JKranjc_ELT.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 156

Introduction to English legal terminology I. Law Institute, Irkutsk State University 9 -13 Dec. 2013

Introduction to English legal terminology I. Law Institute, Irkutsk State University 9 -13 Dec. 2013

Sources n n n Vanessa Sims, English Law and Terminology, 3. Auflage, Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden 2010 (Lingua Juris, Kompendien zu Recht und Terminologie. Herausgegeben von Ute Goergen, FFA, Universitat Trier) Peter Tiersma, The Nature of Legal Language, http: //www. languageandlaw. org/NATURE. HTM] The article U. S. Court System and some other texts available on the internet

Sources n n n Vanessa Sims, English Law and Terminology, 3. Auflage, Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden 2010 (Lingua Juris, Kompendien zu Recht und Terminologie. Herausgegeben von Ute Goergen, FFA, Universitat Trier) Peter Tiersma, The Nature of Legal Language, http: //www. languageandlaw. org/NATURE. HTM] The article U. S. Court System and some other texts available on the internet

Language and communication The legislator, the lawyer, the client, the judge, all have to use the language as means of communication, whether orally or in writing. The language of law, a 'professional jargon'; The advantage: it enables lawyers to communicate in an effective and efficient way; the disadvantage: lay people are often unable to understand it (especially when the expressions of common language are used in a different meaning.

Language and communication The legislator, the lawyer, the client, the judge, all have to use the language as means of communication, whether orally or in writing. The language of law, a 'professional jargon'; The advantage: it enables lawyers to communicate in an effective and efficient way; the disadvantage: lay people are often unable to understand it (especially when the expressions of common language are used in a different meaning.

Legal terms and their interpretation - - - A legal term has to be interpreted and given a proper, contextual meaning (i. e. in the context of needs, preferences and values) Different tools and methods of statutory interpretation (including traditional canons, purpose and legislative history) The interpretation necessarily implicate into the process the value system of the interpretor, i. e. personal views on what is right and what is wrong. In a way the statutory interpretation is also a (re)evaluation of legal norm concerned.

Legal terms and their interpretation - - - A legal term has to be interpreted and given a proper, contextual meaning (i. e. in the context of needs, preferences and values) Different tools and methods of statutory interpretation (including traditional canons, purpose and legislative history) The interpretation necessarily implicate into the process the value system of the interpretor, i. e. personal views on what is right and what is wrong. In a way the statutory interpretation is also a (re)evaluation of legal norm concerned.

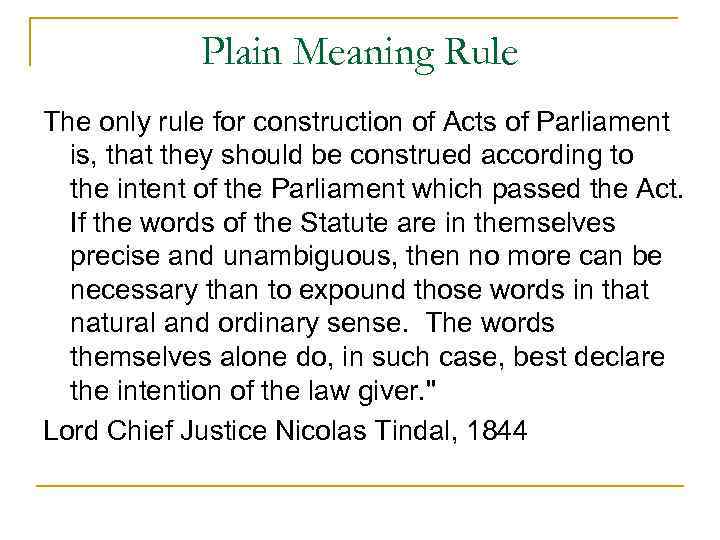

Plain Meaning Rule The only rule for construction of Acts of Parliament is, that they should be construed according to the intent of the Parliament which passed the Act. If the words of the Statute are in themselves precise and unambiguous, then no more can be necessary than to expound those words in that natural and ordinary sense. The words themselves alone do, in such case, best declare the intention of the law giver. " Lord Chief Justice Nicolas Tindal, 1844

Plain Meaning Rule The only rule for construction of Acts of Parliament is, that they should be construed according to the intent of the Parliament which passed the Act. If the words of the Statute are in themselves precise and unambiguous, then no more can be necessary than to expound those words in that natural and ordinary sense. The words themselves alone do, in such case, best declare the intention of the law giver. " Lord Chief Justice Nicolas Tindal, 1844

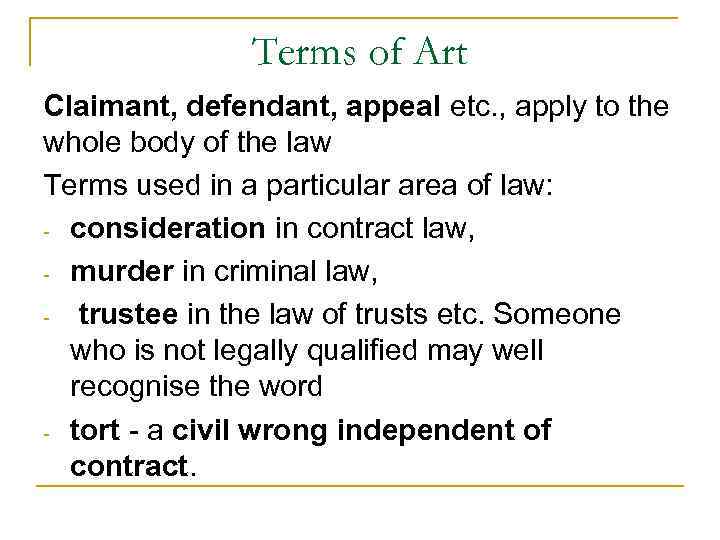

Terms of Art Claimant, defendant, appeal etc. , apply to the whole body of the law Terms used in a particular area of law: - consideration in contract law, - murder in criminal law, - trustee in the law of trusts etc. Someone who is not legally qualified may well recognise the word - tort - a civil wrong independent of contract.

Terms of Art Claimant, defendant, appeal etc. , apply to the whole body of the law Terms used in a particular area of law: - consideration in contract law, - murder in criminal law, - trustee in the law of trusts etc. Someone who is not legally qualified may well recognise the word - tort - a civil wrong independent of contract.

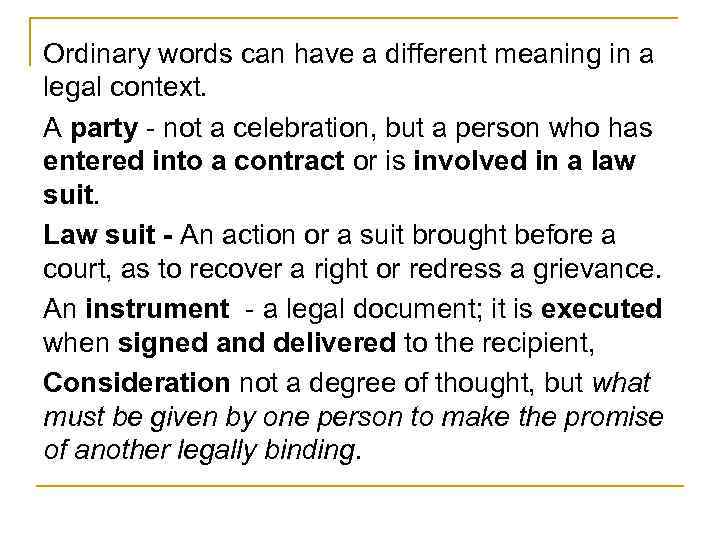

Ordinary words can have a different meaning in a legal context. A party - not a celebration, but a person who has entered into a contract or is involved in a law suit. Law suit - An action or a suit brought before a court, as to recover a right or redress a grievance. An instrument - a legal document; it is executed when signed and delivered to the recipient, Consideration not a degree of thought, but what must be given by one person to make the promise of another legally binding.

Ordinary words can have a different meaning in a legal context. A party - not a celebration, but a person who has entered into a contract or is involved in a law suit. Law suit - An action or a suit brought before a court, as to recover a right or redress a grievance. An instrument - a legal document; it is executed when signed and delivered to the recipient, Consideration not a degree of thought, but what must be given by one person to make the promise of another legally binding.

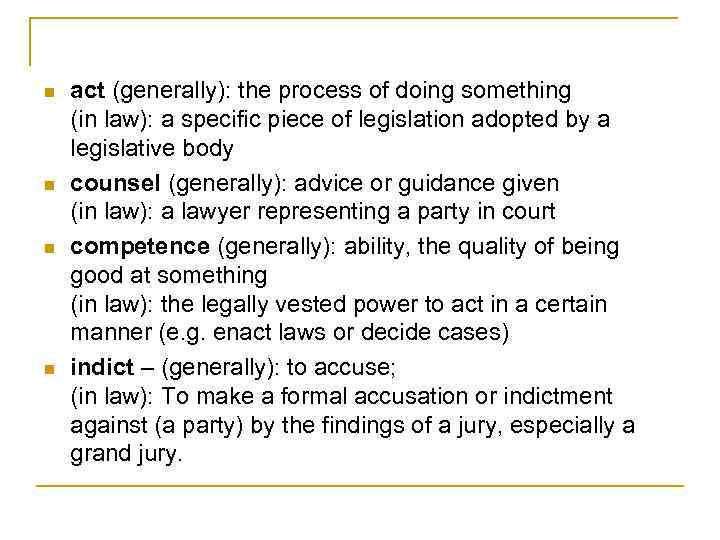

n n act (generally): the process of doing something (in law): a specific piece of legislation adopted by a legislative body counsel (generally): advice or guidance given (in law): a lawyer representing a party in court competence (generally): ability, the quality of being good at something (in law): the legally vested power to act in a certain manner (e. g. enact laws or decide cases) indict – (generally): to accuse; (in law): To make a formal accusation or indictment against (a party) by the findings of a jury, especially a grand jury.

n n act (generally): the process of doing something (in law): a specific piece of legislation adopted by a legislative body counsel (generally): advice or guidance given (in law): a lawyer representing a party in court competence (generally): ability, the quality of being good at something (in law): the legally vested power to act in a certain manner (e. g. enact laws or decide cases) indict – (generally): to accuse; (in law): To make a formal accusation or indictment against (a party) by the findings of a jury, especially a grand jury.

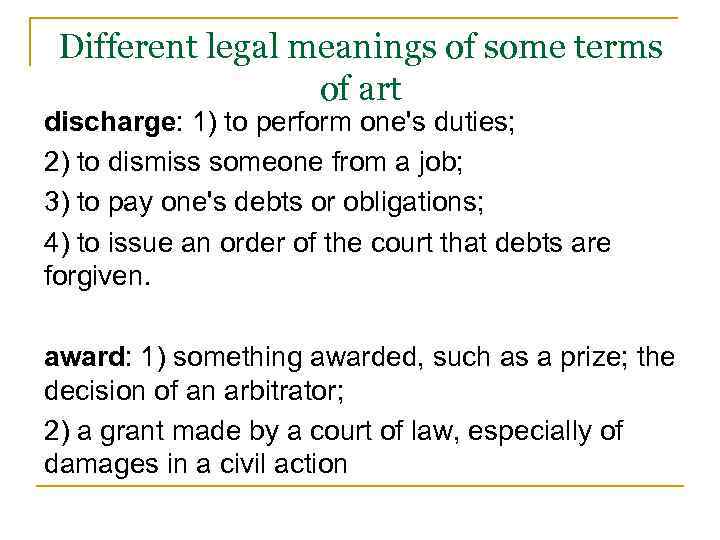

Different legal meanings of some terms of art discharge: 1) to perform one's duties; 2) to dismiss someone from a job; 3) to pay one's debts or obligations; 4) to issue an order of the court that debts are forgiven. award: 1) something awarded, such as a prize; the decision of an arbitrator; 2) a grant made by a court of law, especially of damages in a civil action

Different legal meanings of some terms of art discharge: 1) to perform one's duties; 2) to dismiss someone from a job; 3) to pay one's debts or obligations; 4) to issue an order of the court that debts are forgiven. award: 1) something awarded, such as a prize; the decision of an arbitrator; 2) a grant made by a court of law, especially of damages in a civil action

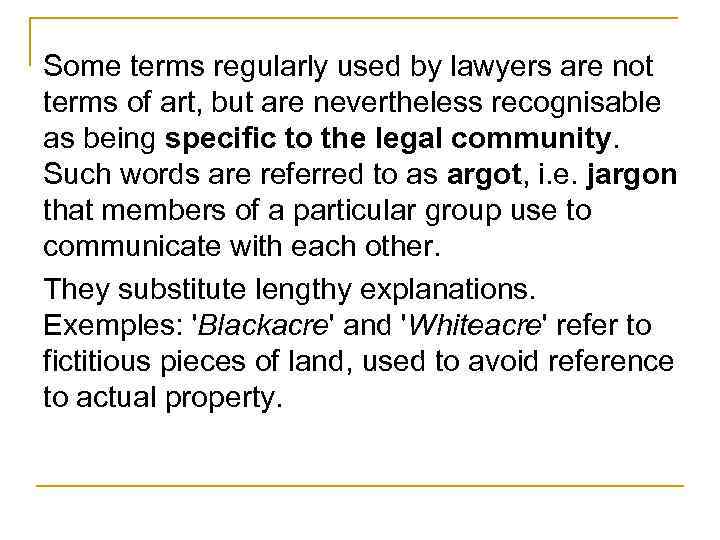

Some terms regularly used by lawyers are not terms of art, but are nevertheless recognisable as being specific to the legal community. Such words are referred to as argot, i. e. jargon that members of a particular group use to communicate with each other. They substitute lengthy explanations. Exemples: 'Blackacre' and 'Whiteacre' refer to fictitious pieces of land, used to avoid reference to actual property.

Some terms regularly used by lawyers are not terms of art, but are nevertheless recognisable as being specific to the legal community. Such words are referred to as argot, i. e. jargon that members of a particular group use to communicate with each other. They substitute lengthy explanations. Exemples: 'Blackacre' and 'Whiteacre' refer to fictitious pieces of land, used to avoid reference to actual property.

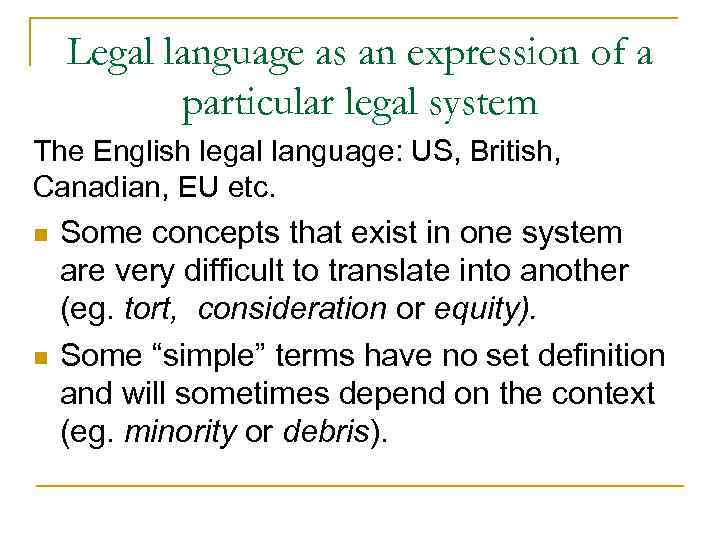

Legal language as an expression of a particular legal system The English legal language: US, British, Canadian, EU etc. n n Some concepts that exist in one system are very difficult to translate into another (eg. tort, consideration or equity). Some “simple” terms have no set definition and will sometimes depend on the context (eg. minority or debris).

Legal language as an expression of a particular legal system The English legal language: US, British, Canadian, EU etc. n n Some concepts that exist in one system are very difficult to translate into another (eg. tort, consideration or equity). Some “simple” terms have no set definition and will sometimes depend on the context (eg. minority or debris).

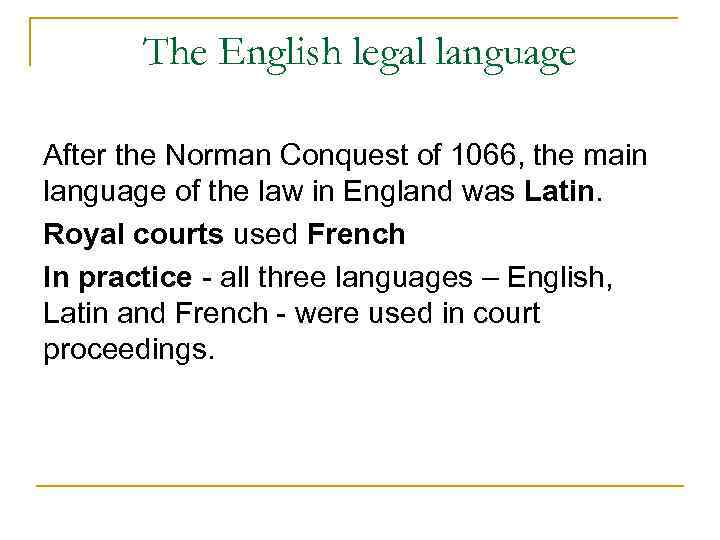

The English legal language After the Norman Conquest of 1066, the main language of the law in England was Latin. Royal courts used French In practice - all three languages – English, Latin and French - were used in court proceedings.

The English legal language After the Norman Conquest of 1066, the main language of the law in England was Latin. Royal courts used French In practice - all three languages – English, Latin and French - were used in court proceedings.

Those, not speaking French, had to state their case and present their evidence in English. Lawyers' arguments and the decision of the court would be in French, and the law report would be in Latin. The judgment had to be translated back into English, so that the parties could understand what had been decided. Legal expressions in all three languages were used simultaneously. Both Latin and French have had a lasting influence on legal English.

Those, not speaking French, had to state their case and present their evidence in English. Lawyers' arguments and the decision of the court would be in French, and the law report would be in Latin. The judgment had to be translated back into English, so that the parties could understand what had been decided. Legal expressions in all three languages were used simultaneously. Both Latin and French have had a lasting influence on legal English.

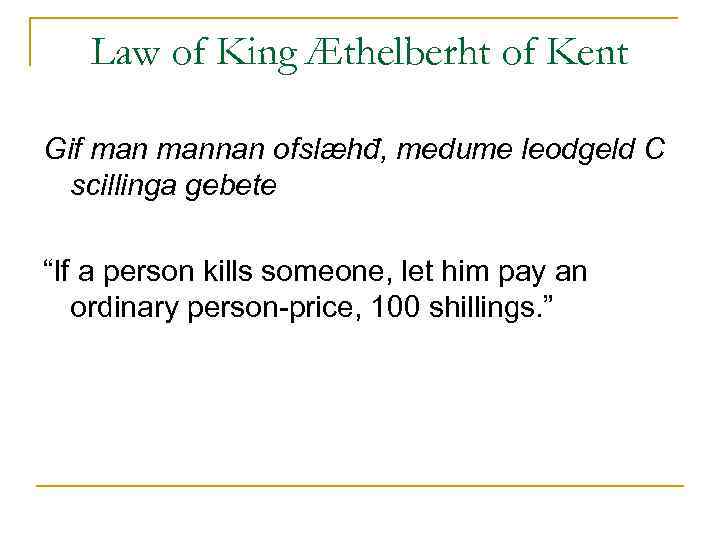

Law of King Æthelberht of Kent Gif mannan ofslæhđ, medume leodgeld C scillinga gebete “If a person kills someone, let him pay an ordinary person-price, 100 shillings. ”

Law of King Æthelberht of Kent Gif mannan ofslæhđ, medume leodgeld C scillinga gebete “If a person kills someone, let him pay an ordinary person-price, 100 shillings. ”

The influence of French was the language of honour, of chivalry, and even of justice, while the far more manly and expressive Anglo-Saxon was abandoned to the use of rustics and hinds, who knew no other … Sir Walter Scott in his novel Ivanhoe

The influence of French was the language of honour, of chivalry, and even of justice, while the far more manly and expressive Anglo-Saxon was abandoned to the use of rustics and hinds, who knew no other … Sir Walter Scott in his novel Ivanhoe

In the beginning, the Normans wrote legal documents in Latin, not French. Around 1275, however, statutes in French began to appear. By 1310 almost all acts of Parliament were in that language. A similar evolution took place with the idiom of the courts. At least by the reign of Edward I, towards the end of the thirteenth century, French had become the language of the royal courts.

In the beginning, the Normans wrote legal documents in Latin, not French. Around 1275, however, statutes in French began to appear. By 1310 almost all acts of Parliament were in that language. A similar evolution took place with the idiom of the courts. At least by the reign of Edward I, towards the end of the thirteenth century, French had become the language of the royal courts.

In 1362 Parliament enacted the Statute of Pleading, condemning French as "unknown in the said Realm" and lamenting that parties in a lawsuit "have no Knowledge nor Understanding of that which is said for them or against them by their Serjeants and other Pleaders. " The statute required that henceforth all pleas be "pleaded, shewed, defended, answered, debated, and judged in the English Tongue. " Ironically, the statute itself was in French!

In 1362 Parliament enacted the Statute of Pleading, condemning French as "unknown in the said Realm" and lamenting that parties in a lawsuit "have no Knowledge nor Understanding of that which is said for them or against them by their Serjeants and other Pleaders. " The statute required that henceforth all pleas be "pleaded, shewed, defended, answered, debated, and judged in the English Tongue. " Ironically, the statute itself was in French!

The legal profession seems to have largely ignored this statute. Acts of Parliament did finally switch to English around 1480, but legal treatises and reports of courts cases remained mostly in French throughout the sixteenth century and the first half of the seventeenth.

The legal profession seems to have largely ignored this statute. Acts of Parliament did finally switch to English around 1480, but legal treatises and reports of courts cases remained mostly in French throughout the sixteenth century and the first half of the seventeenth.

The French of lawyers became increasingly corrupt, and its vocabulary more and more limited. By the seventeenth century lawyers were tossing in English words with abandon. A famous case from 1631, in which a condemned prisoner threw a brickbat at the judge. The report noted that he ject un brickbat a le dit justice, que narrowly mist. The judge ordered that the defendant's right arm be amputated and that he be immediatement hange in presence de Court.

The French of lawyers became increasingly corrupt, and its vocabulary more and more limited. By the seventeenth century lawyers were tossing in English words with abandon. A famous case from 1631, in which a condemned prisoner threw a brickbat at the judge. The report noted that he ject un brickbat a le dit justice, que narrowly mist. The judge ordered that the defendant's right arm be amputated and that he be immediatement hange in presence de Court.

Some terms of French origin Appeal, attorney, bailiff, bar, claim, complaint, counsel, court, defendant, demurrer, evidence, indictment, judge, judgment, jury, justice, party, plaintiff, plead, sentence, suit, summon, verdict , voir dire etc.

Some terms of French origin Appeal, attorney, bailiff, bar, claim, complaint, counsel, court, defendant, demurrer, evidence, indictment, judge, judgment, jury, justice, party, plaintiff, plead, sentence, suit, summon, verdict , voir dire etc.

Examples of French influence attorney general, court martial, fee simple absolute, letters testamentary, malice aforethought, and solicitor general. Worlds ending in -ee to indicate the person who was the recipient or object of an action (lessee: "the person leased to"). Lawyers, even today, are coining new words on this pattern, including asylee, condemnee, detainee, expellee and tippee.

Examples of French influence attorney general, court martial, fee simple absolute, letters testamentary, malice aforethought, and solicitor general. Worlds ending in -ee to indicate the person who was the recipient or object of an action (lessee: "the person leased to"). Lawyers, even today, are coining new words on this pattern, including asylee, condemnee, detainee, expellee and tippee.

The legal jargon n n A simple phrase I give you that orange, when written out by a lawyer: I give you all and singular, my estate and interest, right, title, claim and advantage of and in that orange, with all its rind, skin, juice, pulp and pips, and all right and advantage therein, with full power to bite, cut, suck, and otherwise eat the same, or give the same away as fully and effectually as I the said A. B. am now entitled to bite, cut, suck, or otherwise eat the same orange, or give the same away, with or without its rind, skin, juice, pulp, and pips, anything hereinbefore, or hereinafter, or in any other deed, or deeds, instrument or instruments of what nature or kind soever, to the contrary in any wise, notwithstanding.

The legal jargon n n A simple phrase I give you that orange, when written out by a lawyer: I give you all and singular, my estate and interest, right, title, claim and advantage of and in that orange, with all its rind, skin, juice, pulp and pips, and all right and advantage therein, with full power to bite, cut, suck, and otherwise eat the same, or give the same away as fully and effectually as I the said A. B. am now entitled to bite, cut, suck, or otherwise eat the same orange, or give the same away, with or without its rind, skin, juice, pulp, and pips, anything hereinbefore, or hereinafter, or in any other deed, or deeds, instrument or instruments of what nature or kind soever, to the contrary in any wise, notwithstanding.

Bentham: legal language as "an instrument, an iron crow or a pick-lock key, for collecting plunder" - if you strip away all the jargon, "every simpleton is ready to say--What is there in all that? 'Tis just what I should have done myself. " "What better way of preserving a professional monopoly than by locking up your trade secrets in the safe of an unknown tongue? „ David Mellinkoff

Bentham: legal language as "an instrument, an iron crow or a pick-lock key, for collecting plunder" - if you strip away all the jargon, "every simpleton is ready to say--What is there in all that? 'Tis just what I should have done myself. " "What better way of preserving a professional monopoly than by locking up your trade secrets in the safe of an unknown tongue? „ David Mellinkoff

Law does not have a universally accepted definition, but one definition is that law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social (predominantly state) institutions to govern behavior. Religious origins of law (still settling secular matters in some countries – Sharia law or Halakha) Moral codes defining what is moral and immoral are based upon well-defined value systems. They are often the basis of legal codes.

Law does not have a universally accepted definition, but one definition is that law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social (predominantly state) institutions to govern behavior. Religious origins of law (still settling secular matters in some countries – Sharia law or Halakha) Moral codes defining what is moral and immoral are based upon well-defined value systems. They are often the basis of legal codes.

Laws can be made by legislatures - through legislation resulting in statutes, - the executive through decrees and regulations, - or judges through binding precedents (in common law jurisdictions). Private individuals can create legally binding contracts, including (in some jurisdictions) arbitration agreements that exclude the normal court process. n

Laws can be made by legislatures - through legislation resulting in statutes, - the executive through decrees and regulations, - or judges through binding precedents (in common law jurisdictions). Private individuals can create legally binding contracts, including (in some jurisdictions) arbitration agreements that exclude the normal court process. n

n n n Two main areas of Law: Criminal law deals with conduct that is considered harmful to social order. The guilty party is punished (there are different penalties established by law or authority for a crime or offense, e. g. imprisonment , fines). Civil law deals with the private and civilian affairs.

n n n Two main areas of Law: Criminal law deals with conduct that is considered harmful to social order. The guilty party is punished (there are different penalties established by law or authority for a crime or offense, e. g. imprisonment , fines). Civil law deals with the private and civilian affairs.

Contract law regulates contracts, i. e. agreements between two or more parties, enforceable by law. Property law regulates the transfer and title of personal (in common law chattels or personalty, in civil law movable property or movables) and real (immovable property or immovables). Trust law applies to assets held for investment and financial security. Tort law allows claims for compensation if a person's property is harmed. Tort is a civil wrong which unfairly causes someone else to suffer loss or harm resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act, called a tortfeasor.

Contract law regulates contracts, i. e. agreements between two or more parties, enforceable by law. Property law regulates the transfer and title of personal (in common law chattels or personalty, in civil law movable property or movables) and real (immovable property or immovables). Trust law applies to assets held for investment and financial security. Tort law allows claims for compensation if a person's property is harmed. Tort is a civil wrong which unfairly causes someone else to suffer loss or harm resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act, called a tortfeasor.

n n n Constitutional law provides a framework for the creation of law, the protection of human rights and the election of political representatives. Administrative law the body of rules and regulations and orders and decisions created by administrative agencies of government. International law regulates affairs between sovereign states - a set of rules generally regarded and accepted as binding in relations between states and nations. Also called law of nations. .

n n n Constitutional law provides a framework for the creation of law, the protection of human rights and the election of political representatives. Administrative law the body of rules and regulations and orders and decisions created by administrative agencies of government. International law regulates affairs between sovereign states - a set of rules generally regarded and accepted as binding in relations between states and nations. Also called law of nations. .

The Common Law

The Common Law

Common (general meaning) - 'vulgar' or 'ordinary'. Common (legal meaning) – common to all the land. Common law: 1. The law common to all the land (ius commune), i. e. a body of rules that developed in contrast to local customs. 2. The law of the land to be distinguished from specialised areas of law, such as ecclesiastical law, the law merchant and equity.

Common (general meaning) - 'vulgar' or 'ordinary'. Common (legal meaning) – common to all the land. Common law: 1. The law common to all the land (ius commune), i. e. a body of rules that developed in contrast to local customs. 2. The law of the land to be distinguished from specialised areas of law, such as ecclesiastical law, the law merchant and equity.

3. case law, i. e. law created by decisions of the courts as opposed to law created by statute. 4. The legal system which differs significantly from the civil law systems of most continental countries. Civil law systems are centred around codes, while common law systems focus on case law and individual statutes

3. case law, i. e. law created by decisions of the courts as opposed to law created by statute. 4. The legal system which differs significantly from the civil law systems of most continental countries. Civil law systems are centred around codes, while common law systems focus on case law and individual statutes

Common law courts England Wales Curia Regis - king's advisory body (having also advisory and administrative functions) travelled around the country, applying royal justice uniformly throughout the land. Curia Regis was replaced by the common law courts.

Common law courts England Wales Curia Regis - king's advisory body (having also advisory and administrative functions) travelled around the country, applying royal justice uniformly throughout the land. Curia Regis was replaced by the common law courts.

Court of Exchequer (financial and revenue matters), Court of Assize (criminal and civil matters - until 1971), Court of Common Pleas (civil cases, mainly related to land) Court of King's Bench (civil and criminal cases and supervisory function). County courts High Court,

Court of Exchequer (financial and revenue matters), Court of Assize (criminal and civil matters - until 1971), Court of Common Pleas (civil cases, mainly related to land) Court of King's Bench (civil and criminal cases and supervisory function). County courts High Court,

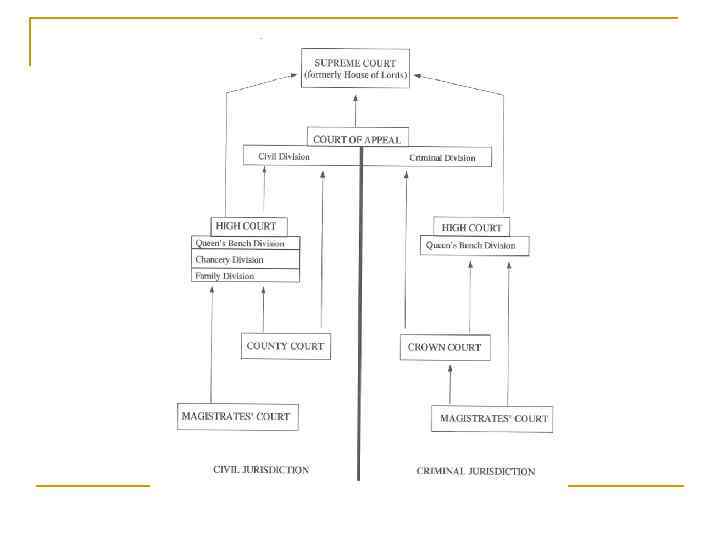

The Court of Appeal deals only with appeals from other courts or tribunals. Two divisions: - Civil Division hears appeals from the High Court and County Court and certain superior tribunals, - - Criminal Division hears only appeals from the Crown Court (connected with a trial on indictment, i. e. for a serious offence). Its decisions are binding on all courts, including itself, apart from the Supreme Court.

The Court of Appeal deals only with appeals from other courts or tribunals. Two divisions: - Civil Division hears appeals from the High Court and County Court and certain superior tribunals, - - Criminal Division hears only appeals from the Crown Court (connected with a trial on indictment, i. e. for a serious offence). Its decisions are binding on all courts, including itself, apart from the Supreme Court.

The High Court of Justice functions both as - Civil court of first instance - a criminal and civil appelate court for cases from the subordinate courts. - It consists of three divisions: the Queen's Bench, the Chancery and the Family divisions - not separate courts, but have somewhat separate procedures and practices adapted to their purposes, each division exercises the jurisdiction of the High Court.

The High Court of Justice functions both as - Civil court of first instance - a criminal and civil appelate court for cases from the subordinate courts. - It consists of three divisions: the Queen's Bench, the Chancery and the Family divisions - not separate courts, but have somewhat separate procedures and practices adapted to their purposes, each division exercises the jurisdiction of the High Court.

n n n The Crown Court a criminal court of both original and appellate jurisdiction handling in addition a limited amount of civil matters both at first instance and on appeal. Established by Courts Act in 1971 to replace Assizes. The Crown Court also hears appeals from Magistrates‘ Courts. It is the only court in to try cases on indictment. When exercising such a role it is a superior court.

n n n The Crown Court a criminal court of both original and appellate jurisdiction handling in addition a limited amount of civil matters both at first instance and on appeal. Established by Courts Act in 1971 to replace Assizes. The Crown Court also hears appeals from Magistrates‘ Courts. It is the only court in to try cases on indictment. When exercising such a role it is a superior court.

A magistrates' court is a lower court, where all the criminal proceedings start. Also some civil matters are decided there, namely family proceedings. They have been reorganized to swiftly and cheaply deliver justice. There are over 360 magistrates' courts in England Wales.

A magistrates' court is a lower court, where all the criminal proceedings start. Also some civil matters are decided there, namely family proceedings. They have been reorganized to swiftly and cheaply deliver justice. There are over 360 magistrates' courts in England Wales.

Family Proceedings Court (FPC) – a Magistrates‘ Court of first instance when members of the family panel sit todealing with family matters (in front of a bench of lay magistrates or a District Judge) Youth courts are presided over by a specially trained subset of experienced adult magistrates or a district judge. Youth magistrates have a wider catalogue of disposals available to them for dealing with young offenders and often hear more serious cases against youths (which for adults would normally be dealt with by the Crown Court).

Family Proceedings Court (FPC) – a Magistrates‘ Court of first instance when members of the family panel sit todealing with family matters (in front of a bench of lay magistrates or a District Judge) Youth courts are presided over by a specially trained subset of experienced adult magistrates or a district judge. Youth magistrates have a wider catalogue of disposals available to them for dealing with young offenders and often hear more serious cases against youths (which for adults would normally be dealt with by the Crown Court).

County courts - statutory courts with a purely civil jurisdiction, sitting in 92 different towns and cities across England Wales. Presided over by either a district or circuit judge and, except in some cases, he sits alone as trier of fact and law without assistance from a jury. Each County court has an area over which certain kinds of jurisdiction—such as actions concerning land or cases concerning children who reside in the area—are exercised. For example, proceedings for possession of land must be started in the county court in whose district the property lies.

County courts - statutory courts with a purely civil jurisdiction, sitting in 92 different towns and cities across England Wales. Presided over by either a district or circuit judge and, except in some cases, he sits alone as trier of fact and law without assistance from a jury. Each County court has an area over which certain kinds of jurisdiction—such as actions concerning land or cases concerning children who reside in the area—are exercised. For example, proceedings for possession of land must be started in the county court in whose district the property lies.

Special courts and tribunals e. g. Employment Tribunal and Employment Appeal Tribunal Coroners' courts - coroners sit to determine the cause of death in situations where people have died in potentially suspicious circumstances, abroad, or in the care of central authority. They also have jurisdiction over treasure trove. Ecclesiastical courts

Special courts and tribunals e. g. Employment Tribunal and Employment Appeal Tribunal Coroners' courts - coroners sit to determine the cause of death in situations where people have died in potentially suspicious circumstances, abroad, or in the care of central authority. They also have jurisdiction over treasure trove. Ecclesiastical courts

Appeal: the party not satisfied with the judgment of a court can ask a higher court to re -examine the decision (appeal against sentence). The appellant - the respondent. Cross-appeals - both parties wish to appeal (e. g. , one party because he has been ordered to pay damages, and the other because he thinks the damages awarded are too low).

Appeal: the party not satisfied with the judgment of a court can ask a higher court to re -examine the decision (appeal against sentence). The appellant - the respondent. Cross-appeals - both parties wish to appeal (e. g. , one party because he has been ordered to pay damages, and the other because he thinks the damages awarded are too low).

Permission to appeal: the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 changed the terminology for civil cases from 'leave to appeal' to 'permission to appeal'. The terminology in criminal cases remains unchanged. Appeal on point of fact / on point of law: a point of fact is determined by evidence. Facts are usually determined in the court of first instance, and appeals on point of fact are limited. The higher appeal courts do not normally interfere with a lower court's finding of fact; they concern themselves with appeals on point of law only.

Permission to appeal: the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 changed the terminology for civil cases from 'leave to appeal' to 'permission to appeal'. The terminology in criminal cases remains unchanged. Appeal on point of fact / on point of law: a point of fact is determined by evidence. Facts are usually determined in the court of first instance, and appeals on point of fact are limited. The higher appeal courts do not normally interfere with a lower court's finding of fact; they concern themselves with appeals on point of law only.

Tribunal: a body which exercises judicial or quasi-judicial functions outside the normal hierarchy of courts. Tribunals usually comprise both lawyers and lay persons with expert knowledge, and have been set up in a number of different (often very technical) areas; employment tribunals, for example, deal with employment disputes. The main advantages of tribunals compared to the courts are that the proceedings are cheaper and speedier (for example, parties before a tribunal often appear without legal representation), and that tribunals have more specialist knowledge.

Tribunal: a body which exercises judicial or quasi-judicial functions outside the normal hierarchy of courts. Tribunals usually comprise both lawyers and lay persons with expert knowledge, and have been set up in a number of different (often very technical) areas; employment tribunals, for example, deal with employment disputes. The main advantages of tribunals compared to the courts are that the proceedings are cheaper and speedier (for example, parties before a tribunal often appear without legal representation), and that tribunals have more specialist knowledge.

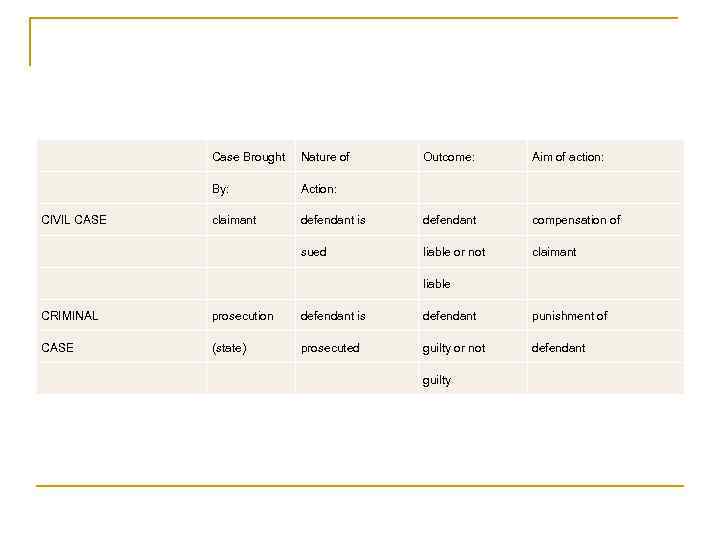

Case Brought Nature of By: Action: claimant defendant is defendant compensation of sued liable or not claimant CIVIL CASE Outcome: Aim of action: liable CRIMINAL defendant is defendant punishment of CASE prosecution (state) prosecuted guilty or not defendant guilty

Case Brought Nature of By: Action: claimant defendant is defendant compensation of sued liable or not claimant CIVIL CASE Outcome: Aim of action: liable CRIMINAL defendant is defendant punishment of CASE prosecution (state) prosecuted guilty or not defendant guilty

There is also a difference in the citation of civil and criminal cases. Donoghue v Stevenson ([1932] A. C. 562) is a civil case. The first name (Donoghue) is the name of the claimant, the second name (Stevenson) is that of the defendant. The 'v' stands for 'versus' (against), but in civil cases this is spoken as 'and'. This case is thus correctly referred to as Donoghue and Stevenson. R v Collins ([1972]2 All E. R. 1105) is a criminal case. The 'R' stands for 'Regina' (the Queen; during the reign of a King it represents 'Rex') and is spoken as 'the Crown'. This shows that the case is brought by the state as prosecutor. The name (Collins) is that of the defendant. In criminal cases the 'v' is spoken as 'against', so that the correct reference to this case is The Crown against Collins.

There is also a difference in the citation of civil and criminal cases. Donoghue v Stevenson ([1932] A. C. 562) is a civil case. The first name (Donoghue) is the name of the claimant, the second name (Stevenson) is that of the defendant. The 'v' stands for 'versus' (against), but in civil cases this is spoken as 'and'. This case is thus correctly referred to as Donoghue and Stevenson. R v Collins ([1972]2 All E. R. 1105) is a criminal case. The 'R' stands for 'Regina' (the Queen; during the reign of a King it represents 'Rex') and is spoken as 'the Crown'. This shows that the case is brought by the state as prosecutor. The name (Collins) is that of the defendant. In criminal cases the 'v' is spoken as 'against', so that the correct reference to this case is The Crown against Collins.

Criminal jurisdiction is divided between the magistrates' courts and the Crown Court. More serious offences are tried before a judge and jury in the Crown Court (indictable offences - crimes like murder, manslaughter and rape). Lesser charges are dealt with by magistrates in a summary trial (summary offences - commmon assault, a number of road traffic offences and lesser cases of criminal damage). The third category are offences triable either way – they can be dealt with either in the Crown Court or the magistrates' court (e. g. theft and arson). The accused can decide whether to opt for trial by a judge and jury in the Crown Court, or for summary trial before a magistrate.

Criminal jurisdiction is divided between the magistrates' courts and the Crown Court. More serious offences are tried before a judge and jury in the Crown Court (indictable offences - crimes like murder, manslaughter and rape). Lesser charges are dealt with by magistrates in a summary trial (summary offences - commmon assault, a number of road traffic offences and lesser cases of criminal damage). The third category are offences triable either way – they can be dealt with either in the Crown Court or the magistrates' court (e. g. theft and arson). The accused can decide whether to opt for trial by a judge and jury in the Crown Court, or for summary trial before a magistrate.

Alternative dispute resolution - ADR are based on the involvement of an independent third party. The aim is to avoid the cost, delay and acrimony involved in a court trial. Arbitration - the most formalised form of ADR. It remains basically adversarial. The parties present their case to an arbitrator, who is bound to apply the law. The procedure is less rigid than before a court and the arbitrator can conduct the matter in the most efficient way. The decision of the arbitrator, the award, is binding on the parties, but can be appealed to the High Court.

Alternative dispute resolution - ADR are based on the involvement of an independent third party. The aim is to avoid the cost, delay and acrimony involved in a court trial. Arbitration - the most formalised form of ADR. It remains basically adversarial. The parties present their case to an arbitrator, who is bound to apply the law. The procedure is less rigid than before a court and the arbitrator can conduct the matter in the most efficient way. The decision of the arbitrator, the award, is binding on the parties, but can be appealed to the High Court.

Mediation and conciliation (terms often used interchangeably). They have in common that an agreement is reached by the parties themselves, with the help of a neutral third party, rather than being imposed by a judge or arbitrator. This outcome is not binding on the parties. The third party will try to help the parties identify the issues and find solutions which are acceptable to both sides. The main advantage of this form of ADR is that it enables the parties to maintain a good working relationship, basing a solution on reconciliation rather than adjudication. The difference between mediation and conciliation lies in the degree of involvement of the third party. The mediator is assisting in the negotiations. A conciliator is suggesting possible solutions; thus he might act more like an arbitrator whose decisions are not binding.

Mediation and conciliation (terms often used interchangeably). They have in common that an agreement is reached by the parties themselves, with the help of a neutral third party, rather than being imposed by a judge or arbitrator. This outcome is not binding on the parties. The third party will try to help the parties identify the issues and find solutions which are acceptable to both sides. The main advantage of this form of ADR is that it enables the parties to maintain a good working relationship, basing a solution on reconciliation rather than adjudication. The difference between mediation and conciliation lies in the degree of involvement of the third party. The mediator is assisting in the negotiations. A conciliator is suggesting possible solutions; thus he might act more like an arbitrator whose decisions are not binding.

The term 'adversarial system' refers to the way in which litigation is conducted before the court. The parties to a dispute are regarded as equally matched opponents who 'fight' before the court, while the judge acts as an independent umpire, remaining largely passive, listening to the evidence presented to him and usually interfering only to clarify an obscure point. The judge does not undertake his own investigations. The inquisitorial system is used in many continental countries. There the judge takes a much more active part in the proceedings and the process of investigation. The principle of material truth.

The term 'adversarial system' refers to the way in which litigation is conducted before the court. The parties to a dispute are regarded as equally matched opponents who 'fight' before the court, while the judge acts as an independent umpire, remaining largely passive, listening to the evidence presented to him and usually interfering only to clarify an obscure point. The judge does not undertake his own investigations. The inquisitorial system is used in many continental countries. There the judge takes a much more active part in the proceedings and the process of investigation. The principle of material truth.

Burden of proof: obligation of a party to legal proceedings to prove a particular fact (or facts). The general rule is that the party who asserts that something is true must prove that it is. Thus the burden of proof is usually on the claimant (in civil cases) or the prosecution (in criminal cases); it can, however, shift to the defendant in certain circumstances. Standard of proof: the degree of proof that is required to establish the truth of a particular fact. In civil cases, the relevant standard of proof is 'on a balance of probabilities', while in criminal cases a fact must be proven 'beyond reasonable doubt'.

Burden of proof: obligation of a party to legal proceedings to prove a particular fact (or facts). The general rule is that the party who asserts that something is true must prove that it is. Thus the burden of proof is usually on the claimant (in civil cases) or the prosecution (in criminal cases); it can, however, shift to the defendant in certain circumstances. Standard of proof: the degree of proof that is required to establish the truth of a particular fact. In civil cases, the relevant standard of proof is 'on a balance of probabilities', while in criminal cases a fact must be proven 'beyond reasonable doubt'.

Some exercises Insert the missing words

Some exercises Insert the missing words

Civil law system: refers to a …… system which is based on ……. . law and centres around ……. . Examples include French and ……. . law. In a different context 'civil law' can also refer to ……… law, as opposed to, for example, ……. . law.

Civil law system: refers to a …… system which is based on ……. . law and centres around ……. . Examples include French and ……. . law. In a different context 'civil law' can also refer to ……… law, as opposed to, for example, ……. . law.

Civil law system: refers to a legal system which is based on Roman law and centres around codes. Examples include French and German law. In a different context 'civil law' can also refer to private law, as opposed to, for example, criminal law.

Civil law system: refers to a legal system which is based on Roman law and centres around codes. Examples include French and German law. In a different context 'civil law' can also refer to private law, as opposed to, for example, criminal law.

Originally 'common law referred to the law …………. . the land, thus distinguishing it from local ………. . . It can be used to differentiate between different ………… of law, such as ……………. law, the law …………. and ………. . Ecclesiastical law has long been completely separate, and the law merchant has been assimilated into ……. . law, but the distinction between common law and equity remains relevant even today. It is also important to differentiate between statute law and …………… law, which in this context is synonymous with ……. . law. Although most new law is introduced by way of ………………, many legal principles are still common law rules. Finally, 'common law' can refer to a legal system, which can be contrasted with ……… law systems.

Originally 'common law referred to the law …………. . the land, thus distinguishing it from local ………. . . It can be used to differentiate between different ………… of law, such as ……………. law, the law …………. and ………. . Ecclesiastical law has long been completely separate, and the law merchant has been assimilated into ……. . law, but the distinction between common law and equity remains relevant even today. It is also important to differentiate between statute law and …………… law, which in this context is synonymous with ……. . law. Although most new law is introduced by way of ………………, many legal principles are still common law rules. Finally, 'common law' can refer to a legal system, which can be contrasted with ……… law systems.

Originally 'common law referred to the law 'common to all the land', thus distinguishing it from local customs. It can be used to differentiate between different systems of law, such as ecclesiastical law, the law merchant and equity. Ecclesiastical law has long been completely separate, and the law merchant has been assimilated into commercial law, but the distinction between common law and equity remains relevant even today. It is also important to differentiate between statute law and common law, which in this context is synonymous with case law. Although most new law is introduced by way of legislation, many legal principles are still common law rules. Finally, 'common law' can refer to a legal system, which can be contrasted with civil law systems.

Originally 'common law referred to the law 'common to all the land', thus distinguishing it from local customs. It can be used to differentiate between different systems of law, such as ecclesiastical law, the law merchant and equity. Ecclesiastical law has long been completely separate, and the law merchant has been assimilated into commercial law, but the distinction between common law and equity remains relevant even today. It is also important to differentiate between statute law and common law, which in this context is synonymous with case law. Although most new law is introduced by way of legislation, many legal principles are still common law rules. Finally, 'common law' can refer to a legal system, which can be contrasted with civil law systems.

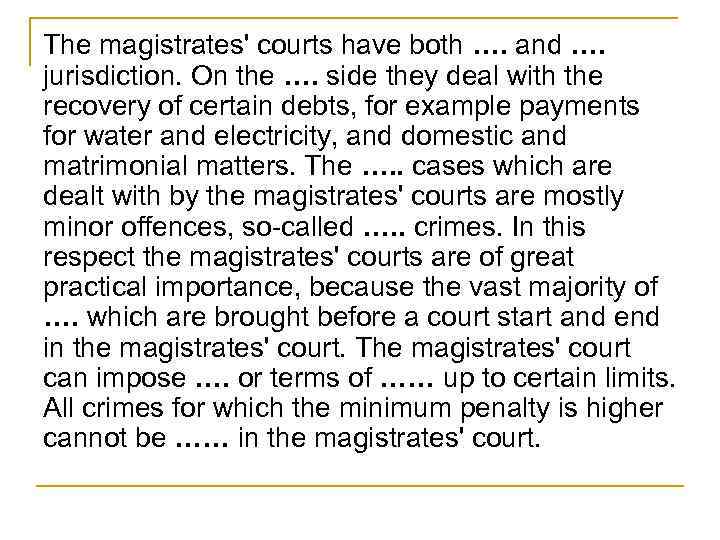

The magistrates' courts have both …. and …. jurisdiction. On the …. side they deal with the recovery of certain debts, for example payments for water and electricity, and domestic and matrimonial matters. The …. . cases which are dealt with by the magistrates' courts are mostly minor offences, so-called …. . crimes. In this respect the magistrates' courts are of great practical importance, because the vast majority of …. which are brought before a court start and end in the magistrates' court. The magistrates' court can impose …. or terms of …… up to certain limits. All crimes for which the minimum penalty is higher cannot be …… in the magistrates' court.

The magistrates' courts have both …. and …. jurisdiction. On the …. side they deal with the recovery of certain debts, for example payments for water and electricity, and domestic and matrimonial matters. The …. . cases which are dealt with by the magistrates' courts are mostly minor offences, so-called …. . crimes. In this respect the magistrates' courts are of great practical importance, because the vast majority of …. which are brought before a court start and end in the magistrates' court. The magistrates' court can impose …. or terms of …… up to certain limits. All crimes for which the minimum penalty is higher cannot be …… in the magistrates' court.

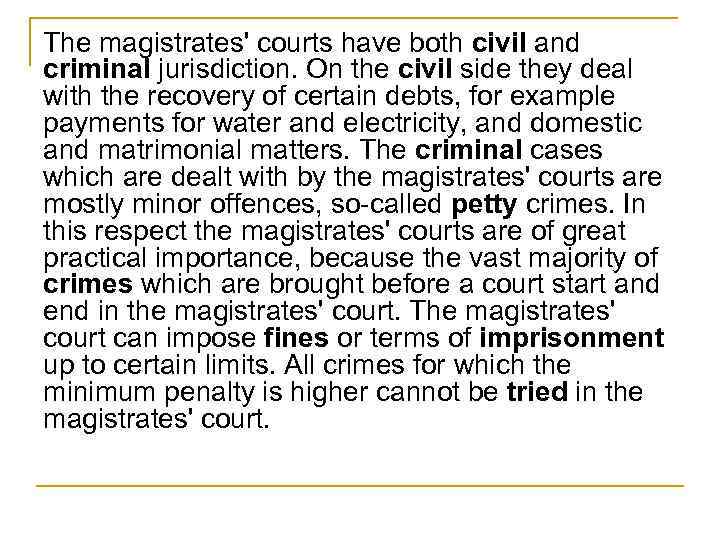

The magistrates' courts have both civil and criminal jurisdiction. On the civil side they deal with the recovery of certain debts, for example payments for water and electricity, and domestic and matrimonial matters. The criminal cases which are dealt with by the magistrates' courts are mostly minor offences, so-called petty crimes. In this respect the magistrates' courts are of great practical importance, because the vast majority of crimes which are brought before a court start and end in the magistrates' court. The magistrates' court can impose fines or terms of imprisonment up to certain limits. All crimes for which the minimum penalty is higher cannot be tried in the magistrates' court.

The magistrates' courts have both civil and criminal jurisdiction. On the civil side they deal with the recovery of certain debts, for example payments for water and electricity, and domestic and matrimonial matters. The criminal cases which are dealt with by the magistrates' courts are mostly minor offences, so-called petty crimes. In this respect the magistrates' courts are of great practical importance, because the vast majority of crimes which are brought before a court start and end in the magistrates' court. The magistrates' court can impose fines or terms of imprisonment up to certain limits. All crimes for which the minimum penalty is higher cannot be tried in the magistrates' court.

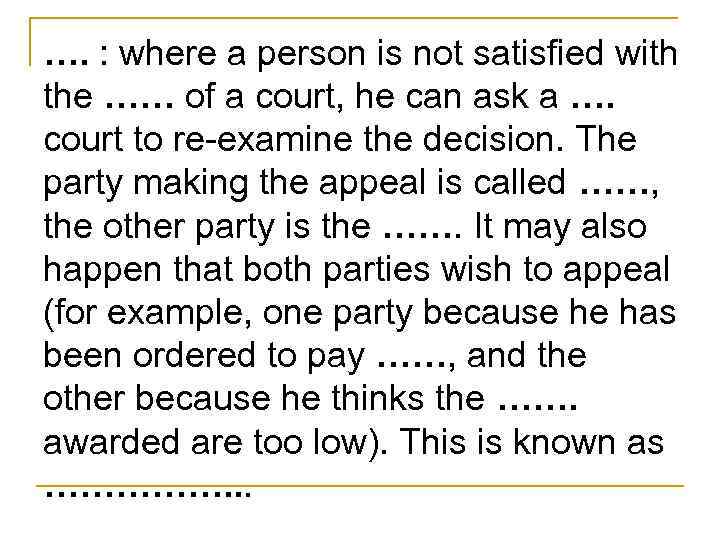

…. : where a person is not satisfied with the …… of a court, he can ask a …. court to re-examine the decision. The party making the appeal is called ……, the other party is the ……. It may also happen that both parties wish to appeal (for example, one party because he has been ordered to pay ……, and the other because he thinks the ……. awarded are too low). This is known as ……………. . .

…. : where a person is not satisfied with the …… of a court, he can ask a …. court to re-examine the decision. The party making the appeal is called ……, the other party is the ……. It may also happen that both parties wish to appeal (for example, one party because he has been ordered to pay ……, and the other because he thinks the ……. awarded are too low). This is known as ……………. . .

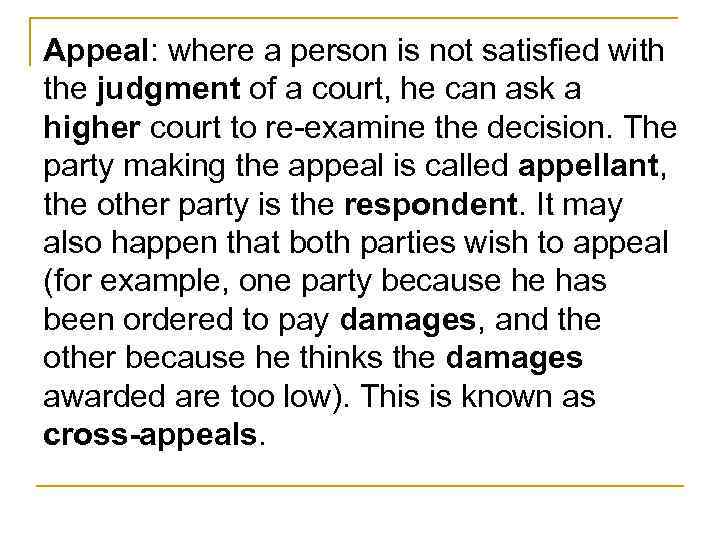

Appeal: where a person is not satisfied with the judgment of a court, he can ask a higher court to re-examine the decision. The party making the appeal is called appellant, the other party is the respondent. It may also happen that both parties wish to appeal (for example, one party because he has been ordered to pay damages, and the other because he thinks the damages awarded are too low). This is known as cross-appeals.

Appeal: where a person is not satisfied with the judgment of a court, he can ask a higher court to re-examine the decision. The party making the appeal is called appellant, the other party is the respondent. It may also happen that both parties wish to appeal (for example, one party because he has been ordered to pay damages, and the other because he thinks the damages awarded are too low). This is known as cross-appeals.

Translate the following text

Translate the following text

It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases, must of necessity expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the courts must decide on the operation of each. So if a law be in opposition to the constitution: if both the law and the constitution apply to a particular case, so that the court must either decide that case conformably to the law, disregarding the constitution; or conformably to the constitution, disregarding the law: the court must determine which of these conflicting rules governs the case. This is of the very essence of judicial duty.

It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases, must of necessity expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the courts must decide on the operation of each. So if a law be in opposition to the constitution: if both the law and the constitution apply to a particular case, so that the court must either decide that case conformably to the law, disregarding the constitution; or conformably to the constitution, disregarding the law: the court must determine which of these conflicting rules governs the case. This is of the very essence of judicial duty.

It is emphatically the province (area) and duty of the judicial department (sphere) to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases, must of necessity expound (explain) and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the courts must decide on the operation (use) of each. So if a law be in opposition to the constitution: if both the law and the constitution apply to a particular case, so that the court must either decide that case conformably to the law, disregarding the constitution; or conformably to the constitution, disregarding the law: the court must determine which of these conflicting rules governs the case. This is of the very essence of judicial duty.

It is emphatically the province (area) and duty of the judicial department (sphere) to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases, must of necessity expound (explain) and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the courts must decide on the operation (use) of each. So if a law be in opposition to the constitution: if both the law and the constitution apply to a particular case, so that the court must either decide that case conformably to the law, disregarding the constitution; or conformably to the constitution, disregarding the law: the court must determine which of these conflicting rules governs the case. This is of the very essence of judicial duty.

The Jury System The right of an accused to be tried by a jury of his peers is regarded by many as a cornerstone of the criminal justice system in England Wales. The involvement of the society as a whole in the judicial process, by letting randomly selected members of the general public decide questions of fact in a court of law is thought to strengthen the legitimacy of the legal system by ensuring that not all power is placed in the hands of professionals.

The Jury System The right of an accused to be tried by a jury of his peers is regarded by many as a cornerstone of the criminal justice system in England Wales. The involvement of the society as a whole in the judicial process, by letting randomly selected members of the general public decide questions of fact in a court of law is thought to strengthen the legitimacy of the legal system by ensuring that not all power is placed in the hands of professionals.

Use of the Jury Generally, juries can be used in both civil and criminal cases. In civil cases the right to trial by jury is limited to four specific cases: actions for fraud, defamation, malicious prosecution and false imprisonment. In all other civil cases the judge has a discretion to allow trial by jury which in practice is granted only rarely. Where a jury is used the jurors decide whether the defendant is liable or not, and what amount of damages, if any, he has to pay.

Use of the Jury Generally, juries can be used in both civil and criminal cases. In civil cases the right to trial by jury is limited to four specific cases: actions for fraud, defamation, malicious prosecution and false imprisonment. In all other civil cases the judge has a discretion to allow trial by jury which in practice is granted only rarely. Where a jury is used the jurors decide whether the defendant is liable or not, and what amount of damages, if any, he has to pay.

Criminal juries are still a well-established part of the English legal system. There is no jury in the magistrates' courts, but cases before the Crown Court are heard by a jury, which determines the question of guilt. If the defendant is found guilty the judge fixes the sentence. Should the accused plead guilty to the charges the jury does not get involved; the judge simply decides on the sentence.

Criminal juries are still a well-established part of the English legal system. There is no jury in the magistrates' courts, but cases before the Crown Court are heard by a jury, which determines the question of guilt. If the defendant is found guilty the judge fixes the sentence. Should the accused plead guilty to the charges the jury does not get involved; the judge simply decides on the sentence.

A modern jury is a group of 12 persons (jurors), randomly selected from society to decide questions of fact in civil and criminal cases. List of potential jurors (generally every person who is between 18 and 70), called panels. The actual jury for each case is then selected from the panel for the court in question. People suffering from a mental illness and those convicted of certain criminal offences are disqualified from jury service. Prosecution and defence have the right to challenge any juror and ask the judge to remove him from the jury. The term 'jury vetting' refers to the practice of conducting checks on the backgrounds of potential jurors which go beyond checking for criminal records.

A modern jury is a group of 12 persons (jurors), randomly selected from society to decide questions of fact in civil and criminal cases. List of potential jurors (generally every person who is between 18 and 70), called panels. The actual jury for each case is then selected from the panel for the court in question. People suffering from a mental illness and those convicted of certain criminal offences are disqualified from jury service. Prosecution and defence have the right to challenge any juror and ask the judge to remove him from the jury. The term 'jury vetting' refers to the practice of conducting checks on the backgrounds of potential jurors which go beyond checking for criminal records.

Generally the decision of the jury must be unanimous, but a majority verdict of 11: 1 or 10: 2 is acceptable, if the judge has stated that he will accept such a verdict. If the jury fail to agree on an outcome and the trial judge does not accept a majority verdict, the case is declared a mis-trial. The jurors are discharged, and the case may be retried before a newly-selected jury. In a criminal case the jury will find the defendant "guilty" or "not guilty" of each offence that he is charged with. In a civil case the jury will find the defendant "liable" or "not liable".

Generally the decision of the jury must be unanimous, but a majority verdict of 11: 1 or 10: 2 is acceptable, if the judge has stated that he will accept such a verdict. If the jury fail to agree on an outcome and the trial judge does not accept a majority verdict, the case is declared a mis-trial. The jurors are discharged, and the case may be retried before a newly-selected jury. In a criminal case the jury will find the defendant "guilty" or "not guilty" of each offence that he is charged with. In a civil case the jury will find the defendant "liable" or "not liable".

One important aspect of the work of juries is the concept of jury secrecy. This means that the discussions which take place in the jury room must be kept absolutely secret. Members of the jury are not allowed to disclose, nor are outsiders allowed to enquire after, the opinions and votes of individual jurors; it is a contempt of court to do so. One aim of this rule is to protect jurors from outside pressure and harassment by ensuring that no outsider knows the details of the deliberations. In addition, it encourages jurors to speak openly and frankly during the discussions.

One important aspect of the work of juries is the concept of jury secrecy. This means that the discussions which take place in the jury room must be kept absolutely secret. Members of the jury are not allowed to disclose, nor are outsiders allowed to enquire after, the opinions and votes of individual jurors; it is a contempt of court to do so. One aim of this rule is to protect jurors from outside pressure and harassment by ensuring that no outsider knows the details of the deliberations. In addition, it encourages jurors to speak openly and frankly during the discussions.

A person tried and acquitted of a criminal charge could not be tried again for that same offence (Ne bis in idem - the rule against double jeopardy). In some limited circumstances this rule has been removed by the Criminal Justice Act 2003. For certain qualifying offences, such as homicide and serious sexual offences, a second trial of someone already acquitted may be possible, where new and compelling evidence exists.

A person tried and acquitted of a criminal charge could not be tried again for that same offence (Ne bis in idem - the rule against double jeopardy). In some limited circumstances this rule has been removed by the Criminal Justice Act 2003. For certain qualifying offences, such as homicide and serious sexual offences, a second trial of someone already acquitted may be possible, where new and compelling evidence exists.

Problems related to the use of juries. Jurors can be intimidated, threatened (such behaviour is known as 'jury nobbling') or corrupt. They may lack objectivity through being subconsciously prejudiced, or may simply be unable to understand the evidence, for example in complex fraud cases. This can leave them susceptible to the persuasive influence of counsel. The quantum of damages awarded by juries (especially in defamation cases) is often excessive and bears no relation to the loss actually suffered by the claimant. Finally, juries do not give reasons for their verdict, which can make it difficult for the parties involved to identify possible grounds for appeal.

Problems related to the use of juries. Jurors can be intimidated, threatened (such behaviour is known as 'jury nobbling') or corrupt. They may lack objectivity through being subconsciously prejudiced, or may simply be unable to understand the evidence, for example in complex fraud cases. This can leave them susceptible to the persuasive influence of counsel. The quantum of damages awarded by juries (especially in defamation cases) is often excessive and bears no relation to the loss actually suffered by the claimant. Finally, juries do not give reasons for their verdict, which can make it difficult for the parties involved to identify possible grounds for appeal.

Jury tampering: interference with members of a jury by intimidation, bribery or other persuasive means. Majority verdict: does not mean a simple majority; in order to be valid as a majority verdict, the decision of the jury must be taken 11: 1 or 10: 2. A split of, for example, 7: 5 is not sufficient. Summing-up: summary of the evidence by the judge to the jury. Must be distinguished from a direction to the jury: the judge instructs the jury on any questions of law (he tells them what the law is), so that they can apply points of law to the facts of the case. Directions on points of law will usually be included in the summing-up. Verdict: the decision of the jury on a question of fact presented to them in a civil or criminal trial. The verdict must be distinguished from a judgment, which is the formal decision of a court (i. e. one or several judges). Unanimous verdict: where all members of the jury are in agreement as to whether a defendant is guilty or not guilty.

Jury tampering: interference with members of a jury by intimidation, bribery or other persuasive means. Majority verdict: does not mean a simple majority; in order to be valid as a majority verdict, the decision of the jury must be taken 11: 1 or 10: 2. A split of, for example, 7: 5 is not sufficient. Summing-up: summary of the evidence by the judge to the jury. Must be distinguished from a direction to the jury: the judge instructs the jury on any questions of law (he tells them what the law is), so that they can apply points of law to the facts of the case. Directions on points of law will usually be included in the summing-up. Verdict: the decision of the jury on a question of fact presented to them in a civil or criminal trial. The verdict must be distinguished from a judgment, which is the formal decision of a court (i. e. one or several judges). Unanimous verdict: where all members of the jury are in agreement as to whether a defendant is guilty or not guilty.

Write an essay What could be the advantages and the disadvantages of a jury system?

Write an essay What could be the advantages and the disadvantages of a jury system?

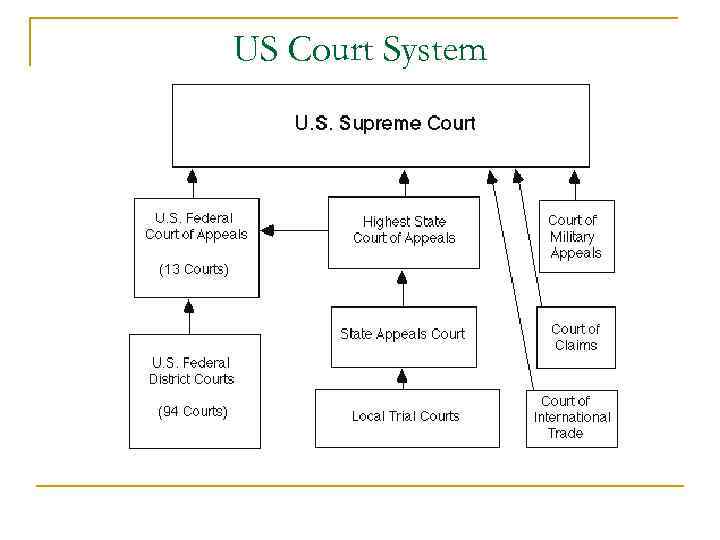

US Court System

US Court System

The U. S. Supreme Court Created by Sec 1 Article III of the Constitution. Its jurisdiction and organization are spelled out by legislation. The Court itself develops the rules governing the presentation of cases. One of the most important powers of the Supreme Court is judicial review. While the Supreme Court is a separate branch of government. There are nine justices; a Chief Justice of the United States and eight associate justices, appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate. Justices serve during good behavior (usually until death, retirement or resignation).

The U. S. Supreme Court Created by Sec 1 Article III of the Constitution. Its jurisdiction and organization are spelled out by legislation. The Court itself develops the rules governing the presentation of cases. One of the most important powers of the Supreme Court is judicial review. While the Supreme Court is a separate branch of government. There are nine justices; a Chief Justice of the United States and eight associate justices, appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate. Justices serve during good behavior (usually until death, retirement or resignation).

Judicial review consists of: -The power of the courts to declare laws invalid if they violate the Constitution. -The supremacy of federal laws or treaties when they differ from state and local laws. -The role of the Court as the final authority on the meaning of the Constitution.

Judicial review consists of: -The power of the courts to declare laws invalid if they violate the Constitution. -The supremacy of federal laws or treaties when they differ from state and local laws. -The role of the Court as the final authority on the meaning of the Constitution.

Legal influences on Supreme Court decisions : - The Constraints of the Facts: Courts cannot make a ruling unless they have an actual case brought before it. The facts of a case are the relevant circumstances of a legal dispute or offense. The Supreme Court must respond to the facts of a dispute. - The Constraints of the Law: Among the legal constraints in deciding cases, the Supreme Court must determine which laws are relevant. These include; interpretation of the Constitution, interpretation of statutes, and interpretation of precedent.

Legal influences on Supreme Court decisions : - The Constraints of the Facts: Courts cannot make a ruling unless they have an actual case brought before it. The facts of a case are the relevant circumstances of a legal dispute or offense. The Supreme Court must respond to the facts of a dispute. - The Constraints of the Law: Among the legal constraints in deciding cases, the Supreme Court must determine which laws are relevant. These include; interpretation of the Constitution, interpretation of statutes, and interpretation of precedent.

Political influences on Supreme Court Decisions : -"Outside Influences" Such as the force of public opinion, pressure from interest groups, and the leverage of public officials. -"Inside Influences" Such as justices' personal beliefs, political attitudes, and the relationship between justices.

Political influences on Supreme Court Decisions : -"Outside Influences" Such as the force of public opinion, pressure from interest groups, and the leverage of public officials. -"Inside Influences" Such as justices' personal beliefs, political attitudes, and the relationship between justices.

How Cases Make Their Way to the U. S. Supreme Court Each year, about 4, 500 cases are requested for review by the Supreme Court. Less than 200 cases are actually decided by the Court each year. Three ways for a case to make its way to the US Supreme Court.

How Cases Make Their Way to the U. S. Supreme Court Each year, about 4, 500 cases are requested for review by the Supreme Court. Less than 200 cases are actually decided by the Court each year. Three ways for a case to make its way to the US Supreme Court.

1) There are cases in which the US Supreme Court has original jurisdiction (heard there first). Cases in which a state is a party and cases dealing with diplomatic personnel, like ambassadors, are the two examples. 2) Those cases appealed from lower federal courts can be heard at the Supreme Court. Some laws obligate (or force) the Supreme Court to hear them. But most come up for review on the writ of certiorari, a discretionary writ that the court grants or refuses at its own discretion. The writ is granted if four of the justices want it to be heard.

1) There are cases in which the US Supreme Court has original jurisdiction (heard there first). Cases in which a state is a party and cases dealing with diplomatic personnel, like ambassadors, are the two examples. 2) Those cases appealed from lower federal courts can be heard at the Supreme Court. Some laws obligate (or force) the Supreme Court to hear them. But most come up for review on the writ of certiorari, a discretionary writ that the court grants or refuses at its own discretion. The writ is granted if four of the justices want it to be heard.

3) The US Supreme Court reviews appeals from state supreme courts that present substantial "federal questions, " usually where a constitutional right has been denied in the state courts. In both civil and criminal law, the Supreme Court is the final court of appeal. The ‘writ of certiorari' – to file a petition, to the highest court in the Federal court system; writ = 'a court order' certiorari = 'to be informed of the case'

3) The US Supreme Court reviews appeals from state supreme courts that present substantial "federal questions, " usually where a constitutional right has been denied in the state courts. In both civil and criminal law, the Supreme Court is the final court of appeal. The ‘writ of certiorari' – to file a petition, to the highest court in the Federal court system; writ = 'a court order' certiorari = 'to be informed of the case'

State Courts - Each state has a court system that exist independently from the federal courts. - State court systems have trial courts at the bottom level and appellate courts at the top. - Over 95% of the nation's legal cases are decided in state courts (or local courts, which are agents of the states).

State Courts - Each state has a court system that exist independently from the federal courts. - State court systems have trial courts at the bottom level and appellate courts at the top. - Over 95% of the nation's legal cases are decided in state courts (or local courts, which are agents of the states).

States usually give some lower courts specialized titles and jurisdictions. Family courts settle such issues as divorce and child-custody disputes, probate courts handle the settlement of the estates of deceased persons. Less formal trial courts, such as magistrate courts and justice of the peace courts. These handle a variety of minor cases, such as traffic offenses, and usually do not use a jury.

States usually give some lower courts specialized titles and jurisdictions. Family courts settle such issues as divorce and child-custody disputes, probate courts handle the settlement of the estates of deceased persons. Less formal trial courts, such as magistrate courts and justice of the peace courts. These handle a variety of minor cases, such as traffic offenses, and usually do not use a jury.

Cases that originate in state courts can be appealed to a federal court if a federal issue is involved and usually only after all avenues of appeal in the state courts have been tried. In 1990 there were over 88 million cases heard at the state trial courts throughout the U. S. 167 thousand cases were appealed at the next level, while 62 thousand made it to the state courts of last resort. Two appellate levels in some states, and a single appellate court in others.

Cases that originate in state courts can be appealed to a federal court if a federal issue is involved and usually only after all avenues of appeal in the state courts have been tried. In 1990 there were over 88 million cases heard at the state trial courts throughout the U. S. 167 thousand cases were appealed at the next level, while 62 thousand made it to the state courts of last resort. Two appellate levels in some states, and a single appellate court in others.

Federal Courts of Appeal n n n When cases are appealed from district courts, they go to a federal court of appeals. Courts of appeals do not use juries or witnesses. No new evidence is submitted in an appealed case; Appellate courts base their decisions on a review of lower-court records. In 1990, the 158 judges handled about 41, 000 cases.

Federal Courts of Appeal n n n When cases are appealed from district courts, they go to a federal court of appeals. Courts of appeals do not use juries or witnesses. No new evidence is submitted in an appealed case; Appellate courts base their decisions on a review of lower-court records. In 1990, the 158 judges handled about 41, 000 cases.

There are 12 general appeals courts. All but one of them (which serves only the District of Columbia) serve an area consisting of three to nine states (called a circuit. ) There is also the U. S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which specializes in appeals of decisions in cases involving patents, contract claims against the federal government, federal employment cases and international trade.

There are 12 general appeals courts. All but one of them (which serves only the District of Columbia) serve an area consisting of three to nine states (called a circuit. ) There is also the U. S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which specializes in appeals of decisions in cases involving patents, contract claims against the federal government, federal employment cases and international trade.

Between four and twenty six judges sit on each court of appeals, and each case is usually heard by a panel of three judges. Courts of appeals offer the best hope of reversal for many appellants, since the Supreme Court hears so few cases. Fewer than 1 percent of the cases heard by federal appeals courts are later reviewed by the Supreme Court.

Between four and twenty six judges sit on each court of appeals, and each case is usually heard by a panel of three judges. Courts of appeals offer the best hope of reversal for many appellants, since the Supreme Court hears so few cases. Fewer than 1 percent of the cases heard by federal appeals courts are later reviewed by the Supreme Court.

Federal District Courts All federal courts, except for the U. S. Supreme Court were created by Congress. There are ninety four federal district courts across the country, with at least one in every state (larger states have up to four). There about 550 federal district-court judges who are appointed by the president with the advice of the Senate.

Federal District Courts All federal courts, except for the U. S. Supreme Court were created by Congress. There are ninety four federal district courts across the country, with at least one in every state (larger states have up to four). There about 550 federal district-court judges who are appointed by the president with the advice of the Senate.

District courts are the only courts in the federal system in which juries hear testimony in some cases, and most cases at this level are presented before a single judge. They heard about 267, 000 cases in 1990. Federal district courts are bound by legal precedents established by the Supreme Court. Most federal cases end with the district court's decision.

District courts are the only courts in the federal system in which juries hear testimony in some cases, and most cases at this level are presented before a single judge. They heard about 267, 000 cases in 1990. Federal district courts are bound by legal precedents established by the Supreme Court. Most federal cases end with the district court's decision.

Court of Military Appeals. The Court of Military Appeals hears appeals of military court-martial (when a person who is in the military commits a crime they can be tried and punished by the military courts. ) Court of International Trade. The Court of International Trade hears cases involving appeals of rulings of U. S. Customs offices. Court of Claims. The Court of Claims hears cases in which the U. S. Government is sued.

Court of Military Appeals. The Court of Military Appeals hears appeals of military court-martial (when a person who is in the military commits a crime they can be tried and punished by the military courts. ) Court of International Trade. The Court of International Trade hears cases involving appeals of rulings of U. S. Customs offices. Court of Claims. The Court of Claims hears cases in which the U. S. Government is sued.

INTERMEZZO The eloquence of the legal profession

INTERMEZZO The eloquence of the legal profession

Lawyers are, on the one hand, among the most eloquent users of the English language while, on the other, they are perhaps its most notorious abusers

Lawyers are, on the one hand, among the most eloquent users of the English language while, on the other, they are perhaps its most notorious abusers

Daniel Webster addressing the jurors: The criminal law is not founded in a principle of vengeance. It does not punish that it may inflict suffering. The humanity of the law feels and regrets every pain that it causes, every hour of restraint it imposes, and more deeply still, every life it forfeits. But it uses evil, as the means of preventing greater evil. It seeks to deter from crime, by the example of punishment. This is its true, and only true main object. It restrains the liberty of the few offenders, that the many who do not offend, may enjoy their own liberty. It forfeits the life of the murderer, that other murders may not be committed.

Daniel Webster addressing the jurors: The criminal law is not founded in a principle of vengeance. It does not punish that it may inflict suffering. The humanity of the law feels and regrets every pain that it causes, every hour of restraint it imposes, and more deeply still, every life it forfeits. But it uses evil, as the means of preventing greater evil. It seeks to deter from crime, by the example of punishment. This is its true, and only true main object. It restrains the liberty of the few offenders, that the many who do not offend, may enjoy their own liberty. It forfeits the life of the murderer, that other murders may not be committed.