9c25d7bd650c4e14a9e5a2b65e532d95.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 48

International Meaning Conference July, 2016, Toronto Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Cancer Patients William Breitbart, M. D. , Chairman Jimmie C Holland, Chair in Psychiatric Oncology Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center New York, USA www. mskcc. org

International Meaning Conference July, 2016, Toronto Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Cancer Patients William Breitbart, M. D. , Chairman Jimmie C Holland, Chair in Psychiatric Oncology Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center New York, USA www. mskcc. org

Palliative Care: Beyond Symptom Control • Concepts of adequate palliative care must be expanded in their focus beyond pain and physical symptom control to include psychiatric, psychosocial, existential and spiritual domains of care.

Palliative Care: Beyond Symptom Control • Concepts of adequate palliative care must be expanded in their focus beyond pain and physical symptom control to include psychiatric, psychosocial, existential and spiritual domains of care.

Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine Second Edition Edited by Harvey Max Chochinov & William Breitbart M. D. Email: Breitbaw@mskcc. org 4 Easy Ways to Order Promo Code: 27977 • Phone: (800) 451. 7556 • Fax: 919. 677. 1303 • Web: www. oup. com/us • Mail: Oxford University Press. Order Dept. 2001 Evans Road, Cary, NC, 2751

Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine Second Edition Edited by Harvey Max Chochinov & William Breitbart M. D. Email: Breitbaw@mskcc. org 4 Easy Ways to Order Promo Code: 27977 • Phone: (800) 451. 7556 • Fax: 919. 677. 1303 • Web: www. oup. com/us • Mail: Oxford University Press. Order Dept. 2001 Evans Road, Cary, NC, 2751

From Oxford University Press & IPOS Press For the International Psycho-Oncology Society Available at: global. oup. com/ April 2014 • 192 pp. • Paperback 9780199917402 • $39. 95 Save 20% with promo code 32629 For information please visit: www. ipos-society. org Contact Information for Dr. William Breitbart. M. D Chairman Jimmie C Holland Chair in Psychiatric Oncology Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Email: breitbaw@mskcc. org

From Oxford University Press & IPOS Press For the International Psycho-Oncology Society Available at: global. oup. com/ April 2014 • 192 pp. • Paperback 9780199917402 • $39. 95 Save 20% with promo code 32629 For information please visit: www. ipos-society. org Contact Information for Dr. William Breitbart. M. D Chairman Jimmie C Holland Chair in Psychiatric Oncology Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Email: breitbaw@mskcc. org

William Breitbart, M. D. Editor-in-Chief Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center New York, NY Email: Breitbaw@mskcc. org To Submit Articles: Cambridge University Press http : //mc. manuscriptcentral. com/pax For Information: email: palliative@mskcc. org

William Breitbart, M. D. Editor-in-Chief Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center New York, NY Email: Breitbaw@mskcc. org To Submit Articles: Cambridge University Press http : //mc. manuscriptcentral. com/pax For Information: email: palliative@mskcc. org

The Concept of Despair at the End of Life • Desire for hastened death • Suicidal ideation • Loss of meaning/spiritual well-being • Hopelessness • Loss of Dignity • Demoralization • Depression/Anxiety/Panic

The Concept of Despair at the End of Life • Desire for hastened death • Suicidal ideation • Loss of meaning/spiritual well-being • Hopelessness • Loss of Dignity • Demoralization • Depression/Anxiety/Panic

The Unique Nature of Human Existence • Human Beings are Uniquely Aware of our Existence (awe-dread paradox, finiteness, responsibility, guilt , culture) • Meaning – Making is the Defining Characteristic of Human Beings as a Species • Connection / Connectedness is Essential to Human Survival , and the Essence of the Human Experience (to each other, past , present, future, something greater) • The Capacity for Transformation is Unique to Human Beings (growth, benefit finding, attitude towards suffering)

The Unique Nature of Human Existence • Human Beings are Uniquely Aware of our Existence (awe-dread paradox, finiteness, responsibility, guilt , culture) • Meaning – Making is the Defining Characteristic of Human Beings as a Species • Connection / Connectedness is Essential to Human Survival , and the Essence of the Human Experience (to each other, past , present, future, something greater) • The Capacity for Transformation is Unique to Human Beings (growth, benefit finding, attitude towards suffering)

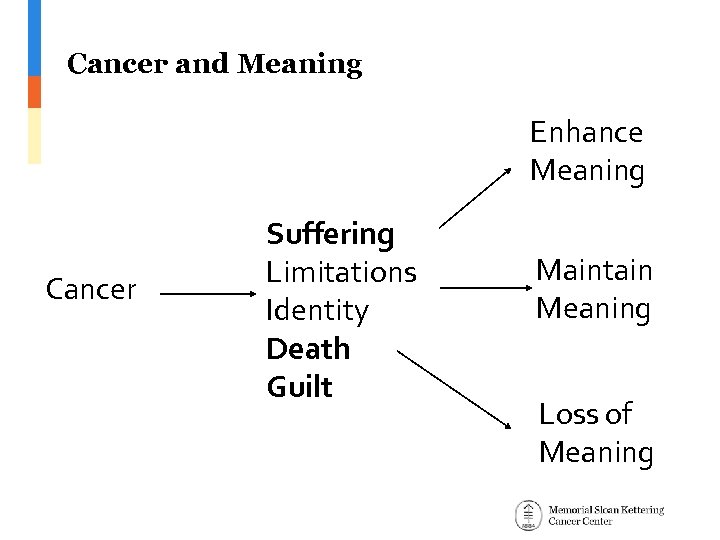

Cancer and Meaning Enhance Meaning Cancer Suffering Limitations Identity Death Guilt Maintain Meaning Loss of Meaning

Cancer and Meaning Enhance Meaning Cancer Suffering Limitations Identity Death Guilt Maintain Meaning Loss of Meaning

Spirituality • A construct involving concepts of: – FAITH – MEANING

Spirituality • A construct involving concepts of: – FAITH – MEANING

Faith • A belief in a higher transcendent power, not necessarily identified as God and not necessarily through participation in the rituals or beliefs of a specific organized religion • Faith in a transcendent power may identify this power as being external to the human psyche or internalized

Faith • A belief in a higher transcendent power, not necessarily identified as God and not necessarily through participation in the rituals or beliefs of a specific organized religion • Faith in a transcendent power may identify this power as being external to the human psyche or internalized

Meaning • Having a sense that one’s life has meaning involves the conviction that one is fulfilling a unique role and purpose in a life that is a gift. A life that comes with a responsibility to live to one’s full potential as a human being. In so doing, being able to achieve a sense of peace, contentment or even transcendence through connectedness with something greater than one’s self

Meaning • Having a sense that one’s life has meaning involves the conviction that one is fulfilling a unique role and purpose in a life that is a gift. A life that comes with a responsibility to live to one’s full potential as a human being. In so doing, being able to achieve a sense of peace, contentment or even transcendence through connectedness with something greater than one’s self

Meaning • Meaning is the experience of feeling fully alive, of being in love with Being • Meaning is the experience of Being, Becoming, & Having Been • The experience of Connection and Transcendence( Care; Time; Attitude): Connectedness, Love, Care & Indebtedness, to one’s life, one’s self , one’s loved ones, to the past present and future. Connection to the authentic self ( the “who” not the” what” I am), to others, to the transcendent, to meaningful moments • The experience of Love, Beauty, Joy, and Life in all its duality • Meaning is the experience of Freedom- being free to be our true selves

Meaning • Meaning is the experience of feeling fully alive, of being in love with Being • Meaning is the experience of Being, Becoming, & Having Been • The experience of Connection and Transcendence( Care; Time; Attitude): Connectedness, Love, Care & Indebtedness, to one’s life, one’s self , one’s loved ones, to the past present and future. Connection to the authentic self ( the “who” not the” what” I am), to others, to the transcendent, to meaningful moments • The experience of Love, Beauty, Joy, and Life in all its duality • Meaning is the experience of Freedom- being free to be our true selves

The Importance of Meaning and Spiritual Needs in Cancer Patients In a sample of 248 cancer patients the following rates of endorsement were found for questions regarding needs: • Overcoming fears - 51% • Finding hope - 42% • Finding meaning in life - 40% • Finding peace of mind - 43% • Finding spiritual resources - 39% Higher rate of spiritual/existential needs in ethnic minorities, unmarried patients, more recent diagnosis Moadel A et al. Psychooncology 1999, 8: 378 -385

The Importance of Meaning and Spiritual Needs in Cancer Patients In a sample of 248 cancer patients the following rates of endorsement were found for questions regarding needs: • Overcoming fears - 51% • Finding hope - 42% • Finding meaning in life - 40% • Finding peace of mind - 43% • Finding spiritual resources - 39% Higher rate of spiritual/existential needs in ethnic minorities, unmarried patients, more recent diagnosis Moadel A et al. Psychooncology 1999, 8: 378 -385

The Universality of Existential Suffering In a sample of 162 Japanese cancer inpatients, existential distress was related to: • Dependency - 39 % • Meaninglessness - 37 % • Hopelessness - 37 % • Burden to others - 34 % • Loss of social role - 29 % • Feeling irrelevant - 28 % Morita T, et al, psycho-oncology, 9: 164 -168, 2000.

The Universality of Existential Suffering In a sample of 162 Japanese cancer inpatients, existential distress was related to: • Dependency - 39 % • Meaninglessness - 37 % • Hopelessness - 37 % • Burden to others - 34 % • Loss of social role - 29 % • Feeling irrelevant - 28 % Morita T, et al, psycho-oncology, 9: 164 -168, 2000.

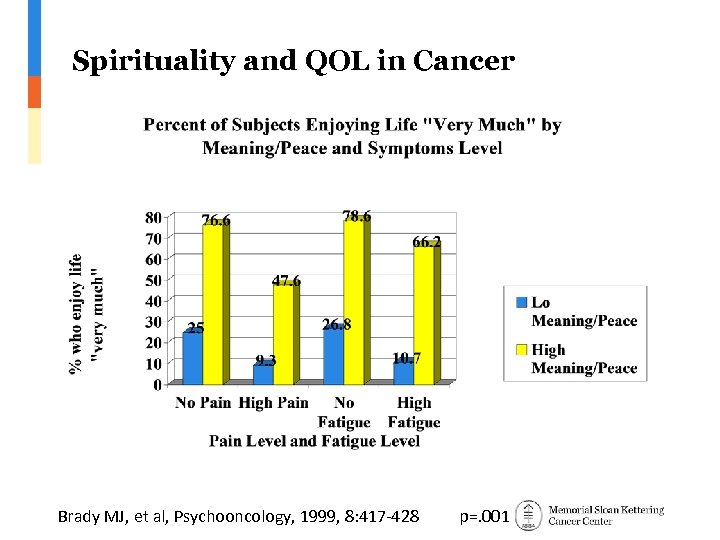

Spirituality and QOL in Cancer Brady MJ, et al, Psychooncology, 1999, 8: 417 -428 p=. 001

Spirituality and QOL in Cancer Brady MJ, et al, Psychooncology, 1999, 8: 417 -428 p=. 001

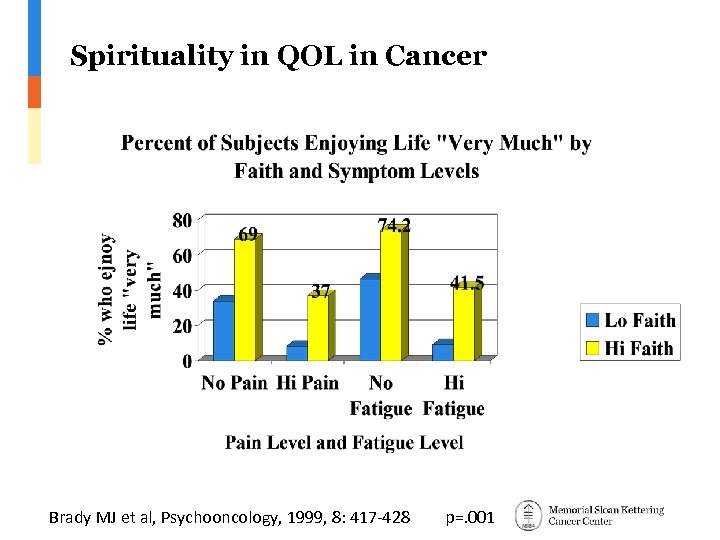

Spirituality in QOL in Cancer Brady MJ et al, Psychooncology, 1999, 8: 417 -428 p=. 001

Spirituality in QOL in Cancer Brady MJ et al, Psychooncology, 1999, 8: 417 -428 p=. 001

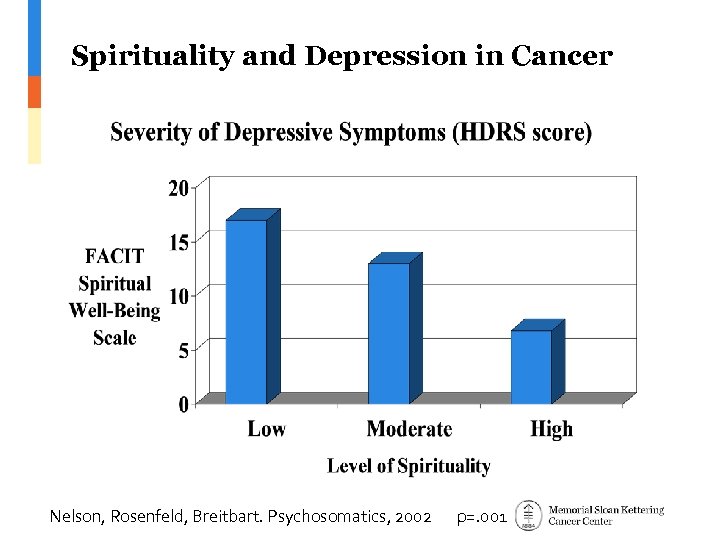

Spirituality and Depression in Cancer Nelson, Rosenfeld, Breitbart. Psychosomatics, 2002 p=. 001

Spirituality and Depression in Cancer Nelson, Rosenfeld, Breitbart. Psychosomatics, 2002 p=. 001

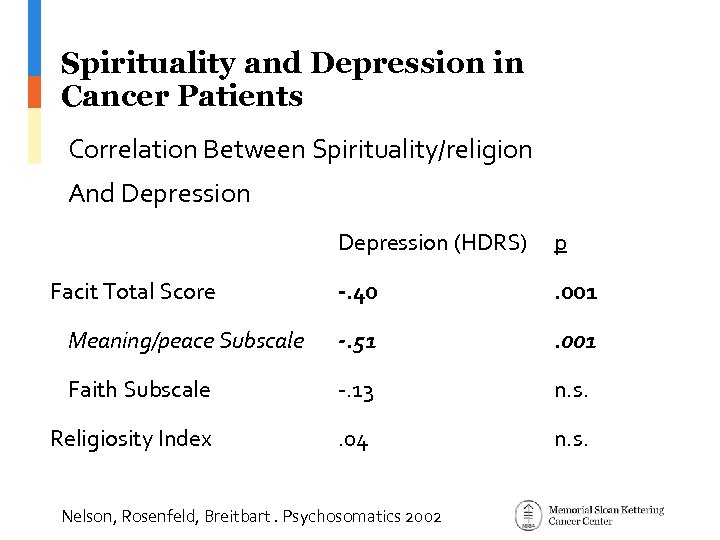

Spirituality and Depression in Cancer Patients Correlation Between Spirituality/religion And Depression (HDRS) p -. 40 . 001 Meaning/peace Subscale -. 51 . 001 Faith Subscale -. 13 n. s. Religiosity Index . 04 n. s. Facit Total Score Nelson, Rosenfeld, Breitbart. Psychosomatics 2002

Spirituality and Depression in Cancer Patients Correlation Between Spirituality/religion And Depression (HDRS) p -. 40 . 001 Meaning/peace Subscale -. 51 . 001 Faith Subscale -. 13 n. s. Religiosity Index . 04 n. s. Facit Total Score Nelson, Rosenfeld, Breitbart. Psychosomatics 2002

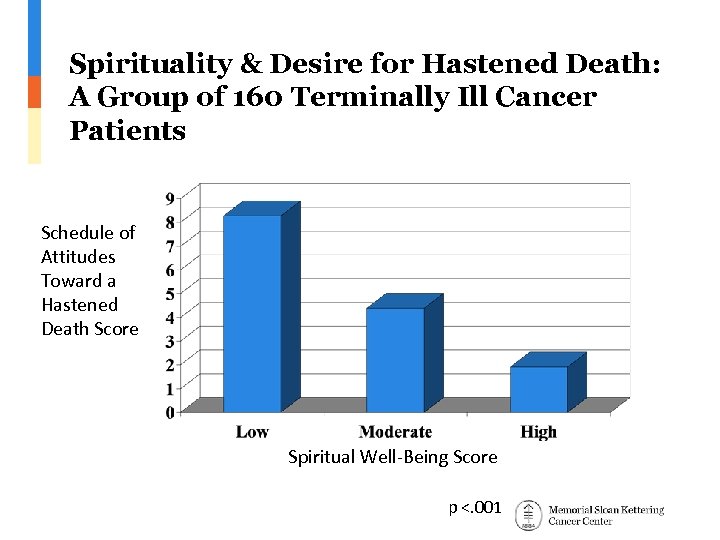

Spirituality & Desire for Hastened Death: A Group of 160 Terminally Ill Cancer Patients Schedule of Attitudes Toward a Hastened Death Score Spiritual Well-Being Score p <. 001

Spirituality & Desire for Hastened Death: A Group of 160 Terminally Ill Cancer Patients Schedule of Attitudes Toward a Hastened Death Score Spiritual Well-Being Score p <. 001

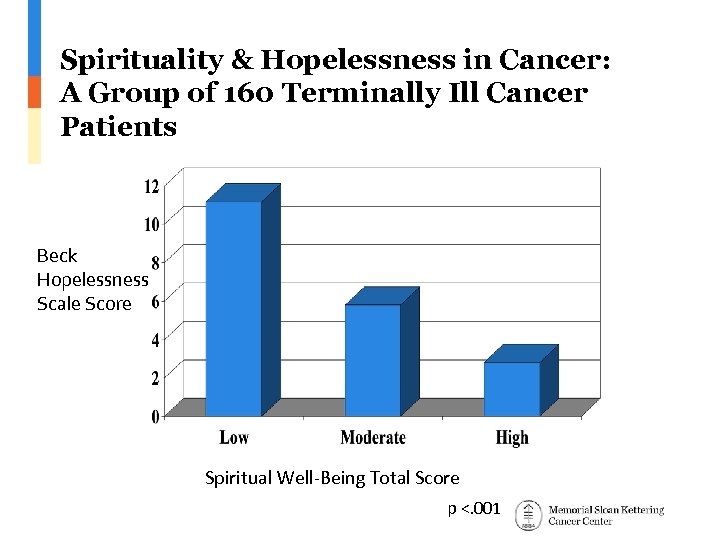

Spirituality & Hopelessness in Cancer: A Group of 160 Terminally Ill Cancer Patients Beck Hopelessness Scale Score Spiritual Well-Being Total Score p <. 001

Spirituality & Hopelessness in Cancer: A Group of 160 Terminally Ill Cancer Patients Beck Hopelessness Scale Score Spiritual Well-Being Total Score p <. 001

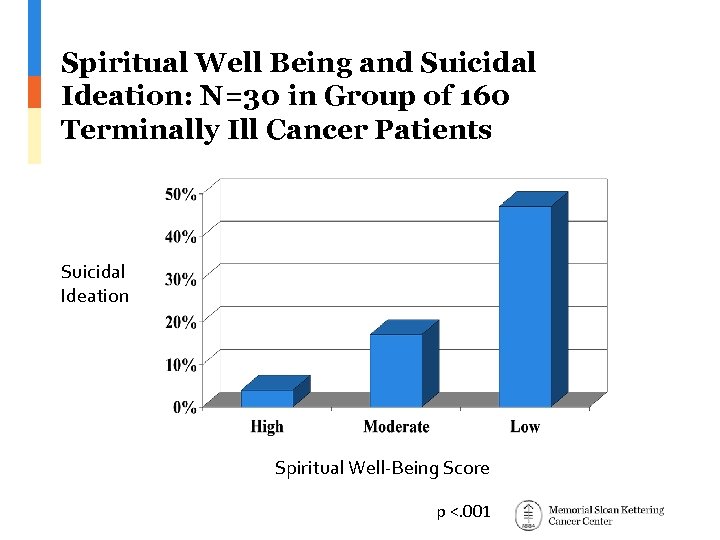

Spiritual Well Being and Suicidal Ideation: N=30 in Group of 160 Terminally Ill Cancer Patients Suicidal Ideation Spiritual Well-Being Score p <. 001

Spiritual Well Being and Suicidal Ideation: N=30 in Group of 160 Terminally Ill Cancer Patients Suicidal Ideation Spiritual Well-Being Score p <. 001

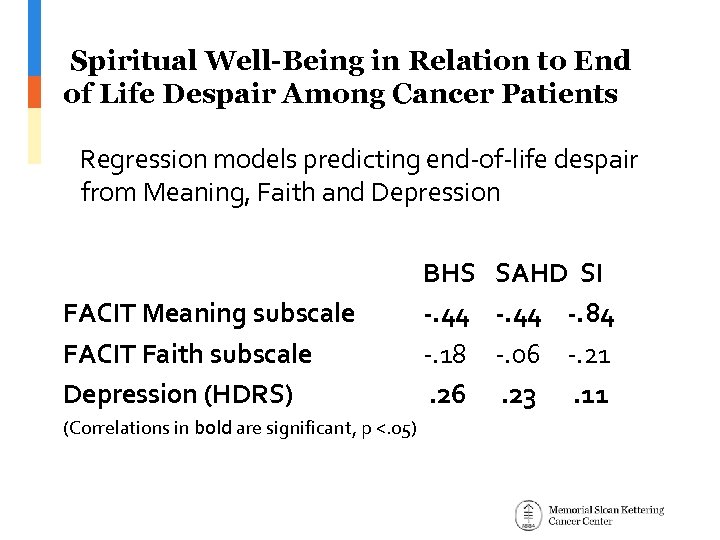

Spiritual Well-Being in Relation to End of Life Despair Among Cancer Patients Regression models predicting end-of-life despair from Meaning, Faith and Depression FACIT Meaning subscale FACIT Faith subscale Depression (HDRS) (Correlations in bold are significant, p <. 05) BHS -. 44 -. 18. 26 SAHD SI -. 44 -. 84 -. 06 -. 21. 23. 11

Spiritual Well-Being in Relation to End of Life Despair Among Cancer Patients Regression models predicting end-of-life despair from Meaning, Faith and Depression FACIT Meaning subscale FACIT Faith subscale Depression (HDRS) (Correlations in bold are significant, p <. 05) BHS -. 44 -. 18. 26 SAHD SI -. 44 -. 84 -. 06 -. 21. 23. 11

A Meta-Analysis of Meaning and it’s Relation to Distress in Cancer Patients In a meta-analysis of 62 studies examining the relationship between “Meaning in Life” ( usually measured by the FACIT-SWB) and distress in cancer patients: Meaning in life demonstrated significant negative associations with cancer distress (r= -0. 41, 95% CI= -0. 47 to -0. 35, k=44) Winger JG et al, Psycho-oncology, E pub ahead of print 2015.

A Meta-Analysis of Meaning and it’s Relation to Distress in Cancer Patients In a meta-analysis of 62 studies examining the relationship between “Meaning in Life” ( usually measured by the FACIT-SWB) and distress in cancer patients: Meaning in life demonstrated significant negative associations with cancer distress (r= -0. 41, 95% CI= -0. 47 to -0. 35, k=44) Winger JG et al, Psycho-oncology, E pub ahead of print 2015.

Viktor E. Frankl, M. D. (1905 -1997)

Viktor E. Frankl, M. D. (1905 -1997)

Meaning Centered Psychotherapy Basic Concepts Meaning: 1. Meaning of Life - Life has meaning and never ceases to have meaning. The possibility of creating or experiencing meaning exists until the last moments of life 2. Will to Meaning - The desire to find meaning in human existence is a third primary and basic motivation for human behavior; (i. e. libido, will to power, will to meaning). 3. Freedom of Will - Freedom to find meaning in existence and to choose one’s attitude towards suffering; to choose how we respond to uncertainty

Meaning Centered Psychotherapy Basic Concepts Meaning: 1. Meaning of Life - Life has meaning and never ceases to have meaning. The possibility of creating or experiencing meaning exists until the last moments of life 2. Will to Meaning - The desire to find meaning in human existence is a third primary and basic motivation for human behavior; (i. e. libido, will to power, will to meaning). 3. Freedom of Will - Freedom to find meaning in existence and to choose one’s attitude towards suffering; to choose how we respond to uncertainty

Meaning Centered Psychotherapy Basic Concepts The Sources of Meaning: Achieving Transcendence 1. Creativity - work, deeds, causes 2. Experience - nature, art, relationships 3. Attitude - the attitude one takes towards suffering and existential problems; limitations, uncertain future 4. Historical - individual, family, community history; Legacy: past, present, future

Meaning Centered Psychotherapy Basic Concepts The Sources of Meaning: Achieving Transcendence 1. Creativity - work, deeds, causes 2. Experience - nature, art, relationships 3. Attitude - the attitude one takes towards suffering and existential problems; limitations, uncertain future 4. Historical - individual, family, community history; Legacy: past, present, future

Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy Session Topics & Themes • Session #1: Concepts & Sources of Meaning – Introductions to Intervention & Meaning • Session #2: Cancer & Meaning – Identity – Before & After Cancer Diagnosis • Session #3: Historical Sources of Meaning – Life as a Living Legacy (past-present-future) • Session #4: Historical Sources of Meaning – Life as a Living Legacy (past-present-future) • Session #5: Attitudinal Sources of Meaning – Encountering Life’s Limitations • Session #6: Creative Sources of Meaning – Actively Engaging in Life (via: creativity & responsibility) • Session #7: Experiential Sources of Meaning – Connecting with Life (via: love, beauty & humor) • Session #8: Transitions – Reflections & hopes for future

Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy Session Topics & Themes • Session #1: Concepts & Sources of Meaning – Introductions to Intervention & Meaning • Session #2: Cancer & Meaning – Identity – Before & After Cancer Diagnosis • Session #3: Historical Sources of Meaning – Life as a Living Legacy (past-present-future) • Session #4: Historical Sources of Meaning – Life as a Living Legacy (past-present-future) • Session #5: Attitudinal Sources of Meaning – Encountering Life’s Limitations • Session #6: Creative Sources of Meaning – Actively Engaging in Life (via: creativity & responsibility) • Session #7: Experiential Sources of Meaning – Connecting with Life (via: love, beauty & humor) • Session #8: Transitions – Reflections & hopes for future

Session #1 Concepts and Sources of Meaning: Experiential Exercises • List one or two experiences or moments when life has felt particularly meaningful to you- whether it sounds powerful or mundane. For example, it could be something that helped you through a difficult day, or a time when you felt most alive.

Session #1 Concepts and Sources of Meaning: Experiential Exercises • List one or two experiences or moments when life has felt particularly meaningful to you- whether it sounds powerful or mundane. For example, it could be something that helped you through a difficult day, or a time when you felt most alive.

Session # 2 Cancer and Meaning: Experiential Exercises • Write down 4 answers to the question, “Who am I? ” These can be positive or negative, and include personality characteristics, body image, beliefs, things you do, people you know, etc…. For example, answers might start with, “I am someone who___ , ” or “I am a __. ” • How has cancer affected your answers?

Session # 2 Cancer and Meaning: Experiential Exercises • Write down 4 answers to the question, “Who am I? ” These can be positive or negative, and include personality characteristics, body image, beliefs, things you do, people you know, etc…. For example, answers might start with, “I am someone who___ , ” or “I am a __. ” • How has cancer affected your answers?

Sessions # 3 & 4 Meaning & the Historical Context of Life: Experiential Exercises • Tell us the story of your name. • Tell us about your life and the history of your family. • What are your most important accomplishments, and what do you feel most proud of? • What have you learned about life that you would want to pass on to others?

Sessions # 3 & 4 Meaning & the Historical Context of Life: Experiential Exercises • Tell us the story of your name. • Tell us about your life and the history of your family. • What are your most important accomplishments, and what do you feel most proud of? • What have you learned about life that you would want to pass on to others?

Session # 5 - Meaning & Attitudinal Values: Limitations, Finiteness of Life • Are you still able to find meaning in your daily life despite the finiteness of life? • Since your diagnosis, have you felt a sense of a loss of meaning in life? That life is not worth living? • Thoughts about what is a “good” or “meaningful” death. • Thoughts about what happens after death?

Session # 5 - Meaning & Attitudinal Values: Limitations, Finiteness of Life • Are you still able to find meaning in your daily life despite the finiteness of life? • Since your diagnosis, have you felt a sense of a loss of meaning in life? That life is not worth living? • Thoughts about what is a “good” or “meaningful” death. • Thoughts about what happens after death?

Session # 6 - Meaning Derived from Creative Values & Responsibility • What are your responsibilities? • What are the tasks you have for your life? • Who are you responsible to and for? • What is your unfinished business? • What tasks have you always wanted to do, but have yet to undertake?

Session # 6 - Meaning Derived from Creative Values & Responsibility • What are your responsibilities? • What are the tasks you have for your life? • Who are you responsible to and for? • What is your unfinished business? • What tasks have you always wanted to do, but have yet to undertake?

Session # 7 - Meaning & Experiential Values: Love, Nature, Art, Beauty, Humor: • List and discuss 3 things that strike you as beautiful and still make you feel alive. • List 3 things that still make you laugh.

Session # 7 - Meaning & Experiential Values: Love, Nature, Art, Beauty, Humor: • List and discuss 3 things that strike you as beautiful and still make you feel alive. • List 3 things that still make you laugh.

Session # 8 - Transitions • Process Termination • Review of memoirs, legacy project • Review sources of meaning • Hopes for future- List 3 hopes for the future • Saying good-bye

Session # 8 - Transitions • Process Termination • Review of memoirs, legacy project • Review sources of meaning • Hopes for future- List 3 hopes for the future • Saying good-bye

Meaning Centered Psychotherapy in Advanced Cancer • Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy, in Group and Individual Formats, has been demonstrated in multiple Randomized Controlled Trials to: – Enhance Spiritual Well Being, Meaning, Faith, – Enhance Quality of Life – Decrease Hopelessness, Desire for Hastened Death, Symptom Distress, Depression, Anxiety Funding: R 21 AT/CA 0103; RO 1 CA 128134; R 01 CA 128187; Fetzer Institute; Kohlberg Foundation Breitbart et al, Psycho-oncology 2010, Breitbart, et al 2002, 2004, 2006 Breitbart et al, JCO 30: 1304 -1309, 2012, Breitbart et al JCO 33: 749 -54 2015

Meaning Centered Psychotherapy in Advanced Cancer • Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy, in Group and Individual Formats, has been demonstrated in multiple Randomized Controlled Trials to: – Enhance Spiritual Well Being, Meaning, Faith, – Enhance Quality of Life – Decrease Hopelessness, Desire for Hastened Death, Symptom Distress, Depression, Anxiety Funding: R 21 AT/CA 0103; RO 1 CA 128134; R 01 CA 128187; Fetzer Institute; Kohlberg Foundation Breitbart et al, Psycho-oncology 2010, Breitbart, et al 2002, 2004, 2006 Breitbart et al, JCO 30: 1304 -1309, 2012, Breitbart et al JCO 33: 749 -54 2015

Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy for Advanced Cancer Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial to Enhance Spiritual Well-Being at the End of Life NCI Grant # R 01 CA 128187 William Breitbart, M. D. (Principal Investigator) Hayley Pessin, Ph. D. Wendy Lichtenthal, Ph. D. Allison Applebaum, Ph. D. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Barry Rosenfeld, Ph. D. (Co-Investigator) Fordham University Breitbart et al. (in press). Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy for Advanced Cancer Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial to Enhance Spiritual Well-Being at the End of Life NCI Grant # R 01 CA 128187 William Breitbart, M. D. (Principal Investigator) Hayley Pessin, Ph. D. Wendy Lichtenthal, Ph. D. Allison Applebaum, Ph. D. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Barry Rosenfeld, Ph. D. (Co-Investigator) Fordham University Breitbart et al. (in press). Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Methods • Patients with stage III or IV cancer (solid tumors or Non. Hodgkins Lymphomas) were recruited for participation in the study. • Eligible patients with these diagnoses included those receiving ambulatory care at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City non-Memorial patients. • Patients were randomized to receive either Meaning. Centered Group Psychotherapy or Supportive Group Psychotherapy weekly for 8 weeks. Both therapies were manualized. • Patients were evaluated with a battery of self-report and clinician-rated measures pre-intervention, postintervention, and at a 2 -month follow-up.

Methods • Patients with stage III or IV cancer (solid tumors or Non. Hodgkins Lymphomas) were recruited for participation in the study. • Eligible patients with these diagnoses included those receiving ambulatory care at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City non-Memorial patients. • Patients were randomized to receive either Meaning. Centered Group Psychotherapy or Supportive Group Psychotherapy weekly for 8 weeks. Both therapies were manualized. • Patients were evaluated with a battery of self-report and clinician-rated measures pre-intervention, postintervention, and at a 2 -month follow-up.

MCGP Trial – Study Measures • Spiritual Well-Being (Meaning; Faith) – FACIT Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-SWB) • Quality of Life – MQOL: Mc. Gill Quality of Life Questionnaire • Depression – Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) • Anxiety – Hospital Anxiety & Depression Scale-Anxiety Subscale (HADS-A) • Hopelessness – Hopelessness Assessment in Illness (HAI) • Desire for Hastened Death – Schedule of Attitudes Toward Hastened Death (SAHD) • Physical Symptom Distress – Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS)

MCGP Trial – Study Measures • Spiritual Well-Being (Meaning; Faith) – FACIT Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-SWB) • Quality of Life – MQOL: Mc. Gill Quality of Life Questionnaire • Depression – Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) • Anxiety – Hospital Anxiety & Depression Scale-Anxiety Subscale (HADS-A) • Hopelessness – Hopelessness Assessment in Illness (HAI) • Desire for Hastened Death – Schedule of Attitudes Toward Hastened Death (SAHD) • Physical Symptom Distress – Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS)

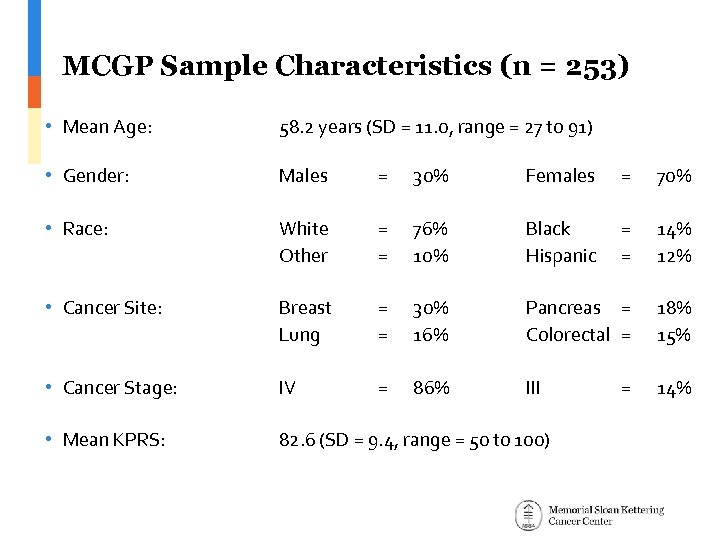

MCGP Sample Characteristics (n = 253) • Mean Age: 58. 2 years (SD = 11. 0, range = 27 to 91) • Gender: Males = 30% Females = 70% • Race: White Other = = 76% 10% Black Hispanic = = 14% 12% • Cancer Site: Breast Lung = = 30% 16% Pancreas = Colorectal = 18% 15% • Cancer Stage: IV = 86% III 14% • Mean KPRS: 82. 6 (SD = 9. 4, range = 50 to 100) =

MCGP Sample Characteristics (n = 253) • Mean Age: 58. 2 years (SD = 11. 0, range = 27 to 91) • Gender: Males = 30% Females = 70% • Race: White Other = = 76% 10% Black Hispanic = = 14% 12% • Cancer Site: Breast Lung = = 30% 16% Pancreas = Colorectal = 18% 15% • Cancer Stage: IV = 86% III 14% • Mean KPRS: 82. 6 (SD = 9. 4, range = 50 to 100) =

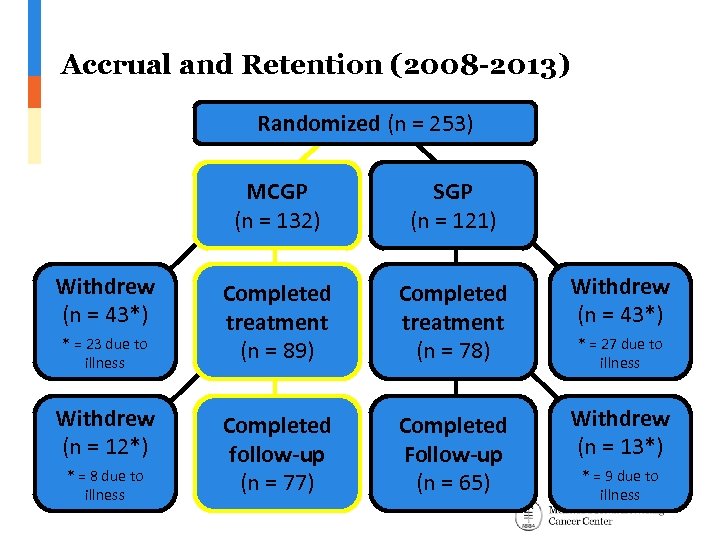

Accrual and Retention (2008 -2013) Randomized (n = 253) MCGP (n = 132) Withdrew (n = 43*) * = 23 due to illness Withdrew (n = 12*) * = 8 due to illness SGP (n = 121) Completed treatment (n = 89) Completed treatment (n = 78) Withdrew (n = 43*) Completed follow-up (n = 77) Completed Follow-up (n = 65) Withdrew (n = 13*) * = 27 due to illness * = 9 due to illness

Accrual and Retention (2008 -2013) Randomized (n = 253) MCGP (n = 132) Withdrew (n = 43*) * = 23 due to illness Withdrew (n = 12*) * = 8 due to illness SGP (n = 121) Completed treatment (n = 89) Completed treatment (n = 78) Withdrew (n = 43*) Completed follow-up (n = 77) Completed Follow-up (n = 65) Withdrew (n = 13*) * = 27 due to illness * = 9 due to illness

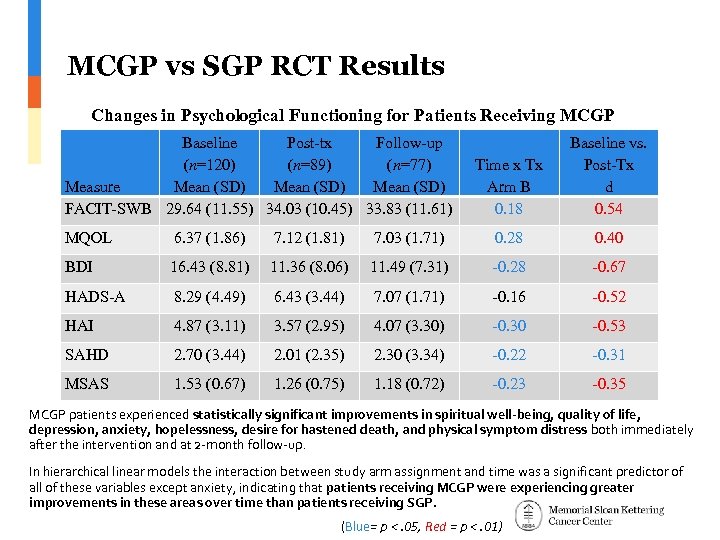

MCGP vs SGP RCT Results Changes in Psychological Functioning for Patients Receiving MCGP Baseline Post-tx Follow-up (n=120) (n=89) (n=77) Measure Mean (SD) FACIT-SWB 29. 64 (11. 55) 34. 03 (10. 45) 33. 83 (11. 61) Time x Tx Arm B 0. 18 Baseline vs. Post-Tx d 0. 54 MQOL 6. 37 (1. 86) 7. 12 (1. 81) 7. 03 (1. 71) 0. 28 0. 40 BDI 16. 43 (8. 81) 11. 36 (8. 06) 11. 49 (7. 31) -0. 28 -0. 67 HADS-A 8. 29 (4. 49) 6. 43 (3. 44) 7. 07 (1. 71) -0. 16 -0. 52 HAI 4. 87 (3. 11) 3. 57 (2. 95) 4. 07 (3. 30) -0. 30 -0. 53 SAHD 2. 70 (3. 44) 2. 01 (2. 35) 2. 30 (3. 34) -0. 22 -0. 31 MSAS 1. 53 (0. 67) 1. 26 (0. 75) 1. 18 (0. 72) -0. 23 -0. 35 MCGP patients experienced statistically significant improvements in spiritual well-being, quality of life, depression, anxiety, hopelessness, desire for hastened death, and physical symptom distress both immediately after the intervention and at 2 -month follow-up. In hierarchical linear models the interaction between study arm assignment and time was a significant predictor of all of these variables except anxiety, indicating that patients receiving MCGP were experiencing greater improvements in these areas over time than patients receiving SGP. (Blue= p <. 05, Red = p <. 01)

MCGP vs SGP RCT Results Changes in Psychological Functioning for Patients Receiving MCGP Baseline Post-tx Follow-up (n=120) (n=89) (n=77) Measure Mean (SD) FACIT-SWB 29. 64 (11. 55) 34. 03 (10. 45) 33. 83 (11. 61) Time x Tx Arm B 0. 18 Baseline vs. Post-Tx d 0. 54 MQOL 6. 37 (1. 86) 7. 12 (1. 81) 7. 03 (1. 71) 0. 28 0. 40 BDI 16. 43 (8. 81) 11. 36 (8. 06) 11. 49 (7. 31) -0. 28 -0. 67 HADS-A 8. 29 (4. 49) 6. 43 (3. 44) 7. 07 (1. 71) -0. 16 -0. 52 HAI 4. 87 (3. 11) 3. 57 (2. 95) 4. 07 (3. 30) -0. 30 -0. 53 SAHD 2. 70 (3. 44) 2. 01 (2. 35) 2. 30 (3. 34) -0. 22 -0. 31 MSAS 1. 53 (0. 67) 1. 26 (0. 75) 1. 18 (0. 72) -0. 23 -0. 35 MCGP patients experienced statistically significant improvements in spiritual well-being, quality of life, depression, anxiety, hopelessness, desire for hastened death, and physical symptom distress both immediately after the intervention and at 2 -month follow-up. In hierarchical linear models the interaction between study arm assignment and time was a significant predictor of all of these variables except anxiety, indicating that patients receiving MCGP were experiencing greater improvements in these areas over time than patients receiving SGP. (Blue= p <. 05, Red = p <. 01)

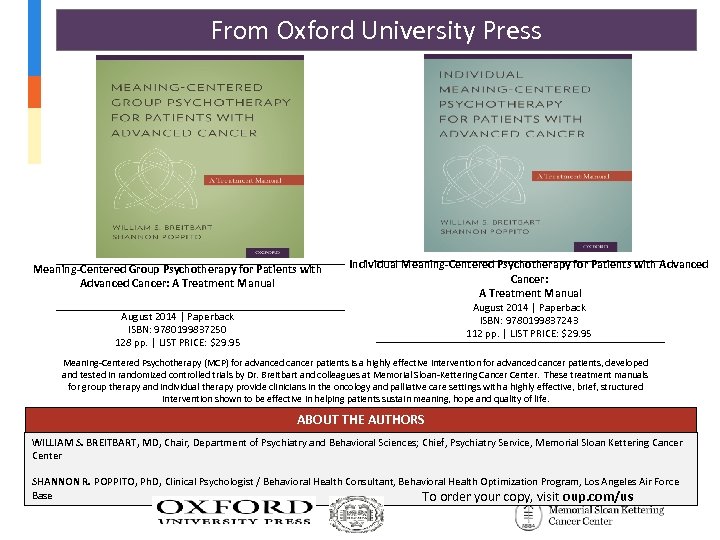

From Oxford University Press Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Treatment Manual Individual Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Treatment Manual August 2014 │ Paperback ISBN: 9780199837243 112 pp. │ LIST PRICE: $29. 95 August 2014 │ Paperback ISBN: 9780199837250 128 pp. │ LIST PRICE: $29. 95 Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP) for advanced cancer patients is a highly effective intervention for advanced cancer patients, developed and tested in randomized controlled trials by Dr. Breitbart and colleagues at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. These treatment manuals for group therapy and individual therapy provide clinicians in the oncology and palliative care settings with a highly effective, brief, structured intervention shown to be effective in helping patients sustain meaning, hope and quality of life. ABOUT THE AUTHORS WILLIAM S. BREITBART, MD, Chair, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences; Chief, Psychiatry Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center SHANNON R. POPPITO, Ph. D, Clinical Psychologist / Behavioral Health Consultant, Behavioral Health Optimization Program, Los Angeles Air Force Base To order your copy, visit oup. com/us

From Oxford University Press Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Treatment Manual Individual Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Treatment Manual August 2014 │ Paperback ISBN: 9780199837243 112 pp. │ LIST PRICE: $29. 95 August 2014 │ Paperback ISBN: 9780199837250 128 pp. │ LIST PRICE: $29. 95 Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP) for advanced cancer patients is a highly effective intervention for advanced cancer patients, developed and tested in randomized controlled trials by Dr. Breitbart and colleagues at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. These treatment manuals for group therapy and individual therapy provide clinicians in the oncology and palliative care settings with a highly effective, brief, structured intervention shown to be effective in helping patients sustain meaning, hope and quality of life. ABOUT THE AUTHORS WILLIAM S. BREITBART, MD, Chair, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences; Chief, Psychiatry Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center SHANNON R. POPPITO, Ph. D, Clinical Psychologist / Behavioral Health Consultant, Behavioral Health Optimization Program, Los Angeles Air Force Base To order your copy, visit oup. com/us

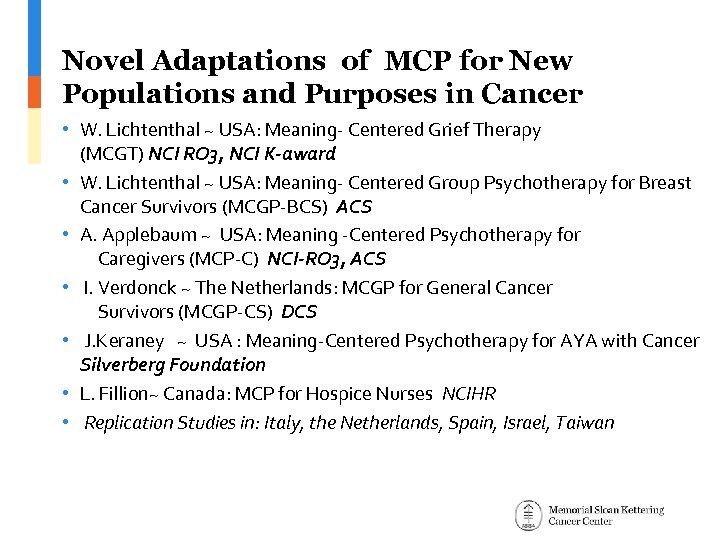

Novel Adaptations of MCP for New Populations and Purposes in Cancer • W. Lichtenthal ~ USA: Meaning- Centered Grief Therapy (MCGT) NCI RO 3, NCI K-award • W. Lichtenthal ~ USA: Meaning- Centered Group Psychotherapy for Breast Cancer Survivors (MCGP-BCS) ACS • A. Applebaum ~ USA: Meaning -Centered Psychotherapy for Caregivers (MCP-C) NCI-RO 3, ACS • I. Verdonck ~ The Netherlands: MCGP for General Cancer Survivors (MCGP-CS) DCS • J. Keraney ~ USA : Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for AYA with Cancer Silverberg Foundation • L. Fillion~ Canada: MCP for Hospice Nurses NCIHR • Replication Studies in: Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Israel, Taiwan

Novel Adaptations of MCP for New Populations and Purposes in Cancer • W. Lichtenthal ~ USA: Meaning- Centered Grief Therapy (MCGT) NCI RO 3, NCI K-award • W. Lichtenthal ~ USA: Meaning- Centered Group Psychotherapy for Breast Cancer Survivors (MCGP-BCS) ACS • A. Applebaum ~ USA: Meaning -Centered Psychotherapy for Caregivers (MCP-C) NCI-RO 3, ACS • I. Verdonck ~ The Netherlands: MCGP for General Cancer Survivors (MCGP-CS) DCS • J. Keraney ~ USA : Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for AYA with Cancer Silverberg Foundation • L. Fillion~ Canada: MCP for Hospice Nurses NCIHR • Replication Studies in: Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Israel, Taiwan

MEANING-CENTERED PSYCHOTHERAPY R 25 TRAINING PROGRAM Learn principles, techniques, and applications of Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy Our comprehensive two-day training will feature lectures, manual review, simulated patient role plays Funded by NCI, Grant #1 R 25 CA 190169, William Breitbart (PI) MEMORIAL SLOAN KETTERING CANCER CENTER For more information Email: psytrain. MCP@mskcc. org breitbaw@mskcc. org www. mskcc. org/psycho-oncology

MEANING-CENTERED PSYCHOTHERAPY R 25 TRAINING PROGRAM Learn principles, techniques, and applications of Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy Our comprehensive two-day training will feature lectures, manual review, simulated patient role plays Funded by NCI, Grant #1 R 25 CA 190169, William Breitbart (PI) MEMORIAL SLOAN KETTERING CANCER CENTER For more information Email: psytrain. MCP@mskcc. org breitbaw@mskcc. org www. mskcc. org/psycho-oncology

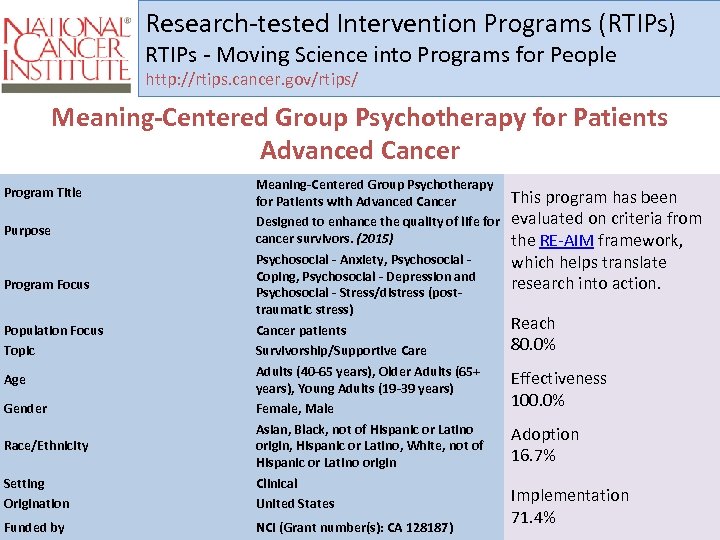

Research-tested Intervention Programs (RTIPs) RTIPs - Moving Science into Programs for People http: //rtips. cancer. gov/rtips/ Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy for Patients Advanced Cancer Setting Origination Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer Designed to enhance the quality of life for cancer survivors. (2015) Psychosocial - Anxiety, Psychosocial Coping, Psychosocial - Depression and Psychosocial - Stress/distress (posttraumatic stress) Cancer patients Survivorship/Supportive Care Adults (40 -65 years), Older Adults (65+ years), Young Adults (19 -39 years) Female, Male Asian, Black, not of Hispanic or Latino origin, Hispanic or Latino, White, not of Hispanic or Latino origin Clinical United States Funded by NCI (Grant number(s): CA 128187) Program Title Purpose Program Focus Population Focus Topic Age Gender Race/Ethnicity This program has been evaluated on criteria from the RE-AIM framework, which helps translate research into action. Reach 80. 0% Effectiveness 100. 0% Adoption 16. 7% Implementation 71. 4%

Research-tested Intervention Programs (RTIPs) RTIPs - Moving Science into Programs for People http: //rtips. cancer. gov/rtips/ Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy for Patients Advanced Cancer Setting Origination Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer Designed to enhance the quality of life for cancer survivors. (2015) Psychosocial - Anxiety, Psychosocial Coping, Psychosocial - Depression and Psychosocial - Stress/distress (posttraumatic stress) Cancer patients Survivorship/Supportive Care Adults (40 -65 years), Older Adults (65+ years), Young Adults (19 -39 years) Female, Male Asian, Black, not of Hispanic or Latino origin, Hispanic or Latino, White, not of Hispanic or Latino origin Clinical United States Funded by NCI (Grant number(s): CA 128187) Program Title Purpose Program Focus Population Focus Topic Age Gender Race/Ethnicity This program has been evaluated on criteria from the RE-AIM framework, which helps translate research into action. Reach 80. 0% Effectiveness 100. 0% Adoption 16. 7% Implementation 71. 4%