3a749a1e21e726ff07a665154cf5d6d9.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 32

Introduction Cartels (Draft) Chi Leng, Ph. D. David C. Sharp, Ph. D. Nathan Associates Inc. October 2010

Introduction Cartels (Draft) Chi Leng, Ph. D. David C. Sharp, Ph. D. Nathan Associates Inc. October 2010

General Types of Antitrust Analyses • Economic antitrust analysis can be broken into two broad categories • Exclusion - firms attempt to raise prices by excluding rivals • Exclusive dealing • Tying contracts • Collusion (broadly defined) – firms attempt to raise prices through collaboration with rivals • Horizontal mergers • Price fixing 1

General Types of Antitrust Analyses • Economic antitrust analysis can be broken into two broad categories • Exclusion - firms attempt to raise prices by excluding rivals • Exclusive dealing • Tying contracts • Collusion (broadly defined) – firms attempt to raise prices through collaboration with rivals • Horizontal mergers • Price fixing 1

Price Fixing • Agreements between business rivals to sell (or buy) the same product or service at the same artificially elevated (or depressed) price • Considered by many to be the most central element of competition economics • Regarded with approval even by those generally skeptical of government competition policy* • Price fixing is perhaps the most common form of collusion * Whinston, M. D. (2006). Lectures on Antitrust Economics, p. 15. 2

Price Fixing • Agreements between business rivals to sell (or buy) the same product or service at the same artificially elevated (or depressed) price • Considered by many to be the most central element of competition economics • Regarded with approval even by those generally skeptical of government competition policy* • Price fixing is perhaps the most common form of collusion * Whinston, M. D. (2006). Lectures on Antitrust Economics, p. 15. 2

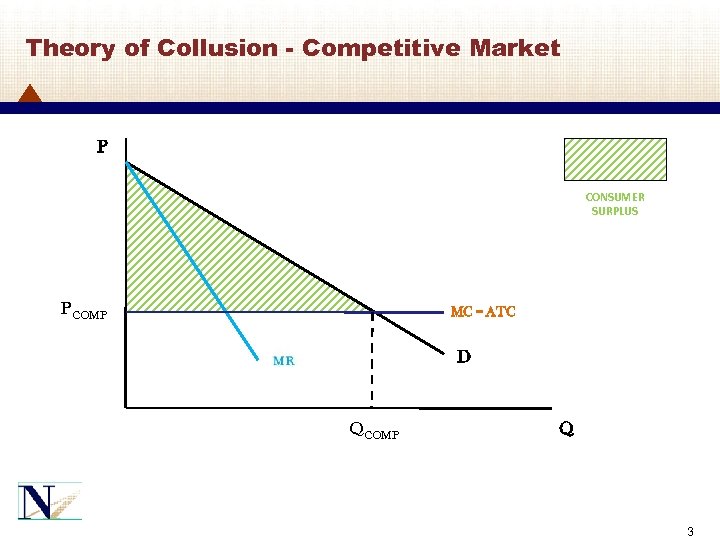

Theory of Collusion - Competitive Market P CONSUMER SURPLUS PCOMP MC = ATC D QCOMP Q 3

Theory of Collusion - Competitive Market P CONSUMER SURPLUS PCOMP MC = ATC D QCOMP Q 3

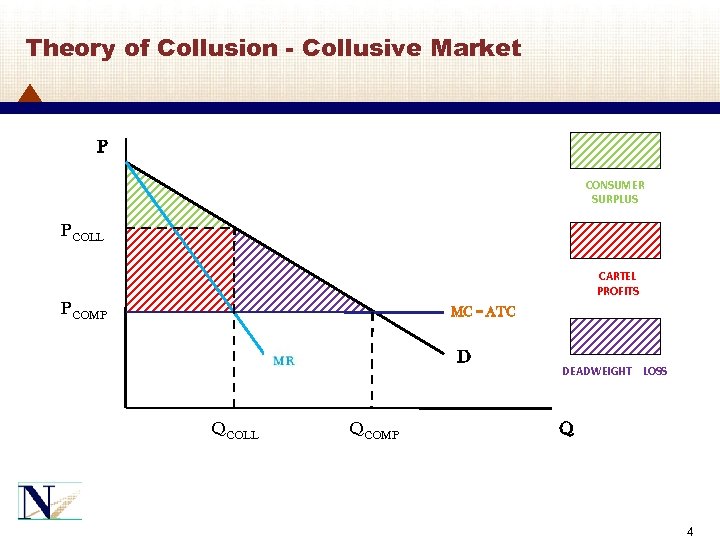

Theory of Collusion - Collusive Market P CONSUMER SURPLUS PCOLL CARTEL PROFITS PCOMP MC = ATC D QCOLL QCOMP DEADWEIGHT LOSS Q 4

Theory of Collusion - Collusive Market P CONSUMER SURPLUS PCOLL CARTEL PROFITS PCOMP MC = ATC D QCOLL QCOMP DEADWEIGHT LOSS Q 4

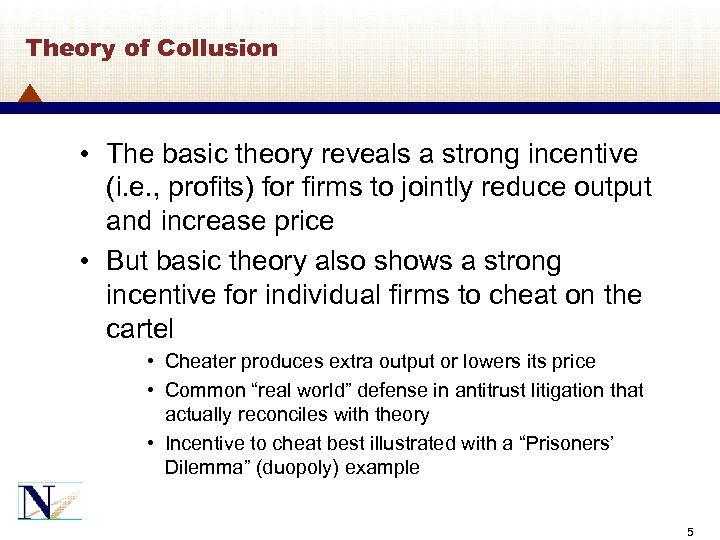

Theory of Collusion • The basic theory reveals a strong incentive (i. e. , profits) for firms to jointly reduce output and increase price • But basic theory also shows a strong incentive for individual firms to cheat on the cartel • Cheater produces extra output or lowers its price • Common “real world” defense in antitrust litigation that actually reconciles with theory • Incentive to cheat best illustrated with a “Prisoners’ Dilemma” (duopoly) example 5

Theory of Collusion • The basic theory reveals a strong incentive (i. e. , profits) for firms to jointly reduce output and increase price • But basic theory also shows a strong incentive for individual firms to cheat on the cartel • Cheater produces extra output or lowers its price • Common “real world” defense in antitrust litigation that actually reconciles with theory • Incentive to cheat best illustrated with a “Prisoners’ Dilemma” (duopoly) example 5

Prisoners Dilemma: Airlines Example • American Airlines and United Airlines* • The two compete for customers on flights between Chicago and Los Angeles * From Perloff, J. M. (2004). Microeconomics, 3 rd Edition, p, 427 6

Prisoners Dilemma: Airlines Example • American Airlines and United Airlines* • The two compete for customers on flights between Chicago and Los Angeles * From Perloff, J. M. (2004). Microeconomics, 3 rd Edition, p, 427 6

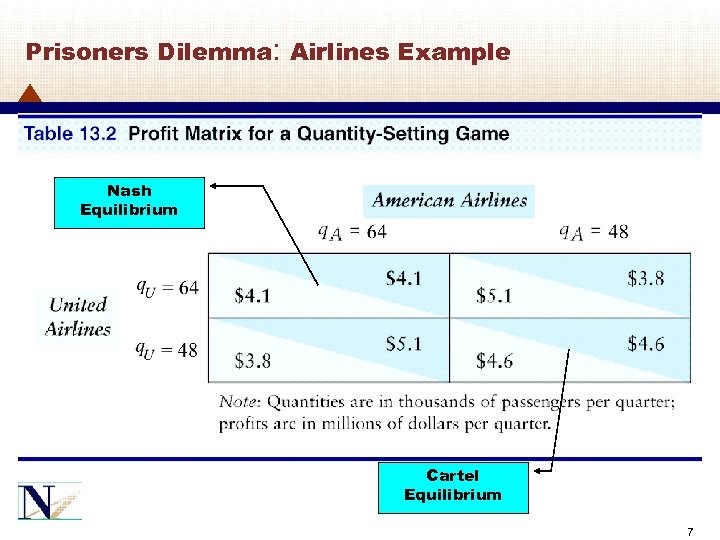

Prisoners Dilemma: Airlines Example Nash Equilibrium Cartel Equilibrium 7

Prisoners Dilemma: Airlines Example Nash Equilibrium Cartel Equilibrium 7

Classic Conditions for Cartel Success • • • Concentrated industry (few firms) High barriers to entry Homogeneous product Inelastic demand No monopsony power (many small buyers) • Mechanism to monitor cartel • Industry organization • Gives pretext for meetings • Detects cheating 8

Classic Conditions for Cartel Success • • • Concentrated industry (few firms) High barriers to entry Homogeneous product Inelastic demand No monopsony power (many small buyers) • Mechanism to monitor cartel • Industry organization • Gives pretext for meetings • Detects cheating 8

Duration of Cartels • Many cartel scholars use duration to measure cartel success, but recognize it is a highly imperfect measure • Results from the literature are mixed, due to different samples (i. e. , types of cartels and time periods) observed • But two relatively recent studies calculate the average duration at 5. 4 years • Gallo, J. C. , Craycraft, J. L. , Dau-Schmidt, K. and Parker, C. A. (2000). Department of Justice Antitrust Enforcement, 1955 -1997: An Empirical Study. Review of Industrial Organization, 17(1). • Levenstein, M. C. and Suslow, V. Y. (2004). International Cartels: Then and Now. Working Paper presented to the NBER Development of the American Economy Summer Institute. 9

Duration of Cartels • Many cartel scholars use duration to measure cartel success, but recognize it is a highly imperfect measure • Results from the literature are mixed, due to different samples (i. e. , types of cartels and time periods) observed • But two relatively recent studies calculate the average duration at 5. 4 years • Gallo, J. C. , Craycraft, J. L. , Dau-Schmidt, K. and Parker, C. A. (2000). Department of Justice Antitrust Enforcement, 1955 -1997: An Empirical Study. Review of Industrial Organization, 17(1). • Levenstein, M. C. and Suslow, V. Y. (2004). International Cartels: Then and Now. Working Paper presented to the NBER Development of the American Economy Summer Institute. 9

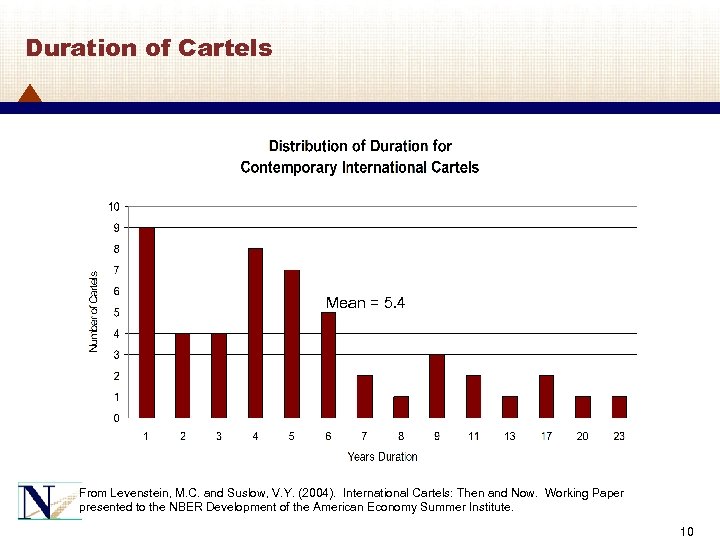

Duration of Cartels Mean = 5. 4 From Levenstein, M. C. and Suslow, V. Y. (2004). International Cartels: Then and Now. Working Paper presented to the NBER Development of the American Economy Summer Institute. 10

Duration of Cartels Mean = 5. 4 From Levenstein, M. C. and Suslow, V. Y. (2004). International Cartels: Then and Now. Working Paper presented to the NBER Development of the American Economy Summer Institute. 10

What Else Does the Literature Say? • Cartels are more likely to form in industries where prices have been falling • Stigler (1964)* argued that cartels are fundamentally unstable: firms agree to restrict output, then engage in secret cheating that erupts in price wars • Modern studies indicate that cartels break up occasionally because of cheating, but biggest challenges are entry and responding to changing economic conditions** * Stigler, G. (1964). A Theory of Oligopoly. Journal of Political Economy, 72(1). ** Levenstein, M. C. and Suslow, V. Y. (2006). What Determines Cartel Success? Journal of Economic Literature, 44. 11

What Else Does the Literature Say? • Cartels are more likely to form in industries where prices have been falling • Stigler (1964)* argued that cartels are fundamentally unstable: firms agree to restrict output, then engage in secret cheating that erupts in price wars • Modern studies indicate that cartels break up occasionally because of cheating, but biggest challenges are entry and responding to changing economic conditions** * Stigler, G. (1964). A Theory of Oligopoly. Journal of Political Economy, 72(1). ** Levenstein, M. C. and Suslow, V. Y. (2006). What Determines Cartel Success? Journal of Economic Literature, 44. 11

How Do We Measure Compensatory Damages? • Damage methodologies compare the prices paid during the period of alleged wrongdoing with the “but for” price • The “but for” price is the price that would have prevailed in the absence of (i. e. , but for) the cartel • Two general approaches • Utilizing benchmarks • Econometrics 12

How Do We Measure Compensatory Damages? • Damage methodologies compare the prices paid during the period of alleged wrongdoing with the “but for” price • The “but for” price is the price that would have prevailed in the absence of (i. e. , but for) the cartel • Two general approaches • Utilizing benchmarks • Econometrics 12

Benchmarks • “Before-during-after” approach • Examine product price before, during, and after cartel period; difference between the cartel price and the competitive price measures the damage • May meet objection that changes in factors other than the cartel may have produced price changes during cartel period • “Yardstick” approach • Examine price movements of a comparable product, unaffected by the cartel, and compare to price of the cartelized product to determine damages • Variant examines production costs, and “cost plus” pricing determines what the price would have been absent the cartel • “Geographic area” approach • Examine product price from a region or part of the world where the cartel did not occur. Prices in the affected and unaffected areas are compared to estimate damages 13

Benchmarks • “Before-during-after” approach • Examine product price before, during, and after cartel period; difference between the cartel price and the competitive price measures the damage • May meet objection that changes in factors other than the cartel may have produced price changes during cartel period • “Yardstick” approach • Examine price movements of a comparable product, unaffected by the cartel, and compare to price of the cartelized product to determine damages • Variant examines production costs, and “cost plus” pricing determines what the price would have been absent the cartel • “Geographic area” approach • Examine product price from a region or part of the world where the cartel did not occur. Prices in the affected and unaffected areas are compared to estimate damages 13

Benchmarks • Benchmarks may be fine (or necessary due to data constraints) in some cases • But they may fail to account for other systematic factors (other than the cartel) that may have influenced price during the cartel period • We need an approach that allows us to account for all relevant factors 14

Benchmarks • Benchmarks may be fine (or necessary due to data constraints) in some cases • But they may fail to account for other systematic factors (other than the cartel) that may have influenced price during the cartel period • We need an approach that allows us to account for all relevant factors 14

Econometrics (Multiple Regression) • Econometrics is the application of statistical methods to economic data • The basic idea underlying econometrics is to build a model that accurately describes the “real world, ” in equation form • It is a technique that allows us to account for any factor (variable) thought to be potentially relevant, and have its actual influence examined 15

Econometrics (Multiple Regression) • Econometrics is the application of statistical methods to economic data • The basic idea underlying econometrics is to build a model that accurately describes the “real world, ” in equation form • It is a technique that allows us to account for any factor (variable) thought to be potentially relevant, and have its actual influence examined 15

Econometrics (Multiple Regression) • Each variable’s impact is disentangled from all others, allowing us to measure the isolated influence of each • In price-fixing, the allegation is that cartel members conspired to impact the price • With econometrics, we can measure the cartel’s impact on price, alone, net of all other influences 16

Econometrics (Multiple Regression) • Each variable’s impact is disentangled from all others, allowing us to measure the isolated influence of each • In price-fixing, the allegation is that cartel members conspired to impact the price • With econometrics, we can measure the cartel’s impact on price, alone, net of all other influences 16

Case Study: Graphite Products* • Graphite is an intermediate product used in diverse downstream industries • • • Chemicals Glass Aerospace Metallurgy Semiconductors * While there were allegations of price fixing in various graphite product markets, the discussion below is entirely hypothetical for the purposes of this case study. 17

Case Study: Graphite Products* • Graphite is an intermediate product used in diverse downstream industries • • • Chemicals Glass Aerospace Metallurgy Semiconductors * While there were allegations of price fixing in various graphite product markets, the discussion below is entirely hypothetical for the purposes of this case study. 17

Case Study: Graphite Products* • Three U. S. suppliers of graphite products: • Company A • Company B • Company C • Each company had 25% of the market • Imports from China, India and other countries represented the other 25% * While there were allegations of price fixing in various graphite product markets, the discussion below is entirely hypothetical for the purposes of this case study. 18

Case Study: Graphite Products* • Three U. S. suppliers of graphite products: • Company A • Company B • Company C • Each company had 25% of the market • Imports from China, India and other countries represented the other 25% * While there were allegations of price fixing in various graphite product markets, the discussion below is entirely hypothetical for the purposes of this case study. 18

Case Study: Graphite Products* • Inputs to graphite production • • Petroleum coke Natural gas Electricity Labor * While there were allegations of price fixing in various graphite product markets, the discussion below is entirely hypothetical for the purposes of this case study. 19

Case Study: Graphite Products* • Inputs to graphite production • • Petroleum coke Natural gas Electricity Labor * While there were allegations of price fixing in various graphite product markets, the discussion below is entirely hypothetical for the purposes of this case study. 19

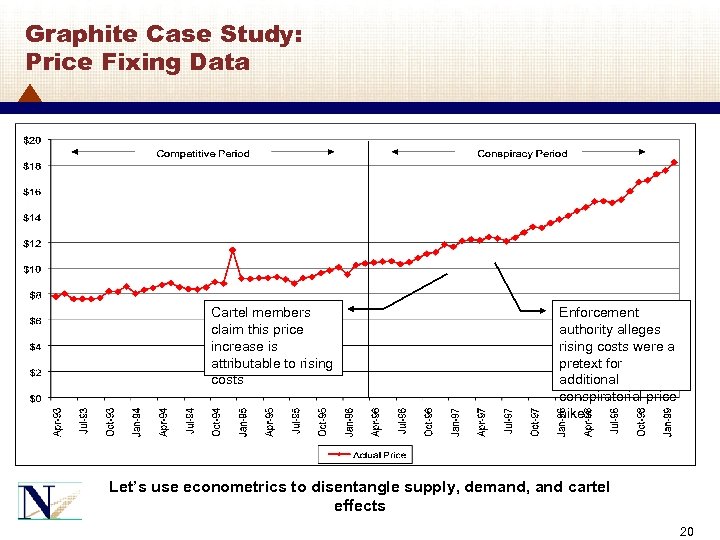

Graphite Case Study: Price Fixing Data Cartel members claim this price increase is attributable to rising costs Enforcement authority alleges rising costs were a pretext for additional conspiratorial price hikes Let’s use econometrics to disentangle supply, demand, and cartel effects 20

Graphite Case Study: Price Fixing Data Cartel members claim this price increase is attributable to rising costs Enforcement authority alleges rising costs were a pretext for additional conspiratorial price hikes Let’s use econometrics to disentangle supply, demand, and cartel effects 20

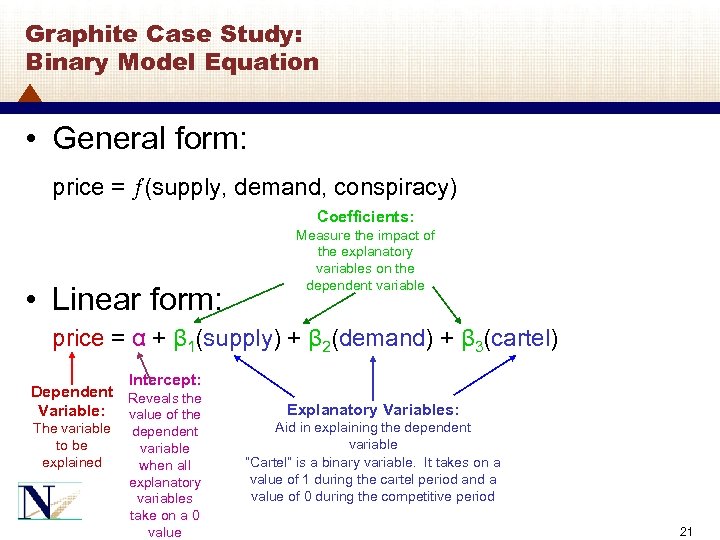

Graphite Case Study: Binary Model Equation • General form: price = (supply, demand, conspiracy) Coefficients: • Linear form: Measure the impact of the explanatory variables on the dependent variable price = α + β 1(supply) + β 2(demand) + β 3(cartel) Intercept: Dependent Reveals the Variable: value of the The variable to be explained dependent variable when all explanatory variables take on a 0 value Explanatory Variables: Aid in explaining the dependent variable “Cartel” is a binary variable. It takes on a value of 1 during the cartel period and a value of 0 during the competitive period 21

Graphite Case Study: Binary Model Equation • General form: price = (supply, demand, conspiracy) Coefficients: • Linear form: Measure the impact of the explanatory variables on the dependent variable price = α + β 1(supply) + β 2(demand) + β 3(cartel) Intercept: Dependent Reveals the Variable: value of the The variable to be explained dependent variable when all explanatory variables take on a 0 value Explanatory Variables: Aid in explaining the dependent variable “Cartel” is a binary variable. It takes on a value of 1 during the cartel period and a value of 0 during the competitive period 21

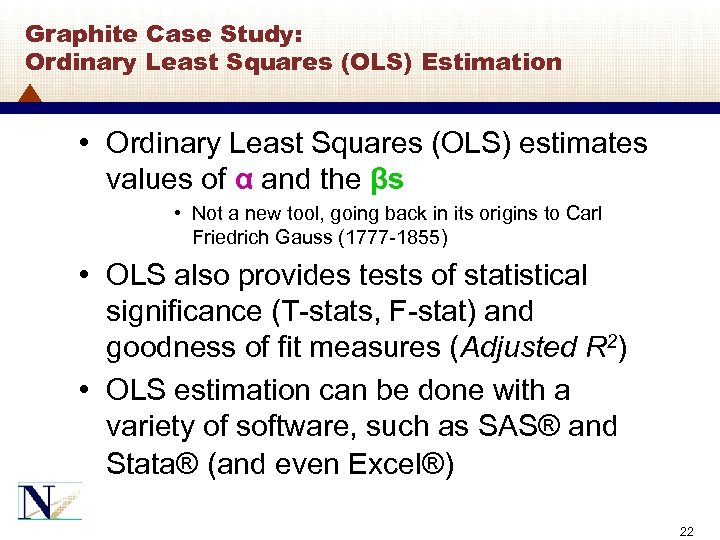

Graphite Case Study: Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Estimation • Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimates values of α and the βs • Not a new tool, going back in its origins to Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777 -1855) • OLS also provides tests of statistical significance (T-stats, F-stat) and goodness of fit measures (Adjusted R 2) • OLS estimation can be done with a variety of software, such as SAS® and Stata® (and even Excel®) 22

Graphite Case Study: Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Estimation • Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimates values of α and the βs • Not a new tool, going back in its origins to Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777 -1855) • OLS also provides tests of statistical significance (T-stats, F-stat) and goodness of fit measures (Adjusted R 2) • OLS estimation can be done with a variety of software, such as SAS® and Stata® (and even Excel®) 22

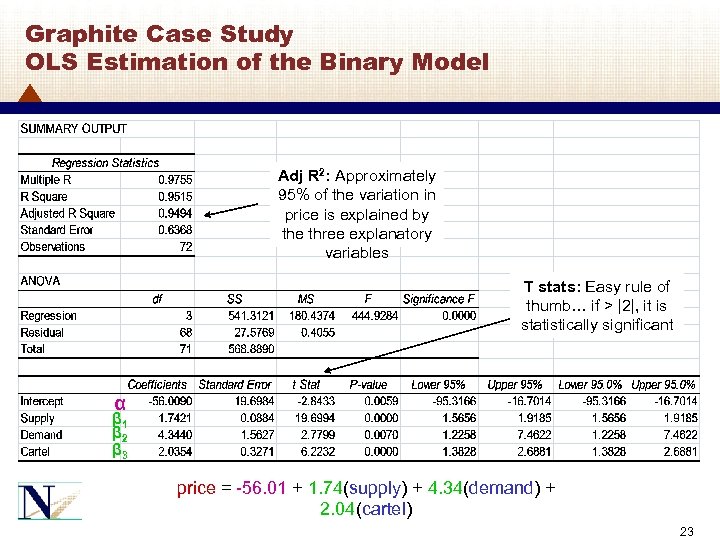

Graphite Case Study OLS Estimation of the Binary Model Adj R 2: Approximately 95% of the variation in price is explained by the three explanatory variables T stats: Easy rule of thumb… if > |2|, it is statistically significant α β 1 β 2 β 3 price = -56. 01 + 1. 74(supply) + 4. 34(demand) + 2. 04(cartel) 23

Graphite Case Study OLS Estimation of the Binary Model Adj R 2: Approximately 95% of the variation in price is explained by the three explanatory variables T stats: Easy rule of thumb… if > |2|, it is statistically significant α β 1 β 2 β 3 price = -56. 01 + 1. 74(supply) + 4. 34(demand) + 2. 04(cartel) 23

Graphite Case Study OLS Predictions & Inference with the Binary Model • Let’s see how well it predicts prices for, say, April 1993 (i. e. , the beginning) • In April 1993, supply (costs) = $5. 53, demand (index) = 12. 51, & cartel= 0 price = -56. 01 + 1. 74(supply) + 4. 34(demand) + 2. 04(cartel) price = -56. 01 + 1. 74(5. 53) + 4. 34(12. 51) + 2. 04(0) price = -56. 01 + 9. 62 + 54. 29 price = $7. 90 • Actual April 1993 price = $7. 94 • Error = predicted – actual = -$0. 04 • Direct interpretation of the cartel’s impact, in isolation • Average overcharge during the cartel period = $2. 04 per unit • Damages = the quantity sold (Q) multiplied by the average overcharge 24

Graphite Case Study OLS Predictions & Inference with the Binary Model • Let’s see how well it predicts prices for, say, April 1993 (i. e. , the beginning) • In April 1993, supply (costs) = $5. 53, demand (index) = 12. 51, & cartel= 0 price = -56. 01 + 1. 74(supply) + 4. 34(demand) + 2. 04(cartel) price = -56. 01 + 1. 74(5. 53) + 4. 34(12. 51) + 2. 04(0) price = -56. 01 + 9. 62 + 54. 29 price = $7. 90 • Actual April 1993 price = $7. 94 • Error = predicted – actual = -$0. 04 • Direct interpretation of the cartel’s impact, in isolation • Average overcharge during the cartel period = $2. 04 per unit • Damages = the quantity sold (Q) multiplied by the average overcharge 24

A Variant: Forecast Model • With the forecast method we estimate the coefficients using data during the competitive period only; there is no cartel binary variable • Use the estimated coefficients above with values for the explanatory variables during the cartel period to predict what prices would have been, but for the cartel 25

A Variant: Forecast Model • With the forecast method we estimate the coefficients using data during the competitive period only; there is no cartel binary variable • Use the estimated coefficients above with values for the explanatory variables during the cartel period to predict what prices would have been, but for the cartel 25

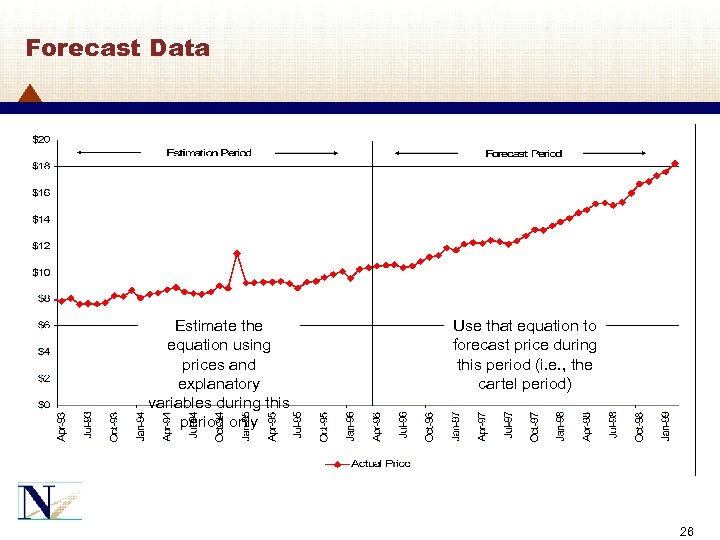

Forecast Data Estimate the equation using prices and explanatory variables during this period only Use that equation to forecast price during this period (i. e. , the cartel period) 26

Forecast Data Estimate the equation using prices and explanatory variables during this period only Use that equation to forecast price during this period (i. e. , the cartel period) 26

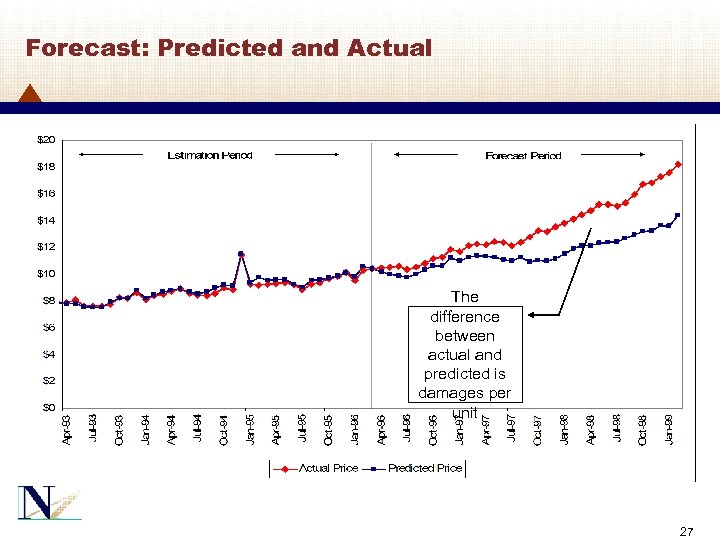

Forecast: Predicted and Actual The difference between actual and predicted is damages per unit 27

Forecast: Predicted and Actual The difference between actual and predicted is damages per unit 27

Binary Model • Advantage: • Direct estimation of the average overcharge across the cartel period • Disadvantage: • No pretty picture; it does not provide a clear graphical comparison of the actual and “but for” price 28

Binary Model • Advantage: • Direct estimation of the average overcharge across the cartel period • Disadvantage: • No pretty picture; it does not provide a clear graphical comparison of the actual and “but for” price 28

Forecast Model • Advantage: • Provides a clear graphical comparison of the actual and “but for” price • Disadvantages: • Damages calculated month-by-month (no big deal, really) • Literature suggests that forecast models tend to produce large confidence intervals* * Rubinfeld, D. L. (1985). Econometrics in the Courtroom. Columbia Law Review, 85(5), pp. 1048 -1097. 29

Forecast Model • Advantage: • Provides a clear graphical comparison of the actual and “but for” price • Disadvantages: • Damages calculated month-by-month (no big deal, really) • Literature suggests that forecast models tend to produce large confidence intervals* * Rubinfeld, D. L. (1985). Econometrics in the Courtroom. Columbia Law Review, 85(5), pp. 1048 -1097. 29

Conclusion • Economic analysis is an integral part of competition enforcement • Econometric analysis has also become prevalent, particularly in price-fixing cases 30

Conclusion • Economic analysis is an integral part of competition enforcement • Econometric analysis has also become prevalent, particularly in price-fixing cases 30

Conclusion Cartels (Draft) Chi Leng, Ph. D. David C. Sharp, Ph. D. Nathan Associates Inc. October 2010

Conclusion Cartels (Draft) Chi Leng, Ph. D. David C. Sharp, Ph. D. Nathan Associates Inc. October 2010