f20e469e4ae67f9a7843d62c56b17798.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 107

Introduction Ira M. Jacobson, MD Vincent Astor Professor of Medicine Chief, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Medical Director of the Center for the Study of Hepatitis C Weill Cornell Medical College New York, New York

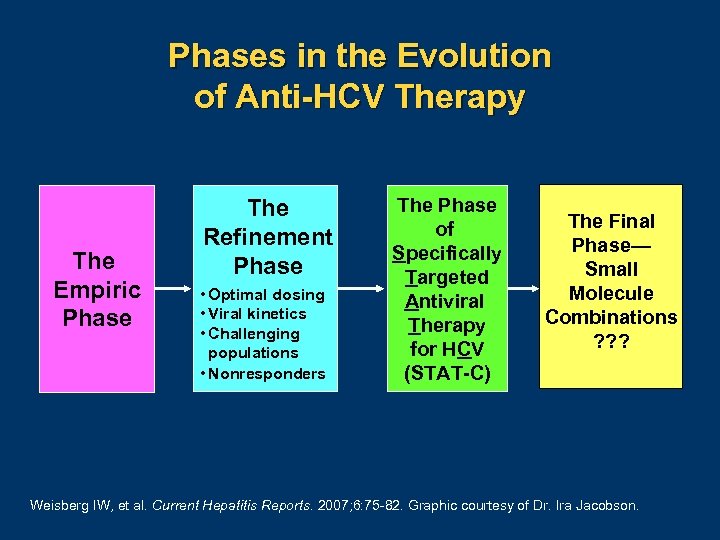

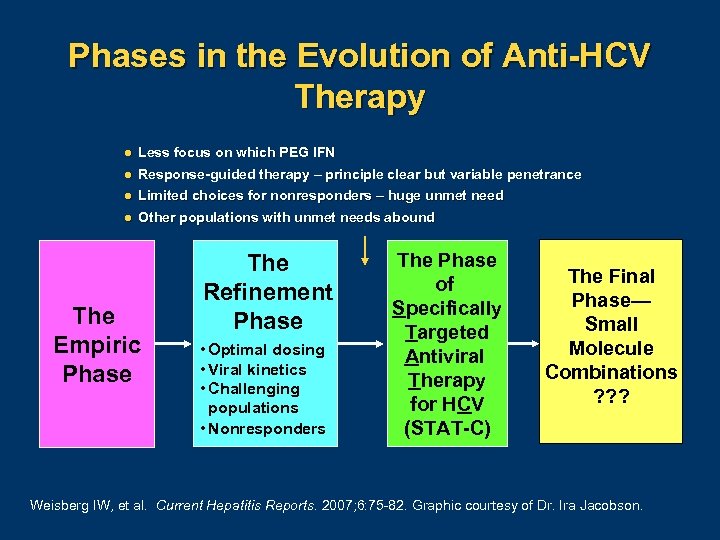

Phases in the Evolution of Anti-HCV Therapy The Empiric Phase The Refinement Phase • Optimal dosing • Viral kinetics • Challenging populations • Nonresponders The Phase of Specifically Targeted Antiviral Therapy for HCV (STAT-C) The Final Phase— Small Molecule Combinations ? ? ? Weisberg IW, et al. Current Hepatitis Reports. 2007; 6: 75 82. Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson.

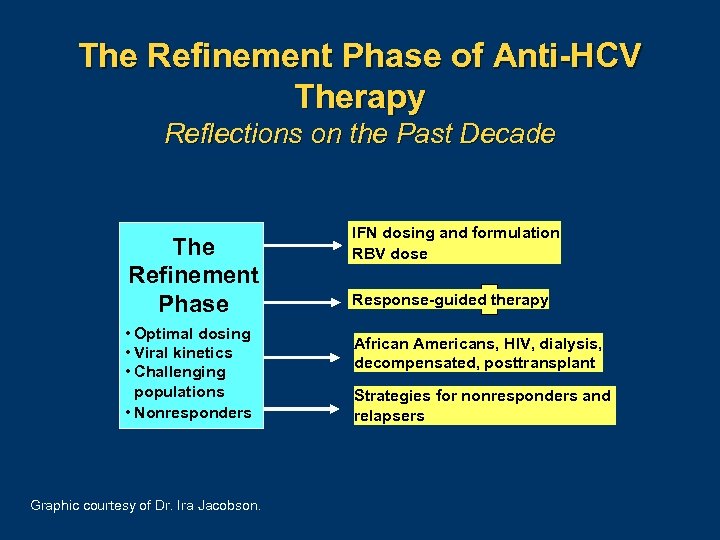

The Refinement Phase of Anti-HCV Therapy Reflections on the Past Decade The Refinement Phase • Optimal dosing • Viral kinetics • Challenging populations • Nonresponders Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson. IFN dosing and formulation RBV dose Response-guided therapy African Americans, HIV, dialysis, decompensated, posttransplant Strategies for nonresponders and relapsers

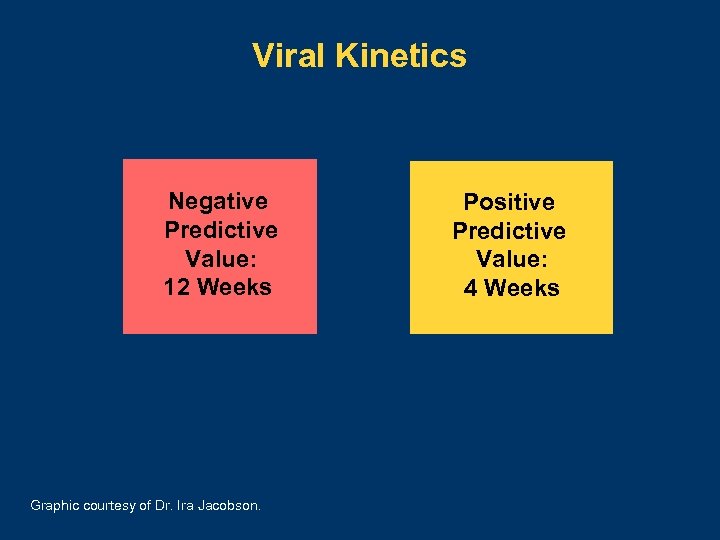

Viral Kinetics Negative Predictive Value: 12 Weeks Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson. Positive Predictive Value: 4 Weeks

The “Accordion” Effect in Anti-HCV Therapy The Earlier HCV RNA Clears, the Shorter the Treatment Required 1 -8 Start 4 8 Time to First RNA Neg 12 16 24 48 72 (wk) End of Treatment 12– 16 wk: Gt 2/3 with RVR 24 wk: Gt 1 LVL with RVR 48 wk: Gt 1 standard 72 wk: Gt 1 slow responders Abbreviations: Gt, genotype; LVL, low viral load; RVR, rapid viral response. 1. Berg T, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006; 130: 1086 1097. 2. Dalgard O, et al. Hepatology. 2008; 47: 35 42. 3. Jensen DM, et al. Hepatology. 2006; 43: 954 960. 4. Mangia A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352: 2609 2617. 5. Mangia A, et al. Hepatology. 2008; 47: 43 50. 6. Sanchez Tapias JM, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006; 131: 451 460. 7. von Wagner MV, et al. Gastroenterology. 2005; 129: 522 527. 8. Zeuzem S, et al. J Hepatology. 2006; 44: 97 103. Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson.

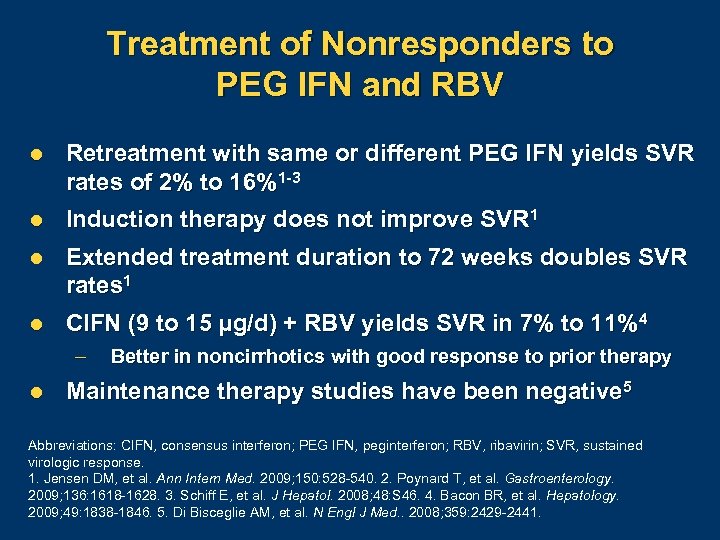

Treatment of Nonresponders to PEG IFN and RBV l Retreatment with same or different PEG IFN yields SVR rates of 2% to 16%1 -3 l Induction therapy does not improve SVR 1 l Extended treatment duration to 72 weeks doubles SVR rates 1 l CIFN (9 to 15 µg/d) + RBV yields SVR in 7% to 11%4 – l Better in noncirrhotics with good response to prior therapy Maintenance therapy studies have been negative 5 Abbreviations: CIFN, consensus interferon; PEG IFN, peginterferon; RBV, ribavirin; SVR, sustained virologic response. 1. Jensen DM, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 150: 528 540. 2. Poynard T, et al. Gastroenterology. 2009; 136: 1618 1628. 3. Schiff E, et al. J Hepatol. 2008; 48: S 46. 4. Bacon BR, et al. Hepatology. 2009; 49: 1838 1846. 5. Di Bisceglie AM, et al. N Engl J Med. . 2008; 359: 2429 2441.

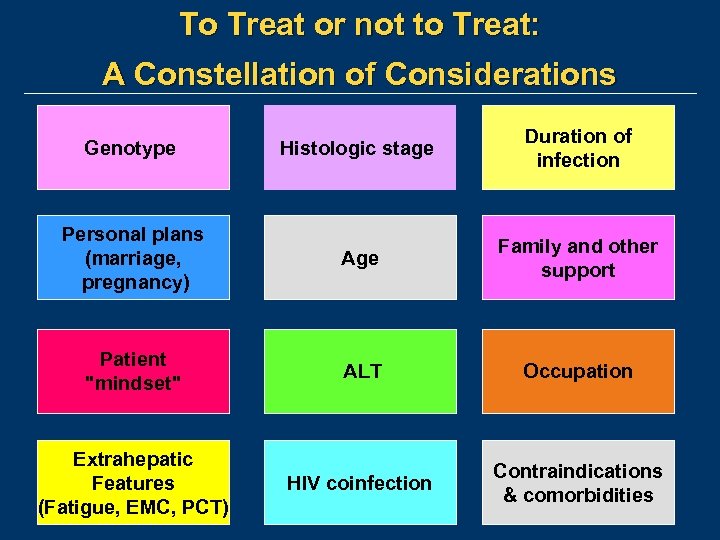

To Treat or not to Treat: A Constellation of Considerations Genotype Histologic stage Duration of infection Personal plans (marriage, pregnancy) Age Family and other support Patient "mindset" ALT Occupation Extrahepatic Features (Fatigue, EMC, PCT) HIV coinfection Contraindications & comorbidities

Management of Viral Hepatitis—Huge Unmet Needs Efficacy in Clinical Trials and Research Centers Effectiveness in Community Practice Efficacy x Access x Correct Diagnosis x Recommendation x Acceptance x Adherence El Serag HB. Gastroenterology. 2007; 132: 8 10.

Real World Pressures in an Already Labor-Intensive Specialty PQRI Electronic Records Declining Reimbursements (Physician Quality Reporting Initiative) Medicolegal Issues & Costs Coding and Billing Compliance Ambulatory Surgery Centers Increasingly Complicated Regimens Drug Costs & Potential Insurance Constraints E-prescribing Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson.

A Day in the Life of a Hepatology Practice …in the Future Rosemarie Nelson, MS Principal MGMA Health Care Consulting Group Englewood, Colorado

Agenda l State of the industry – The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) = “stimulus package” n The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act – Encourage adoption of electronic health record – Reimbursement shifts l l Operational questions and technologic answers What does it mean for your patients? 13

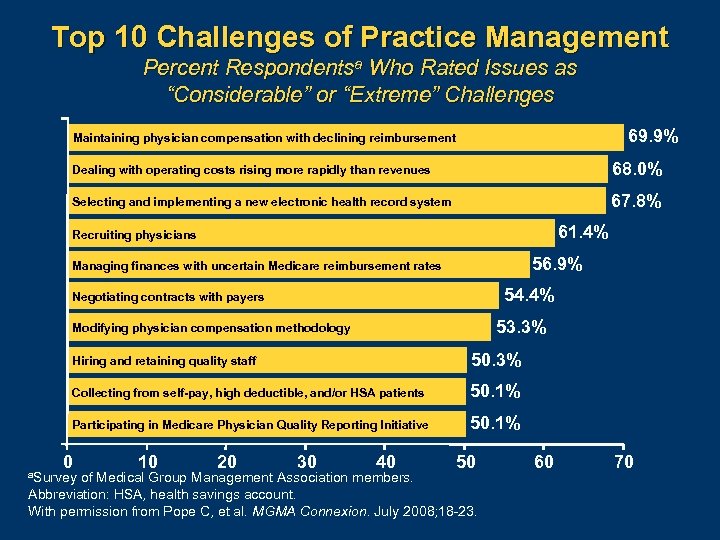

Top 10 Challenges of Practice Management Percent Respondentsa Who Rated Issues as “Considerable” or “Extreme” Challenges 69. 9% Maintaining physician compensation with declining reimbursement Dealing with operating costs rising more rapidly than revenues 68. 0% Selecting and implementing a new electronic health record system 67. 8% 61. 4% Recruiting physicians 56. 9% Managing finances with uncertain Medicare reimbursement rates 54. 4% Negotiating contracts with payers 53. 3% Modifying physician compensation methodology Hiring and retaining quality staff 50. 3% Collecting from self-pay, high deductible, and/or HSA patients 50. 1% Participating in Medicare Physician Quality Reporting Initiative 50. 1% 0 a. Survey 10 20 30 40 50 of Medical Group Management Association members. Abbreviation: HSA, health savings account. With permission from Pope C, et al. MGMA Connexion. July 2008; 18 23. 60 70

Commitments of Surveyed Hepatologists l Providing standard of care l Giving more informed advice to patients l Screening for hepatitis C virus Projects In Knowledge, Inc. Internal proprietary survey. 2009.

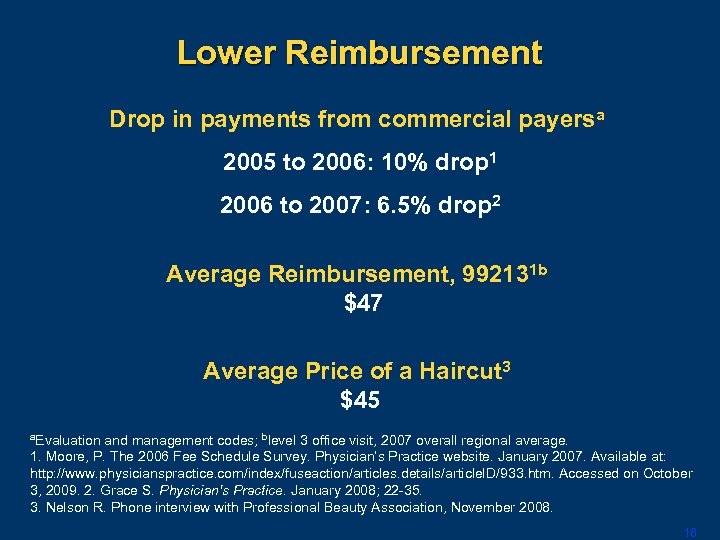

Lower Reimbursement Drop in payments from commercial payersa 2005 to 2006: 10% drop 1 2006 to 2007: 6. 5% drop 2 Average Reimbursement, 992131 b $47 Average Price of a Haircut 3 $45 a. Evaluation and management codes; blevel 3 office visit, 2007 overall regional average. 1. Moore, P. The 2006 Fee Schedule Survey. Physician’s Practice website. January 2007. Available at: http: //www. physicianspractice. com/index/fuseaction/articles. details/article. ID/933. htm. Accessed on October 3, 2009. 2. Grace S. Physician's Practice. January 2008; 22 35. 3. Nelson R. Phone interview with Professional Beauty Association, November 2008. 16

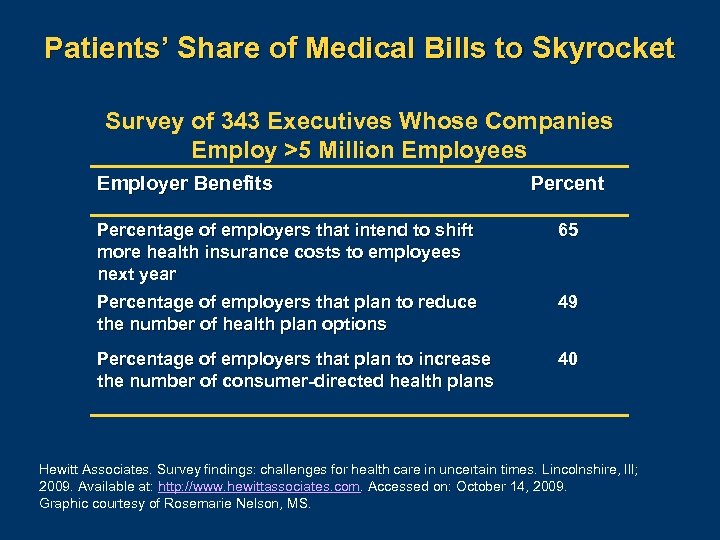

Patients’ Share of Medical Bills to Skyrocket Survey of 343 Executives Whose Companies Employ >5 Million Employees Employer Benefits Percentage of employers that intend to shift more health insurance costs to employees next year 65 Percentage of employers that plan to reduce the number of health plan options 49 Percentage of employers that plan to increase the number of consumer-directed health plans 40 Hewitt Associates. Survey findings: challenges for health care in uncertain times. Lincolnshire, Ill; 2009. Available at: http: //www. hewittassociates. com. Accessed on: October 14, 2009. Graphic courtesy of Rosemarie Nelson, MS.

Provider Total Revenues Attributable to Patient Receivables Celent. Press release: The "retailish" future of patient collections. San Francisco, Calif: February 18, 2009. Available at: http: //reports. celent. com/Press. Releases/20090217/Retailish. asp. Accessed on: October 14, 2009.

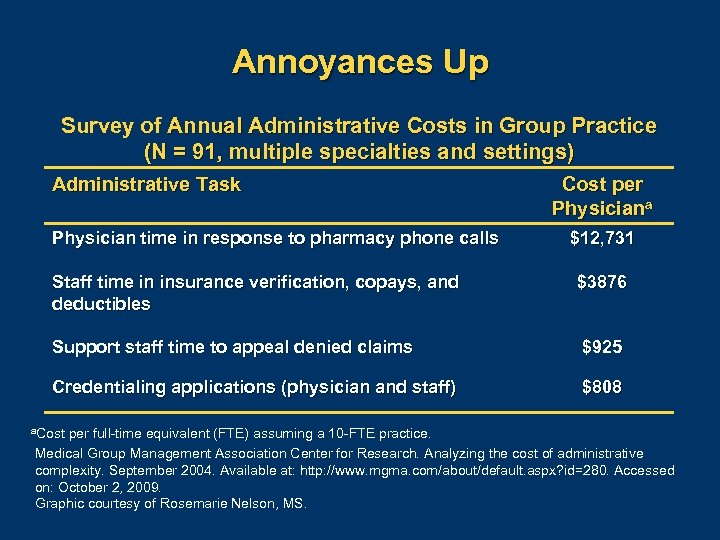

Annoyances Up Survey of Annual Administrative Costs in Group Practice (N = 91, multiple specialties and settings) Administrative Task Physician time in response to pharmacy phone calls Cost per Physiciana $12, 731 Staff time in insurance verification, copays, and deductibles $3876 Support staff time to appeal denied claims $925 Credentialing applications (physician and staff) $808 a. Cost per full time equivalent (FTE) assuming a 10 FTE practice. Medical Group Management Association Center for Research. Analyzing the cost of administrative complexity. September 2004. Available at: http: //www. mgma. com/about/default. aspx? id=280. Accessed on: October 2, 2009. Graphic courtesy of Rosemarie Nelson, MS.

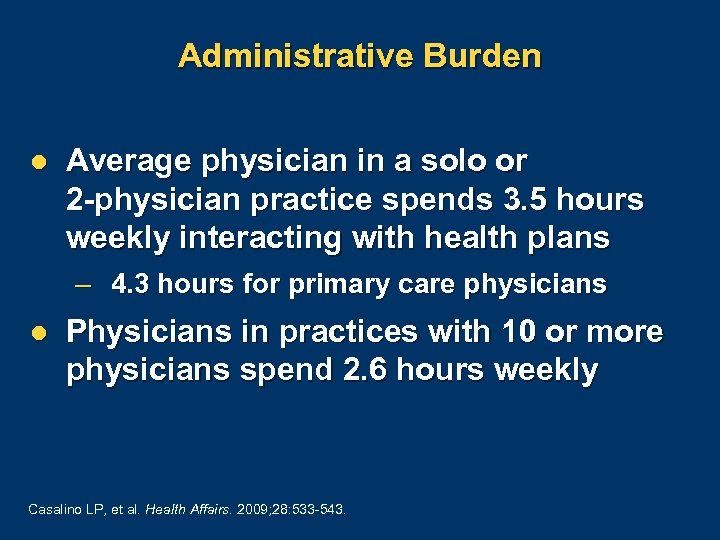

Administrative Burden l Average physician in a solo or 2 -physician practice spends 3. 5 hours weekly interacting with health plans – 4. 3 hours for primary care physicians l Physicians in practices with 10 or more physicians spend 2. 6 hours weekly Casalino LP, et al. Health Affairs. 2009; 28: 533 543.

Mean Dollar Value of Hours Spent per Physician per Year for All Health Plan Interactions Survey of US Physicians and Administrative Staff 730 Primary Care Physicians; 580 Specialists 1– 2 MDs 3– 9 MDs 10+ MDs Physician time $17, 817 $15, 670 $13, 798 Nursing staff time $14, 897 $26, 225 $24, 314 Clerical staff time $30, 014 $25, 632 $18, 636 Senior administrative time $5829 $3269 $1235 Lawyer/accountant time $1249 $626 $4455 $69, 806 $71, 422 $62, 438 Total per practice With permission from Casalino LP, et al. Health Affairs. 2009; 28: 533 543.

Better-Performing Practices l Over 62% of better-performing practices employ nonphysician providers to increase physician productivity performance levels 1 – vs 50% of other practices l Improved access for patients l Maximize physician time 1. Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). Performance and Practices of Successful Medical Groups 2008 Report Based on 2007 Data. Englewood, Co: MGMA; 2008.

Conversion to ICD-10 Code Set Deadline for compliance October 1, 20131 l ICD-9 (up to 5 characters) ICD-10 (up to 7 characters) Conversion–Estimate of Costs to Comply for a Typical Small Practice 2 a Category Training and education Business analysis Super-bill changes IT system changes Increased documentation costs Cash flow disruption Total Costs l a. Small Cost $2405 $6905 $2985 $7500 $44, 000 $19, 500 $83, 295 Same group: $99, 000 to move to EHR 3 practice defined as 3 physicians and 2 administrative staff. 1. US HSS. Press release. January 15, 2009. Available at: http: //www. hhs. gov/news/press/2009 pres/01/20090115 f. html. Accessed on: October 3, 2009. 2. (Bottom graphic) With permission from Nachimson Advisors, LLC. The impact of implementing ICD‐ 10 on physician practices and clinical laboratories: a report to the ICD 10 coalition. October 8, 2008. 3. Nelson R. Unpublished data.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services E-Prescribing Incentive Program l Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 (MIPPA) l Bonus of 2% of Medicare allowed charges for 2009 – Bonus 1% in 2012 and to 0. 5% in 2013 – Bonus eliminated in 2014 l Simple reporting - only 3 G-codes US Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare's practical guide to the e prescribing incentive program. November 2008. Available at: http: //www. cms. hhs. gov/partnerships/downloads/11399. pdf. Accessed on: October 3, 2009.

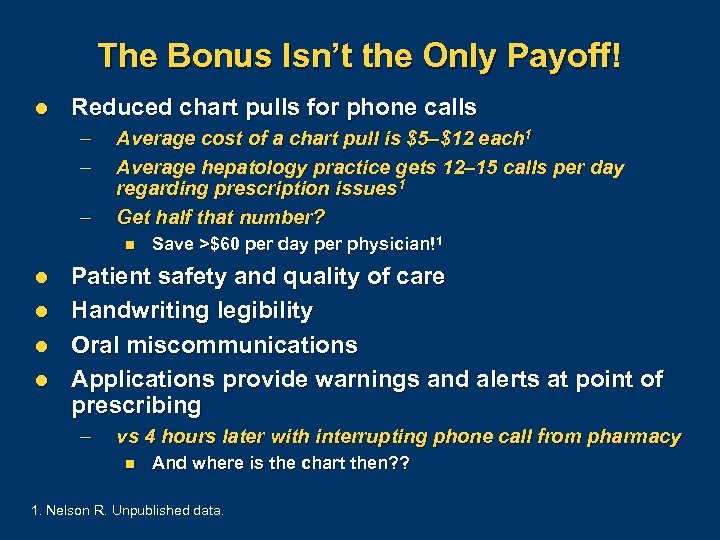

The Bonus Isn’t the Only Payoff! l Reduced chart pulls for phone calls – – – Average cost of a chart pull is $5–$12 each 1 Average hepatology practice gets 12– 15 calls per day regarding prescription issues 1 Get half that number? n l l Save >$60 per day per physician!1 Patient safety and quality of care Handwriting legibility Oral miscommunications Applications provide warnings and alerts at point of prescribing – vs 4 hours later with interrupting phone call from pharmacy n And where is the chart then? ? 1. Nelson R. Unpublished data.

E-Prescribing Reduces Overhead and Management Headaches l Bonus money now, penalty reduction later l Operational efficiency drives reduced costs l Transition and implementation is manageable l Address patient safety and quality of care l Gain experience to carry over to electronic health record implementation

The Stimulus Bill (ARRA, HITECH) l Starting in 2011, “meaningful” electronic health record (EHR) users are eligible to earn up to $44, 000 in Medicare incentive payments over 5 years and up to $63, 750 under the Medicaid plan over 6 years 1, 2 – Still to be determined n n Electronic exchange of health information n l “Certified” technology that includes e-prescribing Submit info on clinical quality measures Physicians who do not adopt EHR by 2015 will be penalized through % decreases in Medicare reimbursement rates 1 1. US DHHS. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at: http: //tinyurl. com/mavrbs. Accessed on: October 5, 2009. 2. Finnegan B, et al. Boosting health information technology in Medicaid: the potential effect of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Policy Research Brief No. 9. Available at: http: //tinyurl. com/yfpqs 5 c. Accessed on: October 8, 2009.

Optimize to Get to “Meaningful Use” l Reporting quality initiatives – Health maintenance alerts l Exchange of information – Results l Engage the patient – Portal services l E-prescribing

Business of Medicine Is Communications–Patient Portal l l Gather information (past medical, social, and family history) Manage requests – – – l l Appointments Prescription re-issues “Old” telephone triage questions Deliver lab/test results Generate revenue by recall – Follow-up and health maintenance reminders l Get nurses off the phones with FAQs

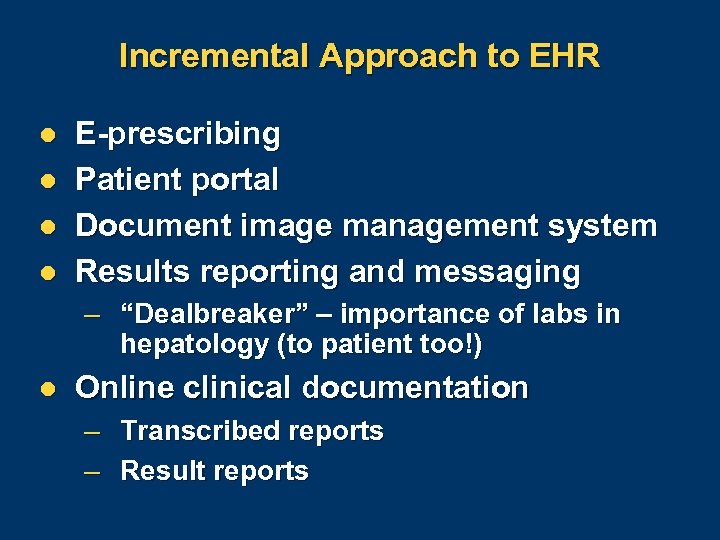

Incremental Approach to EHR l l E-prescribing Patient portal Document image management system Results reporting and messaging – “Dealbreaker” – importance of labs in hepatology (to patient too!) l Online clinical documentation – – Transcribed reports Result reports

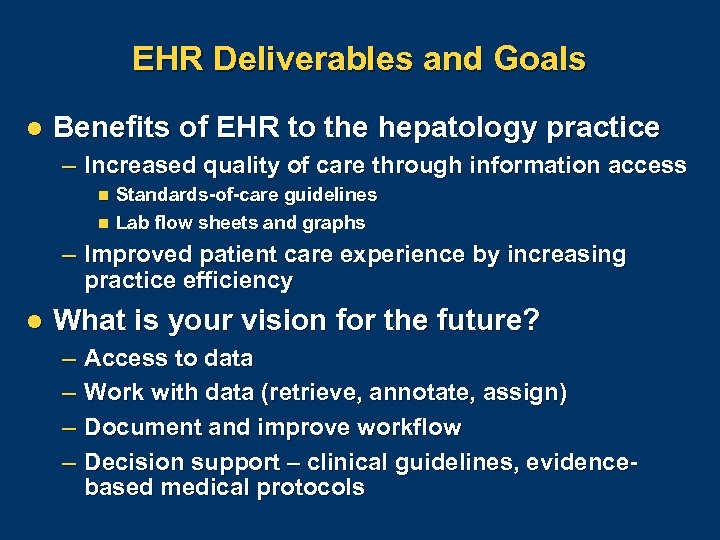

EHR Deliverables and Goals l Benefits of EHR to the hepatology practice – Increased quality of care through information access n n Standards-of-care guidelines Lab flow sheets and graphs – Improved patient care experience by increasing practice efficiency l What is your vision for the future? – – Access to data Work with data (retrieve, annotate, assign) Document and improve workflow Decision support – clinical guidelines, evidencebased medical protocols

No Excuse to Wait Survey findings: Net medical revenue was consistently greater across single-specialty and multispecialty groups using a clinical information solution compared with peers not using similar technologies 1 Technology? Or improved operational efficiency? 1. Gans N. MGMA Connexion. July 2005; 22 23.

Status Quo If we keep doing what we’ve always done, we’ll keep getting what we always got

Conclusions l EHR is a significant undertaking – Tool to improve effectiveness in delivery of care to patients – Approach incrementally n Start e-prescribing this month l Reimbursement environment requires increased efficiency l Models of better-performing practices are available to study and follow

Good, Better, and Best Practices in HCV Management Today Bruce R. Bacon, MD James F. King MD Endowed Chair in Gastroenterology Professor of Internal Medicine Director, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Saint Louis University School of Medicine St. Louis, Missouri

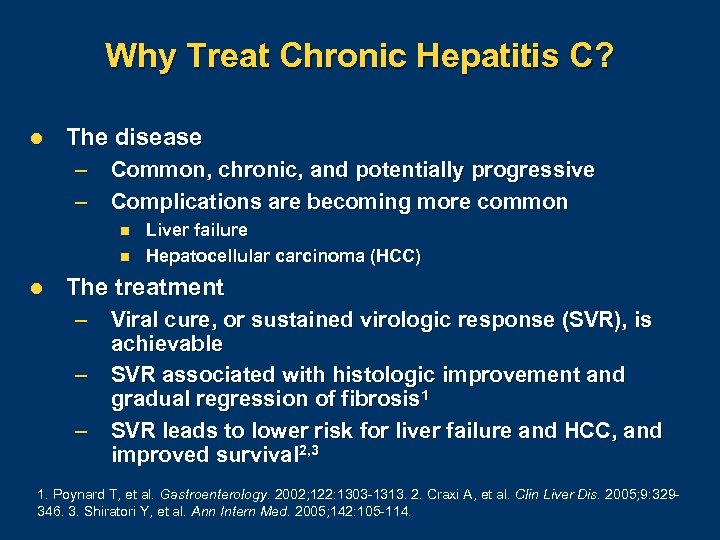

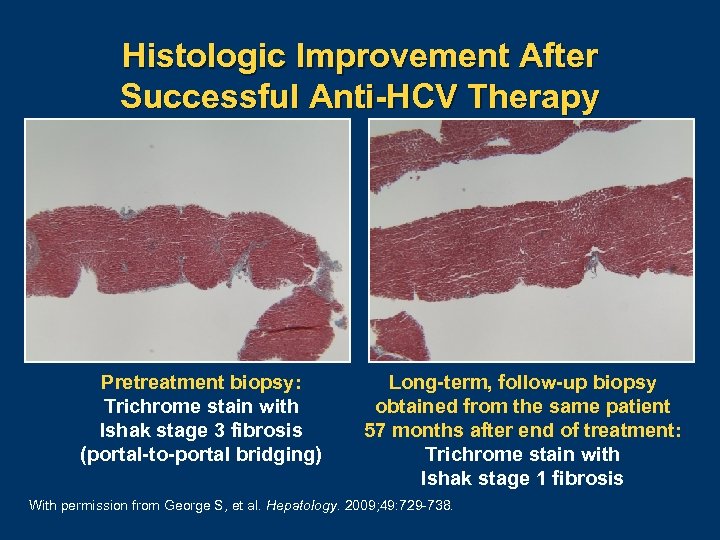

Why Treat Chronic Hepatitis C? l The disease – – Common, chronic, and potentially progressive Complications are becoming more common n n l Liver failure Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) The treatment – – – Viral cure, or sustained virologic response (SVR), is achievable SVR associated with histologic improvement and gradual regression of fibrosis 1 SVR leads to lower risk for liver failure and HCC, and improved survival 2, 3 1. Poynard T, et al. Gastroenterology. 2002; 122: 1303 1313. 2. Craxi A, et al. Clin Liver Dis. 2005; 9: 329 346. 3. Shiratori Y, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2005; 142: 105 114.

Histologic Improvement After Successful Anti-HCV Therapy Pretreatment biopsy: Trichrome stain with Ishak stage 3 fibrosis (portal-to-portal bridging) Long-term, follow-up biopsy obtained from the same patient 57 months after end of treatment: Trichrome stain with Ishak stage 1 fibrosis With permission from George S, et al. Hepatology. 2009; 49: 729 738.

The Problem–Who Gets Treated? Factors Associated with Treatment in a Retrospective Analysis of California Medicaid Dataa Untreated Treated Age >65 years Fibrosis Severe diabetes Renal disease High hospital or ER utilization Alcohol use Age 45– 64 years Male gender Mild disease Liver biopsy Antidepressant use “Other” race/ethnicity a 529 cases and 1058 control patients. Markowitz JS, et al. J Viral Hepat. 2005; 12: 176 185.

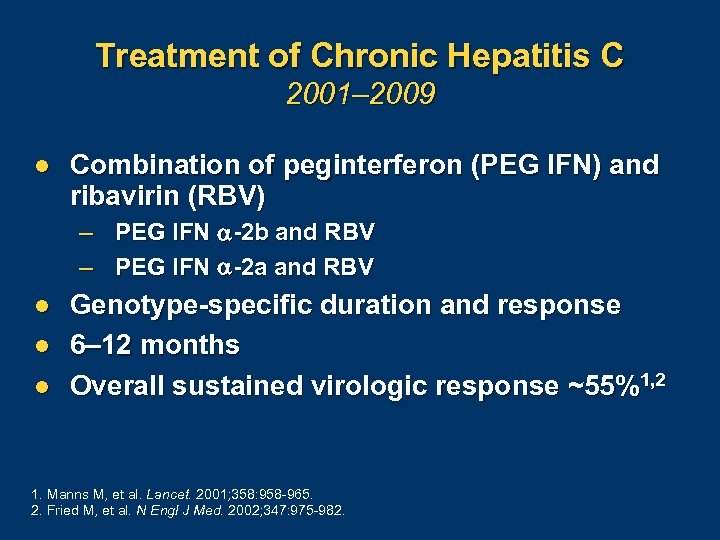

Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C 2001– 2009 l Combination of peginterferon (PEG IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) – PEG IFN -2 b and RBV – PEG IFN -2 a and RBV l l l Genotype-specific duration and response 6– 12 months Overall sustained virologic response ~55%1, 2 1. Manns M, et al. Lancet. 2001; 358: 958 965. 2. Fried M, et al. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347: 975 982.

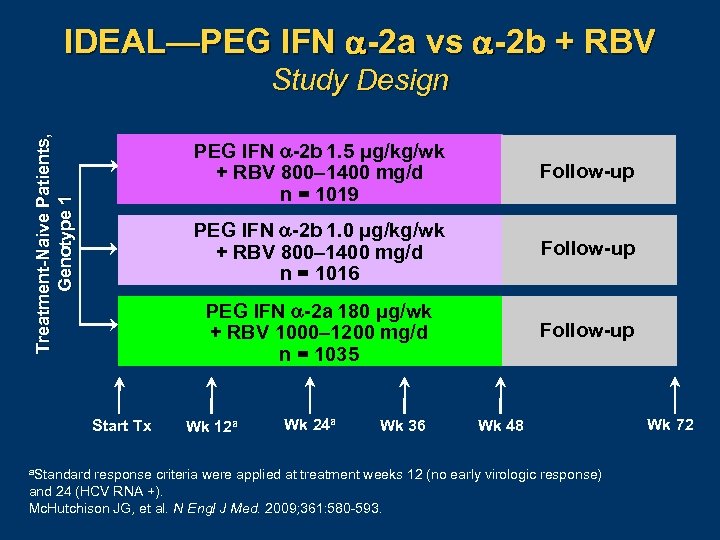

IDEAL—PEG IFN -2 a vs -2 b + RBV Treatment-Naive Patients, Genotype 1 Study Design PEG IFN -2 b 1. 5 μg/kg/wk + RBV 800– 1400 mg/d n = 1019 PEG IFN -2 b 1. 0 μg/kg/wk + RBV 800– 1400 mg/d n = 1016 a. Standard Follow-up PEG IFN -2 a 180 μg/wk + RBV 1000– 1200 mg/d n = 1035 Start Tx Follow-up Wk 12 a Wk 24 a Wk 36 Wk 48 response criteria were applied at treatment weeks 12 (no early virologic response) and 24 (HCV RNA +). Mc. Hutchison JG, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361: 580 593. Wk 72

IDEAL—ETR, SVR, and Relapse Rates Genotype 1 Patients, Intent to Treat Analysis PEG IFN -2 b 1. 5 µg/kg/wk + RBV 800– 1400 mg/d P =. 57 a P =. 20 b a 95% PEG IFN -2 b 1. 0 µg/kg/wk + RBV 800– 1400 mg/d PEG IFN -2 a 180 µg/wk + RBV 1000– 1200 mg/d CI 13. 2% to 2. 8%. b 95% CI 1. 6% to 8. 6%. Abbreviations: ETR, end of treatment response; SVR, sustained virologic response. Mc. Hutchison JG, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361: 580 593.

IDEAL—Adverse Events, Dose Modification, and Treatment Discontinuation PEG IFN -2 b 1. 5 + RBV n = 1019 PEG IFN -2 b 1. 0 + RBV n = 1016 PEG IFN -2 a 180 + RBV n = 1035 Deaths (all/treatment-related) 5/1 (no. ) 1/0 (no. ) 6/1 (no. ) Serious adverse events (AEs) (all/treatment-related) 9%/4% 12%/4% Discontinued due to AEs 13% 10% 13% Dose modification due to AEs 43% 33% 43% 1. 9% 1. 2% 1. 4% Psychiatric disorders Hematologic parameters Neutrophil count (<750/mm 3/<500/mm 3) 22%/3% 14%/2% 27%/6% Hemoglobin (<10 g/d. L/<8. 5 g/d. L) 31%/3% 25%/2% 30%/4% Erythropoietin use 16% 14% 17% With permission from Mc. Hutchison JG, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361: 580 593.

Maximizing Response to PEG IFN/RBV in HCV Genotype 1 -Infected Patients l Evaluate and correct modifiable factors prior to therapy – Insulin resistance and obesity – Depression l Deliver expert treatment – Adequate RBV dose >13 mg/kg/day 1 – Consider extension of therapy in “slow” responders – Aggressively manage side effects 1. Mc. Hutchison JG, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361: 580 593.

Maximizing Response to PEG IFN/RBV in HCV Genotype 1 -Infected Patients l Treatment response at weeks 4 and 12 are more predictive than baseline factors 1 -3 – May help tailor treatment to improve response or curtail therapy when it is futile – Rapid virologic response is not a stopping rule 1. Fried MW, et al. J Hepatol. 2008; 48: S 5. 2. Ferenci P, et al. J Hepatol. 2005; 43: 425 433. 3. Davis GL, et al. Hepatology. 2003; 38: 645 652.

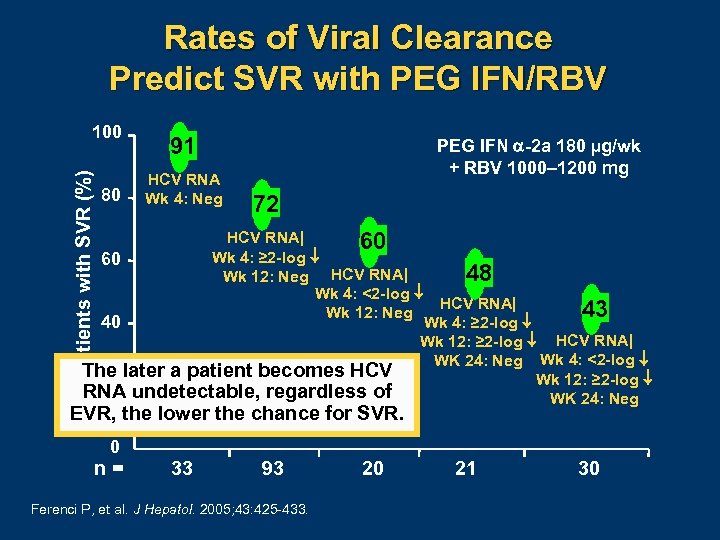

Rates of Viral Clearance Predict SVR with PEG IFN/RBV Patients with SVR (%) 100 80 91 HCV RNA Wk 4: Neg PEG IFN -2 a 180 µg/wk + RBV 1000– 1200 mg 72 HCV RNA| 60 Wk 4: ≥ 2 -log 60 48 Wk 12: Neg HCV RNA| Wk 4: <2 -log HCV RNA| 43 Wk 12: Neg Wk 4: ≥ 2 -log 40 Wk 12: ≥ 2 -log HCV RNA| WK 24: Neg Wk 4: <2 -log The later a patient becomes HCV Wk 12: ≥ 2 -log 20 RNA undetectable, regardless of WK 24: Neg EVR, the lower the chance for SVR. 0 n= 33 93 Ferenci P, et al. J Hepatol. 2005; 43: 425 433. 20 21 30

Response-Guided Therapy l l HCV RNA determination is essential at week 4 (RVR) and week 12 (EVR) Shortened therapy vs standard therapy vs extended therapy – Genotype – RVR or EVR – Viral load l Response-guided therapy will be a prominent theme with the advent of novel therapies

SVR with Standard vs Extended Therapy in Genotype-1 Patients with Failure of RVR or Slow Response Standard 48 wk 100 SVR (%) 80 60 Randomized if non-RVR P =. 003 Retrospective subset analysis of patients with RNA+ at 12 wk P =. 04 Extended 72 wk Randomization of slow responders P =. 03 44 40 38 52 21 29 18 17 149 P =. 07 38 28 20 n= Randomization of moderately slow responders: RNA+ at 8 wk RNA– at 12 wk 64 142 PEG IFN α-2 a + RBV 8001 100 106 PEG IFN α-2 a + RBV 8002 49 PEG IFN α-2 b + RBV 800– 14003 52 PEG IFN α-2 a + RBV 1000– 12004 1. Sanchez Tapias J, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006; 131: 451 460. 2. Berg T, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006; 130: 1086 1097. 3. Pearlman BL, et al. Hepatology. 2007; 46: 1688 1694. 4. Mangia A, et al. Hepatology. 2008; 47: 43 50. Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson.

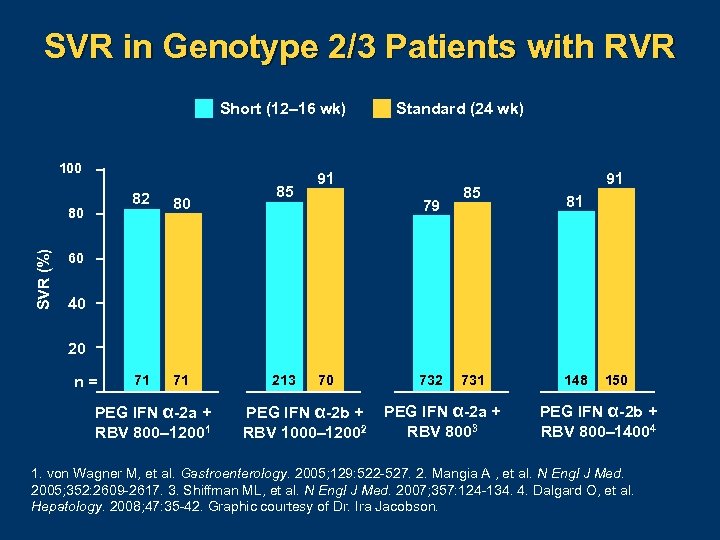

SVR in Genotype 2/3 Patients with RVR Short (12– 16 wk) 100 82 SVR (%) 80 80 71 71 85 Standard (24 wk) 91 79 85 91 81 60 40 20 n= PEG IFN α-2 a + RBV 800– 12001 213 70 PEG IFN α-2 b + RBV 1000– 12002 731 PEG IFN α-2 a + RBV 8003 148 150 PEG IFN α-2 b + RBV 800– 14004 1. von Wagner M, et al. Gastroenterology. 2005; 129: 522 527. 2. Mangia A , et al. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352: 2609 2617. 3. Shiffman ML, et al. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357: 124 134. 4. Dalgard O, et al. Hepatology. 2008; 47: 35 42. Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson.

Reasons for Identifying Metabolic Syndrome and Fatty Liver Coexistence in Hepatitis C l l Insulin resistance, steatosis and steatohepatitis decrease SVR 1, 2 Steatosis is associated with fibrosis progression 2 Insulin resistance is associated with higher viral loads 3 Insulin resistance likely inhibits innate immune system function 4 1. Romero Gomez M, et al. Gastroenterology. 2005; 128: 636 641. 2. Poynard T, et al. Hepatology. 2003; 38: 75 85. 3. Hsu CS, et al. Liver Int. 2008; 28: 271 277. 4. Fernandez Real JM, Pickup JC. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008; 19: 10 16.

Impact of Insulin Resistance on SVR in Genotype-1 Patients PEG IFN + RBVa P =. 007 With Insulin Resistance Without Insulin Resistance PEG IFN 2 a 180 g/wk or PEG IFN 2 b 1. 5 g/kg/wk + RBV 800– 1200/d. Romero Gomez M, et al. Gastroenterology. 2005; 128: 636 641. Graphic courtesy of Dr. Bruce Bacon. a. Treatment:

Reduction of Insulin Resistance With Successful HCV Therapy Data from Longitudinal Study Within Lead-In Phase of HALT-C Trial to Evaluate Change in IR with HCV Therapy N = 96; genotype non 3 prior nonresponders with evidence of advanced fibrosis and no uncontrolled diabetes Group Based on Status at Week 20 of PEG IFN/RBV HOMA 2 -IRa Change at Week 20 b Null responders (n = 38) Partial responders (n = 37) Responders (n = 21) +0. 18 – 0. 9 – 2. 23 a. Mean values; b. P =. 017 Abbreviations: HALT C, Hepatitis C Antiviral Long Term Treatment Against Cirrhosis; HOMA, Homeostasis model assessment; IR, insulin resistance. Delgado Borrego A, et al. Hepatology 2008; 48: 433 A.

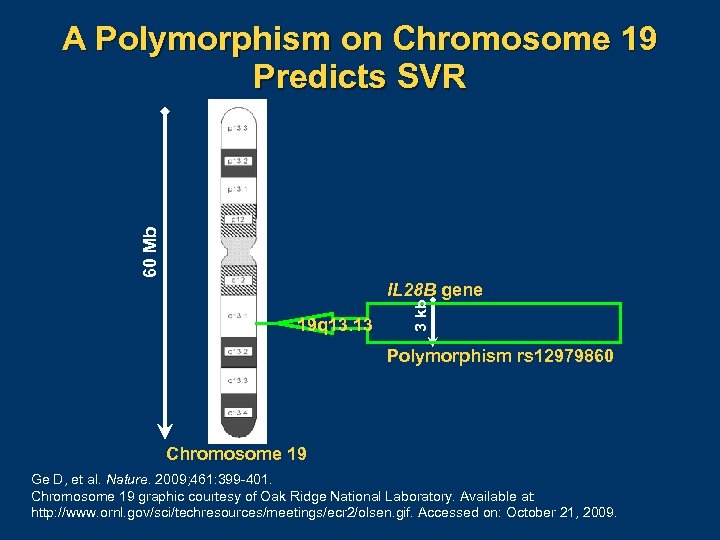

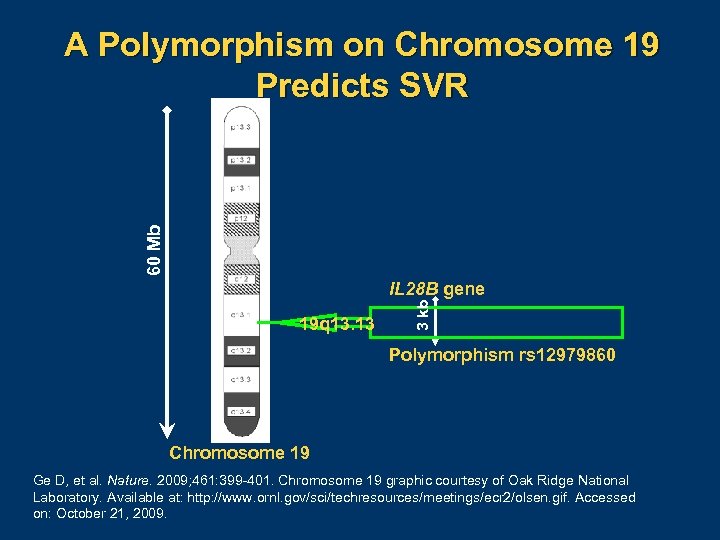

60 Mb A Polymorphism on Chromosome 19 Predicts SVR 19 q 13. 13 3 kb IL 28 B gene Polymorphism rs 12979860 Chromosome 19 Ge D, et al. Nature. 2009; 461: 399 401. Chromosome 19 graphic courtesy of Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Available at: http: //www. ornl. gov/sci/techresources/meetings/ecr 2/olsen. gif. Accessed on: October 21, 2009.

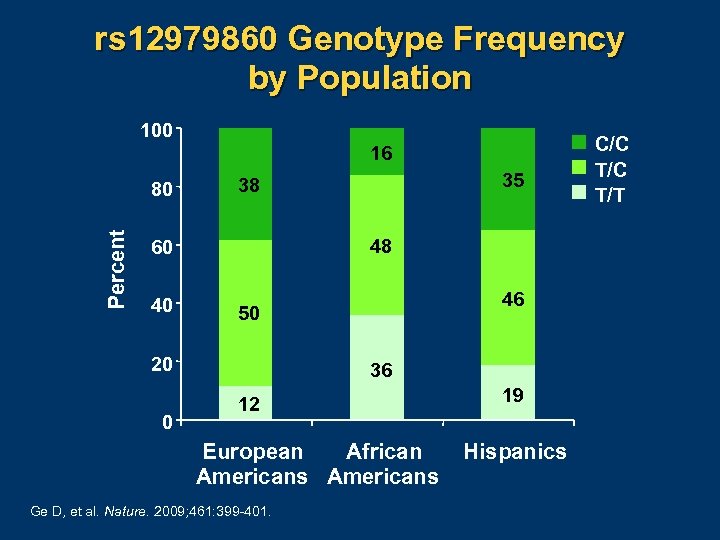

rs 12979860 Genotype Frequency by Population 100 16 Percent 80 48 60 40 46 50 20 0 35 38 36 12 European African Americans Ge D, et al. Nature. 2009; 461: 399 401. 19 Hispanics C/C T/T

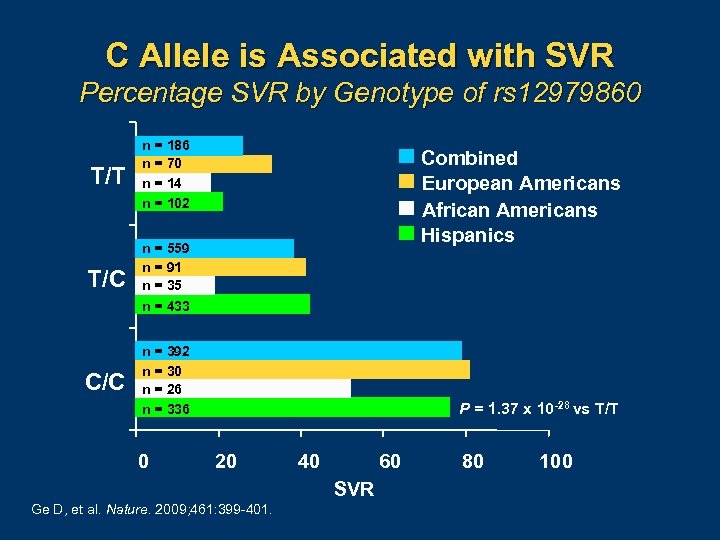

C Allele is Associated with SVR Percentage SVR by Genotype of rs 12979860 T/T n = 186 n = 70 n = 14 n = 102 T/C n = 559 n = 91 n = 35 n = 433 C/C n = 392 n = 30 n = 26 n = 336 0 Combined European Americans African Americans Hispanics P = 1. 37 x 10 -28 vs T/T 20 40 60 SVR Ge D, et al. Nature. 2009; 461: 399 401. 80 100

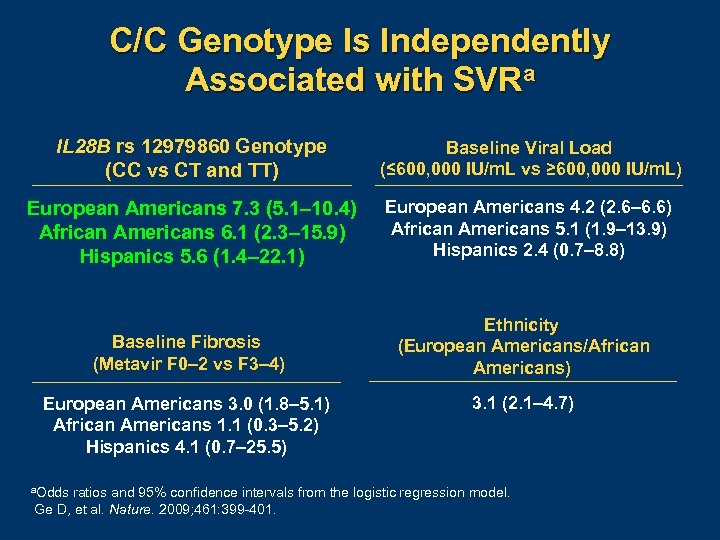

C/C Genotype Is Independently Associated with SVRa IL 28 B rs 12979860 Genotype (CC vs CT and TT) Baseline Viral Load (≤ 600, 000 IU/m. L vs ≥ 600, 000 IU/m. L) European Americans 7. 3 (5. 1– 10. 4) African Americans 6. 1 (2. 3– 15. 9) Hispanics 5. 6 (1. 4– 22. 1) European Americans 4. 2 (2. 6– 6. 6) African Americans 5. 1 (1. 9– 13. 9) Hispanics 2. 4 (0. 7– 8. 8) Baseline Fibrosis (Metavir F 0– 2 vs F 3– 4) Ethnicity (European Americans/African Americans) European Americans 3. 0 (1. 8– 5. 1) African Americans 1. 1 (0. 3– 5. 2) Hispanics 4. 1 (0. 7– 25. 5) a. Odds 3. 1 (2. 1– 4. 7) ratios and 95% confidence intervals from the logistic regression model. Ge D, et al. Nature. 2009; 461: 399 401.

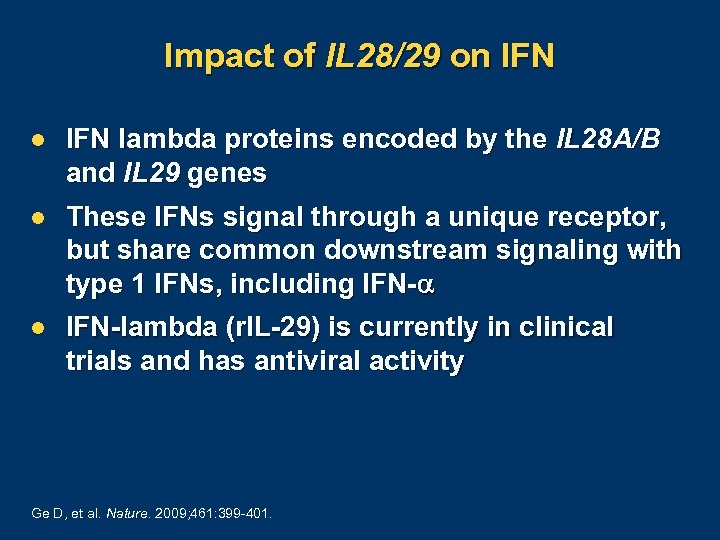

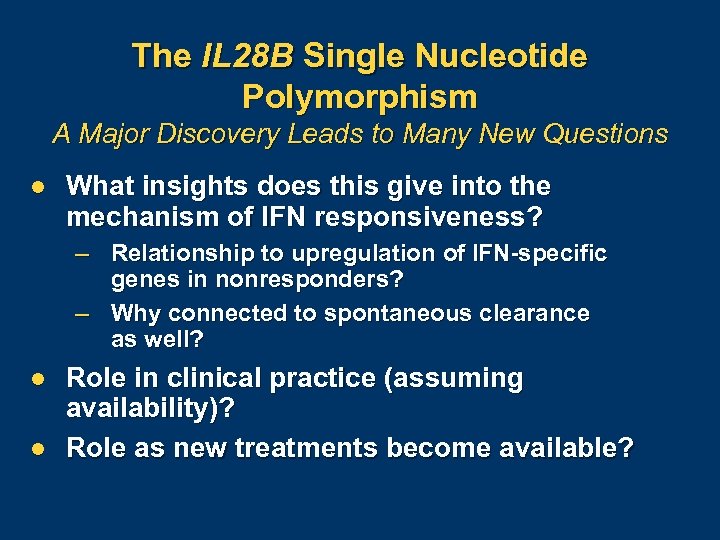

Impact of IL 28/29 on IFN lambda proteins encoded by the IL 28 A/B and IL 29 genes l These IFNs signal through a unique receptor, but share common downstream signaling with type 1 IFNs, including IFN- l IFN-lambda (r. IL-29) is currently in clinical trials and has antiviral activity Ge D, et al. Nature. 2009; 461: 399 401.

Impact of IL 28/29 on STAT-C Therapy l Impact of testing for IL 28 B will be important with PEG IFN and RBV l IL 28 B testing will need to be investigated when using STAT-C agents

Conclusions l PEG IFN plus RBV is the current standard-of -care therapy – Overall SVR about 55% l l l Insulin resistance has a significant impact on SVR Response-guided therapy is important now and will be a prominent theme with novel therapies IL 28 B status influences effectiveness of IFN

The Future of Anti-HCV Treatment— Emerging Therapies and Their Integration into the Medical Office of the Future Nezam H. Afdhal, MD Associate Professor of Medicine Harvard Medical School Chief of Hepatology Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Boston, Massachusetts

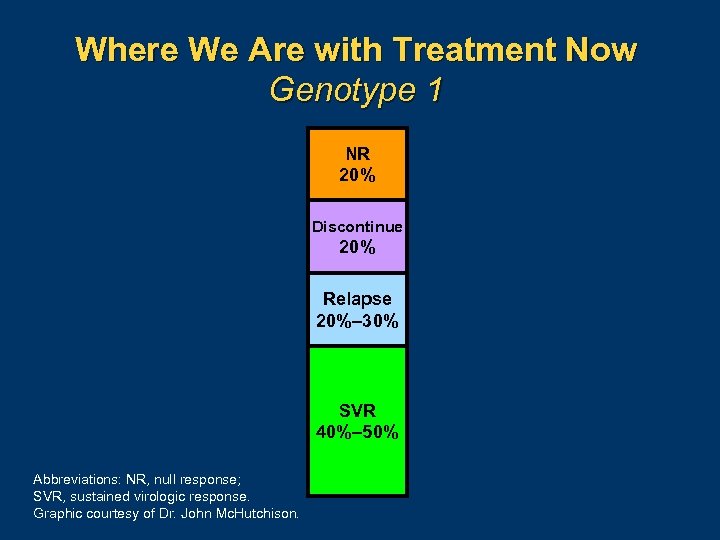

Where We Are with Treatment Now Genotype 1 NR 20% Discontinue 20% Relapse 20%– 30% SVR 40%– 50% Abbreviations: NR, null response; SVR, sustained virologic response. Graphic courtesy of Dr. John Mc. Hutchison.

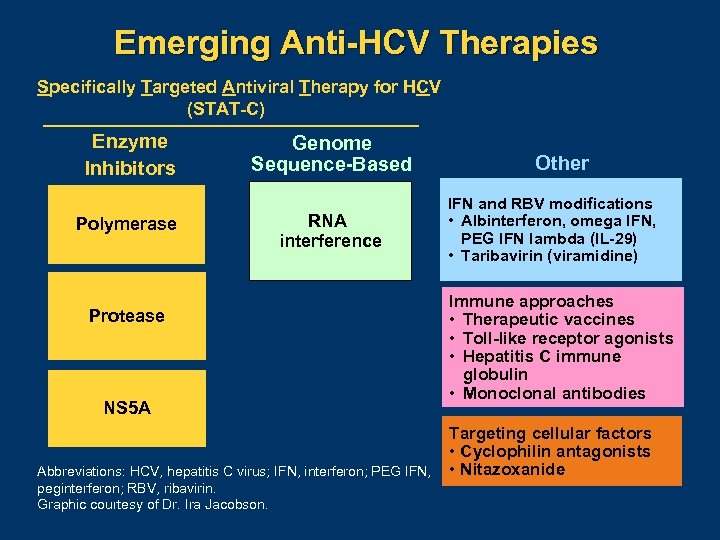

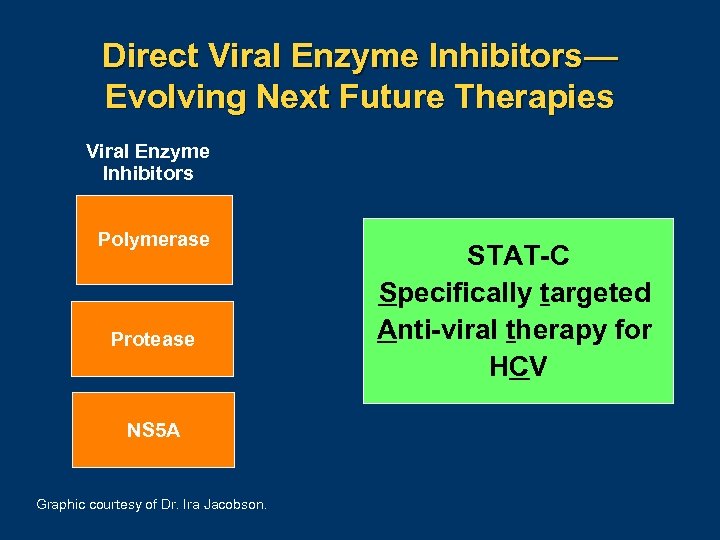

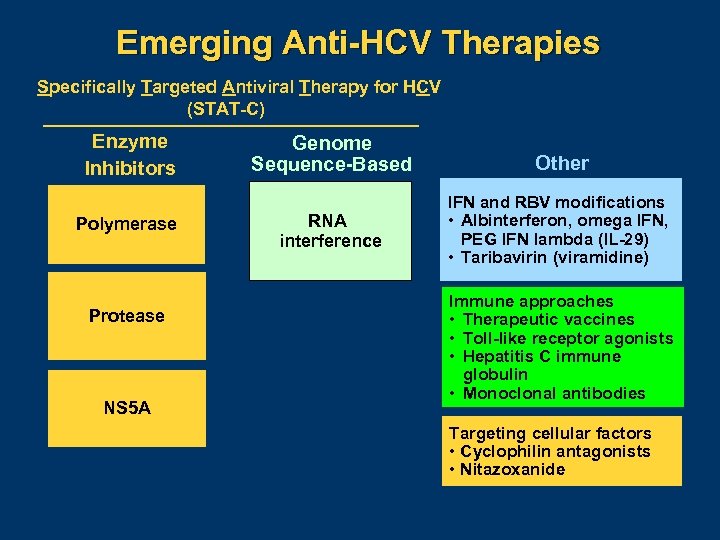

Emerging Anti-HCV Therapies Specifically Targeted Antiviral Therapy for HCV (STAT-C) Enzyme Inhibitors Polymerase Genome Sequence-Based RNA interference Protease NS 5 A Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; IFN, interferon; PEG IFN, peginterferon; RBV, ribavirin. Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson. Other IFN and RBV modifications • Albinterferon, omega IFN, PEG IFN lambda (IL-29) • Taribavirin (viramidine) Immune approaches • Therapeutic vaccines • Toll-like receptor agonists • Hepatitis C immune globulin • Monoclonal antibodies Targeting cellular factors • Cyclophilin antagonists • Nitazoxanide

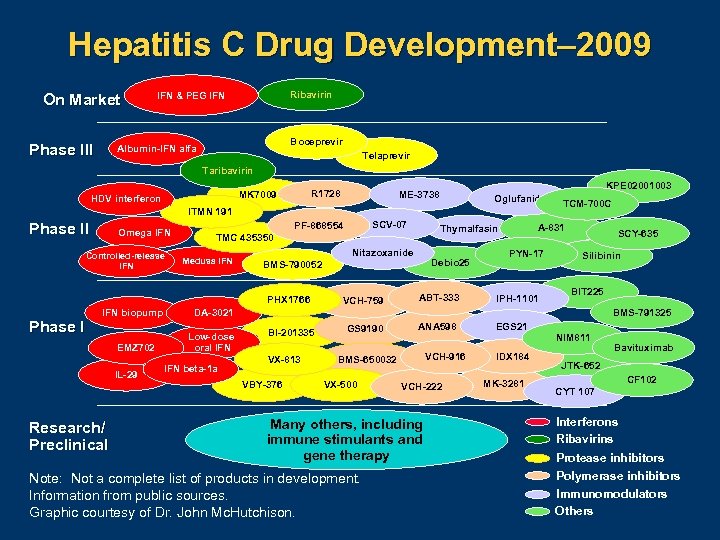

Hepatitis C Drug Development– 2009 On Market Phase III Ribavirin IFN & PEG IFN Boceprevir Albumin-IFN alfa Telaprevir Taribavirin R 1728 MK 7009 HDV interferon KPE 02001003 ME-3738 Oglufanide ITMN 191 Phase II Omega IFN Controlled-release IFN Medusa IFN Nitazoxanide Phase I EMZ 702 IL-29 Research/ Preclinical Debio 25 BMS-790052 VCH-759 A-831 Thymalfasin TMC 435350 PHX 1766 IFN biopump SCV-07 PF-868554 ABT-333 TCM-700 C PYN-17 IPH-1101 SCY-635 Silibinin BIT 225 BMS-791325 DA-3021 Low-dose oral IFN beta-1 a BI-201335 VX-813 VBY-376 GS 9190 ANA 598 NIM 811 VCH-916 BMS-650032 VX-500 VCH-222 Many others, including immune stimulants and gene therapy Note: Not a complete list of products in development. Information from public sources. Graphic courtesy of Dr. John Mc. Hutchison. EGS 21 IDX 184 MK-3281 Bavituximab JTK-652 CF 102 CYT 107 Interferons Ribavirins Protease inhibitors Polymerase inhibitors Immunomodulators Others

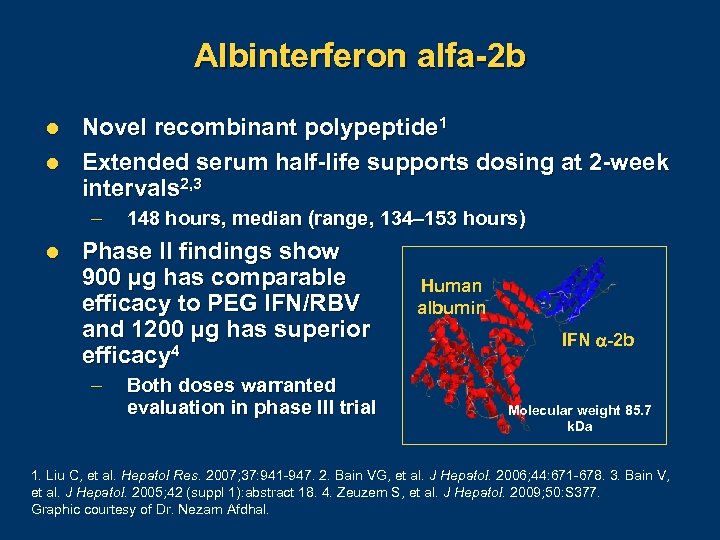

Albinterferon alfa-2 b l l Novel recombinant polypeptide 1 Extended serum half-life supports dosing at 2 -week intervals 2, 3 – l 148 hours, median (range, 134– 153 hours) Phase II findings show 900 µg has comparable efficacy to PEG IFN/RBV and 1200 µg has superior efficacy 4 – Both doses warranted evaluation in phase III trial Human albumin IFN -2 b Molecular weight 85. 7 k. Da 1. Liu C, et al. Hepatol Res. 2007; 37: 941 947. 2. Bain VG, et al. J Hepatol. 2006; 44: 671 678. 3. Bain V, et al. J Hepatol. 2005; 42 (suppl 1): abstract 18. 4. Zeuzem S, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50: S 377. Graphic courtesy of Dr. Nezam Afdhal.

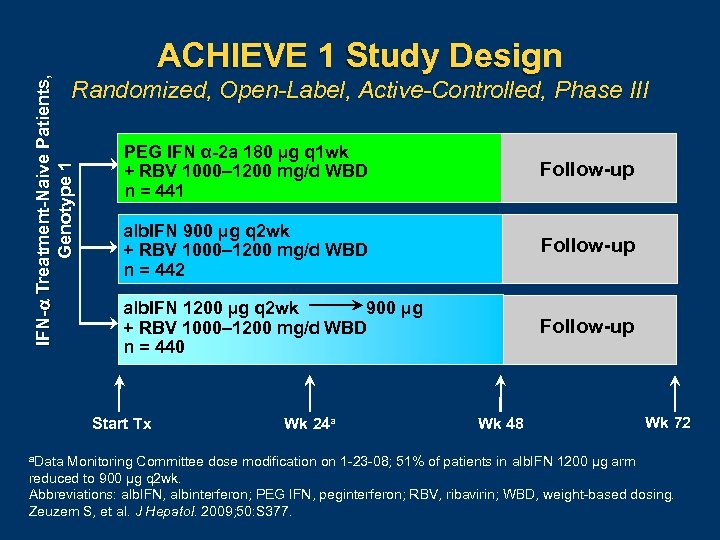

IFN- Treatment-Naive Patients, Genotype 1 ACHIEVE 1 Study Design Randomized, Open-Label, Active-Controlled, Phase III PEG IFN α-2 a 180 µg q 1 wk + RBV 1000– 1200 mg/d WBD n = 441 Follow-up alb. IFN 900 µg q 2 wk + RBV 1000– 1200 mg/d WBD n = 442 Follow-up 900 µg alb. IFN 1200 µg q 2 wk + RBV 1000– 1200 mg/d WBD n = 440 Follow-up Start Tx a. Data Wk 24 a Wk 48 Wk 72 Monitoring Committee dose modification on 1 23 08; 51% of patients in alb. IFN 1200 µg arm reduced to 900 µg q 2 wk. Abbreviations: alb. IFN, albinterferon; PEG IFN, peginterferon; RBV, ribavirin; WBD, weight based dosing. Zeuzem S, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50: S 377.

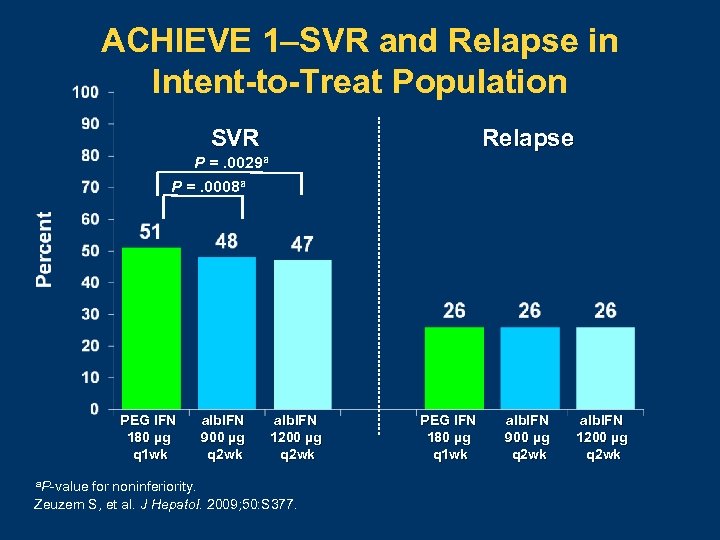

ACHIEVE 1–SVR and Relapse in Intent-to-Treat Population Relapse SVR P =. 0029 a P =. 0008 a PEG IFN 180 µg q 1 wk a. P value alb. IFN 900 µg q 2 wk alb. IFN 1200 µg q 2 wk for noninferiority. Zeuzem S, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50: S 377. PEG IFN 180 µg q 1 wk alb. IFN 900 µg q 2 wk alb. IFN 1200 µg q 2 wk

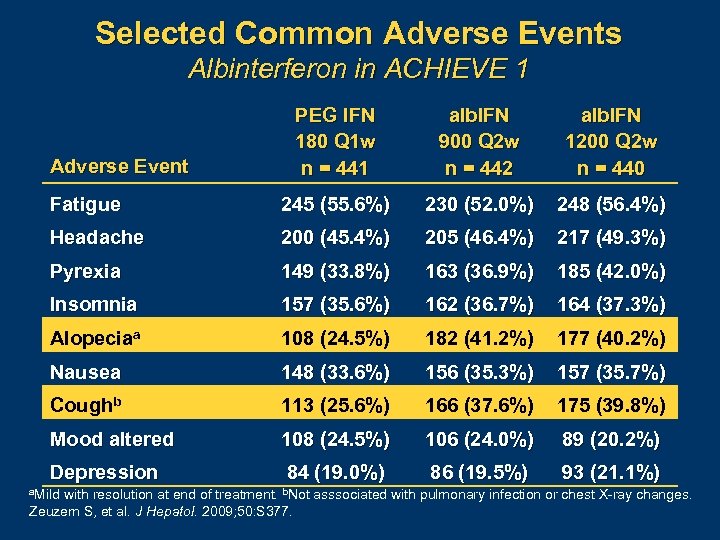

Selected Common Adverse Events Albinterferon in ACHIEVE 1 PEG IFN 180 Q 1 w n = 441 alb. IFN 900 Q 2 w n = 442 alb. IFN 1200 Q 2 w n = 440 Fatigue 245 (55. 6%) 230 (52. 0%) 248 (56. 4%) Headache 200 (45. 4%) 205 (46. 4%) 217 (49. 3%) Pyrexia 149 (33. 8%) 163 (36. 9%) 185 (42. 0%) Insomnia 157 (35. 6%) 162 (36. 7%) 164 (37. 3%) Alopeciaa 108 (24. 5%) 182 (41. 2%) 177 (40. 2%) Nausea 148 (33. 6%) 156 (35. 3%) 157 (35. 7%) Coughb 113 (25. 6%) 166 (37. 6%) 175 (39. 8%) Mood altered 108 (24. 5%) 106 (24. 0%) 89 (20. 2%) Depression 84 (19. 0%) 86 (19. 5%) 93 (21. 1%) Adverse Event a. Mild with resolution at end of treatment. b. Not asssociated with pulmonary infection or chest X ray changes. Zeuzem S, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50: S 377.

Direct Viral Enzyme Inhibitors— Evolving Next Future Therapies Viral Enzyme Inhibitors Polymerase Protease NS 5 A Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson. STAT-C Specifically targeted Anti-viral therapy for HCV

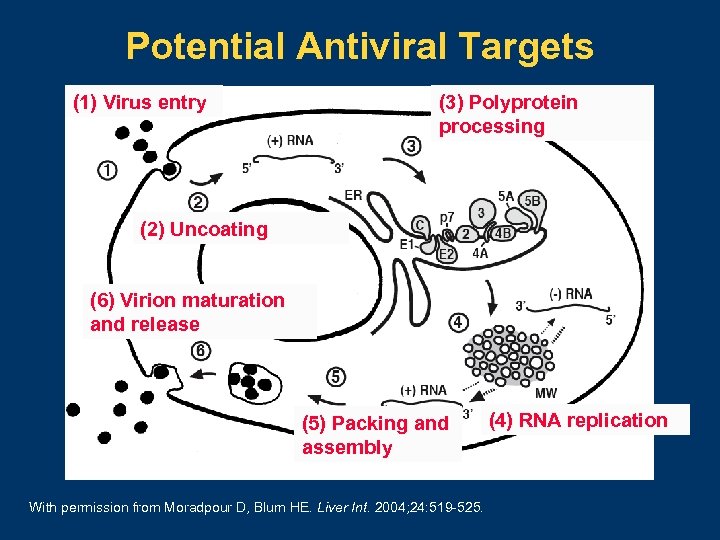

Potential Antiviral Targets (1) Virus entry (3) Polyprotein processing (2) Uncoating (6) Virion maturation and release (5) Packing and assembly With permission from Moradpour D, Blum HE. Liver Int. 2004; 24: 519 525. (4) RNA replication

Adherence to Antiviral Therapy Association Between Virologic Failure and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Patients with HIV 1 Doses Taken in Virahep-C Study 2 Physicians predicted adherence incorrectly for ~41% of patients 1 1. Paterson DL, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2000; 133: 21 30. 2. Conjeevaram HS, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006; 131: 470 477. Left graphic with permission from Paterson DL, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2000; 133: 21 30. Right graphic courtesy of Dr. Nezam Afdhal.

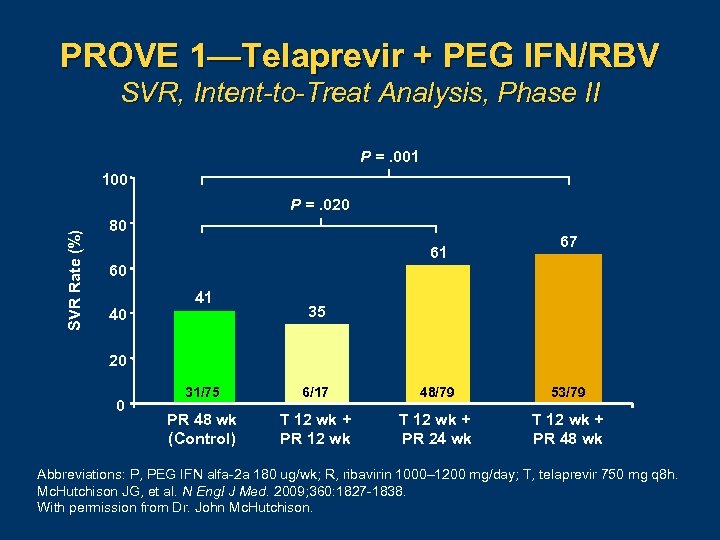

PROVE 1—Telaprevir + PEG IFN/RBV SVR, Intent-to-Treat Analysis, Phase II P =. 001 100 SVR Rate (%) P =. 020 80 61 60 40 41 67 35 20 0 31/75 6/17 48/79 53/79 PR 48 wk (Control) T 12 wk + PR 12 wk T 12 wk + PR 24 wk T 12 wk + PR 48 wk Abbreviations: P, PEG IFN alfa 2 a 180 ug/wk; R, ribavirin 1000– 1200 mg/day; T, telaprevir 750 mg q 8 h. Mc. Hutchison JG, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360: 1827 1838. With permission from Dr. John Mc. Hutchison.

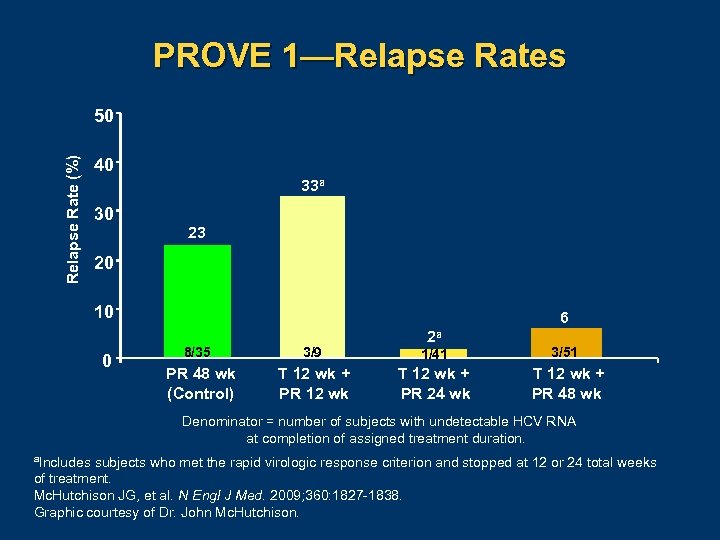

PROVE 1—Relapse Rates Relapse Rate (%) 50 40 33 a 30 23 20 10 0 6 2 a 8/35 3/9 1/41 3/51 PR 48 wk (Control) T 12 wk + PR 12 wk T 12 wk + PR 24 wk T 12 wk + PR 48 wk Denominator = number of subjects with undetectable HCV RNA at completion of assigned treatment duration. a. Includes subjects who met the rapid virologic response criterion and stopped at 12 or 24 total weeks of treatment. Mc. Hutchison JG, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360: 1827 1838. Graphic courtesy of Dr. John Mc. Hutchison.

Can We Dispense with Ribavirin? PROVE 2 PR 48 control (n = 82) T 12 PR 24 (n = 81) T 12 PR 12 (n = 82) T 12 P 12 (n = 78) Abbreviations: P, PEG IFN alfa 2 a 180 ug/wk; R, ribavirin 1000– 1200 mg/day; T, telaprevir 750 mg q 8 h. Hézode C, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360: 1839 1850.

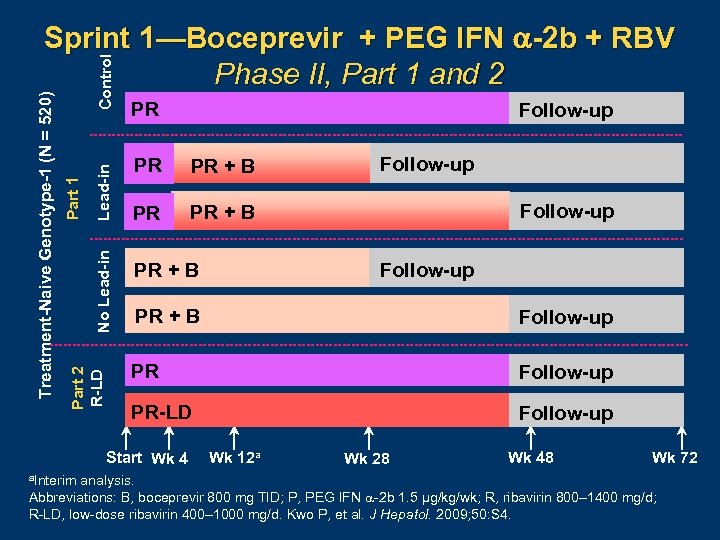

Control Lead-in No Lead-in Part 1 Part 2 R-LD Treatment-Naive Genotype-1 (N = 520) Sprint 1—Boceprevir + PEG IFN -2 b + RBV Phase II, Part 1 and 2 PR PR PR + B PR Follow-up PR + B Follow-up PR-LD Follow-up Start Wk 4 a. Interim Follow-up Wk 12 a Wk 28 Wk 48 Wk 72 analysis. Abbreviations: B, boceprevir 800 mg TID; P, PEG IFN 2 b 1. 5 µg/kg/wk; R, ribavirin 800– 1400 mg/d; R LD, low dose ribavirin 400– 1000 mg/d. Kwo P, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50: S 4.

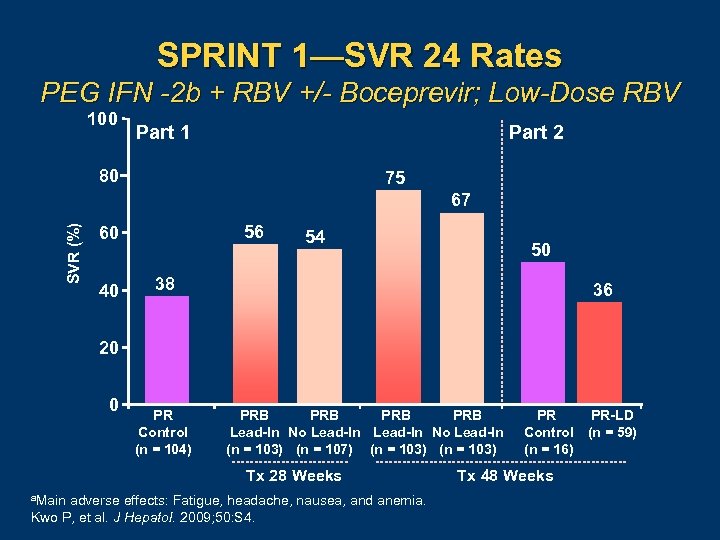

SPRINT 1—SVR 24 Rates PEG IFN -2 b + RBV +/- Boceprevir; Low-Dose RBV 100 Part 1 Part 2 80 75 SVR (%) 67 56 60 40 54 50 38 36 20 0 PR Control (n = 104) PRB PRB Lead-In No Lead-In (n = 103) (n = 107) (n = 103) Tx 28 Weeks a. Main adverse effects: Fatigue, headache, nausea, and anemia. Kwo P, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50: S 4. PR Control (n = 16) Tx 48 Weeks PR-LD (n = 59)

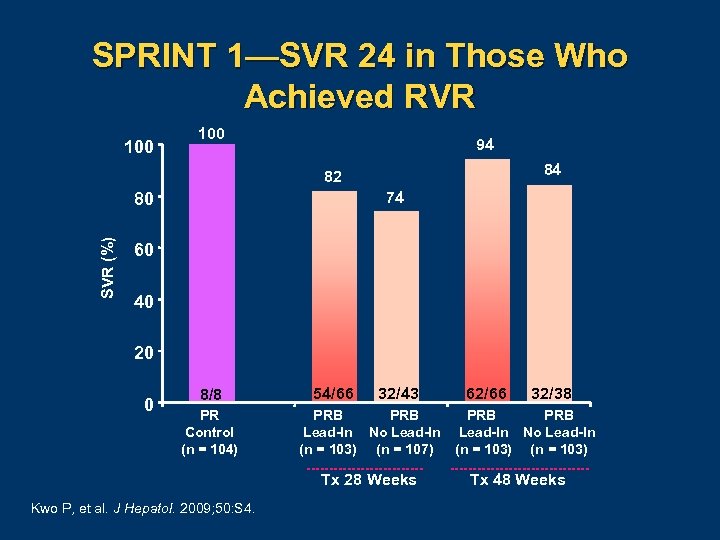

SPRINT 1—SVR 24 in Those Who Achieved RVR 100 94 84 82 74 SVR (%) 80 60 40 20 0 8/8 PR Control (n = 104) 54/66 32/43 PRB Lead-In No Lead-In (n = 103) (n = 107) Tx 28 Weeks Kwo P, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50: S 4. 62/66 32/38 PRB Lead-In No Lead-In (n = 103) Tx 48 Weeks

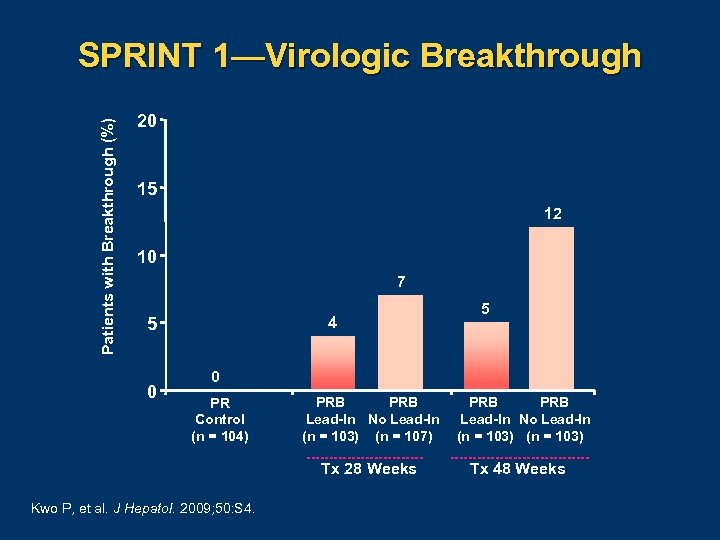

Patients with Breakthrough (%) SPRINT 1—Virologic Breakthrough 20 15 12 10 7 4 5 0 PR Control (n = 104) PRB Lead-In No Lead-In (n = 103) (n = 107) Tx 28 Weeks Kwo P, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50: S 4. PRB Lead-In No Lead-In (n = 103) Tx 48 Weeks

PROVE 3—Telaprevir + PEG IFN +/- RBV by Prior Response and Treatment Groupa SVR (%) T 12/ PR 24 Treatment failures a. Intent to treat T 24/ PR 48 T 24/ P 24 PR 48 51 53 24 14 analysis. Mc. Hutchison JG, et al. 60 th AASLD. Boston, MA. October 30 November 3, 2009. Abstract 66.

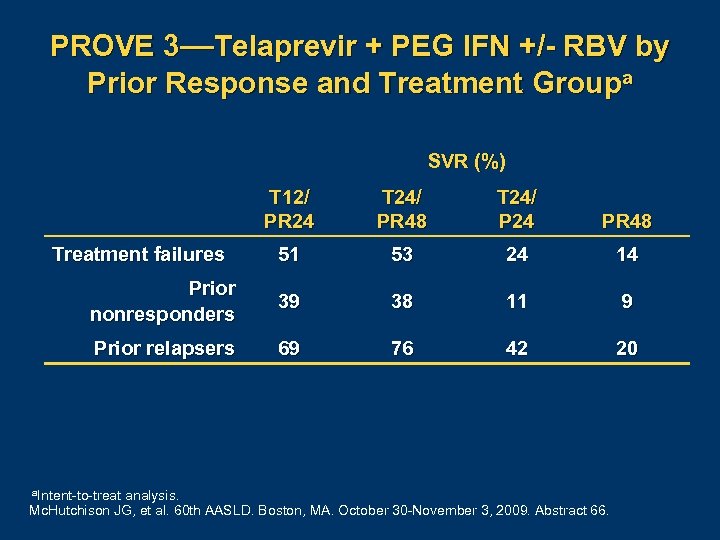

PROVE 3—Telaprevir + PEG IFN +/- RBV by Prior Response and Treatment Groupa SVR (%) T 12/ PR 24 T 24/ PR 48 T 24/ P 24 PR 48 51 53 24 14 Prior nonresponders 39 38 11 9 Prior relapsers 69 76 42 20 Treatment failures a. Intent to treat analysis. Mc. Hutchison JG, et al. 60 th AASLD. Boston, MA. October 30 November 3, 2009. Abstract 66.

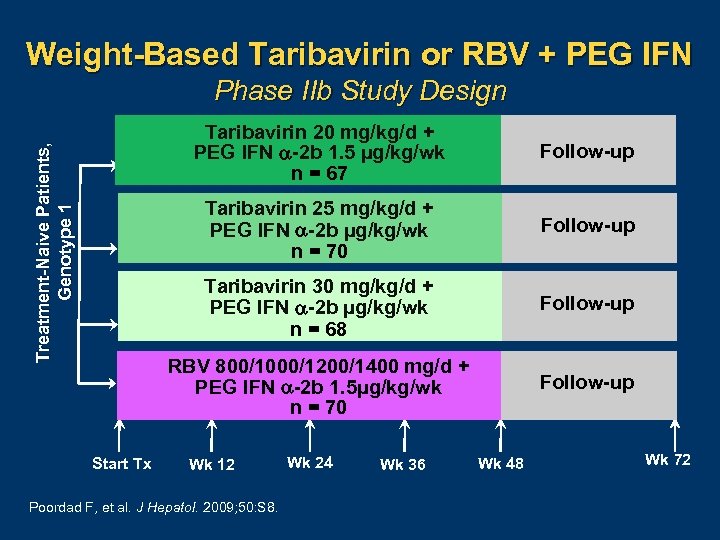

Weight-Based Taribavirin or RBV + PEG IFN Phase IIb Study Design Follow-up Taribavirin 30 mg/kg/d + PEG IFN -2 b µg/kg/wk n = 68 Follow-up RBV 800/1000/1200/1400 mg/d + PEG IFN -2 b 1. 5µg/kg/wk n = 70 Start Tx Follow-up Taribavirin 25 mg/kg/d + PEG IFN -2 b µg/kg/wk n = 70 Treatment-Naive Patients, Genotype 1 Taribavirin 20 mg/kg/d + PEG IFN -2 b 1. 5 µg/kg/wk n = 67 Follow-up Wk 12 Poordad F, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50: S 8. Wk 24 Wk 36 Wk 48 Wk 72

Weight-Based Taribavirin or RBV + PEG IFN Virologic Response at Week 4, 12, 48 and SVR 12 a TBV 20 mg/kg + PEG IFN TBV 25 mg/kg + PEG IFN TBV 30 mg/kg + PEG IFN RBV 800– 1400 mg + PEG IFN a. ITT population. Abbreviation: TBV, taribavirin. Poordad F, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50: S 8.

Taribavirin vs RBV + PEG IFN -2 b Hemoglobin Event Rate TBV 20 mg/kg + PEG IFN TBV 25 mg/kg + PEG IFN TBV 30 mg/kg + PEG IFN RBV 800– 1400 mg + PEG IFN Poordad F, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50: S 8. P ≤. 05 for TBV 20 mg/kg and TBV 25 mg/kg vs RBV

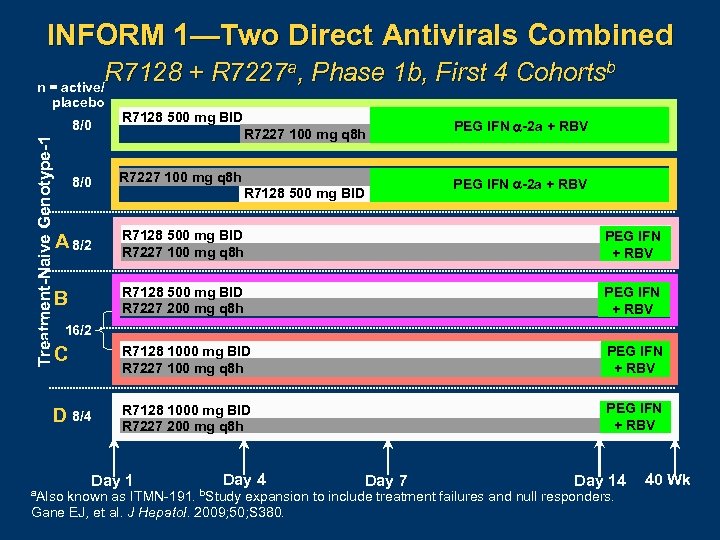

INFORM 1—Two Direct Antivirals Combined R 7128 + R 7227 a, Phase 1 b, First 4 Cohortsb n = active/ placebo Treatment-Naive Genotype-1 8/0 R 7128 500 mg BID R 7227 100 mg q 8 h PEG IFN -2 a + RBV 8/0 R 7227 100 mg q 8 h A 8/2 R 7128 500 mg BID R 7227 100 mg q 8 h PEG IFN + RBV B R 7128 500 mg BID R 7227 200 mg q 8 h PEG IFN + RBV C R 7128 1000 mg BID R 7227 100 mg q 8 h PEG IFN + RBV D 8/4 R 7128 1000 mg BID R 7227 200 mg q 8 h PEG IFN + RBV R 7128 500 mg BID PEG IFN -2 a + RBV 16/2 a. Also Day 1 Day 4 b. Study Day 7 Day 14 known as ITMN 191. expansion to include treatment failures and null responders. Gane EJ, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50; S 380. 40 Wk

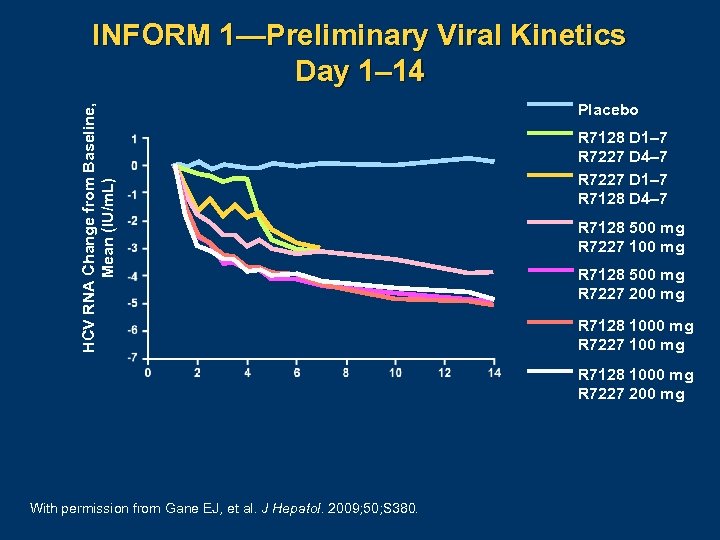

HCV RNA Change from Baseline, Mean (IU/m. L) INFORM 1—Preliminary Viral Kinetics Day 1– 14 Placebo R 7128 D 1– 7 R 7227 D 4– 7 R 7227 D 1– 7 R 7128 D 4– 7 R 7128 500 mg R 7227 100 mg R 7128 500 mg R 7227 200 mg R 7128 1000 mg R 7227 100 mg R 7128 1000 mg R 7227 200 mg With permission from Gane EJ, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50; S 380.

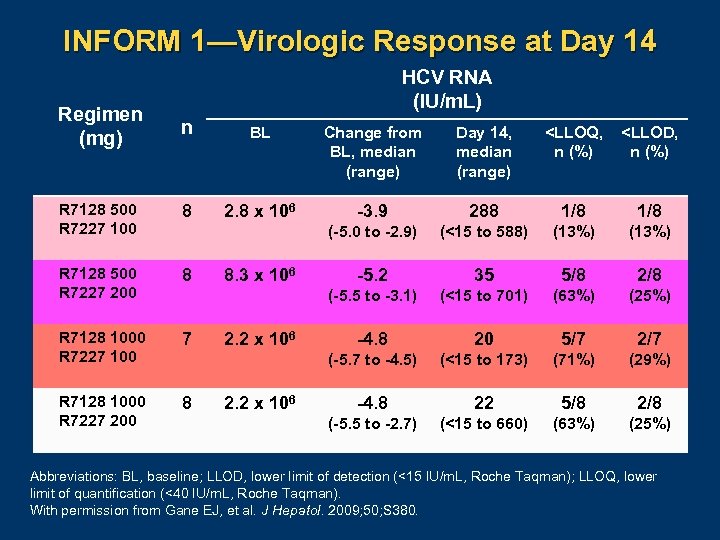

INFORM 1—Virologic Response at Day 14 Regimen (mg) HCV RNA (IU/m. L) n BL Change from BL, median (range) Day 14, median (range) <LLOQ, n (%) <LLOD, n (%) R 7128 500 R 7227 100 8 2. 8 x 106 -3. 9 288 1/8 (-5. 0 to -2. 9) (<15 to 588) (13%) R 7128 500 R 7227 200 8 -5. 2 35 5/8 2/8 (-5. 5 to -3. 1) (<15 to 701) (63%) (25%) R 7128 1000 R 7227 100 7 -4. 8 20 5/7 2/7 (-5. 7 to -4. 5) (<15 to 173) (71%) (29%) R 7128 1000 R 7227 200 8 -4. 8 22 5/8 2/8 (-5. 5 to -2. 7) (<15 to 660) (63%) (25%) 8. 3 x 106 2. 2 x 106 Abbreviations: BL, baseline; LLOD, lower limit of detection (<15 IU/m. L, Roche Taqman); LLOQ, lower limit of quantification (<40 IU/m. L, Roche Taqman). With permission from Gane EJ, et al. J Hepatol. 2009; 50; S 380.

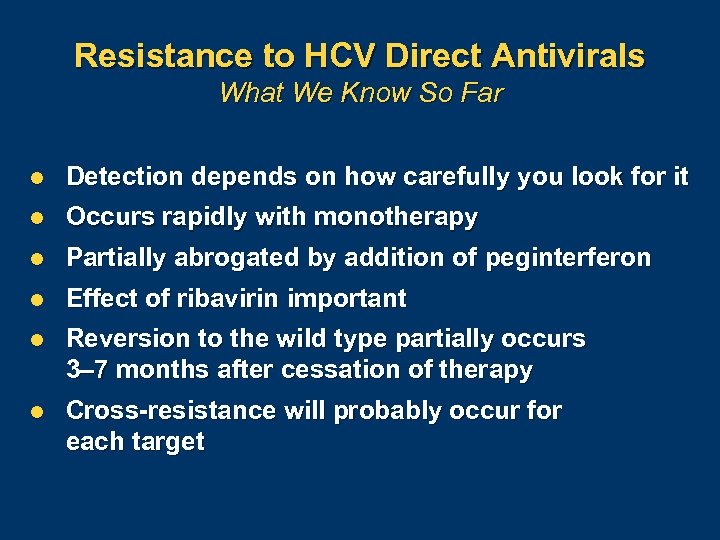

Resistance to HCV Direct Antivirals What We Know So Far l Detection depends on how carefully you look for it l Occurs rapidly with monotherapy l Partially abrogated by addition of peginterferon l Effect of ribavirin important l Reversion to the wild type partially occurs 3– 7 months after cessation of therapy l Cross-resistance will probably occur for each target

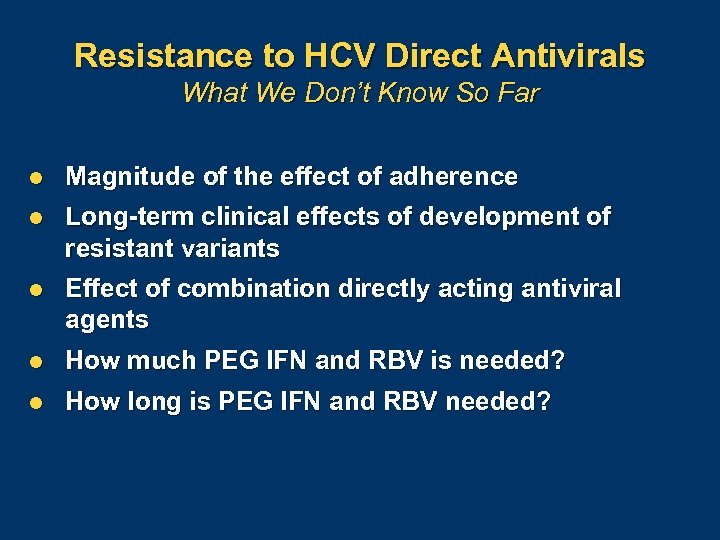

Resistance to HCV Direct Antivirals What We Don’t Know So Far l Magnitude of the effect of adherence l Long-term clinical effects of development of resistant variants l Effect of combination directly acting antiviral agents l How much PEG IFN and RBV is needed? l How long is PEG IFN and RBV needed?

Long-Term Consequences of Resistance “Fitness” Disease progression rates Evolutionary disadvantage Class effects Prevention strategies Retreatment outcomes Graphic courtesy of Dr. John Mc. Hutchison.

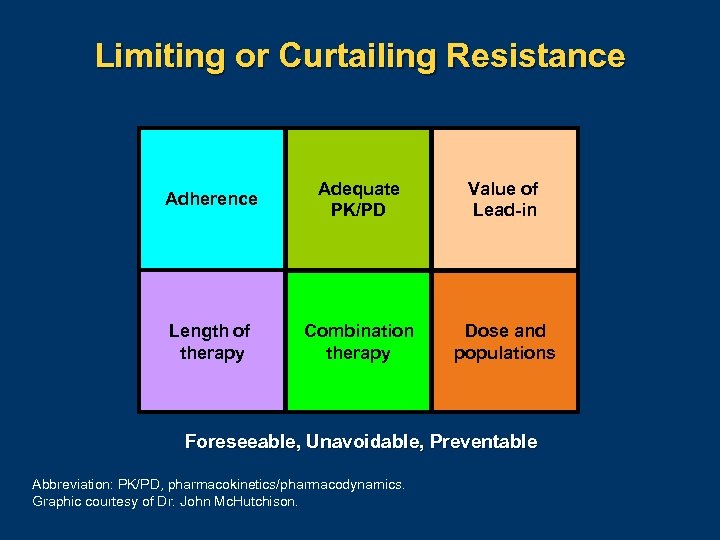

Limiting or Curtailing Resistance Adherence Adequate PK/PD Value of Lead-in Length of therapy Combination therapy Dose and populations Foreseeable, Unavoidable, Preventable Abbreviation: PK/PD, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics. Graphic courtesy of Dr. John Mc. Hutchison.

More Drugs = More Toxicity Cardiotoxicity Rash Liver test abnormalities Anemia Neutropenia Lymphopenia DC rates x 2 -4 fold Abbreviation: DC, discontinuation. Graphic courtesy of Dr. John Mc. Hutchison.

Key Drivers of Successful Therapy Simplicity/ complexity Tolerability Efficacy Cost Duration Resistance Graphic courtesy of Dr. John Mc. Hutchison.

Future Anti-HCV Therapy IFN RBV HCV inhibitor RBV ? IFN? Graphic courtesy of Dr. Nezam Afdhal.

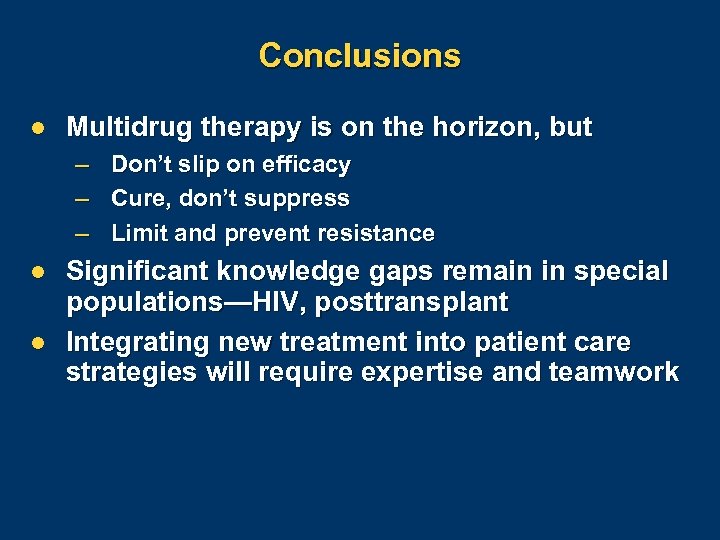

Conclusions l Multidrug therapy is on the horizon, but – – – l l Don’t slip on efficacy Cure, don’t suppress Limit and prevent resistance Significant knowledge gaps remain in special populations—HIV, posttransplant Integrating new treatment into patient care strategies will require expertise and teamwork

Concluding Remarks Ira M. Jacobson, MD Vincent Astor Professor of Medicine Chief, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Medical Director of the Center for the Study of Hepatitis C Weill Cornell Medical College New York, New York

Phases in the Evolution of Anti-HCV Therapy l Less focus on which PEG IFN l Response-guided therapy – principle clear but variable penetrance l Limited choices for nonresponders – huge unmet need l Other populations with unmet needs abound The Empiric Phase The Refinement Phase • Optimal dosing • Viral kinetics • Challenging populations • Nonresponders The Phase of Specifically Targeted Antiviral Therapy for HCV (STAT-C) The Final Phase— Small Molecule Combinations ? ? ? Weisberg IW, et al. Current Hepatitis Reports. 2007; 6: 75 82. Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson.

60 Mb A Polymorphism on Chromosome 19 Predicts SVR 19 q 13. 13 3 kb IL 28 B gene Polymorphism rs 12979860 Chromosome 19 Ge D, et al. Nature. 2009; 461: 399 401. Chromosome 19 graphic courtesy of Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Available at: http: //www. ornl. gov/sci/techresources/meetings/ecr 2/olsen. gif. Accessed on: October 21, 2009.

The IL 28 B Single Nucleotide Polymorphism A Major Discovery Leads to Many New Questions l What insights does this give into the mechanism of IFN responsiveness? – Relationship to upregulation of IFN-specific genes in nonresponders? – Why connected to spontaneous clearance as well? l l Role in clinical practice (assuming availability)? Role as new treatments become available?

Emerging Anti-HCV Therapies Specifically Targeted Antiviral Therapy for HCV (STAT-C) Enzyme Inhibitors Polymerase Protease NS 5 A Genome Sequence-Based RNA interference Other IFN and RBV modifications • Albinterferon, omega IFN, PEG IFN lambda (IL-29) • Taribavirin (viramidine) Immune approaches • Therapeutic vaccines • Toll-like receptor agonists • Hepatitis C immune globulin • Monoclonal antibodies Targeting cellular factors • Cyclophilin antagonists • Nitazoxanide

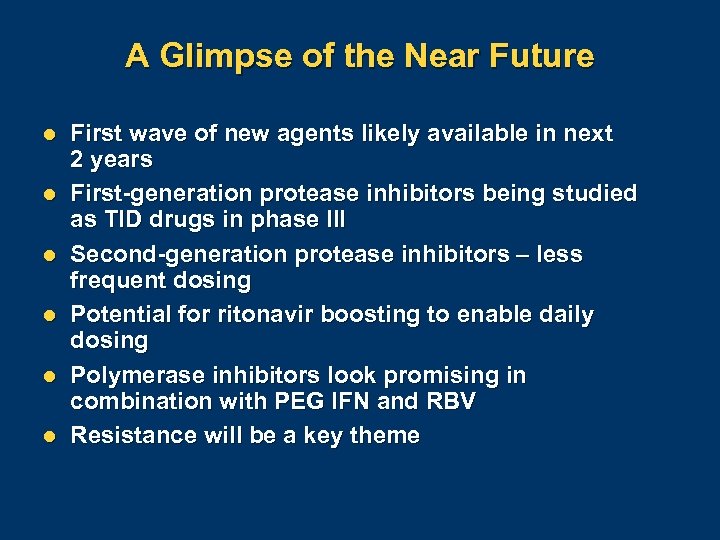

A Glimpse of the Near Future l l l First wave of new agents likely available in next 2 years First-generation protease inhibitors being studied as TID drugs in phase III Second-generation protease inhibitors – less frequent dosing Potential for ritonavir boosting to enable daily dosing Polymerase inhibitors look promising in combination with PEG IFN and RBV Resistance will be a key theme

Anti-HCV Therapy Likely Picture—Near Future Viral enzyme inhibitors + RBV or related drugs ± Immune or host pathway modulators Interferon as a platform for future combinations Need to study different IFNs to determine optimal characteristics Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson.

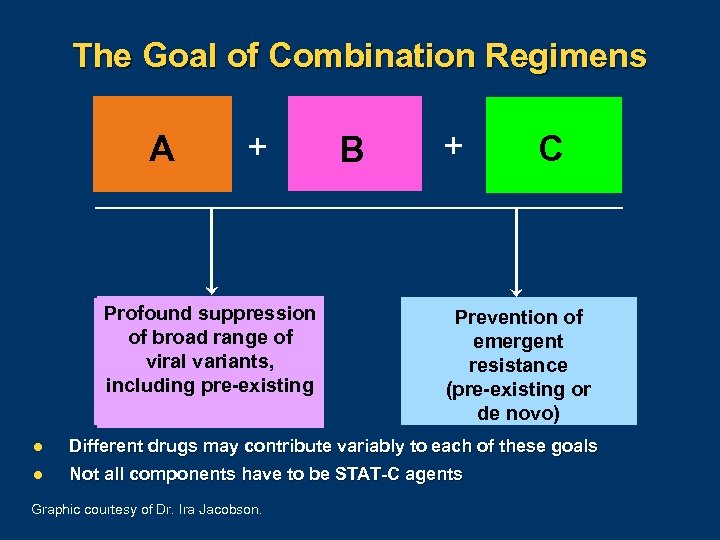

The Goal of Combination Regimens A A + Profound suppression of broad range of viral variants, including pre-existing B + C Prevention of emergent resistance (pre-existing or de novo) l Different drugs may contribute variably to each of these goals l Not all components have to be STAT-C agents Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson.

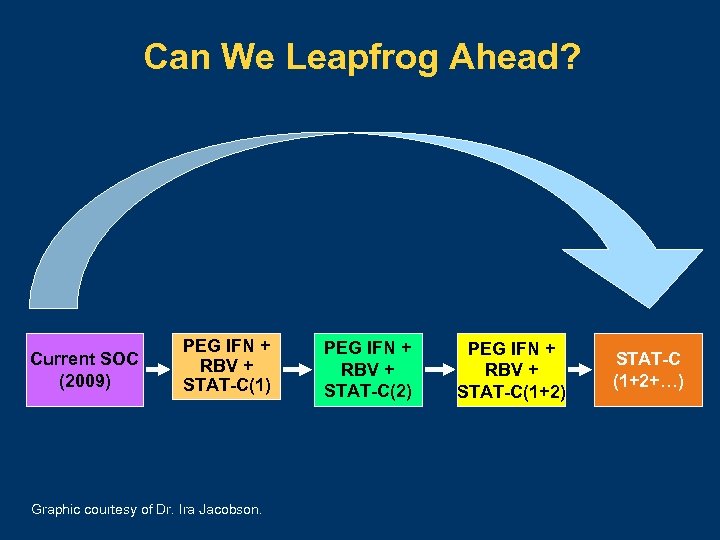

Can We Leapfrog Ahead? Current SOC (2009) PEG IFN + RBV + STAT-C(1) Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ira Jacobson. PEG IFN + RBV + STAT-C(2) PEG IFN + RBV + STAT-C(1+2) STAT-C (1+2+…)

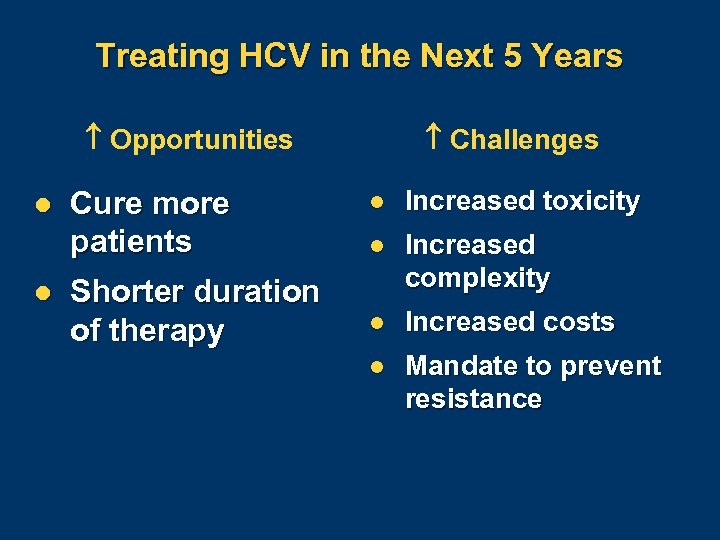

Treating HCV in the Next 5 Years Opportunities l l Cure more patients Shorter duration of therapy Challenges l Increased toxicity l Increased complexity l Increased costs l Mandate to prevent resistance

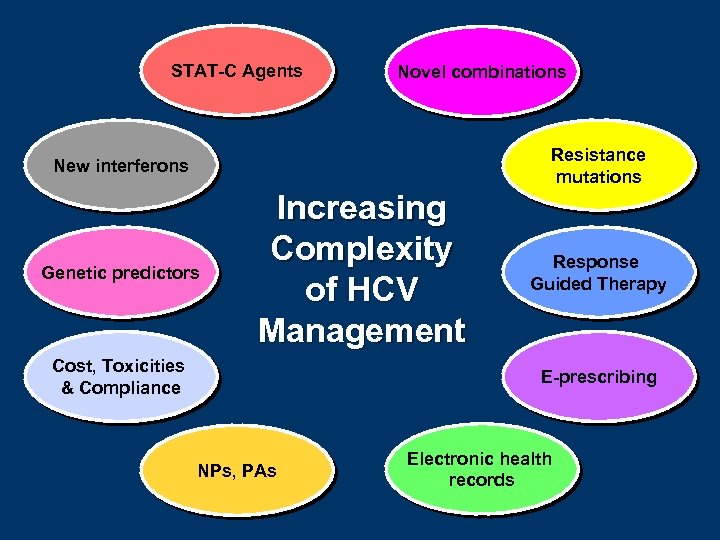

STAT-C Agents Novel combinations Resistance mutations New interferons Genetic predictors Increasing Complexity of HCV Management Cost, Toxicities & Compliance Response Guided Therapy E-prescribing NPs, PAs Electronic health records

f20e469e4ae67f9a7843d62c56b17798.ppt