom (e. g. structure of cross-examination, jury instructions, summing-up), -structure and semantics of legal instruments, -legal terminology, -legal translation and interpreting, -comprehensibility of legal instruments, e. g. the police caution and temporary restraining orders, -language and disadvantage before the law, -linguistic minorities and linguistic human rights, -linguistic evidence in asylum cases, -forensic authorship analysis, -analysis of contested meanings in e. g. trade name disputes or threats to harm and/or to kill, -forensic dialectology.

Areas of Forensic Linguistics -organisation of interaction in legal settings (e. g. in police interviews), -speech style in the courtroom (e. g. structure of cross-examination, jury instructions, summing-up), -structure and semantics of legal instruments, -legal terminology, -legal translation and interpreting, -comprehensibility of legal instruments, e. g. the police caution and temporary restraining orders, -language and disadvantage before the law, -linguistic minorities and linguistic human rights, -linguistic evidence in asylum cases, -forensic authorship analysis, -analysis of contested meanings in e. g. trade name disputes or threats to harm and/or to kill, -forensic dialectology.

Areas in Forensic Linguistics according to the structure and function of language

Areas in Forensic Linguistics according to the structure and function of language

Auditory Phonetics Auditory phonetics is the study of language sounds based on what is heard and interpreted by the human listener, i. e. , the aural–perceptual characteristics of speech. The primary areas of auditory research in forensic phonetics are speaker discrimination and identification by victims and witnesses, voice perception, discrimination, imitation, and disguise, and identification of class characteristics of speakers, including first-language interference, regional or social accent and dialect, and speaker age.

Auditory Phonetics Auditory phonetics is the study of language sounds based on what is heard and interpreted by the human listener, i. e. , the aural–perceptual characteristics of speech. The primary areas of auditory research in forensic phonetics are speaker discrimination and identification by victims and witnesses, voice perception, discrimination, imitation, and disguise, and identification of class characteristics of speakers, including first-language interference, regional or social accent and dialect, and speaker age.

Acoustic Phonetics Acoustic phonetics is the study of the physical characteristics of speech sounds as they leave their source (the speaker), move into the air, and gradually dissipate. The primary area of acoustic analysis in forensic phonetics is speaker identification, but many studies have also been done to identify class characteristics of speakers, including physical height and weight, regional, social, or language group, voice and accent disguise, effect of intoxication on speech, and technical aspects of speech samples and recordings.

Acoustic Phonetics Acoustic phonetics is the study of the physical characteristics of speech sounds as they leave their source (the speaker), move into the air, and gradually dissipate. The primary area of acoustic analysis in forensic phonetics is speaker identification, but many studies have also been done to identify class characteristics of speakers, including physical height and weight, regional, social, or language group, voice and accent disguise, effect of intoxication on speech, and technical aspects of speech samples and recordings.

Semantics: Interpretation of Expressed Meaning Semantics is the study of meaning as expressed by words, phrases, sentences, or texts. The focus of semantic analysis in forensic contexts is on the comprehensibility and interpretation of language that is difficult to understand. Some studies combine the semantic and pragmatic approaches to meaning interpretation. Primary areas of research in forensic semantics are the interpretation of words, phrases, sentences, and texts, ambiguity in texts and laws, and interpretation of meaning in spoken discourse, such as reading of rights and police warnings, police interviews, and jury instructions

Semantics: Interpretation of Expressed Meaning Semantics is the study of meaning as expressed by words, phrases, sentences, or texts. The focus of semantic analysis in forensic contexts is on the comprehensibility and interpretation of language that is difficult to understand. Some studies combine the semantic and pragmatic approaches to meaning interpretation. Primary areas of research in forensic semantics are the interpretation of words, phrases, sentences, and texts, ambiguity in texts and laws, and interpretation of meaning in spoken discourse, such as reading of rights and police warnings, police interviews, and jury instructions

Discourse and Pragmatics: Interpretation of Inferred Meaning Analysis of discourse is the study of units of language larger than the sentence, such as narratives and conversations. Discourse in spoken and written language can take many forms, especially in conversations tied to specific social contexts. Analysis of a speaker’s intended meaning in actual language use is the study of pragmatics. Pragmatics is important forensic purposes because speakers and writers do not always directly match their words with the meaning that they intend to convey. Primary areas of discourse and pragmatics include analysis of spoken and written language, study of the discourse of specific contexts, such as dictation, conversations, hearings, etc. , the language of the courtroom, i. e. , of lawyers, clients, questioning, and jury instructions, and language of specific speech acts, such as threats, promises, warnings, etc.

Discourse and Pragmatics: Interpretation of Inferred Meaning Analysis of discourse is the study of units of language larger than the sentence, such as narratives and conversations. Discourse in spoken and written language can take many forms, especially in conversations tied to specific social contexts. Analysis of a speaker’s intended meaning in actual language use is the study of pragmatics. Pragmatics is important forensic purposes because speakers and writers do not always directly match their words with the meaning that they intend to convey. Primary areas of discourse and pragmatics include analysis of spoken and written language, study of the discourse of specific contexts, such as dictation, conversations, hearings, etc. , the language of the courtroom, i. e. , of lawyers, clients, questioning, and jury instructions, and language of specific speech acts, such as threats, promises, warnings, etc.

Stylistics and Questioned Authorship • The focus of forensic stylistics is author identification of questioned writings. • Linguistic stylistics uses two approaches to authorship identification: qualitative and quantitative. • The work is qualitative when features of writing are identified and then described as being characteristic of an author. • The work is quantitative when certain indicators are identified and then measured in some way, e. g. , their relative frequency of occurrence in a given set of writings. Certain quantitative methods are referred to as stylometry.

Stylistics and Questioned Authorship • The focus of forensic stylistics is author identification of questioned writings. • Linguistic stylistics uses two approaches to authorship identification: qualitative and quantitative. • The work is qualitative when features of writing are identified and then described as being characteristic of an author. • The work is quantitative when certain indicators are identified and then measured in some way, e. g. , their relative frequency of occurrence in a given set of writings. Certain quantitative methods are referred to as stylometry.

• Language of the Law • Language of the Courtroom • Interpretation and Translation

• Language of the Law • Language of the Courtroom • Interpretation and Translation

Areas Directly Related to Forensic Linguistics Document Examination which relies on the scientific study of the physical evidence of a document. Physical traces that assist in the questioned document (QD) examination to uncover the history of a document are left in a number of ways: the writing instrument, i. e. , pen and ink, pencil, typewriter, computer and printer, etc. , the writing surface, such as paper, and information about the writer (or typist), such as physical position and physical, emotional, or mental state.

Areas Directly Related to Forensic Linguistics Document Examination which relies on the scientific study of the physical evidence of a document. Physical traces that assist in the questioned document (QD) examination to uncover the history of a document are left in a number of ways: the writing instrument, i. e. , pen and ink, pencil, typewriter, computer and printer, etc. , the writing surface, such as paper, and information about the writer (or typist), such as physical position and physical, emotional, or mental state.

Software Forensics • Application of stylistic analysis to computer programming • Various metrics, i. e. , style indicators, such as variable names, length of variable names, ratio of global to local variables, layout, upper- vs. lower-case letters, placement of comments, debugging symbols, mean line length, program statements per line, placement of syntactic structures, and ratio of white lines to code lines, etc. • Computer science professors suspicious of plagiarism are using software programs to identify suspiciously similar strings of code in programming assignments.

Software Forensics • Application of stylistic analysis to computer programming • Various metrics, i. e. , style indicators, such as variable names, length of variable names, ratio of global to local variables, layout, upper- vs. lower-case letters, placement of comments, debugging symbols, mean line length, program statements per line, placement of syntactic structures, and ratio of white lines to code lines, etc. • Computer science professors suspicious of plagiarism are using software programs to identify suspiciously similar strings of code in programming assignments.

Semiotics • Semiotics is the study of communication and language as systems of signs and symbols. • Language is an example of a code with both verbal and nonverbal signs. • Speakers and writers encode, and listeners and readers decode the system.

Semiotics • Semiotics is the study of communication and language as systems of signs and symbols. • Language is an example of a code with both verbal and nonverbal signs. • Speakers and writers encode, and listeners and readers decode the system.

Plagiarism Detection A computer program, designed by University of Virginia physics Professor Louis Bloomfield, is said to take a so-called “digital fingerprint” of a student’s paper, then searches the Internet and other databases for like language.

Plagiarism Detection A computer program, designed by University of Virginia physics Professor Louis Bloomfield, is said to take a so-called “digital fingerprint” of a student’s paper, then searches the Internet and other databases for like language.

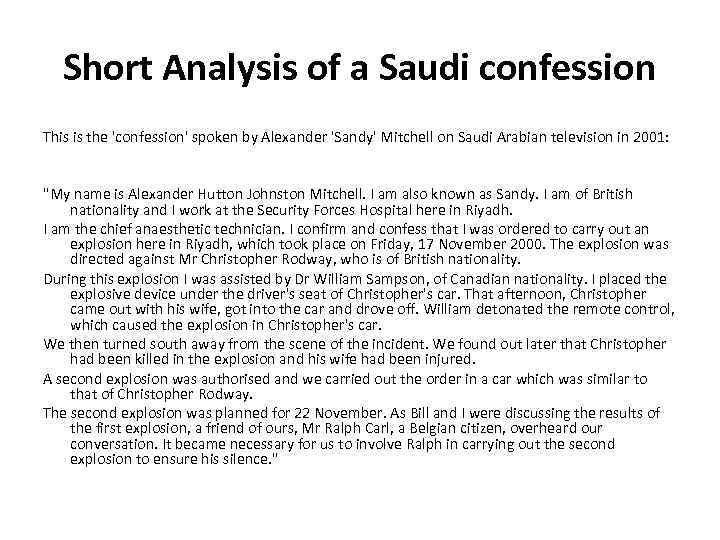

Short Analysis of a Saudi confession This is the 'confession' spoken by Alexander 'Sandy' Mitchell on Saudi Arabian television in 2001: "My name is Alexander Hutton Johnston Mitchell. I am also known as Sandy. I am of British nationality and I work at the Security Forces Hospital here in Riyadh. I am the chief anaesthetic technician. I confirm and confess that I was ordered to carry out an explosion here in Riyadh, which took place on Friday, 17 November 2000. The explosion was directed against Mr Christopher Rodway, who is of British nationality. During this explosion I was assisted by Dr William Sampson, of Canadian nationality. I placed the explosive device under the driver's seat of Christopher's car. That afternoon, Christopher came out with his wife, got into the car and drove off. William detonated the remote control, which caused the explosion in Christopher's car. We then turned south away from the scene of the incident. We found out later that Christopher had been killed in the explosion and his wife had been injured. A second explosion was authorised and we carried out the order in a car which was similar to that of Christopher Rodway. The second explosion was planned for 22 November. As Bill and I were discussing the results of the first explosion, a friend of ours, Mr Ralph Carl, a Belgian citizen, overheard our conversation. It became necessary for us to involve Ralph in carrying out the second explosion to ensure his silence. "

Short Analysis of a Saudi confession This is the 'confession' spoken by Alexander 'Sandy' Mitchell on Saudi Arabian television in 2001: "My name is Alexander Hutton Johnston Mitchell. I am also known as Sandy. I am of British nationality and I work at the Security Forces Hospital here in Riyadh. I am the chief anaesthetic technician. I confirm and confess that I was ordered to carry out an explosion here in Riyadh, which took place on Friday, 17 November 2000. The explosion was directed against Mr Christopher Rodway, who is of British nationality. During this explosion I was assisted by Dr William Sampson, of Canadian nationality. I placed the explosive device under the driver's seat of Christopher's car. That afternoon, Christopher came out with his wife, got into the car and drove off. William detonated the remote control, which caused the explosion in Christopher's car. We then turned south away from the scene of the incident. We found out later that Christopher had been killed in the explosion and his wife had been injured. A second explosion was authorised and we carried out the order in a car which was similar to that of Christopher Rodway. The second explosion was planned for 22 November. As Bill and I were discussing the results of the first explosion, a friend of ours, Mr Ralph Carl, a Belgian citizen, overheard our conversation. It became necessary for us to involve Ralph in carrying out the second explosion to ensure his silence. "

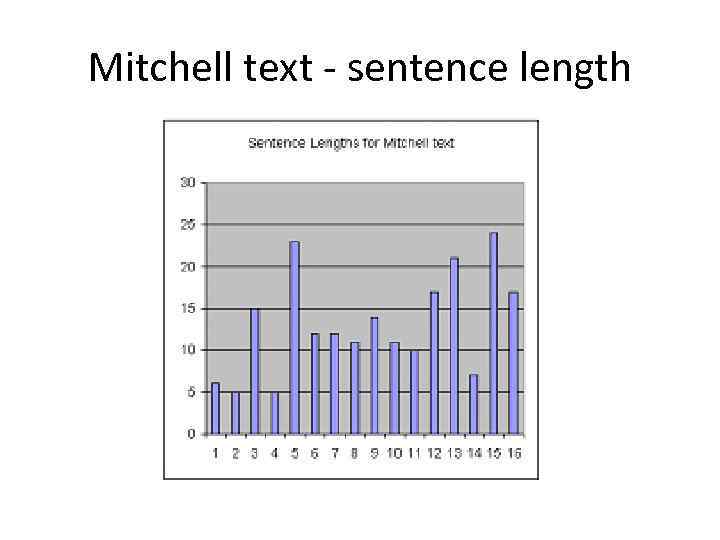

Mitchell text - sentence length

Mitchell text - sentence length

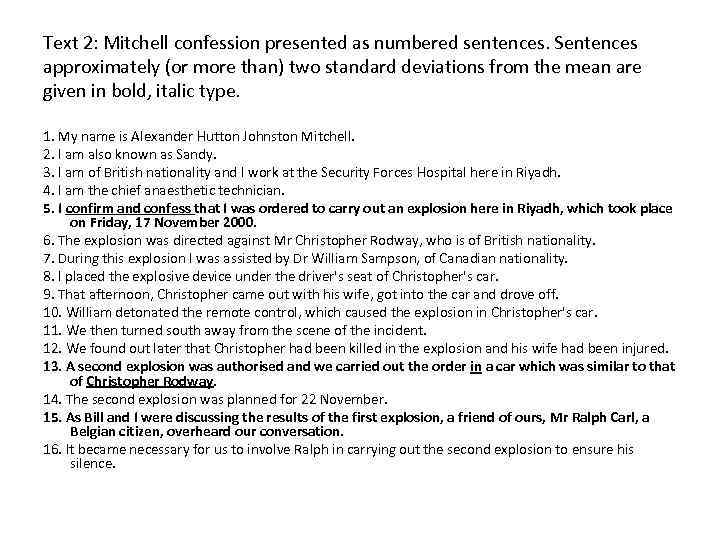

Text 2: Mitchell confession presented as numbered sentences. Sentences approximately (or more than) two standard deviations from the mean are given in bold, italic type. 1. My name is Alexander Hutton Johnston Mitchell. 2. I am also known as Sandy. 3. I am of British nationality and I work at the Security Forces Hospital here in Riyadh. 4. I am the chief anaesthetic technician. 5. I confirm and confess that I was ordered to carry out an explosion here in Riyadh, which took place on Friday, 17 November 2000. 6. The explosion was directed against Mr Christopher Rodway, who is of British nationality. 7. During this explosion I was assisted by Dr William Sampson, of Canadian nationality. 8. I placed the explosive device under the driver's seat of Christopher's car. 9. That afternoon, Christopher came out with his wife, got into the car and drove off. 10. William detonated the remote control, which caused the explosion in Christopher's car. 11. We then turned south away from the scene of the incident. 12. We found out later that Christopher had been killed in the explosion and his wife had been injured. 13. A second explosion was authorised and we carried out the order in a car which was similar to that of Christopher Rodway. 14. The second explosion was planned for 22 November. 15. As Bill and I were discussing the results of the first explosion, a friend of ours, Mr Ralph Carl, a Belgian citizen, overheard our conversation. 16. It became necessary for us to involve Ralph in carrying out the second explosion to ensure his silence.

Text 2: Mitchell confession presented as numbered sentences. Sentences approximately (or more than) two standard deviations from the mean are given in bold, italic type. 1. My name is Alexander Hutton Johnston Mitchell. 2. I am also known as Sandy. 3. I am of British nationality and I work at the Security Forces Hospital here in Riyadh. 4. I am the chief anaesthetic technician. 5. I confirm and confess that I was ordered to carry out an explosion here in Riyadh, which took place on Friday, 17 November 2000. 6. The explosion was directed against Mr Christopher Rodway, who is of British nationality. 7. During this explosion I was assisted by Dr William Sampson, of Canadian nationality. 8. I placed the explosive device under the driver's seat of Christopher's car. 9. That afternoon, Christopher came out with his wife, got into the car and drove off. 10. William detonated the remote control, which caused the explosion in Christopher's car. 11. We then turned south away from the scene of the incident. 12. We found out later that Christopher had been killed in the explosion and his wife had been injured. 13. A second explosion was authorised and we carried out the order in a car which was similar to that of Christopher Rodway. 14. The second explosion was planned for 22 November. 15. As Bill and I were discussing the results of the first explosion, a friend of ours, Mr Ralph Carl, a Belgian citizen, overheard our conversation. 16. It became necessary for us to involve Ralph in carrying out the second explosion to ensure his silence.

Recommended reading • Forensic linguistics: advances in forensic stylistics/Gerald R. Mc. Menamin, Dongdoo Choi. – CRC Press, 2002. – pp. 85 -107. • Forensic linguistics: an introduction to language, crime, and the law/John Olsson. – Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004. – pp. 1 -16.

Recommended reading • Forensic linguistics: advances in forensic stylistics/Gerald R. Mc. Menamin, Dongdoo Choi. – CRC Press, 2002. – pp. 85 -107. • Forensic linguistics: an introduction to language, crime, and the law/John Olsson. – Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004. – pp. 1 -16.

ASSIGNMENTS • • • Visit the site of International Association of Forensic Linguists http: //www. iafl. org/ What are research areas of Forensic Linguistics? Read the following publications and be ready to discuss them: “Forensic linguists becoming more important part of criminal investigation” by Dahl Dick (http: //www. robertleonardassociates. com/PDF/Lawyers. USA_7 april 08. pdf). What are practice areas forensic linguists are involved in? Words on Trial: Can linguists solve crimes that stump the police? by Jack Hitt (http: //www. hofstra. edu/pdf/Academics/Colleges/HCLAS/flp_News. Day_Word On. Trial. pdf) Watch Dr Malcolm Coulthard's Inaugural Lecture "Forensic Linguistics: Linguist as detective & expert witness" (http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=SBrm. MAds. R 8 c)

ASSIGNMENTS • • • Visit the site of International Association of Forensic Linguists http: //www. iafl. org/ What are research areas of Forensic Linguistics? Read the following publications and be ready to discuss them: “Forensic linguists becoming more important part of criminal investigation” by Dahl Dick (http: //www. robertleonardassociates. com/PDF/Lawyers. USA_7 april 08. pdf). What are practice areas forensic linguists are involved in? Words on Trial: Can linguists solve crimes that stump the police? by Jack Hitt (http: //www. hofstra. edu/pdf/Academics/Colleges/HCLAS/flp_News. Day_Word On. Trial. pdf) Watch Dr Malcolm Coulthard's Inaugural Lecture "Forensic Linguistics: Linguist as detective & expert witness" (http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=SBrm. MAds. R 8 c)