081ebcba02c494fa912a19b39cd7338c.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 156

International Business Environments & Operations Chapter 2: Culture 15 e, Global Edition Daniels ● Radebaugh ● Sullivan Adapted from a PPT presentation provided by and Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 1

Intreoduction All overheads will not be discussed in class; they are provided for the students’ additional learning and review p Good source of definitions and explanations: http: //www. businessdictionary. com/ p Multicultural Countries p (1) The USA 2

Home: Little Havana , and, Miami—”The capital of Latin America” p Little Havana is a neighborhood of Miami, Florida, United States. Home to many Cuban exiles, as well as many immigrants from Central and South America, Little Havana is named after Havana, the capital and largest city in Cuba. Little Havana miami florida - Yahoo Image Search Results Near my home in Little Havana; where I buy my Cuban sandwiches 3

Home: Little Havana, Miami, Florida— 13 th Avenue 4

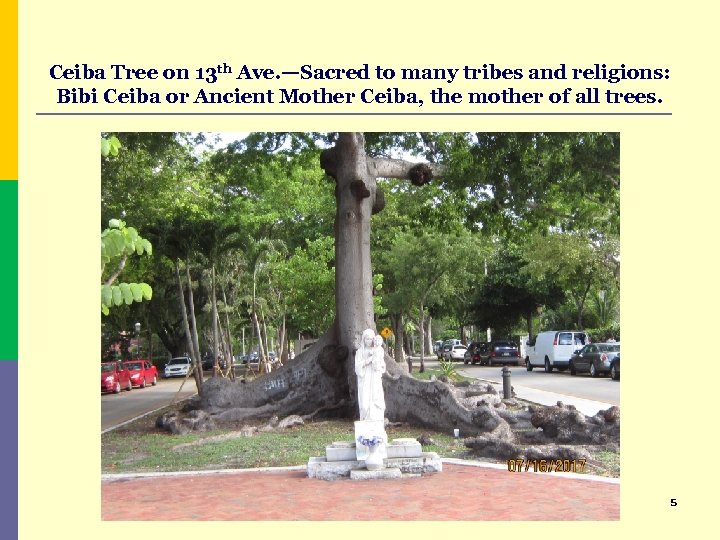

Ceiba Tree on 13 th Ave. —Sacred to many tribes and religions: Bibi Ceiba or Ancient Mother Ceiba, the mother of all trees. 5

Previous Home: Austin, Texas: Cinco de Mayo Mexican Festival p Texas was once part of Mexico, and still retains a lot of Mexican food, culture, architecture, and festivals. 6

Alpine Haus restaurant, New Braunfels, Texas, between Austin & San Antonio p Texas has a large population of historically German residents that still maintain some German customs, especially relating to food. We always stop here German influenced towns in Texas - for the split-pea Fredricksburg, New Braunfels, soup with sausage. Bergheim & Boerne. 7

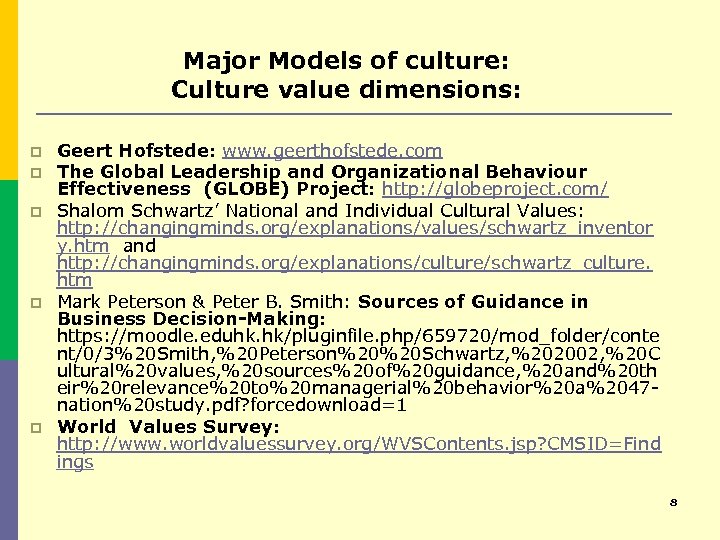

Major Models of culture: Culture value dimensions: p p p Geert Hofstede: www. geerthofstede. com The Global Leadership and Organizational Behaviour Effectiveness (GLOBE) Project: http: //globeproject. com/ Shalom Schwartz’ National and Individual Cultural Values: http: //changingminds. org/explanations/values/schwartz_inventor y. htm and http: //changingminds. org/explanations/culture/schwartz_culture. htm Mark Peterson & Peter B. Smith: Sources of Guidance in Business Decision-Making: https: //moodle. eduhk. hk/pluginfile. php/659720/mod_folder/conte nt/0/3%20 Smith, %20 Peterson%20%20 Schwartz, %202002, %20 C ultural%20 values, %20 sources%20 of%20 guidance, %20 and%20 th eir%20 relevance%20 to%20 managerial%20 behavior%20 a%2047 nation%20 study. pdf? forcedownload=1 World Values Survey: http: //www. worldvaluessurvey. org/WVSContents. jsp? CMSID=Find ings 8

Chapter 2 Culture 9

The Business of International Business is Culture p http: //www. academia. edu/15235543/Icon s_of_International_Business 10

Kinds of Culture: Organizational & Societal p ORGANIZATIIONAL CULTURE (Also called “corporate culture”): The values and behaviors that contribute to the unique social and psychological environment of an organization. p Organizational culture includes an organization's expectations, experiences, philosophy, and values that hold it together, and is expressed in its selfimage, inner workings, interactions with the outside world, and future expectations. 11

Kinds of Culture: Organizational p Organizational Culture is based on shared attitudes, beliefs, customs, and written and unwritten rules that have been developed over time and are considered appropriate. (1) the ways the organization conducts its business, treats its employees, customers, and the wider community, (2) the extent to which freedom is allowed in decision making, developing new ideas, and personal expression, (3) how power and information flow through its hierarchy, and (4) how committed employees are towards collective objectives. 12

Kinds of Culture: Organizational p Organizational culture affects the organization's productivity and performance, and provides guidelines on customer care and service, product quality and safety, attendance and punctuality, and concern for the environment. p Organizational culture also extends to productionmethods, marketing and advertising practices, and to new product creation. p Organizational culture tends to be unique for every organization and to be difficult to change. 13

Models of Organizational Culture p HOFSTEDE: https: //www. hofstedeinsights. com/models/organisationalculture/ Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) Project: https: //www. grovewell. com/wpcontent/uploads/pub-GLOBE-intro. pdf p 14

Learning Objectives • Understand methods for learning about cultural environments • Grasp the major causes of cultural difference and change • Discuss behavioral factors influencing countries’ business practices • Recognize the complexities of cross-cultural information differences, especially communications 2 -15

Learning Objectives • Analyze guidelines for cultural adjustment • Grasp the diverse ways that national cultures may evolve Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -16

Introduction Learning Objective: Understand methods for learning about cultural environments Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -17

Introduction • Culture refers to the learned norms based on values, attitudes, and beliefs of a group of people • Culture is an integral part of a nation’s operating environment • every business function is subject to potential cultural differences Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -18

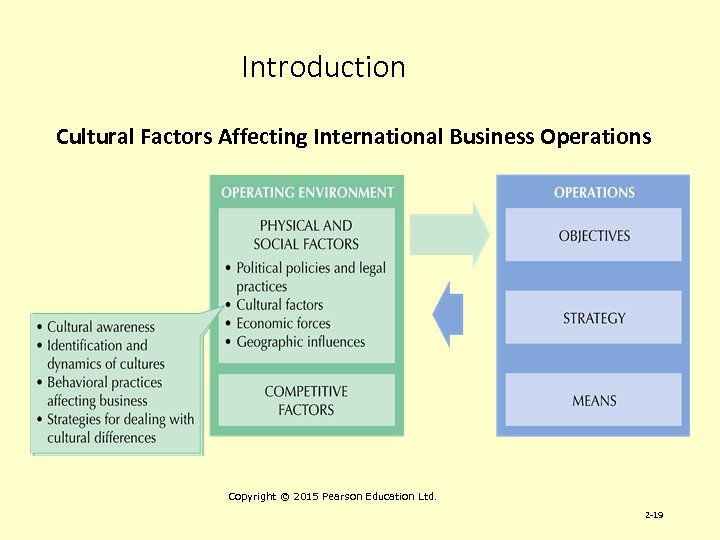

Introduction Cultural Factors Affecting International Business Operations Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -19

Introduction • Companies need to decide when to make cultural adjustments • Fostering cultural diversity can allow a company to gain a global competitive advantage by bringing together people of diverse backgrounds and experience Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -20

Introduction • But, cultural collision can occur when a company implements practices that are less effective or when employees encounter distress because of difficulty in accepting or adjusting to foreign behaviors Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -21

Cultural Awareness • Problem areas that can hinder managers’ cultural awareness… • Subconscious reactions to circumstances • The assumption that all societal subgroups are similar • Managers that educate themselves about other cultures have a greater chance of succeeding abroad Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -22

Culture and the Nation-State • The nation is a useful definition of society because similarity among people is a cause and an effect of national boundaries • laws apply primarily along national lines • language and values are shared within borders • rites and symbols are shared along national lines Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -23

Culture and the Nation-State • Country-by-country analysis can be difficult because • subcultures exist within nations • similarities link groups from different countries • Managers also need to focus on relevant groups 2 -24

How Cultures Form and Change Learning Objective: Grasp the major causes of cultural difference and change 2 -25

How Cultures Form and Change • Cultural value systems are established early in life but may change through • choice or imposition • cultural imperialism • contact with other cultures • cultural diffusion • creolization Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -26

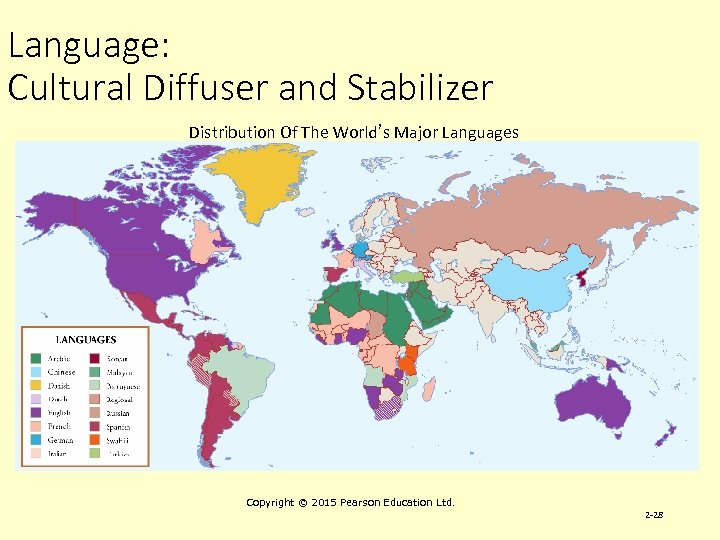

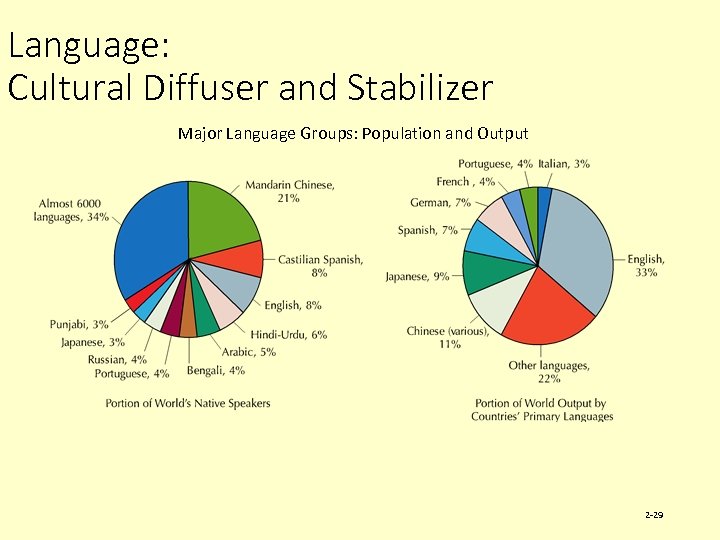

Language: Cultural Diffuser and Stabilizer • A common language within a country is a unifying force • A shared language between nations facilitates international business • Native English speaking countries account for a third of the world’s production • English is the international language of business Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -27

Language: Cultural Diffuser and Stabilizer Distribution Of The World’s Major Languages Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -28

Language: Cultural Diffuser and Stabilizer Major Language Groups: Population and Output 2 -29

Religion: Cultural Stabilizer • Religion impacts almost every business function • Centuries of profound religious influence continue to play a major role in shaping cultural values and behavior • many strong values are the result of a dominant religion 2 -30

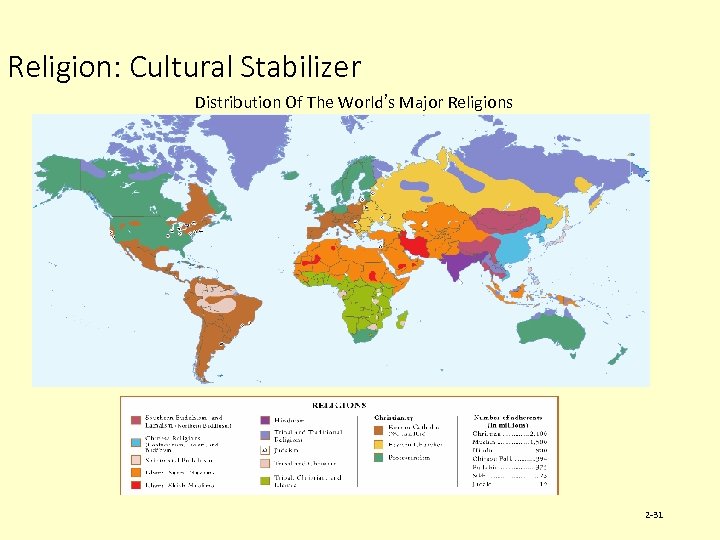

Religion: Cultural Stabilizer Distribution Of The World’s Major Religions 2 -31

Behavioral Practices Affecting Business Learning Objective: Discuss behavioral factors influencing countries’ business practices Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -32

Romie Littrell: My focus in teaching and research: Hofstede’s Model of Cultural Value Dimensions: http: //crossculturalcentre. homestead. com/values. ht ml 2 -33

The Business of International Business is Culture Prof. Romie Frederick Littrell Department of Management NRU-HSE-SPb rlittrell@hse. ru 34

Relevant publications to this presentation • Fetscherin, Marc, Ilan Alon, Romie Littrell, and Kit Kwong Allan CHAN. "In China? pick your brand name carefully. " Harvard Business Review (2012). Summarised at: https: //hbr. org/2012/09/in-china-pick-your-brand-namecarefully • Romie F. Littrell, Ilan Alon, Ka Wai CHAN, (2012) "Regional differences in managerial leader behaviour preferences in China", Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, Vol. 19 Issue: 3, pp. 315 -335, https: //doi. org/10. 1108/13527601211247071 35

Societal Culture Defined • Culture: • learned beliefs, values, rules, norms, symbols & traditions that are common to a specific group of people • shared qualities of a group that make them unique • is the way of life, customs, & scripts of a group of people • Terms related to culture – • Multicultural – approach or system that takes more than one culture into account • Diversity – existence of different cultures or ethnicities within a group or organization 36

Related Concepts • Ethnocentrism – • The tendency for individuals to place their own group (ethnic, racial, or cultural) at the center of their observations of the world • Perception that one’s own culture is better or more natural than other cultures • Is a universal tendency and each of us is ethnocentric to some degree • Ethnocentrism can be a major obstacle to effective business management and leadership • Prevents people from understanding or respecting other cultures 37

Hofstede: Why is culture so important? • Do we need to bother about culture? Every visitor of this site has her or his unique personality, history, and interest. At the same time, we share our human nature. We are group animals. We use language and empathy, and practice collaboration and inter-group competition. The unwritten rules of how we do these things differ from one human group to another. “Culture” is how we call these unwritten rules about how to be a good member of the group. 38

Hofstede: A Definition of Culture (in the anthropological sense) collective programming of the mind distinguishing the members of one group or category of people from another group/category -- can be nation, region, organization, profession, generation, gender • For review: not shown in class: Geert Hofstede on Culture – You. Tube 39

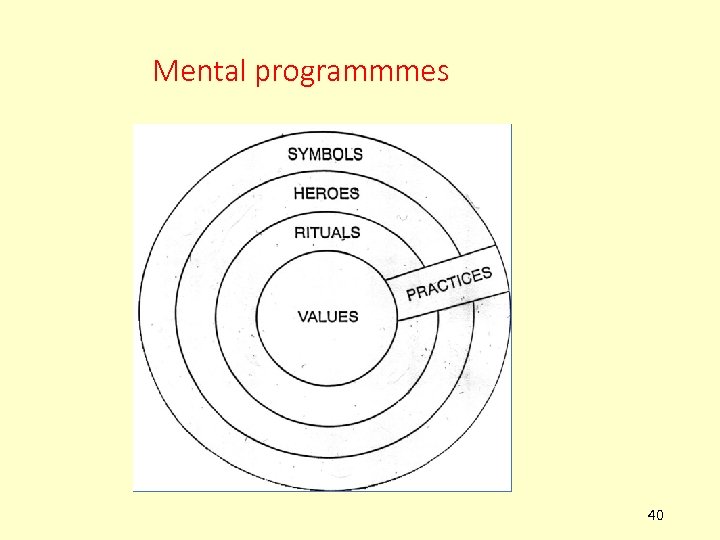

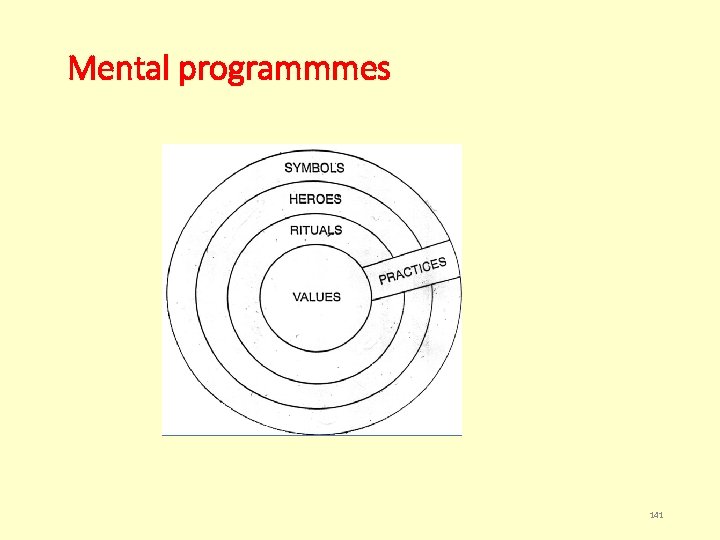

Mental programmmes 40

Values • Values are strong emotions with a minus and a plus pole • Like evil-good, abnormal-normal, dangerous-safe, dirty-clean, immoral, indecent-decent, unnatural, paradoxical-logical, uglybeautiful, irrational-rational • What is rational is a matter of values 41

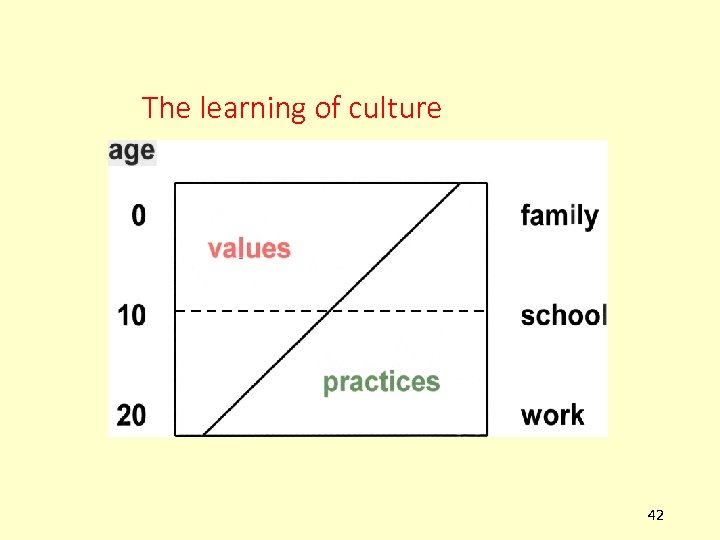

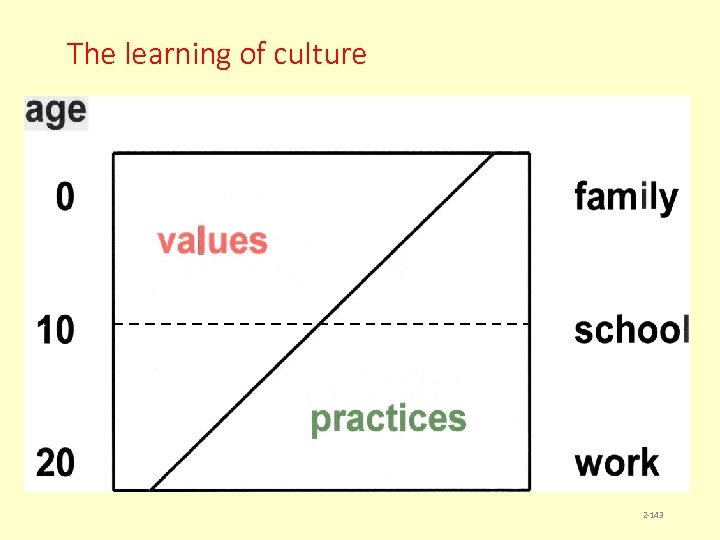

The learning of culture 42

National versus organizational cultures • National culture differences are rooted in values learned before age 10 • They pass from generation to generation • For organizations, they are given facts • Organizational cultures are rooted in practices learned on the job • Given enough management effort, they can be changed • International organizations are held together by shared practices, not by shared values 43

Research into national cultures Culture’s Consequences, Geert Hofstede, 1980 Initially 5 dimensions; LTO/STO added soon after 1980 book. 1. Inequality: more or less? Power Distance large vs. small 2. The unfamiliar: fight or tolerate? Uncertainty Avoidance strong vs. weak 3. Relation with in-group: loose or tight? Individualism vs. Collectivism 4. Emotional gender roles: different or same? Masculinity vs. Femininity 5. Need gratification: later or now? Long vs. Short term orientation 44

Hofstede’s website: http: //geerthofstede. com/ 45

National culture dimensions: reliable scores showing relative positions of > 70 countries • Initially based on employees of IBM subsidiaries in 40 countries around 1970 • Until 2002, 6 major replications (elites in nations, employees of other corporations, airline pilots, consumers, civil servants) • Results very stable – even if cultures shift, countries shift together so relative scores remain valid 46

Dimension 1: Power Distance • Extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations expect and accept that power is distributed unequally • Transferred to children by parents and other elders • Hofstede: 10 minutes on power distance: https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=Dq. AJcl wfy. Cw 47

Dimension 2: Uncertainty Avoidance • Extent to which members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous and unknown situations • Not to be confused with risk avoidance: risk is to uncertainty as fear is to anxiety. Uncertainty and anxiety are diffuse feelings – anything may happen • This dimension focuses on how cultures adapt to changes and cope with uncertainty. Emphasis is on extent to which a culture feels threatened or is anxious about ambiguity. It is not risk avoidance but rather, how one deals with ambiguity. • Hofstede, 10 minutes on Uncertainty Avoidance https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=f. ZF 6 Ly. Gne 7 Q 48

SMALL PD, WEAK UA NORDIC CTRS ANGLO CTRS, USA NETHERLANDS LARGE PD, WEAK UA CHINA, HK, SINGAPORE INDIA, BANGLADESH INDONESIA, MALAYSIA GERMAN SPEAKING CENTERS TAIWAN, THAILAND, PAKISTAN HUNGARY LATIN CENTERS, EASTEUROPE ISRAEL JAPAN, KOREA SMALL PD, STRONG UA LARGE PD, STRONG UA 49

Dimension 3: Individualism vs. Collectivism • Individualism: A society in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after self and immediate family • Collectivism: A society in which individuals from birth onwards are part of strong in-groups which last a lifetime, in return for loyalty to your ingroup you are provided support • Hofstede: 10 minutes on I/C: https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=z. Qj 1 VPNPHl. I 50

Dimension 4: Masculinity vs. Femininity • Masculinity: A society in which emotional gender roles are distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough and focused on material success, women on the quality of life • Femininity: A society in which emotional gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and focused on the quality of life • 10 minutes with Hofstede on Mas/Fem: https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=Pyr-XKQG 2 CM 51

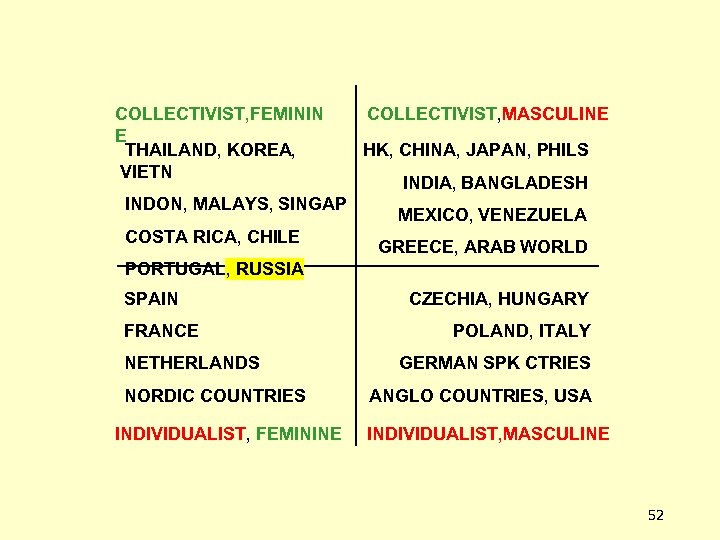

COLLECTIVIST, FEMININ E THAILAND, KOREA, VIETN INDON, MALAYS, SINGAP COSTA RICA, CHILE COLLECTIVIST, MASCULINE HK, CHINA, JAPAN, PHILS INDIA, BANGLADESH MEXICO, VENEZUELA GREECE, ARAB WORLD PORTUGAL, RUSSIA SPAIN CZECHIA, HUNGARY FRANCE POLAND, ITALY NETHERLANDS GERMAN SPK CTRIES NORDIC COUNTRIES ANGLO COUNTRIES, USA INDIVIDUALIST, FEMININE INDIVIDUALIST, MASCULINE 52

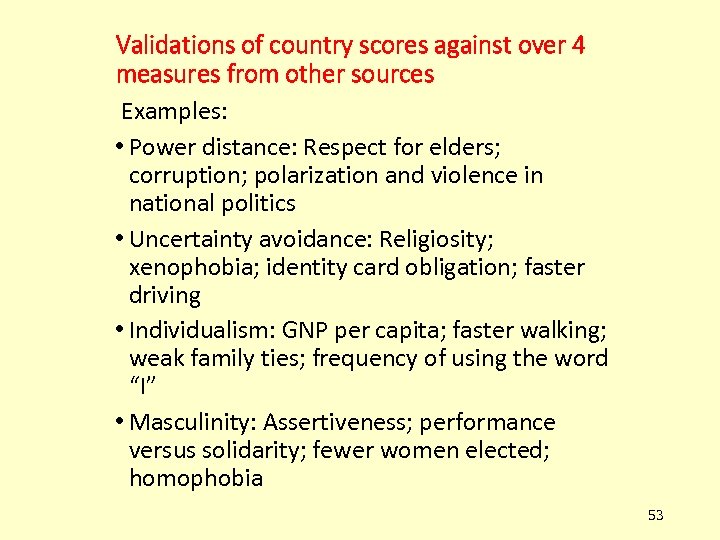

Validations of country scores against over 4 measures from other sources Examples: • Power distance: Respect for elders; corruption; polarization and violence in national politics • Uncertainty avoidance: Religiosity; xenophobia; identity card obligation; faster driving • Individualism: GNP per capita; faster walking; weak family ties; frequency of using the word “I” • Masculinity: Assertiveness; performance versus solidarity; fewer women elected; homophobia 53

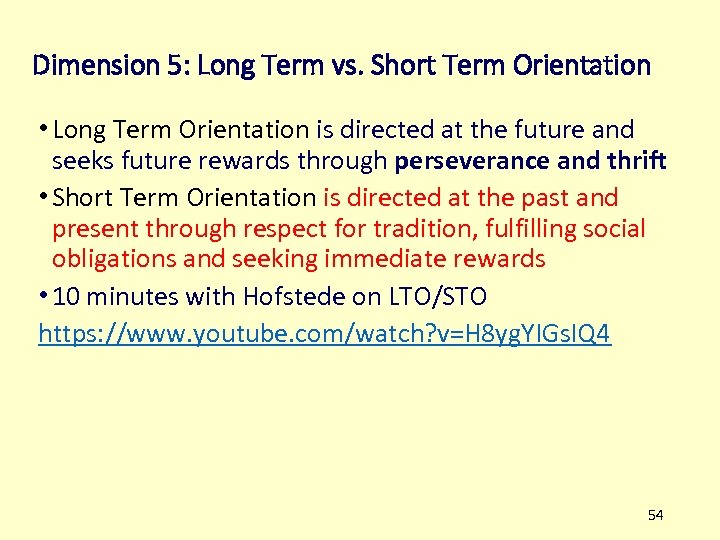

Dimension 5: Long Term vs. Short Term Orientation • Long Term Orientation is directed at the future and seeks future rewards through perseverance and thrift • Short Term Orientation is directed at the past and present through respect for tradition, fulfilling social obligations and seeking immediate rewards • 10 minutes with Hofstede on LTO/STO https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=H 8 yg. YIGs. IQ 4 54

LONG TERM ORIENTATION CHINA, HK, TAIWAN JAPAN, VIETNAM KOREA BRAZIL, INDIA THAILAND, SINGAPORE NETHERLANDS, NORDIC COUNTRIES BANGLADESH BELGIUM, FRANCE, GERMANY AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND USA, BRITAIN, CANADA SPAIN, PHILIPPINES AFRICAN COUNTRIES PAKISTAN SHORT TERM ORIENTATION 55

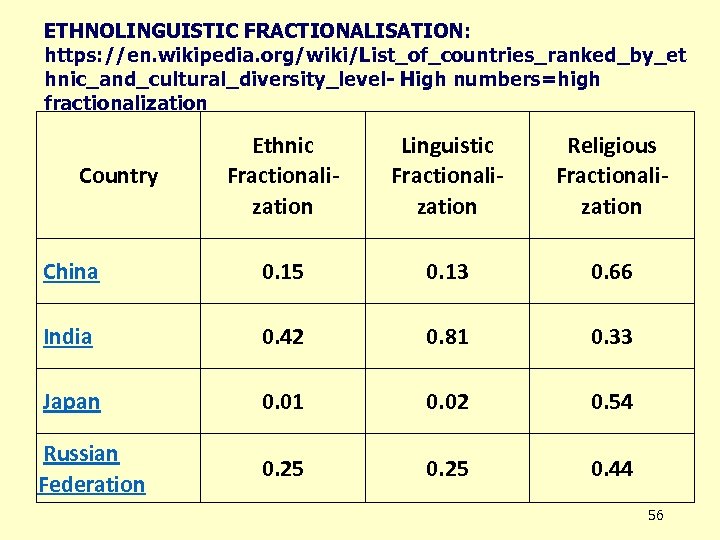

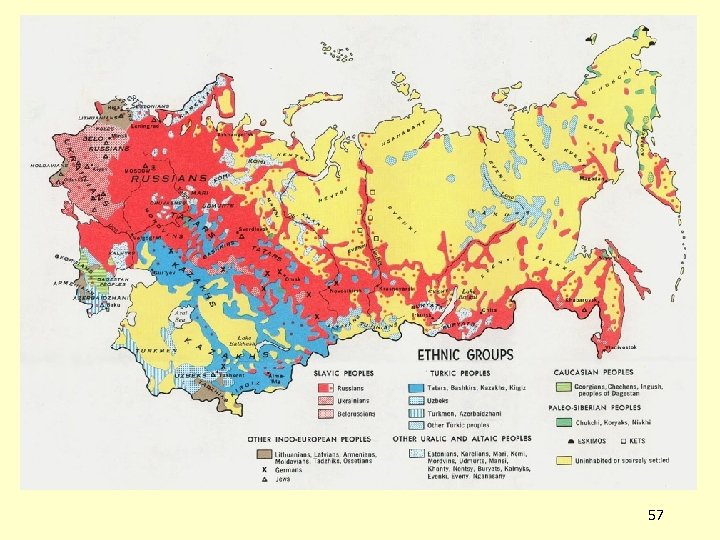

ETHNOLINGUISTIC FRACTIONALISATION: https: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/List_of_countries_ranked_by_et hnic_and_cultural_diversity_level- High numbers=high fractionalization Ethnic Fractionalization Linguistic Fractionalization Religious Fractionalization China 0. 15 0. 13 0. 66 India 0. 42 0. 81 0. 33 Japan 0. 01 0. 02 0. 54 Russian Federation 0. 25 0. 44 Country 56

57

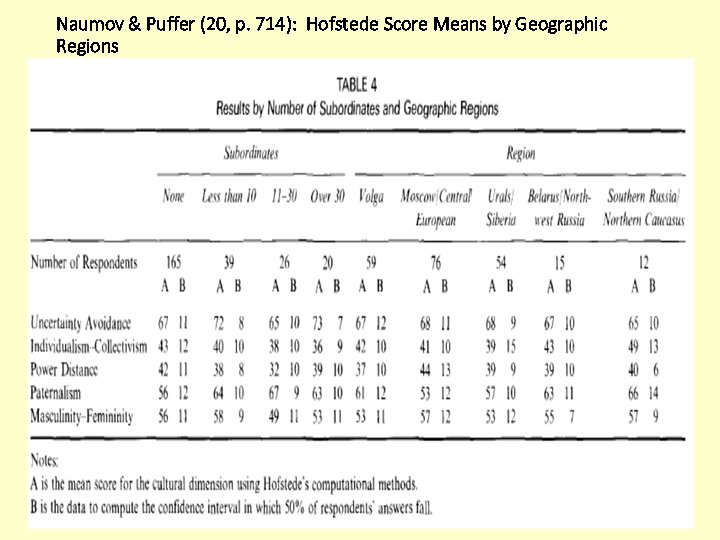

Naumov & Puffer (20, p. 714): Hofstede Score Means by Geographic Regions 58

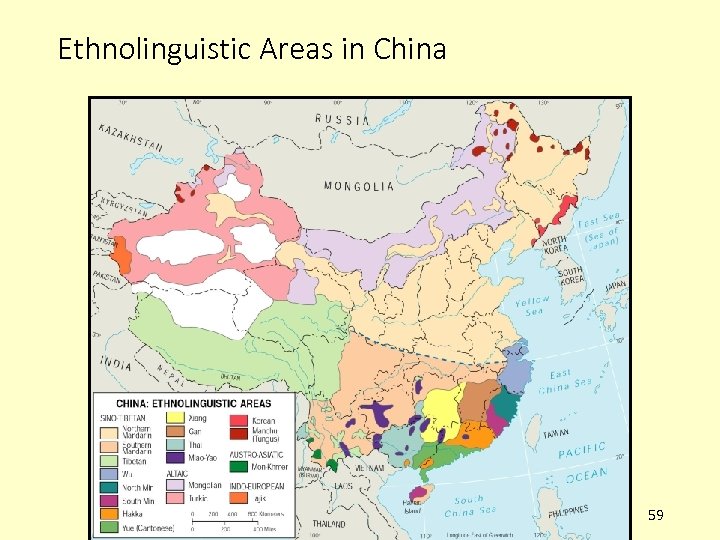

Ethnolinguistic Areas in China 59

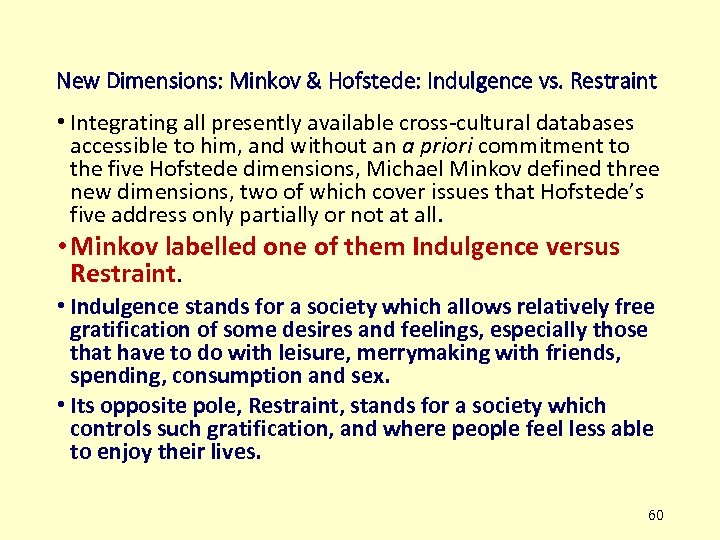

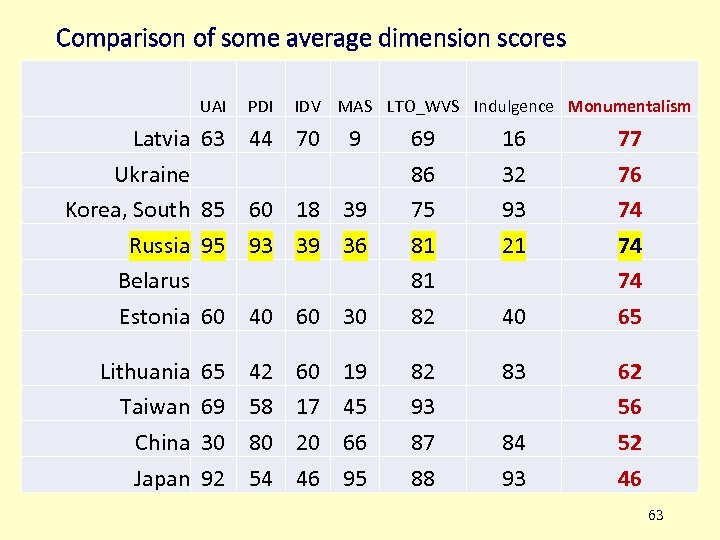

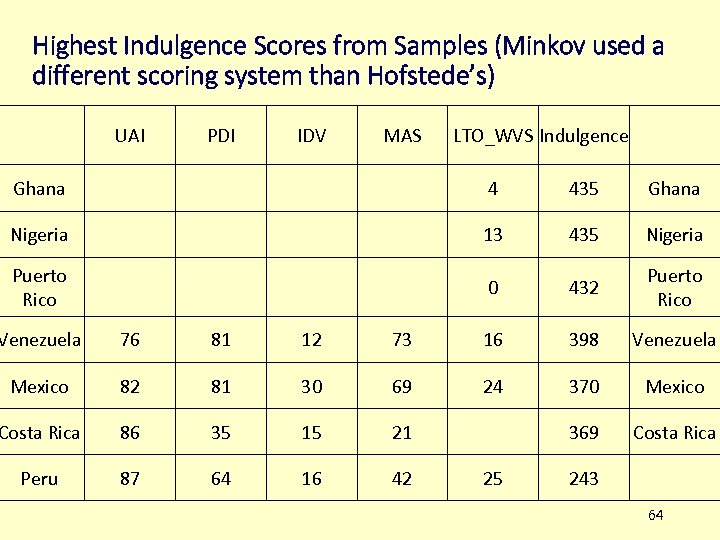

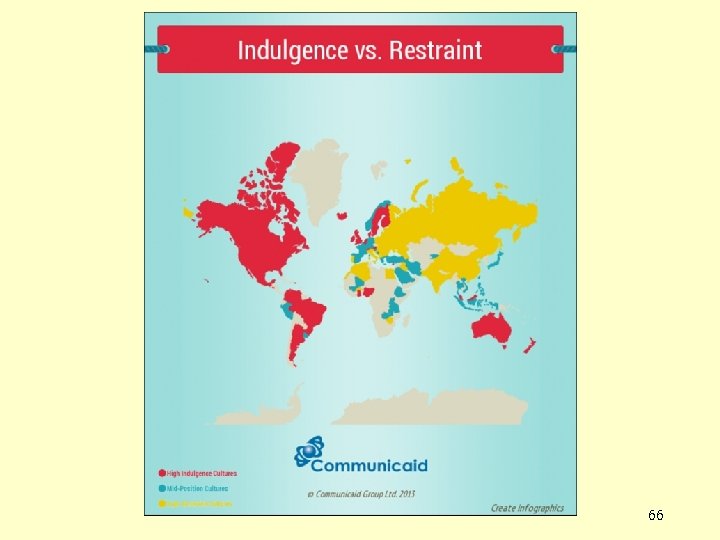

New Dimensions: Minkov & Hofstede: Indulgence vs. Restraint • Integrating all presently available cross-cultural databases accessible to him, and without an a priori commitment to the five Hofstede dimensions, Michael Minkov defined three new dimensions, two of which cover issues that Hofstede’s five address only partially or not at all. • Minkov labelled one of them Indulgence versus Restraint. • Indulgence stands for a society which allows relatively free gratification of some desires and feelings, especially those that have to do with leisure, merrymaking with friends, spending, consumption and sex. • Its opposite pole, Restraint, stands for a society which controls such gratification, and where people feel less able to enjoy their lives. 60

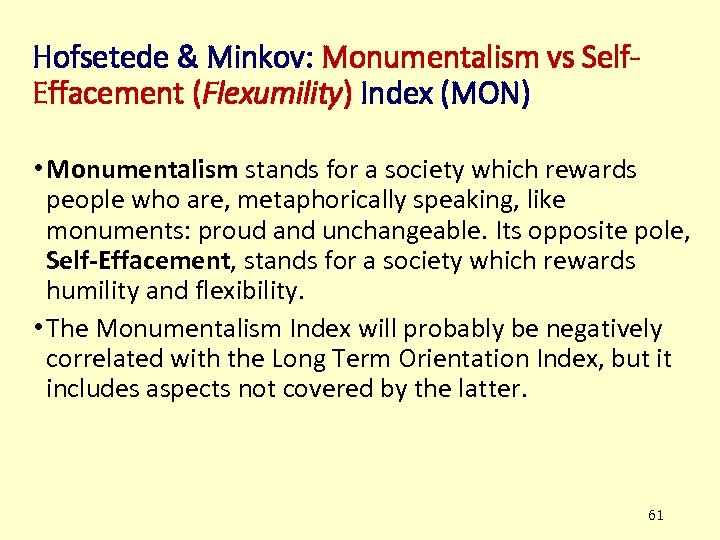

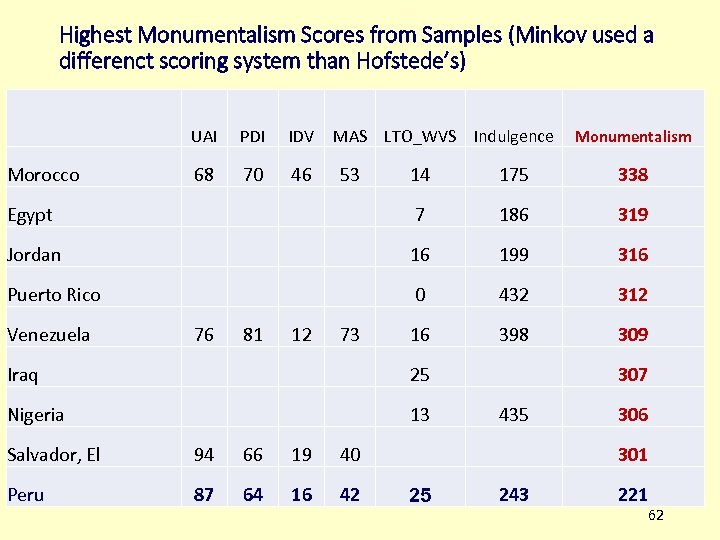

Hofsetede & Minkov: Monumentalism vs Self. Effacement (Flexumility) Index (MON) • Monumentalism stands for a society which rewards people who are, metaphorically speaking, like monuments: proud and unchangeable. Its opposite pole, Self-Effacement, stands for a society which rewards humility and flexibility. • The Monumentalism Index will probably be negatively correlated with the Long Term Orientation Index, but it includes aspects not covered by the latter. 61

Highest Monumentalism Scores from Samples (Minkov used a differenct scoring system than Hofstede’s) UAI Morocco PDI IDV 68 70 46 MAS LTO_WVS Indulgence 14 175 338 Egypt 7 186 319 Jordan 16 199 316 Puerto Rico 0 432 312 16 398 309 Venezuela 76 81 12 53 Monumentalism 73 Iraq 25 Nigeria 13 Salvador, El 94 66 19 40 87 64 16 42 25 435 Peru 307 306 301 243 221 62

Comparison of some average dimension scores UAI Latvia Ukraine Korea, South Russia Belarus Estonia PDI IDV MAS LTO_WVS Indulgence Monumentalism 63 44 70 9 85 60 18 39 95 93 39 36 60 40 60 30 Lithuania 65 Taiwan 69 China 30 Japan 92 42 58 80 54 60 17 20 46 19 45 66 95 69 86 75 81 81 82 16 32 93 21 82 93 87 88 83 40 84 93 77 76 74 74 74 65 62 56 52 46 63

Highest Indulgence Scores from Samples (Minkov used a different scoring system than Hofstede’s) UAI PDI IDV MAS LTO_WVS Indulgence Ghana 4 435 Ghana Nigeria 13 435 Nigeria Puerto Rico 0 432 Puerto Rico Venezuela 76 81 12 73 16 398 Venezuela Mexico 82 81 30 69 24 370 Mexico Costa Rica 86 35 15 21 369 Costa Rica Peru 87 64 16 42 25 243 64

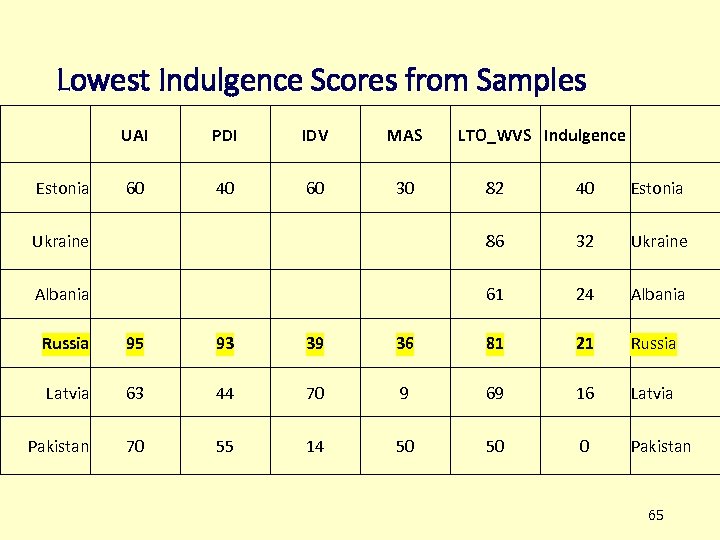

Lowest Indulgence Scores from Samples UAI Estonia PDI IDV MAS 60 40 60 30 LTO_WVS Indulgence 82 40 Estonia Ukraine 86 32 Ukraine Albania 61 24 Albania Russia 95 93 39 36 81 21 Russia Latvia 63 44 70 9 69 16 Latvia Pakistan 70 55 14 50 50 0 Pakistan 65

66

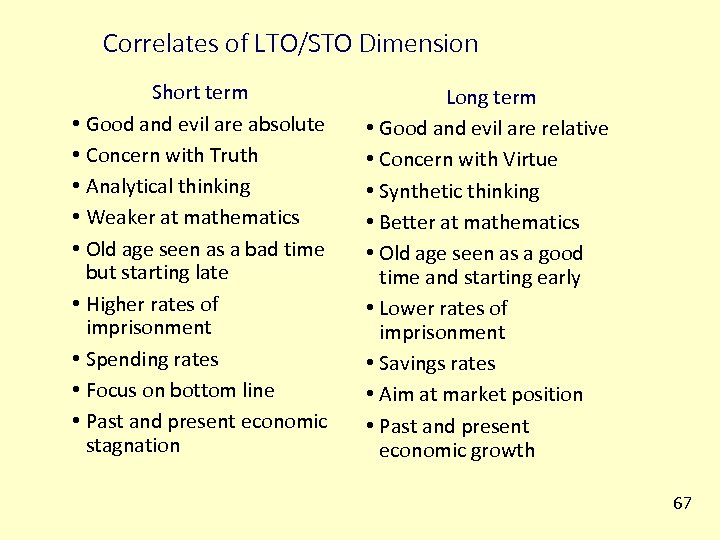

Correlates of LTO/STO Dimension Short term • Good and evil are absolute • Concern with Truth • Analytical thinking • Weaker at mathematics • Old age seen as a bad time but starting late • Higher rates of imprisonment • Spending rates • Focus on bottom line • Past and present economic stagnation Long term • Good and evil are relative • Concern with Virtue • Synthetic thinking • Better at mathematics • Old age seen as a good time and starting early • Lower rates of imprisonment • Savings rates • Aim at market position • Past and present economic growth 67

Are there national management and leadership cultures ? • In national cultures, all spheres of life and society are interrelated: family, school, job, religious practice, economic behavior, health, crime, punishment, art, science, literature, management, leadership • Hofstede: There is no separate national management or leadership culture – management and leadership can only be understood as part of the larger culture 68

For review: recent discussion by Hofstede, about 30 minutes • https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=LBv 1 w. Lu. Y 3 Ko 69

Review: Additional dimensions: Michael Minkov About an hour: https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=z. CR 1 cm 468 QE 70

1 Hofstede’s descriptions of expected behaviors and cultural traits as a function of cultural value scores and environment Hofstede, G. (1994) The business of international business is culture, International Business Review, 3(1), 1 -14. Cultural traits summarised from notes of Prof. & Dean Emeritus Charles H. Tidwell, Jr. , Ph. D Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI, USA, and Adjunct Professor, Southern Adventist University, Collegedale, Tennessee, USA

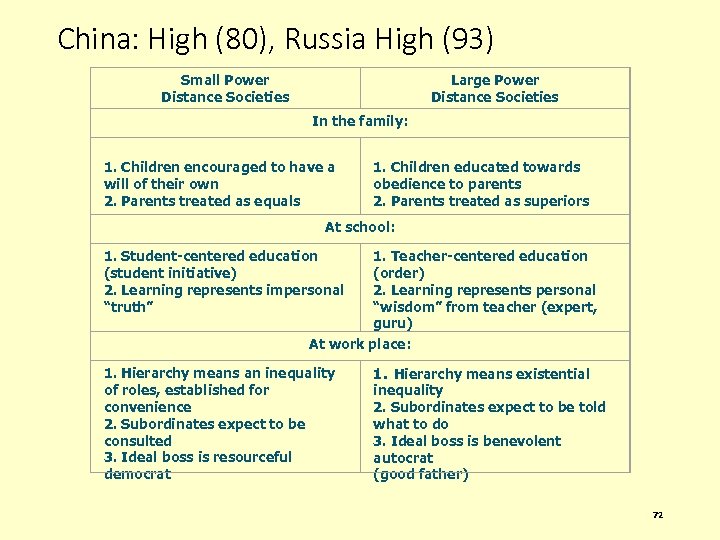

China: High (80), Russia High (93) Small Power Distance Societies Large Power Distance Societies In the family: 1. Children encouraged to have a will of their own 2. Parents treated as equals 1. Children educated towards obedience to parents 2. Parents treated as superiors At school: 1. Student-centered education (student initiative) 2. Learning represents impersonal “truth” 1. Teacher-centered education (order) 2. Learning represents personal “wisdom” from teacher (expert, guru) At work place: 1. Hierarchy means an inequality of roles, established for convenience 2. Subordinates expect to be consulted 3. Ideal boss is resourceful democrat 1. Hierarchy means existential inequality 2. Subordinates expect to be told what to do 3. Ideal boss is benevolent autocrat (good father) 72

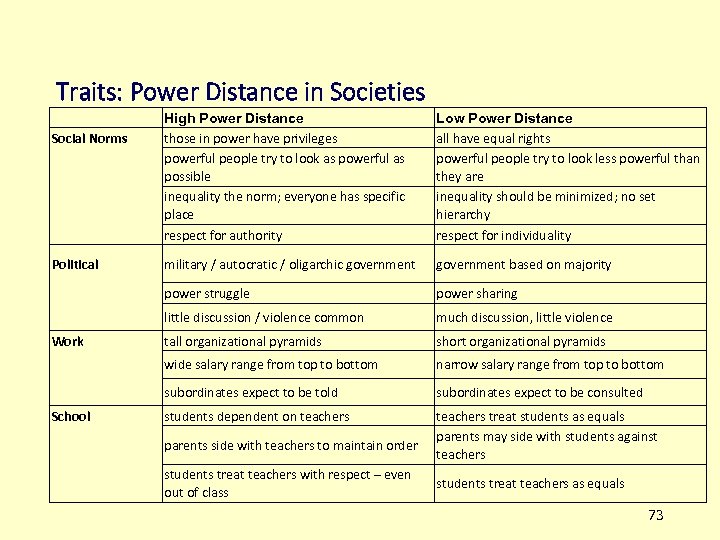

Traits: Power Distance in Societies power sharing much discussion, little violence tall organizational pyramids short organizational pyramids narrow salary range from top to bottom subordinates expect to be told School government based on majority wide salary range from top to bottom Work military / autocratic / oligarchic government little discussion / violence common Political Low Power Distance all have equal rights powerful people try to look less powerful than they are inequality should be minimized; no set hierarchy respect for individuality power struggle Social Norms High Power Distance those in power have privileges powerful people try to look as powerful as possible inequality the norm; everyone has specific place respect for authority subordinates expect to be consulted students dependent on teachers treat students as equals parents may side with students against teachers parents side with teachers to maintain order students treat teachers with respect – even out of class students treat teachers as equals 73

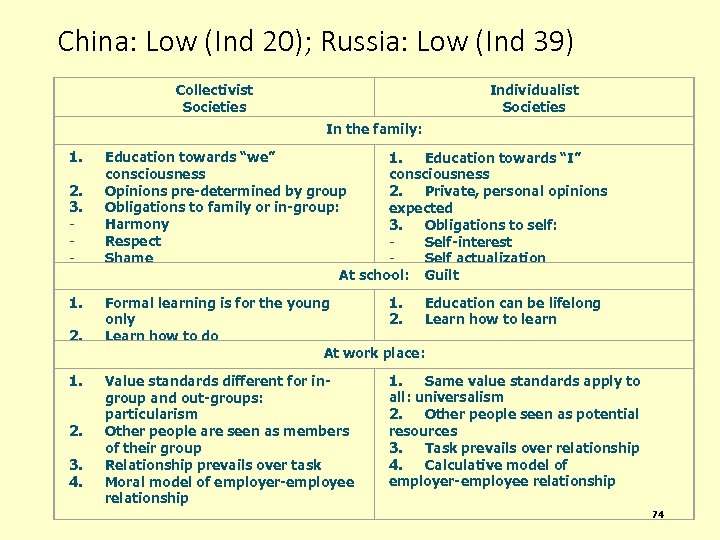

China: Low (Ind 20); Russia: Low (Ind 39) Collectivist Societies Individualist Societies In the family: 1. 2. 3. 4. Education towards “we” 1. Education towards “I” consciousness Opinions pre-determined by group 2. Private, personal opinions Obligations to family or in-group: expected Harmony 3. Obligations to self: Respect Self-interest Shame Self actualization At school: Guilt Formal learning is for the young 1. Education can be lifelong only 2. Learn how to learn Learn how to do At work place: Value standards different for ingroup and out-groups: particularism Other people are seen as members of their group Relationship prevails over task Moral model of employer-employee relationship 1. Same value standards apply to all: universalism 2. Other people seen as potential resources 3. Task prevails over relationship 4. Calculative model of employer-employee relationship 74

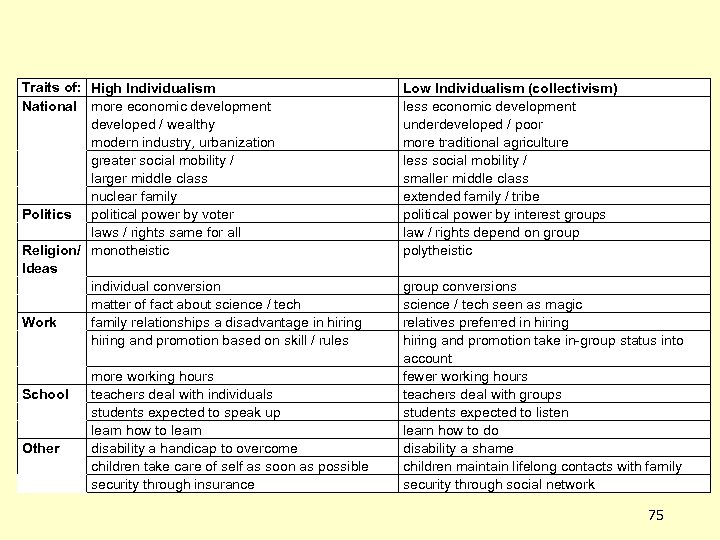

Traits of: High Individualism National more economic development developed / wealthy modern industry, urbanization greater social mobility / larger middle class nuclear family Politics political power by voter laws / rights same for all Religion/ monotheistic Ideas individual conversion matter of fact about science / tech Work family relationships a disadvantage in hiring and promotion based on skill / rules School Other more working hours teachers deal with individuals students expected to speak up learn how to learn disability a handicap to overcome children take care of self as soon as possible security through insurance Low Individualism (collectivism) less economic development underdeveloped / poor more traditional agriculture less social mobility / smaller middle class extended family / tribe political power by interest groups law / rights depend on group polytheistic group conversions science / tech seen as magic relatives preferred in hiring and promotion take in-group status into account fewer working hours teachers deal with groups students expected to listen learn how to do disability a shame children maintain lifelong contacts with family security through social network 75

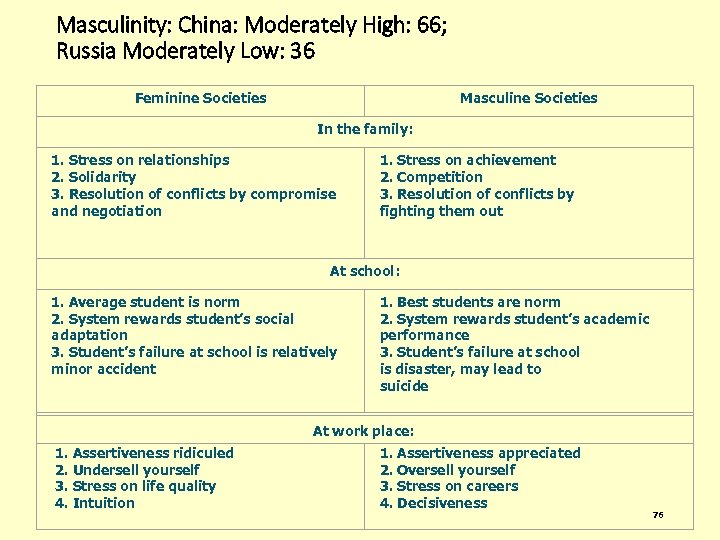

Masculinity: China: Moderately High: 66; Russia Moderately Low: 36 Feminine Societies Masculine Societies In the family: 1. Stress on relationships 2. Solidarity 3. Resolution of conflicts by compromise and negotiation 1. Stress on achievement 2. Competition 3. Resolution of conflicts by fighting them out At school: 1. Average student is norm 2. System rewards student’s social adaptation 3. Student’s failure at school is relatively minor accident 1. Best students are norm 2. System rewards student’s academic performance 3. Student’s failure at school is disaster, may lead to suicide At work place: 1. Assertiveness ridiculed 2. Undersell yourself 3. Stress on life quality 4. Intuition 1. Assertiveness appreciated 2. Oversell yourself 3. Stress on careers 4. Decisiveness 76

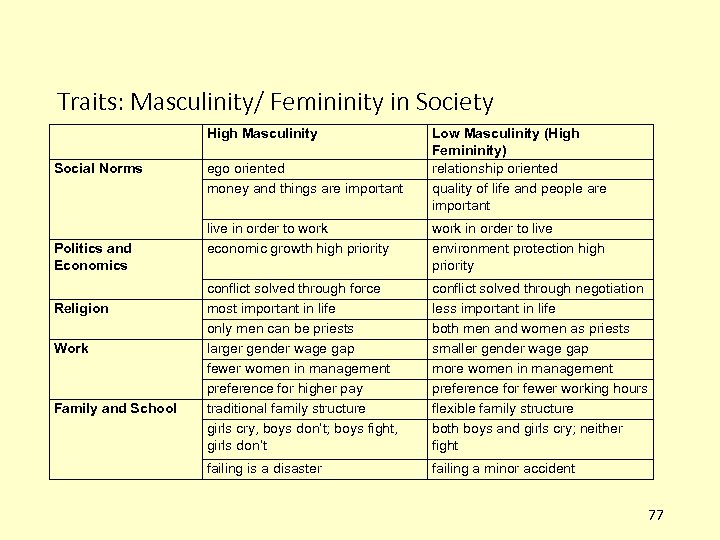

Traits: Masculinity/ Femininity in Society High Masculinity Social Norms Politics and Economics Religion Work Family and School ego oriented money and things are important Low Masculinity (High Femininity) relationship oriented quality of life and people are important live in order to work economic growth high priority work in order to live environment protection high priority conflict solved through force most important in life only men can be priests larger gender wage gap fewer women in management preference for higher pay traditional family structure girls cry, boys don’t; boys fight, girls don’t conflict solved through negotiation less important in life both men and women as priests smaller gender wage gap more women in management preference for fewer working hours flexible family structure both boys and girls cry; neither fight failing is a disaster failing a minor accident 77

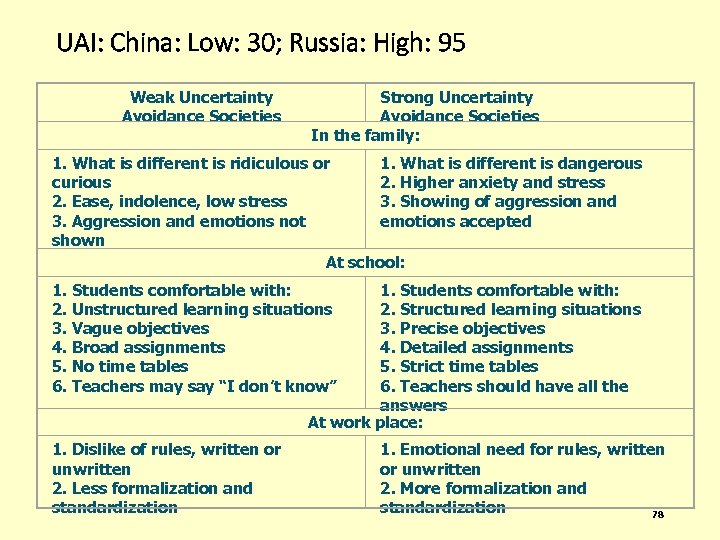

UAI: China: Low: 30; Russia: High: 95 Weak Uncertainty Avoidance Societies Strong Uncertainty Avoidance Societies In the family: 1. What is different is ridiculous or 1. What is different is dangerous curious 2. Higher anxiety and stress 2. Ease, indolence, low stress 3. Showing of aggression and 3. Aggression and emotions not emotions accepted shown At school: 1. Students comfortable with: 2. Unstructured learning situations 3. Vague objectives 4. Broad assignments 5. No time tables 6. Teachers may say “I don’t know” 1. Students comfortable with: 2. Structured learning situations 3. Precise objectives 4. Detailed assignments 5. Strict time tables 6. Teachers should have all the answers At work place: 1. Dislike of rules, written or unwritten 2. Less formalization and standardization 1. Emotional need for rules, written or unwritten 2. More formalization and standardization 78

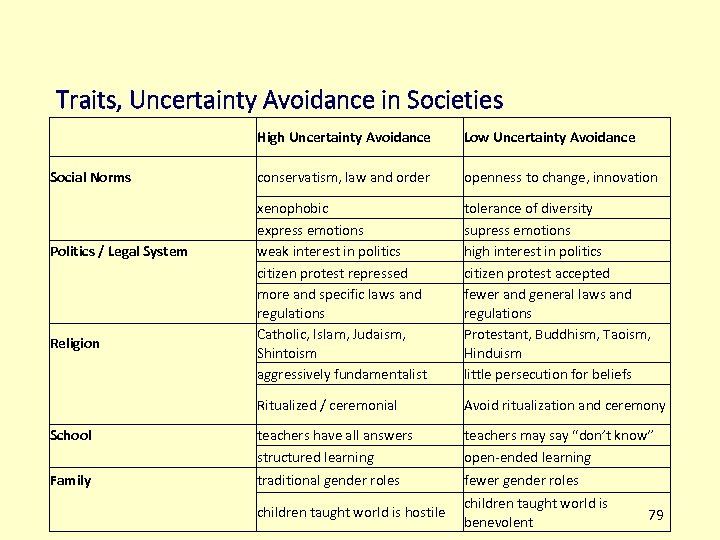

Traits, Uncertainty Avoidance in Societies High Uncertainty Avoidance Low Uncertainty Avoidance conservatism, law and order openness to change, innovation xenophobic express emotions weak interest in politics citizen protest repressed more and specific laws and regulations Catholic, Islam, Judaism, Shintoism aggressively fundamentalist tolerance of diversity supress emotions high interest in politics citizen protest accepted fewer and general laws and regulations Protestant, Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism little persecution for beliefs Ritualized / ceremonial Avoid ritualization and ceremony School teachers have all answers structured learning teachers may say “don’t know” open-ended learning Family traditional gender roles fewer gender roles children taught world is hostile children taught world is benevolent Social Norms Politics / Legal System Religion 79

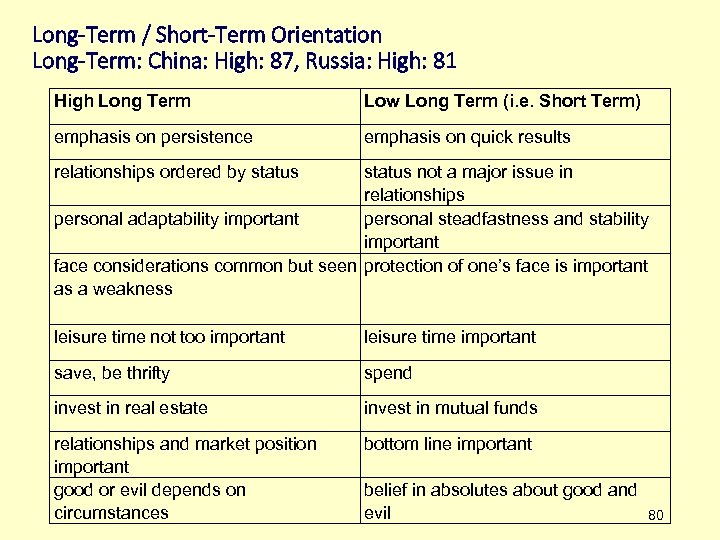

Long-Term / Short-Term Orientation Long-Term: China: High: 87, Russia: High: 81 High Long Term Low Long Term (i. e. Short Term) emphasis on persistence emphasis on quick results relationships ordered by status not a major issue in relationships personal adaptability important personal steadfastness and stability important face considerations common but seen protection of one’s face is important as a weakness leisure time not too important leisure time important save, be thrifty spend invest in real estate invest in mutual funds relationships and market position important good or evil depends on circumstances bottom line important belief in absolutes about good and evil 80

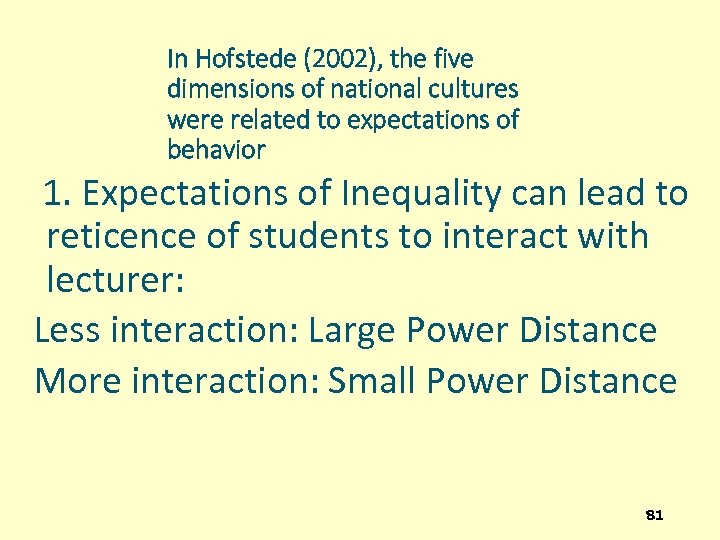

In Hofstede (2002), the five dimensions of national cultures were related to expectations of behavior 1. Expectations of Inequality can lead to reticence of students to interact with lecturer: Less interaction: Large Power Distance More interaction: Small Power Distance 81

In Hofstede (2002), the five dimensions of national cultures were related to expectations of behavior 2. Reaction to the unfamiliar can influence openness to new ideas and new ways of doing things: Fight: Strong Uncertainty Avoidance Tolerate: Weak Uncertainty Avoidance 82

In Hofstede (2002), the five dimensions of national cultures were related to expectations of behavior 3. Relation with in-group can affect the perception of the lecturer as an insider or outsider, and determine attitudes toward assisting other students: Loose relationship: Individualism Tight relationship: Collectivism 83

In Hofstede (2002), the five dimensions of national cultures were related to expectations of behavior 4. Emotional gender roles might affect attitudes toward male and female lecturers and fellow students: Different: Masculinity Same: Femininity 84

In Hofstede (2002), the five dimensions of national cultures were related to expectations of behavior 5. Need gratification: Later: Long Term Orientation Now: Short Term Orientation 85

Geert Hofstede’s 7 -Dimension theory in 2008 • Indulgence vs. Restraint: Indulgence defines a society that allows relatively free gratification of some desires and feelings, especially those that have to do with leisure, merrymaking with friends, spending, consumption, and sex. Its opposite pole, • Restraint, defines a society which restricts such gratification, and where people feel less free and able to enjoy their lives. 86

• Indulgence vs. Restraint. Minkov (27, p. 114) specifies that at the societal level, happiness is associated with a perception of life control, with life control being a source of freedom and of leisure. • Societies with high means for Indulgence tend to co-mingle work and social activities, and generally have a less “serious” attitude toward work than societies with high means for Restraint. 87

Geert Hofstede’s 7 -Dimension theory in 2008 • Monumentalism vs. Flexumility (a created word, with the dimension name changed to Self Effacement by theorists): • Monumentalism is related to pride in self, national pride, making parents proud, and believing religion to be important, similar to Mc. Clelland’s (1961) concept of need for achievement 88

Geert Hofstede’s 7 -Dimension theory in 2008 • Monumentalism vs. Flexumility (a created word, with the dimension name changed to Self Effacement by theorists): • The Flexumility pole identifies societies valuing humility, with members seeing themselves as not having a stable, invariant self-concept, and a flexible attitude toward Truth. 89

Hofstede Related to Business Practice 90

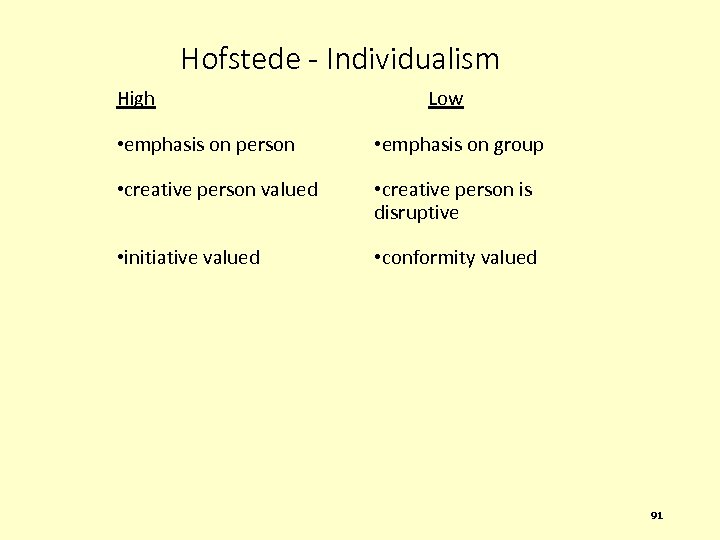

Hofstede - Individualism High • emphasis on person Low • emphasis on group • creative person valued • creative person is disruptive • initiative valued • conformity valued 91

General conclusion from culture studies There is no such thing as a universal economic or psychological rationality NATIONALITY constrains RATIONALITY 97

Student-level book, 25 Academic book, 21 98

Details for studenets’ independent review: http: //www. geerthofstede. com/ Further reading, Geert & Gert Jan Hofstede’s website

Hofstede Related to Business Practice 100

The business of international business is culture Hofstede, Geert (1994) “The Business of International Business is Culture”, International Business Review, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 1 -14. Hofstede, Geert (24) “The Business of International Business is Culture, Even More So!”, Academy of Management International Management Division Newsletter, December, pp. 1 -14. http: //division. aomonline. org/im/about/Newsletters/AOM_D EC 04. pdf 101

Hofstede: The Business of International Business is Culture, Even More So! • The functioning of international business organizations hinges on intercultural communication and cooperation. • Geert Hofstede: “As I wrote in 1994, managing international business means handling both national and organizational culture differences at the same time. ” 102

Hofstede: The Business of International Business is Culture, Even More So! • Organizational cultures are somewhat manageable while national cultures are given facts for management; • common organizational cultures across borders are what keeps multinationals together. 103

Hofstede: The Business of International Business is Culture, Even More So! • As tariff and technological advantages wear off, competition automatically shifts, besides towards economic factors, towards cultural advantages or disadvantages. • No country and no organization can be good at everything; cultural strengths imply cultural weaknesses. • This is a strong argument for making cultural considerations part of strategic planning, and locating activities in countries, in regions and in organizational units that possess the cultural characteristics necessary for competing in these activities. 104

Hofstede: The Business of International Business is Culture, Even More So! • Culture is present in the design and quality of products and in the presentation of services. • In the 1980 s the belief spread that technology and modernity would lead to a worldwide convergence of consumers' needs and desires. • This should enable global companies to develop standard brands with universal marketing and advertising programs. 105

Hofstede: The Business of International Business is Culture, Even More So! • In the 1990 s more and more voices in the marketing literature expressed doubts about this convergence, and referred to culture indices to explain persistent cultural differences. • Analysing national consumer behaviour data over time, Dutch marketing expert Marieke de Mooij showed that actual buying and consumption patterns in affluent countries in the 1980 s and 90 s diverged as much as they converged. • Affluence implies more possibilities to choose among products and services, and consumers‘ choices reflected psychological and social needs which are culture-bound. 106

Hofstede: The Business of International Business is Culture, Even More So! • In advertising, the same global brand may appeal to different cultural themes in different countries. • In general, what is a bicycle? • In Mexico? • In China? • In the USA? 107

Hofstede: The Business of International Business is Culture, Even More So! • Advertising, and television advertising in particular, is directed at the inner motivation of prospective buyers whose minds have not been and will not be globalised. • Organizations moving to unfamiliar cultural environments are often badly surprised by unexpected reactions of the press, the authorities or the public to what they do or want to do. 108

Hofstede: The Business of International Business is Culture, Even More So! • Perhaps the effect of the collective values of a society is nowhere as clear as in these cases. • The values are partly invisible to the newcomer, but they become all too visible in press reactions, government decisions, or organized actions by uninvited interest groups. 109

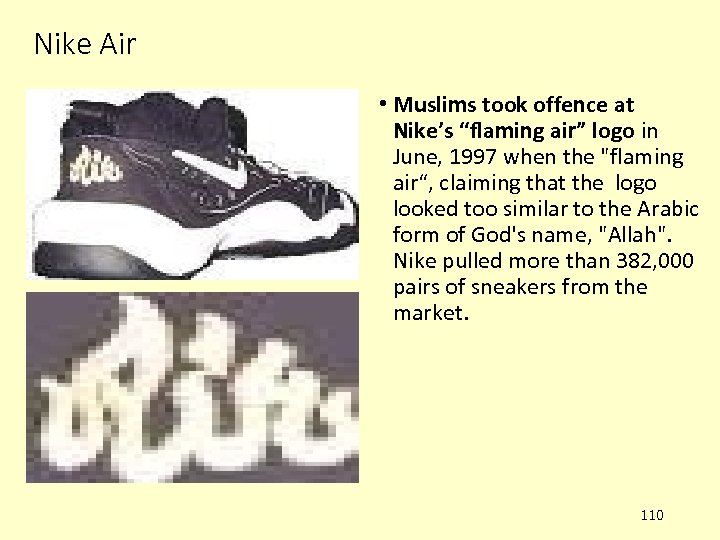

Nike Air • Muslims took offence at Nike’s “flaming air” logo in June, 1997 when the "flaming air“, claiming that the logo looked too similar to the Arabic form of God's name, "Allah". Nike pulled more than 382, 000 pairs of sneakers from the market. 110

Hofstede: The Business of International Business is Culture, Even More So! • Mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures and alliances across national borders have become quite frequent, but they remain a regular source of cross-cultural clashes. • Cross-national ventures have often turned out to be dramatic failures. This will continue as long as management decisions about international ventures will be based solely on financial considerations. • Those making the decision rarely imagine the operating problems that arise inside the newly formed hybrid organizations. 111

Hofstede: The Business of International Business is Culture, Even More So! • Even within countries, such ventures have a dubious success record, but across borders they are even less likely to succeed. • If cultural conditions do look favourable, the cultural integration of the new cooperative structure should still be managed; it does not happen by itself. • Cultural integration takes lots of time, energy, and money. • These are some of the implications of culture spelled out in the new, edition of my book “Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind”. 112

Culture Shock and Hofstede’s Power Distance • Geert Hofstede (Culture’s Consequences, 1980, p. 21) studied culture within organizations. • Part of his study was on the dependence relationship or Power Distance -- the extent to which the less powerful members of an organization expect and accept that power is distributed unequally. 113

Hofstede uses this story to illustrate Power Difference • The last revolution in Sweden disposed of King Gustav IV, whom they considered incompetent, and surprising invited Jean Baptise Bernadotte, a French general who served under Napoleon, to become their new King. • He accepted and became King Charles XIV. Soon afterward he needed to address the Swedish Parliament. • Wanting to be accepted, he tried to do the speech in their language. His broken Swedish amused the Swedes so much that they roared with laughter. 114

Culture Shock • The Frenchman was so upset that he never tried to speak Swedish again. Bernadotte was a victim of culture shock -- never in his French upbringing and military career had he experienced subordinates who laughed at the mistakes of their superior. • This story has a happy ending as he was considered a very good king and ruled the country as a highly respected constitutional monarch until 1844 (his descendants still occupy the Swedish throne). 115

Social Stratification • Social ranking is determined by • an individual’s achievements and qualifications • an individual’s affiliation with, or membership in, certain groups 2 -116

Social Stratification • Group affiliations can be • Ascribed group memberships • based on gender, family, age, caste, and ethnic, racial, or national origin • Acquired group memberships • based on religion, political affiliation, professional association • Two other factors that are important • education and social connections 2 -117

Work Motivation • The motivation to work differs across cultures • Studies show • the desire for material wealth is a prime motivation to work • promotes economic development • people are more eager to work when the rewards for success are high • masculinity-femininity index • high masculinity score prefers “to live to work” than “to work to live” Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -118

Work Motivation • Hierarchy of needs theory • Individuals will fill lower-level needs before moving to higher level needs 2 -119

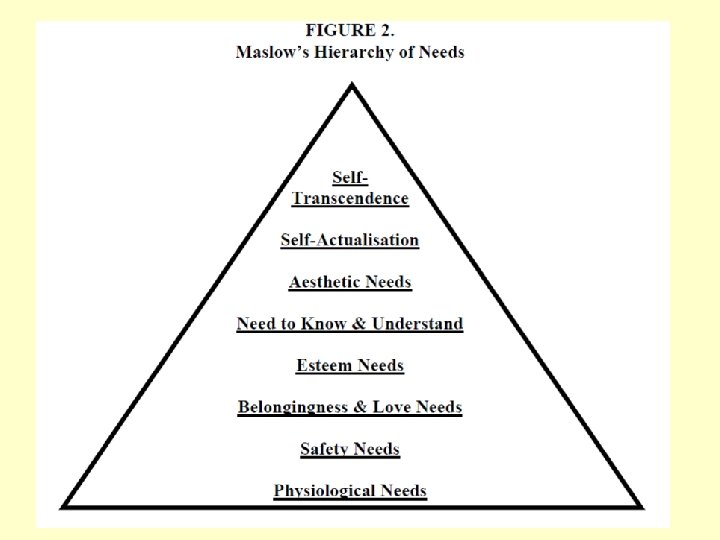

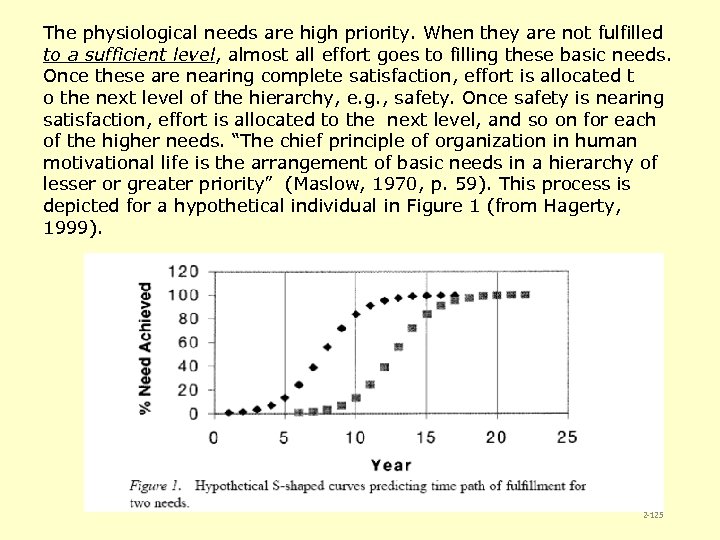

Maslow and. Motivation • The physiological needs are high priority. When they are not fulfilled to a sufficient level, almost all effort goes to filling these basic needs. Once these are nearing complete satisfaction, effort is allocated to the next level of the hierarchy, e. g. , safety. Once safety is nearing satisfaction, effort is allocated to the next level, and so on for each of the higher needs. 2 -120

Maslow and Motivation “The chief principle of organization in human motivational life is the arrangement of basic needs in a hierarchy of lesseror greater priority” (Maslow, 1970, p. 59). • The ranking of needs differs among cultures: See: http: //crossculturalcentre. homestead. com/Ma slow_Academic_Amnesia_CCCC_Working_Pap er_2012 -3. . pdf 2 -121

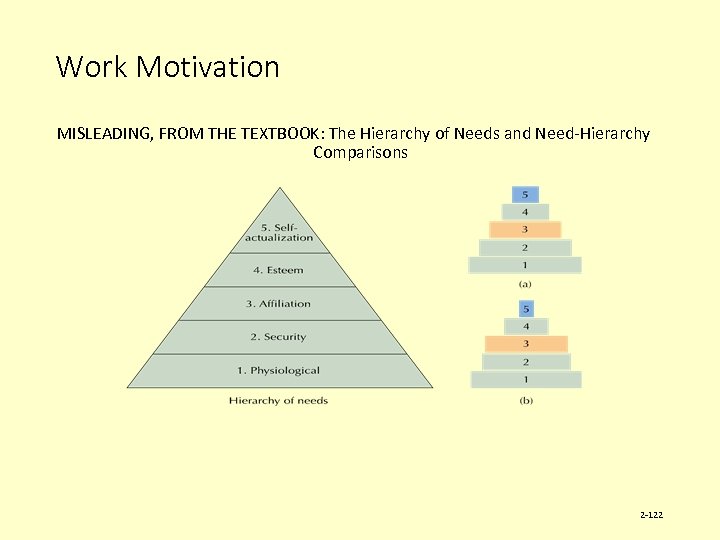

Work Motivation MISLEADING, FROM THE TEXTBOOK: The Hierarchy of Needs and Need-Hierarchy Comparisons 2 -122

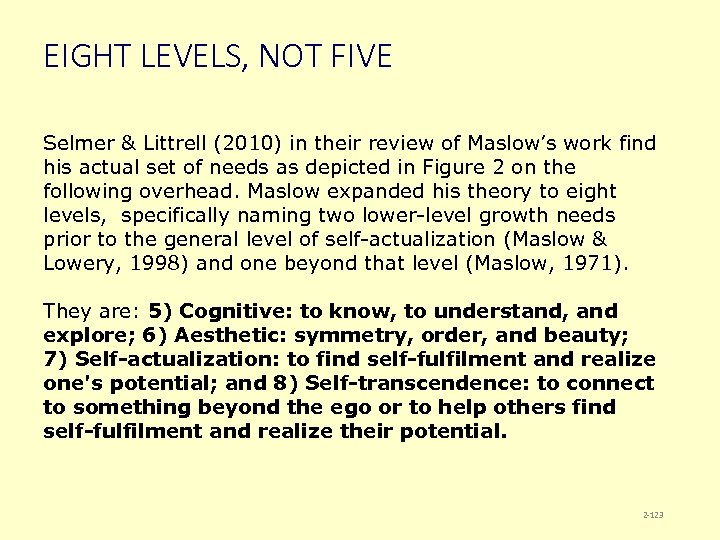

EIGHT LEVELS, NOT FIVE Selmer & Littrell (2010) in their review of Maslow’s work find his actual set of needs as depicted in Figure 2 on the following overhead. Maslow expanded his theory to eight levels, specifically naming two lower-level growth needs prior to the general level of self-actualization (Maslow & Lowery, 1998) and one beyond that level (Maslow, 1971). They are: 5) Cognitive: to know, to understand, and explore; 6) Aesthetic: symmetry, order, and beauty; 7) Self-actualization: to find self-fulfilment and realize one's potential; and 8) Self-transcendence: to connect to something beyond the ego or to help others find self-fulfilment and realize their potential. 2 -123

2 -124

The physiological needs are high priority. When they are not fulfilled to a sufficient level, almost all effort goes to filling these basic needs. Once these are nearing complete satisfaction, effort is allocated t o the next level of the hierarchy, e. g. , safety. Once safety is nearing satisfaction, effort is allocated to the next level, and so on for each of the higher needs. “The chief principle of organization in human motivational life is the arrangement of basic needs in a hierarchy of lesser or greater priority” (Maslow, 1970, p. 59). This process is depicted for a hypothetical individual in Figure 1 (from Hagerty, 1999). 2 -125

Relationship Preferences • Relationship preferences differ by culture • Power distance • high power distance implies little superior-subordinate interaction • autocratic or paternalistic management style • low power distance implies consultative style • Individualism versus collectivism • high individualism – welcome challenges • high collectivism – prefer safe work environment 2 -126

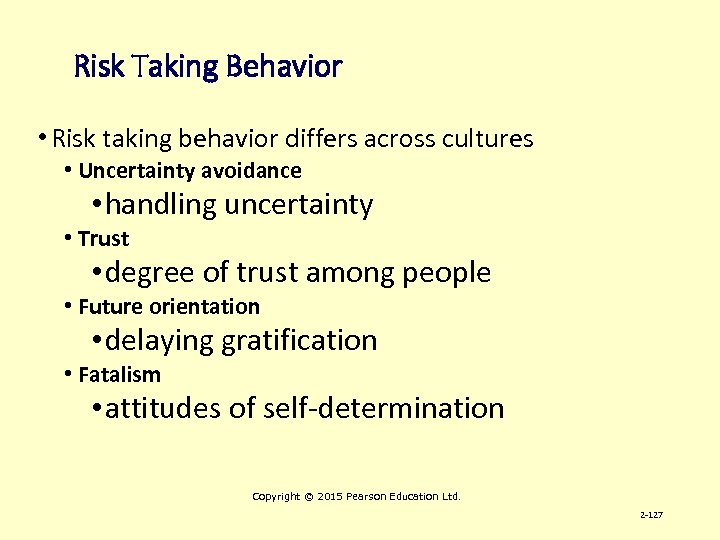

Risk Taking Behavior • Risk taking behavior differs across cultures • Uncertainty avoidance • handling uncertainty • Trust • degree of trust among people • Future orientation • delaying gratification • Fatalism • attitudes of self-determination Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -127

Information and Task Processing • Cultures handle information in different ways • Perception of cues • Obtaining information • low context versus high context cultures • Information processing • Monochronic versus polychronic cultures • Idealism versus pragmatism Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -128

Communications • Cross border communications do not always translate as intended • Spoken and written language • Silent language • Color • Distance • Time and punctuality • Body language • Prestige 2 -129

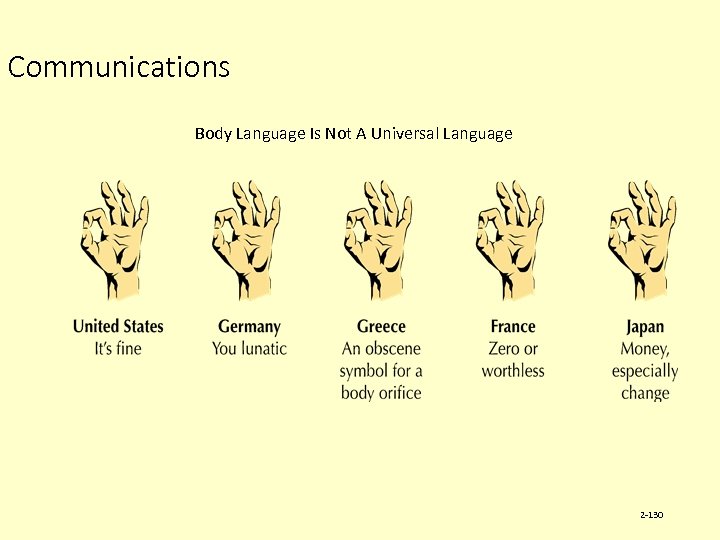

Communications Body Language Is Not A Universal Language 2 -130

Dealing with Cultural Differences Learning Objective: Analyze guidelines for cultural adjustment 2 -131

Dealing with Cultural Differences • Do managers have to alter their customary practices to succeed in countries with different cultures? • Must consider • Host society acceptance • Degree of cultural differences • cultural distance • Ability to adjust • culture shock and reverse culture shock • Company and management orientation Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -132

Dealing with Cultural Differences • Three company and management orientations • Polycentrism • business units abroad should act like local companies • Ethnocentrism • home culture is superior to local culture • overlook national differences • Geocentrism • integrate home and host practices 2 -133

Strategies for Instituting Change • Value Systems • Cost-Benefit Analysis of change • Resistance to too much change • Participation • Reward Sharing • Opinion Leadership • Timing • Learning Abroad 2 -134

The Future of National Cultures • Scenario 1: • New hybrid cultures will develop and personal horizons will broaden • Scenario 2: • Outward expressions of national culture will continue to become homogeneous while distinct values will remain stable • Scenario 3: • Nationalism will continue to reinforce cultural identity • Scenario 4: • Existing national borders will shift to accommodate ethnic differences Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education Ltd. 2 -135

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. 2 -136

Hofstede: National versus organizational cultures • National culture differences are rooted in values learned before age 10 • They pass from generation to generation • For organizations, they are given facts • Organizational cultures are rooted in practices learned on the job • Given enough management effort, they can be changed • International organizations are held together by shared practices, not by shared values 137

Research into national cultures Culture’s Consequences, Geert Hofstede, 1980 5 dimensions 1. Inequality: more or less? Power Distance large vs. small 2. The unfamiliar: fight or tolerate? Uncertainty Avoidance strong vs. weak 3. Relation with in-group: loose or tight? Individualism vs. Collectivism 4. Emotional gender roles: different or same? Masculinity vs. Femininity 5. Need gratification: later or now? Long vs. Short term orientation 138

Culture’s recent consequences 11 April 2005 Geert Hofstede The individual components of this presentation and the entire presentation may be used in not-for-profit educational settings with proper attribution. Citation: Hofstede, Geert (2005) Culture’s recent consequences Power. Point® file, http: //crossculturalcentre. homestead. com/Publications. html, [18 March 2018] 2 -139

Culture (in the anthropological sense) collective programming of the mind distinguishing the members of one group or category of people from another group/category can be nation, region, organization, profession, generation, gender 2 -140

Mental programmmes 141

Values • Values are strong emotions with a minus and a plus pole • Like evil-good, abnormal-normal, dangeroussafe, dirty-clean, immoral-moral, indecent, unnatural-natural, paradoxicallogical, ugly-beautiful, irrational-rational • What is rational is a matter of values 2 -142

The learning of culture 2 -143

National versus organizational cultures • National culture differences are rooted in values learned before age 10 • They pass from generation to generation • For organizations, they are given facts • Organizational cultures are rooted in practices learned on the job • Given enough management effort, they can be changed • International organizations are held together by shared practices, not by shared values 2 -144

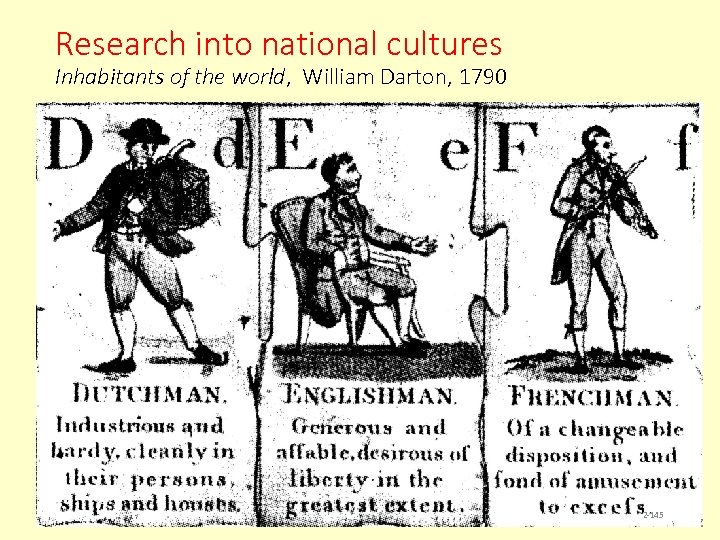

Research into national cultures Inhabitants of the world, William Darton, 1790 2 -145

Are there national management and leadership cultures ? • In national cultures, all spheres of life and society are interrelated: family, school, job, religious practice, economic behavior, health, crime, punishment, art, science, literature, management, leadership • There is no separate national management or leadership culture – management and leadership can only be understood as part of the larger culture 2 -146

Other examples of research results (last 10 years) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Consumer behavior Entrepreneurship Business goals Human rights Perceived corruption 2 -147

Consumer behavior 15 EU countries, 1970 – 2000 • When national incomes become more similar, consumer behavior converges as long as a product is scarce • After scarcity is over, consumer behavior diverges, following cultural values, especially Uncertainty Avoidance and Masculinity/Femininity which are unrelated to income Research: de Mooij, 2004 2 -148

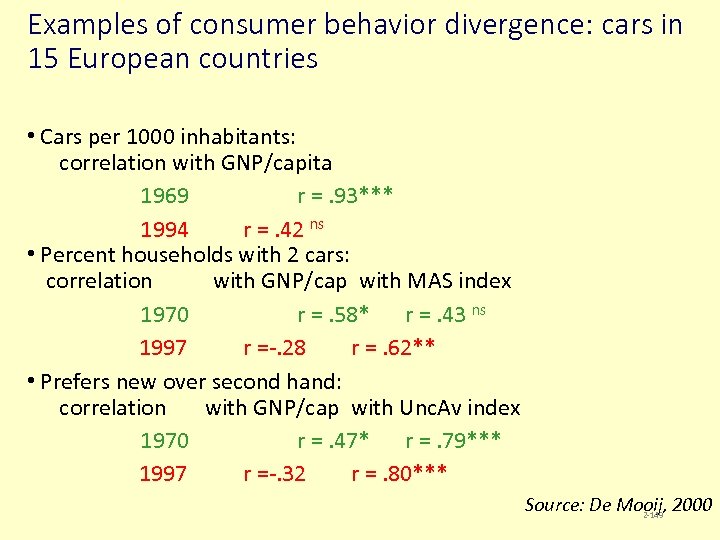

Examples of consumer behavior divergence: cars in 15 European countries • Cars per 1000 inhabitants: correlation with GNP/capita 1969 r =. 93*** 1994 r =. 42 ns • Percent households with 2 cars: correlation with GNP/cap with MAS index 1970 r =. 58* r =. 43 ns 1997 r =-. 28 r =. 62** • Prefers new over second hand: correlation with GNP/cap with Unc. Av index 1970 r =. 47* r =. 79*** 1997 r =-. 32 r =. 80*** Source: De Mooij, 2000 2 -149

Example of consumer behavior: new communication technology in Europe Adoption of PC’s, internet and mobile phones: no influence of national wealth, but slower where Uncertainty Avoidance was stronger Research: de Mooij, 2004 2 -150

Example of consumer behavior: use of internet in Europe Lasting differences in what internet is used for: • Feminine cultures use internet more for education and leisure (chatting) • Small Power Distance cultures use internet more for business • Weak Uncertainty Avoidance cultures use internet more for mail Research: de Mooij, 2004 2 -151

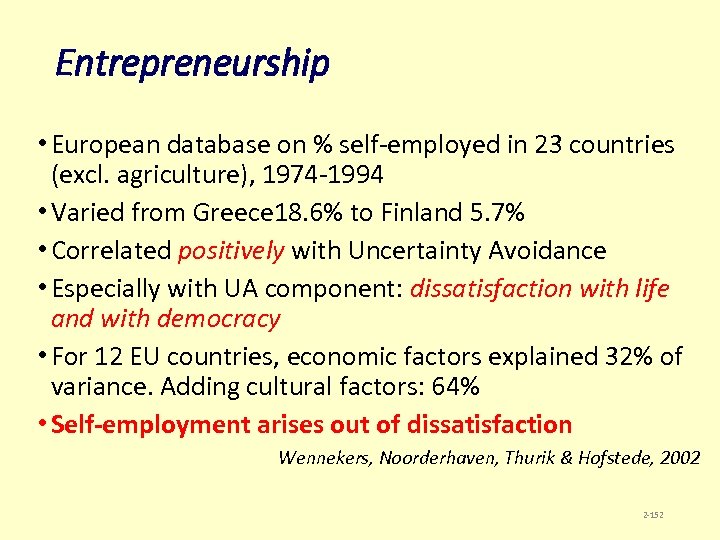

Entrepreneurship • European database on % self-employed in 23 countries (excl. agriculture), 1974 -1994 • Varied from Greece 18. 6% to Finland 5. 7% • Correlated positively with Uncertainty Avoidance • Especially with UA component: dissatisfaction with life and with democracy • For 12 EU countries, economic factors explained 32% of variance. Adding cultural factors: 64% • Self-employment arises out of dissatisfaction Wennekers, Noorderhaven, Thurik & Hofstede, 2002 2 -152

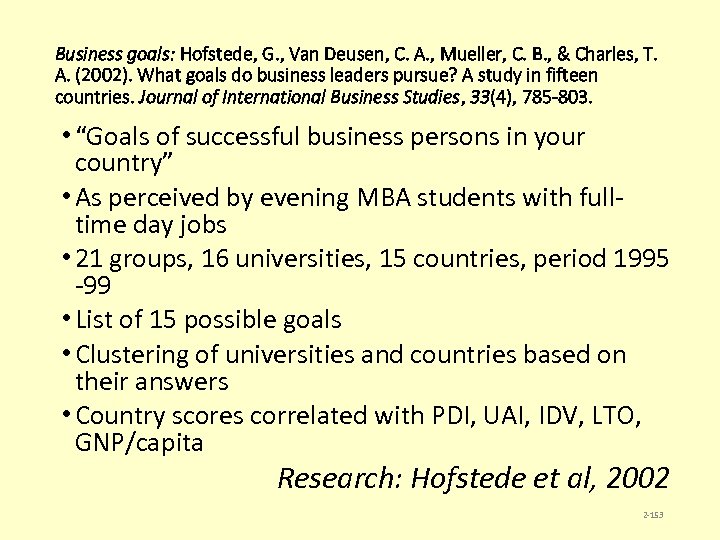

Business goals: Hofstede, G. , Van Deusen, C. A. , Mueller, C. B. , & Charles, T. A. (2002). What goals do business leaders pursue? A study in fifteen countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(4), 785 -803. • “Goals of successful business persons in your country” • As perceived by evening MBA students with fulltime day jobs • 21 groups, 16 universities, 15 countries, period 1995 -99 • List of 15 possible goals • Clustering of universities and countries based on their answers • Country scores correlated with PDI, UAI, IDV, LTO, GNP/capita Research: Hofstede et al, 2002 2 -153

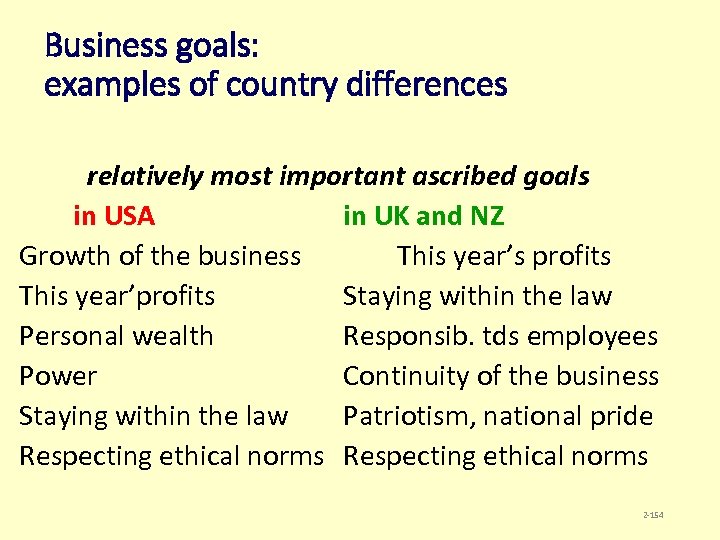

Business goals: examples of country differences relatively most important ascribed goals in USA in UK and NZ Growth of the business This year’s profits This year’profits Staying within the law Personal wealth Responsib. tds employees Power Continuity of the business Staying within the law Patriotism, national pride Respecting ethical norms 2 -154

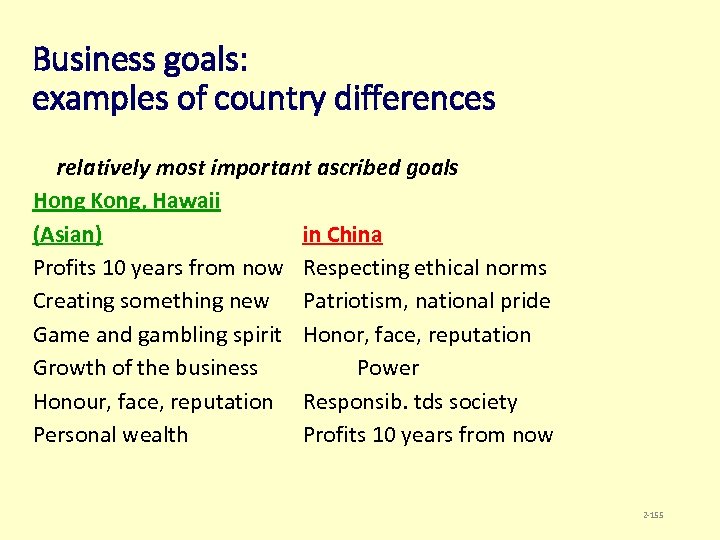

Business goals: examples of country differences relatively most important ascribed goals Hong Kong, Hawaii (Asian) in China Profits 10 years from now Respecting ethical norms Creating something new Patriotism, national pride Game and gambling spirit Honor, face, reputation Growth of the business Power Honour, face, reputation Responsib. tds society Personal wealth Profits 10 years from now 2 -155

Culture and Human Rights • • • HR Index 1992 based on 1948 Universal Declaration Regression on wealth (GNP/cap) plus culture indices Across 52 countries: only wealth explains differences (50%) If we want more respect for Human Rights we should combat poverty 2 -156

Human Rights Index • 27 poor countries: still only poverty explains differences (38%) • 25 wealthy countries: individualism explains differences (53%) “Universal” declaration of human rights is based on individualist values 2 -157

Perceived corruption An annual Corruption Perception Index (CPI), including almost all countries in the world, is composed by Transparency International of Berlin and published on Internet. It is based on data from business, media and diplomats Globally, the CPI is primarily a matter of national poverty, not of culture (poor countries are perceived as more corrupt) 2 -158

Perceived corruption • When the analysis is limited to wealthy countries, corruption perception differences no longer depend on wealth, but on culture. • In 1984, Michael Hoppe collected scores for the first 4 culture dimensions from Western political and intellectual elites, including prominent politicians, based on their own values. • 76% of the CPI differences among 18 Western countries in 2002 could be predicted from their elites’ self-scored Power Distance in 1984. Sources: Hoppe, Salzburg Seminar; own research 2 -159

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely” (Lord Acton , 1890) 2 -160

General conclusion from culture studies There is no such thing as a universal economic or psychological rationality NATIONALITY constrains RATIONALITY 2 -161

081ebcba02c494fa912a19b39cd7338c.ppt